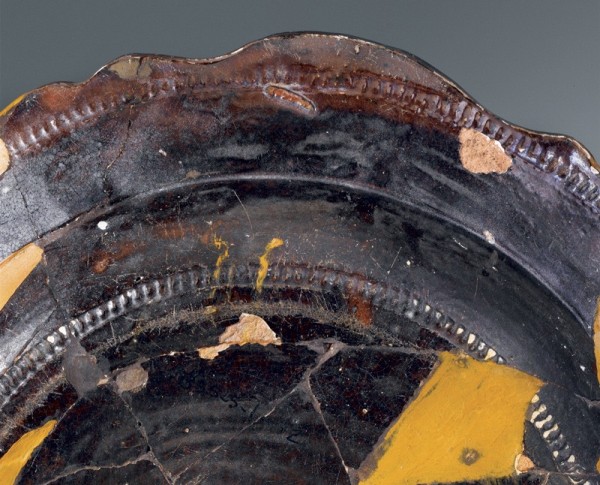

Dish, Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1795. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, probably southern Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790– 1820. Lead-glazed earthenware with polychrome slip decoration. D. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

L. F. Schmuz, View of Herrnhut, Dresden, Germany, 1775–1800. Engraving on paper. 17 x 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

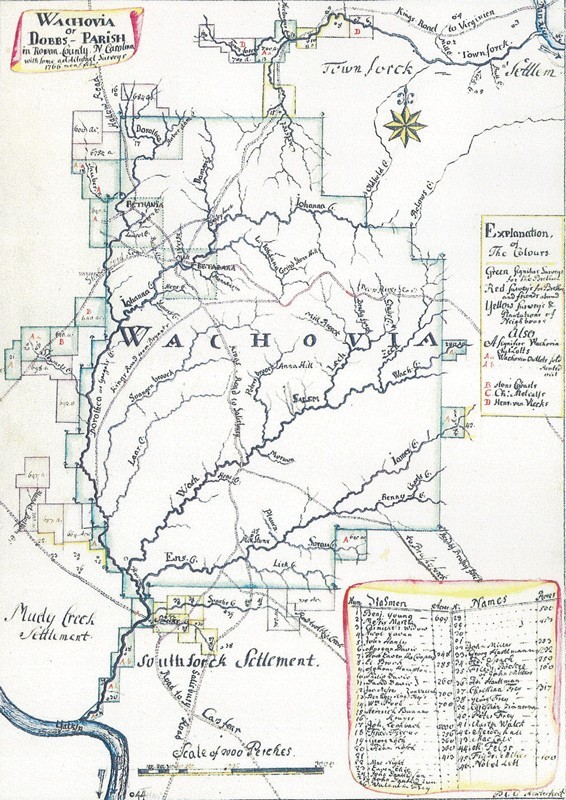

Christian Gottlieb Reuter, Map of Wachovia, Salem, North Carolina, 1766. Ink and watercolor on paper. 18 1/2 x 11 3/8". (Courtesy, Unity Archives, Herrnhut.)

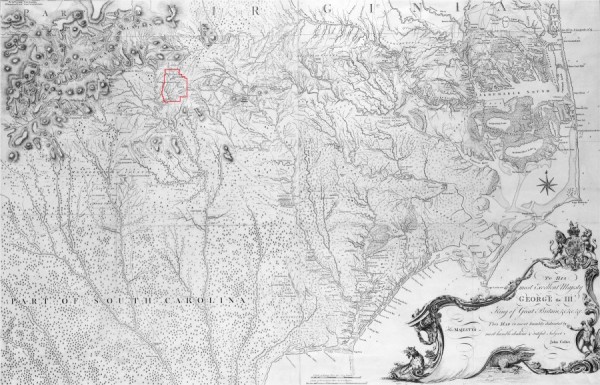

A Compleat Map of North Carolina from an Actual Survey, published by John Collett, London, 1770. The red line shows the approximate boundaries of the Wachovia tract. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

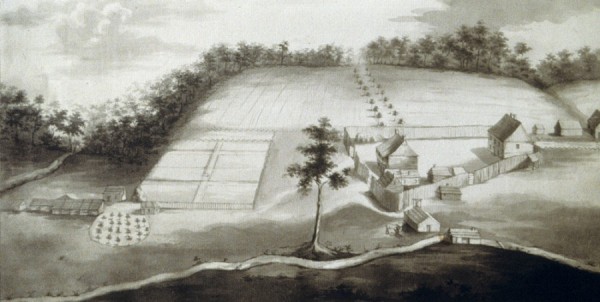

Prospect of Bethabara, Bethabara, North Carolina, ca. 1757. Drawing on paper. 10 1/2 x 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Moravian Archives, Herrnhut.)

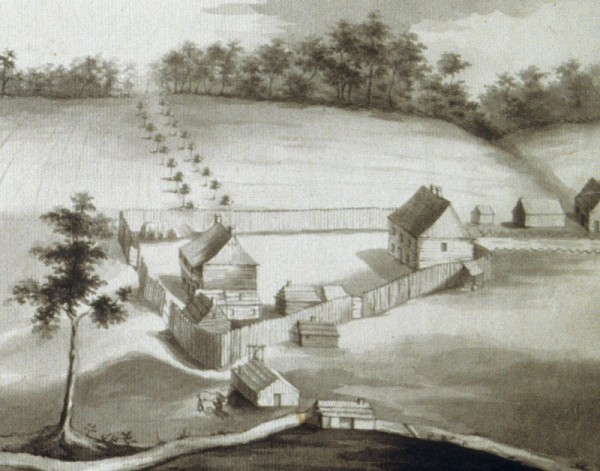

Detail of Prospect of Bethabara showing Aust’s pottery shop at the corner of the fort.

Composite illustration showing glazed and bisque mug fragments recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. H. 3 3/8" (glazed on left). (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The base on the left is coated with an iron-bearing lead glaze, whereas the base on the right received only a bisque firing. The bottom of the glazed mug is incised with a mark that appears to be the letters H and P conjoined. These mug fragments are probably similar to those used for Love Feast, a religious service that included a simple meal of bread and coffee or tea. Most of the artifacts excavated at Bethabara are housed at Old Salem Museums & Gardens under a custodial agreement between that institution Historic Bethabara Park, and the Southern Province of the Moravian Church. Artifacts in the archaeological collection of Historic Bethabara Park are identified by that organization’s name in the credit line.

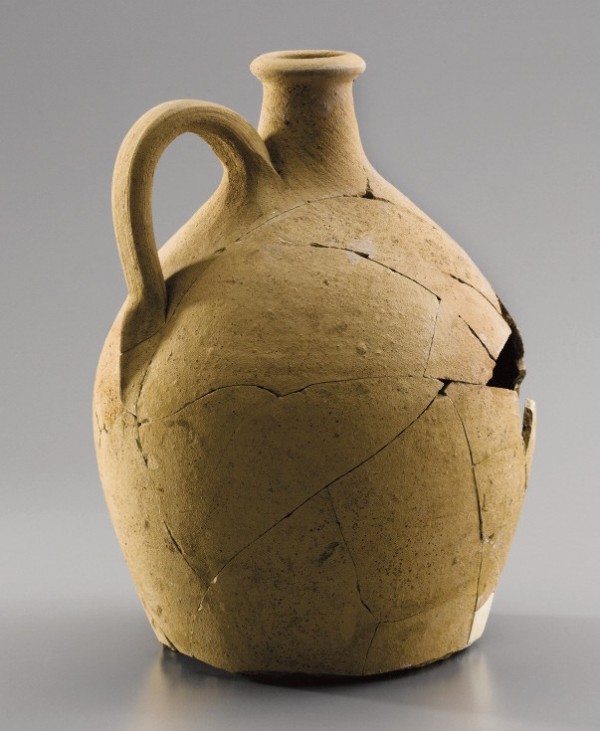

Jug, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. H. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

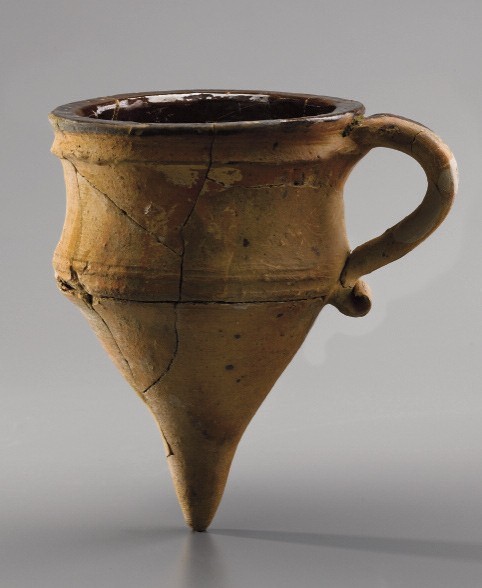

Funnel, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 3/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Cook pot, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Base and top of a candlestick and a fat lamp, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware (candlestick fragments) and lead-glazed earthenware (lamp). H. 4 3/4"(lamp). (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Composite illustration showing overalls and marly details of bisque-fired and lead-glazed dishes recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. D. 14 3/4" (top), 12 1/4" (bottom). (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail showing the back of the bisque-fired dish illustrated in fig. 13.

Teabowl, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. D. 3 3/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

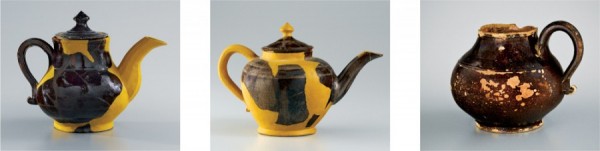

Teapots, attributed to Gottfried Aust’s pottery, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park [left], Old Salem Museums & Gardens [center], and private collection [right].) The archaeological examples were recovered at Aust’s site; the example at the far right descended in a family from Randolph County, North Carolina.

Bowl fragment, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park; photo, Wesley Stewart.) When successfully glazed and fired, this example would have resembled the bowl illustrated in fig. 18, right.

