Draw table, Dutch, 1660–1680. Oak and ebony. H. 32 5/8"; top: 36" x 59 3/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Old Dutch Church, North Tarrytown, New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

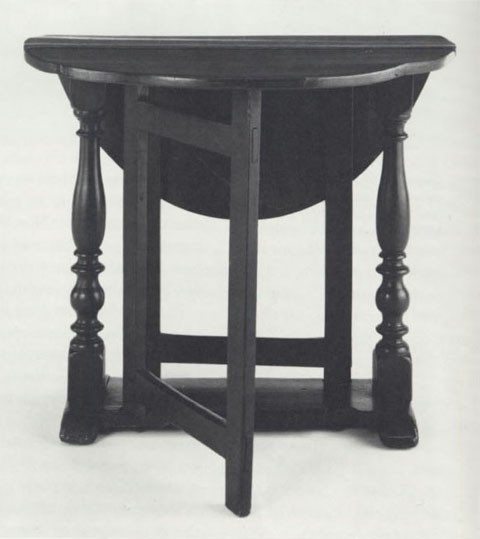

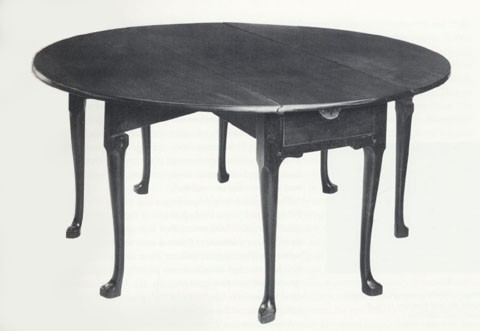

Oval table with falling leaves, New York City, 1700–1730. Mahogany with maple and yellow poplar. H. 30 1/8"; top: 58" x 72 1/4" (open). The table may originally have belonged to Philip Van Cortlandt (1683–1748) and his wife Catherine De Peyster (1688–1766?) who were married in 1710. (Courtesy, Historic Hudson Valley, Tarrytown, New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York, 1720–1750. Red gum with yellow poplar. H. 28 1/2"; top: 35 1/2" x 45 1/2" (open). Branded twice on the underside of the stretcher are the initials ATB (conjoined), which may stand for Abraham Ten Broeck of Albany (1734–1810), an owner, not a maker. (Collection of Peter Eliot; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves attributed to the Elting-Beekman shops, Kingston, New York, 1700–1730. Red gum and maple with pine and oak. H. 28 1/2"; top: 48 1/2" x 58" (open). The table was purchased by its current owner out of an old Hurley, New York, home. It retains its original top, although its far leaf is off and not included in this photo. The exaggerated shape on the edge of the thick top is characteristic of this shop tradition. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

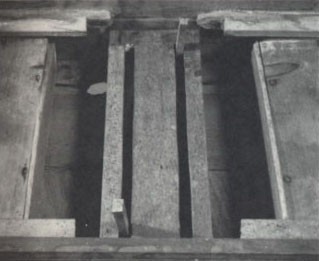

Detail of the draw-bar track on the table illustrated in fig. 10. Pegs that are rectangular in section and inserted in the draw bar at an angle slightly less than 90 degrees are typical of tables attributed to the Elting-Beekman shops. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

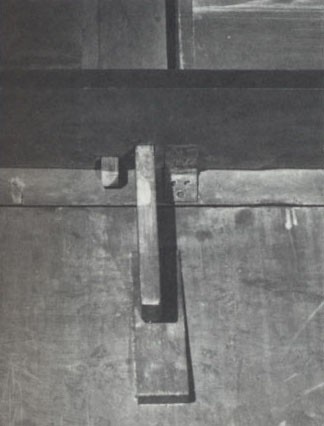

Detail of the draw bar on the table illustrated in fig. 4. A prominent feature of the draw bars on tables by the Elting-Beekman shops are cut fingerholds. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, Southern New York or Northern New Jersey, 1701–1730. Walnut with cherry and sweet gum. H. 26"; top: 38 7/8" x 43 1/2" (open). (Digital file, ©The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of the Antiquarian Society through the Mr. and Mrs. William Y. Hutchinson Fund, acc. 1985.241. All rights reserved.)

Detail of the draw bar and boxlike draw-bar guide inside the frame of the table illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Art Institute of Chicago.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York, 1700–1720. Cherry with maple. H. 27 1/2"; top: 44 1/2" x 47" (open). The smallish top, which is original, was affixed originally by long iron rivets that passed all the way through the aprons and were covered by face-grain plugs in the top. The drawer pulls have their original, late Jacobean-style cast backplates. (Collection of Peter Eliot; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, attributed to the Elting-Beekman shops, Kingston, New York, 1740–1770. Red gum with pine and oak. H. 28 1/8"; top: 50" x 60 3/8" (open). This is the only table with end drawers attributed to the Elting-Beekman shops. The draw-bar track inside the frame usually discouraged this feature. (Courtesy, Huguenot Historical Society, New Paltz, New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Oval table with falling leaves, New York City, 1690–1730. Red gum with yellow poplar and pine. H. 29 3/8" (minus top); frame 20 3/8" x 35 7/8". The top and finial on the crossed stretchers are modern replacements. The graining on the aprons and lower leg blocks probably dates to the early- to mid-nineteenth century. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York City, 1680–1710. Walnut with pine. H. 28 1/2"; top: 42 3/4" x 19" (center section only). The leaves, finial, and possibly the feet are modern replacements. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 59.5.)

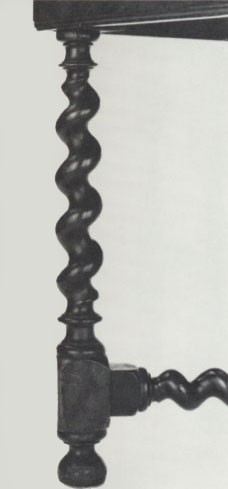

Detail of the single-twist leg on the table shown in fig. 11. The leg tapers from a diameter of 2 5/8" at the ring on top of the bottom block to 2 1/8" at the top ring. The upper reel on the leg is skillfully diminished in proportion to the taper. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, attributed to the Elting-Beekman shops, Kingston, New York, 1770–1800. Red gum with yellow poplar and pine. H. 28 1/2"; top: 48 1/2" x 58" (open). This table has a history of ownership in the Vanderlyn family of Kingston and is in a remarkable state of preservation, retaining nearly the full original height of its feet. (Courtesy, Senate House State Historic Site, Kingston, New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, unidentified New York cabinetmaker, 1749–1763. Mahogany, sweet gum, yellow poplar and eastern white pine. H. 29 1/2"; top: 71" x 78 1/2" (open). (Albany Institute of History and Art, Gift of the heirs of Major-General John Tayler Cooper; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York, 1690–1730. (Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury [Framingham, Mass. 1928], 1: no. 943; current location unknown.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York, 1690–1730. Cherry with yellow poplar. H. 27 1/2"; top: 47 1/2" x 36 1/8" (open). This table and the one in fig. 9 have lambs’ tongues carved on the corners of their leg blocks. The reserve area on the face of the leg blocks are in the shape of baroque ogee arches as a result of this decorative carving. The moldings run on the flat gates are similar in scale and profile to the applied single-arched moldings on early high chests and other case furniture. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, acc. 1926.492.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York City, 1690–1720. Mahogany with maple, yellow poplar, and oak. H. 28 7/8"; top: 40 3/4" x 44 1/2" (open). (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York, gift of the Reynal family; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York City, 1700–1740. Mahogany with yellow poplar and oak. H. 28 3/8". Except for the use of turned versus plain stretchers, this table is nearly identical to the example illustrated in fig. 18 and is probably by the same hand. The top appears to be a modern replacement. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York City, 1740–1760. Mahogany. H. 28 1/2"; top: 53" x 67" (open). This is a considerably smaller version of the Sir William Johnson table (fig. 17). (Private collection; photo, Christie’s).

