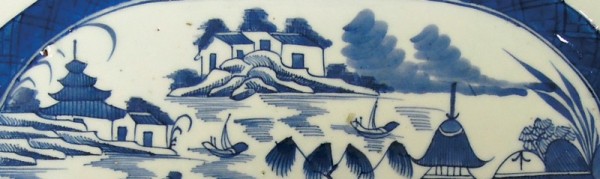

Blue-and-white dish, Canton, China, 1785–1835. Porcelain. H. 13", W. 16 1/2". (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Leslie Warwick.)

Blue-and-white plate, Canton, China, 1785–1835. Porcelain. D. 9". (Private collection.)

Blue-and-white pitcher, Canton, China, 1785–1835. H. 14 1/2". (Private collection.)

Detail of the border of the Canton dish illustrated in fig. 1, showing an outer starry border, clouds, and an inner cavetto fence.

Detail of the Canton dish illustrated in fig. 1, showing rocks, two intertwined trees, and a waterwheel.

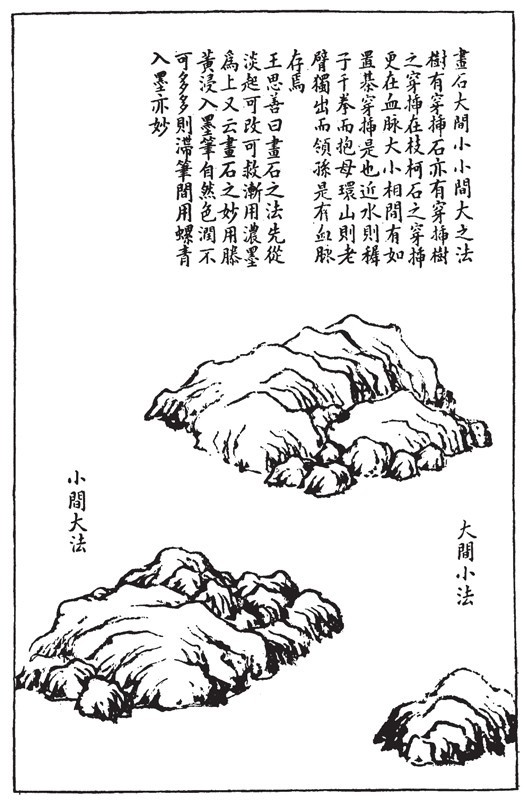

Rocks (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 131).

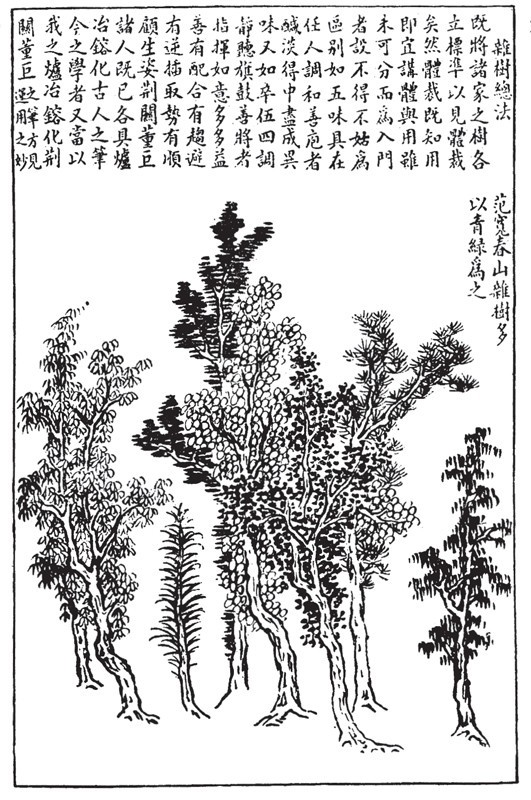

Tall dark pine intertwined with a white deciduous tree (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 85).

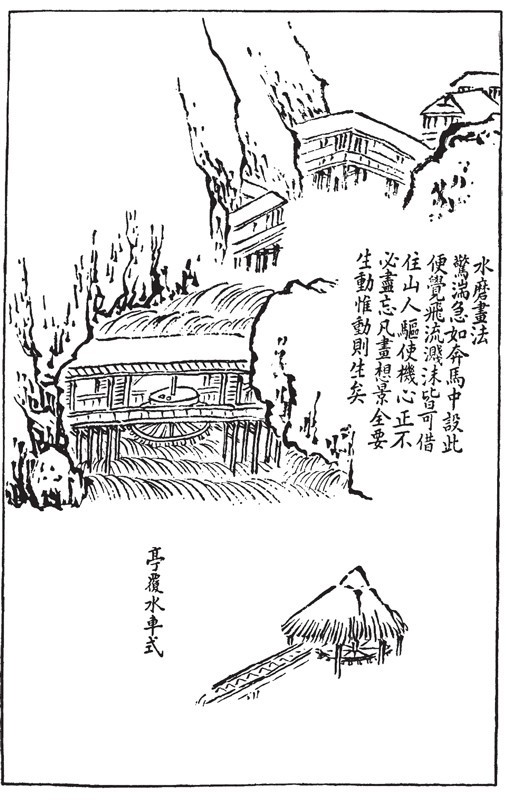

Waterwheel (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 290).

