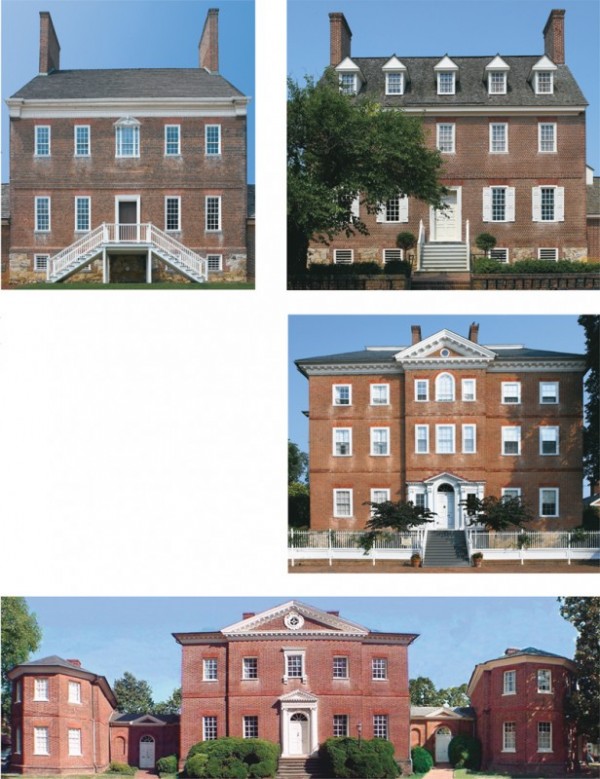

Composite illustration showing, clockwise from top left, four of the most significant houses built during Annapolis’s age of affluence: (a) James Brice House (1767–1773), (b) William Paca House (1763–1775), (c) Chase-Lloyd House (1769–1774), (d) Hammond-Harwood House (ca. 1774). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 37 1/2", W. 21 3/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Several chairs similar to this example have been documented or attributed to Shaw’s shop.

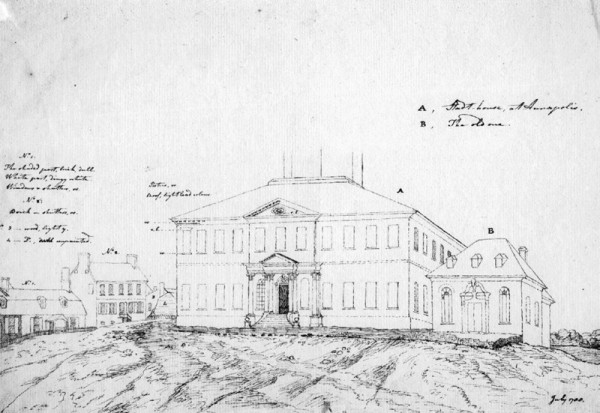

Charles Willson Peale, Front Elevation of the Maryland State House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1788. Pen and ink on paper. 7 3/4" x 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, William Voss Elder Collection.)

Maryland State House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1772–1779. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This photograph shows the original entrance of the State House. The portico was replaced in 1882, but this was the primary entry for the capitol until the completion of the 1902–1905 annex on the opposite side of the building.

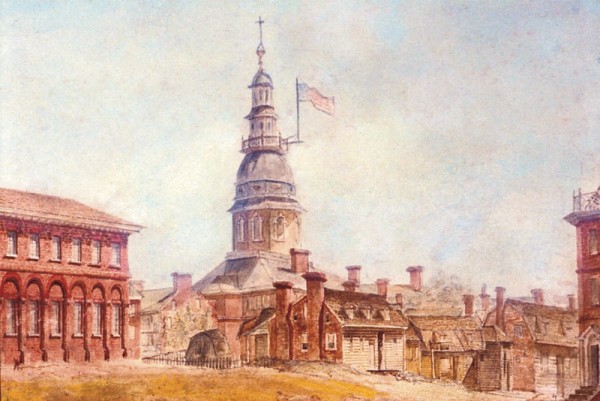

Detail of Charles Cotton Millbourne, View of Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1794. Watercolor on paper. 10" x 16 5/8". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association.) The State House, depicted in the center, dominated a landscape that changed very little in the decades that followed the Revolution. Cabinetmaker John Shaw procured the flag shown on the dome for the 1783–1784 meeting of the Continental Congress in Annapolis.

Charles Willson Peale, A Front View of the State-House &c. at ANNAPOLIS the Capital of MARYLAND, ca. 1789. Engraving on paper. 4 3/4" x 6 5/8". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, Bond Collection.) This image, which appeared in the Columbian Magazine in February 1789, shows the State House soon after the completion of the dome. Other buildings visible on State House Circle include the home of John Shaw (far left), the council chamber and ballroom (built ca. 1718) (right), the octagonal outdoor privy known as the “public temple,” and the treasury building (built 1735–1736).

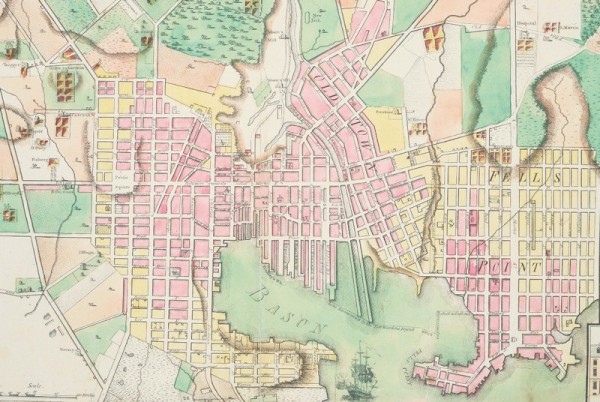

Detail of Warner & Hanna’s Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore, 1801. Watercolor on paper. 28 1/2" x 20". (Courtesy, George Peabody Library Collection, Johns Hopkins University.) This image shows the extent and potential for Baltimore’s growth at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

John Shaw House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1720–1725. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress.) By the time this photograph was taken (before 1890), Shaw’s house had been enlarged several times. The widow’s walk may have been installed before 1820, and the front porch was probably extended in the beginning of the twentieth century.

Cellaret probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1795. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 28 1/4", W. 29 3/4", D. 14 3/4". (William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis [Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983], p. 101.)

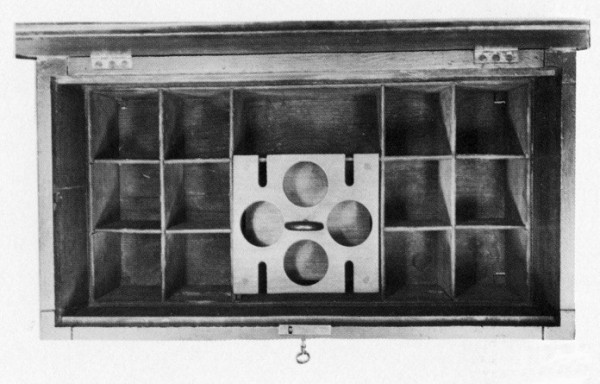

Detail showing the interior of the cellaret illustrated in fig. 9. (William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis [Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983], p. 102.)

Cellaret attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1795. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 28 1/4", W. 29 3/4", D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cellaret is nearly identical to the one illustrated in fig. 9.

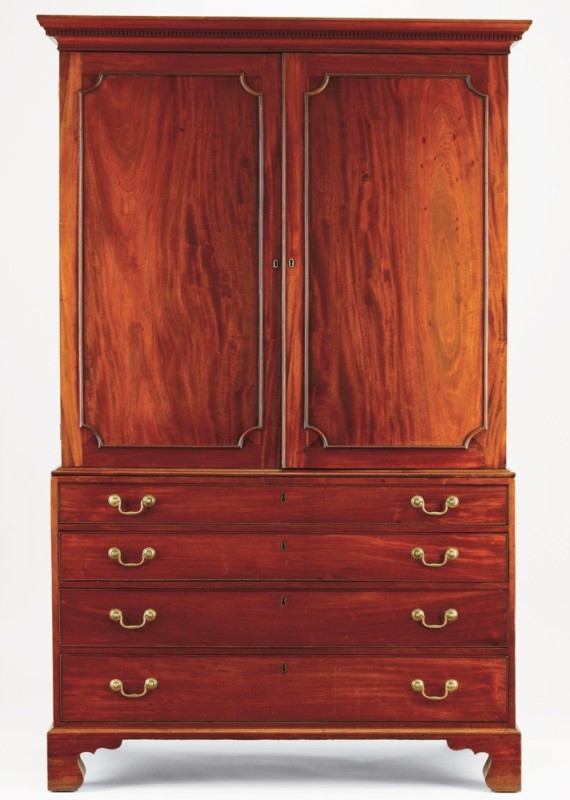

Clothespress probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1795. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 81 1/2", W. 49 7/8", D. 25". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

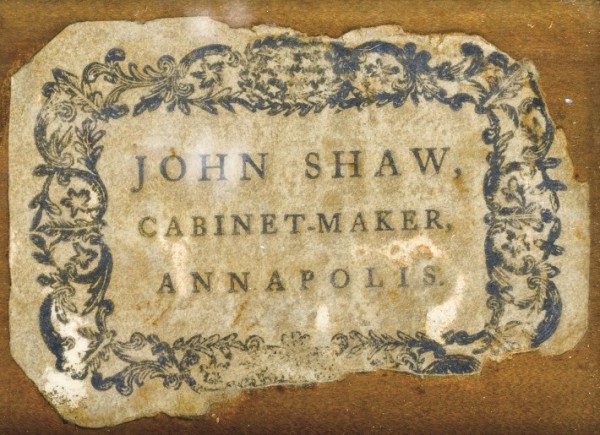

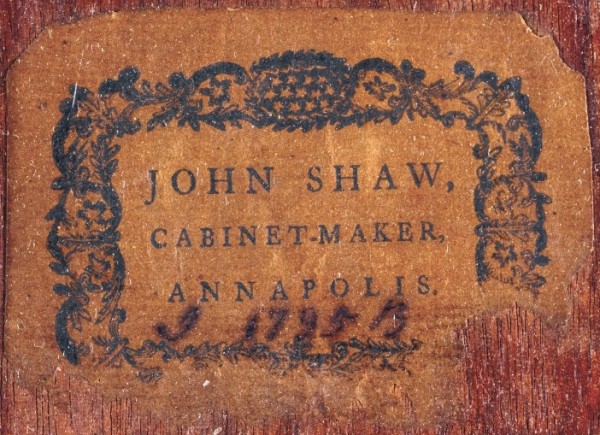

Detail of the label on the clothespress illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of one of the laminated glue blocks supporting the case and feet of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Clothespress probably made by a journeyman whose initials were “JB,” in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1795. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 80 1/4", W. 51 3/8", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The initials on the label may be those of John Walter Battee, “aged eighteen years the 18th day of November 1793,” who apprenticed to John Shaw on November 5, 1793, to “learn the . . . business of Cabinet Maker & Joiner to serve until he be of Age of which will happen on the eighteenth Day of November 1796” (Anne Arundel County Register of Wills, Orphans Court Proceedings, liber JG1, February 14, 1794, fols. 415–16, MSA C 125-4). The initials and date on the label correspond with Battee’s tenure with Shaw, and he may also be responsible for the “J 1796 B” on the label on the bureau with secretary drawer illustrated in fig. 25. It is not known whether Battee continued making furniture after concluding his apprenticeship in November 1796.