Oval table with falling leaves, possibly Flushing, New York, 1690–1730. Cherry with pine. H. 27 3/8"; top: 45" x 61" (open). This table and three carved-top Boston leather chairs (one of which is illustrated here) were given to Washington’s Headquarters by the Verplanck family between 1858 and 1872. A dressing table discovered in Flushing, Long Island, with closely related turnings, possibly by the same shop or school of makers, is illustrated in Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Elizabeth Bidwell Bates, American Furniture 1620 to the Present (New York, 1981), p. 65. (Courtesy, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, Washington’s Headquarters State Historic Site, Newburgh, New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval gate-leg table with falling leaves, New York, 1690–1730. Red gum, maple, H. 26 1/4"; top: 30" x 34 3/4" (open). (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Eleanor G. Sargent, 1980, acc. 1980.499.1; All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

End view of the table in fig. 3 showing the typical heavy dovetail joinery at the top of the upright where it connects to the thick board that supports the top. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York, 1720–1750. Red gum. H. 28 1/4"; top: 33" x 39 1/2" (open). This trestle-base table with flat gates differs from the two other illustrated examples in that its turned uprights are tenoned up into a cross piece at the top rather than dovetailed to a thick board. The severe warp in the top is typical of flat-sawn red gum, a notoriously unstable wood. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

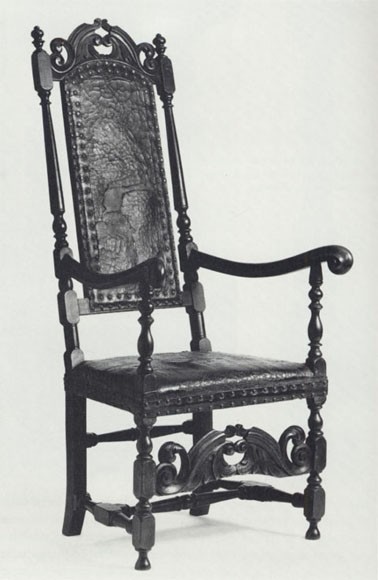

Cane armchair, England, 18th century, ca. 1685-1689, walnut. 57 x 30 3/4 x 19 3/4 in. (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918, acc. 18.110.18, All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

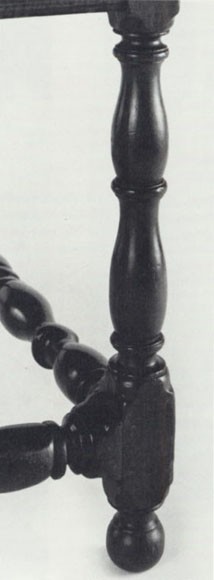

Detail of a leg from the Van Cortlandt family table (fig. 2). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a leg from the table illustrated in fig. 9. The ball-shaped foot is a modern replacement as are most of the lamb’s tongue carvings on the lower corners of the bottom leg block. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

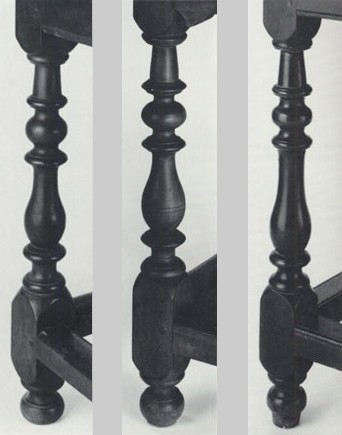

Composite detail of legs from tables attributed to the Elting-Beekman shops at Kingston; left (fig. 4), center (fig. 10), right (fig. 14). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Composite detail of urn-and-baluster turned legs; left (fig. 18), center (fig. 21), right (fig 15). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Carved-top leather armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and red oak. H. 53 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 58.553.)

Oval table with falling leaves, New York City, 1735–1765. Mahogany. H. 28"; top: 61" x 65 1/4" (open). Representing a later phase of the baroque style in New York City tables, this example is approximately contemporary with Sir William Johnson’s table (fig. 15) and shares its use of mahogany and barrel-like rule joints. The cyma curves cut into the ends of the rail appear to be segments of the sweeping, cyma and half-round cutout shapes on the Johnson table drawer fronts. (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy Inc., N.Y.C.; photo, Helga Studio.)

Detail of a wrought iron dovetail hinge on the table illustrated in fig. 18. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the face-grain plugs that cover the countersunk rivet heads on the top of the table illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the drawer from the table illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

The substantial body of surviving oval tables with falling leaves made in New York City and in the rural towns of the Hudson River Valley, Long Island, and central and northeastern New Jersey from the late-seventeenth through the mid-eighteenth century comprise a remarkable group that is structurally and ornamentally unconventional—in comparison to their New England counterparts—and redolent of a bold baroque design ethos. These tables present a brief but fascinating chapter in American furniture history and a peculiar interpretive challenge as by-products of Anglo-Dutch cultural fermentation in late-seventeenth-century New York.

In medieval times dining tables were the largest and most cumbersome pieces of furniture next to beds. They could be built-in or, as was sometimes the case with trestle tables, taken apart and either stored away or moved to another location. By the 1500s, however, societal changes began rendering these behemoths obsolete. Large, transient medieval households with mostly portable possessions gave way to smaller households occupying year-round dwellings. In the interest of conserving space in these furniture-filled interiors, joiners found ways of reducing the sisze of dining tables without sacrificing too much surface area.[1]

In England, two types of dining tables with relatively compact bases and tops that could be expanded or reduced in size emerged by about 1550. Furniture historian Victor Chinnery suggests that the earlier of the two designs consisted of a heavy, open-frame base and a fixed rectangular top with hinged, floor-length leaves attached to the ends. When raised, the leaves were supported by heavy lopers or draw bars pulled out from inside the frame. This rather awkward design apparently never came into wide use, but hinged or falling leaves, as they were known in the period, presaged subsequent advances in variable-top dining table design. A slightly later development was the considerably more elegant draw table, or “drawing” table as the form was referred to in sixteenth-century inventories. This design featured an open-frame base and a large rectangular top that rested loosely on a fixed transverse center board and had leaves inserted at either end. When drawn out from under the top, the leaves cantilevered off the frame on tapered rails that ran in tracks inside the aprons and were held in compression, at full extension, by the fixed transverse board. Draw tables were extremely popular in England and northern Europe during the late Renaissance and continued in production and use well into the baroque period.[2]

Tables with oval-shaped tops and falling leaves are most closely associated with the reigns of Charles II and James II, and, as furniture historian David Barquist suggests, they may be a purely English innovation. The genesis of the form may lie in the trend toward more relaxed, informal dining in late-seventeenth-century England. The oval shape tended to sublimate issues of precedence in seating.[3] Lighter and more portable than their earlier, variable-top counterparts, these tables could be set up in the center of the room for meals and stored with the leaves down against the wall after use. The leaf supports were no longer heavy lopers but stylishly turned auxiliary leg supports consisting of two uprights linked by parallel rails. The inner upright pivoted between the bottom edge of the side apron and the upper face of the side stretcher, giving the whole assembly the look of a swinging gate, hence the modern term—gate-leg table. Seventeenth-century appraisers generally described these tables by size, primary wood, or the shape or kinetic action of their tops.

Rectangular dining tables of traditional late medieval and Renaissance form, including draw tables, were made and used in New England from the 1630s onward, whereas oval tables with falling leaves first came on the scene there in the 1660s. One of the earliest references is the “Ovall Table” and set of twelve “Turkey worke chayres” in the 1669 estate inventory of Antipas Boyse of Boston.[4] From their inception, these tables were meant to harmonize with the sets of turkeywork, cane, and leather chairs sold by Boston merchants. Consequently, Antipas Boyse’s oval table with falling leaves probably had the repetitive spherical turnings of the stylish, low-back “Cromwellian” chairs of the 1660s and 1670s, whereas examples from the 1680–1730 period had baroque twist, baluster, vase, and urn-shaped turnings resembling those of imported and domestic high-back cane and leather chairs.