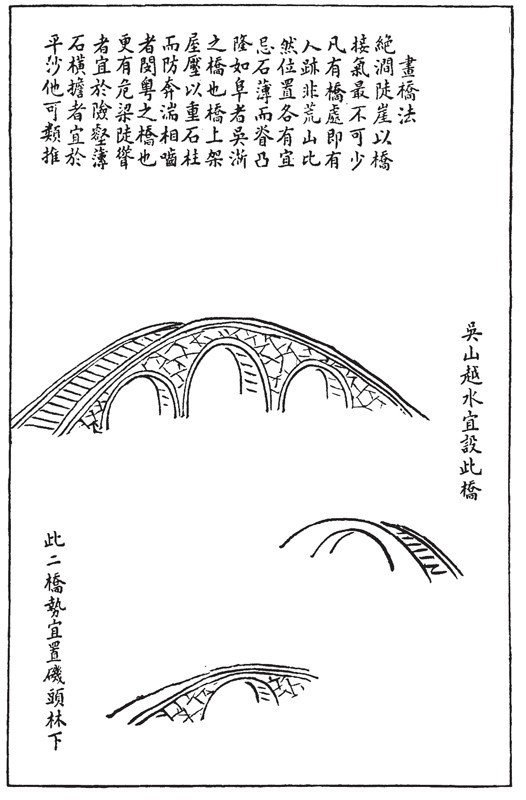

Bridge (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 286).

Detail of the Canton dish illustrated in fig. 1, showing a bridge, a willow tree, and a scholar in a pavilion.

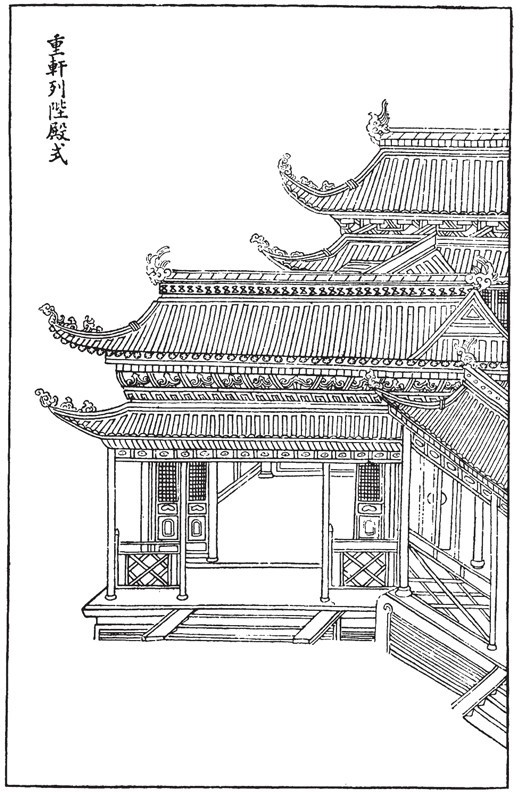

Pavilion (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 296).

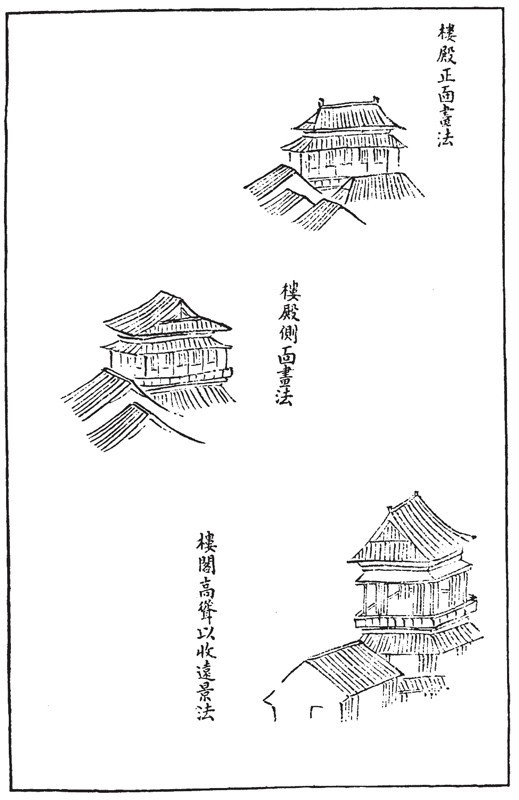

Lookouts (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 268).

