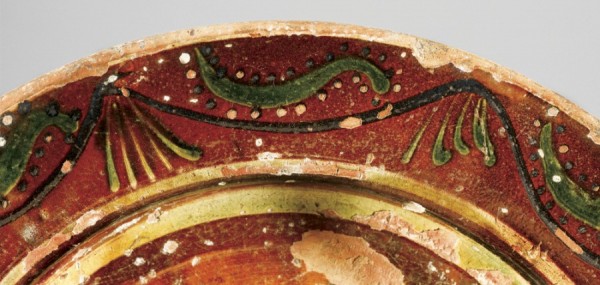

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 3/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.) Antique dealer Joe Kindig Jr. of York, Pennsylvania, purchased this dish prior to April 1935, when he advertised it along with other southern earthenware in The Magazine Antiques 27, no. 4 (April 1935): 121.

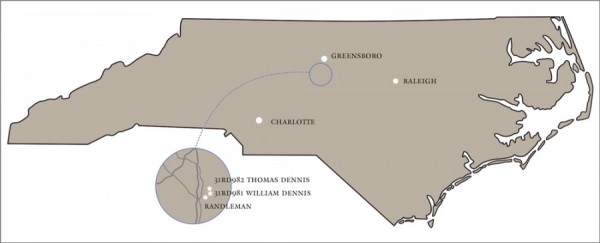

Map showing the location of the William Dennis and Thomas Dennis pottery sites. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

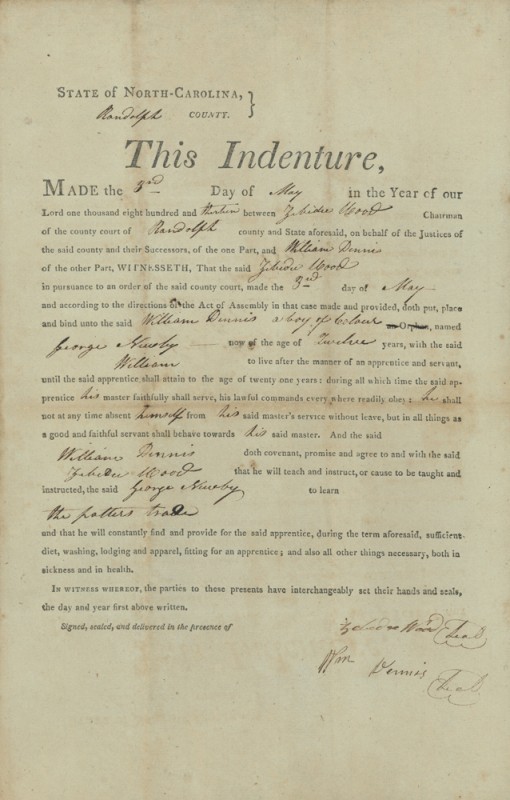

Indenture of George Newby, Randolph County, North Carolina, May 3, 1813. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

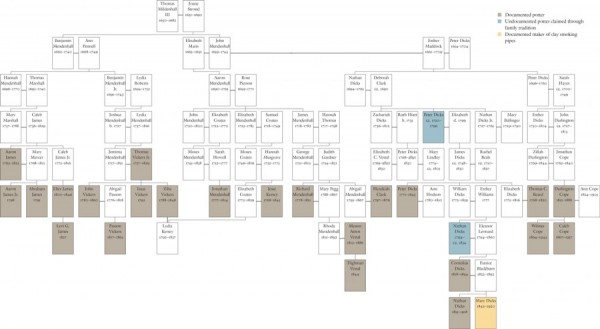

Mendenhall and Dicks family tree. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.) John Mendenhall married Elizabeth Maris (b. 1665) in 1685; in 1708 he married Esther Maddock Dicks, the widow of Peter Dicks.

n Documented potter

n Undocumented potter claimed through family tradition

n Documented maker of clay smoking pipes

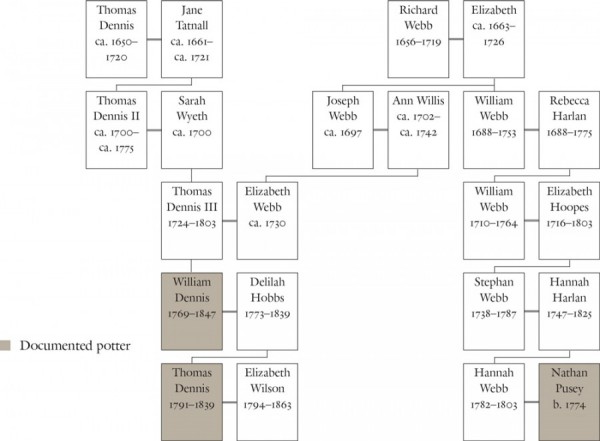

Dennis and Webb family tree. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

View of the William Dennis kiln after partial excavation, Randolph County, North Carolina, 2001. (Photo, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.) The kiln measures 10' by 10' and had 2'-thick rock walls.

