George G. Wright, sideboard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1811. White pine with yellow poplar. H. 29 1/2", W. 73", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The sideboard’s kidney shape is similar to that of contemporary mahogany examples from Philadelphia. This example sat on top of a baseboard and would have been several inches higher than it stands presently. The associated panel was probably installed in the wall above a mirror surmounting the sideboard.

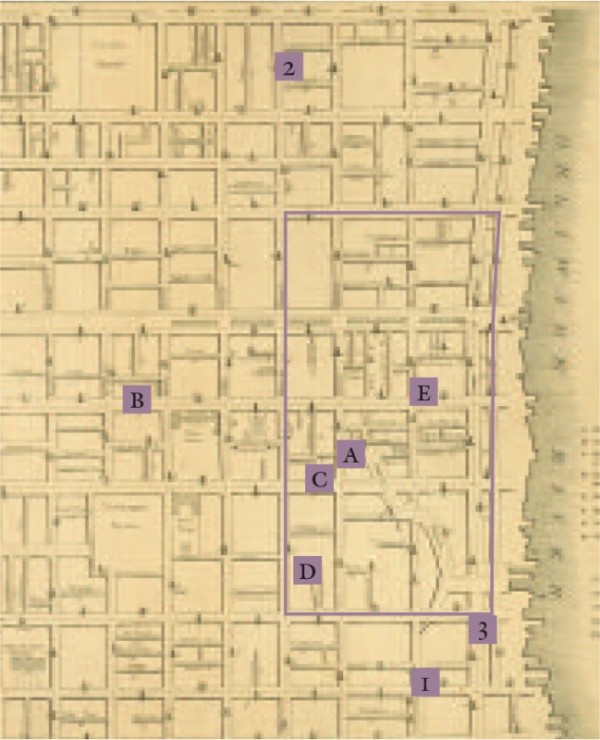

Detail of John A. Paxton’s, This New Map of the City of Philadelphia for the use of Firemen and others, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1816. Engraving on paper. 13 7/8" x 24 1/8". (Courtesy, American Philosophical Society.) George Wright’s shop locations are designated chronologically as 1–3. John Aitken’s shop locations are designated chronologically as A and B, and Joseph Barry’s as C–E. The box area shows where the French émigré community settled.

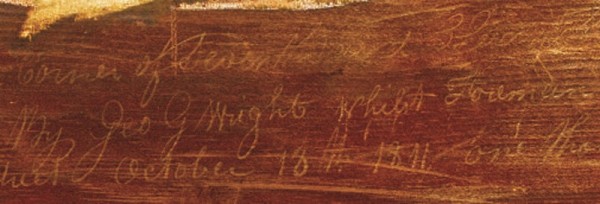

Detail of the inscription on the sideboard illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

A. C. Kern, The Waln House—S. E. Cor. Chestnut & Seventh ST., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1847. Watercolor and ink wash on paper. 11" x 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Side chair designed by B. Henry Latrobe, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1808. Yellow poplar, oak, maple, and white pine; painted, gessoed, and gilded ornament. H. 34 1/2", W. 19 3/4", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Pier table designed by B. Henry Latrobe, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1808. Yellow poplar and white pine; painted, gessoed, and gilded ornament; silvered glass, pot metal, and yellow cut velvet. H. 41 1/2", W. 66", D. 23". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The backboard is inscribed “Thos: Wetherill.” His uncle Samuel Wetherill was a paint manufacturer patronized by Latrobe and Bridport.

Card table designed by B. Henry Latrobe, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1808. Yellow poplar, maple, and white pine; painted, gessoed, and gilded ornament. H. 29 1/2", W. 36", D. 17 7/8". (Courtesy, Kaufman Americana Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table is one of a pair. They are among the earliest American examples with swivel mechanisms for their tops.

Pier table made under George Wright’s supervision by Joseph B. Barry & Son, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1810–1813. Mahogany and satinwood, mahogany and burl veneers with poplar; gilt bronze mounts and cast brass moldings. H. 38 5/8", W. 53 7/8", D. 23 7/8". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum Purchase 1976; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Like the pier table illustrated in fig. 6, this example was made without feet. This architectonic detail amplified the mass of both objects. Wright may have done everything but the carving.

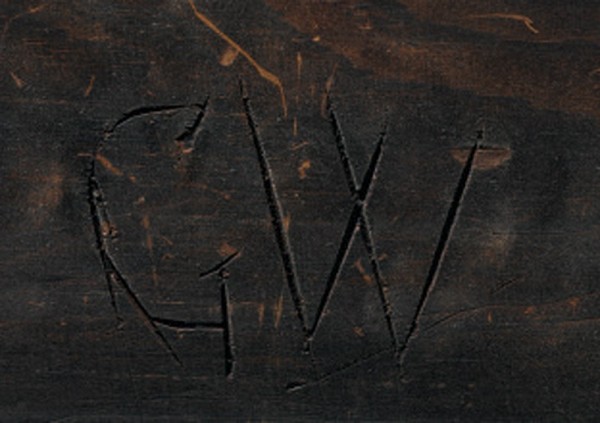

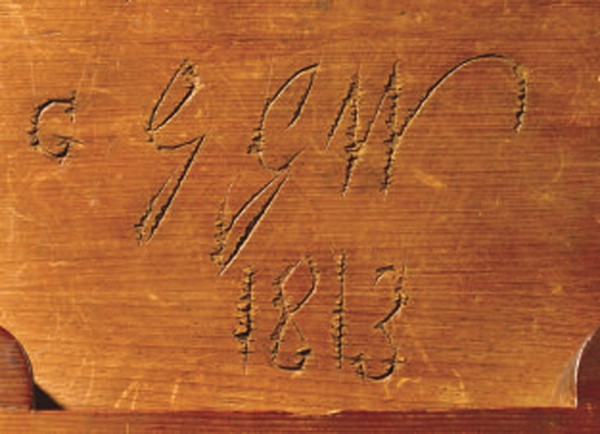

Detail of George Wright’s initials on the pier table illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

