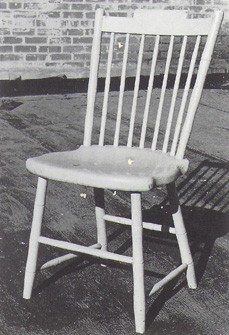

Bow-back Windsor side chair, William Cox, Philadelphia, 1788-1795. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, oak, and hickory. H. 36 7/8", W. 17 3/8", D. (seat) 15 7/8", (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 69.232.6.)

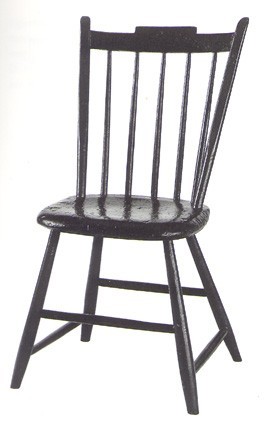

Bow-back Windsor side chair, northern Maryland, from the Susquehanna River to Fredrick Co., 1800-1810. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and oak. H. 35 1/16", W. (seat) 15 15/16", D. (seat) 16". (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Winterthur museum.)

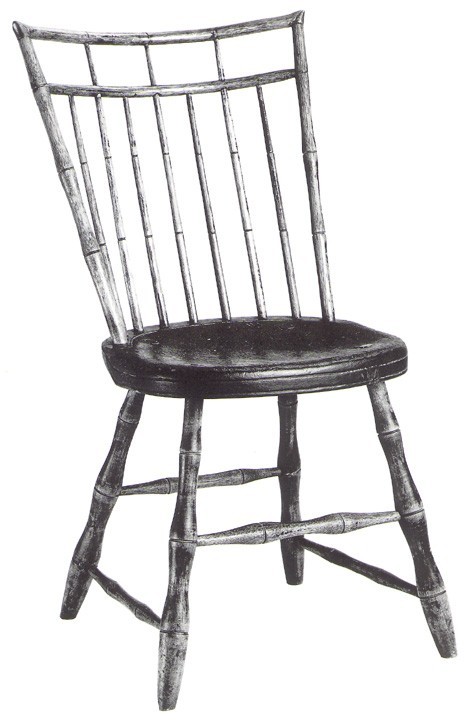

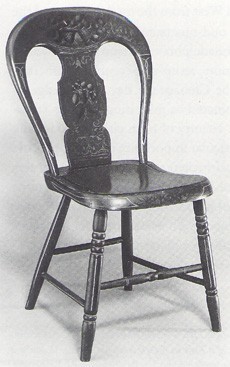

Bow-back Windsor side chair. Michael Stoner, probably Harrisburg, Pa., 1790-1795. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 37", W. (seat) 19 3/8", D. (seat) 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

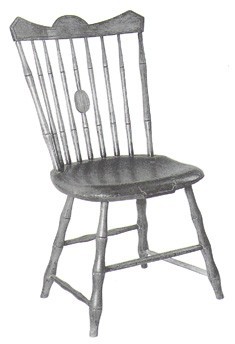

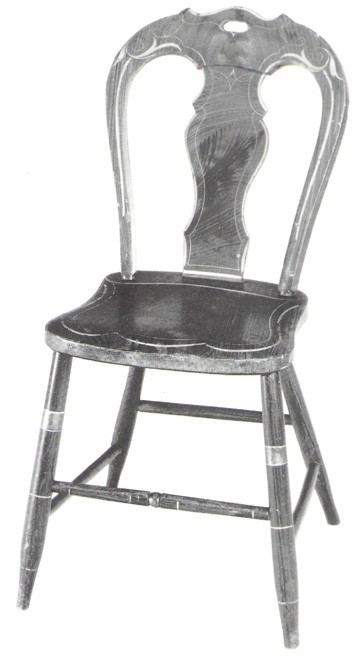

Bow-back Windsor side chair, Frederick Co., Md., 1800-1815. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Photo, courtesy, H. L. Chalfant Antiques.)

Bow-back Windsor side chair, Andrew and Robert McKim, Richmond, Va., 1795-1802. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and hickory. H. 35 3/4". (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

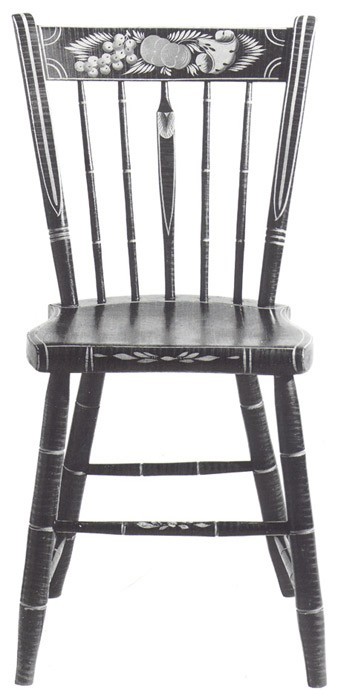

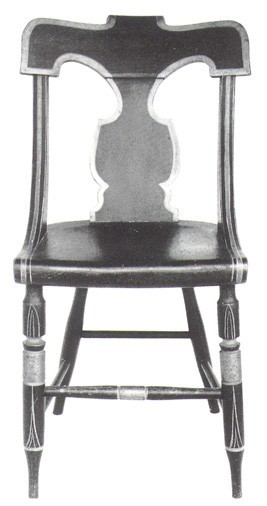

Square-back Windsor side chair, Andrew McIntire, Pittsburgh, Pa., 1800-1805. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 35, W. (seat) 16 1/4", D. (seat) 15 1/2". The medial and right stretchers and left rear leg are replaced. (Carnegie Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. James A. Drain.)

Square-back Windsor side chair, Philadelphia, 1798-1802. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and hickory. H. 34 1/2", W. (seat) 17 3/4", D. (seat) 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 56.571.)

Square-back Windsor side chair with double bows, Joseph Burden, Philadelphia, 1801-1812. Woods not recorded. H. 34 1/2", W. (seat) 16 3/4", D. (seat) 16 1/4". (Independence National Historical Park; courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.)

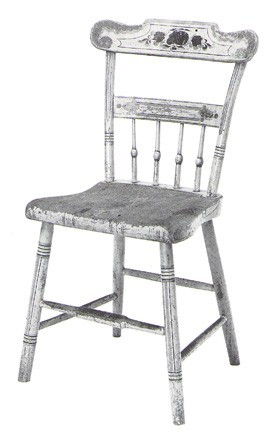

Square-back Windsor side chair with double bows, Pennsylvania, west of the Susquehanna River at the Maryland border, 1810-1820. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 37 1/16", W. (seat) 16 5/8", D (seat) 14". (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

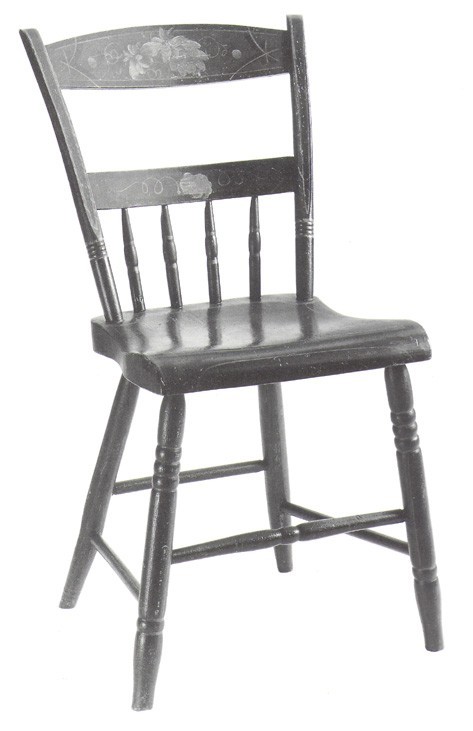

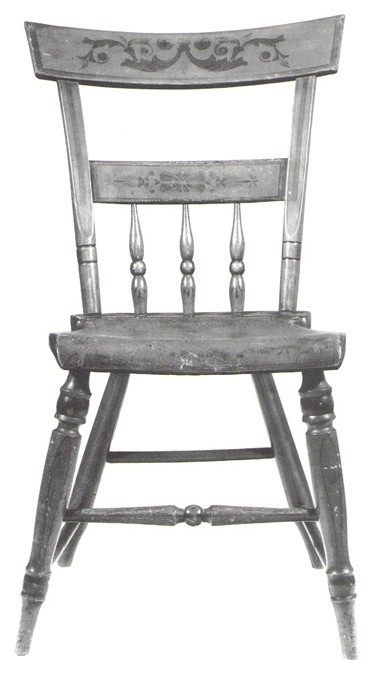

Slat-back Windsor side chair with tablet, Thomas Ashton, Philadelphia, 1810-1815. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 33". (Old Salem, Inc.; photo, courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair with tablet, Samuel Fizer, Fincastle, Va.,1820-1825. Woods not recorded. H. 33", W. (seat) 17 1/2". (Old Salem, Inc.; photo, courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair with double bows, southeastern Pennsylvania in the greater Susquehanna Valley, or northeastern Maryland, 1810-1820. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 34 3/4", W. (seat) 16 3/4", D. (seat) 15 1/4". (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top Windsor side chair, south central Pennsylvania, Maryland, or the Shenandoah Valley, Va., 1810-1820. Woods not recorded. H. 33 3/4", W. 18 3/4". The front and right stretchers are replaced. (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

