Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Bottle, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Private collection.)

Dish and bowl fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware and bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) All of these Solomon Loy fragments are from site 31AM191.

Flask, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1770–1790. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the decoration on one side of the flask illustrated in fig. 4.

Detail of Hyacinthe Rigaud, Cardinal de Bouillon, Perpignan, France, 1708. Oil on canvas, 97" x 95". (Courtesy, Musée Hyacinthe Rigaud.)

Antoine Raspal, Portrait de Jeune Fille en Costume d’Arles, France, 1779. Oil on canvas. 24 1/2" x 24". (Courtesy, Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence, don du docteur Arnaud.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1770–1790. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Details showing the back profiles of the dish illustrated in fig. 8 (left) and a dish attributed to the Moravian pottery in Salem, North Carolina (right).

Detail of the cavetto decoration on the dish illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of the decoration on the shoulder of the flask illustrated in fig. 4.

Powder flask, probably Germany, 1600–1650. Wood, brass, and wire inlay. (Private collection.)

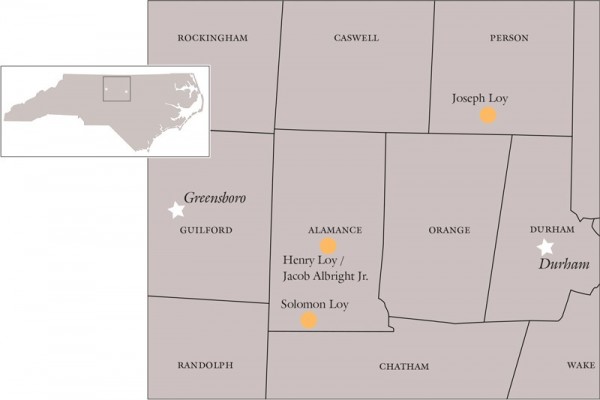

Map showing pottery site locations for Henry Loy, Jacob Albright Jr., Solomon Loy, and Joseph Loy.

Dish fragments recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) The fragment at the upper right has marbleized decoration. Slip-decorated earthenware might have been produced at this site before it was occupied by Albright and his son-in-law Henry Loy.

Details showing a cavetto fragment (lead-glazed earthenware) recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site and the marly decoration on the dish illustrated in fig. 30.

Dish fragments recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1820. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Mug fragments recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Side, front, and rear views of a tankard, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1785–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9". (From the Collections of The Henry Ford 59.144.3)

Handle fragment recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1775–1795. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1775–1795. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 5/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1775–1795. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 14 7/8". (From the Collections of The Henry Ford 59.143.1)

Chest, attributed to Bern Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1785–1795. Tulip poplar and pine. H. 28 5/8", W. 52 1/2". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the painted decoration on one side of the chest illustrated in fig. 23.

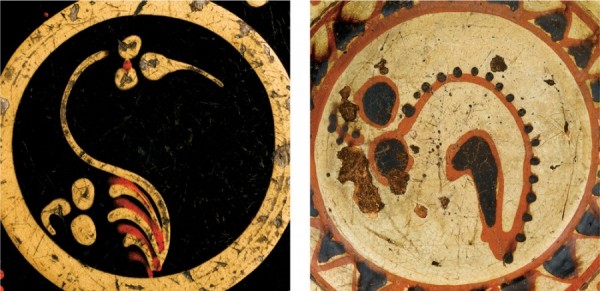

Details showing the decoration in the cavetti of the dishes illustrated in fig. 20 (left) and fig. 21 (right).

Details showing the back profiles of the dishes illustrated in fig. 20 (top) and fig. 21 (bottom).

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1785–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (From the Collections of The Henry Ford 59.145.2)

Detail showing the decoration in the cavetto of the dish illustrated in fig. 27 (left) and a cavetto fragment (right) recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Details showing the back profiles of the dishes illustrated in (from left to right) figs. 1, 29, and 30.

Detail of the fluted separator on the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 29.

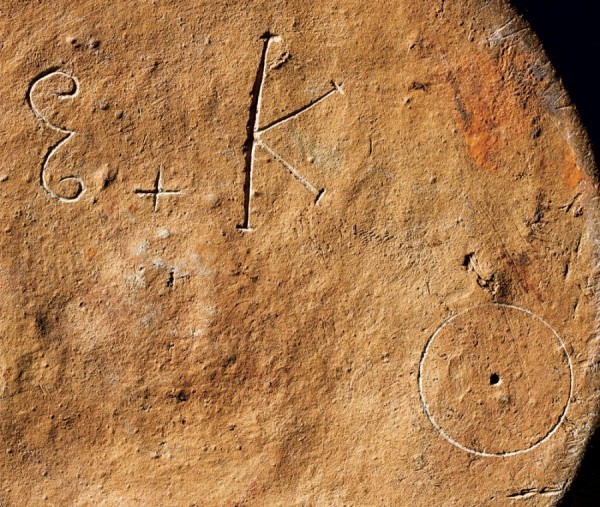

Detail of the post-production marks on the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 1.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Private collection.)

Detail of the post-production marks on the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 35.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Private collection.) This dish has a twentieth-century recovery history in Alamance County.

Detail of the back profile of the dish illustrated in fig. 37. The profile of this example is virtually identical to that of the dish illustrated in fig. 35.

Dish fragment recovered from lot 49 in Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1820. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Punch bowl, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/4". (Private collection.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This is the earliest dish with “nested triangles,” a motif commonly employed by Solomon Loy. Antecedents for this motif can be seen on the front panels of paint-decorated chests attributed to Bern Township in Berks County, Pennsylvania (see fig. 23).

Details showing the back profiles of the dishes illustrated in fig. 41 (left) and fig. 42 (right).

Details showing the decoration in the cavetti of the dishes illustrated in fig. 1 (left) and fig. 41 (right).

Details showing the decoration in the cavetti of the dishes illustrated in fig. 20 (left) and fig. 42 (right).

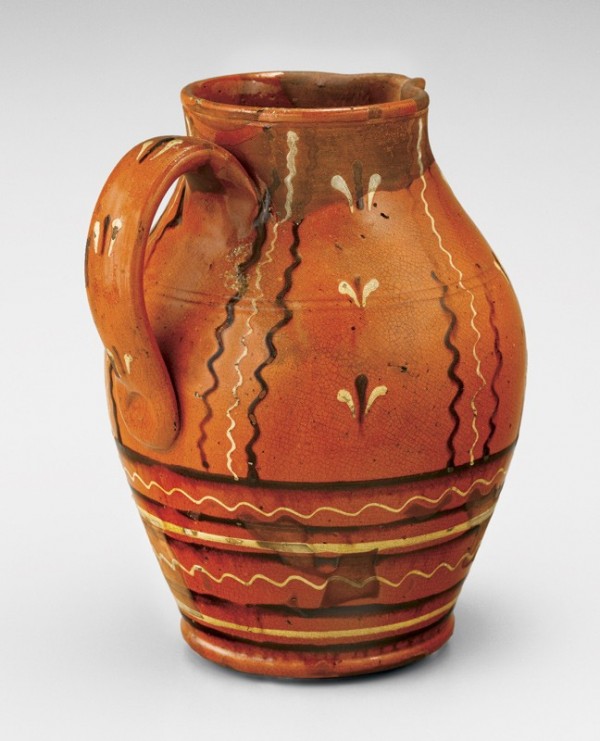

Pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1785–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Fragmentary pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

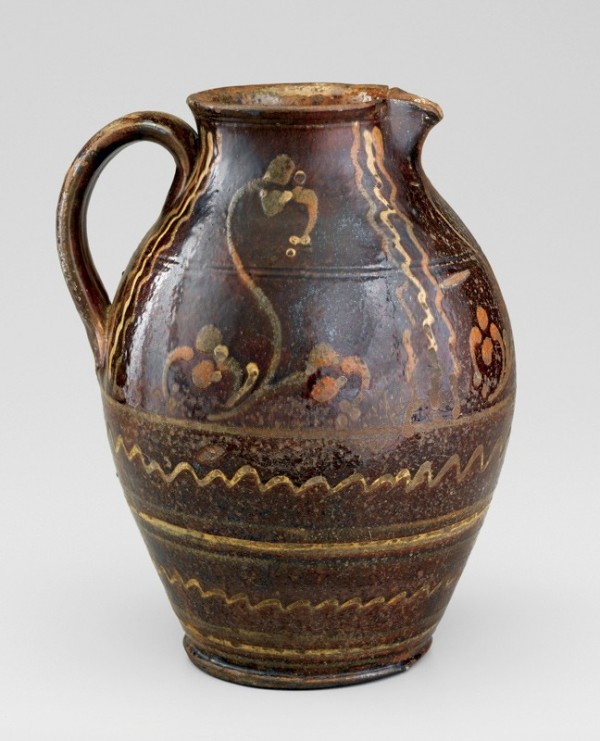

Pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Private collection.)

