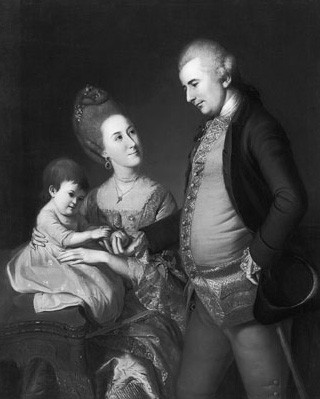

Charles Wilson Peale, Portrait of John and Elizabeth Lloyd Cadwalader and their daughter, Anne. Oil on canvas, 51 1/2" x 41 1/4". Courtesy: Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.

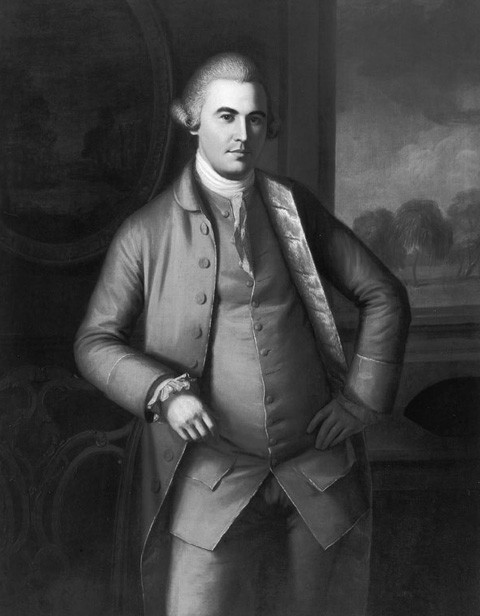

Charles Wilson Peale, Portrait of Colonel Lambert Cadwalader. Oil on canvas, 51" x 41". Courtesy: Philadelphia Mueseum of Art. Purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983

Side chair, Philadelphia, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 36 3/4", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 177/8" (seat). (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

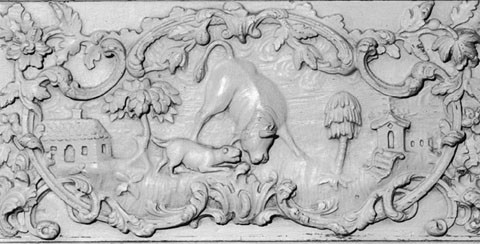

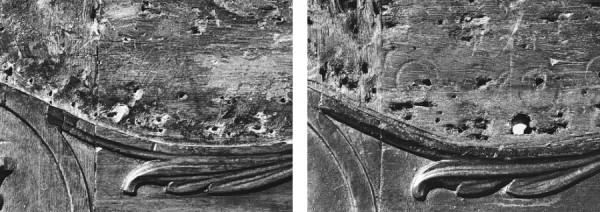

Detail of the carving on the front rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 3.

Side chair, Philadelphia, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 37 1/16", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 18" (seat). (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the carving on the front rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 5. The tradesmen who made the chairs in this set used a combination of planes, chisels, files, and scrapers to prepare the upholstery surfaces on the front and side rails. Because the front rails are serpentine, they used a curved toothing plane to finish the area for the foundation upholstery (approx. 1"– 11/4" at the top) and chisels, files, and scrapers to prepare the surface below. On the side rails, they used a standard smoothing plane to finish the area for the foundation upholstery and chisels, files, and scrapers below.

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 3.

Side chair with the label of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 38 3/8", W. 23 3/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, M. and M. Karolick Collection, © 2000, all rights reserved.)

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 8.

View of the Stamper-Blackwell parlor. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

View of the Ringgold parlor. (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art.) The Ringgold house was one of two residences on Maryland’s eastern shore with architectural carving imported from Philadelphia. The other is Cloverfields in Queen Anne’s County. Philadelphia carvers shipped architectural carving as far south as Charleston, South Carolina.

