Japanese towns and cities mentioned in the text.

Bowl, Japan, ca. 1870. Porcelain. D. 4 3/8". Blue fukizumi stencil design of cherry blossoms. (All objects courtesy of the author; unless otherwise noted, all photos by the author.)

Bowl, Japan, 1875–1920. Porcelain. D. 4 5/8". Blue katagami stencil design of cherry blossoms.

Pickle dish, Japan, 1890–1920. Porcelain. D. 5 15/16". Blue transfer-printed design of pine, plum, and bamboo in reserve panels with a central peony medallion. Panels are separated by diaper patterns of stylized fish roe, fish scales, waves, and the Seven Jewels motif.

Teacup, Japan, ca. 1890. Porcelain. D. 3". Blue and pink transfer-printed design of a plum tree.

Rice-bowl lid, Japan, ca. 1870. Porcelain. D. 3 15/16". Blue painted design of crossed bamboo stalks.

Bowl fragment, Japan, ca. 1875. Porcelain. D. 4 3/4". Blue and pink painted plum blossoms with resist accents.

Celadon teacup, Japan, late 19th–early 20th century. Porcelain. D. 3 1/8". Green glaze with kasuri-mon decoration.

Bowl, Japan, late 19th–early 20th century. Porcelain. D. 4 3/4". Splashes of brown wash on rim and flattened facets around lower body.

Bowl, Japan, ca. 1890. Porcelain. D. 4 11/16". Painted with blue and brown washes and incised lines around base.

Teapot-shoulder fragment, Japan, ca. 1885. Porcelain. D. 3 3/8". Blue painted floral designs around neck and sharkskin glaze on body.

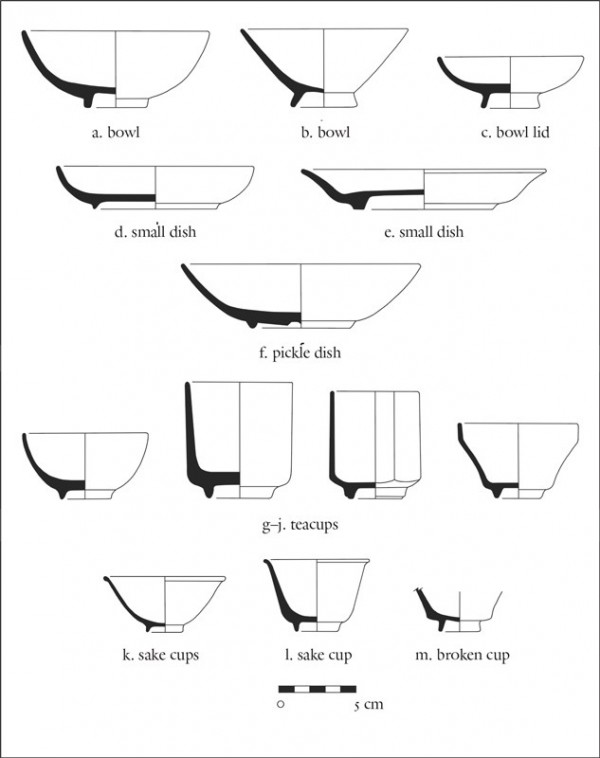

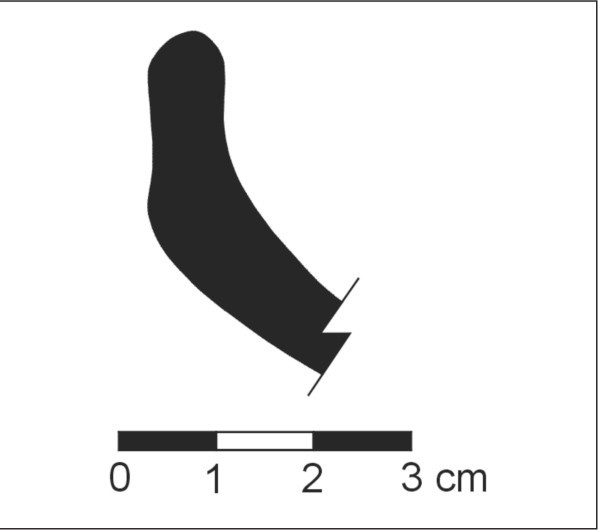

Profile drawings of Japanese ceramic tablewares from Don Island.

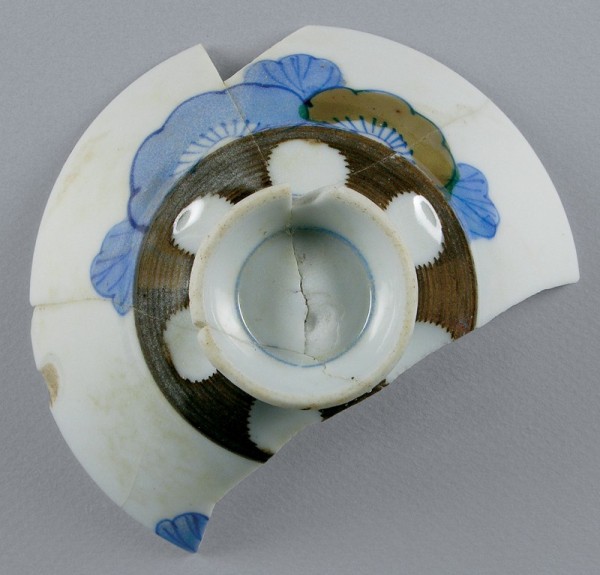

Reverse of the pickle dish illustrated in fig. 4, showing snake-eye base and blue printed plum blossoms around the rim.

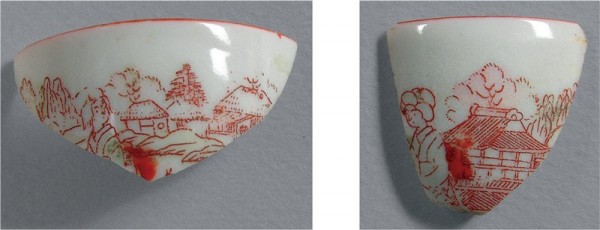

Eggcup fragments, Japan, ca. 1890. D. 1 3/4". Porcelain. Overglaze-red transfer-printed design in Geisha Girl pattern.

Sake bottle (tokkuri), Japan, ca. 1890. Porcelain. H. 6 11/16". (Courtesy, Asian American Comparative Collection, University of Idaho, AACC-98-53.)

Sake bottles (saka-bin) Japan, late 19th–early 20th century. Stoneware. H. (left) 11 1/4", (right) 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Asian American Comparative Collection, University of Idaho. AACC-94-82, CCC-82-8.)

