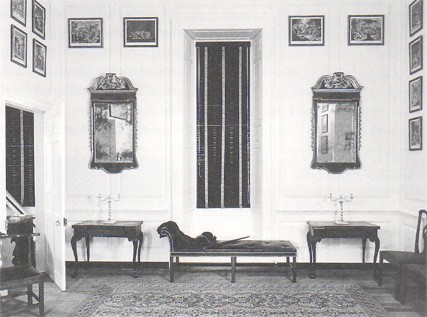

Parlor, Governor's Palace. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The design of the reproduction couch conforms to one that George Washington ordered from Philip Bell in London.

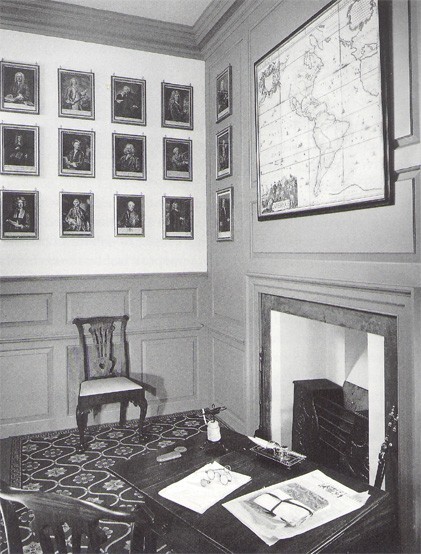

Study, Governor's Palace, showing prints "brass nailed" to the walls. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

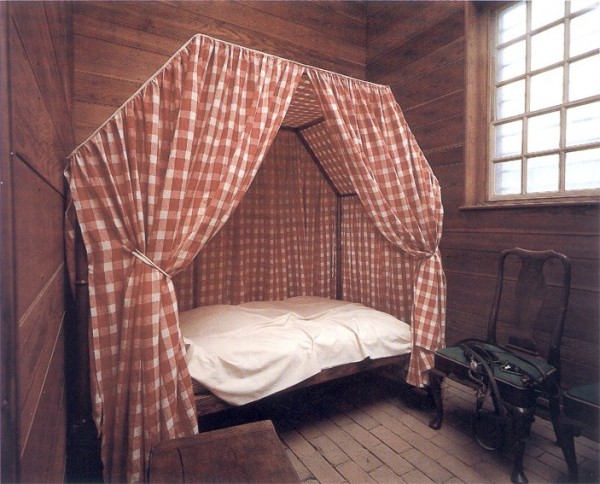

Field bed with red check curtains, stable, Governor's Palace. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Dining room, Governor's Palace. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

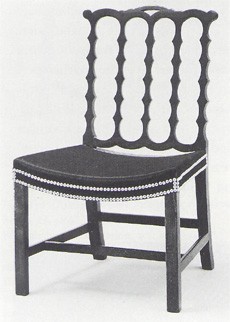

Side chair, England, 1760—1770. Mahogany with beech. H. 37 1/2", W: 22 1/2". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1985-259.) According to tradition, this chair was purchased at the sale of Governor Dunmore's furnishings by a member of the Ambler family; however, identical chairs survive at Badminton, and they could be associated with Botetourt. It is conceivable that this chair was Botetourt's and that it was used by Dunmore after Botetourt died.

Ballroom, Governor's Palace, detail showing the wallpaper and border. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Opposite view of the bedchamber in fig. 4 showing the bamboo chairs. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Arm chair (left), England, 1770-1780. Beech. H. 36 5/8", W. 19 1/2". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1936—344.) A somewhat more robust version of the bamboo chair than the Linnell examples referred to above, this chair originally was painted yellow-white with a glazed overcoat of varnish in imitation of bamboo. The chairs to the right are from a set of twelve reproductions made for the Palace.

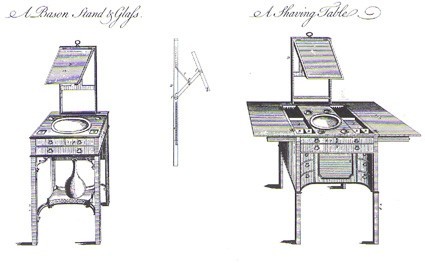

Plate 54 from Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (3d. ed., 1762). (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Nightstand, eastern Virginia, probably Williamsburg, 1765—1775. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 32 3/4", W. 18 1/4". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1985—40.) This nightstand is typical of the sophisticated, London-style furniture made by Williamsburg cabinetmakers during Botetourt's residence.

Plate 54 from Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1st. ed., 1754). (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Firescreen, probably Virginia, 1760-1770. Mahogany with oak and yellow pine. H. 42", W. 74". (Kenmore Association, on loan to Colonial Williamsburg; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

In July 1768 in London, Norborne Berkeley, baron de Botetourt, learned that he was to become the next governor of Virginia, the first full governor to take up residence in the colony in almost sixty years. With a sense of haste brought on by the ministry's alarm at the colonists' fiery opposition to the Stamp Act of 1765 and the subsequent Declaratory and Townshend Acts, Botetourt prepared for his departure and actually embarked in August. He stepped onto American soil at Little England in Hampton Roads on October 26 and that same evening arrived by coach in Williamsburg. By the time of his sudden and much lamented death two years later, Lord Botetourt had endeared himself to a wide range of Virginians and had deeply impressed them with his sincerity, his wisdom, his industry, and his taste.

The remarkable documentation that has survived from this man's English and American careers enables us to gauge the level of his cultural experience in England and identify many of the preparations he undertook and the supplies he ordered for his American residence (about which he was evidently fully informed in London as soon as his appointment became known). It also explains the atmosphere and environment he created in Williamsburg, as the official representative of the king and, further, as a sensitive and sympathetic compatriot of the residents of the distant province. In particular, the evidence contained in hitherto unpublished accounts (reproduced in the appendix) reveals his dealings with a London cabinetmaker and his petty cash disbursements in Wilhamsburg and throws some light on what was considered appropriate for stylish and elegant rooms in a British colony in the third quarter of the eighteenth century.[1]

Born into a west country family of ancient lineage, Berkeley inherited a comfortable estate in 1736, which he proceeded to develop and expand with considerable acumen. He served as a Tory Member of Parliament for Gloucestershire for more than twenty years and maintained a secondary residence in London. In 1746 he had the good fortune to see his sister (and only sibling) become the fourth duchess of Beaufort, which created an important niche for him in one of the most powerful west country families. On the death of the fourth duke (1756), Botetourt became a guardian for his nephew, the fifth duke (then in his minority) -a most influential appointment. A significant presence in the burgeoning port city of Bristol, Berkeley also developed the coal fields on his estates and invested in local brass and copper industries to the point where he became enormously successful, although a major investment collapsed in the period from 1766 to 1768. In 1760 he gained a position as Groom of the Bedchamber at the court of the young George III, the Whigs having finally lost their long ascendency. Four years later he petitioned for and assumed an ancient barony associated with his family, thus becoming a member of the House of Lords and a Lord of the Bedchamber at court.[2]

