Detail of A Map of the most Inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole Province of Maryland with Part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. Black-and-white line engraving with period color. H. 31 3/8", W. 49 1/8". Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, cartographers. Thomas Jefferys, map engraver. London, 1768. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Fredericksburg and Falmouth are illustrated on either side of the Rappahannock River.

Candle stand attributed to James Allan, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1759. Mahogany. H. 48", W. 10" (top). (Courtesy, George Washington’s Mount Vernon; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The gallery of the stand is triple laminated for resilience and strength. This is an urban British detail rarely encountered on colonial American furniture.

Detail of the carving on the candle stand illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the construction and carving of the base of the candle stand illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

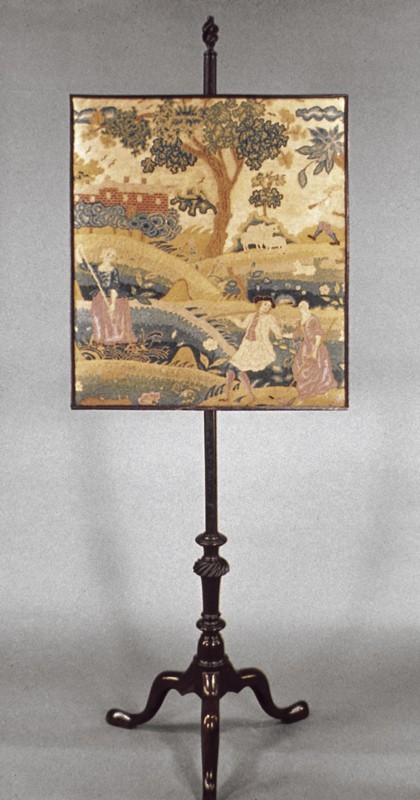

Fire screen, London, England, ca. 1759. Mahogany. H. 57", W. 18 3/4", D. 17 1/8". (Courtesy, George Washington’s Mount Vernon.) The pair of fire screens that George Washington purchased from London cabinetmaker Philip Bell in 1759 cost eight shillings less than the pair of stands Washington bought from James Allan.

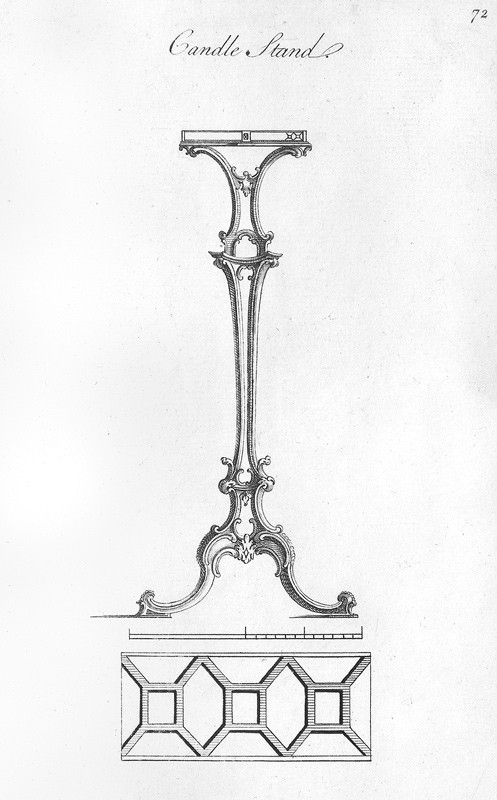

Design for a candle stand illustrated on plate 72 in London Society of Upholsterers, Genteel Household Furniture (London, ca. 1760). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

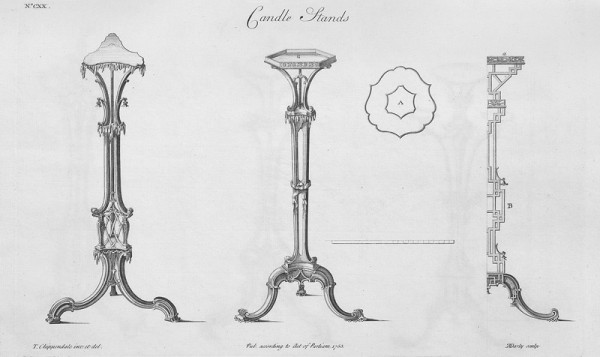

Designs for candle stands illustrated on plate 122 in Thomas Chippendale, Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The date on this engraved plate is 1753.

Side chair possibly by James Allan, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1775. Black walnut with yellow pine. H. 38 7/16", W. 19 7/8", D. 19 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

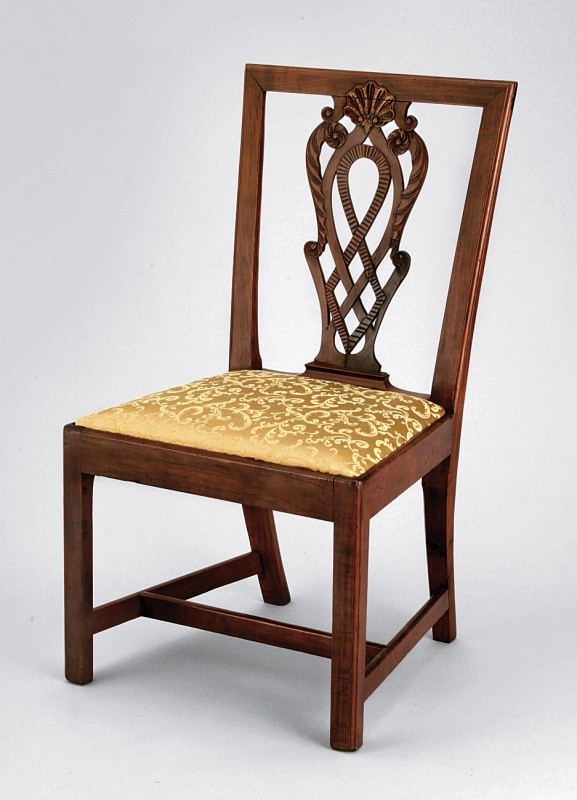

Side chair possibly by James Allan, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1780. Cherry with yellow pine. H. 36 3/8", W. 20 1/2", D. 20 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Peebles in honor of Ronald L. Hurst.) This chair is almost identical to the Magruder family chair not illustrated. The shell at the top of the splat on the Magruder chair is inverted.

Side chair possibly by James Allan, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1775. Black walnut. H. 35 5/8", W. 20", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Side chair possibly by James Allan, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1770–1775. Mahogany. H. 38 1/2", W. 19 5/8", D. 19 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Mrs. A. D. Williams.) The splat is replaced.

Side chair possibly by James Allan, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1775. Mahogany with ash. H. 37 5/8", W. 22", D. 16 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Benjamin Bucktrout, armchair, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1766–1777. Mahogany and black walnut. H. 65 1/2", W. 31 1/4", D. 29 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) For more on this chair, see F. Cary Howlett, “Admitted to the Mysteries: The Benjamin Bucktrout Masonic Master’s Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 195–232.

Armchair attributed to the Anthony Hay Shop, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 52 1/2", W. 29 1/2", D. 26 1/4". (Courtesy, Williamsburg Masonic Lodge.) This armchair was probably made for the master of Williamsburg Masonic Lodge No. 6.

Armchair attributed to Thomas Miller, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1773–1774. Mahogany with walnut and oak. H. 42 1/2", W. 27 1/2", D. 18 7/8". (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This armchair was probably made for the master of Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4. The Grand Lodge of Scotland chartered the Fredericksburg lodge.

Armchair, probably Falmouth, Virginia, 1773–1785. Mahogany and walnut with yellow pine. H. 43", W. 28 3/4", D. 18 7/8". (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This armchair was probably made for the Falmouth Masonic lodge.

Detail of the eye on the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The carving on this armchair is superior to that on the example illustrated in figs. 16 and 19. The eye on the Lodge No. 4 chair is naturalistic with subtle modeling of the eyelids and eyebrow.

Detail of the back of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the armchair illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4 Record Book, March 3, 1753. (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

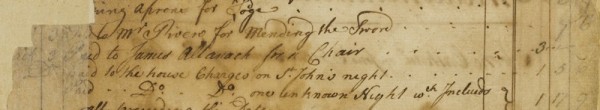

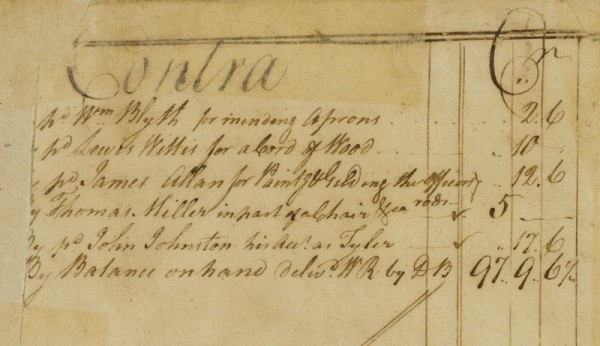

Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4 Record Book, 1773–1774. (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, ca. 1749. Mahogany. H. 38 1/2", W. 28 1/2", D. 18". (Courtesy, Mary Washington House of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the dovetail used to join the left arm and rear stile of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the quarter-round, two-part vertical glue block behind the right front knee of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chamfering on the splat of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the front seat rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The gadrooned molding and knee blocks are attached to the face of the rail.

Design for a frieze illustrated in Abraham Swan, The British Architect (London, 1758), pl. 52. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This plate first appeared in the 1745 edition.

Detail of the carved husks on the left arm support of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the shoe of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The flutes represent triglyphs and the rosettes represent metope flowers.

