Creampot, Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, 1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/8". Inscribed: “Henry Shafner in Salem NC Stokes County June 14 1834”. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.) This creampot was thrown by Heinrich Schaffner after digging his first clay in Salem. It is signed with his anglicized name.

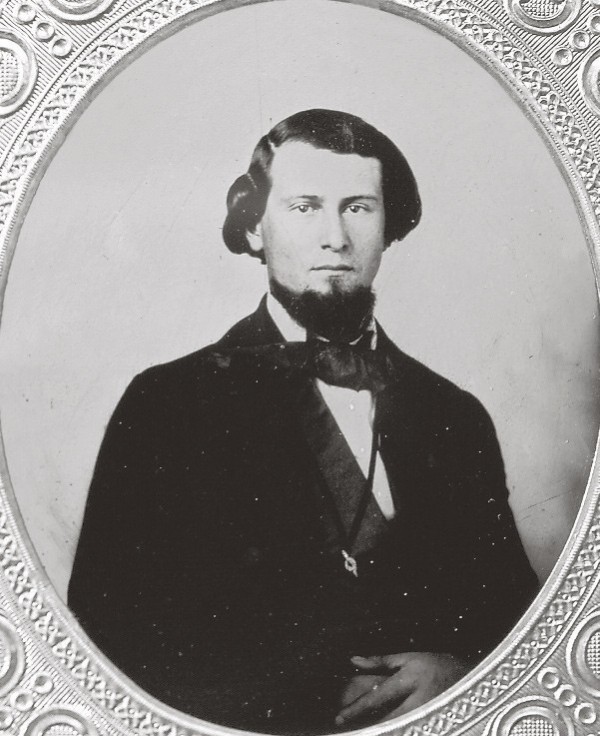

Albumen print of Heinrich Schaffner by Alanson E. Welfare, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1865. (Courtesy, Moravian Archives.)

Tintype of Daniel Krause by unknown photographer, ca. 1865. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Kiln ruin, Schaffner-Krause pottery site, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 2003. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Michael O. Hartley.) Shown is a plan view of kiln remains at site, excavated by Old Salem Archaeology in the 2000–2003 field seasons. The firebox, which extended into the dryhouse, is in the choked-down area at the left, and the rectangular body of the kiln extends to the right. The lower arm of the kiln body is partially missing.

Excavation of kiln ruin, Schaffner-Krause pottery site, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 2003. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Michael O. Hartley.) An archaeology student cleans the firebox of the Schaffner-Krause pottery kiln.

Photograph by E. F. Small of the Schaffner-Krause pottery, Winston, North Carolina, 1882. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The pottery shop, which is at the left, was the first constructed building in Salem. Known as the “Builders’ House,” it was built in 1766 for the men from the nearby Moravian towns of Bethabara and Bethania who came to build the new town of Salem. Schaffner obtained permission to use this building in 1834 and constructed his pottery operation. The kiln is in the center of the photograph, and at the far right it attaches to the end of the dry house; note doorway into the dry house. A pug mill is in the foreground.

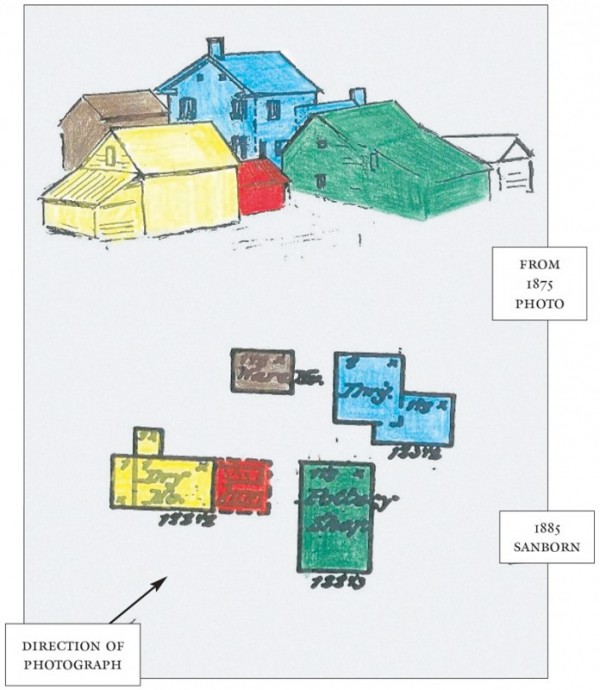

Schaffner-Krause pottery complex, as recorded on the Sanborn Insurance Map for 1885 and in a sketch made from a pre-1873 photograph. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo and artwork, Michael O. Hartley.) The pottery shop is shown in green, the kiln in red, the dry house in yellow, and the warehouse in brown. The dwelling, indicated in blue, was constructed in the 1860s to replace Schaffner’s original house, which burned in 1863.

