Ai Weiwei, Bubbles, installation view, Watson Island, Miami, 2008. Porcelain. (Courtesy, Bigstock.)

Ai Weiwei, Field, installation view, Art Basel, Basel, Germany, 2010. Porcelain, 291 5/16" x 291 5/16". (Courtesy, the artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne.)

Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds, installation view, Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London, 2011. Porcelain. (Courtesy, Tate.)

“Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn,” installation view, Arcadia University Art Gallery, Glenside, Pennsylvania, February 24–April 18, 2010. (Courtesy, Arcadia University Art Gallery; photo, Aaron Igler, Greenhouse Media.)

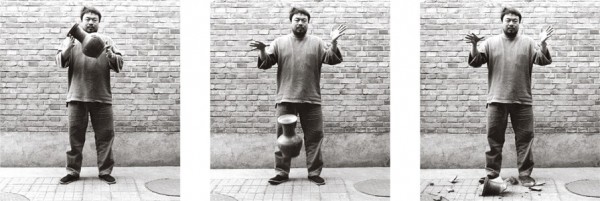

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995. Triptych of gelatin silver prints, edition of 8, no. 4. Each print 49 5/8" x 39 1/4". (Courtesy, the artist.)

Ai Weiwei, Untitled (see fig. 7) and Coca-Cola Vase (see fig. 8), installation view. (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.)

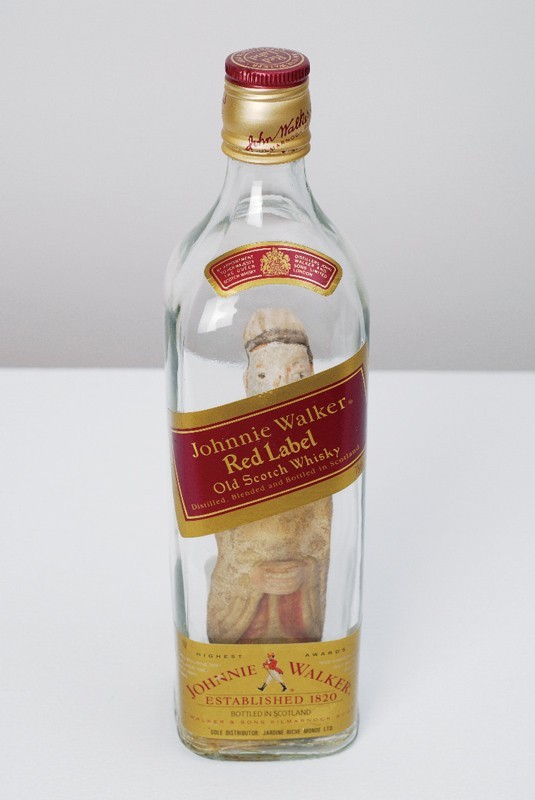

Ai Weiwei, Untitled, 1993. Clay sculpture dating from the Song dynasty (960–1279) inserted within a Johnnie Walker Red Label bottle. H. of bottle 9 5/8". (Courtesy, Urs Meile Collection.)

Ai Weiwei, Coca-Cola Vase, 1997. Vase from Neolithic Age (5000–3000 BCE), painted. H. 11 7/8". (Courtesy, André Stockcamp and Christopher Tsai Collection.)

Ai Weiwei, Colored Vases, 2006–2008. Nine vases from the Neolithic age (5000–3000 BCE) and household paint. H. 10–14 1/2". (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.)

Ai Weiwei, (Making of) Colored Vases, 2006–2010. Twelve production stills from single-channel video. (Courtesy, the artist.)

Ai Weiwei, Dust to Dust, 2009, installation view. Ground Neolithic pottery (5000–3000 BCE) and glass jar. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.)

Ai Weiwei, Souvenir from Beijing, 2002, installation view. Brick from dismantled hutong house, ironwood from dismantled temple from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). L. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, the artist; Leister Foundation, Switzerland; Erlenmeyer Stiftung, Switzerland and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne.)

Ai Weiwei, Template, installation at “Documenta 12,” Kassel, Germany, 2007. Wooden doors and windows taken from destroyed Ming- and Qing-dynasty houses, wooden base. (Courtesy, the artist; Leister Foundation, Switzerland; Erlenmeyer Stiftung, Switzerland and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne.)

Guan with painted decoration of Daoist Immortal, China, Yuan dynasty, mid-14th century. Porcelain painted with cobalt blue under clear glaze. D. 13". (Courtesy, Christie’s.) On July 12, 2005, this jar sold at auction for £15,688,000; Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, Including Export Art, sale cat., Christie’s, London (King Street), lot 88.

Ai Weiwei and Serge Spitzer, Ghost Gu Descending the Mountain, 2006. Blue-and-white porcelain, 96 vases in each group. H. of each vase 10 5/8". Ai Weiwei's studio, Beijing, 2006. (Courtesy, Ai Weiwei and Arcadia University Art Gallery; photo, Aaron Igler and Matt Suib.)

Reverse view of Ghost Gu Descending the Mountain, illustrated in fig. 15.

Two vases from Ghost Gu, illustrated in figs. 15, 16. (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.)

Ai Weiwei, Untitled, 2009. Glazed porcelain. H. 30". (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.)

Interior view of the vase illustrated in fig. 18.

Ai Weiwei, Blue and White Moonflask, 1996. Porcelain, cobalt brushwork, glaze. H. 20 7/8". (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.) This replica is in the style of the Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign-period (1736–1795).

Ai Weiwei, Watermelons, 2006, installation view. Glazed porcelain. H. of each 17 1/2". (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.)

Ai Weiwei, Wave, 2005. Celadon-glazed porcelain. L. 16".(Courtesy, the artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne.)

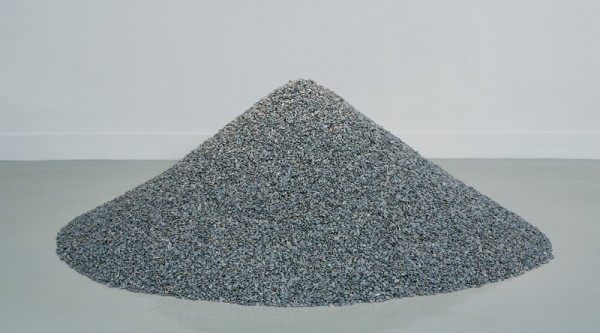

Ai Weiwei, Kui Hua Zi (Sunflower Seeds), 2009, installation view. Porcelain and ink. Diam. approx. 80", wt. 1 ton. (Courtesy, the artist and Arcadia University Art Gallery.)