Side chair attributed to William Fenton, London, ca. 1768. Mahogany with beech. H. 36 1/8", W. 19 7/8", D. 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Stove designed by Abraham Buzaglo, London, 1770. Cast iron. H. 89", W. 35 1/8", D. 21 11/16". (Courtesy, Commonwealth of Virginia; on loan to Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Thomas Chippendale, armchair, after a design by Robert Adam, London, 1765. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. H. 41 3/4", W. 30 3/8", D. 30 3/8". (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk.) Chippendale made this chair for Sir Lawrence Dundance of London and Aske Hall. Like the Lodge No. 4 armchair, this example has both George II and early neoclassical details.

Kenmore, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1772–1775. (Courtesy, George Washington’s Fredericksburg Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chimneypiece in the first-floor chamber in Kenmore. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The architectural carving in Kenmore was probably installed near the end of construction in 1774 or 1775.

Chimneypiece in the Chimneys, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1775–1780. (Courtesy, Eileen’s at the Chimneys; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a five-petal flower on the appliqué of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a five-petal flower and leaf appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 35. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a five-petal flower carved in relief on the front seat rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Large dining room in Kenmore. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chimneypiece has neoclassical features not found on other carving in Kenmore.

Armchair attributed to Thomas Miller, Fredericksburg, Virginia, ca. 1774. Cherry with oak. H. 38 1/2", W. 26 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the carved anthemion on the crest rail of a side chair from a set that included the armchair illustrated in fig. 40. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the carved anthemions and husks on the left truss of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the dovetail used to join the right arm and rear stile of the armchair illustrated in fig. 40.

Detail of the two-part vertical glue block reinforcing the left front leg and rail joints of the armchair illustrated in fig. 40. One laminate of the glue block is a replacement.

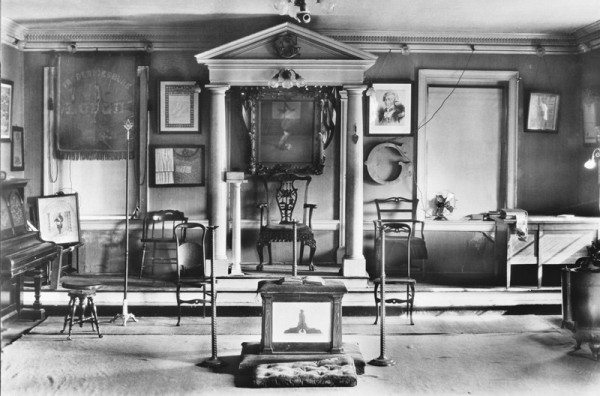

Photograph of the Old Lodge Room, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, Fredericksburg, Virginia, ca. 1930. (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M.)

Side chair attributed to Thomas Miller, Fredericksburg, Virginia, ca. 1774. Mahogany with oak. H. 37 1/2", W. 21 1/2", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Side chair attributed to Thomas Miller, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1769–1774. Black walnut. H. 37 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center, gift of Genevieve Rowe Hunter; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to Thomas Miller, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1769–1774. Mahogany with oak. H. 39 1/2", W. 26 1/2", D. 17 7/8". (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock case attributed to James Allan with movement by Thomas Walker, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1785. Mahogany with yellow pine, tulip poplar, oak, and cherry. H. 106 1/4", W. 22", D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, M. and M. Karolik Collection,© 2006 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.) Carved pagodas like the example on the hood of this clock occur in the same context on British cases as well as those made west of Fredericksburg.

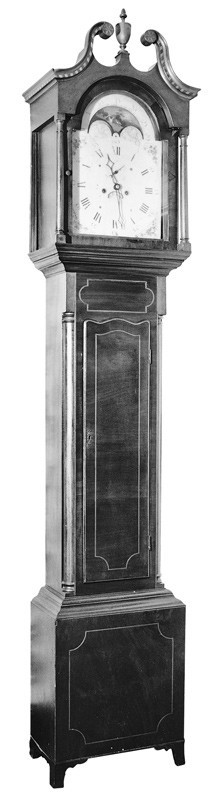

Tall clock case attributed to James Allan with movement by Thomas Walker, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1785. Black walnut with yellow pine. H. 97 1/4", W. 21 1/4", D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Jane C. Lanham and Shirley Lanham McCrary.)

Tall clock case attributed to James Allan with movement by Thomas Walker, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1785. Walnut with yellow pine and oak. H. 96 1/2", W. 20 7/8", D. 10 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Elizabeth M. Nicholson).

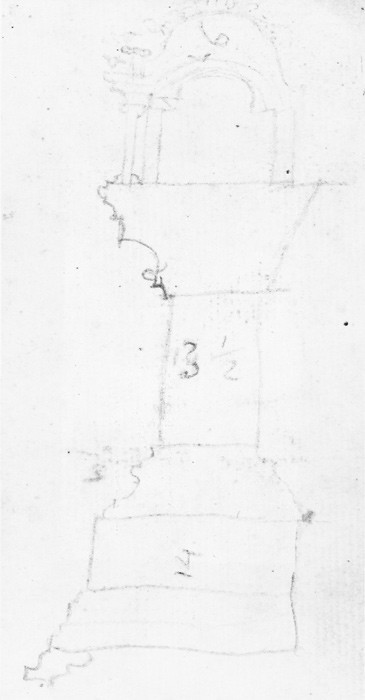

Sketch of a tall case clock in the account book of Robert Cockburn, Falmouth and Orange County, Virginia, 1767–1777. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Tall clock case attributed to Robert Walker, Fredericksburg, Virginia, with movement by Goldsmith Chandlee, Winchester, Virginia, 1809–1811. Cherry, cherry veneer, and lightwood inlay with walnut and tulip poplar. H. 98 1/2", W. 27 7/8", D. 10 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens). This clock descended in the Booth family of Westmoreland County, Virginia.

Side chair, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1805–1815. Mahogany with ash and yellow pine. H. 36 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Side chair, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1800–1815. Mahogany with black walnut and soft maple. H. 34 1/8", W. 19 1/2", D. 17 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

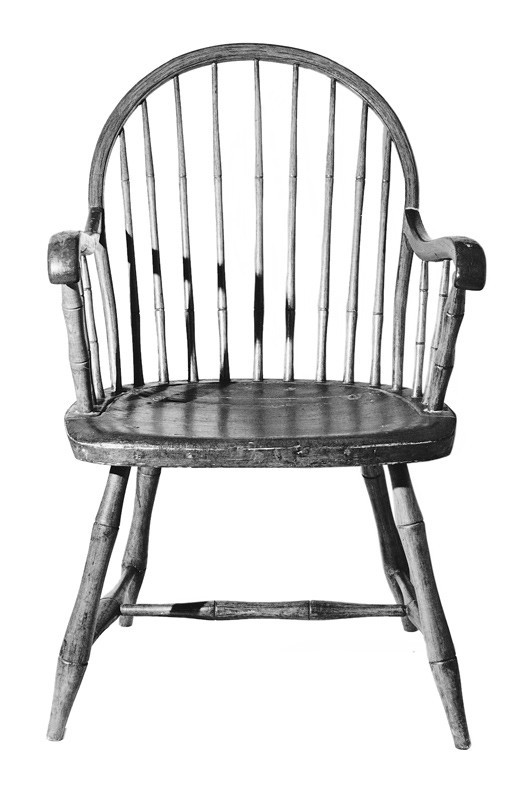

Armchair stamped “J. Beck,” Fredericksburg, Virginia, ca. 1805. Tulip poplar, hickory, and birch. H. 36", W. 20 3/4", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

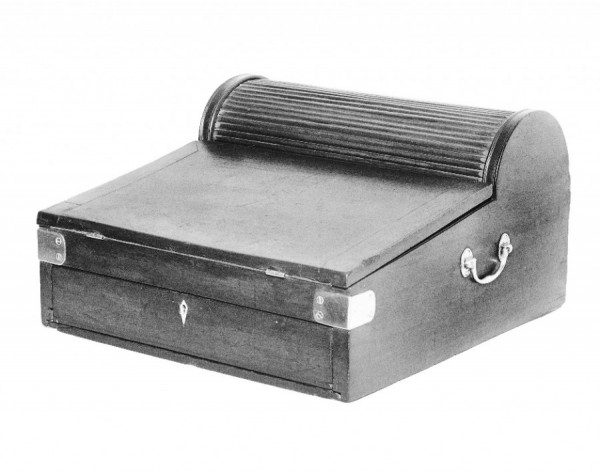

Lap desk attributed to James Beck, Fredericksburg, Virginia, ca. 1806. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 9", W. 15", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

As this issue of American Furniture attests, much progress has been made in identifying the work of joiners, cabinetmakers, and allied tradesmen active in eastern Virginia. Recent research indicates that the towns and ports of the Northern Neck (fig. 1) were more important style centers than scholars formerly recognized. Indeed, many significant pieces of furniture once attributed to Williamsburg can now be assigned to Fredericksburg makers based on documentary sources, family histories, style, and construction. This article will explore the work of newly identified craftsmen and use objects with Fredericksburg histories to illuminate the cultural, social, and economic contexts of furniture production in that town.

