Mug, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

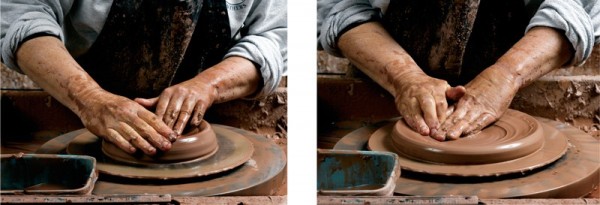

When turning has been completed, finger grooves are apparent on both the outside and the inside of the body. On the outside, use of a rib creates a very smooth surface.

Ribs, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1860. Copper (left) and brass (right). (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

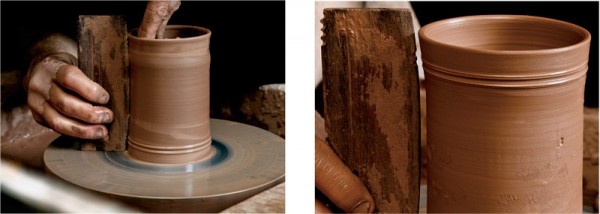

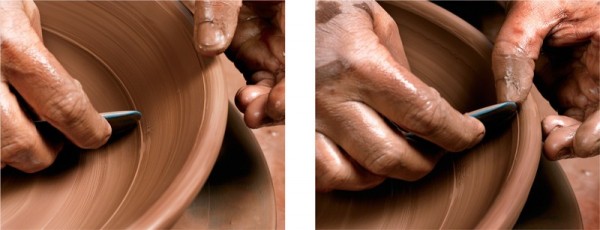

Procedural sequence showing the initial stages of turning an eighteenth-century Moravian-style mug on the wheel. A specified amount of clay is first centered and then raised using only the hands and fingers to form the cylinder.

Once the form of the mug is raised, a grooved rib unique to each size and shape of mug is placed against the surface to produce moldings. Evidence of this technique is found on many Moravian mugs.

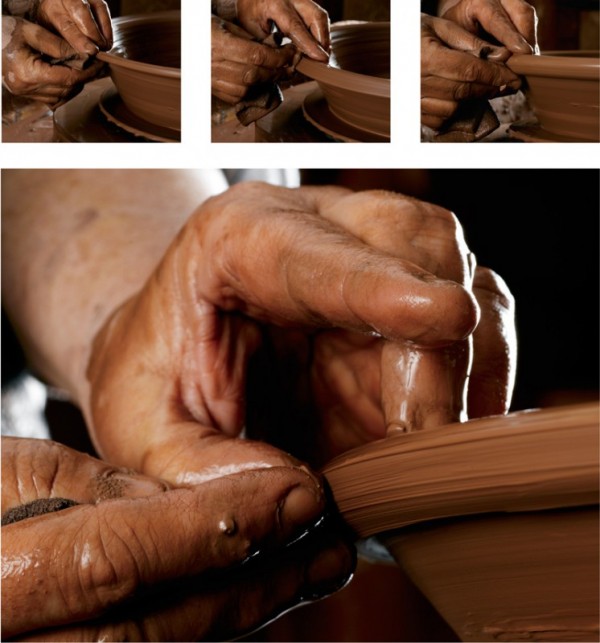

Some North Carolina pottery was cut from the wheel with a heavy string, leaving a shell pattern on the bottom of the mug if the wheel was moving at the time, or a striped pattern if the wheel was not turning. Although David Farrell is demonstrating this technique on a Moravian-style mug, Salem and Bethabara examples usually have smooth bottoms.

Molded handles hanging from an extruder, ready to cut to length and attach. This modern extruder is a bit more technologically advanced than the simple hand-pushed extruders used by Moravians and other North Carolina potters, but the principle is exactly the same.

Various handle terminal treatments were used on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century North Carolina earthenware. A simple thumbprint terminal is shown here, although this technique was not widely used by the Moravians.

Slip cups, Salem, North Carolina, 19th century. Left: Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 2 1/8". Right: Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These cups are typical of the form used by slipware potters in America and Europe. A quill has been inserted into the cup on the left.

Dish, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection.)

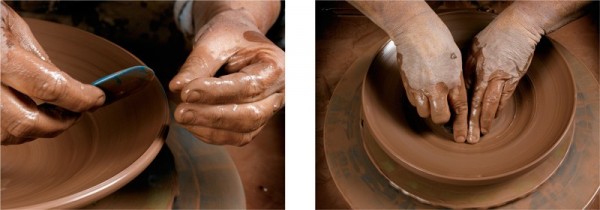

Only the hands are used in the beginning stages of turning a plate or dish. The clay is centered, then opened into a wide cylinder.