Mortar bowl, Japan, late 19th–early 20th century, recovered from Don Island. Stoneware with combed interior. D. 14 3/16". See profile drawing in fig. 18.

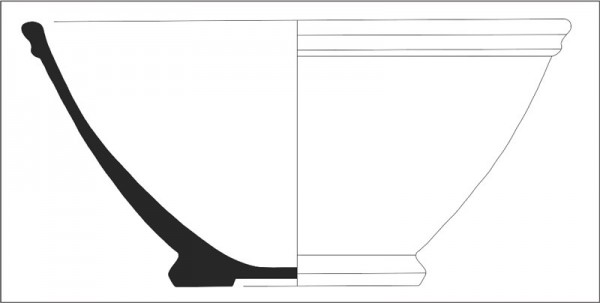

Profile drawing of the mortar bowl (suribachi) illustrated in fig. 17.

Teacup, Japan, late 19th–early 20th century. Earthenware. D. 2 3/4". Undecorated with clear glaze.

Teacup, Japan, late 19th–early 20th century. D. 2 3/8". Stoneware. Metallic oxide glaze and incised designs on lower body and base.

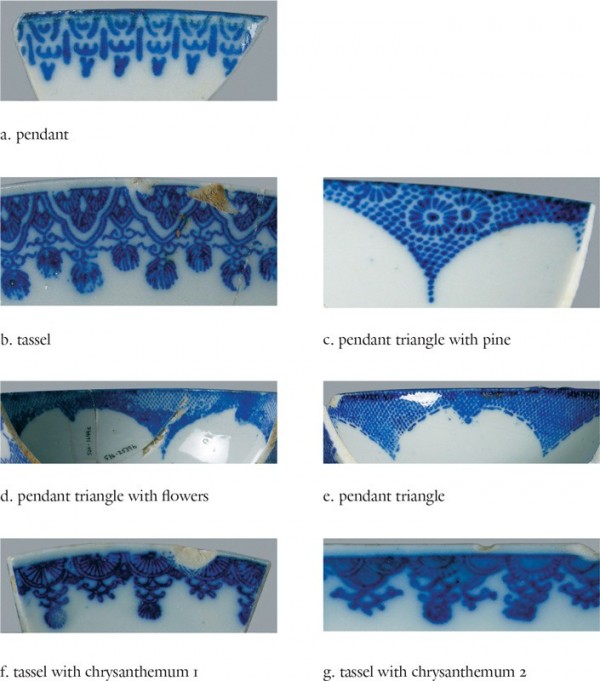

Rim fragment from ceramic frying pan (horoku). Earthenware. D. 14 3/16".

Profile drawing of the frying pan fragment illustrated in fig. 21.

Profile drawing of Japanese ceramic frying pan similar to the one illustrated in fig. 21. Redrawn from Wilson, The Archaeology of Edo, p. 35, no scale.

Small dish, Japan, ca. 1890. Porcelain. D. 5 1/2". Blue transfer-printed and painted designs of human figures, birds, several kinds of flowers, and geometric diaper pattern.

Teacup, Japan, ca. 1915. Porcelain. D. 2 3/4". Blue transfer-printed Phoenix Bird pattern.

Bowl, Japan, ca. 1915. Porcelain. D. 4 5/16". Blue transfer-printed Phoenix Bird pattern.

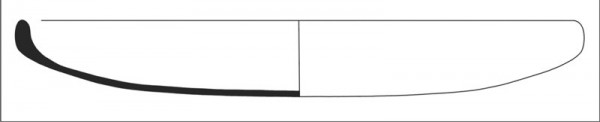

Bowl, Japan, ca. 1875. Porcelain. D. 4 15/16". Celadon bowl with polychrome painted floral design.

Bowl, Japan, ca. 1890. Porcelain. D. 4 3/4". Blue transfer-printed plum-tree design inside lightning-bolt reserve panel.

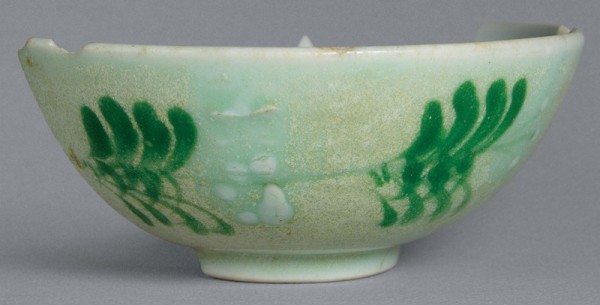

Common border designs on Japanese porcelain bowls.

Pickle dish, Japan, 1875–1920. Porcelain. D. 5 1/2". Blue stenciled decoration of pine, plum, and bamboo in central medallion. Alternate reserve panels contain clematis blossoms against diaper with Seven Jewels motif.

Pickle dish, Japan, ca. 1870. Porcelain. D. 5 1/2". Blue painted designs with resist pagoda and flowers in central medallion.

Teacup, Japan, ca. 1870. Porcelain. D. 3 3/16". Blue painted Tokugawa-period chrysanthemum design.

Bowl, Japan, 1875–1920. Porcelain. D. 4 5/16". Blue stenciled decoration with stylized karakusa and Three Philosophers motif in reserve panel.

Bowl, Japan, 1895–1920. Porcelain. D. 4 3/4". Blue stenciled military theme.

Marks on Japanese ceramics from Don and Lion Islands.

Unlike domestic Chinese ceramics recovered from late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century archaeological sites in North America, very little has been published on contemporary Japanese wares. Archaeologists, art historians, and collectors generally write about earlier periods in Japanese ceramic history; most of the remainder focus on folk pottery, export wares, and museum-quality pieces. However, a handful of archaeologists and collectors have begun to turn their attention to more recently manufactured porcelain vessels produced for domestic use in Japan, which are found in large quantities at Japanese sites in North America and elsewhere. Recent excavation of a large group of Japanese domestic porcelain from an early-twentieth-century fishing camp on tiny Don Island, along the Fraser River in British Columbia, provides an opportunity to synthesize and refine existing knowledge of the production, design, marketing, and use of these too rarely studied wares.

