George Munger, The Capitol in Ruins, 1814–1815. Watercolor on paper. 12" x 17". (Courtesy, Kiplinger Washington Collection.) The fire of August 24, 1814, greatly compromised the Capitol’s structural integrity. Congress could not reoccupy the building until the end of 1819.

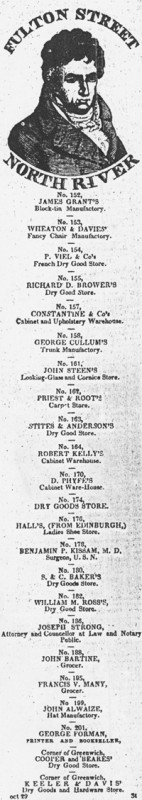

Advertisement, New-York Evening Post, October 30, 1817. Constantine was not the only cabinetmaker on his block. Duncan Phyfe and his former apprentice Robert Kelly also operated businesses on Fulton Street.

James Smillie after Charles Burton, St. Thomas’ Church, Broadway, New York, Park Theatre, and Part of Park Row, 1831. Etching. 3 5/8" x 2 3/4". (Courtesy, I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.) Constantine opened his Fulton Street wareroom a half block from Broadway and City Hall. St. Paul’s Church is visible at the intersection of Broadway, Fulton, and Park Row.

T. Constantine & Co., pier table, New York City, 1817–1820. Mahogany, mahogany veneer with white pine and tulip poplar; marble, mirrored glass, gilded gesso, verde antique, and brass. H. 35", W. 42", D. 19". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum.) This table is one of a pair owned by wealthy Bristol, Rhode Island, merchant James De Wolf.

Detail of the label on the pier table illustrated in fig. 4. This is the only paper label associated with T. Constantine & Co. and was probably printed in 1817, when Constantine first moved to Fulton Street.

David Davidson, Interior of the Mount, Bristol, Rhode Island, ca. 1880. Photograph. (Courtesy, Historic New England.) The pier table illustrated in fig. 4, or its mate, can be seen between the windows on the opposite wall. The table is also shown in A Bit from the de Wolf House, a ca. 1860 painting by Worthington Whittredge (1820–1910).

T. Constantine & Co., drop-leaf dining table, New York City, 1817–1820. Mahogany with white pine and maple. H. 28 1/2", W. 59 3/4", L. 118 1/4" (extended). (Private collection.) Though “Cumberland Action” dining tables are typically attributed to Thomas Seymour of Boston, this example bears Constantine’s label.

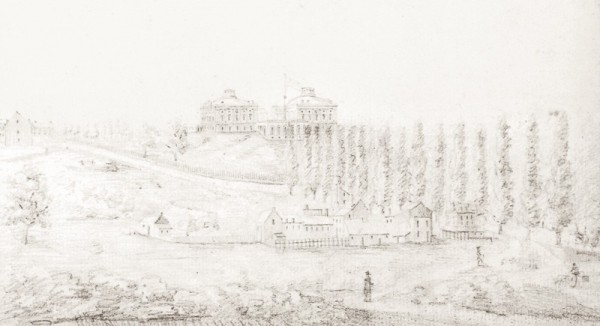

Michael Esperance de Hersant, View of the Capitol Looking Southeast, ca. 1819. Drawing on paper. (Private collection.) This is one of the few views of the Capitol during the period before the central rotunda was completed. When T. Constantine & Co.’s furniture arrived in Washington in 1819, the Capitol would have been in this state of continuing construction.

The Old Capitol Prison, 1st and A Streets, NE, Washington, D.C., 1862–1865. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) While the Capitol was reconstructed between 1814 and 1819, Congress met in this former tavern (nicknamed the Brick Capitol), for which Latrobe designed an addition that included assembly rooms for the House and Senate.

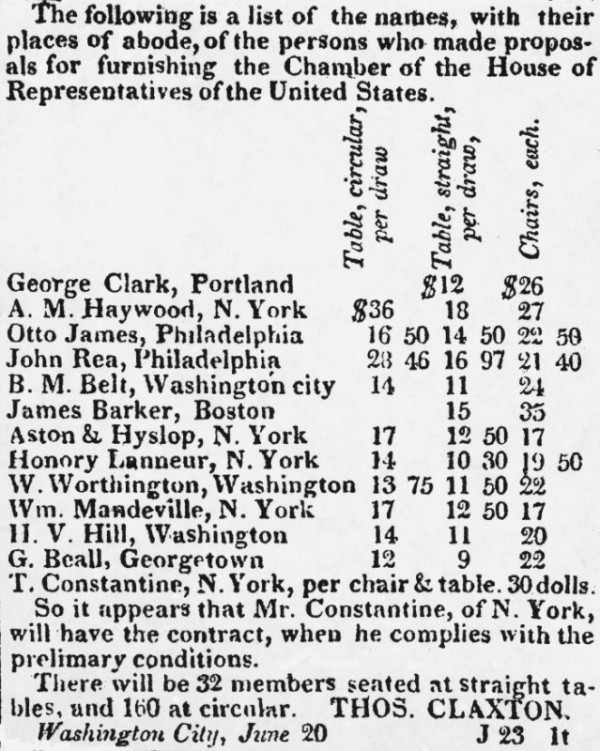

Advertisement, Mercantile Advertiser (New York), June 23, 1818. Constantine’s successful bid for the House commission was announced in newspapers in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. The name “Honory Lanneur” is a misspelling of Honoré Lannuier.

Charles-Honoré Lannuier, armchair, New York City, 1812. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with cherry and white pine; die-stamped brass, inlays. H. 36 3/8", W. 23 3/8", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Collection of the City of New York, City Hall; photo, Bruce White © 1998 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.) Lannuier produced a set of twenty-four armchairs for the Common Council Chamber at New York’s City Hall. He charged $336 for the chairs, which were upholstered by Henry Andrew (active 1809–1825) of New York.

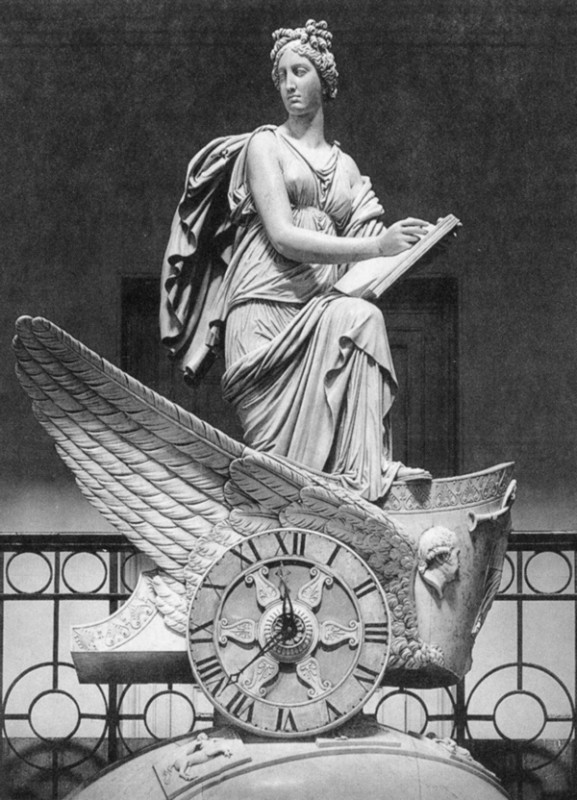

Carlo Franzoni, Car of History, Washington, D.C., 1818–1819. Marble. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Office of the Architect of the Capitol.) Simon Willard provided the movement for this sculpture, which sits above the north entrance to the House chamber, now Statuary Hall.

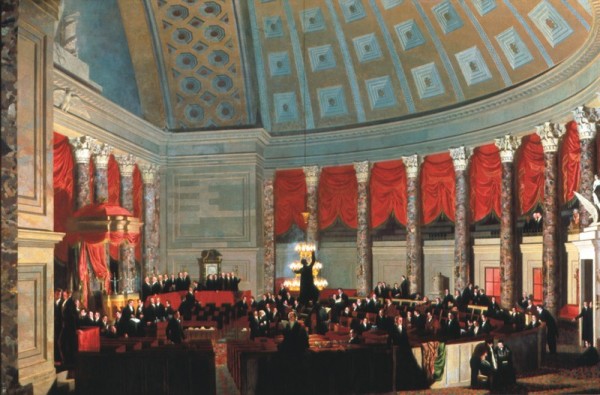

Samuel F. B. Morse, The House of Representatives, 1822–1823. Oil on canvas. 86 1/2" x 130 3/4". (Courtesy, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund.) Morse painted this epic work less than four years after the House of Representatives chamber was furnished. Though the painting depicts a fictional gathering of representatives, Supreme Court justices, and visiting dignitaries, Morse’s representation of the room was accurate. The left side of Franzoni’s Car of History can be seen at the far right.

