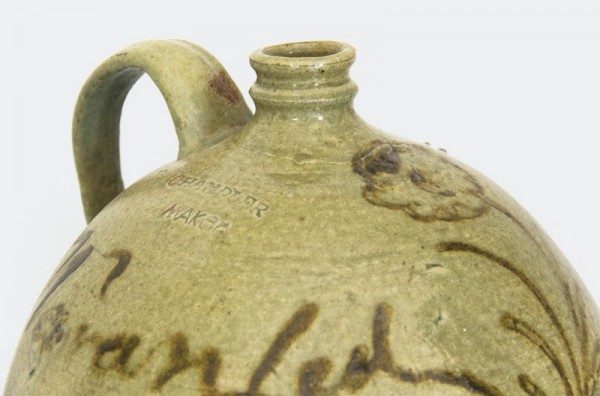

Detail of jug, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1847–1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Capacity mark: 3. Stamped mark: “CHANDLER MAKER” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Daguerreotype of Thomas Chandler Jr., Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1850. (Courtesy, William Robert Mathis, a direct descendant.)

Portrait of Elizabeth Wise Chandler, attributed to Joshua Johnson, ca. 1815, Accomack County, Virginia. Oil on artist board. 19 1/2 x 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Freeman’s Auctioneers and Appraisers, Philadelphia; photo, Elizabeth Field.) Elizabeth Wise Chandler was Thomas Chandler Jr.’s mother.

Plan of the City of Baltimore compiled from actual survey by Fielding Lucas Jr., 1822, improved 1836. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.)

Churn, Thomas Chandler Jr., likely Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory, Baltimore, Maryland, 1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". Incised: “Mitchel · Chandler / 1829” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The scene is believed to be the Mitchell Chandler homestead in Accomack. The handles, rim, and overall form are much like churns made by Henry Remmey while he was working for Henry Myers in Baltimore ca. 1825–1829.

Side views of the churn illustrated in fig. 5.

Incised inscription on the bottom of the churn illustrated in fig. 5: “Thomas M. Chandler / Maker / Baltimore August / 12 / 1829”

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Baltimore, Maryland, or possibly Richmond, Virginia, 1820s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

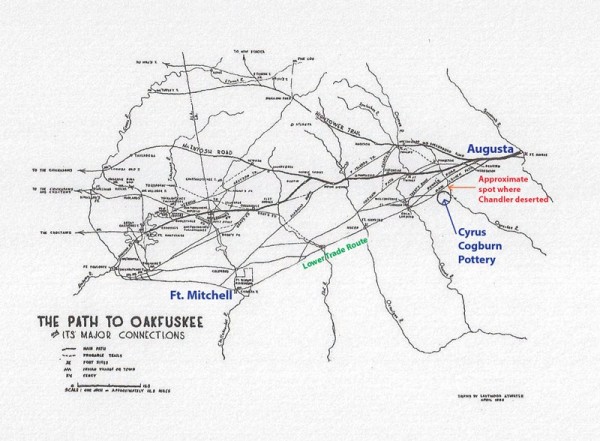

“The Path to Oakfuskee,” drawn by John H. Goff, reproduced in Georgia Historical Quarterly (March 1955): inserted between pages 4 and 5. The lower trade route between Augusta, Georgia, and Fort Mitchell, Alabama, is shown, with the parts pertinent to Thomas Chandler highlighted. The circle notates the proximity of the Cyrus Cogburn pottery to the lower trade path, which was used by the U.S. Infantry in March–April 1833. The arrow shows the approximate place of Chandler’s desertion. (Courtesy, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries.)

Detail showing production mark “C” on iron-slip alkaline-glazed stoneware jar from Edgefield District, South Carolina, attributed to Thomas Chandler, 1836–1840. (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) This mark is associated with Thomas Chandler at various production sites, but it has not been found in archaeology.

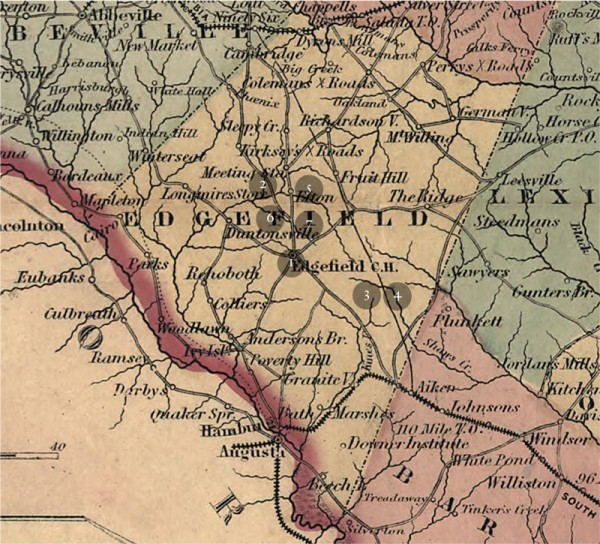

Sites of potteries where Thomas Chandler worked in the Old Edgefield District of South Carolina between 1835 and 1853, superimposed on J. H. Colton & Co.’s 1855 map of South Carolina.

1 38ED11, 1835–1837: Chandler appears to first work with Rueben Drake and Collin Rhodes at Pottersville.

2 38GN169, 1837–1838: Chandler is found working with John Isaac Durham north of Edgefield.

3 38AK495, early 1839: Chandler has moved to a site on Shaw’s Creek and begins experimenting with iron and kaolin slip decoration on alkaline-glazed pots.

4 38AK495, early 1840–1844: When Phoenix Factory is created as a partnership at Shaw’s Creek in early 1840, Chandler becomes primary turner and decorator of stoneware produced there. When the partnership dissolves in late 1840, Chandler remains at Shaw’s Creek until ca. 1844, likely working for Collin Rhodes. By 1844 he no longer turns pottery at site 38AK495, but decorates for Rhodes part time until about 1851.

5 38GN16, 1844–1848: It appears Chandler has opened and is working at “Chandler Site I.” This is near the Durham/Trapp/Chandler site 38GN169.

6 38GN169, 1848–1850: Chandler enters into partnership with John Trapp at the old Durham/Mathis pottery, now known as the Trapp/Chandler/Presley pottery, where he works for about two years.

7 38GN343, 1850: Chandler opens his second shop, “Chandler Site II,” about a mile south of site 38GN169 on the old Martintown Road. By 1853 it appears Thomas Chandler has left Edgefield and moved to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

Storage jar, John Landrum’s Horse Creek Pottery or Abner Landrum’s stoneware factory at Pottersville, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1821. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection; photo, Jan Todd.) This represents some of the earliest alkaline-glazed ware from Edgefield.

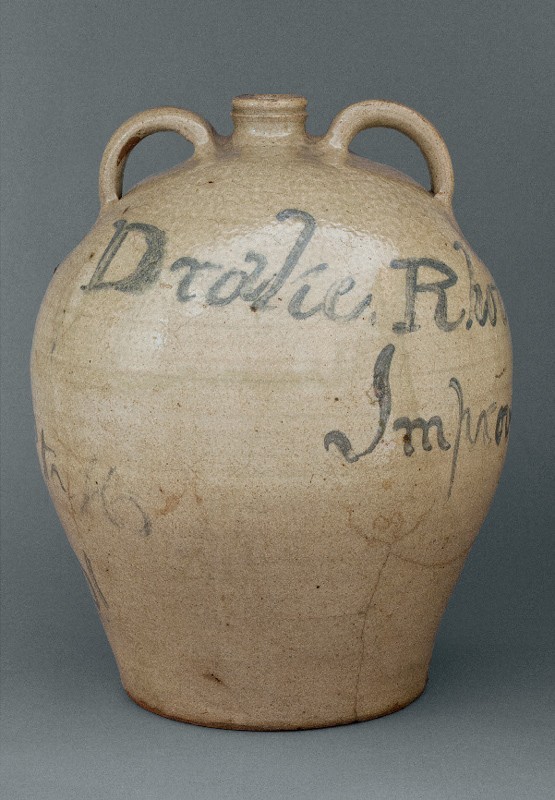

Two-handle jug, Rueben Drake and Collin Rhodes Pottery, Pottersville, South Carolina, 1836. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". Inscribed in cobalt: “Drake Rhodes & Co Improved Stoneware Edgefield Ct H S.C. 1836” (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

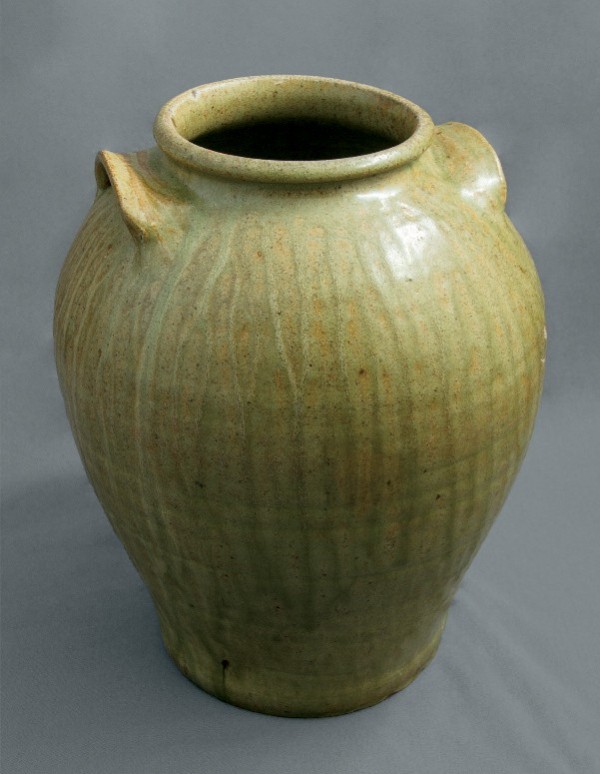

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1844. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17 3/4". Inscribed in iron slip: “Chandler / Maker / 1844”; on reverse, in iron slip: “Mr. B. Harland” (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) The handwriting appears to be the same as that on the 1836 jug illustrated in fig. 13.