Detail of the label on the clothespress illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of one of the laminated glue blocks supporting the case and feet of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Clothespress probably made by a journeyman whose initials were “JH” in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with yellow pine. H. 92", W. 51 1/2", D. 25". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, Friends of the American Wing Fund, BMA 1976.76.)

Detail of one of the laminated glue blocks supporting the case and feet of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 18.

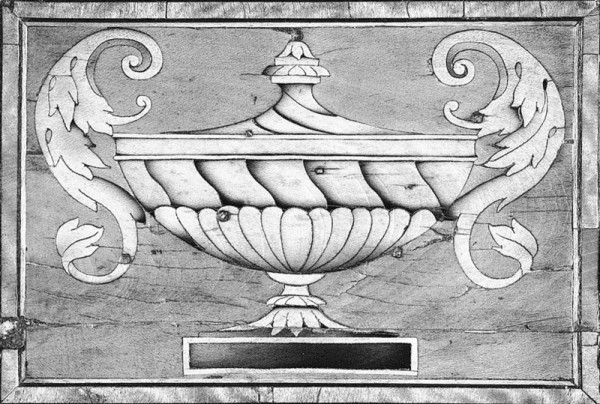

Detail of the urn inlay on the center tablet of the pediment of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 18.

Card table probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1796. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white oak. H. 28 3/4", W. 36", D. 17 3/4" (closed). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the label on the card table illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the card table illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the fly rail hinge and alignment mortise and tenon on the leaves of the card table illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bureau with secretary drawer probably made by a journeyman whose initials were “JB” in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1796. Mahogany, mahogany veneer and lightwood inlay. H. 43", W. 44 3/4", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This bureau has vertical back boards that are set in rabbets in the sides and top and secured with nails. The dustboards occupy the full depth of their dadoes and extend all the way to the back of the case. The case and feet are supported by square vertical glue blocks that butt against triangular blocks that fill the space between the bottom of the case and bottom edge of the front and side moldings.

Detail showing the construction of the small drawers in the writing compartment of the bureau illustrated in fig. 25. Different techniques were used in the construction of the drawers indicating that at least two different artisans collaborated in the production of this piece.

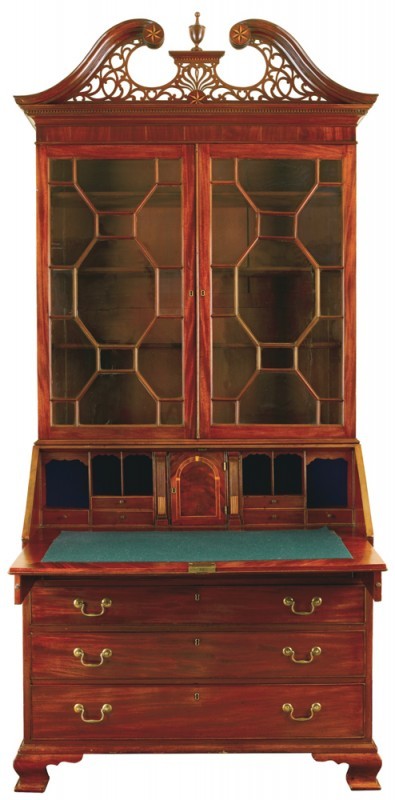

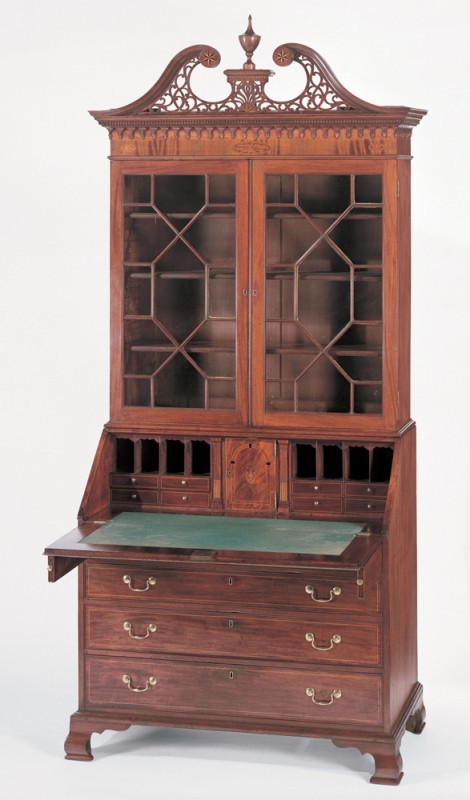

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 98 1/4", W. 47 3/8", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

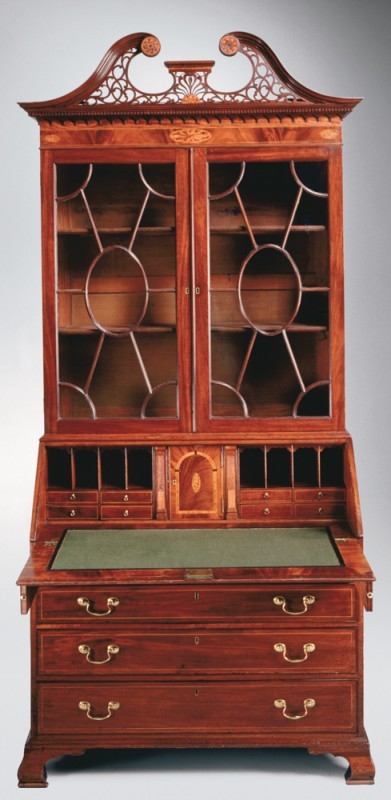

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1790–1800. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 98", W. 46", D. 24". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

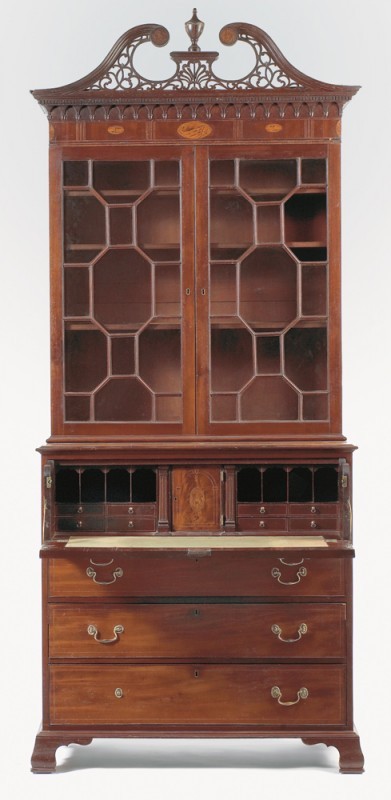

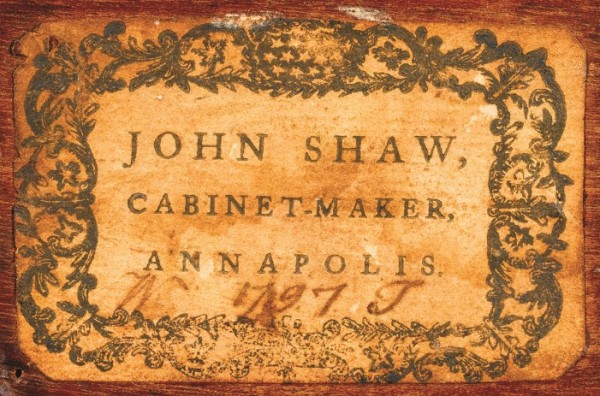

Desk-and-bookcase probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white oak. H. 98 5/8", W. 45 3/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, White House Historical Association (White House Collection); photo, Bruce White.) The Shaw label on this desk-and-bookcase is inscribed “W 1797 T,” as are the labels on the card table and clothespress illustrated in figs. 12 and 21.

Secretary-and-bookcase probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 105", W. 45 1/2", D. 21 5/8". (Courtesy, Christie’s; photo, Ellen McDermont.) The secretary-and-bookcase has an upper case with a four-panel back, a lower case with horizontal backboards that are nailed into rabbets in the top and sides, feet with square, laminated glue blocks, and a red wash or pinking on many of the secondary surfaces.

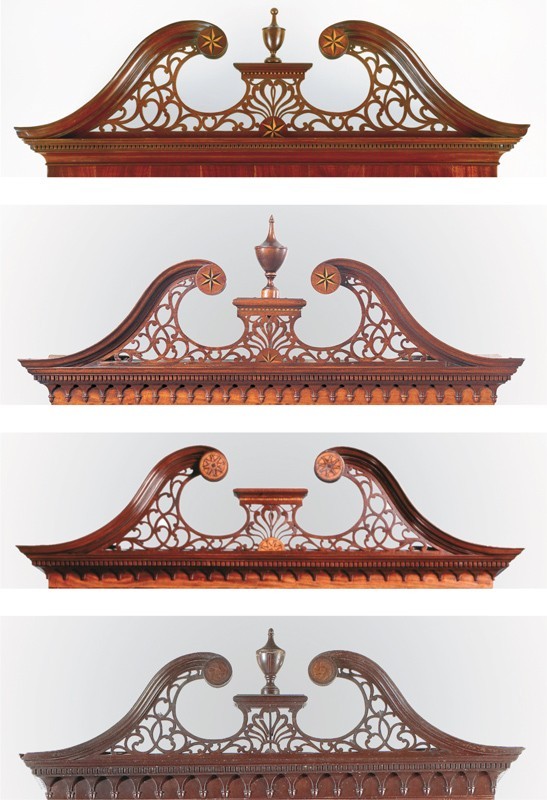

Composite detail showing the pediments of the desk-and-bookcases and secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in (from top to bottom) figs. 27–30. Shaw purchased most of his inlays from Baltimore specialists, including the eagles on the card table illustrated in figs. 21 and 23 and prospect door of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in figs. 30 and 33, and much of the other work illustrated in this article. A few inlays, like the urn on the pediment of the press illustrated in figs. 18 and 20, may represent British imports.

