Photograph, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. View of Lot 1 at the wharf on the Monongahela River. (Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Center, WVU Libraries.)

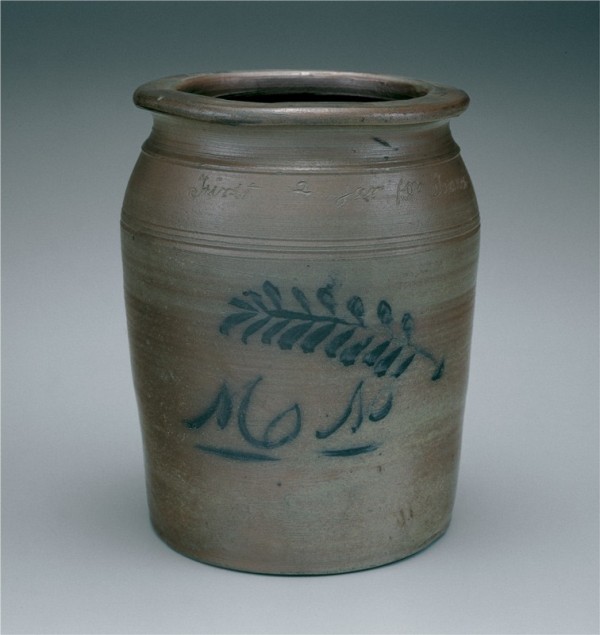

Jar, attributed to David Greenland Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1854. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Inscribed on shoulder: “First 2 jar for Francis Madiera June the 2nd, 1854.” (Duez Collection; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.) Francis Madiera was the postmaster in Morgantown at that time. The same cobalt script “M N” (for Morgantown) occurs on two pieces made by David Greenland Thompson.

Details of the inscription on the jar illustrated in fig. 2.

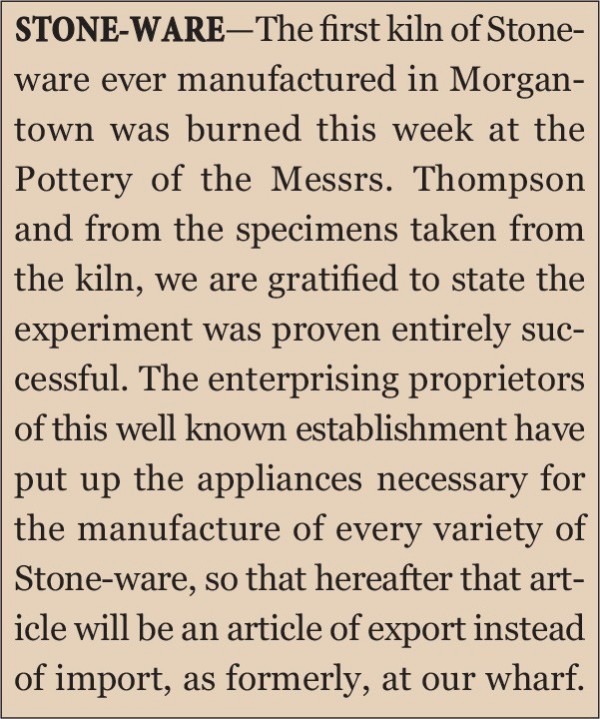

Newspaper announcement, The Monongalia Mirror (Morgantown, Virginia), July 22, 1854, p. 2 (reproduced). (Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, West Virginia University Libraries.)

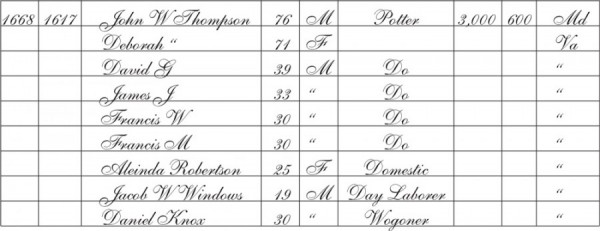

Population census, Monongalia County, Virginia, 1860 (reproduced). The original document, which is accessible online through www.ancestry.com, lists the owner of the pottery shop, John W. Thompson, and his four sons as “potter.”

Detail of the handle on a 15", 4-gallon stoneware jar. Mark, embossed on handle: MORGANTOWN, VA. (Duez Collection.)

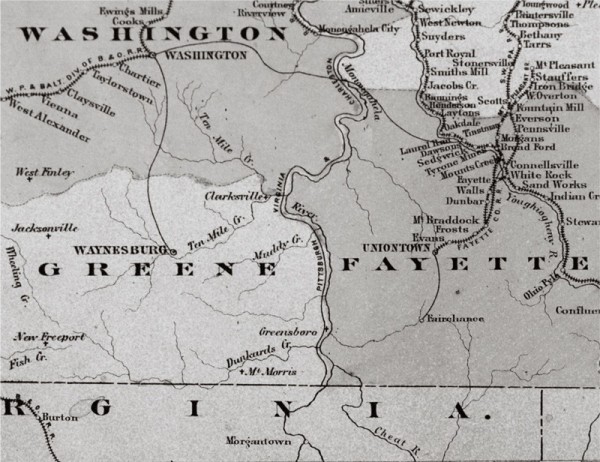

Map of Greene and Fayette Counties, Pennsylvania, illustrated in Caldwell’s Illustrated Combination Centennial Atlas of Greene Co. Pennsylvania (J. A. Caldwell, 1876). (Duez Collection; photo, Dick Duez.) Uniontown, Greensboro, and Morgantown share regional proximity.