Located at the highest navigable point along the banks of the Rappahannock River, Fredericksburg, Virginia, was well situated to serve as a regional market center during the eighteenth century. The earliest settlers to the region came to mine the rich iron ore discovered in Spotsylvania County. Iron, tobacco, and later wheat were the foundation of the town’s prosperity. Merchants, artisans, speculators, and entrepreneurs arrived in Fredericksburg with the establishment of the official tobacco warehouses in 1730. Oceangoing ships sailed up the river to be loaded with tobacco and other products from Spotsylvania and the surrounding counties for shipment to Europe. Merchants saw great potential for the region and set out to develop businesses and trade networks. In 1732 William Byrd explained, “the inhabitants [of Fredericksburg] are very few. Besides Colonel Willis, who is the top man of the place, there are only one merchant, a tailor, a smith, and an ordinary keeper.” Twenty-seven years later, Reverend Andrew Burnaby described Fredericksburg as “by far the most flourishing [town] in these parts.” Between 1732 and 1759 Fredericksburg had grown from a frontier town to a prosperous city with numerous artisans and merchants.[1]

With the official tobacco warehouses and inspection station for Spotsylvania County located in Fredericksburg, the town became a central locale for all the tobacco planters in the region. During the mid-eighteenth century, the inspectors’ salaries, which were based on the volume of tobacco they processed, were among the highest in Virginia, highlighting both the region’s importance within the colonial economy and the resulting affluence of the tobacco plantations and merchants. The wealth of the northern Virginia landowners and their credit arrangements with British mercantile firms allowed them to purchase furniture directly from Britain as well as from local artisans.

One of the earliest recorded cabinetmakers in Fredericksburg was James Allan (1716–1789), who emigrated from Hamilton, Scotland, in 1739. James’s father was a merchant and landowner who also served as Hamilton’s bailie and councillor. His brother John (1712–1750), who had arrived in Fredericksburg about five years earlier, probably began his career in the colonies working as a factor, or agent, for a Glasgow mercantile firm. Young Scotsmen often came to America for practical training in the mercantile business, especially those involved with the tobacco trade. Many returned home after a few years, but others remained, working either for Scottish firms or as independent merchants. A number of Fredericksburg and Falmouth merchants began their careers as resident factors, purchasing tobacco for shipment to Glasgow, where it was exchanged for British and West Indian goods. Much of the tobacco sent to Scotland was intended for the French market.[2]

John Allan arrived in Fredericksburg just as the town was beginning to grow and the Glasgow mercantile firms were becoming involved in the Virginia tobacco trade. He quickly immersed himself in the tobacco business and began participating in local government. In 1743 he and a Stafford County merchant, Nathaniel Campbell, purchased two tobacco warehouses in Fredericksburg. John also owned a tavern, served in local government, and speculated in real estate. In 1745 he purchased ten acres on the edge of Fredericksburg and laid out town lots to form a subdivision known as Allan Town. In his 1750 will, John left his brother James lot 62 in Fredericksburg, his household furniture, watch, wearing apparel, land in Scotland inherited from their father, and “all the Merchant Goods lying in . . . [his] Lower warehouse.” Despite this legacy, there is no evidence that James ever worked as a merchant or that he was in partnership with his brother.[3]

Often referred to as a “joiner” or “cabinetmaker,” James probably trained in Hamilton or Glasgow and may have worked briefly as a journeyman in Britain before following his brother to Virginia at the age of twenty-three. The social and political connections that John had forged in the interim gave James an advantage over other recent émigrés. A year after James’s arrival, the Spotsylvania County Court paid him three hundred pounds of tobacco for making “a Square Black Walnut Table for the Justices Room.” No other records of furniture produced by Allan before 1755 are known, but the number of indentured servants associated with him suggests that he had a flourishing shop.[4]

In 1747 Allan’s “servant man” Robert Green testified against a convict servant man belonging to his master’s brother. The following year, Scottish parson Robert Rose noted that he had paid twenty-eight pounds for “a joiner from Mr. James Allan who has six years to serve.” This unnamed joiner may have worked in the cabinetmaker’s shop or simply been brought over by Allan in a speculative venture. A more specific reference can be found in the October 20, 1752, issue of the Virginia Gazette, where Allan reported the flight of a “Cabinet maker and Joiner” named Thomas Gray, who had been “imported by Indenture from London.” Court records pertaining to Gray and Allan indicate that the former countersued the latter for his “Sundry Joyners tools &c.” Allan also had a “Cabinett maker slave by name of Glasgow.” In his will, Allan left Glasgow and the slave’s “working tools” to his son, James.[5]

Only a handful of objects can now be associated with Allan’s shop, the most important of which are a pair of mahogany stands that belonged to George Washington (figs. 2-4). Washington’s patronage can be traced to 1756, when he commissioned Allan to make a bedstead and a military chest, possibly for use during the French and Indian War. In December 1759 Washington paid Allan £3.10 for “Mahogany stands.” Although the pair of stands represented by the example shown in figure 2 were once considered British and subsequently attributed to Williamsburg, evidence suggests that they are the ones Washington purchased from Allan. Washington’s records are meticulous in detail and contain no other reference to stands, torchères, or other forms that could match the surviving examples. Contemporary Virginia inventories indicate that basic stands cost about eight shillings each, or less than one pound per pair. In comparison, as noted, Washington paid £3.10 for his pair. Although that figure suggests that Washington’s stands were more elaborate than most, it seems insufficient to account for the stylish form, complex joinery, and exceptional carving of his examples. It is possible that Allan also received goods or services not recorded in Washington’s accounts.[6]

According to Washington’s 1799 inventory, the stands stood near a pair of fire screens in the “New Room.” The latter objects were probably the “2 Neat Mah[og]a[n]y Pillar & claw fire Screens India Paper on both Sides” that George received from London cabinetmaker Philip Bell in the fall of 1759 (fig. 5). Washington appears to have made a concerted effort to acquire furniture in the latest London style near the time of his marriage to Martha Custis.[7]

It is difficult to reconcile the advanced rococo style of the Washington stands with Allan’s training during the 1730s. Although cabinetmakers typically modified their work to accommodate new tastes and occasionally copied imported furniture, the Washington stands are clearly the product of a maker who trained at the height of the rococo style, probably in a large London shop. The design appeared in Genteel Household Furniture, published by the London Society of Upholsterers circa 1760 (fig. 6), shortly after Washington purchased his stands from Allan. Most design books included engravings of furniture already in production, and some designs were plagiarized from other publications. It is possible that stands identical to the one shown in Genteel Household Furniture were being made in London by the mid-1750s. Thomas Chippendale illustrated similar stands in the first edition of the Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754) (fig. 7).[8]

If Washington’s stands were made in Allan’s shop, they probably represent the work of indentured servants or journeymen who had worked in London during the mid- to late 1750s. The design and ornament of the stands suggest that they are the products of a joiner accustomed to producing similar forms and a professional carver (see figs. 2–4), either of whom could have been responsible for the design. Another possibility is that the stands are London objects retailed by Allan, but there is no evidence that he sold imported furniture. Moreover, when Washington wanted London-made furniture, he ordered it directly from London makers.

Accounts pertaining to James Allan’s work are scarce, but they demonstrate that his shop was capable of producing a variety of furniture forms. In 1774 Falmouth merchant William Allason sold twelve walnut chairs made by Allan to William Pyke of Berkeley County, Virginia. In addition to the cost of the seating, Pyke paid the “ferriage of James Allans men with [his] Chairs,” presumably across the Rappahannock River to Falmouth. County records and receipts submitted to members of the Lewis family between 1778 and 1799 reveal that Allan also made coffins and repaired furniture. His shop probably continued to produce furniture during this period, but no relevant documents have been discovered to date.[9]

A group of chairs with family or recovery histories in Falmouth, Spotsylvania County, Washington, D.C., and Maryland may represent the work of Allan’s shop. The earliest examples have unusual interlaced splats, often decorated with carved rosettes. Virtually identical splats are on a chair that reputedly descended in the Barrett family of Falmouth (fig. 8), a square-back example that descended in the Magruder family of Prince George County, Maryland, and the side chair illustrated in figure 9. A set of six chairs with a twentieth-century provenance in the Washington, D.C., area (fig. 10) has rosettes carved by a different hand and slightly different construction features, but all of the seating in this group has separate splat shoes that extend beyond the face of the rear rail and strips of wood that fill the void (fig. 8). While this feature is also found in seating from other regions, other traits common to chairs in this Virginia group are steeply coved shoes; rear stretchers positioned slightly higher than the side stretchers; medial stretchers dovetailed to the bottom of the side stretchers with a V-shaped joint exposed at the top; pierced brackets at the corners of the rails and front legs; and carved rosettes used in identical contexts. A chair that descended in the Spotswood family of Spotsylvania and Culpeper counties (fig. 11) has a replaced splat and is missing its shoe, but it retains enough original structure to attribute it to the same shop. Of all the chairs in this group, an example that reputedly belonged to Robert Thomas (1756–1823) of Spotsylvania County is the most stylistically divergent (fig. 12). The ears of the crest are notched and rounded, the splat has lobate, vertical piercings, and the front legs are molded, but the chair’s construction is consistent with other examples from this shop. The molding along the top of the seat rail matches that on the Spotswood chair, and the Thomas example has glue blocks and cross braces in the seat corners. The maker of the Barrett and Magruder chairs used glue blocks in the rear corners.[10]