Detail of the center tablet on the chimneypiece in the Stamper-Blackwell parlor. The scrolls and leaves framing the central scene are taken from the tablet design illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of one of the frieze appliqués on the chimneypiece in the Ringgold parlor. This frieze appliqué is based on the design shown in fig. 15, but it is inverted.

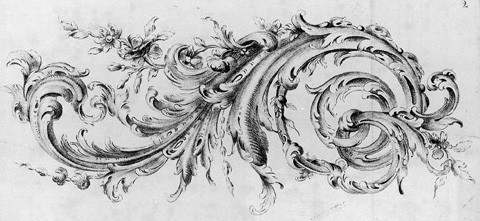

Design for a tablet illustrated in Thomas Johnson, A New Book of Ornaments (1762). The only complete copy of this publication is in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It consists of six patterns “Designed for Tablets & Friezes for Chimney-Pieces.”

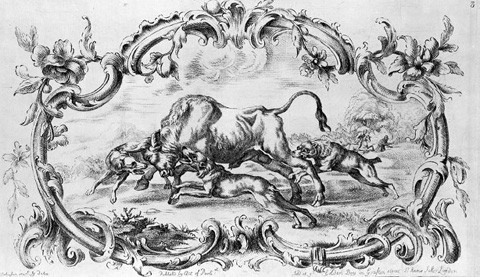

Design for a frieze illustrated in Thomas Johnson, A New Book of Ornaments (1762).

Detail of the acanthus carving on the left stile of the side chair shown in fig. 3.

Pier table, Philadelphia, 1765–1769. Mahogany with yellow pine; marble. H. 32 3/8", W. 48", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918 (18.110.27) Photograph © 1991 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.) Two large scrolls are missing from the lower edge of the table.

Detail of the carved figure in the center of the table illustrated in fig. 17. (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918 (18.110.27) Photograph © 1991 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

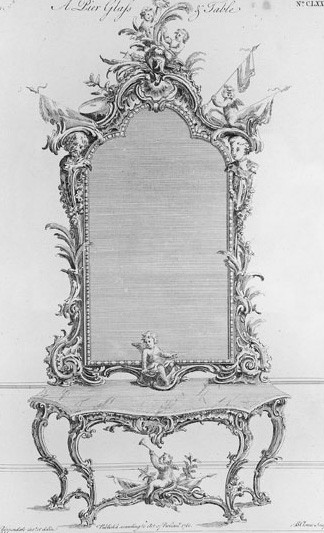

Design for a pier glass and table illustrated on pl. 152 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair attributed to Thomas Affleck, Philadelphia, 1771. Mahogany with yellow pine, white oak, white cedar, black walnut, and tulip poplar. H. 45". (Courtesy, Dietrich Americana Foundation.) The carving on this chair is attributed to the shop of Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez

Detail of one of the webbing sites on the seat rails of the chair illustrated in fig. 3. Each site is indicated by a cluster of nail holes approximately 1 7/8" wide.

Detail of the right leg of the chair illustrated in fig. 3, showing file marks from the removal of the upholstery peak. The peaks on the commode-seat chairs were approximately 1/2" high.

Detail of the front seat rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 5, showing nailing patterns for securing the (a) upholstery roll and (b) top canvas.

Ultraviolet photograph showing the front rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 5. The area covered by the foundation upholstery flouresces differently from that covered by finish.

Ultraviolet photograph showing the front rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 3. The area of the seat rail covered by the foundation upholstery flouresces differently from that covered by finish.

Side chair, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 41 1/2", W. 27", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the front seat rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 26. The area covered by the foundation upholstery flouresces differently from that covered by finish.

Detail showing two of the six spoon bit holes used for tying on the slipcover of the chair shown in fig. 5.

Detail showing how the slipcovers of the commode-seat chairs would have been tied off.

Detail of the nailing line for fixed upholstery on the front rail of (left) the chair illustrated in fig. 3 and (right) the chair illustrated in fig. 5.