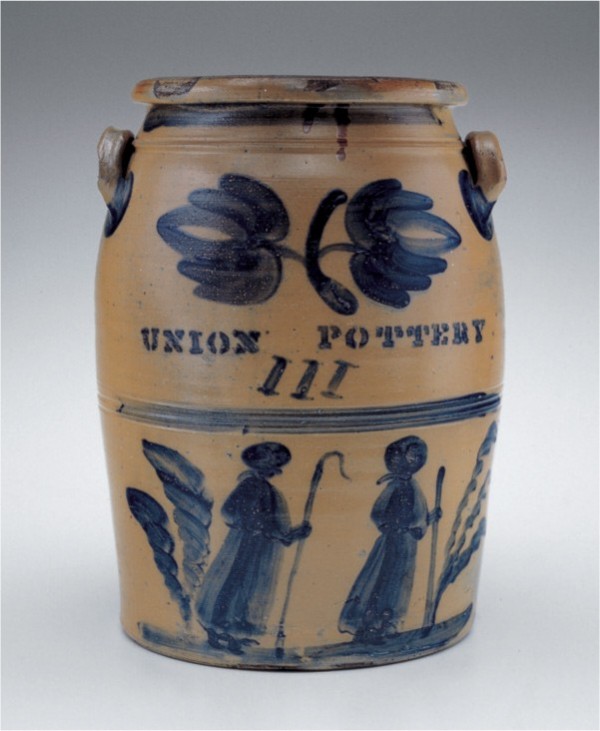

Jar, Union Pottery, Uniontown, Pennsylvania, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. not recorded. Marks: UNION POTTERY / III. (Private collection.)

Jar, Union Pottery, Connellsville, Pennsylvania, ca. 1865. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 3/4". Marks: impressed on shoulder, J. GREENLAND; 3 [gallon capacity stamp]. (Private collection.) The cobalt decoration depicts a marching band of soldiers wearing great coats and kepis.

Detail of the decoration on the jar illustrated in fig. 9; composite image of cobalt designs on the jar.

Detail of the impressed marks on the jar illustrated in fig. 9.

Jar, David Greenland Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Marks: impressed on shoulder, D. G. THOMPSON; 4 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]; Morgantown. (Duez Collection.)

Detail of the marks on the jar illustrated in fig. 12.

Ribs, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1870. Wood. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.) These ribs would have been used to make the heavy rims of the crocks and other pottery pieces.

Jars, Morgantown, West Virginia, (left) ca. 1865, (right) ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (left) 20 1/2", (right) 7 1/2". (Duez Collection.)

Crock, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". (Private collection.)

Crock lid, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 7". (Duez Collection.) This is the only known example of a stoneware lid made at Morgantown. It was found in three pieces at the Morgantown wharf.

Preserve jars, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (left to right) 8 1/2", 8 5/8", 8 1/2". (Private collection.)

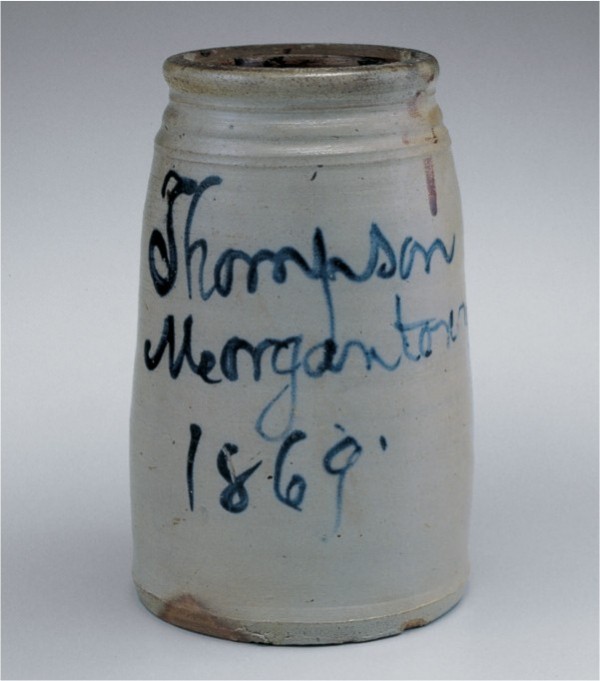

Preserve jar, attributed to David Greenland Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1869. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Marks, inscribed on side in cobalt blue: Thompson / Morgantown / 1869. (Duez Collection.) This piece might have been made to commemorate David Greenland Thompson’s fiftieth birthday.

Bottle, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". (Duez Collection.)

Bottle, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1854–1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Mark: 2 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Duez Collection.) This bottle, which was found in Daybrook, Monongalia County, West Virginia, has a rouletted pattern on its shoulder (see fig. 22).

Detail of the top of the bottle illustrated in fig. 21, showing the rouletted decoration.

Pitcher, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection.) This pitcher has a conical base, cobalt decoration, and a street-scene rouletted design. It was recovered in Grafton, West Virginia, in the early 1970s by a street crew.

Pitcher, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection.)

Pitcher, David Greenland Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Marks, impressed on shoulder: D. G. THOMPSON / Morgantown; 2 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Private collection; photo, Don Horvath.)

Detail of an extruded handle, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Duez Collection.)

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1860s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Mark: 4 [gallon capacity stamp]. (Duez Collection.) The tulip decoration is unusual for Morgantown stoneware; it is more commonly seen on wares by A. V. Boughner of Greensboro, Pennsylvania.

Detail of the embossed handles of the jar illustrated in fig. 27.

Details of embossed handles, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Duez Collection.)

Roulettes, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1870. Wood and bisque clay. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.)

Roulettes, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1870. Bisque clay. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.)

Pottery stamps, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1870. Bisque clay. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.) These stamps were used to impress small decorative elements onto the wares.

Roulette, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1870. Bisque clay. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.) This stamp would have been held between two fingers in order to roll the design onto the ware.

Detail of the impressed design made from the roulette illustrated in fig. 33.

Roulette, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1870. Wood and bisque clay. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.)

Detail of the impressed design made from the roulette illustrated in fig. 35.