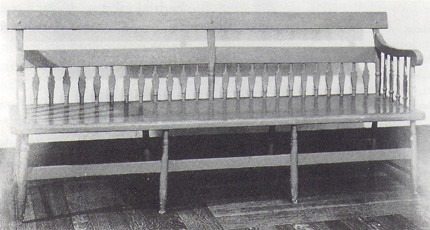

Tablet-top Windsor settee, Baltimore, 1807-1815. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and hickory. H. 36 1/8", W. (seat) 39 1/8", D. (seat) 15 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 59.3627.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair (one of two), eastern Pennsylvania, 1820-1835. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 34 1/4", W. (seat) 15 1/2",D. (seat) 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair, Adin G. Hibbs, Columbus, Ohio, 1833-1839. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Jane Sikes Hageman.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair, Alexander H. and William R. Wood, Nashville, Tenn.,

1817-1820. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and hickory. H. 33 1/2", W. (seat) 15 5/8", D. (seat) 15 1/2". (Travellers rest Historic House Museum, Inc.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair (one of six), Thomas Thompson Enos, Odessa, Del., 1845-1860. Yellow poplar (seat) with birch and beech.H. 32 1/2", W. (seat) 15 1/2", D. (seat) 13 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 81.70.1.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair, Jonas Thatcher, Wheeling, W.Va., 1839-1850. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 36", W. (seat) 16 1/4", D. (seat) 15 1/4". (Oglebay Institute Mansion Museum; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

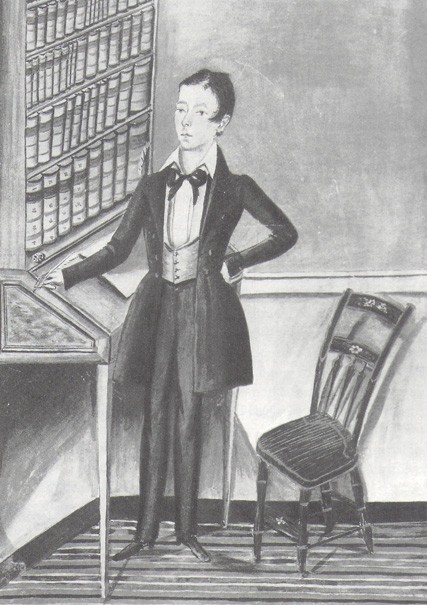

William Ferguson Cooper, attributed to Jacob Maentel, New Harmony, Ind., ca. 1842. Watercolor, pen, and pencil on paper. 15 1/2" x 10 1/2". (Historic New Harmony, New Harmony, Indiana.)

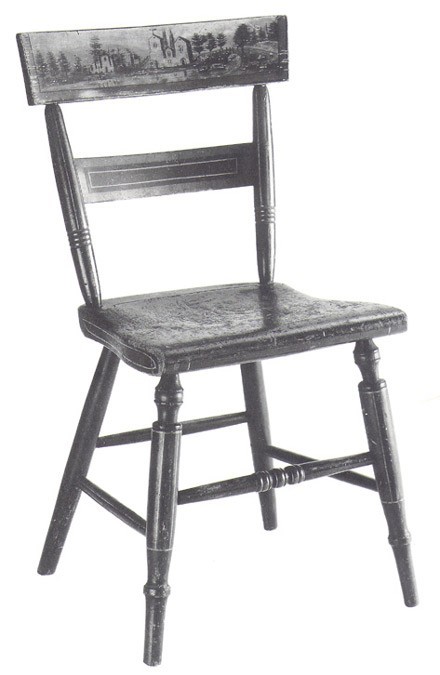

Tablet-top Windsor side chair, Baltimore, 1805-1812. H. 35 3/8". Woods not recorded. (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tablet-top fancy side chair (one of three), attributed to John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, 1800-1810. Maple, yellow poplar and mahogany. H. 33 1/4", W. (seat) 19", D. (seat) 15". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 57.1060.1.)

Tablet-top fancy side chair, John Hodgkinson, Baltimore, 1820-1830. Woods not recorded. H. 32", W. (seat) 18". (Private collection; photo, courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tablet-top Windsor side chair, William Cunningham, Wheeling, W. Va., 1828-1840. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 31 1/8", W. (seat) 16 3/4", D. (seat) 15". (Oglebay Institute Mansion Museum; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top Windsor side chair, Lancaster, Co., Pa., possibly Elizabethtown, 1830-1840. Woods not recorded. H. 32 5/8", W. (seat) 16 1/8", D. (seat) 14 7/8". (Philip H. Bradley Co.; photo. Courtesy Winterthur Museum.)

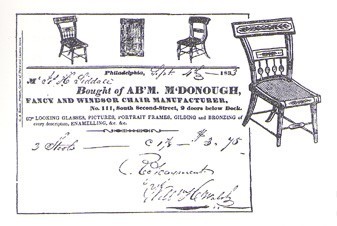

Abraham McDonough billhead and bill to Joseph H. Liddall, Philadelphia, 1833 (inscribed). From Carl W. Drepperd, Handbook of Antique Chairs (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1948, p. 160. (Photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top Windsor settee, Kentucky, 1835-1845. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and hickory. H. 34 1/2", W. (seat) 77", D. (seat) 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Liberty Hall Historic Site; photo, J.B. Speed Art Museum.

Tablet-top Windsor side chair, William Coles, Springfield, Ohio, 1840-1850. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple; H. 32", W. (seat) 17", D. (seat) 15". (Private collection; photo, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio.)

Tablet-top Windsor side chair (one of two), George Turner, Philadelphia, 1835-1842. Woods not recorded. H. 33 1/4", W. 16". (Private collection; courtesy, The Winterthur Library; Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.)

Child's tablet-top Windsor side chair, Jonas Thatcher, Wheeling, W.Va., 1845-1851. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 30 7/8", W. (seat) 14 1/2", D. (seat) 12 5/8". (Oglebay Institute Mansion Museum; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top Windsor side chair (one of four), John Swint, Lancaster, Pa., 1845-1855. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 33", W. (seat) 15 3/8",D. (seat) 14 5/8". (Courtesy of Lancaster County Historical Society, Lancaster, Pennsylvania; photo, courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top Windsor side chair (one of five with a rocking chair), Shenandoah Valley, Va., probably Rockingham Co., 1850-1870. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Mint Spring Antiques.)

Balloon-back Windsor side chair, probably eastern Pennsylvania, 1855-1870. Woods not recorded. H. 33 1/4", W. 18 3/8", D. 20 1/2". (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg.)

Balloon-back Windsor side chair (one of six), George Deckman, Malvern, Ohio, 1862-1880. Maple and other woods. H. 33 7/8", W. (seat) 16 1/2", D. (seat) 18 1/2". (From The Collections of Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village, Copy and Reuse Restrictions apply.)

The movement of individuals, products, and ideas from one region to another is a factor in studying vernacular furniture, particularly Windsor chairs made between the 1780s and 1860s. For example, the student of vernacular seating can observe Philadelphia influence on Windsor chairmaking in Boston, New York dominance of styles produced along the Long Island Sound, stylistic exchanges across the Connecticut Rhode Island border, and New England and New York contributions to chair production in eastern Canada. The purpose of the present study is to explore the impact of Philadelphia and Baltimore vernacular design on chairmaking in still other regions: rural Pennsylvania and Maryland; Virginia, from the tidewater to the Shenandoah, and "the West," the vast territory beyond the Appalachians settled in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Following the American revolution, the coastal South became a lucrative market for products of the Philadelphia Windsor chairmaking community. A key area of distribution was the lower Chesapeake Bay where a vast network of waterways and a system of inland roads provided access to the interior. Several Philadelphia craftsmen eventually relocated to the bay area. Ephraim Evans moved to Alexandria in 1785, and Michael Murphy was a temporary resident of Norfolk in 1800 and 1804. Communication between Philadelphia and the interior parts of Pennsylvania was also substantial, despite roads that became quagmires in spring and dust bowls in summer. During a journey along the Great Waggon Road connecting Philadelphia with Lancaster and points beyond, Isaac Weld, a British traveler in America during the mid 1790s, commented, "It is scarcely possible to go one mile on this road without meeting numbers of wagons passing and repassing between the back parts of the state and Philadelphia." He noted further that Philadelphia traded "as far as Pittsburgh itself, which is on the Ohio, with the back of Virginia, and, strange to tell, with Kentucky, seven hundred miles distant." Weld, like other travelers before and after him, observed the prevalence of German settlers in rural Pennsylvania, especially in the vicinity of Lancaster and York. Their settlements continued southwest into Frederick County, Maryland, and to Wincherter, Virginia, which served as the gateway for thousands of Germans to the fertile valley of the Shenandoah on the western side of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[1]

Germans and Scots Irish occupied the valley of Virginia long before the Revolution, and new migrations of Germans took place after the war. The Blue Ridge range virtually isolated the valley from eastern Virginia, but at the northern end trade with central Pennsylvania and Maryland was brisk. The southern outlet provided access to the Moravian settlements in central North Carolina and a route to the "western" lands for those who chose to move on to the new settlements in Kentucky and Tennessee.