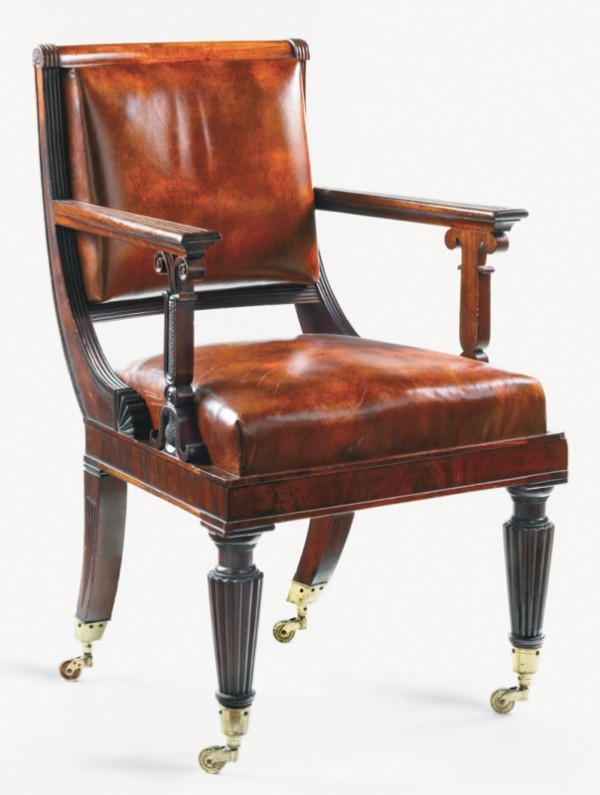

T. Constantine & Co., armchair, New York City, 1819. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with ash, white pine, and maple. H. 37 1/2", W. 23", D. 19". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.) This is one of two House of Representatives chairs that retain the T. Constantine & Co. label. The stretchers and woven hat rack were added after the chairs arrived in Washington.

Detail of the right leg of the armchair illustrated in fig. 14. The simple turning sequence at the top of the leg provided a unifying design for the representatives’ chairs and desks.

Armchair, New York City, 1788–1789. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with ash. H. 36", W. 23 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (Collection of The New-York Historical Society.) This chair is from a set manufactured for Federal Hall, Congress’s home during its brief stay in New York City.

Armchair attributed to Thomas Affleck, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1790–1793. Mahogany with oak. H. 34 1/4", D. 24", W. 24". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Henry P. McIlhenny, 1977.) The federal government hired Affleck to produce chairs and desks for the House and Senate chambers at Congress Hall, the former Philadelphia County Courthouse.

Armchair attributed to John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 37 1/2", W. 23 1/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives.) This chair is thought to be from a set of twenty-four mahogany examples commissioned by Maryland’s state senate in 1797.

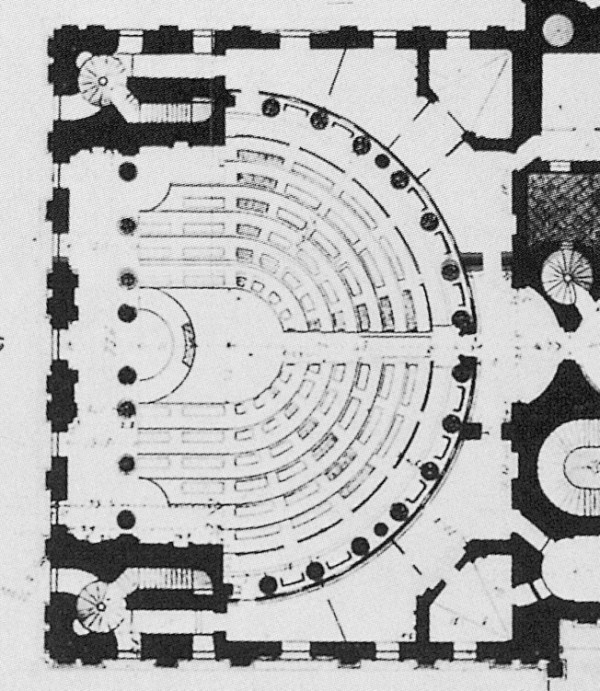

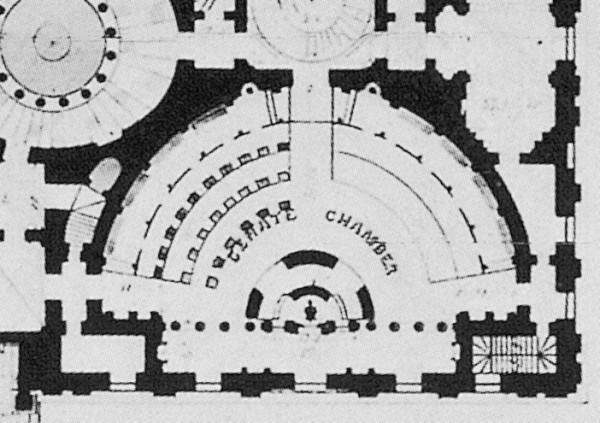

Detail of Alexander Jackson Davis’s plan of the first floor of the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C., 1832–1834. Drawing on paper. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) Davis’s measured drawings of the Capitol are considered the most trustworthy depictions of Latrobe and Bulfinch’s finished work. This view of the House chamber confirms the arrangement of desks on stacked risers as seen in Morse’s painting (fig. 13).

Desk attributed to T. Constantine & Co., New York City, ca. 1819. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 30 1/8", W. 47 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This two-person, straight-front desk is one of six that sat next to the rostrum used by the speaker of the House of Representatives (fig. 19). Most representatives shared a desk with at least one colleague, each having use of a drawer and shelf space. The turned legs resemble those on the House chairs (fig. 15).

William King Jr., armchair, Washington, D.C., 1818. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with oak, ash, and tulip poplar. H. 41 1/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 25 3/8". (Courtesy, White House Historical Association.) In addition to ordering French furniture for the President’s House, James Monroe patronized local cabinetmakers such as King, who designed a suite of twenty-four chairs and four sofas for the East Room.

Details of the arm supports from chairs by T. Constantine & Co. (a) armchair illustrated in fig. 23, (b) armchair illustrated in fig. 24, (c) armchair illustrated in fig. 35. Variations in the carving of a and b confirm that Constantine either had multiple carvers working on the Senate commission or that he outsourced work to other shops. The arm support on the far right is from a chair modeled after the same Hope design as the Senate chairs, but the ornament is more florid.

T. Constantine & Co., armchair, New York City, ca. 1819. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with maple. H. 38 5/8", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended in the family of Senator Jonathan Chace (R-Rhode Island, 1885–1889).

Armchair attributed to T. Constantine & Co., New York City, ca. 1819. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with maple. H. 38 3/8", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo Howard Agriesti.) Senator Hannibal Hamlin (R-Maine, 1857–1861, 1869–1881) took this chair home when he retired, and it remains in his family today.

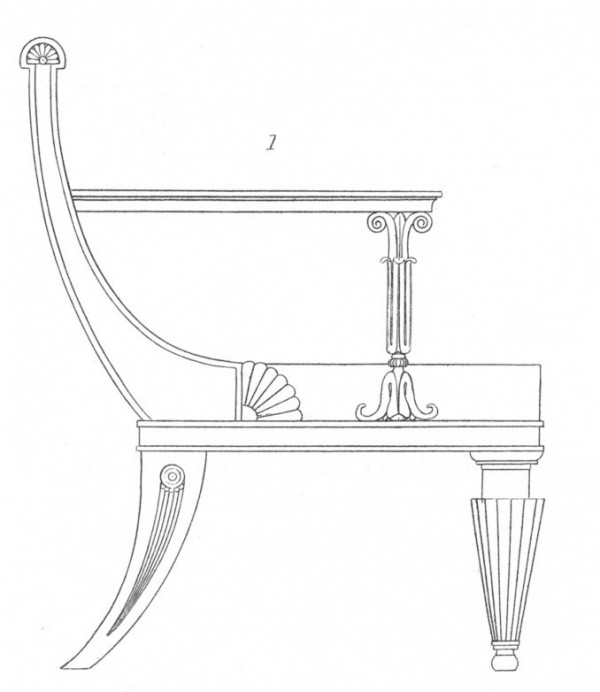

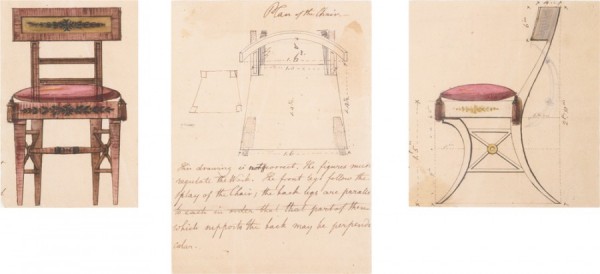

Design for an armchair illustrated in pl. 59 of Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807). The design of the Senate chairs was based on this image.

Desk attributed to T. Constantine & Co., New York City, ca. 1819. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and rosewood veneer with mahogany, tulip poplar, white pine, and ash. H. 35", W. 24 1/2", D. 19 3/16". (Courtesy, U.S. Senate Collection.) This is the only T. Constantine & Co. desk that did not have a supplementary writing box added above the original top in the second half of the nineteenth century. Plinths were placed under the trestles to raise the desk to the height of those with a writing box. Shelves were inserted beneath the desks in the 1830s.

Desk attributed to T. Constantine & Co., New York City, ca. 1819. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with mahogany, tulip poplar, and white pine. H. 35 3/4", W. 29 1/8", D. 20 1/8". (Courtesy, U.S. Senate Collection.) The right side of this desk is angled to conform to the curve of the risers in the Senate chamber (see fig. 30).

Detail of a drawer from the desk illustrated in fig. 27.

Detail of the side of the desk illustrated in fig. 26. Constantine selected elegant veneers for the Senate desks, including figured mahogany for the panels and mahogany or rosewood for the circular crossbanding.

Detail of Alexander Jackson Davis’s plan for the first floor of the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C., ca. 1832–1834. Drawing. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) As with Davis’s plan of the House, this drawing accurately reflects the distribution and orientation of desks on the Senate floor.

