Great chair, England, 1300–1400. Materials and dimensions not recorded. (Antiques 32, no. 3 [September 1937]: 112–13.) The leather covers are later additions and many of the small components are replacements.

Side view of the chair illustrated in fig. 1.

Rear view of the chair illustrated in fig. 1.

Diagram showing the seat rail construction of the chair illustrated in fig. 1. The seat boards are thick and do not have feathered edges.

Great chair, England, 1300–1400. Oak. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Dean and Chapter of Hereford Cathedral.)

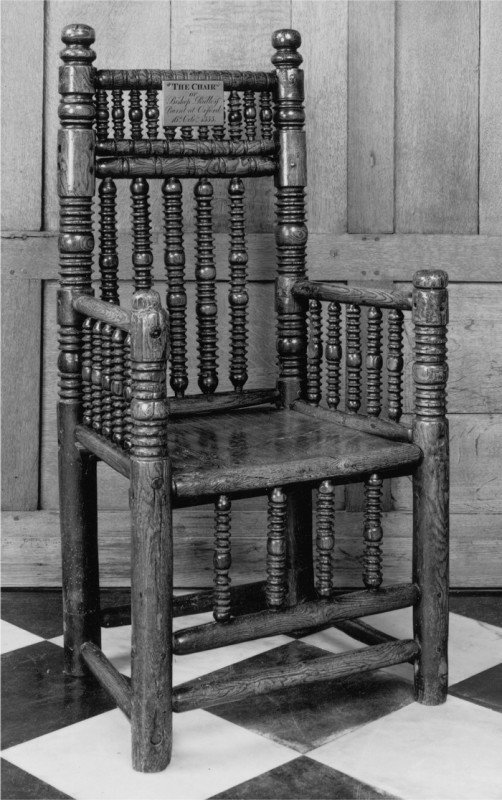

Great chair, probably London, 1540–1550. Elm. H. 46 1/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 18 5/8". (Courtesy, Pembroke College, Cambridge; photo, James Austin.) The rear feet are pieced, the lower back rail is replaced, the rear seat rail groove has split out, and two slats nailed underneath reinforce the seat boards. The seat boards are not held in the side seat rails. The front and rear seat rails are pegged, and all the mortises are through-bored. The crest rail originally had fifteen applied buttons.

Men Shoveling Chairs (Scupstoel), Circle of Rogier van der Weyden, Flemish, 1444–1450. Pen and brown ink over traces of black chalk. 1 13/16" x 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 [1975.1.848]. Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Diagram showing the placement of square and round tenons in the frame of a triangular stool.

Great chair, England or the Netherlands, 1500–1650. Possibly fruitwood and beech. H. 31", W. 24", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, National Trust, Northwest Region, Cumbria.)

Great chair, South Africa, eighteenth century. Possibly stinkwood. H. 32", W. 23 3/4", D. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, H. K. J. Roos.)

Great chair, South Africa, eighteenth-century. Possibly stinkwood. H. 31", W. 22 3/4", D. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, H. K. J. Roos.)

Great chair, England, 1600–1650. Ash and possibly elm or yew. H. 35", W. 23", D. 17 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert J. Bitondi.) The side stretcher nearest the viewer is pulled up at the rear to such an extent that it is not parallel to the seat rail above it.

Detail of the left front post of the chair illustrated in fig. 12. The small round tenon pierces the rectangular tenon and is back-wedged.

Detail of the left seat joint of the chair illustrated in fig. 12. The shoulders of the front seat rail are sawn on the bias to conform to the post. The seat board is extremely snug. On some chairs of this type, the corners of the seat board fit into a slight groove incised in the post.

Diagram showing the seat rail joint of a board-seated chair with intersecting round tenons.

Great chair, Wales, 1550–1660. Woods not recorded. H. 39", W. 26", D. 21". (Courtesy, Museum of Welsh Life, St. Fagan’s, Cardiff, Glamorgan; photo, Robert F. Trent.) The seat board is made in two pieces and the seat rails have a round tenon at one end and a rectangular tenon at the other.

Great chair, Wales, 1550–1650. Yew and oak. H. 38 1/8", W. 25 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Welsh Life, St. Fagan’s, Cardiff, Glamorgan; photo, Robert F. Trent.) The seat board is made in two pieces and the seat rails have a rectangular tenon at one end and a round tenon at the other. The shoulders of the rectangular tenons are cut on the bias to conform to the shape of the posts. Some of the applied finials and the left upper arm are replacements.

Great chair, Wales, 1550–1650. Elm and oak. H. 57 1/4", W. 28", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Welsh Life, St. Fagan’s, Cardiff, Glamorgan; photo, Robert F. Trent.) The seat board is made in two pieces and the seat rails have a large round tenon at one end and a small round tenon at the other. The arm joints and the entire back superstructure are extensively pinned. The turned buttons on the crest have round tenons that were shaved square before being forced into smaller, round mortises. The buttons are not pinned, which suggests that the crest rail retained considerable moisture at the time of manufacture and the maker expected the mortises to shrink around the tenons.

Great chair, Cornwall or Devon, England, 1550–1650. Ash. H. 45", W. 23 7/8", D. 26 1/2". (Courtesy, Church of St. Marnarch, Lanreath, Cornwall; photo, Robert F. Trent.) The seat is an incorrect replacement installed on top of the seat rails. The right seat rail is replaced.

Great chair, Wales, 1550–1650. Elm. H. 53 5/8", W. 33", D. 26 1/8". (Courtesy, Temple Newsam House, City of Leeds, Yorkshire; photo, Norman Taylor.)

Great chair, Wales, 1550–1650. Elm. H. 52 7/8", W. 31 3/4", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Welsh Life, St. Fagan’s, Cardiff, Glamorgan; photo, Robert F. Trent.) The upper and lower arm joints are pinned; the intermediate arms are not pinned. The left rear leg, seat rails, upper front stretcher, upper left arm, and seat board are replacements. The finials on the back posts are enlarged versions of the small, applied buttons on the top of the crest rail, and the footrest is a later addition.