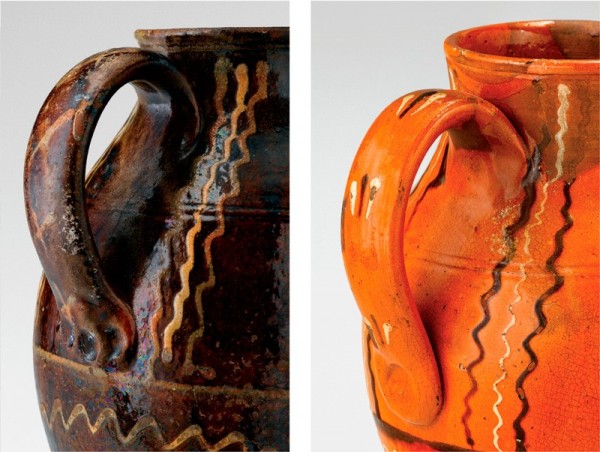

Details showing the rims and handles of the pitchers illustrated in fig. 46 (left) and fig. 48 (right).

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 7/8". (Private collection.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Private collection.)

Pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.)

Pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Private collection.)

Detail of the rim of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 53.

Detail of the handle terminal and foot of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 53.

Rear and side views of a pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/2". (From the Collections of The Henry Ford 59.15.3)

Pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the handle and body of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 57.

Fragmentary pitcher, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The stylized plant motif on this object is visible in fig. 60 (right).

Detail showing the decoration on the pitchers illustrated in fig. 46 (left) and fig. 59 (right).

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Private collection.)

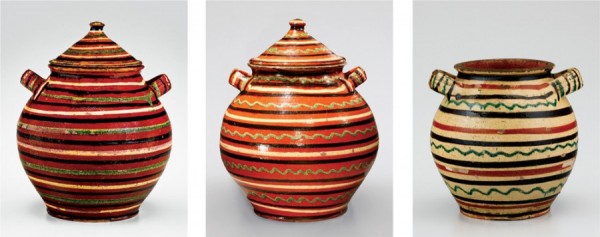

Sugar pots, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 12 3/4" (left), 13" (center), 7" (right). (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art [left], From the Collections of The Henry Ford 59.143.3[center], private collection [right].) The pot with the white ground descended in the Crouse family of Alamance County.

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8". (Private collection.) This jar descended in the Löffler (Spoon) family of Alamance County and southeastern Guilford County. The 1787 tax list for the St. Asaph’s district lists “Widow Sarah Spoon.” John, Adam, and Peter Spoon were listed in the 1792 assessment.

Sugar pots, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8" (left), 8" (right). (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Sugar pots, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10" (left), 10" (right). (Private collection.)

Condiment pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The lower section of this pot has a partition in the center.

Bowl, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3". (Private collection.)

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1770–1790. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the rim and handle of the sugar pot illustrated in fig. 68.

Exterior and interior views of a sugar pot lid, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1770–1790. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 7". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1785–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/2". (Private collection.)

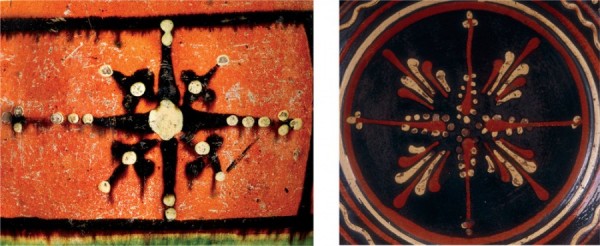

Details showing the cross and fleur-de-lis decoration on the sugar pot illustrated in fig. 72 (left) and the dish illustrated in fig. 31 (right).

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the rim, handle, and body of the sugar pot illustrated in fig. 74.

Detail of the rim, handle, and body of the sugar pot illustrated in fig. 75.

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The color and surface texture of the lid are somewhat different from those of the body. Although it is possible that this discrepancy denotes an early “marriage,” the fit of the lid suggests that it is original. Placement in the kiln and subsequent use could account for the differences visible here.

Detail of the rim, handle, and body of the sugar pot illustrated in fig. 78.

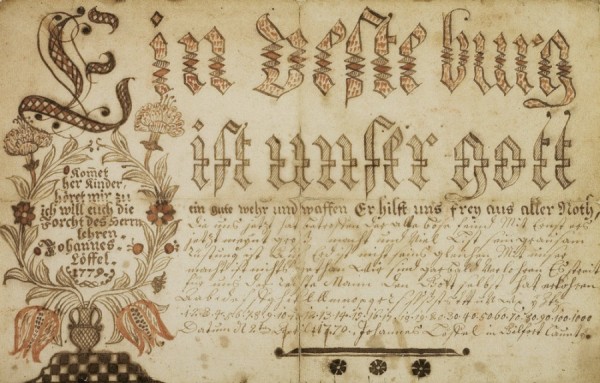

Confirmation certificate for Johannes Löffler Jr., Guilford County, North Carolina, 1779. Ink and watercolor on paper, 8 1/2" x 12 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.) This dish is probably an early example by Solomon Loy or one of his immediate predecessors.

Details showing the marly decoration on the dishes illustrated in fig. 1 (left) and fig. 81 (right).

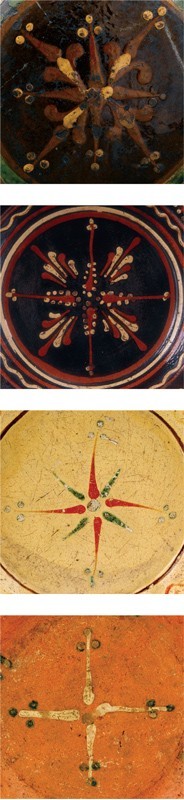

Details showing the decoration on (from top to bottom) the flask and dishes illustrated in figs. 4, 31, 81, and 51.

For more than forty years the Moravian potteries at Bethabara and Salem have been considered the primary production sites for Germanic slip-decorated earthenware in the piedmont region of North Carolina, based on several factors. The Moravian records contain detailed information on the locations of potteries, the personal and professional lives of craftsmen, the types of wares made, and the technologies employed, as well as the business dealings both within and outside their communities. These documents provided a framework for archaeology conducted by Stanley South during the 1960s and 1970s and for John Bivins Jr.’s groundbreaking monograph, The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (1972).[1] Since the publication of that book, nearly every major example of slip-decorated earthenware from North Carolina has been attributed to Moravian potters. Recent research indicates, however, that non-Moravians working in and around the St. Asaph’s district of Orange County (now southern Alamance County) made much of the slipware that survives (figs. 1, 2). As this essay will reveal, the ceramic tradition of these potters was shaped in the cultural melting pot of southwestern Germany, brought to America in the Palatine migration of the mid-eighteenth century, and preserved through kinship, apprenticeship, and community networks.

Origin and Exodus

For much of the seventeenth century, the population of southwestern Germany was in flux as people moved to escape war and disease and Protestant princes brought in settlers from other areas of the Holy Roman Empire to repopulate the region. Tax concessions and religious toleration attracted Mennonites from Switzerland, Jews from Portugal, Walloons from Belgium, Lutherans and other reformed sects from poorer territories of Germany, and Huguenots, primarily from the northeastern provinces of France. Historian Philip Otterness has shown how migration within the Palatinate and its repopulation by people from various parts of central and Western Europe made the region one of the most culturally diverse areas of early modern Germany. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, most villages and towns in southwestern Germany were inhabited by people who “spoke different dialects, practiced different religions, and observed different customs.” In fact, argues Otterness, “[m]any of the people whom the British called Palatines would have been more comfortable referring to themselves as French or Swiss or natives of some other region of the Holy Roman Empire.”[2]

Although emigrants from southwestern Germany may have lacked a strong regional identity, most were from small towns and villages where communal bonds developed through religion, intermarriage, and the activities of everyday life. Craftsmen were an essential part of that process on both sides of the Atlantic. In the Palatine migration of 1709, which included ancestors of the Efland family of Alamance County, approximately one-third of the migrants were artisans.[3] That percentage may have increased over the next four decades owing to demographic and economic shifts in southwestern Germany. On the ship Elizabeth, which arrived in Philadelphia on August 27, 1733, were, among others, Palatines who settled in Pennsylvania and later moved to Guilford County and Alamance County; nearly half of the adult males were craftsmen.[4] As historian David Warren Sabean has noted, artisans were among the wealthiest inhabitants of German villages at the beginning of the eighteenth century, but by the end that was seldom the case.[5]

Many of the Palatines arriving in America were married couples who had been marginalized by war, population growth, high taxes, agricultural failures, serfdom, and partible inheritance. These factors influenced migration more than the enticing descriptions of British North America circulating by word of mouth and in printed propaganda during the first half of the eighteenth century. As historian Mark Häberlein has observed, “émigré couples typically arrived with dependent children who could provide labor or be bound out to pay passage costs or supplement income.” His study of emigration from the principality of Baden-Durlach also suggests that many of the families as well as single individuals who came to Pennsylvania were related. Immigrants settled in areas where land was available and members of their family had established themselves earlier.[6] As land became scarce in eastern Pennsylvania, this paradigm shifted to the south and west.