After the initial cylinder is raised, a flat or curved rib is used to form the plate or dish shape.

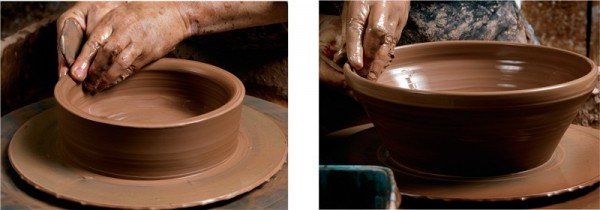

Period Randolph County dishes have a distinctive type of rolled rim. The stages of flipping over the edge of the rim are shown here.

The broad, flat marly is shaped and finished using the rib.

After the dish is turned and shaped, it is allowed to dry to a leather-hard state. The simple slip-trailing is accomplished using a very dark brown—almost black—slip. The wheel is slowly rotated while the concentric bands are applied, then rotated even more slowly while zigzags and the spiraling lines are slip-trailed. As on period dishes by this potter, the zigzags often do not meet up evenly. The decoration is applied with a modern rubber bulb aspirator.

The completed slip-trailed Randolph County–style plate in the wet state.

Dish, probably made during Rudolph Christ’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

The process of forming a Moravian-style dish begins on the wheel with the raising of a broad cylinder. The contours of the piece are shaped with a combination of hands and a rib.

The original Moravian dish has a very distinctive rolled rim, a diagnostic trait on antique examples. This procedural sequence shows such a rim being created, by folding over a substantial amount of clay at the top. The edge comes to a peak before being rolled and rounded.

A curved rib is used to shape the shallow curve of the middle booge. The marlys of Moravian dishes are more concave than many North Carolina examples owing to their makers’ use of a curbed rib to flatten and smooth the surface.

The finished thrown and shaped dish.

After the dish has dried to a leather-hard state, a base coat of cream-colored slip is applied with a brush. Four coats of the base slip are used, with very short drying time between each coat, in order to have a solid base color.

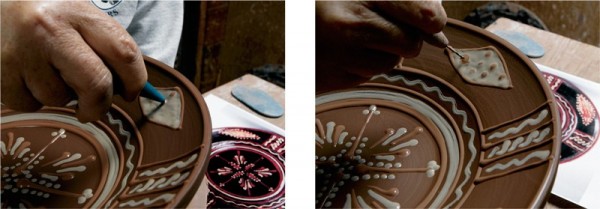

Once the background slip has dried enough so a finger pressed gently to its surface will not mar it, the slip-trailed decoration is applied. This series of photographs illustrates the sequence of laying out the various elements of the floral decoration like on the original (fig. 17). Note the loose, flowing lines used to create the flowers and the fairly simple rim pattern. The application of the slip is sketchlike and can be completed in a matter of minutes.

The replica Moravian plate, shown next to a photograph of the original, is left to dry before being bisque-fired. After being coated with lead glaze, the dish is given a final firing.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 1/2". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Procedural sequence showing the formation of the marly and rim on a replica of the Alamance County dish illustrated in fig. 25. A fairly small amount of clay is folded over and sealed against the underside of the plate. The rim has a relatively straight profile, and on the top surface only the edge curls up slightly.

The Alamance County dish had a small base, a fairly large and steep middle booge, and an upper rim with a curve just at the top edge. The base-to-upper-rim proportion is small.

The inside is coated with black slip. The distinctive shape of this potter’s dishes can be readily seen in this photograph.

Concentric lines of slip are applied to the replica Alamance County dish after the background slip has been allowed to dry somewhat.

The Alamance County potter whose work is being replicated here typically used more elaborate marly decoration than his Moravian contemporaries. He apparently began trailing in the center, then worked his way out. The lozenge-shaped elements are laid out in red slip then filled with white slip.

Dots of red slip are placed systematically on the white ground of the lozenges.

A needle tool is used to create the marbled effects by swirling the dots of red slip into the wet white ground.

The decorated replica dish, shown next to a photograph of the original, is left to dry before being bisque-fired. After being coated with lead glaze, the dish is given a final firing. The heat from the firing and the addition of lead glaze will change the colors of the slips close to those of the original dish illustrated in fig. 25.