Detail of the inlaid shell on the fallboard of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 29.

Detail of the eagle inlaid on the prospect door of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the label on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 29. (Courtesy, White House Historical Association; photo, Bruce White.)

Composite detail showing the front and rear foot blocking and base construction of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 29.

Composite detail showing the front and rear foot blocking and base construction of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left front foot on the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the Old Senate Chamber, Maryland State House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1772–1779. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This space served as the senate chamber from 1779 until 1906. The illustrated furnishings represent a combination of eighteenth-century objects made in Shaw’s shop and twentieth-century pieces made in the shop of Baltimore cabinetmaker Enrico Liberti.

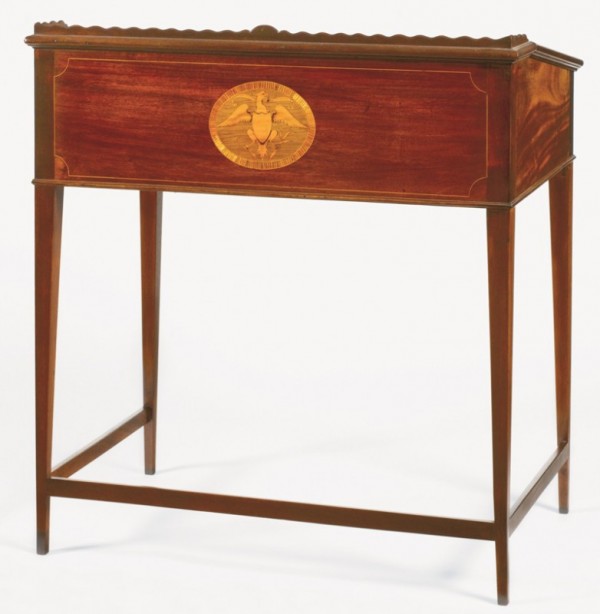

President’s desk probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 38", W. 35 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the label on the desk illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlaid eagle on the desk illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk made in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 35", W. 24 1/2", D. 21". (Collection of Charles Heyward Meyer; photo, William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis [Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983], p. 133.)

Detail of the label on the desk illustrated in fig. 42. The signature on the label reflects the work of Washington Tuck when the desk was repaired in Shaw’s shop in 1801.

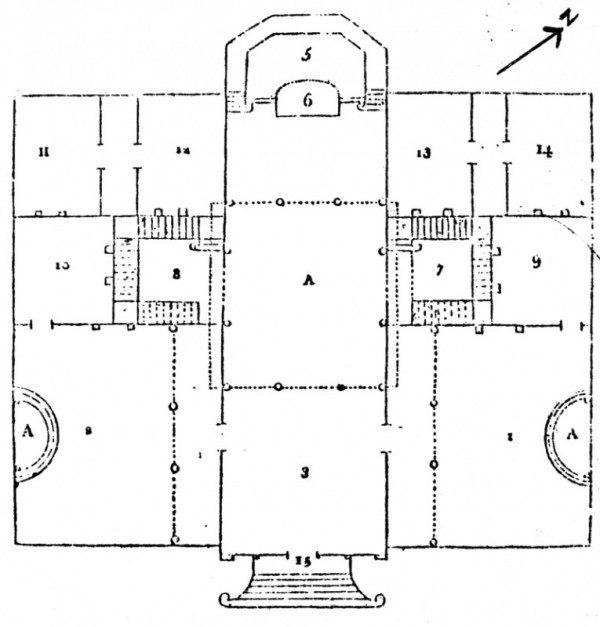

“The Ground Plan of the State-House at Annapolis,” The Columbian Magazine, February 1789. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, State House Graphics Collection.) Known as the “Columbian Plan,” this document indicated the position of the senate and house of delegates chambers and committee rooms, the general court (abolished in 1805 and its jurisdiction replaced by the court of appeals), and the record offices of the chancery court, general court, land office, and register of wills on the first floor. Located on the second floor were the council chamber (above the senate chamber), auditor’s chamber (above the house chamber), two jury rooms for the courts, and the repositories for arms above the record offices. The floor plan was classically Georgian, with the senate chamber to the right of the main door and the house of delegates chamber to the left. The two chambers were the same size and mirror images of each other, with raised podiums or “thrones” for the president and the speaker in the center of the rooms, and a visitor’s gallery at the back of each chamber.

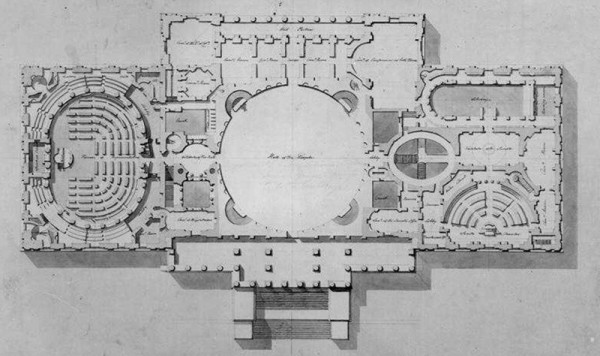

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Plan of the Principal Story of the Capitol, U.S.,” Washington, D.C., 1806. Graphite, ink, and watercolor on paper. 19 1/2" x 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.) William Tuck likely saw the semicircular, tiered layout of the House of Representatives’ chamber on the left when he visited the Capitol in 1807. Latrobe depicted the furniture in the House chamber as a combination of straight and curved desks.

Speaker’s desk made in the shop of William and Washington Tuck, Annapolis, Maryland, 1807. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with yellow pine. H. 32 3/4", W. 36 1/4", D. 23". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Choate, 63.12, © 2007, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Front view of the desk illustrated in fig. 46.

Detail of the inlay on the right rear leg of the desk illustrated in fig. 46.

Detail of a wooden knob on the desk illustrated in fig. 46.

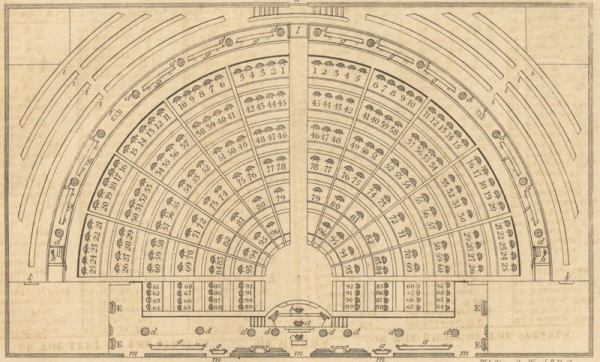

“Hall of the House of Representatives,” from Peter Force, National Calendar, 1823. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.) The furnishing scheme of the house of delegates chamber in Annapolis closely resembled that of the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C., in which straight desks were placed to the sides of the dais, while curved desks were symmetrically arranged in front of the speaker.

Late-nineteenth-century photograph showing Washington Tuck’s house on State House Circle, Annapolis, Maryland, 1820–1821. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, George Forbes Collection.)

G. W. Smith, The State House at Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1810, illustrated in Morris Radoff, The State House at Annapolis (Annapolis: Hall of Records Commission of the State of Maryland, 1972), p. 32. This image shows the State House as it probably appeared soon after the completion of the Tucks’ 1807 commission.

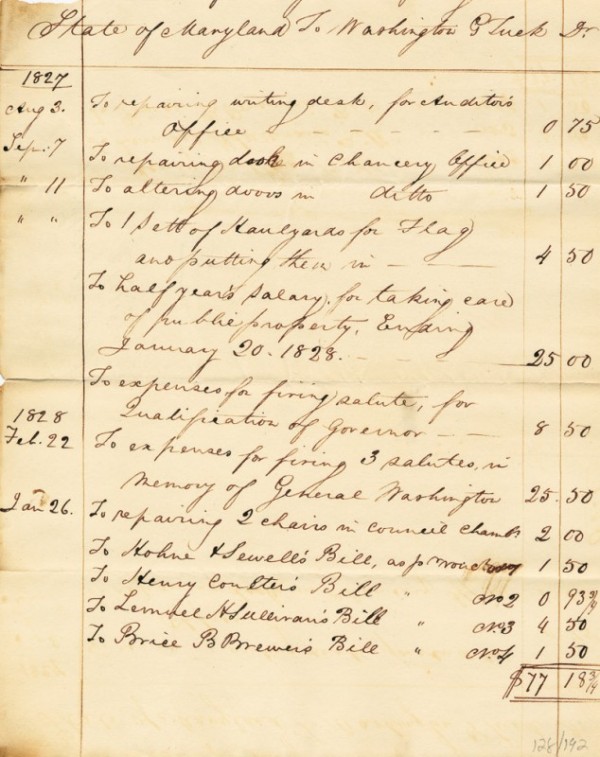

Invoice submitted by Washington G. Tuck to the state of Maryland, 1828. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Maryland State Papers.) Washington Tuck submitted this invoice for a range of services he performed between August 3, 1827, and February 22, 1828. While Tuck commonly repaired furniture in the State House (he received three separate payments for repairing “writing desks,” desks, and chairs during this six-month period), he also completed maintenance projects such as “altering doors” and replacing the halyards for the flag on the dome. The inclusion of payments for “taking care of the public property” and for firing celebratory salutes—a requirement of the state armorer—is common in these invoices, as are the payments to Tuck on behalf of four contractors.

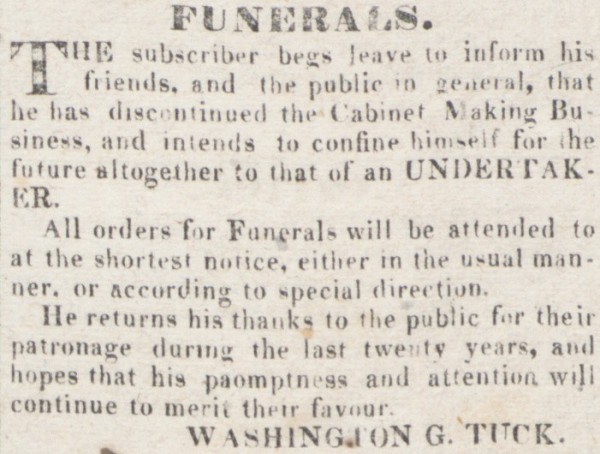

Advertisement by Washington G. Tuck in the Maryland Gazette, June 12, 1834. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives.)

