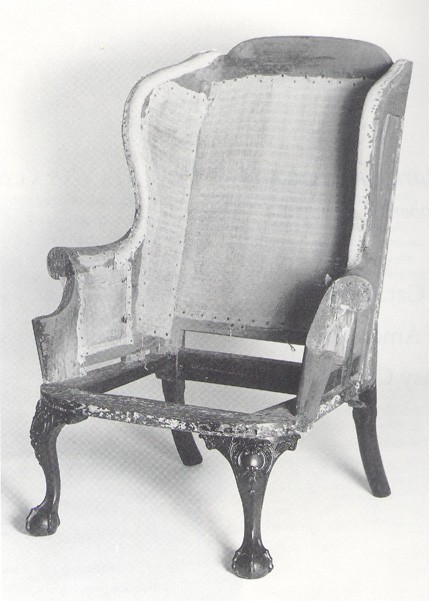

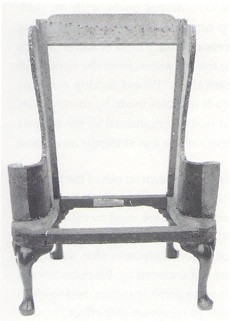

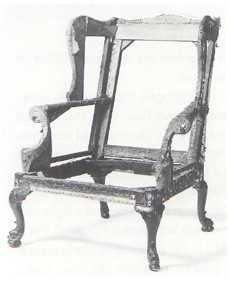

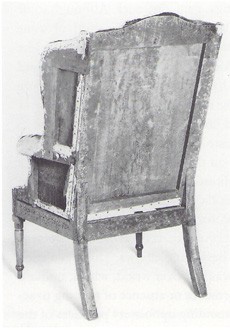

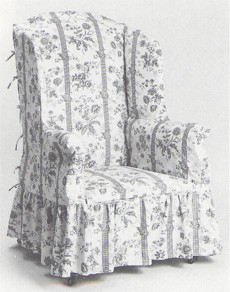

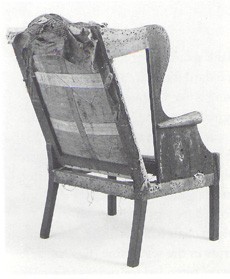

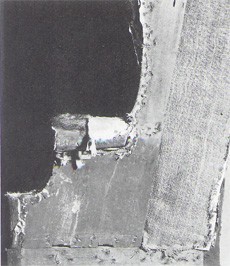

Easy chair illustrated in fig. 1 with the original curled horsehair stuffing removed to expose the sackcloth and edge rolls. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

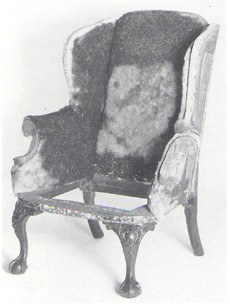

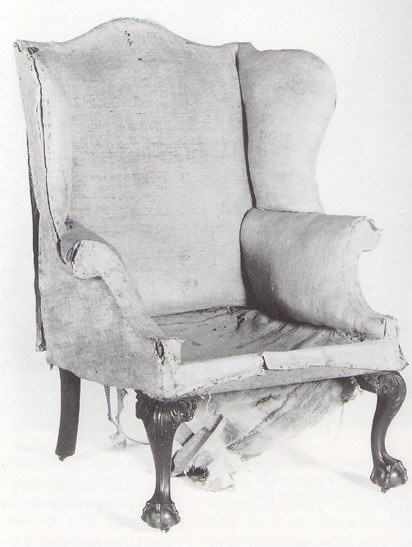

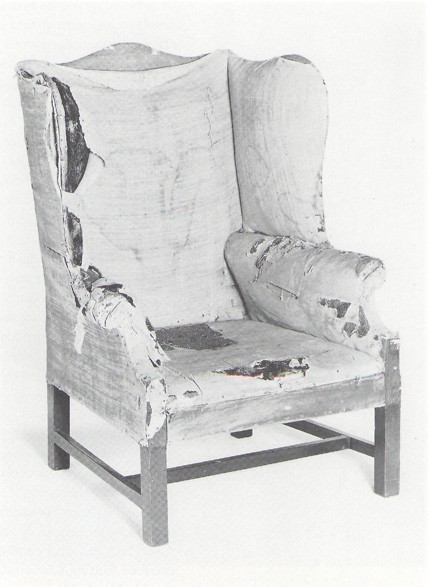

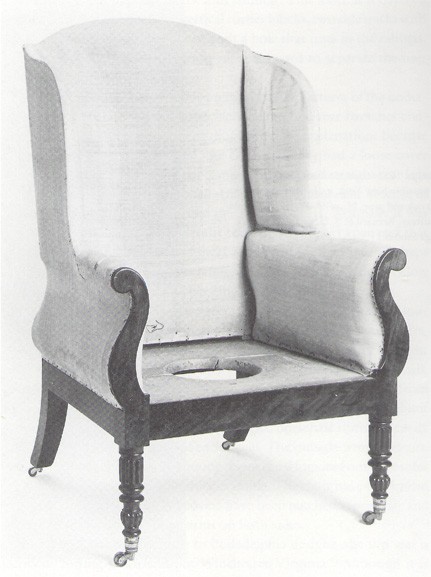

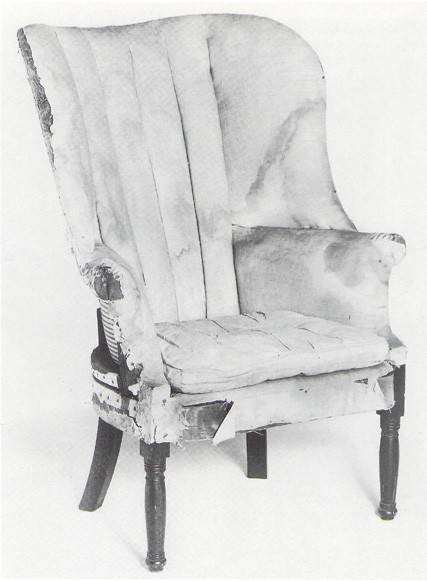

Easy chair illustrated in fig. 1 with the original stuffing in place. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