Great chair, Wales, 1550–1650. Ash and oak. H. 44 7/8", W. 30 3/8", D. 22 3/8". (Private collection; photo, George Fistrovich.) This object is part of a large group of almost identical chairs, including an example acquired for the president of Harvard College in the mid-eighteenth century.

Great chair, Cornwall, England, 1550–1650. Ash. H. 41", W. 25 3/8", D. 19 3/8". (Courtesy, Church of St. Marnarch, Lanreath, Cornwall; photo, Robert F. Trent.) The seat boards are incorrect replacements installed atop the seat rails, and the finials are restored.

Great chair, probably Wethersfield, Connecticut, or New York City, 1650–1700. Ash and oak. H. 41 1/8", W. 26", D. 20". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut; photo, Robert J. Bitondi.)

Side view of the chair illustrated in fig. 24, showing the angle at which the back is set in the low structural bar.

Great chair, New York City, 1650–1700. Ash and oak. H. 39 1/2", W. 24", D. 17". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1941 [41.111]; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The seat board is a modern replacement.

Great chair, Connecticut or New York, 1650–1700. Maple and ash. H. 43 1/2", W. 23" (front) and 17" (rear), D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Great chair, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1640–1660. Ash and pine. H. 45", W. 24 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Pilgrim Hall, gift of the heirs of William Hedge and Catherine Russell, 1953, phm 1054; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The seat board and upper back rail are replaced, the front posts may have had pommels, and the feet have been shortened about five inches.

Great chair, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1640–1660. Ash. H. 45", W. 24", D. 18". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Pilgrim Hall, gift of Daniel Brewster, 1838, PHM 942; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Fragments of the pommels remain on the front posts. The top back rail, seat board, lower front stretcher, and five spindles are missing.

Great chair, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1640–1660. Maple and ash. H. 39", W. 26", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Pilgrim Hall, Museum purchase from Roger Bacon, 1967; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The posts were replaced in the eighteenth century and the spindles replaced at a later date. Tradition maintains that the spindles under the arms came from pews from the 1682 meetinghouse in Hingham, Massachusetts.

Great chair, probably London or Cambridge, England, 1510–1514. Ash and pine. H. 49", W. 24 5/8", D. 17". (Courtesy, Queens' College, Cambridge; photo, Reeve Photography.) The seat rails have a large rectangular tenon at one end and a small round tenon at the other. The upper back rail is an addition, the front stretcher is replaced, the feet have been pieced out, and the rear stretcher and six spindles under the front seat rail are missing.

Great chair, England, 1550–1650. Ash and chestnut. H. 43 1/8", W. 24 1/2", D. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert J. Bitondi.) The seat board is replaced, the front posts may have had pommels, and the tip of the right finial is missing. The frame never had a lower rear stretcher. The seat construction is the rectangular tenon–small round tenon type.

Side view of the chair illustrated in fig. 32, showing the rake of the frame.

Side chair, the Netherlands or southeastern England, 1600–1650. Cherry. H. 30 1/2", W. 17 1/2", D. 14 7/8". (Courtesy, Antiquarian & Landmarks Society, Hartford, Connecticut; photo, Robert J. Bitondi.) The seat board and left stretcher are replaced.

Detail of a spindle on the chair illustrated in fig. 34.

Detail of the left finial of the chair illustrated in fig. 34.

Great chair, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Maple and ash. H. 45 3/4", W. 24", D. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair reputedly belonged to William Brewster’s grandson, Benjamin Brewster (1633–1710), who moved from Plymouth to New London, Connecticut, in 1653 and then to Norwich, Connecticut, by 1662.

Great chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1640–1680. Ash and oak. H. 44 3/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 1951 [51.12.2]; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended in the Tufts family of Medford, Massachusetts. The seat board and pommels are modern replacements.

Great chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1650–1690. Ash and oak. H. 43 1/2", W. 24", D. 17 1/8". (Courtesy, Roxbury Latin School, Unitarian Universalist Church in America; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Rev. Thaddeus Mason Harris (1768–1842) acquired this chair from a Roxbury, Massachusetts, family and gave it to the First Church in Dorchester, Massachusetts. The chair was subsequently transferred to the Unitarian Universalist Church in America and is currently at the Roxbury Latin School. The top back rail is replaced, and the posts are pieced out.

Great chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Ash, maple, and oak. H. 41", W. 21 1/2", D. 15 1/16". (Courtesy, Historic New England, gift of Mary Thacher; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The rear legs are pieced out below the seat, the spindles beneath the arms and the finials are replaced, and the front posts may be replaced.

Child’s high chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Maple and ash. H. 38 5/8", W. 18 1/4", D. 14 5/8". (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society, gift of Mrs. Hannah Mather Crocker.) The seat board and a footboard are missing, the center front spindle is a replacement, and the top back rail may be replaced.

Child’s high chair, Virginia, 1670–1710. Black walnut. H. 36 1/2", W. 14 1/4", D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.) This chair may have belonged to Hancock Lee (1653–1709) of Virginia. The seat board, footboard, and seat board are missing. Both right stretchers, both rear stretchers, both back spindles, and the lower back rail are replacements.

Great chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Maple and ash. H. 41 3/4", W. 24", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of Charles Hitchcock Tyler.) The left back spindle and the front two inches of the seat are replaced, and the posts are pieced out at the bottom.