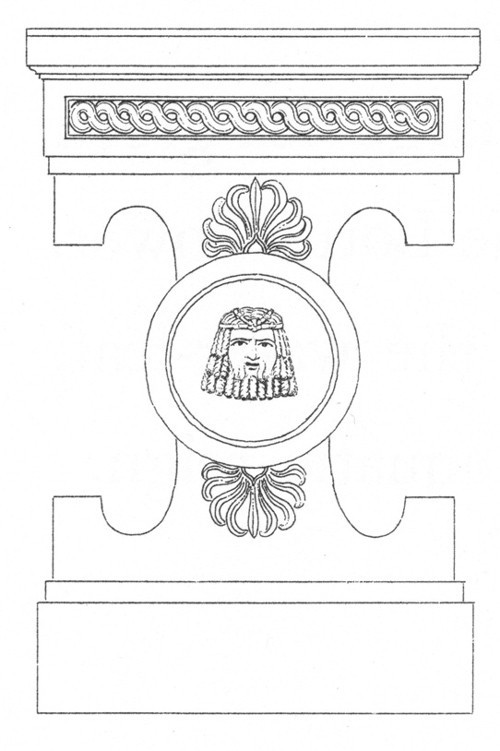

Design for a table illustrated in pl. 20 in Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807). The concept for the circular, crossbanded reserve on the Senate desk may have come from this trestle table design.

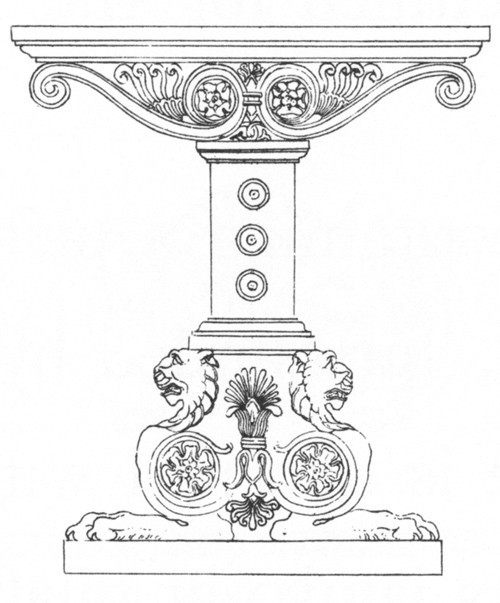

Design for a table illustrated in pl. 26 in Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807). The scrolled top of this table may have influenced the design of the Senate desks.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, drawing for a chair for the President’s House, 1809. Watercolor on paper. (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.) James and Dolley Madison commissioned Latrobe to design a suite of seating furniture for the President’s House, which was lost when the British burned Washington during the War of 1812.

Detail of the painting illustrated in fig. 13. Benjamin Henry Latrobe designed this chandelier and sconces in 1818 for the House of Representatives. The New York firm of Irving, Smith & Hyslop ordered these lighting devices for the House from an unidentified manufacturer in Birmingham, England.

T. Constantine & Co., armchair, New York City, 1824–1825. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with maple. H. 37", W. 23 3/8", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Though similar in appearance to the Senate’s seating furniture, this chair postdates the Senate commission and illustrates how Constantine continued to reference Hope’s Household Furniture later in his career.

Detail of the rear legs from T. Constantine & Co. chairs: (a) armchair illustrated in fig. 35, (b) armchair illustrated in fig. 44, (c) armchair illustrated in fig. 24. The rear legs of the chair illustrated in fig. 35 match those on the Christ Church armchairs of 1824–1825 (fig. 44) and not the Senate’s seating furniture (fig. 24) or the North Carolina State Senate chair (fig. 43). This evidence supports a post-1823 manufacture date for the chair illustrated in fig. 35.

William Barker after William and Thomas Birch, “Congress Hall and New Theatre in Chestnut Street,” from The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America; as it appeared in the year 1800, Philadelphia, 1800. Engraving on paper, 13" x 15 1/2". (Courtesy, The Library Company of Philadelphia.) During the federal government’s ten-year hiatus in Philadelphia, the House and Senate convened at Congress Hall, which was built adjacent to Independence Hall between 1787 and 1789 and was originally intended to serve as the Philadelphia County Courthouse.

House of Representatives Chamber, first floor, Congress Hall. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) Although none of Affleck’s House chairs and desks survive, their appearance is known through print sources dating to the 1790s.

Reproduction of an Axminster carpet by the Philadelphia Carpet Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1791. Wool with linen. 22' x 40'. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historic Park.)

Old Senate Chamber. (Courtesy, U.S. Senate Collection.) The chamber was restored between 1973 and 1976 to resemble its crowded appearance in the 1850s. By 1850 sixty-two senators and their desks and chairs shared a room that Latrobe had designed for forty-eight.

Castor, Birmingham, England, or New York, 1819–1825. Brass. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This castor is on a rear leg of the armchair illustrated in fig. 35. Identical castors are on the Senate chairs (fig. 23) and the armchairs for Manhattan’s Christ Church (fig. 44).

Castor, Birmingham, England, 1824–1825. Brass. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This castor is on a front leg of the armchair illustrated in fig. 35. This type of castor appears on the seating Constantine made for Christ Church, but not on furniture for the Senate commission.

Armchair attributed to T. Constantine & Co., New York City, 1822–1823. Mahogany and mahogany veneer. H. 35", W. 25", D. 24". (Courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History.) Intended for the speaker of the North Carolina State Senate, this chair was included on John Constantine’s upholstery bill. The front legs below the seat rail are replaced, and none of the original castors survives. The chair is also missing brass mounts that were attached to the seat rail, arms, and crest.

T. Constantine & Co., armchair, 1824–1825. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with maple. H. 27", W. 17 1/2", D. 25". (Courtesy, Westervelt-Warner Collection of Gulf States Paper Corporation, Museum of American Art, Tuscaloosa, Alabama; photo Barry Fikes.) Constantine produced this armchair, one of a pair, for Christ Church in New York City. The chairs were probably for the rector and his assistant.

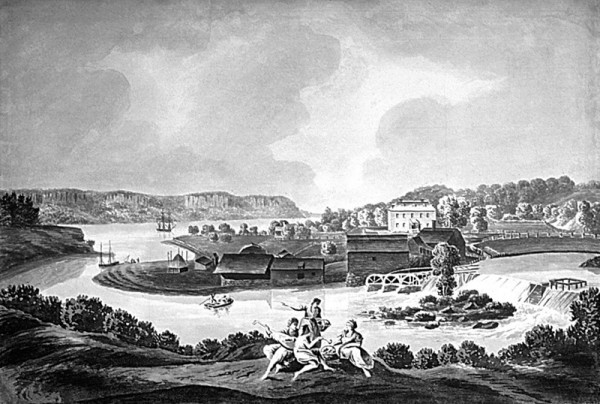

View of the Mills at Philipse Manor, ca. 1784. Watercolor on paper. 19 1/4" x 26 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic Hudson Valley, gift of La Duchesse de Talleyrand, PM.65.866.) In the late 1820s, after he closed his cabinetmaking business, Thomas Constantine owned the sawmill seen on the grounds of Philipse Manor.

Emanuel Leutze, William Seward, 1858. Oil on canvas. 97" x 63". (Courtesy, Union League Club of New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Seward (R-New York, 1849–1861) is shown seated in Thomas U. Walter’s new Senate chamber. The design of the chair and its castors suggest that Seward is seated in a T. Constantine & Co. chair from the Senate’s old room.

Roddiscraft, desk, Marshfield, Wisconsin, ca. 1959. Mahogany with mahogany, pine, and alder plywood. H. 35 7/8", W. 28", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, U.S. Senate Collection.) As new states entered the union, the Senate ordered additional desks. This particular example dates to the admittance of Alaska and Hawaii in 1959 and was constructed with the shelf, writing box, and metal grills as integrated components rather than as additions as are found on those attributed to T. Constantine & Co. (figs. 26, 27).

T. Constantine & Co., armchair, New York City, 1819. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with maple. H. 38 1/2", W. 23", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Beauvoir, Jefferson Davis Museum and Memorial Library.) Jefferson Davis (D-Mississippi, 1847–1851, 1857–1861) reputedly used this chair in the Senate. The chair was destroyed during Hurricane Katrina.

Bembé & Kimball, armchair, New York City, 1857–1858. Oak and oak veneer. H. 40 1/4", W. 25 1/4", D. 27 3/4". (Courtesy, Office of the Architect of the Capitol.) Thomas U. Walter, architect of the 1850s addition to the Capitol, designed this chair and others to replace the T. Constantine & Co. furniture in the House of Representatives chamber. John T. Hammitt’s Desk Manufacturing Company of Philadelphia manufactured half of the 262 chairs and Bembé & Kimball produced the remainder.

Doe, Hazleton & Co., desk, Boston, Massachusetts, 1857. Oak and oak veneer. H. 32", W. 46 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Office of the Architect of the Capitol.) Thomas U. Walter designed this desk and others for the representatives’ new chamber. Doe, Hazleton & Co. furnished all 262 desks.

December 6, 1819, the first session of the sixteenth Congress convened at the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. This otherwise unremarkable event was notable because the legislature had not met at its home on Capitol Hill in more than five years. Burned by British troops during the War of 1812, the congressional chambers required extensive repairs throughout (fig. 1). The Capitol was restored and thoroughly remodeled under the direction of Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820) and, after his resignation in 1817, Charles Bulfinch (1763–1844).