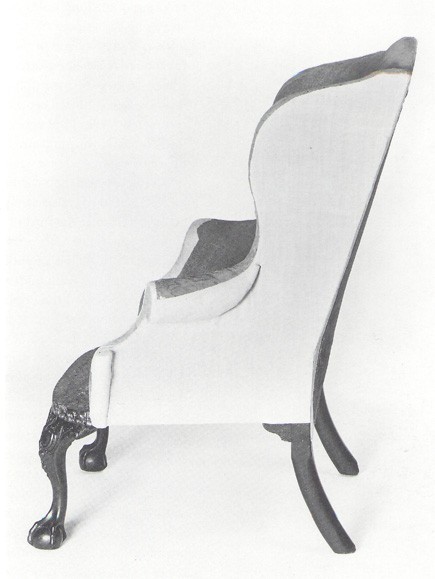

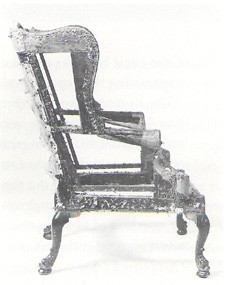

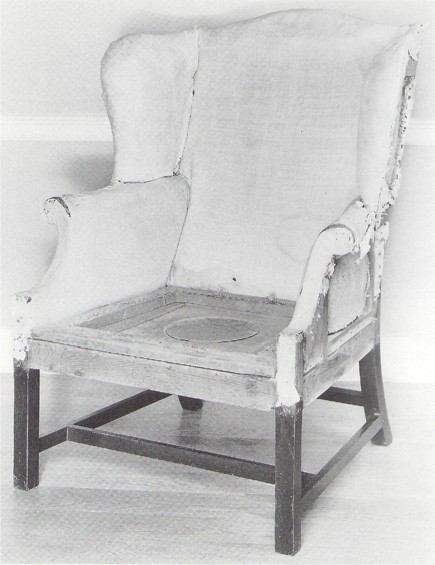

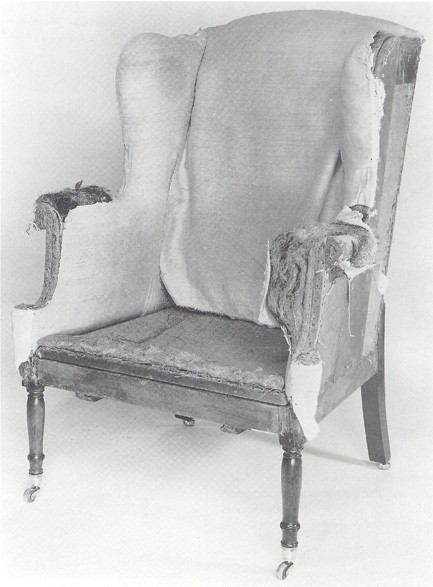

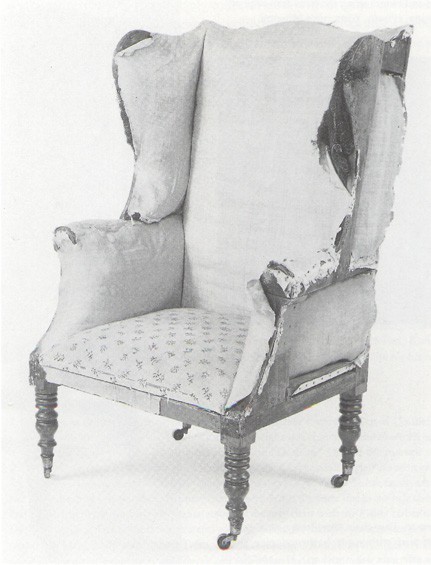

Side view of fig. 1 after conservation and addition of the missing outside covers. Note the line of the seam running down the wing and along the upper arm scroll. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