Roulette, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1870. Wood and bisque clay. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.)

(Left) Detail of a rouletted design on an earthenware jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1840–1854. (Private collection.) (Right) Detail of a rouletted design on a stoneware jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1860–1870. (Private collection.) The roulette tool used to make the design on both jars is illustrated in fig. 37.

Capacity stamps and master stamp molds, Thompson Pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1850–1890. Bisque clay. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.)

Details of gallon capacity stamps from various Morgantown jars.

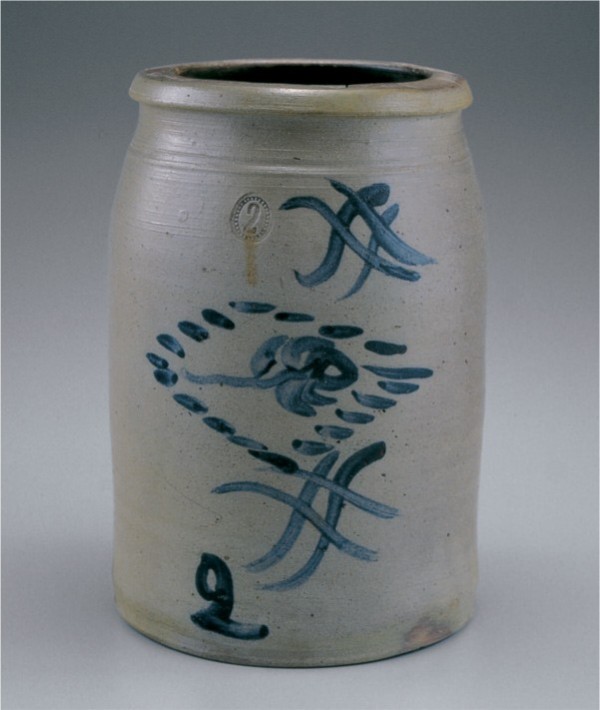

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1854–1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Marks: 2 [impressed gallon capacity stamp]; 2 [inscribed in cobalt]; Steam / Bote [inscribed on bottom]. (Duez Collection.) This jar is decorated with a cobalt Tic-Tac-Toe motif of the type used during the earthenware period.

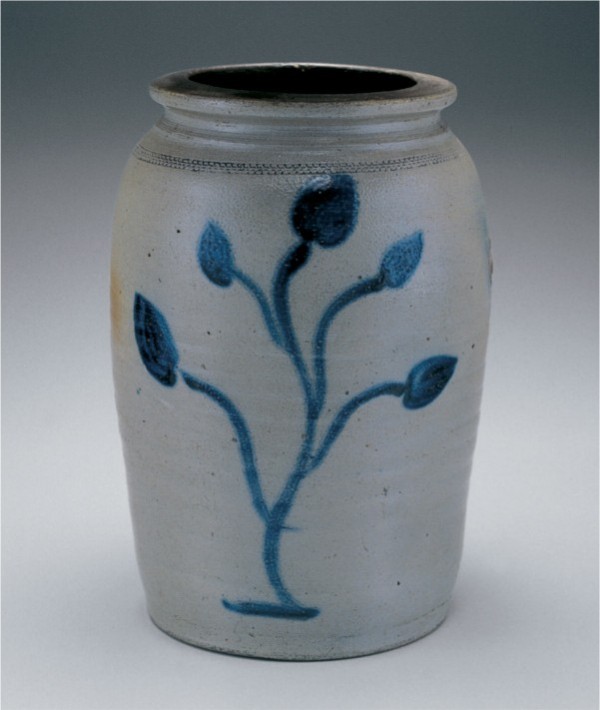

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/4". Mark: 2 [beaded gallon capacity stamp]. (Duez Collection.) A budding branch decorates this stoneware jar, which has a history in Marion County, West Virginia.

Crock, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1860–1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Mark: 2 [impressed gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Duez Collection.) The floral decoration on this handled crock is enhanced with a rouletted street-scene pattern. The crock was found in Kingwood, West Virginia, where it had long been used in the making of buckwheat cakes.

Churn, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1860–1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Ken Landreth.)

Jar, attributed to Frank W. Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1865–1875. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/4". Mark, impressed on shoulder: F. W. Thompson / Morgantown. (Ken Landreth Collection.) This jar is the only known piece that bears what seems to be a reference to Frank W. Thompson.

Jar, attributed to Frank W. Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1865–1875. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/4". Mark: 2 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Private collection.) Based on its similarities to the decorated jar illustrated in fig. 45, this example was probably decorated by Frank W. Thompson as well.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Private collection.) Rendered in cobalt slip on the side of this jar is a woman holding a flag, with trees on either side of her. The scene is framed at the top by a feathery arc, also in cobalt slip.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". (Private collection.)

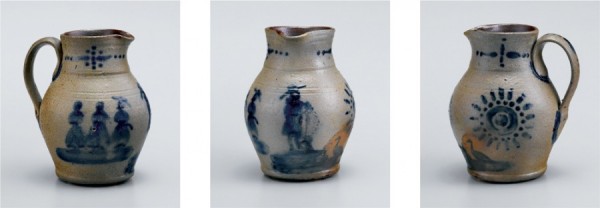

Cream pitcher, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4". (Private collection.) This pitcher, purchased in Grafton, West Virginia, is decorated with an elaborate sunburst, four human figures, and a duck or goose.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. Mark: 2 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Private collection.)

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1854–1865. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 13/16". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This jar was found in Aurora, Preston County, West Virginia. A simple rouletted pattern with chevrons is impressed around the shoulder. The cobalt decoration shows a man and a woman, each holding a gun, facing each other. A nearly identical rendition of the figure on the left appears on the jar illustrated in fig. 50.