Dish rim fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed and bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.) The extrapolated diameters of these dishes are 11 3/4"–12".

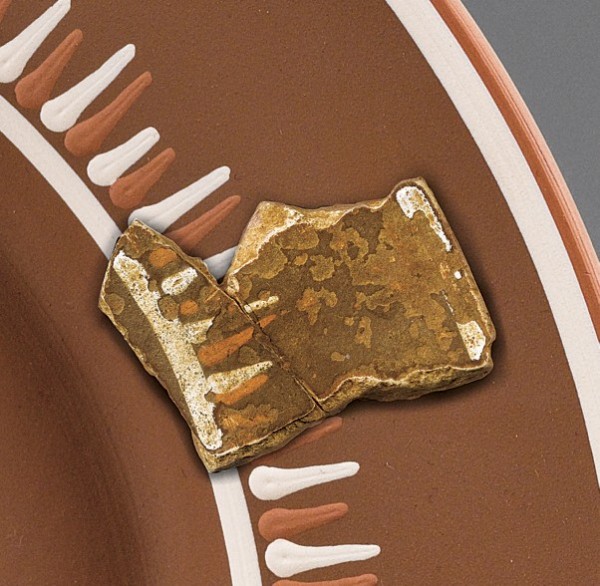

Notched wooden tool with a rim fragment recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. (Private collection.)

Dish rim fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.) The impression left in the clay by the potter’s notched wooden tool is clearly visible on the edges of these rims, particularly the one at the upper left.

Mug fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) The concentric tooling on these mugs appears to have been generated with a multitoothed rib.

Mugs, Staffordshire, England, 1700–1720. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, James Glenn Collection.)

Dish rim fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.) The extrapolated diameters of these dishes are, from top to bottom, 11 3/4", 12", and 13".

Reproduction dish, based on fragments from the William Dennis pottery. D. 12". Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.) The reproduction dish illustrated in fig. 13 was based on these and other related fragments.

Detail of the upper left corner of a sampler by Ann Grimshaw, Ackworth School, Yorkshire, England, 1818. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The decoration in the cavetto of this dish is closely related to that on the fragments illustrated in fig. 14.

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.) All of these fragments have petal-shaped motifs with contrasting slip outlines and jeweling.

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the dish illustrated in fig. 19, with a cavetto fragment recovered at the William Dennis pottery site. The background engobe and slip decoration on the fragment would have matched those on the fired dish. The beige jeweling and concentric banding on the fragment would have burned green during the glaze firing.

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 7/8". (Private collection.)

Detail of the marly of the dish illustrated in fig. 21.

Detail of the underside of the dish illustrated in fig. 19 with a fragment from the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832.

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) The extrapolated diameter of the middle dish fragment on the left is 11 3/4"; the extrapolated diameter of the dish fragment at the lower left is 10 1/2".

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.)

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) The repetitive trailed slip device creates a flame or sunburst pattern.

Reproduction dish, based on fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site. Bisque-fired earthenware. D. 12 1/8". (Private collection.)

Detail of the dish illustrated in fig. 27, with a marly fragment recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. The Dennis potters made engobes ranging from brown to purple-black by grinding iron/manganese nodules with scale produced during the forging of iron.

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/4". (Private collection.) Bearing the initials “AH,” this dish reputedly belonged to Quaker Abraham Hammer.

Kiln tiles recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. High-fired clay. (Private collection.) The tiles on the right are fused together with glaze.

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832 (left) and the Thomas Dennis pottery site (right). Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) The form and profile of these pieces are very similar.

Dish fragment recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) The extrapolated diameter is 11 1/2".

Dish, attributed to the Dennis potteries, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Dish, attributed to the Dennis potteries, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.)

Handle fragment recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) This fragment is the lower terminal.

Handle fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) On the fragments at the upper and lower right, the potter applied the green on a white engobe, which produced a light apple-green color.

Handle fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Front and back views of a handle fragment recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Iron-manganese nodules recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. (Private collection.)

Dish, attributed to the Dennis potteries, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Hollow-ware fragment recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.) The light apple-green color of this fragment was achieved by applying a green lead glaze over a white engobe.

Dish fragment recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.) Marbled in a flattened buff and red slip, the dish from which this fragment came appears to have been drape-molded; it would have been similar in appearance to the example illustrated in fig. 43.

Dish, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Independence Hall, National Park Service.)

Saggar fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. High-fired clay. (Private collection.)

Kiln tile recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. High-fired clay. (Private collection.) This finger-grooved tile is 11 1/2" x 4" and varies in thickness from 1/2" to 1".

