Dish, Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

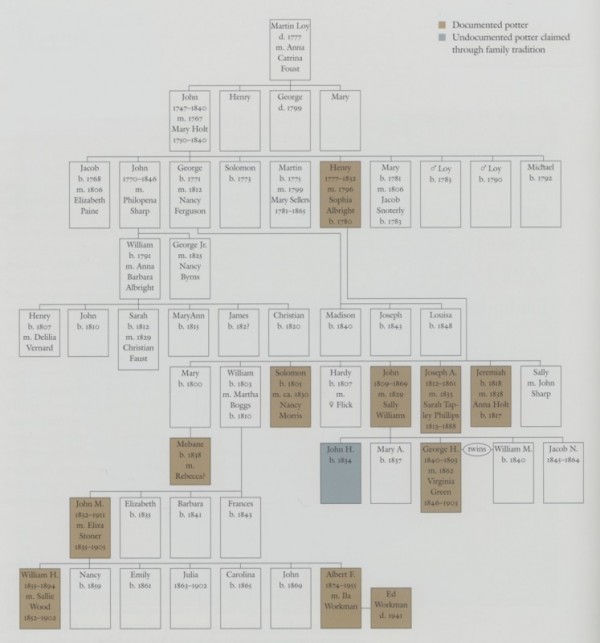

Loy Family of Potters. (Compiled by Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Flask, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1770–1790. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

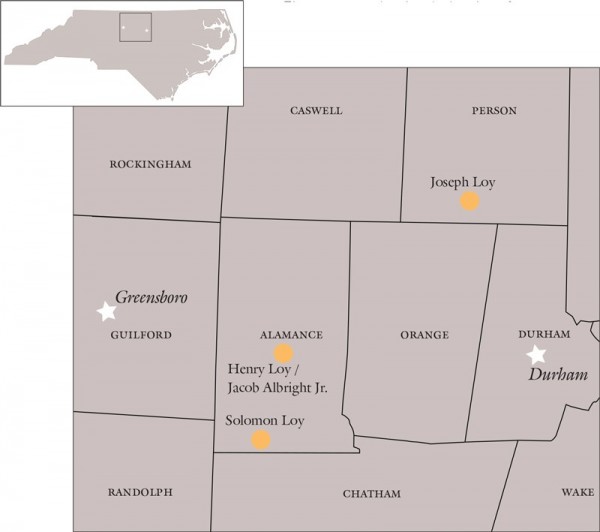

Map showing the location of Loy family potteries.

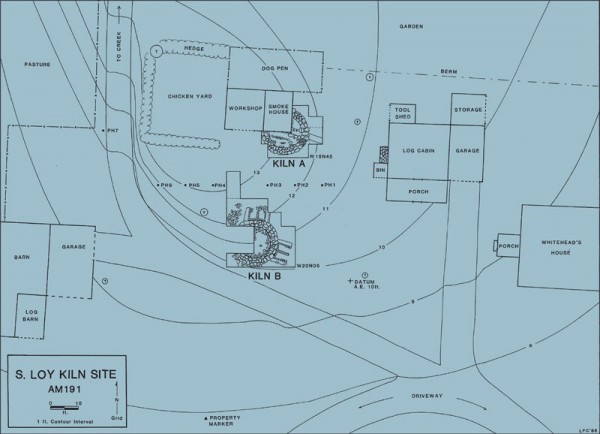

Drawing of site 31AM191 showing the location of two circular kilns, a log house, a barn, and other landscape features following archaeological investigations. (Artwork, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.) The smokehouse covers 25 percent of the foundation of the downdraft kiln (A). The updraft kiln (B) was not entirely excavated because of a fruit tree on top of the west firebox.

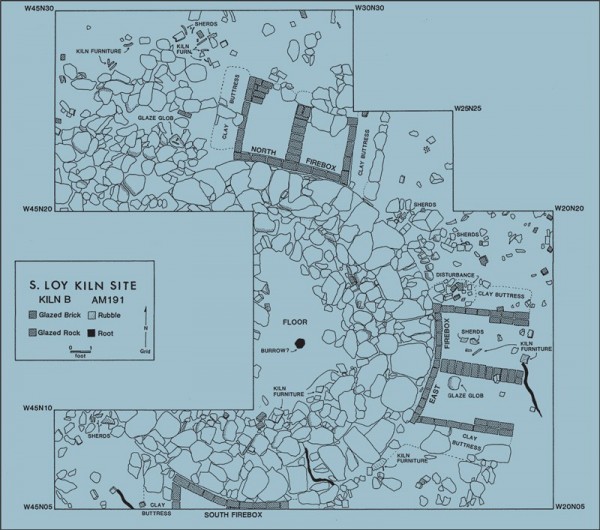

Drawing of the updraft kiln after excavation. (Artwork, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.) Double-chambered, or “hob,” fireboxes are located equidistant along the perimeter of the foundation wall. The interruption in the foundation stone was for a doorway.

View of the updraft kiln during final stages of excavation. (Photo, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.)

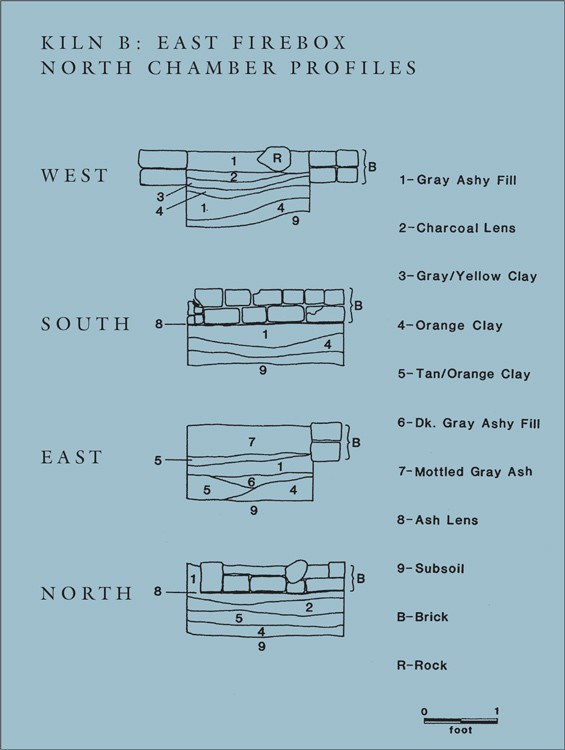

Profile drawings of the east firebox of the updraft kiln (B). (Artwork, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.)

