Money box, Surrey, England, fourteenth century. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of London, acc. no. A3855; photo, © Museum of London.) This example of Kingston-type ware was found in Paternoster Row, City of London.

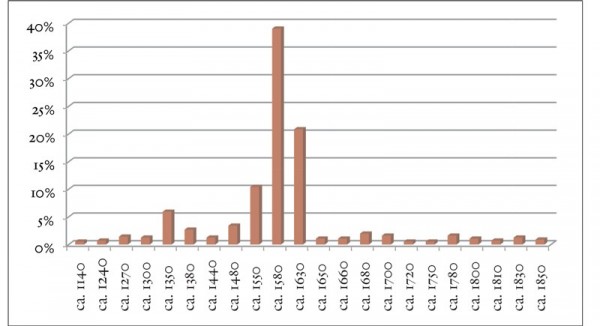

The chronological distribution of ceramic money boxes from London excavations, in minimum number of vessels from dated contexts.

Money-box fragments, from Surrey-Hampshire border, England, 1580–1630. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Photo, A. Chopping, © Museum of London Archaeology.) These fragments were found on the site of The Rose theatre, Southwark, London (site code SBH88).

Money-box finials, from Surrey-Hampshire border, England, 1580–1630. (Photo, A. Chopping, © Museum of London Archaeology.) One of the finials, all of which were taken from the site of The Rose theatre, Southwark, London (site code SBH88), shows a pinhole made before firing.

When Noël Hume first emailed me about pinholes in money boxes from London, I had to confess I had never noticed any, but the next day I went to see what I could find in the Museum of London’s Ceramic and Glass Collection. A quick examination brought to light six money boxes in Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware with the tiny telltale hole, still perfectly visible, just as Noël had said.

The finds in the Museum’s reserve collection—the most complete and displayable examples from sites across London—are just the tip of the iceberg. The collection includes 83 ceramic money boxes in a variety of wares, spanning the medieval period through to the nineteenth century. A much larger body of evidence is to be found in the archive amassed by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) and its predecessors over more than forty years. The computerized database records sherds from at least 556 money boxes excavated on 142 sites in London, mostly from within the square mile of the City of London and from the borough of Southwark, across the Thames. A number of questions quickly came to the fore: When did ceramic money boxes first appear, and how did the form evolve over time? What were the main centers of production? Where were they being used? And, of course, how common are examples with pinholes?

The earliest money boxes recorded in London excavations are in green-glazed white earthenware made at Kingston upon Thames, in the medieval Surrey whiteware tradition.[1] These small, enclosed containers have a low-domed or pointed top, like a bishop’s miter, and usually have a narrow, vertical coin slit, although a few with horizontal slits are known (fig. 1).[2] A few examples have a more elaborately shaped knob or finial, resembling a money bag tied at the neck.[3] Several kilns have been excavated in Kingston, but so far have yielded only one money box.[4] Clearly that example was thrown away because the potter had not made adequate allowance for shrinkage and the coin slit had become too narrow during firing (see p. 142, fig. 6, in this volume for a similar example from the Farnborough kilns in Hampshire). Dating evidence from these kilns coincides closely with the earliest finds from London, recovered from Thames waterfront sites and dated by dendrochronology to the beginning of the fourteenth century.[5]

Money boxes were also made in at least two other ceramic industries within the medieval Surrey whiteware tradition. One of these was centered on Cheam in Surrey, its products used in London circa 1350–1500, and although no money boxes were found at any of the excavated kilns, a few have been recovered from consumer sites in London, including examples cited by Ivor Noël Hume (see pp. 139–41, figs. 3–4 and accompanying text in this volume).[6] One of these was excavated in 1949–1950 at St. Swithin’s House, 30–37 Walbrook.[7] Work by MOLA on the same site in 1996 brought to light a second complete Cheam money box in a late-fifteenth-century context.[8] Another nearly complete miter-shaped money box was found during excavations at Gateway House, Watling Street, directed by Noël while he was the Guildhall Museum’s City Archaeologist.[9]

Surrey-Hampshire Coarse Border Ware was perhaps the most significant of the whiteware industries in the developing story of the money box. Between circa 1350 and 1500 this heavy-duty, practical pottery dominated London’s ceramic supply.[10] Money boxes formed a minor part of the potters’ repertoire, and all were made in the familiar domed or miter shape.[11] At the end of the fifteenth century, however, the potteries of this region began to focus on producing a narrow range of high-quality, thin-walled drinking vessels in a much finer, green-glazed white earthenware, at the expense of coarseware production.[12] These finewares became the mainstay of the industry, which thrived on its market connections with London, supplying a number of major institutions, such as the Inns of Court.[13] During the second half of the sixteenth century, the industry was transformed under the influence of Harmon Raignold (Herman Reynolds), an immigrant German potter, developing new forms made in a more durable whiteware fabric.[14] By the early 1600s the Surrey-Hampshire potteries had become one of the most important sources of London’s everyday pottery.