Although a man of business and a politician more than a connoisseur or collector, Botetourt was a longtime and active member of the Society of the Dilettanti and, through his sister's connections, was involved with levels of patronage that tapped such great figures as architects William Kent, James Gibbs, Robert Adam, and landscape architect Thomas Wright. Painters such as Antonio Canaletto, Joshua Reynolds, and the more pedestrian John Wootton, Thomas Hudson, and Joseph High-more, as well as sculptors like John Michael Rysbrack received commissions to produce works for his family. Leading London silversmiths and even the incomparable Paris firm of Germain made elaborate wares for use at Badminton or the Beauforts' house in Grosvenor Square, London. Botetourt's brother-in-law was a charter subscriber to Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754) and commissioned furniture from the London cabinetmaking firm of William and John Linnell, most conspicuously for his lavish Chinese bedchamber at Badminton. Both Botetourt's nephew and a niece (who married Sir Watkin Williams Wynn) gave extensive patronage to Robert Adam in the 1760s. Through his position at court and his manifest interest in cultural matters, he became familiar with an even wider range of artistic endeavors than his ducal connections would normally have warranted.[3]

Given his rank, his wealth, his connections, and his experience, it was natural that in 1768 Botetourt had a network of accomplished and trustworthy tradesmen to call on whenever he needed additional furnishings and supplies. On learning that he was to depart promptly for Virginia and a new residence, it was perhaps inevitable for him to order items that he believed he would need for his new abode from established, reliable sources. On the other hand, diplomacy-at which he was most adept might have suggested that he reserve some patronage for provincial tradesmen, a well-established practice for affluent patrons with both London houses and country seats. He was, moreover, given detailed information about his new habitat that surely included opinions on the availability and reliability of sources of household supplies (and furnishings) in the colonial capital. This information was sufficient for him, before he left London, to order at the cost of several hundred pounds cut-glass chandeliers, iron warming machines or stoves, and stylish wallpaper with gilt border (plus the necessary materials for installing it) for the Governor's Palace ballroom and supper room (fig. 1). He also directed that his replicas of the full-length state portraits of the monarch and his consort, which he had commissioned earlier from Allan Ramsay, be sent to Williamsburg on completion. Thus he had obviously determined, even before he embarked, that the primary social rooms, in the Palace needed repapering, that they lacked heat, and that they were grand enough to accommodate chandeliers and royal portraits. Clearly he felt sure enough of this information that he decided against waiting until his arrival in Williamsburg before committing to this large expenditure.[4]

Such supplies as mentioned above were obtainable from colonial tradesmen only with the greatest difficulty at best, so it was most practical for Botetourt to order them in London. But much of the furniture that he ordered before his departure could have been procured in Williamsburg from one or more of several cabinetmakers in the colonial capital or in the largest city nearby, Norfolk. The long list of items in Botetourt's account with London cabinetmaker William Fenton in the summer of 1768 contains numerous pieces that Botetourt might have purchased in Williamsburg. For reasons that at this point can only be surmised, he chose not to.[5]

That someone acquainted with Williamsburg would have indicated what goods were available there to Englishmen about to depart for the colony is suggested by an account of comments made in London in 1765 by William Small, former professor of mathematics (and later of rhetoric and moral philosophy) at the College of William and Mary. Small had been a close friend of Francis Fauquier (lieutenant governor and resident in the Palace from 1758 to 1768), and of George Wythe, mentor of Thomas Jefferson during his Williamsburg years. His observations on the colonial capital were reported by Stephen Hawtrev to his brother Edward, who was investigating a post at the college in 1765. Hawtrey had sought out Small in London, through the Virginia Coffee House, and a few days later wrote to his brother what to expect. A professor's rooms in the college, Small noted, had a certain "homeliness of . . . appearance." He continued, "you may buy Furniture there, all except bedding and blankets, which you must carry over; chairs and tables rather cheaper than in England . . . you must [also] have one Suit of handsome full-dressed Silk cloaths to wear on the King's birthday at the Governor's .... As to the rest of your wearing apparel, you may dress as you please, for the fashions don't change, and you may wear the same coat 3 years . . . . Shoes and Stockings are very dear articles."[6]

Although the requirements and the level of sophistication expected of a governor would have been different from those of a young college professor, the situation described by Small presumably would have led any future resident of the colonial capital to think that all but the very smartest items for the most public spaces of a fashionable residence would be obtainable there. There would be savings involved in initial cost and in shipping, and there would be political advantages in the patronage of local tradesmen.

That Botetourt was given information about Williamsburg (probably similar to that described above) before he left London is confirmed by a long letter from George Mercer to his brother James in Williamsburg, dated August 16,1768. George Mercer, Virginia agent for the Ohio Company was in London petitioning, among others, the Earl of Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the colonies, for a government post. In his letter (known only through a nineteenth-century transcript), Mercer confided that Botetourt had "employed [him] as his councillor as to the first arrangement of his family affairs in Virginia." Mercer claimed that he had given the governor-designate advice and information "such as indeed it is impossible any one about him could have given." Mention of a number of contemporary Williamsburg names and a long, careful assessment of Botetourt's character and qualities that corresponds remarkably closely to the many evaluations made by Virginians two years later, after the governor's demise, lend real credence to Mercer's claims, although caution in interpreting his remarks is necessary. He noted, for instance, "I wrote to your Landlord Mr. Nicolson to take the conduct, and direction of his Lordship's Household, till he arrives, and have told him his character -I wish he may be of use to him, however he will supply him genteelly for his trouble now, and will use him in his way of business for the future." The landlord was presumably Robert Nicolson, tailor, who advertised for lodgers as early as 1766, and who had a business connection with James Mercer. Botetourt certainly did use Nicolson in his way of business, but the surviving account (lengthy as it is) does not begin until November 1769, a year after the governor's arrival.[7]

It is also possible that Catherine Fauquier, widow of the late lieutenant governor, called upon her husband's successor before his departure from the city. She had returned to London in 1766 after an eight-near residence in the colony. Such a thoughtful and genteel gesture would have provided Botetourt with a singular insight into conditions in Williamsburg in general and in the Palace in particular. It is also possible that one of her two adult sons, who had spent periods of time in the colony, paid visits of compliment and offered information and observations. Either visit would have been of particular interest to Botetourt since he had been approached by the executors of the late lieutenant governor's estate in Virginia to determine if he would purchase furnishings left in the Palace at the time of Fauquier's death. Botetourt had accepted the offer and acquired almost £500 worth of goods, in addition to the contents of the well-stocked cellars and one female slave. Though this seems an ample sum, and the list of goods is a lengthy one, these items (the furniture especially) constituted only a relatively small proportion of the more than 16,000 items listed in the sixty-one living and working spaces of the Palace at the time of Botetourt's death two years later.[8]

Botetourt's surviving account with London cabinetmaker William Fenton (see appendix), which includes items clearly destined for Williamsburg, begins with orders dated May 7 and May 20,1768. These are problematical since it is unclear whether the furnishings were intended for Botetourt's London townhouse, or his country house near Bristol, and were later perhaps diverted to Williamsburg. Very probably Fenton had supplied his aristocratic patron with furnishings before his appointment as governor; he certainly continued to supply labor as well as goods for Botetourt's London townhouse while the latter was in Virginia.