View of the east firebox following excavation. (Photo, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton).

Pipe and kiln furniture recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware and high-fired clay. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) The pipes and supports would have been placed in a sagger. Fragments of thirteen pipe heads were recovered during excavations, six of which were in the updraft kiln. Five fragments were unglazed earthenware, two were lead-glazed, and six were salt-glazed stoneware. The unglazed earthenware examples are fluted, and one has a face at the outer elbow joint. The fluted examples matched a pewter pipe mold found in the chinking of the log house on the site.

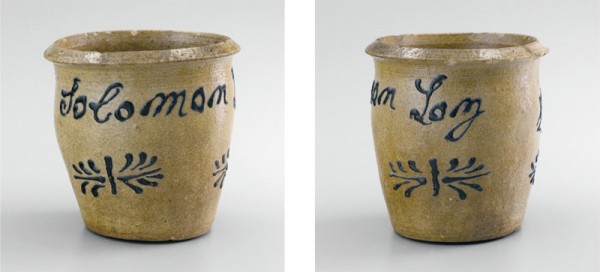

Jar, Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1830–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This jar bears the maker’s full name. Solomon also used stamps and incising to mark his ware. A large cobalt-decorated stoneware crock and a unique salt-glazed stoneware grave marker dated 1834 have square floral stamps. Fragments of large crocks bearing the mark of Solomon’s son John M. Loy were recovered at Solomon’s site (31AM191). Some had debased cruciform motifs, like those on this example.

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Private collection.) Loy’s dishes are generally lighter and thinner than those made by Moravian potters in Bethabara and Salem, North Carolina. He used green, orange, brown, and black slips to decorate earthenware, and brown and blue slips to decorate stoneware.

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 12. Some late Moravian dishes have concave backs, but they do not flare as dramatically as those associated with Loy.

Fragmentary bowl recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Bowl, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 6 3/16". (Private collection.)

Detail of the back of the bowl illustrated in fig. 15.

Bowl fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Tripartite stylized leaves like those on these fragments are common on slipware attributed to Loy.

Mug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Handle fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) The molding on the fragment at the upper right is similar to that of the handle on the mug illustrated in fig. 19.

Fat lamp, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Container, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection.) The foot of this object is similar to those on the mugs illustrated in figs. 18 and 19.

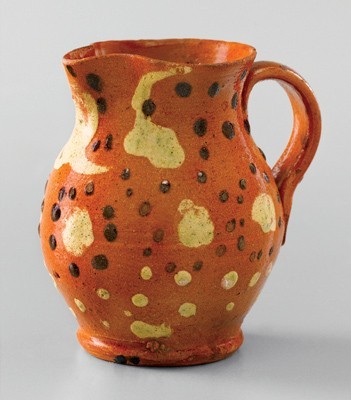

Cream jug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.) The decoration on this cream jug is related to that on dish and hollow-ware fragments recovered at Loy’s site (see fig. 31).

Bowl, dish, and handle fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 15". (Private collection.) This monumental dish is the largest example attributed to Loy.

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/2". (Private collection.)

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) The trailing on the fragment on the left is similar to that in the center of the dish illustrated in fig. 48, whereas the leaf motif on the right fragment relates to that in the cavetto of the example shown in fig. 44.

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Nested triangles occur on several paint-decorated chests from Berks County, Pennsylvania. As was the case with Martin Loy, many early Alamance County settlers had previously lived in Berks County.

Hollow-ware fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Bowl fragment recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Detail of the decoration on the marly of the dish illustrated in fig. 33.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the decoration on the marly of the dish illustrated in fig. 35.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 1/2". (Private collection.) This dish and the example illustrated in fig. 38 may be by Solomon Loy. If so, they probably date from the beginning of his career but no earlier than ca. 1825.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Bowl and saucer, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 7/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 5/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.) The back of this dish has post-firing marks similar to those on the examples illustrated in figs. 40 and 41.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 3/4". (Private collection.) This dish and the examples illustrated in figs. 44, 47, and 48 may be by Solomon Loy. If so, they date no earlier than 1825.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The plant motif in the center is a debased version of that found on dishes and hollow-ware forms decorated by earlier potters in the St. Asaph’s tradition.

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 44.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 48.

Slipware fragments recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Handle fragments recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Joseph used copper oxide to produce a green glaze. His son George Haywood produced similar wares well into the 1860s.

Marble and candlestick fragment recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Handle fragment recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Slipware fragments recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Pipe prop and anthropomorphic object recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1825. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Mug fragments recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Some of the mug bases from Albright’s site are similar to those associated with Solomon Loy.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery produced slipware with marbleizing like that in the lozenges on the marly of this dish.

Solomon Loy (1805–before 1865) emerged as a master potter during the second quarter of the nineteenth century—a period of technological and stylistic transition in North Carolina’s ceramic industry. Although trained as an earthenware potter in a tradition distinguished by the use of polychrome slip decoration, Loy responded to demand for more durable forms with nonreactive coatings by making salt-glazed stoneware. Many of his salt-glazed vessels have trailed slip designs that relate to those on his earthenware as well as on pottery associated with earlier members of his extended family. To say Loy was born into a “clay clan” may be something of an understatement, as his father, father-in-law, uncles, brothers, and possibly his great-grandfather were potters. He also trained his son, nephew, grandsons, and neighbors, thus contributing to the longevity of what has been termed the “St. Asaph’s tradition” (see in this volume “Slipware from the St. Asaph’s Tradition” by Luke Beckerdite, Johanna Brown, and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton).[1]

Several stoneware vessels documented to Loy survive, but an earthenware dish decorated with triangles on the marly is the only object in that medium bearing his full name (fig. 1). Documentary research and archaeology conducted after the publication of this dish in Charles Zug III’s Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (1986) have broadened our understanding of Loy’s career and work.[2] This essay will present these new findings by examining the historical context of pottery making in the St. Asaph’s district of Orange County (now southern Alamance County), analyzing kiln remains and earthenware fragments recovered at Loy’s site, and using archaeological evidence to identify surviving examples of his work.