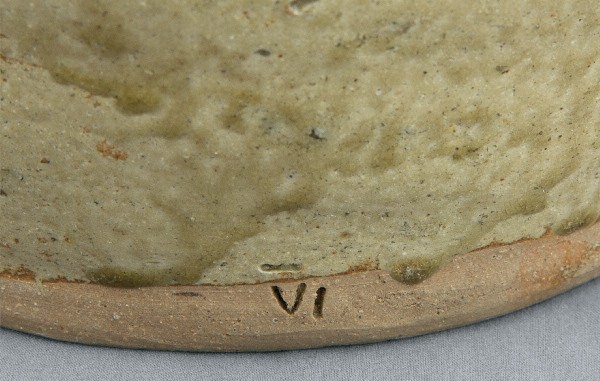

Detail of production/capacity mark, roman numeral VI. (Photo, Jan Todd.) This mark is attributed to Thomas Chandler at the Pottersville stoneware factory and the Trapp and Chandler Pottery location.

Detail of production/capacity mark roman numeral II. (Photo, Jan Todd.) This mark has been found at the pre–Trapp and Chandler site (38GN169).

Storage jar, detail of production mark oblate or elongated “C” near the rim, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1835–1840 (38GN169). Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". Production/capacity mark near base: “II” (see fig. 16). (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Production/capacity mark at base: “VI” (see fig. 15). (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler or John Isaac Durham, Edgefield District, South Carolina (site 38GN169), ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". Stamped capacity mark near base: “II” (see fig. 16). (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina (site 38GN169), ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". Production mark: oblate or elongated “C” (see fig. 17); production/capacity mark near base: “II” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina (site 38GN169), ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". Production/capacity mark: “III” partially filled in with glaze. (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) In this surviving example, Chandler had begun to transition his glaze toward celadon.

Detail of the production/capacity mark “II” on the jar illustrated in fig. 20.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1837. Iron-slip alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Three small “C”s are impressed equidistant around the rim and three additional roman numeral marks are at the base (see fig. 10); compare with the mark on the jug illustrated in fig. 24.

Spirits jug, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/4". Impressed mark: “PHOENIX FACTORY ED: SC / C” (Courtesy, Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Jar, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1837–1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/4". (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) Chandler adapted and developed the swag-and-tassel decoration from the Remmey family of potters of New York and Baltimore; this is one of his first examples decorated with iron slip.

Storage-jar fragments, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1837–1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) These fragments, found by ceramics historian Steve Ferrell at Shaw’s Creek, exhibit slip-trailed decoration that is remarkably similar to the delicate swag-and-tassel decoration in cobalt on the salt-glazed stoneware jar illustrated in fig. 8. See also fig. 38.

Stew pot, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1837–1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8". (Courtesy, Randy Windham; photo, Jan Todd.) This early stew pot presents iron-slip decorative elements that are some of the first developed by Chandler in Edgefield. One can see from this example that Chandler had not yet developed the right liquid consistency for his decorative slip.

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with brushed iron-slip decoration. H. 19 1/4". Incised: “Phoenix Factory”; “1840” (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) Compare the iron-slip brushed flowers between the handles on this example to the cobalt trailed flowers on the jar illustrated in fig. 8.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Shaw’s Creek/Phoenix Factory area, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1841–1845. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) With a shape more bulbous than ovoid, this approximately ten-gallon storage jar was likely produced after Phoenix Factory had dissolved. Based on the large volume of waster material at Phoenix Factory, it appears that Chandler continued potting at the site under the auspices of Collin Rhodes.

Storage jar, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1845. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Vivian and Gerald Gowitt; photo, Jan Todd.) In my opinion this example was made at the first site Chandler operated independently (38GN16), near Trapp and Chandler (38GN169). The iron-trailed sprigs match potsherds found at site 38GN16.

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1845–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Doug and Brenda Howard; photo, Louis Tonsmeire Studio.) Thomas Chandler began using two-color slip decoration and elaborated on the swag-and-tassel theme by 1840 while at Phoenix Factory. The design on this example is almost identical to the design on the jar illustrated in fig. 25, but the outline in white slip makes a bolder, more neoclassical statement.

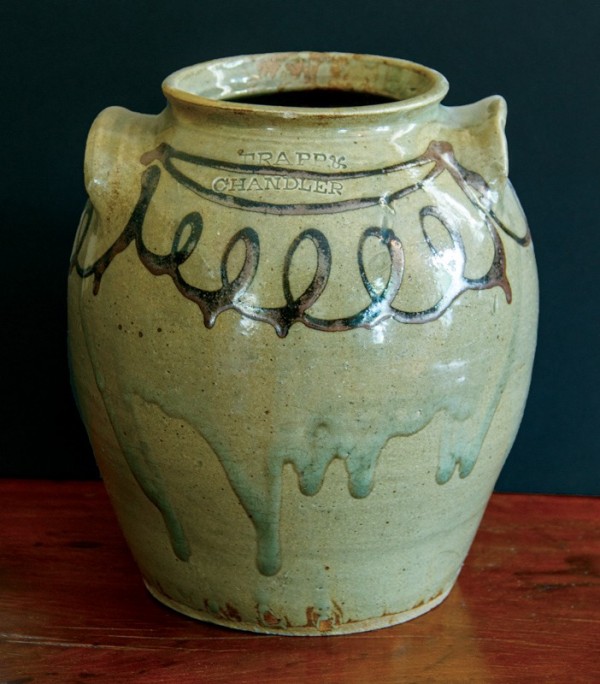

Storage jar, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1848–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". Impressed mark: “TRAPP & CHANDLER” (Courtesy, L. C. Lynch; photo, Jan Todd.) By 1848 Chandler was using draped lines with loops beneath, in iron or kaolin slip, as his primary decorative motif. The thick yet translucent celadon overglaze makes a stunning presentation.

Buttermilk pitcher, possibly eastern Texas, 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, John Lafoy; photo, Jan Todd.) One of the few slip-decorated stoneware examples surviving from the post-Chandler era, ca. 1860. After Chandler’s death, in 1854, only a handful of slip-decorated Southern stoneware examples were produced by potters in South Carolina or points west.

Mixing pan, William Morgan Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Crocker Farm Auction.) The squared pouring spout and the slab handles were adapted by Thomas Chandler. Compare the zigzag decoration to that on the jug illustrated in fig. 24.

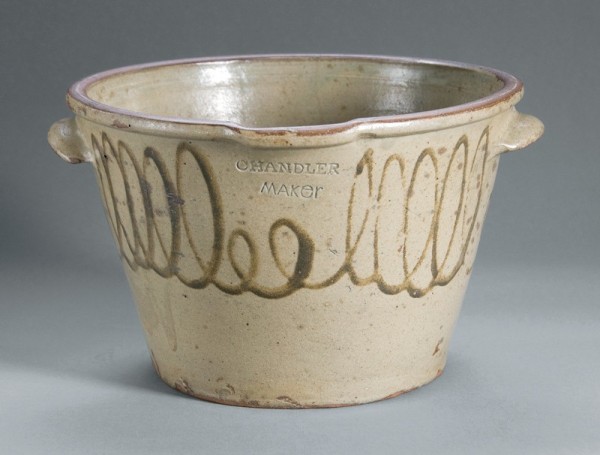

Mixing pan, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1848–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/4". Impressed mark: “CHANDLER MAKER”(Collection, Doug and Brenda Howard; photo, Louis Tonsmeire Studio.) Squared pouring spouts are commonly seen on Baltimore stoneware; they were not made in Edgefield prior to Chandler’s arrival.

Stoneware wasters, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, University of South Carolina, McKissick Museum; photo, Carl Steen.) Archeologist Carl Steen found these collapsed vessels on top of the waster at the Thomas Chandler Pottery during a survey in 1988.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. John Hoar; photo, Brewster Photography). A magnificent surviving example of Chandler’s work at Phoenix Factory. Here the kaolin is applied with a brush instead of a slip cup.

Storage jar, attributed to John Remmey III, New York or New Jersey, 1810–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". (Courtesy, Bruce and Vicki Waasdorp, American Pottery Auction.) This decoration matches the decoration on the Phoenix Factory jar illustrated in fig. 37.

Pitcher, Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1828. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Stamped: “BALTIMORE, / H. REMMEY” (Courtesy, Crocker Farm Auction.) The cobalt-trailed floral decoration is the same basic design that Chandler would use some twenty years later.

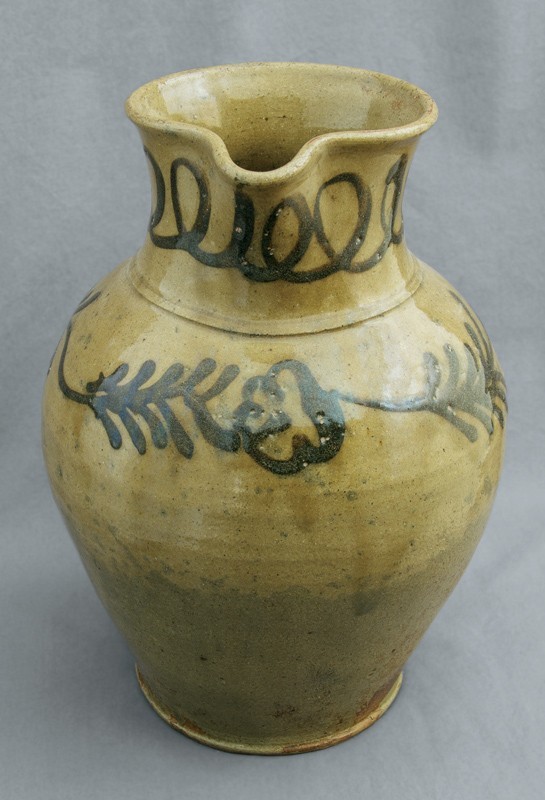

Pitcher, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1848–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Donny Taylor; photo, Jan Todd.) This wonderfully executed sprig-and-flower-head decoration is a Chandler adaptation of Henry Remmey’s design in Baltimore.

