Shop sign made during Gottfried Aust’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1773. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

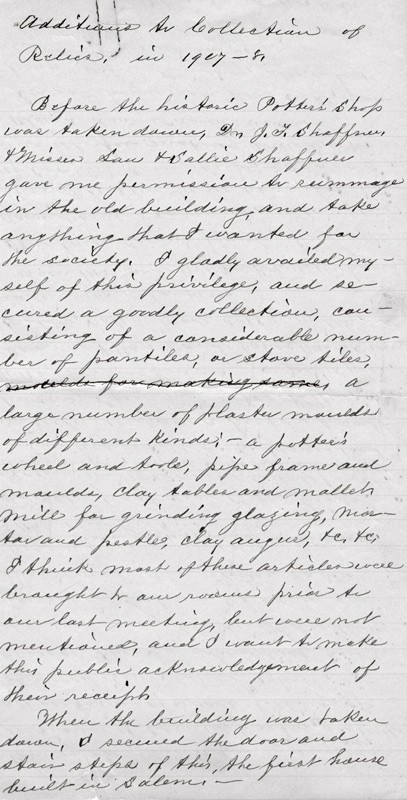

“Additions to Collection of Relics in 1907–8,” Wachovia Historical Society, Salem, North Carolina, 1908. (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

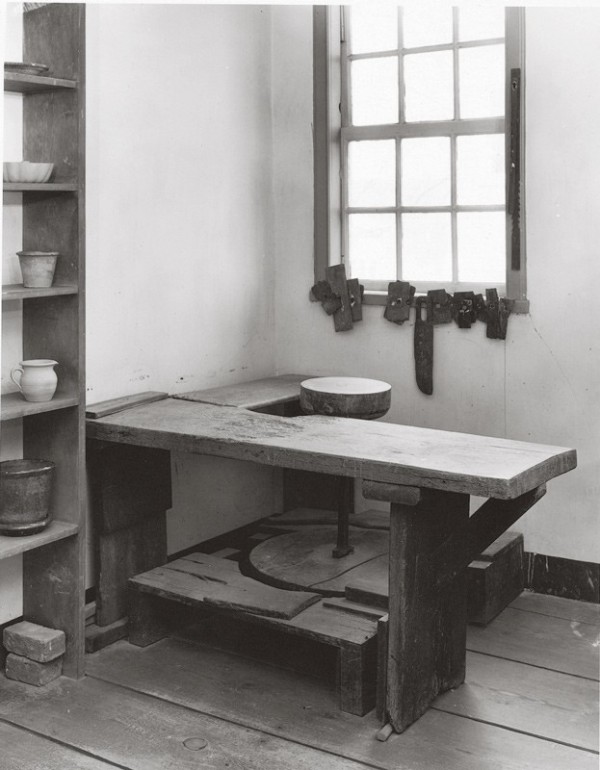

Potter’s wheel, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1756–1800. (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

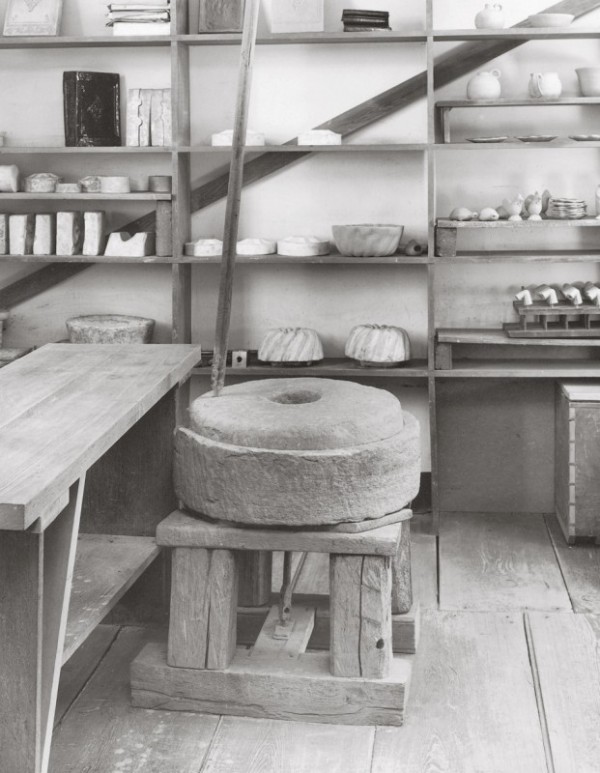

Glaze mill, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1756–1800. (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