Visiting Baltimore while a temporary resident in America during the 1790s, Englishman John Harriott observed that the community had experienced "the most rapid growth of any town in America." Depending upon the commentator, the flourishing city was denominated the third or fourth "commercial city" in the country by 1800, after Philadelphia, New York, and possibly Boston. In the decade between 1790 and 1800, the population of Baltimore almost doubled to more than 26,000. By 1810 the number had further risen by 87 percent. Baltimore already rivaled Philadelphia as a supplier of merchandise to the interior. Its merchants monopolized most trade within Maryland, realized a share of Virginia's commerce, competed with Philadelphia in filling the needs of the Pennsylvania back country, and furnished large amounts of goods for distribution in the western territories. In return, the business community received produce, primarily flour, for exportation.[2]

Before the Revolutionary War, the American frontier comprised all the lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Conditions changed rapidly in the postwar years. Kentucky and Tennessee were admitted to the Union in 1792 and 1796, respectively; Ohio followed in 1803, and Indiana in 1816. For purposes of the present study these four bodies politic constitute the "West." Preceding, accompanying, or following the settlers, whose principal focus was agriculture, were businessmen and administratorsland agents, merchants, government officials and military personnel, and lawyers. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established a government for the newly developing territory; the Treaty of Greenville (1795) helped to allay fears of Indian attacks. Whereas the West had a population of 150,000 by 1795, that figure exceeded 2.2 million by 1820.[3]

Settler arrived in the West primarily by one of four principal routes: from southwestern Virginia overland through mountain passes and along rivers to Kentucky and Tennessee; across Pennsylvania on the Pennsylvania Road to Pittsburgh (on the Monongahela); through Maryland on the Cumberland Pike to Pittsburgh or to Wheeling (on the Ohio); and across upstate New York to the Great Lakes and on to northern Ohio. When traveling west by the Pennsylvania route in 1810, Connecticut native Margaret Van Horn Dwight, niece of the president of Yale College, believed that "the State of Ohio will be well fill'd before winter, Waggons without number every day go on." Morris Birkbeck, an English gentleman farmer who settled in Illinois, was more emphatic a few years later in 1817: "Old America seems to be breaking up, and moving westward." His contemporary, British traveler John Bristed, explained the phenomenon: "The Americans are unquestionably the most locomotive, migrating people in the world. Even when doing well in the northern, or middle, or southern states, they will break up their establishment, and move westward with an alacrity and vigor that nothing but the necessity of adverse circumstances could induce in any other population." The dangling carrot was, of course, the opportunity to acquire land at a low price.[4]

Both Birkbeck and Bristed assessed the magnitude of the eastern trade to the West, although their figures vary. The number of freight wagons traversing the 300 miles between Philadelphia or Baltimore in the East and Pittsburgh at the gateway to the West was between 12,000 and 20,000 annually. The average burden of a wagon was 35 to 40 hundred weight. Birkbeck noted the cost of carriage was about $7 per hundred weight. Bristed suggested that freight charges exceeded $2,000,000 annually, but the figure may well have reached $5,600,000, as calculated using the high figures. Business expanded as new modes of transportation were introduced and old land routes improved: turnpike roads were built; the Erie Canal, which opened in segments across New York state to Lake Erie (and beyond through connector canals), was completed in 1825; and steam transport was inaugurated on the eastern and western waters in the 1800s and 1810s.[5]

Eighteenth-Century Design

The principal vernacular chair throughout America in the 1790s was the bow-back Windsor side chair (fig. 1). Philadelphia, where the pattern was introduced in the mid-1780s, was the leading producer. The new round back was accompanied by turnings simulating the appearance of bamboo. Appropriately, one of the popular finishes during the 1790s was "straw" colored paint, frequently accompanied by "penciled" striping of contrasting color in the bamboo grooves. Other painted lines accented the beads of the convex bow face and the groove delineating the flat spindle platform at the back of the seat. During the 1790s bow-back Windsor side chairs were the first choice for dining furniture, as indicated by frequent references to "Dining Windsor chairs," or simply "dining chairs," in household inventories throughout the East. The popularity of Windsor side chairs for this purpose continued through successive patterns until the mid-nineteenth century.

William Cox, whose brand is stamped under the seat of figure 1, had arrived in Philadelphia in the 1760s, probably from neighboring Delaware, and likely trained or completed his training with a city craftsman. He had set up in business for himself by March 8, 1768, when he took on an apprentice- William Widdifield, a poor boy, who later had a successful chairmaking business of his own in the city. Throughout his long career (d. 1811), Cox enjoyed the patronage of a number of prominent individuals, including Gen. John Cadwalader, Gen. Henry Knox, and merchant Stephen Girard. Cox furnished dozens of Windsors for Girard's extensive export business along the coast and in the Caribbean. The chairmaker delivered one group of "24 straw colour'd chairs" priced at 10s. apiece to Girard in March 1791. Four months later he supplied the merchant with a dozen "Green Dineing Chairs" and six companion "armd Windsor Chairs," the charges per chair calculated at 9s. and 15s., respectively. Cox also shipped chairs independently to coastal destinations, including Fredericksburg and Petersburg, Virginia, communities accessible via the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.[6]

The bow-back side chair of figure 2, with its lightly waisted back, is a basic copy of Cox's chair. The embellishments are evidence it originated outside the city. The outstanding feature is the decorated bow with its deeply channeled wigglework, which appears to be contemporary with the chair. (An almost identical undulating border ornaments the seat of a bow-back rocking chair from Frederick County, Maryland. The maker of that chair gouged the wavy channel into the spindle platform and around the front posts, bow ends, and spindles.) The arrow-like ornament in the center spindle is comparable to motifs on fancy Baltimore seating, although the feature sometimes appears in documented early-nineteenth-century Philadelphia Windsors. Several other elements in figure 2 relate to Philadelphia work. The modeled seat is a slightly later version of the plank seat in Cox's chair: the front pommel has been eliminated and the front and side edges are rounded. The medial stretcher turnings are fuller. Aside from the decorative wigglework, only the full-swelled side braces indicate that the chair has a rural origin.

A different focus is manifest in the work of rural Pennsylvania crafts men of German descent. Their highly mannered chairs would hardly be mistaken for metropolitan products (fig. 3). The backs are broad and flat, however the nipped waist is retained. Although the depth of the seat is no greater than that in the Philadelphia chair, an awkward profile results from the extreme breadth of the seat, which produces a modified back curve. The pinched configuration of the spindles at the scat platform accentuates the awkward curve. The support structure also sets Pennsylvania German Windsors apart from all others. A dual leg system-bulbtipped front feet and tapered back supports-appears nowhere else in eighteenth-century work. The Pennsylvania German Windsor is basically a turner's chair. The craftsman lavished skill on the roundwork rather than on the unity or proportions of the design.

Figure 3 is one of only a few Pennsylvania German Windsors identified by a maker's brand. Michael Stoner (Steiner; d. 1810) was probably working in Harrisburg when he constructed the chair in the early 1790s. Within a few years he had removed to Lancaster and modified his design by adopting a more regular spindle placement, comparable to that in Philadelphia Windsors (see fig. 1). Stoner, like many chairmaker-turners of his day, was also a cabinetmaker.[7]

Figure 4 is a chair of broad seat, the oval bottom a Pennsylvania German alternative to Stoner's shield-type seat. The oval plank is a full 11/a" wider and 1 1/4" shallower than that in Stoner's Windsor. The proportions in the upper structure are even more exaggerated than those in the typical Pennsylvania German chair (see fig. 3). This rural craftsman's choice of an exceptionally wide, shallow seat led to sizable voids between the spindles and bow ends. Structural stability for the flat back required that the bow terminate near the forward edge of the plank. Another common Pennsylvania German feature is the elongated leg baluster ith a necked base. The chairmaker rejected the dual leg system in favor o fvheavy cylindrical- feet with sharply tapered toes. The overall clumsiness of the design and the presence of a medial stretcher turned with two sizable lumps suggests that the craftsman was working out of his element. The profile of the feet further links the chair directly to German chairs from west of the Susquehanna, principally in York, Adams, and Frederick counties on the Pennsylvania-Maryland border. The specific chair, which is one of two known, is related to two broad, oval-seated fan-back Windsors with comparable, though slimmer, turnings. Those chairs have family histories associating them with Frederick County. In summary, figures 2—4 clearly represent the variability of the design-transfer process. Structure, proportions, and ornament were all features of transmission, sometimes singly, often together.[8]

A number of Windsor chairs documented to the shops of William Pointer and of brothers (?) Andrew and Robert McKim in Richmond, Virginia, appear to relate to Windsor seating produced in the late eight-teenth century in rural Pennsylvania and Maryland, although the nature of the association is unclear. The clustered spindle placement at the back of a chair labeled by the McKims (fig. 5) is too mannered to be accidental, particularly when other chairs made in the two shops are constructed to normal patterns. The McKims, who were partners between 1795 and Andrew's death in 1805, produced fan- and bow-back Windsors (and perhaps other undocumented patterns), along with a few square-back writing-arm chairs. Their earliest bow backs were framed with baluster-turned supports; chairs with simulated-bamboo turnings followed. The elongated leg balusters in the McKims' chair, which are also present in the work of William Pointer, are distinctive. The profile of this element compares with that in figure 4, suggesting a relationship. The small spool and thin ring turnings between the balusters and feet of the McKims' chair link the Windsor to other Germanic work produced in the Pennsylvania-Maryland border region. Since the backgrounds of the McKims and Pointer are unknown, it is possible that one or the other had family connections in that area. Although the German community in late-eighteenth-century Richmond was small, it included a chairmaker by the name of Samuel Scheerer; perhaps there was a working relationship between the craftsmen.[9]