Above and beyond the structural damage resulting from the fire in the Capitol, the House and Senate lost all of their furnishings. Marauding British soldiers appropriated the legislators’ desks, chairs, and paperwork as fuel for the fire. When the senators and representatives returned to Washington for the sixteenth Congress, the replacements that awaited them represented two of the most extensive furniture commissions in early-nineteenth-century America. They also represented the patronage of a single New York firm, that of cabinetmaker Thomas Constantine (1791–1849).[1]

The tale of how this unheralded manufacturer earned the privilege of supplying the House and Senate with nearly $27,000 worth of furniture and decorative accessories provides an informative glimpse of the mechanics and meanings of public furniture in the early nineteenth century. Although the British bonfire at the Capitol prevents us from appreciating the Latrobe-era furnishings, the positive reception that Constantine’s replacement wares received in Washington and the associative value that extant pieces retain today suggest that Constantine successfully executed what he appropriately deemed all “the necessary and proper articles” for the legislative branch of the United States government.[2]

Another Master Cabinetmaker in New York

Few objects survive to shed light on Constantine’s early career, but records from the 1810s document his rapid ascent from apprentice to journeyman and then master craftsman. Born in 1791 in Derbyshire, England, Constantine was two years old when his family immigrated to New York, the same year that the French government, newly freed of Louis XVI, declared war on Great Britain and her allies. During this period of turmoil, the United States offered relocated artisans the possibility of commercial success. New York sailmaker Stephen Allen (1767–1852) recalled how the “belligerent state of all Europe had called into action the whole commercial resources of our country, and every kind of business flourished.” Perhaps word of such prosperity led blacksmith John Constantine (d. 1799), Thomas’s father, to bring his young family to New York.[3]

Constantine served an apprenticeship in cabinetmaker John Hewitt’s (1777–1857) shop at 191 Water Street between 1806 and 1812. Hewitt’s account books and correspondence indicate that he had a thriving business and monitored his competitor’s products with a careful eye. Between 1801 and 1805 he attempted to establish a cabinet wareroom in Savannah, Georgia, but his inability to make a financial success of the business forced him to return to New York. Apprentices like Constantine would have provided much-needed assistance as Hewitt began to rebuild his business in the North. Although Constantine ran away from his master in June 1811, during what would have been the final year of his apprenticeship, he returned to work as a journeyman for Hewitt between 1812 and 1814. Entries in Hewitt’s account book attest to the breadth of Constantine’s skills. Among the more demanding forms assigned to him were several expensive French sideboards. Despite the upheaval caused by the War of 1812, Hewitt’s staff remained busy and Constantine earned more than $1,100 between February 1812 and April 1814.[4]

After opening his own workshop in 1815 at 60 Vesey Street in New York’s fashionable Third Ward, in 1817 Thomas Constantine relocated a block south to 157 Fulton Street. In an advertisement for the sale of 60 Vesey Street, the shop was described as a “first Rate Stand for the [cabinetmaking] business,” with enough space to “hold ten benches, and sufficient yard.” Constantine may have moved into a larger building in anticipation of increased patronage. If so, his decision proved fortuitous. In 1818, at the age of twenty-seven, he received the commission to furnish the House of Representatives.

After arriving at 157 Fulton Street, the cabinetmaker established himself as T. Constantine & Co. and hung out his sign less than two blocks from the well-established furniture manufactories of Duncan Phyfe (1768–1854) at 168, 170, and 172 Fulton Street and Michael Allison (1773–1855) one block north at 46 and 48 Vesey Street (fig. 2). Located only a few doors from Broadway, Constantine’s shop was ideally situated to attract members of New York’s elite who came to stroll among the elegant businesses or resided in the fine boardinghouses and homes on Broadway and Chatham Row near City Hall Park (fig. 3). This area was deemed “a very acceptable breathing spot in the midst of everlasting bustle.” Despite the presence of heady competition, Constantine benefited from the concentration of cabinetmaking firms found in the area.[5]

Constantine’s prosperity in this period is suggested by his leasing of a second property in the neighborhood as well as by the steady increase in the value of his personal estate. Renting a house at 14 Dey Street enabled him to move his young family—wife, Ann Eliza Hall (1796–1866), and sons, John (b. 1817) and Thomas W. (b. 1818)—out of the Fulton Street store while also gaining additional storage or shop space in the rear yard behind his new home. By 1817 Constantine rented $10,000 in real estate, and the value of his personal possessions had increased from $200 to $1,000 in only three years. Money gained from his marriage in 1816 probably contributed to this increase in domestic wealth and provided additional capital for the lease of the Dey Street property.[6]

Two months before he accepted the House of Representatives commission, Constantine left his home on Dey Street and rented a large property at 538 Greenwich Street. Located between the congested business district of lower Manhattan and the country retreat of Greenwich Village, this property provided additional shop space and functioned as the family home. In the early 1820s, however, Constantine also referred to the Greenwich Street site as the company’s “manufactory” and frequently advertised that, in addition to his “warehouse” on Fulton Street, he sold furniture at 538 Greenwich near Newgate Prison, “where [T. Constantine & Co.]... will be happy to execute orders in their line on as reasonable terms as can be had in the city.”[7]

Constantine had a third production center outside New York City, which included a water-powered lathe. He is the only cabinetmaker in this period known to have operated such a facility. Although the specific location of this outpost has not yet been determined, the cabinetmaker advertised on May 5, 1821, that he needed a “good Turner to turn Mahogany work” at a lathe that “goes by water” and is located “within 20 miles of this city.” Such a mechanism trumped the wheel, treadle, or pole lathes typically associated with the workshops of this period by ensuring continuous rotation at an increased speed while also eliminating the need for manpower. Water-powered lathes had been used in Europe on an industrial scale to turn iron parts for machinery as early as 1710. While there is no documentary evidence, under Constantine’s direction, the turner could have supplied T. Constantine & Co.’s journeymen and apprentices as well as other New York cabinetmakers with a variety of turned wood elements such as table and chair legs and bedstead posts.[8]

Whether Constantine exported ready-made furniture to the South before the United States Capitol commissions remains to be discovered. Certainly, ample precedent for such endeavors exists in the activities of his contemporaries. The negative experiences of John Hewitt likely warned Constantine of the pitfalls of southern markets. The size of Constantine’s operation by 1820 suggests that he had the capacity to produce surplus furniture. With a large suburban manufactory and a separate lathe operation outside the city to complement his wareroom on Fulton Street, Constantine had the space, workforce, and materials to maintain stock-in-trade and compete in the export market.[9]

One of the few, labeled Constantine objects dating from this early period is a marble-top pier table that descended in the family of wealthy Bristol, Rhode Island, merchant James De Wolf (1764–1837) (fig. 4). Bearing the T. Constantine & Co. label of 1817–1820 (fig. 5), this table likely represents the more economically conservative production of bespoke work for export rather than the pursuance of a broader venture market. Ties gained from Constantine’s marriage to Ann Eliza Hall, whose family moved to New York from Providence in 1804, were the likely source for this commission. The pier table and its mate occupied a prominent position in the grand double parlor of De Wolf’s neoclassical mansion, the Mount (fig. 6). While the design of the table looks toward the French antique taste, the frieze, canted corners, and splayed paw feet are not well integrated, indicating that Constantine was less competent as a furniture designer than Phyfe and Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819).[10]

Despite such shortcomings, Constantine clearly had the ability to produce furniture perfectly suited for domestic and public needs. A labeled T. Constantine & Co. drop-leaf dining table (fig. 7), likely made for a wealthy patron, illustrates the point. Though accordion-action and telescopic extension dining tables were more common in New York, the “Cumberland Action” form allowed its owner to fill a large dining room with a table that could accommodate more than sixteen guests but could also be collapsed when not in use. This simple Constantine example lacks elements such as reeded pillars and claws, a reeded table edge, and brass paw feet, but the chaste, ring-turned pillars evoke a sense of Regency elegance and belies its solid construction.[11]

The Capitol Comes Calling

Following the War of 1812, Congress briefly debated both the relocation of the national capital and the abandonment of the ruins of Latrobe’s building for a new site in Washington. President James Madison (1751–1836) ended the discussion by approving a loan of $500,000 in February 1815 to rebuild both the Capitol and the President’s House at their current locations. Latrobe returned to the District of Columbia to oversee the renovations but resigned in late 1817 amid extensive consternation over his alleged extravagance, arrogance, and mismanagement.[12]

Congress quickly located a capable replacement in New England architect Charles Bulfinch, whose Massachusetts State House had earned him great acclaim. For those who thought the “superb pile” that was the Capitol deserved “to be finished in a manner to do credit to the country and the age,” Bulfinch was an ideal successor. Where Latrobe offered impossible promises and habitually overran budgets, Bulfinch made progress at an unprecedented rate and strove to limit overspending.[13]

Though the marvelous rotunda at the center of the Capitol was not finished until 1824, Bulfinch saw to the completion of the House and Senate chambers by 1819 (fig. 8). Anticipating its return to the Capitol in the spring of 1818, Congress had already begun to discuss the funding required for equipping the chambers. During their exile from Capitol Hill, the legislative branches met at the Brick Hotel, a renovated tavern that came to be called the Brick Capitol (fig. 9). The congressional members were eager to improve their surroundings, and the furniture procured for their use at the Brick Hotel would not suffice. They required new tables, chairs, carpets, and draperies to complement as well as supplement the appearance of the legislators’ new chambers. With T. Constantine & Co.’s well-built and chastely designed furniture in hand, the older goods were deemed “not wanted for the present chamber” and consequently sold at public auction.[14]

Although the stylish new Capitol mandated an accompaniment of modish furniture, typically the funds to procure such necessities were not handed over willingly. Debates concerning public expenditures for the construction of the Capitol were frequently hostile, with popular opinion holding that less equaled more. Louisiana senator Eligius Fromentin (ca. 1767–1822) represented this conservative viewpoint when he argued in 1815 that “Our laws to be wholesome need not to be enacted in a palace.” In an age when few American government structures and only a few more ecclesiastical buildings could be considered notable for design, scale, or cost, not all politicians understood or accepted the young nation’s need to house its Congress in grand surroundings. Even though the French-born Fromentin was likely accustomed to the fineries of life, as a congressman from Louisiana he could not support the wanton excesses of Latrobe’s plans.[15]