No settee is listed in Botetourt's Williamsburg inventory, which is somewhat unusual for he had one stuffed and repaired by Fenton (possibly for his townhouse) and purchased another from Fauquier's estate for £6 (Virginia currency). He purchased a couch, too, from the same source for £2. Two couches are listed in the Botetourt inventory, one specified as mahogany in the parlor (fig. 2), the other as "ticken" in the butler's pantry. Both were equipped with check covers.

Botetourt kept a reading desk, along with a library table and a mahogany desk, in his dining room in the Palace. Possibly it was the same one that Fenton repaired in May 1768 with a new hinge. The large print frames complete with glass and packing case from Fenton could have been intended for the library in the Palace, along with the seventeen others that were "brass nailed" to the walls there by Joseph Kidd in November 1769 (fig. 3); or for the butler's pantry, among the fourteen there. To achieve the decorative effect in the library, Kidd needed some of the "16 Doz of brass headed Stoco nails of Differant Sorts" billed by Fenton on August 12. Though numerous maps, some of them framed perhaps, were listed as Botetourt's property, the only other prints listed in the residence were "standing furniture"-the property of the colony, left by or purchased from previous occupants. No prints were transferred from Fauquier to Botetourt, a surprising omission. Spring curtains were known at the Palace but, again, they were the property of the colony. No other curtains listed in the Botetourt inventory were specified thus. The bedside carpet, 6' 9" long, in Fenton's bill may well have been one of the two "bed carpets" or the more tersely noted "carpet" that were listed in the three principal bedchambers of the Palace (fig. 4) .[9]

With Fenton's entry of August 7, the destination of the items becomes clearer. The "Large feild bedstead on Castors with Crimson Check furniture made up with lace proper" complete with two mattresses, bolster, two pillows, two blankets, and a quilt with linen backing was supplemented by six identical beds (three of which had quilts with woolen backs and lacked the pillows-for a slightly lower price), all for a total cost of £106.10.0. This not inconsiderable sum was laid out for the principal servants' bedchambers in the Palace. Two years later, Botetourt's Williamsburg inventory included seven field bedsteads-four of them specified as mahogany and six of them listed as complete with red check curtains (fig. 5). Two stood in the garret room probably occupied by the butler, William Marshman, and under butler, Thomas Fuller; one in the garret room of Silas Blandford, whose post was equivalent of land steward; one in the cook's bedchamber, occupied successively by Thomas Towne, John Cooke, William Sparrow, and Mrs. Wilson, a local woman; one in coachman Thomas Gale's room; one in groom Samuel King's room; and a small one with green and white cotton curtains in the room of gardener James Simpson and his successor James Wilson (son of the last cook).[10]

It is possible that the last bed listed above, distinguished by its different colored curtains and "small" size, was the one Botetourt bought from Fauquier's estate for £4-considerably less than the sum Fenton charged for each of his. If so, one of the new beds probably stayed in England. Even at that, the cost of supplying beds for the governor's principal servants amounted to approximately one year's salary for them all together. That Botetourt judged it appropriate to purchase the beds in England, that he did not defer the decision until after his arrival in Williamsburg where he might have acquired similar furniture, new or used, from cabinetmaker Benjamin Bucktrout, for example, who bought from Fauquier's estate "a parcel bedsteads" for £1.10.0, is a significant commentary on the status of his servants in Botetourt's mind, or perhaps of their expectations in signing up for service abroad with him.[11]

The remainder of Fenton's August 7, 1768, bill consisted of large quantities of Wilton carpet and green "bazse," only obtainable from England. The carpeting was probably chosen for the supper room, the library, perhaps the dining room, and the ballroom. Carpets for the first three rooms listed above were itemized in the inventory (although several had been taken up for the summer and were thus in storage). Wilton strip-carpeting must have been destined for the ballroom also. Botetourt's "Groom of the Chambers," Joseph Kidd, after he had left the governor's service and had set up for himself in Williamsburg, charged his former employer 10s. "for Pressing and Nailing down a large Carpet for the Ball Room" in November 1769.[12]

Fenton's lengthy itemization of goods on August 12, 1768, includes certain items identified in the Governor's Palace later, although about the first object on the list some doubt remains. The couch bed, for which Fenton supplied mahogany posts and a folding tester, may have been the one that was specified in the inventory in the butler's pantry. It was noted that the couch there had a mattress and bolster, but no curtains were listed. The twelve mahogany chairs covered with hair seating and double brass nailed were very likely ordered for the dining room in Williamsburg, where Botetourt's sociability would have been at its most active, though the governor also bought eighteen hair-bottom chairs for £18 (Virginia currency) from Fauquier's estate, comparable in value to those from Fenton (figs. 6, 7). Botetourt's inventory also included twelve such chairs in the ballroom and twelve in the "Passage up Stairs" –the anteroom to the most formal "Middle Room" on the second floor–in addition to those in the dining room.[13]

The "best Verdeter . . . prusian blew," whiting, leather specks, brushes, and "2 Ream of fine large Elephant paper" were all destined for the ballroom as, probably, were the 20,000 tacks (figs. 1, 8). Certainly the chandeliers and a stove from other London tradesmen as well as the Ramsay portraits were acquired for that handsome space. The “500 foot of Gooder oun Gilt moulding at 9p" for which Fenton charged the governor on October 6 was also part of the above scheme. That these supplies were intended for the grand ballroom is suggested by the quantity of the elephant folio-sized paper (about 1000 sheets) and the amount of border. That it was the ballroom is confirmed by Joseph Kidd's small charges in November 1769 and June 1770 for "Mending Paper in the Ball Room." Since Kidd was groom of the chambers and later advertised (when in business for himself in Williamsburg) that one of his skills was paperhanging, the deduction is that he installed the paper soon after the governor's arrival and did some touch-up repairs to it about a year later. That the furnishing scheme was impressive is attested by the 1771 comment of Cambridge educated, Virginia great planter, Robert Beverley, in a letter to a London merchant: "I observed that Ld B had hung a room with plain blue Paper and border'd it with a narrow stripe of gilt Leather, wch. I thought had a pretty Effect." Thomas Jefferson was also impressed–in 1769 he ordered identical supplies for a room in his new house. Robert Carter of Nomini Hall purchased plain blue paper in 1773. Col. George Washington began to plan the addition of a ballroom to his house in this period, too, which he intended to decorate with a plain colored paper.[14]

Though the cost of the border that Fenton supplied to Botetourt, £18.15.0, was almost as much as the rest of the wallpapering supplies combined, it was still, to judge by the cost per foot noted in Chippendale's accounts, a papier-mache border rather than a carved one. The stiffness of this (requiring it to be shipped and stored in "a long box"), yet its apparent difference from carved and gilded wood, is probably what led Beverley to describe it as gilt leather. It, too, would have required some of the plentiful supply of tacks mentioned above for its installation.[15]