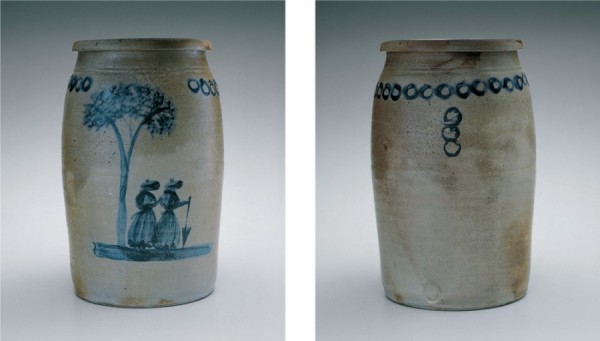

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". Mark: 2 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Private collection.) This jar was found in Upshur, West Virginia. The painted decoration shows two women, one with a parasol, under a tree. The cobalt chain decoration around the shoulder is unusual for Morgantown stoneware.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". Marks: 4 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]; D. G. THOMPSON / Morgantown. (Private collection.) The cobalt decoration includes a sponged pattern around the rim and a sponged crescent arcing over a woman holding a parasol. The jar was found in Fairmont, Marion County, West Virginia.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". Mark: 3 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Private collection.) The scene illustrated here shows three women standing between two trees. The capacity stamp is filled in with cobalt.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1854–1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Private collection.) The cobalt decoration shows a whale framed within a sponged pattern.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1854–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 19". Mark: 8 [gallon capacity stamp within a beaded circle]. (Courtesy, Northeast Auctions.)

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1875. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 20 1/2". (Duez Collection.)

Flower pot, attributed to David Greenland Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1885. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". (Photo, courtesy of James and Karen Giuliani.)

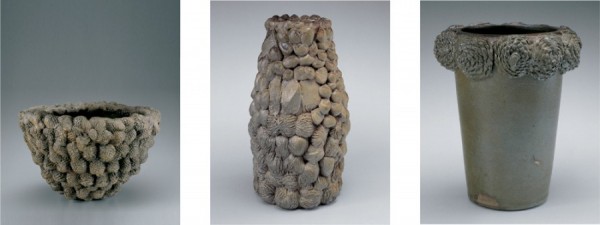

Vases and bowl, attributed to David Greenland Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1885. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of center vase 9 1/4". (Duez Collection.) Nuts, peach pits, and freshwater clams are all part of the applied decoration covering these objects.

Pitcher, attributed to David Greenland Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1885. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". (Private collection; photo, Don Horvath.) The pitcher is covered with applied leaves and stems. Applied lettering around the neck spells out “F. M. Haymond,” one of Thompson’s relatives.

Our 2004 Ceramics in America article, “The Potters and Pottery of Morgan’s Town, Virginia: The Earthenware Years, Circa 1796–1854,” introduced readers to the early earthenware pottery that was manufactured by the Thompson family of potters. Through archaeological discoveries and studies of their glazing techniques and the forms they made, the potters of Morgantown became better known and their products recognizable. Readers also learned of the succession of potters and other associates, apprentices, and family members who attempted to operate a pottery manufacture along the Monongahela River.[1] The Thompson family, who gained a stronghold in earthenware manufacture in Morgantown though few of their earthenware pieces survive, would be the potters to carry the industry through to stoneware.

Since the publication of that article, research into the Morgantown potters’ stoneware has continued. The variations of form, the decorative styles, and the tools they used to create their wares provide important information about the American pottery industry in the mid- to late nineteenth century and, more specifically, about the operations of this particular one.

Many of the decorative techniques used on the stoneware are attributed to David Greenland Thompson, a son of John Wood Thompson, and were introduced as the Morgantown pottery transitioned to stoneware. Given that this stoneware production occurred over a period of approximately three decades, it is not possible to identify the thrower and decorator of every object. It is reasonably certain that two of them are David and his father, however, and this article focuses on their skill and creative development.

“We are gratified to state the experiment has proven entirely successful”

By 1850 the Morgantown Pottery, whose original location on Lot 88 had burned down in 1830, was firmly established on Lot 1, next to the wharf on the Monongahela River (fig. 1).[2] The 1850 census shows four Thompson men working at the pottery: John W., his brother Francis M., and two of his sons—Francis (Frank W.) and David Greenland. In 1853 the Morgantown Pottery passed from John W. to his son James Jackson Thompson, then later to James’s brother Francis (Frank W.). During this period, the ware production moved from the “porous terra cotta covered with a yellow lead glaze” to salt-glazed stoneware.[3]

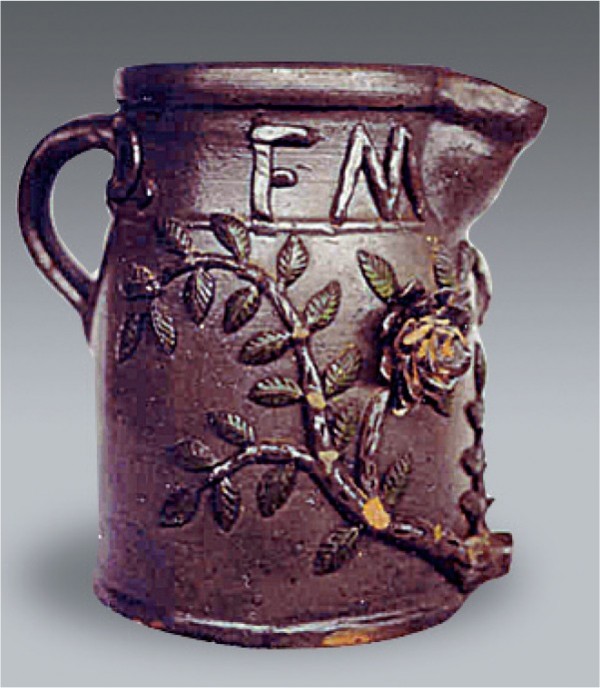

A rare insight into this transition is documented on a jar bearing the inscription “First 2 jar for Francis Madiera June the 2nd, 1854” (figs. 2, 3).[4] The body is primarily a salt-glazed gray, with ruddy streams of red running through it. On the side in cobalt blue are a fernlike decoration and an inscribed “M” and “N” (for Morgantown). The identical initials occur on two pieces signed by David Greenland Thompson, which might indicate that he was the maker or decorator of this magnificent piece.