Creampot, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This nineteenth-century creampot follows the same basic form as eighteenth-century creampots manufactured in Salem and Wachovia. Unlike Schaffner’s creampot of June 14, 1834, illustrated in fig. 1, this example is glazed only on the interior, as was typical.

Flat-bottom cookpot with three legs, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The three legs on this basic flat-bottom form allowed this version to be used for hearth cooking over a bed of coals.

Flat-bottom cookpot with double handles, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This Schaffner-Krause cookpot utilizes the double-handle form seen on the three-legged cookpot illustrated in fig. 9, minus the legs.

Flat-bottom cookpot with single handle, Salem, North Carolina, 1834–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Contemporaneous with the cookpots illustrated in figs. 9 and 10, this third variation of the flat-bottom form was excavated at the Herbst House site in Salem and quite possibly was manufactured at the Schaffner-Krause pottery.

Apothecary jar, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Earthenware. H. 8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Flowerpots, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Earthenware in bisque with slipped coating. H. 3 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These two examples were among several flowerpots recovered at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site.

Acanthus-leaf mold and stove tile fragment, attributed to Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. H. 31/2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society [mold] and Old Salem Museums & Gardens [fragment]; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

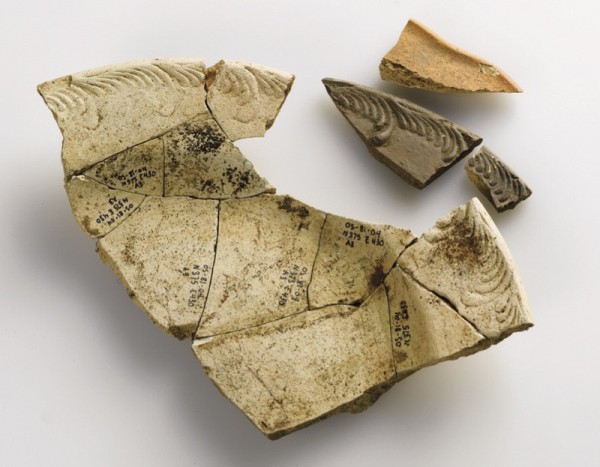

Reassembled portion of a feather-edged plate in buff bisque, two additional feather-edged fragments from a different mold in brown bisque, and a Royal-pattern sherd in orange bisque, Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware. Approximate projected D. of reassembled plate 8 1/2". Impressed on underside of reassembled plate: H.S. / SALEM / NC. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) All of these fragments were recovered from the Schaffner-Krause pottery site.

Bottom of the reassembled portion of the feather-edged plate illustrated in fig. 15. Schaffner’s stamp clearly demonstrates his production of creamware forms.

Hollow ware lid fragment decorated with sprig molding, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware. Approximate projected D. 4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This fragment provides further evidence that Schaffner’s pottery produced English-style ceramics.

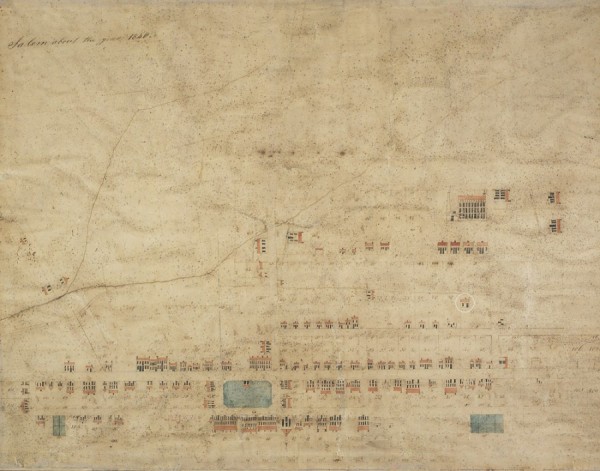

Salem about the year 1840, by unknown mapmaker. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) In 1834 Heinrich Schaffner established his pottery operation at the Builders’ House, constructed in 1766, which had been used as a residence. The large building shown west of the pottery is the 1836 Salem Manufacturing Company, an early cotton mill.

Left: Owl bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 3/4". Right: Reconstructed fragment of the base of a bird bottle, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Left: Animal paw fragment, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware. Right: Squirrel bottle, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The paw fragment was recovered at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site.