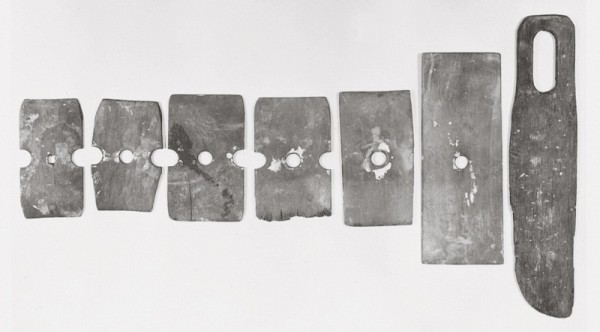

Ribs, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1820. Brass. (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

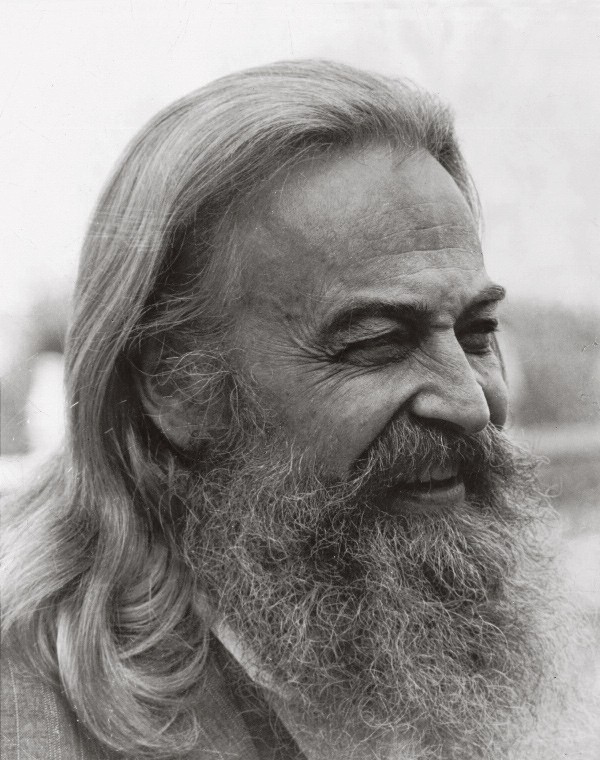

Photograph of Joe Kindig Jr., York, Pennsylvania, ca. 1960. Kindig was considered by many to be the most knowledgeable antique dealer of his generation.

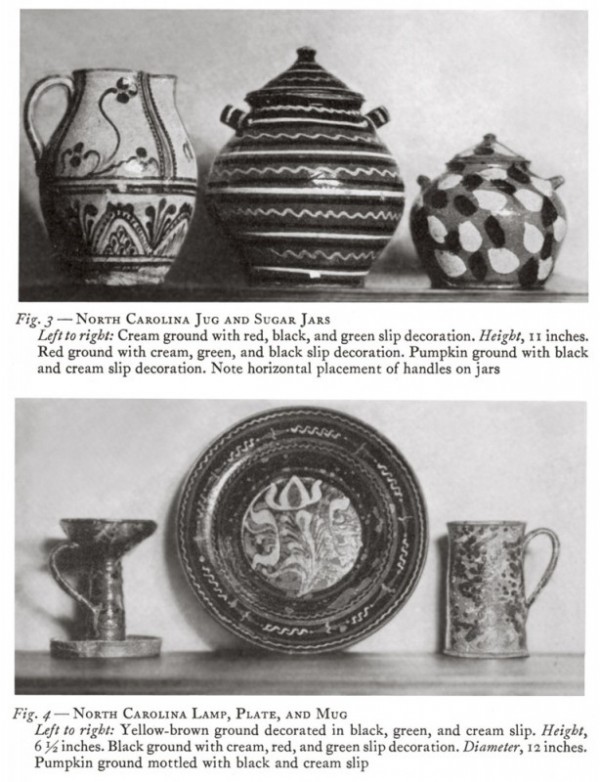

Joe Kindig Jr., “A Note on Early North Carolina Pottery,” The Magazine Antiques 27, no. 1 (January 1935): 15. The pitcher, large sugar pot, and dish are in the collection of The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan; the small sugar pot, fat lamp, and mug are owned by Old Salem Museums & Gardens. All of the pottery illustrated in Kindig’s article is now attributed to Alamance County, based on research presented in this volume of Ceramics in America.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1785–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, The Henry Ford.) Joe Kindig owned this dish and described it in “A Note on Early North Carolina Pottery” (fig. 7).