A similar pattern of development seems to hold true for New Netherland and early colonial New York, although dining tables of the early rectangular form are exceedingly rare. Oval tables with falling leaves survive in considerable number, but the paucity of inventories dating before 1680 makes it difficult to determine if the form was in use in New York City as early as in Boston. It seems unlikely that it was, given that this apparently was a purely English furniture form and, as historian Michael Kammen has pointed out, Anglicization did not occur in New York on a large or permanent scale until nearly a generation after the English conquest of 1664.[5]

The 1686 estate inventory of Cornelis Steenwyck, one of the wealthiest residents of New Amsterdam and twice mayor, lists an “ovall table” as well as a dozen Russia leather and rush-seated chairs in the “kitchen chamber,” a sort of common family living room. In the “great chamber” or best room, however, a “square table” valued at £10 is listed, along with a dozen “Rush leather Chyres” and two “Velvet Chyres with fine silver lace.” The high value assigned to this table and the presence of fourteen chairs suggests that it was an especially fine example, possibly having an expandable top; an imported Dutch baroque draw table of rich rosewood and ebony immediately comes to mind. Physical and documentary evidence proves that draw tables were imported and used in New York Dutch homes long after the English conquest; the physical proof is witnessed in an oak and ebony example with a solid Phillipse family history (fig. 1), and the written record includes the “square table that pulls out” that was listed in the 1711 estate inventory of Margareta Schuyler of Albany.[6] Although draw tables and references to them are rare, it seems likely that they provided some competition early on for oval tables with falling leaves among this segment of the population, especially if the latter form was perceived as English.

Only a handful of late-seventeenth-century inventories list oval tables with falling leaves, and few references from any period specify their use. Englishwoman Charlotte Lenox’s account of a sumptuous tea in the home of one New York Dutch family in the late 1730s or early 1740s describes how such tables were set up in a room and laid out with food and napery from the earliest period of their use:

Immediately after the tea equipage was removed, a large table was brought out, and covered with a damask cloth, exquisitely white and fine; upon this table were placed several sorts of cakes, and teabread, with pots of the most delicate butter, plates of hungbeef and ham, shaved extremely fine, wet and dry sweetmeats, every kind of fruit in season, pistacchio and other nuts, all ready cracked. . . . The liquors were cyder, mead and Madeira wine. All these things were served in the finest china and glass.[7]

Tables with Draw-Bar Supports

The approximately sixty surviving early baroque oval tables with falling leaves can be divided into two broad categories based on their method of leaf support: those with pivot-leg supports (figs. 2, 3), and those with draw bars or lopers (fig. 4). The majority are of the former type. Although distinctive in their own right, New York tables with pivot legs follow a common English design formula adopted throughout the colonies in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. However, tables with draw-bar supports are unique to New York, and the seventeen surviving examples represent about 30 percent of the total.

Draw bars or lopers are rudimentary support mechanisms. They appear on a few sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English dining tables with variable tops and on a few other early English table forms, but not on any English or Dutch tables directly analogous to the New York examples. The way the support system works is simple and obviously related to the mechanisms of the earliest draw tables and variable top tables with falling leaves.[8] Two wooden bars, rectangular in section, run in a slotted board (or track) mounted transversely inside the table frame (fig. 5). Square- or round-section pegs tenoned into the bottom of the bars engage the slots and serve as stops when the bars are drawn out from inside the frame through the openings in the side aprons (fig. 6). The draw bars are usually made of heavy stock, but a few are similar in scale and section to the lopers on early baroque, slant-lid desks (figs. 7, 8). Draw bars may be partially responsible for the broad proportions of the tables on which they are used, since the frames had to be wide to accommodate draw bars of sufficient length to support the leaves. The wide, sturdy stance of the tables (figs. 9, 10) is complemented by proportionately stout legs, which consistently measure at least 2 1/2" in diameter or larger, a stock size that allowed the turner to work deeply into the wood for dramatic effects.

Five of the tables with draw-bar leaf supports have bold, twisted legs and dramatic X- or double-ended Y-shaped stretchers (figs. 11, 12). The walnut example illustrated in figure 12 is probably the earliest of the draw-bar tables. Its stretcher design parallels that of the 1660–1680 Dutch-made draw table owned by the Phillipse family (fig. 1), and the ovolo-and-bead rail molding matches that on the door frames of the four earliest surviving American kasten. That this distinctive molding has only been found on seventeenth-century, Dutch-influenced furniture strongly suggests that the maker was of Netherlandish rather than English descent. If so, this table is a late-seventeenth-century Dutch New York joiner’s adaptation of a new and unfamiliar English table form. To accommodate the Dutch-derived stretcher system, he had to utilize that most rudimentary of support mechanisms, the draw bar or loper, and in so doing created a new and distinctive Anglo-Dutch table form, one that today serves as a sensitive indicator of cultural blending in early colonial New York.[9]

The four other twisted-leg tables have a slightly different aspect due to their boxlike, dovetailed frames and separate legs pinned up into the corners (fig. 11). Although this construction initially appears rickety, it allows for a firm connection between the legs and the X-shaped stretchers. (Pinned legs can be rotated so that their bottom blocks face each other at opposite corners.) The difference between the boxlike frames with pinned legs and the mortise-and-tenon frame and leg construction is reminiscent of a change that occurred over time in American kasten design. Around 1700, boxlike, dovetailed base units with ball-turned feet pinned up into the front corners began to replace the heavy post-and-rail facade construction of seventeenth-century examples.[10]

The twelve other tables with draw-bar supports all have box stretchers aligned with the frame and legs with a variety of early baroque turnings, including vases, rings, balusters, and urns (see figs. 4, 7, 9, 10, 14). Pivoting gate-leg supports could have been used on these examples, but for at least two reasons were not: the draw-bar system saved the expense of turning and framing the gate legs and avoided the annoyance of sitters occasionally having to straddle a pivot leg. Plain molded stretchers appear on all but one table (fig. 9), and they strike a slightly discordant note in the overall design when compared to the elaborate turnings. However, the stretchers and the broad overall proportions of the tables (figs. 4, 10) provide a visible link to earlier heavy, stretcher-base tables with stationary tops, such as the square table, a rare form now thought only to have been made in New England.[11]

Tables with Gate-Leg Supports

Gate-leg tables are of two types, classic examples with turned uprights and stretchers in the gates, and simpler ones with gates made from molded boards. Most prominent among the former type are the Sir William Johnson table (fig. 15) and the Van Cortlandt family table (fig. 2). The reputations of these two tables were established in the early years of this century when Esther Singleton and Luke Vincent Lockwood published them in their pioneering books on American furniture. Since then these tables have come to be considered the beau ideals of New York early baroque table design. (Wallace Nutting reproduced the Sir William Johnson table in the 1920s and went so far as to call it the “Supreme Gate Leg” in the catalogue of his reproductions.) Based on their massive scale and the quality of their design and workmanship, the reputations of these two tables are well deserved. What further distinguishes them as high-end luxury items is their primary wood, mahogany. Singleton considered the Van Cortlandt table an especially early example of the use of mahogany in the colonies, an observation that was astute and remarkably prescient; several New York tables made of mahogany with turned pivot-leg supports have since come to light (figs. 18, 19, 20, and another in the collection of the Monmouth County Historical Association in Freehold, New Jersey). Half a dozen examples of native cherry (fig. 21), walnut, and maple round out the classic gate legs, bringing the total up to twelve. Although it is fruitless to try to equate survival rates of specific types with their popularity, it is instructive to compare the iconic “William and Mary” gate leg with the other surviving New York oval tables with falling leaves to show that this design was only one of the options available to New Yorkers in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.[12]

Tables with gates made of flat boards account for the greatest number of New York oval tables with falling leaves. Of the approximately thirty examples known, only six have four legs and box stretchers (fig. 16); the balance have trestle bases with two uprights connected by flat low stretchers (fig. 17). These tables caught the eye of Lockwood and Nutting, both of whom illustrated examples in their books on American furniture. Nutting commented that tables of this design had recovery histories in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachussetts; however, his failure to mention New York has clouded regional attributions ever since. Of all the known examples, only one (fig. 3) can be linked to a likely eighteenth-century Albany owner through a brand on the underside of its stretcher. Yet there are overwhelming reasons to attribute these tables to New York rather than to New England: most have been found and offered for sale by dealers in the Hudson River Valley; many are made of red gum, a wood used as a cheap substitute for mahogany in New York, but not in New England; and their turnings and leg-stock dimensions are clearly related to those of documented New York examples with draw bars and gate legs, but they bear little relation to those of 3 New England tables.[13]

The tables with flat gates and trestle bases have tops that measure, on average, about ten inches less in overall length and width than the tops on their four-legged counterparts with draw-bar and gate-leg supports. (The Johnson and Van Cortlandt tables are excluded from this calculation because they are abnormally large.) Tops range in size from 36 1/8" x 47 1/2" (fig. 17) to 30" x 34 3/4" (fig. 22). The smaller tables may have been used for tea or light meals, or as service stations alongside grander, oval-topped dining tables; the larger ones could comfortably seat four and may have served as the principal dining table in some households.

