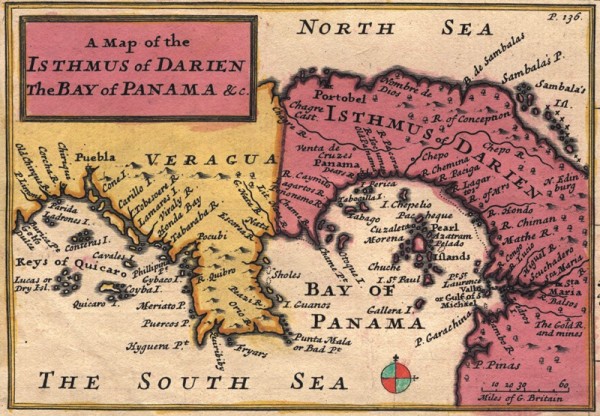

Map detail from “A New & Exact MAP of the Coast, Countries / and Islands within y.e LIMITS of y.e / SOUTH SEA COMPANY, / from y.e River Aranoca to Terra del Fuego, and from thence / through y.e South Sea to y.e North Part of California &c. / with a View of the General and Coasting TRADE-WINDS. / And particular Draughts of the most important Bays, Ports &c. / According to y.e Newest Observations, By Herman Moll Geographer,” ca. 1740 (originally published in 1711), London, England. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Dish, China, Wanli period, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 5/16". (Courtesy, Thomas Lurie.)

Bowl fragment, China, late sixteenth century. Hard-paste porcelain. Excavated by Felipe Gaitan-Ammann at the house of the Genoese slave traders, Panama. (All archaeological fragments courtesy, Mirta Linero Baroni, Jefe de Arqueología, Patronato Panamá Viejo.)

Bowl, China, sixteenth century. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue and red and green overglaze enamels. D. 3 5/8". (Courtesy, Museum Het Princessehof, Leeuwarden.)

Dish fragment, China, ca. 1565. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. Excavated by Felipe Gaitan-Ammann at the house of the Genoese slave traders, Panama.

Dish, China, ca. 1550. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. D. 12". (Courtesy, Frides Lameris Art and Antiques, Amsterdam, Netherlands.)

Bowl, China, ca. 1585; mounts, London, 1575–1585. Hard-paste porcelain with English silver-gilt mounts. H. 8 1/2", D. including handles 18 1/4". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944.)

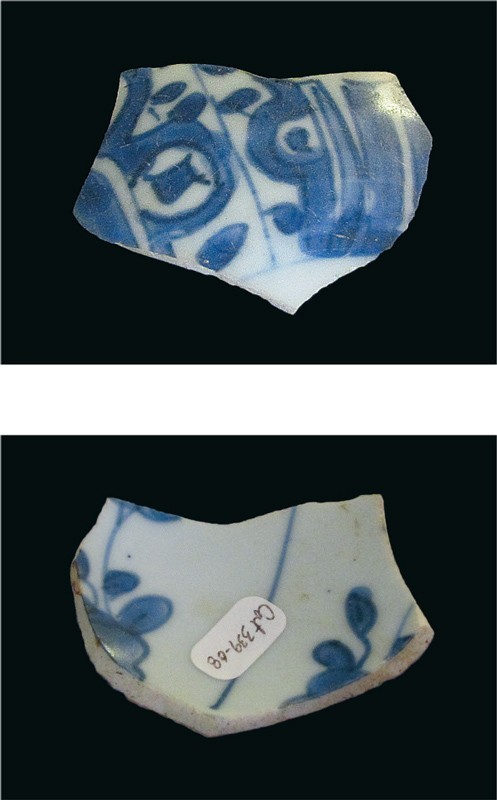

Bowl fragment, China, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. Excavated at the convent of the Monastery of the Concepción, Panama.

Bowl, China, ca. 1585; mounts, London, 1575–1585. Hard-paste porcelain with English silver-gilt mounts. H. 6 1/4", D. including handles 13". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944.)

Bowl fragments, China, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. Excavated at the convent of the Monastery of the Concepción, Panama.