The Loy Family

When Solomon Loy began his career, pottery making in North Carolina was a cottage industry; production was often seasonal, makers sold directly to consumers, and bartered goods and services were common forms of payment. Craftsmen and their kin often intermarried with other potting families in order to protect trade secrets, maintain a labor force, and gain access to markets or natural resources.[3] The Loy family tree (fig. 2) illustrates how members of Solomon’s family followed that pattern, although many connections have yet to be explored. Over the course of six generations, at least a dozen Loys worked as potters. Some married into the families of potters, like the Boggs and the Phillips; others married into the families of prominent landowners, like the Holts and the Albrights. As was the case with Solomon Loy’s great-grandfather Martin, the progenitors of several of these families had settled in Alamance County during the 1750s and 1760s and clustered in communities according to ethnicity (German and English) and religious affiliation (German Reformed/Lutheran and Quaker).

According to family tradition, the Loys were Huguenots who sought refuge in southwestern Germany following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Martin may have been born at Herzenhausen, Hessen, where his father, Johannes, worked as a tailor.[4] In 1729 Martin married Anna Margaretha Fechter in the German Reformed Church in Mussbach, and the couple eventually had three children.[5] What became of their progeny remains unclear, but port-of-entry records indicate that Martin and Anna Margaretha arrived in Philadelphia aboard the ship St. Mark on September 26, 1741.[6] Approximately two years later, Martin married Anna Catrina (also referred to as Catherenny) Foust, members of whose family had emigrated from Germany in 1733, settling first in Berks County, Pennsylvania, and later in southern Alamance County, North Carolina. Martin and Anna Catrina had four children: John, George, Henry, and Mary.[7]

Martin Loy and his family apparently moved to Augusta County, Virginia, before February 17, 1753, when his name appears on a bond with John and Ernest Sharp.[8] The relationship between these two families extended to Alamance County, where Martin’s grandson John married Philopena Sharp, daughter of Isaac Sharp III.[9] Isaac was John and Ernest Sharp’s brother.[10]

The Loy family apparently arrived in North Carolina before 1765, when Martin purchased 251 acres of land on Great Alamance Creek.[11] In 1769 he settled on a 112-acre tract farther south on Varnal’s Creek, and later became a member of Stoner’s Church, a German Reform congregation.[12] Martin died in 1777, and his will, probated two years later, lists his son George and his friend Jacob Albright Sr. as executors and Isaac Sharp III as witness.[13] Census records indicate that Anna Catrina remained on Martin’s land until at least 1800 and that their sons John, George, and Henry were heads of households in the St. Asaph’s district.

Although there is no documentary evidence that Martin Loy was a potter, circumstances suggest he was: he came from an area in Germany known for the production of slip-trailed and sgraffito-decorated earthenware; he settled in Berks County, Pennsylvania, where immigrant potters made comparable objects; and he was the progenitor of what became a clay clan. Even more significant, one of the earliest examples of slipware from the St. Asaph’s district is a flask decorated with a cross with radiating fleur-de-lis, a motif found in French Protestant and Catholic iconography (fig. 3). Given the Loy family’s Huguenot origins, Martin must be considered a possible source for this design.

Martin Loy’s son John married Mary Holt in 1767.[14] Between 1768 and 1792 the couple had ten children. Their son Henry (1777–1832) was a potter who married Sophia Albright on September 6, 1796.[15] She was the daughter of Jacob Albright Jr. and Sally Wolf, who also came from a potting family. Jacob was listed as a potter in the 1800 tax list for the St. Asaph’s district. “An Inventory and an Account of Sales of the Estate of Jacob Albright Decd,” dated March 24, 1825, listed two potter’s wheels, a glaze mill, a clay mill, a grindstone, a pipe mold, and a stove mold along with stock-in-trade.[16] The lack of household goods indicates that the contents of Albright’s pottery were inventoried separately from his personal effects.[17]

Henry and Sophia had eight children: Mary (b. 1800); William (b. 1803); Solomon (b. 1805); Hardy (b. 1807); John (1809–1869); Joseph A. (1812–1861); Jeremiah (b. 1818); and Sally (birth date unknown). Solomon was apparently named after his uncle on his father’s side. William was the only son who was not a potter, but he owned the land on which Solomon built his last two kilns and worked.[18] It is possible that this entire generation of Loy potters served apprenticeships with their father in the Henry Loy/Jacob Albright Jr. shop. William, Solomon, John, and Jeremiah remained in southern Alamance County, but Joseph moved to Person County after marrying Sarah Tapley Phillips in 1833.[19] Her father, John, was also a potter.[20]

About 1830 Solomon Loy married Nancy Morris (b. 1803), whose father was Henry Morris. The Morris and Loy families must have been close, since Solomon’s father was the executor of Henry Morris’s estate.[21] Solomon and Nancy had four children: John Mebane (1832–1911); Elizabeth (b. 1835); Barbara (b. 1841); and Frances (b. 1843). Census records indicate that Solomon died before 1865, but where he and Nancy are buried is not known.[22]

The next generation of Loy potters extended the family’s craft tradition into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. John Mebane Loy continued to produce stoneware at his father Solomon’s site; William’s son Mebane trained with Solomon and later set up his own shop nearby; and Joseph’s son George Haywood made stoneware and earthenware in Person County.[23] Oral tradition maintains that Joseph’s son John H. was also a potter, but neither his site nor any ware made by him has been identified. Another potter who can be considered part of this ceramic tradition is John Thomas Boggs, who came from a local potting family and served his apprenticeship with Solomon Loy.[24]

Early Site Discoveries

A 1986 archaeological survey of Alamance County, North Carolina, identified two pottery sites with kiln remains, 31AM191 and 31AM192.[25] Although both were subsequently linked to Solomon Loy, test trenches revealed that site 31AM192 had been compromised from modern landscaping. Recovered artifacts were limited to lead-glazed earthenware and kiln furniture, which suggests that 31AM192 predated 31AM191. The presence of lead-glazed earthenware in combination with salt-glazed stoneware suggests that 31AM191 came later and was occupied for a longer period. In the east-central piedmont region, the shift to stoneware production began in the late 1830s and continued into the early 1920s.