Community Development

In her study of German migration and adaptation in the Catawba Valley region of North Carolina, historian Susanne Mosteller Rolland noted that immigrants who settled there often did so in “a series of clusters.” Although geographically dispersed, these communities forged connections through “kinship, acquaintanceship, and religious networks.”[7] That was certainly true in the central piedmont as well. In an August 1772 diary entry, Moravian missionary George Stolle alluded to ties between the German-speaking communities of southeastern Guilford County (known during the period as “Stinking Quarter”) and southern Alamance County:

The settlers . . . are nearly all German. They have four churches, one in Alamance and three in Stinking Quarter; the newest is large, and has a pulpit and galleries. [Samuel Sutor] preaches in all of them, and Nott [Stinking Quarter’s school teacher] reads when there is no preaching. Sutor was a Swiss, unlettered and unordained, [and] from my heart I pitied the poor people, who spent their money where there is nothing to buy. They had engaged Sutor for four years.[8]

The experiences of the Clapp (Klapp), Albright (Albrecht), Foust (Faust), Loy (Laye), and Sharp (Schärp) families reflect many of the broader demographic patterns cited by the aforementioned historians. The Clapps who settled in southeastern Guilford County, which adjoins Alamance, trace their ancestry to brothers George Valentine Clapp and John Ludwig Clapp. George was born at Weisenheim, Germany, in 1702 and married Anna Barbara Steiss in the Lutheran Church there on October 24, 1723.[9] The couple arrived at Philadelphia on the ship James Goodwill on September 27, 1727, settled near Olney in Berks County, Pennsylvania, and had at least four children before moving to Guilford County. John Ludwig’s birth date is not known, but he married Anna Barbara Strader before emigrating. They also arrived on the James Goodwill, settled near Olney, and had several children before moving to North Carolina. Five of their nine children married members of the Foust family, two married members of the Albright family, and at least five followed their parents south.[10] Most of the Clapps attended the German Reformed Church that George Valentine Clapp and his brother John Ludwig helped found on Beaver Creek.[11]

Most of the Albrights who came to North Carolina settled in southern Alamance County and initially were affiliated with a German Reformed Church (later referred to as Steiner’s Church or sometimes Stoner’s Church) that Jacob Albright Sr. helped found on Alamance Creek.[12] He was five when his parents, Johannes and Anna, and siblings—Ludwig, Anna Barbara, Magdalena, and Christian—arrived on the ship Johnson on September 18, 1732.[13] Johannes may have moved to the Palatine region from Switzerland. Several family genealogies maintain that Jacob’s father was Johannes Ludwig Albrecht von Oberenstringer, who was born at Wyniger, Switzerland, in 1694 and married Anna Barbara Gossauer von Reisbach.[14] As was the case with the Clapps, the Albright family that immigrated in 1732 settled in Berks County. Johannes and his wife remained in Pennsylvania, but Jacob, Ludwig, and Anna Barbara moved to Alamance County.[15] Anna Barbara and her sister Magdalena married into the Foust family.[16]

Johan Peter Foust, a farmer from Langenselbold, Hessen, Germany, was one of the first members of his family to emigrate from the Palatinate.[17] He, his second wife, Anna Elizabeth (Grauel), and eleven of their twelve children arrived on the ship Elizabeth on August 27, 1733, and subsequently settled in Berks County. The passenger list noted that Johan and his eldest son, Peter, who was twenty at the time, were farmers.[18] At least two of Johan and Anna’s children moved to Alamance County: Johannes, who married Anna Barbara Albright, and Anna Elizabeth, who married Philip Snotherly.[19]

Generations of family tradition have maintained that the Loys were Huguenots who left France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and settled in Germany. Five men with the surname Lay or Laye arrived in Philadelphia on ships with Palatine passengers during the 1730s and 1740s: Christopher on September 25, 1732; Matthias on August 17, 1733; Ludwig on November 25, 1740; Johannes on November 25, 1740; and Martin on September 26, 1741.[20] Although the relationships among these men are not known, it is possible that they were kin.

Martin is the only émigré-generation Loy who moved to North Carolina. He might have been born at “Hertzenhausen” (probably Herzenhausen), Hessen, where his father Johannes worked as a tailor. Johannes and his wife, Anna Martha, subsequently relocated to Mussbach, which is about 250 miles to the south. On December 4, 1729, Martin married Anna Margaretha Fechter in the Reformed Church at Mussbach.[21] Their children—Catharina, Johan Jacob, and Emmanuel—were baptized there in 1730, 1734, and 1737, respectively.[22] Martin and Anna arrived in Philadelphia on the ship St. Mark on September 26, 1741, but there is no record that they brought their children with them.[23] Anna must have died shortly thereafter, since Martin married Anna Catrina Foust about two years later. Anna Catrina was almost certainly related to Johan Peter Foust. The passenger list of the ship Elizabeth noted that she was twenty-one, which suggests that she may have been the daughter of Johan and his first wife, Magdalena (Adams).[24] Martin and Anna Catrina had four children: George, John, Henry, and Mary.[25] The Loys apparently moved to Augusta County, Virginia, before February 17, 1753, when the estate of Colonel James Patton held a joint bond of Martin Loy, John Sharp, and Ernest Sharp. The following year, Loy purchased 230 acres of land on Tom’s Creek, adjacent to property owned by George Sharp.[26] Although the relationship is not fully understood, it is known that the Loys and Sharps were connected.[27] Isaac Sharp III, brother of John and George, witnessed Martin Loy’s will, and Isaac’s daughter Philopena married Loy’s grandson John.[28] Members of both families settled in Alamance County and attended the same German Reformed Church.[29] Martin bought 251 acres of land on Great Alamance Creek from Henry McCulloh in December 1765, but the precise date he and his family arrived in North Carolina is not known.[30] He acquired an additional 112 acres on the south side of Great Alamance Creek on February 1, 1769.[31]

Bloodlines and Claylines

Documentation for Martin Loy’s trade remains elusive, but at least one of his grandsons and six of his great-grandsons were potters (see Loy family tree, p. 108, fig. 2, in this volume).[32] In Europe and America potters working outside large metropolitan areas typically relied on kinship networks to safeguard craft knowledge, provide an affordable and trustworthy workforce, pass trade secrets from generation to generation, absorb competition and build patronage networks through intermarriage, secure raw materials and financing, and establish links to their community. As folklorist John Burrison observed, rural potters “guarded their family lines as carefully as they did their craft traditions.”[33] As a result, family potting traditions were often as stylistically and technically monolithic as those associated with urban guilds or other governing associations. This was especially true when potters were part of a culturally homogeneous community, since makers and consumers were inextricably bound in the production of objects.[34]

Documentary and archaeological evidence suggests that much of the slipware made in the vicinity of southern Alamance County was the product of a multigenerational family tradition. The legacy of these potters has only recently come to light. Most of the objects associated with them were formerly attributed to Moravian potters, particularly Rudolph Christ. In Moravian Potters in North Carolina, Bivins refers to the imbricated triangles, stylized grass motifs, lunetting, and rows of dots on the dish illustrated in figure 1 as “signatures” of Christ’s work.[35] Bivins’s assumptions were not unreasonable at that time, since a small group of dish fragments with comparable designs had been excavated at Bethabara and Salem. Subsequent archaeological research has shown, however, that Alamance County potter Solomon Loy used all of those details (fig. 3).[36] Moreover, there is no evidence that Moravian potters applied polychrome slip on black grounds. When Bivins published his book, he was unaware that a dish nearly identical to the example illustrated in figure 1 survives with a history of descent in the Shoffner family of Alamance County.[37] The 1787 tax list for the St. Asaph’s district lists Michael Shoffner Sr. and his sons, Michael Jr., Martin, Frederick, and George.[38] The elder Michael and his wife, Margaretha Fogleman (Vogleman), were born at Frankfurt am Main, Germany, and reputedly immigrated in the 1750s.[39]

The St. Asaph’s Tradition

A small flask with a dark brown ground serves as a point of departure for exploring the emergence and persistence of designs in Alamance County slipware (fig. 4). References to flasks and bottles occur in local inventories from the fourth quarter of the eighteenth century, but in most instances appraisers failed to specify whether such objects were ceramic or glass. Five “bottles” were listed in the 1792 inventory and estate settlement of Alamance County blacksmith Jacob Albright Sr., the most expensive of which was a “flask bottle” that sold for 4s.[40] One side of the small flask mentioned above is decorated with a vertically oriented fleur-de-lis (fig. 5) resembling those of molded form on the ends of seventeenth-century costrels from southwestern France, whereas the other side is decorated with four fleurs-de-lis radiating from the center of a stylized cross with dots representing pomettes, or bobbles.[41] As Hyacinthe Rigaud’s Cardinal de Bouillon (fig. 6) and Antoine Raspal’s Portrait de Jeune Fille en Costume d’Arles (fig. 7) suggest, crosses with fleur-de-lis were associated with both Catholicism and Protestantism in France.[42] The Huguenot cross, hanging from the neck of Raspal’s sitter, differs from its Catholic counterpart in having a dove suspended from the bottom. Although the origin of the Huguenot cross is obscure, it appears to date from the late seventeenth century. The prominence of fleurs-de-lis in the decoration of the flask suggests that some of the earliest motifs in Alamance County slipware originated in an area of French cultural influence.