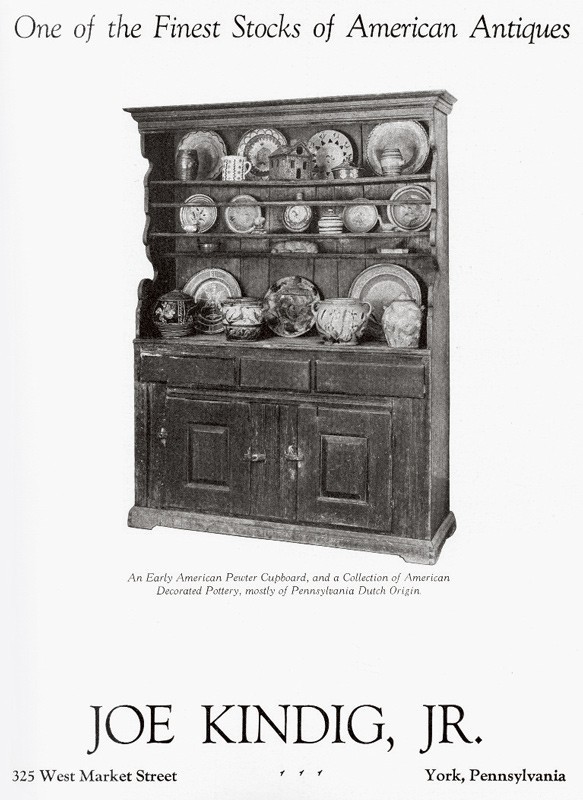

Advertisement by Joe Kindig Jr., The Magazine Antiques 27, no. 4 (April 1935): 121.

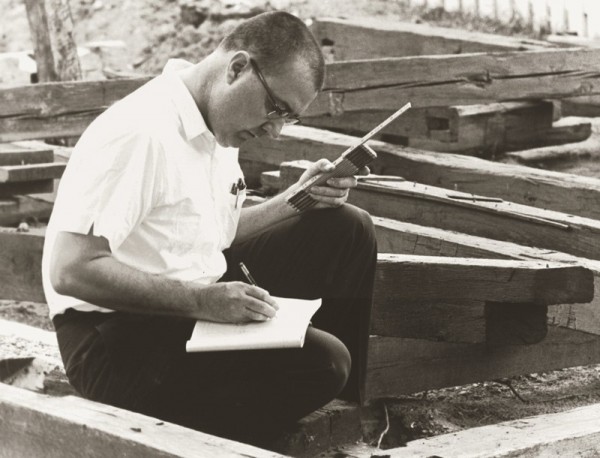

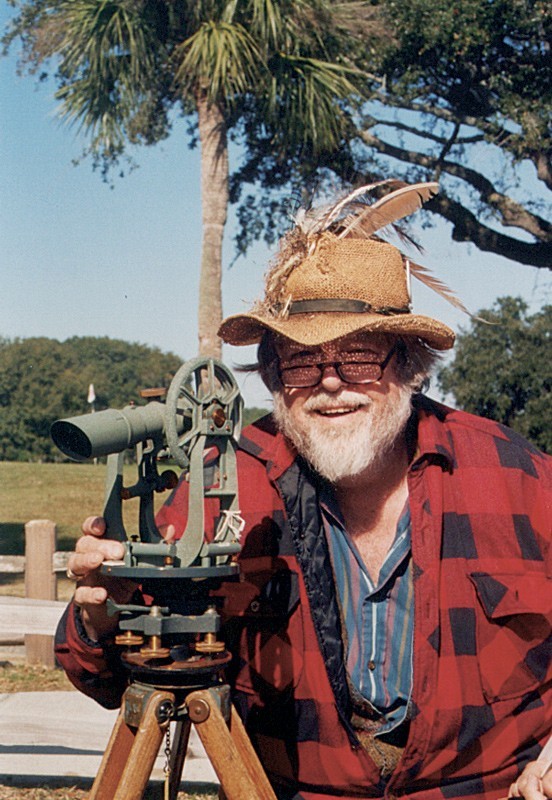

Frank Horton cataloging timbers from the Levering House, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1971.