Molded animal head, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware. L. 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Left: Flowerpot handle fragment, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Right: Lion’s-head mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1850–1870. Plaster. H. 5". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) The provenance of the lion’s-head mold is unknown; however, the handle fragment was cast in it or in a similar mold.

Slip-trailed decorated sherds, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware with slip decoration. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.) These sherds have been decorated with slip trailing but have not gone through the glost firing. Their discovery at the pottery site confirms the manufacture of these wares at the Schaffner-Krause pottery.

Pint cup, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware with a slip coating. H. 3 1/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This cup, which has been bisque fired and coated in a white slip, is an unfinished example from the Schaffner-Krause pottery; it is very similar to products made by eighteenth-century Moravian potters.

Plate, bottom view, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Bisque-fired earthenware. D. across top 9 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.) Warped through overfiring, this plate is an example of tableware produced at the Schaffner-Krause pottery.

Pie dish, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Cup, Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3". Embossed on underside: H.S. / SALEM / NC. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This cup is an archaeological surface find at Lot 51 in Salem, site of the 1767 Third House.

Detail of the base of the cup illustrated in fig. 27.

Left: Teacup, Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 2 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Right: Potter’s rib, Heinrich Schaffner pottery shop, Salem, North Carolina. Wood. H. 5 7/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Trivets, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Bone tool, stamp mold, and brass ribs, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. L. of largest rib 5 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The bone tool on the left was used to scribe bands and grooves into wheel-thrown vessels. The circular stamp produced floret impressions in wet vessels. The two brass potter’s ribs on the right were used to shape wheel-thrown pottery. All of these potter’s tools were found in direct relationship with the north foundation wall of the pottery shop during excavations.

Crock, maker unknown, 1790–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Though archaeologically excavated at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site, this crock was manufactured elsewhere; there is no evidence of the production or firing of salt-glazed stoneware at the Schaffner-Krause site. Recovered outside the doorway of the dry house, this crock probably was used for storing supplies.

Pipes and sagger pins, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Pipe mold, unknown maker, post-1834. Metal. H. 2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) Moravian stub-stem pipes and pipe sagger pins were found archaeologically at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site. They are shown with a pipe mold from the Wachovia Historical Society that came from a Salem pottery shop. This mold perfectly fits a “Philosopher” pipe found at the pottery site.

Tobacco pipe, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Michael O. Hartley.) Green glazed “Philosopher” pipe found during excavations at the pottery site in 2004. This is another example of the pipe shown in the mold illustrated in fig. 33.

Tobacco pipe, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Tobacco pipe, Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. Earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Above the eagle is a “C”—a portion of the “NC” used in Schaffner’s mark.

The reverse of the eagle pipe illustrated in fig. 36, showing Schaffner’s “H.S.” stamp on the stem. The smeared lettering directly under the crown reads “SALEM.”

Loaded pipe sagger, Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834. D. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Pipes were fired in pipe saggers such as this one, loaded with 27 stub-stem pipes set on sagger pins. In the 1882 photograph of the pottery operation illustrated in fig. 6, the workman at center right is loading one of these saggers, taken from the racks of pipes on the trestle in front of him. Stacks of them are behind him against the kiln wall.

Augusta Crouse Masten, 1963; photograph by Jim Keith, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. (Forsyth County Public Library Photograph Collection.) Mrs. Masten, daughter of Daniel Crouse, the last master potter in Salem, was featured in a 1963 Winston-Salem Journal article entitled “She Made Salem Pipes.” Pictured here in her eighties, she is seated with pottery wares and is holding a Moravian stub-stem pipe, a product that from childhood she helped her father manufacture. Her father died in 1903; she operated the pottery for a year, but closed it when she could not find skilled help.

The deep and prolific Moravian pottery tradition in North Carolina began with the 1755 arrival of Gottfried Aust (1722–1788) in Bethabara and was carried into the nineteenth century by Rudolph Christ (1750–1833). These two potters have been the ones most identified with beautiful slip-trailed decorated wares, dramatic forms, and innovative experimentation, and, with the exception of a brief period in which Christ had his pottery in Bethabara, they worked for the Moravian Diacony (as a business of the church congregation), which kept detailed records of the activities in their shops.

Following Christ’s 1821 retirement and the appointment of John Holland (1781–1843) as Salem’s third master potter, the luster of the tradition as manifested in the Diacony pottery shops began to fade. Holland, who had apprenticed under Christ and had been a journeyman in Christ’s shop, did not rise to the expectations of the Aufseher Collegium, the supervising board of the Salem congregation. His shop lost money, which, according to the Salem governing boards, was due to his lack of industry as well as manufacturing insufficient quantities and producing poorly made wares.