Nineteenth-Century Design before 1815

An early-nineteenth-century example of the westward transmission of design by a migrating craftsman is found in the career of Andrew McIntire. He was probably a young man in 1773 and 1775 when he was listed as a joiner in Lower Chichester township, Chester (now Delaware) County, Pennsylvania, tax and land records. He lived in neighboring Philadelphia by 1785 when the first city directory was published; he is further identified as a cabinetmaker in the city tax list of 1786 and the directory for 1793. Between the latter date and his death at Pittsburgh in 1805, McIntire's activity is unrecorded; however, insights may be gained from a lone documented chair (fig. 6). Square-back seating was introduced to the Windsor chairmaking trade at Philadelphia in the late 1790s (fig. 7). The earliest had a low-arch top, or bow (bowed in a lateral direction), which echoes the arclike curve of the seat front. The design was short-lived, superseded before 1800 by a square-back that had one or two turned top members (fig. 8). McIntire appears to have remained in Philadelphia just long enough to become familiar with the low-arch pattern before making the westward trek.[10]

McIntire's adaptation of the Philadelphia low-arch Windsor (fig. 6), which is branded on the plank bottom with his name and place name, can be distinguished from the prototype by several subtle features. The flat, beaded back posts of McIntire's chair lack the flare of the Philadelphia style, but as in that chair, he carried the beading across the top piece. The seats also vary in shape. Even before the new square back was introduced, Philadelphia chairmakers had begun to flatten the rounded front and side edges of the plank. In this respect, McIntire's chair seat is more modeled than the prototypes. The medial and right stretchers of the Pittsburgh chair are replacements, although it is likely that both braces originally had swelled centers like the left one. This variation of the common bamboo medial profile in Philadelphia chairs is suggested by the use of plain spindles in the chair back. Although beaded square-back chairs are uncommon, the Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven, Connecticut) has a large settee in this pattern. A related, square-back writing-arm chair labeled by Andrew and Robert McKim of Richmond, dated "1802," and a comparable example with a tradition of descent in a Madison County, Virginia, family, introduce a further dimension to the diffusion of the design.[11]

During a tour of the West in 1803, Unitarian minister Thaddeus M. Harris was impressed, as were others before him, with the commanding location of Pittsburgh at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers, the last of which was dubbed "the key to the Western Territory." A few years later, John Melish, a British commentator on the manufactures and commerce of America, predicted that "Pittsburg will in all probability become one of the largest towns in America." When Andrew McIntire arrived to take up residence in the town, sometime between 1800 and 1805, he found a fast-growing community consisting of about 4.00 houses and 2,000 inhabitants. Forty or fifty retail stores supplied local needs and those of the hordes of western settlers that streamed through town. Warehouses stored vast quantities of goods conveyed from the East in wagons awaiting shipment by riverboat to Kentucky and Louisiana. The boat-building industry was flourishing. Two glasshouses, a manufactory for the production of cut nails, and various smith's shops had been erected, all benefiting from the close proximity of "inexhaustible mines of coal." Small businesses and craft shops supplied hats, leather, tobacco products, beer, earthenware, cordage, lumber, and cabinetware. By 1807 five manufactories produced Windsor chairs. William Davis, who constructed baluster-and bamboo-leg bow-back chairs in the Philadelphia style, may have been in business during McIntire's residence.[12]

The first commercially successful square-back Windsor had single (or double) turned cross pieces forming the crest. At the top of the line were chairs with small medallions, or tablets, centered in the crest to provide a flat surface for painted ornament (fig. 8). Joseph Burden's side chair is typical of the quality of Philadelphia production during this period. The seat is shaped much as it had been at the introduction of the first squareback Windsors, except that front corners are rounded (see fig. 7). The stout, well-modeled bamboowork is divided into four segments separated by gouged creases, rather than the three divisions common earlier (see figs. 1, 7). The use of four box-style stretchers was another departure from previous design, replacing the H-plan brace. The updated construction was based on the bracing system in the fancy chair, a new type of painted seating with rush or cane bottoms. The fancy chair, a slightly more expensive product than the Windsor, had been, introduced from England in the postwar years and became economically attractive in the furniture trade during the 1790s. Many chairmakers, Burden included, donned two hats and produced both types of seating with ease, since the tools and materials were the same. The move enabled many urban craftsmen to broaden their economic base while remaining specialists.

Crest medallions in the square-back chair were shaped to one of several patterns. Most common are the square and rectangle, both usually formed with hollow (incurved) or canted corners. The small oval was next in popularity. Special shapes, such as hearts and urns, were rare. Chair-makers sometimes produced fancy interpretations of the square-back chair by introducing a small medallion corresponding to that in the crest to one or more of the bamboo-turned spindles (fig. 9). A similar medallion sometimes embellished the front stretcher.

The Philadelphia square-back chair with double bows and a medallion in the crest became popular with craftsmen in towns and villages in the Delaware Valley and eastern Pennsylvania. Along the river, chairmakers in Trenton, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware, made chairs in this pattern. Pennsylvania craftsmen from Bucks County on the Delaware to Franklin County beyond the Susquehanna frequently introduced somewhat mannered features that identify their chairs as rural products: rectangular medallions with square corners; arms with thick tips; and stout seat planks. The delicate ornamental pattern of figure 9 is identified as originating in the shop of a Pennsylvania German chairmaker by the shape and breadth of the seat (see fig. 1, 3). Extensive modeling around the seat edges has lightened the bulk of the plank in keeping with the overall proportions of the chair. At least one mate is known. In a chair of related pattern, an oval medallion in the crest is paired with vertical rectangular tablets in the spindles, producing a less unified design.[13]

Business stalemates during the war years, from 1812 to 1814, wiped out the old Windsor patterns and ushered in new designs at Philadelphia. From then until the early 1830s, mortise-and-tenon framing with slat-style crests positioned between the back posts prevailed. Philadelphia lost its premier position as style setter in vernacular seating as Baltimore became a center of the painted furniture trade. New York chairmakers introduced arrow-shaped spindles ("flat sticks") at about this time, and Boston craftsmen developed the extraordinarily successful stepped-tablet crest (modern, "stepped-down" Windsor), patterned after formal seating furniture. Nevertheless, Philadelphia chairs still had considerable impact on vernacular design within and beyond the local trading region.[14]

An unusual design because of its rarity, even in Philadelphia where it originated, is the slat-back Windsor with a centered rectangular tablet projecting from the crest (fig. 10). Thomas Ashton's chair frame generally duplicates that of Burden's double-bow, square-back Windsor. The seat is one of several shapes in the market during the 1810s and 1820s; the front and back edges are curved in arcs, the sides are sawed in serpentine profiles. Ashton, like William Cox before him, supplied chairs to export merchant Stephen Girard. He also constructed a dozen armchairs, perhaps of this pattern, for the senate chamber of the statehouse at Dover, Delaware, in 1812.[15]

The influence of the Philadelphia tablet-centered crest extended beyond rural Pennsylvania to the Shenandoah Valley. On September 4, 1820, Samuel Fizer, probably a relative newcomer to the chairmaking business, advertised from Fincastle, Virginia, that he was "prepared to execute work in a style that will rival any of the Northern Cities."[16] The design of Fizer's labeled chair leaves little doubt as to the sources of inspiration (fig. 11). Back posts with shaved faces had been introduced to Philadelphia chairwork about 1815 or 1816, and by the 1820s the execution of bamboowork was often perfunctory, as is reflected in the present chair. Fizer's use of a squared seat plank with steep, rounded edges producing a cushioned effect illuminates the impact of Baltimore chairmaking on his work. Knowledge about the seat shape, a common one in the city from about 1805, could have been transmitted to the valley by either of two routes: through Frederick, Maryland, and Winchester, Virginia, or via south central Pennsylvania, where many Baltimore trained chairmakers plied their trade. An almost identical plank is on a square-back chair with double bows made ca. 1807—1815 by John McClintic at Chambersburg near the Maryland border. The community lay adjacent to a major southwesterly thoroughfare passing through Hagerstown to the Virginia back country.

A small group of early-nineteenth-century square-back chairs related through the stout profile of the bamboowork legs has family and recovery histories from rural locations in the Susquehanna Valley, western Pennsylvania, and the Shenandoah Valley (figs. 12, 13). Baltimore styles were the principal influence on these chairs, although a knowledge of Pennsylvania work is evident in some of them. The group consists of square-back Windsors fitted with single-or double-cross bows of Philadelphia inspiration and chairs of a new tablet-style crest developed in Baltimore. Production probably occurred between 1805 and 1820. The vigorously turned legs are frequently accompanied by robust stretchers. Both turnings are heavier versions of the bamboo supports found on some early nineteenth-century Baltimore Windsors. The comparative features in the two chairs are the pointed feet and the pronounced reduction in leg diameter from the bottom crease, or groove, to the top segment. The back posts are slimmer versions of the same Baltimore turnings (figs. 12, 13).