Only twelve American board-seated turned chairs made before 1720 are known. The term “board-seated” refers to a thin, planed board, or panel, with feathered edges that engage grooves plowed in the inner edges of a chair’s seat rungs or “lists.” Sometimes the board is held in the front and rear seat rungs only, but in most surviving chairs, the seat board is held in all four rungs. The seat board is thick enough to be fairly rigid but thin enough to flex slightly under the sitter’s weight; usually the optimum thickness at the center is about half an inch. In view of the fact that hundreds of early American turned chairs with vegetable fiber seats are known, it would seem that board-seated versions were infrequently made, and that special skills were required to produce them. This article will examine the board-seated genre within the context of traditional chair making and present theories about the European origins of various examples.[1]

Turned chairs with board seats occupied an anomalous position in the woodworking hierarchy. Although they may have been considered equal in status to simple joined chairs, most of the American turned chairs with board seats appear to have been preserved because of their historical associations rather than their aesthetics. Of the twelve known examples, three came down in the families of Pilgrim leaders, two belonged to influential seventeenth-century clerics (Rev. John Eliot [1604–1690] of Roxbury, Massachusetts, the minister who translated the Bible into the Algonquian language, and Rev. Cotton Mather [1662–1728] of Boston), and one reputedly descended in the prominent Fauntleroy and Lee families of Virginia.[2]

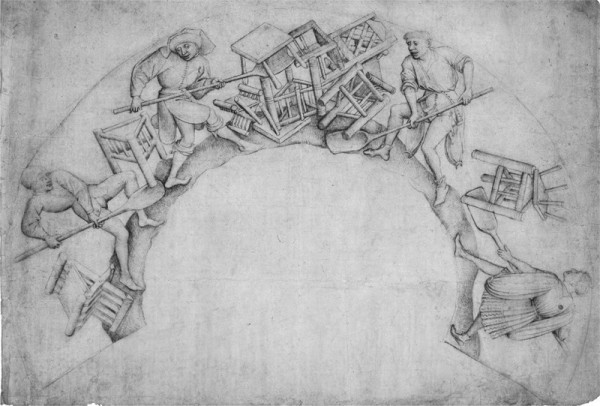

Board-seated chairs raise additional interpretative quandaries. Although they constitute a subset of turned chairs, the structural peculiarities of certain board-seated variants often deviate from accepted notions of traditional post-and-rung chair construction. Within the cohort of traditional seating, post-and-rung chairs included seating with shaved components (otherwise known as plain chairs) and seating with turned components. Both of these variants feature socket joints assembled by driving dry tenons into wet mortises. Before 1500 some chairs combined joinery, turning, shaved work, and latticework of the sort associated with casement frames, as seen in the drawing Men Shoveling Chairs (fig. 7). Board seats, therefore, may be a vestigial structure within the post-and-rung chair tradition, dating from a period when the boundaries between seating types were blurred.[3]

Early British Chairs

British woodworkers had produced board-seated turned chairs centuries before the first colonists settled in North America. The chair illustrated in figures 1–3 probably dates as early as the fourteenth century, having reputedly descended in the family of Scottish military leader William Wallace (d. 1305). The post diameters are large, the frame has suffered losses due to insect infestation, and some parts have been replaced. The side view (fig. 2) shows that the lowest surviving side rail into which the original plain spindles fit was not on the same level as the front and rear seat rails. While most of the spindles visible in the rear view (fig. 3) are replacements, they indicate that some arrangement of turnings was present in the back. The most important observation that can be gleaned from these images is that the seat boards were secured only in the front and rear seat rails and were, therefore, probably thick and inflexible (fig. 4).[4]

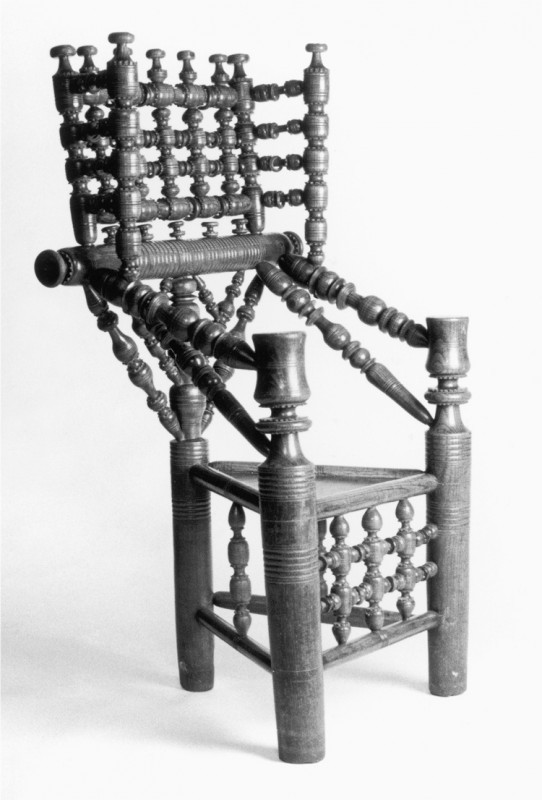

Wallace’s chair strongly resembles a coeval English example referred to as “King Stephen’s throne” (fig. 5). King Stephen reigned from 1135 to 1154, but most scholars date the chair 1300 to 1400. The most striking thing about this object is that it appears metallic. With their straight passages and small bands, the turned parts resemble cast metal tubes connected by rings or junctions. This was probably the maker’s intent, because the prototypes for such chairs were bronze or ebony-and-ivory thrones, typically assembled from many small parts. According to some nineteenth-century antiquarians, “King Stephen’s throne” retained traces of gilding and red paint, a color possibly intended to suggest polished bronze.[5]

All the principal joints of the chair illustrated in figure 5 are through-drilled. The board seat is composed of two heavy oak planks held in grooves in the front and rear seat rails. Neither of the side rails is at the same level as the seat boards. Surprisingly, the front and rear seat rails lack rectangular tenons, which would have prevented those rails from rotating in their mortises and releasing the seat boards. The maker may have felt that the thick seat boards were set deep enough in their grooves to resist rotation. That could explain why he apparently neglected to use trunnels (wooden pegs) to secure the seat rungs in their mortises.[6]

