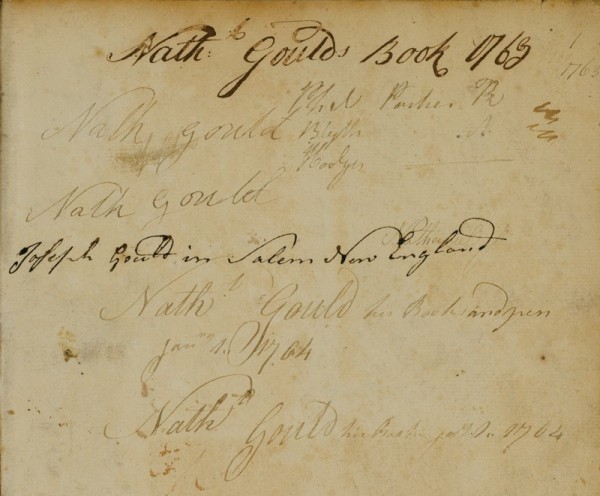

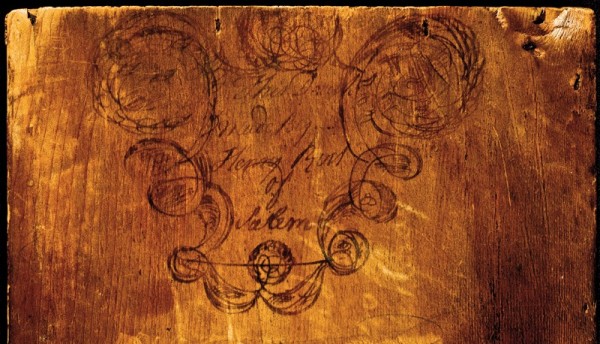

Title page of Nathaniel Gould’s account book covering the years 1763 to 1781. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The account book has a few entries from the late 1750s that may have been transferred from an earlier book and a few entries that postdate Gould’s death in 1781. The later entries may have been recorded by Gould’s attorney Nathan Dane.

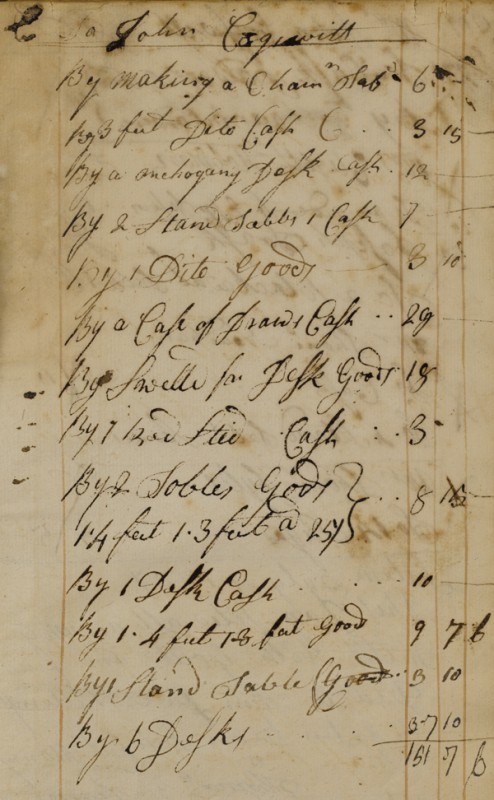

Ca. 1759 credit entry for John Cogswell in Nathaniel Gould’s daybook covering the years 1758 to 1763. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) At the end of each line Gould wrote “cash” or “goods” to designate the form of payment. The word “goods” could refer to furniture or other commodities sold by Gould, including wood, sugar, fishing line, and wine.