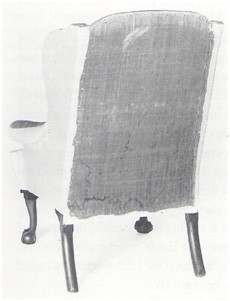

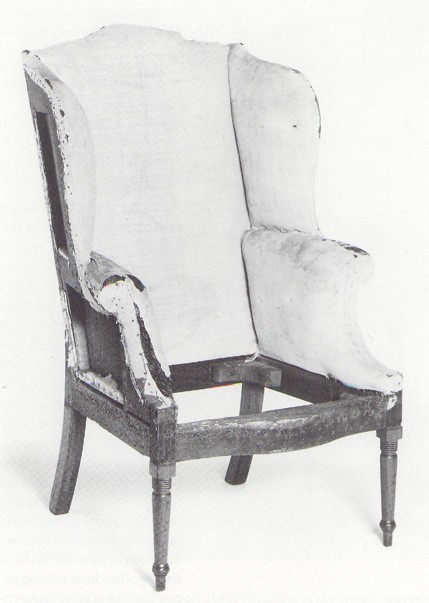

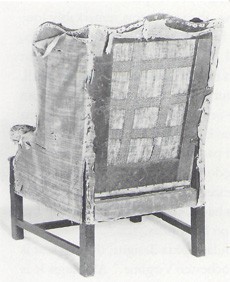

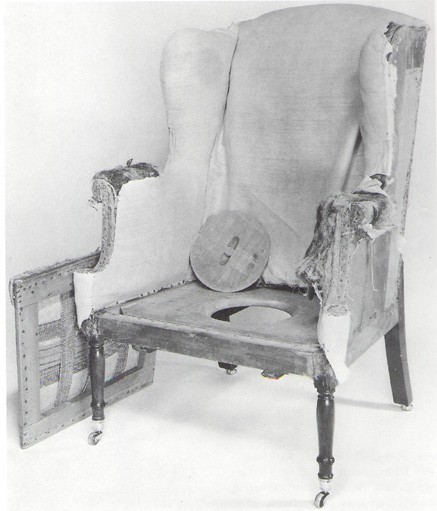

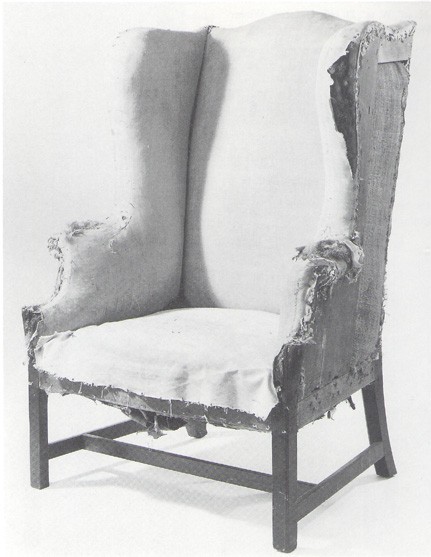

Rear view of fig. 1 after conservation and lining of the original outer back. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, England or Ireland, 1730-1760. Walnut with oak. H. 46", W. 36", D. 27 11 (at seat). (Private collection; photo, John Bly.)

Side view of fig. 6. (Private collection; photo, John Bly.)

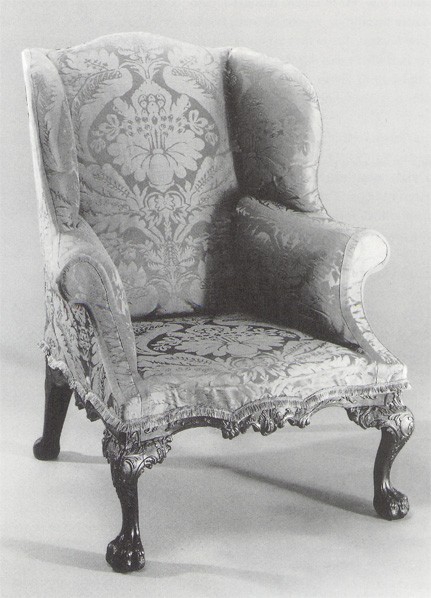

Easy chair made by Thomas Affleck with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, 1770. Mahogany with white oak, yellow pine, and tulip popllar. H. 45", W 36 1/2", D. 34". (H. Richard Dietrich, Jr., on loan to the Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

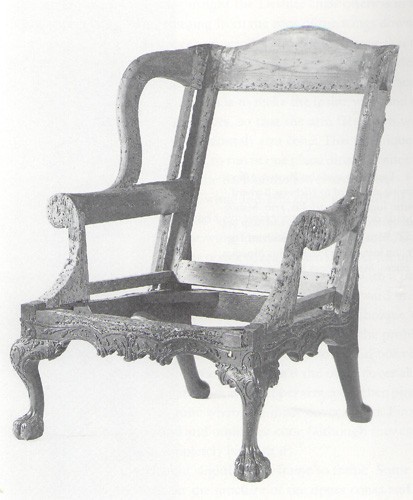

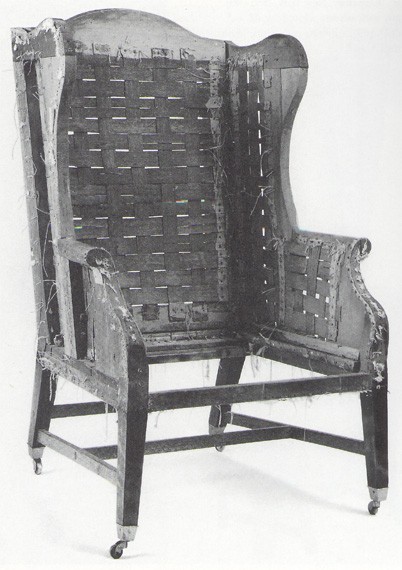

Frame of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

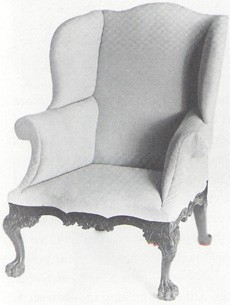

Nonintrusive upholstery foundation fabricated for fig. 8. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Rear view of fig. 8 showing the jog in the upholstery line at the bottom of the outside back. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, England, 1750—1770. Mahogany with Scots pine and ash. H. 41", W. 30", D. 33". (Private collection; photo by owner.)

Side view of fig. 12 showing the arm and scroll construction. (Private collection; photo by owner.)

Easy chair, Philadelphia, 1770—1790. Mahogany with walnut, tulip poplar, red gum, yellow pine, oak, and possibly white pine and maple. H. 46 3/8", W. 36 1/4", D. 29 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 92.31.)

Side view of fig. 14. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, Philadelphia, 1795—1805. Mahogany with tulip poplar and pine. H. 43 3/4", W. 30 3/4", D. 31". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 91.37.)