Visitors walking on Sunflower Seeds, Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London, 2010. (Courtesy, Tate.)

Ai Weiwei, Breaking of Two Blue and White “Dragon” Bowls, performance view, 1996. Porcelain bowls from Kangxi era (1661–1722). (Photo, Ai Weiwei.)

Ai Weiwei, Pillars, installation view, Ai Weiwei’s studio, Beijing, 2006. Sixteen glazed porcelain vessels. H. 70–86". (Courtesy, the artist.)

Ah Leon, Bridge, installation view, Freer Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1997. Stoneware. L. 60'. (Courtesy, Freer Sackler Galleries.)

Contemporary ceramics has never seen a showman like Ai Weiwei. This passionate polymath has taken on the vast history of China’s ceramic art, broken it apart (literally), turned it upside down, reassembled it in fresh ways, vandalized “treasures” by Iron Age potters, questioned the authenticity of his country’s ceramic patrimony, lampooned the connoisseurship surrounding ancient pottery and porcelain, and used the ceramic tradition to critique his government. Driven by near-demonic ambition, he has produced hundreds of major works comprising from one to one hundred million individual components. And he has mounted the largest contemporary sculptural installations in ceramics to date. Ai has revised the ceramic canon and set the bar at a new and intimidating high.

He has produced an ongoing series of major installations, one more dazzling than the other: Ghost Gu Descending the Mountain (2006), several editions (each of ninety-six pots) inspired by the Guiguzi legend; Bubbles (2008), one hundred large blue-glazed ceramic orbs each weighing ninety pounds, was installed on Watson Island off Miami during Art Basel Miami Beach; Field (2010), also at Art Basel, was a vast grid of porcelain scaffolding incongruously decorated with blue early Ming dynasty (1368–1644) motifs; and there is his blockbuster installation at the Tate Modern, which may have lacked conceptual gravitas but still weighed 150 tons (figs. 1-3).

The floor of the Tate’s Turbine Hall was buried under one hundred million sunflower seeds in their husks, handcrafted in porcelain using traditional methods and individually painted by sixteen hundred artisans in Jingdezhen over a period of two years. Three days after the show opened, however, visitors were prevented from walking on the seeds—a significant aspect of the presentation—because the oxide with which they were painted did not “fit” the clay body, and clouds of potentially toxic pigment began to rise in the air. Critics questioned whether, by turning this into a purely retinal experience, the installation had lost both purpose and soul. The debate only added to the work’s media coverage, and attendance was huge, placing Ai at the pinnacle of his fame.

How Ai might top the success of this exhibition is, for the present, a moot question. On April 3, 2011, Chinese police at the Beijing airport arrested him just as he was about to board a flight to Hong Kong. He was held incommunicado at an undisclosed location for three months and then released on qubao houshen, a legal limbo in which charges are not likely to be pressed as long as Ai pays a fine of about $2 million for unpaid taxes and “behaves” himself, which includes not giving interviews and—implied though not explicit—producing art that criticizes the government. If he breaks any of these rules, formal charges could be brought against him and he could be imprisoned again. So while he is physically free, he has effectively been muzzled, which, together with restrictions on travel, puts a question mark over his future as an artist.[1]

The rise of Ai Weiwei’s career has been vertiginous. From 1983 to 1993 he earned his living on the streets of New York City as a quick-sketch artist doing portraits of tourists.[2] He returned to China just as the Western fascination with contemporary art from his country was beginning to explode. It was only in 2004 that Ai had his first solo museum show, at Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland, and he has barely taken a breath since. Last year his name was thirteenth on a list of the one hundred most influential figures in contemporary art.[3] In that relatively short time, as Philip Tinari so well summarizes, Ai has moved “from rebel to craftsman, from provocateur to bricoleur” and has shifted “from Duchamp to Joseph Beuys, from readymade to ‘social sculpture.’”[4]

While Ai works in architecture, design, photography, and film, and utilizes a wide range of materials (wood, plastic, bronze), judging from the number of repeat visits, ceramics occupies a special place. It was therefore exciting to hear of the cleverly titled “Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn (Ceramic Works, 5000 BCE–2010 CE)” organized by the Arcadia University Art Gallery, Glenside, Pennsylvania. The exhibition is currently traveling and will be at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London from October 15, 2011, to March 18, 2012 (fig. 4).

That excitement turned to concern when it was announced that the exhibition would include only twelve works: ten ceramics, one photographic triptych, and a video. Given Ai’s larger-than-life presence, his Warholian celebrity, and the circus accompanying his giant ceramic sculptures, could this modest traveling exhibition do justice to his ceramic adventure?

In a David-and-Goliath turnaround, the show reverses this query. While not its direct purpose, it asks whether understanding Ai is better undertaken in an environment in which subtlety and scholarship can be heard above the media clamor. The answer is an emphatic yes. And the exhibition succeeds so royally because of exceptional curatorship: Gregg Moore and Richard Torchia have assembled an exhibition that bristles with intelligence, careful analysis, and gentle probing.

The equally modest catalog (124 pages) by Moore, Torchia, Philip Tinari, Glenn Adamson, Dario Gamboni, and Stacey Pierson, plus an interview with Ai conducted by Zhuang Hui, is, essay for essay, a delight to read and an impressive scholarly achievement. Moreover, the spacious installation allows each work the space it needs to breathe and, rare in a fine art project, treats ceramics with respect and historical depth, not just as an accidental material (although knowledge of what has been happening in contemporary ceramics over the last half century seems to be missing). The presentation acknowledges that as much as Ai uses ceramics, ceramics in turn use him. The artist and the medium are locked in a partnership of surprising complicity.

The exhibition takes its name from Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), a series of three photographs that dominates the exhibition and is almost always in sight in the gallery, keeping one aware of the fundamentally transgressive nature of his art. Urn is one of Ai’s earliest works, made two years after his return to China. For all the art he has produced since, much of it remarkable, Urn remains his most iconic. The sheer audacity of the act (dropping a museum-quality urn that had survived, intact, for five thousand years) is perfectly balanced by the look of cool detachment on Ai’s face as the vase exploded at his feet into a thousand sherds (fig. 5).