Slip-decorated bowls, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, ca 1785 (left); Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789 (right). Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 6". (Private collection [left]; Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [right].) The archaeological example on the right was recovered from the site of the gunsmith’s shop at Bethabara and probably was made by Rudolph Christ, although Gottfried Aust produced similar examples, as illustrated in fig. 17.

Dish fragments, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Dish fragment, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Dish, Germany, 1740–1760. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 21.

Ludwig Gottfried von Redeken, A View of Salem in North Carolina, 1788. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

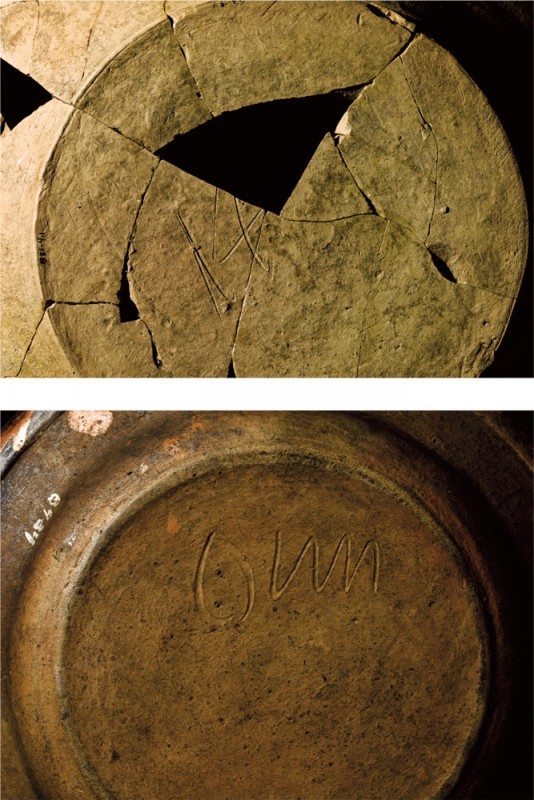

Details of marks on a dish made at Bethabara (top) and a dish made at Salem (bottom). (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

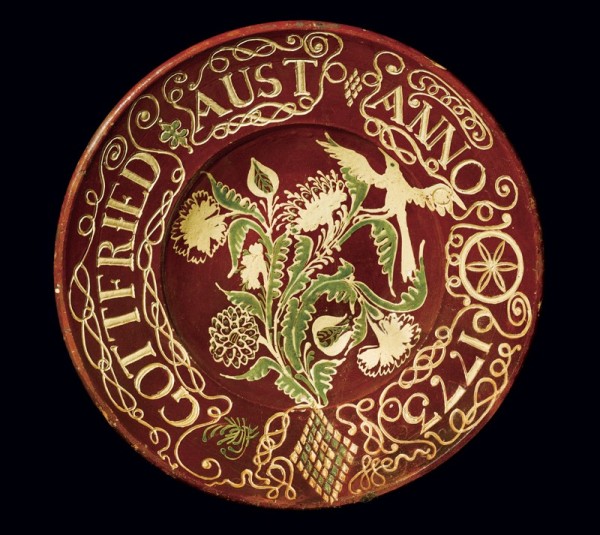

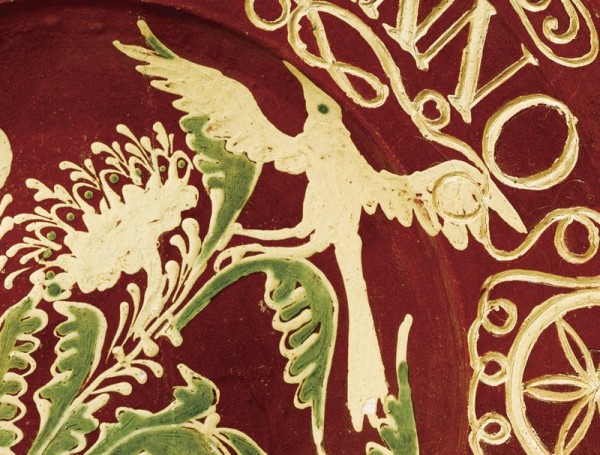

Shop sign made during Aust’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1773. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) Attached to the back are two clay lugs pierced to receive the cord from which the sign hung. The exceptional condition of this object suggests that it hung inside Aust’s shop.

Detail of the decoration on the dish illustrated in fig. 25. Layout lines are visible above and below the letters.

Detail of the decoration on the dish illustrated in fig. 25.

Dish, Nevers, France, ca. 1685. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Musée National de Céramique, Sèvres.)

Jan Davidsz de Heem, Vase of Flowers, Holland, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas. 27 3/8 x 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Fund.)

Dish, probably made during Aust’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1785. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The flowers depicted on this dish are roses. Nearly identical representations of those flowers can be found in early botanical prints.

Dish, probably made during Aust’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1785. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish, probably made during Aust’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1785. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the decoration on the dish illustrated in fig. 32.

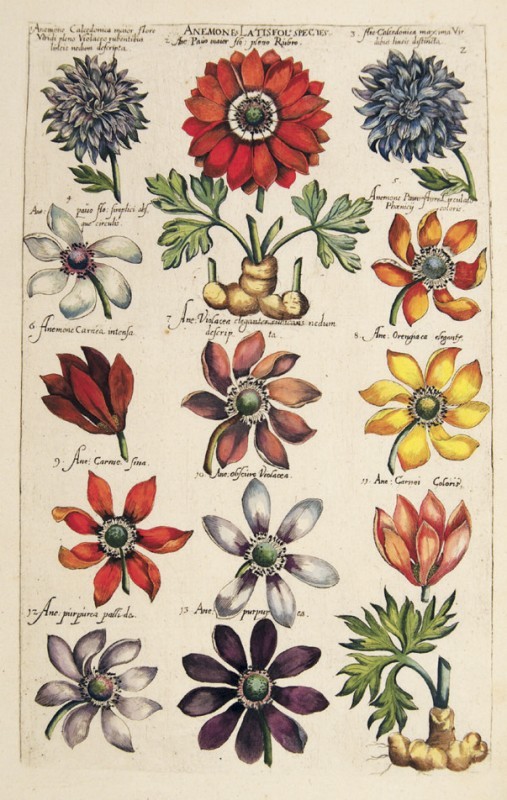

“Anemones Latisfol Species,” in Emanuel Sweerts, Florilegium amplissium et selectissimum, Amsterdam, 1647. Copperplate engraving with later color. 13 x 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Church Gallery, Chelsea, London.) Sweerts’s Florilegium was originally published in Frankfurt in 1612.

Dish, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This dish descended in the Hall family of Salem.

Dish fragment, recovered at Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish fragments, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1780– 1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Lot 49 was adjacent to the pottery.

Plate, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Plate, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This dish and the example illustrated in fig. 43 descended in the Ellers family of Rowan County.

Dish, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This dish and the example illustrated in fig. 42 descended in the Ellers family of Rowan County.

Dish, probably made during Aust’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1785. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13". (Courtesy, The Henry Ford.)

Dish, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1772–1820. D. 13". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Saucer and bowl, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1772–1820. D. 6 1/4" (saucer). (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Sugar bowl, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1772–1820. H. 6". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.)

Teapot, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 7". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This important object might have been produced by William Ellis during his 1774 visit to the Salem pottery or was a later creation of Rudolph Christ.

Sprig mold, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1780. High-fired clay. L. 2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The back of this mold bears the initials “RC” for Rudolph Christ. Given the fact that the initials were cut after firing, it is possible that this mold is one of those Christ stole from the Salem pottery in 1779.

Teapot handle, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The teapot to which this handle belongs might have been produced by William Ellis during his 1774 visit to the Salem pottery or was a later creation of Rudolph Christ.

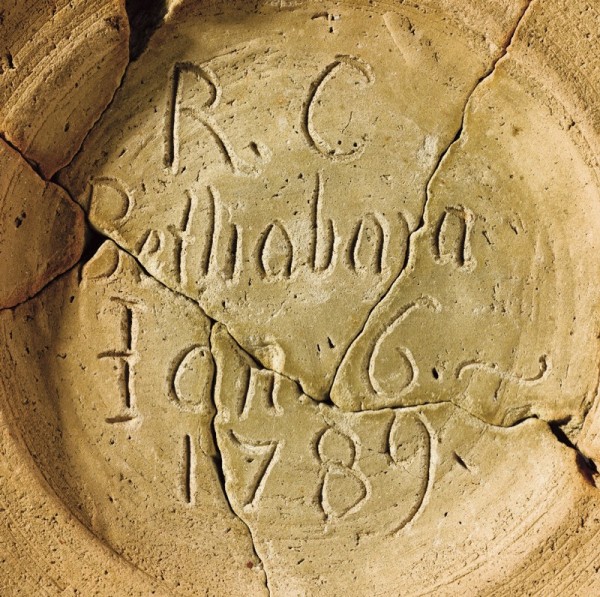

Plate mold, Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789. Plaster. D. 10 7/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Detail showing the inscription on the mold illustrated in fig. 51: “R. C / Bethabara / Jan. 6.~ / 1789.”

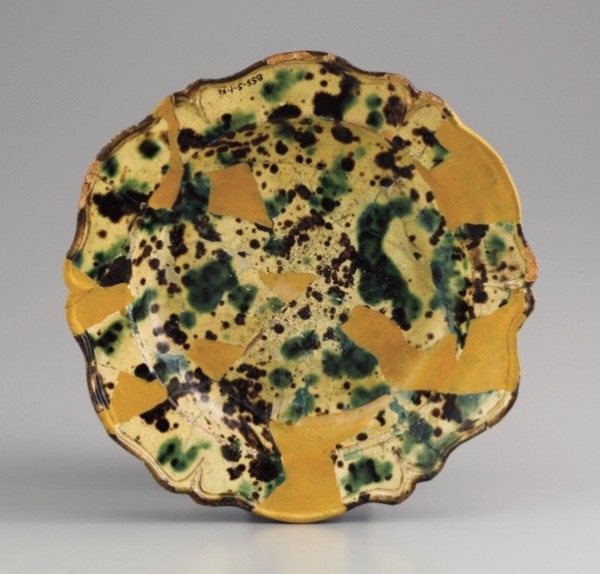

Dish, recovered at Rudolph Christ’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 53.

