Drug jar, stoneware, Domfront, France, ca. 1613–1625. H. 1 3/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Recovered at site 44CC370, Charles City County, Virginia, in 2002.

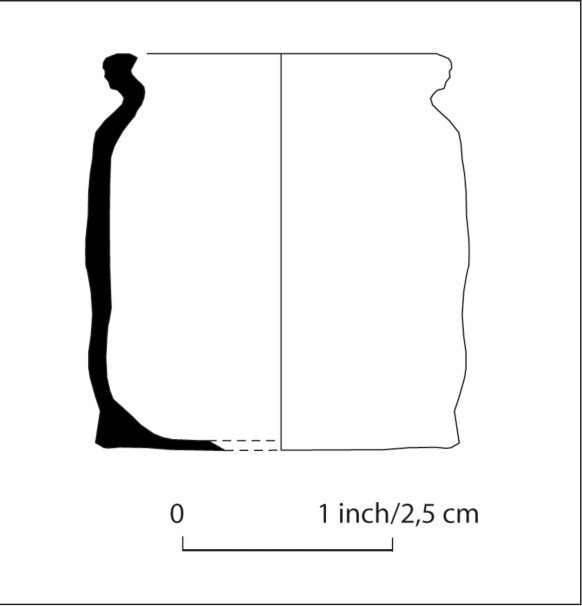

Profile illustration of the Domfront drug jar illustrated in fig. 1. (Illustration by Bruno Fajal and Taft Kiser.)

Virginia’s rarest archaeological sites are those dating to its first decades as an English colony. These early contexts can contain such exotic ceramics as Ming porcelain, Algonquin tobacco pipes, and Montelupo tin-glazed earthenware, but one of the most exceptional new discoveries is a small French-made ointment pot. From a circa 1613–1625 context at Shirley Plantation in Charles City County, the pot was made near Domfront, Normandy, Orne, and is the only piece of Normandy stoneware that has been found in Virginia (figs. 1, 2).[1]

In Normandy, distinctive stonewares were produced around Domfront (southwest Orne and southeast Manche), in west-southwest Bayeux (Calvados), in the north of the Cotentin (Manche), and in Martincamp-Bully, near Neuchâtel-en-Bray (Seine-Maritime). The Shirley vessel is a wide-mouthed cylindrical “drug jar” that probably held medicinal salve for people or livestock.[2] At Domfront this form was produced from the early postmedieval period until the early twentieth century, when the local stoneware industry, around Ger (Manche), fired its last kilns. Made of a kaolin-type clay known as Saint-Gilles-des-Marais, which becomes semivitrified at 1,250–1,300°C., the surface is gray when unglazed and the fired clay body is pale brown. This clay has been used by potters since at least the thirteenth century and is found exclusively in a limited area west of Domfront.[3]

French pottery is rare in seventeenth-century Virginia archaeological contexts; most common is the high-fired earthenware known as Martincamp, named for a village in Normandy.[4] Stoneware jars from Beauvais have been excavated from early contexts at Jamestown and a circa 1620–1635 context at Jordan’s Point in Prince George County. And although earthenware from Saintonge in southern France has not been recovered from Jamestown’s early contexts, a vessel of this ware has been found in a circa 1618–1630 context at Flowerdew Hundred, in Prince George County, and in post-1630 contexts at Henrico County’s Curles Plantation and the Walter Aston site in Charles City County.[5]

Elsewhere in North America, Normandy stoneware has been found on French sites in such contexts as circa 1562–1563 in South Carolina, the 1560s in Florida, and 1604–1763 in Canada and Maine.[6] It has not been found at Maine’s Fort Pentagoet, probably because the settlement relied on the more southern port of La Rochelle for supplies.[7]