The site, located about twelve miles (20 kilometers) southeast of downtown Vancouver, is associated with an industrial salmon cannery (the Ewen Cannery, 1885–1930) and was founded in 1901 by Japanese entrepreneur Jinsaburo Oikawa. At its peak, the community comprised seventy to one hundred Japanese bachelors and families, but dispersed shortly after the cannery closed in 1930. Excavations were conducted in 2005 and 2006 as part of a research project comparing the domestic material lives of Japanese community members on Don Island with residents of the Chinese bunkhouse located adjacent to the canning complex on neighboring Lion Island.[1]

Japanese Porcelain in the Tokugawa Period

Japanese porcelain production began at Arita in Saga prefecture (formerly Hizen province) at the outset of the seventeenth century (fig. 1).[2] Known as “Imari,” domestic porcelain was largely hand painted—often adapting Chinese techniques and motifs—in underglaze cobalt blue (sometsuke), although green celadon glazes and such overglaze enameled colors as red, green, and black were also used. Imari porcelain reached Europe via Portuguese and Dutch merchants, but trade declined in the mid-eighteenth century, when cheap Chinese alternatives lured European traders away from Japan.[3] Arita was the focal point of porcelain production until the early nineteenth century, when it spread to other parts of the country with suitable clay deposits, each potting center lending its name to particular wares.[4] Initially, porcelain was used exclusively by the ruling elite, but archaeological evidence indicates that by the late eighteenth century the general population of Edo (Tokyo) had begun to prefer it to earthenware and stoneware. Porcelain production for general consumption began circa 1820–1830. These porcelain wares increased in popularity as they became more available and affordable as manufacturing expanded.[5]

Impact of the Meiji Restoration

Many technological and decorative features of porcelain vessels from Don Island were introduced during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Since the 1630s, the previous Tokugawa shogunate had forbidden most Japanese from traveling abroad and excluded all foreigners except a small number of traders received at strategically located peripheral ports. In 1868 political instability, linked to the forced opening of trade relations with the United States and Europe in the 1850s, led to the deposition of the shogun, a return to imperial rule, and a move toward representative government. During its isolation, Japan had fallen behind Western nations technologically and economically, and modernization in emulation of them was promoted as a way to strengthen the foundations of the new government and make Japan competitive in the global marketplace. To foster industrialization, Meiji leaders sent students abroad and brought to Japan foreign specialists in various fields of science and technology.

Among the developments were innovations in glaze and pigment technologies; introduction of machinery used in clay preparation; methods of slip casting; coal-fired kilns; and new decorating techniques (table 1). German chemist Gottfried Wagener was instrumental in developing the science of clays and glazes in Japan, but one of his most significant achievements was replacing natural cobalt (gosu) with chemically produced cobalt oxide imported from Europe and America, which had a brighter and more intense color than the gray-blue gosu. Most changes served the Japanese government’s interest in promoting mass production and standardization of ceramics as a means to fuel international demand for cheap export ceramics. After Japan opened to foreign trade in the 1850s, companies began in earnest to mass-produce and export decorative vessels and Western-style tableware decorated in combinations of Asian and Western art styles.[6] Alongside technological innovation was reorganization of production. During the Tokugawa period, most ceramics were produced in small workshops operated by families or masters and apprentices. In the Meiji period, rural workshops were increasingly replaced by large urban companies that employed more than a hundred workers and mass-produced cheaper wares using an assembly-line approach that included reference to standardized pattern books. Driven by the export economy, such developments also affected production for the domestic market, although traditional domestic wares continued to be produced.[7]

Porcelain Decoration during the Meiji Period

STENCIL WARES

Although there was continuity between the Tokugawa and Meiji periods in porcelain decoration, producers were keen to adopt techniques such as printing (inban) to facilitate mass production and reduce costs. One printing method was stenciling (surie), in which paper stencils were placed over the vessel to guide application of decoration. There were two primary types of stenciling, fukizumi and katagami (figs. 2, 3). Fukizumi is a negative, or masking, method in which paper stencils are held against a vessel to block pigment; the pigment is sprayed or spattered around the perimeter, creating a characteristic speckled outline. Katagami employs a positive stencil, with pigment allowed to pass through holes in the paper. Both methods were used in the seventeenth century but were largely abandoned by the end of the eighteenth century.[8]

Stenciling was reinvented in Hizen province in the early 1870s but was quickly adopted in Tobe, from where it was passed on to Mino province (part of modern Gifu prefecture) between 1878 and 1882 and then to other porcelain centers across Japan.[9] The dominant method was katagami, although fukizumi decoration has been found at sites in North America, including Don Island (table 2). Unique characteristics of the application process make katagami designs easily distinguishable from hand-painted and transfer-printed wares. In order for the stencil paper to hold together, patterns must be created using a series of dots, short parallel lines, or dashed outlines, and multiple stencils are often required for a single vessel.[10] Unlike most Tokugawa examples, many late-nineteenth-century vessels exhibit evidence of careless application of stencils, including smeared pigment, overlapping designs, and unevenly applied color. In fact, all decorative styles from Don Island are variable in terms of the care and skill with which decoration was applied, suggesting that most were cheap, mass-produced wares.

TRANSFER-PRINTED WARES

The other printing method used widely in Japan in the Meiji period was transfer printing (doban or doban tensha). It was invented in England in the mid-eighteenth century and was first applied to porcelain by 1760.[11] Dutch traders brought English and Dutch transfer-printed wares to Japan in the late Tokugawa period, but attempts to copy them were unsuccessful.[12] It was not until 1888 that potters in the city of Tajimi learned how to make copperplates from workers in the textile dyeing trade in the nearby city of Nagoya, and the next year they patented a method for printing ceramics. Shortly thereafter, transfer printing spread to other major ceramic centers in Japan, including Arita and Tobe. By the Taisho period (1912–1926), this technique had eclipsed stenciling on mass-produced domestic porcelain, and by circa 1920, katagami had disappeared from the market. Most underglaze stencil- and transfer-printed designs on Japanese porcelain were executed in blue because of the difficulty in developing other colors that could withstand the high firing temperature required for vitreous wares (fig. 4). Japanese potters were able to overcome this limitation in the 1870s and 1880s, and later transfer wares included underglaze green, pink, black, yellow, and brown (fig. 5).[13]

OTHER DECORATION METHODS

Stenciling, transfer printing, and hand painting (fig. 6) are the most common decorative techniques found on Japanese ceramics recovered from North American sites, and transfer printing and painting commonly occur together. Other techniques found on porcelain vessels from Don Island include resist and kasuri-mon, along with molding, incising, colored glazing, and blue and brown washes (figs. 7-11). Resist methods were used from the early Tokugawa period and involve painting designs on a vessel in India ink, over which a wash of cobalt blue is applied.[14] When the porcelain is fired, the carbon oxidizes and removes most of the overlying cobalt, leaving white lines in its place. These lines serve to outline drawings, add texture to flowing water, create veins in foliage, and produce geometric designs on a dark background. Resist designs occur in the Don Island assemblage in conjunction with hand painting and transfer printing.