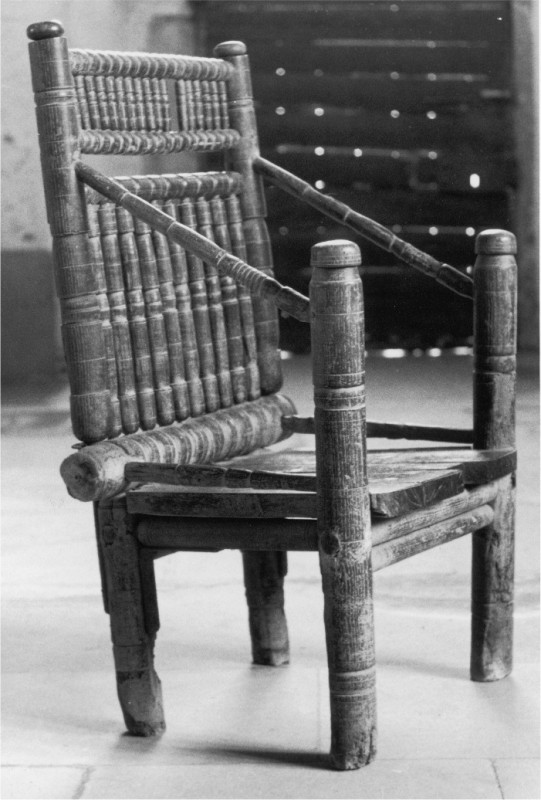

The chairs illustrated in figures 1–5 are important in understanding the chronology and development of board-seated furniture. Because they differ from turned seating depicted in Netherlandish paintings from the 1400s, the William Wallace, King Stephen, and associated chairs may represent index artifacts for a peculiarly English chair-making tradition. The “Bishop Ridley chair” at Pembroke College, Cambridge (fig. 6), appears to be in this same line of development. Nicholas Ridley (ca. 1500–1555) was a Reformation cleric allied with the radical Protestants Thomas Cranmer, archbishop of Canterbury, and Hugh Latimer, bishop of Worcester.[7]

Like King Stephen’s throne, the Ripley chair has a board seat held in the front and rear seat rails and through-tenoned horizontal members, some of which are back-wedged. Accepting the chair as dating from the bishop’s lifetime is somewhat problematic because of the reels and intermittent spherical turnings. This style of turning usually is thought to date from the 1660s, but the heavy finials and old-fashioned seat construction tend to support a sixteenth-century date.[8]

Early Dutch Chairs

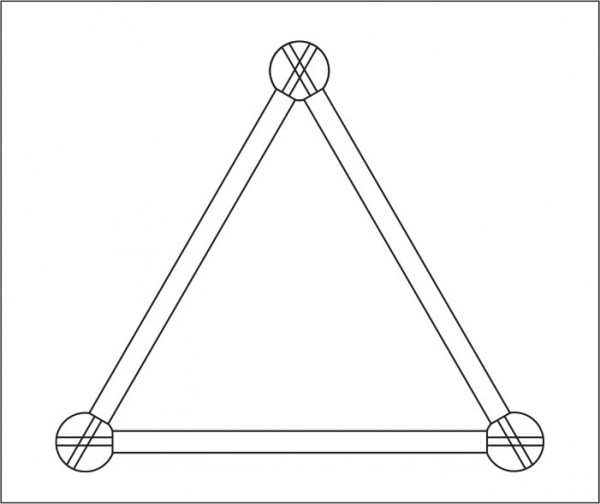

Stools with a different type of board-seat construction are depicted in the fifteenth-century Netherlandish drawing Men Shoveling Chairs (Scupstoel) (fig. 7). This allegory of social unrest jumbles together chairs reserved for the elite with peasants’ stools. Among the seating forms shown are stools with plank seats and stake feet, folding stools of the sort associated with church dignitaries, and a chair with shaved posts, a rush seat, and a joined back in-filled with latticework. The most important objects represented in the drawing are three-post, turned stools with board seats. To trap the seat board on all three sides, the rails of three-post stools had to be set at the same level. This created a problem, because the tenons entering each post intersected with each other. Makers overcame this problem by using a round tenon at one end of each seat rail and a square tenon at the other end (fig. 8). On each post the smaller round tenon passed through the larger rectangular tenon, creating an interlocking joint. Usually, the round tenons were pinned to prevent them from withdrawing from their mortises. In addition to creating a stronger joint, the rectangular tenons prevented the seat rails from rotating under the weight of the sitter and causing the seat board to slip out of place.

To construct stools of this type, makers had to be precise when chopping and drilling their mortises. Assembling the frame also required considerable dexterity, since the maker had to rotate the frame while hammering each joint in succession. If any tenon was driven much farther in than the other two, the entire structure would bind or one of the posts would split under the stress.

Although three-posted stools often appear in Netherlandish art, furniture historians have either ignored these seating forms or posited that they were the antecedents of chairs. Under that “evolutionary” model, the rear post of stools rose higher over time, eventually providing a backrest for the sitter. It is more likely that fully developed stools and chairs with extended back posts were made simultaneously. The chair shown in figure 9 has a horizontal crest curved to conform to the sitter’s back and two diagonal struts that function as braces. On other examples, the crest has a deeper curve and extends farther forward to provide cantilevered armrests. The three-post format had advantages because it was stable on uneven floors.[9]

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, armchairs were among the most comfortable and prestigious seating forms. Some provision for arms is seen in two eighteenth-century South African chairs based on Netherlandish examples made two centuries earlier (figs. 10, 11). The rear posts of these derivatives have paddlelike crests with diagonal struts, and the arms are continuous, bent slats that are pinned to the rear post and tenoned into the front posts. The abstract turnings of the posts, consisting of long, inswept collars, are similar to those on the chair illustrated in figure 9. That chair represents another variant within the tradition, having a broader crest, crooked struts worked with a draw shave, and turned arms. All these chairs (figs. 9-11) have blind joints at the seat rails, presumably with a rectangular tenon at one end of each seat rail and a round tenon at the other end.