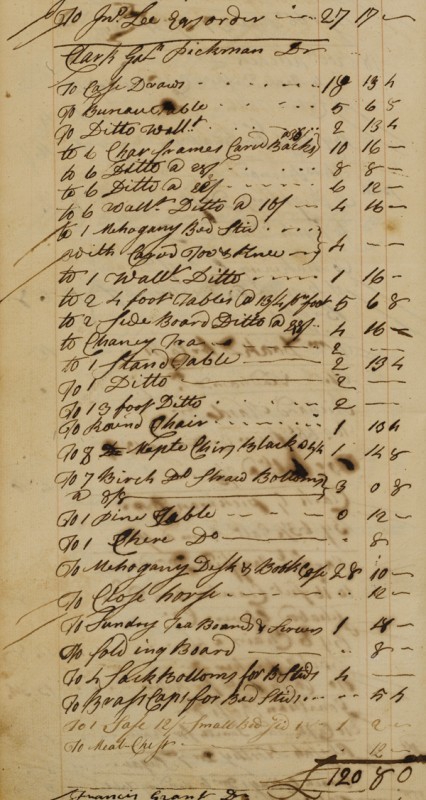

August 24, 1770, debit entry for Clark Gayton Pickman in Nathaniel Gould’s daybook covering the years 1767 to 1784. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

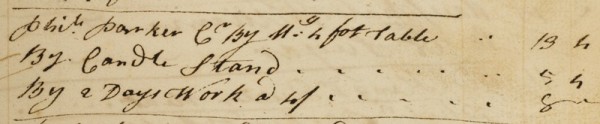

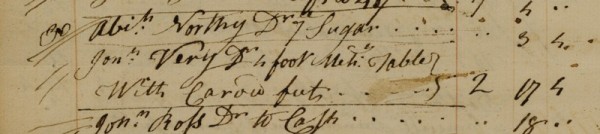

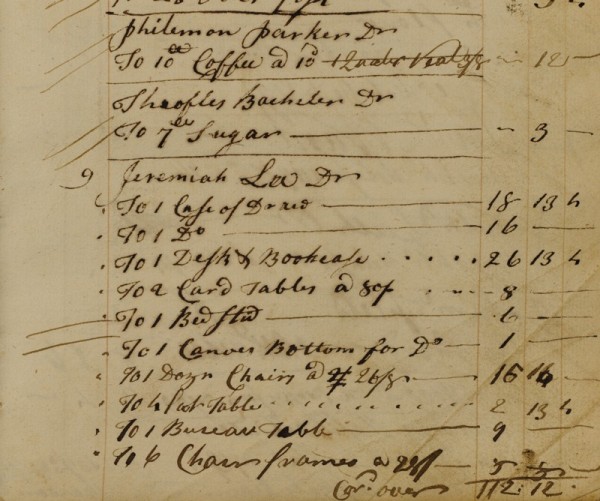

Detail of page for November 20–26, 1768, in Nathaniel Gould’s daybook covering the years 1767 to 1784. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Most daybook entries are debits. The credit entry for Philemon Parker dated November 20, 1768, indicates that he performed three days’ work for Gould in addition to making a four-foot table and a candlestand. Parker maintained his own shop and was not an employee of Gould.

November 30, 1768, debit entry for Jonathon Very in Nathaniel Gould’s daybook covering the years 1767 to 1784. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers attributed to the shop of Nathaniel Gould, Salem, Massachusetts, 1781. Mahogany with white pine. H. 36 1/8", W. 39 1/16", D. 21 9/16". (Courtesy, Historic New England; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chest descended in the family of Charles Chauncey Foster (1785–1875). In 1816 he married Catherine Cabot (1789–1862), the seventh surviving child of Andrew Cabot (1750–1791) and his wife, Lydia (Dodge) (1748–1807). The chest is probably the “bureau table” that Andrew Cabot purchased from Nathaniel Gould on February 24, 1781 (fig. 7). As the relatively unfigured wood in this chest suggests, the mahogany available to Gould during the Revolution was of lesser quality than that available before the war. The third drawer from the top has plane tears on the surface. Gould might have discarded that drawer front if wood had been more available.