Glenn Adamson, who wrote about this moment in the catalog, takes an interestingly redemptive view:

Shod in traditional cloth slippers he seems in these three heart-stopping filmic moments to stand astride all of China’s culture. Ancientness is made to perform as six frames per second. But this is one big bang we can reverse, by the simple means of reading (as the Chinese sometimes do) from right to left. What could be more touching than his depiction of the artist, gazing implacably as a shattered vessel remakes itself, and floats upward into his hands.[5]

Most read this as sacrilege and accuse Ai the Merciless of creating art by destroying history. The Asian antiquities market was scandalized. But those who knew little about Asian art were even more offended, believing that Ai had demolished an irreplaceable treasure. Urns of this period are relatively common, however, and, depending on condition, can be inexpensive. As Ai pointed out to his critics, the urn was a protoindustrial product, mass-produced in hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of units. If it was industry then, he argued, it remains industry today.

The act was no more barbaric than if an artist five thousand years from now did the same to a vase purchased today from Walmart. Ai has never actually destroyed a work of canonical importance, and yet as late as 2009 the New York Times was still describing the dropped urn as “priceless.”[6] The urn was worth about $10,000 at most.

At its core, Urn is an argument about authenticity. Does the cultural consequence change this common working vessel over time? Is age a valid reason for increasing its value? Does the veneer of antiquity alter an object’s original identity; does it shift from artifact to art? Is the reverence that we accord rarity just a Pavlovian response to manipulations of the centuries-old antiquities market? Is rarity merely an accident of survival, a mathematical equation, and, if so, is the honor we give to survivors misplaced?

Together, Marcel Duchamp’s porcelain urinal Fountain (1917) and Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn provide bookends for avant-gardism in the twentieth century. Both actions, submitting Fountain to the Independents Salon in New York and dropping the urn, created a furor. Duchamp’s took on early modernism, and Ai’s, postmodernism. Both were viewed as offensive and destructive, albeit for different reasons, and the ceramic components met the same fate.

Both were lost (one through indifference and the other by design) and each survives only through photographic documentation. This result was deliberate in Ai’s case, but for the Fountain it was sheer luck in that, according to legend, Alfred Stieglitz decided to document the urinal’s existence before tossing it into a dumpster when he moved to a new studio.

Ai certainly would appreciate the comparison with Duchamp, an artist he reveres. In a conversation with Philip Tinari, Ai commented about violations in his art: “Duchamp had his bicycle seat. Warhol had the image of Mao. I have a totalitarian regime. It is my readymade.”[7]

Ai knows how to soften his blows with humor, sometimes sly and witty, other times with obvious one-liners, but beneath is a ruthless revisionism, and the Urn’s path of destruction (or deconstruction) continues in four other works of the exhibition: Untitled (1993), Coca-Cola Vase (1997), Colored Vases (2006–2008), and Dust to Dust (2009).

Coca-Cola Vase was perceptively balanced by placing it in a spacious cabinet with only one other work, Untitled, Ai’s first ceramic piece (fig. 6). They clearly enjoy each other’s company, almost winking conspiratorially at each other, their logos flashing faux gold and alluding to capitalist sumptuary.

Untitled (fig. 7) pays homage to the childhood wonder of seeing a ship model within a bottle; in this case the bottle bears a Johnnie Walker Red Label and contains a ceramic sculpture from the Song dynasty (960–1279). Once one has gotten over the “how,” the next question is “why?” Confining this crude figure in the bottle is amusing—its two black dot-eyes peer out of the bottle with wide-eyed surprise, as though wondering how it got into its predicament. The piece forces a chuckle.

But it is also unsettling. The message is political, a sly dig at a regime that had begun to practice communism for profit. And the fact that this brand of whisky is the favorite among China’s ruling elite only adds to its resonance. The more one looks at this work, the more uncomfortable it makes one feel. One cannot shake the undertow of imprisonment it suggests: culture held hostage by commerce.

The Coca-Cola Vase (fig. 8) visits the same theme but is more complex. It aims to reach the viewer on two levels, both sensually and intellectually. There is a strong, conscious aesthetic component. Ai did not just slap a logo onto the pot but recognized similarities between the swooping lyrical schemas of Neolithic pottery decoration and the Coca-Cola logo’s voluptuous cursive scrolling.

The painter (probably not Ai himself but working under his direction) has integrated the logo and the contours of the pot, a perfect fit that is enveloping but elastic. At the same time the fragments of the original decoration, seen underneath the logo, draw the past into a dance with the present. Time is one of Ai’s raw materials, and here he gives history an almost plastic consistency, as though it is malleable, pliant, and can ignore the strictures of chronology.

Ai selected Coca-Cola in part because it is both a beloved, iconic consumer product worldwide and a favorite icon of pop art. Aesthetically blissful, Coca-Cola Vase is nonetheless meant to critique unholy alliances, in this case communism and capitalism. In 1979 Coca-Cola became the first Western company permitted to distribute its products in China and today operates more than forty bottling plants and enjoys a 50 percent share of that nation’s soft drink market. In Ai’s mind Coca-Cola is more than a beverage, it is an enabler of Chinese repression.

Colored Vases is part of a long, ongoing series in which Ai decorates earth-toned Neolithic jars and invades them with color. He has been acquiring these jars inexpensively at flea markets in and around Beijing for years and has amassed a large stock. He dips them in industrial pigment—a household paint—using distinctly contemporary colors, more redolent of Tupperware and Martha Stewart than of art. They are startlingly beautiful in their new clothes. The decorative effect of a cluster of these vases is gorgeously vibrant and cheekily fresh. These forms are clearly historical in origin, but he also paints Neolithic pots that have severe geometric form and appear fully modern (fig. 9).