Another early type of board-seated construction occurs on a chair with a straight turned crest braced with diagonal struts and turned arms that fall on a diagonal to extensions of the two front posts (fig. 12). This object displays a technically sophisticated version of the intersecting tenon system (figs. 13-15). The shoulders of the rectangular tenons are sawn at an angle to conform to the shape of the posts, and the round tenons are back-wedged, an alternative to pinning. The shaped shoulders also function as a redundant antirotation device. This precise execution and overconstruction is reminiscent of Germanic work of the period. After all, rectangular tenons without conforming shoulders would have held as well, and the seat board did not have to fit so tightly in the corners.

In this chair, the complexities inherent in assembling a three-post stool were multiplied. The maker had to work his way around the frame, gradually driving together three intersecting joints without causing any to bind while simultaneously joining the arms to the crest rail and the two front posts. Exactly how he accomplished this task is unclear, but the long, tapered turnings at the front of the arms suggest that the maker began by assembling the entire back with its crest rail and diagonal struts (no mean feat in and of itself). He then could have driven the rear tenons of the arms completely into the crest rail and proceeded to assemble the seat frame and stretchers, while forcing the front tenons of the arms into the posts.

Plotting the locations of the stretchers was another problem. The maker of the chair illustrated in figure 12 set them at different heights. This provided structural integrity but denied bilateral symmetry. While both side stretchers enter their respective front posts at about the same level, they enter the rear post one above the other.

The Welsh Tradition

Most of the British board-seated, turned chairs that survive have histories of ownership in Wales. Some have seat frames constructed with rectangular tenons intersected by round tenons, whereas others have seat rails with intersecting large and small round tenons (fig. 15). Both types of joints appear in chairs that are virtually identical, so no chronological or developmental priority may be assigned to either variant.

The chairs illustrated in figures 16 and 17 are relatively plain, having straight rear posts and heavy turned horizontal crest rails. Both have two arms set at different angles on each side and spindles between the seat rails and the stretchers. An important stylistic and structural detail is the use of turned ledges on the rear post, which serve as seats for the diagonal struts supporting the crest of each chair. The vigorous turnings, including the heavy urns on the front posts, are squarely in the mannerist design tradition, and it is difficult to believe that such objects could have been made in Wales much before 1560. These chairs also have applied buttons of various forms and punchwork in some moldings. They continue the practice of placing the three stretchers at different levels, without reference to bilateral symmetry. These chairs represent a standard model. Other versions feature complex superstructures that were labor-intensive, expensive options. The most elaborate chairs were preserved as relics of departed patriarchs and matriarchs.

The chair illustrated in figure 18 has a history of ownership in Ty’n-y-cymer, Glamorganshire. Its understructure is not all that different from those of the previous Welsh examples, but its crest is ornamented with a superimposed cage of interlocked posts, rails, and spindles. Connected to this cage are two lateral structures that resemble the wings or cheeks of early-eighteenth-century easy chairs. This elaborate framework may have been draped in winter. Features not previously encountered include gouge carving on the flanges of turnings and free rings made from the same piece of wood as the spindles they surround. The multiple bands on the posts and the crest rail appear on some of the chairs in Men Shoveling Chairs (fig. 7), suggesting a connection between this Welsh chair-making school and the late medieval Netherlandish tradition that preceded it; however, many of the other turnings are well-defined renaissance forms.

The extraordinarily complex fabrication and assembly problems posed by these Welsh chairs suggest that they may be earlier than some related stools. Although the chairs may have provided greater comfort, their backs forced the user to sit upright, leaving little room for relaxation. As long as the principal support for the back rail was an extension of the rear leg, this posture was difficult to avoid.

To create layback, makers began using a large horizontal rail immediately above the seat. This allowed them to set the back posts at an angle, providing additional comfort for the sitter. As the chair illustrated in figure 19 suggests, this design often made construction more complex. The maker of this example probably began by assembling the seat frame using the interlocking round-tenon system described above. Then he began driving the joints connecting the lower arms to the front posts and large horizontal rail, the diagonal struts to the low rear post and large horizontal rail, and the large horizontal rail to the low rear posts. The maker performed this work gradually and sequentially to keep the joints from binding. Having completed the undercarriage, he could begin installing the back. He drove the arms into the upper back posts, inserted the big back spindles into the frame, maneuvered the back posts and spindles into their mortises in the large horizontal rail, and forced the front tenons of the arms into their mortises in the front posts. The high degree of skill required to bore the mortises of this chair accurately and to assemble its frame attest to the sophistication of the board-seat design tradition.[10]

The diagonal struts supporting the large crest rail of the armchair illustrated in figure 18 feature bilaterally symmetrical balusters with a thin reel at the waist, a turning sequence repeated on the lower back pillars of a related chair (fig. 20). Although the chair illustrated in figure 20 has two horizontal rails above the seat, its back is framed with a series of medium-weight spindles rather than two large outer posts. The two rails are nearly identical in size and diameter, and the superstructure with cheeks or wings is higher relative to the seat and the back than that of the chair in figure 18. The maker chose to retain a primary and secondary pair of arms, but he set one pair between the structural rail and the front posts and the other between the crest rail and the front posts. Consequently, both pairs of arms are set at the same angle. Embellishments on the chair illustrated in figure 20 include free rings, applied buttons, and gougework. With its pronounced urns and balusters, the turned ornament of this example has stronger renaissance overtones than that of the chair shown in figure 18.[11]

Three-post chairs with high superstructures tend to tip over if the sitter shifts too much weight to either side. At some point, makers introduced a four-post plan. A striking example of the latter form has a history of ownership in Tregib, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire (fig. 21), and appears to be from the same shop tradition that produced several three-post chairs (fig. 22) including one acquired in the 1750s for the president of Harvard University. Like all of the seating in this group, the chair illustrated in figure 21 has little layback despite having a low structural rail mounted just above the seat. The front posts of these chairs also lack pommels, or handgrips, a feature found on many other examples of board-seat furniture. The chair illustrated in figure 21 deviates from the group in having a back framed with heavy outer posts rather than several medium-size spindles. The only renaissance turnings are the heavy urns on the front posts and a few minor ball-and-reel sequences.[12]