Bowl, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 6 1/4". (Private collection.)

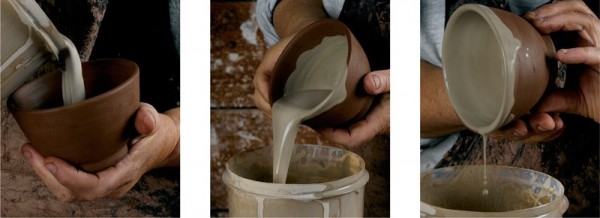

Slip is poured inside the leather-hard bowl to coat the surface, then the excess is poured out.

Dripping various colors of slip is a technique associated with Solomon Loy. This process takes only a few seconds.

On some period examples, it is apparent that the piece was rotated slowly during the application of the slip, which gave the drops a slight curve.

Bowl, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3". (Private collection.)

A bowl, still damp, is dipped in orange slip that is only slightly different in color from the clay the piece is made from. The bowl is then allowed to dry a bit before being slip-trailed.

The bowl is placed upside down on a banding wheel and decorated with cream, green, and dark brown slips. By trial and error, we realized the original bowl (fig. 38) was slip-trailed while upside down rather than right side up.

The replica bowl, just after being slip-trailed. When the piece is dry, it will be bisque-fired, then covered with a clear-firing lead glaze for the final burning.

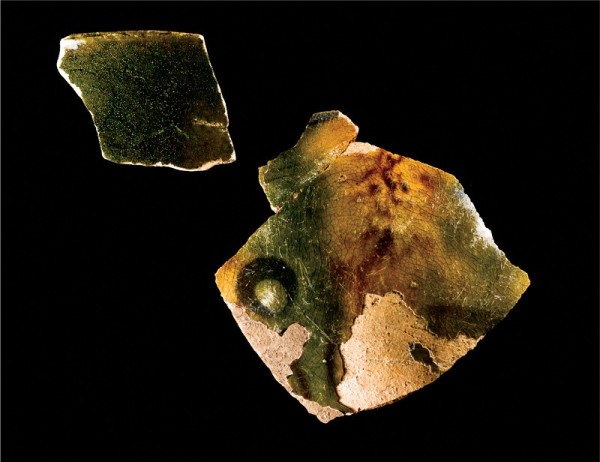

Teabowl fragments recovered at the Mount Shepherd pottery site, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Light-colored slip is poured into a Mount Shepherd–style teabowl while it is still damp. Excess slip is poured out and wiped off the exterior. The wet slip makes the bowl very moist, which could cause the form to collapse, so the bowl is allowed to dry somewhat before the exterior slip is applied.

After a period of drying, the outside of a Mount Shepherd–style teabowl is dipped in the light-colored slip.

On the Mount Shepherd-style teabowl, the slip background is allowed to air-dry completely before the initial decoration is sponged onto the surface in alternating bands. This ensures that the applied copper and manganese oxides will be properly absorbed into the surface.

Once the sponging is completed, a brush is used to apply small circles of manganese oxide and water over the copper oxide bands, as seen on the original specimen.

After the decorated wares are bisque-fired, the final glaze is applied by pouring and/or dipping. During the second firing, this glaze will melt to form a clear glass, allowing the decoration underneath to show through. Unlike period examples, the glaze being applied here is lead-free, so the finished piece can be used safely with food.

I cannot remember when I first began to love early earthenware, often referred to incorrectly as “redware” even though it fires to various shades of white, buff, and red. Whether in its raw state or in the form of finished pottery that we used in our family household, reddish, iron-bearing clays were all around me as a child growing up in North Carolina. I began to make pottery as a teenager and soon became interested in historic ceramics. My husband, David, had followed a similar path, so when we first opened Westmoore Pottery in 1977 in the Seagrove area of North Carolina, it was only natural that earthenware formed an important part of our production.

David and I trained in an academic environment, and both of us had served apprenticeships with working potters. With those skill sets, we began studying traditional pottery forms, styles, and decoration. We had even taught ourselves slip-trailing methods before we met. (The wonderful books about slip-trailing that exist today were not yet written.)