Fenton also charged on October 6 for twelve more chairs "the same as the others"-presumably a reference to the ones invoiced on August 12. Because they were new and smart, it is likely that they were destined for the public, highly social ballroom rather than another space in which the inventory lists hair-bottom chairs, such as the anteroom upstairs - a room of service for petitioners and servants to wait in attendance. In the ballroom the presence of monarchy was proclaimed and groups of prominent colonists were entertained at formal receptions and at dinner. The plain blue wallpaper that Botetourt had installed had been (not coincidentally) the personal choice of George III for his private rooms in Buckingham House in the 1760s. The Williamsburg ballroom bore the further, and powerful, imprint of monarchy with the full-length portraits of the king and his consort, Queen Charlotte. The most important occasion for the room's use throughout the year was the annual ball to celebrate the birthday of the king, which "all English Gentlemen" were expected to "attend and pay their respects." With such overtones, and with the dining function for important groups such as the colony’s legislators (too numerous to accommodate in the dining room) further established in this space, it is highly likely that the smart, double brass-nailed chairs were intended to be part of the ballroom's accoutrements, just as they were of the dining room's.[16]

The following item on Fenton's list for October 6 shows Botetourt's interest in fashion: "12 Bamboo Chears Blew & gold with lutestring quishons," complete with check cases, were exceptionally stylish. Ten years later such items would have been less conspicuous. As it is, only one earlier reference, with the objects surviving to match the document, is known- a set of bamboo chairs supplied in May 1767 by William Linnell to William Drake for Shardeloes, a house for which Robert Adam had provided designs and advice on modernization in 1765. The Linnell chairs were intended for bedchambers and it was in that location that Botetourt placed his set in the Governor's Palace, eight in the larger room and four in the smaller (figs. 4, 9, 10). When they were inventoried in Williamsburg in October 1770, however, they were described as "Green bamboo chairs with check'd Cushions." Confusion between certain shades of the colors blue and green is not unusual today and probably was not then. (An eighteenth-century instance of this occurs in the well-documented furnishings for Harewood House, Yorkshire, made by Thomas Chippendale.) It is unlikely that Botetourt had his smart new chairs repainted in Williamsburg–there is no hint of it in the accounts–though it is, of course, possible. In placing this fashionable order, Botetourt may have been at least partially inspired by his late brother-in-law, who had commissioned extraordinary Chinese-inspired furniture for his sumptuous Chinese bedchamber at Badminton in 1752-1754.[17]

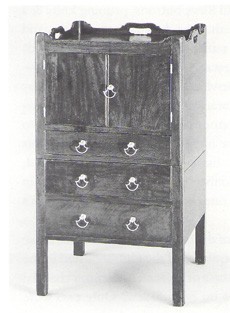

Three "large mohogainy Cloaths presses with slideing shelves & drawers 2 of them lined with Green Bazse" for £45 represented heavy, bulky objects that surely would have been less expensive if purchased in Williamsburg. They were clearly of importance to Botetourt since he also purchased a clothespress for £10 (Virginia currency), a large chest of drawers for £12, and four further chests of drawers (presumably smaller) for £ 12.10.0 from Fauquier's estate. By the time of the governor's death the mahogany clothespresses stood in the two principal bedchambers on the east side of the Palace and in the more formal, ceremonial Middle Room. Botetourt's own bedchamber, however, contained the large walnut and the small chest of drawers, probably acquired from Fauquier, that housed his intimate clothing, whereas the newer presses in the other rooms held his suits and other formal garments. The mahogany basin stands were also intended for bedchambers and were inventoried on the second floor of the Palace (including the Middle Room) as well as in the bedchambers of the senior male servants, Marshman and Blandford (figs. 11, 12). Only three of Fenton's six dressing glasses seem to have been taken to Williamsburg; even then it appears that the item in the governor's bedchamber listed as "1 Wash bason & Mahog. stand compleat with a dressing glass" was a single piece of furniture, whereas the others were described as a "small lookg Glass Mahog. frame," and "1 Swing Looking Glass" (in the coachman's room).[18]

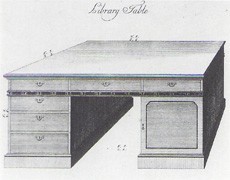

Fenton's next entry for furniture and supplies was dated April 15,1769. The original bill was endorsed (probably by Thomas Conway, the fifth duke's auditor on whom Botetourt relied for supervision of his accounts while he was abroad) "Goods for Virginia." The most expensive item in the bill became the centerpiece of the governor's workspace (fig. 13): "a large & very neat mohogainy lybery table of very fine wood Covered with leather the moulding Richly Carved on 8 3 wheel Castors." At a cost of £24 it was equivalent to a year's wages for a household servant. Clearly a piece of considerable presence, it was destined for the dining room, a large, handsome room that also served as the governor's office. It was inventoried in October 1770 as "1 mahogy library table containg papers public & private," a terse description that gives little insight to its inherent qualities and richness. It did not take kindly to the Virginia climate, for in June 1770 it was necessary to bring in a tradesman who charged 2s. 6d. for "Easeing Drawers and fixing on Moulding To My Lord's Library Table."

A further insight into Botetourt's perceptions of his furniture and the local trade is that, although it appears he had already patronized a Williamsburg artisan (the petty cash disbursements, for February 22, 1769, include "To the Cabinet Maker's bill . . . £ 3.0.2.3") he delegated the repair of his new and elegant library table to the former carpenter in his retinue, Joshua Kendall. This man could just as readily supply a grease box to the coachman, cut a tub for the gardener, or mend a sifter for the cook (all of which he did the same month). Either the governor had a high regard for his skills or he did not believe that the repair was otherwise likely to jeopardize his expensive new table.[19]

In the same order Fenton also supplied two "3 foot 6 Inch desks & one 3 foot." Perhaps one of these accompanied the library table in the dining room. In this space the inventory listed "1 mahogy Desk, containg sundry papers private & public, one embroidd pocket book a miniature drawing, 1 Diamd mourng ring & a pair of Gold Sleve buttons, pruning knife & a steel pencil." It is, however, possible that the desk Botetourt kept, and clearly used, in his dining room was rather the one (wood unspecified) that he had acquired from Fauquier's estate–"1 boreau and book case"–for £8. In the latter's inventory (somewhat jumbled and not divided by room) this piece was listed near the library table that Botetourt also purchased from the estate for £6. Yet Botetourt relegated this library table to the butler's pantry and for his own use imported something more to his taste. Only four other desks were listed in the entire compound, mahogany ones in the guest bedchamber on the second floor and in Blandford's garret room, and walnut ones in the cook's and coachman's bedchambers.[20]

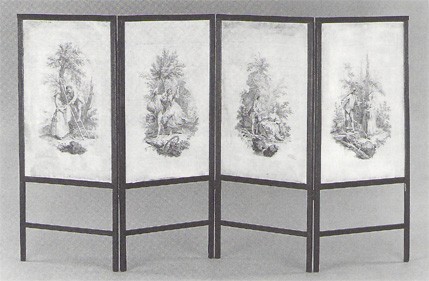

The disparity between the number of desks Fenton supplied plus those that Botetourt bought used from Fauquier, and the number listed in the Botetourt inventory is repeated in the case of firescreens. Fenton charged £3.10.0 for "3 fire Screens with maps on both Sides." Only two were inventoried in October 1770, a mahogany one in the dining room and "1 claw fire screen" in Silas Blandford's bedchamber. Significantly, the only surviving piece of furniture in Virginia with a Botetourt history is a firescreen–not a claw type, but rather a folding kind, with three panels (fig. 14). In each panel is a stretcher on which is mounted an eighteenth-century print (the reverse side of each panel consists of plain paper). The stretchers are yellow pine and were probably early replacements. This screen would seem to match the Fenton reference quite closely, although where the others he supplied ended up is a mystery.[21]