Dish fragment, China, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. Excavated at the convent of the Monastery of the Concepción, Panama.

Dish fragment, China, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. Excavated at the convent of the Monastery of the Concepción, Panama.

Dish, China, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. D. 14". (Courtesy, Collection of Thomas Lurie.)

Dish fragment, China, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. Excavated by Felipe Gaitan-Ammann at the house of the Genoese slave traders, Panama.

Dish, China, ca. 1625. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. D. 8 3/8". This dish was recovered from the 1625 wreck of the Wanli, a Portuguese ship laden with Chinese ceramics that sank en route from Macao to the Straits of Melaka. (Courtesy, Sten Sjostrand and Nanhai Marine Archaeology.)

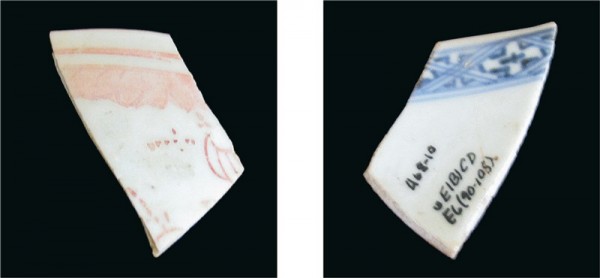

Dish fragment (front and back), China, 1573–1620. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue decoration. Excavated at the convent of the Monastery of the Concepción, Panama.

This brief article illustrates some recent finds of early Chinese porcelain recovered from archaeological excavations in Panamá la Vieja. Located at the narrowest part of the Panama isthmus on the Pacific side of the colony, Panamá la Vieja was founded in 1519 (fig. 1). This early port city played an important role in a complex trade route that facilitated the export of silver from the New World to the Old along with an influx of Chinese goods from the Pacific maritime traffic.

Spanish trade in the Pacific waters began in the sixteenth century, when Ferdinand Magellan had claimed the Philippine Islands for the Spanish Empire. The Philippines had been a market for Chinese ceramics since the Tang dynasty (618–906), but after Spain established the trading post of Manila in the mid-1500s, Spanish travelers quickly saw the opportunity to send Chinese porcelain to the Spanish colonies in the Americas. The first Spanish galleon crossed the Pacific from Manila to Acapulco, Mexico, in 1565, but large shipments of porcelain did not begin to arrive until 1573.

The Chinese export porcelain from this period (the late Ming dynasty) is called “kraakware” by twentieth-century collectors. Although evidence of these porcelains was found in Panama prior to the uncovering of fragments in Panamá la Vieja, the fragments discussed in this article were archaeologically recovered in stratigraphic sequences that permit more refined dating in these late sixteenth- to the mid-seventeenth-century contexts.[1]

Figure 2 illustrates a blue-and-white kraak porcelain dish, a typical example of the export ware manufactured in South China between the 1570s and the 1640s. These wares were produced in huge quantities for the export trade, and many authors have tried to posit a chronological evolution for such wares. Fortunately, the excavation of several notable shipwrecks discovered in the last two decades has expanded our ability to date these wares.

In addition to fragments unearthed at the Monastery of the Concepción, this article illustrates finds from the site of a seventeenth-century house that had been occupied by Genoese slave traders.[2] During the period 1662–1671 there was an infirmary for slaves adjacent to this “House of the Genoese,” a three-story house built sometime after 1600.

After Panamá la Vieja was destroyed by fire in 1671—in an unfortunate attempt by the Panamanians to protect themselves from the notorious privateer Henry Morgan—most of the residents moved a few miles to the west.[3] Not everyone with ties to the Spanish colony vacated the city, however—slave traders, among others, returned. Found in association with the slave infirmary is a fragment with kinrande (Japanese for “gold brocade”) decoration (fig. 3). This type of decoration typically has overglaze enamels on the exterior and an underglaze blue trellis border on the rim of the interior. Such pieces were made during the middle of the sixteenth century and probably into the seventeenth century. Although much of the overglaze enamels have worn off, the remaining red enamel with some gold and slight traces of green enamel can be compared with that on the rare intact bowl illustrated in figure 4. The large dish fragment with a duck on it (fig. 5) may also have been associated with the earlier context on the site since that motif was prevalent from the second half of the sixteenth century until well into the seventeenth century.[4] This fragment can be compared with the plate in figure 6.