The Domfront pot was excavated at the earliest known European structure on Shirley. In 1613 Virginia’s principal mariner, Samuel Argall, destroyed two settlements in French Arcadia, and the prizes he carried to Virginia included prisoners (who were transported to England in June 1614), food, clothing, horses, and tools.[8] The 1625 Muster lists eight people who were on Argall’s ship in 1613 and 1614; half of them were at Shirley or neighboring Jordan’s Point, where the two Beauvais jars were excavated. This suggests an alluring interpretation as Argall’s loot, but Virginians had frequent contact with French vessels in the northern fisheries and French workers were sent to the colony to establish vineyards and produce silk.[9]

Bruno Fajal, CNRS, CRAHAM-UMR 6273, University of Caen, 14032 Caen cedex, France

bruno.fajal@unicaen.fr

Taft Kiser, Cultural Resources, Inc., Richmond, Virginia

tkiser@culturalresources.net

Bruno Fajal, “Ger 1988: Rapport de fouille de sauvetage urgent,” unpublished report, Centre de Recherches Archéologiques Médiévales, Caen, 1988.

Stéphen Chauvet, La céramique Bas-Normande ancienne (Mortain [Manche]: Éditions du Mortainais, 1950).

Daniel Dufournier and Bruno Fajal, “L’apparition du grès dans la région domfrontaise, premières observations,” in La céramique du XIe au XVIe siècle en Normandie, Beauvaisis, Ile-de-France, Cahiers Techniques du GRHIS No. 2, edited by Xavier Delestre and Anne-Marie Flambard Héricher ([Mont-Saint-Aignan]: Publications de l’Université de Rouen, 1995), pp. 73–80; and Jean-Pierre Lautridou, “Les argiles fini-tertiaires de Saint-Gilles-des-Marais (Domfrontais, Orne),” Bulletin de la Société Linnéenne de Normandie 118 (2002): 39–41.

For an online overview of Martincamp flasks (the only form found in Virginia), go to www.preservationvirginia.org/rediscovery/page.php?page_id=321.

According to Jamestown Rediscovery curator Beverly Straube, no Saintonge earthenware has been found in Jamestown’s early contexts (personal communication, 2010); the vessel at Flowerdew Hundred was identified by the late John G. Hurst (personal communication, 1997).

Jean-Pierre Chrestien, Daniel Dufournier, Françoise Niellon, and Marcel Moussette, Le site de l’habitation de Champlain à Québec: Étude de la collection archéologique (1976–1980) (Quebec: Government of Quebec, 1987); David M. Brewer and Elizabeth Horvath, In Search of Lost Frenchmen: Archaeological Excavations at Canaveral NS (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2008), available online at www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/npsites/canaveral.htm (accessed December 20, 2010); and Jean-Pierre Chrestien and Daniel Dufournier, “French Stoneware in North-Eastern North America,” in Trade and Discovery: The Scientific Study of Artefacts from Post-Medieval Europe and Beyond, British Museum Occasional Paper 109, edited by Duncan R. Hook and David R. M. Gaimster (London: British Museum, 1995), pp. 91–103.

Alaric Faulkner and Gretchen Faulkner, The French at Pentagoet, 1635–1674: An Archaeological Portrait of the Acadian Frontier, Occasional Publications in Maine Archaeology No. 5 (Augusta: Maine Historic Preservation Commission, 1987), p. 211.

Dictionary of National Biography, edited by Sir Leslie Stephen, 63 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1885), 2:79.

Edward Wright Haile, ed., Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony, the First Decade, 1606–1617 (Champlain, Va.: RoundHouse, 1998), pp. 786–87, 824–26; Faulkner and Faulkner, The French at Pentagoet, p. 14; Martha W. McCartney, Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607–1635: A Biographical Dictionary (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007), pp. 56–57, 209, 213, 216–17, 377–78, 452, 618, 749–50; Adventurers of Purse and Person: Virginia, 1607–1624/5, edited by Virginia M. Meyer and John Frederick Dorman, 3rd ed. (Richmond: Order of the First Families of Virginia, 1607–1624/5, 1987), p. 29; and Susan Myra Kingsbury, ed., The Records of the Virginia Company of London, 4 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1906–1935), 1:466, 3:242–43.