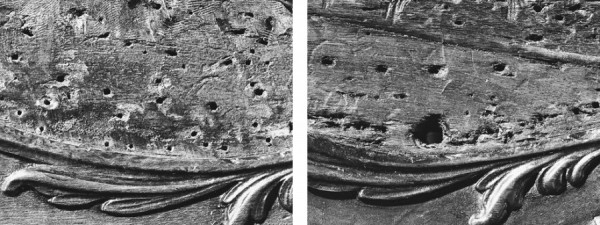

Detail of the nailing line for fixed upholstery on the side rail of (left) the chair illustrated in fig. 3 and (right) the chair illustrated in fig. 5.

Detail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 5 showing how the fringe of a reused slipcover would have been nailed to the side rail.

Detail of the tacking evidence adjacent to the carved strapwork on the rails of the seat of the side chair illustrated in fig. 5.

Few pieces of American furniture have received as much attention and acclaim as the commode-seat rococo side chairs commissioned by Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader and his wife Elizabeth (Lloyd) (fig. 1). Only seven chairs from the set are known, but there may have been between sixteen and twenty originally. They appear to have been completed by September 1, 1770, when Charles Willson Peale received payment in full for portraits of John Cadwalader’s brother Lambert (fig. 2) and parents Thomas and Hannah.[1]

The chair illustrated in figure 3 may be the one depicted in Peale’s portrait of Lambert Cadwalader. The underside of the shoe is numbered “I,” and the carving on the back and seat rails (fig. 4) is more detailed and more carefully rendered than that on the other surviving chairs (figs. 5, 6). This disparity suggests that the chair shown in figure 3 may have been submitted for approval before work began on the remainder of the set. Because its carved details and upholstery evidence are clear and relatively unambiguous, this chair serves as a benchmark for reexamining aspects of the set’s manufacture, upholstery, and context.[2]

In 1927, furniture historian Samuel W. Woodhouse published one of the commode side chairs and attributed it to Philadelphia cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph. Since then, scholars have pointed to cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck and carvers Hercules Courtenay, John Pollard, Nicholas Bernard, and Martin Jugiez as possible makers. Most of these later attributions have cited bills, waste book entries, and inventories pertaining to Cadwalader’s house and furnishings, but few have reconciled these documents with the physical evidence on the chairs.[3]

The production of elaborate sets or suites of furniture required a great deal of cooperation between the patron and maker. Although John and Elizabeth probably approved drawings of the chairs, Lambert may have assumed responsibility for the completion of the set. During the fall of 1769, he supervised work on John and Elizabeth’s townhouse while the couple attended to her ailing father in Maryland. John’s waste book notes that he reimbursed Lambert £94.15 for “B. Randolph[’s] acct for Furniture” and £30 for “2 marble Slabs etc. had of C. Coxe.” It is impossible to attribute the chairs to Randolph’s shop based solely on the £94.15 entry, but that sum would have been sufficient for a large set.[4]

Circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that the chairs are products of Randolph’s shop. The acanthus leaves on the rails and knees (see figs. 4, 7) are by the same hand that carved two side chairs with Randolph’s label (figs. 8, 9). The carving on the Cadwalader chairs is also related to architectural work from the parlors of the Stamper-Blackwell house in Philadelphia (now installed in the Winterthur Museum) (fig. 10) and the Thomas Ringgold house in Chestertown, Maryland (now installed in the Baltimore Museum of Art) (fig. 11). These interiors feature details (figs. 12, 13) taken from Thomas Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments (1762) (figs. 14, 15). Philadelphia carvers Hercules Courtenay and John Pollard probably introduced these rococo designs. Courtenay apprenticed with Johnson before immigrating to the colonies in 1765. He began his Philadelphia career as an indentured tradesman in Randolph’s shop, where he worked with London-trained carver John Pollard. Courtenay established his own shop by the summer of 1769. On September 17, 1770, he billed John Cadwalader £81.2.1 for architectural carving, including a “Tablet the Judgement of Hercules” valued at £8.10.[5]