Dish, central piedmont region of North Carolina, 1780–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 7/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.) This dish has compositional affinities with the examples illustrated in figs. 1 and 33, but its rear profile differs significantly from those of dishes and fragments associated with the Dennis sites. This compelling object might be part of the larger Quaker slipware tradition that extended beyond the confines of New Salem.

The contribution of Quaker potters to North Carolina’s ceramic history has been sadly neglected owing to the absence of identifiable production sites, insufficient knowledge of those involved in the pottery trade, and scarcity of signed and attributed wares. The belief that Quakers eschewed ornament in their daily life has led to the assumption that their decorative arts were largely unadorned. The discovery of the William Dennis site and the pottery associated with it changes that supposition (fig. 1).

History

In 1766 Thomas Dennis II (ca. 1700–ca. 1775) arrived in what is now northern Randolph County, North Carolina, having moved from his 263-acre farm in East Fallowfield Township in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[1] With the patriarch came his wife, their sons Thomas III (1724–1803) and Edward (b. ca. 1726), and the young men’s families.[2] In their move south, the Dennises followed kin and other members of the Society of Friends who had been migrating from Pennsylvania to the central piedmont region of North Carolina since the 1750s. The families of Thomas II and Thomas III settled on a 300-acre tract of land that sat astride the colonial trading road, an advantageous location for the establishment of pottery making that came later (fig. 2). Like many migrants from Pennsylvania, the Dennises probably followed that route from Petersburg, Virginia, into the North Carolina piedmont.

Upon the death of Thomas Dennis II, in 1775, his property passed by will to his wife, Sarah, and eldest son, Thomas III.[3] Thomas III was a devout Quaker who adhered to his pacifist beliefs during the American Revolution. His land and house were confiscated after he refused to fight and swear the oath of allegiance against the king of Great Britain and his successors, which was required by North Carolina law in 1778.[4] On April 19, 1779, Robert and William Rankin received a land grant for the confiscated property “Containing three hundred Acres laying in the County aforesaid on bouth sides the Trading road and west side of Pole cat adjoining Joseph Hills Entry running for Compliment, Including the Improvement of Thomas Dennis.”[5] Thomas III was forced to buy his property back, receiving a grant in his name in 1786.[6] When he died, in 1803, his property passed by will to his son, William Dennis (1769–1847).[7]

As Quakers, the Dennises believed that the souls of men had an inner light that could illuminate God’s will and guide the conscience. This spiritual connection was a foundation of the sect’s adherence to tenets of equality and nonviolence, beliefs that played a major role in William Dennis’s taking an African American child named George Newby (ca. 1801–ca. 1870) as an apprentice in the pottery trade in 1813.[8] The Disciplines of the Society of Friends recommended that members “in their several neighbourhoods advise and assist such of the black people as are at liberty, in the education of their children, and common worldly concerns.”[9] Newby’s indenture is the earliest documentary evidence of pottery production at the Dennis site (fig. 3).[10] The apprenticeship bound him until the age of twenty-one, which meant he would have completed his term about 1822. It is probable that William also taught his eldest son, Thomas (1791–1839), the pottery trade. According to a late-nineteenth-century history, “[Thomas] . . . followed farming until he was near twenty years of age, when he commenced to learn the potter’s trade, which he followed . . . until his removal to Wayne County, Ind., landing Oct. 1, 1822.”[11] Although this account suggests that Thomas’s apprenticeship commenced in 1811, it is far more likely that he began working with his father as a child, completed his training at the age of twenty, and supplemented his trade with farming like most rural craftsmen. In 1812 Thomas purchased 164 acres of land adjoining his father’s property and established his own pottery.[12] Part of Thomas’s tract had belonged to William Dennis’s aunt Rachel, who was the widow of Edward Dennis. That land contained extensive beds of clay suitable for the manufacture of pottery. Early histories and deeds show that Thomas probably operated a pottery there from 1812 through 1821, when he sold his property to Edward Bowman prior to moving to Indiana.[13]

The technically accomplished wares associated with the William Dennis site suggest that he learned his trade from an experienced and knowledgeable potter. At present one can only hypothesize as to the identity of his master. It is possible that William’s father, Thomas III, was also a potter, but at present farming is the only occupation that can be documented to the elder Dennis. This does not eliminate him from consideration, since both William and his son Thomas combined pottery making with farming. It appears that William’s earlier male lineage was involved in the farming and shoemaking trades. His grandfather Thomas II was listed as a yeoman in his will, which was probated in North Carolina in 1775, and as a cordwainer on a New Jersey deed registered in 1728.[14] William’s great-grandfather Thomas I (who emigrated from an area near Athlone, Ireland, to New Jersey in 1682) was listed as a shoemaker in 1684, while in Gloucester County, New Jersey, and in 1692, in Philadelphia.[15]

Quakers often apprenticed their children to other members of their faith. The Disciplines of the Society of Friends “advised [brethren] to bring up their children to habits of industry, placing them with sober and exemplary members of the society, for instruction in such occupations as are consistent with our religious principles and testimonies.”[16] At the age of fifteen, Richard Mendenhall (1778–1851) of southern Guilford County, North Carolina, was sent to Chester County, Pennsylvania, to serve an apprenticeship with his second cousin’s husband, potter Jesse Kersey (fig. 4).[17] It is possible that William Dennis learned the potter’s trade in a similar way. His second cousin once removed, Hannah Webb, was married to Nathan Pusey, a potter in Chester County.[18] This relationship was through his mother’s side of the family, and her maiden name was Elizabeth Webb (fig. 5); however, no connection has yet been documented between Pusey and Dennis.