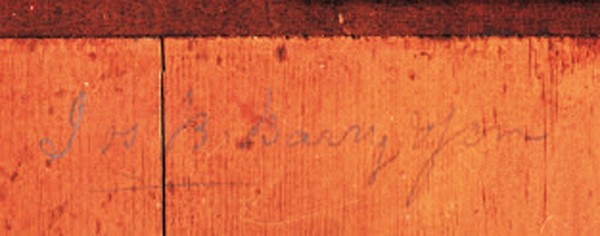

Detail of George Wright’s inscription “Jos B. Barry & Son” on the pier table illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

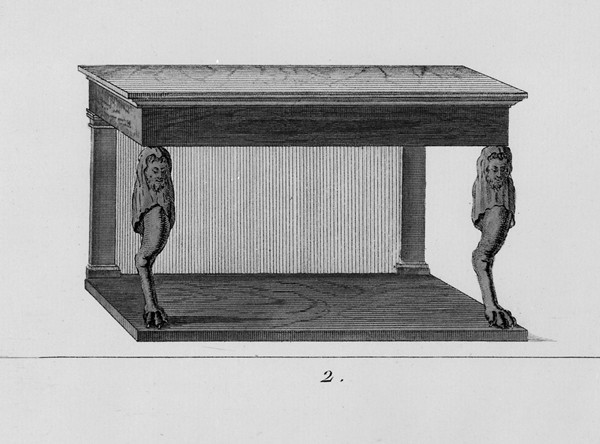

Design for a pier table illustrated on pl. 10, no. 2 in Pierre de La Mésangère. Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût (1802). (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930 [30.80.1]. Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the carving on the pier table illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

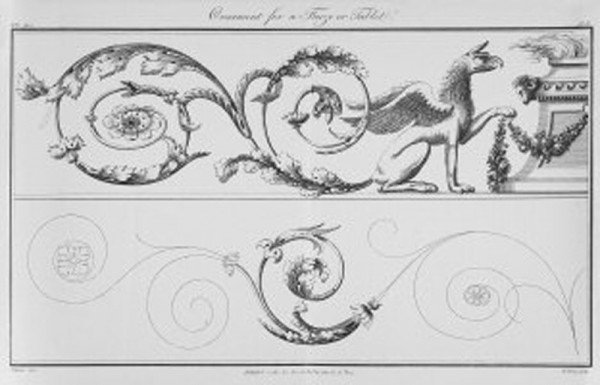

Design for a frieze or tablet illustrated on pl. 36 in Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (1791). (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

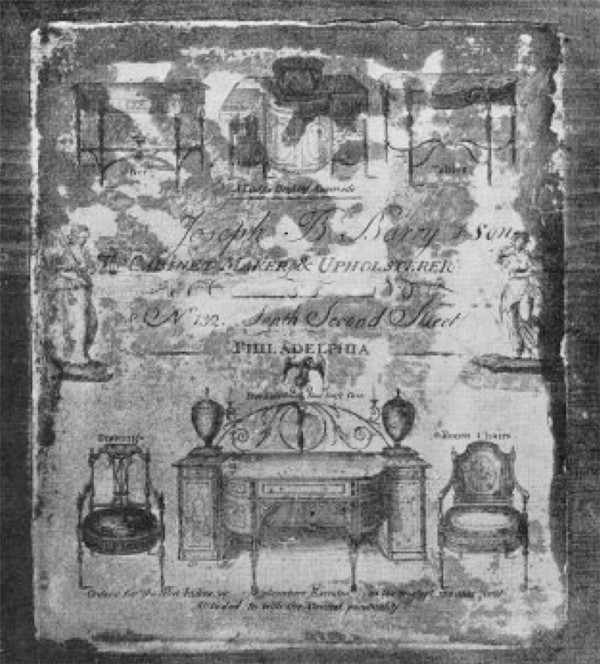

Detail of the label on the pier table illustrated in fig. 8. Barry’s shop was located at 132 South Second Street in 1804 and 1805. (William Macpherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book Philadelphia Furniture [Philadelphia: By the author, 1935], pl. 432.)

George G. Wright, card table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1813. Satinwood and satinwood, birch, and burl veneers with mahogany and white pine. H. 30", W. 38 1/4", D. 20 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) On a mechanical card table the two rear legs are hinged to swing back simultaneously as the leaf supports rotate out, thereby supporting the table as its center of gravity shifts owing to the top opening. An iron rod running through the pillar is attached to a series of pivoting iron bars housed in a box underneath the top of the table and to iron straps on the underside of the legs. This structure is found on both rear pillars of this table.