For Huguenot artisans, craft was a vehicle for preserving and expressing cultural and religious identity. In Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenots’ New World, 1517–1751, historian Neil Kamil asserts that French Protestant artisans used their trades to develop “portable and individualistic modes of personal security.” According to Kamil, the earliest proponent of that strategy was Huguenot alchemist, natural philosopher, and potter Bernard Palissy, who predicted the fall of La Rochelle in 1628. Palissy chose the snail, which is ubiquitous in his rustic faience, as a metaphor for “artisanal security.” Like snails, which construct their shells from the inside out, use stealth to evade their predators, and develop a symbiotic relationship with their environments, Huguenot artisans forged “containers of the soul hidden inside the self mastered body.” By guarding the secrets of their craft and developing subterranean patronage networks to satisfy and influence consumer demand, Huguenot artisans accessed, manipulated, and appropriated aspects of the dominant culture.[43] The cross design on the flask may have functioned in much the same way as Palissy’s snail, its meaning transparent to some but opaque to others. Given the Loy family’s Huguenot origins and long-term involvement in the Alamance County potting trade, it is noteworthy that the cross motif persisted there until the mid-nineteenth century.

Three other pieces of slipware appear to be by the decorator of the flask. The dish illustrated in figure 8 was formerly attributed to Rudolph Christ but differs from contemporary Moravian examples in having a rim that is rectangular in cross section rather than rounded and undercut (fig. 9). The marly is decorated with imbricated triangles that alternate in direction, and the cavetto features a stylized plant with a large flower represented by a fylfot and smaller flowers represented by white dots with red perimeters and green jeweling (fig. 10). The latter motif also occurs on the shoulders of the small flask (fig. 11), but in that context it may have mimicked wire or bone inlay, commonly found on European powder flasks from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (fig. 12). Fylfots are common on slipware and other decorative arts from rural areas of central Europe and regions of the American backcountry where Germanic families settled, but they do not appear on any objects made by Moravian craftsmen in North Carolina. Most of the first-generation artisans at Bethabara and Salem had learned their trades in congregation towns in Europe and America.

Much of the ornamental and compositional vocabulary introduced by the first generation of St. Asaph’s potters remained intact for more than seventy years. An Alamance County dish likely made by Solomon Loy between 1825 and 1840 has a fylfot in the center of the cavetto and triangles around the perimeter. His triangles can be read as visual analogs for the imbricated triangles on the dish illustrated in figure 8.[44]

Figure 13 shows the site of a pottery owned by Jacob Albright Jr., and sherds recovered there (figs. 14-17) document the production of earthenware with dark brown and black grounds and slip colors similar to those on the flask and dish illustrated in figures 4 and 8.[45] The decorative vocabulary of Albright’s pottery included marbleizing—a technique rare in Southern slipware—as well as trailing in both stylized and naturalistic modes (figs. 15, 16). Most of the fragments are from dishes, but base remnants from three mugs with polychrome banding (fig. 17) indicate that Albright’s pottery also made decorated hollow ware (fig. 18). In contrast, there is no archaeological evidence for the production of slip-decorated hollow ware at Moravian sites. The designation “potter” appears next to Albright’s name in the 1800 tax list for the St. Asaph’s district, but it is unclear whether he worked in that trade or provided land and financing for a pottery operated by his son-in-law Henry Loy (1777–1832).[46] The Albrights were prominent landowners in Alamance County, making either scenario possible. “An Inventory and an Account of Sales of the Estate of Jacob Albright Decd,” dated March 24, 1825, lists “two potter’s wheels, a glaze mill, a clay mill, a grindstone, a pipe mold, and a stove mold”—a sufficient amount of equipment for a modest workforce.[47] In 1780 the pottery in Salem had three wheels, a glaze mill, and a variety of pipe, plate, and tile molds plus at least five workmen.[48]

Archaeology conducted at pottery sites associated with Solomon Loy’s brother Joseph also yielded fragments of earthenware with black slip grounds and polychrome decoration. Among the most revealing is a handle fragment from a small pitcher or other hollow-ware form discarded at Joseph Loy’s pottery, which was in operation from about 1833 to the 1850s. The upper edge of the handle is decorated with a stylized grass motif in green over white slip (fig. 19). Similar designs occur on the handles of earlier examples of hollow ware from the St. Asaph’s tradition, including the tankard illustrated in figure 18. Alamance County potters used a variety of motifs on handles, such as circles with dots in the center, zigzag lines, and cross-hatching. The occurrence of polychrome slipware with black grounds at sites where Henry, Joseph, and Solomon Loy worked suggests that members of their family were responsible for much of the decorated earthenware attributed to Alamance County. If Martin Loy was the progenitor of the St. Asaph’s tradition, it would be reasonable to assume that he trained at least one of his sons. George and John Loy would have been eligible for apprenticeship during the early 1760s, followed by their brother Henry a few years later.

Alamance County potters clearly were producing slipware during the last quarter of the eighteenth century if not before. Establishing a precise chronology for this material is problematic, but date ranges can be assigned by comparing the decoration on surviving examples with that on artifacts from similar cultures and contexts. The trailing on the dishes illustrated in figures 20–22 has parallels in painted decoration on chests attributed to Berks County (figs. 23, 24), where members of several Alamance County families initially settled. Motifs occurring on both groups of objects include stems with jeweled edges, awkwardly perched birds, and both abstract and naturalistic plant forms. The chests, which probably represent the work of at least three decorators, bear dates ranging from 1776 to 1803. An example dated 1784 belonged to Heinrich Foust, who had the same great-grandfather as the Fousts who settled in Alamance County.[49]

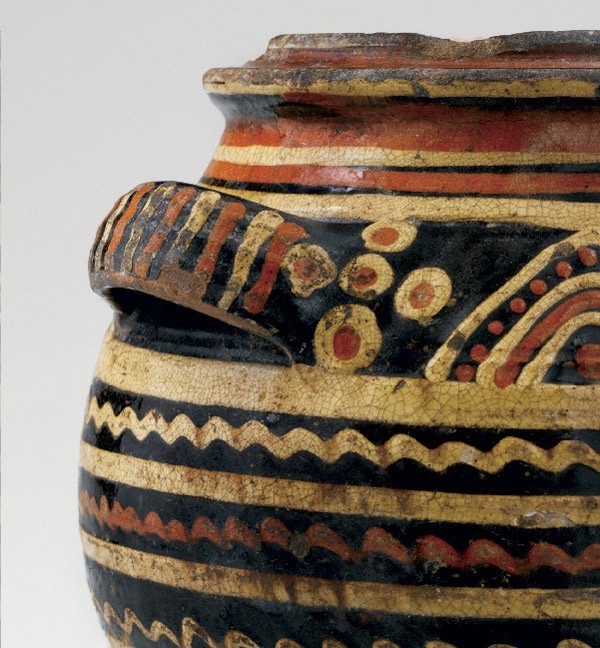

With their brilliant yellow and red slip decoration and lustrous black grounds, the dishes illustrated in figures 20–22 are benchmarks for understanding the morphology of that form in the St. Asaph’s tradition. All have marlys with the same sequence of concentric and wavy trailed lines, and cavetti with stylized or naturalistic motifs. The cavetto decoration on the dish illustrated in figure 20 is almost completely abstract, featuring a stylized plant encircled by a wide band and undulating vines with jeweled edges and flowers.[50] The decorator used similar jeweling around the upper flower of the dish illustrated in figure 21. Although the plant motif on that example is more naturalistic, its serpentine stem and tightly clustered, comma-shaped leaves are larger versions of those on its abstract counterpart (fig. 25). The ornament on the remaining dish (see fig. 22) relates most closely to that on the naturalistic example (see fig. 21). Their large leaves are basically the same, having peaked lobes, yellow slip outlines, and red slip interiors. The bird on the dish illustrated in figure 22 is unique in North Carolina slipware, although avian subjects are common in earthenware from Pennsylvania, Great Britain, and Europe. Dishes with birds depicted in a similar manner occur on slipware from Hessen, Germany, by the mid-seventeenth century.[51] Several of the families that emigrated from the Palatinate to Berks County and relocated to southeastern Guilford County and southern Alamance County were from that part of Germany.