Despite such outcries, the House and Senate begrudgingly authorized the funds required to house and furnish the Capitol according to Latrobe’s desires. Years earlier, in 1809, Latrobe had approached Congress to secure $10,000 to shelter the Senate in a temporary facility within their chamber, which was under construction. According to designs conceived by Philadelphia decorative painter George Bridport (ca. 1770–1819), this temporary room would feature elaborately ornamented walls with trompe-l’oeil fasces. Latrobe’s budget also included funds for carpet, furniture, and draperies for the finished chamber. He explained to the legislators that the old desks would not complement the yet-to-be-completed room.[16]

With the 1817 departure of Latrobe, the responsibility for the procurement of the Capitol’s furnishings fell on the shoulders of Bulfinch and the heads of both houses of Congress. The legislature authorized money for the refurnishing of the re-created chambers on April 20, 1818, in an act “for furnishing the Capitol and the President’s House.” While dwarfed by the sums necessitated by repairs to the building itself, the numbers were staggering for their day. The senators received $20,000, and, in recognition of the greater numbers in the House, the representatives were provided with $30,000.[17]

“Without any superfluous ornament”: The House Commission of 1818–1819

With money in hand, the House quickly set out to commission the requisite cabinetmakers, carpenters, and upholsterers. Even though the act stipulated that the Speaker of the House, Henry Clay (1777–1852), would have discretionary power in all matters relating to the expenditures, the Kentuckian relied heavily on Thomas Claxton, longtime doorkeeper of the Representatives’ Hall. While evidence suggests that Clay and Claxton possessed Latrobe’s designs for the Capitol’s architectural interior and decorative arts and conferred with him regarding these matters after his departure, they also sought out the opinions of a broad range of craftsmen.[18]

With the House chamber close to completion, Claxton contacted Henry V. Hill (active 1813–1836), a local cabinetmaker who often supplied the Capitol’s furniture-related needs. He hoped Hill could develop a prototype for the desks and chairs that the House required. By consulting Hill, Claxton and Clay could experiment with the style and specific dimensions of the furniture that would best suit the House as well as estimate the cost of such a commission. With this information in hand, Claxton placed an advertisement on May 12, 1818, that requested bids from interested cabinetmakers. Circulated in newspapers in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, his advertisement solicited proposals for “supplying the Representative Chamber, one hundred and eighty seven armed Chairs, and fifty-one Tables.”[19]

Claxton made Hill’s prototypes available for examination in Washington, but he also aided those outside the city by including very specific instructions as to the materials, proportions, and design of the House furniture in his advertisement. The chairs were to be “made out of the best St. Domingo mahogany, well seasoned, strong neat and plain; without any superfluous ornament.” Their arms were to have “a scroll in front,” and their seats were to be “stuffed with hair, and covered with the best hair cloth.” Representatives would sit at multiperson tables, which Claxton specified should have a slanted top “in the usual form of writing desks,” a “good draw,” and legs “turned agreeable to the sample, which will be simple in form.” Claxton and Clay were not interested in fashionable provisions, but they did admonish those who thought themselves “fit to offer proposals” that “every article is to be of the first quality—and the best workmanship.” When considering these stipulations, it is clear that the House’s interests were firmly focused on utility and durability.[20]

With the hope that cabinetmakers capable of providing functional and well-made furniture would be interested in the House’s patronage, Clay and Claxton awaited the June 18, 1818, deadline for submissions. Despite the broad circulation of their request, they received only thirteen replies. On June 23, 1818, the same newspapers that ran the advertisement notified all concerned that “Mr. Constantine, of N. York,” would have the honor of furnishing the House of Representatives (fig. 10). In his request for proposals, Claxton had promised that the low bid would be awarded the commission, and he remained true to his word. Constantine had agreed to supply each congressman with a chair and space at a table for $30 each, a significant discount from the proposals of his competitors.[21]

The cabinetmakers submitting bids hailed almost exclusively from New York, Philadelphia, and Washington. Had Claxton placed the advertisement in a Boston newspaper, perhaps he would have received more than two responses from New England cabinetmakers. Though the list of respondents was short, a number of significant artisans were represented. Most notably, “Honory Lanneur” was the runner-up to Constantine. The renowned French émigré ébéniste Charles-Honoré Lannuier had provided an elegant set of chairs for the Common Council Chamber at New York’s City Hall in 1814, but he exceeded Constantine’s estimate for the House commission by $550 (fig. 11). Of the capital-area contenders, Henry Hill, William Worthington (active 1800–1822), and Benjamin M. Belt (active 1801–1822) had supplied furniture for either the legislature or the president at one time or another. Philadelphian upholsterer John Rea (ca. 1775–ca. 1855) had worked with Latrobe on the Capitol’s interiors since at least 1807.[22]

An intriguing aside to Clay and Claxton’s furniture commission is the lack of evidence to suggest a public bidding process for any other aspect of the House of Representatives’ interior decoration. Apparently such bureaucratic measures were deemed unnecessary for the extensive contracts offered to the aforementioned Rea for drapery, carpet, and upholstery, as well as the thirty-one remaining items on Clay’s list of expenditures for the Representatives’ chamber. In addition to the $7,920.63 Rea received, which exceeded even Constantine’s charges, these payments included $3,957.03 to the New York mercantile firm Irving, Smith, & Hyslop for lamps, chandeliers, and additional carpeting, and $420.00 to Simon Willard (1753–1848) for the clock inserted in the wheel of sculptor Carlo Franzoni’s (1789–1819) Car of History (fig. 12). As will be discussed later, this form of direct patronage characterized Constantine’s involvement in the furnishing of the Senate’s chamber.[23]

When construction on the Representatives’ chamber came to a close in the fall of 1819, Clay and Claxton began to assemble their purchases in the new facility. John Rea and Henry Hill remained on hand to oversee the various craftsmen required to lay carpeting, hang drapery, mount furnaces, and complete the myriad other tasks involved in the installation. Samuel F. B. Morse’s (1791–1872) monumental painting The House of Representatives attests to the success of their efforts (fig. 13).[24]

The glory of the Representatives’ chamber distracts the casual viewer of Morse’s painting from recognizing the utilitarian quality of the New York furniture in the room. Reflecting Clay and Claxton’s desire for materials that were “strong, neat and plain,” T. Constantine & Co. produced simply designed utilitarian desks and chairs (figs. 14, 20). The public received these wares warmly, and Washington’s National Intelligencer reported that the work “is said to be equal to anything of the kind for strength, solidity, and excellence of workmanship manufactured in the United States.” Furthermore, the furniture had “received the approbation of all who have seen it, and particularly that of the best judges of cabinet work.”[25]

The means by which Constantine arrived at the exact design of the desks and chairs remain speculative. Whether Hill’s prototypes were sent to New York after Constantine received the commission is not known. The editorial in the Intelligencer made no reference to the appearance of the wares, their reception as fashionable or desirable commodities according to the representatives’ expectations, or how well they fulfilled the current preference for classical ornament. The only nod toward refinement found on these chairs is the brass nails that outline the frames over the durable black haircloth coverings (fig. 15). In the 1820s and 1830s Washington cabinetmakers added the woven racks below the chair seats to provide the representatives with a convenient location to store their hats (fig. 14).[26]

The simplicity of the furniture purchased for the House of Representatives can be attributed to Henry Clay’s taste as well as to Claxton and Hill’s influence. Clay passed the responsibility of procuring the chairs and desks to Claxton, but he would have likely retained veto power over their design. Though Clay owned an elegant, Latrobe-designed mansion outside Lexington, Kentucky, and outfitted Decatur House in Washington with expensive furnishings in the late 1820s, he had previously demonstrated his ascetic leanings in the public sphere during the planning for President Monroe’s inauguration in early 1817. Clay refused to allow the senators to bring their “fine red chairs” into the House chamber for the ceremonies because the representatives’ “black ones were more becoming.” The resulting squabble proved so acrimonious that Monroe was sworn in outside, the first president to do so since Washington’s inauguration in New York twenty-eight years before.[27]

The chairs that arrived at the Capitol in October 1819 borrowed elements from the “square back chair” listed in the 1817 New York price book but also referenced the furniture built for previous congressional chambers. A set of four chairs thought to be from New York City’s Federal Hall, the federal government’s home in 1789, may have been a precedent for the furniture Constantine manufactured for the representatives (fig. 16). The Federal Hall chairs appear to be the initial manifestation of what would become the standard form for the House’s seating furniture: an upholstered, square-back, open-arm chair. A group of chairs ordered from Thomas Affleck (1740–1795) for the Senate to use during its stay in Philadelphia survives (fig. 17) and, other than their tapered and molded front legs, their general profile is consistent with those produced in New York in the late 1780s and by Constantine in 1819. While none of the furniture Affleck made for the House survives, historians believe these pieces would have closely resembled those he produced for the Senate and that the chairs of the two legislative bodies would have been distinguished by the color of their upholstery rather than by their design. Since Claxton served as doorkeeper for the House of Representatives when the legislature met in Philadelphia, he could have directed Hill or Constantine to adapt the design of Affleck’s seating furniture.[28]

Although Affleck and Constantine worked during different stylistic movements, the common use of an upholstered back differentiates their work from the chairs found in other American statehouses. Certainly the comfort of the nation’s legislators, who would be sitting for prolonged periods debating the efficacy of laws and public policy, justified such an expense. Many states in the early federal period, however, did not provide this luxury for their own government representatives. Congressmen in Maryland, for example, sat on more typical, neoclassical-style armchairs with open wooden backs and upholstered seats (fig. 18). Only Maryland’s president of the senate and speaker of the house received chairs with a padded back, which shared the shield back found in the other seating furniture.[29]