The beauty of these tables is in their compactness and the ease with which they can be moved and stored. With the leaves down they are seldom over a foot wide (fig. 23). The 1724 room-by-room inventory of Gertruy Van Cortlandt’s home in New York City suggests that she lived in a tall, two-storey, Dutch-style townhouse and used one of the smaller trestle-base tables there. On the first floor were an entry, front and back parlors, a closet, and a kitchen dependency. Listed “in the closet,” not necessarily a closet as we think of one today but a small room adjacent to or between the parlors, were a total of nine pieces of earthenware, a stone jug, a whitewood chest, a candlebox, and “1 ovall table.”[14]

Major structural variations indicate that these tables represent the work of several shops. (Paired versus single board stretchers [figs. 17, 24] and mortise-and-tenon versus dovetail joints where the uprights meet the support structure of the top.) The consistent use of mortise-and-tenon and dovetail joints (fig. 23), suggest that most were made by joiners rather than turners. The tables are workmanlike and sturdy. The quality of their design and construction is superior to most New England shoe-foot, trestle-base tables with falling leaves, which typically have a turned stretcher joined higher up on the posts and vertically oriented rails supporting the tops (as opposed to the flat rails on the New York ones). Today, many of the New England examples are rickety and unstable, a condition as much attributable to their original design and construction as to their antiquity.

New York four-legged tables with flat gates (fig. 16) are a curious blend of the classic design with trestle-base examples. The end rails are like those on most four-legged tables, but the side ones are unusual in being turned flat side down and lapped into the tops of the legs so that they are nearly invisible and provide extra room for knees. Unlike all but one other New York falling-leaf table with plain box stretchers (fig. 7), the stretchers on these tables are oriented so that their broadest surfaces are in a vertical plane. This orientation relates well visually to the framing members of the flat gates.

Though the tables with draw-bar supports evidently are a hybrid Anglo-Dutch design, trestle-base tables with flat gates appear to be purely English in derivation. (Chinnery illustrates several closely related examples from England that he dates from the mid- to late-seventeenth century, but nothing similar is known in Dutch furniture.)[15] This indicates that unadulterated English joiners’ designs were also popular among New Yorkers and makes the total lack of trestle-base tables with flat gates and New England histories of ownership that much harder to explain.

The Ornamental Elements of New York Tables with Falling Leaves

The turnings on oval tables with falling leaves were meant to harmonize with the sets of cane and leather chairs used with them and with other late seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century furniture forms. During this period joiners and turners in America shared an Anglo-Dutch vocabulary of turned ornament that consisted of compressed or elegantly drawn ogee balusters, flat-topped urns, straight-sided tapered columns, smooth spheres and ellipsoids, rings, reels, and twists. All of these profiles except for the last are evident in an English cane armchair bearing the royal cypher of James II (1685–1688) and his consort Mary Beatrice in its crest (fig. 25). Less elaborately carved but similar high-back chairs were imported by North American colonists, and their turnings served as design sources for local joiners and turners who could copy certain passages verbatim or pick and choose among the various profiles to come up with inventive combinations that satisfied their creative impulses and suited the tastes of their clientele.

In New York, that taste seems to have run toward complexity and exuberance. Furniture historian Benno Forman pointed this out in his study of New York leather chairs. He cited a group of indigenous plain-top, high-back examples that are “rather stiff in their stance” but with “wonderfully elaborate turnings” as proof that, despite the heavy importation of Boston leather chairs, many New Yorkers preferred local variants. On the issue of the relative Dutchness or Englishness of these New York chairs, he was rightfully wary and noted a persistent problem with singling out design influences on early New York furniture. He specifically warned that such influences “could come directly from Holland, or France, or from England which had been influenced by Holland, or from Boston which had been influenced by England, which had been influenced by Holland.”[16] The same problem exists for New York oval tables with falling leaves, although it is possible to identify a precise design source for the turnings on one subgroup of tables with draw-bar supports and possibly for the twisted leg as executed in New York.

Wallace Nutting unknowingly described one distinctive attribute of early baroque turnings in the caption he wrote for #943 in his Furniture Treasury (see fig. 16): “This rare turning or something different from the conventional is usually found with the trestle gate or the flat gate.” By “different from the conventional” Nutting meant different from the bilaterally symmetrical ogee balusters found on many New England tables. New Yorkers showed a more adventurous spirit in the selection and arrangement of the elements used on table legs, opting for variety and visual complexity over symmetry. This quality is manifest in seven patterns of turned legs on the tables illustrated in this article: (1) twist (fig. 13); (2) stacked ogee balusters (figs. 26, 27); (3) large ogee baluster surmounted by a smaller, double-ended, compressed one with a short tapered column above (fig. 28a–c); (4) short urn with a large ogee baluster above (fig. 29a–c); (5) double-ended compressed ogee baluster surmounted by a large, single-ended one (fig. 22); (6) opposed end-to-end ogee balusters (figs. 7, 17); and (7) single elongated baluster (fig. 24).[17]

Certain consistencies among the patterns help to delineate a distinctive New York early baroque turning style. Several tables have flattened ball-shape feet, a well-defined reel on top of the lower leg blocks, and fat, full rings. Also distinctive is a double-ended compressed baluster—sometimes used above a large ogee baluster and sometimes below—that looks a little like an unfinished ball turning. The heavy leg stock and the visual complexity and dynamism of baroque design work hand in glove; the turner can exploit his reductive decorative techniques to the fullest and still maintain axial mass and strength in the legs.[18]

Twisted legs (fig. 13) are a rare feature in American furniture, found on only twenty surviving pieces: five Cromwellian-style leather chairs from Boston and one from Philadelphia or New York; two low-back chairs with board seats and twisted back spindles from Philadelphia; two oval tables with falling leaves, one possibly from New England and one from the South; and nine pieces of New York furniture, including the five tables with draw-bar supports (figs. 11, 12), three high chests, and one dressing table. Legs of this type are frequently said to be twist turned, but this description is something of a misnomer since it incorrectly implies that the twist is imparted in the turning process. The ball-shaped foot, rings and reels, and the essential cylinder are all turned, but the twist is formed with rasps and gouges while the leg blank is at rest in the lathe. There it can be rotated by hand as the artisan works his way around, guided by spiraling layout marks. Bringing a twisted leg to finished smoothness was painstaking work that obviously meant a higher sales price. All the New York examples are single twist, and all the New England, Pennsylvania, and southern examples are double. Benno Forman and Dutch scholar Jan Veenendaal both state that the single twist is more continental European than English; Forman calls the design French, and Veenendaal says that it is Dutch. Either way, it should not be surprising that the single twist only shows up in New York where French Huguenots, French-speaking Walloons, and Netherlandish furniture craftsmen and their customers formed a large segment of the population in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries.[19]

Stacked ogee balusters (fig. 26) are found only on furniture from New York and the South Carolina low country, two areas with sizable populations of French Huguenots. The stacked balusters appear most frequently on trestle-base tables with flat gates (fig. 3) but are rare on those with turned gate legs and tables with draw-bar supports.[20] In all but one instance (fig. 9), the lower baluster in this stacked arrangement is shorter than the upper one, a disposition that contrasts with modern perception that smaller things should be stacked on larger ones but that is in perfect keeping with the tenets of baroque design where the emphasis was on dramatic tension and movement. With this seventeenth-century design principle in mind it is easier to understand a composition in which the lower baluster is consciously made squatter with a shorter neck to give it the appearance of being forced into compression by the pendulous baluster above.

A single baluster surmounted by a compressed double-ended baluster (fig. 28) appears on a group of tables with draw-bar supports made at Kingston in Ulster County (figs. 4, 10, 14). The apparent source for this design was the turned-arm supports on carved-top Boston leather armchairs like the one shown in figure 30 or in New York City versions of the same.[21] It is easy to imagine the genesis of this design occurring when, around 1700, a Kingston-area joiner was commissioned to make an oval table with falling leaves for use with a fine new set of Boston or New York City carved-top leather chairs recently acquired by a local householder. The turning, when expanded to table leg size, takes on an abstract quality visible especially in the center leg in figure 28, where each turned element looks as if it could be snatched from the stacked column of shapes by a deft hand.