In the Monongalia Mirror of July 22, 1854, the Thompsons announced production of their first stoneware: “The first kiln of Stone-ware ever manufactured in Morgantown was burned this week at the Pottery of the Messrs. Thompson and from the specimens taken from the kiln, we are gratified to state the experiment has proven entirely successful. . . . [H]ereafter that article will be an article of export instead of import, as formerly, at our wharf” (fig. 4).[5]

By the time of the 1860 census, James J. had joined the other four family members at the pottery (fig. 5). Three years later John W. died, and at the outbreak of the Civil War his sons James J. and Francis W. enlisted as officers in the Union army, leaving David Greenland to run the pottery. The Civil War caused a shift not only in the American economy and industry but in political boundaries as well, one of which resulted in the creation of West Virginia. It is thought that many of the more complex decorative techniques, such as the use of roulettes, stamps, and painted images, were implemented in the workshop during John W. Thompson’s lifetime and ended with his death (fig. 6).

The Thompsons’ transition to stoneware manufacture was made possible by an earlier discovery of a suitable stoneware clay seam in the Monongahela Valley of Pennsylvania, just across the river from Morgantown in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. As a result, a multitude of Pennsylvania potteries shifted from earthenware to stoneware.[6] As early as the late 1840s and early 1850s area potters began to produce salt-glazed stoneware from the “very fine bluish white clay.”[7] Three miles north of Morgantown, in Collins Ferry on the Monongahela River, William Crichfield was making stoneware as early as 1844.[8] Alexander Boughner, who began stoneware production in the late 1840s, was one of the earliest to do so in the Greensboro area of Pennsylvania.[9]

In addition to their accessibility to suitable stoneware clay, the Thompsons benefited from their proximity to the region’s water-based transportation system. Use of the river greatly increased transportability and availability of the materials needed for stoneware production (fig. 7). A canal connecting the Monongahela River to other waterways in Pittsburgh opened in the late 1820s. This became useful for more rapid transportation and access to other cities along the rivers. The canal also expanded the market of many potters, allowing them to transport their pots to Ohio, Indiana, as far south as New Orleans, and wider markets in the East. Shipping materials on the river also made salt glazing more cost effective. Readily accessible salt came in large quantities and could replace the use of lead for glazes, known as a hazard to both the consumer and the producer.[10]

Family Connections: Potters of Uniontown and Connellsville, Pennsylvania

For this article it is important to recognize family ties. Many characteristic Morgantown pieces are attributed to potters who worked in Uniontown and Connellsville, towns in bordering Fayette County, Pennsylvania (fig. 8).

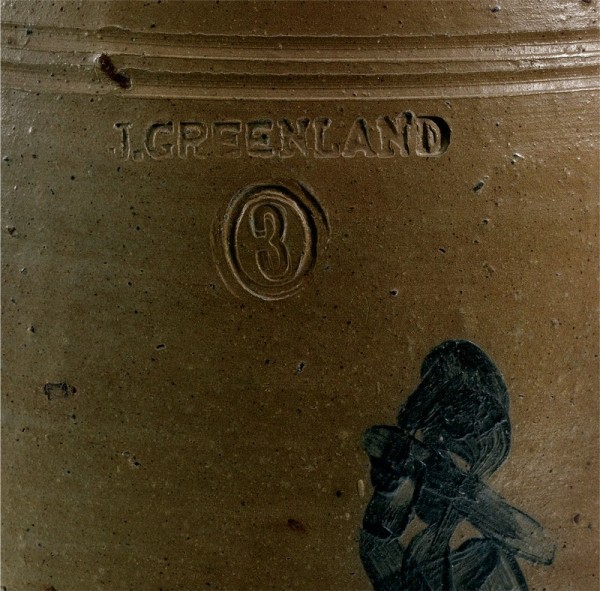

Abner Greenland was a well-known, early earthenware potter of Uniontown. In 1806 he married Jane Thompson, sister of John W. Thompson,[11] and they had two sons, John and Norval. John Greenland was listed as working with his father in the late 1820s shortly before his father’s death in 1830.[12] In 1859 he was listed as running a store in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, and in 1872 as operating a firm called Greenland & Son, Manufacturers of Stoneware.[13] Norval Greenland remained in Uniontown, but in an 1859 directory was listed as a wagonmaker.[14] In 1864 Norval formed a partnership with one Cromwell Hall and developed a stoneware production business under the name Hall & Greenland. The partnership ended by the 1870s, but Norval Greenland did not end production until 1882.[15]

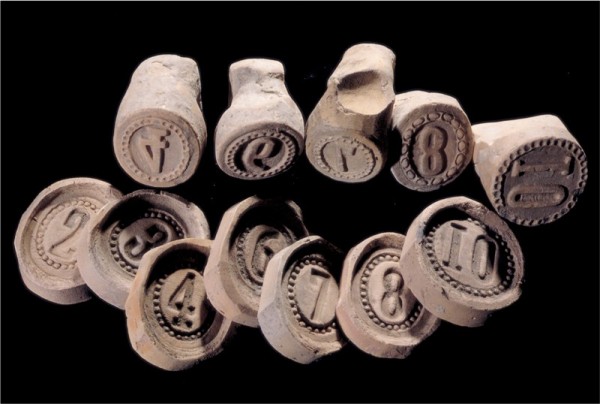

John Greenland made one of the best-known Connellsville pottery pieces (figs. 9, 10). The estimated date of manufacture is circa 1865, and the decoration likely commemorates the end of the Civil War. The cobalt-blue decoration on the jar displays human figures marching with guns, led by a small instrument band complete with a leader. The images on the jar as well as the form, which bears a capacity stamp (fig. 11), attest to the similarities of Connellsville, Uniontown, and Morgantown pieces. Marking the capacity with signature stamps and designs became a trademark of the Morgantown pottery and can be seen on almost every piece produced from 1855 to 1870. The transition of the Morgantown potters to stoneware production was accompanied by a remarkable expansion of the use of roulettes and the acquisition of unique molds for handles, or lugs.