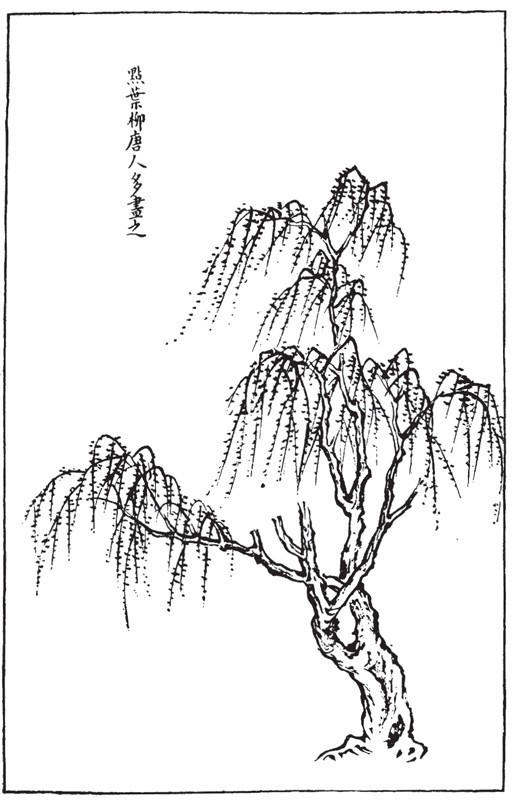

Willow trees (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 112).

Detail of the Canton dish illustrated in fig. 1, showing a pagoda, clusters of houses, fishing boats, and mountains.

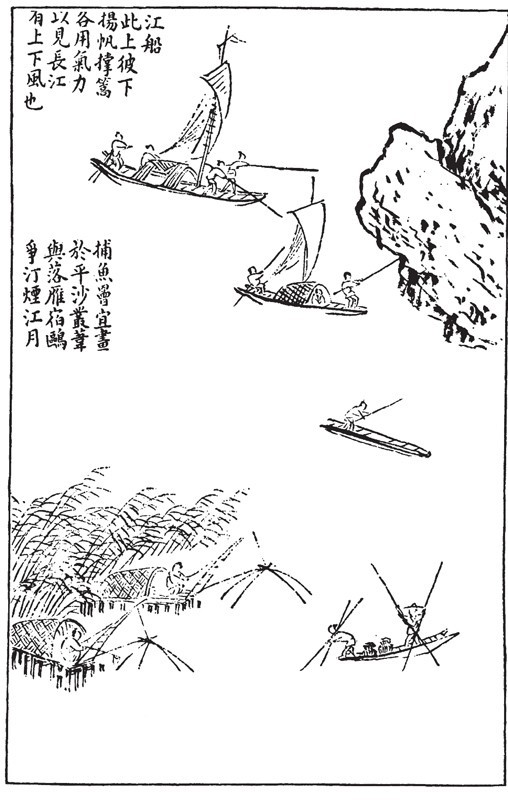

Riverboats (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 304).

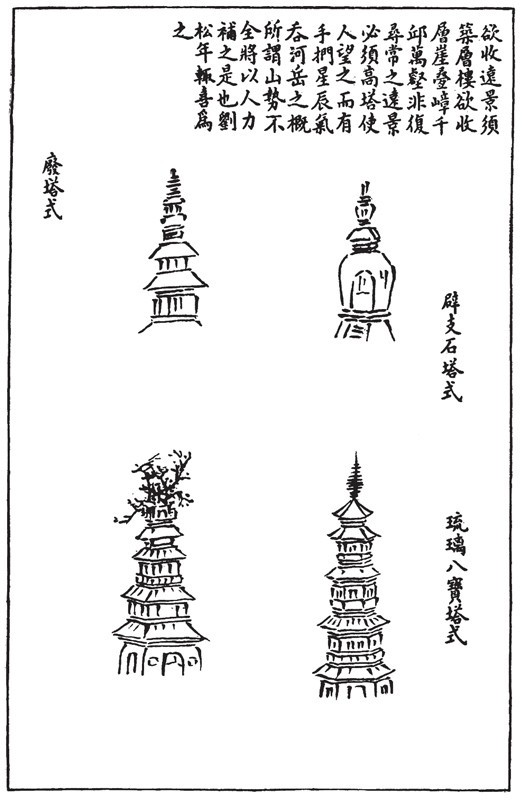

Pagodas (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 292).

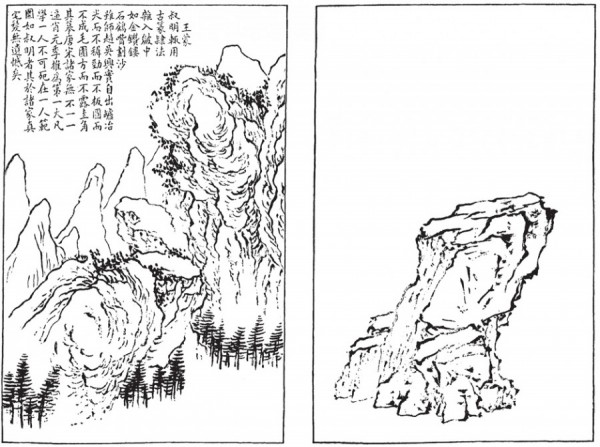

Two kinds of mountains (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, pp. 188, 194).