Rear view of fig. 16. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, eastern Pennsylvania or Winchester, Virginia, 1790—1800. Mahogany with tulip poplar, maple, and white pine. H. 43 5/8", W. 33", D. 30 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 91.44.)

Rear view of fig. 18. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, probably Pennsylvania, but possibly New York, 1795—1805. Mahogany with oak and pine. H. 45 7/8", W. 32 5/8", D. 32 5/8". (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy; photo, Helga Studio.)

Easy chair, New York, New York, 1810—1825. Mahogany with ash and pine. H. 48 1/2", W. 31 1/2", D. 30". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 88.37.)

Front view of fig. 21 showing the original top linen. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Rear view, of fig. 21 showing the outside back top linen. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, New York, New York, 1795—1810. Mahogany with maple, tulip poplar, and pine. H. 46 1/4", W. 31", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy; photo, Helga Studio.)

Easy chair illustrated in fig. 24 with the slip seat and stopper visible. (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy; photo, Helga Studio.)

Easy chair, New York or New Jersey, 1810—1830. Walnut with cherry and maple. H. 45 1/2", W. 33 1/4, D. 38 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Rear view of fig. 26. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Circular easy chair, Philadelphia, 1805—1815. Mahogany with maple, cherry, and pine. H. 46", W. 34", D. 34". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 91.36.)

Rear view of fig. 28. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, eastern Massachusetts or coastal New Hampshire, 1820—1840. Mahogany with maple, cherry, tulip poplar, pine, and ash. H. 49 1/4", W. 33", D. 28". (Private collection; photo, Alexander Studio.)

Rear view of fig. 30. (Photo, Alexander Studio.)

Easy chair, New York, 1800—1825. Mahogany with ash and white pine. H. .49", W. 32 1/2", D. 26 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Rear view of fig. 32. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of fig. 32, showing drilled holes and twines along the outer lead edge of the wing. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, New Jersey, 1820—1840. Curly birch with maple, basswood, pine, and black ash (later oak stretchers). H. 48 1/8", W. 32", D. 29 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

This catalogue illustrates and discusses fifteen easy chairs, with original upholstery foundations or other significant upholstery evidence, most of which are from the mid-Atlantic region. Although we recognize that this is a restricted sample, we believe that these chairs answer questions that are of more than regional or antiquarian interest. We have arranged the chairs in chronological order, but no developmental sequence is implied, except as noted.

An easy chair made for David Deshler of Germantown, Pennsylvania, exemplifies the framing, stuffing, and tailoring of the double-scroll design that was the commonest type produced in Philadelphia from the 1730s to the 1760s (figs. 1-5).[1] No exact English prototypes are known; however, robust English frames with single vertical arm scrolls may have provided some of the profiles (figs. 6, 7). For example, English chairs frequently have a strong compass-seat plan with a distinct break behind the vertical arm scrolls similar to that on some Philadelphia frames. They also show a preference for oak as a secondary wood and a seat frame construction in which the rails are laid with their broad dimension flat and the front legs are tenoned up into the rails—elements that Philadelphia chairs share. Variations of these techniques, however, are common in all compass-seat easy chair frames.

Most certainly present in the robust English frames, but not in Philadelphia examples, are dramatic profiles. The curving outline of the wings proceeds directly from the tops of the posts without an intervening straight ramp. Many English chairs also have curved rear posts that are spliced on the bias atop the cabriole rear legs, whereas Philadelphia chairs typically have straight or nearly straight back frames that are almost totally frontal (or at most ¾ frontal) in their impact.

Because of their overall heaviness and their bold curvilinear forms, English easy, chairs repel the same American collectors that applaud Philadelphia ones; yet, research in areas of design transmission strongly suggests that the frames and the stuffing of Philadelphia chairs had English prototypes. If we try to see Philadelphia easy chairs as embodying a tradition where the first frames were designed by splicing the doublescroll arms of baroque examples onto early Georgian frames, then we find informative parallels between English chairs and the Deshler chair. Both frames have thin board upper wings, or cheeks, normally associated with the use of edge rolls (edge rolls require that the wings be tailored with panels rather than with simple rounded edges that fall away towards the frame), and both required a substantial edge roll on the front seat rail to retain a hear cushion with fairly deep boxing. The back of the English chair may have had stuffing as thick as that of the Deshler chair, which is heavily stuffed by the standards of contemporary New England chairs.[2]

The surviving stuffing and top linen of the Deshler chair contain important clues of the development of Philadelphia upholstery. The seat stuffing, edge roll of the front seat rail, and cushion are lost. Our reconstructions were based on surviving English chairs with original upholstery and cushions and were designed to correct the modern misconception that these chairs had down cushions with tow (approx. 2") boxings. Eighteenth century English cushions frequently have 4” boxings, and Louis XV cushions are often huge, with 5- or 6" boxings. Furthermore, tailoring the cushion so that its upper edges are even with the lower scrolls of the arms pulls the composition together in a way that makes a great deal of sense.

Perhaps the most important insight the Deshler chair offers is in the tailoring of the long seams running from the tops of the wings down to and along the sides of the upper arm scrolls. These seams prove that the linen and show covers of the outside wings and arms were not modeled to emphasize the upper arm scrolls as they often are today. The practice among modern historic upholsterers is to make the inside wing and the inside arm out of two separate pieces, so that the arm fabric can wrap completely around the upper (horizontal) arm cone. This technique allows the outer wing and arm fabric to run in one plane directly under the upper arm cone and butt against the back of the lower arm cone.