The final piece of furniture that Fenton listed in his account was "a mohogainy Cellor lind with lead" at a cost of 4 guineas. This was presumably the "mahogy wine cooler" later inventoried in the dining room, the only such item in the entire inventory, yet the butler's accounts of the petty cash disbursements in Williamsburg include a charge for a "large wine cooler" on May 5, 1770, for a cost of only 10s. Another one for an identical sum was entered on June 29. The following September a payment of 1s. 3d. was recorded "to the cooper for mending a wine cooler," which makes it unlikely that these two locally acquired items were the "2 japann'd wine Cisterns" listed in the pantry when the inventory was taken. By the summer of 1770 a local cabinetmaker's name had appeared twice in the petty cash accounts - "To Mr. Bucktrout's bill" on November 1, 1769, and an identical reference on June 26, 1770, for £2.11.3. There is no evidence what these charges were for.[22]

On April 29, Fenton charged Botetourt for another 500 feet of gilt molding, an amount identical to that he had supplied in October 1768. It was not that 500 feet was insufficient for the ballroom. Rather, the governor had probably decided to refurbish the other main assembly room in the residence, the supper room. For reasons that are unclear today, this was never done. The "osnabrigs" (linen to paste on the plaster walls), the "common brown Paper" (to paste on the linen, probably to cover the seams and make a stronger layer), and about 175 sheets of the white or "cartridge" paper were still in storage in October 1770. According to the inventory takers, the osnabrigs were "intended to paste the Paper on in the Supper Room." Some pigment and a long box of gilt bordering also "intended for the Supper Room" were also recorded in storage.[23]

Smaller items that might be categorized by the word "sundries" among Fenton's accounts were just as important to the functioning of the house hold and to Botetourt's performance of his duties as many of the pieces listed above. Quilts and blankets, tammy for curtains, green baize and green sarsnet, large quantities of brass nails for upholstery, mahogany basin stands (bottle sliders or coasters), turned wooden trays for various aspects of the dinner ceremony, half cases for chairs (that is, covers for the seats only), inkstands with cut glasses (ubiquitous in the inventory), the iron chest or strong box for cash, thread, lead, oil, turpentine, almost 50,000 nails and tacks of different kinds, curtain line and rings, cloak pins, pulleys for curtains on windows and beds, a venetian blind-virtually all of these items the governor could have obtained in Williamsburg. That he did patronize one of the leading cabinetmakers locally, Benjamin Bucktrout, is shown by the petty cash disbursements-slightly more than £22 worth of goods between November 1769 and 1770. A vague tradition has it that Botetourt was also involved in what must have been Bucktrout's most demanding commission, the great masonic master's chair for an unidentified Virginia Lodge, the only known piece of furniture marked or labeled by this immigrant tradesman. If Botetourt ever saw this tour de force of the furnituremaker's art he would not have doubted Bucktrout's level of ability. Yet when Botetourt's executors and staff were hastily gathering supplies in the four days between the governor's death on October 15, 1770, and the funeral on October 19, they rejected japanned handles for the coffin that Bucktrout sent in favor of silver ones supplied by local silversmith and engraver William Waddill.[24]

Among the questions implicit in this study, one of the most challenging and tantalizing is that of perceived differences in quality between what was available in London from a tradesman who has no other claim in history than certain apparently routine work for a minor aristocrat (plus a small amount for the duke of Beaufort), and what was available in a colonial capital. Botetourt's preferences cannot simply be explained away by the fact that he was coming from England and that it was more expedient to use known, reliable sources. He was a thoughtful and most considerate man and surely realized that he would earn, by extensive local patronage, much goodwill that would be helpful in a period of unusual tension between the colonies and the mother country. Indeed, after his death there was a resounding endorsement from each social group in the colony-servant, merchant, great planter- of his extraordinary qualities, his empathy for his colonial compatriots, his sensitivity, his considerateness. That he did patronize certain local tradesmen is established by his petty cash disbursements. Yet payments to cabinetmakers are few and the amounts inconsiderable. It is undeniable that he thought it important to make, through his furnishings in the principal chambers of the residence, a statement of his own status. What is clear is that other men of affluence in the colony, whose accounts have survived in sufficient detail, followed similar patterns and had the same kinds of perceptions. For finer quality, they bought abroad. How true was this for the residents of the other colonies?

| Appendix Botetourt Account, Including Charges with William Fenton, Cabinetmaker Botetourt Mss from Badminton (M-1395) D 2700 I Shelf No. 15 ffr: 274-289 Account book including carriage and Fenton 1786 Sept. 30-1769 July |

|||

| 1768 | |||

| Sepr 30 | Mr Catton | ||

| To painting & gilding A State Coach The painells gilt with pale gold and painted with the Arms Supporter and mottos of the province of Virginia all within a rich Border of Ornamt. The framing gilt The Carriage and Wheels gilt. |

73 |

|

|

|

Card Over. . . . . . . .

|

73. - . -

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Brot Over . . . . . . . .

|

73. - . -

|

||

| Mr Butler | |||

| For a Second hand State Berlin that was the Late Duke of Cumberlands |

35 |

|

|

|

|

|||

| For taking out the fore Glass Unhanging the Body washing Cleaning scraping & smoothing up the Joynts of the Body & Carriage repairing the Carv'd work of Do for Painting & for Additional Carv'd Work to the Carriage |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|||

| For a new Sett of very Handsome turn'd spoke Wheels & Iron work with Beaded felloes Clouting the Axletrees fitting on the Wheels & 4 nees Linspins |

12 |

|

|

|

Carried forward . .

|

52 |

73

|

|

|

Mr Butler brot forward . . . . .

|

52 | 73. - . | |

| For Cutting the fore Standards Shorter fitting & letting in the seat Irons & straining on the Cradle a Coach Box Seat Covered with Canvas 2 new seat straps & tying it on a pair of Pole peices almost Equal to New a new pole Bolt a Brass buckle Chape & flap to the futchells a brass buckle & Chape to the pole hook & a new peice 4 new large Wrought Brass buckles to the Check braces & sewing them in |

2. 14. - | ||

|

Carried over

|

45. 14. - | 73. - . - | |

|

Butler brought over

|

|||

| For Drawing the Brass within side & without & taking out the greatest part of the Lining & for 6 yards of very good Additional Velvet & 20 yards of very good silk lace & 7 yards of very Good silk fringe to the Doors, Elbows, fore End & falls of the seats putting in the lining & garnishing it with new large Gold Varnished brass Nails |

10. 10 | ||

| For Covering the Roof Back & four sides with neats leather | 6. | ||

| For Black Japaning the main & Check Braces | 2. 10 | ||

| For a new very handsome carv'd Ornament all Bound the Roof & a Bead under it & fitting them on. |