Sites 31AM192 (Solomon Loy’s first kiln) and 31AM191 (his last two kilns) are located in southern Alamance County near Snow Camp, a Quaker community settled in the mid-eighteenth century (fig. 4). During the period covered by Solomon’s career, this community was part of Chatham County (formed in 1770), where Loy is listed on the tax rolls. It was not until 1897 that the northern edge of Chatham County became part of Alamance County. As was the case with many early Quaker settlements, Snow Camp and its sister community, Cane Creek, were located near waterways—essential for the establishment of mills. Germanic immigrants such as the Loys followed a similar pattern, although Lutheran and German Reformed churches, rather than Quaker meetings, served their communities.[26]

The 1986 survey and Zug’s historical research also identified potteries operated by descendants of Solomon: his grandsons Albert Loy (31AM182) and William H. Loy; his brother or nephew John Loy; and his nephew Mebane Loy.[27] Another possible production site (31AM278) was recently discovered near Varnal’s Creek in the St. Asaph’s district, where Solomon’s family originally settled. Fragments surface-collected there include lead-glazed earthenware with slip-trailed decoration, kiln furniture, English creamware, and wine-bottle glass. The locally made and imported artifacts suggest that the site may have been occupied from about 1780 to about 1820. Deeds indicate that the owner of the pottery was Jacob Albright Jr. He is described as a “potter” in the 1800 tax list for the St. Asaph’s district, but it is unclear whether he worked in that trade or provided land and financing for his son-in-law, Henry Loy, which was not an uncommon practice at that time.[28]

The Solomon Loy Site

Site 31AM191 (fig. 5) is located in the middle of a farm. Several nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings surround and partially cover the site, and human feet continue to traverse the yard where the detritus of previous activities is buried. Paved roads, utility lines, and a new brick house mask what was once a thriving pottery. Mature black walnut trees, an aging log barn, and a small log house are all that remain from two centuries past.

In 1980 Carl Lounsbury examined the farm complex as part of a countywide architectural survey. He referred to the log dwelling as the “Teague/Loy” house and postulated a date of 1880s, but the design of the stone and brick chimney suggests that the building could be earlier.[29] Some of the bricks had significant deposits of salt glaze on their surfaces and may have been recycled from an abandoned or reconstructed kiln.[30] The owner of the farm also reported that he found a pewter pipe mold in the chinking of the log house, and it appears to have been used to make some of the clay pipes recovered at the site. Deed research indicates that Solomon Loy’s older brother William owned the land on which the pottery was located.[31] William’s involvement in the business has not been fully explored, but family history maintains that he was not a potter.

Archaeology at the site began in 1986 with the excavation of a test unit near a standing smokehouse. The property owner had attempted to sink a fence post in that location and encountered an unknown buried feature. Recovered artifacts included earthenware and stoneware fragments, kiln furniture, and glaze debris along with large rock slabs located six inches below the surface. Expansion of the unit subsequently revealed two small postholes that had punched through the arched top of a tunnel-like structure located beneath the foundation stones. Because this feature appeared to be part of a semisubterranean groundhog kiln, work ceased until arrangements for additional time, help, and equipment could be made. Excavations resumed two years later, revealing the remains of two circular kiln foundations, each measuring seventeen feet in diameter; thousands of bisque-fired earthenware, lead-glazed earthenware, and salt-glazed stoneware fragments; tobacco pipe heads; several types of kiln furniture (props, saggers, wads, and coils); globs of glaze residue; and architectural debris from the furnaces.

One kiln was a downdraft type, complete with an underground transept flue (formerly thought to be the tunnel of a groundhog kiln) made of brick, but missing its exhaust chimney (likely dismantled and recycled into the chimney of the log house). The foundation walls, two-and-one-half feet thick, were made of local fieldstone and held together with clay mortar. The interior ware floor, which measured twelve feet in diameter, was covered with broken props and coils coated with crushed white quartz to prevent them from sticking to the pottery during firing. This kiln was used for the production of stoneware by Solomon Loy and later by his son John.[32]

Located about twenty feet downhill, the second kiln was an updraft design with four double-chambered fireboxes, situated equally distant, around the perimeter of the foundation (figs. 6, 7).[33] The foundation walls were constructed just like those of the downdraft example: two feet thick, made of fieldstone, and mortared with clay. The interior, which encompassed 227 square feet, contained in situ kiln furniture and a floor of fine gravel (crushed quartz) on top of a dense clay layer that had turned deep red from multiple firings. Shelves, tiles, and props coated with lead glaze confirmed the use of this furnace for the manufacture of earthenware.[34]

All of the excavated fireboxes were six feet long, four feet wide, and made of handmade brick laid in clay mortar (figs. 8, 9). The exterior walls were double coursed for additional support and buttressed with piles of whitish gray clay. The builder added an additional course of brick at the loading ends, which constricted the opening and thereby improved draft. A single course of brick served as the divider, or “hob,” separating each firebox into smaller chambers measuring 1.8 feet in width and 3.5–4 feet from end to end. The fill in the east and north fireboxes consisted of alternating layers of ash, charcoal, and gray clay—evidence of repeated firings and cleanings. The back walls of the fireboxes, curved to abut the kiln’s stone foundation, were mortared with clay.[35] Their design is similar to what kiln authority Daniel Rhodes describes as a “hob firebox.”[36] Wood would have been arranged crosswise on the center support, allowing the bottom pieces to burn first, then drop down and ignite the timber stored in the lower chambers. Because it was relatively self-sustaining, a hob firebox could be left unattended until the wood supply was burned out.

It is not known whether Loy’s updraft kiln was a beehive, dome, or bottle design, but the quantity of unglazed earthenware fragments and kiln furniture found on the interior floor suggests that the furnace may have had two stories, an upper chamber for bisque firing and a lower chamber for glaze firing. If that were the case, the kiln would have been more than thirty feet in height. Bricks were likely used to construct the upper portion of the kiln to provide better control for expansion and contraction during firing and cooling periods. Stones, while excellent for foundations, lack this elasticity.[37]

Loy was clearly as skilled in kiln design and construction as he was at turning and decorating pottery, and his two kilns were twice the size of that built by Philip Jacob Meyer at Mount Shepherd in nearby Randolph County.[38] The architecture of his kilns as well as the range of earthenware and stoneware fragments found nearby make Loy’s site one of the most significant of its type in the state.

The Earthenware of Solomon Loy

The terms that backcountry potters like Solomon Loy used to describe their work and manufacturing processes remain something of a mystery. Daybooks, account books, and other documents pertaining to the day-to-day operation of their businesses are scarce, and formulas for clay mixtures and glazes were well-guarded secrets, most often transmitted through verbal communication and demonstration. Even when pottery-related terms are found in estate records or business accounts, interpretation and application often varied between maker, seller, and consumer and from one generation to the next. Nomenclature for vessel forms used in this article complies with a large body of research gathered over several decades and is consistent with that found in the companion volume of Ceramics in America published in 2009.