E. E. Zerlantz, Annapolis, Capitol of the State of Maryland, 1838. Photograph of an engraving. 6 5/8" x 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, George Forbes Collection.) This engraving shows the State House (center) as it appeared when Washington Tuck retired from public service. Romantic views of Annapolis were common throughout this period, although it is clear that little of the city’s landscape had changed since the end of the Revolution.

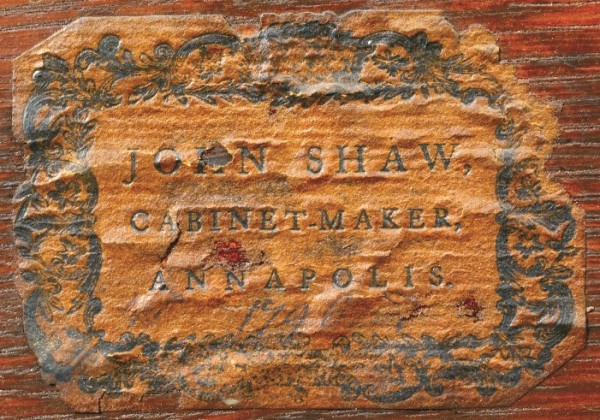

Studies of eastern Maryland furniture have traditionally focused on either eighteenth-century Annapolis or nineteenth-century Baltimore. As the colonial capital and older of the two cities, Annapolis enjoyed a golden age in the years before the Revolutionary War. During the 1760s and 1770s merchants, professionals, and political leaders including James Brice, Edward Lloyd IV, and William Paca built imposing houses (fig. 1), commissioned expensive furnishings, and had their portraits painted by such notable artists as Charles Willson Peale. Although Annapolis continued to serve as the capital after the Revolution, Baltimore quickly became the state’s economic and social center. With its deep-water port, Baltimore was ideally suited for receiving, marketing, and exporting grain from Maryland’s vast hinterland as well as from southern Pennsylvania. The city’s population and the wealth of many of its inhabitants grew geometrically and attracted numerous artisans trained both locally and abroad. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Baltimore supported more than thirty cabinetmakers, twelve chair makers, and a variety of specialists serving the furniture-making trades. Because of the diversity of that city’s craft community and its surviving products, scholars and students of Maryland furniture have devoted little attention to post-Revolutionary Annapolis work. The sole exception is John Shaw (1745–1829), the city’s most celebrated cabinetmaker, whose shop produced a significant body of stylistically distinctive work, much of it identified by labels (fig. 2). His life and work have been the subject of articles, museum catalogues, and a 1983 monograph titled John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis.[1]

The quantity and variety of objects documented to Shaw’s shop have allowed scholars to draw basic conclusions about the forms and aesthetic preferences of Annapolis patrons during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Conversely, furniture historians have identified only a small number of early-nineteenth-century objects with Annapolis provenances. Much of this later work has been relegated to footnotes or simplistically characterized as products of the “John Shaw School,” thus perpetuating the myth that he was the city’s only successful cabinetmaker. Similarly, little is known about late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Annapolis artisans in general or the challenges they faced as wealth, private patronage, and economic power shifted from that city to Baltimore. This essay will begin redressing that problem by examining the careers, furniture, and historical contexts of brothers William and Washington Tuck and the influence of public patronage on the cabinetmaking community in early national Annapolis.[2]

Among the most important building projects undertaken in pre-Revolutionary Annapolis were various iterations of the Maryland State House. The third State House, erected on the site of its predecessors, was the largest and most elaborate government building in the city (figs. 3-6). It was built between 1772 and 1779 under the direction of Annapolis merchant Charles Wallace from plans drafted by local architect Joseph Horatio Anderson. Since opening for the start of the 1779 session of the general assembly, the State House has been the most significant political, social, and economic symbol of Annapolis. Most notably, the building served as the capitol of the United States for the meeting of the Continental Congress between November 27, 1783, and August 13, 1784. During this session, General George Washington resigned his commission as commander in chief of the Continental Army on December 23, 1783, and the Treaty of Paris was ratified on January 14, 1784. Construction of its wooden dome, the oldest and largest in America, began in 1788 under the direction of Annapolis architect Joseph Clark and was completed in 1795 under the supervision of John Shaw. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the State House was home to all three branches of Maryland’s government.[3]

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the vitality of the city’s economy and the success of its tradesmen and merchants were inextricably linked to the State House. Annapolis artisans found employment there during periods of construction and when maintenance or furnishings were required. Tavern keepers, boardinghouse owners, and local shopkeepers—together making up a quarter of the city’s population in the 1783 tax assessment—derived much of their income when the legislature was in annual session, during the semiannual meetings of the court of appeals and the General Court of the Western Shore, and from the steady influx of students to St. John’s College. Maryland State Archivist Edward C. Papenfuse noted that in 1786 nearly 20 percent of the heads of households in Annapolis had positions affiliated with the government—a figure that diminished little in the decades that followed. These findings suggest that the building itself provided opportunities for those who could parlay their talents to meet the needs of the public sphere. As was the case in most closely knit trade communities in early America, Annapolis tradesmen gained access to town projects through political connections and social and family relationships.[4]

William and Washington Tuck’s entrée was facilitated by the political and social connections of their father, William (ca. 1741–1797), an independent painter-glazier since 1762. During the Revolutionary War and early national period, William supplemented his income by working for the state government. During the 1780s and 1790s he probably spent considerable time developing relationships with important Annapolitans to help his children in their careers. William’s efforts to forge ties between his sons and John Shaw support this assumption. By the time the younger William began working as a journeyman, Shaw had worked in Annapolis for more than thirty years and developed a thriving trade based on broad regional patronage. The Tuck brothers used their master’s and their father’s connections to advance their careers, becoming two of the most respected and successful artisans in Annapolis.[5]

As part of a second generation of cabinetmakers trained in Shaw’s shop, the Tucks understood the intricacies of private and public patronage and recognized the importance of the State House as a potential source of income. Like their master, William (ca. 1774–1813) and Washington (1781–1859) relied on governmental work when private commissions waned during the economic decline following the Revolutionary War. For three decades, the brothers received regular commissions to provide services and furnishings for the Maryland State House and were the only individuals, besides Shaw, consistently entrusted with the care and upkeep of that building between 1807 and 1838. During their careers, the Tucks, primarily Washington, built more than twenty-five pieces of furniture for the State House and commissioned and oversaw the construction and delivery of more than one hundred additional objects. By extending the literature beyond John Shaw, the stories of William and Washington Tuck allow scholars to examine the centrality of the State House in supporting local craftsmen and reveal how two artisans pursued their trade and maintained their competency in early national Annapolis.[6]

The Golden Age of Annapolis

The Annapolis of William and Washington Tuck was significantly altered from the town that had been Maryland’s most important city until the start of the Revolutionary War. From 1763 until the declaration of war in 1776, Annapolis enjoyed a golden age, the city’s most significant period of sustained economic growth and building. An influx of money generated from bountiful harvests, thriving tobacco export markets, and a rising demand for high-quality consumer goods helped establish the power of the colony’s landed gentry in town. Annapolis became the primary port for Maryland’s national and international trade, and its population swelled by 27.7 percent between 1765 and 1775 as many wealthy landowners moved to the leading city in the colony.[7]

Scottish immigrants John Shaw and Archibald Chisholm (d. 1810) were among those who came to Annapolis in the early 1760s in search of employment as journeymen cabinetmakers. Although no apprenticeship documents for either man are known, it is likely that they trained in Scotland rather than in England. Case pieces bearing Shaw’s label show a closer affinity to comparable forms from Edinburgh and other Scottish cities than to those produced in London. Like most immigrant artisans, Shaw and Chisholm modified their stylistic and structural vocabulary to accommodate local design preferences. By 1772 the two Scots had banded together to form the largest shop in the city and established their reputations as leading cabinetmakers in Annapolis. Catering to middle-level and elite patrons, Shaw and Chisholm advertised more than any other contemporary Annapolis cabinetmaker, offered the widest range of services, and even collaborated with other local artisans on selected pieces. In addition to making and repairing furniture, Shaw and Chisholm trained apprentices, imported and sold British furnishings, and provided additional services to the public sphere, suggesting their roles as both artisans and entrepreneurs.[8]

The outbreak of the Revolutionary War significantly altered the economic and demographic landscape of Annapolis; more than a quarter of the capital’s wealthiest residents, including many British loyalists, fled or were forced to leave their lands. Tobacco prices soared when the British blockade of the Chesapeake Bay in 1777 and 1778 curtailed overseas trade. The blockade and the city’s mobilization for an anticipated British invasion brought activity in the port to a standstill and forced residents to focus on sustaining the colony’s war effort. For the first time in more than two decades, merchants and mechanics in Annapolis saw sales to the private sector decline.[9]

Even as the citizens of Annapolis managed the wartime demands for stores and equipment, the center of Maryland’s trade market shifted to Baltimore (fig. 7). With deeper and more accessible ports and access to a vast hinterland, Baltimore became the fastest-growing city in America during the war. By the end of the conflict, Baltimore had captured the market for national and international trade once dominated by Annapolis merchants. In 1789 Annapolis storekeeper David Geddes reported: “I have no news to give you from this place, everything being at a stand. I in my store don’t receive more than from two to three dollars per day. Annapolis is diminishing fast . . . Citizens leaving it every day!” Faced with declining demands for their services, cabinetmakers and other artisans left Annapolis in search of opportunities elsewhere, a trend that signaled the end of the capital’s hold on the furniture-making trade. Even the most skilled craftsmen could no longer depend on private patronage alone to sustain their businesses.[10]

Patronage from state government played a critical role in the preservation of the artisan community that remained in Annapolis after the Revolutionary War. Artisans profited from the established custom for awarding contracts, which placed greater emphasis on political loyalty than the lowest bid. In contrast to modern state contracts, the governor’s council—the state’s executive body—and the general assembly did not always appropriate funds before the start of a project. Money for work at the State House sometimes came as a direct appropriation by the general assembly, but in other instances the council simply appropriated a sum it deemed appropriate. Then, guided by a long-standing tradition of patronage and social connections, the council selected its preferred contractor to undertake or superintend the work.[11]