On the Deshler chair the inner wing-and-arm cover was made of one piece. The rounded forms required very tricky compass cuts on this one piece of textile at the turn of the wing into the upper arm cone. These cuts left only enough fabric for the textile to reach partially over the upper arm cone. Philadelphia upholsterers hid the compass cuts with a panel that covered the wing and wing edge roll and flared outward at the bottom just behind the upper arm cone. Although this technique was fairly straightforward, they developed a clever solution to the problem of how to shape the outside cover when the inner cover did not completely encircle the upper arm cone: they pinned the outer cover along the outer edge of the wing as far down as the upper arm cone, then pinned it across the side of the arm cone where the inner cover ended. Finally, they worked the cover around and under the cone (although they could never get the fabric to go completely beneath it).

This tailoring method varied slightly from frame to frame. Some upholsterers made sharp turns at the juncture of the upper cones and the panels, whereas others finessed this transitional point with an odd, applied quarter-round bracket. Sharp turns deemphasize the wavering lines of the outside arm panels, whereas quarter-round brackets (which are more revealing of the lines) soften the transition from the upper arm cones to the outside panels underneath them. Period tacking evidence (square shanked tacks with forged heads or holes made by them) varies considerably from frame to frame, but no chair examined by the authors has indisputably original tacking evidence all the way along the innermost areas of the upper arm scrolls.

The upholstery techniques used on the upper arm scrolls of the Deshler chair remained standard practice in Philadelphia and New York from about 1730 to 1830. Modern upholsterers, who are used to rationalized workmanship that conforms tightly to the frame, and collectors, who see Philadelphia frames as lightly padded wood sculptures that should be crisp, neat, and clean, are often puzzled and annoyed by this rediscovered treatment of upholstery; however, this was a period practice, and modern treatments of period frames should seek to recapture this effect.

Another characteristic of late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Philadelphia frames was the extensive use of tacking struts. These struts facilitated stuffing the chair and created clean straight lines at the tuckaways (the junctions of different panels where fabric is drawn through and tacked in place). On the Deshler chair, the junctions are between the back and the wings and between the wing-and-arm panel and the seat deck.[3] Although loose covers might be held in the tuckaways with several loose stitches, on the Deshler example the stuffing was so deep that loose covers could simply be pushed into the tuckaways and held by the pressure of the stuffing alone.

A final point about this frame is the design of the outward-flaring arms. Philadelphia easy chairs dating from the 1730s to the 1790s are framed in a specific way. Each of three successive vertical members—rear posts, wing-and-arm posts, and upper arm scroll posts—tilts a bit more to the outside, contributing to a gradual splay. Although making the arms seem more "inviting," these splayed supports mean that the outer wing-and-arm panels are concave, not flat (the elimination of heavy splay in neoclassical frames flattened the outside wing-and-arm panels).[4]

The interdependence of traditional techniques and stylistic change in the eighteenth century is demonstrated by the tacking evidence left by the lost upholstery foundation of an easy chair made in 1770 for John Cadwalader (1742—1786) of Philadelphia (figs. 8-11). This is the earliest datable easy chair with single-scroll arms and a trapezoidal seat. When the problem of how to develop a nonintrusive (tackless) system for this frame arose, we assumed that the chair was an experimental design, a transitional form, a special order, and a rushed job. Documents associated with building and furnishing Cadwalader's house suggest that he ordered a quantity of furniture from the city's leading cabinetmakers and carvers and that it was produced over an astonishingly short period of time; however, similarities of form and proportion suggest that the joiners who made the Cadwalader frame consulted an English prototype such as that in figures 12 and 13. Although this English chair has a double-scroll frame, the lower scrolls are attenuated, and it is easy to imagine the frame without them and with the lower panels straightened into simple ramps as on the Cadwalader chair. Other parallels include the serpentine crest rail; low stay rail or lower back rail; flat rear back rails; wings with straight ramps leading off from the rear posts; tacking struts; size and moderate splay of the upper arm scrolls; open diagonal braces in the seat frame; and relatively squarish trapezoidal seat plan. Of course, significant differences remain. The English easy chair has upper arm scrolls framed with flat upper boards, long triangular blocks, and skimpy outer rolls that are completely unlike those of Cadwalader's chair or other Philadelphia chairs, and it has applied secondary-wood brackets under the seat rails that support knee brackets made of the primary wood.

What the English frame provides no precedent for are the carved rails on the Cadwalader frame. Carved rails suggest that the Cadwalader chair is not, in strict conceptual terms, an easy chair. The Cadwalader chair is a hybrid of single-scroll easy chairs and "French chairs" (several French chairs with carved skirts, trapezoidal seats, and serpentine fronts were illustrated in plates 17—20 of Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman aged Cabinet-Maker's Director).

Cadwalader's extraordinary carved frame cost.£.4.10.0. The upholstery cost .£.2.3.5 exclusive of the covers, for the frame was finished "in canvas" only. Surviving bills suggest that the chair had a blue check cover and a blue silk damask cover with fringe and silk binding on the seams. It was made en suite with the three sofas that were used in the principal parlors of Cadwalader's house and may represent the rare instance of an easy chair being used in a parlor rather than a bedroom. Cadwalader's wife was of child-bearing age, and this chair may have been intended for her use.[5]

The evidence left by tacks suggests that the chair did not require radically new stuffing or tailoring methods. The wings have chamfered edges that made edge rolls inappropriate and eliminated tailoring the wings with panels. Because we could not infer the appropriate shape of the curled horsehair stuffing from the frame alone, we used another Philadelphia chair with original stuffing as a model for the conservation (figs. 14, 15).[6] On this chair, the stuffing is fairly light at the edges of the chamfered wings but extremely heavy at the tuckaways. Comparable shaping and bulk appear on the arms. The stuffing was intended to soften the interior of the chair for the occupant; however, it had the additional effect of exaggerating the apparent splay of the frame.