Given the fact that James Allan produced furniture for clients as far away as Berkeley County, Virginia, it is reasonable to speculate that his patronage network extended from Falmouth to Culpeper County, Virginia, to southern Maryland. Although no direct link between Allan and the chairs illustrated in figures 8–12 is known, he is the most likely candidate for their production. The design and construction of this seating differ significantly from pieces attributed to Thomas Miller of Fredericksburg, William Walker of Falmouth, and Robert Walker of King George County. These were the only shop masters in the area known to have made high-quality furniture during the 1760s and 1770s. The fact that the rosettes on the Barrett and Magruder chairs and on the six chairs of the set represented by figure 10 are by different carvers strongly suggests that all of the examples in this group are urban products. Only a handful of carvers have been documented in the Falmouth-Fredericksburg area during this period. A list of indentured servants leaving England for Virginia in 1774 included Thomas Ford, a carver and gilder from London. It is possible that a craftsman like Ford began working for Allan during the 1770s and carved rosettes and other motifs that were already part of the shop’s vocabulary.[11]

James Allan may have trained his son and namesake. In 1789 Allan left James Jr. his shop, his slave cabinetmaker Glasgow, and the latter’s tools. Little more is known about James Jr. or his work. On May 24, 1799, the Virginia Herald reported: “Yesterday afternoon a violent Gust, from the westward, attended with rain and lightning, passed over this town, and blew down the workshop of Mr. James Allan....Several persons were in Mr. Allan’s shop, none of whom, tho’ buried in the ruins, were much hurt.” The phrase “several persons” suggests that Allan had apprentices and journeymen at the time. James Jr. died six years later, at which point Glasgow and most of Allan’s furniture were sold at auction.[12]

James Allanach may have been James Allan Sr.’s only competitor during the 1740s and 1750s. In 1753 the Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge paid Allanach three pounds for a chair. Given its considerable price, the chair was probably intended for the master of the lodge and either carved or painted with Masonic symbols. Very few American Masonic chairs from the mid-eighteenth century survive, but those that do show respect to the distinguished position of the sitter either through size, ornament, or symbolic design (figs. 13, 14). Presumably Allanach was trained as a cabinetmaker or chair maker, but no other records document his profession. He appeared before the Spotsylvania County Court sporadically between 1742 and 1752 and witnessed John Allan’s will in 1750. Allanach does not appear in local records after 1753, suggesting that he may have returned to Britain. Based on his name and social associations with other Scots in Fredericksburg, Allanach was most likely an immigrant, possibly from Aberdeen.[13]

The records of the Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, which was founded in 1752, are important in understanding local patronage and furniture production. Members included the landed elite, wealthy merchants from Fredericksburg and nearby Falmouth, and prominent tradesmen, several of Scottish descent. An armchair made for the master of the lodge during the mid-1770s (fig. 15) is one of the most ornate and historically significant seating forms surviving from eastern Virginia. Although oral tradition maintained that the chair was imported from Scotland, furniture historian Bradford L. Rauschenberg argued in a 1976 article that it and a less ornate Masonic armchair (fig. 16) were made in the Fredericksburg-Falmouth area. Since that time, debate has centered on whether the two chairs were made in the vicinity of these northern Virginia towns or in Williamsburg, as furniture scholar Wallace Gusler asserted in 1979 in Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790.[14]

When researchers for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts recorded the armchair illustrated in figure 15, local Masons reported that it had been made for the Falmouth lodge, located just across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg. Founded by Masons who considered it “inconvenient for them to attend . . . [the Fredericksburg] Lodge,” the Falmouth lodge was in existence from 1768 until circa 1800. Evidence suggests, however, that the armchair was commissioned by Masonic Lodge No. 4 and made in Fredericksburg. Since the Fredericksburg lodge was the more prominent of the two organizations throughout this period, it would have been the likely home for this important seating form.[15]

The designs of the two Masonic armchairs (figs. 15, 16) also suggest that they were made for different lodges. Although there are noticeable variations in the quality of the carved ornaments (figs. 17-19), both chairs are embellished with symbols representing the master, senior and junior wardens, the treasurer, the chaplain, and the secretary. The sundial on the Lodge No. 4 armchair is associated with Scottish Freemasonry, and the splats of both examples (figs. 18, 19) display images of the three great lights—the compass, square, and Bible—and the three lesser lights—the sun, moon, and worshipful master—represented by the candles atop the columns. The columns symbolize wisdom, strength, and beauty—the supports of the lodge. Even though Masonic iconography was not as standardized in the eighteenth century as it would become in the nineteenth century, it is unlikely that two armchairs with nearly identical symbols would have been considered appropriate for unequal positions within one lodge. In addition, no other colonial Masonic suites are known that include a master’s chair and a warden’s chair with identical iconography.[16]

The armchair illustrated in figure 16 was probably commissioned for the master of the Falmouth lodge. This theory would explain later confusion regarding the history of the more elaborate armchair (fig. 15) and offer a plausible explanation for the derivative design of the less ornate example. The Masons of Falmouth may have instructed the maker of their master’s armchair to incorporate features of its Lodge No. 4 equivalent to acknowledge the shared lineage of the two organizations.[17]

Documents pertaining to Lodge No. 4 record the purchase of two chairs, one from James Allanach in 1753 and another from Scottish immigrant Thomas Miller in 1773 or 1774 (figs. 20, 21). The armchair illustrated in figure 15 cannot be the Allanach chair since it has neoclassical motifs that did not appear in Virginia until the late 1760s or early 1770s. In fact, neoclassical decoration is rare on American decorative arts made before the Revolution.[18]

During the first decade of the Fredericksburg lodge’s existence, members held their meetings in local taverns. In 1763 private citizens, including a number of Masons, constructed a building in the center of the town, first known as the Town House and later as the Market House. Although the building was used for multiple purposes, including assemblies, balls, theatrical performances, and Masonic meetings, it also provided the members of Lodge No. 4 with a dedicated space to house ceremonial furnishings, records, books, and equipment. Lodge accounts refer to locks being put on the lodge room door, a level of security not available in public taverns. Having control of their own room allowed the Masons to purchase other ritualistic items, including two painted and gilded floorcloths from Glasgow.[19]

The members of Lodge No. 4 appear to have replaced and upgraded various accoutrements in the 1760s and 1770s. In addition to the Glasgow floorcloths, the Masons purchased jewels, gloves, aprons, and a silver square and compasses for the master of the lodge and hired James Allan to paint and gild the officers’ rods (fig. 21). The credit to Allan immediately preceded the entry for Miller’s chair, which probably replaced the one made by James Allanach. By 1773 the earlier chair had seen twenty years of use, and its design had most likely become antiquated.[20]

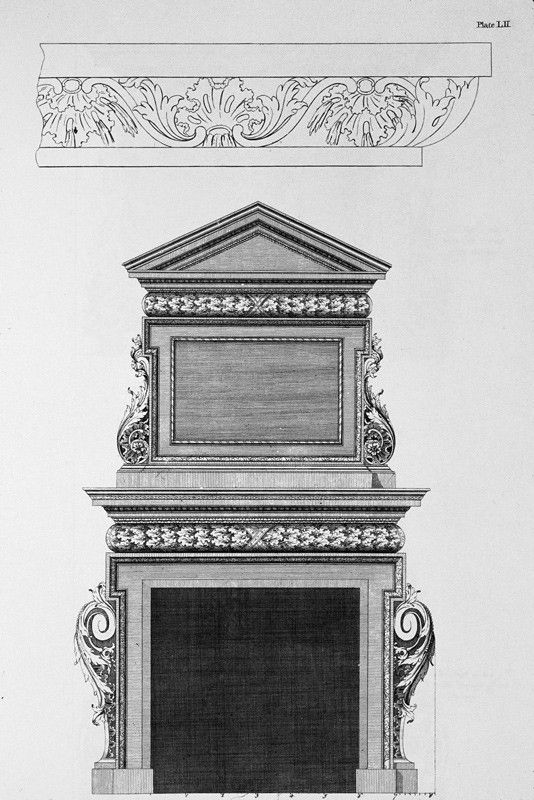

The style and construction of the Lodge No. 4 armchair (fig. 15) supports the theory that it is the one Miller made in 1773 or 1774. The armchair’s hairy paw feet, naturalistic foliage, bold gadrooned molding, and angular arms are consistent with British styles of the 1750s and 1760s. Indeed, many of the construction features are similar to those found on chairs made during the 1740s and 1750s by Robert Walker, a Scottish immigrant who worked in nearby King George County, Virginia (fig. 22). Details in common include knee blocks and gadrooning attached to the face of the seat rails rather than to the undersides; a one-piece rear rail and shoe; arms joined to the stiles with a large dovetail (fig. 23); large two-part, quarter-round vertical glue blocks inside the corners of the seat (fig. 24); and chamfering of the splat (fig. 25). Similar features also occur on mid-eighteenth-century British chairs. Perhaps the most idiosyncratic feature of the Lodge No. 4 armchair is its carved front seat rail (fig. 26), which may have been based on a frieze design in Abraham Swan’s The British Architect (1745) (fig. 27). Several cabinetmakers and builders in eighteenth-century Virginia owned copies of this publication.[21]

The small husks on the arm supports, the flute and rosette repeats on the shoe, and the molded stiles are neoclassical details (figs. 28, 29) that stand in contrast to the earlier features found on the Lodge No. 4 armchair. Neoclassical elements such as these first appeared in British furniture during the 1760s, but the “antique” or “palymarian” taste did not arrive in Virginia until the end of the decade. The royal governor, Lord Botetourt, imported some of the earliest known neoclassical objects in Virginia. In 1768 he purchased for the Governor’s Palace a set of early neoclassical side chairs from London cabinetmaker William Fenton (fig. 30). Two years later, Botetourt ordered for the Capitol a three-tier cast-iron stove with neoclassical imagery from Abraham Buzaglo of London (fig. 31).[22]