In addition to being by the same decorator, the dishes illustrated in figures 20–22 may have been thrown by the same hand (fig. 26). They differ significantly from contemporary Moravian examples (see fig. 9) in having little to no visible booge at the rear and rims that are somewhat rectangular in cross section. The Alamance County dishes are also unmarked, whereas those made at Bethabara and Salem frequently have either Roman or Arabic numerals that were incised on the back before firing. No slipware from the St. Asaph’s tradition is marked in that manner.

Another dish that appears to date from the late-eighteenth or very early nineteenth century (fig. 27) introduces details that persisted in Alamance County slipware for decades: cymas arranged in a chainlike pattern and motifs resembling abutting teardrops with dots in the middle and at each end. Variations of the latter device also occur on Germanic pottery, as well as on dishes attributed to William and Thomas Dennis of Randolph County. Although there is not enough evidence to attribute this dish or the preceding examples to a specific craftsman, it is clear that Jacob Albright’s pottery produced earthenware decorated in a similar manner. A fragment recovered at his site (fig. 28) has petals that extend to the edge of the cavetto and are shaped like those on the upper flower of the dish illustrated in figure 27. Several Pennsylvania dishes with flowers oriented in a similar manner are known, and most date from the late 1760s to the 1790s.

Related dishes likely made between 1790 and 1820 reveal that the stylistic repertoire of Alamance County’s slipware potters was both cohesive and complex. Although no two motifs on these objects are the same, all have cavetto designs that radiate from the center. One has imbricated triangles emanating from a circle with a ring of jeweled dots and a simple grass motif in the middle (see fig. 1); one resembles a starburst, with alternating lines of red and yellow slip intersecting in the center (fig. 29); one has bisecting fronds of stylized leaves (fig. 30); and one has a cruciform motif with dots at the tips and leaves at the intersections (fig. 31). The design in figure 31 has antecedents in the flask illustrated in figure 4 and is a clear precursor to Solomon Loy’s simple cruciform motif (see fig. 51). The marly decoration on these dishes is equally varied, featuring clusters of stylized grass separated by lunettes (see fig. 1), an undulating vine with jeweled, comma-shaped leaves (see fig. 29), small clusters of grass extending from the inner edge to the rim alternating with similar clusters oriented in a counter-clockwise pattern (see fig. 30), and lozenge-shaped panels with marbleized centers and jeweled perimeters separated by interconnected cymas and straight and wavy lines (see fig. 31). The decorator responsible for this work was skillful and efficient. On the dish illustrated in figure 30 he applied all of the white slip first, then the red, then the green. Although working rapidly, he was able to produce a cavetto design that seems almost stenciled.

The bodies and profiles of these dishes also indicate that they are from the same pottery. All are made of pink- to buff-colored clay and have rounded, rolled rims (fig. 32), and two (see figs. 29, 31) have fluted separators stuck to their bottoms (fig. 33). The dish illustrated in figure 1 and the identical example that descended in the Shoffner family also have post-production marks inscribed on their bases (fig. 34).[52] Similar marks occur on dishes made by other Alamance potters, including Solomon Loy.

On the bottom of another dish (fig. 35) are the letters E and K, which appear to have been inscribed by the same person whose initials appear on the dish illustrated in figure 1. In both examples the E curls at the top and bottom and the body and serifs of the K are virtually identical (figs. 34, 36). The cavetto ornament on the dish illustrated in figure 35 includes stylized fronds that extend from the center like those on the example shown in figure 30, but the trailing is clearly by different hands. The profile of the dish illustrated in figure 35 also differs from those of the examples with black grounds in having a more pronounced cyma shape and a relatively square, unrolled rim.

Another dish by the decorator of the example shown in figure 35 has a fernlike design in the cavetto and grass clusters alternating with broad comma-shaped leaves with serpentine stems on the marly (fig. 37). Cognates for the latter detail can be found in slipware from many areas of German cultural influence, including Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and Salem, North Carolina (fig. 39).[53] An exceptionally rare punch bowl (fig. 40)—related to the dishes illustrated in figures 35 and 37—presents a more refined expression of the leaf-and-serpentine-stem motif. Indeed, in its precise and methodical application, the trailing on the bowl is closer to that on the dishes illustrated in figures 1 and 29–31 than those shown in figures 35 and 37. The production of a vessel associated with punch, which was almost exclusively a British libation, raises a number of questions. Was the bowl commissioned by a patron of British descent, made for a public house that served punch, or simply inspired by English bowls that made their way into the Southern backcountry during the last quarter of the eighteenth century? The latter hypothesis seems most likely in light of the decoration on the exterior. If the maker had wished to mimic contemporary English creamware, he simply could have coated the bowl with white slip and fired it with a clear lead glaze. Moravian potters in North Carolina produced imitation creamwares with tortoiseshell colors in that manner.

The earliest Alamance County dishes with white slip grounds appear to date from the first quarter of the nineteenth century (figs. 41, 42). With their coved profiles and delicate squared rims (fig. 43), these dishes are closer in shape to those made by Solomon Loy than the examples with black slip grounds (see fig. 32). Continuities with earlier examples of Alamance County slipware are, however, evident in the decoration of the dishes illustrated in figures 41 and 42. The central design on the first (see fig. 41), which can be read as either a geometric composition or a stylized flower, has clear antecedents in the dish illustrated in figure 1 and a nearly identical example that descended in the Shoffner family. On the white dish the decorator simply substituted a central dot and perimeter lunettes for the stylized grass motif and imbricated triangles of the black example (fig. 44). Similarly, the origin for the abstract plant in the cavetto of the other white dish can be found on several examples of slipware from the St. Asaph’s tradition (fig. 45), including the dish illustrated in figure 20 and two early pitchers (see figs. 46, 56).

The term pitcher appears to have entered use in the central piedmont region of North Carolina during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, whereas hollow ware vessels with handles and pouring spouts were referred to as “jugs” in most other areas well into the nineteenth century. Jacob Albright Sr.’s inventory listed four “pichers” ranging in value from eight pence to 3s. 1d., and the stock in his son’s pottery included nine pitchers with three different values. Jacob Jr.’s pottery also produced narrow-neck jugs in at least two sizes.[54]

The pottery responsible for the pitchers shown in figures 46–48 appears to have been in operation from at least the late eighteenth century to the 1820s. The plant motifs on the sides and front of the earliest example (fig. 46) have flowers trailed in much the same manner as those in the center of the dish illustrated in figure 20. As is the case with most decorated hollow ware attributed to Alamance County, the principal motifs on the pitcher are set in panels. To frame their designs, local potters used straight and wavy lines, rows of dots, stacked dashes, and interconnected cymas. A fragmentary pitcher found under the floorboards of a dormitory constructed in 1822 at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (fig. 47), has two of those details as well as rows of tiny lunettes with white dots in the center.[55] The arcaded vine-and-leaf decoration on the base resembles designs on British mocha ware, but the slip was applied in an entirely different manner.[56] All of the pitchers in this group have rounded feet, and the intact examples feature nearly identical moldings on their rims and shoulders. The handle on the earliest pitcher (see fig. 46) has cross-hatching on the upper edge and multiple finger impressions on the terminal, whereas the handle on the later example (fig. 48) is decorated with simple grass motifs and has a single thumb impression (fig. 49). Three-leaf grasses are common in Alamance County slipware, occurring as late as the mid-nineteenth century in pottery by Solomon Loy (figs. 50, 51).