At Clay and Claxton’s request, Constantine constructed the desks for the House of Representatives to function within the chamber’s floor plan. Most are curved to accommodate the semicircular shape of the room and the risers on which they are placed (fig. 19). The House ordered an additional fourteen straight-front desks to flank the speaker’s rostrum. The desks generally follow the 1817 price book guidelines for a “writing table.” Sturdy yet plain, they have turned legs that support the writing surface and connect the tables to the design of the chairs (fig. 20). Constantine produced tables in a variety of lengths: a small number of congressmen had the privilege of sitting at an individual desk while the remainder sat at tables for two, three, or four legislators. The representatives did not keep offices at this time, so the table, locked drawer, and bookshelf below represented their entire work environment. The use of a fixed top rather than a hinged lid to provide access to the desk’s interior further limited the amount of storage space.[30]

Thomas Hope and the English Regency in Washington:

The Senate Commission of 1819

Washingtonians were so impressed with Constantine’s provisions for the House of Representatives that Daniel D. Tompkins (1774–1825), vice president under James Monroe, offered the cabinetmaker a contract for the Senate chamber furnishings without seeking a public bid. The vice president received control over the Senate’s interior decorating budget in the same April 1818 act that awarded Henry Clay discretionary power for the House’s purchases. Tompkins delayed commissioning furniture and decorations until late October 1819, only six weeks before the first meeting of Congress in the refurbished Capitol. Architectural historian William C. Allen describes the rapidity with which “crimson drapery, mahogany furniture, and brass lighting fixtures” were assembled to “restore the overall impression of luxury and taste” to the chamber. Vice President Tompkins retained Constantine to provide “at the expense and cost [of the Senate] the necessary and proper articles of furniture for the chamber and the committee rooms of the Senate.”[31]

Whereas Clay and Claxton purchased furnishings from a variety of sources, Tompkins relied exclusively on Constantine as an agent in the acquisition of everything from chairs and desks to the “lamps, carpeting, stoves,” and “damask and Moreen” that would complement his furniture. In an astounding feat of mercantile and manufacturing abilities, by December 1819 Constantine completed enough of the order to “enable the Honorable Senate to occupy their own apartments at the meeting of Congress.” Constantine claimed to have acquired these provisions “with cash in the city of New York without his having any gain thereon.” The extent of this financial outlay is astounding. The chairs, desks, tables, and sofas he provided cost $6,925 and included furnishings for the Senate Hall, committee rooms, and the President’s Room. Lighting devices, carpets, and draperies constituted an additional $7,000 worth of merchandise.[32]

Tompkins’s dependence on a New York artisan for the Senate’s decorative needs likely stems from an allegiance to his home state, an understanding of that city’s premier role in the production of domestic goods, and recognition of the limited capabilities of the local market. The legislature could not afford the fine foreign-made parlor furniture that wealthy elites of this era purchased for their homes. Inexpensive utilitarian pieces could be found easily enough in the capital’s furniture warerooms, but for more fashionable household goods, many Washington residents looked elsewhere. On arriving in Washington in 1817, Bulfinch wrote to his wife in Boston, informing her that “furniture of the common kind may be bought here as cheap as” in Massachusetts. For the most current and stylish furnishings, many Washingtonians turned to New York. After moving to the capital from Richmond in 1817, United States Attorney General William Wirt (1772–1834) informed his wife, Elizabeth (1784–1857), that Susan Wheeler Decatur (1777–1860) “insists most strenuously that you should depend on the furniture you have for this winter, and get what you want from N. York in the Spring—She has tried it and you must not get your furniture here.”[33]

Thus, like many Americans in the early nineteenth century, Congress ultimately turned to New York for its decorating needs. This use of an outside source for fashionable household goods was especially important in Washington, where the gibes of foreigners and fellow countrymen alike against the appearance of the capital’s public and private buildings were an “ever present reminder to the men in power of the low esteem in which power was held.” Washingtonians were transient and diverse by nature, but they recognized the need to create an appearance of refinement both in their homes and in the government’s buildings. Some strove to balance the limitations of their local environment with an ambition that was national in scope. European diplomats and cosmopolitan Americans introduced these Washingtonians to the symbols of sophistication required to ward off criticism of their built environments and interior spaces.[34]

Tompkins may have considered New York the most logical source of stylish furnishings, but the craftsmen of Washington were likely disgruntled when he handed Constantine the Senate commission without first soliciting bids. Henry Hill and William Worthington, who had provided furniture for both the Capitol and the President’s House before 1819, would have taken issue with this blatant disregard for their past service. William King Jr. (1771–1854), who made elegant armchairs for the East Room of the President’s House during the Monroe administration (fig. 21), certainly must have felt he could have produced the Senate suite at a level of design and durability equal to Constantine’s.[35]

Although Tompkins’s decision to place the Senate’s needs in the hands of a single artisan, especially someone of Constantine’s young age, represented a leap of faith, he was not disappointed by the cabinetmaker’s efforts. A letter from William Irving, the New York merchant who provided carpeting and lamps for the Representatives’ Hall, to Henry Clay described the commitment Constantine made toward successfully furnishing the Capitol: “Mr. Constantine, the person employed here, as upholsterer or cabinet maker for the Senate,” called on Irving to inquire after carpets “as he had done several times before.”[36]

The mobilization of manpower and the quick turnaround needed between the House and Senate commissions placed immense demands on Constantine’s workforce. Constantine clearly recognized this pressure and, with only six weeks to fill Tompkins’s order, he looked for assistance from his fellow craftsmen. In a desperate and unprecedented plea, Constantine notified his New York peers in the November 2, 1819, issue of the New-York Daily Advertiser that “About twenty Sofa Makers will find immediate work either in or out of the shop.” Constantine needed these extra hands to construct the frames for the Senate’s seating furniture, which would then be upholstered elsewhere.[37]

Contemporary manuscripts suggest that cabinetmakers occasionally turned to this practice of outsourcing, or jobbing, to supplement in-house production, but furniture historians have not yet developed a formal analysis of the methods and consistency with which mechanics used their fellow craftsmen for assistance. Although the location of shop owners such as Constantine and Phyfe can be traced through directories and tax records, early-nineteenth-century journeymen cabinetmakers and carvers in New York appear less frequently in the documentary record. Thus, the specific makeup of a given manufactory is difficult to establish. However, with suggestive advertisements such as the one mentioned above, this form of subcontracting can be inferred. Variations in dimensions among the surviving Senate chairs suggest that the chairmakers and carvers worked from the same plan but did not use the same templates. Furthermore, the inconsistent execution of the lotus leaf and crosshatch carving found on the arm supports indicates not only multiple carvers of diverse skill levels but also that these artisans worked in separate locations (fig. 22).[38]

Once the outsourced frames were completed, Constantine had a capable assistant to supervise the covering of the chairs for both the House and Senate in his younger brother John (1796–1845). Only twenty-three in 1819, John Constantine shared the Fulton Street property with Thomas and took on the responsibility of overseeing the upholstery of the chairs produced for the Capitol. John also likely contracted with local merchants to procure the extensive yardages of embossed moreen, silk damask, silk fringe, and Hessian that the Senate commission required. Constantine’s bill to the Senate included a $180 charge for “Work putting up ornamental work in the Senate Chamber,” which implies that either Thomas or John traveled to Washington to oversee the installation of the drapery, carpeting, and a cornice.[39]

The Senate commission represented a vast departure from the House contract not only in terms of the breadth of Constantine’s involvement but also in the quality of the furniture he provided. The dollar figure that Tompkins allocated for the senators almost tripled the cost of the goods provided for the representatives. The $80 price tag on the chair and personal desk allotted each senator dwarfs the $30 put toward each member of the House: for 48 senators, Tompkins spent just $1,200 less than what Clay paid to outfit 192 representatives. The difference in these expenditures is explained by the higher-quality materials and more elaborate ornamentation of the Senate’s furnishings. Figured mahogany veneers, carved arm supports, reeded legs, and red morocco leather on the Senate furniture (figs. 23, 24) cost more than the plain-grained mahogany, simple turned elements, and black horsehair fabric used on the House furniture.[40]

While the representatives sat on armchairs designed from commonly used parts described in the New York price books, the senators sat on thronelike seats taken from English designer Thomas Hope’s (1769–1831) seminal expression of French empire and English regency taste, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807). The Senate chair design was taken directly from plate 59, no. 1, which Hope labeled an “Arm-chair” (fig. 25). Hope’s treatise featured line drawings of the furnishings in his fashionable London town house. A member of a successful Dutch banking and mercantile family, Hope used his wealth to pursue a fascination with past cultures and classical purity. Inspired by the grandeur of ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome and the opulence of Napoleonic France, Hope crafted his interiors by consulting the work of prominent Parisian designers such as Charles Percier (1764–1838) and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (1762–1853).[41]

The aspirations of the manufacturer, Constantine, and his client, the Senate, were embodied in the design credo of Hope, whose stated purpose was to create “objects of lasting perfection and beauty, [that] might have increased in endless progress the opulence of the individual, and the wealth of the community.” Despite his reliance on Continental designs and immigrant craftsmen to construct these fonts of virtue, Hope insisted that by constructing his furniture and interior decorations in England, his country would no longer be reliant on “those commodities which had heretofore only appeared in the repulsive and unpatriotic shape of expensive articles of foreign ingenuity.” This sentiment would have resonated with many American consumers and mechanics as they lamented their neighbors’ preference for fashionable domestic goods produced abroad. With furnishings made in New York under Constantine’s direction, yet in accordance with Hope’s ideology and aesthetic, the senators could admire their cultured surroundings and congratulate themselves that their own countrymen were responsible for the furnishings.[42]