Even though there were many more craftsmen in Baltimore than in Annapolis, accounting records and executive and legislative proceedings demonstrate that until the mid-1830s the council consistently awarded most State House commissions to artisans in Annapolis. This suggests that government officials were loyal to local craftsmen and may have recognized that the city’s artisan community would collapse without public patronage. Not surprisingly, cabinetmakers and other specialists worked diligently to establish connections to influential members of the government to gain access to work.[12]

To take advantage of the state’s patronage, craftsmen had to broaden their economic and financial outlets beyond the traditional scope of their trades. John Shaw provides one of the most visible examples of an artisan who expanded his range of skills to maximize employment opportunities. During the 1770s and early 1780s Shaw derived most of his income from private commissions and the sale of stock-in-trade. After the war, he compensated for the decline in that aspect of his business by securing public contracts, particularly those associated with the State House. Shaw served as the state armorer, a position he first received during the war, and by the 1790s he was caretaker of the State House, supervising or performing all of the necessary maintenance and renovations to the building, its furnishings, and grounds. During Shaw’s tenure, most of the furniture provided for the building came from his shop and was most likely built by the apprentices and journeymen cabinetmakers working for him.[13]

Documentary evidence and labeled furniture indicate that William Tuck worked in Shaw’s shop from 1795 to 1797 and that his younger brother, Washington, served his apprenticeship there from 1798 to 1801. Several factors may have influenced the Tuck family’s decision to ally with Shaw. The cabinetmaker was undoubtedly acquainted with the elder William Tuck and may have been kin. Perhaps more important, Shaw owned the largest cabinet shop in town when William began his career as a journeyman and Washington came of age. Shaw purchased property across the street from the State House in 1784, and his shop was situated on the same lot (fig. 8). Located between Church (now Main) Street, the hub of the city’s mechanic community, and the State House, Shaw’s shop was ideally situated for the pursuit of private and public commissions.[14]

The Tuck brothers joined Shaw’s shop during its busiest and most productive period—1790–1804. During this fourteen-year span, the workforce reached its peak and included journeymen. It is unclear whether William Tuck learned his trade from Shaw or from another Annapolis furniture maker, such as the latter’s former partner Archibald Chisholm, who retired in 1794.

William’s and Washington’s presence in Shaw’s shop is confirmed by six labeled pieces of furniture made between 1795 and 1797. William inscribed his initials and a date on five Shaw labels, and Washington signed the label of a desk made circa 1797 for the senate chamber in the State House. Although Shaw employed what is presumed to be a large body of workmen in his shop, the Tucks’ initials represent two of eight sets of initials found on labeled Shaw pieces.[15]

Because most of the furniture with initialed labels is typical of Shaw’s standard repertoire, it is likely that journeymen and apprentices were involved in the production of these objects. Like other artisans in the shop, the Tucks undoubtedly worked from designs and patterns created by their master. Since objects from Shaw’s shop were made in a regulated environment, it is difficult to attribute specific structural features and decorative elements to a particular hand. Some surviving objects, however, are superior in design and construction to other Shaw furniture, suggesting that they were commissioned by an important patron and may have required the attention of the most skilled journeymen if not the master himself.[16]

The Tucks and other select journeymen inscribed their initials on the shop labels to attest to their prominent roles in the construction of these pieces, even though they were sold as products of Shaw’s shop. This privileged group must have been highly skilled and trusted, because it is unlikely that Shaw would have let a worker initial a label unless the workmanship reflected positively on the owner of the shop. The prominent placement of Shaw’s labels made it too risky for a worker surreptitiously to initial a piece as a way of showcasing his role in its construction. Even though they primarily worked on stock items, the journeymen who signed these labels exercised some autonomy and pride in their work, and probably used this opportunity to lay a foundation for future commissions and business associations they could pursue after leaving the shop.[17]

Furniture documented to the Tucks resembles undocumented work likely produced by them during their tenure in Shaw’s shop. Collectively, these objects indicate that the brothers were familiar with a broad range of designs and construction methods codified in their master’s shop as well as generic neoclassical motifs seen in late-eighteenth-century Maryland furniture. The scarcity of pieces that can be definitively attributed to Annapolis after 1804 makes it difficult to assess the Tucks’ legacy, but evidence suggests that their training left them well equipped to respond to the exigencies of the working environment in Annapolis during the early national period.[18]

Furniture by the Tuck Brothers

Identification of furniture made by the Tucks is complicated by several factors. First, most of the objects documented to William Tuck were made when he was a journeyman in Shaw’s shop, and it is likely that both William and his brother continued producing furniture similar to their master’s after establishing themselves as independent artisans. Second, no daybooks, account books, ledgers, or other documents survive to identify specific work by the Tucks or other journeymen and apprentices in Shaw’s shop. Finally, given Shaw’s prominence, it is likely that many of his competitors emulated his work. In the absence of strong circumstantial evidence, attributions to Shaw, the Tucks, or other artisans who worked in the former’s shop can be problematic.

Documents related to the State House provide general information about the types of furnishings the Tucks made for the council and the legislature as well as the materials used, but few of these records are descriptive and many simply indicate payment for services rendered. The paucity of surviving State House furniture further complicates attributions. Only one of the more than twenty-five objects built by the brothers for the State House has survived, probably because this furniture was in continuous use over a long time. In addition, some of these objects were given as partial payment to contractors, sold at public auction, or simply discarded. Furniture made by the Tucks for the house of delegates in 1807, for example, was not completely replaced until 1858, at which point the stylistically outdated and damaged pieces (with the exception of the speaker’s desk) were probably donated to the clerk of the school commissioners for Anne Arundel County, Maryland, transferred to the court of appeals chamber, sold as scrap, or even discarded.[19]

One of the earliest objects documented to William Tuck is a mahogany cellaret he made in Shaw’s shop in 1795 (figs. 9, 10). Shaw’s label is glued to the center of the underside of the lid and inscribed “W 1795 T”. At least five similar cellarets from this period have survived (fig. 11), suggesting the use of established proportional systems and patterns. All of these examples have an inlaid false front and a hinged lid that opens to reveal a removable caddy and an undivided section for drinking glasses (fig. 10). In The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1794), George Hepplewhite noted that “CELLERETS, CALLED also gardes de vin, are generally made of mahogany . . . the inner part is divided with partitions . . . may be made of any shape.”[20]

A clothespress inscribed by William Tuck (figs. 12-14) is one of at least three closely related examples made in Shaw’s shop between 1795 and 1797 (figs. 15, 18). Like the aforementioned cellarets documented and attributed to Shaw’s shop, these presses were standardized forms, ideal for the deployment of journeyman labor. The clothespress illustrated in figure 15 is virtually identical to the example inscribed by Tuck, but its label bears the date 1795 and the initials of another journeyman (fig. 16), possibly John Walter Battee (b. 1775). Like the Tuck example, the presses shown in figures 15 and 18 have straight bracket feet with stack-laminated glue blocks (figs. 14, 17, 19). Further examination may reveal that some elements of these presses are interchangeable, much like certain components of desk-and-bookcases designed in Shaw’s shop during this period. For both forms Shaw offered options including flat and scrolled pediments and various inlays (figs. 18, 20).[21]

In contrast, a demilune card table with a label inscribed “W 1796 T” is the only circular example from Shaw’s shop (figs. 21-23). Most of Shaw’s surviving card tables are rectangular, and all are more restrained in the use of neoclassical inlay. While Tuck’s table is something of a stylistic anomaly, it has several features found on other examples from Shaw’s shop: bulbous spade feet; a broadcloth playing surface; a central alignment tenon on the folding leaf and a corresponding mortise on the stationary leaf below; and no medial brace. Similarities between the design of the demilune card table and contemporary Baltimore forms may indicate that Tuck made the former object to replace or accompany an existing Baltimore table owned by one of his master’s patrons. Shaw must have been familiar with prevailing Baltimore styles since he routinely purchased inlays from specialists in that city, as did many of his contemporaries working in eastern Pennsylvania and Maryland, the Shenandoah Valley, and as far west as Kentucky and Tennessee. That was clearly the case with the demilune card table’s sawtooth edging and eagle inlays, which have precise parallels in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Baltimore furniture.[22]

The construction of the demilune table suggests that William Tuck and his fellow workmen were unaccustomed to making that form. The rear legs have exposed pins and through-tenons—details not visible on rectangular card tables from Shaw’s shop—and the fly rail hinge and dovetails are less precise than normal (fig. 24). Visible joinery is also atypical of urban neoclassical work in general, making it unlikely that Tuck copied these aberrant structural features from a Baltimore card table.