8. 8. | ||

| 82. 2. - | 73. | ||

|

Butler brought forward

|

82. 2. - | 73. - . - | |

| For 8 very large Wrought Brak tops (in Exchange for the Old One & Garnishing round the Vallene with 2 Rows of new large gold Varnish'd brass Nails taking of the locks of the Doors repair them & new making them up covering the steps with new neats leather japaning) & Garnishing them with 1000 new large Gold Varnishd Brass nails Covering the tops of the Door Frames with Crimson Velvet & fixing in the fore Glass |

8. 10. - | ||

| Fro a new Carpet to the bottom bound & putting it in with brass pins |

- . 10. - | ||

|

Carried over . . .

|

91. 2. - | 73. - . - | |

|

Butler brought over

|

91. 2. - | 73 | |

| For a handsome Sett of flatt worsted footmans Holders and tassells & Sewing them on with 4 new Chapes |

1. - . - | ||

| For 6 yards of new Crimson flowerd Velvet for a Seat cover For Cutting Out & making up the Seat Cover ining it with peu shalloon bound with silk lace & one Row of Handome Silk fringe with a Gimp head & Button Hangers round the falls & up the Corner |

25. - . - | ||

| For a very Handsome pair of town Harness & Bridles all the brass Work new made up & Gold Varnished new flat worsted Crimson Reins & new handsome Worsted Toppings to the Bridles & a new pair of Bitts with Wrought brass bossess |

15. - . - | ||

| 132. 2. - | 73. - . - | ||

|

Butler brought Forward

|

132. 2. - | 73. - . - | |

| For a new Bayes Cover & shings to Cover the Body & packing up the Body with tow & Canvas squabs to prevent the Case from rubbing it |

3. - . - | ||

| For Casing up the fore Glass & for a remarkable strong Deal Case with a Number of Iron Clouts to strengthen it & packing up the Body |

6. - . - | ||

| For packing up the Carriage & Wheels carefully in paper and Matts & sewing them up in Canvas Cartage Wharfage Attendance Expences & getting on board |

6. 15. - | ||

| Butlers Bill Total | 147. 17 | ||

|

Card Over . . . . . . . .

|

220. 17. - | ||

| 1768 |

Brot Over . . . . .

|

220. 17. - | |

| May 7th | Willm Fenton | ||

| For Iulire [entire] new Stuffing the Seat of a Sette mending the frame one new Castor |

- . 12. - | ||

| For a new hinge to a reading desk | - . - . 6 | ||

| For 3 Large print frames & glasses & packing Case | 1. 10. - | ||

| For 6 Crimson Check Cases to 6 Stuffed back & Seat Chears |

1. 13. - | ||

| For 9 brass hooks & Several Jobs done | - . 3. - | ||

| For new green Tammey to 2 Spring Curtons and mending them |

1. 5 | ||

| 20 | For a bed side Carpet 2 yaards & 1/4 long | - . 11. 6 | |

| For 2 11/4 linning quilts | 4. 4. - | ||

| For 2 10/4 ditto | 3. 16. - | ||

| Janry 17 | For Cleaning 24 Blankets | 1. 18. - | |

| July 11 | For 2 fine 10/4 Caleco quilts | 6. 6. - | |

| August 7 | For a large feild bedstead on | 21. 19 | |

| castors with Crimson Check | 220. 17. - | ||

|

Totals

|

|||

|

Fenton brought forward

|

21. 19 | 220. 17 | |

| furniture made up with lace proper 2 large thick matterases bolster & 2 pillows apair of 10/4 blankets one 8/4 ditto a 10/4 quilt linning Back all very good |

£15. 10. - | ||

| 3 beds the Same | 14. 10. - | ||

| 3 Ditto but without pillows & the quilts Stuff backs | 44. 10. - | ||

| For 234 yards of wilton carpet at S5 p yds | 58. 10. - | ||

| For 52 & 1/2 yards of green Bazse yard wide at 19d p yds |

4. 3. 1 1/2 | ||

| For a large packing case | 1. - . - | ||

| For 18 matts & Cord | 1. 8. | ||

| Expences putting the goods on board | - . 12. - | ||

| 12 |

For 4 mohogainy posts to a Couch bed plates & scrws & a mohogainy folding teaster |

1. 10. - | |

| For 19 yards of green sarsnet at 3S6d p yd | 3. 3. 6 | ||

| 183. 5.7 1/2 | 220. 17. - | ||

|

Totals

|

|||

|

Fenton brought over

|

183. 5.7 1/2 | 220. 17. - | |

| For 10 yards of Tammey | - . 15. - | ||

| a Counter payne bolster Case & Cover to the bead board of bed |

- . 18. - | ||

| For 12 mohogainy Chears Covered with hair Seating and Double Brass nailed at £1.5 p |

15. - . - | ||

| For 50 lb of the best Verdeter at 6s p | 15. - . - | ||

| For 24 lb of prusian blew at 10d p lb | 1. - . - | ||

| For 6 Brushes 30lb of leather Speck 4 doz of Whiteing 2 firkins & c. |

- . 15. - | ||

| For 2 Ream of fine large Elephant paper | 2. 10. - | ||

| For 4 peices of boot tape 2 lb of Carpet thrid | - . 15. - | ||

| For 10m tacks 10m white tacks | 1. 1. 6 | ||

| For 16 Doz of brass headed Stoco nails of Differant Sorts |

1. 8. - | ||

| For 8 Doz of brass hooks | - . 9. - | ||

| 222. 17. 1 1/2 | 220. 17 | ||

|

Totals

|

|||

|

Fenton brought forward

|

222. 17. 1 1/2 | 220. 17 | |

| For 2000 brass nails 64 yards Crimson lace | 1. 6. 6 | ||

| For 8 matts & packing goods at my lords house | - . 16. - | ||

| For a neat traveling box with Scrws & key to dite | 1. 15. - | ||

| October 6 | For 500 foot of Gooder oun Gilt moulding at 9p | 18. 15. - | |

| For 12 mohogainy Chears the same asthe others | 15. - . - | ||

| For 12 Bamboo Chears Blew & gold with lutestring quishons at 1lb .18s p |

22. 16. - | ||

| For Check Cases to Ditto | 1. 10. - | ||

| For 3 large mohogainy Cloaths presses with sliding shelves & drawers 2 of them lined with Green Bazse |