Excavations at site 31AM191 yielded a total of 16,731 artifacts: pottery fragments, kiln furniture, architectural debris, glaze waste, and other historic and prehistoric objects. Quantifiable attributes used to group ceramics were body composition (earthenware, stoneware, or intermediate ware), surface finish (unglazed, glazed, location of glaze, and Munsell color equivalent for glaze), decoration (type, use, and composition), maker’s marks (stamped, slipped, incised), vessel form (food or non-food related), percent of vessel represented, paste (Munsell color equivalent), portion of vessel represented, condition (burned, overfired, underfired, warped), and count. Food-related vessels produced at the site included crocks, jars, jugs, pitchers, churns, plates, saucers, bowls, mugs, and cups. Non-food ceramic items included flowerpots, tiles, candlesticks, grave markers, and smoking pipes.[39]

Fragments of 1,168 identifiable earthenware vessels were recovered at Loy’s site: 525 jars (including crocks), 313 bowls, 283 dishes (including plates and saucers), 18 pitchers, 17 jugs, and 12 mugs/cups. Loy also made earthenware pipe heads with glazed and unglazed surfaces, as well as fluted and anthropomorphic bowls (fig. 10). His transition to salt-glazed stoneware, which occurred during the mid- to late 1830s and continued into the 1880s, was marked by a dramatic increase in the production of storage containers (fig. 11) and a decline in the manufacture of tableware.[40]

The dish and plate fragments from 31am191 have consistent rim, back, and base profiles. Morphologies cited in John Bivins’s The Moravian Potters in North Carolina are problematic for comparative purposes, because many of the dishes and plates he studied were actually made in southern Alamance County. Indeed, most of the features Bivins assigned to the “second part of the middle period” of Moravian production—squared rim, concave back, lack of a foot—are characteristic of Loy’s work (figs. 12, 13) as well as that of other potters from the St. Asaph’s tradition.[41]

Loy’s bowls are distinguished by having relatively steep sides and rims that are slightly concave at the top and gently rolled at the back (fig. 14). All of the surviving examples display moderate outward flare from bottom to top, but are not coved in rear profile (figs. 15, 16). Loy decorated the rims of bowls with evenly spaced small dots or in more random patterns reminiscent of the so-called dotted Staffordshire slipwares made in the eighteenth century. One bowl (location unknown) has precisely applied dots in the concave section of the rim, a detail found on bowl fragments from Loy’s site (fig. 17).

The mugs illustrated in figures 18 and 19 are attributed to Loy based on their decoration and handle and base profiles, which relate closely to those of fragments recovered at Loy’s site (fig. 20). Both mugs have bodies that taper slightly below the rim, simple molded lips and feet, and handles that are feathered into the body at the top and reinforced with finger impressions at the bottom. The rim and lip moldings were generated with a rib; the detailing on the handle was probably done with a cylindrical tool or smooth stick. There is no evidence that Loy used an extruder to produce handles.

A fat lamp (fig. 21), an unusual cylindrical container (fig. 22), and a small cream jug (fig. 23) represent other surviving forms associated with Loy.[42] Antique dealer Joe Kindig Jr. of York, Pennsylvania, purchased the lamp prior to 1935 and illustrated it in The Magazine Antiques along with several other pieces of North Carolina earthenware.[43] He was at the forefront of southern pottery scholarship and handled many important examples of Loy’s work. The cylindrical container has a more specific provenance, having been purchased at an estate sale at the farm where Loy worked.[44] The pewter pipe mold found in the chinking of the log house on that property has the same history.[45]

Loy’s earthenware can be interpreted as the final chapter of a ceramic tradition introduced by potters who emigrated from southwestern Germany to Berks County, Pennsylvania, then relocated to southeastern Guilford County and southern Alamance County during the 1760s. As suggested in “Slipware from the St. Asaph’s Tradition” in this volume, familial and religious ties between craftsmen and consumers in those areas contributed to the longevity of the St. Asaph’s tradition. Nearly all of the motifs used by Loy have antecedents in Alamance County pottery dating from the last quarter of the eighteenth century if not earlier.

Like his predecessors in the St. Asaph’s tradition, Loy applied his decoration directly on the clay body or on white, orange, and black slip grounds, often referred to as engobes. Few American earthenware potters outside the St. Asaph’s tradition used black grounds. Loy trailed most of his designs (see fig. 12), but several objects attributed to him have dripped decoration (figs. 24-26). Both types of ware were bisque-fired to harden the body and slip, then burned a second time to mature and bond the lead glaze. Proper firing was critical in the production of decorated earthenware because temperature and kiln atmosphere influenced the final color of slips and glazes.

Bisque and glazed fragments recovered at Loy’s site indicate that his decorative vocabulary included lunettes (fig. 27), stylized leaves (fig. 28), imbricated (fig. 29) and “nested” (fig. 30) triangles, jeweled circles (fig. 31), and stylized crosses with dots representing pommettes (fig. 32). Surviving examples of his work also feature interlinked cymas, lobate designs filled with dots, and, in one instance, a fylfot. Loy’s trailing on these archaeological and intact wares is competent (figs. 33, 34), but not as bold as that of earlier potters in the St. Asaph’s tradition (figs. 35, 36).

Dishes are the most ornately decorated objects associated with Loy. Four have combinations of lunettes, imbricated triangles, and stylized leaves on the marly and cruciform motifs in the center (figs. 12, 33, 37, 38). The example illustrated in figure 38 is the most refined, with three colors of slip on a white ground, interconnected cymas encircling the cavetto, and a stylized cross with rays extending from the center. Loy also used a somewhat crude version of this cruciform motif on salt-glazed stoneware (see fig. 11). While Loy’s crosses are less complex than those of earlier potters in the St. Asaph’s tradition, they are among the most persistent motifs in his work (fig. 39).

Several of Loy’s dishes have stylized plants in the cavetto, including a pair marked “E+K” on the back (figs. 40, 41). As is the case with other, similarly marked examples of slipware from the St. Asaph’s tradition (see figs. 35, 42), the letters were cut into the clay after firing. Variations of the cavetto decoration on these dishes occur on other examples from Alamance County, some possibly by Loy and others by related potters of his generation (figs. 42, 43).