Moore and Torchia contend that this is not a destructive act but more a “gently compromising” device that neutralizes tradition, allowing the contemporary aesthetic values to dominate: “Masking the luster and bold decoration of their original surfaces, the acrylic paint does not destroy the brushwork, which remains intact beneath a veneer of synthetic pigment. The exact contour of their patterning becomes each vessel’s own secret.”[8]

Ai’s view is that “[t]o have other layers of color and images above the precious one calls into questions both [the] identity and [the] authenticity of the objects. It makes both conditions non-absolute. You can cover something so that it is no longer visible but is still underneath, and what appears on the surface is not supposed to be there but is.”[9]

His approach to ceramics is strictly hands-off. He maintained a ceramics studio in Jingdezhen with a staff of twenty and subcontracts work to a small army of more than one thousand independent potters. When asked if he had made any of the sunflower seeds for the Tate project, he admitted, “I made three or four but none of them was any good.”[10]

Dipping the vases in paint is the closest that Ai gets to being a ceramist. (Making of) Colored Vases (2006–2010), the video of him surfacing the pots, shows that the mechanics are identical to glazing, and the chalky matte pastel paint closely resembles raw glaze. The video also reveals Ai’s playfulness, as he moves from vessel to vessel, inventing and reinventing his surfaces on the run; some are dipped in two colors. He sometimes turns the pots upside down so the trickles of colors that flowed upward seem to defy gravity. Clearly Ai relished the simplicity, effectiveness, and spontaneous physicality of this process (fig. 10).

This activity in ceramics is known as “clobbering”—taking an extant ceramic work by someone else and adding surface painting or decoration. It was a popular home industry in the eighteenth century, the purpose of which was to make the object more attractive so it could be sold at a profit. And this is exactly what Ai does, as his groupings are worth many times the cost of the Neolithic hosts. The etymology of the word “clobber”—late-seventeenth-century street slang for beating someone—adds spice, suggesting that even though taking over someone else’s object might increase its value, it also, in a sense, does violence.

This is certainly true of Dust to Dust, one of the best works in the exhibition. As an object, it perches on that slippery cusp between ordinariness and edgy minimalism. It appears at first glance to be little more than a glass jar containing dust. But in fact it is a funerary urn—the dust is ground ceramic “cremains” of Neolithic jars (fig. 11).[11]

Critics have attached a great number of metaphors to this work, including construction sites, the grim brown pallor of Beijing’s polluted air, or the ravaged industrial landscape of China. But it is stronger when viewed simply as cultural mediation between life and death.

The same is true of Souvenir from Beijing (2002) (fig. 12), a gray brick taken from the ruins of destroyed hutong houses (narrow alleys lined with traditional courtyard residences). The brick rests in a coffinlike box made of ironwood salvaged from dismantled temples dating to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Souvenir offers mournful respite, like the public viewing of a body prior to its burial. It finds its twentieth-century parallel in the somber piles of gray felt that Joseph Beuys showed in the late 1960s.

But with Ai there is always subtext. The title questions the rush of developers to modernize Beijing. Moore and Torchia see this as a link both to Template (2007) (fig. 13), a massive gate (which collapsed at “Documenta 12” during a windstorm) made of Ming- and Qing-dynasty doors and windows, and to Ai’s austere but serene brick-based architecture. Bricks, Ai argues, have a “natural relationship with our hands [that allows] us to build [with] them blindly . . . like using words to write something.”[12]

Paradoxically, one of his architectural commissions was designing the Museum of Neolithic Pottery for the Jinhua Architectural Art Park in Zhejiang province, an institution that preserves exactly the same class of wares that he destroyed in Urn and painted in Colored Vases.

The six blue-and-white pots in the exhibition are handsome but reveal a conceptual weakness in Ai’s play with authenticity and provoke the only moment when one misses Ai’s large installations. Three of the cobalt painted vases are Ai’s inventions: two are from Ghost Gu, although they are wrongly described as “replicas” and do not credit Ai’s collaborator on this series, the Romanian-born artist Serge Spitzer; the third is Untitled (2009).[13] The other three are copies of actual works in the style of the Qing dynasty, Qianlong era (1736–1795).

The genesis for Ghost Gu arrived on July 12, 2005, when Christie’s sold a fourteenth-century Yuan blue-and-white pot for $27,657,944 (fig. 14). This surprised the Chinese porcelain market because Yuan works of this period had not previously been accorded such importance. Ai was intrigued by the vase’s rise in fortune, musing why markets upgrade and downgrade cultural values much like Standard and Poor’s bond revisions, but ultimately one suspects he was more amused by market vagaries than perplexed.

The painting on the vase depicts an ancient morality tale: strategist Gui Gu or Guiguzi (his real name was Wang Xu) races down a mountain into a valley to save a disciple. The complexity of the scene is fulsomely described in Christie’s sale catalog:

Robustly potted standing on a broad, low foot rising to a full rounded shoulder below a short cylindrical neck and a slightly thickened mouth rim, vividly painted in a deep and vibrant cobalt blue around the body with a narrative scene that depicts a robed figure seated in a two-wheeled cart drawn by a tiger and a leopard, following two foot soldiers each carrying a spear, approaching a rustic bridge across a stream beneath a waterfall, the cart followed by two equestrians on either side of dramatically painted rocks, one in military attire and carrying a banner bearing the characters Gui Gu, the other in scholar’s clothes, on a prancing piebald horse and turning towards the first horseman, the composition punctuated by pine, bamboo, flowering prunus, plantain, rose and willow, all between a classic wave band around the neck, a peony scroll around the shoulder, and a band of upright lappets enclosing emblems around the base. . . .[14]

Photographs taken in the courtyard of Ai’s Beijing studio show the original conception of Ghost Gu Descending the Mountain, comprising ninety-six pots, exactly as it was installed at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt am Main (figs. 15, 16). It is a stunningly complex vision. When approached from one side, the work appears to be simply white pots, with no sign of decoration. Viewed from the other side, they appear fully decorated. What one sees in the first few rows are pots that have one half of their surface painted. The image is from the original pot but by no means a replica. The painting is heavier, less gossamer, and the pot’s shape is not identical, being slightly squatter, so the image is more compressed. Row by row, then, the painted surface becomes a smaller and smaller wedge. But because the pots in front obstruct one’s vision, all one can see is the painted area, so one assumes they are all the same.

A close-up view of the pots in the rear, however, reveals that only about 10 percent of their surface is decorated. One can see this only because the photograph is taken at an angle. When this work is shown on a pedestal at close to eye level, it seems as though every pot is fully painted, a wonderful tease, as is walking to the other side, where all the painting disappears. An edition of three of this particular installation was made, as well as other editions with variations in the painting and, in some cases, painted red instead of blue. Ai is nothing if not industrious.