Detail of the dish illustrated in fig. 53, showing the pink body and white slip.

Dish fragments, recovered at Rudolph Christ’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) A small amount of glaze, inadvertently dripped on the marly, shows how the outermost concentric and wavy slip lines would have appeared after firing.

Dish fragment, recovered at Rudolph Christ’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Dish fragment, recovered at the site of the gunsmith’s shop occupied by Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Ring bottle, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Plate fragments, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Ring bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1795–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.)

Dish, probably made during Rudolph Christ’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, probably made during Rudolph Christ’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, probably made during Rudolph Christ’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 14". (Private collection; photo, James and Nancy Glazer American Antiques.)

Dish fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish fragment, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish fragments, recovered at the site of Gottlob Krause’s pottery, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1790–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Dish fragment, recovered at the site of Gottlob Krause’s pottery, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1790–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Dish, Friedrich Rothrock, Forsyth County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Friedrich Rothrock, Forsyth County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Private collection.)

Jug, Friedrich Rothrock, Forsyth County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/4". (Private collection.)

Detail of the dish illustrated in fig. 71, showing the impressed mark on the back.

Dish, attributed to George Hubener, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of John T. Morris.)

Hendrick Goltzius, Youth with a Skull and a Tulip, Holland, 1614. Ink on paper. 18 1/2 x 13 7/8". (Courtesy, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.)

Dish, attributed to George Hubener, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1785. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; Baugh-Barber Fund.)

Hans Memling, Flower Still-Life, Holland, ca. 1485. Oil on oak panel. 11 1/2 x 8 7/8". (Courtesy, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.)

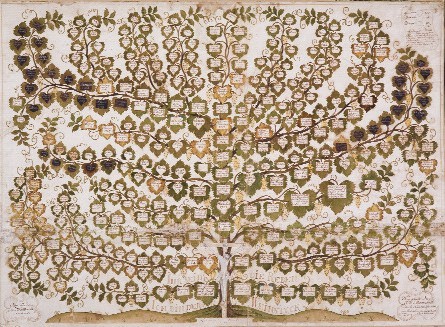

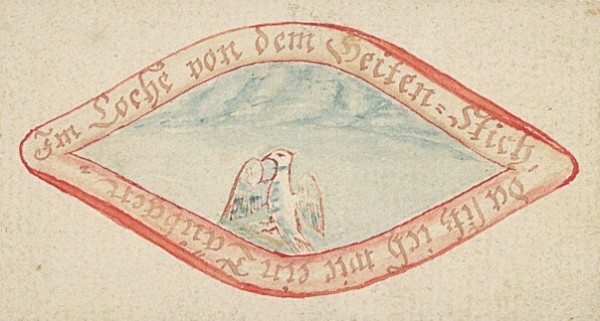

Illuminated manuscript, designed by Friedrich von Watteville and executed by P. J. Ferber, Herrnhut, Germany, 1775. Ink and watercolor on paper. 27 x 37". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the illuminated manuscript illustrated in fig. 79.

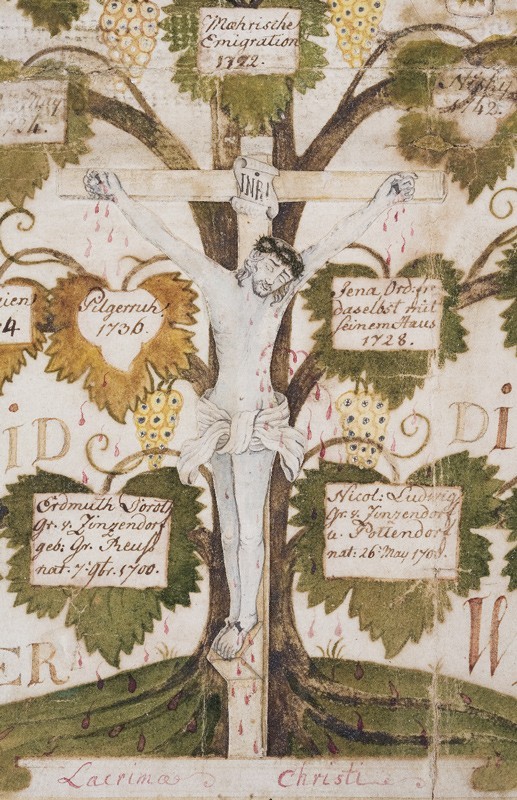

Unknown artist, painting depicting the Crucifixion of Christ, Herrnhut, Germany, ca. 1750. Watercolor on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Unity Archives, Herrnhut.)

Unknown artist, devotional card, Herrnhut, Germany, ca. 1750. Watercolor and thread on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Unity Archives, Herrnhut.)

Dish, probably made during Aust’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1785. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 14 1/8". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.)

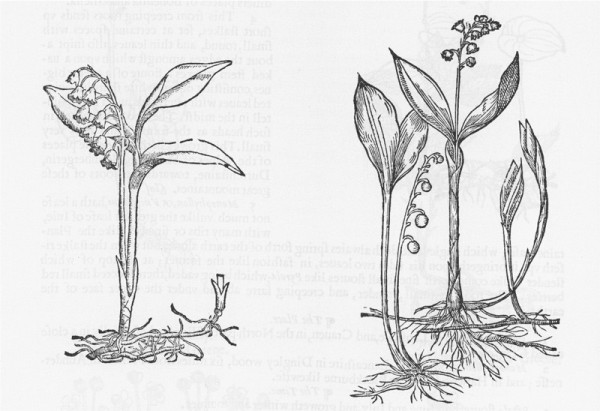

Detail of the decoration on the dish illustrated in fig. 32. The round, podlike designs on the stem probably were intended to represent lilies of the valley, which also appear on the dish fragments illustrated in fig. 69.

Period botanical showing red anemones. (John Gerard, The Herbal: or, General History of Plants [1633; repr., New York: Dover Publications, 1975], p. 379.)

Period botanical showing lilies of the valley. (Gerard, The Herbal, p. 410.)

John Valentine Haidt, Cornelius Foreseeing His Christianity, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, ca. 1755. Oil on canvas. 24 5/8 x 20". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Haidt’s paintings were used as educational tools in Moravian congregations throughout Europe and America. The flowers illustrated in this painting were symbolically charged, as suggested by the rose held by the Christ Child as he gazes into his mother’s eyes. In Christian theology, Christ is described as the rose among thorns and Mary as the rose without thorns. Roses also served as symbols for the messianic promise and the Virgin Mary. Not surprisingly, roses are common on eighteenth-century Wachovia slipware (see fig. 30).

Detail of the white anemone in the foreground of the painting illustrated in fig. 87.

Detail of a flower on the dish illustrated in fig. 63.

Raffaellino del Garbo, Madonna Enthroned with Saints and Angels, Italy, 1502. Oil on panel. 78 x 82 1/2". (Courtesy, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; gift of the Samuel Kress Foundation.)

Sandro Botticelli, Madonna of the Pomegranate, ca. 1487. Tempera on wood panel. D. 56 1/2". (Courtesy, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.)

Dish fragment, recovered from an unidentified cellar, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1760–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Composite illustration showing different representations of pomegranates in Bethabara and Salem slipware. The details are taken from the dish fragment illustrated in fig. 92 (left), the dish illustrated in fig. 67 (middle), and the dish illustrated in fig. 62 (right ).

Dish, probably made during Rudolph Christ’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Detail of the decoration on the shop sign illustrated in fig. 25.

Unknown artist, devotional card, Herrnhut, Germany, ca. 1750. Watercolor on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Unity Archives, Herrnhut.)

The essays presented in this volume of Ceramics in America challenge many traditional assumptions about North Carolina earthenware, yet all are indebted to research and publications extending back more than eighty years. One of the earliest and most insightful scholars of Southern ceramics was Joe Kindig Jr., a York, Pennsylvania, antique dealer whose first article on North Carolina pottery appeared in the January 1935 issue of The Magazine Antiques.[1] In that publication, he illustrated slipware from three of the principal pottery-making traditions of the North Carolina piedmont and noted how those wares differed from Pennsylvania work. More important, much of the Southern slipware now in public collections passed through Kindig’s hands.[2]

Articles devoted to eighteenth-century North Carolina earthenware have appeared in various periodicals, including The Magazine Antiques and the American Ceramic Circle Bulletin, but John Bivins Jr.’s The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (1972) was the first monograph that focused on a single pottery tradition.[3] In that book he used archaeological evidence, surviving artifacts, and the Moravians’ meticulous records to illuminate the lives and work of potters active in the towns Bethabara, Bethania, and Salem. Bivins provided biographical information on all of the potters known to have worked in the Moravian settlements during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; however, the bulk of his study centered on two shop masters—Gottfried Aust and Aust’s former apprentice Rudolph Christ. In Bivins’s view, Aust was the archetypal immigrant master, wedded to Old World modes of earthenware production and decoration (fig. 1), whereas Christ was an innovator who developed his own decorative vocabulary in slipware (fig. 2) and experimented with the manufacture of refined creamware, stoneware, and faience.[4]

Although Christ’s interest in the production of “fine pottery” is documented in Moravian records, there is no evidence that his utilitarian earthenware and slipware differed significantly from that of his master. Indeed, recent research by the authors and Linda Carnes-McNaughton suggests that most of the slipware formerly attributed to him was made by a closely knit group of Germanic potters working in the vicinity of southern Alamance County, North Carolina. When this material is removed from consideration, the Moravian tradition appears much more cohesive than previously thought. Rather than being simply decorative, the motifs used by Aust and his predecessors were deeply rooted in Moravian theology and metaphorical imagery.