Pollard was the principal carver in Randolph’s shop during the late 1760s and early 1770s. As such, he probably supervised several apprentices and journeymen. Because the ornament on the chairs differs significantly from work attributed to Courtenay and the other major carvers active in Philadelphia during the period, Pollard and his associates in Randolph’s workforce are the most likely candidates as carvers of Cadwalader’s commode-seat chairs. The chairs clearly represent the work of at least two carvers. In accordance with accepted eighteenth-century practice, the most accomplished tradesman worked on the stiles, crest, and back—the components nearest the eye.[6]

The carving on the backs of the chairs is most like that on the tablets and frieze appliqués in the Stamper-Blackwell and Ringgold parlors. All of these designs feature acanthus leaves with intricately curled tips and deeply modeled surfaces (see figs. 12, 13, 16). The foliage on the tablets and leaves below the central husk on the crests of the chairs rank among the finest American carving in the rococo style. The only Philadelphia carving that surpasses this work is on a pier table attributed to Pollard (fig. 17). This table, which also belonged to Cadwalader, may be one of the “2 marble Slabs etc.” that Lambert purchased from Charles Coxe for £30 in 1769. Like the architectural carving, the table has details (fig. 18) taken from British design books (fig. 19), specifically the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762). Randolph and his tradesmen undoubtedly had access to a copy. His trade card includes imagery borrowed from the Director, and Randolph was a member of the Library Company of Philadelphia, which owned a copy of the third edition by 1769. However, the overt British design of the table, architectural carving, and commode-seat chairs suggests that they reflect the imagination of an immigrant tradesman such as Pollard rather than a native-born entrepreneur such as Randolph. The latter was a lumber merchant before his investment in a successful privateering venture enabled him to hire the workforce for a cabinet shop.[7]

Cadwalader’s commode-seat chairs were the genesis of an elaborate suite of furniture made for the townhouse he and his wife purchased from Samuel Rhodes in 1769. At the time of their marriage in 1768, Elizabeth Lloyd’s personal wealth exceeded £11,000. A cash advance of £2,500 made by her father, Edward III, allowed the couple to purchase the townhouse and begin converting it into what one observer called “a grand and elegant” residence. Cadwalader made over £374 in unspecified payments to house joiner Thomas Nevell, which suggests that Nevell made and installed new architectural components throughout the house. The Cadwaladers’ residence also contained over £360 worth of architectural carving, including a variety of moldings, trusses, architrave flowers, frieze appliqués, and sculptural busts and tablets. Among the carvers who worked on this project were Hercules Courtenay, Nicholas Bernard, Martin Jugiez, and, in all probability, John Pollard. Randolph’s shop had the largest account, providing £252.16.1 worth of carving.[8]

Several pieces of furniture made by Thomas Affleck and carved by James Reynolds and by the firm of Bernard and Jugiez were designed to be en suite with Cadwalader’s commode-seat chairs. Between October 13, 1770, and January 14, 1771, Affleck’s shop made over eighteen pieces of furniture for Cadwalader. Included were two mahogany commode sofas “for the Recesses” valued at £16, “one Large ditto” valued at £10, “an Easy Chair to Sute ditto” valued at £4.10 (fig. 20), two commode card tables valued at £10, and four firescreens valued at £10. During the same time frame, Reynolds and Bernard and Jugiez were also occupied with other commissions from Cadwalader. In October 1770, Bernard and Jugiez billed Cadwalader £28.10.71/2 for architectural carving. Three months later, Reynolds charged him £140.18.1 for several large carved and gilded looking glasses, picture frames, and 539 yards of papiér-maché borders described as “Palmyra Scrowl” and “Leaf & Reed.”[9]