Of the four remaining turning patterns, the one most frequently associated with New York—thanks almost exclusively to the renown of the Sir William Johnson table—is the urn and baluster (fig. 29). This pattern is directly traceable to seventeenth-century English oak and walnut oval tables with falling leaves, and it appears as part of the series of turnings on the stiles of the English cane chair shown in figure 25. In American oval tables with falling leaves, it is found in less than robust form on two related mid-eighteenth-century examples from Maine and on a total of five from New York (figs. 15, 18–21).[22] Three distinct variations of the urn and baluster are shown in figure 29. The most notable difference among the three is the lack of the well-defined reel on top of the lower block on the leg of the Sir William Johnson table (fig. 29, far right), a prominent feature of the other two legs. This deletion may indicate a drift away from the design tradition that spawned it. Otherwise, the turnings on the Johnson table are beautifully executed, something that should be expected from a first-rate New York City shop executing a major commission.

The fifth turning pattern—a large ogee baluster over a compressed double-ended one—is represented by the trestle-base table with flat gates illustrated in figure 22. The pattern also occurs on two other tables of the same form and on two walnut tables with box stretchers and turned gate legs probably made in New York City, but it is not found on any of the tables with draw-bar supports. The turning is not exclusive to New York and is found both in surviving architectural woodwork and freestanding furniture from southeastern Massachusetts. An inverted version of this pattern occurs on a curly maple table from Hempstead, Long Island, that has compressed double-ended balusters over the large ogee balusters with the reel that normally sits on top of the lower leg block nestled between them.[23]

Opposed ogee balusters on New York tables—turning pattern number six—have little except their general disposition in common with the rhythmic, bilaterally symmetrical turnings of New England oval tables with falling leaves. Only five New York examples with this leg turning are known, two of which (figs. 7, 17) have multiple fat rings at the top and bottom of the legs but otherwise appear to be unrelated. A trestle-base table at Winterthur (acc. 58.527), one of the few New York examples with turned gate legs, and another closely related table illustrated in Lockwood’s Colonial Furniture in America both have short, fullsome ogee balusters with heavy filleted rings between them. The turnings on figure 17 are similarly configured but have much blunter looking rings that are generally similar to the turned arm supports on a great, plain-top, New York leather armchair at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which Benno Forman believed to be the most thoroughly Dutch of all surviving New York leather chairs.[24]

The seventh and final turning pattern, a simple elongated baluster, is perhaps the least interesting visually (fig. 24). It appears on eight tables, including seven with flat gates, two with turned gates, and one with draw-bar leaf supports. Full-bottomed and drawn out to a columnar form above, the turnings on the table in figure 24 lack the well-defined lower reel, an omission that suggests that it is a fairly late example.[25]

Dating and Attributions to Makers and Locale

Not a single table discussed in this article can be assigned a precise date, place of manufacture, or maker based on signatures, inscriptions, or other documentary evidence. Traditionally, the method used for dating anonymous or poorly documented early baroque oval tables with falling leaves has been by the type of table-leaf joint employed—the tongue-and-groove joint thought to be the earlier form, and the rule joint believed to be the later one. This method was combined with that intangible quality so many collectors, dealers, and students of early furniture use in formulating their final subjective judgments on such matters—aspect. A measure of validity is brought to this dating process if additional “toe holds” are present, such as histories of ownership in a single family or other datable design features. A few New York tables offer such documentation, making dating slightly less subjective at least in a few instances.

One example of this dating method comes from the Johnson table (fig. 15), which has rule joints with short, half-round sections of wood glued at the table ends under the quarter-round section of the joints. This sophisticated conceit, the source of which was probably English, occurs only in New York in American work and appears with greatest frequency on late baroque (fig. 31) and rococo tables with falling leaves and cabriole legs. Another feature relating the Johnson table to late baroque and rococo case furniture made in New York is its drawer construction. (It is difficult to perceive the end drawers in the table’s current condition because the original bail handle drawer pulls, which may have been similar in appearance to the type on the table in figure 31, have been removed and the post holes filled.) The secondary wood in the drawers is yellow poplar; the drawer bottoms are chamfered on all four edges and set into grooves; the top edges of the drawer sides and backs are softly rounded; and there are neat miter joints at the top back corners that echo the fine finish of the rule joints. The sophisticated rule joint and aspects of the drawer construction push the date of manufacture for the Johnson table toward 1750, and the circumstances of Johnson’s life tend to confirm this date as well. Johnson was born in Ireland in 1715 and came to New York in 1738 at the age of twenty-three. Between 1749 and 1763, he built three houses along the Mohawk River, each increasingly grand to suit his growing prominence as an entrepreneur, politician, and royal government official in charge of Indian affairs on New York’s western frontier.[26]

Although the rule joint can be used to shade the Sir William Johnson table toward midcentury, the exact date that this joint was introduced in the colonies is unknown. One of the earliest references to the joint is in the account book of Newbury, Massachussetts, joiner Joseph Brown, Jr., who charged £3 for a “table rule joynted” in 1741. Thirteen years later the joint is mentioned in the day book of New York City joiner Joshua Delaplaine, who charged John Devine £1 for a “bilstel [red gum] Rule Joynt table 3 fot bed [frame].” Rule joints were listed as an option in a 1757 Providence, Rhode Island, table of prices for joiners’ work, which lists: “Maple rule Joynt tables @ £6 Pr foot; old fashen Joynts @ £5.10.”[27] The “old fashen Joynts” probably were tongue-and-groove, and their listing as a less expensive option in 1757 cautions against dating tables by their leaf joints alone.

A second table rich in family tradition is illustrated in figure 18. Inset in the top is a brass plaque that delineates the table’s descent from Catherine Bedloe (bapt. May 22, 1664) of New York City. Bedloe, the daughter of a Dutch merchant, married (n.d.) English merchant Thomas Howarding sometime before 1693, when their daughter Margaret was baptized. She married her second husband, wealthy Dutch New York surgeon Dr. Samuel Staats, in 1707, and the table reportedly descended to her daughter Margaret, perhaps as part of her dowry, when she married Robert Livingston, Jr., in 1717. From Margaret Livingston the table descended through several generations to General Louis Fitzgerald, who inherited it in 1886 and probably was the person responsible for chronicling the history and affixing the plaque. Family histories are notoriously unreliable for dating furniture, but in this instance the survival of an original 1690–1720 backplate for a pendant drop and the tongue-and-groove leaf joints indicate that the table belongs to the generations of Catherine Bedloe or her daughter Margaret Howarding. Also, although it is possible that this style of drawer pull could have been used in the 1730s or 1740s, it is unlikely given the wealth and status of its original owners, who would have wanted hardware as up-to-date as possible.[28]

The original wrought iron hinges (fig. 32) are of a type termed “butterfly” hinge today, but in shop jargon of the period may simply have been called “dovetail.”[29] On several New York tables, the dovetail hinges are fastened by a combination of rosehead nails and a single rivet peened over on both ends. The rosehead nails are short and do not pierce the face of the table top; the rivet also passes only partially through, its countersunk head camouflaged by a face-grain plug (fig. 33). The source of this riveted hinge detail is unknown, but it appears with great regularity on New York tables with pivot legs and draw bars.