The calming rhythm of the assembled platoons of vases is especially satisfying when viewed from a position in which the lines of pots appear diagonal rather than square. A Zenlike tranquillity rises from this assembly, not unlike the hypnotic brickwork on his buildings. We are reminded that Ai has no difficulty with beauty. He may not actively seek it out, but one rarely sees any work by Ai, no matter what its conceptual purpose, that is not also aesthetically pleasing. He is always touted as an intellectual—and he is—but he is every bit a sensualist, thus his ease with ceramics.

Alone, the two vases that are included in the Arcadia University Art Gallery’s show do not quite do justice to Ghost Gu, but they are nevertheless fascinating (fig. 17). First, they are a reminder of the dazzling artisanal skills still available in the ancient pottery town of Jingdezhen and how much they contribute to the bravura of Ai’s ceramics. The ability of these painters to execute this complex scene with such finesse and felicity on a concave 3-d interior surface is nothing short of breathtaking.

Moreover, by placing the image out of sight unless one is standing above the pot looking down into it connects with the ancient practice of anhua, painting “secret” messages on porcelains with white-on-white so they are discernible only at close view. Such messages typically appeared on high-quality, “imperial” porcelains from early in the Ming period (1368–1644). The purpose was not seditious. One will not find slogans reading “Down with the Emperor.” Rather, they impart knowledge about the vase itself, adding a sense of privilege to their owners and, in so doing, flattering their status and the refinement of their connoisseurship.

The ethereal white exterior of pots connects with the Ghost Gu tale. Gui, which means ghost, refers to the mysterious valley into which Guiguzi was descending. According to legend it remained shrouded in mist for years at a time, and its swirling vapors, seen as diaphanous ghosts, were feared. The white vases, seen en masse as in the Ghost Gu installation, effectively convey the sense of a fog blanket.

Untitled (2009), a large handsome porcelain jar with a satin glaze of celadon, is the most successful as a stand-alone work (figs. 18, 19); indeed, multiplication would not serve this work well. Again, only when standing right next to the pot does one see the orb-shaped, blue-and-white ceramic pot with a small mouth that is nestled inside. It suggests an oculus and causes the same strange sensation. The past is looking at us, maybe judging us. It is a direct piece, obvious in its intent and satisfying without the burden of myriad meanings and metaphors that clutter critical writing about Ai.

Three Qing replicas from his Blue and White series—a ginger jar, a moonflask, and a bottle vase—are exquisite and convincing reproductions to the lay eye (fig. 20). This begs Ai’s question, “If there is no recognizable difference between this piece and an authentic piece, then what does this do to the value of the original period piece, or for that matter a modern replica? Let us say we place an exact copy in a museum setting, would this not completely confuse museum goers? Is it real or is it fake? How can a museum exhibit a modern production as an authentic period piece? Does this not undermine the whole system?”[15]

The issue of authenticity—real or fake?—is almost a fetish for Ai, who even named his studio Fake Design (also because of a confusing closeness in the Chinese characters for fake and fuck). But there is something about these works that is a touch self-important. The question Ai poses was answered long ago. The thriving forgery industry in China has been doing an exceptional job for centuries and continues today. Forgers now even mix their clay with grog made from older ceramic sherds to provide false positives in thermoluminescent dating tests. The system long ago adjusted its sampling procedures to deal with this. It poses some threat but nothing calamitous. But scholarship and technology have advanced to such a degree that passing fakes off as real has become much more difficult.

The flaw in this series is that it brings nothing new to the table. These vases could easily just be regular forgeries. Having these commissioned by Ai offers no edge, no greater distinction or different perspective. Slipping them quietly into the marketplace, as forgers do, is a much more destabilizing and seditious act. Yes, he is able to exhibit them in art museums, but still as replicas. Where is the tease? Mixing them in among authentic Qing ceramics in museums might be more provocative.

The subject of forgery in ceramics, hardly a Chinese monopoly, has been dealt with better in the past. Rosanjin, a trickster, eccentric potter, and leading epicurean in Tokyo, shared his glaze recipes and taught forgers how to make his costly and highly prized work, so that after his death they could make perfect copies, a much more Machiavellian assault on future collecting of his work. Ai’s works come nowhere close to this level of transgression.

The exhibition concludes with two snack foods, Watermelons (2006) and Kui Hua Zi (2009). The watermelons, to continue a dietary theme, can be described as Ai Lite: charming and fun but with no great meaning attached. Nor are they meant to be trompe l’oeil images of the real thing. Ai changed the color scheme from group to group, using different yellow and green glaze combinations (fig. 21).

Watermelons belongs to a series of joke pieces that Ai makes from time to time, the most infamous being Pee (2007), disconnected male genitals suspended in the air being held up by a stream of urine. Ascribing anything more than a sight gag to this work takes away its unpretentious pleasures. The same can be said of Wave (2005), a beautiful homage to the Japanese printmaker Hokusai’s image made liquid by a lush viscous celadon glaze (fig. 22).

Kui Hua Zi (Sunflower Seeds) is another matter entirely. It sits on the floor, one ton, more or less, of life-size sunflower seeds in porcelain, painted to mimic the real thing. Its gravitas is both literal and conceptual (fig. 23). When Ai talks about this series it is clear that the sunflower seed is a hugely meaningful thing for him. He recalls that in the labor camp in which his father was held (and where Ai grew up), the detainees would pass seeds to each other as a gift, a rare moment of compassion. And because the act seemed so innocent, it was also a covert way of signifying solidarity. These tales are of course riveting, but they are footnotes. The main subject is Chairman Mao, who during the Cultural Revolution, like Louis XIV before him, was depicted as the sun. Sunflowers are sessile organisms, yet during the day they turn to face the sun, perfect metaphors for Mao’s subjects, obediently facing his heliotropic face. The irony is that under Mao’s rule hunger was widespread and this seed was often the only abundant food staple.

Writing about the Tate’s exhibition of these seeds, Charles Darwent captures the work’s essence: “Each seed offers a kind of hope—of food, of kindness—and yet each is like a minute (and inedible) stone monument, so that the work is at once both lively and deathly. In those contradictions of massive numbers and individuality, of humility and grandeur, happiness and pain, Sunflower Seeds is like China itself.”[16]

The obvious question that arises is whether the message is communicated more effectively by increasing the tonnage of seeds. Does quantity make the work more or less profound? Does the absence of any distinctive form (the floor of seeds is formless) make a difference?