The commode-seat chairs were clearly part of a unified decorative scheme that included the suite made by Affleck and that extended to the architectural carving and fabrics used in each of Cadwalader’s principal rooms. Bills pertaining to the textile furnishings in Cadwalader’s house shed light on the probable number, upholstery, and placement of the commode-seat chairs. On October 18, 1770, Philadelphia upholsterer Plunkett Fleeson charged Cadwalader £13.13 for “covering 32 chairs over rail finish’d in canvis.” The following January, the upholsterer made seventy-six Saxon blue French check cases with blue and white fringe for these chairs and others that Cadwalader had either purchased or inherited from his father-in-law. The commode-seat chairs were subsequently fitted with covers made of blue and yellow silk damask that Cadwalader ordered from London merchants Rushton & Beachcroft. In January 1772, Philadelphia upholsterer John Webster billed Cadwalader £18.7.10 for making the curtains for four windows and for upholstering twenty chairs and three sofas with these fabrics. A subsequent entry in Cadwalader’s waste book provides additional information on Webster’s work, noting that the payment was for “Curtains in [the] front & back Rooms, Covers to Settees & Covers to Chairs in front & back Rooms.” The curtains and covers in the front room were blue and the ones in the back parlor were yellow to match the colors of each room’s walls and Wilton carpets. An “Inventory of Contents Remaining in [the] Cadwalader House” taken in 1786 lists two blue damask window curtains, a blue damask settee cover, ten blue damask chair covers, two yellow silk damask window curtains, ten yellow silk damask chair bottoms, and “1 cover of a settee for do.”[10]

Although the records pertaining to the upholstery of Cadwalader’s seating furniture are both detailed and extensive, the physical evidence on the commode-seat chairs documents a history of coverings more complicated than previously thought. All of the side chairs examined for this article had six strips of webbing, three nailed to the side rails and three to the front and rear rails (fig. 21). Fleeson would have pulled the front-to-rear strips much tighter than the other webbing in order to maintain the shape of the seat frame. After attaching the webbing, he nailed a layer of “canvis” to the top face of the seat rails to provide a foundation for the stuffing. The next procedure involved attaching upholstery rolls made of “curled hair” wrapped in canvas. Fleeson evidently stitched the rolls to the foundation canvas and nailed them to the upper edge of the front and side rails. Upholstery peaks (fig. 22) that extended above the seat rail at the outer corner of each front leg established the height of the rolls and profile of the seat (fig. 23a). The front rolls were uniform in height, but the ones on the side rails tapered from approximately 1/2" at the front to 1/4" at the rear. Once the rolls were attached, Fleeson stitched the first layer of hair in place. After building up the cavity with successive layers of hair, he attached the top canvas (fig. 23b). This was a critical step, because Fleeson had to pull the canvas from back to front as he nailed it in place. Only by keeping the canvas in constant tension could he maintain a sharp sweeping edge along the front rail.[11]

Fleeson charged 8s 6d for covering each of the chairs. Evidently this price included materials, since his bill does not include any additional charges for webbing, canvas, hair, tacks, thread, or tape. He probably returned the chairs to the cabinetmaker after January 28, 1771, when he recorded charges for making their slipcovers. Ultraviolet photography and microscopy indicate that the finish on the chairs was applied after the foundation upholstery (figs. 24, 25). Another Philadelphia side chair (figs. 26, 27), which may also be a product of Randolph’s shop, had its foundation upholstery and finish applied in the same sequence. Not surprisingly, its rail flouresces like those on the Cadwalader set.[12]

Evidence suggests that the slipcovers made by Fleeson and Webster fit rather snugly against the seat rails. Both sets of covers probably had shaped lower edges that conformed to the carved strapwork on the front and side rails. The narrow fringe stitched to the edges of the covers may have hung above or just over the carving.