The reeded front legs and lotus-blossom motif on the arm supports of the Senate chairs were derived from ancient Egyptian architecture and decorative arts, but it is unlikely that many of the senators or even visitors to the chamber would have known the design source. Indeed, many early-nineteenth-century cabinetmakers and their patrons remained oblivious to specific precedents, considering individual motifs as nothing more than component parts of a broad classical fabric. Thomas Sheraton, for example, argued that “reeding appears almost the only ornament that has escaped the notice of the ancients.” Regardless of their ability or inability to pinpoint the origins of the decorative devices, the public would have interpreted the grandeur and motifs of T. Constantine & Co.’s seating furniture as reflections of the power and authority of the senators.[43]

As is the case with other furniture documented and attributed to Constantine’s shop, the Senate chairs are well constructed. The surviving Senate chairs attest to the durability of the joinery and the quality of the materials used by his workmen. All have solid mahogany frames and maple cross-braces set into half-shouldered dovetails. The daring rake of the rear, klismos-style legs in Hope’s design is subdued in the Senate chairs to take advantage of the additional strength offered by the long grain of the mahogany. Although the chairs show wear consistent with their age, they have otherwise survived in good condition, which speaks to the skill of the craftsmen who manufactured the frames.[44]

The Senate chairs are an elegant adaptation of Hope’s design, which was a profile line drawing that left much to the imagination and interpretation of the chair maker. Constantine’s workmen made the seat frames of the Senate chairs extra deep for additional strength. They applied figured mahogany crossbanding to offset the horizontal orientation of the seating. The grain of the mahogany used for the stiles emphasizes the upsweep toward the crest rail in a similar manner. Details retained from Hope’s design include the reeding on the front and back legs and the sunburst carving at the junctions of the seat rail and stiles and the stiles and crest rail.

The carving on the arm supports represents the most significant departure from Hope’s design. The introduction of cross-hatching into Hope’s knotted lotus motif added breadth and visual stimulation to the braces. This carving technique could be executed more swiftly than elaborate foliate elements and it required less skill, which would have allowed subcontractors of varying proficiency to produce the Senate chairs in the allotted time.

The Senate desks also feature impeccable craftsmanship and high-quality woods (fig. 26). T. Constantine & Co. designed each desk according to its specific placement in the semicircular chamber so that the desks would conform to the curve of the risers. The desks placed on the outside aisles are narrower and more trapezoidal, whereas those toward the middle of the aisles are wider and squarer (figs. 27, 30). The secondary woods used in the Senate desks include mahogany, ash, white pine, and tulip poplar, with some variation. The fixed tops are solid mahogany, while the case sides and trestles are covered with a mahogany veneer and mahogany or rosewood crossbanding that conforms to a central circular reserve (fig. 29).

While a design precedent has been found for the Senate chairs, the design source for the Senate desks is harder to determine. Library and sofa tables of this period were constructed with trestle bases like those on the Senate desks, but they typically include four turned and/or carved columns attached to trestle feet instead of the two paneled sides found on the Senate desks. Like the House writing tables, those made for the Senate have a slanted, stationary lid and a working drawer below. The House tables came with shelves, but the Senate desks had shelves added below after they arrived in Washington. Later in the nineteenth century, supplementary writing boxes were placed on top of the stationary lids to provide additional storage space (fig. 27).[45]

Hope’s Household Furniture could have provided inspiration for the Senate desks. In the illustration of his picture gallery on plate 2, Hope included a single table in the right foreground. The same table, shown larger and with more detail on plate 20, is similar in general profile to the Senate desks (fig. 31). Constantine’s desks also relate to Hope’s example in the shape of their trestle feet, the scroll of their bases at the juncture with the top, and their central circular reserves and crossbanded borders. Additionally, the applied roundels on the scrolls at the top of the supports may be a reflection of the scrolled trestle panels of the library table illustrated in plate 26, no. 7 in Household Furniture (fig. 32).

Although it is uncertain who was the driving force behind the incorporation of Hope’s designs in the Senate furniture, arguments can be made on behalf of Latrobe, Bulfinch, and Constantine. Some consider Latrobe, an Englishman who closely followed the progress of European taste, the most likely candidate. While his library is known to have been extensive, there is no documentation that Latrobe owned a copy of Household Furniture. Latrobe’s plans for architectural facades and interior decoration nonetheless demonstrated an intimate familiarity with refined classical ornament. This is best seen in his designs of 1809 for furnishings for the President’s House (fig. 33).[46]

A precedent for Latrobe-designed Capitol furniture is found in an 1807 letter to Philadelphia upholsterer John Rea. In this correspondence, Latrobe ordered Rea to acquire “blue or crimson good stuff or leather” and seventy or eighty yards of paneled Brussels carpet in crimson for the seats and backs, respectively, of chairs “appropriated to the Senators when visiting the house of Representatives.” Latrobe promised to forward “complete drawings of these seats” to Rea so that more specific arrangements could be made.[47]

Despite his resignation in 1817 as architect for the Capitol and Bulfinch’s assumption of supervision of the reconstruction project and redesign of the yet-to-be-completed portions of the building, Latrobe remained involved on a limited basis. His role in designing the House’s chandelier indicates that either Clay or Claxton solicited Latrobe’s opinion (fig. 34). He certainly did not have a say in the design selected by Claxton and Clay for the House furniture, since a man of Latrobe’s worldly tastes would never have allowed such unimpressive chairs and desks to deface the opulence of his Capitol.[48]

Another argument suggests that Latrobe may have left behind plans for furniture when he gave notice. Bulfinch referred to “a great number of drawings” passed on from his predecessor that “exhibited the work already done, and other parts proposed, but not decided on.” Bulfinch also informed the Senate of Latrobe’s exquisite design for its chamber and his intent to “exhibit favorable specimens of correct taste and the progress of the arts” in America.[49]

It is unlikely that Bulfinch would have advocated use of Hope’s designs. According to architectural historian Charles Cummings, although Bulfinch’s buildings were “marked by sincerity, refinement of taste, and an entire freedom from excess or affectation, and an intelligent adaptation to their various needs, he was not an innovative designer.” The New England architect created sound plans that achieved beauty in their chaste simplicity and coherent organization, but he had “little facility as a draughtsman” and lacked a “historical knowledge of architectural styles.”[50]

Bulfinch never fully escaped the influences of the chaste neoclassicism of the late eighteenth century. He admitted that the drawings rendered by Latrobe were “in the boldest style” and “calculated for display.” Bulfinch, however, preferred a more staid interior. He provided the design for the desks and chairs in the Supreme Court’s chamber, a room whose architectural plan was entirely his creation, but there are no extant examples of this commission to speak to his lack of interest in the fashionable antique style or his preference for the utilitarian sensibility of the House chairs and desks.[51]

It is also possible that Tompkins left the design of the Senate furniture entirely in Constantine’s hands. New York booksellers advertised copies of Household Furniture as early as 1819. Whether Constantine owned Hope’s book before he received the Senate commission is debatable, but the cabinetmaker’s use of details illustrated in plate 59 in later commissions (figs. 35, 43, 44) suggests that he had access to a copy of Household Furniture from at least 1819 to 1825. The chair illustrated in figure 35 represents a development on the Senate chair design (figs. 22-25), but it probably dates from the mid-1820s. The castors on the rear legs are marked “T. CONSTANTINE N. YORK,” whereas those on the front legs are marked “BIRMINGHAM PATENT” (figs. 41, 42). The carving on the rear legs of this chair is similar to that on seating Constantine made for Christ Church in New York City circa 1824 or 1825 (figs. 36, 44). John Constantine must also be considered a possible advocate for Hope’s designs. Recognition for the production of furniture consonant with Hope’s elegant interiors would have proved advantageous in the competitive market for cabinet wares and upholstery in New York’s Third Ward.[52]

Another theory is that different individuals designed the Senate chairs and desks. This would explain why the desks are an apparent abstraction of Hope’s designs while the chairs are a more direct quotation. The dimensions of the furniture also support this argument, since the desks were not constructed to allow the clearance required by the chairs’ arms. Consequently, a seated senator could not roll his chair underneath the desk. This shortcoming suggests that two people collaborated on the design of the Senate commission but failed to match the two components appropriately.[53]

Interpreting the Hierarchy of Style in the Capitol Commissions

The aesthetic differences between the House and Senate furnishings are significant beyond their role as examples of design history. The design of the desks and chairs tells a compelling story about popular perceptions of the Senate and House and about the distribution of power and prestige that came to define their legislative responsibilities. They reaffirm the separation of Congress into an upper house and lower house as defined by Article I of the United States Constitution. In this period, senators were appointed by their respective state governments and generally were considered the most learned and well-bred citizens of the country. In contrast, representatives were elected directly by the common man and typically seen as less refined, self-educated men who lacked the pedigree and edification of their upper-house counterparts.