By 1827 the Aufseher Collegium began to look for another potter to revive the failing Moravian pottery business. There were potters in the vicinity who had been trained in the North Carolina Moravian pottery tradition as apprentices and then journeymen under either Aust or Christ, but for reasons unknown they were not sought as alternatives to Holland. Instead, the Salem Aufseher Collegium wrote to the supervising board of the Moravian Church worldwide, the Unity Aufseher Collegium in Europe, and asked it to recommend a potter qualified to come to Salem as a master potter. The Unity suggested Heinrich Schaffner (1798–1877), a potter working in the Single Brothers’ House in Neuwied, Germany. Born in Anton, Canton Basel, Switzerland, Schaffner had moved as a boy to the Moravians of Neuwied, where he had been trained as a potter and was working at the time of the Salem inquiry.

John Holland’s poor performance had prompted the Aufseher Collegium to cease operating the pottery as a congregational business in 1829, bringing an end to the linear pottery tradition conducted within Wachovia. But the Collegium was not done with its interest in pottery production in Salem, and the tradition was continued in an interesting and important way, initiated by their request for a potter from Europe.

Although Heinrich Schaffner did not report to Wachovia immediately, he arrived in 1833. The Salem Aufseher Collegium initially placed him in John Holland’s shop, but within six months Schaffner indicated that he would not stay in that arrangement. In April 1834 he asked to be allowed to set up his own shop, telling the Aufseher Collegium “that for several good reasons he was minded to sever his present connection with John Holland in the pottery, wishing to set up one of his own.”[1]

By this time the Aufseher Collegium had recognized Schaffner’s industry and skill and were pleased to grant his request, adding, “We regretted that he could not take over the pottery altogether in Holland’s place: the latter shows little zeal in carrying it on.”[2] Schaffner asked for the old Builders’ House on Lot 81, constructed in 1766, for his shop, and this was made available to him on a rental basis. He also wanted “the use of several tools which now lie unused at Holland’s.”[3] These were provided to him and included a pipe mold, a glazier’s mill, and a potter’s wheel.

Schaffner was given permission to dig clay, and the Collegium reported on June 9, 1834, that he had already carried out this task in Blum’s meadow, the traditional source of pottery clay in Salem. By June 14, within days of digging his clay, he had thrown at least one vessel. It was a creampot of the same form that had been thrown by potters in Wachovia since the arrival of Gottfried Aust eighty years earlier, but Schaffner’s creampot had several significant differences. Unlike the others, which were glazed on the interior but unglazed on the exterior, this creampot was coated inside and out with a rich brown glaze, a special treatment for this form. Moreover, the vessel was inscribed “Henry Shafner in Salem NC Stokes County June 14 1834,” then carefully set aside after it was fired (fig. 1).

We know this creampot was treated with care because of its continuing survival. It was passed down through the Schaffner family, who in 2002 made a gift of it to Old Salem, Inc. It was, of course, known to be an important example of Schaffner pottery, but it was not until we began our research on the pottery site that it was recognized as his initial statement of the beginning of his career in North Carolina as a Moravian master potter.

Archaeological Investigations

We were compelled to explore Schaffner’s continuation of the Salem Moravian pottery tradition by archaeological discoveries made in the late 1980s in Old Salem. Excavations on Lot 33 and the Herbst House complex in Salem recovered a large amount of industrially produced whiteware, tableware, and tea and coffee service. This was not unexpected, because the domestic occupation of the Herbst lot had continued through the nineteenth century after the construction of the Herbst House in 1821. In this period the Moravians of Salem were becoming more amenable to products from outside their community, which were more readily available. Surprising, however, was that the kitchenware was locally produced lead-glazed utilitarian earthenware. The archaeologically recovered artifacts came from a cellar dug in 1833 and sealed in 1860, giving them a context dating to the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

The locally produced artifacts indicated an ongoing continuum of the Salem Moravian pottery tradition, in both form and material, well into the nineteenth century. At the time of the Lot 33–Herbst House excavation, much previous research had been directed toward the products of Gottfried Aust and Rudolph Christ. However, no significant archaeological exploration and analysis had been undertaken on nineteenth-century pottery production in Salem after Christ. Indeed, most scholars considered that the Salem Moravian pottery tradition ended with John Holland’s poor performance. The surprising presence of locally produced lead-glazed wares in a post-1833 context on the Herbst lot prompted archaeological research into the probable source of these wares.