It is equally plausible that William learned his trade locally. Members of the Hoggatt (Hockett) and Dicks families, who lived five miles north of the Dennises, were potters and attended the Centre Friends Meeting in southern Guilford County, where William worshiped. Peter Dicks (1771–1843) moved to the New Salem area of northern Randolph County in 1804 and had established a pottery by 1806, when he took Isaac Beeson as an apprentice in that trade.[19] In 1816 Dicks, William Dennis, and three other Quakers were appointed commissioners to lay out the town of New Salem into lots on both sides of the Trading Road.[20] Four years later William purchased lot number 4, built a home, and moved half a mile west of his pottery and former residence.[21] Dennis and Dicks were evidently good friends, as they traveled together to Tennessee and Indiana in 1825–1826. Before moving to Indiana permanently in 1832, William sold Peter a 140-acre tract of land that included William’s former residence, pottery shop, and clay beds.[22]

Biographical and historical accounts indicate that at various times between 1806 and 1837 at least four Quaker potteries were in operation within 1 1/2 miles of New Salem. All of the potters knew one another, attended the same meeting, and interacted socially and commercially on a regular basis. Since many were related, it is logical to assume that their ceramic forms, decorative techniques, kiln architecture, and kiln furniture were similar. Given that their patronage networks were also basically the same, one can postulate congruencies in other aspects of their business as well.[23]

Archaeology

Archaeology at the William Dennis site indicates that the production of pottery there predates documentary evidence. In 1997 the late Tom Hargrove volunteered to conduct geophysical surveys on the William Dennis house and pottery sites to determine subsurface integrity.[24] After Hargrove located the kiln feature, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton partially excavated that site, revealing the footprint of a ten-foot-square kiln with two-foot-thick rock walls (fig. 6). Many contemporary earthenware potters used beehive or bottle-shaped kilns, but square examples are evident in the Quaker pottery tradition.[25] The kiln architecture and artifacts recovered at the site strongly suggest that the pottery was in operation during the last quarter of the eighteenth century.[26] Similarities between the excavated fragments and those from datable Germanic and English pottery sites in North Carolina and elsewhere in the United States indicate that William Dennis was making pottery by the time of his marriage to Delilah Hobbs, in 1790.[27]

Potters and Pottery: The William Dennis Site

Variations in turning, decoration, and other technical and stylistic attributes of fragments recovered from the William Dennis site document the presence of three different potters. Ranging from bold to subtle, these disparities belie the notion that this assemblage of artifacts is the product of a single potter whose work changed over time.

Dish fragments, which account for the highest percentage of artifacts found thus far, can be divided into groups based on shared features and techniques. One group of plain and decorated fragments has heavy, flat-topped rims with tooled outer edges (fig. 7). While these dishes were turning on the wheel, the maker used a wooden tool with a rounded notch to press against the outside bottom edge of the rim in order to give it curvature (fig. 8). A closer examination of these fragments reveals the impression left by the edge of the tool in the clay near the upper outside edge of the rims (fig. 9). The majority of rims associated with this potter have an intentionally sharp interior edge between the rim and cavetto. Similarities also can be observed in this potter’s application of slip. He often used a brown engobe on the interiors of dishes and a white slip to cover the flat rims. The rim of one dish is decorated with large, 5/8-inch slip dots reminiscent of those on late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century slipware from the Staffordshire area of England. Fragments from the bottoms and sides of mugs (fig. 10) attributed to this potter also have details found on early Staffordshire mugs with multigrooved tooling (fig. 11) and on comparable examples made by New England potters of English descent.[28] To produce broad bands of concentric grooves, this potter pressed a rib with multiple teeth against the sides of his mugs while they were turning on the wheel (see fig. 10). Mug fragments by this potter also exhibit glazes in three separate colors—black, green, and a manganese/iron purple.