By the time David and I began our business, we were very familiar with a portion of the state’s pottery legacy—that of the late 1800s through the 1950s. Much of the published information related either to stoneware or to earthenware of the twentieth century. North Carolina pottery made before the mid-nineteenth century remained relatively unknown to us. We wanted to learn more about historical pottery, but running a new business consumed most of our time. Nevertheless, we used every resource we could find in the time we could spare. We visited museums with late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century pottery, even those that had only a handful of pieces. The Greensboro Historical Museum and the North Carolina Museum of History both have small collections that were informative. We quickly came to treasure and closely study the holdings of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts and its parent organization, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, which are the primary repositories of early North Carolina earthenware. Of course, we also eagerly studied the few relevant publications we could find, such as The Moravian Potters in North Carolina by John Bivins Jr.[1]

While museum collections contained elaborately decorated examples of North Carolina earthenware, most of the simpler variants were privately owned, and we are fortunate that so many individuals were kind enough to grant us access to their collections. Of the numerous collectors who “took us under their wing,” we are particularly grateful to Bill Ivey—one of our first and best instructors on piedmont North Carolina pottery. His collection, which reflects his appreciation of North Carolina earthenware made before 1840, changes constantly as new pieces come in and redundant examples go out. Countless times over the years he has called or stopped by our shop to say, “Mary, I’ve got a new piece I know you’ll want to look at!” He has an excellent memory, a discerning eye, and the ability to be far less influenced than most collectors by what he wants a piece to be.

Thirty years ago almost every elaborately decorated example of North Carolina earthenware was attributed to the Moravian potters at Bethabara and Salem. This assumption was in some ways strengthened when research by L. McKay Whatley showed that another production site for decorated wares—the Mount Shepherd kiln site in Randolph County—was an offshoot of the Moravian tradition and the workplace of Jacob Meyer, whose persistent bad behavior got him banished from Salem.[2]

In the 1970s and early 1980s, I began to puzzle over contradictions within the group of wares that were said to be Moravian.[3] Among the pieces attributed to Rudolph Christ, there was greater variation in shape than seemed likely in the work of one potter: dish shapes varied considerably, as did rim profiles, and hollow ware ranged from very crude to very fine. As a potter, I can shift easily from one shape to another or one rim profile to another, but I wondered why a craftsman in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries would bother to do so. Most potters’ wares from that time are remarkably consistent.

Even more inexplicable were differences in slip-trailing, a technique almost as distinctive as handwriting. Copying the trailing style of another potter (or changing one’s own) is like trying to forge someone’s signature: the process is consciously deliberate rather than natural. After attempting to replicate many old North Carolina dishes, several of which had been attributed by the academic community to Christ, I became certain that those objects represented the work of multiple hands.

So whose work was I replicating? One possibility was that there were more Moravian potters working at Bethabara and Salem than heretofore believed or that the Moravians hired separate decorators, but neither of those theories is supported by that sect’s meticulous records. On the pages of my old copies of Bivins’s book I penciled in more and more notations such as: “No way could Christ have made this” or “I don’t think this is really Moravian.” Furthermore, the family and recovery histories of several examples of slipware in Bill Ivey’s collection led him to question certain Moravian attributions and reinforced my skepticism.

Now, fast-forwarding more than thirty years, knowledge about North Carolina earthenware is vastly improved. Thanks to those who do primary research in the field, we have documentation for more than fifty-five non-Moravian earthenware potters working in North Carolina in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[4] Of those, there are some to whom no known pottery can be attributed, and of existing pottery much remains anonymous. We do know for certain that several non-Moravian potters were doing highly decorative work.

Pots that have descended in families often offer clues to their place of origin, but much of the surviving earthenware lacks provenance. Archaeological research has identified a few early earthenware potteries in the piedmont, although much work remains to be done before that region’s earthenware traditions can be comprehensively brought to light.[5] Great progress is being made, however, and many of the pots that I used to puzzle over can now be attributed with certainty to various non-Moravian potters, or at least to a particular region of North Carolina.

Exploring North Carolina Potting Techniques

In our first year at Westmoore Pottery, we began to make replicas of early North Carolina earthenware, a way to learn about historic ceramics and work methods that is often vastly underestimated. Replicating an old pot is an excellent way to “get inside” the original potter’s head and better understand his or her world. In trying to duplicate the hand motions of the original potter, methods become obvious that are not apparent from just looking at a piece.

Since the central or piedmont region of North Carolina has abundant naturally occurring clay, North Carolina’s early potters tended to settle there. These early earthenware potters in the piedmont region were from families that had emigrated from Germany or England and entered our state via the Virginia border, coming from states to the north.