Among forms inherited from the medieval tradition, the money box evolved into its characteristic sixteenth–seventeenth-century shape, with a knob or finial formed above a narrow constriction at the top.[15] It invariably has a flat or slightly dished base, often with concentric or fan-shaped marks left by the wire used to remove it from the wheel. Money boxes also frequently have small kiln scars in two or three places around the shoulder or maximum girth, resulting from contact with other vessels in the firing stack (see p. 149, fig. 16, in this volume).

Money boxes made in Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware, including the early-sixteenth-century finewares, account for 52 percent of the Museum of London’s reserve collection, and 84 percent of all examples from MOLA excavations; 13 percent of the remaining boxes were excavated finds made in medieval Surrey whitewares. Most Border Ware money boxes have a copper-stained green glaze covering the top half of the vessel, although a few have a clear glaze that appears yellow over the buff fabric.[16] Although the green-glazed whiteware was the most widely used, a small number of money boxes are also known in contemporaneous redware fabrics.[17]

The main concentration of finds from London dates between 1550 and 1630 (fig. 2), peaking at 1580 and falling off sharply after the 1640s, which Noël suggests could be the result of a Puritan clamp-down on apprentices’ Christmas boxes during the Commonwealth. By far the greatest number of money boxes excavated in London is focused on the sites of two Tudor playhouses: The Theatre in Shoreditch and the Rose in Southwark, with a further concentration around the animal-baiting arenas of Southwark’s Bankside.[18] Recent MOLA excavations in Shoreditch uncovered evidence for the playhouse long associated with early productions of Shakespeare’s plays. Opened in 1576, The Theatre was dismantled in 1598 and its timbers reused in the construction of the Globe, in Southwark.[19] Sherds from at least twenty-four money boxes in Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware were recovered from the site, but these pale into insignificance compared with the massive collection from The Rose: 378 sherds from at least 162 money boxes (fig. 3).[20] All are made in green-glazed whiteware and share a common form, although there are minor variations in the shape of the finial.[21] Remarkably, money boxes formed the third largest group of ceramic vessels found on the site, after those used for food and drink.[22] They all came from contexts within the playhouse, dating to its lifetime and shortly after, from the 1580s to the 1630s. Although no examples were recovered from the site of the Globe, the excavation area was much smaller and access limited.

At least one money box from The Theatre and a number of money boxes from The Rose have a small pinhole pierced through the body (fig. 4). It is impossible to tell how widespread the practice was because so many London finds are identified solely by their bases and finials. Only one of the medieval money boxes that were examined, a miter-shaped form in Kingston-type ware (Museum of London, acc. no. 5767), showed any evidence of a pinhole, although this does appear on several of the more complete sixteenth- and seventeenth-century forms. Closer examination of the Border Ware money boxes in the Museum of London reserve collection revealed an additional eleven examples with a pinhole, making seventeen in all (or 40 percent of all examples in this fabric). In most cases the hole is very small and not easily spotted, stabbed just below the finial on the side opposite the coin slit. A few examples have a slightly larger, neatly made hole, or have been stabbed closer to the coin slit. Some of the broken money boxes have a small spot of glaze on the inside, spreading from a tiny pinprick that is otherwise invisible from outside because it was filled in with glaze. Without breaking them it is hard to know how many more of the museum’s complete money boxes without an obvious pinhole had been stabbed during manufacture.

Why were so many money boxes found at The Theatre and The Rose? One suggestion is that they were used at various access points within the playhouses, controlled by “gatherers” or “collectors” to receive monies from the patrons; the proceeds were then kept under lock and key in the “Commone boxe.”[23] Ceramic money boxes were cheap to make and easily replaced following their inevitable breakage to remove the contents. However, as Noël has pointed out, this kind of container hardly seems suitable for collecting coins from large, bustling crowds of people and it positively invites deception. Another suggestion is that they were used by local traders who provided refreshments for the playgoers, although the same objections would apply to their suitability as money containers in a crowded venue. Could they even have been a speculative bulk purchase, perhaps of surplus stock brought in by one of the livery companies, that proved impractical, leading to their ultimate replacement with more suitable containers? The proprietor of The Rose, Philip Henslowe, was also a member of the Dyers Company and this could provide a possible link.

We know that some of the potteries on the Surrey-Hampshire border had established business relationships with various London institutions, such as the Inns of Court, and supplied them with regular consignments of specific forms.[24] Perhaps some of the playhouses, or traders who held concessions within them, also had contracts with the potteries to supply them in bulk with pots designed to order. Similar arrangements were in place with some of the City’s livery companies, who ordered easily replaceable, good-quality ceramic drinking vessels for use at their feasts and messes, as well as other forms designed to meet a variety of needs.[25] This brings us back to the apprentices and their earthenware boxes, which would need to be purchased each Christmas, presumably in bulk and from the same sources that supplied fine tablewares. This link is reinforced by a reference in A Calendar of the Inner Temple Records to an account for Christmas 1620, which lists “. . . in money boxes, 11s. 6d.”[26] Were these given annually by the “Benchers” to the young gentlemen of the inn, their pupils?