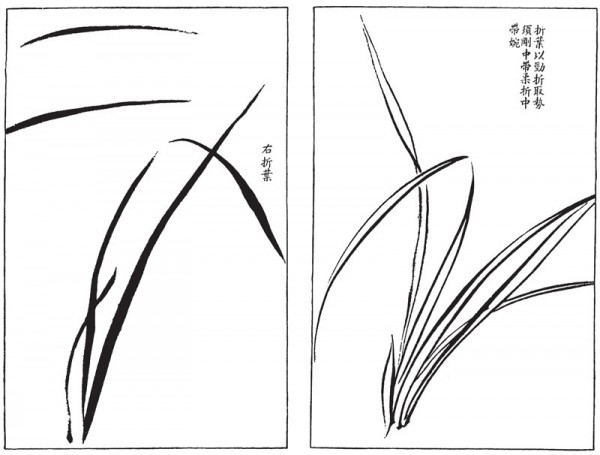

Left: Leaves of the marsh orchid (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 335). Right: Leaves of the grass orchid (ibid., p. 344).

Most of the Chinese porcelain imported to America was the blue-and-white porcelain known as “Canton,” as evidenced by the great amount that survives today. Canton was named for the province in southern China from which it was exported. However, when thinking about Canton porcelain, what comes to mind is Rodney Dangerfield’s “I can’t get no respect!” Despite being the most popular Chinese export pattern, it was often dismissed as artistically inferior, as in this point of view expressed circa 1820 by Robert Waln of Philadelphia:

The character of Chinese Painting is totally different from the settled principle of the art in our country, and a landscape after their fashion appears one of the most incongruous things in the world: having no regard to perspective, the background is represented in a preposterous manner by placing it above the more advanced objects in the picture: the intermediate representations are arranged in the same way, according to their situation, all bearing the same tint. Variety of colors are seldom or ever used, and to the eye accustomed to the vivid beauties of a West or the proportioned excellence of a Trumbull, the whole appears a mass of black marks, representing nothing: no shading is used and at the best it can be considered the bare outline of an unsuccessful attempt to imitate nature.[1]

In this article we will attempt to show that this view is based on a lack of understanding of the Chinese view of landscape art and the symbols in the Canton scene (fig. 1), and the difference in perspective between the West and the Chinese in portraying and viewing landscapes. We begin by giving a brief history of Canton porcelain.

History

In the fifty years spanning 1785–1835, one of the most valuable Chinese exports to the United States was porcelain. Indeed, Chinese porcelain was so popular during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that the country’s name became synonymous with its porcelain, china. Americans bought Canton porcelain because they thought it was decorative and enjoyed what they considered to be exotic scenes. To the Chinese, however, the images in their painted landscapes bore deep symbolic meanings that had been passed down for many centuries.

Pottery has been manufactured for at least two thousand years in China, beginning in the Han dynasty. The Chinese were making hard-paste porcelain by the sixth century, and their porcelain, the best in the world for centuries, was collected for its beauty and rarity. In 1710 the secret of making Chinese-style porcelain was discovered by Johann Friedrich Bottger in Meissen, Germany.[2] Most Chinese porcelain is thought to have been made in the city of Ching-Te Chen on the Yangtze River, about four hundred miles north of Canton. It is believed that Canton porcelain, however, was made in the south at Shaouking (about five miles west of Canton); several factories there produced porcelain of lesser quality, perhaps due to the area’s more poorly refined clay.[3] Since Canton did not have customized patterns or colors other than blue and white, the porcelain was given its final firing in Shaouking and then transported a short distance to Canton, helping to keep its price low. A statement made in the early nineteenth century by Augustine Heard, a prominent Boston merchant in the China trade, supports this belief: “All the porcelain came from the north except the willow pattern [Canton] and the ‘sister’ ginger-pots in blue and white which were made in the south.”[4]

In 1757 the Chinese imperial court had limited all foreign seaborne imports and exports to the port of Canton. One year after the United States gained its independence, however, trade with China opened; the first Chinese porcelain arrived in New York in 1785 on the Empress of China. After England embargoed all imports of Chinese porcelain in 1790 in order to protect its own porcelain industry, America became the largest importer of Chinese porcelain. Only tea and textiles had greater value. In return, China wanted only ginseng, furs, and money from America.[5] The early commerce with China was dominated by Salem, Boston, Providence, Philadelphia, and New York, but after 1826 the main ports were New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. The first three American millionaires—John Jacob Astor of New York, Stephen Girard of Philadelphia, and Thomas Handasyd Perkins of Boston—all made their fortunes in the China trade and, to their credit, none of them ever paid for tea with opium.