The source was, in fact, Heinrich Schaffner’s pottery shop on Lot 81 in Salem, which he began in 1834. Moreover, following Schaffner’s death, in 1877, this operation passed into the hands of Daniel Krause (1836–1903), who had come into the Schaffner shop and household in 1846 as a nine-year-old apprentice and continued as a journeyman potter in the shop. On Schaffner’s death, Krause became the last master potter of Salem and worked until he died, in 1903 (figs. 2, 3).[4]

This research was expected to show a heavy emphasis on the production of utilitarian forms of lead-glazed earthenware. There had always been an emphasis on utilitarian ware by all the Moravian potters because the demand for it was high. However, the Aust pottery had also produced much decorative slip-trailed ware, and Christ was known for his English creamware-style fine pottery and bottles made in animal forms, as well as other innovations. What we did not expect to find at the Schaffner-Krause pottery was the great range and variety of wares that were produced in this nineteenth-century shop.

Exploratory excavations began on the site in 2000, with an initial search for the kiln. The east wall of the kiln was located, and for the next two seasons excavations focused on fully exposing that feature (figs. 4, 5). The kiln was a rectangular structure with a choked-down firebox on its north end that extended into the dry house. From the archaeological evidence it is clear that the kiln was fired from within the dry house, although the complete function of that particular building is not yet fully understood (fig. 6).

Utilitarian Wares Found on the Site

After our initial exposure of the Schaffner-Krause kiln, the archaeological excavations continued on the kiln and were expanded into the shop, dry house, and warehouse ruins. These areas of the pottery complex are identified on the 1885 Sanborn Insurance Map of the lot (fig. 7), and a number of documentary photographs also provide valuable information. Although excavation continued through 2008, much remains to be uncovered. As analysis of recovered artifacts pressed forward in the archaeology laboratory, other wares were seen, many of them directly in the tradition of North Carolina Moravian utilitarian lead-glazed earthenware.

Because of Schaffner’s German training, his production of forms in that tradition points to deeper origins of these forms than Aust in Bethabara and the subsequent pottery operations in Salem. Schaffner’s creampots, aside from his first (see fig. 1), are formally identical to those produced by Aust in the colonial period—glazed on the interior and with the glaze wiped from the rim (fig. 8). Schaffner’s stint in Holland’s shop, a matter of a few months, would have exposed him to the Wachovia school of pottery, but he also brought with him from Germany an underlying knowledge. His cookpots are thrown in a basic form with the traditional rim, body, and handles, but with the flat bottom seen in the nineteenth century to accommodate cooking on a wood-fired range rather than on the hearth in coals. However, the flat-bottomed cookpot was also modified by the Schafffner-Krause pottery to a form suitable for hearth cooking by adding three legs, as was characteristic of earlier cookpots. Three cookpot modifications of the basic flat-bottom form are found in Salem in the nineteenth century. From the Schaffner-Krause site, we have recovered a three-legged, flat-bottom cookpot and a double-handled, flat-bottom cookpot minus the three legs. A nearly identical contemporaneous flat-bottomed form with a single handle (without legs) was found in the Herbst House excavation (figs. 9-11).

These variations within the form convey customer preferences, presumably because of differences in cooking behaviors. The presence of three-legged cookpots indicates that there were customers who continued to hearth cook in beds of coal well after 1834; the form without legs points to the use of cookstoves. This example also speaks to the flexibility of the potter to accommodate his customers’ preferences. Pointedly, these variations indicate the obvious: that Schaffner and, later, Krause were responding to customer demand. The continued use of the eighteenth-century vessel forms made by both Schaffner and Krause is indicative of forceful cultural dynamics for maintaining traditional systems of food preparation in Salem and Wachovia.

Other traditional forms produced by Schaffner and Krause were apothecary jars, pans, and bowls, as well as crocks and flowerpots (figs. 12, 13). Their presence was not unexpected, as all are part of the traditional array of Moravian utilitarian earthenware.

Schaffner’s abilities for producing molded ceramics came with him from Germany. Neuwied, where he had trained, was a production center for Moravian tile stoves. Schaffner brought plans for such a wood-burning heater with him when he came, with designs for a particular acanthus-leaf style of tile (fig. 14). Schaffner-produced tile stoves are in the Old Salem collection, and fragments of moldings used in this stove style were found archaeologically at his pottery, as would be expected. There were, however, some distinct surprises at the Schaffner-Krause pottery.

Unexpected Finds: Creamware, Animal Bottles, Slip Decoration

The production of “fine pottery” English creamware forms associated with Rudolph Christ has been known for many years. These wares, also produced by John Bartlam in South Carolina, have been named “Carolina Creamware” by Stanley South and have been an important research subject for some time.