From Saxony to Wachovia

The Moravians who settled in North Carolina were members of a Protestant sect who traced their origins to John Hus, the Bohemian martyr who was burned at the stake in 1415 for challenging canons of the Roman Catholic Church. His followers subsequently formed the Unitas Fratrum, or Unity of Brethren, and spread their faith across Bohemia, Moravia, and Poland. As persecution became more widespread during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many members of the Unitas Fratrum, or Moravians as they became known, sought refuge in more tolerant countries. Nicholas Lewis, count of Zinzendorf and a member of the Order of the Grain of Mustard Seed, became their greatest patron, allowing refugees from Bohemia and Moravia to settle on his ancestral lands in Saxony in 1722 as an act of devotion to the Pietistic ideal of life. Almost immediately, the Moravians began raising buildings for their first town, Herrnhut (fig. 3). Located just east of Dresden, Herrnhut was ideally situated for the sect’s missionary efforts and trade.[5]

During the second quarter of the eighteenth century Zinzendorf became the Unitas Fratrum’s principal spiritual leader. Combining aspects of Pietism, Orthodox Lutheranism, and enlightenment thought, his theology embraced the belief that members of congregations should live together under a “choir” system, segregated by gender, age, and marital status. Because each member of the sect was expected to contribute to the spiritual and material well-being of the community, work was considered service to God. When planning settlements and towns from which to launch their missionary efforts, Zinzendorf and other church leaders debated which trades would be the most advantageous for their respective communities.[6]

After a failed attempt to set up an outpost in Georgia, the Moravians turned their attention to Pennsylvania. Bethlehem was the first and most important town they established in the middle colonies (1741). As was the case at Herrnhut, Bethlehem was closed to outsiders. The church controlled all of the land under a leasehold system and regulated the spiritual, social, and economic affairs of the community through various administrative bodies. Visitors could conduct business with shopkeepers and tradesmen and find food, drink, and lodging in the town’s taverns, but they could not acquire property or overstay their welcome.[7]

Widely recognized as peaceful and responsible colonists, the Moravians had little trouble convincing North Carolina proprietor Lord Granville to sell them 100,000 acres of land in the central piedmont region—a tract they named Wachau or, in English, Wachovia (figs. 4, 5). As was the case with most ventures undertaken by the Unitas Fratrum, development of the Wachovia tract was meticulously planned. A temporary settlement would allow the Moravians to gain a foothold in the wilderness and later serve as a staging area for building a town on a site better situated for their manufacturing and missionary efforts.[8]

The men chosen to travel from Pennsylvania and establish the church’s outpost in North Carolina were eminently suited to their task. Their skills included gardening, animal husbandry, baking, brewing, shoemaking, tailoring, barrel making, carpentry, turning, distilling, and surveying. The group arrived on November 17, 1753, and took shelter in an abandoned log cabin. The following day the men began clearing land for the community they named Bethabara, meaning house of passage. Within two years they had made numerous improvements, felled and shaped timbers for buildings intended for the new settlement, and erected a large log house to shelter the single males and married couples scheduled to arrive in the winter of 1755 (fig. 6).[9]

The First Pottery

Since early 1754 the residents of Bethabara had petitioned for the establishment of a pottery. Church leaders in Bethlehem resisted because they did not feel that pottery was a trade necessary for the frontier community. With plans for a new town under way, they also wanted to avoid the expense of establishing a manufactory at Bethabara only to have it move a few years later. In September 1755 Moravian bishop Augustus Spangenberg changed course, persuaded that the income generated by a pottery would help the Bethabara community become more self-suficient.[10]

Among the new settlers who arrived at Bethabara in the winter of 1755 was master potter Gottfried Aust (fig. 7). Born in Heidersdorf, Silesia, in 1722, Aust had learned to weave linen with his father before serving an apprenticeship with Herrnhut potter Andreas Dober beginning about 1742. Aust probably worked as a journeyman in Dober’s shop before immigrating to America in 1754.[11] Soon after arriving at Bethabara, Aust began searching for clay and flint, a basic ingredient of lead glaze. The “Wachovia Diary,” a journal that records much of the history of the early settlement, notes that on November 28, 1755, the grist mill was “run for the first time . . . in grinding flint for glazing” and “it made a fine powder.”[12] The following month Aust began to turn pottery and to make clay pipes, which suggests that he had assistance constructing a wheel, pug mill, and other equipment. In April 1756 he built his first kiln, a “small oven” presumably used to determine the suitability of local clays and glaze components and to test his building materials and design. A larger kiln was completed in August, when Aust burned earthenware in it for the first time. A few weeks later the master potter performed his glazing, or “glost” firing. Like many of his European contemporaries, Aust fired his ware twice—the first to harden the body (and slip, if decorated), and the second to burn the glaze. According to the Wachovia Diary, “the glazing did well, and so the great need [for pottery] is at last relieved. Each living room now has the ware it needs, and the kitchen is furnished. There is also a set of mugs of uniform size for Love Feast” (fig. 8).[13]

During his tenure as master of the Bethabara pottery, Aust took at least five apprentices. Peter Stoltz arrived in Wachovia in 1762 and four years later was listed as a potter in the “Catalogue of the Inhabitants of Bethabara.” He left the pottery in 1767 to work as a brick maker.[14] Under the heading “boys and prentices,” the catalog listed three other potters: Joseph Müller, Ludwig Möller, and Rudolph Christ. Möller and Christ completed their terms and became journeymen, but there is no mention of Müller after September 1766.[15] The only potter not trained by Aust was Michael Marr from Coburg, Germany. Because Marr arrived in Wachovia in 1762 and left shortly thereafter, it is unlikely he left a stylistic imprint on Bethabara work.[16]

Sherds excavated at Aust’s pottery site indicate that an overwhelming majority of the wares he produced at Bethabara were utilitarian. Archaeologist Stanley South, who conducted extensive excavations at both Salem and Bethabara, documented twenty-eight forms for storing, preparing, and serving food and liquids, several models of pipes, apothecary jars, and lighting devices, and a more recent survey of the material recovered from Aust’s kiln wasters suggests even greater variety. Wares of this type were essential for daily life, and their sale to outsiders provided a much-needed source of income for the community. Word of Aust’s pottery quickly spread throughout the Carolina backcountry, and he often had difficulty meeting local demand. After one kiln opening, a resident observed: “[T]here was an unusual concourse of visitors, some coming from sixty or eighty miles to buy milk crocks and pans at our pottery. They bought the entire stock, not one piece was left; many could get only half [of what] they wanted, and others, who came too late, could find none.”[17]

Aust’s utilitarian wares reflect his training in an urban shop and are generally more sophisticated in form and finish than much of the earthenware produced by rural potters in colonial America (figs. 9-12). His dishes, plates, and bowls have finely turned bodies and crisp moldings; his skillets and cook pots have deftly modeled feet; and his jugs, milk pans, and basins are equipped with efficiently designed handles. Aust used a variety of measuring and shaping tools to expedite and standardize production. Ribs regulated the size and shape of his teabowls and determined the placement and profile of moldings on mugs and other vessels; jiggers produced dishes and bowls with predictable profiles; and gauges ensured that various hollow ware forms would be of uniform height. Aust’s early dishes, for example, almost invariably have a double-bouge rear profile and an undercut rolled rim (figs. 13, 14).

Although most of Aust’s utilitarian forms differ little from those made by Germanic potters decades earlier, the tea- and coffee wares excavated at Bethabara attest to his familiarity with contemporary European and British examples (fig. 15). During his tenure as an apprentice and journeyman in Dober’s shop, Aust would have been exposed to porcelain from the Meissen factory, established near Dresden under the patronage of Augustus the Strong. Aust’s probate inventory lists “8 pr Cups & Saucers (best Dresden) [probably porcelain],” which he probably acquired before immigrating to America.[18] He may also have seen, if not copied, English teawares in Saxony, since the Crown shipped vast quantities of Staffordshire pottery to the Continent in the eighteenth century. Aust probably gained further knowledge of British ceramic forms during his brief residence in Bethlehem or after he moved to North Carolina. During the 1750s and 1760s the Bethabara community store frequently sent wagonloads of deerskins to Charleston, South Carolina, to be exchanged for consumer goods.[19]

Aust produced at least two teapot designs, one baluster shaped and the other ovoid with a high shoulder (fig. 16). Both models have cognates in English and European ceramics, silver, and pewter. Aust’s teapots have pulled handles and thrown spouts that were finished with a fettling knife, whereas contemporary Staffordshire and Continental examples typically have molded handles and spouts. His use of molds was largely confined to the production of pipes and stove tiles, all of which were press molded.

Archaeological evidence suggests that only a minute percentage of the pottery Aust made at Bethabara was decorated with slip. The demographics and communal organization of the settlement almost certainly influenced patterns of consumption, restricting the production of nonutilitarian ware. For the first two years, Bethabara’s population was entirely male. Between 1755 and 1765 the settlement grew to include sixty-six men and thirty-five women, but most were single and lived in choirs rather than setting up independent households. The ratio of women to men and married couples to singles increased somewhat between 1765 and 1772, but unmarried men remained the largest segment of the population.[20] Logic suggests that single individuals living in segregated choir houses would have been less likely to acquire domestic furnishings than married couples with independent households. The economy under which Bethabara operated until 1772 may also have influenced local consumption of material goods. Under that system, the church owned all property and land in and around the town, and the settlers provided labor in exchange for shelter, food, clothing, medical care, education, and a modest salary.[21] The acquisition of decorative objects was not discouraged, but the means to do so would have been curtailed by the economy.

Most of the decorated sherds recovered at the site of Aust’s pottery are from small bowls (figs. 17, 18), plates, and dishes. As the fragments illustrated in figure 19 suggest, his decorative vocabulary was primarily naturalistic, featuring a variety of flower and leaf designs. One large sherd comprising most of the cavetto of a dish has spiral lobes intended to represent gadrooning (fig. 20). This motif has antecedents dating back to the early seventeenth century in a variety of media, including slipware, tin-glazed earthenware, and metal ware.