Two smaller pitchers with black grounds (figs. 52, 53) might be from the same pottery that produced the preceding examples. Both have identically molded rims (fig. 54) that relate very closely to those on the larger pitchers (see figs. 46, 48, 49), pulled strap handles with deep thumb impressions at the terminal (fig. 55), and small rounded feet. The pitcher illustrated in figure 53 is a rare survivor, because earthenware overfired to that degree usually was discarded at the production site. In contrast, the other pitcher fired perfectly and displays almost no sign of use (see fig. 52). The potter used iron and manganese in almost equal proportion to produce its purple-black ground.[57]

The pitchers illustrated in figures 56 and 57 differ from the preceding examples in having proportionally larger openings, broader necks, and less prominent spouts and feet. At the same time, the abstract plant motifs in the upper panels of the pitcher with the white ground are clearly related to those on the pitcher illustrated in figure 46. The decorator of the former object used rows of dots and vertical lines to frame the upper panels and bands of slip to separate them from the repeat of fronds, lunettes, and imbricated triangles below. Although the pitcher with the red slip ground (fig. 57) has less complex trailing, its rim and handle have delicate moldings and its midsection is defined by a series of fine concentric lines (fig. 58). Similar moldings occur on the handles, bodies, and lids of other hollow ware forms attributed to Alamance County (see figs. 74–78).

A fragmentary pitcher (fig. 59), which appears to be from the same pottery that produced the examples illustrated in figures 46 and 48, suggests that some early motifs associated with the St. Asaph’s tradition degenerated over time. The abstract plant decoration is clearly related to that on the dish and pitcher illustrated in figures 20 and 46, but the stem has lost its dramatic serpentine shape and the curled tip of the flower is much less defined (fig. 60). On a contemporary dish that probably represents the work of Solomon Loy, or another potter of his generation, the leafy tip of the flower is omitted (fig. 61).

Similar continuities in form and decoration can be observed in sugar pots made in and around Alamance County (figs. 62-65). References to the form occur in local inventories from the 1770s well into the nineteenth century.[58] When the remainder of Jacob Albright Sr.’s estate was dispersed in 1812, a sugar pot and “sugar dish” sold for 2s. 6d. apiece.[59] The 1825 inventory of his son Jacob’s pottery listed one sugar pot valued at 13¢, attesting to their continued popularity. In his seminal article “A Note on Early North Carolina Pottery,” decorative arts scholar and dealer Joe Kindig Jr. stated that several examples he acquired during the early 1930s still contained sugar. Obviously these pots could have been used for the storage of other goods. A “sugar Pot & Peas” brought 31¢ in the 1830 estate sale of John Albright, Jacob Jr.’s brother.[60]

As was the case with several dishes and pitchers from the St. Asaph’s tradition, most of the surviving sugar pots were formerly attributed to Moravian potters based on mistaken assumptions about their formal characteristics and references to sugar bowls in inventories of the Salem pottery.[61] In those inventories, entries for sugar bowls almost invariably occur adjacent to those for teapots, indicating that the former were tableware rather than storage vessels.[62] Archaeology at Moravian sites has yielded fragments of sugar bowls with tortoiseshell colors and swirled slip decoration but no hollow ware with abstract or naturalistic trailing. Alamance County potters made lidded “sugar dishes,” condiment pots (fig. 66), and small bowls (fig. 67) for table use, but their forms and decorative techniques have no parallel in the North Carolina Moravian tradition.

All of the sugar pots from the St. Asaph’s tradition are ovoid with horizontal loop handles that are attached high on the body and angled slightly upward. As Kindig noted, lidded pots from Pennsylvania typically have vertical loop handles or horizontal lug handles. All of the handles on their Southern counterparts are pulled and feathered into the shoulder. On the most elaborate sugar pots, slip-trailed designs help mask the attachment points (figs. 68, 69). Many handles are molded (see fig. 69), but those of some later pots are plain (see fig. 65).

One of the earliest sugar pots from the St. Asaph’s tradition has a dark brown ground and thick slip decoration resembling that on the dish with the fylfot flower (see figs. 8, 69). The pot is unusual in having a flanged rim, but a lid that appears to be by the same decorator (fig. 70) suggests that the pottery responsible for the former object also made sugar pots with plain rims. The diameter of the lid and its inner flange indicates that it was made for a vessel with an unusually broad opening, such as that of the sugar pot illustrated in figure 71. The latter object and lid were “married” prior to April 1935, when they appear together in an advertisement by Kindig.[63]

Only one other local sugar pot with a flanged rim is known (fig. 72). It is almost certainly from the same pottery that produced the example illustrated in figure 68 but is later in date and decorated by a different hand. Like the early flask (see fig. 4), the sugar pot illustrated in figure 72 has cross-shaped motifs with fleurs-de-lis extending from the center. The slip on the pot is much thinner and migrated during firing, which gives it the appearance of having been applied with a brush when actually it was trailed. In its application and attenuated form, the cross and fleur-de-lis on the sugar pot are much closer to the decoration in the cavetto of the dish shown in figure 31 than the trailing on the flask (figs. 4, 73).

The sugar pots illustrated in figures 74 and 75 are among the most refined examples of hollow ware from the St. Asaph’s tradition. Both have shoulders defined by fine concentric lines, pulled handles with fluted moldings (figs. 76, 77), and small round feet. The even spacing and consistent depth of the flutes makes these handles appear extruded, but they were probably produced with a rib or a thin, smooth stick.[64] Although possibly from the same pottery, these pots clearly were decorated by different hands. The trailing on the example with the reddish orange slip ground (fig. 74) is more accomplished and relates very closely to that on the punch bowl (see fig. 40), whereas the decoration on the other sugar pot (fig. 75) is more heavy-handed, resembling that on the tankard shown in figure 18.

Only two sugar pots with white slip grounds are known (see figs. 62 [right], 78). The example illustrated in figure 78 has a twentieth-century history of descent in the Huffman (Hoffman) family of southeastern Guilford County and southern Alamance County.[65] Migration of the polychrome decoration, which is most evident on the bands at the shoulder, indicates that the pot was fired upside down. Although this differs from most of the surviving examples, potters probably arranged their hollow ware in whatever fashion facilitated efficient loading of their kilns. The Huffman pot is also distinguished by having handles that break sharply as they return to the body, notched terminals that resemble cut-card work in metal (fig. 79), a molded rim, and a lid with an acorn-shaped finial. The only other object with a comparable finial is the condiment pot shown in figure 66.[66]

The Huffman pot probably dates from the first decade of the nineteenth century, like most of the white slipped dishes from the St. Asaph’s tradition. Sugar pots from this period often have handles that are indistinctly molded and seem almost vestigial (see figs. 64, 65). Otherwise the form of these nineteenth-century examples differs only slightly from that of their eighteenth-century counterparts.

Two other sugar pots have histories of descent in Alamance County families. The example with the white slip ground in figure 62, right, was purchased at an auction of the Crouse family estate just a few miles southwest of Burlington, near the Guilford County line, and the pot illustrated in figure 78 descended in the Johannes Löffler (Spoon) family along with a confirmation certificate done for his son and namesake in 1779 (figs. 63, 80).[67] The Löfflers originally settled in the St. Asaph’s district, where Johannes Sr.’s widow, Sarah, is listed on the tax list in 1788.[68] The couple had moved from Pennsylvania to southern Alamance County, by March 29, 1772, when they purchased one hundred acres of land “on the waters of Stinking Creek” from James McCarroll.[69] Family genealogies suggest that the Löfflers traveled with a party that included members of the Shoffner and Fogleman families.[70] The elder Johannes’s brothers Adam and Christian also moved to Alamance County and are listed on the 1792 tax list for the St. Asaph’s district.[71] The Löfflers apparently worshiped at the Brick Church, which may explain why Guilford County is cited as the place of confirmation on Johannes Jr.’s certificate.[72]

The Löffler pot is almost certainly from the same manufactory as four of the sugar pots illustrated in this article and three not shown.[73] Some vary in shape—one is squat and spherical (fig. 63), two are similar but have a sharper break at the shoulder (fig. 64), and five are ovoid (fig. 65)—but their clay bodies, thin pulled handles, and shoulder incising are remarkably similar. These pots appear to be later than those shown in figure 62; however, their conical lids and embryonic finials suggest a direct connection. Similar “generational” parallels can be drawn between many of the hollow ware and dish forms (see figs. 48, 50, 68, 74) discussed above. This should come as no surprise, given the fact that some of this slipware likely represents the work of fathers and sons. There can be little doubt, for example, that Solomon Loy either trained under or worked in the shadow of the potter responsible for the dishes illustrated in figures 1 and 29–31 (figs. 81, 82). Although there is no conclusive evidence that Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery was responsible for the earlier dishes (figs. 1, 29–31), the fact that Henry Loy worked and presumably trained his sons there lends credence to that theory. Albright’s pottery was probably one of the most important factors in the persistence of form and decoration in the St. Asaph’s tradition.

Continuity

Slipware from the St. Asaph’s tradition challenges one aspect of folklorist Henry Glassie’s assertion that backcountry decorative arts changed little over time but considerably over space. The styles and technologies introduced by the earliest potters who settled in southern Alamance County coalesced in southwestern Germany, arrived with immigrant craftsmen, and persisted for nearly one hundred years. Unlike some areas of the backcountry, where interactions with different ethnic groups or various social and economic forces led to the assimilation of Old World craft traditions, the interrelated and interdependent Germanic communities of southeastern Guilford County and southern Alamance County were resistant to change. The cruciform motif, which found its last expression in Solomon Loy’s slipware, attests to the strength of artisanal and family traditions in that area of the piedmont (fig. 83).