Detail of George Wright’s initials and the date 1813 cut into the underside of the card table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Michael Allison, card table, New York City, ca. 1810. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. (From the Collections of the Henry Ford Museum.) This table is one of a pair representing the only documented New York examples of the “mechanical” form known.

Detail of the plinth of the card table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the apron construction of the card table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear rail and mechanical system of the card table illustrated in fig. 15. The mechanism box is made of mahogany and beveled on three sides. The paired struts forming the short sides are half-dovetailed into the front rails. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

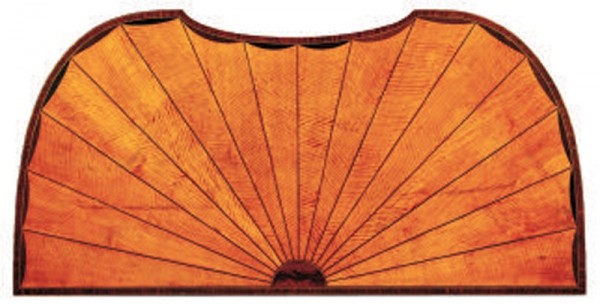

Detail of the top of the card table illustrated in fig. 15. When veneering tops in this pattern, Wright always used an odd number of rays to ensure symmetry and to have one segment centered at the front. The underside of the fly leaves and the tops of the stationary leaves of these tables are veneered with single flitches of what appears to be birch. The edges of the tops are crossbanded with the same wavy satinwood used in the rays. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

George G. Wright, breakfast table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1813. Satinwood and satinwood, mahogany, birch, and burl veneers with mahogany, white pine and yellow pine. H. 30", W. 36 1/4", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the crossbanding under the drawers of the breakfast table illustrated in fig. 22. The underside of the apron is tooth-planed beneath the strips housing the crossbanding. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table attributed to George G. Wright, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1813–1815. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine and oak. H. 29 5/8", W. 36", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table attributed to George G. Wright, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1813–1817. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with unidentified secondary woods. H. 28 1/2", W. 37", depth not recorded. (Courtesy, Photo Archives, National Gallery of Art.) The table descended in the Biddle, Priestley, and Lyon families of Philadelphia.

Card table attributed to George G. Wright, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1815–1817. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine and white cedar. H. 30", W. 35 3/4", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The secondary surfaces of this table are covered with a red wash, or “pinking.” Several similar tables attributed to Wright are known. A pair made for Robert and Elizabeth Barnhill of Philadelphia (Sewell C. Biggs Museum of American Art) have playing surfaces covered in broadcloth and edged with mahogany veneer. The Journeyman Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Pennsylvania Book of Prices (1811) referred to that edge treatment as “lipping the top for cloth.” Another card table differs primarily in the execution of its carving (Northeast Auctions, The Charles V. Swain Collection of Pewter, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, February 24, 2007, lot 849).

Detail of the playing surface of the card table illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the lower edge of the apron of the card table illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the plinth construction of the card table illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table attributed to George G. Wright, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1815–1817. Mahogany and mahogany veneers with white pine. H. 30", W. 35 3/4", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table is one of a pair.

Detail of the apron construction of the card table illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The underside is tooth-planed, indicating that it originally had strips of contrasting wood.

Robert McGuffin, card table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1807. Satinwood and satinwood, mahogany, and rosewood veneers with white pine and oak. H. 29 1/2", W. 35 5/8", D. 18". (Courtesy, Kaufman Americana Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) McGuffin was a journeyman in Henry Connelly’s shop when he made this table. It is one of a pair.

Detail of the top of the card table illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

While working as foreman for the cabinetmaking firm Joseph B. Barry & Son, George G. Wright (1780–1853) signed and dated the back of a paint-decorated sideboard (fig. 1) made for the dining room of William (1775–1826) and Mary (Wilcocks) Waln’s (1781–1841) Philadelphia house. Other furniture forms marked by Wright include an iconic pier table commissioned by French-born merchant Louis Clapier (1764–1837) and a card table bearing the date 1813, the year that Wright left Barry’s firm and established his own shop. These and other objects associated with Wright show how the contributions of apprentices, journeymen, and specialists contributed to the success of Philadelphia cabinet shops during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[1]

Details pertaining to Wright’s personal life are sketchy. He was born in Pennsylvania on July 31, 1780. Wright’s parents, John and Sarah (Fleming), were married in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and later moved to Philadelphia, where John worked as an innkeeper. At the age of thirty-two, George married Elizabeth Robins (1781–1857) of Pennsylvania. They had five children, born between the years 1814 and 1823.[2]

Marriage may have prompted George to establish his own business. Between 1813 and 1817, he was listed at four Philadelphia locations: 196 Pine Street, 93 Bell’s Court, 15 Branch Street, and Back 86 Spruce Street (fig. 2). By January 16, 1818, George and his family had moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he worked independently and in various partnerships until at least 1826. George and Elizabeth moved to Washington Township, in Brown County, Ohio, before 1845. George died there on August 5, 1853, and Elizabeth on November 22, 1857.[3]