Also revealing is what was not found at Aust’s site. There is no archaeological evidence that he made slipware with highly stylized geometric motifs (see fig. 2) or sugar pots like those formerly attributed to Christ. Aust is the only potter known to have introduced Germanic styles during the eighteenth century, and it is difficult to imagine that he would have allowed his workmen to deviate from the tried and true. In his “memorial,” a written account of his life’s work, Aust acknowledged that he had “made a failure of the beginning period [of his apprenticeship] by endeavoring to achieve [his] . . . own improvement.”[22] He would have discouraged workers in his shop from making the same mistake.

Aust’s decorative vocabulary coalesced during his tenure as an apprentice and journeyman in Herrnhut. Although he worked for Michael Oldenwald, master of the Bethlehem pottery, for ten months before moving to Bethabara, there is no evidence that Aust altered his working style, and similarities between his decorated ware and that attributed to Moravian potters in Pennsylvania are largely generic.[23] Aust’s work most closely resembles contemporary German pottery. A German dish formerly attributed to him has cavetto decoration that relates very closely to that associated with Aust, but its clay composition, highly compacted body, and back profile differ markedly from his work (figs. 21, 22).[24]

From Bethabara to Salem

Although Bethabara had become a thriving community by the mid-1760s, church leaders always considered that settlement to be the “farm where agriculture . . . and brewing can be carried on” and the staging point for establishing a gemein ort, or central congregation town.[25] On January 6, 1766, the Moravians felled the first tree for the new town, called Salem—the Hebrew word for peace. Christian Gottlieb Reuter, who had been surveyor to Frederick II, sited the most important buildings—including the Single Brothers House, Single Sisters House, and Gemeinhaus—and reserved the principal streets for shops and houses (fig. 23).[26] By the spring of 1772, Salem was prepared to accommodate settlers relocating from Bethabara. The Moravians abandoned the communal economy at that time, but the church continued to own the taverns, mills, and stores in each town as well as the pottery and tannery in Salem. Workmen in those industries received wages and bonuses and remitted all profits to the church. Although other craftsmen were free to make and sell their wares as they saw fit, the church maintained a measure of control through the Aufseher Collegium—a supervisory board that decided which trades were needed and who would serve as master, approved apprenticeships, mediated disputes, and maintained standards in much the same way as a guild system. The town’s vorsteher, or business manager, represented another layer of control, serving as a channel for contact with outsiders. Like Bethlehem, Salem was a closed community. As historian Daniel P. Thorpe has noted, the Moravians had to trade with the outside world while protecting their faith and insulating the faithful.[27]

The Salem Pottery

Aust moved to Salem in the summer of 1771, occupying a half-timbered building at the north end of Main Street adjacent to the pottery on Lot 48.[28] Along with him came apprentices Ludwig Möller, John Heinrich Beroth, and Rudolph Christ, all of whom were nearing the end of their terms. All over town, tradesmen who had relocated from Bethabara were setting up shops and getting acclimated to their new place of business. “The Branches to be carried on . . . for the benefit of the Salem Diacony [the business organization of the congregation] were the pottery, tavern, store, and tannery.”[29] The managers of those businesses entered into contracts with the community. On August 8, 1771, the Diacony Conference reported:

Br. Aust has been living in Salem with his family for the past 6 weeks and has pretty well set up his pottery. He and his wife and children have hitherto been supported by the Congregation Economy. He has had an understanding with his partner and his apprentice for a certain wage, and this has been charged to the Building Account. From August 1st, however, he takes over the pottery to administer it for the Economy under certain conditions: He pays all expenses of the house and interest on the capital invested in it; repairs, wages of an apprentice, and whatever materials are needed out of the income for the pottery. He receives for his support at least £60 annually. Income over and above these outlays comes to the Diacony. However, we thought if the cash income should fall out “remarkable” we will give him, instead of the £60, half of the clear profit. He is to pay over at the end of each month as much cash as he can spare, and then the rest will be settled at the end of the year. We thought to make the same arrangements for accounts with the other trades to be established in Salem for the Diacony.[30]

The Aufseher Collegium set interest rates and rents for the Diacony’s businesses and established prices for raw materials used in production. On June 10, 1772, the Collegium instructed Aust to pay 1s. 4d. for “each load of pottery clay” and the same amount for “potter wood, which is longer than usual.”[31] The earliest clay source cited in the Moravian records was just east of Church Street. On August 6, 1774, the Collegium noted that “it would be good if [Br. Aust would rent] . . . a piece of land . . . which he can fence in . . . so that the Single Sisters will not have any harm of the remaining part of the meadow.”[32] Later references to “clay from the hollow” and “rent for meadows” indicate that Aust and his successors continued mining his original source.[33] Most of the white clay used for pipes and much of the “fine ware” made after 1774 came from Bethabara.[34]

In 1773 Christ, Möller, and Beroth began working as journeymen.[35] The following year Aust took his adopted son, Johann Gottlob Krause, as an apprentice, depositing “the usual obligation of £100 . . . so that he may not keep the boy against the law of the community or send him away.”[36] Krause had been living with Aust, and probably working for him, since the summer of 1771. In June 1773 the Aufseher Collegium agreed to pay for Krause’s clothes and provide an additional stipend for his boarding “because the boy does quite a good job in his trade already.”[37] Records regarding compensation are confusing, but it appears that Aust initially paid his journeymen by the piece. In September 1775 the Collegium noted that “it would be well for some masters, especially Br. Aust, to take care that his workers earn no more in their piece work than he, . . . [Aust] should give less money . . . and . . . sell his ware cheaper. Up to now it has been both very expensive and bad.”[38] Aust probably implemented this system of payment because a “long drawn-out illness” prevented him from supervising work at the pottery.[39] He may have instructed workmen to inscribe price marks on their wares at this time. Bethabara dishes are typically marked with Arabic numerals, whereas those attributed to Salem are usually marked with script letters (fig. 24).

The Salem Pottery during Aust’s Tenure as Master

In July 1773 the Helfers Conferenz reported on a proposal “to place proper signs at the houses of the tradesmen, store and tavern in order that strangers could find them more easily. Such signs should have the name of the master and the trade.”[40] The only sign that survives from this period is a massive example made for Aust’s shop (fig. 25). Measuring more than twenty-one inches in diameter, it is the most elaborate and technically complex piece of Germanic earthenware from colonial America. More important, it represents a benchmark for identifying slipware produced by Aust and the tradesmen under his supervision.

While the body of the shop sign was in a leather-hard state, the maker used a variety of edge tools to carve out the letters, date, floral motifs, geometric designs, and scrollwork on the marly, or flat part of the rim. Concentric lines generated on the potter’s wheel regulated placement of the letters and dates, but the scrollwork was done freehand, with numerous alterations made in the process (fig. 26). After completing that work, the maker coated the front of the sign with red slip, filled in all of the cuts on the marly with contrasting slips, and decorated the cavetto. Marks from the bone or quill stylus of his slip cup are clearly visible in the broad areas of white and green (fig. 27). If the maker used a brush or other implement to spread the slip, he left no evidence behind.

Like the teawares excavated at Bethabara, Aust’s shop sign attests to the cosmopolitan nature of Moravian ceramics. The cavetto decoration shares details with the enameling on a French faience dish from the late seventeenth century (fig. 28).[41] Motifs found on this class of Nevers ware were derived largely from Chinese, Persian, and Iznik ceramics. On the shop sign and Nevers dish, Eastern motifs occur in a structured composition reminiscent of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century flower paintings and prints (fig. 29). The inclusion of a bird in each cavetto design is significant, since avian subjects are common on Islamic ceramics.

Iznik pottery entered German collections during the last quarter of the sixteenth century. In 1577 David Ungnad, ambassador of Maximilian II (r. 1564–1574) to the court of Sultan Murad III (r. 1574–1595), wrote to the bishop of Salzburg urging him to purchase Iznik tiles. Four years later Johann Friedrich, margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, acquired an Iznik tankard and had it fitted with a mount engraved with his coat of arms and the inscription “Zu Nicea binich germacht / Und nun gen Halle in Sachsen bracht / Anno 1582” (In Nicea I was wrought / And now to Halle in Saxony brought / in the year 1582).[42] Iznik designs were also disseminated through the shipment of Italian maiolica derivatives to northern European cities, particularly those in Germany.[43] Perhaps Aust never saw pottery from the Ottoman Empire, but it is quite likely that he came into contact with European decorative arts that had been influenced by Iznik ceramics.[44]

Several dishes and plates can be attributed to the Salem pottery based on similarities between their decoration and that on Aust’s shop sign. The dish illustrated in figure 30 is typical, having a double-bouge profile, undercut rolled rim, and price mark incised on the bottom. Not all surviving objects are marked (see fig. 24), which suggests that pricing was done sporadically throughout Aust’s tenure but implemented as policy when circumstances demanded. When Aust went to Bethlehem for medical treatment in 1788, the Aufseher Collegium directed that “the price of each piece of pottery shall be burnt into it in the future and those that are not ready shall be marked with red chalk. Several examples of cheating and profit making were quoted as proof of how necessary a good supervision will be.”[45] As is the case with this dish, most Salem examples with white grounds are made from buff-colored clay. In contrast, the shop sign and most dishes coated with red slip are made of pink clay. That material might have come from the same source as the buff variety, since veins of clay are often inconsistent in color and composition.[46]

Most of the dishes associated with Aust’s tenure as master of the Salem pottery have cavetti with naturalistic flowers trailed in two, three, or four colors of slip (figs. 30-32). As the complex fernlike leaves and flowers on these objects reveal, he and his workmen were masterful in their application of slip. On the dish illustrated in figure 32, the manganese-colored slip outlining the leaves and seedpods looks almost as if it were applied with a calligraphy pen (fig. 33). The plant in the center may have been inspired by a woodcut (fig. 34), engraving, or illustration from one of the many florilegia in circulation at the time. These compilations of botanically accurate images were an important design source during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries for decorators of European pottery and porcelain.