The concentration of finds in Southwark, especially around the entertainment venues along Bankside, and on sites in the City of London, where Livery Halls were to be found at every turn, is telling. It may well be presenting us with the key to the development, use, and popularity of the simple money box, beginning in the late medieval period and reaching a peak in Tudor and Stuart London. Perhaps in these finds we can see yet another example of the entrepreneurial connections of the astonishingly enterprising potters of the Surrey-Hampshire border and their medieval antecedents. And what form could be more fitting than the money box to symbolize these flourishing connections?

There are eleven substantially complete Kingston-type ware examples in the Museum of London Ceramic and Glass Collection, and twenty-four in the MOLA database. These figures are based on data available up to July 2013; the MOLA ceramic database may be consulted by application to Museum of London Archaeology, Mortimer Wheeler House, 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London n1 7ED, UK.

Jacqueline Pearce and Alan Vince, A Dated Type-Series of London Medieval Pottery, Part 4: Surrey Whitewares. Special Paper (London and Middlesex Archaeological Society), 10 (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1988), fig. 99, nos. 373–79.

Ibid., fig. 99, nos 381–83; three near-complete examples were found at Bull Wharf in 1990 (site code BUF90, context [3091], dated to ca. 1350–1500).

Excavated in 1995 at 70–76 Eden Street (site code EDN95). Pat Miller and Roy Stephenson, A 14th-Century Pottery Site in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey: Excavations at 70–76 Eden Street. MoLAS Archaeology Studies Series, 1 ([London]: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 1999), p. 27, fig. 29.

Pearce and Vince, A Dated Type-Series, fig. 41. Archaeomagnetic dates for Kiln 1 are 1300–1325 at 68% level of confidence, or 1290–1330 at 95% level of confidence, and for Kiln 2, 1310–1330 (68%) and 1300–1340 (95%). Ibid., p. 11.

Ibid., pp. 84–88. See Clive Orton, “The Excavation of a Late Medieval/Transitional Pottery Kiln at Cheam, Surrey,” Surrey Archaeological Collections 73 (1982): 49–92; see also Clive Orton, personal communication, July 15, 2013. Only thirteen money boxes in Cheam whiteware are listed in the MOLA database; one is in the Museum of London Ceramic and Glass Collection.

The site has subsequently been given the code GM158.

Then Museum of London Archaeology Service (MoLAS), site CAO96: Nicholas Elsden, Excavations at 25 Cannon Street, City of London: From the Middle Bronze Age to the Great Fire, MoLAS Archaeology Studies Series 5 ([London]: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2002), fig. 39.

Site GM160.

Pearce and Vince, A Dated Type-Series, pp. 84–85.

Nineteen examples are recorded in the MOLA database; see ibid., fig. 119, no. 523.

Jacqueline Pearce, Pots and Potters in Tudor Hampshire: Excavations at Farnborough Hill Convent 1968–72 ([Guildford, Eng.]: MoLAS/Guildford Borough Council, 2007), pp. 64–72.

Jacqui Pearce and Peter Tipton, “How Technology Transfer from the Continent Transformed English Ceramic Manufacture in the 16th Century,” Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle 22 (2011): 179–214.

Pearce, Pots and Potters in Tudor Hampshire, pp. 13–16.

Jacqueline Pearce, Post-Medieval Pottery in London, 1500–1700. Part 1: Border Wares (London: HMSO, 1992), fig. 43, nos. 368–89; Pearce, Pots and Potters in Tudor Hampshire, p. 139, fig. 83, nos. 639–44, and fig. 84.

The MOLA database includes at least 221 money boxes in green-glazed Border Ware but only 33 examples with clear glaze (including examples in which the color appears olive through reduction in the kiln). An additional eight money boxes are made in the redware fabric.

There are four examples in the MOLA database in London-area post-medieval redware and four in the Museum of London Ceramics and Glass Collection, as well as nine money boxes in Essex-type post-medieval fine redware.

See Anthony Mackinder and Simon Blatherwick, Bankside: Excavations at Benbow House, Southwark, London SE1, MoLAS Archaeology Studies Series, 3 ([London]: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2000), p. 16, fig. 10.

Site NIN08; J. Pearce, “A Face from the Past: A Unique Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware Find from Shoreditch, London,” in Amanda Dunsmore, ed., This Blessed Plot, This Earth: English Pottery Studies in Honour of Jonathan Horne (London: Paul Holberton, 2011), pp. 211–15.

Julian Bowsher and Pat Miller, The Rose and The Globe—Playhouses of Shakespeare’s Bankside, Southwark: Excavations 1988–90, MOLA Monograph, 48 ([London]: Museum of London Archaeology, 2009), pp. 72–73, fig. 63.

Ibid., p. 77, fig. 66.

Ibid., p. 133.

Ibid.

Leslie G. Matthews and H. J. M. Green, “Post-Medieval Pottery of the Inns of Court,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 3 (1969): 1–17.

Ongoing research is being conducted by Mandy Hunt based on research for a B.A. dissertation at the University of Leicester.

A Calendar of the Inner Temple Records, edited by F. A. Inderwick, Q.C., 9 vols. (London: Chiswick Press), vol. 2 (1603–1660), p. 122. I am grateful to Mandy Hunt for this reference.