Canton porcelain became popular in the States for several reasons. It was a practical alternative to redware and pewter, which were toxic because of their lead content, especially with acidic foods, and to treen ware, which was unsanitary because food bacteria penetrated the wood. Canton porcelain was more durable and more exotic than European porcelain and, before 1820, it was less costly.[6]

The Canton pattern was considerably cheaper than porcelain with custom-painted arms and Nanking porcelain, another blue-and-white porcelain pattern with a different border. Custom-painted porcelain and Nanking, which were higher-quality porcelains, were more expensive and therefore imported in much fewer numbers. In the period 1794–1798, the price of a table setting in the Canton pattern, consisting of 172 pieces, cost the equivalent of $22 in China, whereas Nanking table settings cost $80–$100 and custom-painted table settings $150–$200.[7] However, by the early 1800s a 50-piece Canton tea service cost an American consumer only about $3, equivalent to about $40 today.[8] Because it was comparatively inexpensive, the Canton pattern became the porcelain of choice for the middle and lower classes, although even George Washington had Canton. There are fourteen pieces of Canton at Mount Vernon, and the distribution of sherds dug there suggests that Canton was used in greater quantities than any other porcelain.[9]

The peak years of importation of Canton porcelain were 1817–1818, after which its popularity declined sharply. This appears to be the result of declining quality in both the porcelain and its painting, coupled with falling prices of English porcelain. Canton porcelain was thicker and clumsier than English porcelain. Its edges and bottoms were rough and the glaze was sometimes unevenly applied and splotchy in contrast to higher-quality English transfer wares. Moreover, the painting on Canton plates, cups, and other common items became very sketchy.[10] However, the less common pieces—platters, pitchers, tureens, salad bowls, teapots, candlesticks—continued to be finely painted (figs. 1, 3).

There were also breakage issues, exacerbated by the long voyage to the eastern United States. Because of its weight and resistance to water damage, porcelain was stored as ballast in the bottom of a ship’s hold, where it took a beating from the rough seas. The porcelain was poorly packed in crates filled with straw, resulting in breakage. The perishable teas and textiles were stored on top of the porcelain crates so they would be safe from the bilge water. By 1835 imports of porcelain from China were low; they ceased almost entirely from 1839 to 1860 owing to the Opium Wars between England and China. After 1860, only New York continued to import Chinese porcelain, and in much reduced quantities.[11]

Stability of the Canton Scene

The scene depicted on Canton porcelains remained fixed for more than a hundred years, except for slight variations necessitated by the available surface area; compare, for example, the Canton pattern of the platter illustrated in figure 1 and the pitcher illustrated in figure 3. Given the Chinese government’s strict control over interaction with the outside world, it is likely that this pattern had to be approved by the bureaucracy and became the official pattern, perhaps distributed to the painters via woodblock prints. Maxwell K. Hearn, Douglas Dillon Curator in Charge of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, supports this view: “I found the consistency of the imagery from pitcher to platter fascinating and absolutely convincing that the artists were working from a common template.”[12]

Sources of the Canton Images

The sources of the images on Canton porcelain are found on the early Chinese painted ink scrolls on silk or paper, images such as a scholar in a house, bridges, trees, rocks, mountains, and fishing boats on the water.[13]

Hills and streams, or shan shui, are the two characters the Chinese use to represent the word “landscape.” Hills and streams are elements common to both Chinese landscape painting and landscape decoration on ceramics. The same attitudes toward nature, the same techniques of brush painting, and the same artistic conventions for painting natural scenery are found in both media.[14]

When we proposed to Maxwell Hearn that the Canton image came indirectly from Song painting sources, he agreed:

[It] surely has some resonance with earlier landscape imagery, but is most likely related to the revival of Song styles that occurred in the seventeenth century and which had a major impact on the Ming-Qing Transitional wares of that time (1644–1736). The Canton wares are probably descended from that lineage.[15]

These images have been traditional in Chinese paintings for more than a thousand years. This is illustrated in The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (1679–1701), a compilation of earlier books on landscape painting that had been preserved for many generations and were collected by a family in China. The manual consists of two parts: Trees, Rocks, and Jen-Wu (people, animals, buildings, and boats); and Orchids, Bamboo, Plums, and Chrysanthemums. It instructs the reader on how to paint in the traditional style and attempts to develop the painter’s spiritual resources (ch’i).

The Importance of the Fluid Line

The importance of the fluid line to express ch’i in Chinese landscape paintings is emphasized by the absence of color, which was thought to distract viewers from perceiving the deeper meanings of the lines.[16] The fluid line tradition relates to Chinese calligraphy, which requires great control of the brush because of the complexity of the characters and is valued as a great art in its own right. Unlike working in oil, painting with ink and watercolor leaves no room for error on the part of the artist. This discipline, this control of the brush, generates great respect for the fluid line, emphasizing clarity and spontaneity. Chinese painters traditionally used predominantly black or brown inks on landscape scrolls, and usually very little color. This monochrome tradition of using black or brown ink on silk and paper carried over to decorating early porcelain.