The two Chinese porcelain bowls with contemporary English silver-gilt mounts illustrated in figures 7 and 9 were originally from the collection of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, who was Treasurer under Queen Elizabeth I. Now part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection, these bowls were made during the Wanli period (1573–1619); the English silver-gilt mounts bear the mark of a silversmith working in London in about 1575–1585.[5] Since there was no direct trade between England and China during the sixteenth century, it is conceivable these pieces of porcelain went to England through privateers, such as Sir Francis Drake, or through trade between the English and the Ottoman Empire.[6]

The bowl in figure 7 illustrates horses galloping along the rim, similar to the horse on the fragment in figure 8.[7] A similar bowl with horses galloping at the rim is in the collections at Burghley House, Lincolnshire, and was reputed to have been presented by Queen Elizabeth to her godchild, Sir Thomas Walsingham, both of whom were financial backers for Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation, which began in 1577. As such, they were in effect the owners of part, if not all, of the goods taken in his voyage.[8]

The fragments shown in figures 10 and 11 have decoration on them similar to that on the bowl shown in figure 9, with deer in compartments on the exterior and flowers on the interior. Jessica Harrison-Hall, a scholar of Chinese ceramics, notes that such bowls, made from 1586 to 1613, were found at the San Diego (1600) and the Witte Leeuw (1613) shipwrecks.[9]

The central decoration on the dish fragment in figure 11 shows a deer in a landscape which includes puzzling wheel-shaped motifs, flowers, and debased floral motifs.[10] The wheel-shaped motif originally may have represented rocks but evolved into what resembles the wheel of the law, signifying Buddha’s first sermon in the Deer Park at Sarnath.[11] The intact dish illustrated in figure 13 reveals decoration similar to that in the fragment, with two deer in a landscape with rocks or debased wheels at the lower part of the central scene.[12] The floral motifs include needles on a fir tree, and the branch with leaves closely relates to the branch on the fragment in figure 12. Another dish with a similar decorative scheme was found at the San Diego shipwreck, helping date that piece and similar objects.[13] The bird-on-branch motif appears on the reverse of a comparable dish that Chinese ceramic historian Maura Rinaldi dates 1575–1605.[14]

It should be noted that similarly decorated pieces were made over a long period of time, and it is often through the fortunate recovery of such shipwreck cargoes as those of the San Diego that scholars are able to assign date ranges to pieces. The dish with two deer on it from the House of the Genoese slave traders (fig. 14) is a more schematic version of the piece shown in figure 13 and resembles the circa 1625 dish from the Wanli wreck (fig. 15).

Although kraak pieces generally have alternating wide and narrow panels, the decoration on the fragment in figure 16 is quite different: identical flowers are placed within wide panels, and there are no narrow panels whatsoever. Such rim decoration can be found on pieces recovered from the San Diego shipwreck site, as well as at the site of the Nossa Senhora de Mártires, a Portuguese ship wrecked in 1606 in the Tagus River off Lisbon.[15]

The excavations in Panamá la Vieja provide firsthand evidence of the use and ownership of Chinese porcelain in Spanish colonies at the very early inception of what was to become an important trade for western European countries throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The fragments in Panamá la Vieja must have served as important objects for both function and display. Regardless of how they were used, to Spanish colonials the wares served as reminders of contact with Asia, just as they are reminders to present-day archaeologists and ceramic scholars of that complex trade system.

Linda R. Shulsky, “Chinese Porcelain in Spanish Colonial Sites in the Southern Part of North America and the Caribbean,” Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 63 (January 2000): 83–98.