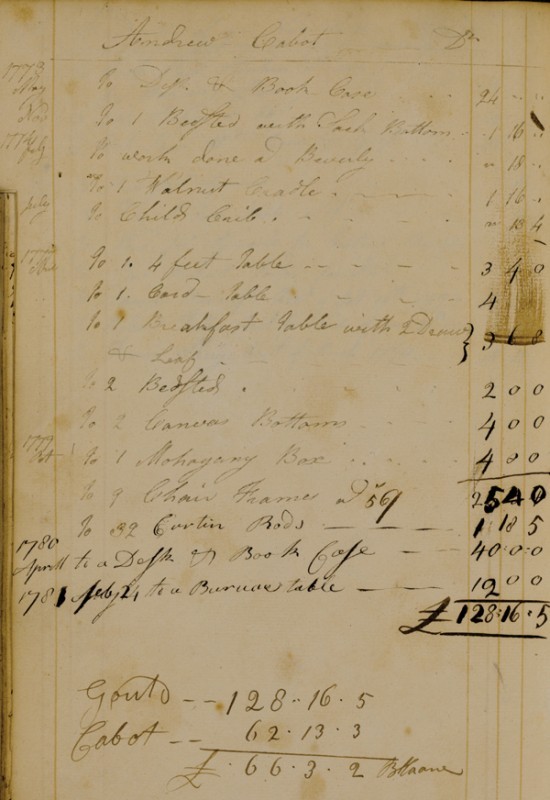

February 24, 1784, debit entry for Andrew Cabot in Nathaniel Gould’s daybook covering the years 1767 to 1784. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Cabot’s inventory listed two mahogany bureaus (Essex County Probate no. 4431, bk. 360, pp. 499–506), and his will directed that his property be divided equally between his children after his wife’s death (Suffolk County Probate no. 22925, bk. 105, p. 41).

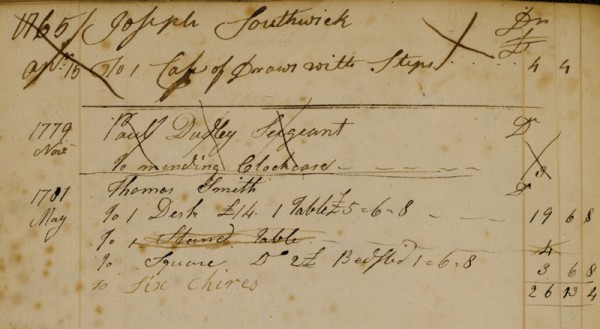

April 15, 1765, debit entry for Joseph Southwick in Nathaniel Gould’s account book covering the years 1763 to 1781. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

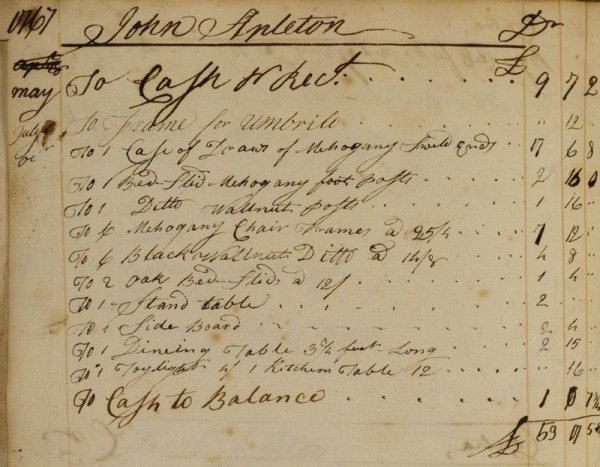

July 1767 debit entry for John Appleton in Nathaniel Gould’s account book covering the years 1763 to 1781. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest-on-chest attributed to the shop of Nathaniel Gould, Salem, Massachusetts, 1764–1768. Mahogany with white pine. H. 91", W. 44 1/2", D. 22 7/8". (Courtesy, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, William Rockhill Nelson Trust; photo, Jamison Miller.) Gould used the term “case of drawers” to identify both cabriole-leg high chests and chest-on-chests.