The pile of seeds at Arcadia is a powerful primordial shape, an early burial mound. Yet it also resembles the traditional conical straw hat of the Chinese laborer, about as iconic an image of China as exists. But perhaps its most spiritual connection is as a symbol of a mountain, an ever-present and sacred element in Chinese lore (albeit one of rock and dirt), made up, in this case, of humanity—China’s citizens. There also is a strong contemporary connection to modern minimalism and abstraction. The pile of seeds is about more than just shape, for the seeds rise closer and closer to one’s eye as they approach the crest and, in the process, become increasingly individualistic as we discern that each one is unique. This is masterful, a moving and surprisingly poetic conception.

If humanism is central to this artwork, then that quality is better communicated by Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. The acreage of seeds at the Tate was both dehumanizing and visually monotonous. One had to constantly remind oneself that it consisted of handcrafted seeds and was not just a surface of pebbles or small fragments of gray granite. As for the symbolism of walking on it, when one could still do so, the point totally escapes me (fig. 24). Treading on the populace of China?

Possibly I am making the same mistake that many writers do when discussing Ai, that is, taking his conceptualism too seriously. Richard Dorment takes the argument away from concept and into sensuality:

Like so much else about China, on paper such figures are almost meaningless. Only by seeing it can you begin to grasp its immensity. Standing before it, we look out over an immeasurable, fathomless grey sea. But the moment . . . you step on it, your relationship to what lies beneath your feet changes. Each crunching footstep merely displaces a thin layer at the top of the pile. Our weight leaves no impression on the millions and millions of seeds beneath our feet. What from afar had been far too immense for the imagination to grasp instantly becomes as worthless as gravel.[17]

Still, had it been a vast mountain of seeds 149 times larger than the piece at Arcadia, towering over the viewers, the experience may have been more transformative both visually and conceptually.

The mantra of the Tate’s press office—“150 tons, 100 million seeds, 1,600 workers”—reads more like a hubristic exercise, a warlord bragging about the size of his army rather than having any mathematical logic or even numerological magic. Critic Charles Darwent termed it “almost pervertedly grand.”[18] 133,872,485 seeds might have made more sense of this porcelain mass. That would be one seed for every ten people living in China today. Otherwise, the quantity of seeds appears to have no reason but to impress, an exercise of power on the part of the artist and his host.

The Tate project was received with rapturous praise. Even after the original participatory premise was lost and it could only be stared at from above, the press, first having said that the installation worked because it could be walked on, reversed its position and claimed it was now better because it increased the “sense of sorrow and stillness . . . reinforced allusions both to ash, with its connotations of cremation, and to the fundamental tensions between the individual and the collective in Chinese society, as the field of seeds, seemingly identical yet each unique, laid dormant.”[19]

Weiwei is the darling of the West’s art establishment—both good, because he is a great artist, and bad, because it obscures this fact and turns him into a media star. The combination of his Puckish personality, his generally exceptional art, his eloquence and far-ranging intellect, and the frisson of his life-and-death encounters with Chinese authorities has proved irresistible, creating a climate that is adulatory rather than analytical.

But there has been some criticism from the Marxist quarter, questioning whether, in making this piece, Ai has put himself in a contradictory position. He became the boss man, an employer using the low cost of Chinese labor to make his personal monuments. As such, they contend, he is no different from any other entrepreneur in China who exploits the poorly paid workforce for profit.

This is a baseless argument. First, after two millennia of being the leading center for ceramic production, Jingdezhen is failing and has been forced, through competition from other provinces in China, to make low-quality products. In a decade or two, most of the virtuosic skills for which it is known will have disappeared. Factories are closing, unemployment is high, and the pollution casts a dark gray-brown pall over the “Harmonious Porcelain Metropolis,” as the town is described on a sign welcoming visitors at the airport.

Jingdezhen is suffering the same agonizing fate we witnessed with the fall of the once great Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England, whose ceramic production once exceeded that of China. Stoke has lost its historic potteries. Most now operate solely as brand names, outsourcing manufacture to China and other centers in Asia. The “dole” is the town’s major industry.

Ai has deep empathy for endangered cultural species, and Jingdezhen falls into that category. He was introduced to the town by Liu Weiwei, a ceramic mentor and the manager of Ai’s kilns. They met early in the 1990s at the Beijing flea markets. At that time the numbers of artifacts finding their way to market was staggering, and in a very short period of time Liu and Ai developed an almost scholarly knowledge of Yuan, Ming, and Qing pottery.

About 2001 Liu gave up his market stall and moved to Jingdezhen and introduced Ai to the town. In perfect synchronicity, Liu fires his kilns for only two reasons, for Ai’s work and to produce convincing forgeries of Chinese porcelains that are inserted into auction sales. It is the theme of “real and fake” in daily production.

Ai cannot solve Jingdezhen’s problems nor reverse its decline. But he does bring employment and admits to paying his crafters slightly more than the normal wage, which is fair. Nor does he run one of the ghastly ceramic sweatshops one finds in this town: walls, workers, and floors (where the workers’ younger children play) all caked in red, blue, or other toxic oxides.

Most of Ai’s contract artisans work from small home studios; often couples or family groups do most of the work. If anything, Ai is viewed as an angel in this ancient kiln town, filling thousands of rice bowls that would otherwise remain empty. Also, his employment of those with high skills kept alive a practice that the commercial market no longer requires.

It should be pointed out that in the last decade hundreds of artists, both Chinese and Western, have flocked to this town. It is the Disneyland of ceramic appropriation. There is hardly a style of Chinese porcelain they cannot mimic. But not all work is traditionally based. They also produce contemporary ceramic sculpture—usually in vast numbers and at low cost. Ai is just the biggest and most public of these customers.