Apprenticeship and Stylistic Development

Wright began serving his apprenticeship with Philadelphia cabinetmaker John Aitken (active c. 1787–1814) at age twenty-one, seven years later than customary. Given the fact that Wright’s term was only four years (1801–1805), he may have previously served two years with another master. Born in Dalkeith, Scotland, Aitken probably trained in Edinburgh or London before immigrating to America in 1798. Two years later, the Federal Gazette reported that his “cabinet and chair manufactory” produced “chairs of various patterns, some of which are entirely new . . . and finished with an elegancy of stile peculiar to themselves [along with] . . . desks, bureaus, book cases, bedsteads, tea tables, card ditto and dining ditto etc.” During the late 1790s Aitken entered into partnership with William Cocks, a British cabinetmaker who arrived in Philadelphia by 1790. In the August 5, 1797, issue of the Federal Gazette, their firm Cocks and Company boasted that their “long experience in London” would allow them to satisfy the demands of potential customers. Regrettably, little is known about either principal’s career or work. George Washington’s household accounts record the purchase of a pair of inlaid sideboards and a set of twenty-four square-back dining chairs with elliptically cornered tops from Aitken on February 21, 1797, and a tambour cylinder desk-and-bookcase the following month, but neither entry specifies whether the cabinetmaker was in partnership with Cocks at those dates.[4]

During his apprenticeship with Aitken, Wright would have learned to make many of the forms offered by his master’s shop and become acquainted with the intricate network of furniture makers and specialists working in the city. Wright may have also met some of Aitken’s patrons and business associates, some of whom were active in the venture cargo trade. In the January 13, 1800, issue of the Federal Gazette, Aitken reported that he had “removed the store to No. 79 Dock, near Third Street, lately occupied by Cocks & Co., where he has a large and general assortment of Cabinet Furniture suitable for the home and exportation trade.”

The Journeyman Years

Much of the information on Wright’s early career as a journeyman is derived from his inscription on the sideboard illustrated in figures 1 and 3: “Made for Mr. W. Waln, Corner of Seventh and Chestnut Streets By order / of Mr G. Bridport, By Geo G. Wright, whilst Foreman for Mr. J. B. Barry & Son / No 134 South Second Streets, October 18. 1811, one thousand eight hundred / and eleven.” He must have worked for Barry much earlier in order to have earned the trust required of a foreman.

Born in Dublin, Ireland, Barry immigrated to Philadelphia before 1790. After partnering with Alexander Calder in 1794 and Lewis G. Affleck (son of cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck) in 1795, Barry established his own business and began advertising furniture in the “newest London and French patterns.” By the turn of the century, Barry enjoyed the patronage of many prominent clients. In 1800 Barry sold Thomas Jefferson’s agent “J. Barnes” $193 worth of furniture, probably for the president’s house in Washington, D.C. Although it is impossible to determine the size and scope of Barry’s business or the number of tradesmen he employed, the 1811 Tax Assessment valued his shop and property at $21,000. By comparison, in 1809 the shop and property of John Aitken and Henry Connelly received valuations of $2,500 and $3,000 respectively. In addition to producing furniture, Barry imported and sold British and European goods. In the January 12, 1812, issue of the Aurora General Advertiser, Barry reported that during his recent “stay in London and Paris,” he had “made some selections of the Most Fashionable and Elegant Articles in Their Line, which in addition to [his] . . . excellent stock on hand, forms a display of furniture well worth the attention of the respectable citizens of Philadelphia.”[5]

During the time that Barry was abroad, Wright oversaw the day-to-day operations of his master’s shop, which included the production of William and Mary Waln’s sideboard and the mirror probably intended to hang above it (fig. 1). In 1805 the couple commissioned Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820) to design a house for their lot at the corner of Seventh and Chestnut streets. Construction began in late 1807, and the house was completed the following year (fig. 4). Like many of his British contemporaries, Latrobe was intimately involved with the furnishing of his buildings. The suite of painted furniture he designed for the Walns’ drawing room (figs. 5-7) was intended to resonate with the finishes, fabrics, and interior architectural details of that space. Although the firm responsible for making the furniture remains unknown, the decoration has been convincingly attributed to immigrant British painter and architect George Bridport (1783–1819). The name of Philadelphia carpenter Thomas Wetherill (d. 1824) is written on the backboard of a pier table from the suite, but it is unlikely that he was the maker of the entire suite, which also included at least sixteen side chairs, a pair of card tables, a window bench, and a Grecian sofa. The size of the suite suggests the involvement of a large cabinet- and chair-making shop. Joseph Barry & Sons is a likely candidate, since the suite dates circa 1808 and Bridport ordered the sideboard for the Walns’ dining room from that firm three years later.[6]

The pier table illustrated in figure 8 was also made under Wright’s supervision while Barry was in England and France. The initials “GW” are incised on a medial brace under the subtop (fig. 9), and the inscription “Jos B. Barry & Son” is written on the bottom of the plinth in Wright’s hand (fig. 10). Commissioned by Louis Clapier, who fled Santo Domingo in 1793 and arrived in Philadelphia in 1796, the pier table indicates that Barry’s shop was capable of working in the latest English and French styles. Clapier married Philadelphia native Mary Heyl in 1801, and several pieces of furniture commissioned by the couple for their house at Sixth and Lombard streets and their country house in Nicetown survive. A sofa carved with dogs and fleur-de-lis and a matching pair of chairs that descended in the same line as the pier table may also have been made in Barry’s shop.[7]