Detail of mark on a storage jar, David or Elisha Parr Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1820–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. Capacity mark, stamped within a circle of coggle-impressed teeth: “3” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Spirits jug, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1850–1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Capacity mark: “3”; stamped signature: “CHANDLER / MAKER” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) Chandler developed his own technique for indicating capacity by evolving the coggled circle on the jar illustrated in fig. 41 into a large, slip-cup-executed cartouche surrounding a slip-drawn freehand arabic numeral. In some instances he framed the capacity with a daisy flower head instead of a cartouche. This was done in a kaolin or iron slip. After 1840 Chandler used this method to indicate gallons, as he no longer marked his ware with roman numerals, slashes, capacity stamps, or incised arabic numerals. This is in stark contrast to his contemporaries, who continued to use slashes, punctuates, crosses, and dots to indicate gallons until the 1860s.

Jug, Collin Rhodes Stoneware Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1844–1851. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". Capacity mark: “3” (Courtesy, Sam Phillips; photo, Jan Todd.) This jug was decorated by Chandler, who decorated virtually all of the ware produced at this pottery. Note the capacity surrounded by a daisy flower head.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17". Inscribed in slip: “Shaws Creek / Pottery / 1839” (Courtesy, Sam Phillips; photo, Jan Todd.) This is an early example of a Chandler presentation piece, bearing a type of flower decoration he used primarily for Collin Rhodes. The sprigs, bell flowers, and daisy heads are all Baltimore-influenced Chandler designs. The writing is in his hand. This establishes that Chandler had mastered the art of slip decoration on alkaline-glazed stoneware by 1839.

Water cooler, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 31 1/4". Stamped: “PHOENIX FACTORY ED:SC” on reverse. (Courtesy, High Museum of Art, Purchase in honor of Audrey Shilt, President of the Members Guild, 1996–1997, with funds from the Decorative Arts Endowment and Decorative Arts Acquisition Trust.) This mammoth water cooler was possibly a presentation to slaves in the Chandler household. The drawing on this surviving example is very similar to the drawing on the Chandler Baltimore churn illustrated in figs. 5–7.

Detail of the water cooler illustrated in fig. 45, showing the scratch decoration of the facing slaves. Compare the hands and facial features with the incising of the Baltimore churn illustrated in fig. 5.

Storage jar, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1845–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 29". (Courtesy, Sam Phillips; photo, Jan Todd.) This massive jar with an agglutinated glaze and four handles has an unusual double-rolled rim, apparently adopted by Chandler from his time working with Remmey in Baltimore.

Water cooler, Baltimore Manufactory, Baltimore, Maryland, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Impressed mark: “H. Myers” (Courtesy, Crocker Farm Auction.) Attributed to Henry Remmey while he was working for Henry Myers. The unusual double-rolled rim was adapted by Chandler and used by him sporadically in the Edgefield District.

Detail of a storage jar, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1850–1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Stamped on the shoulder: “FLINT WARE” (Courtesy, L. C. Lynch; photo, Jan Todd.) Stamped “flint ware” examples are some of the highest-fired stoneware made by Chandler.

Jug, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 19". Inscribed in dark slip on shoulder: “Waranted”; “1850”; and “5” within a cartouche; stamped: “CHANDLER MAKER” (Courtesy, L.C. Lynch; photo, Jan Todd.) This five-gallon spirits jug is decorated with the Chandler daisy flower head.

Water cooler, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 20". Stamped: “CHANDLER MAKER” (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) This approximately fifteen-gallon vessel displays a delicate slip-trailed kaolin decoration as well as a classic celadon glaze. The sprig-and-flower-head decorations on this piece are nearly identical to those on the jar illustrated in fig. 44 right, which were executed some thirteen years earlier.

Harvest face vessel, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1845. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11". Stamped on reverse, near center top beneath handle: “CHANDLER / MAKER” (Private collection; photo, Philip Wingard.) The bell handle, nipple spout, and double-collar spout, not to mention the facial expression, are distinctive. I believe this was Chandler’s personal drinking jug, and remained in his possession until his death.

Reverse side of the harvest face vessel illustrated in fig. 52. (Photo, Philip Wingard.)

Face-vessel fragment, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Dr. John Hoar.) The true-to-life eyes are like those executed on other face vessels of 1838–1852 by Thomas Chandler. In the Edgefiield District, no fragments or surviving face vessels from a period prior to 1838 are known to exist. Chandler brought the idea of the face vessel with him, having learned about the form while in Baltimore, most likely from Henry Remmey.

Face vessel, attributed to the Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. John Hoar; photo, Dr. John Hoar.) This face vessel was recovered from the marsh of the Charleston harbor in the 1920s. Based on the archaeology from site 38GN169, where Chandler worked prior to Shaw’s Creek and Phoenix Factory, dipping large sections of vessels in a contrasting iron wash was being done at this Martintown Road site. This decorative technique was first developed here by Chandler and others prior to their arrival at Shaw’s Creek.

Face harvest vessel, attributed to the Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1845–1848. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Carl Steen.) The nose, mouth, and eyes are very similar to those on the signed Chandler example illustrated in fig. 52. Also shared are the small nipple spout and double-collar spout. There is applied iron wash at the base of the missing bail handle.

Face jug, Trapp and Chandler Pottery or possibly Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, attributed to Thomas Chandler, 1848–1854. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, David Good; photo, Carole Wahler.) Traces of blue rutile, a characteristic of alkaline-glazed North Carolina stoneware, and the darker clay body and glaze indicate that this jug might have been made in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, during Chandler’s short tenure there.

Face harvest vessel, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1829, Chandler school. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg, Abby Aldrich Folk Art Museum.) There are at least three known lead-glazed earthenware face harvest vessels made by the same potter. That these vessels have facial features very closely related to the known signed Chandler example, as well as the four unsigned stoneware examples attributed to Chandler, suggests that they were likely made in Baltimore and that Chandler either made them or was trained by the potter who did.

Face harvest vessel, Chandler school, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9". (Courtesy, David Good; photo, Carole Wahler.) This example has a strong provenance to Baltimore.

Face harvest vessel, Edward Stone Pottery, Buncombe County, North Carolina, 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Stamped: “J. H. Stone” (Courtesy, Donnie Garrett; photo, Jan Todd.) James Henry Stone, son of Edward Stone, was born in Buncombe County in 1847.

In the winter of 1980, during a tour of homes in my town, I saw for the first time an alkaline-glazed jug. It was dark olive green with rivulets of dripped glaze running down on all sides. The glaze reminded me of the candles my mother loved that would melt down to nothing during supper and, in the process, cover the old wine bottle we used for a holder with layers of different-colored dripped wax. The alkaline-glazed jug was from a region in North Carolina known as the Catawba Valley, and its elegance struck me to the core. “It is unfortunate,” I said to my host, “that such a wonderful example of nineteenth-century stoneware could not have been made in South Carolina.” “You’re so wrong,” my friend informed me. “Extraordinary stoneware was made in South Carolina, at a place called Edgefield” (fig. 1).

A few years later, I found myself face-to-face with an example of Edgefield stoneware. It was a honey-colored, two-gallon storage jar decorated with a large number 2 inside a scalloped cartouche, all in a dark slip under a glossy glaze. The decoration appeared to have been applied with a brush. The simple design had a mystery to it that impelled me to look for more examples made by the same hand, that of potter Thomas Chandler. Being a South Carolina native, I had studied my state’s history, but had never been taught about South Carolina–made stoneware fashioned during a time when farms and families depended on it, or about its significance to commerce and industry or craftsmanship. How could historians have ignored such important utilitarian artifacts so essential to our ancestors’ lives? More important, to me, who was Thomas Chandler, and where did he learn to pot?

In this article, I explore Thomas Chandler’s background and the forces that led him from his early beginnings as a potter in Baltimore, Maryland, to become one of the premier potters in Edgefield, South Carolina. I will show that many of the decorative elements in the Mid-Atlantic salt-glazed traditions Chandler was exposed to during his training in Baltimore are later manifested in his considerable body of alkaline-glazed stoneware. It is my contention that Thomas Chandler introduced the face vessel to Edgefield—a form adopted and adapted by many of the African-American potters working in the district during the mid-nineteenth century.