We now realize that Heinrich Schaffner was also producing molded creamware forms in his shop, and probably with some of the same molds used by Christ. It is known that a large number of Christ’s molds were still in existence in 1829. At that time, the Aufseher Collegium discontinued the Salem pottery as a congregation business and recorded: “Sundry Moulds which Br. John F. Holland received from Rud. Christ 1821 in Trust and returned to Wm Benzien in Sept. 1829.”[5] William Benzien was the administrator of Salem in 1829, and the inventory of the material that Holland returned to him lists more than two hundred molds for such forms as turtles, fish, owls, squirrels, foxes, and chickens, among others. There were molds for dolls of various sizes, for birds, sheep, dogs, bears, turkeys, ducks, and an Indian. There were molds for teapot spouts, baskets, pickle leaves, and tart plates. There were also “sundry plate moulds.”[6]

Archaeological evidence indicates that after Schaffner’s arrival in Wachovia and the opening of his shop in 1834 he was given use of a number of these molds for various products. A visitor to the Schaffner-Krause pottery shop in 1888 confirmed that the shop was still in operation “and has some of the quaint old moulds dating back to 1774.”[7] This is supported by the feather-edge and Royal pattern plates in bisque found at the Schaffner-Krause pottery (fig. 15). Schaffner’s production of this ware is confirmed by his stamp on the bottom of a feather-edged plate (fig. 16). Other examples of production of this type of ware at the pottery are a sprig-molded fragment of what appears to be the lid of a hollow ware vessel (fig. 17) and extruded and molded handles. The existence of such sherds suggests that Staffordshire-style wares may have been produced well after the second quarter of the nineteenth century (fig. 18).

Sherds from animal bottle forms—most commonly attributed to Rudolph Christ—have also been found in bisque at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site. One group of sherds forms the base of a bird bottle, perhaps an owl or a chicken (fig. 19). A molded animal paw was recovered that could be from a bear or a squirrel bottle (fig. 20). A molded animal head, perhaps that of a sheep, speaks to a form not presently understood (fig. 21). Sherds from a molded handle were not clearly understood until they were found to match the form of a lion’s-head mold in the collection of the Wachovia Historical Society (fig. 22), strongly suggesting that the provenance for the historical society’s mold was the Schaffner-Krause pottery shop.

Also unexpected at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site was the presence of slip-trailed lead-glazed earthenware. Production of this decorative ware by the Moravian potters faded in the nineteenth century, prior to 1830, but there is evidence at the Schaffner-Krause pottery that its manufacture continued after 1834, at least to some degree. Old Salem Archaeology Laboratory Manager Jennifer Garrison has been carefully examining the ceramics excavated from the pottery complex, including the small number of slip-trailed decorated sherds (fig. 23). Among these sherds are examples that are in the bisque stage, indicating that they were in production at the shop.

Schaffner (and probably Krause) was certainly manufacturing tableware. A striking example of a pint cup, very like eighteenth-century porringers found at the Aust shop, was recovered at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site (fig. 24). This vessel is on a red base and coated in a white slip but has not been glazed and put through the glost firing.

Several turned plates, warped by overfiring, have also been recovered from the site (fig. 25). We have interpreted another form, a deep, footless plate, as a pie dish (fig. 26).

Various examples of Heinrich Schaffner’s wares have been found in other contexts as well. A heavy teacup on a buff base, with a reddish orange glaze and “H.S.” stamped on its base (a duplicate of the mark seen in fig. 16), was a 1950s surface find from Lot 51 in Salem, the site of the 1767 Third House (figs. 27, 28).

Other, more delicate examples bearing Schaffner’s stamp are teabowls and turned foot saucers and plates currently in the Old Salem collection. These are on a buff paste that fired to a dark yellow under a clear glaze with delicate floral decoration. The wooden ribs that were used to shape this cup are also in the Old Salem collection (fig. 29). There apparently were many of this type of Schaffner’s pottery in existence in 1972, when John Bivins wrote The Moravian Potters in North Carolina, because he reported that they “were evidently a popular product of the Schaffner shop, judging from the number of surviving specimens, and they are often signed on the bottom of the saucers.”[8] Bivins commented that in producing these cups Schaffner had “clung to an earlier handle-less form of teabowl.”[9] We have seen strong evidence that Schaffner’s pottery retained traditional forms and material, either as a result of his own values and training or in response to the deeply rooted traditional ways of the community.