Early North Carolina potters all worked primarily on the wheel. The Moravians were the only potters who made press-molded hollow ware, but that work was limited to fine table- and tea wares, flasks, and figural forms. The use of rounded drape, or hump, molds, which was common in Europe and Pennsylvania, has been documented at only one North Carolina site (see Hal E. Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh, “The Dennis Family Potters of New Salem, North Carolina,” p. 163, fig. 42, in this volume). Almost all North Carolina earthenware potters kept the vessel shape that came off the wheel as the finished form (fig. 1), although occasionally there was a little trimming of a foot or rounding of a ring bottle. (Extraneous elements, such as handles, legs, and so forth, were of course added later.) In the final stages of the wheel work, most North Carolina potters seemed to have finished their wares with a rib, known locally as a chip and usually made of wood, leaving the surface very smooth (fig. 2). Moravian hollow wares are unique in the extent to which specially cut wooden and metal ribs were used in their formation (fig. 3). After turning a pot on the wheel, the maker pushed a rib specific to that form against the piece (figs. 4, 5). If the rib had grooves, it produced raised moldings. This was a simple way to add a decorative touch. Though many vessel bottoms are smooth where they were cut from the wheel, some have marks from a rough multistrand string (fig. 6). The Moravian potters also used ribbed extruded handles on their most refined ware (fig. 7). Handle terminals vary, some with elaborate curls at the end, some with thumb impressions (fig. 8).

Beyond general similarities, many differences among North Carolina wares emerge during a close examination of the specific techniques used in creating them: variations in the color and type of clay as well as in the style of the forms; a wide range in the skill level of the makers; differing rim treatments; the diameters of the plate bases, which range from very wide to very small; and the array and quality of decorative elements, which range from very fine slip-trailed representations of flowers to simple but elegant zigzags and lines to seemingly random swipes of brushed slip.

Many North Carolina pots made in the period under discussion are decorated either with slips or with oxides (typically iron, copper, or manganese) mixed with water. Slips are clays to which water has been added. For slip-trailing or painting, the consistency should be similar to yogurt that has been vigorously stirred with a spoon; for pouring or dipping a background surface, a slightly thinner slip is better. The naturally occurring clays in North Carolina can yield slips in shades of white, cream, yellow, orange, and red. Adding iron or manganese, or both, can produce a very dark brown or purple-black slip. Mixing copper oxide with a white or cream slip makes green slips. North Carolina pots from the 1770s to 1840 are often decorated with multiple colors on a single piece.

Slip-trailing was apparently one of the most widespread decorating techniques employed by North Carolina potters. Early craftsmen used a fired-clay slip cup equipped with reeds or quills (fig. 9). We still use these in our business, although I often rely on a rubber bulb aspirator for trailing slip. Many dishes with simple trailed decoration have turned up in Randolph and lower Guilford counties (fig. 10). These examples were thrown and decorated, while still on the wheel, with bands and zigzags, most often with only a dark brown or almost black slip (figs. 11-15). Since the darkest slips are a purplish black rather than a true black, they probably contain heavy concentrations of manganese, along with some iron, rather than any cobalt. If the potters had easy access to cobalt, we would expect to find some evidence of blue slip-trailing. The Randolph County plates also range so much in skill level, both in wheelwork and in decoration, that I suspect they are the work of more than one potter. The ones that appeal most to me include zigzags as well as concentric and spiraling lines, all applied before the plate was taken off the wheel (fig. 16).

As one begins to compare the highly decorated slipwares made by various North Carolina potters, many specific differences emerge. Most potters seem to have made some variation of the plate or dish, usually a double-booge shape and almost always with a thickened rim. The rim was turned over and attached to the underside rather than simply left thickened (as evidenced in fragment cross sections), which makes the dish somewhat less prone to warping and much sturdier in daily use. Variations in the rims, profiles, and feet (if present) are common when comparing the work of different potters.

For the purposes of this article, two elaborately decorated slipware dishes were re-created to illustrate different potting and decorating techniques in North Carolina. One dish was probably made at the Salem pottery during Christ’s tenure as master, and the other is attributed to a potter from the St. Asaph’s tradition of Alamance County. Many dishes from the Moravian and St. Asaph’s traditions are ornately decorated with multiple colors of slip (typically green, reddish orange, and cream-yellow), often applied on a cream, red, or brown ground. The use of dark grounds, ranging from brown to purple-black, is much more common in the St. Asaph’s tradition.