The simple but distinctive great chair illustrated in figure 23 was probably made for the church of St. Marnarch in Lanreath, Cornwall. Unlike most turned great chairs, this example has posts braced by stretchers set just below the seat rails rather than near the floor. The maker’s use of extremely heavy stock for the posts may have been dictated by a concern for stability. The turnings of this chair relate directly to those on two similar American examples. Pertinent elements include the slightly indented ball turning on the front and rear posts and a barrel-like turning on the back spindles with indented ends and a central incised band.[13]

The Board-Seat Tradition in America

The American chairs that relate most closely to the St. Marnarch example represent the work of two different makers. One descended in the Foote family of Wethersfield, Connecticut (figs. 24, 25), and the other reputedly belonged to Jacob Strycker, a German who lived on western Long Island near New York (fig. 26). The earliest member of the Foote family was a turner named Nathaniel (ca. 1593–1644).[14]

At this time, it is impossible to determine if the makers of the Foote and Strycker chairs trained in the same regional tradition that produced the St. Marnarch chair and other related board-seat forms. The backs of the American examples have greater layback (fig. 25) than their British antecedents, and the turnings on the Foote and Strycker chairs are more conservative than those on the St. Marnarch chair, although still based almost entirely in the renaissance tradition.

A straight-post chair in the same style as the Foote and Strycker examples suggests how this board-seated tradition may have evolved in America (fig. 27). Although it has turned ornament similar to that on the preceding examples (figs. 24, 26), the chair illustrated in figure 27 does not have a horizontal back rail set just above the seat. This suggests that the same shops that made chairs with such rails also produced seating without them.[15]

The Plymouth Tradition

The most widely published American board-seat chairs were made in Plymouth, Massachusetts. One reputedly belonged to William Bradford (1589/90–1657) (fig. 28), one to William Brewster (1567–1644) (fig. 29), and one to Myles Standish (1584–1656) (fig. 30). Skeptics have decried these histories for years, partly because other Pilgrim provenances have proven specious and partly because of the existence of replicas made over the years to satisfy the cult of ancestor worship surrounding the Pilgrims. Many Pilgrim descendants owned or own artifacts that reputedly arrived on the Mayflower, but most of these objects were first owned by later generations of the families in question. All of the chairs in the Plymouth group were once considered part of that ship’s cargo, but their American woods refute that theory. The chairs may, however, represent the work of an immigrant craftsman. If that is true, then their histories of ownership by immigrant Pilgrim patriarchs are probably correct.

Several British and Netherlandish chairs can be interpreted as antecedents or cognates for the Bradford, Brewster, and Standish seating. The woodworking tradition encompassing the Plymouth chairs probably emanated from London, where Dutch influence was strong. The Ridley chair (fig. 6) suggests that turned chairs with board seats were being made in that city by the mid-1550s. A chair that reputedly belonged to Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus (ca. 1466–1536) supports that theory (fig. 31). He visited England repeatedly between 1499 and 1517 and was often the guest of Sir Thomas More (1478–1535). Presumably Erasmus obtained the chair during his unhappy residence as a lecturer at Cambridge from 1510 to 1514, or perhaps earlier during one of his visits at More’s house near London. The Erasmus chair is one of the few English four-post examples without a low structural back rail that can be associated with southeastern England.[16]

Another English chair has features rarely seen outside the Plymouth group (fig. 32). Its front and back posts are canted, but all of its horizontal components remain parallel to the floor (fig. 33). This design allowed the maker to produce layback without using a low structural back rail, but it did not provide the same level of comfort. The muscles of a sitter’s back and legs cannot relax as long as the seat remains level. A cushion at the front may have alleviated some tension by slightly elevating the sitter’s legs. The vasiform turning vocabulary of this chair is closely related to that of the Plymouth examples and has almost no medieval antecedents.

Perhaps the most important cognate for the Plymouth group is a small side chair likely of Netherlandish origin or made by a Dutch turner who resided in London or another Channel port (fig. 34). Turned side chairs rarely survive, and those with board seats are exceptionally rare. The turnings on the chair illustrated in figure 34 are far more detailed and refined in concept and execution than those on the Plymouth chairs (figs. 28-30). The deeply incised accents and sharp-edged, elegant flanges (figs. 35, 36) are indices of high-quality work, where the turner was pushing his design to the limits of the material. Many of the thinner edges have chipped off, possibly because the cherry became brittle with age—a characteristic of most fruitwoods. Dutch turners often made chairs of cherry, with the intention of painting them black to resemble ebony.[17]

The William Bradford chair (fig. 28) is the most intact example in the Plymouth group, and it has subtle refinements that are not immediately evident. The side rails of the seat are angled, dropping about one-half inch from front to back, but the front and rear posts are upright. When combined with the use of a cushion, this feature would have made the chair more comfortable than a comparable example with seat rails oriented parallel to the floor. The Bradford chair maker turned long tapered stops on the ends of his vasiform spindles so he could trim and fit them in a seamless fashion and turned the spindles in batches of five different heights based on their intended location in the frame. The Brewster and Standish chairs (figs. 29, 30) originally looked very much like the Bradford example. The latter chair is the only one retaining its original upper turned back rail.

All of the board-seated chairs in the Plymouth group have interlocking rectangular and round tenons where the seat rails join each post. The tops and bottoms of the mortises are rounded, suggesting that the maker used a brace fitted with a piercer to bore holes at each end and a mortising chisel to chop out the waste between. After turning the seat rails, he sawed the cheeks of the tenons to make the upper and lower edges conform, approximately, to the bored ends of the mortises. The maker of the English chair illustrated in figure 32 followed the same practice.

All of the Plymouth chairs appear to be from the same shop tradition, if not by the same hand. The turnings display minor variations, but that is to be expected in early seating of this caliber and complexity. The spindle profiles of the Bradford and Brewster chairs are virtually identical, a fact somewhat obscured by turnings on the latter example, which were shaved flat on their front faces at a later date.