I have argued in the past that in Salem in the last three quarters of the nineteenth century there was a move away from locally produced tableware toward industrially manufactured whiteware, yet also a retention of lead-glazed utilitarian earthenware in the kitchen. This is certainly what we observed in the archaeological excavations of the Herbst House on Lot 33.[10] The products we see from the Schaffner-Krause pottery, however, are a reminder that Moravians in Salem were not part of a monocultural society, for there were generational, social, and gender differences within the community. It is clear, however, that conservatism seen in the continued production of three-legged cookpots on a flat-bottom basic form is indicative of the support for tradition and traditional values by some members of the community.

Kiln Furniture and Potters’ Tools

A large array of kiln furniture and pottery tools has been found archaeologically at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site. Thousands of pieces of three-armed trivets (and many whole ones, in various sizes) have been located (fig. 30), as well as similar numbers of grooved setting tiles. These objects were used to support and separate vessels in the kiln as they were being fired. Innumerable lumps, rolls, and balls of fired clay—also a form of kiln furniture, quickly made up of raw clay by the potters during the loading of the kiln to support, hold, and separate ware as it was being fired—are present in all areas of the shop and kiln. Because Stanley South observed similar but elongated rolls of clay for stacking saggers from the Christ-Krause waster dump at Bethabara, rolls he called “pugging coils,”[11] we have termed the objects found at the Schaffner-Krause pottery “pugging wads.” These wads retain impressions of the parts of vessels, rims and so on, that the clay was pressed against during loading, and frequently they also show the fingerprints of the potters who formed them. The plate sagger—a cylindrical vessel perforated on the circumference for three sagger pins on which to stack plates for firing—is another type of kiln furniture recovered at the pottery site.

Tools used by the Schaffner-Krause potters to shape the wares were excavated at the shop. Brass ribs (fig. 31) were found nested together against the inside of the stone foundation wall at the north end of the shop. Such tools would have been kept handy to the potter’s bench, and both ribs have holes to hang them on a nail. The two ribs were excavated from the center of the north side of the shop, where documentary photographs show a window (note the ground-floor window on the gable/north end of the pottery shop, illustrated in fig. 6). A north window was prime lighting for workspace, and we believe these ribs indicate a potter’s bench was situated at that window. This interpretation is further supported by the presence of a bone tool, illustrated in figure 31, that was recovered archaeologically against the same foundation wall. Made from a bone toothbrush handle, this tool had grooves cut into either end for inscribing bands on the outside circumference of vessels (such as cookpots) at the potter’s wheel. Another informative potter’s tool found in the archaeological excavation was a stamp mold (see fig. 31), which, itself made from a fine-grained clay, produced floral indentations when pressed into wet clay during manufacture.

A deposit of finely textured green clay was also found inside the north wall of the shop, just east of the window location, which would have made it closely available for use at a bench under the window. We prepared samples of this clay by pressing it into reproduction molds, which were then fired by Old Salem craftsmen in a wood-fired experimental kiln based on the Schaffner kiln design. The samples fired to an orange-colored, fine-textured bisque. Gray clay recovered from the well in front of the shop fired to an off-white color.

Excavation into the dry house ruin produced an array of pottery shop vessels. We think some were used to store supplies—one of them contained a substantial amount of cobalt-colored powder, which appears to have been paint. Another large crock in this group, a salt-glazed stoneware vessel, was not manufactured at the Schaffner or Krause operation (fig. 32). Archaeological evidence clearly indicates that only lead-glazed earthenware was produced there, generating speculation about the origins of the stoneware crock.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, members of the Wachovia Historical Society (established 1895) retrieved various other tools from Salem pottery buildings, which are on loan to Old Salem: wooden potting ribs, handle extruders, saggers, a potter’s wheel, a glaze mill, pipe presses, and molds for pipes, plates, bottles, stove tiles, and other pottery items. A number of these objects—for example, wooden potting ribs—have been identified as coming from the Schaffner shop.

Moravian Stub-Stemmed Tobacco Pipes

A particular class of artifacts emerged early and had a ubiquitous presence across the excavation area: the Moravian stub-stemmed tobacco pipe. This style of pipe had been manufactured in Wachovia since Aust’s earliest days in the Bethabara pottery shop. Clay pipes identical to Aust’s forms were found at the Schaffner-Krause pottery. The stub-stemmed pipes were manufactured in molds with the molding pressure applied by a pipe press (fig. 33). Not only were earlier Aust pipe forms excavated at the Schaffner-Krause pottery, but later style designs more typical of the nineteenth century were recovered as well (fig. 34).

By late 2008 a working total of 1,700 fragments of stub-stemmed tobacco pipes had been recovered at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site. From these, lab manager Jennifer Garrison has identified thirteen pipe types that were made at the pottery. Some pipe types have been found to have more than one mold; a total of twenty-one mold forms have been identified within the thirteen pipe types.