“Wares of the Second Period”

In 1901 Walter Hough, assistant curator in the Smithsonian Institution’s ethnology division, published a report entitled “An Early West Virginia Pottery” in which he labeled David Greenland Thompson’s stoneware products as “wares of the second period.”[16] Ceramics historians are in great debt to Hough, a West Virginia native who worked to collect the tools of the Morgantown pottery shortly after it closed. These extremely rare survivals went to the Smithsonian, as did some examples of stoneware and earthenware—several of which are stamped “D.G. THOMPSON” (figs. 12, 13).

The tools that Hough collected highlight the variety of techniques employed by the Morgantown potters. A number of shaping ribs (used to smooth the sides of pieces) are included; some are actual ribs of animals but most are of wood. There are throwing tools for incised lines, trimming clay, and tools used to lift the pieces of pottery from the wheel. There are other wood implements used to shape the rims and molding during final finishing. The profile ribs illustrated in figure 14 assisted in forming the heavy banded and often angled rims seen on the Morgantown jars and crocks.

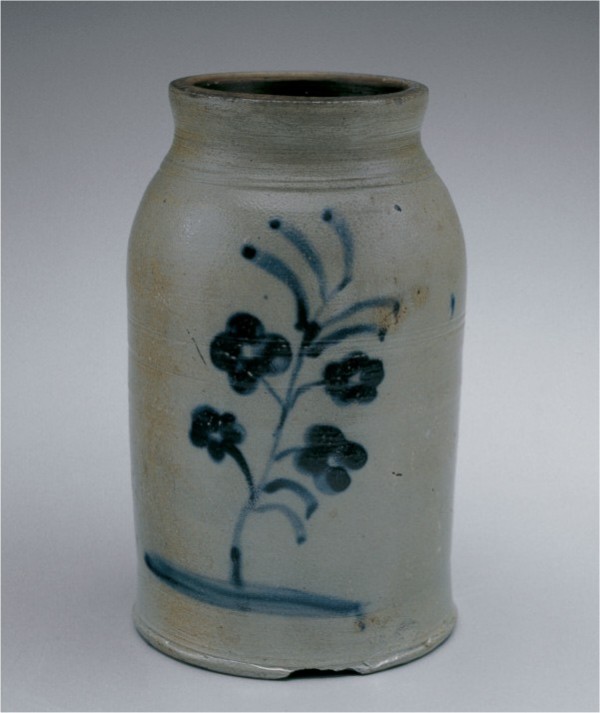

Crocks and jars dominate the Thompson factory’s surviving forms, although the potters were skilled at making a variety of forms in a variety of sizes (fig. 15). Jar sizes from one-half gallon to ten gallons have been recorded. Surviving cake crocks are somewhat rare (fig. 16), and the only known lid comes from an example pieced together from fragments found on the site of the pottery (fig. 17). A particularly distinctive form in the Morgantown production is the tapered preserve jar, sometimes called a wax sealer (figs. 18, 19).

Bottles and jugs with high, rounded shoulders and gently flared feet are known (fig. 20). Many have cobalt-blue decoration, and some have a rouletted pattern following the shoulder (figs. 21, 22). Many of the pitchers have bellies similar to those of the tapered preserve jar (figs. 23, 24). An unusual example with cobalt-blue floral decoration has the stamp of David Greenland Thompson (fig. 25).

The Smithsonian collection of tools from Morgantown includes implements for making the handles for the stoneware jars and jugs.[17] Extruded handles made with precut dies created a uniform design and sizes; most of the jar handles were extruded with fairly simple profiles (fig. 26).[18] Some of the handles were embossed after having been extruded and applied to the jar (figs. 27, 28). The attention to detail across the top of each lug handle is exquisite and generally seen only in Morgantown examples (fig. 29).

The decorative technique of rouletting was used on Morgantown earthenware before it was applied to stoneware. Precisely when and under what circumstances David Greenland Thompson obtained the concept of roulette-wheel decoration is not known. William Ketchum has noted that potteries in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York were employing such decorations as early as 1830.[19] Perhaps Thompson had traveled to one of those manufacturers, or perhaps, given his proximity to the river systems, he had seen wares with this characteristic being transported or traded.

These roulette wheels are made of a bisque clay material and fitted in wooden handles (figs. 30, 31). A number of small decorative stamps are part of the tool assemblage as well (fig. 32) and might have served as the positive masters to create the rouletted designs. Many of the designs carved onto the roulettes are detailed and intricate. There are several street scenes with well-defined small buildings and animals (figs. 33, 34). Some create a pastoral landscape complete with hay wagon, small structures, and trees (figs. 35, 36).

The use of these elaborate roulettes on Morgantown seems to be restricted to the 1850s and 1860s. Some rouletted patterns carry over from the earthenware period (figs. 37, 38). After David Greenland Thompson acquired the shop in the 1850s, the designs became more varied and were widely used on multiple forms. After the mid-1860s the use of rouletted decoration on Morgantown pots waned, perhaps becoming too labor intensive to use in conjunction with these utilitarian objects.