View of a pottery display in the Boys School, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1956.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Stanley South, 2008. (Photo, Chester DePratter.)

Photograph of John Bivins Jr. and Bradford Rauschenberg taken for the dust jacket of their book The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820 (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 2003).

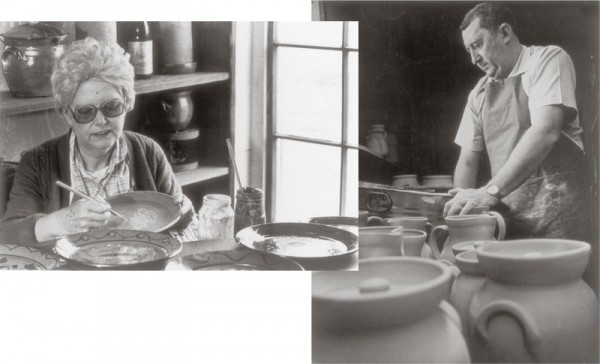

Left: Dorothy Auman, ca. 1982; right: Walter Auman, 1969. (Courtesy, Auman family.)

Interior view of the North Carolina Pottery Center, Seagrove, North Carolina, ca. 2008. This installation is reminiscent of the displays at the Seagrove Pottery Museum.

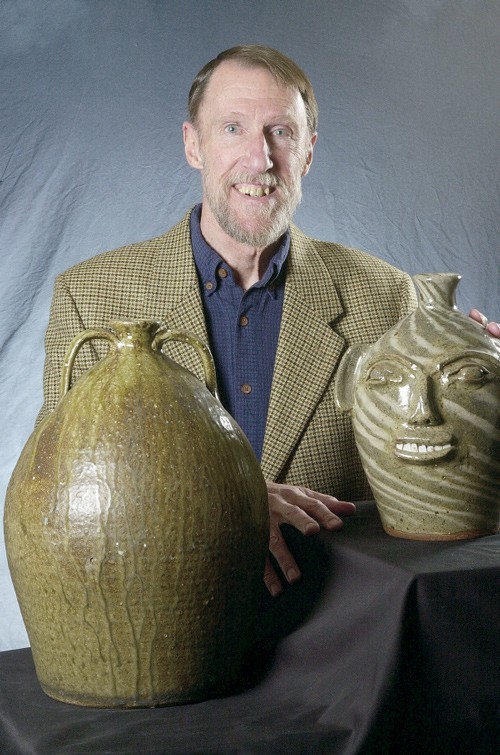

Charles G. Zug III, ca. 2004.

The 2009 and 2010 volumes of Ceramics in America are intended to serve as catalogs for Art in Clay: Masterworks of North Carolina Earthenware, a traveling exhibition co-sponsored by Old Salem Museums & Gardens, the Chipstone Foundation, and the Caxambas Foundation. As is the case with most new research, the information presented in these journals builds on earlier scholarship. This essay will examine the contributions of institutions and individuals who formed the first private and public collections of North Carolina earthenware and the scholars who first recognized the importance of that subject in the history of American ceramics.

Scholarly interest in the history of slipware transcends many centuries and world traditions. Numerous British ceramic historians writing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries lauded the artistic achievements of master potters Thomas and Ralph Toft while museums assembled landmark collections of highly decorative seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Staffordshire slipware.[1] In America, early ceramic historians also recognized slipware as a particularly significant artifact of indigenous manufacture. The most prominent of these early writers was Edwin Atlee Barber, who mined the Pennsylvania countryside in search of the sgraffito-decorated slipwares of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century German settlements. Writing in 1893 Barber confessed, “there are no products of the potter’s art more interesting to the antiquary and the collector than the rude ‘slipware-decorated’ pieces.”[2] Barber recorded many early examples of dishes decorated with both sgraffito and slip trailing but restricted his research and attributions to the Pennsylvania German products.