With the exception of the chair illustrated in figure 3, all the commode-seat examples have two holes drilled with a spoon bit in the front and side rails (fig. 28). These holes appear to have been intended for tying on slipcovers, but it is impossible to determine if they are original. A strip of tape or cord attached to the covers would have been inserted through the holes at the back of each side rail and tied off in the middle. The remaining cords would have been tied off at each front corner (fig. 29).[13]

Although at least one set of slipcovers remained in the Cadwalader house until 1786, the chairs were subsequently fitted with fixed upholstery. The front and side rails have clear imprints from a row of brass nails with square, tapered shanks and heads approximately 1/2" in diameter. The nailing follows the curves of the carved strapwork, but varies from a maximum height of 1/2" to a low of 3/16" (figs. 30, 31). The unevenness in this pattern suggests that one set of slipcovers—probably the damask ones made by Webster—may have been reused. The fringe stitched to the lower edge would have made inconsistencies in the nail pattern almost imperceptible (fig. 32), and the tacks used to secure the edges of the covers adjacent to the carving would have been hidden (fig. 33).

By the fall of 1772, the Cadwaladers had nearly completed the furnishing of their townhouse. Their residence there was shortlived, however, owing to Elizabeth’s death in 1776 and John’s service in the Revolutionary War. During the British occupation of Philadelphia, Generals William Howe and William Knyphausen commandeered Cadwalader’s house. The latter made a relatively detailed list of the furnishings, most of which appear in the 1786 inventory.[14]

During the late 1770s and early 1780s, Cadwalader, his new wife Willimina Bond, and their children spent much of their time at Shrewsbury Farm in Kent County, Maryland. On January 8, 1786, he wrote Richard Tilghman that he could no longer afford to maintain two households. John died of pneumonia the following month. Willimina subsequently moved back to Philadelphia, having been left life tenancy in the townhouse “together with all the . . . furniture.” She lived in the house until September 1787, when she leased it to her brother Phineas Bond. Willimina and her family moved into a house at 35 Union Street; presumably she took most of the furnishings with her. They remained in her possession until 1819, when Willimina moved to England.[15]

Although it is impossible to determine precisely when or why the commode-seat chairs were fitted with fixed covers, the brass nails used to attach them and other physical evidence on the seat rails suggest that the alteration occurred during the late eighteenth century. By 1786, several of the objects commissioned by John and Elizabeth Cadwalader had fallen into disrepair. The front garret contained “10 old mahogany chairs many broke,” a damaged washstand, and two trunks containing the damask window curtains, fabric for mending them, ten blue damask chair “covers,” and ten yellow damask chair “bottoms.” These references, Willimina’s moves, and her family’s reduced finances support the theory that the slipcovers were reused, probably after she moved to Union Street.[16]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the authors thank Colonial Williamsburg photographers Hans Lorenz and Craig McDougal and furniture conservators Mark Kutney and Alan Miller.

John Cadwalader Waste Book, box 8, General John Cadwalader section (hereafter cited GJCS), Cadwalader Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, p. 53. The payment to Peale was for “2 minature & 3 portrait Paintings in full.” For more on the sitters, see Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), pp. 108–11, 114–15. Some scholars have argued that the chair in Lambert’s portrait is from a different set because it has plain stiles; however, evidence suggests otherwise. Peale’s portrait of the John Cadwalader family depicts one of the commode front tables owned by Cadwalader. The table and chair in the paintings show similar degrees of artistic license when compared with the actual objects. For more on these portraits, see ibid., pp. 108–11, 114–15.

All of Cadwalader’s commode-seat side chairs are numbered on the underside of the shoe. On the chair shown in figure 3, the number was made with a chisel using converging angled cuts. The chair illustrated in fig. 5 has the number 11 on the rear seat rail under the shoe.

Samuel W. Woodhouse, Jr., “Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia,” Antiques 11, no. 5 (May 1927): 366–71; and Samuel W. Woodhouse, Jr., “More About Benjamin Randolph,” Antiques 17, no. 1 (January 1930): 21–25. For more recent studies of these chairs, see Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), pp. 113–15; Philip D. Zimmerman, “A Methodological Study in the Identification of Some Important Philadelphia Chippendale Furniture,” in American Furniture and Its Makers, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Chicago: University of Chicago Press for the Winterthur Museum, 1978), pp. 193–208; and Mark J. Anderson, Gregory J. Landrey, and Philip D. Zimmerman, Cadwalader Study (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum), pp. 8–13.

Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 22. Wainwright notes that Cadwalader purchased a painted high-post bedstead, window cornices, and rods and hooks from Randolph in September 1769. Part of the £94.15 payment to Randolph may have been for this work (Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 38).

For more on the chairs with Randolph labels, see Philip D. Zimmerman, “Labeled Randolph Chairs Rediscovered,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998), pp. 81–99. Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III: Hercules Courtenay and His School,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1052–63. Ringgold had business dealings with John Cadwalader (Thomas Ringgold and Co. to John Cadwalader, October 21, 1769–December 9, 1770, GJCS) and an account with Benjamin Randolph. Randolph’s account book contains a debit entry under Ringgold’s name “To Shop £23.6.6” (Pennsylvania-Philadelphia Account Book, 1768–1787, Rare Books and Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library, p. 144). For more on Courtenay’s apprenticeship, see Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art II, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Random House, 1985), p. 24. Courtenay signed the Non–Importation Agreement in 1765 (Philadelphia: Three Centuries, p. 111), the same year he began work in Randolph’s shop (Benjamin Randolph Receipt Book, 1763–1777, Winterthur Museum). Randolph made several payments on Courtenay’s account. The carver’s term probably expired by May 19, 1768, when he married Mary Shute (Philadelphia: Three Centuries, p. 111). Courtenay advertised independently in the August 7, 1769, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette. His bill for architectural carving in Cadwalader’s house is in Incoming Correspondence, Bills, and Receipts, 1770, box 2, folder 17, GJCS and is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 12.

Pennsylvania-Philadelphia Account Book, 1768–1787, passim. For more on the styles of other major Philadelphia carvers, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part I: James Reynolds,” Antiques 125, no. 5 (May 1985): 1120-33; Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,”Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 498-513; and Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III: Hercules Courtenay and His School,” pp. 1044–63. Plates 1–5 in Matthias Lock’s The Principles of Ornament, or the Youth’s Guide to Drawing of Foliage (1769), illustrate the principle of placing more complex designs closer to the eye. Similarly, Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet Dictionary (1803), states:

Figures, foliage, and flowers are the three great subjects of carving; which, in the finishing, require a strength of delicacy suited to the height or distance of the object from the eye. . . . It requires some command of the mind, for the carver to work so close as to suit considerable height or distance; in which case, his eye, in working at so short a distance, must not govern him . . . but his judgement must take the lead, and constantly suggest to him the folly of finishing, in a tender manner, those flowers, and foliage . . . which are only to be viewed at a distance.

In architectural carving, apprentices and less experienced journeymen often worked on cornice moldings, brackets, and flowers, whereas master carvers and more accomplished journeymen focused their attention on chimneypiece appliqués and other prominent components. A ceremonial chair in St. Peter’s Church in Philadelphia has an elaborately carved back with acanthus leaves that are very similar to those on the backs of the Cadwalader commode-seat chairs. The carved details on the ceremonial chair are more carefully rendered, like those from the Ringgold and Stamper-Blackwell parlors.

Cadwalader Waste Book, p. 63. Morrison H. Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1974), p. 185. The author thanks Charles Hummel for the information on Randolph’s venture.

This estimate of Elizabeth Lloyd’s wealth does not include her land on Maryland’s eastern shore, seventy-eight slaves, one hundred horses, and livestock (Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 3). In 1774, John Adams wrote, “we visited a Mr. Cadwallader a Gentleman of large Fortune, a grand and elegant House and Furniture.” Ibid., pp. 11, 13, 19–20, 33, 104. Thomas Nevell worked on several important Philadelphia buildings, including Captain John McPherson’s house, Mount Pleasant, in Fairmount Park (Thomas Nevell Account Book, Rare Book Collection, University of Pennsylvania). For more on these carvers and their work for Cadwalader, see Beckerdite, “Bernard and Jugiez,” 502–5; and Beckerdite, “Hercules Courtenay,” p. 1051. The bills for all of these carvers are either reproduced or transcribed (Randolph) in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur.