The potter responsible for another group of dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis site excelled at both turning and slip-trailing (fig. 12). These pieces have a rounded edge on the rim interior and lack the tooled outer edge shared by the examples illustrated in figure 9. They resemble the undercut and rolled rims of many North Carolina dishes made at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Several dish fragments made by this exceptionally skilled hand have engobes that were intentionally darkened to create a dark brown to black background. A reproduction dish based on fragments from the Dennis site shows how the engobe looks in the bisque and glaze stages (fig. 13). Several fragments attributed to this potter are decorated with an unusual winged motif in the form of a dot with an attenuated teardrop abutting each side (fig. 14). The reproduction dish and reassembled fragments illustrated in figure 14 show repetitive use of that winged device to create a circular motif around a flower-shaped design. Related decoration occurs on contemporary Quaker samplers from the Ackworth School in Yorkshire, England (fig. 15), and Westtown School in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[29] Fragments from the Dennis site also indicate that the winged motif was applied directly on the clay body of some dishes. On two surviving examples, the decoration was applied in patterns that appear almost skeletal (see figs. 16, 17). The dish illustrated in figure 16 has a recovery history in Randleman, North Carolina, where New Salem and the William Dennis site are located.[30] On that object and the related examples shown in figures 1 and 17, the marlys are partitioned with vertical lines, squiggles, and dots. As the fragments and reproduction dish suggest, partitioning devices are common on slipware from the Dennis site. Another technique used by this potter was outlining geometric and floral motifs with contrasting slip lines and/or dots (jeweling) (fig. 18). A slip-decorated dish bearing the date 1812 has stylized petal motifs with jeweled perimeters (fig. 19) that match those on fragments from the Dennis site (fig. 20) and the marly of a fragmentary dish found in Randleman, North Carolina, where the Dennis sites are located (figs. 21, 22).[31] One of the fragments with this petal device is from the cavetto of a dish removed from the potter’s wheel with a twisted wire or cord. The marks on the back match those on the underside of the 1812 dish (fig. 23).

The third group of dish fragments, with bottoms ranging from 1/8" to 3/16" in thickness (fig. 24), displays masterful turning. To produce these wares, the potter used buff clay that was finer in quality than the more common reddish variety used at the Dennis site. Surprisingly, the slip decoration on some of the Dennis pottery is not well executed. The stiffness and rigidity of his trailing suggests that his techniques and work habits were not fully developed in that arena. Archaeological evidence indicates that pottery was made with various shades of green, brown, yellow, red, and white slip applied in annular and undulating lines, either directly on the clay body or on a brown engobe (fig. 25). This potter also used motifs similar to the winged device favored by the decorator of the fragments illustrated in figure 14. Sherds recovered at the Dennis site indicate that the potter often arranged his motifs to produce flame or sunburst patterns on the marlys of dishes. The patterns were executed in alternating red and white slip on a light brown engobe, alternating white and brown slip on a plain background, or white slip on a plain background (figs. 26-28).

Despite the differences among these groups of fragments, all the slip decoration associated with the William Dennis site was thinner in viscosity than that used by contemporary Moravians and other North Carolina potters of Germanic descent. The Dennis pottery craftsmen also shared a diverse stylistic vocabulary that included a variety of floral and geometric designs (fig. 29).

Potters and Pottery: The Thomas Dennis Site

Many of the artifacts recovered at the Thomas Dennis site are similar to those found at his father’s pottery. Both men used nearly identical finger-grooved slabs of fired clay as setting tiles. These tiles vary in thickness from 1/2" to 1", and some are fused together with glaze (fig. 30). The slips, glazes, extrapolated forms, and trailed decoration of fragments from Thomas’s site also display parallels with those shown above. The products of Thomas Dennis’s pottery were well turned and decorated, supporting the theory that he trained with William and established his own business about 1812.

Although the slip decoration is dissimilar, a dish fragment from Thomas’s site is closely related in form and profile to an example from William’s pottery (fig. 31). Similarly, a slip-decorated dish fragment from Thomas’s site has a dark-brown trailed design on the rim, a detail executed in green slip on the marly of the 1812 dish (figs. 20, 32). This draping slip design is common on fragments and intact examples (figs. 22, 34) from both sites. The light green engobe used to cover the interior of the dish fragment illustrated in figure 32 does not occur on any other fragments recovered at either site. Although that color could have been intentional, it is equally possible that the decorator inadvertently mixed green slip with white slip.

Distinctive Techniques and Materials

The majority of handle fragments found at both Dennis sites had been pulled to the appropriate size, then attached by pressing them into place at the upper and lower terminal. Often a finger indention was used at the lower terminal to help secure the handle and as a decorative element, and on one fragment the indentation is highlighted with slip dots (fig. 35). Ninety-five percent of the handle fragments from both potteries have molded upper surfaces (figs. 36, 37). They look extruded but actually were pulled by the conventional hand method, laid on a board (fig. 38), and fluted with a small round stick. Drawing the stick down the length of the handle produced carefully regulated parallel grooves that gave the illusion that the handles were pushed through a die.[32]

The clay used for most of the earthenware made at these potteries probably came from the Dennis family’s original 300-acre land grant and the property owned by William’s aunt Rachel (wife of Edward Dennis) and subsequently by William’s son Thomas. When fired, this clay ranged in color from light orange to terracotta. Another type of clay, used less frequently at both sites, was buff-colored when bisque-fired and yellow when glazed. This same clay would have been used in the formulation of slip that fired to a yellow color. Firing temperature, the amount of carbon in the kiln atmosphere, the placement in saggars, and the length of firing time all affected the color of clay and glazes.