The shape of dishes made by the Moravian potters is quite flat, with a very wide bottom in proportion to the marly and a short, curved transition from the bottom to the marly (fig. 17). Because the marlys are slightly concave, I frequently form them with a curved rib (figs. 18-21). A fairly generous portion of clay is turned over at the edge and smoothed underneath, giving the underside of the rim a rounded shape. Though joined to the clay underneath it, there is a definite demarcation on the reverse side of the plate between the rim edge and the rest of the plate below it. The top edge of the rim comes to something of a point. Despite their curved shape, the marlys of Moravian dishes are very horizontal, so much so that some seem to defy the effect gravity would have had on a piece of wet clay. They almost appear to have been wheel-made with a shaped bat underneath the clay while working, but, if that were the case, those bats should have been included among the many potter’s tools and implements collected by the Wachovia Historical Society at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Replicating the Moravian technique of slip decoration begins with covering the upper surface of the dish or plate with a background slip. This could have been done by pouring on a base slip, but our research suggests that the Moravians applied their engobes with a brush (fig. 22). After the background slip is applied, trailing of the decoration begins (fig. 23). The concentric lines on the marly are applied using a banding wheel so the dish is easily rotated. The slip-trailing of Moravian potters was loose and flowing, with extensive use of floral motifs in the center of the dishes. Lines and zigzags were typically used on the marlys framing the central compositions.

The lines of slip defining the floral or geometric elements come next, followed by filling in of the leaves and petals with different color slips. The completed dish has to dry completely before being bisque-fired (fig. 24). After this initial firing, the dish is covered in a glaze before the final firing. Many of the Moravian plates were fired on edge, so that copper and manganese colorants washed out of the slips in one direction.

The slip-decorated dish illustrated in figure 25 has a purple-black ground, which is typical of late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century work from the St. Asaph’s tradition. The body is thrown on the wheel and, as in the Moravian tradition, the rim turned over, though using a smaller amount of clay (fig. 26). The rolled rims on dishes by this St. Asaph’s potter are not as undercut as those on most Moravian examples. When seen from the side, his rims also have a straighter edge.

The interior profile of many Alamance County dishes is bowl-like, with a gradual but continual curve between the bottom and marly (fig. 27). Dishes by the potter responsible for figure 25 have a double booge, but their profiles differ from those of comparable Moravian examples. The bottom of his dish is small, with a large section leading up to the marly, and the proportion of plate bottom to marly size is much smaller than in Moravian work. The marlys of dishes by this potter are also not as curved as those made by the Moravians, although they do turn upright at the edge. When forming the marlys of dishes like the example illustrated in figure 25, I use a relatively flat rib, and right at the end I curve the edge using my fingers and the rib.

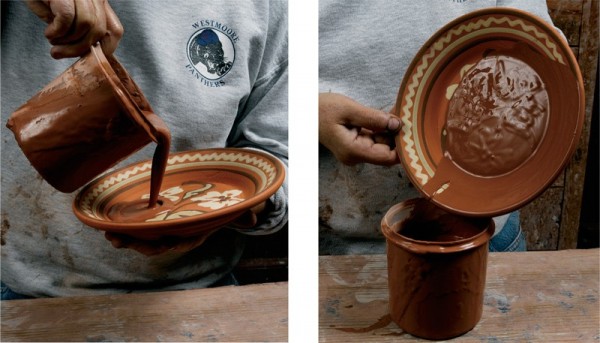

Once the dish is thrown and completely formed, the dark background slip is applied. This engobe is poured into the interior of the dish and the excess poured off (fig. 28). Evidence for this can be found in the drip runs on the back of the dish illustrated in figure 25 and on other Alamance County examples. The slip-trailing on this Alamance County potter’s work is done with short strokes (fig. 29), making it appear less flowing than some work by the Moravians. The marlys on his dishes are usually elaborate (fig. 30), and this example has the highly unusual addition of marbleized lozenges (figs. 31, 32).

Like their Moravian counterparts, the St. Asaph’s dishes were fired twice (fig. 33). Several Alamance County examples appear to have been fired upside down with a post in the center, which leaves a central scar and outward radiating washes of copper and manganese colorants from the slips. This is most visible on the marlys.

Simple yet effective decorative techniques are also manifest in Alamance County earthenware. Some examples have crude, seemingly random brush swipes of slips and oxides, a free-form technique that enhances their charm. The level of skill and artistic vision vary so much within this group of wares that it is almost certainly the work of several potters.