He recalls that it was a difficult process, bringing the artisans on board. “I tried to explain to [the artisans] what we wanted them for, but they found it very difficult to understand. Everything they usually make is practical, and the painters are used to creating classically beautiful flowers using a high degree of skill. . . . Now they are asking when we can start again. I shall have to think of a new project.”[20]

Adamson’s essay begins with a good question: “Where is Ai?” Signs asking about Ai’s whereabouts hang on the exteriors of several Western museums. Workers in Jingdezhen ask the same question. But when Adamson made this query, in 2010, he was not predicting Ai’s arrest but rather trying to get into the artist’s head and establish where “Ai situates himself. What is his reality?”[21]

Asking the question with a twist—“Where is Ai in ceramics?”—is instructive. What is his view of ceramics? What are his attachments to the medium? Why does he work so vigorously within this medium? On the surface, Ai does not seem to be much of a fan. In a conversation with the Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ai commented, “Yes, ceramics is kind of crazy. I hate ceramics . . . but I do it. I think if you hate something too much, you have to do it. You have to use that.”[22]

If the purpose was to “exorcise” ceramics from his art, as he says later in the discussion, he has failed magnificently.[23] Every year since returning to China, his involvement has increased exponentially. Ambivalence is more likely his position. And this is not because of the pointless art-versus-craft argument that has dogged ceramics through most of the twentieth century. Ai does not recognize boundaries.

Taking their cue perhaps too literally from Ai’s remarks, the curators in their introduction write of ceramics as though the medium is a pariah, a “contested, schismatic arena” in which “Ai exorcizes (as well as exercises) his contempt for ceramics by his fearless use of it.”[24]

This view of ceramics is outdated. Over the last decade ceramics has become a ubiquitous presence in major galleries. Anthony Caro, Tony Cragg, Jeff Koons, Anish Kapoor, Charles LeDray, Thomas Shutte, and Kiki Smith are among the many artists who have worked in the medium and continue to do so. Even lifelong ceramists such as Arlene Shechert and Ken Price have broken though the clay ceiling into the higher reaches of the canon. Value, too, has adjusted. The medium is no longer “terra worthless” (its nickname in the 1950s and 1960s), with such record sales as the $16.8 million fetched this year by Jeff Koons’s ceramic Pink Panther (1988) at the May 10 auction at Sotheby’s.

Second, these comments impose an early modernist hierarchy and decidedly Western viewpoint of materials on an Asian artist from a country in which ceramics are revered. The rarest porcelain vases are reaching nearly $90 million apiece at auction, largely due to Chinese buyers. What we are witnessing with Ai and his work is a white-hot love/hate affair with all of the ambivalence that generates.

This affair began young. Ceramics was part of Ai’s patrimony. His father, the famous modern poet Ai Qing, was a collector. Ai recalls that even when Qing and his family were banished in 1957 and forced to live in a hut half dug into the dirt on a desert labor farm in Xinjiang (a harsh province bordering Russia in which only 4 percent of the land is habitable), rudimentary shelves held a small collection of Chinese ceramics. Qing was reinstated in 1979, and the family returned to Beijing. One of his first acts was to retrieve the more important ceramics in his collection that had been safeguarded during his banishment. As Tinari perceptively states, “ceramics for Ai Qing was a vehicle for memory.”[25] His son inherited the same belief.

If anything, one senses that Ai finds ceramics overwhelming, loaded with too much history, symbolism, beauty, romance, and allure. It engulfs, frustrates, and excites him. And bear in mind that when we speak of Ai and ceramics, we are speaking of one aspect of a huge field—porcelain, the “white gold” of China. Ai is a porcelain snob, as are the majority of Chinese ceramophiles. He rarely speaks with aesthetic excitement about the Neolithic earthenware pots that he clobbers. Strangely, he also avoids the obvious reference to his Sunflower Seeds installation and the early Ming–era Yixing tradition of making superb trompe l’oeil works of nuts and other foods. But then Yixing wares are stoneware.

However, with porcelain there is rapture. “There were two things in Ancient China that left the outside world incapable of resistance,” he said. “One was silk. The other was porcelain.”[26] It is also instructive that Ai never clobbers antique porcelain. Possibly this is due to a difference in cost, but it also suggests respect. Only once has Ai smashed old porcelains, during a 1996 performance when he broke two blue-and-white “Dragon” bowls from the Kangxi era (1661–1722) (fig. 25). He is shown with hammer in hand, but a white shroud covers the bowls as though he does not want the brutality of the act to be witnessed, an attitude very different from the full frontal destruction of Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn.

Ceramics has its own place in the artist’s oeuvre. It is less political and more likely to express pure beauty than other mediums. Tinari explains this well:

Unlike his reconstructed furniture, Ai Weiwei’s ceramic work could not be interpreted as riffs on historically Chinese forms, and unlike his New York period of conceptual experiments or his later architectural practice, they could not be explained away as homages to Duchamp or modifications of Mies. Tinier and more cunning than the wry subversions of his work in wood, less sarcastic and provocative than his photographs, Ai Weiwei’s ceramic interventions of this brief period are among his most fanciful objects.[27]

He goes on to say, “objects this strange simply did not exist before their creator’s urge.”[28] Tinari’s remark is not accurate, but it is a common misconception about Ai’s ceramics. This has caused some antipathy toward Ai in the clay community, and with good reason. His sight-joke sculptures such as Pee hark back to the 1960s Californian funk movement and the work of Robert Arneson, among others. Smashing pots, forests of seven-foot pots, oil spills with clay and glaze, Coca-Cola logos on seemingly ancient forms, trompe l’oeil dresses and Chinese snack foods, and satiric play with the blue-and-white tradition have been staples, even clichés, on the ceramic scene for decades (fig. 26).

And when it comes to scale and trompe l’oeil magic, there are other artists who have traveled this avenue. Taiwan’s Ah Leon is one example. The Bridge (1997) is a sixty-foot-long gnarly weathered “wood” bridge made entirely of stoneware with seemingly real metal spikes of the same material holding it all together (fig. 27). Ceramists have long followed roads parallel to Sunflower Seeds even if to different destinations. There is little that Ai has done in ceramics that has not been done before him within the contemporary ceramics community.

This a good moment to reverse the question and ask, Where is ceramics in terms of Ai? Where does ceramics place him? Is he hero or villain? The rub for contemporary studio ceramists is less their love of his art—they get it better than most—but their invisibility in these discussions. It would be refreshing if, when ceramics and art are discussed, critics would cross the street, seek some contextual correspondence with the clay community, and give credit for innovation where it is due. But this is an in-house art historical argument. It matters little to the quality of Ai’s art.

Art is not a race in which the first horse out of the gate is declared the winner. The prize, as such, goes to whoever best exploits an idea, whose work is the most transformative in the long haul. While not always the innovator, Ai wins hands down in almost every arena he invades. He has taken ceramic concepts that were at best interesting and made them profound. He has embraced and shed the limitations of the decorative, overturned scale limits, and, to a large degree, reinvented what he has inherited from Chinese clay. It has been a breathtaking, optimistic ride for those of us who a decade ago wondered whether ceramics still had a future in art.