A table from the Verplanck family is another example with tongue-and-groove leaf joints that can be dated to the first quarter of the eighteenth century. It and three carved-top Boston leather chairs (fig. 21) were donated to Washington’s Headquarters between 1858 and 1872. In the 1882 Catalogue of Manuscripts and Relics in Washington’s Head-Quarters, they were described as being “the altar furniture of the Reformed Dutch Church at Fishkill, brought from Holland by the Verplanck family in 1682.” Although the Verplancks probably provided the church furniture, the overall design and secondary woods of these pieces indicate that they were made in New York rather than in Holland. Moreover, they are stylistically related and probably were made within a very short time of one another. If so, they are a rare survival, graphically demonstrating the decorative harmony between the turnings on tables and chairs alluded to earlier.[30]

Attributions to makers and locale are similarly handicapped by the lack of documented examples. Logic dictates that some of these tables came from New York City shops, particularly those made of mahogany and black walnut, woods that had to be imported from the South. The tables made of these expensive woods appear to be the work of several different shops. Those illustrated in figures 15 and 20 and those in 18 and 19 represent the work of two different New York City shops because of their closely related turnings and because of the sophisticated rule joints on the former pair and the original use of oak pegs for the mortise-and-tenon joints on the latter pair. It is also conceivable that the Van Cortlandt family table (fig. 2) represents an earlier generation of the shop tradition that spawned the Johnson table (fig. 15).

New York City furniture tradesmen in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries had northern European and English names. Joiners (the tradesmen responsible for these tables) who were active between 1695 and 1727 included John Le Chevalier, Edward Hunt, Robert and Peter White, Edward Burling, Joshua Delaplaine, James and Daniel Gautier, John Kinder, Joseph Kingston, Thomas Grigg, Andrew Brested, Thomas and Jonathan Gleaves, Joseph Diviat, John Sibley, and Richard Berry. The account books of Joshua Delaplaine reveal that he made tables throughout his career (fl. 1718–ca. 1771). In a series of six separate transactions between 1721 and 1727, Delaplaine made tables ranging in value from 15s. to £1.11.0 in exchange for tools, hardware, fabrics, and other sundries that he acquired from Edward Burling, a Quaker joiner who became a freeman in 1683 and probably worked until his death in 1753. Burling undoubtedly resold the tables, all of which were probably made in the early baroque style. In 1753 Delaplaine made “a mahogany Dining table 5 foot 3 In. bed, 8 legs, 2 draws” for Elias Desbrosses and charged him £8.10.0. This table, on the other hand, could have resembled the relatively late Johnson table (fig. 15) or the eight-legged table shown in figure 31, or it could even have had modish new cabriole legs with ball-and-claw feet. Like Burling, Delaplaine was a Quaker. He took at least one Quaker apprentice (his first), Francis Warne. His business relationships with Friends extended well beyond New York, for he entered into a sales arrangement for two desks and a tea table with Newport cabinetmaker Christopher Townsend in 1745. Little attention has been given to the Quaker strain in New York furniture, but there is something about the precision and obsessive attention to detail in features like the barrel-shaped rule joint and the mitred top back corners of the drawers in the Johnson table and other eighteenth-century New York City case furniture that, though having no direct relationship to the furniture of Newport Quakers, is reminiscent of the quality and level of refinement apparent in John Townsend’s labeled work. Burling, Delaplaine, and the many apprentices they trained could have been responsible for high-quality New York City furniture of this sort, and they were tradesmen worthy of greater scrutiny than that applied in this study.[31]

If the Johnson table possibly represents an Anglo-Quaker strain, the tables with draw-bar leaf supports, especially the walnut and red gum examples illustrated in figures 11 and 12, are more indicative of a northern European tradition. The walnut table is almost certainly city made, and the other table, although made of red gum, probably qualifies for the same distinction. The Delaplaine account books show that “bilsted” or red gum was a common commodity in New York City. What really sets the red gum table apart as the mature product of a talented urban craftsman are its well planned and excellently proportioned legs, which taper slightly in thickness from the bottom to the top (fig. 13).

Beginning around 1700, the draw-bar version of the early baroque oval table with falling leaves found expression in the Kingston area (Ulster County) of the Hudson River Valley—the only locale that has yielded enough related tables with histories to allow the identification of a distinct school outside of New York City. Of the eight tables attributed to this area, six have turnings derived from the arm supports of Boston and New York City carved-top leather chairs of the late 1690s and early 1700s (figs. 4, 10, 14) and the other two have cone-like, stubby columns at the top—details characteristic of the Ulster County school. One of the tables with twisted legs and a tradition of ownership in the Elmendorf family of Hurley (just outside of Kingston) could also be locally made given its history and the presence of these same short, tapered columns at the top of its rather horsey-looking, single-twist legs.[32]

The dominant shop tradition for the Ulster County region centered at Kingston and was presided over for generations by the Beekman and Elting families, beginning with Jan Elting (1632–1729) in 1672 and continuing into the nineteenth century with Thomas Beekman (1761–1814). The Elting-Beekman joiners made kasten of a consistent design for their principally Dutch and Huguenot customers from at least 1700 until after the Revolution, and evidence suggests they produced early baroque oval tables with falling leaves as well. The ogee moldings on the rails and stretchers of the tables match those used in the central sections of the massive kast cornices, and on the draw-bar table illustrated in figure 10, the end drawers are constructed (except for the lack of channeled sides) like those in the kasten (fig. 34).[33]

The working dates of the Elting-Beekman shop (fl. ca. 1672–1814) and the persistence of early baroque designs in Ulster County suggest that some of these eight tables may be earlier than others. Of the three tables included in this article (figs. 4, 10, 14), only the one illustrated in figure 14 has rule joints, and it appears to be the latest. This table also differs from the other two in having rails and stretchers with edge beading similar to the quirk and bead moldings found on late-eighteenth-century interior woodwork rather than ogee moldings. Its large baluster turnings are slightly drawn out at the neck and look a little flacid in comparison to those on the other two tables (figs. 4, 10). Aspect alone suggests that the table shown in figure 4 is the earliest. The legs are stouter (measuring 2 3/4" square), the baluster is full and strongly compressed, and the reel element is slightly taller than on either of the other Ulster County tables. In the end, however, it probably matters little which table predates the other. What these tables gloriously represent is a taste for bold, early baroque design, nurtured by a conservative, non-Anglo society throughout a century when many other New Yorkers successively embraced the late baroque, rococo, and early neoclassical styles. The table illustrated in figure 10 probably dates to the mid 1700s and is a wonderfully appealing object expressive of the culture that produced it. This object can stand on its own aesthetic merits regardless of the date it was made.

New York early baroque furniture has its admirers, many of whom believe that it is bolder in outline and more vigorous and diverse in its turned ornament than contemporary New England work. The early baroque New York oval tables with falling leaves examined here will strengthen this conviction for some and might even win a few converts. More importantly, however, they provide, in the absence of written documents, the only record of the form’s development in New York. Tables of purely English design with turned and flat gates reveal that some New Yorkers looked to England and Boston for the latest furniture forms and fashions. These New Yorkers would at first have been primarily of English extraction, or were non-Anglos who stood to gain from outward displays of allegiance to their new rulers. Conversely, the tables with draw bars suggest that there was a significant segment of New York society intrigued by English fashion but still reluctant to abandon completely their traditional European furniture forms and design aesthetic. The draw-bar table probably fell out of favor in New York City by 1740 as English culture became dominant, but it remained popular among the conservative, non-Anglo population of Ulster County, where it fell comfortably into the rhythm of rural life until the time of the Revolution. This is what places the form squarely in the canon of objects described as New York Dutch material culture. Included in this canon is the kast, which, it can be argued, is quintessentially Dutch. The draw-bar table, on the other hand, is not. Instead it is a wonderful hybrid that physically manifests Anglo-Dutch cultural blending in early colonial New York.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the following individuals for their kind assistance in the preparation of this article: Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, Frank Cowan, Constance and Dudley Godfrey, Roger Gonzalez, Rich Goring, Tammis Groft, John Hays, Bill Hosley, Tom Hughes, Kate Johnson, Mel Johnson, Leslie Stratton-Le Fevre, Bill Lohrman, Johanna McBrien, Alan Miller, Bill Orser, Jonathan Prown, Frances Safford, Bob Slater, Robert Trent, Anne and Fred Vogel, Deborah Waters, Jack and Mary Ellen Whistance, and Martin Wunsch

.

David L. Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992), p. 118.

Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1979), pp. 301–3.

Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses, p. 118. Gerald W. R. Ward, “The Intersections of Life, Tables and Their Social Role,” in Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses, pp. 21–24. For the importance of the oval shape in baroque architecture and decoration, see Phillip M. Johnston, “The William and Mary Style in America,” in Reinier Baarsen et al., Courts and Colonies, The William and Mary Style in Holland, England, and America (New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1988), pp. 72–74.

Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses, p. 118, states that oval tables with falling leaves “can usually be distinguished from smaller tables with stationary oval tops by their value and the presence of large sets of chairs used with them.”

Two heavy rectangular tables, one with a trestle base and the other with a stretcher base, both possibly from New York, are illustrated in Dean F. Failey, Long Island is My Nation, the Decorative Arts and Craftsmen, 1640–1830 (Setauket, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1976), p. 27. The Dutch draw table in figure 1 and a second one illustrated in “In the Museums,” Antiques 71, no. 1 (January 1957): 68, are the only two known examples of this form believed to have been made or used in New York. Michael Kammen, Colonial New York (Millwood, N.Y.: KTO Press, 1978), pp. 73–74, 91. Kammen cites population figures as follows: in 1665, 1,470 persons (of 254 listed for taxation, only 16 had English surnames); by 1676, the city had grown to more than 2,200 persons (of 302 taxables, 115 seem to have been English).

Cornelis Steenwyck Inventory, July 29, 1686, New York State Court of Appeals, New York State Archives, Cultural Education Center, Albany. This collection has been microfilmed and is abstracted in Kenneth Scott and James A. Owre, Genealogical Data from Inventories of New York Estates 1666–1825 (New York: New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, 1970). The Phillipse family table is at the Old Dutch Church, North Tarrytown, New York, where it is still in use by the congregation. The January 7, 1730, will of Catherine Phillipse (1652–1730) of New York City reads: “I give and bequeath to my Son in Law Adolph Phillipse Esq. & to his heirs for Ever . . . a Long table In Trust to and for the Congregation of the Dutch Church Erected at Phillipseburgh by my late Husband Frederick Phillipse decd” (typescript copy, files of the Old Dutch Church). For the Schuyler inventory, see Ruth Piwonka, “New York Colonial Inventories: Dutch Interiors as a Measure of Cultural Change,” in Roderic H. Blackburn and Nancy A. Kelly, eds., New World Dutch Studies: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America 1609–1776 (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), p. 73. Piwonka gives the best and most succinct summary of the problems and opportunities presented by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New York estate inventories, as well as a sampling of the few room-by-room ones available.

Cited in Roderic H. Blackburn and Ruth Piwonka, Remembrance of Patria: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, 1609–1776 (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1988), p. 186.

Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition, p. 301, figs. 3: 202, 3: 211, 3: 213. The supporting rails on draw tables also run in tracks but differ from lopers in that they are fixed to the undersides of the leaves and taper in length (the thinnest part of the taper toward the ends of the table, the thickest toward the center). This taper causes the leaves to rise to the height of the fixed center section of the top as they are drawn out from under it.

Something analogous to this occurs in late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century New York tankards, which are an English form but have cut-card banding and meander ornaments that are more typically Dutch grafted onto them. For a discussion of the New York tankard as an Anglo-Dutch hybrid, see Gerald W. R. Ward, “The Dutch and English Traditions in American Silver,” in Francis J. Puig and Michael Conforti, eds., The American Craftsman and the European Tradition, 1620–1820 (Hanover, N.H.: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1989), p. 139. The ovolo-and-bead molding and the kasten on which it is found are illustrated and discussed in Peter M. Kenny, Frances Gruber Safford, and Gilbert T. Vincent, American Kasten: The Dutch-Style Cupboards of New York and New Jersey, 1650–1800 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), pp. 12, 36–43.

A table with apron construction similar to the example shown in figure 11, but that appears to be the work of a different shop, is illustrated in Blackburn and Piwonka, Remembrance of Patria, p. 174. The remaining two tables with twisted legs, one with a history of ownership in the Elmendorf family of Hurley in Ulster County, New York, and the other originally owned in the Van Bergen, Bronck, or Houghtaling families of Greene County, New York, have half-inch-thick rectangular plaques nailed on the corners that obscure the apron joints. These appear to be an original treatment, perhaps intended to give the tables a stronger, more joinerly appearance. The Elmendorf table is illustrated in Antiques 83, no. 6 (August 1963): 165, where the applied corner plaque is barely visible behind one of the table leaves. This table is still in the possession of descendants of its original owner, as is the one with the Greene County history that has never been illustrated. These two tables probably come from the same shop.

Robert Trent suggests that broad central frames on oval tables with falling leaves may be an early feature that points to the genesis of the form when leaves were attached to massive rectangular tables of traditional style. For Trent’s comments, see American Furniture with Related Decorative Arts, 1630–1830: The Milwaukee Art Museum and The Layton Art Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1991), pp. 83–84. A square table with plain stretchers is also illustrated in the Milwaukee catalogue on p. 41. (Several others survive, including examples in the Nutting collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Historical Society of Old Newbury, Newburyport, Massachusetts.) In the Milwaukee catalogue, Trent argues that the Milwaukee and the Metropolitan Museum square tables, both being made of maple, may date as late as 1710. The possibility has yet to be considered that any of these could have been made in New York.

The Van Cortlandt family table and the Sir William Johnson table are illustrated and discussed in Esther Singleton, The Furniture of Our Forefathers (New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1900), pp. 256–60. The Johnson table is also in Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols. (2d ed., New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921), 2:174–75. Wallace Nutting, Wallace Nutting General Catalog, Supreme Edition (1930; reprint, Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Limited, 1977) p. 104. The table at the Monmouth County Historical Association, an exceptionally small example, is illustrated in Antiques 118, no. 1 (January 1980): 180.

Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2:179–80. Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury (Framingham, Mass.: Old America Company, 1928), nos. 942, 943. For additional illustrations of tables with flat gates, see Norman F. Rice, New York Furniture Before 1840 (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1962), p. 37; Robert Bishop, American Furniture1620–1720 (Dearborn, Mich.: Edison Institute, 1975), p. 10; Charles T. Lyle and Philip D. Zimmerman, “Furniture of the Monmouth County Historical Association,” Antiques 118, no. 1 (January 1980): 186; Charles T. Lyle, “Buildings of the Monmouth County Historical Association,” Antiques 118, no. 1 (January 1980): 184 (the four-legged table with flat gates shown here is now in a private collection); and Failey, Long Island is My Nation, p. 28. A few trestle-base tables with turned gate legs and low flat stretchers are known. One that was owned by Miss C. M. Travers of New York is illustrated in Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2:179. Another closely related example attributed to New York is at Winterthur (acc. 58.527). A “flat gate” with a trestle base said to have descended in some Norwalk, Connecticut, families was sold at Sotheby’s, Fine American Furniture, Folk Art, Folk Paintings and Silver, June 26, 1986, sale no. 5473, lot 112.

Piwonka, “New York Colonial Inventories,” pp. 74–76. Like Cornelis Steenwyck, Van Cortlandt appears to have preferred not to use an oval table with falling leaves in her front parlor or best room. The large oak table in this room may have been a considerably older one with an expandable draw top since there were eighteen “chairs” and one “elbo cain chair” in the room. The inventory is salted with references to “old” objects, the most interesting one being the “old Holland case” in the chamber over the back parlor. Apparently, Gertruy Van Cortlandt maintained a “Dutch” household to the very end. For an informative analysis and reconstruction of Dutch townhouses in The Netherlands and colonial New York based on period documents, see Henk J. Zantkuyl, “The Netherlands Town House: How and Why It Works,” in Blackburn and Kelly, eds., New World Dutch Studies, pp. 143–60.

Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition, pp. 306–7.

Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture 1630–1730 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988), p. 292.

A few New York oval tables with falling leaves exist with unique turnings, and more undoubtedly will surface in the future. The purpose of organizing the turning patterns into visually cohesive groups is to aid the reader in making comparisons and in discerning a distinct early baroque New York turning style.

Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 290. Forman was the first to identify fat, full rings as a characteristic of New York early baroque turning on high-back leather chairs. The extra turned foot under the inner pivot leg of the auxiliary leg support, a typical New England feature, is seldom used.