Unlike demilune tables, desks and secretaries were standard repertoire for Shaw’s workforce. Most of the surviving examples represent private commissions, but his shop also produced similar forms described as “bookcase and desk,” “desk & bookcase,” or simply “cases” for rooms in the State House, including the chambers of the legislature, council, court of appeals, and other offices. Invoices submitted by Shaw to the state of Maryland for work completed during 1816 and 1817 listed two bookcases for the council chamber, including one “with 4 doors pidgeon holes & Shelves” for which he charged thirty-five dollars. Shaw also supplied two presses for the State House during that period. The most expensive example, made for the court of appeals and priced at forty-five dollars, had six doors and “pidgeon holes & shelves with locks & hinges &c.”[23]

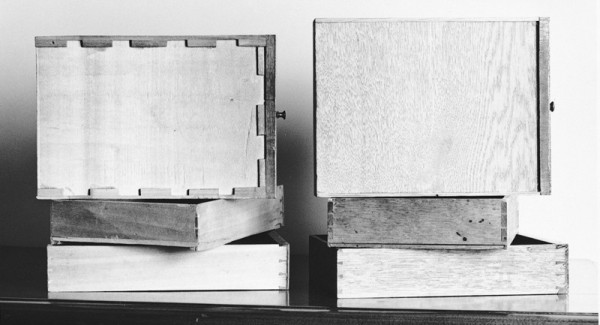

“Desk and bookcases, bureaus, wardrobes, [and] secretaries” were among the “ready-made . . . articles of household furniture” listed in Shaw’s advertisement in the October 10, 1803, issue of the Maryland Gazette. Some surviving examples are in the neat and plain style, whereas others have scrolled pediments with elaborate fret-sawn tympana, pictorial inlays, and other decorative features (see figs. 27, 28). Much of the case furniture documented and attributed to Shaw’s shop has stylistic antecedents in Scottish work and resembles, in a general way, objects produced by contemporary Caledonian cabinetmakers working in the colonies and new republic. Although we may never know whether Shaw immigrated with patterns and shop drawings in hand, he clearly used them from the outset of his American career. William Voss Elder and Lu Bartlett, for example, noted that the drawers from a desk-and-bookcase of circa 1780 are interchangeable with those in later examples from Shaw’s shop. Patterns regulated production and allowed multiple artisans to produce components for the same object. A bureau with secretary drawer bearing Shaw’s label and the ink inscription “J 1796 B” (figs. 25, 26) has interior drawers constructed by two different artisans, yet the design of its writing compartment differs little from those on other desks and secretaries from his shop, including those documented and attributed to William Tuck (figs. 27-30).[24]

Although standardization increased the speed and efficiency of Shaw’s workforce, it did not mean that his journeymen were locked into a single mode of production. The shop clearly offered a variety of options for every form. Desks and double-case writing forms were available with straight bracket, ogee bracket (fig. 27), splayed bracket (figs. 29, 30) or French feet; plain or scrolled pediments; fret-sawn or sawn and carved tympana (fig. 31); cornice molding with Gothic arches and acorn drops; and a variety of inlays including shells for fallboards (fig. 32) and friezes, eagles for prospect doors (fig. 33), paterae for cornices, quarter-fans for doors, and stringing for drawer fronts.

A labeled desk-and-bookcase (figs. 29, 34) and secretary-and-bookcase (fig. 30) attributed to William Tuck suggest that he was capable of responding to the most demanding commissions. Family tradition maintained that the original owner of the desk-and-bookcase was Annapolis lumber merchant John Randall, a prominent member of the community who sold wood to Shaw and owned other examples of the cabinetmaker’s work. Like the clothespress illustrated in figures 12 and 13, the desk-and-bookcase and secretary-and-bookcase have drawers with finely cut dovetails, upper cases with four-panel backs, and stack-laminated glue blocks supporting the feet (figs. 35, 36). The fallboard of the desk-and-bookcase also has a central alignment tenon like the upper leaf of the card table associated with Tuck (fig. 24). This feature also occurs on other desks associated with Shaw’s shop. Despite having different design features, the desk-and-bookcase and the secretary-and-bookcase may have been made only a few months, or even weeks, apart. Both objects have swelled bracket feet (fig. 37) like those on contemporary urban case furniture from England and Scotland.

Comparison of the labeled desk-and-bookcase and secretary-and-bookcase attributed to William Tuck (figs. 29, 30) with the two related examples illustrates the problem of separating the work of Shaw’s journeymen without inscribed labels or other documentation. The labeled desk-and-bookcase and secretary-and-bookcase both have stack-laminated foot blocks whereas the pieces illustrated in figures 27 and 28 have single-piece vertical glue blocks. However, as the labeled press shown in figures 15–17 indicates, other Shaw journeymen also used stack-laminated blocks. The upper cases of the secretary-and-bookcase and labeled desk-and-bookcase also have four-panel backs with pinking on the inside surface. The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 27 shares that feature, but the example shown in figure 29 has a two-panel back. There are even variations in the furniture associated with Tuck. The lower case of the secretary-and-bookcase has horizontal backboards nailed into rabbets at the top and sides, whereas all of the desk-and-bookcases illustrated here have vertical backboards attached in a similar manner (figs. 27–29). It is unlikely that any of the major case pieces produced in Shaw’s shop during the mid- to late 1790s represent the work of a single craftsman.

William Tuck was still employed by Shaw when the latter received his most important commission for furniture for the State House. In 1797 the general assembly appointed Shaw to supply “24 Mahogany arm chairs [fig. 2], 10 Mahogany desks for the use of the Senate, and 1 neat Mahogany do for the president,” for which the cabinetmaker received £217.18.6 (fig. 38). The desks illustrate the local preference for furniture built in the neat and plain style, as the pieces are well constructed but without elaborate ornamentation. The president’s desk, which is labeled and inscribed “W 1797 T,” is larger and more ornate than the ten identical examples made for the senators (figs. 39-41). Tuck’s initials confirm the involvement of Shaw’s journeymen in the production of furniture for both the private and public markets.[25]

William Tuck probably left Shaw’s employ in 1797, soon after completion of the senate commission, and by 1799 had formed a partnership with Annapolis cabinetmaker James Lusby. William became an independent shop owner in October 1801 after he and Lusby dissolved their partnership “by mutual consent,” and Tuck advertised his “cabinet business” in the Maryland Gazette. William built and repaired furniture for local residents and was one of the few Annapolis cabinetmakers other than Shaw and Chisholm to receive the patronage of Edward Lloyd V of Wye House. Tuck provided significant amounts of furniture for the Lloyds between 1803 and 1809, a series of commissions undoubtedly related to his association with Shaw, the favored Annapolis cabinetmaker of the Lloyd family at the start of the nineteenth century.[26]

Less than a year after his brother left Shaw’s shop, Washington Tuck began a three-year apprenticeship with the master cabinetmaker on August 16, 1798. Like his older brother, Washington was involved in public and private commissions, including the production of stock-in-trade and furnishings for the State House. The only documented work associated with the younger Tuck’s apprenticeship is a senate desk of circa 1797 that he signed and dated “Wash Tuck 1801” when the piece was in Shaw’s shop for repairs (figs. 42, 43). In urban shops, the repair of damaged furniture was often assigned to apprentices.[27]

Like several of his fellow apprentices, Tuck moved to Baltimore after completing his term with Shaw. By the time he arrived in 1802, Baltimore was the fastest-growing city in the country; its population doubled between 1790 and 1800, and nearly doubled again in the following decade. Washington may have begun his Baltimore career as a journeyman in the shop of cabinetmaker Edward Priestley, whom furniture historian Alexandra A. Kirtley has described as having a business relationship with Shaw by virtue of the two artisans’ connections to the Lloyd family. Her research suggests that Edward Lloyd V may have encouraged Shaw to send his former apprentices to work with Priestley. Such an arrangement would have helped alleviate competition in Annapolis and given Shaw’s apprentices the opportunity to hone their skills making furniture in the latest styles and to learn more about management and marketing by observing Priestley’s interaction with his workforce and his patrons. Washington would also have been exposed to the work of other cabinetmakers, since more than fifty shop masters were active in the city by 1800. Evidence suggests that Tuck was acquainted with several important tradesmen including cabinetmaker William Camp and city dock owner Hugh McElderry. Camp employed former Priestley workman John Needles, and all three cabinetmakers had patrons at the highest levels of society.[28]

When Washington Tuck returned to Annapolis in the fall of 1806, he found an economic environment disturbingly similar to the one he left behind four years earlier. The only consistent source of work remained that connected to the State House and state government. Middle-level artisans like the Tucks had to take advantage of all available outlets for work, even those that stood outside the traditional boundaries of their trades. With their connections to other tradesmen and to such important politicians as Lloyd, William and Washington were ideally positioned to solicit and receive public commissions. Their situation improved even further when Shaw retired as superintendent of the State House in 1807.[29]

The House of Delegates Chamber, 1807

In 1807 the Maryland General Assembly decided to refurnish the house of delegates chamber (fig. 44) and replace the delegates’ furniture—possibly the furnishings supplied for the opening of the new chamber in 1779. On January 3 the Maryland House of Delegates passed a bill ordering the governor and council to “furnish the house of delegates with twenty-one convenient writing desks, with four separate drawers each, for use of the delegation from each county, and the delegation from the city of Annapolis and Baltimore.” Two months later, the council issued a resolution regarding work in the house chamber:

Ordered that William Tuck be employed to do the workmanship, in carrying the designs of the legislature into effect, as related to the fitting up and repairing the house of delegates room: That the room be laid off in circular form, and that the desks be raised one above the other as nearly like the room occupied by congress as may be practicable: That the said house of delegates room be furnished with a new carpet and completed by the time of the meeting of the legislature: That James Lusby and Robert Davis be employed to fit up the senate chamber, by repairing the desks and chairs now out of repair, and make as many new ones as may be necessary to complete the number of fifteen, and that the said senate chamber be provided with a new carpet.[30]

Passage of this resolution coincided with Shaw’s two-year hiatus from state work, and the governor and council had to select other artisans to complete the renovations. The council’s decision to choose two Annapolis cabinetmaking firms to complete the renovations in the State House—even though it would have been cheaper to use Baltimore makers—probably reflected loyalty to local craftsmen rather than concern over quality control. The council did not solicit proposals, although they may have consulted with Shaw in light of his former role as superintendent and his familiarity with local workers.