The worn front stretcher of the Bradford chair provides evidence that all of the Plymouth examples were assembled using wet-and-dry construction. Both ends of the stretcher are almost perfect half-sections of the tenons secured in the mortises. The tenons have compression marks that match the spoon-bit kerfs of their mortises. These marks occurred as the wet posts dried, shrinking around the tenons. The tenons were probably dry and slightly oversized at the time of assembly.

A slat-back armchair (fig. 37) recently discovered by furniture scholar Donald P. White III is the only other example from this shop tradition, which is surprising considering the large number of surviving turned chairs made by Ephriam Tinkham (1649–1713) of nearby Middleborough. The slat-back armchair descended in the Brewster family of Plymouth and New London County, Connecticut, until the late eighteenth century, when a member of the Roach family of New London County acquired the piece. Not only does the slat-back chair have finials similar to those on the Bradford and Brewster examples, but it also retains its abbreviated pommels. The pommels on the Brewster chair are too fragmentary to determine if they resembled those on the slat-back example.[18]

The Boston Tradition

A chair with urn-and-flame finials (fig. 38) that match those on many other examples of Boston seating serves as an index for understanding the board-seat tradition in that city. This imposing object descended in the Tufts family of Medford, Massachusetts, about five miles northeast of Boston. One of the earliest turners active in Boston was Thomas Edsall (1588–1676), a London-trained craftsman who immigrated in 1635. Given his dominance of the turning trade over the following forty years, he may have introduced many of the ornamental details found on later Boston seating.[19]

The Tufts chair is obviously the product of a sophisticated, established tradition. Although its turnings differ from those of the Brewster, Bradford, and Standish chairs, the construction of the Tufts example shares several details with the Plymouth group. The maker turned his spindles in different heights, so that the proportions of the frame could be adjusted, and set the side rails of the seat at an angle to produce a slight fall from front to back.

A related Boston chair (fig. 39) reputedly belonged to Rev. John Eliot (1603–1690), the minister of the church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, who translated the Bible and other religious texts into the Algonquian language. Like the Tufts chair, Eliot’s example has seat rail joints wherein a rectangular tenon is pierced by a round tenon, a board seat set in grooves on all four sides, and built-in seat fall. Despite these structural affinities, the Eliot chair is clearly by a different maker. It has two upper crest rails and only one stretcher at each side. The somewhat straight-sided turnings of the Eliot chair are repeated on a fragmentary example by the same maker (fig. 40).[20]

A high chair (fig. 41) that reputedly belonged to Rev. Increase Mather (1639–1723) of Boston also appears to be a product of that city’s board-seat tradition. The seat board is missing, but the rails have grooves cut on the inside edges and join the posts in much the same manner as those on the Tufts and Eliot chairs (figs. 38, 39). Some question exists about the age of the top back rail, which is loose in its mortises. The long, tapered posts and spindles, accented only by fine score lines, seem austere, but the forms may have been dictated by considerations of hygiene. Apparently this battered or pylon format was common in high chairs. A similar design can be observed in the only known southern chair with a board seat (fig. 42).

A board-seated great chair associated with Rev. James Keith (1643–1719) of Bridgewater in Plymouth County (fig. 43) may have been made in Boston, but it has no known cognates. At first glance, the finials appear to be related to those of the Plymouth group, but the turnings differ in several details. The Keith chair may date from the early eighteenth century and is, perhaps, the latest American example in the board-seat tradition.

The dating, technology, and stylistic progression of board-seated turned chairs is not entirely secure and requires far more research in European sources. Nevertheless, it is clear that the twelve American examples that survive have an ancient lineage. They may seem forbidding and cagelike to modern observers, but in their time, these chairs were regarded as thronelike enclosures that dignified their sitters and alluded to a tradition reaching back to the Assyrians if not the Egyptians.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Pauline Agius, James Austin, Peggy Baker, Gerry and Randy Bennett, Robert J. Bitondi, Kerry P. Brennan, Allan Breed, Rosalind Caird, Nancy Carlisle, Bill Cotton, Gerry Cotton, Richard Dearlove, J. Donovan, Peter Follansbee, the late Benno Forman, the late Christopher Gilbert, Tara Gleason, Donald Hare, Frank Kravic, Sandra Lackenby, Joshua Lane, Beverly Johnson Lucas, Richard C. Malley, Eddy Nicholson, Lionel Reynolds, Violet Riegel, Dr. Richard D. Ryder, Adrienne Sage, Erin Schleigh, Rev. L. J. Smith, Robert Blair St. George, Frances Gruber Stafford, Susan Stubbs, Michael Taviner, Roy Thompson, the Van Horne family, Donald P. White III, Sioned Williams, and Philip Zea.

For more on board-seated chairs, see Robert Blair St. George, “New England Turned Chairs of the Seventeenth Century: A Preliminary Survey,” seminar paper, Winterthur Program in Early American Culture, 1978 (manuscript in the authors’ possession); Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988), pp. 67–69; Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1979), pp. 87–103; Robert F. Trent, “Wet and Dry: A Preview of the Great Turned Chairs Round-Up,” Western Reserve Antiques Show 13 (1988): 56–59; and Robert F. Trent, “The Board-Seated Turned Chairs Project,” Regional Furniture 4 (1990): 42–48.

The Brewster and Standish chairs have been at Pilgrim Hall since the the mid-nineteenth century. For the history of the Bradford chair, see Helen Comstock, “The Bradford and Churchill Chairs,” Antiques 58, no. 5 (November 1955): 151. For the history of the Eliot chair, see The Memorial History of Boston, edited by Justin Winsor (Boston: James R. E. Osgood & Co., 1880), p. 415. The history of the Mather chair is published in Horace E. Mather, Lineage of Rev. Richard Mather (Hartford, Conn.: privately printed, 1890), p. 25. For more on the Lee chair, see Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry Abrams for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997), pp. 57–59

For more on the construction of post-and-rung using wet and dry components, see John D. Alexander Jr., Make a Chair from a Tree: An Introduction to Working Green Wood, rev. and enl. ed. (1978; Mendham, N.J.: Astragal Press, 1994). DVDs of this book were issued in 1999 and 2006.