Continuities within the St. Asaph’s tradition can make attributions difficult. The dish illustrated in figure 44 has stylized leaves on the marly and triangles encircling the cavetto—motifs that occur on fragments from Loy’s site (figs. 30, 45)—but its coved rear profile is sharper than that on other examples attributed to him (figs. 13, 46). If this dish is by Loy, it most likely dates from the beginning of his career. The same can be said of the example shown in figure 47, which has a cavetto design related to that on an earlier dish by a different hand (see fig. 35). The presence of other potters at Loy’s site could explain some variations in form and decoration among surviving examples. A dish with black and yellow slip applied on an orange ground (figs. 48, 49) has several features that suggest it is from his pottery; the stylized grass motifs on the marly and overlapping lines (straight and wavy) in the center of the cavetto are similar to those on excavated fragments (see figs. 17, 28), and the fine jeweling in large lobes on the marly relates to the precisely applied dots on other objects attributed to Loy. At the same time, this object has a gently rolled rim—a common feature on Loy’s bowls but not on dishes attributed to him. No other Alamance County slipware with jeweled, lobate motifs is known, but the design is often seen on paint-decorated furniture from southeastern Pennsylvania.

Because of the sheer number of artifacts recovered at Solomon Loy’s site, his work is a benchmark for understanding earlier and later pottery in the St. Asaph’s tradition. This is particularly true of artifacts associated with sites occupied by his father, Henry, and brother Joseph. Collectively, these objects show that the decorative vocabulary of Alamance County potters was codified by the end of the eighteenth century if not earlier.

The Joseph Loy Site

Joseph probably learned the pottery-making trade from his father and older brothers, then went into business with his father-in-law when he relocated to Person County, North Carolina. Joseph’s site (31PR59) was discovered in 1992, owing to the diligent efforts of his descendants Allen and Hugh Campbell.[46] With the help of volunteers, fifteen small test units were excavated in a single day that yielded hundreds of artifacts—mostly lead-glazed earthenware fragments and kiln furniture, as well as datable European ceramics and glass. A partial kiln wall made of local fieldstone was found just below plow zone; the kiln was likely an updraft furnace used to burn earthenware.

There is no evidence that Joseph Loy made stoneware at this site, but later his sons John Henry and George Haywood each had salt-glaze kilns located elsewhere.[47] A few pieces of lead-glazed earthenware marked with George Haywood’s name survive in private collections. Letters from him to his uncle John A. Loy provide a glimpse at pottery making during this era. He wrote that he had returned to “pottering” because severe rains had destroyed his crops and he needed to make money. He asked his uncle for information about “glazing with copper and how to mix it” and requested that the formula be sent quickly so he could “glaze some greenware in the kiln that is nearly ready to burn.”[48] This indicates George Haywood was producing lead-glazed earthen forms into the 1860s and that formulas for glazes were passed between family members.

Excavations at Joseph Loy’s site revealed several interesting pieces of slip-decorated earthenware, among them fragments with green glazes and those representing dishes, plates, large pitchers, cups, and baluster candlesticks (figs. 50-52). Hand-formed clay marbles, glazed and unglazed pieces of kiln furniture, and a few fragments of pottery with dark grounds and polychrome slip decoration in floral and geometric patterns rounded out the assemblage (fig. 53). The trailed fragments are consistent in design and palette with those recovered at other Loy family pottery sites.

The Henry Loy/Jacob Albright Jr. Site

The Henry Loy/Jacob Albright Jr. site (31am278) is potentially the most significant archaeological find relating to earthenware production in Alamance County.[49] Surface examinations yielded hundreds of lead-glazed earthenware fragments, many of which have elaborate slip-trailed decoration (fig. 54); a large quantity of kiln furniture (mostly stacking shelves or slabs and props); and an unusual anthropomorphic object, possibly intended for use as a pipe head prop (fig. 55). Solomon Loy made similar props by rolling out pieces of clay, attaching them to a base, and firing the assembled piece (see fig. 10). Relationships between decorated fragments from the Henry Loy/Jacob Albright Jr. and Loy family sites suggest that the Loy/Albright shop was the principal training ground for early-nineteenth-century artisans in the St. Asaph’s tradition. This pottery shop clearly produced earthenware with polychrome slip on dark grounds and vessel forms that relate to those represented by fragments from the Solomon and Joseph Loy sites (fig. 56). Fragments from the Loy/Albright site also relate very closely to such contemporaneous pottery as the dish illustrated in figure 57.

A Legacy in Clay

Folklorist Henry Glassie could have been describing members of the Loy family when he wrote, “the potter manages the transformation of nature, building culture while fulfilling the self, serving society, and patching the world together with pieces of clay that connect the past with the present, the useful with the beautiful, the material with the spiritual.”[50] The Loys were more than skillful potters and thoughtful teachers of their craft—they were vital participants in communities linked by language, religion, marriage, migration, and settlement. The documentary record reveals a great deal about the lives and careers of the Loy potters, but as much is gleaned from the surviving wares and archaeological investigations. All of these artisans, whose history was largely written in clay, deserve to be acknowledged as premier potters. The craft and legacy of Solomon Loy, however, earn him special rank as master potter of the Carolina piedmont.

For more on Loy, see Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity: Earthenware and Stoneware Pottery Production in Nineteenth-Century North Carolina” (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1997).

Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), p. 235.

Ibid., pp. 238–43.

Marriages, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche, Mussbach, film 488536; Hasslock Baptisms, film 1418010.

Ibid.

The website www.progenealogists.com/palproject/pa/1741smark.htm lists both Martin and Anna Margaretha as passengers.

Howard M. Faust, Faust-Foust Family in Germany & America, rev. and expanded ed. (Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, 1984), D1–D5. Most genealogies of the Faust family do not include Anna Catrina Foust, who was twenty-one when she arrived on the ship Elizabeth; see www.olivetreegenealogy.com/ships/pal_eliz1733.shtml, where she is listed as Anna Catrina Foust. Anna Catrina may have been the daughter of Johan Peter Foust and his first wife, Magdalena Adams, who died in 1713, shortly after giving birth to their son Peter.

The following year Loy purchased 230 acres of land on Tom’s Creek, adjacent to property owned by George Sharp; Lyman Chalkley, Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish in Virginia, Extracted from the Original Court Records of Augusta County, 1745–1800, 3 vols. (1912; repr., Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1965), 3:73, 321. All three volumes are available online at www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~chalkley/ (accessed June 1, 2009).