April 9, 1775, debit entry for Jeremiah Lee in Nathaniel Gould’s daybook covering the years 1767 to 1784. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

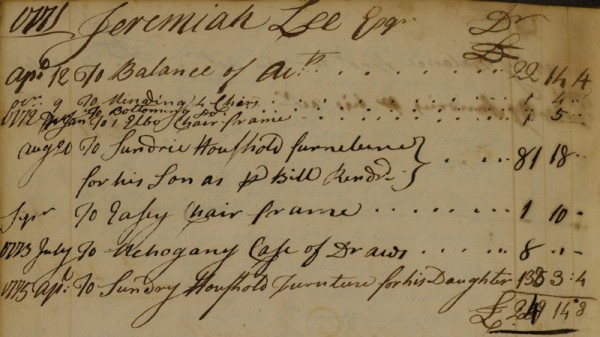

Debit entries for Jeremiah Lee in Nathaniel Gould’s account book covering the years 1763 to 1781. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The August 20, 1772, entry pertains to furniture for Lee’s son Joseph. The April 6, 1775, entry pertains to furniture for Lee’s daughter Mary.

Nathaniel Tracy House, Newburyport, Massachusetts, ca. 1771. (Courtesy, Phillips Library Photograph Collection, Peabody Essex Museum.) The desk-and-bookcase that Jeremiah Lee purchased for his daughter was among the original furnishings of this house.

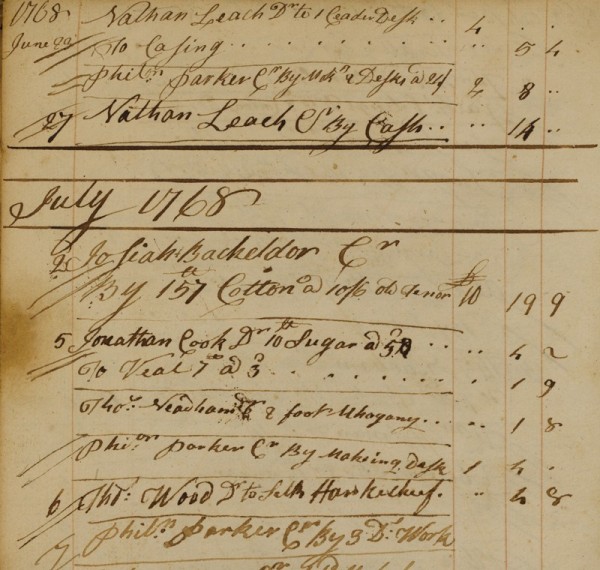

June 23, 1768, debit entry for Nathaniel Leach in Nathaniel Gould’s daybook covering the years 1767 to 1784. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Gould purchased two desks from Philemon Parker and sold one to Leach. The cedar primary wood of Leach’s desk, crating charges recorded by Gould, and his patron’s profession as a ship captain suggest that this desk was intended for export. Gould charged £4 for standard cedar and cherry desks and £4.13.4 for slightly more elaborate cedar examples.

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of Nathaniel Gould, Salem, Massachusetts, ca. 1775. Mahogany and white pine. H. 105", W. 42", D. 22". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. J. Russell Sage; photo, Gavin Ashworth, Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.) The door panels are book-matched and have prominent stripe figure like the plank used for the fallboard.

Detail of the inscription “Nath Gould not his work” on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

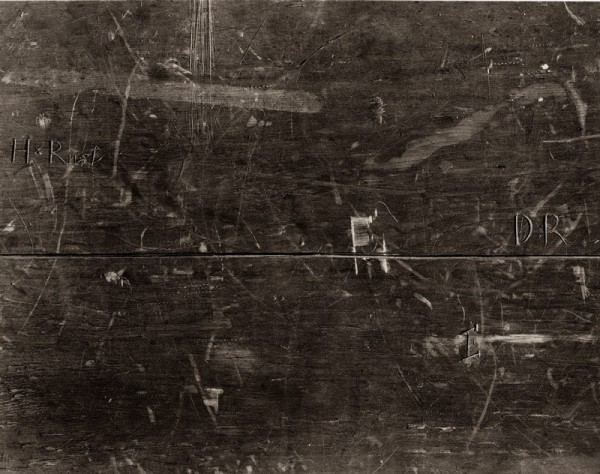

Desk attributed to the shop of Nathaniel Gould, Salem, Massachusetts, 1758–1780. (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy.) Although this desk is marked “H x RUST,” its stylistic and structural features suggest that it originated in Nathaniel Gould’s shop. The construction differs from that of the Rust desk illustrated in fig. 19.