The chair in figure 12 was found in the Quarryville area of southern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, although it may have been made farther west or south. In contrast to the Baltimore influence in the turned work, the shape and detailing of the plank reflect developments in the Philadelphia chair market of the late 1790s when the shield seat was squared, the sides flattened, and grooved beading was added to define the edges (see figs. 7, 8). This plank is thicker than the prototypes, however, and an extra groove marks the side surfaces. The chair's overall mannered character identifies it as a rural product. Another chair in the group, having a single, turned cross piece at the top and a better modeled shield-shape seat, was recovered at Sheppardstown, West Virginia, early in the present century. [17]

The most sophisticated chair with heavy bamboo legs is the one illustrated in figure 13. Every feature is a reflection of Baltimore design, from the turnings, to the oval medallion centered in the back, to the new patterns of the seat and crest. A squared shield-shape seat with a striking center-front projection appeared in the Baltimore chair market shortly after 1800 and continued in occasional use for a decade or more. The projection, as interpreted on figure 13, is narrow, giving it a rudimentary appearance. The distinctive crest was introduced to the Baltimore market probably between 1805 and 1807. The central feature of the winglike design varies: rounded lunette; flattened arch; rectangular tablet; or rectangular projection with hollow corners (fig. 14). The wings vary in height and angularity; some are squared at the ends. One version even has blocked rectangular ends.[18]

The small Baltimore settee in figure 14 is a classic among Windsors. The features, which are more delicate and better designed than those in the rural chair in figure 13, are typical of the best Baltimore vernacular seating of the early nineteenth century: pencil-slim legs and posts; medallion accented spindles and stretchers; carefully modeled seat-front projections; and intricately sawed elements, such as the crest, that provide a design focus. The pattern is neither rare nor common. Several specialized forms were made, including longer settees, a writing-arm chair, and a child's highchair.[19]

The winged-crest pattern was also attractive to craftsmen working outside Baltimore, as indicated by the number of design variants. That, in turn, suggests that Baltimore chairs in this pattern were well distributed. Histories associated with many examples bear out the hypothesis. Figure 13 descended either in the Haupe or Miller families of Greenville, Augusta County, Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley. Its maker may have been of German background, for the crest face is scored near the edges to form a broad bead, and similar scoring is found on the crests of fan-back Windsors made in the German regions of southeastern Pennsylvania in the late eighteenth century. Another chair with a beaded border, one centered with a tablet like those in the settee, has a piedmont Virginia history. A child's highchair descended in the Randolph family living in Boyce, Clarke County, a village near Winchester. A side chair with a flat-arch projection at the crest center came from the same homestead in Frederick County, Maryland, as the mate to figure 4, which has distinctive German characteristics. Chairs with variations of the blocked-wing crest are found in reasonable numbers in western Pennsylvania, south of Pittsburgh.[20]

A crude woodcut accompanying a Nashville, Tennessee, newspaper notice of March 1808 is the basis for dating the introduction of Baltimore winged-tablet chairs to the 1805—1807 period. The woodcut advertising John Priest's chairmaking and painting business contains an image of a side chair with a winged, Baltimore-style crest. Since the initials 1. P appear on the chair seat, it seems likely that Priest made his own printing block. The chairmaker was working in Petersburg, Virginia, in 1806, which is of particular relevance since Virginia communities in the Chesapeake region were directly influenced by Baltimore furniture design. Other examples of the winged-crest chair found in the West include the only standard-size armchair known to date, which is in a Kentucky private y collection. Another Kentucky armchair, one of extraordinary height, has a history of use in an unidentified Masonic lodge. Its enormous crest piece is a rectangular tablet, winged variant of a type often found in western Pennsylvania. The front stretcher and several spindles are also embellished with rectangular tablets.[21]

Post-1815 Slat-Back Designs

By the mid-1810s, large crests for painted, and later stenciled, ornament were increasingly popular features on vernacular seating furniture. Chair backs were framed with either slat-style crests secured by mortises and tenons between the posts or tablet-style tops fixed to round tenons at the post tips or rabbets on the post faces. The basic crest is rectangular; the more ornamental top pieces are arched, scalloped, or shouldered along the upper edge. By mid-century, cut-out shapes were added to the lower edge. Chairs of both styles were marketed simultaneously until the 1830s, when tablet-top designs generally prevailed. For the most part, Philadelphia was the source of the slat-framed styles and Baltimore the source for the tablet top.

The first slat-back Windsors had full-length spindles. Cylindrical sticks, usually five in number, were the plainest option. The introduction of a single smooth-shaved "flat stick," or arrow-shaped spindle, at center back provided another surface for ornamentation (fig. 15). The use of multiple flat sticks, generally four, added variety and provided a smooth surface to support the sitter's back (fig. 16).

The geographic range of Philadelphia-style slat-back chairs with long spindles was broad, covering central Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the West. Documented Philadelphia examples are rare. Unmarked chairs made in both the cylindrical and flat-stick patterns still comprise part of the furnishings at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. The plain-spindle ones, which are framed with bamboo-turned legs and back posts, are likely part of the dozen Windsors the institution purchased from Philip Halzel in 1822. Chairs of identical pattern with seats of a variant shape were labeled by Robert Burchall and William Wickersham of West Chester in neighboring Chester County during their partnership between August 1822 and February 1824. The Athenaeum's flat-stick chairs may date from a few years later. New features are backs in the bent style and cylindrical legs turned with multiple rings, top and bottom, the two bands connected originally with a broad, vertical stripe of paint.[22]

Fancy painted, slat-back Windsors were popular in rural, eastern and central Pennsylvania (fig. 15) . The style featuring a central flat stick flanked by cylindrical spindles was probably slightly less common than the types with all cylindrical or all flat sticks. Documented chairs and chairs with recovery histories link some production to Berks, Chester, Lancaster, and Lebanon counties, east of the Susquehanna, and Centre, Mifflin, and Union counties, west of the river. Seat planks include the range of shapes found in the postwar market: balloon, serpentine, and shovel profiles. The last, which has a blunt front, is the latest in date and the most common.[23]

Slat-style Windsors were popular with chairmakers and consumers throughout Virginia, and, as in the past, such chairs often mixed Philadelphia and Baltimore characteristics. In the case of a bamboo-turned, plainspindle chair labeled by Seaton and Matthews of Petersburg about 1814 to 1818, the squared, shield-shape seat has a front projection in the Baltimore style (see fig. 14) . Slat-back Windsors made at Lynchburg by George T. Johnson and the firm of Johnson and Hardy (Chesley) in the early 1820s were divided between straight-back (canted) and bent-back patterns. The chairmakers' cheapest Windsor had plain cylindrical spindles. The introduction of a central flat stick increased the price slightly. Across the southern Virginia border, Moravian craftsmen at (Old) Salem, North Carolina, made slat-back Windsors that are well proportioned and have shapely bamboo-work, good leg splay, and seats that are a better contoured version of the Baltimore "cushioned" planks Samuel Fizer of Fincastle, Virginia, used in his chairs during the 1820s (see fig. 11). The influence of Pennsylvania work on chairmaking at Salem may have been direct, since the community had frequent communication with the Moravian settlements in eastern Pennsylvania.[24]

The slat-back Windsor is among the earliest patterns documented to western production. The distribution of manufactured goods at Pittsburgh and Wheeling helped to keep westerners abreast of furniture trends in the East. In 1817 Pittsburgh had seven cabinet shops and three Windsor chairmaking establishments, the latter employing a total of twent-three workers and realizing gross sales of more than $42,000 annually. Many of the "country towns" along the waterways had become "miniature cities," some with their own resident chairmakers. Western growth was phenomenal. The population of Ohio, estimated at 45,000 in 1800, rose to more than half a million by 1820, Cincinnati becoming the most Important business center between Pittsburgh and the lower Mississippi. It has been estimated that by the early 1820s as many as 3,000 flatboats floated down the Ohio annually, many destined for New Orleans, the great entrepot on the lower Mississippi for the distribution of western produce. Other vessels carried manufactured goods and western migrants to any of hundreds of landing sites along the way. Some prosperous families carried their household possessions with them; others traveled with few personal belongings, buying what they needed or could afford when they resettled.[25]

Steamboats plying the western waters could travel the entire distance between Pittsburgh and New Orleans by 1811. In 1820 alone sixty-nine vessels were engaged in river commerce. Western trade was revolutionized. Before the advent of the steamboat, the upriver trip by flatboat from New Orleans or other points was tedious, consuming several weeks or months, depending upon the destination. Merchandise from the East could now be carried upriver or down to any navigable destination, with a short portage around the falls at Louisville. Although the cost was considerable, John Bristed reported that the charges were still less than half those for freighting the merchandise across the mountains. The Great Lakes region was served via the Erie Canal by the 1820s.[26]

Adin G. Hibbs, a chairmaker who migrated from Pennsylvania to Columbus, Ohio, in 1832, advertised his manufactory at the sign of The Golden Chair the following year. His products included Windsor and fancy chairs in "a large and handsome assortment" (fig. 16). Hibbs's arrowspindle, slat-back Windsor is basically an eastern Pennsylvania chair. The ring-turned front legs are slightly later in date than the bamboo-style legs (see fig. 15); the broadly interpreted shovel-shape seat is contemporary to the early 1820s. Knowledge of Pennsylvania design is also evident in the work of Nathaniel Sprague of Zanesville (1823) and, later, McConnelsville (1827—1830s). Sprague may have vended his flat-spindle, slat-back Windsors along the Ohio River by way of the navigable Muskingum. The sharply tapered legs in a chair owned by descendants indicates that the chairmaker was also influenced by Baltimore design. A shop inventory of Moses Hatfield, a Dayton resident in 1835, provides further evidence of the popularity of slat-back Windsors in Ohio with the items: "1097 chair backs" (slats); "33 slat-backs" (framed and finished chairs) valued at $44; "72 slat-backed primed" worth $48; and "30 slat-backs finished."[27]