The nonintrusive upholstery system developed for the Cadwalader chair left one important question unanswered: how were the seats of both Philadelphia chairs treated? On figure 14, the collapsed seat deck indicates a complete loss of stuffing, but the original bulk can be inferred from the tacking for the top linen of the seat. The front seat rail has tacking evidence that suggests that it had an edge roll but inevitably raises the question of how anyone sat on this chair. If the seat was a tight seat (a seat with no cushion), it would have been substantially padded, but if it supported a down cushion, it needed a heavy edge roll on the front seat rail to contain the cushion. A third possibility is that the chair had a stitched or tufted hair mattress of the same sort mentioned in inventories and seen on the chair in figures 28 and 29.[7]

Unfortunately, the upholstery evidence on this chair did not resolve the question of what the original treatment of the Cadwalader seat was. Because the front of the arm ramps of the Cadwalader chair are only 1" above the top of the front seat rail, the ramps and roll are level when the rail is upholstered with an edge roll. Therefore, we concluded that the seat is not likely to have had a hair mattress. A 1764 portrait by Johan Zoffany shows a sofa with a tight seat that is level with the arm ramps.[8]

A stylish Philadelphia-made neoclassical frame of the 1795—1805 period (figs. 16, 17) appears far more rigid and squarish than the earlier rococo examples. This is not a consequence of the individual panels of the frame, for they are practically identical to those of the chair in figure 14 but of the manner in which they are assembled. The following measurements demonstrate that the rococo frame is lower, wider, and deeper than its neoclassical counterpart and that its arms splay much farther out to either side.

Width at rear seat rail Width at crest rail Width across arms Width at front seat rail Overall height Seat dept |

Fig. 14 24" 27 1/2" 36 1/4" 27 1/2" 46" 23 3/8" |

Fig. 16 22 5/8" 25 1/2" 30 1/2" 26 3/4" 48" 24 3/4" |

On the tight, beautifully stuffed neoclassical chair an entirely new effect was achieved using the same patterns. All the framing of the side panels is on a single plane, which makes the chair quite boxy and prevents the scrolls from extending out any great distance. Most remarkable are the original board linings for the wings, arms, and back. Although some scholars might interpret these foundations as a rural deviation, or at the very least as an economy measure, the sophisticated design of the frame proves that it is an urban product, Moreover, the savings in fitting and nailing the board linings would have had little impact on the cost because the utilitarian heavy linen of which the sackcloth in the frame usually was made was not very, expensive. Board linings probably were intended to block strong drafts that easily penetrate the stuffing of a chair.

Despite the use of board linings on the neoclassical chair, no holes are present that indicate that the upholsterer used twines to anchor the horsehair stuffing of the back in place. Two holes in each arm lining mark the location of original trines for the arm stuffing. Settling of horsehair stuffing in frames is a common failure, quite apart from the displacement of stuffing because of restless heads, backs, and elbows. This was a critical problem when curled horsehair was laid over wood, which, unlike a textile, offers little to cling to. The presence or absence of twining to secure stuffing is a key factor in understanding upholstery practices of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Although American upholsterers were using twines to secure stuffing by the mid-1770s, fully stitched upholstery foundations were first executed in New York and Philadelphia during the 1790s.[9]

Although the serpentine (or "commode") front seat rail makes the chair in figures 16 and 17 appear deeper than it actually is, the frame is relatively high, narrow, and shallow. The heavy bulk at the tuckaways guaranteed that the occupants were squeezed in between the wings and arms. Although the original stuffing of the seat is lost and it is not clear how it was treated, the ramps at the bottoms of the arm panels are relatively low. As in the previously discussed frame, this suggests that the chair may have had a hair mattress rather than a down cushion.

The foundation upholstery of the neoclassical chair reveals two other important features. First, the tailoring of the outside of the frame, with long seams that run from the crest along the edges of the wings and onto the sides of the arm scrolls, is similar to that of the Deshler easy chair. Second, this frame did not have fixed covers until the late nineteenth century when chintz covers (fragments survived) were amateurishly tacked to the frame. The original tacking sites indicate that the chair had a loose cover and support documentary evidence that loose covers were not limited to chairs with close stools.

The chair in figures 18 and 19 illustrates several options and stylistic details that were available during the late rococo and the early neoclassical periods and that were described in The Journeyman Cabinet and ChairMakers Philadelphia Book of Prices (1795) and The Journeyman Cabinet and Chair Makers' Pennsylvania Book of Prices (1811) . The heavy, low proportions of this late rococo frame are common among mid-eighteenth century English chairs but rare in the United States. The seat is deep and consists of a loose (or slip) seat that must be pulled straight forward to be removed, given the bulk of the arm stuffing. This loose seat covers a simple arrangement: four large vertical corner blocks, two side tracks with rabbeted upper edges, and a board with a hole that rests in the rabbets. No provisions were made for an upper seat board to separate the user and the rim of the pewter pan.

The plain legs divert attention from two unusual features of the undercarriage: the rear legs are absolutely vertical, and no rear stretcher connects them. The first feature has a straightforward explanation: because the frame contained a close stool, the chair probably had a loose cover with shirred bases (dust ruffles) to conceal the pan, and straight rear legs would have allowed the bases to fall straight to the floor. The absence of a rear stretcher was an option cited in some price lists. Normally it was combined with tracks nailed under the seat rails to support a pan rack that slid out the rear of the chair, but racks are absent on this chair. Perhaps the owner preferred to place a ceramic chamber pot on the floor below the opening as an alternative to hanging a pewter pan.