The Dennis clay was of such high quality that James Madison Hays used material from the same sources to make salt-glazed stoneware. Between 1871 and 1874 he purchased lot number 4, which included William Dennis’s house, and 140 acres of the Dennis family’s land grant.[33] The clay beds on that large tract sustained Hays’s pottery for at least thirty-five years. His buff clay contained less iron than the red variety and came from a source one mile west of Thomas and William’s sites. Hays mixed the buff clay material with earthenware clay to improve the plasticity and increase the firing range of his stoneware.[34] For his press-molded pipes, Hays used white clay from a source half a mile south of the William Dennis pottery. William’s buff clay and his and Thomas’s white clay probably came from the same sources. The Dennises also used white clay for their pipes as well as for slip.[35]

A disturbed area near the William Dennis pottery yielded an abundance of iron-manganese nodules typically ranging from 1/4" to 1" in diameter (fig. 39). Originally thought to have been a clay pit, this area apparently was mined for those metallic oxides, which were integral components of certain slips and glazes used by the Dennises. Testing revealed that the nodules are very soft and easily ground to the proper consistency. By experimenting with different proportional quantities of these nodules, the authors made a brown engobe that matched the color and texture of that used by potters at the William Dennis site (see fig. 27). To produce the dark-brown to black engobe found on dish fragments from that site, the potters likely varied the amount of iron scale, which is a source of black iron oxide. Formed around the blacksmith’s anvil as a result of forging iron, this easily obtained oxide could be ground together with the iron-manganese nodules. The authors followed that procedure to produce a dark brown/black engobe matching that of the Dennises (see fig. 13).[36]

The slips used by both Dennis potteries are similar in color to the white, yellow, red, brown, and green found on earthenware from other late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century potteries in the piedmont region of North Carolina. The only exception is the light green engobe on a dish fragment from the Thomas Dennis site, but, as previously mentioned, that color might not have been intentional. As was the case at every pottery, accidents, experimentation, and alteration occasionally led to the production of idiosyncratic objects. On the dish illustrated in figure 40, the decorator changed his design by covering a concentric, wavy line of white slip with a broad band of green.

Trailed fragments from forty-three separate dishes were studied from the William Dennis site. Of these, 56 percent have a brown to dark brown/ black slip engobe, 9 percent have a white engobe, and 2 percent have a red engobe. The fact that 67 percent are covered in some form of slip coating is significant, as the application of an engobe over leather-hard clay required an extra, labor-intensive step. The potter had to wait for the engobe to dry before applying his decoration, as opposed to simply trailing his designs directly onto the plain clay ground. White engobe occurs on the interiors and exteriors of several teacup fragments, some having a wall thickness of only 1/8". Turning such thin wares and coating their delicate bodies with engobe required considerable skill.

Engobes were used on the front of dishes and on the interior and/or exterior of hollow ware. The desired glaze color often dictated the placement and color of the engobe. If he wanted to produce a bright apple green, the potter would apply a copper-bearing lead glaze over a white engobe (fig. 41). A similar green glaze applied over a red clay body without the white engobe would fire dark green to almost black.

A small percentage of earthenware fragments from the William Dennis pottery have slip marbling, which was applied in combinations of green, brown, and white; green and brown; and yellow and red. The most intriguing artifact from that site is a bisque-fired fragment from a coggle-edged dish with a marbled interior (fig. 42) recovered near the kiln feature. The very flat and smooth buff and red marbling indicates that the potter pressed the dish onto a drape mold after applying the slip. The dish would have been very similar in form, color, and marbleized pattern to a coggle-edged dish found at Franklin Court in Philadelphia (fig. 43). It is reasonable to assume that experimentation with drape molding occurred at the Dennis pottery site. This technique could have been passed through family members who were interrelated with potters living in Chester County, Pennsylvania, some having apprenticed in Philadelphia (see figs. 4, 5).

Several fragments at the William Dennis site exhibit script writing and designs that were incised in the clay when it was leather-hard. Script writing appears on the sides of hollow ware and saggar fragments, and indecipherable designs or writing appear on the bases of fragments whose forms cannot be extrapolated. “WM” is incised on the exterior wall of one saggar fragment in script resembling that of William Dennis (see fig. 3), while the partial date “181[]” appears on another (fig. 44). Some of the setting tiles recovered at his site were whittled with a knife while in the leather-hard state, and one is randomly punched with holes from a sharp tool. A large fragment of a finger-grooved setting tile has notched edges likely produced with a gouge and triangular indentations running down the center (fig. 45). William and Delilah Dennis had seven boys and three girls, most of whom probably worked in his pottery at one time or another. Those children may have been responsible for some of the more naive marks on the fragments from his site.