Thomas Mitchel Chandler Jr.’s Early History and Training

Thomas Mitchel Chandler Jr. (fig. 2) was born in 1810 to a family of tradesmen and farmers on the Eastern Shore of Virginia in Drummondtown (now Accomack), Virginia.[1] The Chandlers were industrious in Drummondtown in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Thomas Chandler Sr. was born there about 1780 and, when he was orphaned in 1796, an uncle, Littleton Chandler, became his guardian. The following spring, at age seventeen, Thomas Sr. was sent to Baltimore, where on May 18, 1797, he was bound out to Caleb Hannah, an established Windsor chair maker.[2] After completing his apprenticeship at the age of twenty-one, he married Elizabeth Wise in Baltimore on July 16, 1802 (fig. 3), and later that year returned with her to Drummondtown to ply his trade as a chair maker.[3] On August 30, 1803, he took on orphans Jacob Phillips and John Drummond as apprentices.[4]

Thomas Sr. and his brother Elisha (who had also apprenticed as a Windsor chairmaker in Baltimore) may well have taught their older brother Mitchell the trade, because Mitchell Chandler is listed in the 1850 Accomack census as a chairmaker, aged seventy, living with his older sister Rosey Chandler Fitzgerald, a widow.[5] By 1817 Thomas Sr. and his family were back in Baltimore, perhaps influenced by the Tariff Act of 1816 and its positive economic effect on local manufacturing.[6]

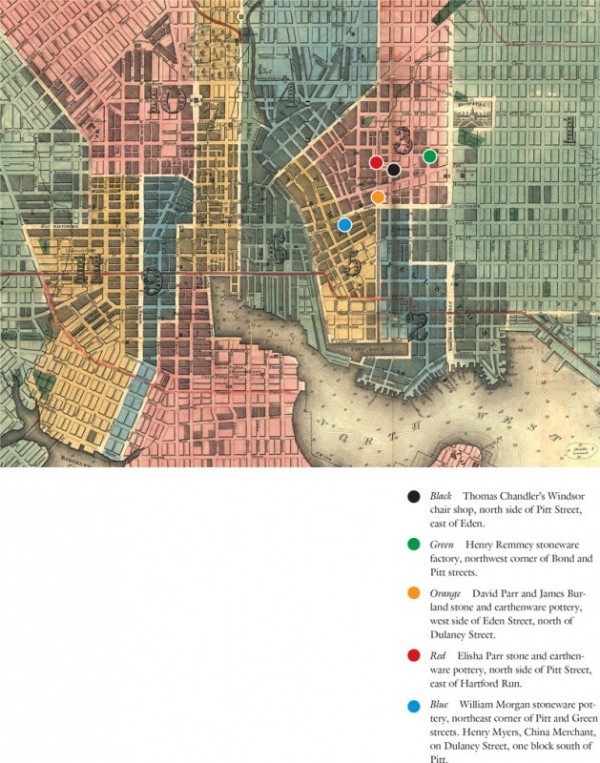

Thomas Sr. prospered in Baltimore during this period. He had a portrait painted of his wife (and, perhaps, one of himself) by the freed black artist Joshua Johnson.[7] Thomas Sr.’s Windsor chairmaking shop was on the north side of Pitt Street, near Eden Street. In C. Keenan’s Baltimore Directory for 1822 & 1823, there are four important pottery manufacturing concerns listed very near this location: master potter Henry Remmey had a stoneware shop on the northwest corner of Bond and Pitt streets; potters Thomas Morgan and William Amoss were on the corner of Pitt and Green streets; potter David Parr was on Eden Street, and his brother Elisha Parr was on Pitt Street; and the important Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory (same shop as the Remmey shop) was on Pitt and Bond. A map of Baltimore by Fielding Lucas Jr. (fig. 4) places Thomas Sr.’s Windsor shop within a block or two of these four potteries, in the midst of one of the most dynamic stoneware-making environments in the country. In addition to stoneware, Morgan and Amoss, the Parr brothers, and Henry Myers were also manufacturing earthenware in 1822.[8]

The Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory on Pitt and Bond streets had been established circa 1812 by William Myers, a china merchant who hired master potter Henry Remmey Sr. from New York to run the operation (which Remmey did until about 1829).[9] By 1822 Henry Myers, nephew to William, had a china retail outlet on Baltimore Avenue, where the citizens of Baltimore, as well as young Thomas Chandler Jr., could see the finished products of all the major potters working in the area.[10] Although too young to become an apprentice when he arrived with his family in Baltimore in 1817, he was free to glean knowledge from any of the stoneware makers, perhaps doing odd jobs and chores for them in exchange for the opportunity to learn the craft.

The recent discovery of a salt-glazed churn signed and dated by Thomas Chandler confirms that he did indeed make stoneware in Baltimore, Maryland. The churn is incised with the scene of a farmhouse and a woman churning butter among a highly detailed landscape of trees, bushes, and outbuildings, all accented with brushed cobalt blue (figs. 5, 6): “Mitchel Chandler” and “1829” are incised in script on the upper body; on the bottom is the signature “Thomas M. Chandler / Maker / Baltimore / August / 12 / 1829” (fig. 7). Thomas Chandler would have been eighteen or nineteen years old when he made this churn, the age at which most stoneware apprenticeships began. Much as a hand-stitched sampler reflects the skills attained by a young girl in finishing school, the churn represents the skills Chandler had attained in his training to become a potter:fine turning, glazing,firing, decoration, form, and function. The churn appears to have been a presentation piece to Chandler’s uncle and his sister, Mitchell Chandler and Rosey Chandler Fitzgerald; it descended in the family and had been in Accomack for many years.[11]

It is clear that from about 1817, when he arrived in Baltimore, until about 1829, when he left, Thomas Chandler Jr. learned all the details necessary to become a master potter. It is likely that he made and/or decorated additional stoneware produced in Baltimore from 1825 until 1829, but examples have not been firmly identified. Yet in 1829, perhaps because his father was no longer supporting the family, Thomas Jr. applied for a grocer’s license in Baltimore.[12] According to Matchett’s Baltimore City Directory for 1831, Chandler’s mother was operating a grocery store on “Monroe Street near Spring” to support the family.

On October 22, 1831, at age seventeen, Thomas Jr.’s younger brother George was bound out and apprenticed to Henry Myers to become a stoneware potter.[13] George’s apprenticeship verifies a strong bond between the Chandler family and Henry Myers, one of the most important figures in Baltimore stoneware at that time and situated near the Chandler household.

The great potter Henry Remmey had left Baltimore about 1829, and potter David Parr Sr. died in 1832 from cholera.[14] Between late 1829 and 1832 it is possible that Thomas Chandler was making stoneware with John P. Schermerhorn and/or other potters in Richmond, Virginia (fig. 8). During this period, several Baltimore potters had matriculated through the Richmond and Henrico potteries, among them Thomas Amoss (see, in this volume, Kurt C. Russ et al., “The Remarkable 19th-Century Stoneware of Virginia’s Lower James River Valley,” pp. 200–258). While Chandler’s name has yet to be firmly associated with the Richmond and Henrico potteries, the 1830 census for Henrico County, Virginia, records a twenty- to thirty-year-old man living with Schermerhorn. This might refer to Thomas Chandler, who would have been approximately twenty-one years old. An intriguing clue to this possibility is the presence of a “Chandler Road” in the vicinity of the Henrico County factory complex where other Baltimore potters are known to have worked.

By 1830 the advantage American manufacturers maintained against English imports ended with the repeal of some of the stricter tariffs on English goods, whereupon England renewed sending cheaper finished goods to America. Port manufacturing centers such as Baltimore and Richmond were affected immediately by the sudden increase in lower-priced imported stoneware. Some Baltimore stoneware makers began to close their shops.[15] Perhaps due to economic conditions, by late 1832 Thomas Chandler had moved to Albany, New York, an area that had close connections to both Richmond and Baltimore.[16]

The frontier was one market not affected by the economic chaos in the east. The expansion of the backcountry into Alabama, Florida, and Georgia increased demand for stoneware and related products, and it is possible that finding a place to produce stoneware near the edge of the frontier was on Chandler’s mind. After completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 created a continuous waterway from New York City to the Great Lakes, Albany was situated as a place from which to head west, and perhaps Chandler moved there in 1832 for this reason. It is possible he worked for a short time for Paul Cushman, who was the owner of several major pottery factories in Albany in the 1820s and early 1830s. However, perhaps because he had no other prospect for employment, on December 14, 1832, Chandler enlisted in the U.S. Army at Albany, joining the 4th Infantry Company A under Major Dade for a term of five years. His enlistment records describe him as 5' 5" tall, with blue eyes, light hair, and a fair complexion. His profession is listed as musician, which suggests he had abandoned, at least temporarily, the avocation of stoneware potter, or perhaps being a musician paid a higher enlistment bounty; regardless, joining the army brought Chandler south.

Thomas Mitchel Chandler Goes to Edgefield

In November 1832 a state convention in South Carolina passed the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared that the federal tariff acts of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and unenforceable in South Carolina and would not be obeyed by the state after February 1, 1833.[17] The tariffs were designed to improve manufacturing in America but hurt the centuries-old exchange between England and South Carolina of raw material for finished goods. By February 1833 President Andrew Jackson, a native of South Carolina but a staunch Federalist, had pushed a bill through Congress authorizing the use of force against South Carolina if the state refused to comply with federal law. Concurrently, led by Henry Clay, Congress passed significant reductions in the tariffs, which Jackson also signed into law, thereby essentially ending the conflict.[18]

With this crisis over, Jackson turned his attention to the growing Indian rebellion in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia. In 1832 Augusta, Georgia, was on the edge of the southern frontier, at the head of the Meriwether Trail and the Indian trade routes leading southwest into southern Alabama and Seminole and Creek Indian lands. Several Indian nations in the southeast were rising up against the United States in a dispute over land that the federal government considered U.S territory, ceded by Spain after the Louisiana Purchase. In late December 1832 Chandler’s infantry company was deployed to Augusta and arrived by January 20, 1833.[19] However, the resolution of the nullification issue in February changed the status of the 4th Infantry and, by early March, it was ordered to Fort Mitchell, Alabama, in support of a U.S. response to the Indian conflict.