At 13 1/4" high including the slip seat, the seat seems remarkably low. The undersides of the feet have marks from two successive sets of casters, one of which may have been original. The casters would have brought the seat to about 14½" in height, still a bit low but acceptable for a small, elderly person. As the frame sits without casters, the stretchers are 3" from the floor, whereas on most eighteenth-century chairs stretchers are about 4" to 4½" from the floor. The frame has curled horsehair stuffing heavily applied over the entire surface of each panel. The outside wing-and-arm panels have continuous seams running down the wings and onto the sides of the arm cones, as with the Deshler example. The chair has experienced heavy use; its linen foundation covers have been patched repeatedly and restless elbows have dented the arms on both sides.

Although this chair conforms to Philadelphia designs, the slip seat is inscribed "Sitting/Chair/and/pot/Winchester/Virginia." Although it is possible that the chair was taken to the Valley of Virginia from eastern Pennsylvania, it could as easily be a Winchester product, because many artisans from the Delaware Valley resettled in the Shenandoah Valley during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

A very similar easy chair could have been made in either Philadelphia or New York City (fig. 20). It is approximately the same size as that in figure 18, although the seat is about 1" higher (if an inch is added to the previous chair's seat height to compensate for lost casters). It has a more elaborate close-stool arrangement with a lift-out panel that separates the user from the rim of the pewter pan. On it, too, long seams run down the wings and the sides of the arms.

Almost unquestionably from New York City, the easy chair in figures 21-23 is later in date. It has a heavy frame and lyre arms that extend (in their scroll shape) to the rear of the frame. Such arms are extremely rare on American examples, and the chairmaker carried the shape of these mahogany faced arms to the rear of the frame by applying haunch blocks to the sides and the back of the rear posts. Another unusual feature is the high arched crest, possibly a holdover from earlier New York chairs. The heavy, turned legs have carved beads and socket casters, the latter of which were introduced about 1810. The close-stool board, which has a hole for a pan, was secured with glue blocks and was covered originally by a slip seat (here restored).

The framing of this New York chair has other unusual features besides the peculiar haunch blocks. The wings are solid boards, and the crest rail is extraordinarily deep. These details and the overall heavy framing make the chair exceptionally stable (its closest parallel is an equally massive New York settee made for Daniel Wadsworth of Hartford about 1825). Its strong, exquisitely made frame is similar to those made in Regency London.

The restored loose cover suggests what the chair might have looked like when in use.[10] The shirred bases stop above the floor to avoid snagging in the caster wheels. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, loose covers often were fabricated around the arm panels and generally were fairly snug. Because the original outside wing-and-arm panels of the top linen were not basted to follow the front-to-rear curve of the arms precisely, the slipcover was loosely tailored in those areas. As with other easy chairs, the long seams run from the wings onto the sides of the arm scrolls. A traditional indifference to the tailoring of the outside arms may explain the original upholsterer's failure to fit the fabric to the lyre scrolls more closely. The tape ties of the rear corners are one of several systems for closing eighteenth- and nineteenth-century loose covers, others being hooks and eyes and light tacking.

Scholars frequently have associated chairs of a lean, somewhat pinched design with New York. One such example is that in figures 24 and 25, although it lacks the ogee turning above the casters that is typical of early nineteenth-century New York turning. On this chair, each side panel is built around a large plank to which modest half-rolls are applied.[11] The extremely thick padding of the wings and arms minimized the skimpy lines of the frame. Slots cut in the plank panels to thread the webbing through demonstrate that this was a standard frame that someone simply adapted for a close stool since no webbing is needed over a plank supporting a slip seat. The chair retains its original turned lid, or stopper, for the seat hole. The track nailed under the seat indicates that it was intended to have a ceramic chamber pot, for the tracks held a box or rack in which the pot rested and the rack could be pulled out to empty the vessel after use. Similar tracks sometimes supported frames or boxes that slid out from the front accommodating rests for gouty legs and feet.

A provincial version of the same style of chair has an elliptic front rail, serpentine crest, and open diagonal struts in the seat frame (figs. 26, 27). Holes in the side panels suggest they were intended for twines to secure the stuffing, which in the original back foundation is a deep laver of tow (crushed flax stems). Tow was used frequently during the early nineteenth century, despite its tendency to crumble and compress with use. The front rail is padded by a substantial roll stuffed with reeds. The difference in the height of the roll and small vertical arm cones suggests that the chair had a cushion seat.

The Philadelphia chair illustrated in figures 28 and 29 is a highly inventive variant of the standard circular chair produced from about 1805 to 1820. These chairs were framed on a D-shaped plan and required that the seat rails and crest rails be laminated (brick-built). On this example, the seat rails are three laminations high and the crest is five. What distinguishes this frame is the structure of the back. On most circular easy chairs, the crest is mounted on extensions of the rear legs, that results in frames having practically no rake or layback.

By, adapting the framing system then generally used on cabriole sofas, the chairmaker overcame the limitations of traditional circular chair design. He mounted the crest on three struts, toeing the center strut on the rear seat rail and toeing the two outer struts in front of the rear leg tusks. He set the struts at so radical an angle that the rear edge of the crest is 12¾” behind the rear seat rail. Because the rear legs extend only a few inches above the seat rails, he could not frame the arms into them, and they extend from the outer back struts to the front struts. He framed the wings into the crest rail and the arms. All this unusual framing resulted in a narrower back and wings that met the arms much farther back than on most circular chairs. Most chairmakers extended the wings so far forward that practically none of the arm scroll was available for an armrest.