If Miller received his training shortly before emigrating from Scotland, that would explain the broad range of details manifest on the Lodge No. 4 chair. By the late 1760s George II, rococo, and Palladian classical styles had given way to the archaeologically based neoclassical conventions introduced by such prominent tastemakers as the Adam brothers. The construction of the armchair and its astonishingly close relationship to seating attributed to Robert Walker is more difficult to explain. While the cabinetmaker’s Scottish training could explain the number of corresponding details, another possibility is that Miller employed a journeyman who had worked in Walker’s shop.[23]

Although the composition of Miller’s shop may never be known, the ornament on the Lodge No. 4 armchair is obviously the work of a professional carver. Given the level of specialization in eighteenth-century trades, it is unlikely that Miller trained both as a chair maker and as a carver. The carver of the Lodge No. 4 armchair may have worked for Miller full time or on a commission basis, as was the case with most colonial specialists. Miller’s probate inventory listed “63 Chiezels & Gouges,” but it is impossible to determine whether these were conventional tools used by multiple joiners and chair makers or specialized carving tools. If the carver of the Lodge No. 4 armchair was responsible for the design of its ornament, he was as familiar with neoclassical tastes as the chair maker.[24]

Thomas Miller was born in 1748 in Stirling, Scotland, an ancient city located about halfway between Glasgow and Edinburgh. His father, Thomas (1720–1788), and older brother, John (1746–1808), were merchants. John first appears in Fredericksburg records in 1765, when he joined the Masonic lodge at the age of nineteen. Thomas joined the lodge three years later at the age of twenty.[25]

If Miller trained in Stirling, he may have become familiar with late rococo and early neoclassical details through architectural projects under way at that time. Architectural historians have suggested that William and John Adam, the father and elder brother of Robert Adam, designed the south front of the Touch House, located just outside that town. Under construction from 1757 to 1762, the interior spaces have delicate rococo ornaments furnished by Edinburgh plasterer Thomas Clayton. The involvement of urban craftsmen in this project shows how avant-garde rococo and neoclassical designs moved from style centers like Edinburgh to distant towns like Stirling. While serving his apprenticeship, Miller may have worked on furniture for buildings like the Touch House. Given the fact that patrons often commissioned furniture designed to resonate with specific interior spaces, it is no surprise that cabinetmakers and chair makers were influenced by architectural styles and motifs (fig. 32). The triglyphs and rosettes on the shoe of the Lodge No. 4 armchair, for example, have generic antecedents in the drawing room cornice molding in Touch House.[26]

Miller may have immigrated with his brother in 1765, but the first documentary reference to Thomas is in the accounts of Falmouth merchant William Allason. In May or June 1768 Thomas purchased goods pertaining to the cabinet trade under an account listing both him and his brother. Thomas was only twenty at the time, which may explain why John’s name was on the entry. The following September, Thomas placed two advertisements in the Virginia Gazette, one for a runaway convict servant “named George Eaton, born in London” who was “by trade a cabinet-maker,” and the other for “Journeymen Cabinet-Makers, well recommended.” A notice published four years later documents Miller’s continued use of convict laborers. Little is known about tradesmen who came to the colonies to escape punishment in Britain, but some were obviously highly skilled. If Eaton had trained or worked in London, he could have introduced styles current in that city.[27]

In 1769 the Fredericksburg lodge credited Miller for making “new Steps to the outer Door.” Like many cabinetmakers, he supplemented his income by doing architectural work. Miller’s 1802 probate inventory included numerous window sashes, window lights, and an unfinished house frame, suggesting that in later years his shop may have done more architectural work than cabinetmaking.[28]

Although no extant architectural work can be documented to Miller’s shop, two Fredericksburg houses have interior ornaments by the same artisan who carved the Lodge No. 4 armchair. One house, known today as the Chimneys, was probably owned by merchant John Glassell when the carving was installed, and the other, referred to as Kenmore (fig. 33), was built by Fielding and Betty Lewis between 1772 and 1775. The fiive-petal flowers on the appliqués in both houses (figs. 34-37) are virtually identical to those carved in relief on the back and front rail of the Lodge No. 4 armchair (fig. 38), and the outlining and shading of the leaves in all of these contexts is remarkably similar. Of all the carving associated with this anonymous tradesman, the mantel appliqués in Kenmore are the most complex. The appliqué in the small chamber to the left of the entrance is completely in the rococo style (figs. 34, 36), with a swan in the center and naturalistically rendered leaves and flowers on either side. The outlining, shading, and sculpting of this work is superior to the carving on the other appliqués in Kenmore, which is surprising given the hierarchy of the rooms and the fact that the most stylistically advanced appliqué is on the chimneypiece in the large dining room (fig. 39). The carving in the Chimneys (fig. 35) is much more restrained and probably slightly later than that in Kenmore.[29]

Circumstantial evidence suggests that Miller may have been involved with the work in Kenmore. Since his shop was located one block down Caroline Street from the Lewis home, it is highly likely that Fielding and Betty were familiar with Miller’s work. Fielding was also a member of the Fredericksburg Masonic lodge and would have known Miller through that connection.[30]

Carving by the same hand responsible for the architectural work and furniture mentioned above is also found on a set of cherry chairs that descended in the Waller family (fig. 40). The anthemions on the crests (fig. 41) are virtually identical to those on the mantel trusses in Kenmore’s large dining room (figs. 39, 42). Previous scholars attributed chairs from this set to Williamsburg based on the assumption that they descended from Benjamin Waller of that town; the original owner, however, was probably his son John (b. 1753), who served as clerk of the Spotsylvania County Court for twelve years beginning in 1774. John married in that year and probably commissioned the set of chairs soon after.[31]

Structural details also link the Waller chairs to the Lodge No. 4 armchair. Both the Masonic armchair (fig. 15) and its domestic counterpart (fig. 40) have arms that are joined to the rear posts with large dovetails (figs. 23, 43). More important, all of these seating forms have two-part glue blocks reinforcing their front rail and leg joints (figs. 24, 44), shoes that are integral with the rear seat rail, and oak slip-seat frames. The glue blocks on the Waller chairs are not rounded like those on the Masonic example, but minor variations often occur in the products of shops with multiple workmen. As is the case with most seating attributed to Robert Walker, the Waller chairs have arched rear seat rails. Although the rear rail of the Lodge No. 4 armchair is not arched, master’s chairs typically sat at the end of a room, where the back would not have been visible. A photograph of the Fredericksburg lodge taken during the 1930s shows the master’s chair on the dais in the center with its back to the wall (fig. 45).

Most chair makers offered a range of forms and decorative options designed to accommodate the tastes and budgets of their patrons. The side chair illustrated in figure 46 is attributed to Miller’s shop based on the lobate openings in the back, which were laid out with the same template used to make the Waller chairs. A related chair, possibly from the same set, has an oral history of descent in the Thornton family of Fall Hill, in Spotsylvania County just outside Fredericksburg. Documentary evidence also indicates that Miller produced seating forms that were cheaper and less ornate than the Waller chairs. In 1774 he made a set of twelve black walnut chairs valued at one pound each for Fredericksburg merchant George Weedon. The side chair illustrated in figure 46 may have cost approximately the same amount.[32]

Miller’s shop produced a variety of simple seating forms. A side chair that reputedly descended in the Little family of Fredericksburg (fig. 47) and the armchair shown in figure 48 share construction features with the previous group of chairs, including arched rear seat rails with integral shoes and virtually identical crest rail and shoe profiles. The side chair also has splat chamfering like that on the Waller and Thornton examples, while the armchair illustrated in figure 48 has an oak slip-seat frame and arms and arm supports of the same basic profile as those on the armchair from the Waller set. Moreover, the dovetails used to attach the arms to the rear posts are approximately the same size and shape as those on other seating attributed to Miller’s shop.[33]

The Little side chair and armchair illustrated in figures 47 and 48 may be slightly earlier than the seating that descended in the Waller and Thornton families (figs. 40, 46). On the former chairs (figs. 47, 48), the splats are less tapered in the middle and the backs are less raked. The armchair illustrated in figure 48 has quarter-round, two-part vertical glue blocks like those reinforcing the leg and seat rail joints of the Lodge No. 4 armchair as well as arms with flat, round terminals. These terminals appear to predate the delicately scrolled and carved ones on the Waller armchair.