The Tucks formed an official partnership soon after William received the State House commission, although the elder Tuck later explained that he and his brother had “contracted their partnership back to about . . . [January 1, 1807], in consequence of other work done by them.” Before beginning the State House renovations, William, possibly accompanied by Washington, traveled to the District of Columbia to “take a plan of the finishing of the house of representatives” in the Capitol. William returned to Annapolis to replicate Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s design on a smaller scale, a significant challenge because of the discrepancy in size and shape between the Maryland House of Delegates chamber and the U.S. Capitol’s House of Representatives’ chamber (figs. 44, 45). The brothers also faced the stipulation that all renovations be finished by the start of the legislative session on November 3, 1807. This was a daunting task that entailed providing new furnishings for eighty delegates and two clerks, plastering and painting the room, and supplying a new carpet and window blinds.[31]

The brothers’ final bill detailed the furniture they supplied for completion of the house of delegates chamber and demonstrated the range of their cabinetmaking and entrepreneurial skills. As part of their work for the house of delegates, the Tucks made twenty-four pieces of furniture: nine circular (bow-front) desks valued at ninety dollars each; twelve straight desks valued at fifty-five dollars each; one speaker’s desk valued at fifty dollars; and two clerks’ desks valued at thirty-five dollars each. Designed to the specifications outlined by the general assembly, the delegate desks had four drawers, one for the use of each county delegation. In the absence of surviving examples, it is impossible to determine the dimensions of these desks; however, the circular ones were probably made in three different sizes because of the tiered configuration of the delegates chamber. The Tucks also repaired some of the existing furniture in that room. They charged fifteen dollars for repairing the clerk’s chair, seven dollars for stuffing, repairing, and cleaning the speaker’s chair made by Shaw’s shop in 1797, and one dollar for work on the stool that accompanied the speaker’s chair.[32]

Additional receipts submitted in conjunction with the State House commission suggest that the Tucks traveled to Baltimore to subcontract the chair making and to procure inkstands and sandboxes. The brothers billed the state of Maryland $160 for “80 chairs at 24 dollars per dozen,” $11.12 for “freight on ditto,” and $24.50 for “expenses on [the] chairs.” The low cost of the chairs (two dollars each) suggests that they were Windsors, seating furniture made in large quantities in Baltimore and used in the galleries in the house and senate chambers.[33]

The only known object surviving from the Tucks’ house of delegates commission is the speaker’s desk (figs. 46-49). Although formerly attributed to Shaw on the basis of its construction and style—especially the relation of its inlaid eagle to the one on the desk Shaw’s shop made in 1797 for the president of the senate (fig. 39)—the speaker’s desk is undoubtedly a product of William and Washington’s shop. It is specified on their bill, and Shaw was no longer superintendent of the State House when the Tucks began providing furnishings for the delegates chamber. The fact that the speaker’s desk resembles the senate president’s desk should come as no surprise, given the fact that William worked in Shaw’s shop and Washington trained there.[34]

The speaker’s desk also has features that depart from Shaw’s work. With their lunetted corners and contrasting stringing and banding, the tablets inlaid on the upper leg stiles have parallels in contemporary Baltimore furniture. The Tucks also used satinwood banding on the lower edge of the rails (fig. 48) instead of the applied cock-bead associated with their former master and other local artisans. Likewise, the wooden knobs on the speaker’s desk are a detail rarely, if ever, seen in Annapolis furniture (fig. 49). While there was a clear hierarchy in the furnishings of the house of delegates chamber, with the speaker’s desk situated on the raised dais at the front of the chamber, all of the remaining examples furnished by the Tucks had similar knobs and banding. This was essential not only for a unified furnishing scheme but also to signify equality among the delegates. Regrettably, most of these features are too generic to assist in the identification of other work by the Tucks.[35]

In its final design, the house of delegates chamber was a modification of the House of Representatives chamber in the United States Capitol. The Tucks replicated the furnishing scheme of Congress Hall and the House of Representatives chamber, where groups of straight desks were placed to the immediate right and left of the speaker’s dais and curved desks faced the front of the chamber (fig. 50). For the purposes of their bill, the brothers considered one desk to be “the space allowed for four members to sit at”; thus twenty-one desks accommodated the eighty members of the lower house. The lids were covered in broadcloth, and all of the desks were “separated by small pieces of mahogany between the cloth [and] screwed together” to create individual work spaces for each of the delegates.[36]

The general assembly’s decision to model the house of delegates after the house chamber in Washington was both significant and symbolic. Maryland legislators understood that national unity required a symbiotic relationship between state and federal governments and they sought to express that connection in material form. Henry-Russell Hitchcock and William Seale have argued that regional preferences influenced the design and furnishing of state capitols built before 1824, and that efforts to express nationalism architecturally were minimal. Although built more than two decades before the completion of the U.S. Capitol, the Maryland State House may have been the first to emulate the Capitol in the decoration and aesthetic appearance of one of its rooms. The Tucks incorporated the general assembly’s vision into a design that stressed the idea of unity at national, state, and local levels.[37]

Cabinetmaking in Early National Annapolis

The Tucks finished the renovations in the house of delegates chamber in early December 1807, but the governor and council considered their final bill of $2,988.86 (which did not include a $300.00 advance paid to William in May 1807) too high and refused to remit payment. This billing dispute was undoubtedly fueled by the fact that William did not submit an estimate nor did the council appropriate a sum of money for the work. William later recalled not “having produced to the Council any bills or vouchers for particular charges . . . nor was it required of him.” For many months, it appeared that the council would renege on its promise to go to arbitration if a billing dispute arose. Three months after submitting his bill, William composed a scathing letter to the council, writing, “I am not asking a favour, but asking for my own money; money that you unjustly detain; money that I boldly say, I have honestly and fairly laboured for, money that . . . I am entitled to.”[38]

William and Washington found themselves embroiled in a major political controversy in the eight months between the completion of the work and their receipt of payment. The Tucks received final payment on August 17, 1808, and William proclaimed, “that in his life he was never more surprised . . . for from the previous conduct of the executive it was what he least expected . . . [for] he thought it impossible that they could now pass his account with propriety for the full amount.” A contemporary newspaper account of this saga chronicled the sudden culmination of the billing dispute and noted that “Without a word . . . or any new information to alter their opinion, the council sent an order to the Tucks for the full amount of their claim to the great surprise of William Tuck.”[39]

Despite the anticlimactic resolution of the dispute, the political ramifications warranted the appointment of a house of delegates committee on November 8, 1808—the first day of that year’s legislative session—to

inquire into the expenses in the execution by the governor and council of a resolve . . . authorising them to furnish the house of delegates with twenty-one desks; and that the said committee report to this house the different sums of money advanced under the direction of the executive . . . and to whom, and at what time, and under what circumstances, the same were paid; and that said committee have the power to send for persons, papers, and records.

The committee’s final report, published in the journal of the proceedings of the November 1808 session of the house of delegates as well as in several Maryland newspapers, revealed important information regarding the Tucks’ role within the social and political spheres of Annapolis, as well as the uncertainty of cabinetmaking in the state capital. Witness testimony recorded in the report chronicled the heated political rhetoric between the brothers and members of the council and revealed that, in the end, the brothers secured payment primarily because of their political influence and repeated threats to upset the existing political balance in the house of delegates and the council.[40]

While the Tucks used their position to challenge older political hierarchies, the council sought to preserve its power as the state’s executive body, a branch that refused to be bound by an arbitrator’s ruling. Both brothers considered themselves “ill-treated” by the council, and Washington added that refusal to pay would “injure the republican cause.” The brothers sought the election of a new candidate—not the council’s choice—for the Annapolis seat in the lower house in the upcoming election. A staunch Republican, Washington declared that he would “oppose the council, or the party . . . [and] the impression made by [him] . . . was that in elections for delegates (in which the members of the council, residents in [Annapolis] generally take a very decided and active part) [the members of the council] should never have his vote or influence.” Washington reportedly told many influential Annapolitans that he would “oppose the council in their election unless his account was paid.”[41]

William and Washington’s involvement in city and state politics was significant in Annapolis, a town where members of the governor’s council influenced legislators and even local elections. The Tucks’ conflict with the council took on added significance in an election year, because they “were men likely to be active and of some influence in the city election, where every vote is a matter of consequence.” The eight-month billing dispute was risky for the brothers because they purchased materials from several members of the council as well as the city government, and it did not behoove them to alienate their suppliers or their clientele. An adverse result could have tarnished their standing among council members and removed them from consideration for future government commissions.[42]

The 1808 hearings not only reflected the charged political atmosphere in Annapolis but also illuminated the challenges that faced cabinetmakers working in the city. By the time the Tucks received their commission, Annapolis had ceased to be an important port, and most building and woodworking materials arrived in Baltimore. With no trade associations or guilds to help reduce costs through collective purchases and bargaining, Annapolis cabinetmakers were unable to secure materials as advantageously as their Baltimore counterparts. In his testimony to the house committee, Annapolis merchant and delegate John Muir recalled a statement by Washington Tuck:

Certain cabinet-makers in Baltimore had associated for the purpose of purchasing quantities of mahogany as they arrived; that they, of course, secured for themselves the prime of the wood, and disposed of the inferior to other cabinet-makers in Baltimore, or distant workmen, at such advanced prices as often left their own stock at less than nothing in point of cash.

Washington’s connections with Baltimore cabinetmakers and his past experiences as a journeyman in that city gave credence to Muir’s report, although Annapolis craftsmen had little recourse against such practices.[43]

Artisans in Annapolis could not afford to sell their furniture at prices competitive with those of Baltimore makers because their cost of materials was greater and demand was substantially less. In defense of his bill for the house renovations, William Tuck stated that prices for the “sort of work done in the house of delegates room are always about 20 per cent higher in Annapolis than in Baltimore,” and his brother added that “advance charges on the Baltimore prices for cabinetwork in Annapolis are generally from twenty to thirty percent.” William also noted that the “prices charged the . . . [state government] are the same that he would have charged individuals for . . . [identical] work.”[44]

Whereas Baltimore artisans formed trade organizations that ensured them a political voice and access to work, their Annapolis counterparts had to navigate through an older and increasingly unreliable system dependent on personal connections. Public commissions, primarily those related to the State House, provided the steadiest source of income for all mechanics, but such contracts were by no means lucrative. The building and woodworking skills of Shaw and the Tuck brothers made them ideal candidates for State House commissions because they could perform a range of tasks, including painting, repairing furniture and walls, and plastering, and all three men had social and political connections that facilitated their patronage. Despite struggling to receive payment, the Tucks’ successful completion of the State House renovations solidified their reputations as two of the most important and influential cabinetmakers in Annapolis.