The ceramic assemblages from the William and Thomas Dennis sites reveal that New Salem’s Quaker farmer-potters were not just making nondescript earthenware to fulfill everyday utilitarian needs but were experimenting in the production of a variety of decorated wares, including those with rib-generated tooling and geometric and floral slip motifs. The Dennises produced a wide range of designs within their own tradition, experimented with new procedures and techniques, and imitated pottery from other areas. Many of their techniques were labor-intensive and technically demanding, requiring a thorough understanding of the art and craft of pottery making and the ability to apply that knowledge in a distinctive and artistic way.

The only written sources identifying members of the Dennis family as potters are George Newby’s indenture and the biography of William’s son Thomas. Without evidence from their pottery sites, these talented craftsmen would merely be names on a long list of earthenware potters working in North Carolina from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. As the essays in this volume of Ceramics in America attest, considerable progress has been made in identifying the work of those potters. Nevertheless, most of the earthenware surviving from the piedmont region remains anonymous, only a few production sites have been located, and even fewer sites have been excavated. As a consequence, attributions are subject to change as new information emerges about these potters and their interaction with one another and their communities.

The Quaker pottery tradition in the central piedmont region extended beyond the confines of New Salem, where at least four potters and three apprentices worked circa 1790–1837. In Randolph County and neighboring Guilford County, members of the Dicks, Mendenhall, Hoggatt/Hockett, Hiatt, Beard, and other families produced earthenware and/or salt-glazed stoneware (fig. 46). Collectively, these families represent a Quaker pottery tradition that lasted from the third quarter of the eighteenth century through the first quarter of the twentieth century. The William and Thomas Dennis sites represent a starting point in the study of that tradition. Regrettably, many of these ancillary sites are in metropolitan areas and their suburbs and are in danger of being lost forever. The legacy of these early Quaker potters, which represents a integral facet of North Carolina’s ceramic history, can be preserved only by locating, protecting, and researching their sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, Johanna M. Brown, and Wesley Stewart. Special thanks are due to Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton, for her many hours of volunteer work at the William Dennis site; Thomas and Mary Dennis, for sharing their family history and personal insights; Gwen Gosney Erickson, for her assistance at the Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College, North Carolina; and W. C. Hinshaw, for sharing his knowledge of early Quakers in North Carolina.

Deed Book S, p. 387, Chester County Recorder of Deeds, West Chester, Pa. William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 6 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1978), 1:536.

Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:536.

Will of Thomas Dennis II, written June 24, 1774, and proven in February 1775, Guilford County Wills, North Carolina State Archives (hereafter cited NCSA), Raleigh.

The State Records of North Carolina, vols. 11–26, edited by Walter Clark (Goldsboro, N.C.: Nash Brothers, 1907), 22:168. Attached to the oath of allegiance was the warning “all persons being quakers, Moravians, Menomists & dunkards & under the circomstances above mentioned in Law, shall make the following affirmation or depart the State.”

Grant #319, Secretary of State’s Office Records, 1663–1959, bk. 59, p. 361, NCSA.

Deed Book 3, State Land Grant no. 319, p. 52, Randolph County Register of Deeds (hereafter cited RCRD), Asheboro, N.C.

Will of Thomas Dennis, III, written Nov. 11, 1795, and proven August 1803, NCSA.

Randolph County Apprentice Bonds, NCSA.

The Old Discipline: Nineteenth-Century Friends’ Disciplines in America (Glenside, Pa.: Quaker Heritage Press, 1999), p. 92.

Apprenticeship indenture for George Newby, 1813, Randolph County Apprentice Bonds, 1806–1813, CR.081.101.2, NCSA.

History of Wayne County, Indiana, 2 vols. (Chicago: Inter-state Publishing, 1884), 2:447.

Deed Book 12, p. 29, RCRD.

History of Wayne County, 2:447.

Will of Thomas Dennis II, Deed Book D, p. 493, Old Gloucester County Court House, Woodbury, N.J.

Mary Wright Dennis, Thomas Dennis and Some of His Descendants: Circa 1650–1979 (Dublin, Ind.: Prinit Press, 1979), pp. 1–2.

The Old Discipline, p. 99.

William Mendenhall and Edward Mendenhall, History, Correspondence, and Pedigrees of the Mendenhalls of England and the United States (Cincinnati, Ohio: Moore, Wilstach, and Baldwin, 1865), pp. 34–35. Jesse Kersey had finished his apprenticeship five years earlier, under Quaker potter John Thompson of Philadelphia, when he took Richard as an apprentice in 1794.