Thomas Affleck to John Cadwalader, April 18, 1771, box 2, folder 18, GJCS. Affleck’s bill requested payment for eighteen pieces of furniture, two knife trays, bed and window cornices, and services from October 13, 1770, to January 14, 1771. Notations at the bottom of the bill indicate that Affleck subcontracted the carving on these pieces to James Reynolds and the shop of Bernard and Jugiez. Affleck’s bill, which totaled £119.8, is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 44. Bernard and Jugiez’s receipted bill, dated February 13, 1771, is in box 2, folder 18, GJCS. Reynolds’s receipted bill, dated June 29, 1771, is in box 2, folder 20, GJCS. The bills from both carving firms are reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 29, 46.

The bills from Fleeson, Webster, and Rushton & Beachcroft (the London company that provided the silk fabrics, fringe, and tape) are reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 40–41, 59, 61. For more on the wall colors and carpets in Cadwalader’s house, see ibid., passim. Cadwalader owned a second suite of furniture with hairy paw feet and straight rails. Examples are in the Winterthur Museum, Stratford Hall, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The chairs and matching card tables in the second suite may have sat in the small front parlor, which had green walls. Assuming that there were twelve chairs in this suite and twenty commode-seat chairs, that would account for the thirty-two that Fleeson covered over the rail. Although chair “bottoms” could be interpreted as slipseats, this term probably referred to slipcovers. The use of two terms in the inventory may result from its having been taken by John Cadwalader’s sister Rebecca and his brother-in-law Samuel Meredeth. Three copies of the inventory survive, and they vary slightly. The 1786 inventory also lists one mahogany dining table, one marble slab [table], and one card table in the “small front parlor”; one marble slab [table], one card table, and ten mahogany chairs, in the “back parlor”; one large settee, one small settee, one card table, ten mahogany chairs in the “front parlor”; one small settee in the “entry” on the second floor; six mahogany chairs with chintz “furniture” in the “back chamber” on the second floor; six mahogany “carpet bottom” chairs in the “front chamber” on the second floor; two old chairs and six mahogany chairs in the “front room” on the third floor; and two green covers for card tables, one large easy chair, and ten old mahogany chairs “many broke” in the “front garrett” on the third floor (ibid., p. 73).

Although Fleeson’s name is used in conjunction with the upholstery on the commode-seat chairs, journeymen probably did much if not all of the work. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 40–41.

Ibid., pp. 40–41. Colonial Williamsburg conservator Mark Kutney performed the finish microscopy.

The side chair illustrated in fig. 3 may have left the Cadwalader family as early as the 1780s. Recent research by Jennifer Olshin suggests that the chair passed from the Cadwalader family to David Lewis (1766–1840), who lived on “Second Street north of Spruce” (Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art and Chinese Porcelain, October 14, 1999, lot no. 174, p. 89). Lewis may have purchased the chair from Cadwalader’s second wife, Willimina, or from one of John’s children. (For more on Willimina and the Cadwalader children, see Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 72–77.) If this history is correct, it supports the theory that the slipcovers were originally tied off at the rear stiles and that the holes in the rails are additions. Screws have been inserted in some of the holes, possibly to attach a deck for spring upholstery. A circa 1720 armchair attributed to James Moore has seat covers tied off in a similar manner (Geoffrey Beard, Upholsterers and Interior Furnishings in England [New Haven: Yale University Press for the Bard Graduate Center, 1997], p. 176, fig. 151-4).

Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 61–67.

Ibid., pp. 68–77.

Ibid., pp. 72–73.