On March 30, 1833, 4th Infantry Company A left the Augusta Arsenal headed for Fort Mitchell, Alabama, and five days later, on April 5, Chandler deserted and was AWOL for six months, until October 5.[20] A pottery established in 1818 by Cyrus Cogburn in southeast-central Washington County, Georgia, was within a mile of the Indian trade route the infantry used to march to Fort Mitchell during the first quarter of the nineteenth century.[21] The route, also known as the Meriwether Trail, was the most direct one from Augusta to Fort Mitchell.[22] Based on a study of the number of days it typically took an army regiment to march this distance on the trail, I have concluded that the area near Cogburn’s pottery is approximately where Chandler deserted (fig. 9).[23]

Cyrus Cogburn was in fibefore 1818, working with Abner Landrum at Pottersville and possibly with John Landrum at Horse Creek. By 1827 he had moved to Upson County, Georgia, but the Washington County pottery he established in 1818 was still in operation in 1833. If Chandler did indeed work there during his desertion, learning about the alkaline glaze may have earned him acceptance as a potter in Edgefield a few years later. Fragments marked with a small incised “C” have been found at the site and might be associated with Chandler’s work there.[24] There is a strong indication that Chandler used the production mark “C” on his ware at Pottersville, Trapp and Chandler, and Shaw’s Creek in Edgefield District (fig. 10).

After Chandler rejoined his company in October 1833, he was held in confinement for a full year at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, three miles south of Savannah. He was tried in a court-martial proceeding and was acquitted, but remained in confinement. A month later Chandler was granted a transfer to the 2nd Artillery Regiment, Company E, stationed at the Augusta Arsenal. This transfer, which took effect upon Chandler’s release from confinement in November 1834, placed him back at the Augusta Arsenal.[25]

From November 1834 until the early spring of 1836, Company E was held in reserve at the Augusta Arsenal, giving Chandler his second opportunity to work with the potters of the region, especially in the Edgefield District. In the spring of 1836, however, several 2nd Artillery companies, including Company E, were ordered south to protect the flank of the forts and posts on Florida’s west coast. Company E saw action on June 9 at Micanopy, Florida, when Seminole Indians led by Chief Osceola attacked the post. It was likely in this battle that Chandler was wounded in his thigh, as his widow stated years later in her claim for pensioner’s status in 1857.[26] In the two years between January 1835 and February 1837, nine officers and 103 men of the 2nd Artillery were killed in action, or died of wounds received or disease contracted in Florida.[27]

Chandler’s second and third absences from duty occurred in 1836 and were relatively brief: July 14–August 12 and November 8–December 4. They occurred shortly after the action at Micanopy and were likely for recuperation rather than desertion, as I can find no record of Chandler being confined or disciplined for them.[28] Chandler’s artillery captain, C.S. Merchant, officially discharged him on July 7, 1837, the result of “inabilities of a local nature from injuries received while in the service of the United States,” and he listed Chandler’s occupation as stoneware potter.[29] This would indicate that between his enlistment in 1832 and his discharge in 1837 Chandler had found his way back into the fraternity of stoneware potters. According to his service record, Chandler’s last absence occurred on October 10, 1837, after his official discharge. The final notation on Chandler’s service record was made on July 10, 1838, just nineteen days before his marriage on July 29 to eighteen-year-old Margaret Durham, daughter of Edgefield potter John Isaac Durham.[30] Apparently Thomas Chandler and the Army had parted ways on good terms.

Thomas Chandler Pottery Sites in Edgefield

I believe Thomas Chandler made his first appearance in Edgefield in the mid-1830s, but it is difficult to pinpoint where he first worked. The map presented in figure 11 provides an overview of the locations where Chandler is known to have produced or decorated stoneware. The absence of decorated stoneware in the Edgefield District before 1836 is good evidence that he brought his decorating method and distinctive fluid script to the area (fig. 12).[31] Two presentation pieces dated 1836 have pronouncements written in cobalt blue in what I believe is Chandler’s script.[32] The Drake and Rhodes jug (fig. 13) and the Hiram Gibbs jar (not illustrated) are the first known examples of Edgefield stoneware to have any kind of slip applied for use other than glazing. Most ceramics historians accept that Chandler was working in Edgefield by 1838, but on the basis of these two presentation examples, I believe he was there in 1836.[33] For comparison, a signed “Chandler Maker” jar, dated 1844, confirms Chandler’s distinctive script (fig. 14).

Thomas Chandler Production Marks in the Edgefield District

A distinctive characteristic of Edgefield District stoneware made during the first and second quarter of the nineteenth century is the production mark. These marks were used by both slave and non-slave potters and they help us identify potters and their movement from site to site. Most itinerant potters impressed their mark near the base edge of the pot, but occasionally marks were placed near the rim.

The marks usually had two functions: to identify ware turned by a specific potter so the shop owner could monitor productivity; and to indicate capacity. Most marks were either stamped letters, symbols, and punctuates, or cursive slashes, letters, dots, and symbols. There were also stamped roman numerals ranging from I to XX, usually with a crossbar at the top or bottom.

While Thomas Chandler was a production potter in Edgefield at Pottersville and the pre–Trapp and Chandler site during the period 1836–1838, he primarily used stamped roman numerals as his production mark (figs. 15, 16). I base this finding on a comparison of surviving ware attributed to him with sherds collected from these sites as shown in the two major archaeological reports on Pottersville and the report by Gerald K. Landreth on the Trapp and Chandler site. I also studied sherds from these sites collected by Steve and Terry Ferrell.[34] Moreover, at the pre–Trapp and Chandler site, circa 1837, he sometimes used an oblate or elongated “C” (figs. 17-22). By the time he was at Shaw’s Creek and Phoenix Factory, circa 1838–1840, he was using production marks rarely, with the exception of a deeply impressed lowercase “c” as well as some abstract symbols on the earliest decorated examples (figs. 23, 24). After he left Shaw’s Creek, about 1844, he did not use production marks at all, but had begun signing his ware “Chandler Maker.” Confusing the matter is the fact that not all surviving stoneware made by production potters during this period display production marks. Also, some surviving pottery examples display more than one production mark, sometimes multiples of the same mark.[35]

At least three potteries on the old Martintown Road north of Edgefield were in operation between 1830 and 1850, and Chandler worked at all three. By late 1837 I believe he was working at site 38GN169 with Durham and others (later known as the Trapp and Chandler Pottery) (see fig. 11). From circa 1844 until about 1848, Chandler worked at a pottery a short distance away (Chandler Site I, or site 38GN16), where he first attempted to produce stoneware on his own.[36] In 1848, at site 38GN169, Chandler entered into a partnership with the Reverend John Trapp, which lasted for about two years, until 1850. From circa 1850 to 1853 he operated his own pottery (Chandler Site II, or site 38GN343), which was about a mile south down the Martintown Road.

At site 3GN343, Chandler signed the majority of his work and no production marks have been found archaeologically.[37] Marks representing shop owners are usually found as letters stamped near the rim, spout, or base and are not considered production marks. For example, the following letter marks found at the Trapp and Chandler Pottery and on existing ware represent the potters: “ID” for John Isaac Durham; “M” for Robert Mathis; and “P” (possibly for John Presley).[38]

After a comprehensive study of this material, I conclude that Thomas Chandler used roman numerals as his most common production mark. In most cases the roman numerals were also used to indicate capacity (such markings are also found at Pottersville).[39] Another mark previously mentioned—a deeply impressed “C” stamped in different places and in a variety of patterns—is known from existing ware made at several Edgefield sites. Although it has not yet been found in site archaeology, I consider this to be a Chandler production mark.

Chandler’s marriage into the Durham family in 1838 placed him in the midst of the primary potters at Pottersville and the Martintown Road pottery during the 1830s: Rueben Drake, John Isaac Durham, Amos Landrum, Robert Mathis, John Presley, and Collin Rhodes. By 1838 I believe Chandler had left the Martintown Road area where he had been working with Durham and others, and began working at a pottery established on Shaw’s Creek south and east of Edgefield. There he most likely was working with Mathis, Durham, and Presley. A copy of the Ramey & Hughes Ledger, Pottersville, South Carolina, shows that by January 1, 1839, Mathis was at Shaw’s Creek producing stoneware that the Pottersville operation, in at least one instance, shipped to Union, South Carolina, for him. Collin Rhodes was not yet at Shaw’s Creek, as he is listed as the overseer of the Pottersville operation for the entire year 1839.

At Shaw’s Creek, Chandler began the experimentation process needed to master the art of decorating alkaline-glazed stoneware (fig. 25). Fragments found by Steve Ferrell at the site are decorated in early, simple motifs (fig. 26). One of the motifs, the swag-and-tassel, remained in Chandler’s repertoire throughout his career as a potter. Some of the early ware from Shaw’s Creek looks very much like ware from Pottersville, having a very light or white clay body and a translucent glaze; however, early Shaw’s Creek ware is sometimes decorated, and the contrast of dark iron slip against a light background demonstrates a disciplined training and execution of design. It is here at Shaw’s Creek that Chandler first implemented a unique decoration that I believe mimics an artillery cannon blast (fig. 27).

Chandler’s ability to decorate stoneware at Shaw’s Creek earned him significant recognition. By 1840 he was part of a group of potters working at a major stoneware enterprise known as Phoenix Factory (3AK495), literally built on top of the Shaw’s Creek site (fig. 28). Presumably the location of the factory was chosen for its access to the newly built railroad that ran from Charleston to Hamburg, South Carolina. For the first time, many of the major Edgefield pottery concerns are working together, and it is at Phoenix Factory that Chandler might have shared, to a limited degree, his knowledge of decorating stoneware with such potters as Collin and Milton Rhodes, John Isaac Durham, William Durham, Robert Mathis, and Amos Landrum. After a tremendous one-year run of stoneware production that included some of the most beautiful stoneware ever produced in America, the partnership known as Phoenix Factory ended. Whereas only a few surviving decorated stoneware examples in the Edgefield District can be dated pre-1840, many can be attributed to Phoenix Factory during the year it was in operation.