Indiana furniture is almost unknown, at least in published sources. A long, slat-back Windsor rocking settee with slim, flat sticks in the back, slat-style stretchers (front and back), and heavy arms scrolling forward in the manner of a rocking chair is said to have descended in the Newman family of East Germantown (now Pershing), Wayne County. A contemporary, related slat-back settee, labeled by the Louisville, Kentucky, partners James Ward and John M. Stokes, demonstrates the possibilities for variation within the pattern. The long seat, which has similarities to the Newman family settee in the spindles and slat-type stretchers, a brace that first appeared in the 1830s, is framed with an extra post at midback. The flat arms are mounted horizontally and terminate in large rounded pads at the front; the legs are stouter than those on the chair in figure 17, with the addition of a ball turning near the top.[28]

The chair illustrated in figure 17 is a rare documented Tennessee example. It was made in the Nashville shop of Alexander H. and William R. Wood, who were in business together from 1817 to 1820 and possibly later. The rear view emphasizes the unusual feature of the chair, the acutely angled back. As young men, the Wood brothers had trained at Richmond, Virginia, with Robert McKim, whose Windsor seating was heavily influenced by Philadelphia and Pennsylvania German design (see fig. 5). In an advertisement of 1819 the Woods made special note of their auxiliary business of sign and ornamental painting.[29]

Generally speaking, the Wood brothers' chair is a Philadelphia Windsor. The most distinctive modification to it is the sharp back bend. Since bent backs were used for Windsor seating at New York some years earlier than at Philadelphia, where the style was introduced only about 1816 or 1817, the brothers may have become acquainted with the feature through importations of New York seating into Richmond during their training in the early 1810s. The choice of a bent back may also reflect influences present in Tennessee. For example, James Bridges of Knoxville advertised in 1819 that he had "spared no pains or expense in procuring. . .Workmen of the first description" from New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington. Samuel Williams, a local competitor of the Woods, also employed New York journeymen along with workers from Philadelphia. Baltimore influences on the Wood brothers' chair are the sharply pointed feet and pronounced leg tapers. Chairs made at Pittsburgh, a community exposed to the cross currents of Philadelphia and Baltimore furniture design, probably also had some impact on the regional market long before 1830 when John Rudisill of Jackson, Tennessee, advertised that he had just received "a large assortment of WINDSOR CHAIRS, manufactured at Pittsburgh, of various patterns and colors."[30]

During the late 1820s Philadelphia chairmakers introduced a slat-back chair of a new style with short spindles in the lower back below a rectangular cross piece to the greater Delaware Valley furniture market. An example used in a bank in nearby West Chester about 1837 has bold spindles centered with ball turnings. Judging by the rarity of surviving examples, the plain rectangular crest was quickly superseded by several variant designs. One pattern -a slat with a low top arch -was particularly popular in eastern Pennsylvania and the Delaware Valley (fig. 15). Sometimes sawed, scalloped decoration was added at the center top. All variants were available before 1838 when James C. Helme of Luzerne County compiled a manuscript "Book of Prices" for framing and finishing fancy and Windsor seating furniture. The "common straight back" and "bent back" chairs on his list are Windsors with full-length spindles. The chair in figure 18 is a "Ball Back Chair with 2 Bows." The expense of producing this chair was one third more than a long-spindle chair. The addition of a scalloped top to the crest raised the figure to 50 percent above the basic cost.[31]

The arched slat-back, short-spindle pattern had a long life. Thomas Thompson Enos, whose chair is illustrated in figure 18, did not attain his majority until 1838. He probably framed chairs of this pattern during his first years in Smyrna, Delaware, prior to moving to neighboring Odessa, which place name he penciled on the seat bottom. William F. Snyder, who made similar chairs at his Mifflintown Chair Works in Juniata County, Pennsylvania, northwest of Harrisburg, was born only in 1845. Another set of chairs bears the signature of H. L. Rhein (owner?) of Reading, Berks County, a community on the Schuylkill. The arched slat-back Pennsylvania chair appears to have been a popular export item, as well. Chairs of this pattern are encountered with some frequency in the coastal South, although none are documented to southern production. Several dozen were acquired by the Masonic Lodge of Suffolk, Virginia, near Norfolk, during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Another example was found in Clarke County, Georgia, probably transported inland by river vessel and wagon from Savannah, the second largest, early-nineteenth century, southern entrepot for Philadelphia vernacular seating furniture after Charleston, South Carolina.[32]

Despite the success of the Philadelphia (and area) arched slat-back pattern in southern markets, the plain slat-back design was the one reproduced by southern and western chairmakers. At Lynchburg, Virginia, Chesley Hardy made a chair reasonably close in design to Enos's, except for the slat modification, during the 1830s or 1840s. The pattern more commonly constructed, however, is one with short, broad, flat sticks in the lower back. A particularly handsome example with two, instead of one, midback cross slats was made for the Single Sisters' House in the Moravian settlement at (Old) Salem, North Carolina. Single-cross slat chairs, some with broad spindles others with narrow ones, have descended in Tennessee families. An 1840s flat-spindle chair was made at Wheeling, West Virginia, by Jonas Thatcher (fig. 19), one of a number of chairmakers there between the late 1820s and the Civil War. Its spindle and front-leg patterns are based on Baltimore prototypes (see figs. 22, 23, later in this article). Plain, slim rear legs pinched together near the top are the usual accompaniment when Baltimore styling is prominent. Front stretchers in the form of slats were common in the late 1830s and early 1840s when Thatcher worked.[33]

Visitors to Wheeling in the 1830s complained of the city's soot-air, as they did of Pittsburgh. The region's bituminous coal deposits, which were important stimulants to industry in both communities, were mined as a local energy source and an export product. In the mid-1830s the population of the city stood above 10,000, many residents drawn there by the flourishing river trade. Warehouses filled with merchandise for the West lined the Ohio River; boat builders and owners, and wagoners prospered. In 1836 the city wharfmaster logged 1,602 steamboat arrivals and departures; 222 keelboats and flatboats carried other freight down the river.[34]

Several pieces of Windsor slat-back furniture are attributed to Kentucky. One is a writing-arm chair with short, flat sticks in the lower back; the other is a settee with diamond-shaped sticks and a front stretcher of the same profile. The slat-back pattern was apparently also popular in Indiana. German-born Jacob Maentel, who moved from Pennsylvania to New Harmony, Indiana, in 1838, painted a number of area residents posed in domestic settings furnished with slat-back chairs that had flat sticks in the lower back (fig. 20) . In a review of Maentel's Pennsylvania paintings, slat-back chairs with single midback slats substituting for spindles and slat-back chairs with long cylindrical spindles are the patterns delineated, a circumstance that strongly suggests Maentel was depicting chairs common to each area.[35]

Post-ins Tablet-Top Designs

Five years or more before slat-back patterns appeared on the Philadelphia market (see fig. 10), Baltimore's Windsor chairmakers were producing a tablet-top design adapted from fancy-painted, cane-seated furniture (fig. 21). These prototypes had been available locally for several years, probably perfected by the Finlay brothers, Hugh and John, who commenced their chairmaking business in 1803 (fig. 22). The sawtooth borders on the Windsor crest of figure 21 were copied directly from that on fancy chairs, although such ornament was probably produced by more than one local artisan. In an advertisement of 1805, the Finlays offered customers a broad range of decoration, including "trophies of Music, War, Husbandry, Love, &c.," that may have closely resembled the centered crest ornament of the illustrated Windsor.[36]

The structural units in the tablet-top Baltimore Windsor (fig. 21) represent a basic vocabulary of vernacular seating design current in the city and surrounding regions during the early nineteenth century. The elevated crest, though plain in outline, is the focus, since it received the principal decoration. Rounded crest shapes were introduced with the late patterns (see figs. 29, 31, later in this article). Cylindrical back posts are a major characteristic of the Baltimore style. The turnings became progressively thicker with time (see fig. 25) and sometimes were augmented with bulging, rounded shapes. The seat-front projection, a special customer option, remained only through the 1810s (see fig. 14). The pronounced leg taper of figure 17 is already present here, above and below the inset ankles, and remained a staple of the Baltimore design vocabulary beyond mid century (see fig. 34 later in this article). Small, varied-shape medallions centered in spindles and front stretchers are found only in the best work, since such embellishment required extra labor on the part of both the chairmaker and the ornamenter.

The early Baltimore tablet-top design migrated beyond the immediate environs of the city within a decade of its initial development. Representative of the transmission is a group of northeastern Tennessee side chairs of unusual hybrid design, combining a Baltimore rectangular tablet and a Philadelphia-style central crest projection like that in the Ashton and Fizer Windsors (see figs. 10, 11). Several chairs have heavily mannered bamboo leg turnings of the type found in figures 12 and 13. The most sophisticated example has a center-back spindle featuring a medallion and a projection at the seat front, both ornamental elements borrowed from the Baltimore design vocabulary. [37]

A sizable body of special-purpose tablet-top seating furniture consists of bamboo-turned, writing-arm chairs of Virginia origin, ranging in date from the early 1800s to the 1820s. Most tablets on them are moderately deep with squared corners. The backs are of medium height, and some are centered with medallion spindles. The earliest chair in the group has an eighteenth-century-type, H-plan stretcher system and a shallow crest rounded at the upper corners. It belonged to lawyer William Wirt, who probably purchased the chair in Richmond, his sometimes residence beginning in 1800. The chair has several features similar to those in a writing-arm chair labeled by the McKim brothers of Richmond and dated "1802." The Wirt chair probably dates slightly later. Another chair has a history in the Carr family of Port Royal, Virginia, a small community on the Rappahannock River, near Fredericksburg, which was accessible by water from Richmond. The latest chair in the group, which descended in the Stoner family of Botetourt County in the Shenandoah Valley, could well have originated in that area. The lower back posts are distinctively styled with a rounded taper identical to that in chairs made by George T. Johnson and Cheslev Hardy at Lynchburg, due east in Campbell County. [38]