The earliest seating attributed to Thomas Miller may date from the late 1760s, but all of the carved furniture associated with him was made during the following decade. Miller’s arrival in Fredericksburg and the expansion of his shop coincided with the decline of Robert Walker’s cabinet- and chair making business during the late 1760s. From the 1740s to the mid-1760s Walker was a dominant figure in the furniture-making trade in northern Virginia. His patrons included many of Spotsylvania County’s elite, some of whom were members of the Fredericksburg Masonic lodge. Regrettably there is not enough evidence to compare the size and composition of Miller’s and Walker’s shops or fully ascertain the level of patronage they received. Most of the information on Miller’s shop comes from his advertisements for journeymen and convict workmen, a 1796 assessment of his property, and his 1802 probate inventory. Miller’s shop was thirty-eight feet long and sixteen feet wide, which was fairly large for a small urban business. At the time of his death, Miller owned seven workbenches and a variety of tools including the sixty-three gouges and chisels mentioned earlier. Although he had the capacity to produce a significant amount of furniture, Miller may have turned increasingly to architectural work during the late eighteenth century. His inventory lists a variety of building components, but no unfinished chairs, tables, or casework. The sole indication of furniture production was a set of desk hardware and five sets of coffin mounts.[34]

Documents pertaining to Miller’s public life support the theory that his business changed. He joined the local militia in 1777 and may have served during the Revolutionary War. In 1782 Miller became a member of the Fredericksburg city council and assumed responsibility of the town fire engine, receiving public funds for its repair. He also served several terms as town geographer and gauger of liquors. In 1790 the town paid Miller £87.11.10 3/4 for repairing and extending the old courthouse and making temporary benches for the judges and an “attornies barr.” His shop routinely performed this type of work. In 1791 Miller charged James Pettigrew of Fredericksburg for cutting and installing panes of glass in the latter’s house.[35]

During the 1790s a Thomas Miller rented a house and plantation in Caroline County, Virginia, from Robert Gaines Beverley. While there is no evidence that Miller owned slaves who worked the property, he probably derived some income from renting and farming the land. Fredericksburg records mention a grain merchant named “T. Miller,” but it is unclear whether he and the cabinetmaker were the same man. Thomas Miller’s obituary, published in the Virginia Herald in 1802, described him only as “a respectable and very useful citizen.”[36]

Miller, Allanach, and Allan are the only shop masters documented in Fredericksburg before the Revolution. Allan and Miller each employed at least two indentured or convict cabinetmakers, but there is no evidence that any of these laborers continued to work in northern Virginia after their terms expired. Some may have moved west in search of greater opportunities, whereas others may have returned to Britain. The principal regional competitors with Allan and Miller were William Walker of Falmouth and Walker’s uncle, Robert Walker of King George County. Falmouth furniture maker Thomas Vowles was also active during this period, but he appears to have made simple joined and turned furniture rather than fine cabinetwork.[37]

A large group of clock cases with movements by Thomas Walker of Fredericksburg probably represents the work of one of these regional shops (figs. 49-51). The cases vary considerably in design, but all appear to date from the late 1760s to the mid-1780s. Allanach’s working dates and Vowles’s limited range of work exclude their shops as possible sources for the clock cases, and Robert Walker appears to have cut back or ceased production by the early 1770s. In contrast, the shops of James Allan, Thomas Miller, and William Walker were at their peak during this period.

The most ornate clock cases (fig. 49) are similar to contemporary examples from the Lancashire and Liverpool areas of England as well as Scottish derivatives. Because the Virginia cases are constructed like their British counterparts, they probably represent the work of an immigrant journeyman. Most colonial cabinetmakers and chair makers used their own construction techniques when interpreting or integrating new designs.

While one might assume that William Walker’s sibling relationship to Thomas Walker makes the former the most likely candidate to have made these clock cases, there is evidence to the contrary. As Robert Leath’s article in this volume of American Furniture indicates, chairs attributed to the shops of William Walker and his former journeyman Robert Cockburn are considerably less refined than the clock cases. Cockburn’s account book contains a rudimentary sketch of a clock case (fig. 52), but it does not resemble, much less match, the cases discussed here. Evidence also suggests that “Bill,” a journeyman who worked in Walker’s shop during the late 1760s and early 1770s, was trained in Virginia; thus he could not have been the source of urban British designs and structural features like those manifest in the clock cases. There is no evidence that Walker employed immigrant journeymen, as did his uncle Robert, James Allan, and Thomas Miller. William Walker may have trained his nephew Robert II, who probably made the case illustrated in figure 53. If that was the case and Walker’s shop was responsible for the Lancashire-style work shown in figures 49–51, one would expect Robert’s construction techniques and stylistic vocabulary to reflect the influence of his master. Convenience could have influenced the Walker brothers’ limited patronage of each other. Thomas’s shop was in Fredericksburg and William’s was located across the Rappahannock River in Falmouth. Although boats probably crossed the river on a regular basis, it may have been easier for Thomas Walker to acquire cases from a Fredericksburg artisan or vice versa.[38]

If the clock cases illustrated in figures 49–51 were made in Fredericksburg, they almost certainly originated in the shop of James Allan or Thomas Miller. All of the carving associated with Miller’s shop is by a single hand, and the work differs significantly from that on the clock case illustrated in figure 49. More important, no case furniture from Miller’s shop is known, which suggests that he may have focused on chair work. Miller arrived in Fredericksburg between 1765 and 1768; thus, he would have been between seventeen and twenty years of age when the earliest clock cases were made. If Thomas Walker was looking for a case maker during the late 1760s, it is more likely that he would have turned to James Allan, an established artisan who had a history of business dealings with the Walker family.[39]

During the last decade of the eighteenth century, Fredericksburg’s furniture-making community changed as new craftsmen began arriving in town and offering a wide range of fashionable goods. Falmouth cabinetmaker Thomas Vowles purchased a parcel of land on Caroline Street in 1792. Account book entries and court records suggest that he continued to produce turned and joined forms—flag bottom chairs, spinning wheels, chests, tables, bedsteads, coffins, bottle cases, and birdcages—similar to those he offered in Falmouth as early as 1768. The furniture market may have been stronger in Fredericksburg after the Revolution. On December 5, 1786, Olney Winsor described Fredericksburg as “one of the largest Towns in Virginia” but referred to Falmouth as “a small village.”[40]

On June 28, 1792, the Virginia Herald and Fredericksburg Advertiser reported that Philadelphia cabinetmakers Alcock & Gregory had opened a shop in town and were offering “any kind of Mahogany Furniture . . . equal to any on the continent.” Gregory disappeared from the partnership the following year, but John Alcock continued to advertise “Dining Tables, Breakfast and Tea Tables, Circular and Square Card ditto, Oval ditto, Bureaus, Chests of Drawers, Cellerettes, and Side Boards, Chairs, Secretaries and Book Cases, Bedsteads, &c.” Alcock probably produced furniture similar to that he had made in the North. In 1798 he advertised “A QUANTITY OF WINDSOR CHAIRS,” most likely seating made in Philadelphia and shipped to Fredericksburg. Although Alcock’s advertisements suggest that he had a large and prosperous cabinet shop, he must have felt that other pursuits would be more lucrative. In 1798 he informed his friends and customers that “he . . . [had] declined the above business, which . . . [would] be carried on at the same place in all its various branches [as formerly] by Mr. Alexander Walker, late of Falmouth.” Along with his business, Alcock also transferred the remaining years of his apprentice, Robert McKildoe, to Walker. Alcock operated a mercantile establishment in Fredericksburg for the next seven years.[41]

After completing his apprenticeship with Alexander Walker, Robert McKildoe opened his own cabinet shop in Fredericksburg in 1803. Shortly thereafter, McKildoe advertised “a hansom Clock & Case, with other pieces of furniture of the latest fashion, with plated & gilt mounting.” The following year he left Fredericksburg on the advice of John Alcock, who noted that the local demand for furniture “was not sufficient to support two shops.” Alexander Walker must have felt the same way since he required Alcock to sign a noncompetition agreement when he purchased the latter’s business in 1798.[42]

Despite Alcock’s misgivings, other cabinetmakers set up shop in town during the early nineteenth century. Thomas Nelson Walker moved into McKildoe’s vacated cabinet shop in 1804. He may have hoped to capitalize on the trade and patronage networks established by his father, who was the most successful clockmaker in the region. Thomas Sr.’s will stipulated that his sons Thomas and James receive several town lots when they attained majority and included the following bequest: “to either of my sons that shall actually follow & exercise my trade of clock and watch maker, all my tools and instruments belonging to said trade, Or if they [both] follow said trade I direct that said tools be equally divided between them.” Thomas became a cabinetmaker, and James continued in his father’s trade. Regrettably, little is known about Thomas Jr. after 1805.[43]

Robert Walker II opened his cabinet shop in Fredericksburg in 1802. On March 5 of that year, he advertised cabinetwork and reported that “the Turning Business . . . [would] be prosecuted by the subscriber in an extensive manner.” The tall clock case illustrated in figure 53 has a partially legible label stating “This clock and . . . made by Robert Walker 22nd Aug 1809 the movement . . . clock by Goldsmith Chandlee of Winchester in . . . 1 decemr: 18 . . . price of the case . . . 35 of the mov.mt . . . total price 88.” This inscription and Walker’s advertisement that “Gentlemen at a distance . . . may rely on the utmost punctuality” suggest that he made the case for a Shenandoah Valley customer who purchased the movement from Winchester clockmaker Goldsmith Chandlee. The tall, thinly necked pediment, serpentine upper edge of the waist door, and geometric panel above the waist door are details found on contemporary New York and New Jersey clock cases. Similar influences are apparent in the design of other clock cases made in Fredericksburg during the early nineteenth century, several of which have movements by local clockmaker John M. Weidemeyer. Either cases in this style were popular in the area or several northern cabinetmakers were active in Fredericksburg shops during the early nineteenth century.[44]

George D. Storke opened a shop in 1815. Census records indicate that his household included four men, who may have been part of his workforce, as well as a woman and a boy. Like several of his peers, Storke was unable to maintain his business. His inventory, which sold at auction in 1819, included “SIDEBOARDS and China Presses, Secretaries and Book Cases, Ladies’ Cabinets, Bureaus, Dining-Tables, Card do. Bedsteads Mahogany and Stained Wood, Easy Chairs, Candle-Stands, Wash do., Portable Desk, Spice Cases &c.” The number and range of forms suggest that Storke either had a relatively large shop capable of producing stock-in-trade or that he retailed furniture made by others. Storke left town in 1822.[45]