Kasuri-mon, or chatter decoration, dates back to the Song dynasty (960–1279) in China and is typically found on nonvitreous pottery. The process begins by coating a vessel with white (or other colored) slip when leather hard and allowing it to dry. The vessel is then placed on a potter’s wheel, and, as it turns, a flexible trimming tool (kanna) is allowed to skip across the surface, removing small gouges from the slip with each touch. The speed of the wheel affects the size of and distance between marks.[15] This pattern is present on Japanese celadon (seiji) teacups recovered from Don Island, although no slip was used in those cases because the brilliant white of the porcelain body provided adequate contrast with the green glaze.

Other decorative techniques are less common on Don Island. Blue and brown washes are thin, translucent pigments applied to a vessel by dipping or brushing and occur as regular bands, irregular splotches, or fill for objects outlined by painting or printing. One partial teapot rim has blue painted floral decoration around the collar but beige sharkskin-textured glaze on the body. According to Leland Bibb, vessels with this decoration were manufactured in Aizu-Hongo in Fukushima prefecture and were first exported to America in 1885, although the sharkskin-type glaze is known to have been produced at a number of kilns during the Meiji period.[16]

Vessel Forms and Classification Schemes

Japanese ceramics are produced in a range of shapes and sizes for specific functions.[17] Vessel nomenclature is variable, and there exists no generally accepted classification scheme for late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century tableware. Julia Costello and Mary Maniery’s preliminary study of Chinese and Japanese ceramics from Walnut Grove, California, employed a system based on shape, size, and function that has been adopted by other researchers.[18] Bibb has developed a similar nomenclature, drawing more systematically from the Japanese-language literature for naming conventions, an approach I adopt here (table 3).[19]

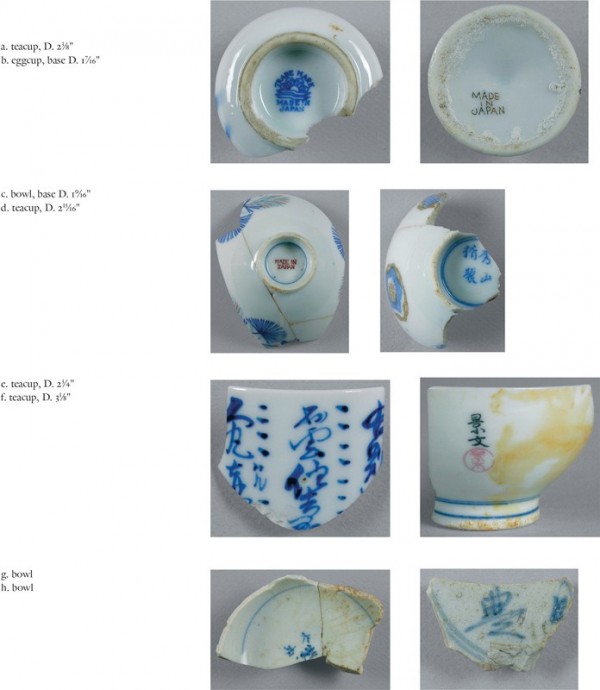

Japanese on Don Island used a limited number of vessel types; other North American sites have produced additional forms but still fall far short of the range of tablewares available in contemporary Japan. Nevertheless, this simplified assemblage corresponds closely with the traditional daily meal of rice, miso soup, and side dishes of pickled vegetables, along with tea and sake. By far the most common vessel form from Don Island is a bowl 4–4 3/4 inches in diameter used interchangeably for rice and soup, sometimes with a dish-shaped lid (fig. 12, table 4). Next is a shallow, round dish 4 3/4–6 1/4 inches in diameter with two major variants, used for side dishes. The first variant is generally referred to as kozara (small dish), and the second as namasu zara (pickle dish); the latter is deeper, with a scalloped rim and a circular recess on the base known as janome (snake-eye or bull’s-eye) (fig. 13). Teacups are similar in shape to rice/soup bowls but are smaller in rim diameter (2 3/8–4 inches) and come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Similar to teacups are sake cups, which are shallower with thinner walls and everted rims. Two types of teapots common in Japan are the dobin, with a detachable looped handle, fragments of which were found on Don Island, and the smaller kyusu, with a rod-type handle projecting from the body.[20] Fragments of two eggcups are export-style wares intended for the North American market (fig. 14).

Additional forms have been recovered on other sites, including larger bowls, dishes, and plates or platters that may have functioned as serving wares, along with porcelain and stoneware sake bottles known as tokkuri and saka-bin. Tokkuri are cylindrical or bulbous bottles (decanters) of stoneware or porcelain with slender necks and flaring rims; some of these bottles have faceted or fluted sides (fig. 15). Marks and decoration include transfer printing, calligraphy, incising, or paper labels, often indicating names of brewers, retailers, or consumers. Saka-bin are cylindrical stoneware containers similar to Euro-American glass beverage bottles, with a bluish white or bluish gray exterior glaze and with similar maker’s marks (fig. 16).[21]

Nonporcelain Japanese Ceramics

Nonporcelain Japanese vessels from Don Island include stoneware suribachi (mortar bowls), with incised parallel grooves on the interior for grinding ingredients like miso and sesame seeds into a paste using a wooden pestle (surikogi) (figs. 17, 18).[22] The body is typically buff or cream colored with an opaque brown glaze on the exterior and sometimes a brown slip on the interior. Two nonporcelain teacups were also recovered, one a dark gray stoneware, the other a buff-colored earthenware (figs. 19, 20), along with a fragment of a red earthenware horoku (saucepan/frying pan), used to parch beans and roast sesame seeds and tea (figs. 21-23).[23]

Ceramic Body

Porcelain is typically characterized as having a thin, white, translucent body with little or no porosity, fired at high temperatures (1300–1450°C).[24] Much of the Japanese tableware recovered from Don Island conforms to these characteristics; however, approximately 20 percent of the sherds are opaque and range in color from white to pale gray. Some scholars refer to these wares as “porcelaneous stoneware,” but this term masks the visual continuum between opaque and translucent vessels and implies a starker distinction than exists in reality. It also implies potters intended to produce a stoneware body rather than a porcelain one. Hazel Gorham argues that Japanese do not define porcelain by (or value it for) its thinness and translucency, and they term porcelain what Westerners would call only semiporcelain.[25] According to Oliver Impey, “If [the standard] definition [of porcelain] was to be applied strictly, then many oriental porcelains, including most of the Japanese wares, having a grey, opaque body, would have to be eliminated from the class; it is clear that we are talking not of a definition so much as of a guide-line.”[26]