Detail of the mark on the desk illustrated in fig. 17.

Henry Rust, desk, Boston, Massachusetts, 1770. Mahogany with white pine. H. 42", W. 37", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of the family of Edward and Kaye Scheider [2007.158 a-e]; photo, Gavin Ashworth, Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.) Rust was a competent cabinetmaker, but his work falls short of that performed in Nathaniel Gould’s shop.

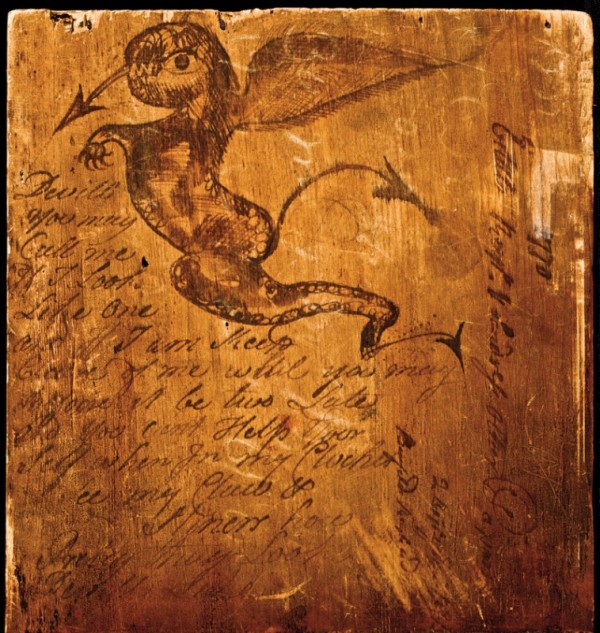

Detail of the inscription on the desk illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing additional writing and drawing on the desk illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

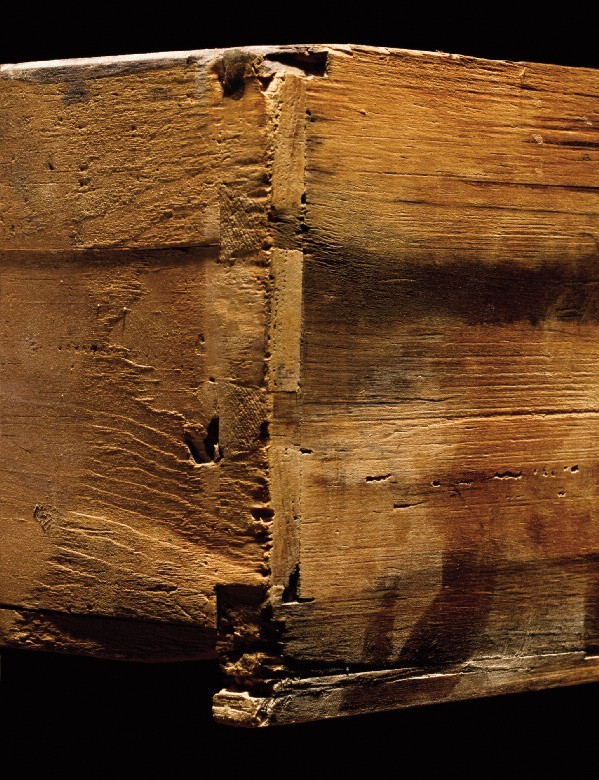

Detail showing the dovetailing at the back of a large drawer from the desk illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the dovetailing at the back of a large drawer from the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

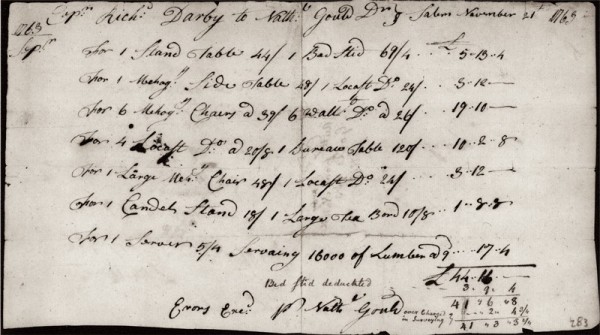

Invoice from Nathaniel Gould to Richard Derby, Salem, Massachusetts, November 21, 1763. (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum.) The invoice is in the Derby Papers, Miscellaneous Receipts, MSS 37, box 15, folder 5.