Based on the number of advertisements he placed in local newspapers, Alexander Walker appears to have been the most successful cabinetmaker in Fredericksburg during the early nineteenth century. As a third-generation cabinetmaker working in the Fredericksburg area and the son of William Walker of Falmouth, Alexander had social and business connections that gave him an edge over many of his newly arrived competitors. He purchased the shop of John Alcock in 1798 and the following year announced his intention to maintain a stock of “Windsor chairs of Superior Quality.” He also advertised for journeymen, noting that “the number of hands he means to keep, will enable him to turn off a great quantity of furniture . . . as good as can be imported.” On August 26, 1800, the Virginia Herald reported that Alexander’s shop manufactured “all kinds of Cabinet Ware” and carried on “the turning business in all its branches.” Like his competitor Robert Walker II, Alexander made a clear distinction between cabinetwork and turning. Alexander’s shop continued in operation until his death in 1830. Over the years his shop produced Windsor seating, tables, secretaries, bureaus, sideboards with or without china presses, tea tables, breakfast tables, dining tables, card tables, claw tables, center tables, sofas, bookcases, bedsteads, eight-day clocks, washstands, and candle stands. The 1820 census of manufacturers reported that his shop employed six men and two boys, used plank and scantling of almost every description, had a “Quantity of Brass Mountings for furniture which cannot be enumerated,” and sold about $3,000 worth of furniture per year. The census also noted “demand was limited, and Sale[s] dull at present.” In comparison, George Storke’s shop employed four men and one boy and sold about $2,000 worth of furniture per year. Alexander Walker’s will listed five “servants that work[ed] in the shop . . . Jim Page, Anthony, Levy, Jim Turner, Edmund Painter.” Whether these slaves were included in the 1820 census as employees is unclear.[46]

From 1802 until 1805 Walker was in partnership with James Beck, a Windsor chair maker and turner. In their first advertisement in 1802, Walker and Beck reported that they had commenced the “Windsor Business, in its various branches,” that they intended “to keep a constant supply of FANCY CHAIRS—stuff bottoms, Settees, and common Chairs of the newest fashions, and at northern prices,” and that they “shall in future manufacture mahogany Furniture at . . . Baltimore prices.” With the dissolution of the partnership in 1805, Beck advertised that he had opened his own business. In addition to turning, he intended to “manufacture Windsor-Chairs & Settees, With plain or stuffed bottoms . . . painted in different colours, gilt and japanned . . . Bedsteads . . . Mahogany, plain or carved; fancy, painted, gilt or japanned in different Colours.— ALSO Window Cornishes & Venetian Blinds.”[47]

During his partnership with Beck, Walker placed separate advertisements for “ELEGANT” cabinet furniture as well as Windsor chairs and settees. Among the items Walker listed were secretaries, bureaus, sideboards, breakfast tables, tea tables, card tables, bedsteads, and cabriole sofas. Walker apparently employed an inlay maker, since he also advertised “Fancy Stringing and inlaying executed with neatness and dispatch.” Although no furniture can be attributed to Alexander Walker or his predecessor John Alcock, side chairs that descended in the Green family of Fredericksburg (figs. 54, 55) could be from the shop of one of those men. The chairs are similar to contemporary seating from Baltimore and Philadelphia, which is significant considering that Alcock moved from Philadelphia to Fredericksburg and that Walker boasted he could compete with Baltimore prices. At the very least, the Green chairs represent the type of furnishings being produced in Fredericksburg during the late 1790s and early 1800s.[48]

James Beck’s work is more readily identifiable. Chairs marked “J. BECK” reputedly descended in the Waller family of Spotsylvania County and the Pollock family of King George County (fig. 56). Like the seating illustrated in figures 54 and 55, Beck’s Windsor chairs share features with Philadelphia and Baltimore work, suggesting that he may have come from one of those cities or been influenced by imported Windsors. The only other furniture associated with Beck is a lap desk signed by his daughter Mary Ann (fig. 57). A paper accompanying the piece is inscribed: “This writing desk was made in James Beck’s Furniture Factory in Fredericksburg Va. in 1806.” Beck continued to work in Fredericksburg until his death in 1821. Based on his probate inventory, Beck manufactured a variety of other cabinet furniture forms including desk-and-bookcases, secretary-and-bookcases, washstands, presses, tables, bedsteads, and chairs. He also owned three slaves who worked in his shop.[49]

The changing face of Fredericksburg’s cabinet shops at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries was largely due to an evolution in the town’s economy. Whereas previously the city had relied heavily on the transatlantic tobacco trade, the coastal trade in grain grew in importance at the turn of the century. Wheat, corn, and flour from western counties like Culpeper, Orange, Rockingham, and Shenandoah were handled by Fredericksburg merchants and shipped to Norfolk, Alexandria, New York, and Philadelphia. Whereas Fredericksburg had been the major regional center for the collection of inland produce during the eighteenth century, other port cities such as Alexandria, Baltimore, and Philadelphia began to draw on the same inland regions and, over time, pulled much of the grain trade away from Fredericksburg. The city’s decreasing regional significance and increased reliance on coastal trade led to its greater dependence on manufactured goods from those same port cities, thus reducing its ability to support and grow its own manufacturing industries.[50]

Imported furniture from northern cities brought competition to local furniture makers and forced them to change established business practices. Some cabinetmakers attempted to mimic northern styles, but few were able to produce comparable forms at competitive prices. The shop responsible for several clock cases with movements by John M. Weidemeyer is one of the most notable exceptions, but the success of that cabinet business may have been influenced by the clockmaker’s patronage and the desire of local patrons to have movements specifically fitted to cases. The challenges facing Fredericksburg cabinetmakers were both stylistic and economic. Alexander Walker responded to these pressures by offering a wide range of furniture forms and maintaining stock-in-trade that probably consisted of cabinet ware and seating made in his own shop as well as imports. In many respects, he followed the model of large urban manufactories, as did many of his contemporaries in Petersburg, Norfolk, and other Virginia cities.[51]

As was the case in many of eastern Virginia’s larger towns, craftsmen of British descent dominated the cabinetmaking trade in Fredericksburg before the Revolutionary War. Although only two or three shops were active during that period, the level of work they produced was exceptional by colonial standards (figs. 2, 8, 15, 16). The market for furniture changed dramatically after the war, as additional shops opened and competed with each other and with northern imports. Whereas James Allan and Thomas Miller had employed immigrant journeymen to satisfy tastes for the latest British styles, shop masters active during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries followed urban business models and incorporated details from northern furniture to meet the changing demands of their patrons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their kind assistance with this research project and article, the author thanks Ronald L. Hurst, Robert A. Leath, Luke Beckerdite, Gavin Ashworth, Carol Borchert Cadou, Mary Helen Dellinger, Matthew A. Webster, and the members of Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4.

Paula S. Felder, Forgotten Companions: The First Settlers of Spotsylvania County and Fredericksburgh Town (Fredericksburg, Va.: Historic Publications of Fredericksburg, 1982), pp. 32–33, 79–80. William Byrd, “A Progress to the Mines in the Year 1732,” in The Prose Works of William Byrd of Westover, edited by Louis B. Wright (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966), p. 368. Andrew Burnaby, Travels through the Middle Settlements in North America, 2nd ed. (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1968), p. 63.

According to David Young, Assistant Research Librarian for the Hamilton Town House Library, John Allan Sr. was a bailie of Hamilton from 1715 to 1718 and a councillor from 1707 until possibly 1722 (David Young to Tara Chicirda, January 26, 2005). Will of Christian Allan, Hamilton and Campsie (Scotland) Commissary Court, 1785, pp. 302–8. Stuart N. Butler, “The Glasgow Tobacco Merchants and the American Revolution, 1770–1800” (Ph.D. diss., University of St. Andrews, 1978), pp. 15–16, 29, 43, 278, 194, 298–99, 312, 315, 317, 319, 321. Lachlan Campbell, Walter Coloquoun, James Freeland, Gavin Lawson, Robert Lawson, Neil McCoull, Henry Mitchell, James Robb, James Somerville, and David Blair were all Scots who began their careers in Fredericksburg or Falmouth as factors or partners in Glasgow mercantile firms. Jacob M. Price, “The Rise of Glasgow in the Chesapeake Tobacco Trade, 1707–1775,” William and Mary Quarterly 11 (1954): 193–95.

John Allan first appears in the Spotsylvania County Court records October 1, 1734 (Spotsylvania County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1734–1735, edited by Ruth Sparacio and Sam Sparacio [McLean, Va.: Antient Press, 1991], p. 63). Butler, “The Glasgow Tobacco Merchants and the American Revolution,” p. 9. Spotsylvania County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1742–1744, edited by Ruth Sparacio and Sam Sparacio (McLean, Va.: Antient Press, 1996), p. 13. Paula S. Felder, Fielding Lewis and the Washington Family (Fredericksburg, Va.: American History Co., 1998), p. 94. Felder, Forgotten Companions, pp. 109, 182. Spotsylvania County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1744–1746, edited by Ruth Sparacio and Sam Sparacio (McLean, Va.: Antient Press, 1996), p. 125. Will of John Allan, Spotsylvania County Will Book B, 1749–1759, April 3, 1750, microfilm, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

Old Parish Records, Hamilton, Lanarkshire, Scotland, p. 70. James Allan was born on July 15, 1716, and his parents were Hamilton merchant James Allan and his wife, Margaret (Black). Spotsylvania County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1740–1742, edited by Ruth Sparacio and Sam Sparacio (McLean, Va.: Antient Press, 1992), p. 105. For the table, see entry dated July 1, 1746, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1738–1749, edited by Ruth Sparacio and Sam Sparacio (McLean, Va.: Antient Press, 1996), p. 93, as cited in the research file for Spotsylvania County chair maker Henry Head, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (hereafter cited as MESDA). The court purchased rush-seated chairs from Head a few years after commissioning the table.