In addition to the roulette wheels, the tool collection in the Smithsonian includes beaded stamps used to mark the capacity of the wares (figs. 39, 40). These stamps are associated primarily with the Morgantown pottery, although some of the Uniontown pots bear similar markings. The beaded capacity stamps continued to be used through the 1870s.

While beaded stamps continued to be used, floral cobalt decoration dominated through the 1870s on the Morgantown products. The decorative fern on the 1854 jar illustrated in figure 2 reflects the shift toward cobalt decoration within the budding stoneware industry of the Morgantown pottery. These fernlike decorations had not been widely used on the earthenware forms, although the so-called Tic-Tac-Toe design is found on both earthenware and stoneware (fig. 41). Cobalt was the most expensive commodity in a potter’s studio in the nineteenth century, and potters would often mix it with a slip made from the clay body they were using in order to make it last longer.[20] Typically, cobalt was applied with a brush, though a sponge was used on several pots attributed to the Morgantown pottery.

Wares from southwestern Pennsylvania and areas bordering West Virginia were known for their ample foliage and floral decorations—tulips, fuchsias, and, in Morgantown, ferns (figs. 42-44). The Uniontown pottery wares often display lavish trumpet flowers, a decoration not found among Morgantown’s wares.[21] The more sparse decoration seen on the jars illustrated in figures 45 and 46 are attributed to Frank W. Thompson, who had returned to the business following the Civil War. Floral decoration on the stoneware continued well into the 1870s.

The transition to stoneware also included the introduction of a series of whimsical images of people, animals, and birds. A small group of pots by the Thompson, Uniontown, and Greenland potters depicts roughly painted images of people surrounded by foliage or trees (figs. 47, 48). Many of these pots, affectionately referred to as “people pots,” also incorporate David Greenland Thompson’s roulettes, stamps, and impressed designs as well as the whimsical characters and animals.[22]

While many believe that “people pots” originated in the Uniontown area, we feel strongly that John W. Thompson introduced these depictions on pots in Morgantown. The pots with definite Morgantown characteristics can be closely dated to between 1854 and 1863, when Thompson died.[23] Norval Greenland of Uniontown did not begin his pottery factory until the early 1860s, and so must have been influenced by John W. Thompson’s designs. By 1865 the characteristic “people pots” of Uniontown seem to disappear also, and decorations gravitated toward floral designs. Similarities between the Uniontown, Greenland, and Morgantown pot decorations make it more difficult to distinguish where each pot was made.

Many of the Morgantown examples show objects in the hands of the subjects. A fine example of a small pitcher, 6 1/4 inches tall (fig. 49), has a rounded belly, sloping shoulder, high-collared rim with burgeoning spout, and a neatly tucked foot. Beneath the spout a man wearing a wide-brimmed hat carries a long rifle. A brilliantly detailed sun radiates from one side, with a duck or goose below its rays; on the opposite side stand three women. The arrangement of the scenes appears somewhat random but may have held special significance for Thompson. Rifles appear on several other pieces (fig. 50), including a comical statement between a man and a woman on the small jar illustrated in figure 51.

The figures seen on the wares attributed to the Morgantown Pottery are generally painted in great detail. Interestingly, the decorator chose to place well-defined noses on the men, whereas the women’s faces are usually featureless. Hats are placed on many of the men. The women are shown in flowing aprons and skirts, many also wearing bonnets and carrying parasols (figs. 52-54).

John W. Thompson is also credited with depicting a number of stylized animals, birds, and fish on his jars—for example a whale (fig. 55) and the stag on the enormous jar illustrated in figure 56—which are highly sought after by modern folk art collectors. Thompson’s painting style shows brushstrokes that are often very broad and very thick. These overlapping layers of cobalt can trace the evolution of the composition.

By 1870 David Greenland Thompson and his brother Frank were the only immediate members of the Thompson family listed as potting in Morgantown, with David living with Frank.[24] David reported having a “5 h.p. steam engine” (installed by James Jackson Thompson) using “415 cords of wood,” paying “$300 in wages,” and producing “$1900 of products” in nine months of operation.

Sometime after 1870, Frank began operation of a flour and gristmill on the same site as the pottery using the engine and discontinued work as a potter. The days of elaborately hand-decorated stoneware (fig. 57) were coming to an end in Morgantown. In 1875 David entered a three-year partnership with Robert T. Williams, who had finished an apprenticeship with Littel/Little and Company and with Hamilton and Jones of Greensboro, Pennsylvania.[25] One known example of this partnership shows Thompson’s willingness to employ stenciling in the cobalt decoration. Stenciled decoration would become de rigueur for the New Geneva Pottery, of which Robert T. Williams became proprietor in 1882.[26] Stencils became increasingly popular with potters as a way to produce and decorate their wares in a less costly, more efficient manner, an adjustment necessary to keep up with the rising competition of industrialized pottery production.[27]

Despite the industrialization of the process of making stoneware, David Thompson’s inventiveness still showed. Plate 7 of “An Early West Virginia Pottery” illustrates four pieces from circa 1870–1885 having applied clay that had been pressed in molds of pine and spruce cones, nuts, and simulated flowers and leaves. In a number of examples David Thompson used what Walter Hough later described as applied creativity with a natural approach to the form (figs. 58, 59). Hough noted that these forms, which he attributed to “Greenland Thompson,” were not sold but rather offered as gifts to people in the community; others were given to family members (fig. 60).[28]

The End of an Era

When David Greenland Thompson died, in 1890, the Morgantown Pottery ceased operation.[29] After approximately ninety years of operation, the Morgantown pottery did not see a diminishing interest in their wares, nor did the creativity of the pieces or attention to detail lessen with the owner’s advancing age. Yet surely it would have met the same destiny other stoneware pottery factories faced at the turn of the twentieth century. These factories, which typically employed five to thirty workers at a time, were little match for the industrial factories that were beginning to take over the stoneware market. Faced with the need to turn their entire factory of handmade pottery over to machines and molds, many potters could not afford to make the transition, having neither the space nor the workforce. Moreover, as railroads established new, faster transportation routes in the United States, the once-strategic location of these potteries—on the riverbanks—became obsolete.[30]

The history of the Morgantown Pottery transition from earthenware to stoneware is a unique, and important, example of a pottery rising to the challenge of imported stoneware in a local economy and grasping an opportunity for development in decoration and technique. The existence of the wares and tools used to make them is a rare glimpse into the history of ceramic manufacture in America.