Most collectors and ceramics historians agree that Chandler was the principal turner at Phoenix Factory. Virtually any form Chandler had seen or produced in Baltimore during the 1820s was replicated by him during his time in the Edgefield District. His output included colossal water coolers and huge four-handled storage vessels along with smaller, intricately decorated milk pans, buttermilk pitchers, and bowls. It is here that he likely produced the first face vessel in the district. This varied and dynamic production was in stark contrast to what had been made in Edgefield in the previous twenty-five years.

Based on archaeology and the vast number of fragments found at the Shaw’s Creek/Phoenix Factory site, Chandler must have remained there for a few years, making and decorating stoneware most likely for Collin Rhodes (fig. 29). By about 1844 Chandler can be found in the Kirksey Crossroads area again near the Trapp and Chandler site, at a pottery site designated 38GN16 (Chandler Site I). He worked there for about four years, making a variety of vessels (fig. 30). Most of the vessels attributed to this site are decorated with an intermittent wreath or sprig, some with loop and swag, others with a broken-stem flower. In addition, some of the pots are decorated with capacity numbers surrounded by a cartouche, mainly in a dark slip. In 1848 Thomas Chandler moved a short distance to the old Presley/Mathis/Durham pottery on Martintown Road (site 38GN169), where he formed a partnership with the Reverend John Trapp. Chandler found the clays north of Edgefield to be very suitable for stoneware, containing more feldspar and iron and less alumina than the kaolin clays being used in the lower part of the district (figs. 12, 25). Whereas kaolin clays could be fired at a high temperature, they lacked elasticity, which partly explains the dearth of large vessels made during the early period of stoneware manufacture in the Old Edgefield District, when a higher percentage of kaolin clay was being used. At the Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Chandler had a tremendous run of making beautiful functional stoneware from about 1848 until 1850 (figs. 31, 32).

While still operating the Trapp/Chandler site in 1850, Chandler built a new kiln and pottery about a mile south. This site, 38GN343 (Chandler Site II) was built on a high ridge. The placement of his kiln on a ridge may have produced a better draw or draft for the chimney, allowing for a higher firing temperature. This perhaps helped Chandler achieve “Flint Ware” status, his latest experiment in making stoneware. He advertised the business and boldly stated that his ware was warranted from defects, the ware being so marked. For two years at this site, Chandler produced some of his best stoneware, often glazed with true celadon, decorated again in white frilly kaolin and bold, brushed-iron strokes, and fired to a high-pitched ring, becoming the ultimate utilitarian product, beautiful, durable, and useful.

Thomas Chandler and his family left Edgefield in late 1852. Perhaps a connection with the Partlow family brought them to North Carolina’s Steele Creek Township, just across the state line from York County and Fort Mill Township near the Catawba River. I believe Chandler’s mother-in-law, Nancy Durham, who according to the 1860 South Carolina census was born in York County, was the daughter of Boswell (Bozel) Partlow, who held at the time of his death in 1845 a large estate and several large tracts of land on the Catawba River near the state line and in both townships.[40] It is noteworthy that the last shop Chandler opened and operated (38GN343) was one mile south of the Trapp and Chandler Pottery (38GN169) in the Edgefield District, next to a Partlow homesite and probably on Partlow land.[41] The land that the Chandler family settled on in 1853 in North Carolina was very near the Partlows.[42]

A deed of trust executed in the Edgefield District between Thomas Chandler and his wife, Margaret, in February 1852 indicates that Chandler had become ill or to some extent was incapacitated. In moving his tangible assets to his wife and children, he was limiting any loss that might occur against his estate (his use of the phrase “notwithstanding improvidence or misfortune” suggests that he was expecting God’s wrath or bad luck). Four slaves—Simon, Ned, John, and Easter—were included in his estate, as were a large road wagon and four mules, two two-horse wagons with four mules, one mare, and the household furniture.[43] Although it is unclear what prompted Chandler to execute this deed of trust, it might have had something to do with the drowning of his five-year-old son, Thomas H. Chandler, in 1850.

A coroner’s inquest into the death of this son occurred on Wednesday, September 11, 1850, “at the Chandler house and the old pottery” three days after the incident.[44] Fourteen neighborhood men came to Chandler’s home to view the body and to determine the cause of death. One of them was John Partlow. According to Chandler’s account, after realizing his son was missing on Sunday evening, he immediately began a search. He found his son lying face down in a hole of water about five feet deep. Stewart Durham reported that Chandler, carrying his son and both soaking wet, came up to the house where they tried to revive the boy. There was a red mark above the right eye of the child, but otherwise no signs of violence. It is of interest that there is no mention of Chandler’s wife or any of the other children at the inquest with the exception of his eldest daughter, Caroline, who was eleven. She witnessed her father pull his son from the small pond of water. Francis Devlin, listed in 1850 as a potter next door to Chandler, is also mentioned in the inquest. The death was ruled accidental.[45] Both Devlin and Stewart Durham, who was a few doors down, likely worked at the Trapp and Chandler Pottery.[46] The death of his son at the Trapp/Chandler site might have prompted Chandler to move to a new location (38GN343), building a kiln next to the Partlow homesite a mile south on Martintown Road.

Thomas Chandler died on July 23, 1854, in the Steele Creek community of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Records indicate he had moved there from Edgefield by January 1853.[47] Because he died without a will, Chandler’s widow, Margaret, and her brother William Durham were administrators of the estate. After searching through hundreds of records it does not appear that Chandler owned any land in North Carolina or South Carolina. Although his deed of trust showed he owned four slaves, none was listed in his estate at this time, suggesting all were given their freedom. Manumitting slaves was a Chandler family tradition, as well as a common practice in Accomack County, Virginia, in the first half of the nineteenth century.[48]

A free black man by the name of John Chandler was making pottery in Texas at the Guadalupe Pottery, owned and operated by John Wilson from 1857 to 1869 (fig. 33). Although it is not clear when this John Chandler first arrived in Texas, it is believed that he is the slave listed as John in Chandler’s deed of trust executed in 1852. In addition to John Chandler, Marion Jefferson Durham, Thomas Chandler’s nephew, who had attended Chandler’s estate sale in 1854, was also working at the Guadalupe Pottery and in 1869 bought out John Wilson.[49] John Wilson was from the lower part of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, but was educated at Washington and Lee in Virginia, as was his father.[50] He was living near the Chandler family in the mid-1850s. There may be a connection between this John Wilson family and the Samuel Wilson who worked for John P. Schermerhorn in Richmond during the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

On September 27, 1854, the personal belongings of Thomas Chandler were sold at auction.[51] The estate sale featured a number of lots of books; among those books listed and sold were a volume of Shakespeare, The History of the World, The History of the United States, and Camp Stories of the Revolution; another lot was simply “books.” Clearly, Chandler was a well-read and educated man. Additional items included in the sale ranged from several lots of tobacco, an accordion (perhaps the instrument that Chandler played), two beds and other bedroom furniture, one bureau, one cupboard, one saddle, a half-bushel measure, two wagons, a fine carriage, and three mules. Pottery and related items included a jackscrew, a turning lathe (potter’s wheel), and a butter pot made by Isaac Durham, Chandler’s father-in-law, and a few pieces of green ware. One hundred gallons of ware (likely decorated) sold for $.32 a gallon, 100 gallons of (likely plain) ware sold for $.08 a gallon, 3,119 gallons of “less good” ware sold for $.0775 a gallon, and 2,000 gallons of “damaged” ware was sold for $.01 a gallon. Chandler’s widow bought all of the furniture and the turning lathe; Stewart Durham, his brother-in-law, bought most of the pottery and the jackscrew.[52] Attendees were given six months to pay for their purchases. Based on the amount of pottery sold at the estate sale (5,300 gallons, more or less), plus the hundreds of gallons of stoneware sold from January 1853, when Chandler first arrived in Mecklenburg County, until his death in July 1854, it is possible that Chandler had a pottery operation in Mecklenburg County.[53] Good stoneware clays abound in the area, along with flint, iron ore, and feldspar.

The Edgefield Wares and Baltimore Influences

In Baltimore, Thomas Chandler saw a wide range of wares—personal flasks, water coolers, large storage jars, jugs, stew pots, snuff jars, pitchers, pans, and bowls, many decorated with cobalt sprigs, open bell flowers, or daisies intertwined with wreaths and an occasional incised bird perched on a branch. Many of these forms he brought to Edgefield (figs. 34, 35), where he produced his most significant stoneware circa 1837–1853: thousands of well-executed stoneware pots including water coolers, storage jars, syrup and whiskey jugs, flasks, pans, bowls, butter pots, stew pots, snuff jars, buttermilk pitchers, churns, crocks, and face vessels. Chandler also brought a superior knowledge of stoneware manufacturing that I believe he learned from Henry Remmey. Just as Remmey’s arrival in Baltimore had an immediate effect on stoneware manufacturing there, Chandler’s arrival in Edgefield, and in particular the back country of South Carolina, effected an immediate improvement to product utility and decorative design for stoneware manufactured in Edgefield.

Chandler was able to produce, on a consistent basis, a high-quality alkaline glaze like that of the ancient Chinese celadon. He used it on stoneware in South Carolina to great effect, and far more examples of it have been found on Chandler-produced ware than on wares produced by any other potter in the area. Chandler was proficient at finding the right kinds of stoneware clays and knowing precisely how to mix them. His firing technique was equally proficient, reaching the highest kiln temperature for best stoneware results—often approaching such a high level of vitrification that the pots would warp and collapse under their own weight (fig. 36).