Several versions of the dish illustrated in figure 32 survive in both fragmentary and intact form. Two examples have buff-colored bodies and white slip grounds (figs. 35, 36), whereas a very similar dish that descended in a local Moravian family is made of pink clay and has a red slip ground (fig. 37). The dishes shown in figures 35 and 37 have leaf motifs that match those on sherds excavated in Salem (figs. 38, 39). Their cavetto decoration is distilled in two nine-inch plates attributed to the Salem pottery (figs. 40, 41). All of the surviving slipware plates made there are approximately nine inches in diameter, whereas dishes typically range from eleven inches to just over fifteen inches in diameter.

During his tenure as master of the Salem pottery, Aust took at least nine apprentices. Records of the Aufseher Collegium indicate that his relationship with these young men was often turbulent. Some apprentices were simply troublemakers: Heinrich Beroth was a “gossip”; Franz Stauber and Gottlob Krause were prone to committing mischievous acts; Ludwig Möller was reckless and obstinate; and Jacob Meyer’s “bad way of life” ultimately led to his expulsion from the community.[47] Even Aust’s most responsible apprentice, Rudolph Christ, was often arrogant and rebellious. According to the master potter, Christ was a “stupid ass, like other children in the Community.”[48] Nevertheless, the Collegium held Aust partially responsible for problems at the pottery and complained that his lack of supervision created opportunities for “evil doings.” One report notes, “the boys have too much freedom about the selling of the wares.”[49] The thought of these young men doing business on the side was particularly vexing to the Collegium.[50]

Aust may have been a poor manager, but there is no evidence that he relinquished control over the types of ware produced while he was master. In fact, all of the major slipware objects that can be linked to Salem or Bethabara through family histories or archaeology resemble Aust’s work in both form and decoration. This should come as no surprise, since he trained most of the potters active in Wachovia during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The Salem pottery produced a wide variety of slipware dishes and plates, ranging from relatively austere examples with sketchy plant forms (figs. 42, 43) to the more complex and technically demanding example shown in figure 44, yet all of these wares are remarkably similar in form and finish. Bivins developed a chronology in which he separated dish profiles into three phases of production—early period (1756–1773), middle period (1774–ca. 1789), and late period (ca. 1789–1829)—but archaeological fragments and intact objects suggest that the variations he observed reflect the individual habits of Aust and his workmen more than change over time.[51] Also skewing Bivins’s interpretation are the many dishes he attributed to Salem that in fact were made by potters working in present-day Alamance and Randolph counties.

The English Fabrique

Shortly after Aust moved to Salem, the pottery began producing imitations of Staffordshire earthenware.[52] On December 8, 1773, the Aufseher Collegium reported:

In the evening we considered what we are to do about a stranger journeyman potter by the name of [William] Ellis. He came here of his own accord with our wagon from Charlestown. . . . This man knows about glazing and firing Queens Ware. The Collegium therefore approves Br. Aust’s proposal that under this man’s supervision . . . a kiln suitable for firing such ware be put up in Br. Meinung’s yard, which adjoins Br. Aust’s. [Ellis] . . . is to receive a small payment in return along with food and laundry. . . . It should be noted that the art of making this pottery ware . . . had for the most part been disclosed to Br. Aust about two-and-a-half years ago by just such an itinerant painter-potter, although he had not been invited to do so. And since Ellis comes to us of his own accord now, we certainly have to regard the matter as a direction from the Most High that this art should be established here.[53]

Both Ellis and the “itinerant painter-potter” who preceded him had worked for John Bartlam, a Staffordshire potter who operated manufactories in Cain Hoy (1765–ca. 1770), Charleston (ca. 1770–ca. 1772), and Pinetree (Camden) (1774–ca. 1778), all in South Carolina.[54] According to Wachovia administrator Frederic William Marshall, the Salem pottery had been producing finer work, “similar to . . . queensware,” since the arrival of the first Bartlam journeyman in 1771.[55] Aust’s initial efforts probably entailed coating thrown forms with white slip and decorating them with tortoiseshell colors, although dating surviving examples of this class of ware is problematic since it was produced over a long period of time (figs. 45-48). Under Ellis’s supervision, Aust and his journeymen succeeded in manufacturing more refined variants (see fig. 48). On April 5, 1774, Marshall reported:

[T]he potter from Pinetree . . . has made a trial burning of Queensware, also another with Stoneware, whereby the processes necessary for it are pretty well made known to us. But since all of these wares now have to be made on the pottery molds by hand and are not turned on a potter’s wheel with instruments, they obviously do not have the porcelain standard of delicateness, but they do serve as a sideline for our pottery, for recommendation and further development. For the good man himself [Ellis] this was finally too narrow and so for the present he took a friendly departure.[56]

Inventories of the Salem pottery shed light on what Marshall referred to as the “English Fabrique.” In April 1774 Aust recorded expenditures of £10 to “Billy Ellis for work” and £7.17.3 for “a new kiln.” On hand were all of the materials needed to produce stoneware and creamware: three wagonloads of white clay valued at 2s.; twelve pounds of “Burnt Copper” valued at £1.4; one hundred pounds of “Manganese + Iron Color” valued at £5; and three hundred pounds of lead “Glazing.”[57] The white clay used at the Salem pottery could withstand extremely high temperatures, but there is no mention of salt, soda, ash, or any other glaze material commonly associated with stoneware. It is possible that the stoneware mentioned in the earliest records was lead-glazed. This would have required two firings, one at high temperature to achieve vitrification, the other at a lower temperature to bond the lead glaze. Ellis certainly would have been familiar with this practice, since in England it was employed in the production of tin-glazed stoneware.[58]

Marshall’s April 5, 1774, report noted that the pottery made under Ellis’s supervision was not thrown, but only pipe and stove plate molds are listed on inventories surviving from the 1770s.[59] The earliest reference to molds for hollow ware is in the January 27, 1779, minutes of the Aufseher Collegium: “Brother Aust testified that Christ behaved honestly, however, that he . . . carried away last week out of the pottery several forms [sprig molds for handles] which are used for the flowers for the fine pottery” (fig. 49).[60] Fourteen months later, Aust listed “12 plate molds of clay” among the “things and tools” at the pottery.[61] It is possible that Ellis brought a variety of molds to Salem, then took them with him when he left town. He might also have had a potter’s lathe. Several mug fragments likely made during Ellis’s visit have uniformly thin walls and fine concentric marks, indicating that they were turned on a lathe.[62] In contrast, all of the imitation creamware vessels surviving aboveground are thrown forms with slip grounds and either pink or buff-colored clay bodies. Aust and his successors might have had difficulty producing refined creamware and stoneware after Ellis’s departure.

Aust appears to have had limited interest in making “fine pottery,” but that was not the case with Christ. On September 12, 1780, the Collegium reported:

Br. Christ . . . would like to start the fine pottery here in the community. The fine pottery cannot be manufactured together with the rough pottery, because the finest grain of sand that comes into the white clay, will do great damage, and as concerns the drying, just the opposite has to be done with the one than the other. Thus he would need his own pottery and new tools. . . . If it would not cost too much money we could then maybe erect a house and some buildings for it and he could maybe follow the trade better than it has been done up to now, he could then also take up the manufacturing of white, black, and salt pottery. It would also be good to get him away from Br. Aust because the two temperaments are too different to get along with each other.[63]

This reference indicates that Ellis taught the Moravians how to make blackware (fig. 50) in addition to salt-glazed stoneware and creamware but that production of these ceramic types had been disappointing. Over the next five years Christ submitted several petitions to establish a second pottery for that purpose in Salem or Bethabara. Meanwhile, his relationship with Aust deteriorated. The Collegium attempted to mediate and convinced the two men to enter into a contract whereby Aust agreed to “make his pottery—excluding . . . pipe heads—only from non-washed clay” and Christ agreed to “make no other kind of pottery but that from washed clay, which may be glazed with all sorts of colors.” This arrangement remained in effect from March 21, 1782, until February 10, 1786, when Christ moved to Bethabara.[64]

Rudolph Christ and the Second Bethabara Pottery

One month after he and his wife moved into the gunsmith’s shop at Bethabara, Christ asked for “a boy to help in his pottery shop.” The Aeltesten Conferenz agreed that he could take Johannes Leinbach if the boy could be “lodged according to congregation rules,” although there is no evidence that the apprenticeship occurred.[65] By May 22, 1786, Christ had constructed a kiln and fired a load of pottery. According to an entry in the Bethabara Diary, “Br. Christ made his second burning last week, and took the earthenware from the kiln today. It turned out well.”[66] (The phrase “second burning” refers to the “glaze firing” of bisque ware.) The following November the Aufseher Collegium reported: “Dan Christman is selling pottery ware of Christ in Bethabara. Br. Praetzel is going to talk to him and see that he stops it.”[67] Christ’s lack of help may have prompted him to seek other retail outlets so he could focus on production. Only two workers are associated with his Bethabara pottery. On December 22, 1786, the Collegium gave David Baumgarten (b. ca. 1774) permission to work with Christ on a trial basis.[68] Two years later, the “Negro Peter Oliver was sent to Bethabara to work in Br. Christ’s pottery.”[69]

Christ’s tenure at Bethabara was short. In January 1789 he requested permission to “take over the pottery in Salem as master . . . on the same terms as the late Br. Aust,” who had died the preceding October.[70] The Collegium agreed to pay Christ one-half of the net profits and added that:

He could bring along his apprentice David Baumgarten, however he would have to leave his Negro [Oliver] there, since he wants to marry, which is unfitting for the community here. His stock and all his implements there . . . he is going to sell . . . and Br. Gottlob Krause is inclined to take it over and also the Negro whose value has grown since he has learned so much from Br. Christ at the pottery. . . . [Christ] is going to bring over his stock of fine pottery, because we do not have any here and Gottlob Krause cannot do anything with it. . . . This stock of fine pottery should be inventoried here, not according to the sale price, but according to the inventory. . . . [Christ] is also going to bring his glazing mill here and is going to offer the one they have here to Br. Krause.[71]

This reference and the “Account of finished ware . . . delivered . . . to the Salem Pottery” shed light on Christ’s production at Bethabara. Most of the pottery he brought to Salem was described as “fine,” a term the Moravians typically applied to ceramics in the English taste. Listed on the inventory were two sizes or models of “small plates,” ten of “decorated plates,” seven of “bowls,” two of “sugar bowls,” two of “tea pots,” two of “water jugs” (pitchers), six of “bottlers,” two of “quart mugs,” and two of “half-pint mugs.” Christ also produced “barber pans” and pint mugs, but in only one size or model. The total value of the pieces of pottery he brought from Bethabara was £75.8.4. The inventory also lists forty plate molds (figs. 51, 52), suggesting that the 662 “decorated plates” were imitation creamware examples with tortoiseshell glazes.[72] Christ probably made the molds at Bethabara, since the twelve clay examples listed in Aust’s inventory of March 1780 were in the Salem pottery when Christ returned to town.[73]

Archaeology at the site of Christ’s pottery at Bethabara supports the theory that he was engaged primarily in the production of fine pottery there. Sherds and partially intact objects conform to many of the ceramic forms listed in the inventory of wares he took to Salem. The press-molded dish illustrated in figures 53–55 is typical in its light pink clay body and brown, iron-bearing glaze on the back as well as the white slip with variegated underglaze decoration on the front. All of the hollow ware recovered at the site appears to have been finished on the wheel rather than on a potter’s lathe. Some examples are extremely thin and refined, whereas others are “rough pottery” decorated with tortoiseshell colors.

Christ also made simple but elegant utilitarian earthenware and Germanic slipware at Bethabara. Dish sherds discarded at his pottery site are similar to those documented and attributed to Aust, featuring rolled undercut rims and naturalistic plant designs in the cavetto. A fragmentary dish from one of Christ’s kiln wasters had at least two different flower heads, one terminating in a slip-trailed squiggle and the other resembling a tulip bud (fig. 56). This bud motif is repeated on a cavetto sherd from the same context (fig. 57) as well as on several dishes attributed to the Salem pottery. Sherds from the cellar of the gunsmith shop might also represent Christ’s work. The example illustrated in figure 58 has a central stem with stylized, comma-shaped leaves like the fragmentary dish from his waster (see fig. 56). Although Gottlob Krause occupied Christ’s site for a few months, the trailing on most of the slipware excavated there differs from that documented to Krause (see figs. 69, 70).[74] Equally important is the fact that none of the material recovered at Christ’s site features the highly stylized geometric motifs traditionally ascribed to him. This supports the theory that potters working outside the Wachovia tract were responsible for nearly all of the Germanic slipware formerly attributed to Christ.

The Salem Pottery during Christ’s Tenure as Master

On January 26, 1789, Christ signed a contract to take over the pottery for the Salem Diacony.[75] That same day the Aufseher Collegium made plans to “talk to the journeymen and apprentices about their relationship to the new master.”[76] The pottery workforce included Franz Stauber, who was about to complete his apprenticeship, and Philip Jacob Meyer.[77] In 1790 Christ took John Butner as an apprentice, leaving him with two potters who had trained under Aust plus David Baumgarten, who had begun his apprenticeship with Christ at Bethabara.[78] This was fortuitous, because Meyer left the community in 1789 and Stauber moved to Bethania four years later.[79] The former established a pottery at Mount Shepherd in Randolph County, North Carolina, and the latter continued his trade in an area that became known as “Stauber-Town.”[80] During the 1790s, when he was developing “new lines” of pottery, Christ took two more apprentices—John Frederic Holland in 1796 and Joseph Stockburger in 1797. Holland eventually succeeded Christ as master of the Salem pottery.[81] The only other apprentices associated with Christ are Samuel Benjamin Wagemann and Samuel Schultz, who began serving their terms in 1802 and 1806, respectively.[82]

The inventories of the pottery taken while Christ was master are not specific enough to determine how much “fine ware” was made relative to “rough ware,” but these documents reveal that he began making new bottle forms (see “Moravian Press-Molded Wares” by Johanna Brown in this volume) and faience after 1793. The catalyst for Christ’s initiatives was Carl Eisenberg, a journeyman potter who arrived in Salem probably by April 1793.[83] The “Outlay of the Pottery” taken on May 30 of that year lists £15 for board and “a month’s wages” for Eisenberg. Other expenses enumerated in the same document include £12.2 for “hauling stones for the kiln,” £9.4.6 for 4,100 bricks, £1.7.1 1/2 for 325 large bricks, £1.8 for 400 feet of boards, £14.8 for a roof and shed, and £5.3.4 for masonry work.[84] On July 2, 1793, the Aufseher Collegium reported, “Brother Christ would like to build a small burning oven as several sorts of pottery do not burn hard enough in the usual burning oven.”[85] Given the fact that tin-glazed earthenware fires at the same temperature as lead-glazed earthenware, Christ clearly envisioned other uses for this kiln. Two months later Frederic William Marshall wrote, “In the Salem pottery, a new kiln has been built for faience, though we do not know how well it will work, as it has not been tried. Usually new lines draw new customers, and there are potters enough around us where they would otherwise go.”[86] According to the minutes of the Collegium, the kiln was to be only eight feet in length and located on Lot 39, across the street from the pottery.[87]

Eisenberg undoubtedly supervised the construction of the faience kiln. The Collegium agreed that he could remain in Salem as long as “his behavior is good,” but there is no record of him receiving a salary after May 1793.[88] Eisenberg might have left the community the following autumn. A manuscript document titled “A Collection of Faience Glaze Recipes as well as All Sorts of Paint Colors and How They are to be Processed” and subtitled “A Collection of Carl Eisenberg’s Faience Glazes along with Various Paint Colors” is inscribed “Salem. October 26, 1793.”[89]

Materials for producing faience first appeared in the April 30, 1795, inventory of the Salem pottery: 70 lbs. of soda, 2 bushels of gypsum, 1,400 lbs. of lead glaze, 100 lbs. of silver litharge, 8 lbs. blue smalt (cobalt), 5 lbs. of Naples yellow (lead antimony), and 25 lbs. of tin.[90] With these components—and the copper, iron, and manganese traditionally on hand—Christ had the capability to make a range of white, black, blue, green, yellow, and red glazes and underglaze enamels (or “paint colors,” as the 1793 manuscript called them). Eisenberg’s formula for “sea green” glaze, for example, included lead and tin ash, soda, potash, sand, salt, copper scale, pipe clay, coarse smalt, and silver litharge.[91]

Sherds recovered at Lot 49, which was across the street from the faience kiln in Salem, document the production of thrown ring bottles (which Christ may have called “sack bottles”) and other forms with “sea green” glazes (fig. 59), and press-molded dishes with white and pale blue glazes and blue chinoiserie decoration (fig. 60). The 1796 inventory of the pottery lists 224 bottles at five different prices.[92] Ring bottles smaller than the faience examples with conventional brown and green glazes are known (fig. 61). The production of tin-glazed earthenware apparently continued throughout Christ’s tenure as master. When John Holland took over the pottery in 1821, the transition inventory listed jars containing white, blue, green, yellow, and black faience glazes.[93]

Christ’s production of faience coincided with his renewed effort to make stoneware, which would have required a kiln like that mentioned in the July 2, 1793, minutes of the Aufseher Collegium. Two years later, in 1795, the Collegium reported, “Br. Christ showed us a sample of stoneware which has been made in our pottery shop, and we all were glad that the first firing came out so well.”[94] The fact that salt does not appear on inventories until 1809 suggests that Christ’s stoneware was coated with a tin glaze in a second low-temperature firing, or a slip or alkaline glaze in a single high-temperature firing.[95] The only alkaline listed in the 1795 inventory is soda.[96] Although essential for the production of faience, soda also can produce a glaze similar to salt.

Paralleling the development of new pottery lines to draw new customers, Christ and his workmen continued to produce Germanic slipware. On three dishes made while Christ was master, the marly is decorated with wavy lines and dots (figs. 62-64), a pattern likely inspired by the decoration on British pearlware from the 1790s.[97] Sherds recovered near the site of the pottery document the production of other neoclassical borders, including one with husks (fig. 65). The dish illustrated in figure 62 has the most complex cavetto decoration, which consists of twisting leaves and ovoid flowers with jeweled edges. The arrangement and form of the leaves, which are similar both to those on Aust’s shop sign (see fig. 25) and to sherds recovered at Salem (fig. 66), attest to the strong stylistic imprint Aust left on Wachovia work. The same can be said of the dishes illustrated in figures 63 and 64, which appear to have been decorated by the same hand.

A fragmentary slipware dish recovered at Lot 49 has wispy leaves and embrocated triangles on the marly (fig. 67). Related motifs occur on sherds with the same provenance, as well as earlier examples recovered at Aust’s Bethabara site (fig. 68). In Wachovia slipware, stylized decoration appears to have been limited to comma-shaped leaves on the cavetti and marlys of dishes. Abstraction remained a distant second to naturalism in the Moravian slipware tradition, an assertion supported by dish and plate sherds recovered from Bethabara sites occupied by Christ and Krause.