Robert F. Trent, “17th-Century Upholstery in Massachussetts,” in Edward S. Cooke, Jr., ed., Upholstery in America & Europe from the Seventeenth Century to World War I (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987), p. 44, fig. 22. The Philadelphia board-seated chairs and the Philadelphia or New York leather chair are illustrated in Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 220–23. The two tables of possible New England origin are illustrated in Singleton, The Furniture of Our Forefathers, 1:200; and in Frances Clary Morse, Furniture of the Olden Time (New York: MacMillan Company, 1902), p. 220. The southern table is illustrated in Antiques 61, no. 1 (January 1952): 59. For the New York high chests, see Philip M. Johnston, “The William and Mary Style in America,” in Courts and Colonies, p. 64; John T. Kirk, American Furniture and the British Tradition (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982), p. 190; and Joseph Downs and Ruth Ralston, A Loan Exhibition of New York State Furniture (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1934), no. 34. The dressing table is in a private collection. The entire process from layout to finishing for both single- and double-twisted legs is clearly explained in “Twist Turning, Traditional Method Combines Lathe and Carving,” Fine Woodworking 33 (March/April 1982): 92–95. For the continental European background of the single twist, see Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 220; and Jan Veenendaal, Furniture from Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India During the Dutch Period, trans. by R. Robson-McKillop (Delft: Volkenkundig Museum Nusantara, ca. 1985), p. 31.

For coastal South Carolina furniture with stacked baluster turnings, see E. Milby Burton, Charleston Furniture, 1700–1825 (Charleston: Charleston Museum, 1955), fig. 76 (a 1710–1720 stretcher table from Limrick plantation); and MESDA research file S-1273 (a 1710–1725 couch). The author thanks Luke Beckerdite for these references. The only table with turned gate legs that has stacked balusters is the Van Cortlandt family table (fig. 2). Two draw-bar tables with this turning are known: figure 9 and a table (private collection) once owned by the Knickerbacker family (phone conversation with Roderick Blackburn, January 1992).

For an armchair attributed to New York with the same turning under the arm, see Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 288.

The Maine tables are illustrated and discussed in Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1984), pp. 270–71.

The trestle-base tables with this leg turning include one that descended in the Butler and Chichester families of Norwalk, Connecticut (Sotheby’s Fine American Furniture, Folk Art, Folk Paintings and Silver, sale no. 5473, lot 112) and another advertised by Fred J. Johnston in Maine Antiques Digest, August 1990. One of the walnut tables with turned gate legs was sold at Sotheby’s American Heritage Auction of Americana, January 30, 1982, sale no. 4785Y, lot no. 783 and subsequently offered for sale by John Walton, Inc., in Maine Antiques Digest, May 1983. The other is at the Van Cortlandt Mansion in Van Cortlandt Park, New York. Details of turned staircase balusters and a table leg from South Scituate and Marshfield, Massachusetts, are illustrated in Robert Blair St. George, The Wrought Covenant (Brockton, Mass.: Brockton Art Center/Fuller Memorial, 1979), pp. 41–42. For the Hempstead, Long Island, table, see Failey, Long Island is My Nation, p. 30.

The leather armchair is illustrated in Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 290. For the trestle-base table related to the Winterthur example, see Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2:179. For the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, armchair and a discussion of opposed ogee baluster arm supports in New York leather chairs, see Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 289–90. The fourth New York trestle-base table with opposed baluster turnings is in the collection of the Monmouth County Historical Association in Freehold, New Jersey, and on display at Marlpit Hall in Middletown. This table also has a full fat ring as a linking device between the balusters.

In addition to the trestle-base table with the elongated balusters illustrated here (fig. 24), other examples are illustrated in Lyle and Zimmerman, “Furniture of the Monmouth County Historical Association,” p. 186; and in a Joseph Sprain advertisement in Antiques 106, no. 2 (August 1974): 161. The two classic “gate-legs” are illustrated in Thomas Smith Hopkins and Walter Scott Cox, Colonial Furniture of West New Jersey (Haddonfield, N.J.: Historical Society of Haddonfield, 1936), pp. 32–33 (it’s possible that it is a Philadelphia table), and in Christie’s Important American Furniture, Silver and Decorative Arts, June 2, 1983, sale no. 5370, lot 366. A fifth “flat gate” with four legs and low plain board stretchers is illustrated in situ in the Allen house, Shrewsberry, New Jersey, in Lyle, “Buildings of the Monmouth County Historical Society,” p. 184. The table with draw-bar supports was owned by Roger Gonzalez and Frank Cowan in 1994 as were two additional flat-gate tables with stretchers and elongated-baluster legs.

An English pad-foot dining table with falling leaves and additional half-rounds glued beneath the rule joints is shown in John T. Kirk, American Furniture and the British Tradition to 1830, p. 324. The drawer’s softly rounded top edges and mitered back corner joints are details that also appear on a New York City mahogany chest of drawers in the rococo style at the Brooklyn Museum (acc. 55.225) and on a fine New York City mahogany desk-and-bookcase in the same style at Winterthur, illustrated in Joseph Downs, American Furniture, Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (New York: MacMillan Company, 1952), p. 224. I am grateful to Wade Lawrence for information on the Brooklyn Museum and Winterthur case furniture. For information on Sir William Johnson and his homes, see Kammen, Colonial New York, pp. 308–15, and Dumas Malone, ed., Dictionary of American Biography, 11 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1961), 5:124–28.

Susan Mackiewicz, “Woodworking Traditions in Newbury Massachussetts, 1635–1745,” M.A. thesis, University of Delaware, 1981. J. Stewart Johnson, “New York Cabinetmaking Prior to the Revolution,” M.A. thesis, University of Delaware, 1964, p. 87. The full table of prices is given in Irving W. Lyon, The Colonial Furniture of New England (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1891), pp. 265–66.

Museum of the City of New York, file for acc. 78.106.

The accounts between Joshua Delaplaine and Edward Burling list the purchase of numerous tools and hardware, including entries in 1730 and 1738 for dozens of “dovetails.” For the Delaplaine and Burling accounts, see Johnson, “New York Cabinetmaking Prior to the Revolution,” appendix F.

E. M. Ruttenber, Catalogue of Manuscripts and Relics in Washington’s Head-Quarters, New Burgh, N.Y., With Historical Sketch (Newburgh, N.Y.: E. M. Ruttenber & Son, 1882), no. 616. The 1882 catalogue was based on an 1872 inventory of the contents of the house. A catalogue dated 1858, in the archives of Washington’s Headquarters, lists the chairs but not the table. The author thanks Tom Hughes and Mel Johnson of Washington’s Headquarters for these references. Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 311. Forman dates Boston carved-top leather chairs no later than 1723 based on the account books and letters of Boston upholsterer Thomas Fitch. The gift of the Dutch draw table (fig. 1) to the Dutch Reformed Church after it was used for a couple of generations by the Phillipse family is a pattern that may also hold true for the Verplanck table and chairs.

The names of these joiners are taken from The Burghers of New Amsterdam and the Freemen of New York 1675–1866, in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1885 (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1886); and Indentures of Apprentices 1718–1727, in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1909 (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1910). Johnson, “New York Cabinetmaking Prior to the Revolution,” appendices E–L and pp. 17–19.

In addition to the three Ulster County tables illustrated here, there are also examples with the same turning at the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee, Winterthur Museum (acc. 58.1028), and Senate House State Historic Site in Kingston, New York (acc. SH 1975.321). The Winterthur table reportedly descended in the Depuy-Schoonmaker family of Stone Ridge, Ulster County (phone conversation with Bob Slater of Fred J. Johnston Antiques [the firm that sold the table to H. F. du Pont], May 1989). The turnings on the sixth table (private collection, Kingston, N.Y.) feature well-defined reels surmounted by elongated balusters with short tapered columns above. This table was once the property of artist and designer Ivar Evers of New Paltz, and, like the table shown in figure 10, its short tapered columns are slightly convex, a reference to classically correct entasis. The seventh table has turnings comprised of a series of three compressed balusters surmounted by straight-sided, short tapered columns. This table, which was sold at the Copake Country Auction in 1986 (Antiques and the Arts Weekly, August 15, 1986), does not have a local Ulster County history, but its turnings are nearly identical to those on a desk-on-frame from the Kingston area illustrated in Blackburn and Piwonka, Remembrance of Patria, p. 178. The Elmendorf family table with twisted legs is illustrated in Antiques 83, no. 6 (August 1963): 165.

For more on the Elting-Beekman group of makers, see Kenny, Safford, and Vincent, American Kasten, pp. 23–26, 54–59.