According to Arthur Edwin James, The Potters and Potteries of Chester County, Pennsylvania (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1978), pp. 141, 202, Nathan Pusey (1748–1832) was a potter in East Caln Township from 1796 to 1800 and in London Grove Township from 1801 to 1812.

Apprenticeship indenture for Isaac Beeson, 1806, Randolph County Apprentice Bonds 1806–1813, NCSA. The terms of the indenture stated that Beeson was to be taught the trade of potter until 1809, when he turned twenty-one.

A timeline of Quaker potters in the New Salem area, based on historical and biographical accounts, can be posited as follows:

1806–1809 Peter Dicks takes Isaac Beeson as an apprentice in the pottery trade.

1811–1821 Thomas Dennis, son of William, active in the pottery trade.

1813–1822 William Dennis takes George Newby as an apprentice.

1821 Henry Watkins takes Joseph Watkins as an apprentice.

1821 Thomas Dennis sells property to Edward Bowman.

1822 Thomas Dennis moves to Indiana.

1830 George Newby is living in Indiana.

1832 William Dennis sells property with pottery shop to Peter Dicks and moves to Indiana.

1837 Henry Watkins moves to southern Guilford County.

1837 Peter Dicks advertises his land for sale in New Salem after moving to

southwestern Randolph County.

1843–1844 Peter Dicks’s son James purchases “1 pair pipes moles [sic]” and

“1 potters lathe and glaseing mill” at his father’s estate sale.

Tom Hargrove, “Geophysical Surveys in North Carolina Archaeology,” North Carolina Archaeological Society Newsletter 9, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 1–2. Hargrove conducted a fluxgate gradiometer (magnetometer) survey and a resistivity survey at both sites.

Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton and Hal E. Pugh, “Arsenic and Old Lead: Recent Excavations at the William Dennis Pottery Site 31RD981,” paper presented at the annual conference of the Society for Historical Archaeology, January 4–9, 2000, Quebec. A second kiln, of similar square design, construction, and dimensions, has been located approximately three miles to the north of the William Dennis site and is also of Quaker origin, being built and used by a member of the Hoggatt/Hockett family of potters.

Carnes-McNaughton and Pugh, “Arsenic and Old Lead.” A perforated, 1774 Spanish one-half real coin found in the northwest wall of the kiln during excavation supports that assertion, while setting a date for the structure above where it was found as no earlier than 1774.

Hal E. Pugh, “The Quaker Ceramic Tradition in the North Carolina Piedmont: Documentation and Preliminary Survey of the Dennis Family Pottery,” The Southern Friend, Journal of the North Carolina Friends Historical Society 10, no. 2 (Autumn 1988): 1–26.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (1950; repr., Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1968), pp. 55, 237; Steven R. Pendery, “Changing Redware Production in Southern New Hampshire,” in Domestic Pottery of the Northeastern United States, 1625–1850, edited by Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh (Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1985), pp. 109, 112.

Ackworth, a Quaker school for boys and girls, was founded in Yorkshire, England, in 1779. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, girls at Ackworth stitched samplers to develop needlework skills. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting founded the Westtown School in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1799 and based its curriculum on that of Ackworth. Samplers made at the two schools are very similar.

The history is recorded on the accession card for dish 89-17, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The authors thank William Ivey for information on the recovery of the dish illustrated in figs. 21 and 22.

On a large handle fragment from the William Dennis site, the pressing of grooves in the front of the handle created indentions from the edges of a board on its reverse side. The potter left these indentions in the back of the handle and utilized it in the design.

James Madison Hays purchased 70 acres of the former 140-acre Dennis/Dicks tract from Noah Jarrell and wife in 1871. Noah Jarrell was listed as a potter in the 1850 Federal Census for the southern division of Guilford County, North Carolina. It has not been determined whether Jarrell continued the trade after moving to New Salem and purchasing the aforementioned property in 1852.

Robert S. Hayes, grandnephew of J. M. Hays; Virginia Wall Hayes, married to Charles Hayes, grandnephew of J. M Hays; and Roy Hayes, grandson of J. M. Hays, interviews by Hal E. Pugh, July 1966.

Ibid. The white pipe clay pit got its name, Deer Lick, from deer repeatedly pawing and licking the clay in search of minerals or salts. Unfortunately, this clay pit was destroyed when the property was graded for a housing development.

The color of iron-saturated engobe also depends on the firing temperature; the higher the temperature, the darker the engobe. Also, with a high content of iron in the slip, the lead glaze will interact and partially melt and darken the slip. In some instances where the engobe is thin, the lead glaze will melt the slip enough to cause transparency. When slipware dishes are stood on edge in the kiln, the lead glaze can interact with the iron slip and cause it to run. This is also very apparent when copper is used as a colorant. Occasionally, it will wash out of the white slip base altogether.