45. - . - | ||

| For 6 mohogainy Bason Standa | 4. 16. - | ||

| For 4 Dinner trays 2 butter trayes | 4. - . - | ||

| for 4 knife trays | 1. 10. - | ||

| 340. 1.7 1/2 | 220. 17. - | ||

|

Totals

|

|||

|

Fenton brought over

|

340. 1.7 1/2 | 220. 17. - | |

| For 6 Dressing glasses | 2. 7. - | ||

| For 6 large Inkstands with Cut glasses | 4. 4. - | ||

| For 12 bottle boards & 6 waiter | 1. 10. - | ||

| For 18 matts & Cord | 1. 5. - | ||

| For 590 foot in 8 large packing Cases at 3d p | 7. 7. 6 | ||

| For 6 half Cases for 12 Chears | 2. 8. - | ||

| For Cart load of goods from my lords house & 2 from my house |

- . 17. - | ||

| For Warfage & 2 large boats to take the goods to the ship |

1. 6. - | ||

|

Fentons First Bills Total

|

361. 6.1 1/2 | ||

|

Card Over

|

582. 3.1 1/2 | ||

|

Brot over

|

582. 3.1 1/2

|

||

| 1769 | Coggs & Crump | ||

| Feb. 28 | To 60 Wax Candles | 8. 10. - | |

| Box & Cord | - . 2. 6 | ||

| 8. 12. 6 | |||

| 1769 | Late Basnetts | ||

| Feb. 14 | 6 Broad richsilver Livery hat Laces . . . at 13/7 | 4. 1. 6 | |

| 6 Buttons & Chain Loops at 15d | - . 7. 6 | ||

| 4. 9. - | |||

| Charles Vere | |||

| a Compleate Sett of Fine nankeen Tea China | 5. 5. - | ||

| 6 Fine mamkeen 1/2 Pint Basons & Plates | 1. 7. - | ||

|

Box

|

- . 1. 6 | ||

| 6. 13. 6 | |||

| Charles Coles | |||

| 1 Rm ff Cap broad | 1. - . - | ||

| 4 qrs best Demy | - . 8. - | ||

| 2 qrs Roy1 | - . 6. - | ||

| 1. 14. - | |||

| 582. 3.1 1/2 | |||

|

Brot Over

|

582. 3.1 1/2 | ||

| John Steerces | |||

| 3 Scollop'd Shell Tureen Ladles at 12/- | 1. 16. - | ||

|

Box

|

- . - . 6 | ||

| 1. 16. 6 | |||

| Coggs Wax Chandler | 8. 12. 6 | ||

| Vere for China | 6. 13. 6 | ||

| Barrel for Lace | 4. 9. - | ||

| Cole Stationer | 1. 14. - | ||

| Steers for Soup Ladles | 1. 16. 6 | ||

| Two Red Tea pots | . 2. 4 | ||

| 23. 7. 10 | |||

|

Total paid Mr Capper

|

25. 7. 10 | ||

|

Card Over

|

607. 10.11 1/2 | ||

| 1769 | William Fenton | 607. 10.11 1/2 | |

| Apr 15 | For 2 3 foot 6 Inch desks & one 3 foot | 21. - . - | |

| For a large & very neat mohogainy lybery table of very fine wood Covered with leather the moulding Richly Carved on 8 3 wheel Castors |

24. - . - | ||

| For a small Iron Chest to be put in one of the Cuberts of the table |

3. 8. - | ||

| For a mohogainy Cellor lind with lead | 4. 4. - | ||

| For 3 fire screens with maps on both sides | 3. 10. - | ||

| For large packing Cases & matts | 2. 2. - | ||

| For Expences putting on board | - . 12. - | ||

|

Fentons Bill Total

|

58. 16 | ||

|

Card Over

|

666. 6.11 1/2 | ||

|

brot Over

|

666. 6.11 1/2 | ||

| 1769 | William Fenton | ||

| March 4 | For 2 peices of Blew moreen For 2 pair of 12/4 Blankets For a 13/4 Caleco quilt |

5. 5. 5. 18. 5. 12 |

|

| For 35 1/2 yards of blew Bazse at 17d p yd | 2. 10 3 1/2 | ||

| For 10 peices of Broad quality at 2s6d p P | 1. 5. | ||

| For 6 peices of narrow Ditto | - . 9. | ||

| For 4 pound of Coulered & white thrid | - . 16. - | ||

| Fro 3/4 of a pound Differant Coulered Silk | 1. 10. - | ||

| For 2 Hundred of white lead | 3. 18 | ||

| For 7 Gallons of linseed oyle | 1. 4. | ||

| One Gallon of turpintine | - . 3. 6 | ||

| For 2 Casks & a bottle | - . 8. - | ||

| For 4000 Brass nails | 2. - . - | ||

| For 10 thousand tacks | - . 11. - | ||

| For 10 thousand white tacks | - . 12. - | ||

|

Card forward

|

32. 1.9 1/2 | 666. 6.11 1/2 | |

|

Fenton brought forward

|

32. 1.9 1/2 | 666. 6.11 1/2 | |

| For 8 grose of Brass owes | - . 16. - | ||

| For a grose of Curton rings | - . 5. - | ||

| For a grose of polished Do | - . 9. - | ||

| For 8 grose of Studs | - . 5. 6 | ||

| For 2 Doz. of Cloakpins | - . 8. - | ||

| For 6 Doz of Brass Scrue hooks | - . 6. - | ||

| For one grose of 2 Inch Scrues | - . 5. 6 | ||

| For one grose of Curton line | 1. 19. - | ||

| For 12 tossels | - . 13. - | ||

| For 3 peices of breed | - . 7. 6 | ||

| For 36 yards of Strong worsted line | 2. 5. - | ||

| For 36 yards of Silk ditto | 4. 1. - | ||

| For 2 grose of pullys | - . 13. - | ||

| For half a grose of long pullys | - . 4. - | ||

| For a Venetian Blind | 1. 9. - | ||

| For a large packing Case & a small Do | - . 15. - | ||

| Paid the freight & Expences putting on board | 2. 5. - | ||

|

Fentons Bill Total

|

49. 8. 3 1/2 | ||

|

Card Over

|

715. 15.3 | ||

|

Brot Over

|

715. 15.3 | ||

| Robt Woodifield | |||

| 20 Doz Burgundy Botts Corks & cement | 60. - . - | ||

| 2 seven & 1 six dozen Chests & packing | 1. 6. - | ||

| Paid Wine Porters putting up the Chests | - . 3. - | ||

| Cart to the Key 5 J. Wharfage & Porters 3 | - . 8. - | ||

| Boat hire to the ship | - . 3. - | ||

| Custom house Fees | - . 17. 6 | ||

| Debenture & Receiver | 1. 2. 1 1/2 | ||

| 63. 19. 7 1/2 | |||

|

deduct for Draw back

|

5. 2. 1 1/2 | 58. 16. 6 | |

|

Sanxay & Bradley

|

|||

| A Chest Hyson Tea Shipd on board the Experiment Captain Hamtin, For Virginia No2379. . . qz66lb@12p |