The somewhat comical adventures of Jacob Foulk Jr. (Fouke, Folk, Fulk, Faulke) were first described in the 2004 article. Recent research conducted by Millie Covey Fry has revealed that Jacob Foulk moved from Morgantown to Brooke County, Virginia, where he appeared once more in the court records, as he often had in Morgantown. He appears in the 1820 census but presumably died shortly thereafter, since in 1821 his wife requested that the estate of her late husband be administered.

Don Horvath and Richard Duez, “The Potters and Pottery of Morgan’s Town, Virginia: The Earthenware Years, Circa 1796–1854,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), p. 111. The pottery moved to the wharf in 1830, after the pottery on Lot 88 had burned.

Walter Hough, “An Early West Virginia Pottery,” in Report of the National Museum (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899), p. 515.

Listed below are the only known Thompson wares bearing dates:

1854 “First 2 jar for Francis Madiera June the 2nd, 1854” (see figs. 2, 3)

1866 “JHT / BB / 1866” conical wax sealer (not illustrated)

1867 “Oct. the 8th 1867 Sarah E. Chew” milk bowl (not illustrated)

1869 “Thompson / Morgantown / 1869” preserve jar (see fig. 19)

1880 “1880 / 2” jar (not illustrated)

1885 “Rufus West / Oct 19th 1885” jar (not illustrated)

Monongalia Historical Society, Sesquicentennial of Monongalia County, West Virginia (Morgantown, W. Va.: Monongalia Historical Society, 1926).

Phil Schaltenbrand, Big Ware Turners (Bentleyville, Pa.: Westerwald Press, 2002), pp. 152–53. Schaltenbrand notes that even though the clay seam was recognized by 1810 as being usable for pottery, potters in this area continued to produce earthenware into the 1840s.

Professor J. C. White, “Evidence of a Great Ancient Glacial Lake in West Virginia,” in Jebediah Hotchkiss, The Virginias (Staunton, Va.: Jebediah Hotchkiss, 1883), p. 139. White described the seam of clay located across the river from Morgantown in Pennsylvania as having “thick deposits of very fine, bluish white clay.” These clays have been used extensively for the manufacture of pottery at Geneva and Greensboro, and to some extent Morgantown and Fairmont, West Virginia. White also referred to the “transported material” in Morgantown’s terraces of clay and soil, possibly inferring that Morgantown had a source of earthenware when they were producing such wares. A student of his, Walter Hough, assisted in the analysis of these clay seams and went on to become a curator at the Smithsonian and the author of “An Early West Virginia Pottery.”

He was reported to have worked for the Thompsons, but his endeavor in stoneware was short-lived. Hough, “An Early West Virginia Pottery,” p. 516.

Ibid., p. 514.

Ibid., p. 515.

Horvath and Duez, “The Potters and Pottery of Morgan’s Town, Virginia,” p. 120.

Phil Schaltenbrand, Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press), p. 76.

Ibid., p. 37.

Ibid., p. 76.

Ibid., pp. 76–78.

Hough, “An Early West Virginia Pottery,” pp. 515–16. Hough referred to Thompson simply as “Greenland Thompson,” a name used in several other references as well.

In most cases the handle molds are believed to have been made by impressing cast-iron hardware bin handles into a clay “master,” which was then fired to become an inverse form with which to shape the lugs.

An image of these extrusion dies is illustrated in Horvath and Duez, “The Potters and Pottery of Morgan’s Town, Virginia,” p. 120, fig. 51.

William Ketchum, American Stoneware (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1991), p. 4.

Schaltenbrand, Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania, pp. 120–21. Schaltenbrand also provides figures in Big Ware Turners, pp. 82–83, writing that the “Isaac Hewitt enterprise in Rices Landing . . . was paying 50 cents a pound for cobalt in the 1860s but annually needed only 50 lbs to decorate approximately 90,000 pots.” Although the cost of cobalt was rather high, it could be stretched or watered down to accommodate large production.

Schaltenbrand, Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania, p. 79.

The Uniontown pottery had at least three beaded gallon-capacity stamps. They can be seen on a 3-gallon jar with two figures painted on the front; a 5-gallon Uniontown floral jar with a redundant Roman “V”; and a 20-gallon jug.

Schaltenbrand, Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania, p. 79.

The census lists “2 males above 16 years,” “1 female above the age of 16 years,” and “3 lathes” (potters’ wheels). Other female potters are known. For example, the 1880 census for Nicholson Township, Greene County, Pennsylvania, lists Ann Mariah Sandusky as one of the New Geneva Pottery workers (the authors thank Michael Gallis for this information). The Philadelphia City Directory for 1798 includes “Margaret Freytag, potter” at the corner of South Fifth and Small Streets. For a discussion of the position of women in the pottery studio, see Schaltenbrand, Big Ware Turners, p. 70.

Gordon C. Baker, “Robert T. Williams, New Geneva, Pennsylvania Potter,” Spinning Wheel 34 (April 1978): 12–14.

Schaltenbrand, Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania, p. 89.

Ketchum, American Stoneware, pp. 6–7.

Hough, “An Early West Virginia Pottery,” p. 514.

Ibid., p. 517.

Schaltenbrand, Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania, pp. 159–60.