Felipe Gaitan-Ammann, “Daring Trade: An Archaeology of the Slave Trade in Late-Seventeenth-Century Panama (1663–1674)” (Ph.D. diss., Department of Anthropology, Columbia University, New York, 2012); Final Report, 2006 Summer Field School: Macro-Coordinates 500/550N–800/850E: “Associated Monument: La Concepción Convent,” unpublished manuscript presented by Beatriz Rovira, Juan Guillermo Martín, Laura Patricia Bejarano, Alejandro Erazo, Bibiana Etayo, Luis Gerardo Franco, Alejandra Garcés; Tomás González, Paola Sanabria and Catalina Sánchez of the Patronato Panamá Viejo, Panamá.

The site of the old city, which was covered by jungle, was preserved and is now part of an archaeological park.

For examples of intact dishes decorated with the duck motif and possessing shipwreck contexts, see Edward Von der Porten, “The Early Wanli Ming Porcelains from the Baja California Shipwreck Identified as the 1576 Manila Galleon San Felipe,” Mains’l Haul 46 (Winter/Spring 2010): 65; and Sten Sjostrand and Sharipah Idrus, The Wanli Shipwreck and Its Ceramic Cargo (Malaysia: Department of Museums, 2007), p. 289, no. 2636

The two bowls were part of a group of five pieces from the estate of J. P. Morgan that were purchased by the Metropolitan Museum in 1944. Louise Avery, “Chinese Porcelain in English Mounts,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, n.s. 2, no. 9 (May 1944): 266–72.

Two Spanish galleons were captured off the Azores by Drake, the San Felipe (1587) and the Madre de Dios (1592). Drake also captured the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción off the coast of Peru in 1579. Jacqueline Pearce and Jean Martin, “Oriental Blue and White Porcelain found at Archaeological Excavations in London: Research in Progress,” Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 67 (2004): 99–109, 101. William Cecil, Lord Burghley, was instrumental in the establishment of an English consulate at Istanbul in 1579.

Similar examples are illustrated by Maura Rinaldi, Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of Trade (London: Bamboo Pub., 1989), pp. 146–49; and Regina Krahl and Nurdan Erbahar, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Porcelains, vol. 2 of Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul: A Complete Catalogue, edited by John Ayers, 3 vols. (London: Sotheby’s Publications, in association with the Directorate of the Topkapı Saray Museum, 1986), p. 725, no. 1280.

Sian Flynn and David Spence, “Imperial Ambition and Elizabeth’s Adventurers,” in Elizabeth: The Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, edited by David Starkey and Susan Doran, exh. cat. (London: Chatto & Windus, in association with the National Maritime Museum, 2003), p. 148.

Jessica Harrison-Hall, Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum (London: British Museum Press, 2001), p. 297. See also Jean-Paul Desroches et al., Treasures of the San Diego (Paris: AFAA; [Manilla]: National Museum of the Philippines, 1996), p. 344, no. 117, and C. L. van der Pijl-Ketel, ed., The Ceramic Load of the “Witte Leeuw” (1613) (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1982), p. 141, pl. 11:6.

For a similar dish, see Krahl and Erbahar, Yuan and Ming Dynasty Porcelains, p. 710, no. 1223.

Rinaldi, Kraak Porcelain, p. 79, pl. 54.

Recent excavations at Jingdezhen, the porcelain-making city in southern China, have turned up plates with two deer on them like figure 14 and bowls with deer in panels like those in figure 9. Archaeologists have concluded that quality could vary greatly, and that “kraak porcelain produced for domestic market and export was fired in the same kiln.” Cao Jianwen and Luo Yi Fei, “Sites in Jingdezhen City in Recent Years,” Oriental Art 50, no. 4 (2006): 16–24, p. 22.

Desroches et al., Treasures of the San Diego, p. 314.

Rinaldi, Kraak Porcelain, p. 93, pl. 77.

Desroches et al., Treasures of the San Diego, p. 315, fig. 4; and Simonetta Luz Alfonso, Adília Moutinho de Alarcão, Miguel Aleluia, Francisco Alves, and Raffaelo D’Intino, Nossa enhora dos Mártires: A Última Viagem [The last voyage] (Lisbon: Verbo, 1998), p. 244.