39. 12. - | ||

| 12 Six pound Cannisters @ 2/6 | 1. 10. - | ||

| Two Chests, and Charges on board | - . 3. - | ||

| 41. 5. - | 41. 5. | ||

| 815. 16. 9 | |||

|

Brot forward

|

815. 16. 9 | ||

|

Hannah Jones

|

|||

| 140 white wax Lights at 2/- | 14. - . - | ||

| Box | - . 4. - | ||

| 100 wallnits | - . 8. - | ||

| 2 Jarrs | - . 2. - | ||

| 1 Basket | - . - . 6 | ||

| Charges | 1. - . - | ||

| 15. 14. 6 | 15. 14. 6 | ||

| 1769 | |||

| Ap1 29 | Wm Fenton | ||

| For 500 feet of Goodroon Gilt Moulding at 9d | 18. 15. 0 | ||

| To 12 Ounces of Brass Nails | - . 6. - | ||

| To Packing Case | - . 10. - | ||

| 19. 11. - | |||

| Ap1 | Wm Sparrow (Cook) | ||

| For Bedding for the Voyage | 2. - . - | ||

| For Glass & Box | . 13. - | ||

| 2.13. - | |||

|

Card Over

|

853. 15. 3 | ||

| 1769 |

Brot Over

|

853. 15. 3 | |

| April | John Sewell | ||

| For Robertson His Chas5 & Box | 3. 1 | ||

| May | Phillip Hall | ||

| 2 Jars of Raisons a 58s p lb | 1. 9. 6 | ||

| 2 [?] 0.7lb Currants a 54s | 5. 11. 4 | ||

| Barl2s Cart 18d Shiping Charges 5.8 | 9. 2 | ||

| 7. 10. | |||

| John Shearwood | |||

| For 2 Hatts | 2. 2. 0 | ||

| Box | . 1. - | ||

| 2. 3. | |||

| Mr Crofts | |||

| For minuts of H. Lords in Session begining 10 May 1768 |

1. 1. - | ||

| For Do begining 8 Nov. 1768 End 9 May 1769 | 5. 5. 0 | ||

| 6. 6. | |||

|

Card forward

|

872. 15. 3 | ||

| 1769 |

Brot forward

|

872. 15. 3 | |

| June | John Newman | ||

| For 3 [?] Nutmegs | 1. 7. 0 | ||

| Black Pepper 8lb | . 14. 8 | ||

| White Do 2 | . 8. | ||

| Alspice 2 | . 2. | ||

| Jordan Almonds 6 | . 8. | ||

| Bitter Do 1 | . 1. | ||

| Mace 1/4 | . 5. | ||

| Cloves 1/2 | . 6. | ||

| Bitter Alm: Powder 6 | . 6. | ||

| Box & Sufferage | . 3. 8 | ||

| 4. 1. 4 | |||

| Sarah Lauder | |||

| To half a Hund. Powder | 1. 3. 9 | ||

| 500 Toothpicks | . 1. 6 | ||

| 1. 5. 3 | |||

| 878. 1. 10 | |||

| 1769 |

Brot Over

|

878. 1. 10 | |

| June | Gataker & Co | ||

| 4 Bottles of Arquebusade | 1. - . - | ||

| Qt of Oppadeldock | . 16. - | ||

| 2lb Venice Soap | . 3. | ||

| 2 Rochell Salts | . 16. - | ||

| 8 Oz Ipocacuana | . 8. | ||

| 2lb purging Salts | . 2. 8 | ||

| Packing Case &c. | . 8. 4 | ||

| Tow to pack the things with | . 3. | ||

| Portorage | . 1. - | ||

| Broabers Introduction to Physick &c. | . 14. | ||

| Toothdrawing Instraments | . 9. | ||

| 5. 1. | |||

|

Card forward

|

883. 2. 10 | ||

| 1769 |

Brot forward

|

883. 2. 10 | |

| July | Robt Douglas | ||

| Livery Button 12 Doz Coat 12 Dz britches | 1.7.0 | ||

| Making Coat & Waiscoat | . 13. 6 | ||

| 4 yds Blue Cloth | 4. - . - | ||

| 5 yds rattanet | . 14. | ||

| Coat sleves lining Coat & Waiscoat pockets | . 3. - | ||

| Treble Dimaty for body Linings | . 9. | ||

| Velvet for a Coller | . 1. 6 | ||

| 22 Coat & Britches buttons | . 7. 4 | ||

| Sewing Silk & Twist | . 3. 6 | ||

| Buckram Canvas & Stays | . 3. - | ||

| Box & Cord | . 2. - | ||

| To making a full trimed Suit | 1. 4. - | ||

| 4 [?] Black Cloth | 4. 10. 3 | ||

| 6 1/2 Ratanet | . 18. 5 | ||

| Coat Sleve lining & Coat & Waiscoat pockets | . 3. - | ||

| Treble Dimaty for Lining Body &c. | . 9. | ||

| Britches lining & pockets | . 5. - | ||

| Buckram &c. | . 4. | ||

| Card Over | 15. 17. 8 | 883. 2. 10 | |

| 1769 | |||

| June | Robt Douglas & brot Over | 15. 17. 8 | 883. 2. 10 |

| Sewing Silk, Twist & 88 Buttons | . 12. 6 | ||

| To making a Roqueleau | 1 10. 6 | ||

| 4 1/4 yds Scarlet Cloth | 4. 9. 3 | ||

| Trimming Buttons & Neckloop | . 5. 6 | ||

| Making Coat & Waiscoat | . 13. 6 | ||

| 4 yd black Cloth | 3. 16. - | ||

| 6 1/2 Ratanet | . 18. 5 | ||

| Coat Sleve lining Coat & Waiscot Pockets | . 3. | ||

| Dimaty for Body Lining | . 9. | ||

| Buttons | . 3. 4. | ||

| Silk & Twist | . 3. 6 | ||

| Buckram &c | . 3. | ||

| Box & Cord | . 4. | ||

|

|

28. 9. 2 | ||

|

Card forward

|

911. 12. - | ||

| 1769 |

Brot Over

|

911. 12. - | |

| July | Messrs Sanxey & Co | ||

| 60lb best Turkey Coffee @ 3s | 9. - . | ||

| Box | . 4. 8 | ||

| 12lb Chocolate 5/6 | 3. 6. - | ||

| 6 Isinglass 7 | 2. 2. - | ||

| 20 Hartshorn Shavings 20d | 1. 13. 4 | ||

| 12 Fr Lentals | . 12. - | ||

| 6 Italian Do | . 6. | ||

| a Chest | . 1. 6 | ||

| 17. 5. 6 | |||

| 928. 17. 6 | |||

| Transcribed by Jan K. Gilliam 8/26/91 |

|||

Botetourt's background is given in some detail in Bryan Little, "Norborne Berkeley, Gloucestershire Magnate;" Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 63, no. 4 (October 1955) : 379-409.

List of items sold from Fauquier's estate, York County Records, pp. 83-99, and Hood, Governor's Palace, app. 1. In 1766 Chippendale charged Sir Rowland Winn at Nostell Priory the identical sum of £1.5.0 apiece for " Mahog parlour chairs coud w. horse hair and double brass nailed" (Gilbert, Chippendale, 1: 183).

Joseph Kidd's charges are recorded in the Robert Carter Nicholas papers. Hood, Governor's Palace, pp.183-88, 244. Robert Beverley to Samuel Athawes, April 15,1771, Robert Beverley Letterbook, 1761-1775, Library of Congress. The papers purchased by Jefferson, Carter, and Washington are discussed in Hood, Governor's Palace, pp. 187-88.

Gilbert, Chippendale, 1:185,189, 207, 229, 231. In 1767 for Mersham-Le-Hatch Chippendale charged for "Papie Mashie Border Painted blue and white" at £0.0.6 per foot. Gilt border would have been a little more expensive. The least expensive carved, gilt border was 1s. per foot. The most expensive was £0.5.3.

Chippendale charged L9.9.0 and.£12.0.0 for clothespresses in 1766 and 1767 and £ 1.0.0 for basin stands (Gilbert, Chippendale, 1: 184).