Sparacio and Sparacio, Spotsylvania County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1738–1749, p. 428. Virginia Gazette, October 20, 1752. “Servant man” Robert Green had to appear in court to testify that convict servant Phillip Allan had stolen a broadcloth coat from James Allan. Ralph Emmett Fall, The Diary of Robert Rose: A View of Virginia by a Scottish Colonial Parson (Verona, Va.: McClure Press, 1977), p. 29. Spotsylvania County Court Order Book, 1749–1755, p. 183, as cited in MESDA research file for Thomas Gray. Will of James Allan, June 25, 1798, Fredericksburg, Virginia, District Court, Will Book A, 1789–1830, pp. 124–25, microfilm, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

Virginia Herald, April 30, 1799: “Departed this life on Sunday morning last after a long, and pa[inful] illness . . . he bore with uncommon patience and soggitude, Mr. James Allan Sen.—aged 84 years and two days a gentleman greatly esteemed and respected—He was a Native of Scotland and arrived in this town in April 1739—where he resided till his death.” George Washington, Ledger A of George Washington (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1922), pp. 30, 62. The Papers of George Washington: Colonial Series, edited by W. W. Abbot, 10 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983–1995), 2: 205. http://gunstonhall.org/ probate/inventory.htm. A search of the elite Virginia inventories in the Gunston Hall Probate Inventory Database revealed that the values of candle stands ranged from two shillings to seventeen shillings and six pence. The values for stands described as being made of mahogany ranged from eight shillings to fifteen shillings.

Inventory of George Washington, Fairfax County Will Book J, 1810–1806, fol. 326, Fairfax County Court Archives. John J. McCusker, How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Commodity Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (Worcester, Mass.: American Antiquarian Society, 2001), pp. 69–70. In 1759 £100 sterling equaled £139.97 in Virginia currency. Abbot, The Papers of George Washington, 6: 334–35.

London Society of Upholsterers, Genteel Household Furniture (London, ca. 1760–1763), pl. 72. Abbot, The Papers of George Washington, 5: 50, 88; 6: 317, 334–35, 463; 7: 27, 310–11, 372, 397. Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754), pls. 120–23. Chippendale illustrated the same stands in the second edition (1755).

Sparacio and Sparacio, Spotsylvania County, Virginia Order Book Abstract, 1738–1749, p. 105. Fall, The Diary of Robert Rose, p. 29. Abbot, The Papers of George Washington, 2: 205. Washington, Ledger A of George Washington, p. 30. Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge Record Book, 1773–1774, Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M., Fredericksburg, Va. William Allason Papers, Ledger Book 2, pp. 133, 190, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Edward Dixon Day Book, April 16, 1764 (Spotsylvania County); John Frederick Dorman, Saint George’s Parish, Spotsylvania County, Virginia, Vestry Books, 1726–1817 (Fredericksburg, Va., 1998), pp. 171, 173; St. George’s Parish, Will Book E, 1772–1798, pp. 1324, 1432; Fredericksburg City, Virginia, Wills, 1782–1817, p. 124; “A Statement of Money Received and Paid on the Account of the Estate of Mrs. Mary Washington, Decd,” December 1789–August 13, 1790, all as transcribed in the artisan file on James Allan, MESDA. Receipts from James Allan, July 11–October 1, 1792, October 1793, Kenmore Manuscript Collection, Fredericksburg, Virginia. Mountjoy vs. Lowry &c, Fredericksburg Court Records, CR-SH-H, 189-25.

Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry N. Abrams for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997), pp. 99–101. Several Boston-area chairs with splat designs similar to those of the Virginia examples (figs. 8–10) are known, the earliest of which were almost certainly copied from imported British chairs that belonged to Boston merchant William Phillips. For more on these New England chairs, see Luke Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” in New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno Forman, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 123–33; and Mary Ellen Hayward Yehia, “Ornamental Carving on Boston Furniture of the Chippendale Style,” in Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, edited by Walter Muir Whitehill (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974), p. 221. The Barrett family chair retains its original brackets.

See Robert Leath’s article in this journal for information on the work of William and Robert Walker. The Journal of John Harrower: An Indentured Servant in the Colony of Virginia, 1773–1776, edited by Edward Miles Riley (Williamsburg, Va., distributed by Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1963), appendix II, p. 167.

Will of James Allan. James Allan Jr. also inherited James Sr.’s property in Fredericksburg, including “the two lotts and buildings . . . whereon I live . . . numbered 64. 124.” Since James Jr. does not appear to have sold any of the property, it is likely that the workshop remained in his possession. Virginia Herald, May 24, 1799. Spotsylvania County Will Book G, 1804–1810, pp. 405–6, microfilm, Library of Virginia.

Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge Record Book, March 3, 1753. Virginia County Records: Spotsylvania County, 1721–1800, edited by William Armstrong Crozier (New York: Fox, Duffield & Co., 1905), pp. 10, 58, 161–62. There is no record that James Allanach died in Virginia or moved west. Family Search International Geneological Index, www.familysearch.org. A James Allanach, son of Alexander Allanach, was christened in Strathdon, Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1715. Another James was christened in 1737. In March 1746 John Mercer debited Stafford County builder William Walker £30.8 for fourteen carved chairs made by King George County chair maker Robert Walker (John Mercer Ledger Book, 1741–1750, p. 36, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation). This averages out to £3 per armchair and £2.0.8 per side chair. These highly carved chairs descended in the Ferneyhough family, and an armchair from the set is at the Mary Ball Washington House in Fredericksburg, now owned by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Two Outstanding Virginia Chairs,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 2, no. 2 (November 1976): 1–23. In 1979 Wallace Gusler attributed the master’s chair from Lodge No. 4 to the Anthony Hay shop of Williamsburg and ascribed its carving to George Hamilton, a Scottish immigrant who arrived in Virginia in 1774 (Wallace B. Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 [Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1979], pp. 92–95, 170).

As quoted in J. Travis Walker, A History of Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4, A. F. & A. M. (Fredericksburg, Va.: Sheridan Books, 2002), pp. 22–23.

The symbol of the master is the square, the symbol of the senior warden is the level, the symbol of the junior warden is the plumb rule, the symbol of the treasurer is crossed keys, the symbol of the chaplain is an open Bible, and the symbol of the secretary is crossed quills. For more on Masonic imagery, see Scottish Rite Masonic Museum of Our National Heritage, Bespangled, Painted and Embroidered: Decorative Masonic Aprons in America, 1790–1850 (Lexington, Mass.: Scottish Rite Masonic Museum of Our National Heritage, 1980), pp. 118–21; and F. Cary Howlett, “Admitted to the Mysteries: The Benjamin Bucktrout Masonic Master’s Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 195–232.

The chair illustrated in figure 16 may be from William Walker’s shop, but its derivative design makes an attribution problematic.

On March 3, 1753, the lodge “Paid to James Allanach for a Chair £3.0.0” (Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge Record Book, 1752–1771). In 1773–1774 the lodge credited Thomas Miller five pounds “in part of a chair &tc.” (The year, month, and date section of the page with this entry is torn, and the page is out of order, but the years can be determined from the corresponding debit page at the end of the book.) Graham Hood, “Early Neoclassicism in America,” Antiques 140, no. 6 (December 1991): 978–85.

Felder, Fielding Lewis and the Washington Family, pp. 176–77. Fredericksburg City Council Minutes, 1782–1798, June 20, 1782, p. 36, transcription at http://departments.umw.edu/ hipr/www/Fredericksburg/councilminutes. Lodge members contributed to the repairs of the Market House on the condition they “be allowed the Free use of the upper Rooms of the Market House for the purpose of holding Lodges at any time and at all times for and during, the continuation of any regular Lodge of this town.” Ronald Heaton, The Lodge at Fredericksburg (Silver Springs, Md.: Masonic Service Association, 1981), pp. 13–15. Walker, A History of Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4, pp. 19–21.

Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge Record Book, Contra Cr., 1773–1774. Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge Record Book, meeting minutes, February 28, 1767.

See Robert Leath’s article on Robert Walker in this volume. E-mail from Scottish furniture historian David Jones to Tara Chicirda, January 12, 2005. Abraham Swan, The British Architect (London, 1758), pl. 52. Several Virginia woodworkers including cabinetmaker and house joiner Mardun V. Eventon of King William County and carver William Bernard Sears of Richmond and Fairfax counties owned or used English architectural design books including those by Batty Langley and Abraham Swan. Robert F. Dalzell Jr. and Lee Baldwin Dalzell, George Washington’s Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 165–66. Hurst and Prown, Southern Furniture, pp. 462, 464.

Hood, “Early Neoclassicism in America,” pp. 978–85. Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, pp. 7–10, 94. Graham Hood, “American or English Furniture?” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), pp. 139–40. William Fenton’s invoice included two sets of “12 mohogany Chears Covered with hair Seating and Double Brass nailed” (Hood, “American or English Furniture?” p. 139). Two sets of mahogany chairs originally covered in horsehair and decorated with double rows of brass nails were reputedly among Lord Dunmore’s furnishings sold at auction in 1775 (see accession files 1985-259 and 1985-260, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation). Inventories of the Governor’s Palace and Dunmore’s purchases at Lord Botetourt’s sale suggest that the two sets of chairs were the ones Botetourt purchased from William Fenton in 1768.