Greater impact occurred on the vernacular seating trade in the I820s when a neoclassical-style Baltimore tablet-top fancy chair with heavy, sawed elements and bold turnings was successfully marketed (fig. 23) . The outsize crest, finished with an applied, scrolled lip at the upper back, provided a broad surface for painted ornament. The distinctive baluster posts were supported on large, multiringed oval balls, frequently repeated at the leg tops. The same ringed balls occur in English furniture of the late George III period, examples of particular note found in the pedestals of dining tables. The single cross slat of the chair back provided structural stability, comfort, and a surface for additional ornament. The unusual side pieces framing the seat are Grecian in concept, truncated to form platforms for socketing the back structure. The stout front legs are turned to a Roman pattern. The domed turning at the top was a popular alternative to a multiringed ball. The ring centered in the concave element below the dome was termed a "gothic moulding" in furniture circles.[39]

Neoclassical Baltimore tablet-top chairs were widely marketed in America and abroad. City chairmakers advertised chairs for export in units up to several hundred dozen. Regional newspapers at such locations as Easton, Maryland, neighboring Frederick County, and Norfolk and Petersburg, Virginia, repeated the urban advertisements. Family histories associate other Baltimore chairs with Raleigh, North Carolina, Annapolis, Maryland, and even Ontario, Canada. John Hodgkinson, who made the chair in figure 23, set up shop in Baltimore about 1820. His career spanned several decades.[40]

Few plank-seat chairs are as close copies of the Baltimore tablet-top fancy style of the 1820s as that illustrated in figure 24, aside from several known Windsors of Baltimore origin. The variations in the turnings are those normal even in Baltimore work. The chair bears the label of William Cunningham, who worked in Wheeling, West Virginia, from 1828 until his death in 1851. The label is also inscribed in ink with the name of the purchaser: "Dr James Wood/Fairview." Fairview, a private residence, was located just south of Wheeling overlooking the Ohio River. Without the label, there would be little question that this was a Baltimore chair.[41]

A simpler style inspired by the Baltimore tablet-top pattern was typically framed with plain, stout back posts accented with ring turnings (fig. 25). The posts were an updated version of the slim supports of the early tablet-top chairs (fig. 21). Shovel or balloon shapes were commonly chosen for the Windsor planks. Frequently, the front legs were turned to a pattern plainer than those on the more expensive fancy chairs. The crests were usually lipless. The medium blue-green paint and yellow banded and penciled decoration of this chair are original. The banding appears to have once been bronzed; the scene on the crest was painted in grisaille. The buildings have a decided European appearance and may be based on a print source or copied from a piece of pottery. The painter may also have been a German, since an old chalk inscription on the plank bottom points to an original or early location of the chair: "W Ebbeck/Elizabeth Town/Lancaster Co./Pa."[42]

Two sets of documented Windsors are known in the tablet-top, stoutpost pattern. One set-six chairs en suite with a settee-has the multiringed-ball feature at the leg tops. The tablet tops are skillfully painted with landscape scenes. The chairs were made during the early 1830s in the Carlisle, Pennsylvania, shop of Cornelius E. R. Davis. Chairs framed by William Bullock either at Carlisle or Shippensburg were far simpler in design. He turned both front and back legs in a plain style, and the front stretcher lacks extra embellishment. A chair with a later rounded-end tablet top and turned work almost as plain was made in West Virginia by William Graham, who migrated from Carlisle to Wheeling. Occasionally, a chairmaker framed his Windsor seating with a fancy, sawed slat at midback in place of the plain rectangular one.[43]

Throughout the years, many Baltimore-style, tablet-top Windsors have turned up in the Susquehanna Valley and central Pennsylvania. Some are versions made by local craftsmen; others represent the work of Baltimore-trained craftsmen who migrated north. The Baltimore city directory of 1829 lists forty-four practicing master chairmakers and eleven turners, some of the latter probably jobbers who supplied parts. Many masters employed journeymen and trained apprentices. When times were slack or indentures expired, some men traveled north in search of work. Baltimore is advantageously located south of the Susquehanna and Cumberland valleys, semirural regions where agriculture and light industry flourished. Baltimore-style tablet-top chairs were common everywhere in the region. Through drawings depicting community life, Lewis Miller, carpenter and chronicler of York, documented the presence of tablet-top seating in local households and businesses. The style reached Lafayette in west-central Indiana in 1839 when William Bullock migrated from Shippensburg, Pennsylvania.[44]

Tablet-top framing was also introduced to chairs fitted with short spindles in the lower back, similar to figure 18, before the close of the I820s (fig. 26). The neoclassical-style Baltimore fancy chair that inspired the tablet-top Windsor of central Pennsylvania was also the vehicle for introducing similar framing to Philadelphia. The chair in figure 26, however, retains three important features of the Philadelphia style: front legs banded with rings linked by a vertical painted stripe, bent cylindrical back posts shaved to a flat surface at the front, and ball spindles in the lower back. By comparison, the absence of spindles in the Baltimore-style central Pennsylvania chair creates an awkward void in the lower back (fig. 25) .

Abraham McDonough commenced in business in 1830. In the highly competitive chairmaking trade his products would have resembled those of other leading manufacturers; his success was dependent upon his business acumen and a measure of luck. McDonough supplied both the domestic and export markets, advertising that his merchandise was packed "in the most careful manner, either for land or water carriage, so as to avoid all risk of damage." He shipped six bundles of chairs to New Orleans in 1831. Eastern goods could be placed in almost any western market at this date via the water routes through the Erie Canal or the Mississippi at New Orleans and overland by wagon. Before his early death in 1852, McDonough had established business contacts in New York City; Burlington, New Jersey; Wilmington (Delaware or North Carolina); Fredericksburg and Petersburg; New Orleans; Missouri; and probably points in between.[45]

The Philadelphia rectangular tablet-top, short-spindle Windsor was about as popular across Pennsylvania as the spindleless variety (see fig. 25) . The style was also known in the West, where chairs with short flat sticks in the lower back appear to have been somewhat more common than those with short ball-turned spindles. At Wheeling, Jonas Thatcher and a partner named Connelly chose flat sticks for a chair framed about the mid-1840s. Although the sticks lack the small beads of Thatcher's slat-back chair (fig. 19), the general profile is the same; the seats and front leg turnings are also comparable. The turned front stretcher is centered with a ball.[46]

Several Windsors in the Philadelphia tablet-top pattern are ascribed to Tennessee and Kentucky. A set of side chairs similar to the Wheeling example by Thatcher and Connelly descended in a Rutherford County, Tennessee, family. A Kentucky settee (fig. 27) has intricately designed short, flat spindles. The craftsman who made this piece of furniture in the Philadelphia style was also familiar with Baltimore vernacular design, either from first-hand experience several decades earlier or from having examples to study. The profile of his flat sticks is based on an urn shape found in Baltimore fancy seating from the beginning of the century (see fig. 22), with a short, flaring element added to the top. When inverted, the flaring shape is the small dome-on-a-shaft profile found in the backs of cane-seated furniture made in 1814 or 1815 by Thomas Renshaw and John Barnhart of Baltimore. The same domed shape appears in the leg tops of the Baltimore chair in figure 23. The ornamental spindles of the settee contrast effectively with the horizontal emphasis of the large, plain, framing members: tablet, slat, seat, and longitudinal stretchers. The front legs are a degenerate version of a Pennsylvania support (see fig. 19) and, with the posts, lack the sophistication of the short spindles. Just this kind of dichotomy is often encountered in nonurban chairmaking.[47]

Documented and attributable chairs of Ohio origin suggest the scope and nature of eastern influence in the late 1830s and 1840s. The character of the region's chairs derived principally from a fusion of Baltimore and Philadelphia design. One of the most ornamental and successful interpretations is a chair made by William Coles at Springfield, about forty miles west of Columbus on the National Road, a major east-west thoroughfare that stretched from Columbia, Maryland, to Vandalia, Illinois, by 1838 (fig. 28). For all practical purposes, Coles built a tablet-top Philadelphia Windsor from the seat up: the shaved posts and ball spindles are similar to those in figure 26; the seat is a vigorous interpretation of the Pennsylvania shovel-type (see fig. 15). Below the seat, the chair is a Baltimore design: the elements comprising the legs-ball turnings, flaring cones, and tapered columns-are adapted from those in figure 23.