When the Chinese developed “true” porcelain using kaolin and petuntse clays, the only color that could be fired at the required high temperature of 1200–1400°C was cobalt blue, so for generations that was the color used in China—even after new colors became available. Westerners, however, found color enhanced both their mood and their appreciation of a realistic landscape scene. Monochrome drawings were usually considered preliminary studies for the final work in oil in the West at that time and rarely drew the attention of art connoisseurs.

Portraying Perspective

Another aspect in which the Chinese differ from Westerners is in their rules for portraying perspective. The Chinese never used isometric perspective successfully to show objects in depth because the traditional Chinese painting represents distance from the viewer by the height of the object in the scene. For example, near objects are low in the scene and far objects are high in the scene. In the West, artists since the Renaissance have employed perspective with close objects larger and distant objects smaller, using diagonal lines to a focal point to size the objects. The Chinese did attempt to vary the height of the object with distance but did not use diagonal lines to a focal point to size the objects, maintaining distant objects are not smaller than near objects. This different view of portraying perspective can tend to make the Chinese scenes look flat and unsophisticated in the eyes of the West, but this is simply a cultural difference.

Reading Chinese Paintings

In the West, people look at landscapes to admire the beauty of the scene as a whole; often painted in oils on canvas, the entire scene is visible, and when hung on the wall can be viewed by many. Comments by the artist and former owners are not made part of the work. Chinese landscapes, however, are typically painted in ink or watercolors, on silk or paper scrolls, which are held in a viewer’s hands and unrolled slowly, actions that let the scene unfold gradually and provide a more intimate experience of the work. Comments by the artist or former owners are often displayed in calligraphic poems as part of the work.

In his discussion of the great fourteenth-century painter Zhao Mengfu in How to Read Chinese Paintings, Hearn explains that painting “was not merely about representation [but was] poetic and pictorial imagery and energized calligraphic lines working in tandem to express the mind and emotions of the artist.”[17] The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting elaborates:

There is an old saying that those who are skilled in painting will live long because life created through the sweep of the brush can strengthen life itself, both being of the ch’i. But to create life one must comprehend the li (principle) of life; without that knowledge and understanding, it is impossible for the ch’i to rise. This book clearly is dedicated to encouraging an understanding of li so that people may achieve jen (Goodness) and longevity.[18]

These statements illustrate the underlying belief of the Chinese philosophy of life, that order and harmony of nature are also “the harmony of Heaven and Earth.”[19] The Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist classics that are quoted liberally in the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting all share this basic philosophy. In Taoism, the yin and the yang are two complementary aspects of every phenomenon, representing the balance in nature.

Analyzing the Canton Scene as a Chinese Landscape Painting

The Canton landscape image portrays the harmony of nature, as can be seen on the Canton platter illustrated in figure 1. On Chinese scrolls, the painting often begins with a colored silk “moat” that signifies to the viewers that they are leaving their world and entering the painter’s world.[20] The blue outer border on the Canton platter performs a similar function (fig. 4). It begins with an outer sub-band of diagonal lines, followed by a zigzag pattern with stars at the intersections in dark blue, all on a blue ground representing a starry sky. It is followed by an inner sub-band of dark blue diagonal lines above a scalloped line on a white background representing clouds. Balancing the dark blue border (yin) is a white border (yang) of the same width, creating a balanced harmony.

Following the white border is a cavetto fence on a dark blue background that encloses the Chinese landscape. A series of Great Walls were built to protect China from outsiders starting in the fifth century B.C. The Chinese believe their country is a walled garden that has all they need, and therefore they do not need to explore outside it. This belief was so strong that in the fifteenth century they abandoned their navy, which consisted of three hundred huge junks, and thus gave up ambitions to be a world power. Instead, they turned to inner exploration to develop their culture. During the Song revival of the late seventeenth century, when China was again ruled by foreigners from the north (the Manchus), the Chinese looked to the past to find new ideas for the present.[21] They isolated themselves from the world and in the 1700s and 1800s required that all trade be restricted to the port of Canton in a highly controlled manner with many rules and regulations.

When you cross the fence on the platter, you enter the garden with, among other things, rocks, which symbolize endurance (fig. 5). Everything, including rocks, has ch’i, a spirit that shows movement and life, and the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting states: rocks must have veins and hollows to show the life within them. They must have light and shadow (yin and yang), height, depth, and volume. The rocks must be irregular, having been sculpted by nature.[22] “Large and small rocks mingle and are related like the pieces on a chessboard. Small rocks near water are like children gathered around with arms outstretched toward the mother rock. . . . There is kinship among rocks (fig. 6).”[23]

Behind the rocks grow two intertwined trees, one evergreen (yin) and one deciduous (yang). The evergreen in the back is a pine, which is taller and darker than the outlined white-leaf deciduous tree (see fig. 5).