In general, porcelains are made from a white-firing kaolin (or similar residual) clay combined with silica and feldspar, which tends to be nonplastic, and vessels are often cast in molds or formed using a jigger. To increase plasticity and make porcelain clays suitable for wheel throwing, the addition of sedimentary ball clay in sufficient quantities can turn the final product cream colored or gray and reduce its translucency due to the presence of impurities like iron oxide.[27] During the Tokugawa and early Meiji periods, porcelains were typically hand thrown on a wheel, and it was not until later that casting in plaster (gypsum) molds (early 1870s) and jiggering (circa 1915) were introduced to Japan.[28] It is possible the opaque gray cast present in Tokugawa and Meiji porcelain derives from attempts to make clays suitable for wheel throwing, and that less ball clay was required once casting and jiggering were widespread. Furthermore, a desire to make high-quality translucent porcelain for the Western market was an important incentive in the development of finer wares during the Meiji period.[29] It is also possible that the porcelain clay was improperly processed prior to forming: incomplete levigation (water sorting) may leave mineral inclusions behind, affecting firing properties.[30] Air pockets in the body of many opaque sherds suggest the clay was insufficiently kneaded, indicating that at least one of the processing stages was inadequately performed. It is likely, then, that the opacity and off-white coloring of some of the Don Island tableware is related to contingencies of the porcelain production process and a lack of concern for translucency rather than a conscious attempt to create a stoneware-like body.

Many opaque sherds from Don Island are associated with the thickly potted, hastily decorated, stencilware vessels. Because stencil decoration predates development of transfer printing in the Meiji period, it seems possible these opaque vessels are a legacy of early attempts to introduce cheap mass-produced porcelain tableware in the years before casting and jiggering became widespread, and that some companies continued to make such inferior products for a time after superior methods were introduced elsewhere. These low-quality wares constitute much of the stencilware output along with some of the early transfer wares. Takehisa Yamada notes that the widespread development of high-quality hard porcelains for the export market occurred over the first two decades of the twentieth century, and the proportion of opaque vessels in the Don Island assemblage probably reflects that transition.[31]

Design Elements and Motifs

Japanese assemblages are characterized by a wide variety of design configurations that do not necessarily recur at contemporary sites or persist over time. Such diversity makes these wares challenging to classify and interpret on stylistic grounds. Nevertheless, a number of core motifs and stylistic themes and conventions do commonly recur (albeit in unique combinations), and, rather than identify each unique combination as its own type, it is more practical to classify designs thematically. Tableware was not marketed in matching sets, and no two vessel forms in the Don Island assemblage have the same decorative pattern.

DESIGN STRUCTURE

Ceramic tablewares were decorated with reference to a series of horizontal spatial divisions on the interior and exterior of a vessel. Imari wares were initially based on Chinese prototypes, and vessel decoration was divided into five sections, following the Chinese style: one motif in the center of the upper/interior surface, a second around the center, a third around the interior rim, a fourth on the underside/exterior, and a fifth on the foot ring.[32] The central motifs were Chinese or Japanese in style, with repetitive floral motifs around the center and on other parts of the vessel. Many mass-produced Meiji porcelains maintained this structure, some entirely covered with intricate patterns on the interior or exterior. In some cases, there are four distinct motifs on the interior surface and/or an additional one just above the foot ring on the exterior. For this discussion, interior divisions will be referred to as the rim, cavetto, perimeter, and center, and exterior divisions as the rim, body, heel, and foot.[33] Hollow ware vessels with a neck or collar may have distinct decoration on this portion, and the lip of a vessel may also contain a ring of color. On the interior of shallow dishes, a single motif often covers both the rim and cavetto, and it is possible for single motifs to cover the entire interior or exterior of a vessel, or for horizontal spatial divisions to be subdivided vertically into ribbons or panels. Each division may contain structural elements (such as lines) or design elements. Technological considerations affect the nature of porcelain decoration. For example, stencil- and transfer-printing techniques facilitated detailed repetitive designs across an entire vessel, although the physical limitations of paper stencils precluded the fine detail and shading possible with transfers.[34]

DESIGN CONTENT

A number of scholars have identified common themes and motifs found on Japanese porcelain.[35] Many are inspired by Tokugawa-period porcelains and other decorative arts from previous centuries, while some are linked to the new government’s focus on technological development and military expansion and conquest. Multiple kinds of motifs can be found on a single vessel, complicating a straightforward classification scheme, and porcelain vessels can be classified in any number of ways according to the needs of the investigator (fig. 24).

For this study, design was explored by classifying vessels according to thematic content, and then subdividing them by specific elements or motifs for interpretation. Where multiple motifs are present, vessels were grouped according to the dominant motif, generally occurring on the cavetto of dishes and the exterior body of bowls and cups. Thematic categories used here are plants and animals, geometric patterns, human figures and domestic scenes, military and patriotic symbols, household objects, landscapes, mythology and religion, written characters, and abstract decoration (table 5). Meiji porcelain was decorated in a seemingly limitless variety of designs, and these themes will not cover such diversity, which includes numerous dominant motifs that crosscut categories.[36] Curiously, the Don Island assemblage contains only one example of a military theme and none bearing images of Western technology, such as the ships, clocks, trains, factories, and airplanes that appear on published specimens.

Although indigenous themes and styles are common, many design motifs on Japanese porcelain have their origin in Chinese culture, religion, and mythology, which have been influential in the development of Japanese art for centuries. In the Tokugawa period, publication of Chinese and Japanese manuals for depicting objects such as trees, flowers, birds, rocks, and mountains contributed to what Merrily Baird refers to as a “standardized design lexicon.” Images once associated with elites became available to members of lower classes and vice versa, and this democratization of design led to a proliferation of motifs on all manner of daily consumer goods. With the fall of feudal society at the end of the Tokugawa period, even heraldic crests (mon) of important lineages, including the imperial family, became widely adopted and copied. During the Meiji period, art was strongly influenced by the move toward Westernization but was also affected by a reaction to this process in the 1880s that emphasized a rediscovery of traditional culture.[37]

Two popular decorative patterns in the Meiji and Taisho periods that appear on export wares and have garnered attention in the collectors’ literature are known as Phoenix Bird and Geisha Girl. The blue transfer-printed Phoenix Bird pattern occurs on a wide range of Western-style vessels, but in the Don Island assemblage occurs only on handleless teacups and rice bowls (figs. 25, 26). The principal components of the design are a mythological bird known in Japan as the ho-o (similar in appearance to a phoenix), combined with a background of karakusa (scrolling vines, also known as Chinese grass) interspersed with chrysanthemum and/or paulownia blossoms. The phoenix, paulownia, and chrysanthemum were traditionally associated with the imperial family. The earliest known reference is from a 1914 catalog of A. A. Vantine & Co. in New York City, and the design was likely introduced to North America around this date.[38] Geisha Girl is a pattern developed in Kutani in the 1890s and also occurs on a wide range of Western-style vessels.[39] It typically depicts women dressed in kimono (not necessarily geisha) in domestic or landscape scenes from premodern Japan and may include men and children, pagodas, and various flowers, trees, and animals. Decoration is executed in overglaze-red transfer printing, combined with borders and motifs filled in with hand-painted decoration in red, cobalt blue (underglaze), maroon, green, yellow, and gold. These wares were available through department stores or oriental shops and may occur in traditional Japanese forms, although the only vessel with this pattern recovered from Don Island was a Western-style eggcup (see fig. 14).