One distinctive technique documented in use by Alamance County potter Solomon Loy consisted of dripping polychrome slip directly on the clay body or on black or cream-white slip backgrounds. Several antique specimens of this type of decoration survive, including small bowls, mugs, saucers, dishes, a vase, and a fat lamp. For demonstration purposes, a small bowl attributed to Solomon Loy was selected for replication (fig. 34). This thrown bowl has a purple-black engobe, which was applied by pouring the slip inside to coat the interior, and then pouring it out (fig. 35). While the ground slip was still wet, drops of various colored slips were applied to the surface (fig. 36). The result is a very abstract pattern of colors and shapes, creating a decorative treatment that appears almost modern (fig. 37). While the pattern seems somewhat random, Loy was able to control the application of the slips to create an aesthetic that must have been valued by his customers and continues to be admired by today’s collectors.

The orientation of wares during the process of slip-trailing often varied from form to form or hand to hand. On some vessels a portion of the decoration was applied with the piece upright and a portion with it upside down, a combination that becomes evident when replicating old wares. Since it is difficult to maintain the gravitational flow of trailed slip on an undercut, some bowls were decorated upside down. A good example of this is the small Alamance County bowl shown in figure 38. In replicating the bowl, the interior and exterior are first covered in an orange slip (fig. 39). The bowl is then turned upside down on a banding wheel to have the trailed decoration applied (figs. 40, 41).

In this brief discussion of decorating styles on North Carolina pottery, I have included examples of slip-trailing directly on the clay body, slip-trailing on engobes, and the dripping of slips. Other techniques that appear in the North Carolina repertoire include sponging of slips and oxides and, on a small group of dishes, sgraffito. Teabowl fragments from the Mount Shepherd pottery site illustrate several of these decorative finishes (fig. 42). From this fragmentary example, we were able to determine that this red-bodied teabowl was dipped on both the interior and the exterior with a white-colored slip (figs. 43, 44). Unlike the other objects presented in this article, the slip on the teabowl had to dry before the additional oxides were both sponged and brushed onto the surface (figs. 45, 46). The finish on this teabowl is very unusual for North Carolina pottery and undoubtedly was intended to mimic English teabowls done in the style of Thomas Whieldon (1719–1795). Similar techniques were employed by the Salem and Bethabara potters in their versions of these “finewares.”[6]

All early North Carolina slipware was allowed to dry after having been decorated, then bisque-fired before being covered in a lead glaze. The glaze, consisting of slip and lead oxides, was applied in liquid form by either pouring or dipping, creating an opaque covering (fig. 47). During firing, the glaze converts to a layer of glass, which fuses to the body. (In the interest of safety and usability, we have developed a lead-free glaze for all of our pieces at Westmoore Pottery.)

With these few replicated examples, some insights into the production and decorating techniques used by North Carolina piedmont potters can be gained. Ceramic historians often describe technical aspects of pottery that they might be ill equipped to understand. Through the actual process of replication, working potters can make valuable contributions to our understanding of historical pottery.

North Carolina has played an important role in the history of American pottery for many years. Potters who worked in North Carolina from the 1750s to the mid-nineteenth century, some highly skilled and some less so, have left us a great legacy. The best of their surviving wares certainly hold their own when compared with pottery from any region of our country. Even pots made by less skilled hands can teach us something about those potters, their lives, and the lives of their neighbors. My learning about this pottery has been ongoing for more than thirty years—a study made with my eyes and my hands, and very dependent on the research of others. I look forward to the knowledge I will gain with each year ahead.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

uch of my education over the years has come from conversations with many people, among them Luke Beckerdite, John Bivins, Johanna Brown, Linda Carnes-McNaughton, Ron and Gwen Griffith, William Ivey, Paula Locklair, and Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh.

John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972).

L. McKay Whatley, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery: Correlating Archaeology and History,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 6, no. 1 (May 1980): 21–57.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina.

Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity: Earthenware and Stoneware Pottery Production in Nineteenth-Century North Carolina” (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1997).

Hal E. Pugh, “The Quaker Ceramic Tradition in the North Carolina Piedmont: Documentation and Preliminary Survey of the Dennis Family Pottery,” The Southern Friend 10, no. 2 (Autumn 1988): 1–26; and Carnes-McNaughton, “Transitions and Continuity.”

See Robert Hunter, “Staffordshire Ceramics in Wachovia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2009), pp. 81–104.