Because the pine tree remains green through the winter, it is a symbol of survival. Because its outstretched boughs offer protection to the lesser trees of the forest, it is an emblem of the princely gentleman. For recluse artists of the tenth century the pine had signified the moral character of the virtuous man.[24]

The deciduous tree is most likely a wu t’ung, or Chinese parasol tree, in which the phoenix bird of popular myth was said to have rested; it is a symbol of rebirth.[25] As the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting explains:

There are two ways of painting two trees together. Draw a large tree and add a small one; this is called carrying the old on the back. Draw a small tree and add a large one; this is called leading the young by the hand. Old trees should show a grave dignity and an air of compassion. Young trees should appear modest and retiring. They should stand together gazing at each other.[26]

The trees on Canton porcelain were drawn in the second way, first with a small tree then adding a large one. (It was much easier to add the pine in the back, after the young deciduous tree was painted.) The old, taller pine spreads out its limbs to protect the younger parasol tree. Thus both trees have life and ch’i (fig. 7).

To the left of the two intertwined trees is a small, bell-shaped structure on legs—a waterwheel (see fig. 5). The structure represents the force of moving water, the ch’i, and its depiction is simplified by the omission of the thatching of the roof, the water transport mechanism, and the waterwheel itself (fig. 8).

In the foreground is a three-arch bridge, which allows the ch’i to flow from one island to another (figs. 9, 10). “In paintings in which there are steep precipices and water flowing endlessly, bridges may be drawn to sustain the continuity of the ch’i. They should seldom be missing from pictures. Usually where there is a bridge there will be signs of people. . . .”[27]

Indeed, to the right of the scene is a solitary scholar-official sitting in his study reading a scroll in his pavilion, a structure open on all four sides to allow him to appreciate the 360-degree view of nature (figs. 10, 11). Chinese scholar-officials were chosen through examinations, and in the late eighteenth century there were 200–300 candidates per year (in a population of approximately 300 million).[28] Scholar-officials were to lead by their Confucian ideals and their moral and ethical values, but when moral deterioration and government corruption increased in society during the early years of the Manchu Qing dynasty (1644–1912), many Ming loyalists lived in self-enforced retirement and retreated to nature. Believing they could find truth through inner cultivation, scholar-officials searched for the real meaning of life by studying the teachings of the ancients through their poetry, calligraphy, and landscape painting.[29] “The scholar-official’s pavilions should be spacious and quiet, their emptiness filled with ch’i. . . .”[30] Figures should be “depicted in such a way that people looking at a painting wish they could change places with them.”[31] There is only one person, the scholar-official, in the landscape, emphasizing the importance of nature and the insignificance of man.

Steps coming up from the water welcome guests arriving by boat (see figs. 10, 11). The pavilion has tiled roofs with turned-up eaves, indicating the scholar-official is prosperous. A raised lookout is on the left of the pavilion by the edge of the water so that “one may survey the harvest or even feel that there one might touch the clouds” (fig. 12).[32]

In the center of the scene is a willow tree with a gnarled trunk leaning over the water with its four remaining branches (see fig. 10). It rides the wind and has endured much adversity. It does not break but bends in the breeze. Except on crudely painted plates, Canton landscapes portray the willow tree with four branches (fig. 13): “the four main branches . . . are analogous to the four limbs of man and the four directions or cardinal points, and [involve] the general symbolism of trees: the Tree of Life and the various ‘trees’ of knowledge, races, family, religions, etc.”[33]

Water, which gives life to all living things, has ch’i. The horizontal lines on the water in the scene indicate there is a gentle breeze creating ripples and fostering a serene mood. In the center of the landscape are three sampans (riverboats) under sail moving across the water under the breeze, which shows ch’i, though no sailors are in sight (figs. 10, 14). How these riverboats are to be drawn is shown in the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (fig. 15).

On the left side of the landscape on the rocky shore is a pagoda, a structure originally thought to attract spirits, deities, and immortals, and also used to house relics and to observe the stars (figs. 14, 16). The importance of the pagoda is explained in the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting: “If one is painting landscapes with scenes in the far distance, towers and pagodas should be included. . . . Such views should include pagodas to increase the effect of distance. People looking at these pictures feel that, reaching out, they could touch the stars, whose ch’i governs rivers and mountains.”[34]

In the far distance in the top center is a group of houses with tile roofs (which convey prosperity) set behind a “family” of rocks at the shore. Surrounding the houses and at the foot of the mountains beyond are distant pine trees (see fig. 14). At the top of the landscape, to the right of the houses and in the far distance, are two steep and rugged mountains painted in a light gray blue to indicate mist (see fig. 14). The mountains are often top-heavy, leaning forward as if they were about to fall, showing they are able to move and thus have ch’i (fig. 17).