Writing slightly later, in 1926, John Spargo, another American ceramic historian, also asserted that “of all the types of early American pottery, none merits the serious attention of the collector to a greater degree than the slip-decorated slipwares.”[3] Spargo noted that after the publication of Barber’s work, many antique dealers instigated the practice of attributing all American slipware to Pennsylvania, although, he confided, a “great deal of the slip-decorated pottery that is offered by dealers—and quite honestly—as Pennsylvania pottery was actually made in Connecticut.”[4] Spargo also noted slipware production in New Jersey, New York, Vermont, Maryland, and Virginia, although he stopped short of acknowledging, at least geographically speaking, the existence of North Carolina slipware.

For many areas of the South, the history of collecting decorative arts has been predominantly regional. For those in the piedmont region of North Carolina, efforts to collect and preserve Moravian pottery began during the second half of the nineteenth century. A late-nineteenth-century issue of People’s Press described “POTTERY AND PIPES” in the Forsyth County exhibit at the North Carolina State Fair:

Past and present are combined in this department for there are plate molds bearing the stamp “R. C., Bethabara, 1788” and also 1789. Then there is a monster plate of earthenware used as a sign by Salem’s first potter. Pipes of a dozen varieties, and of useful design, are exhibited by D. T. Crouse, the largest maker of them in the State. He also shows flowerpots, vases for lawns and mantels, cake molds, hanging baskets &c., all tasteful and cheap, and all the products of his potteries.[5]

The “monster plate” sign (fig. 1) appears to have been lent to the Forsyth County exhibit by the Young Men’s Missionary Society of the Moravian Church, which between 1845 and 1895 assembled a collection of “curios from the mission fields, mineral specimens . . . stuffed birds, old coins, and local curiosities.” The society subsequently donated its collection, which included the sign, to the Wachovia Historical Society, which in the first half of the twentieth century took the lead in collecting Moravian artifacts.

A 1908 report suggests that the molds exhibited at the North Carolina State Fair came from the Schaffner family (fig. 2), who apparently retained ownership of Heinrich Schaffner’s pottery after it was taken over by Daniel Krause (Crouse). The report indicates that the Schaffners gave the Wachovia Historical Society a large group of tiles, molds, tools, and implements. All of these objects are currently in the collection of Old Salem Museums & Gardens under a custodial agreement with the historical society (figs. 3-5).[6]

The first serious scholar of North Carolina earthenware was Joe Kindig Jr., an antique dealer from York, Pennsylvania, who scoured the South for decorative arts during the depression era (fig. 6). By January 1935, when his article “A Note on Early North Carolina Pottery” was published in The Magazine Antiques, Kindig had learned enough about the subject to form conclusions that remain accurate today (fig. 7). As one might expect, he was acutely aware of features that distinguished North Carolina earthenware from contemporaneous Pennsylvania work:

I have never seen any sgraffito ware from North Carolina. All the decoration known to me is in slip. Nor have I seen any . . . plates bearing inscriptions, such as we frequently find in Pennsylvania. Such negative evidence, of course, does not afford proof that sgraffito and inscribed items were never made in North Carolina; but it is safe to say that they were, at least, very rarely produced.[7]

Kindig’s observations about the range of clays and slip grounds used by North Carolina potters suggest that he had studied wares from most of the earthenware traditions in the piedmont region. His reference to “pieces whose body is almost white” most likely alluded to Moravian work, which occasionally was made with clay that fired to a light buff color. Similarly, illustrations in Kindig’s article and his description of objects with “chocolate” to “almost black” slip grounds (fig. 8) and “initials scratched on the back” attest to his familiarity with pottery from Alamance County.[8]

One of Kindig’s most interesting observations pertains to the survival of “sugar jars,” which he described as the most common form other than dishes. Although lidded containers could have been used for all manner of dry goods, he claimed to “have found several that still contained sugar” and noted that sugar jar was the term by which “these vessels are locally known.”[9] Inventory research conducted for “Slipware from the St. Asaph’s Tradition” by Luke Beckerdite, Johanna Brown, and Linda Carnes-McNaughton in this volume indicates that Alamance County appraisers began using the term sugar pot by the 1770s. Moreover, Kindig noted how the form of North Carolina sugar pots was distinctive:

The lidded jars of Pennsylvania are of a different shape, with straighter sides, larger mouth, and proportionally more expansive lid. The handles of Pennsylvania jars are usually set vertically. North Carolina jar handles, on the contrary, are invariably horizontal and often extremely small.[10]

In fact, all of the sugar pots recorded for this volume of Ceramics in America conform to the profile Kindig established more than fifty years ago.