The more common Philadelphia-style tablet-top, short-spindle Ohiomade chair was framed with flat sticks. Documented chairs constructed by John R. and William Wilson at Wooster and James Huey at Zanesville are supported on legs similar to those in Jonas Thatcher's Wheeling chair (see fig. 19). The front stretchers are similar to the forward brace in another West Virginia chair (see fig. 30). Rather than framed with a tablet-style crest, Huey's short-spindle chair has a roll top, an alternative treatment that is perhaps more indicative of New England or New York influence than Pennsylvanian. Another tablet-top chair may also have originated in the Zanesville area, for its ornamental midback slat is closely related to one painted with cornucopias and bunches of grapes in a Huey settee. Wooster and Zanesville were centers of county government: business was usually brisker than in the surrounding communities, offering particular encouragement to artisans, young and old. Zanesville had other advantages. It was located on the National Road, about seventy miles west of Wheeling. From its location on the Muskingum River, Zanesville had access via steamboat to the Ohio River through a system of dams, locks, and short canals. Sixteen miles north at the village of Dresden, the Muskingum joined the Ohio Canal, a commercial waterway extending from Cleveland on Lake Erie to Portsmouth on the Ohio. At Akron, along the canal route north to Cleveland, a connection with the Pennsylvania Canal gave access to Pittsburgh. Hueys trading potential was matched by few.[48]

Surprisingly, documented vernacular chairs of Cincinnati origin are almost unknown, despite the fact that Cincinnati was the most prominent commercial city in the West and dominated the Ohio River trade below Pittsburgh. Carl David Arfwedson, a Swedish traveler in America, reported seeing "some fifty to one hundred steamboats besides other craft" riding at anchor there in 1833. A few years earlier, Frances Trollope had described the quay as about a quarter of a mile in length with space for as many as thirty steamboats to unload at one time. From about 9,600 residents in 1820, the population had risen to almost 25,000 in 1830 and 47,000 in 1840. One commentator suggested 200 to 350 houses were erected each year from 1827 to 1840, despite a disastrous flood in 1832 and economic depressions. Gross sales in the furniture trades amounted to about $400,000 in 1836 and $700,000 in 1840.[49]

William Smith Deming of Newington, Connecticut, who resided in Cincinnati in 1837 and 1838, commented on the cosmopolitan character of the western states, which he described as "composed of every nation on the globe." The Cincinnati directory for 1840, lists 88 chairmakers, turners, ornamental painters, and chair caners and identifies the birthplace of most: 37 individuals were born in Pennsylvania, Maryland, or New Jersey, 11 in Ohio, 10 in Germany or Austria, 9 in Great Britain, 7 in New York, 7 in New England, and 2 in the South. Community awareness of eastern chairmaking trends was high. Isaac M. Lee offered chairs in "the latest and most improved fashions, from the Eastward" in 1829, a statement Samuel Stibbs echoed. The Skinner brothers, Corson C. and Philip, warranted their work "equal to any manufactured in the western country, or even in the eastern Cities." Still other eastern influences were at work in the furniture-making community at large. Philadelphia craftsmen published seven price books for cabinet workers between 1786 and 1828, a practice Pittsburgh and Cincinnati cabinetmakers imitated in 1830; the Cincinnati interests also published another volume in 1836. The distance between East and West was diminishing. [50]

Philadelphia chairmakers introduced a rounded-end tablet to vernacular seating about the mid-1830s (fig. 29) ; it quickly replaced the rectangular crest. Impetus for the pattern derived from a new design in formal seating furniture dating to about 1830: a scroll-end crest sawed at the center top with a tablet and at the lower edges with small, shaped arches flanking a large, vertical, baluster-shaped back splat. Rounded-crest chairs had been current in Europe since the early part of the century but perhaps came to particular American notice only with the publication and circulation of George Smith's Cabinetmaker and Upholsterer's Guide (London) in 1826. The imported title was advertised by Baltimore booksellers in January 1830. A formal Baltimore chair with the new, rounded crest and the baluster splat bears the stencil of Anthony H. Jenkins and is dated 1832 to 1837 by the address and firm name.[51]

A rounded-end tablet-top crest may have been introduced to Philadelphia vernacular seating before it was used on painted furniture in Baltimore, where the rectangular tablet top was popular. A rounded tablet was still current in eastern Pennsylvania, with modifications, after the Civil War. George Turner's labeled chair is a straightforward Pennsylvania design (fig. 29), varying from the McDonough chair (fig. 26) only in tablet shape. Even the front stretcher ornament is similar. A subtle change soon occurred in the rounded-end tablet-top crest. John D. Johnson and John T. Sterrett, partners in Philadelphia from 1843 to 1848, made a chair with the new top piece: they sawed the ends in higher arches and flared the bottom corners outward. This shouldered tablet soon became the norm in local vernacular seating (see fig. 31).[52]

The tablet on a child's chair from Wheeling, West Virginia (fig. 30), falls somewhere between the two Philadelphia designs. Baltimore features, however, dominate the hybrid pattern. The swelled legs with ringed balls at the tops are elongated and inverted versions of the back supports of figure 23. The front stretcher, which is identical to the front brace in the James Huey roll-top chair made at Zanesville, is derivative of an earlier Baltimore fancy chair framed with a sawed, "Grecian," or scroll, back. That fancy chair also had a large medallion centered beneath the crest. Medallion shapes varied from an anthemion to pairs of cornucopias or swans to the present figure a modified Baltimore lyre disguised with floral ornament. Below the cross slat, the flat sticks with small beads in the shafts are virtually the same as those in the lower back of figure 19, a chair also from the Wheeling, West Virginia, shop of Jonas Thatcher.[53]

Mid-Nineteenth-Century Styles

The successor to the rounded-end (fig. 29) and the shouldered-tablet chairs with midback slats and short spindles was the Pennsylvania (and Philadelphia) shouldered-tablet baluster-splat Windsor (fig. 31). Formal furniture provided the prototype. The basic Windsor design is the same as earlier, modified only by a ring-turned front stretcher in place of the medallion brace and a deeper shouldered crest. The substitution of a bold, vertical splat at the center back for the stick-and-slat structure is radical and dramatic. The sizable splat provides an additional flat surface for the lavish display of ornament. John Swint, whose small name brand appears on the plank, had a shop in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, from the mid-1840s. Judging by the number of chairs bearing his brand, his business flourished, and production was substantial. The craftsman's aggressive advertising likely contributed to his success: "Chairs! Chairs! Chairs! the subscriber has removed his Chair Manufactory . . . next door to Schofield's tavern . . . where he keeps on hand or will make to order Chairs and Settees of all kinds."[54]

The shouldered-tablet baluster-splat chair is marked by considerable variety. Some splats are narrow and considerably less curved in profile; a few have an angular bulge at the center (fig. 32). More expensive versions are pierced by a large inverted keyhole or similar shape. Far more variation occurs in the crest. The Swint tablet, sawed with moderate shoulders, a low top projection, and a straight lower edge, is one option. Occasionally, the projection is higher. The latest examples have a scalloped, wavy, or flattened profile and simple rounded ends. Tablets sawed with small arches on the lower edge (fig. 32) are stylistically later than those with a straight lower edge; the usual arch shapes are lunettes and cusps.

In rural Pennsylvania, shouldered-tablet, baluste-splat patterns continued in use long past the Civil War. Frequently, a single shop produced several styles simultaneously. Two cases in point are the shops of William F. Snyder (1845—1921) at Mifflintown, Juniata County, and of James Wilson (b. 1826) of Taylorstown, southwest of Pittsburgh. Snyder became proprietor of the Mifflintown Chair Works established by his father-in-law, probably in the 1860s. He produced short-spindle, slat-back chairs and shouldered-tablet chairs (plain or arched on the lower edge) with solid or pierced splats. Wilson opened for business in 1852 in his native western Pennsylvania, having trained at Philadelphia, where he worked for several years as a journeyman. Wilson's one and halfstoy log structure with a rear shed survives, along with many of his chair templates, or patterns. He produced side chairs, armchairs, rocking chairs, and settees in curved, angular and pierced-splat styles coordinated with crests having rounded, shouldered, or scrolled ends and either flat or lunette-arched lower edges.[55]

A few splat-back chairs have highly stylized crests. An excellent example is the chair in figure 32, one of five with a matching rocker that came from a Shenandoah Valley family living in Rockingham County. The low projection on the square-shouldered crest is scrolled backward, forming a heavy lip, but is otherwise reminiscent of the small center tablet in Samuel Fizer's slat-back chair (see fig. 11) made elsewhere in the valley several decades earlier. The angular splat is uncommon. That in the illustrated chair elicits further comment, having an unusually narrow frontal profile where the neck sweeps into the asymmetrical crest arches. Side pieces curving continuously from the seat to the crest are a Windsor rarity borrowed from the fancy chair (see fig. 23). (Planseat chairs with this feature also turn up occasionally in central Pennsylvania, and an unusual broad-seated example bears the stencil of William Coles of Springfield, Ohio.) The shape is loosely based on the chaise gondole, a chair of French origin, although the immediate prototype may be a design in the 1808 supplement to The London Chair-Makers' and Carves' Book of Prices, which is termed a "Roman" chair. The front legs are a highly stylized form of Baltimore turning, adapted from designs such as those in figure 23. (Other stylized variations of Baltimore prototypes occur in figures 19 and 25.) Even the rear legs are different; the cylinders curve inward sharply above the rear stretcher. The red and black grained surface finished with yellow and salmon-colored banding and penciling is original.[56]

The last nineteenth-century design to fall within the basic tradition of Windsor chairmaking established in the mid-eighteenth century has a round top and,,what is today referred to as a balloon back (fig. 33) . Production concentrated in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Few, if any, chairs predate 1855. The understructure of figure 33 bears a remarkable similarity to the Enos chair made in Delaware about mid-century (fig. 18), suggesting an eastern Pennsylvania origin and underscoring the adaptability of some designs and the importance of interchangeable parts to the trade. Angular splats such as this one appear to have been favored in late Pennsylvania work, and decoration, sometimes lavish, frequently combines delicate penciled ornament with bold fruit and floral motifs. A suite of seating furniture consisting of two rocking chairs and six side chairs has a large painted shell centered in the crest. An inscription on the base of one rocking chair reads: "Painted and decorated by Frederick Fox, Chair Maker, August 25, 1877." Fox was a longtime resident of Reading, Pennsylvania. His side chair is comparable to the one illustrated, with some loss of vigor in the leg turnings.[57]