Like many of Philadelphia’s French immigrants, Clapier settled in an area of the city that was home to several important cabinet shops (fig. 2). Local furniture makers were influenced by the work of French tradesmen as well as furnishings imported by French merchants. Wealthy patrons like Clapier and merchant and financier Stephen Girard typically imported some furnishings from France and commissioned others from Philadelphia craftsmen.[8]

The Clapier pier table is a superb example of Philadelphia furniture in the French antique taste, or le goût antique. Beginning in 1802 Parisian architect and designer Pierre de La Mésangère began publishing Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût, a serial publication responsible for the dissemination of French neoclassical style to other fashion centers in the Western world. A pier table illustrated in that work is similar in form to the Clapier example (fig. 11), although the latter has columns with spiral garlands rather than the verdigris caryatids advocated by Mésangère. Barry had probably seen ormolu garlands on European furniture while traveling abroad, but they may have been prohibitively expensive or difficult for his shop to obtain. Wright’s alternative was to have the garlands executed in mahogany. The carved lyre alludes to the seventh-century Greek poet Arion, who was celebrated in classical mythology for his skill on that instrument. Like other American and European furniture adorned with such imagery, the Clapier table was most likely made for a room where music and dancing occurred.[9]

The seated griffins and arabesques on the frieze of the Clapier table are derived from plate 36 in Thomas Sheraton’s Drawing Book (1791) (figs. 12, 13). The inclusion of these details is somewhat unusual, since they reflect an earlier phase of neoclassicism somewhat at odds with the table’s avant-garde French form. New York cabinetmaker Charles Honoré Lannuier began making pier tables in le goût antique as early as 1805, but that style did not attain widespread popularity in America until the 1820s. A narrow and early date range can be assigned to the Clapier table based on the pencil inscription on its label (fig. 14) and Wright’s departure from Barry’s shop in 1813. The words “& Son” refer to Joseph Barry Jr. (active 1810–1840) who became a partner in 1810.[10]

Furniture Documented to George Wright’s Shop

A pair of “mechanical” card tables initialed and dated by Wright are benchmarks for attributing other work to his shop (figs. 15, 16). New York cabinetmaker John Hewitt mentioned that form in his account book in 1809, but the earliest reference to mechanical tables in Philadelphia is in The Journeyman Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Pennsylvania Book of Prices published two years later. This design may have arrived through the venture cargo trade or been transmitted by New York journeymen who moved to Philadelphia (fig. 17). Given the fact that Joseph Barry advertised in a New York newspaper for four experienced journeymen cabinetmakers in 1810, it is possible that Wright learned to make mechanical tables while working as a journeyman in his former master’s shop. Based on the number of surviving examples, mechanical tables appear to have been less popular in Philadelphia than in New York. Price may have been a factor. According to the Pennsylvania Book of Prices, workmen received $16.36 for making a mechanical table. That was more than seven times the amount received for a standard square card table with swing leg ($2.31) and more than three times the amount received for a standard kidney-shaped table with a commode front ($4.68). Wright’s mechanical tables (figs. 15, 16) would probably have been more expensive than any mechanical table listed in the Pennsylvania price book, owing to the lavish use of satinwood.[11]

Unlike most New York mechanical tables, which have a single columnar support, Wright’s examples have three thin pillars that rest on a trefoil-shaped plinth. This unusual design required him to bore out two columns (rear) to accommodate the iron rods of the swivel mechanism rather than one. The curved shoulders of his legs are modifications of the “sweep” pattern common on New York tables as well as in French Directoire and English Regency designs. Wright used contrasting panels to decorate the plinth and the tops and sides of the legs. Later examples made by Wright and his competitors often have legs with paneled sides and acanthus carving on the top.

Probably made of horizontally laminated boards, the plinths of the satinwood tables are capped with thin, thumbnail-molded boards that overhang slightly (fig. 18). This feature occurs on other tables documented and attributed to Wright’s shop. On the convex sections of the plinth, the veneer that covers the vertical surfaces is tucked into grooves in the pine core. Wright knew this would prevent the veneer from popping off if the glue joint weakened.

The aprons of the satinwood tables consist of solid boards at the front and sides glued to horizontally laminated, curved sections with butt joints staggered for strength (fig. 19). Typical of Wright’s work, the laminated sections are nailed from the underside at each end. The concave sections of the façade are made from a separate vertical board so the veneer on the outside never goes over end grain. Wright eventually abandoned this feature, probably because of the extra work it required. The fly rails are attached to a birch block and their joints are held together with a metal pin. Like many cabinetmakers, Wright made the fingers circular for greater clearance and gave them a shoulder to stop the fly rails from rotating past ninety degrees (fig. 20).