Many examples of North Carolina earthenware in private collections passed through Kindig’s hands, but he also deserves credit for furnishing much of the North Carolina slipware on view in museum collections today. Objects illustrated in his January 1935 article and subsequent advertisement in The Magazine Antiques (fig. 9) are now in the collections of The Henry Ford, The Barnes Foundation, and Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

Since its establishment in 1950, Old Salem Museums & Gardens has become the center of the study of North Carolina earthenware. The person most directly responsible for that is Frank L. Horton (fig. 10), who supervised the restoration and reconstruction of approximately fifty buildings in Salem and Bethabara and acquired most of the furnishings for them (fig. 11).[11] Early accession records provide little information on the histories of ceramic objects in Old Salem’s collection, but it is clear that Horton purchased a significant amount of earthenware from Kindig, then donated it to Old Salem.[12] One gift in 1959 included more than fifty examples (figs. 12, 13).

From the outset Horton recognized the artistic appeal of North Carolina earthenware. During the 1950s he displayed slipware in the bay window of the administration building to show the residents of Winston-Salem and visitors the types of objects Old Salem was collecting. One important local source was a man named Willie Jones. While walking from the Happy Hill community south of the restoration to downtown Winston-Salem, Jones noticed Horton’s display and asked if Old Salem was interested in purchasing comparable objects. Horton answered affirmatively and Jones returned the following day with an Alamance County sugar pot (fig. 14) that he had gotten from an acquaintance; subsequently he sold Horton two other major pieces of slipware from the same source.[13]

Horton’s research on Moravian decorative arts has contributed immensely to the study of North Carolina earthenware. To facilitate the restoration and interpretation of Bethabara and Salem, he created detailed profiles of virtually everyone who lived in those communities or was mentioned in the Moravian records. Comprising thousands of note cards filled with information transcribed from church documents, public records, and private papers, the files at Old Salem have served as the foundation for nearly every book and article written on Moravian decorative arts.[14] Without Horton’s work, the groundbreaking research presented in the 2009 volume of this publication would not have been possible.

All of the books and articles written on Moravian pottery owe an enormous debt of gratitude to archaeologist Stanley South, who conducted excavations at Bethabara and Salem during the 1960s (fig. 15). The artifacts he recovered at sites in those communities are benchmarks for understanding the Moravian earthenware tradition and its historical context. Although his book Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery was not published until 1999, the reports he prepared for the Bethabara excavations in 1966 and the Salem excavations in 1972 greatly informed the work of John Bivins Jr., Bradford Rauschenberg, and all of the authors who contributed to the 2009 volume of Ceramics in America.[15] South was also responsible for locating and publishing artifacts from the site of John Bartlam’s manufactory in South Carolina. Journeymen from that manufactory were catalysts for the Moravians’ efforts to produce creamware.

John Bivins Jr. and Bradford L. Rauschenberg deserve equal billing as leading twentieth-century scholars of the Moravian earthenware tradition (fig. 16). Bivins’s book The Moravian Potters in North Carolina and Rauschenberg’s articles “Escape from Bartlam: The History of William Ellis of Hanley” and “Carl Eisenberg’s Introduction of Tin-Glazed Ceramics to Salem, North Carolina, and Evidence for Early Tin-Glaze Production Elsewhere in North America” offer valuable insights on their subjects to this day.[16] Bivins’s chapters on the master potters and their workmen may be the best account of the day-to-day operation of an early American pottery in print. Rauschenberg was the first scholar to argue that some of the slipware Bivins attributed to Rudolph Christ (see fig. 12) was not part of the Moravian tradition, a theory substantiated by articles on the St. Asaph’s tradition and Solomon Loy in this volume.