Gottlob Krause at Bethabara

On April 3, 1781, Gottlob Krause completed his apprenticeship and began working as a journeyman for Aust in Salem. Unhappy with his wages and unable to convince Aust to pay him on a piecework basis, Krause left the pottery and became a mason and brickmaker.[98] In June 1785 he petitioned the Aeltesten Conferenz to “give up his mason trade” and “intimated that he would like to carry on the pottery at Bethabara.” The Collegium refused, noting that Krause “has invested so much in his brick manufactory . . . and he can do so much better [in the masonry trade] than in setting up a pottery in Bethabara.”[99] During the next four years Krause followed a “bad way of life.” Complaints against him ranged from employing an outsider of “ill repute” to “trading and bargaining against the orders” of the community and theft.[100] Just before he was to be excluded from Salem, the Salem Diary recorded that Krause and his family could move to Bethabara, “where he will take Br. Christ’s former pottery on his own account.”[101]

The minutes of the Collegium suggest that Krause spent much of his time during the 1790s doing masonry work and making bricks and tiles. He built the Boys School in Salem between 1793 and 1794, the Christoph Vogler House in 1797, the Bakery in 1800, and the Benjamin Vierling House in 1802. Krause also provided bricks and roof tiles for all of these projects.[102] Most of these materials were fired in the brick kiln that Krause rented from Johann Heinrich Blum in Salem.[103]

Krause may have left his slave Peter Oliver in charge of the Bethabara pottery while working on the Boys School. Although Oliver was obviously a valuable tradesman, Krause sold him to Johann Jacob Ernst in September 1795.[104] The only other workmen associated with Krause’s pottery are Johann Heinrich Feiser, who began serving his apprenticeship in 1795, and Joseph Sturges, a journeyman who in May 1795 “returned . . . to Pennsylvania after working for some months as a potter.”[105] Since Krause spent much of his time in Salem during the 1790s, it is possible that a significant percentage of the pottery associated with him represents the work of Peter Oliver.

Krause worked at Christ’s former pottery from January to November 1789, when he purchased a house formerly occupied by Johannes Schaub Jr. at Bethabara.[106] Archaeology performed at the latter site yielded fragments of finely thrown slipware dishes and plates with naturalistic plant motifs in the cavetto and stylized leaves on the marly (figs. 69, 70). Objects with related decoration were also found at the Christ-Krause site and in a pit outside the original palisade wall.

Moravian Potters on the Periphery of Bethabara and Salem

In his September 1793 report to the Unity Vorsteher Collegium, Frederic William Marshall cited competition from “potters . . . around us” as justification for developing faience and other new lines of ware.[107] That same month, the Friedberg Diarist wrote, “I visited Br. Philip Rothrock, and found that his son Friedrich has begun to make pottery, and has had good success with a small burning.”[108] Friedrich’s pottery was in Friedland, a small Moravian community less than five miles south of Salem. Although his site has been destroyed, two slipware dishes (figs. 71, 72) and a lead-glazed jug (fig. 73) bearing Friedrich’s stamped mark (fig. 74) survive. The dish illustrated in figure 71 originally belonged to his brother George, whose slip-trailed initials are on the front. John Bivins speculated that Friedrich trained with Aust, although there is no reference to that apprenticeship in the Salem records.[109] If Rothrock did not train in Salem, he was profoundly influenced by the slipware made there.

As demonstrated in “The Mount Shepherd Pottery Site” by Alain Outlaw in this volume, the slipware made by Philip Jacob Meyer in Randolph County bears an even stronger resemblance to Aust’s work. Meyer began serving his apprenticeship with Aust in 1786.[110] When Aust left Salem for medical treatment in Pennsylvania two years later, Meyer was left in charge of the pottery.[111] He appears to have been inadequate for the task, for in December 1788 the Aufseher Collegium noted: “At the . . . last burning . . . Jacob Meyer heated the kiln too much so that most of the pottery is cooked.”[112] After being excluded from Salem for intolerable behavior in the fall of 1789, Meyer moved in with his brother-in-law Gottlob Krause at Bethabara.[113] It is possible that Meyer worked in Krause’s shop, but documentation is lacking. According to the February 3, 1791, minutes of the Congregation Council, “Br. and Sr. Meyer have [been living at] Bethabara for some time . . . and are going to help Br. Gottlob Krause with his household and the education of his children.”[114] By October 3, 1793, Meyer had moved to Mount Shepherd in Randolph County. Although the date he established his pottery is not known, he apparently worked at that site until 1799.[115]

The ceramic tradition of the Moravian potters is remarkable for its complexity and high level of technical and artistic achievement, yet most of the wares they produced were utilitarian. The unruly crowds of outsiders that routinely attended kiln openings were far more interested in the utilitarian crocks, milk pans, storage vessels, and tableware than decorative slip-trailed dishes. Indeed, archaeology conducted at Moravian sites suggests that the production of earthenware with tortoiseshell glazes in the British style might have exceeded that of pottery with Germanic decoration during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. The slip-trailed wares did, however, have symbolic meaning within the Moravian community, whereas pottery in the “English fabrique” was largely commercial.

Meaning and Metaphor in Moravian Slipware

In an essay titled “The Inescapable, Indivisible Essence of Pottery,” ceramic critic Warren Frederick argues that historic “pottery’s potency lies in its resolution of dual realities.” The utilitarian nature of pottery has remained relatively unchanged for more than ten thousand years. Like our ancestors, we use pottery for storage, consumption of food and drink, and many other activities of everyday life. Since the first clay vessels were hardened in fire, pottery has also delineated status, conveyed offerings in ritualistic or religious ceremonies, and functioned symbolically within different belief systems. As Frederick notes, pottery’s language can be direct, metaphorical, or both. In his view, “the utilitarian, spiritual, and aesthetic qualities of ceramics are forever intertwined.”[116]

In many religions, pottery is a metaphor for creation. According to Genesis 2:6–7, “mist came up from the earth and watered the whole surface of the ground. And the Lord God formed the man from the dust of the ground. . . .”[117] Similar metaphors are in Jeremiah 18:3–6 (“So I went down to the potter’s house, and, I saw him working at the wheel. But the pot he was shaping from the clay was marred in his hands; so the potter formed it into another pot, shaping it as seemed best to him. Then the word of the Lord came to me: . . . Like clay in the hand of the potter, so are you in my hand. . . .”), Job 10:8–9 (“Your hands shaped me and made me. Will you now turn and destroy me? Remember that you molded me like clay. Will you now turn me to dust again?”), and Isaiah 45:9 (“Woe to him who quarrels with his Maker, to him who is but a potsherd among the potsherds on the ground. Does the clay say to the potter, ‘What are you making?’ Does your work say, ‘He has no hands’?”). These passages were undoubtedly the source of several inscriptions on eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Pennsylvania sgraffito ware, including “Die schisel ist von erd und don / Und die Mensch auch davon” (This dish is made of earth and clay / And the men are also thereof) and “Aus der ehrt mit verstant macht der Haefner aller hand” (From the earth with sense the potter makes everything).[118] Pennsylvania potters occasionally chose decorative motifs that reinforced the messages of their inscriptions. On a dish attributed to Montgomery County potter George Hubener, the phrase “Blummen Mollen ist gemein aber den geruch zugeben ver mach Nur Gott Allein” (Painting flowers is common, but giving them an odor is given to God alone) encircles a cavetto design featuring a flowering plant surmounted by a bird (fig. 75).[119]

Flowers have long been used to represent the transience of life in the visual arts. This metaphor can be traced to 1 Peter 1:24–25, which states: “All men are like grass, and all their glory is like the flowers of the field; the grass withers and the flowers fall, but the word of the Lord stands forever.” Dutch artist Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) alluded to the inevitability of death when he included a skull, hourglass, and tulip in his 1614 pen-and-ink drawing Youth with a Skull and a Tulip (fig. 76). The inscription under the hourglass reads: “QUIS EVADET / NEMO” (Who escapes / No one). Art historians traditionally have viewed the great flower paintings of the seventeenth century from a similar perspective. Both the flowers and the container holding them are fragile, signifying the ephemeral nature of worldly things. George Hubener used similar metaphorical conventions on a dish inscribed “Kan mich kein Pflaster heilen, So Wolst du Mit eilen, Aus dieser Jammer welt ins schoene Himmels elt” (No plaster can heal me, so you will want to hurry with me from this world into the canopy of heaven). The flowers in the cavetto, their earthenware container, and Hubener’s dish itself allude to impermanence (fig. 77).[120]

Flowers had religious connotations and associations with specific virtues centuries long before the Moravians came to the colonies. An exceptional late-fifteenth-century painting by Hans Memling (ca. 1430–1494), a German-born artist who worked in the Netherlands, depicts flowers associated with the Virgin Mary—white lilies, irises, and columbines—in an earthenware altar vase (fig. 78). As Beatrijs Brenninkmeijer-De Rooij has noted, the late medieval cult of the Virgin “defined virtues as flowers in a garden.”[121] One of the most commonly cited flower metaphors in the Judeo-Christian tradition is Song of Solomon 2:1: “I am a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys.” Since the Middle Ages, the female voice in that verse has been interpreted to be the bride in an allegory of marriage of the church and soul to Christ.[122] The Song of Solomon had a profound influence on German literature, music, and material culture. Lyrics from the “Song of the Lilies,” a hymn sung at the Ephrata Cloister in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, refer to “The heavenly drama, the perfume of lilies / Awakened anew the Spirit’s desire; The Roses of Sharon, though low on the ground / Bring heaven to spirits for the covenant bound.” Flower metaphors were also present in the writings of German mystic Jacob Boehme (1575–1624), who had a profound influence on Zinzendorf’s theology, and the poetry of Angelius Silesius (1624–1677), whose work influenced Moravian hymns.[123]

An illuminated manuscript commissioned by Frederic William Marshall in 1775 provides compelling evidence that Moravians understood that symbolic art could be a powerful expression of religious beliefs (figs. 79, 80). There, Christ’s blood saturates the ground beneath a flourishing grapevine whose leaves depict the many Moravian congregations around the world. Inspired by John 15:5—“I am the vine; you are the branches. If a man remains in me and I in him, he will bear much fruit; apart from me you can do nothing”—the visual metaphor of the manuscript was obvious to Moravians and did not require descriptive text.