The Pennsylvania Book of Prices described card tables similar to the documented examples as having “Serpentine Corners with Straight Front and End Rails.” In all of his later card tables, Wright used a slightly elliptical, or “round,” front—a standard Philadelphia design for which journeymen received an additional twenty-eight cents. The tops of the satinwood tables are constructed in the method specified in contemporary price books, with two pine boards held in place with “square clamps,” or battens, and a narrow “slip” of mahogany glued across the exposed rear edges of the tops. Wright made his clamps out of mahogany, for strength and stability, and attached them to the pine center boards with a tongue-and-groove joint. Afterward, he applied the veneer and crossbanding (fig. 21). On later tables, he set the clamps at an angle to provide additional strength and more glue surface for the crossbanding.[12]

A breakfast table (fig. 22) made en suite with the card tables has another feature typical of Wright’s work. The crossbanding below the drawers is set into a separate mahogany strip that is glued and nailed to the underside of the apron (fig. 23). This made the crossbanding less susceptible to damage and loss.

Furniture Attributed to George Wright’s Shop

Several tables can be attributed to Wright’s shop based on details shared with his documented work. The mechanical table illustrated in figure 24 is made of mahogany with no contrasting inlay. Except for having a single pillar, which dictated a slightly different mechanism, and a glued and nailed bead on the lower edge of the apron, the construction of this table matches that of the satinwood examples (figs. 15, 16). The top has pine clamps attached to the core board with tongue-and-groove joints, and its primary veneered surface features nine rays emanating from a semicircle. The sweep legs follow conventional Philadelphia style in having acanthus carving and reeding on top. Wright probably made this table before 1815, when mechanical examples became increasingly obsolete.[13]

During the early to mid-1810s, Wright began making swivel-top card tables. The examples illustrated in figures 25 and 26 are attributed to his shop based on parallels with the marked satinwood tables: the tops have nine rays of highly figured veneer; the plinths are capped with a thin, thumbnail-molded board; and the tables have similarly constructed aprons. The pillars on the table illustrated in figure 25 also have turnings similar to those on furniture in the satinwood suite (see figs. 15, 22). On the other swivel-top example (fig. 26), the pillars are superimposed balusters with reeding at the top and leaf carving below. The leaves mirror those on the legs and harmonize with the floral carving on the curved sections of the plinth. This concave plinth design is found on all swivel-top tables attributed to Wright. On the table illustrated in figure 26, he added decorative veneer to the playing surface (fig. 27), an option that would have increased the cost.[14]

Although the construction of Wright’s swivel-top tables is relatively consistent, minor variations can be observed. On the card table illustrated in figure 26, he glued and nailed wide strips of lightwood (possibly satinwood) to the tooth-planed lower edges of the apron (fig. 28) just as he did on the satinwood breakfast table (figs. 22, 23). These strips were intended to simulate stringing and protect the veneer on the lower edge. The plinth construction represents a more significant departure. To form the core, Wright used six pieces of mahogany, two boards arranged in an X-shape and four blocks to fill in the interstices (fig. 29). The circa 1815 addendum to the New-York Revised Prices for Manufacturing and Cabinet and Chair Work (1810) described this structure as “lapp’d and the corners filled in.” The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet Work (1828) referred to “lapping and filling in blocks.”[15]

A similar pair of card tables (fig. 30) has slightly different carving, suggesting that Wright may have employed more than one carver or purchased piecework (plaques, legs, pillars) from specialists who employed different carvers. Although these tables originally had thin strips of wood glued and nailed to the lower edges of their aprons like the objects illustrated in figures 22 and 26, Wright made the front and side rails out of solid mahogany, rather than his customary laminated white pine, and joined them at the front corners with large mahogany “keys” (fig. 31). He also used a solid block of mahogany for the core of the plinth.

Although Wright was a native-born artisan, his stylistic vocabulary emerged in a cosmopolitan setting. During the 1790s craftsmen from England and France came to Philadelphia in search of opportunities created by that city’s burgeoning economy. Wealthy patrons like William and Mary Waln, Louis Clapier, and Stephen Girard were eager to furnish their homes in the latest European neoclassical styles, and immigrants like Wright’s master John Aitken were more than capable of meeting their demands. To maintain a competitive edge, some Philadelphia tradesmen ventured abroad. When his shop produced the sideboard illustrated in figure 1, Joseph Barry was traveling through England and France, ostensibly to keep abreast of current designs and acquire European-made furnishings that he could sell at home. As an apprentice in Aitken’s shop and then as a journeyman working for Barry, Wright experienced a broader range of stylistic influences than many of his peers.

Wright also appears to have been familiar with the work of Philadelphia cabinetmakers Robert McGuffin (b. 1778) and Henry Connelly. McGuffin worked as a journeyman for Connelly from before 1806 to at least 1809, producing elaborate satinwood tables with veneered tops similar to those made by Wright (figs. 32, 33). This suggests that Wright may have worked with McGuffin in Connelly’s shop before joining Barry’s workforce.[16]

Wright’s furniture attests to his training in an immigrant tradition, his experience as foreman in a major cabinetmaking shop, and his ability to make the transition from journeyman to master. His innovative construction, eye for wood selection, and mastery of veneer decoration set him apart from many of his contemporaries. The tables documented and attributed to Wright further suggest that he was an astute businessman. Faced with the nuances of the Philadelphia marketplace, he developed a range of forms and options to satisfy the different tastes and budgets of his customers. Undoubtedly case furniture and possibly seating by Wright will come to light and provide a clearer picture of this talented cabinetmaker’s total output.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Irfan Ali, Louisa Bartlett, Nicholas R. Bell, Lynda Cain, Katherine Chabla, Tara Chicirda, Jeff Cohen, David H. Conradsen, Wendy A. Cooper, Kathryn Coyle, David deMuzio, J. Michael Flanigan, Samuel M. Freeman II, John Stuart Gordon, Ryan Grover, Michael Harkless, Brock W. Jobe, Linda Kaufman, Peter M. Kenny, Kelly Lyles, Robert Lyles, Lisa Minardi, Robert D. Mussey Jr., Sumpter Priddy III, Karl J. C. Saberg, Christopher Swan, Christine Thomson, Matthew A. Thurlow, Nicholas Vincent, and Gregory Weidman.