Stanley South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999). John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972).

Philip Otterness, Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2004), pp. 9–25. For more on the religious and constitutional sources of violence in the Palatinate, see Brennan C. Pursell, The Winter King: Frederick V of the Palatinate and the Coming of the Thirty Years’ War (Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate Publishing, 2003).

Otterness, Becoming German, pp. 20–21.

The passenger list for the ship Elizabeth lists the names and trades of adult males; see http://immigrantships.net/v4/1700v4/elizabeth17330827.html (accessed June 1, 2009).

David Warren Sabean, Power in the Blood: Popular Culture and Village Discourse in Early Modern Germany (1984; repr., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 9–10. For more on family relationships in southern German villages, see David Warren Sabean, Property, Production, and Family in Neckarhausen, 1700–1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Mark Häberlein, “German Migrants in Colonial Pennsylvania: Resources, Opportunities, and Experience,” William & Mary Quarterly 50, no. 3 (July 1993): 555–60. Philip Otterness refers to the Palatine migration of 1709 as a “migration of families” (Otterness, Becoming German, p. 19).

As quoted in Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement, and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717–1775 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), p. 76.

Diary of George Stolle, compiled by Adelaide Fries (Raleigh, N.C.: Department of Archives and History, 1968), p. 800. The churches mentioned by Stolle were probably those later known as Stoner’s Church (Alamance County), St. Paul’s Church (Guilford County), Friedens Church (Guilford County), and the Old Brick Church (Guilford County).

For a genealogy of the Clapp family of Guilford and Alamance counties, see http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~djwm/html/fam01711.htm (accessed June 1, 2009).

For a passenger list of the James Goodwill, see www.progenealogists.com/palproject/pa/1727jgood.htm (accessed June 1, 2009). For the Clapp family in Berks County and information on marriage into other families there and in North Carolina, see http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~djwm/html/fam01711.htm (accessed June 1, 2009).

For information on the Beaver Creek Church and its successor, the Old Brick Church, see www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ncalaman/brick.html (accessed June 1, 2009).

Genevieve E. Peters, Know Your Relatives: The Sharps, Gibbs, Graves, Efland, Albright, Loy, Miller, Snoderly, Tillman, and Other Related Families, microreproduction of typescript (Arlington, Va.: G. Peters, 1953), p. 8, North Carolina State Library, Raleigh.

For a list of the passengers on the ship Johnson, see www.ristenbatt.com/genealogy/shplst12.htm (accessed June 1, 2009). The names of Johannes and Anna Barbara Albright’s children are also given in an early deed: “Barbara Albracht . . . widow of John Albracht, deceased, together with Christian Albracht, yeoman, Jacob Albracht, wheelwright, Lodowick Albracht, wheelwright, they being the three sons of John Albracht, Philip Faust, yeoman, and his wife Mary (Magdalene) one of the daughters of the said John Albracht and Judith Albracht, another daughter of John Albracht” (December 12, 1752, deed book A-3, p. 27, as quoted in Peters, Know Your Relatives, p. 119).

See www.faustfamily.us/.

Members of the Albright family probably moved to North Carolina between 1762 and 1763. A Berks County deed made out in 1762 and proven on January 20, 1763, lists “Anna Barbara Albrecht, widow . . . of John Albrecht” along with sons Christian and Jacob and daughters Magdalene and Judith (Deed book a-3, p. 137, as quoted in Peters, Know Your Relatives, p. 119). Johannes and Anna Barbara’s son Ludwig is not mentioned, which suggests he might have been in North Carolina at that date. Ludwig purchased 325 acres of land in Orange (now Alamance) County from Henry McCulloh in 1763, and the following year his brother Jacob (referred to as James in one deed) bought two tracts totaling 415 acres (Register of Orange County, North Carolina Deeds, 1752–1768 and 1793, transcribed by Eve B. Weeks [Danville, Ga.: Heritage Papers, 1984], n.p.).

See note 13 above.

For genealogical information on the Foust family, see Howard Faust, Faust-Foust Family in Germany & America (Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, 1984), and www.faustfamily.us/.

Faust, Faust-Foust Family, D1–D5. Most genealogies of the Faust family do not include Anna Catrina Foust, who was twenty-one when she arrived on the ship Elizabeth; see www.olivetreegenealogy.com/ships/pal_eliz1733.shtml (accessed June 1, 2009). Anna Catrina might be the daughter of Johan Peter Foust and his first wife, Magdalena Adams, who died in 1713, shortly after giving birth to their son Peter.

Johannes moved to North Carolina after May 12, 1764, when he sold his land in Berks County, Pennsylvania, to his brother-in-law Christian Albright (Faust, Faust-Foust Family, p. d1 52). For marriages into the Albright and Snoderly families, see Peters, Know Your Relatives, pp. 120, 220–24. For Anna Catrina Foust, see note 18 above. Martin Loy purchased 251 acres of land in Orange (now Alamance) County in 1764 (Register of Orange County, North Carolina Deeds).

For passenger lists for the ships Loyal Judith (1732), Samuel, Harle, and Loyal Judith (1740), see http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~pagermanpioneers/ (accessed June 1, 2009).

Marriages, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche, Mussbach, film 488536. It is presumed that Martin was born between 1700 and 1705, since it was illegal to marry without parental consent before the age of twenty-five.

Hasslock Baptisms, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche, church in Mussbach, film 1418010.

Martin and Anna Margaretha are both listed as passengers; see www. progenealogists. com/palproject/pa/1741smark.htm (accessed June 1, 2009). Their daughter Catharina married Ludwig Adam Stehli in Mussbach on August 25, 1759. She died there on June 1, 1794 Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche, Mussbach, film 1418010.

See note 18 above.

The website www.voiceinverse.com/family/genealogy/ (search FOUST, select Person ID I904; accessed July 27, 2010) gives approximate dates for Martin and Anna Catrina’s children but some of the information provided in this site is incorrect. See note 30 below.

Lyman Chalkley, Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia: Extracted from the Original Court Records of Augusta County, 1745–1800, 3 vols. (1912; repr., Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1965–74), 3:73, 321. All three volumes are available online at www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~chalkley/ (accessed June 1, 2009).

Isaac Sharp, born at Langensbold, Isenberg, Hessen, was the first member of his family to immigrate. He arrived in Philadelphia on September 16, 1738, with his sons Isaac II (26), George (36), and Ernst (39). This generation settled in Berks and Lancaster counties, Pennsylvania. Isaac II had nine children: Ernest, George, John Joseph, Henry, Isaac III, Veronica, Margaret, Barbara, and Rebecca. Isaac III and his wife, Philopena Graves, moved from Pennsylvania to Botetourt County, Virginia, before relocating to Alamance County. Their children married into the Albright and Foust families. This information came from a message posted by Roger Sharpe on February 3, 2008, at http://genforum.genealogy.com/sharp/messages/5893.html (accessed June 1, 2009).

Orange County, NC Wills Vol. 2, 1775–1787, transcribed by Laura Willis (Melber, Ky.: Simmons Historical Publications, 1998), pp. 13–14. For John Loy’s marriage, see http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asbellm/genealogy/fam00937.htm; and Linda Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity: Earthenware and Stoneware Pottery Production in Nineteenth-Century North Carolina” (Ph.D. diss., Department of Anthropology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1997), p. 96.

Members of both families are listed on an 1803 communicant roll for Stoner’s Church, www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ncalaman/stoners.html (accessed June 1, 2009).

A December 1755 arrival date is cited, without a source, at www.voiceinverse.com/family/genealogy/ (search last name LOY, first name MARTIN, select Person ID I903; accessed June 5, 2009). This date might not be correct, since Register of Orange County, North Carolina Deeds refers to Martin Loy’s purchase of 251 acres of land in Orange (now Alamance) County from Henry McCulloh in 1765.

www.voiceinverse.com/family/genealogy/ (search last name LOY, first name MARTIN, select Person ID I903; accessed June 5, 2009). In 1775, Martin began distributing land to his heirs, with sons George and John receiving 120 and 121 acres, respectively. In his will of July 15, 1777, the elder Loy left an additional acre to George, and his land, plantation, and “moveable Estate” to John, with the caveat that “his beloved wife Catheriney” retain use of the latter property during her lifetime. Martin named George Loy and Jacob Albright Sr. his executors (Orange County, NC Wills Vol. 2, 1775–1787, pp. 13–14).

Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 95–103.

As quoted in ibid., p. 94.

For more on this idea, see ibid., p. 95; and Robert Blair St. George, The Wrought Covenant: Source Material for the Study of Craftsmen and Community in Southeastern New England, 1620–1700 (Brockton, Mass.: Brockton Art Center, Fuller Memorial, 1979), pp. 13–21.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, pp. 244–45. Bivins wrote that the dish illustrated in fig. 1 and several related pieces probably “represent the work of one man . . . whom we now presume to be Christ.” He referred to the slip motifs on that dish as “signatures” in John Bivins Jr., “Slip-decorated Earthenware in Wachovia: The Influence of Europe on American Pottery,” American Ceramic Circle Bulletin/ 1970–1971, no. 5 (1975): 100–106; and John Bivins Jr. and Paula Welshimer, Moravian Decorative Arts in North Carolina (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Old Salem, Inc., 1981), pp. 40–41, fig. 2-7.

Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 197–99.

The accession card file for the dish illustrated in fig. 1 indicates that in 1974 representatives of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, examined an identical example in the collection of S. S. Shoffner. He reported that the dish descended in his family and that they lived in Snow Camp.

Tax list for the St. Asaph’s district of Orange County, North Carolina, 1787, North Carolina State Archives (hereafter NCSA), Raleigh.

http://lmkmfamily.com (search first name MICHAEL, last name SHOFFNER, select Person ID I763; accessed July 27, 2010).

Inventory of the Estate of Jacob Albright [Sr.], submitted to court in February 1792 and settled in November 1795, loose estate papers, Jacob Albright file, NCSA.

For a drawing of a sixteenth-century costrel from Saintonge with a vertically oriented fleur-de-lis at each end, see Hans-Georg Stephan, Die bemalte Irdenware der Renaissance in Mitteleuropa (Munich, Germany: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1987), p. 211, fig. 201.

Alain Mérot, French Painting in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), pp. 202–4.

Neil Kamil, Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenots’ New World, 1517–1751 (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), pp. 1, 74–75, 194–95, 211–17, and passim; Neil Kamil, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Disappearance and Material Life in Colonial New York,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite and William N. Hosley (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1995), pp. 233–41.

Sotheby’s, New York, Important Americana, Furniture, and Folk Art, sale cat., January 16–17, 1999, lot 296.

The site from which the fragments were recovered is on a thirty-acre parcel that has been in the family of the current owner since the mid-1890s. Deed research suggests that the site was part of a much larger tract owned by members of the Albright family (see Jacob Albright to Joseph Albright, May 13, 1778, and Joseph Albright to Andrew Albright, August 13, 1778, as cited by Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton in “Solomon Loy: Master Potter of the Carolina Piedmont,” p. 134, n. 16, in this volume).

Henry Loy (1777–1832) was the son of John and the grandson of Martin. Tax list for the St. Asaph’s district of Orange County, North Carolina, 1800, County Tax Records, NCSA. The contents of Albright’s pottery were sold on March 24, 1825, and listed in “An Inventory and an Account of Sales of the Estate of Jacob Albright Decd,” NCSA. Among the items listed in the inventory of his property were “1 pair pipe molds” valued at 12¢, “1 turning wheel” valued at 10 1/2¢, and “1 mill” valued at 5¢. The pipe molds were purchased by Henry’s son John (Sale of the Property of Henry Loy Decd., 1832, loose estate papers, Henry Loy file, NCSA). The absence of pottery in the inventory suggests that Henry had either ceased production or transferred his stock-in-trade to another party, possibly one or more of his sons. Land transactions recorded between 1826 and 1839 involving two of Henry’s sons, William and Solomon, suggest that they were purchasing land and might have been relocating the pottery in the years prior to their father’s death (Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 98–103).

Albright’s stock-in-trade was small: 255 crocks, 62 basins, 20 dishes, 9 pitchers, 7 jugs, 2 cream pots, 2 pans, 2 “P pots,” and 1 sugar pot.

“Inventory of the things and tools in the Pottery, by Gottfried Aust in Salem, which had occurred new in March 1780,” Moravian Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, N.C.

For more on these chests, see Monroe H. Fabian, The Pennsylvania-German Decorated Chest (1978; repr., Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing for the Heritage Center of Lancaster County and the Pennsylvania German Society, 2004), pp. 128–32, nos. 84–91. The Foust chest is illustrated and discussed in Beatrice B. Garvan and Charles F. Hummel, The Pennsylvania Germans: A Celebration of Their Arts, 1683–1850 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982), pp. 30, 33, pl. 11.

John Bivins attributed the dish illustrated in fig. 22 to Christ and referred to the design in the center as a “bird of paradise” motif (Bivins, “Slip-decorated Earthenware in Wachovia,” pp. 103–4, fig. 11; Bivins and Welshimer, Moravian Decorative Arts, pp. 40–41).

For a fragmentary dish with a bird and the date 1659 trailed in the cavetto, see Stephan, Die bemalte Irdenware der Renaissance in Mitteleuropa, p. 112, fig. 106.

MESDA did not photograph the Shoffner dish, but its design and marks are described on the accession card for the dish illustrated in figure 1 (89.27).

Montgomery County jars with similar decoration are illustrated in Beatrice B. Garvan, The Pennsylvania German Collection (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982), p. 208, no. 10.

Inventory of Jacob Albright Sr.

E-mail from R. P. Stephen Davis, Archaeological Research Lab, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, to Luke Beckerdite, September 22, 2002.

The authors thank Robert Hunter for suggesting the connection to British pearlware.

John P. Kieckbusch, Report from Aspen Consulting on quantative energy dispersive spectroscopy performed on the pitcher illustrated in fig. 47, file no. 97056, February 18, 1997, facsimile copy in Luke Beckerdite’s papers.

For early references to sugar pots, see “Inventory of the estate of John Howell decd.,” Orange County Court, August 1774; “A True Inventory of the Effects of William Bolton Deceased,” Orange County Court, April 13, 1783; and “The Personal Estate formerly Belonging to James McCanles,” Orange County Court, May 1784 (Orange County Inventories 1758–1785, pp. 123, 165, 189). Orange County inventories also list forms described as “sugar boxes” and “sugar canisters,” but it is impossible to determine whether any were ceramic.

Document with heading “This 28th Day of August 1812. I as Executor of Jacob Albright & my Mother Cathy Albright have offered at public Sail the balance of What She my Mother was furnisht at the Last is as follows,” loose estate papers, Jacob Albright file, NCSA. Jacob Albright Sr. died in 1791; the inventory of his estate was submitted to court in February 1792.

Document titled “1830 Account of Sales of personal property of John Albright Decd,” loose estate papers, Jacob Albright file, NCSA.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, pp. 244, 249, fig. 257.

Entries for 17 sugar bowls occur adjacent to entries for 16 teapots in an inventory titled “Finished pottery ware that Rudolph Christ brought to the Salem Pottery from Bethabara as well as what was in the pottery here, and also what material and tools and equipment was here on 1st February 1789,” Moravian Archives, Southern Provence, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Advertisement by Joe Kindig Jr. in The Magazine Antiques 27, no. 4 (April 1935): 121.

John Bivins notes similarities between the handles of these objects in Moravian Potters in North Carolina, p. 254. Although he speculates that the handles might have been extruded, their tapering cross sections indicate that they were formed by hand.

This sugar pot reputedly came from the Vance Huffman estate sale near Burlington, North Carolina. Members of the Huffman family are listed on eighteenth-century tax assessments from the St. Asaph’s district and in the records of Old Brick Church (successor to the Church at Beaver Creek) in southeastern Guilford County.

Document with heading “This 28th Day of August 1812. I as Executor of Jacob Albright & my Mother Cathy Albright have offered at public Sail the balance of What She my Mother was furnisht at the Last is as follows,” NCSA.

The author thanks Bob Pearl for providing the recovery history of the sugar pots and fraktur. For information on the Löffler (Spoon) family, see www.spoongenealogy.com/histories/ nc.php. Johannes Löffler Jr. is buried in the cemetery of Low’s Lutheran Church, which was a successor of Old Brick Church in Guilford County.

Tax List for the St. Asaph’s District of Orange County, North Carolina, 1788, County Tax Records, NCSA.

See www.spoongenealogy.com/histories/nc.php.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Two sugar pots with sponged decoration like that on the examples illustrated in fig. 64 are in the collection of the Barnes Foundation (acc. nos. 01.09.33ab and 01.12.13ab). Another sugar pot in the collection of the Winterthur Museum is of the same basic form as the sugar pots illustrated in fig. 65 and is decorated with concentric and wavy lines in yellow and green.

One of the sugars pots is in the Winterthur Museum and two are in the collection of the Barnes Foundation.