The majority of Chandler’s stoneware was decorated with iron and/or kaolin slip, trailed by slip-cup or brushed classic designs, including swag and tassels, loops and swags, cartouches, daisy and bell flowers, tulips, and three-leaf clovers, along with some figural as well as abstract creations. His most elaborate decoration was in two colors, with a brushed iron slip outlined in white kaolin. Another important link to Baltimore is Chandler’s classic swag and three-leaf or tassel design, which he used on his earliest decorated Edgefield stoneware pots (circa 1837–1839) and then on many of his major four-handled, two-color decorated storage jars made at Phoenix Factory in 1840 (fig. 37). This intricate and distinctive decoration was designed and used by John Remmey and family in New York City in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, and has been described as their signature decoration (fig. 38).[54]

Chandler also adopted the flower head on a bent stem, a motif Remmey used with the flowers often placed horizontally in a series (figs. 39, 40). Chandler used the daisy flower extensively in Edgefield, mainly vertically on a bent or broken stem in iron slip but many times between a series of loops and swags (see fig. 51). The flower heads, which are nearly identical to those by Remmey, are seen on Chandler’s pots from his time at the Shaw’s Creek shops (including the Collin Rhodes pottery) to his time at the Martintown Road shops in Edgefield. By most accounts Henry Remmey was the most accomplished stoneware potter in Baltimore in the 1820s, and from 1821 until 1829 he worked for Henry Myers.[55] Chandler seems to have been greatly influenced by Remmey during this time period. Another influence was William Morgan, who in Baltimore in the 1820s signed his pots “Morgan Maker,” phrasing Chandler would use extensively in Edgefield when he signed his own pots.[56] The nearly identical multilobed stamped flower-head designs found on Morgan’s work in Baltimore and on Chandler’s work in Edgefield years later show a strong connection between these two potters.

While in Edgefield, Chandler adapted a decorative technique for marking capacity on his pots. Rather than use a stamped numeral surrounded by a coggle-wheel–executed cartouche (fig. 41), a tool that he and the other potters of Baltimore had used, Chandler executed the number in freehand slip and surrounded it with a scalloped cartouche done in a white kaolin or dark iron color (fig. 42), which could be applied with either a slip cup or a brush. Occasionally Chandler dispensed with the cartouche and drew the capacity mark inside a flower head at the end of a frilly stem, all executed in iron or kaolin slip (fig. 43). This small but significant touch that he added to his stoneware can be seen on many of the decorated pots made in Edgefield during the 1840s and early 1850s. The practice of incorporating the capacity stamp into the cobalt-blue flower-head decoration was used on some Richmond area pots (see, in this volume, Kurt Russ et al., “The Remarkable 19th-Century Stoneware of Virginia’s Lower James River Valley,” p. 239–241) and may further indicate the presence of Chandler in that location between 1829 and 1832.

Other innovations Chandler brought to Edgefield, perhaps influenced by his urban upbringing, were to advertise stoneware for sale in the local newspaper and to create “presentation” stoneware, used to celebrate an event or individual or to promote the stoneware business (fig. 44). I can find no example of advertising or presentation stoneware made in the Edgefield District before 1836.

Another important presentation piece that Chandler made is a huge, approximately 25-gallon, alkaline-glazed stoneware water cooler produced at Phoenix Factory.[57] The sophisticated presentation piece (fig. 45) depicts perhaps a slave wedding, complete with wine-goblet toasting and a curly-tailed sow. Notably there are iron slip–brushed three-leaf clovers on either side of the bride and groom. The incising on both the Baltimore churn illustrated in figures 5–7 and the Edgefield water cooler appears to be in Chandler’s style (fig. 46). In addition, the clover decorations are reminiscent of those used in Baltimore by the Parr brothers. The reverse of the water cooler has a long-leaf wreath generously brushed in iron slip, a style similar to that of Henry Remmey’s work in Baltimore. On the obverse, Chandler again chose iron-slip–brushed inside incised lines and white kaolin-brushed accents on the woman’s bonnet, her leggings, and her handkerchief. It is a monumental example of stoneware and arguably Chandler’s finest surviving work.

Remmey also used a distinctive double-rolled rim on some of his pots, a technique Chandler used circa 1845 on a huge four-handle, approximately 20-gallon jar he made at one of the Martintown Road potteries (fig. 47). Chandler must have been exposed to this rim form while he was working in Baltimore in the 1820s (fig. 48).

Other Baltimore potters had obvious influences on Chandler. His pan form with two slab handles and a squared pouring spout is a nearly exact copy of those made by Morgan and Amoss in Baltimore (see figs. 34, 35). The cobalt decoration Morgan and Amoss applied to their pans (a series of horizontal sprays or sprigs punctuated by a daisy-rosette pattern) was used by Chandler on a different form, usually four-handle storage jars and large water coolers. However, Chandler chose to decorate his pans primarily with either iron slip–brushed swags or loops, or kaolin slip trailed in the same manner, contrasting boldly against a blue-green celadon glaze. Morgan and Amoss sometimes used a zigzag trailed cobalt line on their ware; this is also seen on Chandler-made Phoenix Factory ware (see figs. 24, 34) and Trapp and Chandler examples, but using kaolin slip or iron slip instead of cobalt.

Anywhere Chandler worked in Edgefield, he produced stoneware that rivaled any produced in America during the nineteenth century (fig. 49). His final great experiment, Flint Ware, though not a commercial success proved he was working toward a high-fired stoneware product that could withstand high- and low-temperature extremes consistent with stovetop use. The ware produced at the Trapp and Chandler site was occasionally signed and, less frequently, marked “Chandler Maker” and sometimes “War[r]anted,” but it could also be identified by its bold iron-slip loop-and-swag decoration and occasional flower (fig. 50).

In 1850 Chandler established his own factory about a mile south, closer to Edgefield.[58] There he typically used kaolin slip-trailed decoration instead of iron slip but in a similar format, and he signed much of his work “Chandler Maker,” frequently adding the guarantee “War[r]anted.” He made large, classic water coolers, perfect in form and glaze, and exquisite four-handled storage jars of ten–fifteen gallons decorated in dark iron slip or white kaolin slip loops, swags, and tassels, continuing a decorative technique used at Phoenix Factory but also developing his own decorative signature style—two to three lines of loops below a series of draped lines (fig. 51).

Face Vessels

One of the most distinctive forms Thomas Chandler introduced to the South was the face vessel (figs. 52, 53). I have identified at least nine that I believe have a strong connection to Chandler. The only known signed Chandler face jug, made in Edgefield, suggests that Chandler was the first potter in the South and one of the first in America to make a stoneware face vessel. At least four other Chandler-related stoneware examples from Edgefield survive, two from Phoenix Factory, one a fragment found at the site by Stephen Ferrell, and a nearly complete example found in the marsh of the Charleston, South Carolina, harbor. Two face vessels attributed to the Trapp and Chandler Pottery also exist (figs. 54-57).

I believe Chandler learned how to make face vessels while he was in Baltimore. At least three earthenware face vessels exist that I attribute to this Chandler school, and I believe they were made in Baltimore during the 1820s (figs. 58, 59). These vessels are in the shape of what I call the Southern harvest-jug form, with a pouring or drinking spout and a nipple spout for sipping or venting, and with a bell handle placed across the top of the vessel. This form matches the known Chandler-signed Edgefield example, and was also used on several other Edgefield face jugs in this group, which strengthens the connection. The redware examples share the following characteristics with the signed stoneware Chandler face vessel: kaolin inset eyes with colored pupils, kaolin inset shaped teeth, large and distinctive lips and noses, and sunken eyes, to varying degrees, with Toby sculpted cheeks. The three earthenware examples and the stoneware example are near-exact copies, sharing a highly developed expressive face and the distinctive harvest-jug form.

A ninth face vessel in the harvest-jug form is associated with this group, a jug that is signed with a “J. H. Stone” stamp (fig. 60). However, it has very different facial features. J. H. Stone was a potter in Buncombe County, North Carolina, from about 1867 until the 1890s. His father, Edward Stone, worked in Edgefield for a time at one of the Martintown Road potteries in the 1840s, possibly associated with Thomas Chandler.[59] Although the J. H. Stone harvest face jug likely was made in the mid- to late 1860s, the similarity of the facial features to those found on several Mid-Atlantic face vessels leads me to conclude that Chandler passed on his knowledge of design and artistry to Edward Stone before the mid-1840s, when Stone left Edgefield for Buncome County, North Carolina. Edward later passed on this knowledge to his son J. H. Stone.

The signed “Chandler Maker” face harvest vessel (see figs. 52, 53) descended to James Hunter from his great-great-grandfather Isaac Faires.[60] According to Hunter, Isaac acquired the vessel from a neighbor who had gotten into trouble with the law. The jug was payment for resolving the issue. Researching the 1860 and 1870 censuses for North Carolina and South Carolina, I found that during the period 1855–1870 Isaac Faires was living very near Chandler’s widow, Margaret, and her children in Fort Mill Township, South Carolina.

Concluding Thoughts

After thirty years of studying traditional Southern stoneware manufactured during the nineteenth century, I have come to the following conclusions: Chandler’s stoneware is unmistakable, tracing it from his circa 1837 days working with John Isaac Durham at the pre–Trapp and Chandler Martintown Road site (38GN169), to his work and development of slip decoration at Shaw’s Creek in the late 1830s, his work at a new site on Marintown Road near the Trapp Chandler site from 1844–1848, his work while in a partnership with John Trapp in the late 1840s, and finally his operation a mile south of the Trapp and Chandler Pottery (38GN343) in 1850–1852. His glazes range from a red iron slip, a honey-colored glossy, an agglutinated or slick gray-blue, a thin translucent, and true celadon, and his decoration is bold and well executed. When comparing his ware today with surviving stoneware made by other potters from the period, Chandler’s stoneware is better made, fired to a higher temperature, and coated with a superior glaze. His firing temperature matched the vitrification point of his clay and glaze to perfection.