Isaac Sharp III and his wife, Philopena Graves, moved from Pennsylvania to Botetourt County, Virginia, before relocating to Alamance County, North Carolina. See http://genforum.genealogy.com/sharp/messages/5893.html (accessed July 30, 2010). The only other evidence of a kiln with a “hob”-style firebox like that used by Solomon Loy was excavated in Botetourt County. Kurt Russ, “The Fincastle Pottery (44BO304): Salvage Excavations at a Nineteenth-Century Earthenware Kiln Located in Botetourt County, Virginia,” Technical Report Series No. 3 (Richmond, Va.: Department of Historic Resources, 1990), pp. 11–23.

http://genforum.genealogy.com/sharp/messages/5893.html (accessed July 30, 2010).

A December 1755 date is cited, without a source, at www.voiceuniverse.com/family/ genealogy/ (search last name LOY, first name MARTIN, select person ID I903; accessed June 5, 2009). This date might not be correct, since Register of Orange County North Carolina Deeds, 1752–1768 and 1793, transcribed by Eve B. Weeks (Danville, Ga.: Heritage Papers, 1984), n.p., refers to Martin’s purchase of 251 acres of land in Orange (now Alamance) County from Henry McCulloh in 1765.

For the 1803 membership roll of Stoner’s Church, see www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ncalaman/stoners.html (accessed March 17, 2010).

Orange County, NC Wills, transcribed by Laura Willis, 13 vols. (Melber, Ky.: Simmons Historical Publications, 1997–), 2:13–14.

John and Mary named their children Jacob, John, George, Solomon, Martin, Henry, Mary, and Michael. The names of two further male children are unknown. David Isaac Offman, “Albright Family Records,” Alamance County Historical Association, 1975.

Brent Holcomb, Marriages of Orange County, North Carolina, 1779–1868 (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1983), p. 186.

The contents of Albright’s pottery were listed in “An Inventory and an Account of Sales of the Estate of Jacob Albright Decd.,” North Carolina State Archives (hereafter cited NCSA), Raleigh, and sold on March 24, 1825. His stock-in-trade included 255 crocks, 62 basins, 20 dishes, 9 pitchers, 7 jugs, 2 cream pots, 2 pans, 2 “P pots,” and 1 sugar pot.

According to deed research, the site AM278 is currently located on a 30-acre parcel that has been in this family’s possession since the mid-1890s. Prior to that it was owned by Cobles, Boyds, Holts, Isleys, and Browns back into the earlier recorded deed of 1803, originally all Orange County. Then the deeds are less specific and include larger tracts of land. One such large tract is listed as Joseph Albright to Andrew Albright (August 13, 1815, for 110 acres) and prior to this deed was Jacob Albright to his son Joseph, dated May 13, 1778, for 150 acres, indicating that the portion of the land where the Henry Loy/Jacob Albright kiln site is located was once on a larger tract of land. Other adjoining tracts of the 1770s were owned by Adam Marly, John Haney, Martin Hurdle (who moved to Person County), and Joel Moody.

Jeremiah, John, and Solomon are listed as potters in Chatham County in the 1850 and 1860 censuses. Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 46–52. William may have received this land from his father (Register of Orange County, North Carolina, Deed Book 25, p. 18, NCSA). Jeremiah’s site has not been located, and it is possible that he worked with one of his brothers. He married into the Holt family, as had his grandfather, thus securing some property, which Joseph most likely farmed. William Loy, the eldest son of Henry and Sophia, married Martha Boggs, who was also from a pottery family in Snow Camp. The Boggs kiln site (31AM199) is approximately one mile from that of Solomon Loy. Historical records indicate that the shop and groundhog kiln were built by John Thomas Boggs and later operated by his son, Timothy. See “The Potters of Alamance County,” in Jane Madeline McManus, Ann Marie Long, and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton, Alamance County Archaeological Survey Project, Alamance County, North Carolina (Chapel Hill: Research Laboratories of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, 1986), pp. 115–22 (appendix A); and Zug, Turners and Burners, pp. 58, 354, 437. Timothy Boggs’ future brother-in-law Joseph Vincent also worked at the pottery. When Timothy died of tuberculosis, Joseph ran the shop until 1910 with help from his sons, Cesco and Turner. John Thomas Boggs trained with Solomon Loy. Pottery associated with members of the Boggs family is documented in South Carolina. For related history in Tennessee, see Samuel D. Smith and Stephen T. Rogers, A Survey of Historic Pottery Making in Tennessee, Research Series No. 3 (Nashville: Division of Archaeology, Tennessee Department of Conservation), p. 16; in Georgia, John A. Burrison, Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983), pp. 310–11; and in Alabama, Joey Brackner, Alabama Folk Pottery (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), pp. 218–19. William Loy’s son, Mebane (born 1838), trained alongside his cousin John M. and neighbor J. T. Boggs, all under Solomon Loy. Mebane later opened his own shop nearby (site recorded but not tested).

Will of John Phillips, Person County, Records, Wills, Inventories, Sales of Estates, Taxables, 1835–1837, pp. 153–54, cr078.801.13, NCSA.

John Phillips is listed as a potter in the 1820 Census of Commerce and Manufacturers for North Carolina.

M. D. Chiarito, “Summary of Alamance County, North Carolina 1850 Census,” unpublished, NCSA, n.d., pp. 194–95.

Solomon’s wife and son John M. are buried at Flint Ridge Cemetery nearby, and other Loys are buried at Mt. Herman Methodist Church farther north. Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” p. 102.

Indirect evidence for John Mebane Loy working at Solomon Loy’s site is suggested by fragments recovered at 31am191 including those marked “SGSW” and “ME.” The letters ME appear to be the beginning of a name. Alamance County census records for 1860 and 1880 list John Mebane Loy as a potter. George Haywood Loy is listed as a potter in Hurdles Mills, Person County, in the 1860 census. Information about Solomon’s grandsons Albert F. Loy and William H. Loy is largely based on family tradition, their surviving wares, and their pottery sites. Albert’s sites were recorded in 1986 (McManus, Long, and Carnes-McNaughton, “Potters of Alamance County,” pp. 114–48 [appendix A]). Discussion of marked John M. and J. M. Loy pieces excavated at site 31am191, as well as census records and family history, indicate John Mebane Loy remained at this pottery shop after his father died. The presence of George Haywood Loy working in Person County is also based on census records and family history. For further description, see Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity.”