Another familiar decorative type found on Don Island and other Japanese sites is seiji (Japanese celadon), an allover green glaze introduced to Japan from China and appearing on seventeenth-century porcelains.[40] Chinese celadon wares are common at nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Chinese sites in North America and are typically pale bluish green with blue painted characters on the base. Japanese wares tend to be a brighter green with a glossier surface, often painted in polychrome enamels (fig. 27). Most of the Don Island examples also have kasuri-mon decoration on the exterior (see fig. 8).

Including all stenciled, printed, and painted designs on Japanese tableware vessels from Don Island, there are 110 distinct patterns, the vast majority having plants and trees as the dominant motif, with a handful of species occurring most often: plum, cherry, chrysanthemum, peony, pine, and bamboo (table 6). These species have traditionally meaningful associations with seasons or auspicious concepts like longevity and occur alone against a white or patterned background or in combination with animals or other plants, sometimes as part of a landscape. Many motifs are highly stylized, and it is often difficult to distinguish particular plants. Dominant motifs may also appear in reserve panels highlighted against or separated by one or more diaper patterns. Reserves may be vertical segments of the body or floating panels, which sometimes take the form of such objects as fans or lightning bolts (see figs. 4, 28).

Many of these same plant species also appear in border and diaper patterns on rims and bodies and in central medallions. They are accompanied by common repetitive motifs, such as swastikas, stylized waves and hemp leaves, karakusa, interlocking circles (the Seven Jewels motif), fish roe, clouds, and geometric shapes, including squares, diamonds, triangles, and parallel lines (see fig. 4). Single or paired lines or border designs often demarcate divisions between parts of a vessel, such as the border between the cavetto and central medallion.

Pendant- or necklace-like border designs commonly occurring on the interior or exterior rims of bowls and cups are known as yoraku, of which there are several variants (fig. 29).[41] Structurally, the triangular variants in figures 29c–e actually serve as background for large white cherry blossoms that cover most of the interior of each bowl. Central medallions occur frequently on the interior of stenciled and transfer-printed vessels, and the most common by far are variants of the Chinese-inspired combination of pine, plum, and bamboo known as Three Friends in Winter. Other central motifs include a peony blossom, a sun, and the crane and turtle pairing (see figs. 4, 30). One particularly interesting example is a painted pickle dish with a sloppy blue ring in the center, under which flowers, a pagoda, and what looks like running water were drawn in resist ink (fig. 31).

Many design elements, motifs, and themes are inspired by or imitations of Tokugawa-period porcelain. This may reflect continuity in personnel, direct copying from known vessels, or patterns derived from design books. One painted teacup from Don Island with an allover chrysanthemum design is the virtual twin of a style popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, although the execution is sloppier (fig. 32).[42] Another motif used repeatedly on Tokugawa porcelains is the pattern of scrolling vines symbolizing continuity, known as karakusa and often referred to as “arabesques.”[43] It was adopted from China and often contains flowers nestled among the vines, sometimes identifiable (for example, peony and paulownia), other times more generic (see figs. 25, 26). On Meiji printed wares, this design was often simplified such that the vines and flowers are little more than swirls and dashes (fig. 33). One pattern clearly of Meiji origin is the military-themed stencil design on rice bowls recovered from Don Island that may commemorate the Sino-Japanese (1894–1895) or Russo-Japanese (1904–1905) wars (fig. 34). Although Bibb contends the majority of ceramics exported to North America probably were, with few exceptions, manufactured in and around Nagoya, it is not yet possible to link particular design patterns to production centers with any certainty.[44]

Marks and Dating

MAKERS’ MARKS

Marks on domestic Japanese porcelain are irregular in appearance, often ambiguous in meaning, and rarely provide valuable dating information. Marks can be in Japanese or English and convey a variety of information, including country of origin, name of manufacturer, decorator, retailer, location of manufacture, or a simple phrase such as “good luck.” In some cases, this information can provide researchers with useful data on forms or design patterns produced in particular regions or at specific kilns.[45] However, no systematic documentation linking makers and production centers with their marks has been published, and so most marks that have only partial details are untraceable.

Collectors have compiled images of marks found on export wares (which are far more common), but few of these are seen on Japanese domestic ceramics from archaeological sites.[46] One exception is variations of “Made in Japan,” which appear on both domestic and export wares, alone or with a graphic emblem. Unfortunately, no one has linked these wares with particular producers or demonstrated chronological sensitivity. The McKinley Tariff Act ratified by the United States in 1891 required all imports be marked in English with the country of origin, and Japan complied by marking its wares with “Nippon,” a romanization of the country’s Japanese name. In 1921 the U.S. declared “Nippon” inadequate and required imports be marked with the English word “Japan.” I have found no evidence Canada enacted similar requirements, although Joan Van Patten cites a U.S. regulation from 1892 exempting goods for immediate transport to Mexico or Canada from the law. Some researchers claim the 1921 date represents a terminus post quem for “Made in Japan” appearing in America; others have reported this mark in contexts predating 1921 and note that some companies found legal loopholes allowing certain imports to go unmarked.[47]

Of the Japanese tableware vessels recovered from Don Island, twenty contain makers’ marks, nine of which include “Made in Japan.” Of these, seven (six rice bowls and one teacup) are accompanied by a transfer-printed emblem of a chrysanthemum on water (kikusui) (fig. 35a), originally the family crest of a fourteenth-century emperor’s powerful general. It also occurs on Japanese ceramics from other North American sites.[48] The remaining marks are hand-painted in Japanese characters (table 7, fig. 6), but as yet very little information can be derived from them.

DATING AND OTHER ASSEMBLAGES

Reasonably tight dates exist for the introduction of stencil- and transfer-printed wares; unfortunately, they generally fall before the earliest Japanese sites in North America, and little dating information is yet available for makers’ marks and decorative styles. As a result, it is difficult to date sites from Japanese ceramics alone. Although too small for statistical comparisons, other assemblages support the absence of stencil wares at sites that postdate circa 1920, along with a decrease in surface area covered by decoration and an increase in the proportion of painted wares and those with multiple colors.[49] Don Island straddles this date and thus has stencil and transfer designs that cover the entire exterior or interior, as well as transfer- and hand-painted vessels with sparser decoration more akin to examples from later sites. The absence of opaque porcelains seems to be another indicator that a site postdates the mid-1910s.