Detail of the right front foot of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 6. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the dovetailing and beading of a drawer from the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Kemble Widmer.)

Detail of the lock on the lid of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

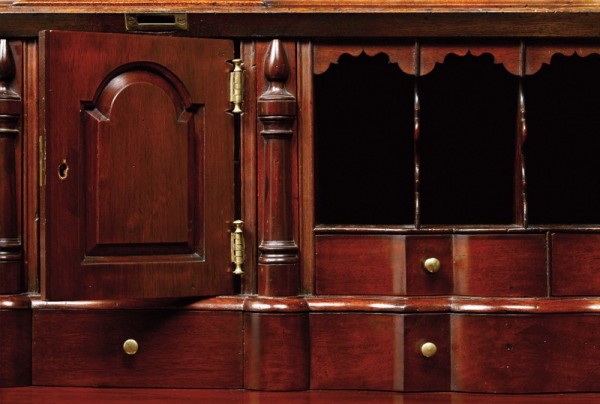

Detail of the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Gould typically used clock hinges for prospect doors.

Detail of the number “7” on the back of the third drawer from the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 6. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The numbers denoted drawer height.

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of Nathaniel Gould, Salem, Massachusetts, 1765–1781. Mahogany with white pine. H. 96 1/8", W. 44 1/8", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, C. L. Prickett Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cabot family tree showing purchases of desk-and-bookcases and lines of descent. (Genealogy by Joyce King; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

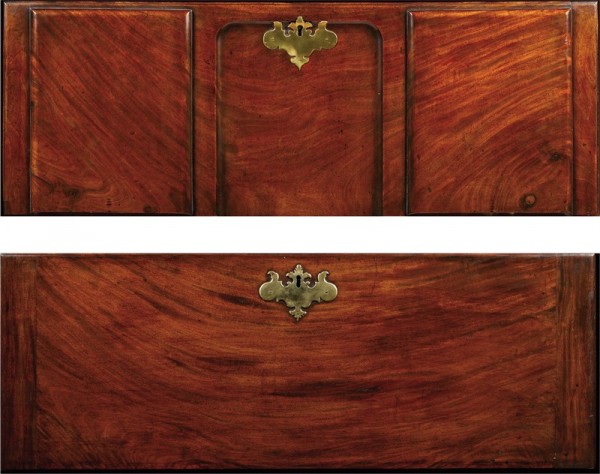

Composite detail showing the fallboards of the desk-and-bookcases illustrated in figs. 15 (top) and 30 (bottom). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the door arches and pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the drop on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 6. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Compass points on drops associated with Gould’s shop and variations in the size and shape of standard components indicate that he and his workmen rarely used patterns.