The entire garden landscape scene on the Canton platter is framed on either side by two types of orchid leaves (see fig. 14). On the left, arcing over the waterwheel and pagoda, are marsh orchid leaves (fig. 18, left); on the right, hanging over the scholar’s garden, are grass orchid leaves (fig. 18, right):

The art of painting orchids depends entirely on the drawing of the leaves, and therefore the drawing of the leaves should be the first consideration. . . . Thus one draws leaves bending one way and raised in another, conveying the life movement of the plant. Leaves should cross and overlap but never repeat in a monotonous manner. Distinction should be made between the leaves of the grass or ordinary orchid and those of marsh orchid: the latter are slim and supple, the former wide and strong.[35]

Recent Research on Visual Responses to a Scene

Research published in 2007 shows that Asians look at a scene from a different perspective than do people from the West.

Westerners approach the world “analytically,” dividing what they observe into individual parts. Easterners tend to approach the world more “holistically,” perceiving by looking at “the whole” and emphasizing the interrelatedness of all things. . . . The differing cognitive styles of the analytic West and the holistic East parallel differences between the brain’s two hemispheres. The left hemisphere tends to perform more sequential and analytical processing, while the right hemisphere is often engaged in simultaneous and holistic processing.[36]

Experiments have shown that “Easterners see through a wide-angle lens; Westerners use a narrow one with a sharper focus.”[37] When observing the landscapes on Canton porcelain, the Chinese and Westerners literally use different sides of their brain, and therefore perceive and interpret them in a different way. The Chinese see a harmonious natural scene, interconnected, bound together by the ch’i; people from the West see a group of unrelated objects and draw no message from their relationship.

Summary

Chinese paintings and porcelain depicting landscapes do not try to represent nature. Rather, they represent the painter’s heart and mind, conveying the painter’s ch’i, or spirit. Differences in perception, combined with a lack of understanding of the symbolic meanings of the objects and their interrelationships have tended to undervalue the painted landscape scene on Canton porcelain. “The [Chinese] artist sought to depict an understanding of the unity of all existence and man’s harmonious place in it. On a more humble level, landscape scenes on Chinese ceramics convey this same view of nature.”[38] Canton blue-and-white porcelain illustrates the ancient scholars’ belief that all forms of life are interconnected and their appreciation of the beauty and balance of nature. The Chinese bureaucracy sought to project an image of Chinese society through the motifs on Canton porcelain, even though the symbolic meanings of those motifs were not understood by the customers in the West. It is hoped that we have brought some understanding to these issues, so that Canton porcelain will be better appreciated and get the respect it deserves.

Quoted in Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785–1835, 2nd ed., rev. (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1962), p. 74.

George L. Miller and Robert Hunter, “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2001), p. 135.

Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, p. 54.

Ibid., p. 55, quoting John Robinson, “Blue and White ‘India-China,’” Old-Time New England 14 (January 1924): 116.

Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, p. 19.

Ibid., p. 70.

Ibid., p. 78.

Doug Stewart, “Salem Sets Sail,” Smithsonian Magazine (June 2004), available online at www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/salem.html (accessed May 5, 2012).

Hiram Tindall, “The Canton Pattern,” The Magazine Antiques 108, no. 2 (August 1975): 230–32.

Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, p. 125.

Ibid., pp. 123–27.

Maxwell K. Hearn, personal communication, May 20, 2008.

Maxwell K. Hearn, How to Read Chinese Paintings, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, in association with Yale University Press, 2008).

Henry A. Crosby Forbes, Hills and Streams: Landscape Decoration on Chinese Export Blue and White Porcelain, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: The Foundation, 1982), p. 8.

Hearn, personal communications, May 20, 2008.

Quoting Maxwell Hearn in “Great Museums, China: West Meets East at The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” course given by Hearn at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, August 3, 2008 [hereafter “Great Museums, China”].

Hearn, How to Read Chinese Paintings, p. 7.

Chieh Tzu Yuan Hua Chuan, comp., The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (1679–1701), Mai-Mai Sze, ed., Bollingen Series (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1956), [facsimile edition] p. 6 (quoting the preface to the 1887 Shanghai edition).

Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. xvii.

Quoting Hearn in “Great Museums, China.”

Ibid.

Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, pp. 129–30.

Ibid., p. 131.

Hearn, How to Read Chinese Paintings, p. 4.

Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 117.

Ibid., p. 54.

Ibid., p. 286.

Department of Asian Art, “Scholar-Officials of China,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/schg/hd_schg.htm (October 2004; accessed October 15, 2012).

Department of Asian Art, “Landscape Painting in Chinese Art,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/clpg/hd_clpg.htm (October 2004; accessed October 15, 2012).

Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, p. 264.

Ibid., p. 220.

Ibid., p. 269.

Ibid., p. 52.

Ibid., p. 292.

Ibid., pp. 324–25.

Norman Doidge, The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science (New York: Viking, 2007), p. 301.

Ibid., p. 302.

Forbes, Hills and Streams, p. 8.