Seventeen objects illustrated in Moravian Potters in North Carolina were part of an extensive collection assembled by George and Carolyn Waynick. From their house in Old Salem, they scoured the piedmont region of North Carolina for antiques, particularly those associated with the Moravians. The Waynicks generously allowed the staff of Old Salem Museums & Gardens and visiting scholars to study and publish their collection, which was featured in the June 1988 issue of Early American Life.[17]

As this volume of Ceramics in America reveals, much of the slipware formerly attributed to Moravian craftsmen was actually made by potters in other areas of the piedmont. Although misattributions have stifled research for more than half a century, scholars like Dorothy and Walter Auman (fig. 17) began to assemble information on non-Moravian potters during the 1960s. Descendants of potting families from the Seagrove area, the Aumans knew that the ceramic history of North Carolina was far less monolithic than most scholars assumed. They established the Seagrove Pottery Museum, in which they displayed an earthenware flask inscribed “Thos. Andrews 1784 (fig. 18).” Oral tradition maintains that a Chatham County farmer uncovered the flask in a field and gave it to potter Charles C. Cole, Dorothy Auman’s father. She later discovered that Andrews was a potter who left London at age thirty-five with the intention of settling in North Carolina.[18] The Aumans transferred ownership of many of the objects in their museum to The Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Inspired in part by the Aumans’ love of piedmont ceramics, Professor Charles G. Zug III (fig. 19) was the first scholar to take a transdisciplinary approach in the study of North Carolina pottery. Although primarily focused on stoneware, his Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina has a chapter on earthenware that remains essential reading for anyone interested in that subject.[19] Most important, Zug’s book shows that family and community were vital to the rural pottery trade, and accounts for the flourishing state of North Carolina’s ceramic tradition today.

Scholarly interest in the products of North Carolina’s piedmont potters will persist well into the twenty-first century. It is hoped that archaeological research will continue on the known production sites, that previously undocumented potteries will come to light, and that new, informative examples will continue turning up in private collections and estate sales. Just recently, a Moravian turtle bottle sold by a North Carolina auction house attracted national attention in the antique trade press.[20] It is further hoped that the publication of the 2009 and 2010 volumes of Ceramics in America as well as the interest generated from the accompanying exhibition Art in Clay: Masterworks of North Carolina Earthenware will lead to the discovery of previously unrecognized examples in public and private collections.

J. F. Blacker, The ABC of Collecting Old English Pottery, 4th ed. (London: Stanley Paul and Co., 1900).

Edwin Atlee Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art (1893; reprint with new introduction and bibliography, Watkins Glen, N.Y.: Century House Americana, 1971).

John Spargo, Early American Pottery and China (Garden City, N.Y.: Garden City Publishing, 1926), p. 121.

Ibid., p. 123.

Undated photocopy, private collection, Winston-Salem, N.C. The authors thank Nathan Sapp for this information.

Adelaide L. Fries, “The Wachovia Historical Society,” in Literary and Historical Activities in North Carolina, 1900–1905, edited by William Joseph Peale (Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1907), p. 169. According to Fries, the Wachovia Historical Society received the collection of the Young Men’s Missionary Society, which began acquiring “curios from the mission fields, mineral specimens and stuffed birds, old coins, and local curiosities” before 1850.

Joe Kindig Jr., “A Note on Early North Carolina Pottery,” The Magazine Antiques 27, no. 1 (January 1935): 14–15. This article was reprinted with annotations in The Art of the Potter, edited by Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977), pp. 26–27.

Ibid.

Ibid. Kindig had not heard the term sugar jar applied to comparable Pennsylvania forms.

Ibid.

Luke Beckerdite, “The Life and Legacy of Frank L. Horton: A Personal Recollection,” American Furniture, edited by Beckerdite (East Hampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2006), pp. 9–12.

Some of Horton’s acquisitions came from local dealers or individuals in whose family pottery had descended.

The authors are grateful to Bradford L. Rauschenberg for the information on Willie Jones.

For more on Horton’s contributions, see Beckerdite, “Frank L. Horton,” pp. 2–27.

Stanley South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999).

John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972); Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam: The History of William Ellis of Hanley,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (November 1991): 80–102; Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Carl Eisenberg’s Introduction of Tin-Glazed Ceramics to Salem, North Carolina, and Evidence for Early Tin-Glaze Production Elsewhere in North America,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 31, no. 1 (Summer 2005), pp. 47–52.

Rick Mashburn, “Collecting Moravian Antiques,” Early American Life 19, no. 3 (June 1988): 18–23.

Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), p. 12.

Ibid.

Eleanor Gustafson, “Endnotes: A Turtle’s Tale,” The Magazine Antiques 177, no. 2 (March 2010): 88.