George Wright’s full middle name remains unknown, but he regularly identified himself using his middle initial. For the marked card table, its mate, and a breakfast table from the same suite, see Sotheby’s, Fine Americana, New York, October 24, 1993, lots 366, 367. Wright’s initials and date are on the underside of the card table illustrated in figure 15.

The Pennsylvania census of the early nineteenth century did not record the town where Wright was born. Vital Records of Cambridge, Massachusetts to the Year 1850 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1914), 1: 785. Archives of the City and County of Philadelphia (hereafter cited as ACCP), record no. 60.14, Apprenticeship and Redemptioner’s Index (hereafter cited as ARI), p. 49. The only reference to Wright in Philadelphia newspapers is a notice for the Fire Hose Association signed by “Geo. G. Wright, Sec’ty” in the United States Gazette on September 27, 1806.

Deborah Ducoff-Barone, “Checklist of Cabinetmakers and Chairmakers of Philadelphia, 1800–1815,” Antiques 139, no. 5 (May 1991): 986–95. Wright was in partnership with Joseph Roseman, who was a fancy-chair maker, ornamentor, and gilder in Pittsburgh in 1818. They advertised in the Pittsburgh newspapers in January, July, August, and September of that year, with their shop at Fourth Street, above Wood Street. J. M. Riddle and M. M. Murray, The Pittsburg Directory for 1819 (Pittsburg, Pa.: Butler & Lambdin, 1819), p. 100. Information on Wright’s Pittsburgh career can be found in Pittsburgh Furniture Project, American Decorative Arts Department, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1819 Wright partnered with “M’Kown,” and the city directory listed their place of business as Fourth Street between Wood and Smithfield streets. In 1826 the city directory listed Wright alone at that address (City Directories of the United States, circa 1655–1881 [Woodbridge, Conn.: Research Publications, 1983], microfiche, pp. 100, 150). The authors thank Jeffrey Cohen, Professor of Architecture at Bryn Mawr College for suggesting the Paxton map. Will and Estate Inventory of George Wright, Court of Common Pleas, Brown County, Ohio, John B. Higgins Will Book (1853), pp. 99–101 (will recorded Aug. 22, 1853; inventory recorded Nov. 4, 1853).

ACCP, record number 60.14, ARI, p. 49. Aitken signed a certificate vouching for the value of a “draught board” made by a Mr. Dunavan on September 21, 1789 (Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts, no. 55.520, Winterthur Library). Unlike Henry Connelly, Aitken took few apprentices. Federal Gazette (Philadelphia), June 9, 1790. Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “The Painted Furniture of Philadelphia: A Reappraisal,” Antiques 169, no. 5 (May 2006): 137. Cocks (Cox) is listed in the 1790 census at the same address mentioned in his 1796 advertisement (www.familyhistory.com). He trained renowned cabinetmaker William Camp, who moved to Baltimore after completing his apprenticeship in 1801. Charles Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period (New York: Viking Press, 1966), p. 147, fig. 96. Washington’s Philadelphia Household Account Book, March 2, 1793–March 25, 1797, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Washington purchased the chairs and sideboards on February 21, 1797, and the cylinder desk-and-bookcase on March 13, 1797.

Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), p. 219. Federal Gazette and Baltimore Daily Advertiser, February 9, 1803. Tax Assessment Records, New Market Ward, ACCP, as cited in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art, p. 220.

Latrobe and Bridport were both particular about quality of workmanship. For example, Latrobe ordered painted furniture from the renowned Finlay brothers of Baltimore for James and Dolley Madison in 1809. It is only logical that he and Bridport would have hired one of the leading cabinet shops in Philadelphia to make the Waln painted suite. The Waln sideboard (fig. 1) establishes the fact that Barry’s shop was capable of producing elaborate and sophisticated painted furniture. Kirtley, “Painted Furniture of Philadelphia,” pp. 138–41. Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “Collector’s Notes,” Antiques 169, no. 5 (May 2006): 76–80. In each city where he worked, Latrobe appears to have patronized a small group of artisans. Mr. and Mrs. Oliver Hopkinson sold the sideboard to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1913. It had descended in the male line of her family from her grandfather Dr. William Swaim, who purchased the Waln house in 1826.

For other objects documented to Barry’s shop, see Antiques 65, no. 2 (February 1954): 135–36 (breakfront bookcase); Antiques 171, no. 4 (April 2007): 92–93 (tall clock case, Philadelphia Museum of Art); Antiques 135, no. 5 (May 1989): 1218–19 (sideboard dated 1813); Antiques 135, no. 5 (May 1989): 1223 (tall-post bed billed to Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, 1807–1810, Hagley Museum and Library); Page Talbot, Classical Savannah (Savannah, Ga.: Telfair Museum of Art, 1995), pp. 148–49 (set of upholstered-back open armchairs owned by Isaac Minis of Savannah, 1829–1833); and Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “Philadelphia Furniture in the Empire Style,” Antiques 171, no. 4 (April 2007): 94–95 (sideboard table stenciled “Joseph Barry and Lewis Krickbaum”). The authors thank Peter Kenny and Matthew Thurlow for making the Clapier table accessible.