Schaffner used molds that produced classical or humorous anthropomorphic pipes, as well as such patriotic motifs as a nineteenth-century federal eagle (figs. 35-37). Fluted and plain bowls were also present. Schaffner’s production of many of these pipes is clearly documented by his “H.S.” mark on some of the pipes; some are marked “Salem NC.”

The firing of pipes at the Schaffner-Krause pottery was done in pipe saggers with the pipes mounted on sagger pins (fig. 38). Sagger pins for pipes typically had a bulbous head, which was inserted into the bowl of the pipe and the other end of the pin stuck into a hole at the bottom of the sagger. Pipe saggers and pipe sagger pins, as well as saggers for firing other products, were found in large quantities at the Schaffner-Krause pottery.

Near the center of the photograph taken in 1882 when Daniel Krause was master of the pottery (see fig. 6), the man at the worktable is loading pipe heads into saggers in preparation for firing. He has one sagger in his hand and many more saggers are stacked against the kiln wall behind him. On the table in front of him, at least 1,000 dried pipes in rows are ready for firing. Each sagger held between 25 and 30 pipes, so in the neighborhood of 30 to 40 saggers would be required to fire 1,000 pipes. The seated man at the far left appears to be working with a pipe mold, and master potter Daniel Krause stands to the left in a derby hat. The “famous Salem pipe” was an important product of the shop during Krause’s tenure, but in this 1882 photograph other wares await loading as well, and it cannot be known what has already been placed in the kiln.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century the Krause family name was anglicized to Crouse. In a newspaper article that appeared in the Winston-Salem Journal in 1963, Daniel Krause’s daughter, Augusta Crouse Masten (1880–1971), was interviewed about pipe making at the shop. She recalled working there when she was twelve or thirteen years old and “making up to 800 pipes a day”: “Oh we shipped them by the barrel-full,” she said. “We got the barrels from breweries and barrooms and packed the pipes tight with shavings. Most of them we shipped to Norfolk and Portsmouth, places along the coast. The sailors seemed to like them. Old man Reynolds—you know, the founder—once asked my father if he could make pipes to go in with the smoking tobacco. We couldn’t make that many. Every bit of it was hand work.” She also reported in the article that her father regarded his clay, which he dug in nearby Salem, as superior for the manufacture of tobacco pipes because it was porous and absorbed nicotine better than “cheap, ordinary pipes.”[12]

Mrs. Masten worked for her father for more than a decade. She also ran the pottery for one year after her father’s death in 1903, ending production because of a lack of trained help. After she died in 1971, her memoir, the traditional record of a deceased Moravian’s life, stated: “Her father, Daniel Thomas Crouse, was the last of a long line of Salem potters. From him she learned the art of pottery-making. After his death she even carried on his business for a time. Many objects such as preserve pots and clay pipes were made by her.”[13]

In a photograph that was taken during the newspaper interview (fig. 39), Mrs. Masten sits beside a small group of pottery pieces. No doubt these were products of the Schaffner-Krause pottery, perhaps made by her. The large dish on the table by her left arm is very like one from the Schaffner-Krause pottery site and identified as a pie dish (see fig. 26). Mrs. Masten provided support for this identification, speaking of “pie dishes” as one of her father’s products.

Mrs. Masten witnessed the end of the long tradition of Moravian pottery. Research on the Schaffner-Krause pottery site, and the various paths it leads us down, continues to provide new revelations about Moravian potters, lead-glazed earthenware, and holding to a tradition. At this writing, we wonder what Mrs. Masten’s preserve pots were like.

Adelaide L. Fries and Douglas LeTell Rights, eds., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, 1823–1837, vol. 8 (Raleigh, N.C.: State Department of Archives and History, 1954), p. 4132.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Nick Elliott, “She Made Salem Pipes,” Winston-Salem Journal, May 19, 1963.

Folder R701:3, Moravian Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Ibid.

D. P. Robbins, Descriptive Sketch of Winston-Salem, Its Advantages and Surroundings, Kernersville, Etc. Compiled under the Auspices of the Chamber of Commerce, from a Matter of Fact Standpoint (Winston, N.C.: Sentinel Job Print, 1888), p. 9.

John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972), p. 133.

Ibid.

Michael O. Hartley, “Heinrich Schaffner and the Moravian Ceramic Tradition in Nineteenth-Century Pottery in Salem,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 31, no. 1 (2005): 1–44.

Stanley A. South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999), p. 314.

Elliot, “She Made Salem Pipes.”

Memoir of Augusta Crouse Masten, 1971, Moravian Archives, Southern Province.