Simplified decoration on domestic wares may be linked with inflation in Japan during World War I, followed by a severe economic depression in the 1920s merging into the global depression at the end of the decade.[50] During this time, Japanese goods were overpriced in the world marketplace and regularly passed over in favor of cheaper Chinese products. As a solution, the government encouraged lowering of domestic prices, and it is probable ceramic producers reduced the amount of pigment on cheaper wares to make them more competitive at home and abroad.

Conclusions

The large assemblage of Japanese ceramics from Don Island reflects a consumption pattern focused primarily on cheap, mass-produced porcelain tableware in a limited number of forms. Designs vary widely in style and quality of execution and include techniques and motifs rooted in Chinese and Japanese tradition and reflect the impact of technological, political, and aesthetic changes arising during the Meiji period. The color palette is dominated by cobalt blue, covering most of the surface on stencil and many transfer wares, but applied more sparingly on other transfer and painted vessels. This trend is likely rooted in technological limitations and economic considerations during the period of the site’s occupation. Unlike Chinese ceramics found at contemporary sites, designs are highly variable and include innumerable combinations of elements and motifs, although plants and animals predominate on Don Island. This may be the result of choice or availability.

While there is much work still to do, enough is known of the history, technology, uses, and meanings associated with Japanese domestic wares found at North American sites to offer valuable interpretive potential. One avenue in need of further study is relative prices of particular decorative styles, akin to what Ruth Sando and David Felton have uncovered for Chinese ceramics.[51] Although overall quality suggests that Don Island residents selected from among the cheapest wares available, specimens exhibit considerable variability in detail and execution, raising the possibility of an economic hierarchy of ceramic styles. Further examination of sites occupied over a short time by historically documented populations would help disentangle economic from chronological factors. Ultimately, research is just beginning and the most rewarding discoveries certainly lie ahead.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following individuals and institutions contributed immensely to this paper by providing access to research data and collections, sharing skills and expertise, or offering critical commentary on the text. They are Leland Bibb, Stan Fukawa, C. T. Keally, Timothy Savage and the Japanese Canadian National Museum, Priscilla Wegars and the Asian American Comparative Collection, and Richard Wilson. This research was supported in part by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Doctoral Fellowship.

Douglas E. Ross, “Material Life and Socio-Cultural Transformation among Asian Transmigrants at a Fraser River Salmon Cannery” (Ph.D. diss., Simon Fraser University, 2009).

Oliver Impey, The Early Porcelain Kilns of Japan: Arita in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996), pp. 1–2.

Oliver Impey, Japanese Export Porcelain: Catalogue of the Collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (Amsterdam: Hotei, 2002), pp. 14–16; Nancy Schiffer, Japanese Porcelain, 1800–1950 (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1999), pp. 22–24.

Gisela Jahn, Meiji Ceramics: The Art of Japanese Export Porcelain and Satsuma Ware, 1868–1912 (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2004), pp. 84–87.

Schiffer, Japanese Porcelain, p. 25; Jahn, Meiji Ceramics, pp. 186, 301; Richard L. Wilson, ed., The Archaeology of Edo, Premodern Tokyo, Working Papers in Japan Studies 7 (Tokyo: Japan Studies Program and Archaeology Research Center, International Christian University, [1997]), pp. 3, 27.

Jahn, Meiji Ceramics, pp. 108–14.

Ibid., pp. 33–35, 301.

Leland E. Bibb, “Japanese Stencilwares of the Meiji and Taisho Eras,” Asian American Comparative Collection Newsletter (Laboratory of Anthropology, University of Idaho) 18 (2001): 5–6; Tajimi (The City of Tajimi, Japan), “Mino-yaki no Inban—Suri-e—Doban Inban” [Mino’s engraved wares: Stencil and transfer printed], Mino-yaki Tajimi Newsletter 2 (1997); Irene Finch, “Printing and Resist Methods on Japanese Porcelains,” Arts of Asia (Kowloon, Hong Kong) 31, no. 2 (2001): 66–78.

Tajimi, “Mino-yaki no Inban,” p. 5; Hiroko Nishida and Koji Ohashi, “KoImari” [Old Imari ware], Taiyo / The Sun (Tokyo) 63 (1988): 41.

Bibb, “Japanese Stencilwares”; Finch, “Printing and Resist Methods,” pp. 73–74.

Teresita Majewski and Michael J. O’Brien, “The Use and Misuse of Nineteenth-Century English and American Ceramics in Archaeological Analysis,” in Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, Volume 11, edited by Michael B. Schiffer (San Diego, Calif.: Academic, 1987), pp. 141–42.

Tajimi, “Mino-yaki no Inban,” pp. 5–6.

Majewski and O’Brien, “Use and Misuse of Nineteenth-Century English and American Ceramics,” pp. 142–43; Jahn, Meiji Ceramics, pp. 83, 122.

Finch, “Printing and Resist Methods,” p. 66.

Herbert H. Sanders, The World of Japanese Ceramics (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1967), p. 178.

Leland E. Bibb, “Japanese Ceramics from the Home Avenue Dump, San Diego, California” (unpublished ms. in possession of the author 1997, corrected and rev. 2006); Louise Allison Cort, Shigaraki, Potters’ Valley (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1979), pp. 251–52.

Richard L. Wilson, Inside Japanese Ceramics: A Primer of Materials, Techniques, and Traditions (New York: Weatherhill, 1995), pp. 17–19.

Julia G. Costello and Mary L. Maniery, Rice Bowls in the Delta: Artifacts Recovered from the 1915 Asian Community of Walnut Grove, California, Occasional Paper 16 (Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California, 1988); Nicole Louise Branton, “Drawing the Line: Places of Power in the Japanese-American Internment Eventscape” (Ph.D. diss., University of Arizona, Tucson, 2004); Teresita Majewski, “Historical Ceramics,” in Three Farewells to Manzanar: The Archaeology of Manzanar National Historic Site, California, edited by Jeffery F. Burton, Publications in Anthropology 67 (Tucson, Ariz.: Western Archaeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1996), pp. 793–862.

Bibb, “Japanese Ceramics”; Julia G. Costello, Judith Marvin, Scott Baker, and Leland E. Bibb, “Historic Study Report for Three Historic-Period Resources on the Golf Club Rehabilitation Project on U.S. 395 near Bishop, Inyo County, California” (Bishop, Calif.: Report prepared for Department of Transportation by Foothill Resources, 2001); Jerry Schaefer and William McCawley, “A Pier into the Past at Point Mugu: The History and Archaeology of a Japanese-American Sportfishing Resort” (Encinitas, Calif.: Report prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District, by ASM Affiliates, 1999). I draw Japanese terminology from the following soures: Nishida and Ohashi, “KoImari”; Penny Simpson, Kanji Sodeoka, and Lucy Kitto, The Japanese Pottery Handbook (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1979); Shinichi Yashiro, Inbante ni miserareta kurashi [Enchanted living with printed wares] (Tokyo: Gakken, 2001).