T. Constantine & Co.’s furniture for the Capitol reflected the relationship between the House and the Senate. This design hierarchy had precedent in the furnishings of previous Capitol buildings and was largely codified during the decade the federal government was located in Philadelphia. From 1790 to 1800 the Senate met on the second floor of Congress Hall (fig. 37), above the House of Representatives’ chamber. The senators sat on chairs upholstered in red leather and worked at individual desks, whereas the representatives received similar chairs with black leather upholstery and worked at long, multiperson writing tables (fig. 38). The most conspicuous object purchased for the Philadelphia capitol was a large Axminster carpet featuring the Great Seal of the United States of America (fig. 39). The carpet covered the floor of the Senate chamber, clearly distinguishing the members of the upper body from their colleagues downstairs.[54]

This tradition of providing the senators with more elaborate furnishings and using different upholstery colors to distinguish their seating from that of the representatives continued when the government moved to Washington. In 1807 Latrobe instructed Rea to acquire expensive red leather and Brussels carpeting for the chairs the Senators were to use when visiting the House chamber. Clay’s reference to the Senate’s “fine red chairs” and the House’s “plain democratic ones” indicated that this policy continued when the legislature met at the Brick Hotel. In 1817 Englishman Henry Fearon (b. ca. 1770) also commented on the discrepancy between the two sets of furnishings used in these temporary accommodations. He noted that the senators sat on “rich scarlet cushions” that contrasted starkly with the “common chairs” of the representatives whose chamber, decorated “in the Lancasterian taste,” was “marked by an inferiority to the senate, which is rather anti-republican.”[55]

With the assistance of Thomas Constantine’s cabinetmaking company, the House and Senate continued to use furniture to mark this divide when they returned to the Capitol in 1819. Neither legislative body shied away from purchasing elaborate carpets, curtains, and lighting devices, and the receipts for decorating the Capitol reflect a financial commitment by both groups to create attractive chambers (fig. 40). The obvious exception to this intent were the carved mahogany chairs and elegantly veneered desks ordered for the Senate, which evinced an awareness of and appreciation for refinement not found in the plain furniture of the House chamber. The divergent styles of the desks and chairs served as a visual reminder of the separation between these two legislative bodies.

Visitors to the Capitol understood that chairs with figured mahogany veneers, extensive carving, and morocco leather seats cost more than those with plain mahogany, turned elements, and horsehair. This language of value would have made a deep impression on contemporary observers, for furniture was used to convey status and an appreciation for current fashion in the private sphere as well. In the rehabilitated Capitol public perceptions of the general traits of the House and Senate embodied and reinforced the characteristics of their furniture. The “lack of order and general decorum in the House” compared unfavorably with the Senate, a “dignified and orderly assemblage, its members as a whole high in intellectual ability.” Most visitors were duly impressed by the grandeur of the Senate, and they lauded the “elegance of the chamber.” In 1832 Frances Trollope (1780–1863) lamented that the “extreme beauty of the [House] chamber...fitted up in so stately and sumptuous manner” was tarnished by men “sitting in the most unseemly attitudes, a large majority with their hats on, and nearly all spitting to an excess that decency forbids me to describe.” These uncouth representatives possessed well-built but unrefined chairs and writing tables that appeared to reflect their behavior.[56]

Hope could have not envisioned this contrast more perfectly. He adamantly maintained that man’s morals and outlook could be improved by the aesthetic success of his surroundings. According to the designer, chairs such as those used by the Senate were a contemporary rendition of classical elegance, meant to convey “all that real and all that ideal perfection, all that correctness and all that grace, which so essentially belonged to the best antique performances, and to those modern works that profess to retrace their various excellencies.” Hope would have argued that an American government endeavoring to imitate the success and grandeur of classical society could benefit by procuring furniture that alluded to antique fashions. In their robust massing, carving, and elaborate mahogany veneers, the Senate chairs appeared stately and had all the trappings of Roman power, authority, and sophistication. The red morocco leather covering their seats and backs was another fitting representation of this hierarchical elegance.[57]

The Senate desks are also noteworthy as declarations of personal space. In both the pre-fire chamber and their post-fire home in the Brick Hotel, most senators sat at two-person desks, but when they returned to the Capitol in 1819, each senator received his own desk, as had been the case in Philadelphia. There is great significance in this decision to give members of the upper body individual workspaces while the representatives continued to sit together at long tables. The forty-eight chairs and forty-eight desks provided by Constantine reinforced the idea of each senator’s individual power and independence. Conversely, legislators sitting collectively at large multiperson tables would have conveyed notions of democracy, equality, and interdependence. Such considerations may have contributed to the House being described as unruly and the Senate as more polished.[58]

Constantine’s method of marking the Senate chairs suggests that he understood the institutional hierarchy of the Congress. The representatives’ chairs have paper labels identical to the early one on the De Wolf pier table (fig. 5), whereas the Senate chairs have castors stamped “T. CONSTANTINE N. YORK” (fig. 41). No other American cabinetmaker is known to have used personalized castors to identify and advertise his work, and Constantine continued to do so for prominent public commissions. Due to the accelerated schedule of the Senate commission, Constantine likely turned to a local brass founder to produce the castors, which had to fit the particular orientation and shape of the legs.[59]

The Apex of a Brief Career

For Thomas Constantine, the federal government’s need to refurnish the Capitol came at a fortuitous time. The lucrative commissions to provide desks and chairs for the House and Senate arrived during a disastrous economic downturn. High prices for American foodstuffs and natural resources during the 1810s led to speculative investments in land and easy credit from state and federal banks. In 1819, however, the Bank of the United States sensed the growing instability of its financial standing and called in loans and foreclosed on mortgaged land. Its directors collected state banknotes and then demanded specie from those smaller institutions. Many banks could not meet their outstanding debts and were forced to close, sending a shock wave through financial establishments to all corners of the United States.

What began as the Panic of 1819 would ultimately turn into a prolonged depression in which the salability of American manufactures and agricultural products steadily fell. Cabinetmakers relied on credit to purchase lumber, veneers, and hardware yet at the same time needed to extend credit to their customers. With middle-class consumers and commodities merchants reeling, artisans had difficulty both paying their suppliers and collecting payments, not to mention the challenge of selling newly made furniture.

While many of his peers were drastically affected by this recession, Constantine survived largely on his spectacular earnings from the Capitol commissions. He did not receive any advances from the federal government on his work, which put him in grave jeopardy of financial failure, but the promise of a $27,000 paycheck and the privilege of furnishing the country’s most important public building must have been powerful incentives. Constantine stood to net at least $5,000 from furniture sales alone even if he did not profit from the sale of carpets, drapery, lamps, and stoves to the Senate, as claimed in his 1826 petition. This figure is quite impressive considering that the house and lot Constantine leased at 157 Fulton Street in New York were assessed at $6,000 in 1819.[60]

Constantine began the 1820s by adding new types of household goods to his cabinetmaking line. He strived to entice new patrons to his Fulton Street store and to develop new markets by purchasing licensing rights to recently patented furniture and by venturing into spring seating and mass-produced domestic wares. The financial windfall of the Capitol commissions may have prompted Constantine to expand his business, but his work for the House and Senate ultimately may have distracted him from the management of his daily affairs. If he neglected his local customer base, he probably lost a good deal of the commissioned and warehouse work that drove daily production. The inability to establish a solid network of patronage separated Constantine from successful contemporaries such as Phyfe and Allison.[61]

Constantine’s manufacturing facilities allowed him to focus less on commissioned work and more on mass production. His role changed from that of craft-oriented mechanic to merchant-manager, because broad oversight was required to manage a separate wareroom, manufactory, and turning business. Notices for “16 spring seat sofas” and “100 Patent Joint Bedsteads” in 1823 document a level of production that would have been unattainable before the Capitol commissions.[62]

In the early 1820s Constantine received commissions for a ceremonial chair and canopy for the North Carolina State House and altar furniture for New York City’s Christ Church (figs. 43, 44). Although these commissions affirmed his ability to produce powerful, symbolically charged furniture, neither job generated a significant amount of money for his firm. Retailing patent bedsteads and spring-seat furniture was not as profitable as Constantine had hoped, forcing him to close the Fulton Street store by the summer of 1824. On May 3, 1823, the New York Evening Post reported that T. Constantine & Co. intended to “reduce expenses so as to be able in future to dispose of their furniture of the best quality.”[63]

Constantine closed the manufactory on Greenwich Street in 1826 and abandoned the cabinetmaking trade altogether. For the next twenty-three years he operated mahogany yards in New York City, a sawmill for cutting veneers in Westchester County, and a hardwood brokerage in southwestern Michigan (fig. 45). Constantine’s involvement in the lumber market began in 1816, when he advertised “Veniers, Boards, Plank and Joist of 300 logs Mahogany . . . a great proportion of crotches and motled wood.” Although much of his trade may have been with local furniture makers, customs records indicate that he shipped mahogany and hardware to Savannah in 1825 and 1826. The profitability of such ventures may have enticed Constantine to change professions, particularly when his furniture business began to decline during the 1820s. He must have developed a keen eye for the quality of raw lumber during his years as a cabinetmaker. At the end of his career, Constantine served as a government-appointed inspector of mahogany for the port of New York. He died of a “short and severe illness” on October 20, 1849, at fifty-eight.[64]

A Compelling Legacy

The chairs and desks that T. Constantine & Co. made for the Capitol reflect the varying significance of aesthetics in early-nineteenth-century Washington. These objects also bear witness to the ambition and entrepreneurial spirit that allowed America to recover from the destruction caused by the War of 1812 and that defined the careers of many young craftsmen like Constantine. All forty-eight of T. Constantine & Co.’s Senate desks remain in use today, albeit extensively modified by the addition of bookshelves, supplementary writing boxes, and microphone stands. The desks now sit in the Senate chamber of Thomas U. Walter’s (1804–1887) 1859 addition to the Capitol (fig. 46), along with fifty-two similar desks commissioned for the senators of states that entered the Union after the admittance of Missouri in 1821 (fig. 47).[65]

Only four of Constantine’s Senate chairs are known, as senators have been allowed to take them on their retirement since the late nineteenth century. One chair descended in the family of Rhode Island Republican Jonathan Chace, who served in 1885–1889 (fig. 23), and another was passed down from Maine Republican Hannibal Hamlin (fig. 24), who served from 1857 to 1861 and 1869 to 1881. A third chair, formerly in the collection of Beauvoir, the Jefferson Davis Museum and Memorial Library in Biloxi, Mississippi, was destroyed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (fig. 48). Although the provenance of the latter chair is unclear, it may have been used by Davis until his resignation in 1861 and subsequently removed from the Capitol by California Democrat Milton Slocum Latham.[66]