No records of formal apprenticeship of the Boggs potters working at Solomon Loy’s shop exist, however; this assessment is based on oral tradition, the nearby proximity of the Boggs land and shop, the intermarriage of the two families, and the fact that John Mebane Loy and John Thomas Boggs were contemporaries. Calvin Hinshaw, noted regional historian, also stated that the Boggses worked at the Loy shop until they built their own kiln, which Timothy Boggs operated until his death. Timothy Boggs married into another pottery family, the Vincents.

McManus, Long, and Carnes-McNaughton, “Potters of Alamance County,” appendix A.

Zug, Turners and Burners, p. 30. The annexed portion of Alamance County (i.e., Newlin and Patterson townships) consisted of a 2 3/4-mile-wide strip, which maintained its strong Quaker character as well as a “distinctive, self-contained tradition” of pottery manufacturing.

For more on the ownership of these sites, see Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 51–54.

“A List of Taxables & Taxable Property within Orange Co. for the Year 1800,” NCSA. The contents of Albright’s pottery were sold on March 24, 1825 and listed in “An Inventory and an Account of Sales of the Estate of Jacob Albright Decd.” Henry Loy died in 1832. Among the items listed in the inventory of his property were “1 pair pipe molds” valued at 12¢, “1 turning wheel” valued at 10 1/2¢, and “1 mill” valued at 5¢. The pipe molds were purchased by Henry’s son John (“Sale of Property of Henry Loy, Decd.,” March 24, 1832, loose estate papers in the Henry Loy file, NCSA). The absence of pottery in the inventory suggests that Henry had either ceased production or transferred his stock-in-trade to another party, possibly one or more of his sons. Land transactions recorded between 1826 and 1839 involving Henry’s sons William and Solomon show they were purchasing land and perhaps were relocating the pottery in the years prior to their father’s death. Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 49–54.

Carl Lounsbury, Alamance County Architectural Heritage (Burlington, N.C.: Alamance County Historic Properties Commission, 1980), p. 130.

Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” p. 48.

Ibid., pp. 49, 86.

Ibid., pp. 114–16. For more details on the design of the kiln used for firing stoneware, see ibid., pp. 65–68, 115–17, and 225–26.

Interiors of the north and east fireboxes were excavated. The south and west fireboxes were left intact in order to preserve a peach tree and provide undisturbed strata for future research.

An interruption in the circular foundation wall was interpreted as a possible threshold for a doorway into the kiln. Bricks on the interior were coated with a thick deposit of glaze.

Only the lower two courses of brick remained intact in the east firebox; the north firebox, located slightly farther uphill, was deeper (1.3 feet), with more of its original brick courses in place. Excavation of the west firebox was avoided.

On the use and design of hob fireboxes, see Daniel Rhodes, Kilns: Design, Construction, and Operation (Radnor, Pa.: Chilton Book Company, 1968), pp. 60–61.

If Loy’s kiln was a beehive design, it may have been only about 8–10 feet high. The Virginia kiln with a hob firebox was recorded during a salvage archaeology project in Botetourt County, Virginia. Roadway construction had destroyed the kiln foundation, but the remains of one double-chambered firebox were found in the embankment adjacent to the road. Russ, “Fincastle Pottery (44BO304),” pp. 11–23.

Alain Outlaw, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery Site, Randolph County, North Carolina,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2009), pp. 165–67.

Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 160–64. Architectural by-products included bricks, foundation stones, mortar samples, gravel floor samples, and glaze waste. Kiln furniture included coils, slab/shelf pieces, saggers, trivets, props, draw trials, and pipe head holders.

Fragments of crocks and jars (86%), jugs (9%), plates (1%), bowls (1%), and mugs (1%) were examined for diagnostic attributes related to the top, middle, and basal portions, with appropriate descriptors for parts per vessel form: lip of a cup; rim of a crock; cavetto of a plate; base of a jar; spout for a pitcher; shoulder of a jug or jar; neck of a jug; collar of a churn; recessed lip to seat a lid; strap handle; lug handle; footring; finial of lid. Capacity indicators, decorations, maker’s stamp or signature, and embellishments were added to the earthenware vessels in the areas of greatest visibility, typically the exterior of hollow ware or inside flatware.

John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972), p. 283. More useful is the recent study by Hal E. Pugh on the decorative plates found in the Quaker community of New Salem located near Randleman, North Carolina (Pugh, “The Quaker Ceramic Tradition in the North Carolina Piedmont: Documentation and Preliminary Survey of the Dennis Family Pottery,” The Southern Friend, Journal of the North Carolina Friends Historical Society 10, no. 2 [1988]: 12–13).

Luke Beckerdite has attributed the lamp to Loy.

Joe Kindig Jr., “A Note on Early North Carolina Pottery,” The Magazine Antiques 27, no. 1 (January 1935): 14–15. This article was reprinted with annotations in The Art of the Potter, edited by Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977), pp. 26–27. The advertisement is illustrated in Beckerdite and Hunter, “Collectors and Scholars of North Carolina Earthenware,” p. 7, fig. 9, in this volume.

This information was provided by William Ivey.

When I first photographed this vase, ca. 1986, it was owned by someone else who had no provenance data regarding the Loy farm purchase. The pipe mold apparently did come from the Whiteheads log house, however, and was sold to William Ivey. I thank Bill Ivey for sharing the history of the container.

Field notes and map from Allen Campbell and Hugh Campbell on the Joseph Loy Site (31PR59), Office of State Archaeology, State Site Files, Raleigh, North Carolina, 1992. Joseph’s site is in a large, open field near the community of Hurdle Mills. It was located using historical maps and oral tradition, then verified with ground-penetrating radar and archaeological investigation. Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity,” pp. 150–51.

Joseph and his wife, Sarah, had five children: John Henry, Mary A., George Haywood, William M., and Jacob N. The eldest, John Henry, eventually moved back to Alamance County, served in the Civil War, and died after being wounded in 1863. George Haywood received his father’s land and home from his mother in 1866. Correspondence between the author and Barry Loy (citing private family papers), 2006 and 2007.

Correspondence between the author and Barry Loy (citing private family papers of George Haywood Loy), 2006 and 2007.

In 1998 an amateur archaeologist discovered this site and subsequently brought it to my attention. I received permission to record the site and surface-collect artifacts between cultivation cycles in the field. The site is about eight miles north of Snow Camp and within one-half mile of the graveyard for Stoner’s Church, where members of the Loy family worshiped.

Henry Glassie, The Potter’s Art (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), p. 116.