The narrow back of figure 28 has four flutes rather than the usual five. These are sharply tapered (from an average width of 5" at the top to 3 1/4” at the bottom) to compensate for the severe rake of the back. As the rear view shows, the central crease between the two inner flutes was tacked to the front face of the central strut, whereas the others were twined and either tied off on the sackcloth or tacked to the outer struts. Striped ticking was used as the sackcloth. The front edge roll was stuffed with chopped wool, known as "flocks" or "dust" during the period. The roll contained the tufted and stitched hair "mattress," which has a 2" boxing.

The mattress covers a loose pan-hole cover and a square panel that can be lifted out to empty the pewter pan. The deck is lined with linen and the one-piece deck board is held in place by several small glue blocks. The legs on the frame may have lost small conical turnings under the surviving ring turnings. The seat rail height is now 14½". With the 2” cushion, the original seat height would have been about 17". It is difficult to imagine a chair of this height being used without a footstool.

A New England easy chair with a close stool and four heavy vertical turned legs provides an interesting contemporary comparison with the later mid-Atlantic examples (figs. 30, 31). The heavy frame is beautifully constructed, and the chair retains its original Spanish moss stuffing. Spanish moss was used frequently by northern urban upholsterers after 1790 and was especially favored for mattresses. The springing in the slip seat is a later addition that distorts its shape, and the seat board with pan hole is missing. The back slats are original and have holes drilled for twines that secured a bed of grass that supplements the Spanish moss laid over it. The slats are thin enough to flex under the occupant's weight, yet thick enough to block drafts. The loss of the outer linen has not obliterated the evidence of the standard long seams running down the edges of the wings and along the sides of the arm rolls. As on the chair illustrated in figures 18 and 19, the four straight legs permitted the shirred bases to hang straight to the tops of the casters.

The New York chair illustrated in figures 32-34 had a pot rack that slid out from the rear, and the frame was constructed without a rear stretcher. What distinguishes this chair is the extremely thick stuffing of the wings with lamb's wool and a skimmer of hair. The stuffing is thick right up to the lead edges of the wings; it was secured with twine that passed through a series of holes drilled along the edges of the wings. The bulk and composition of the stuffing identifies the chair as a rural product that may have been upholstered by a saddler. Another rural example is a New Jersey chair with eccentric construction and stuffing techniques (fig. 35) . The frame was made without back posts; the wing-and-arm panels and the back frame are pegged together with long wooden pins. The arm framing was laid on top of the seat planks, which in turn were nailed atop the seat rails. Although the seat planks have been sawn out, originally they probably contained a pot hole. The most unsophisticated details are the black ash splint webbing with textile tacking strips and the corn-husk edge rolls on the arms. The original stuffing is lost, but, according to the previous owner, it consisted of grass with a skimmer layer of tow.

Our joint examination of easy chairs during the last five years has allowed us to expand our understanding of the use of easy chairs in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and has provided us with benchmarks to assist curators and conservators interested in stuffing and tailoring frames in museums and private collections. Our goal now is to encourage museums to aggressively collect frames with original upholstery and to remind even well-meaning collectors that irrevocable damage occurs when they seek to reinforce original foundations enough to be sat upon. Use of these objects is dangerous, for often the textile components are so weak that they cannot take the stress. Loose covers provide curators an excellent solution to the problem of preserving fragile foundations and making an object presentable for display. The tailoring of such covers is not that difficult, and the covers can range from being closely to loosely fitted. A looser fit is best if the covers are to be removed with any frequency, as a great deal of damage can be inflicted on the original textiles by abrasion alone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following for their help at many stages of compiling the essay and catalogue: John Bly, Frances Bretter, Harold Chalfant, Anthony Collins, Stephen Corrigan, Richard Dietrich, George Fistrovich, Christopher Gilbert, Morrison Heckscher, Barbara Hencheck, John Hencheck, Frank Horton, Douglas Jackman, Leigh Keno, Joe Kindig III, Frank Levy, Jack Lindsey, Robert Luck, Alan Miller, Steven Pine, Deborah Rebuck, Robert St. George, George Sansoucy, Elizabeth Schaefer, Darien Sergeant, Gar v Sergeant, Bruce Sikora, Frederica Struss, Susan Swan, Ronald Vukelich, and Manfred Woerner. We extend special thanks to Luke Beckerdite for his help throughout the editing process.

This chair is part of a large suite of furniture probably owned by David Deshler of Germantown. The knee carving matches carving on eight side chairs, several of which have slip seats with an eighteenth-century ink inscription "Deshler." One of the marked side chairs was illustrated in "Exhibition of Furniture of the Chippendale Style," Bulletin of the Philadelphia Museum of Art 19, no. 86 (May 1924) : 164, pls. 4, 9, with a Fisher family chair, but the captions were switched. The easy chair descended in the same line as the side chairs, and the mixup in captions led scholars to associate the easy chair with the Fisher rather than Deshler families. The authors are grateful to Alan Miller for clarifying the history of the easy chair. Mark Anderson, Robert Trent, Dora Shotzberger, Ruth Lee, and Terry Anderson conserved the foundation upholstery and fabricated the cover in 1989. Alan Miller of Quakerstown, Pennsylvania, conserved the frame.

See Andrew Passeri and Robert F. Trent, "Two New England Queen Anne Easy Chairs with Original Upholstery," Maine Antique Digest 11, no. 4 (April 1983): 26A—28A; and Edward S. Cooke, Jr., "The Nathan Low Easy Chair: High Quality Upholstery in Pre-Revolutionary Boston," Maine Antique Digest 15, no. 11 (November 1987) : 1C—3C.

The bills for the easy chair frame, foundation upholstery, covers, and fabrics are reproduced in Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), pp. 40—41, 44, 51, 69.

Dora Shotzberger and Ruth Lee fabricated the loose cover. Susan Heald conserved the top linen.