After the Tucks dissolved their partnership in 1810, William opened a boardinghouse at the foot of State House Hill to cater to students, travelers, and public servants attending sessions of the court of appeals and annual meetings of the general assembly. At the time of his death in 1813, his household furnishings included two dozen Windsor chairs, one walnut and one mahogany “bureau and Book case,” a “stained beaufat,” a walnut sideboard, and a “mahogany bottle case.” The adjacent listing of “lot of lumber broken furniture &c.,” a “tea square,” an oval walnut table, eleven low post beds, seven field beds, and a “walnut work table” suggests that William may have continued making and repairing furniture. As was the case with most artisans, he probably made furniture for his own use.[45]

Washington Tuck found employment as state armorer in 1810, a position that he shared with Shaw until the latter’s retirement in 1819. Washington’s primary duties included cleaning and varnishing scabbards, supplying weapons and ammunition to the state armory and military units, and organizing the armory and gun house. Tuck’s government job provided him with a dependable quarterly or semiannual salary—a luxury not afforded to most artisans in the private market—which allowed him to pursue other opportunities, such as supplementing his income by repairing furniture for local residents. He also purchased property (fig. 51) next to Shaw’s house and shop, thereby aligning himself with the man charged with maintenance of the State House. Washington opened his own shop in 1814 and succeeded Shaw as superintendent in 1820.[46]

To Superintend the Necessary Repairs

Washington Tuck served as superintendent of the State House (fig. 52) from 1820 to 1829 and regularly received orders from the council and legislature for work at the capitol between 1830 and 1838. In that capacity, he made recommendations for structural and aesthetic repairs, performed and supervised maintenance and refurnishing projects, and supplied furniture as needed. His role as caretaker of the city’s most prominent symbol of democracy and prosperity boosted Washington’s status at a time when residual effects from the panic of 1819 caused the most successful artisans to struggle. Even after Tuck ceased being superintendent, he received more contracts for work at the State House than any other Annapolis artisan during this eighteen-year period.[47]

In addition to his salary for “taking care of the public property,” Tuck received lump sums of money for his commission and to compensate him for his time, supplies, and the wages he paid to others involved in renovation projects. Time and fiscal constraints were important considerations in all of Washington’s work, since certain projects, like the house of delegates renovations, had to be completed before the start of a legislative or judicial session. Tuck and his predecessor probably worked under budgetary restrictions that determined whether they made furnishings themselves or procured them from Baltimore artisans. Even when funds were not appropriated in advance, Tuck, like Shaw before him, had to make savvy financial decisions to remain accountable to his patrons in the legislature and the governor’s council.[48] In 1826 the governor and council ordered Washington to:

Super-intend the necessary repairs to stop and prevent a leak in the Roof of the State House, and the purchasing of such Desks, Tables, Chairs and other furniture as may be necessary for the Chamber now occupied by the Court of Appeals—provided that the whole amount of said expenditures shall not exceed four hundred dollars.

Tuck received $400 in June 1826, but six months later the council paid him an additional $90.72 for “making a Large double Desk for the Court of Appeals Room and putting partitions in ditto, repairing lock in old Armoury and for Lead putting down around fireplaces in the State House, and for two fire fenders.” Tuck may have procured the desks, tables, and chairs specified in the governor and council’s initial order in Baltimore; however, his final account revealed that those purchases were more costly than anticipated. Governor Joseph Kent reported that Tuck’s “expenditures exceeded the appropriation by the sum of $81.39, although he procured such articles of furniture only, as were deemed essential to the decent and comfortable fitting up of the chamber.” The council subsequently determined that Tuck did not incur any “improper or unnecessary expense” and recommended that the general assembly pay the balance.[49]

The period in which Tuck worked as the superintendent of the State House fell between major renovation campaigns at the public building, and new furnishings were often ordered to replace or complement existing objects. Tuck often made utilitarian objects to fit the needs of the various offices in the building. In February 1822 he received $325.66 “on account for a Book case for the Council Room, packing up and delivering Arms and so forth.” Tuck made a clock for the senate chamber in 1823, a case “to hold the books of records of chancery papers” for the chancery office in 1827, and a mahogany ruler for the chancery office in 1828. He also built several voting and record boxes for the general assembly, court of appeals, and register of wills, and made regular repairs to the desks and chairs in the house of delegates and court of appeals chambers. In 1829 Washington received five dollars for a case for the court of appeals, five dollars for a hat rack for the chancery court, and twenty-five dollars for boxes for the laws and proceedings.[50]

As was the case with John Shaw, Washington’s public work was diverse but usually more mundane than artistic (fig. 53). During his tenure as superintendent, Tuck repaired doors and windows, did painting and plastering, replaced locks and shelves, built a woodshed for the treasury building, set up the state library, and provided carpets for the chambers of the house of delegates and court of appeals. He also supervised landscaping projects including the replacement of stone steps on the west side of State House Circle and repairs made to the “shingling of the circle wall.”[51]

Washington received his last commission at the State House in 1837, when the governor and council appointed him and Richard W. Gill, clerk of the Court of Appeals of the Western Shore, to superintend “repairs, improvements and furniture in several parts of the State House . . . to carry into execution the purposes of the General Assembly.” The two men supervised the painting of the dome and the painting and furnishing of the chambers of the court of appeals, the chancery, and the house of delegates, and the house committee room. Although Tuck purchased most of the new furniture from Baltimore cabinetmakers, he oversaw the construction of the “desk of the tribunal” and the clerk’s desk for the court of appeals, both of which were designed by Baltimore architect Robert Cary Long and made by Annapolis cabinetmaker Elijah Wells. In his contract, Wells noted that the work was “to be done in the best most modern and improved style” and according “to the satisfaction of said Tuck,” alluding to Washington’s expertise as a cabinetmaker familiar with the needs of the building.[52]

Washington Tuck’s Private Commissions

The stagnant economic conditions in Annapolis meant that Washington Tuck was unable to make cabinetmaking his primary trade and may explain why no apprentices or journeymen are known to have worked for him. Tuck did, however, receive commissions from wealthy patrons. He performed a number of services for Edward Lloyd V between 1819 and 1826, a period when the Lloyd family purchased most of their furniture from Baltimore artisans. Tuck also maintained his contacts with Edward Priestley and appears in the deceased cabinetmaker’s list of debts in 1837.[53]

On June 12, 1834, Tuck placed his only advertisement in the Maryland Gazette (fig. 54), reporting that he had “discontinued the Cabinet Making Business” and intended “to confine himself for the future . . . to that of an UNDERTAKER.” Tuck thanked “the public for their patronage during the last twenty years” and expressed hope that “his promptness and attention” would “continue to merit their favour.” Like many of his contemporaries, Tuck understood that the social and political connections he developed as a cabinetmaker could be exploited in this trade. In August 1828 Tuck received $75.37 1/2 for arranging the funeral of Harriet Callahan Ridgely, whose husband, John, was a prominent doctor. Her “raized top coffin, lined and shrouded with cambrick, cords, tassels & pillows, covered with super fine Black cloth,” accounted for fifty dollars of Tuck’s fee.[54]

As the experiences of William and Washington Tuck suggest, artisans in early-nineteenth-century Annapolis had to be resourceful and flexible to adapt to their town’s economic and demographic decline as well as competition from Baltimore merchants and tradesmen. The greatest threat to economic stability came in 1817 and 1818, when the Maryland General Assembly considered relocating the capital to Baltimore. The legislature rejected the idea even though Baltimore’s city government had pledged to finance the construction of all necessary public buildings. According to nineteenth-century historian Elihu S. Riley, the “strongest point made against . . . [moving the capital] was the mob in Baltimore [during the War of] 1812.” Riley’s statement suggests that the legislature considered Annapolis the safer of the two cities, owing to its smaller population and geographic location. Not until the constitutional reforms of 1836–1838 did Baltimore artisans gain regular access to contracts for work at the State House and Government House—the residence of Maryland’s governors.[55]

To some early historians, Annapolis in the 1820s and 1830s appeared much as it had at the start of the century: quiet and undisturbed by the changes happening elsewhere in the rapidly developing nation (fig. 55). A nineteenth-century writer contended that “[Annapolis] should be called the pivot city . . . for while all the world around it revolves it remains stationary. . . . To get to Annapolis you have but to cultivate a colossal calmness and the force of gravity will draw you . . . there.” In reality, this romantic description overstates the conditions in the Maryland capital. To the outside observer, Annapolis became a provincial outpost with little economic activity after the Revolution; however, the city’s role as a political center ensured employment for artisans who could adapt to the demands of the public sphere. William and Washington Tuck’s decision to design furniture for the State House and to shift their business from providing furniture for private patrons to fulfilling government contracts for a variety of work was a necessary response to the challenges facing Annapolis artisans, especially cabinetmakers, in the early national period. In an era marked by diminished employment opportunities, the Tuck brothers remained in their hometown and committed themselves to helping the city’s artisan community survive an era of economic decline.[56]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with the article, the author thanks Elaine Rice Bachmann, Luke Beckerdite, Mimi Calver, Stiles T. Colwill, Jeannine Disviscour, Alexandra A. Kirtley, Robert Leath, Dr. Christine Arnold-Lourie, Lisa Mason-Chaney, Melissa Naulin, Dr. Edward C. Papenfuse, Sumpter T. Priddy, Gerald W. R. Ward, and Gregory R. Weidman.

William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983). For more on artisans and merchants active during the age of affluence in Annapolis, see Edward C. Papenfuse, In Pursuit of Profit: The Annapolis Merchants in the Era of the American Revolution, 1763–1805 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975); The Diary of William Faris: The Daily Life of an Annapolis Silversmith, edited by Mark B. Letzer and Jean B. Russo (Baltimore: The Press at the Maryland Historical Society, 2003); and Mark P. Leone, The Archaeology of Liberty in an American Capital: Excavations in Annapolis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

Most scholarly publications on Annapolis-made furniture focus on John Shaw and virtually exclude the work of his contemporaries (W. M. Horner Jr., “John Shaw of the Great Days of Annapolis,” International Studio 98, no. 406 [March 1931]: 44–47, 80; Louise E. Magruder, “John Shaw, Cabinetmaker of Annapolis,” Maryland Historical Magazine 42, no. 1 [March 1947]: 35–40; Rosamond Randall Beirne and Eleanor Pinkerton Stewart, “John Shaw Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 78, no. 6 [December 1960]: 554–58; and Lu Bartlett, “John Shaw, Cabinetmaker of Annapolis,” Antiques 61, no. 2 [February 1977]: 362–77; Elder and Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis).

Since 2000 the Maryland State Archives and Maryland Historical Trust have been engaged in a comprehensive examination of the history of the State House as part of the research relating to the compilation of a Historic Structure Report (hereafter cited as HSR) for the capitol. Documents uncovered during the initial research phases of the HSR provided the genesis for this study. On its completion, the HSR will become the definitive record of the Maryland State House, and all of the relevant materials will be made accessible online through http://mdstatehouse.net, an interactive website containing all of the documents and images pertaining to the building and grounds from 1769 to the present. The website is part of the Archives of Maryland Online publications series (Special Collections, Maryland State House History Project, msa sc 5287). Former Maryland State Archivist Morris L. Radoff published the only books dedicated to the history of the State House, but both were limited to the architectural history of the building (Morris L. Radoff, Buildings of the State of Maryland at Annapolis [Annapolis: Hall of Records Commission of the State of Maryland, 1954]; and Morris L. Radoff, The State House at Annapolis [Annapolis: Hall of Records Commission of the State of Maryland, 1972], p. 30).