David Miller, “Plain Blue-and-White Soba Choko,” Daruma (Amagasaki, Japan) 23 (1999): 30–38; Simpson et al., “Japanese Pottery Handbook.”

Costello and Maniery, Rice Bowls in the Delta; Schaefer and McCawley, “Pier into the Past”; Bernard P. Stoltie, “Tokkuri and Friends: A Salute to the Japanese Sake Bottle,” Arts of Asia 25 (1995): 101–12; Cort, Shikaragi, p. 212; Jahn, Meiji Ceramics, p. 302.

Cort, Shikaragi, pp. 60–63, 120, 212.

Wilson, Archaeology of Edo, pp. 34–35.

Prudence Rice, Pottery Analysis: A Sourcebook (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), pp. 4–6.

Hazel Gorham, Japanese and Oriental Ceramics (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1971), p. 178.

Impey, Early Porcelain Kilns of Japan, p. 1.

Majewski and O’Brien, “Use and Misuse of Nineteenth-Century English and American Ceramics,” p. 125; F. H. Norton, Fine Ceramics: Technology and Applications (New York: McGraw-Hill, [1970]), p. 52; Wilson, Inside Japanese Ceramics, p. 46.

Gorham, Japanese and Oriental Ceramics, p. 107; Jahn, Meiji Ceramics, p. 113; Irene Stitt, Japanese Ceramics of the Last 100 Years (New York: Crown, 1974), p. 44.

Takehisa Yamada, “The Export-Oriented Industrialization of Japanese Pottery: The Adoption and Adaptation of Overseas Technology and Market Information,” in The Role of Tradition in Japan’s Industrialization: Another Path to Industrialization, edited by Masayuki Tanimoto, Japanese Studies in Economic and Social History Series 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Wilson, Inside Japanese Ceramics, p. 49.

Yamada, “Export-Oriented Industrialization of Japanese Pottery.”

Takeshi Nagatake, Classic Japanese Porcelain: Imari and Kakiemon (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2003), pp. 59–60.

The cavetto is defined here as the curved area between the well and rim of a vessel.

Bibb, “Japanese Ceramics,” p. 6; Tajimi, “Mino’s Engraved Wares,” p. 2.

See, for example, Bibb, “Japanese Stencilwares”; Miller, “Plain Blue-and-White Soba Choko.”

See Hironori Noguchi, Kuninori Numano, and Nobuko Numano, Meiji Taisho Showa no zugawari inban / Meiji, Taisho, and Showa Era Engraved Wares (Tokyo: Kobijutsu Mejiro Maruai, 1993); Alistair Seton, Igezara Printed China (Tokyo: Kogei, 1994); Yashiro, Inbante ni miserareta kurashi.

Penelope Mason, History of Japanese Art (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005); Merrily Baird, Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design (New York: Rizzoli, 2001), pp. 19–21; Saburo Mizoguchi, Design Motifs, Arts of Japan 1 (New York: Weatherhill, [1973]), pp. 103–28; John W. Dower, The Elements of Japanese Design: A Handbook of Family Crests, Heraldry and Symbolism (New York: Walker/Weatherhill, 1971), p. 23.

Joan Collett Oates, Phoenix Bird Chinaware: A Collector’s Encyclopedia of Its Past, Its Pieces, Its Potteries; Book One (West Bloomfield, Mich.: J. C. Oates, 1984); Joan Collett Oates, “Phoenix Bird Chinaware,” in The Collector’s Encyclopedia of Nippon Porcelain, Third Series, edited by Joan Van Patten (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 1986), pp. 60–64.

Elyce Litts, The Collector’s Encyclopedia of Geisha Girl Porcelain (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 1988), pp. 8–13.

Gorham, Japanese and Oriental Ceramics, pp. 85–87; Sanders, World of Japanese Ceramics, pp. 189–91.

Costello and Maniery, Rice Bowls in the Delta, pp. 52–55; Bibb, “Japanese Stencilwares.”

Nishida and Ohashi, “KoImari,” pp. 56, 147.

Baird, Symbols of Japan, p. 87; Mizoguchi, Design Motifs.

Bibb, “Japanese Ceramics.”

Litts, Collector’s Encyclopedia of Geisha Girl Porcelain, p. 58; Seton, Igezara Printed China.

See, for example, Litts, Collector’s Encyclopedia of Geisha Girl Porcelain; Joan F. Van Patten, The Collector’s Encyclopedia of Nippon Porcelain (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 1979); Carole Bess White, The Collector’s Guide to Made in Japan Ceramics: Identification and Values (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 1994).

Van Patten, Collector’s Encyclopedia of Nippon Porcelain, pp. 26–30; Costello and Maniery, Rice Bowls in the Delta, p. 27; Litts, Collector’s Encyclopedia of Geisha Girl Porcelain, p. 58.

Dower, Elements of Japanese Design, p. 52; Rebecca Allen, R. Scott Baxter, Anmarie Medin, Julia G. Costello, and Connie Young Yu, “Excavation of the Woolen Mills Chinatown (CA-SCL-807H)” (San Jose, Calif.: Report prepared for California Department of Transportation by Past Forward, Richmond, Calif., 2002); Bibb, “Japanese Ceramics”; Jeffery F. Burton, The Fate of Things: Archaeological Investigations at the Minidoka Relocation Center Dump, Jerome County, Idaho (Tucson, Ariz.: Western Archaeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2005); Costello and Maniery, Rice Bowls in the Delta; Fred W. Mueller Jr., “Asian Tz’u: Porcelain for the American Market,” in Wong Ho Leun: An American Chinatown, edited by The Great Basin Foundation (San Diego: Great Basin Foundation, 1987).

See, for example, Burton, Fate of Things; Bob Muckle, “Archaeology of Nikkei Logging Camps in North Vancouver,” Nikkei Images (Japanese Canadian National Museum and Archives Society) 9, no. 4 (2004): 1–3.

For a discussion of the economic circumstances of this period, see Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 139–43.

Ruth Ann Sando and David L. Felton, “Inventory Records of Ceramics and Opium from a Nineteenth Century Chinese Store in California,” in Priscilla Wegars, Hidden Heritage: Historical Archaeology of the Overseas Chinese (Amityville, N.Y.: Baywood, 1993), pp. 151–76.