No contemporary ceramics artist has so forcefully and repeatedly thrust clay into the heart of the fine arts, raising the bar at every outing. It is fair to say that because of Ai the arts are more aware of the history, power, and seductiveness of ceramics than at any time in the last one hundred years.

What many have missed is that Ai is the first ceramics star to emerge from China in nearly two centuries. The great irony is that China, the greatest ceramics culture on earth, never made it into modernism. In Europe, America, and Japan, ceramics were gradually transformed, beginning with the Reform Movement in 1850, into an adventurous art form. Were one to list the top one hundred twentieth-century ceramists, there would not be a single artist from the People’s Republic of China. Similarly, if one lists the most important visitors to ceramics, artists who are not ceramists but who worked in ceramics and transformed the art status of the medium in the twentieth century, such as Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, Lucio Fontana, and Isamu Noguchi, again one will not find a single Chinese artist. Until now.

Ai has pushed the gates of Fortress Ceramica—a conservative, cautious, status-obsessed, tradition-bound community—wide open. In this decade we have already seen his influence on the progressive fringe of the ceramics community. He has made it possible for fine arts to travel deeper into the medium and impossible for the medium to ignore its potential and its commercial success. And with modernism’s spell broken, Chinese artists can once again begin to contribute great ceramic art to world culture. The doors are open to everyone in the arts who wants to follow this artist’s example. Everyone, that is, but Ai, trapped, at least for the moment, in legal limbo.

Edward Wong, “Dissident Chinese Artist Is Released,” New York Times, June 22, 2011, available online at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/23/world/asia/23artist.html (accessed July 10, 2011).

See Corey Kilgannon, “Before Fame, or Jail, Ai Weiwei Was a New York ‘Starving Artist,’” New York Times, May 13, 2011, available online at http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/13/before-fame-or-jail-ai-weiwei-was-a-new-york-starving-artist/?scp=2&sq=%22ai%20weiwei%22&st=cse (accessed June 12, 2011).

“2010 Power 100: Annual List” at www.artreview100.com/2010-artreview-power-100/ (accessed June 12, 2011).

Philip Tinari, Peter Pakesch, and Charles Merewether, Ai Weiwei: Works 2004–2007 (Lucerne, Switzerland: Galerie Urs Meile, 2008), p. 121.

Glenn Adamson, “The Real Thing,” in Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn (Ceramic Works, 5000 BCE–2010 CE), edited by Gregg Moore and Richard Torchia, exh. cat. (Glenside, Pa.: Arcadia University Art Gallery, 2010), p. 49.

Michael Wines, “China’s Impolitic Artist, Still Waiting to Be Silenced,” New York Times, November 28, 2009, p. 30, available online at www.nytimes.com/2009/11/28/world/asia/28weiwei.htmlscp=1&sq=China%27s%20Impolitic%20Artist&st=cse (accessed June 12, 2011).

Quoted in Philip Tinari, “Postures in Clay: The Vessels of Ai Weiwei,” in Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn, p. 39.

See the exhibition’s “Illustrated/Annotated Checklist,” available online at http://gargoyle.arcadia.edu/gallery/09-10/Ai-Annotated-Checklist.pdf.

“Interview with Ai Weiwei,” in Shooting Back, edited by Gabrielle Cram and Daniela Zymans, exh. cat. (Vienna: Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, 2007), p. 36.

Charlotte Higgins, “People Power Comes to the Turbine Hall: Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds,” The Guardian, October 11, 2010, available online at www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/ 2010/oct/11/tate-modern-sunflower-seeds-turbine (accessed July 10, 2011).

The title, which references the phrase “earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust” from The Book of Common Prayer and the Anglican burial service, derives from Genesis 3:19 (King James Version): “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”

Ai Weiwei, quoted in “Conversation: Hans Ulrich Obrist and Ai Weiwei,” in Ways beyond Art: Ai Weiwei, edited by Elena Ochoa Foster and Hans Ulrich Obrist (London: Ivorypress, 2009), p. 25.

There was a tradition of painting the insides of vessels, but long after the fourteenth century, when the Yuan pot was made, and usually for smaller objects such as snuffboxes. Also the collaborator on this work, the Romanian-born American artist Serge Spitzer, is not credited. Even more important, the pots were not conceived as stand-alone works.

For a succinct masterpiece of scholarship that tracks all six of the vases in this series and explains exactly why this particular vase is unique and important, see www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_details.aspx?intObjectID=4549655 (accessed June 12, 2011).

Ai Weiwei, interview with Robert Bernell, in Chinese Art at the End of the Millennium: Chinese-art.com 1998–1999, edited by John Clark (Hong Kong: New Art Media, 2000), p. 176.

Charles Darwent, “Why Should Millions of Specks of Porcelain Upset the Chinese? Because Ai Weiwei Never Treads Carefully and Neither, It Seems, Do the Patrons of Tate Modern,” The Independent on Sunday, October 7, 2010, p. 29, available online at www.independent .co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/reviews/ai-weiwei-tate-modern-london-2108669.html (accessed June 12, 2011).

Richard Dorment, quoted in Isabelle Busnel, “We Can’t Walk on Ai Weiwei Sunflower Seeds Anymore. . . ,” November 21, 2010, http://thinkingthroughthings.blogspot.com/2010/11/we-cant-walk-on-ai-weiwei-sunflower.html (accessed July 10, 2011).

Darwent, “Why Should Millions of Specks of Porcelain Upset the Chinese?”

Higgins, “People Power Comes to the Turbine Hall.”

Quoted in ibid.

Adamson, “The Real Thing,” p. 49.

Quoted in Hans Ulrich Obrist: The China Interviews, edited by Philip Tinari and Angie Baecker (Hong Kong: Office for Discourse Engineering, 2009), pp. 24–26.

Ibid.

Moore and Torchia, “Doing Ceramics,” in Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn, p. 12.

Qing brought back ceramics from countries he visited and added them to his collection of Chinese works. “He would spend no money on his trips abroad,” Ai recalls, “and then on last day splurge on very nice [ceramics].” Tinari, “Postures in Clay,” p. 32.

Quoted in ibid., p. 39.

Ibid., p. 32.

Ibid.