Andrew Brunk, “To Fix the Taste of Our Country Properly: The French Style in Philadelphia Interiors, 1788–1800” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2000), p. 6. Robert D. Schwarz, The Stephen Girard Collection: A Selective Catalog (Philadelphia: Girard College, 1980), n.p.

It is possible that Barry owned a copy of Mésangère’s publication. In the January 12, 1812, issue of the Aurora General Advertiser (Philadelphia), Barry reported that he had “lately returned from . . . London and Paris [where] he made some selections of the Most Fashionable and Elegant Articles . . . which [are] well worth the attention of the respectable citizens of Philadelphia.” Some of these objects may have been in le goût antique. For more on that style in America, see Peter M. Kenny, Frances F. Bretter, and Ulrich Leben, Honoré Lannuier: Cabinetmaker from Paris (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), passim. The authors thank Nicholas Vincent for pointing out European pier tables with spiral ormolu garlands. See Enrico Collee, Italian Empire Furniture: Furnishings and Interior Design from 1800 to 1843 (New York: Rizzoli, 2001), fig. 30; Christopher Wilk, Western Furniture: 1350 to the Present Day in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (New York: Cross River Press, 1996), pp. 132–33, 138–39; and James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), p. 31.

Barry had at least three printed labels: Old Print Shop advertisement, Antiques 34, no. 1 (July 1938): 36; the label on the pier table illustrated in figure 8; and the label on a breakfront desk-and-bookcase originally owned by Savannah, Georgia, merchant Robert Mackay, who shared commercial space with Barry (Mrs. Charlton M. Theus, “Furniture and Cabinetmakers of Coastal Georgia,” Antiques 65, no. 2 [February 1954]: 135–37). The latter two labels have changes made to James Akin’s original plate. The words “From London” were eliminated and the address changed to “N 132 South Second Street.” Two female figures and an eagle (on the brass rail of the sideboard) were added. To the label on the pier table illustrated in figure 8, the words “& Son” were added in pencil to Barry’s name. On the Mackay breakfront label, the words “& Son” were added to the engraved plate. The images on Barry’s labels were taken directly from Thomas Sheraton’s Appendix to the Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (1802). Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (New York: Dover Publications, 1972), pp. 145–204. Baltimore cabinetmaker William Camp also commissioned Akin to engrave his label, using different plates from Sheraton’s Cabinetmaker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book. Camp’s label is owned by the Baltimore Museum of Art and illustrated in Robert Bishop, Centuries and Styles of the American Chair, 1640–1970 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972), p. 222, fig. 314.

For the term “mechanical table,” see The New-York Revised Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (1810), p. 25. Mechanical tables are also mentioned in the 1817 edition. For more on Hewitt, see David L. Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992), p. 217; and Marilyn A. Johnson, “John Hewitt, Cabinetmaker,” Winterthur Portfolio 4 (1968): 185–205. The Journeyman Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Pennsylvania Book of Prices (1811) uses the term “Pillar and Claw Card Table” instead of “mechanical table.” Mercantile Advertiser (New York), December 3, 1810.

Journeyman Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Pennsylvania Book of Prices, p. 33. The New-York Revised Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (1810), specified “3 joints in each top, and clamp’d, slip’d on the back edges, and veneered on 3 sides, or the inside lipped for cloth, the edges banded” (Philip D. Zimmerman, “New York Card Tables, 1800–1825,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005], pp. 122–26). The top construction of Philadelphia and New card tables follows the same patterns (Zimmerman, “New York Card Tables,” p. 125).

Zimmerman, “New York Card Tables,” p. 130. The first known use of the swivel-top in America is the card table from the Waln suite designed by Latrobe in 1808 (fig. 7).

The former table is illustrated as “better” in Albert Sack, The New Fine Points of Furniture, Early American (New York: Crown Publishers, 1993), p. 294; Sotheby’s, American Heritage Auction of Americana, New York, November 17–19, 1977, lot 733.

The strips (fig. 28), which bear fine circular saw marks, may have been purchased from a veneer specialist.

For more on McGuffin and Connelly, see Merri Lou Scribner Schaumann, “Henry Connelly, Cabinetmaker and Chairmaker,” Cumberland County History 13, no. 2 (Winter 1996): 95–96. A sideboard at the Philadelphia Museum of Art has a Henry Connelly label, McGuffin’s signature, and the date 1806. The Philadelphia tax assessment for 1808–1809 lists McGuffin and Connelly together (Archives of the City and County of Philadelphia, County Tax Assessment Ledger for the South Ward, 1785–1844, vol. 2 [1808–1809], in “Philadelphia Early Tax Records,” comp. Allen Weinberg, Department of Records, Philadelphia, 1960). The authors recently discovered that the card table illustrated in figure 32 is marked “McGuffin 1807.” We thank Wendy Cooper, Tara Chicirda, and Christopher Snow for inspection and infrared photography of that object.