Chandler’s attainment of perfection in stoneware manufacture is evident in the large volume of his work that survives. The greatest testament to a nineteenth-century potter is the utility of his ware and how it provided for an easier way of life. Thomas Chandler produced wares of lasting utility and great aesthetic beauty that represent the highest degree of stoneware art of his time—and perhaps ours.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project could not have come to fruition were it not for the contributions of living and deceased Edgefield stoneware collectors, ceramics researchers, ceramics historians, and archaeologists. Howard Smith, Fred Holcombe, Joe Holcombe, Georgiana Greer, and Gerald K. Landreth all made significant discoveries regarding Chandler’s life. Cinda K. Baldwin, whose book Great and Noble Jar started many of us down the research road of Southern stoneware. Jane Przybysz, executive director of McKissick Museum in Columbia, South Carolina, along with Jill Koverman, chief curator of collections, gave invaluable advice and encouragement. Steve and Terry Ferrell allowed access to their tremendous Ferrell Pottery Museum, including the archaeology of several of the sites where Chandler potted. Prominent collectors John Hoar and Bill Cox listened to me almost daily as I sorted through data to reach my conclusions. My wife, Debbie, critiqued my many revisions and continually reminded me that I was doing good work. Carl Steen helped with understanding the archaeology and shared anything he had pertaining to Chandler. The Reverend Jerry Robinson shared his collection with me in 1980, exposing me to my first example of alkaline-glazed stoneware. William Robert Jordan’s work as an archaeologist in Washington County, Georgia, was very helpful in tracking Chandler. Both John E. Kille’s work on the Baltimore stoneware industry and Kurt C. Russ and W. Sterling Schermerhorn’s work on Richmond-area potteries were very helpful. Carole Wahler gave me productive leads to follow and shared important photos of face vessels. David Good shared his vast knowledge of Americana and allowed me to study his collection of Edgefield face vessels, which includes several important Chandler examples. My friend Jim Hunter shared his family connection to Chandler and was the inspiration for me to tackle this project. The folks at the Eastern Shore Public Library in Accomack were very helpful in unraveling the Chandler lineage. William Mathis, a direct descendant of Thomas Chandler, shared photos and genealogical data of great importance. Thanks to Gordon Lohr for sharing his monumental find, the signed Chandler Baltimore churn, and to Al Zimmerman, who gave me the tip that such a pot existed. Conversations with Charles Santore about American Windsor chairs, and with Jenny Barker about the Methodist movement in Accomack County, led me to new discoveries about Chandler. Tony Zipp of Crocker Farm Auctions, Gary Albert of MESDA, Bruce and Vicki Waasdorp of American Pottery Auctions, and Whitney Bounty at Freeman’s Auctioneers and Appraisers shared important photography. For her great work behind the camera, I thank my friend Jan Todd, who followed me to a half-dozen collections with camera, backdrop, and accessories in tow. Huge thanks to Wade Fairey, Charles Comolli, Steve and Terry Ferrell, Donnie Garrett, David Good, Vivian and Gerald Gowitt, Doug and Brenda Howard, John Lafoy, L. C. Lynch, Sam Phillips, Jason Shull, Mary Smith, Donny Taylor, David Ward, Randy Windham, Jim Witkowski, and Jeremy Wooten for allowing me to photograph their Chandler stoneware collections, and to Bill Cox, John Hoar, Carl Steen, Carole Wahler, and Colonial Williamsburg for sharing photos with me. I am particularly grateful to the Chipstone Foundation for funding Ceramics in America, and to Rob Hunter for giving me the opportunity to publish something we both agreed was important. Whether I follow a path or blaze a trail, my friends help me find my way.

Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1798–1914, s.v. “US Army Register of Enlistments”; National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, Washington, D.C. In the 1840 U.S. Census for the Edgefield District, Chandler is listed as a pensioner for service in the military.

Baltimore County Indentures, 1794–1799, book 1, folio 189, Eastern Shore Public Library, Accomac, Virginia.

Thomas Chandler Sr., “Evidence Explained: Citing the Wise File on Chandler Genealogy,” Eastern Shore Public Library, Accomac, Va.

Gail Walczyk, Accomack Indentures, 1798–1835 (Coram, N.Y.: Peter’s Row, 2002), pp. 16–17.

In 1940 the Virginia General Assembly officially added a “k” to the end of the county’s name to arrive at its current spelling of Accomack.

Nancy Goyne Evans (American Windsor Chairs [New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1996], p. 687) has Thomas Chandler in Baltimore in 1817. See also 1820 U.S. Census Records, Baltimore Ward 2, Baltimore, Md., p. 100; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter cited as NARA), roll M33, image 62; available at www.archives.gov.

Elizabeth Wise and Thomas Chandler married in Baltimore on July 18, 1802. Thomas Chandler was a chairmaker and grocer. Baltimore City Directories lists Elizabeth Chandler as a shopkeeper in 1829 and grocer in the early 1830s. The couple had eight children. The painting was handed down by descent from Elizabeth Wise Chandler to her daughter, Ann Elizabeth Chandler (Mrs. Andrew Jackson Bandel), to her eldest daughter Mary Elizabeth Bandel (Mrs. George Hakesley), to her daughter Grace Hakesley Bryn, to Elizabeth Bandel, to the present owner. See also Carolyn J. Weekley and Stiles Tuttle Colwill, eds., Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Maryland Historical Society, 1987), pp. 164–65, no. 82. The people of Accomack were very sympathetic to the plight of African-American slaves due to the Methodist Revivalism that occurred in that county beginning in 1800. See Kirk Mariner, Revival’s Children: A Religious History of Virginia’s Eastern Shore (Salisbury, Md.: Peninsula Press, 1979), pp. 34–52.

C. Keenan, The Baltimore Directory for 1822 and ’23 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1822–23).

Luke Zipp, “Henry Remmey & Son, Late of New York: A Rediscovery of a Master Potter’s Lost Years,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2004), pp. 143–61.

Luke Zipp, “Baltimore Stoneware,” Antiques & Fine Art (Summer 2006): 154–58.

Gordon Lohr, collector, telephone interview by Philip Wingard, Fall 2005.

On June 26, 1829, Thomas Chandler Jr. paid $11.29 for a Baltimore City grocery license. His mother, Elizabeth, is listed as head of household in Baltimore in the 1830 U.S. Census.

George F. Chandler completed his apprenticeship when he reached the age of twenty-one. He is listed in the 1837 Baltimore City Directory as a potter on 21 Comet Street.

Zipp, “Henry Remmey & Son, Late of New York,” p. 146.

A review of the 1831 Baltimore City Directory published by Matchett shows a reduction in the number of potteries in operation.

Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1798–1914, “US Army Register of Enlistments.”

U.S. History: Pre-Columbian to the New Millennium, “24c. The South Carolina Nullification Controversy,” www.ushistory.org/us/24c.asp (accessed on June 15, 2012).

Ibid.

Returns from Regular Army Infantry Regiments, June 1821–December 1916, microfilm serial M665, roll 42, NARA.

Ibid.

William Robert Jordan, “Archaeological Investigations of Alkaline-Glazed Stoneware Production Sites in Northern Washington County, Georgia” (master’s thesis, Georgia State University, 1996).

My Wingard ancestors in the 1820s used the Meriwether Trail to travel west from Lexington, South Carolina—via Augusta, Georgia—to settle in southeastern Alabama, near Fort Mitchell.

Jordan, “Archaeological Investigations,” p. 38, fig. 4. I researched several deployments to Fort Mitchell from Augusta and found that the march took, on average, nineteen days.

Ibid., pp. 174–78, fig. 54.

Returns from Regular Army Infantry Regiments, June 1821–December 1916, microfilm serial M665, roll 42, NARA.

Court of Pleas and Quarto Sessions, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, December 21, 1857, transcribed from microfilm, Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Charlotte, N.C.

A history of this artillery regiment, written by Lieut. W. A. Simpson, Adjutant 2nd U.S. Artillery, gives a concise account of the actions of the 2nd Regiment and all companies associated with it before and during the Second Seminole Indian campaign of 1835. This account is available online at www.history.army.mil/books/R&H/R&H-2Art.htm (accessed August 30, 2013).

Returns from Regular Army Infantry Regiments, June 1821–December 1916, microfilm serial M665, roll 42, NARA.

Court of Pleas and Quarto Sessions, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, December 21, 1857.

U.S. Army Register of Enlistments, 1798–1914, record for Thomas Chandler, NARA, roll M233; see also the marriage notice found in McClendon’s Edgefield Marriage Records, p. 32.

Cinda K. Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), pp. 32–57.

This conclusion is based on my comparison of the handwriting on the two Pottersville presentation examples made in 1836 with the handwriting on a Chandler-signed presentation jar to B. Harland in 1844.

Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, p. 148.

See George J. Castille et al., Archaeological Survey of Alkaline-Glazed Pottery Kiln Sites in Old Edgefield District, South Carolina (Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1988), pp. 15–17, 38; Gerald K. Landreth, “Archaeological Investigations at the Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Kirksey, South Carolina” (master’s thesis, University of Idaho, 1986). See also Joe L. Holcombe and Fred E. Holcombe, “South Carolina Potters and Their Wares: The Landrums of Pottersville,” South Carolina Antiquities 18, nos. 1–2 (1986): 47–62. I also studied the artifacts recovered by Steve and Terry Ferrell at the Trapp/Chandler and the Shaw’s Creek sites, which included sherds from Phoenix Factory.