Netherlandish turned seating had a powerful influence on British chair-making traditions. Because few early chairs with original histories of ownership are in Dutch museums, much of the information about Netherlandish turned seating comes from period genre painting and prints. While the authors have speculated on the origins of the European chairs illustrated in this article, much more research is required to separate British and Dutch work with any degree of certainty. Many surviving board-seat chairs are in Wales and Cornwall, and some scholars have assumed that such examples were confined to the so-called Celtic Fringe. This article attributes several chairs to London, and the inference is strong that board-seat traditions originated in metropolitan centers in the Low Countries and in English ports, not in regional or folk sources.

For the history of thrones in England, see Clare Graham, Ceremonial and Commemorative Chairs in Great Britain (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 1994). Green paint may have been used to simulate patinated bronze, white paint to simulate ivory, and black paint to simulate ebony.

For more on King Stephen’s throne, see Penelope Eames, ”Furniture in England, France, and the Netherlands from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Century,” in Furniture History 13 (1977): 192–94, pls. 54, 55; Chinnery, Oak Furniture, pp. 98–101; Julia W. Torrey, “Ancestors of the Turned Chair,” Antiques 32, no. 3 (September 1937): 120–21; and Richard D. Ryder, “Four-Legged Turned Chairs,” Connoisseur 191, no. 767 (January 1976): 48.

For Ridley’s biography, see The Dictionary of National Biography, edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee, 22 vols. (London: Oxford University Press, 1937–1938), 16: 1172–76.

A descendant donated Ridley’s chair to Pembroke College in 1928. The Ridley chair is illustrated and discussed in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge, 2 vols. (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1959), 1: pl. 44, 2: pl. 154.

For more on English turned chairs made before 1700, see Chinnery, Oak Furniture, pp. 87–104; Richard D. Ryder, “Three-Legged Turned Chairs,” Connoisseur 190, no. 766 (December 1975): 242–47, and Ryder, “Four-Legged Turned Chairs,” pp. 44–49. Almost all other surveys of English seating are concerned with regional traditions that evolved during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Cross-sectional measurement of the components of many turned chairs indicates that makers relied on shrinkage to secure their joints. In general, components with mortises were green (wet) and those with tenons were seasoned (dry). Pins were required to construct chairs as complicated as the example illustrated in figure 18. On most seating of this genre, all of the joints on the low structural rail of the back and the tenons of primary and secondary arms are pinned.

Christopher Gilbert, Furniture at Temple Newsam House and Lotherton Hall, 3 vols. (Leeds: Leeds Art Collections Fund and W. S. Maney and Sons, 1998), 3: 576–78. The front seat rail of the chair illustrated in figure 20 has a large round tenon at each end, rather than the more typical arrangement featuring a large tenon at one end and a small tenon at the other. The small, round tenons of the side rails pierce and lock the front ones. This tenon arrangement enabled the maker to drive the entire rear of the chair, including both pairs of arms, onto the front frame at once instead of assembling the seat frame, driving in the low structural rail and lower arms, and then driving in the crest rail and upper arms. It is remarkable that the former method was not used more often.

The Harvard president’s chair has been published many times, notably in New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century, edited by Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Robert F. Trent, 3 vols. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982), 3: 511–12. Related chairs are at the Museum of Welsh Life, St. Fagan’s, Cardiff, England; at Bunratty Castle, County Clare, Ireland; and in several private collections.

One reason for thinking that this chair has always been in the church is the presence of a copy that may date from the eighteenth century. While many nineteenth-century copies of such chairs are known, this replica reflects traditional workmanship.

The provenance of the Foote chair is discussed in several articles cited above in n. 1. The Strycker chair is illustrated in Helen Comstock, American Furniture: Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Century Styles (New York: Viking Press, 1962), pp. 30–31. This chair will also appear in Frances Gruber Safford, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 1, Early Colonial Period: The Seventeenth-Century and William and Mary Styles (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, forthcoming).

The Foote chair has been used as a prototype for several fakes. See Wallace Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, 1620–1720 (Framingham, Mass.: Old America Co., 1921), pp. 190, 205.

Victor Chinnery published a chair with a history of use by the president of the Placemen at the London City Cornmeter’s Office, but the authors are not certain that the piece was made in England (Chinnery, Oak Furniture, p. 99). The Erasmus chair is illustrated in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge, 1: pl. 44, 2: pl. 224.

This chair is illustrated in Sara Emerson Rolleston, Historic Houses and Interiors in Southern Connecticut (New York: Hastings House, 1976), p. 35. A walnut fake modeled on the Dutch chair and dating ca. 1950 is in the collection of Historic Deerfield.

For more on the Tinkham shop tradition, see Robert Blair St. George, “A Plymouth Area Chairmaking Tradition of the Late Seventeenth Century,” Middleborough Antiquarian 19, no. 2 (December 1978): 3–11; and Robert F. Trent and Karin Goldstein, “Notes about New ‘Tinkham’ Chairs,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998), pp. 215–37.

For the Tufts chair, see Wallace Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century (1921, reprint; Framingham, Mass.: Old American Co., 1924), pp. 182–83. Edsall is documented in Benno M. Forman, “Boston Furniture Craftsmen, 1630–1730,” ms, 1969 (copy in authors’ possession).

The Eliot chair was published in The Memorial History of Boston, edited by Juston Winsor (Boston: James R. Osgood & Co., 1880), p. 415; The Dorchester Book (Boston: George H. Ellis, 1899), p. 17; Jane De Normandie, “John Eliot: The Apostle to the Indians,” West Roxbury Magazine (Hudson, Mass.: E. F. Worcester Press, 1900), pp. 31–36; and Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730, p. 77. The authors thank Robert Blair St. George for these references.