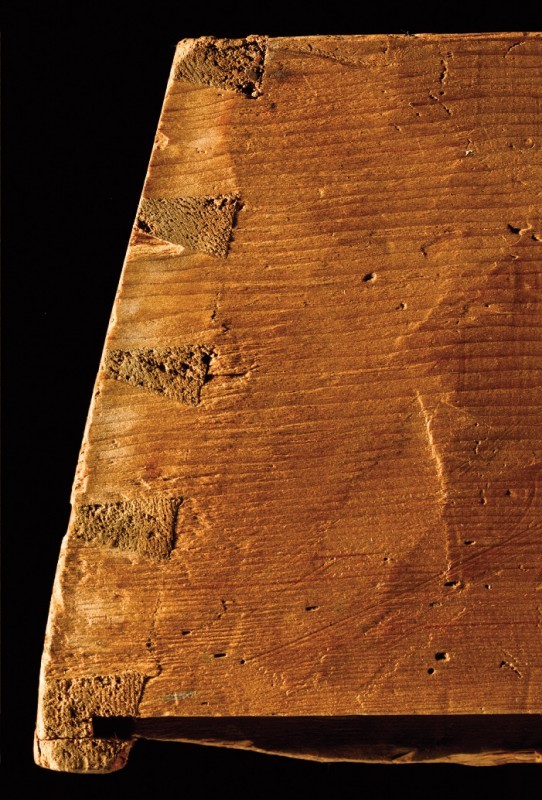

Detail of the dovetailing on the lower drawer of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 6. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

On May 1, 1758, a young tradesman named Nathaniel Gould (1734–1781) made the first entry in his daybook, recording the sale of a walnut table to Salem, Massachusetts, tailor Samuel Archer Jr. Before the discovery of Gould’s account book and daybooks (fig. 1) in the Nathan Dane Papers in the Massachusetts Historical Society, he was regarded as one of many furniture makers active in Salem during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. When correlated with existing furniture and documentary references to Gould in other sources, the entries in these journals demonstrate that Gould parlayed the patronage of Salem’s merchant elite into considerable financial success.[1]

The earliest daybook covers the years 1758 to 1763. A five-year gap between the last entry in that journal and the first entry in the later one indicates that Gould originally had three daybooks. The other surviving daybook has entries from 1767 to Gould’s death in 1781 and continues to 1784. Together with his account book, these documents shed light on the furniture, trade practices, marketing strategies, and business transactions of one of Salem’s finest cabinetmakers.[2]

Born on November 17, 1734, Gould was the son of Nathaniel (1697–1746) and Elizabeth (French) Gould (1698–1746). Both parents died when Nathaniel Jr. was only twelve, too young to have begun serving an apprenticeship with his father. Guardianship passed to his uncle James Gould (1696–1771), a wheelwright, on January 3, 1747.[3]

Although no indenture documents for Nathaniel are known, it is possible that he trained with Charlestown, Massachusetts, cabinetmaker Thomas Wood (1708–1800). Gould probably completed his term by December 1756, when he was described as a cabinetmaker residing in Charlestown in a transaction involving his sale of inherited property. Four years later he married Wood’s daughter Rebecca (1739–1807) and shortly thereafter began doing business with his father-in-law. Gould’s earliest daybook records the sale of mahogany, walnut, and furniture hardware to Wood in 1761. Over the next fourteen years, Gould continued to provide hardware while purchasing two beds and forty desks from his father-in-law. Most of the desks were made of cedar and probably intended for export.[4]

The theory that Gould came of age as a cabinetmaker in Charlestown is further supported by his relationship with John Cogswell (1738–1819), who may have trained there in the shop of cabinetmaker Timothy Gooding Jr. When Gould became overwhelmed with orders for furniture in June 1759, he subcontracted the production of nine desks, a case of drawers, six tables, four stands, and a bed to Cogswell (fig. 2). The latter artisan was only twenty-one years old at that date and had only recently set up shop in Boston. Gould and Cogswell probably became acquainted while serving their apprenticeships in Charlestown.[5]

Gould arrived in Salem shortly after completing his apprenticeship. On March 14, 1757, he contributed £3.12 to a fund for soldiers from that town who volunteered to defend Fort William Henry during the French and Indian War. Among the donors, Gould was one of the youngest and the only cabinetmaker. His decision to support the fund, which provided £10 for each volunteer, may have been motivated by his cousin James Gould’s participation in the expedition. More than half of the contributors, including members of the Cabot, Derby, Pickman, and Dodge families, purchased furniture from Nathaniel over the next few years.[6]

Gould’s Daybooks and Account Book

Nathaniel Gould recorded his work and financial transactions chronologically in daybooks. Most of his entries involve the sale of furniture and other goods, including wood, hardware, sugar, fishing line, cloth, and spirits. Gould made many entries daily, but in some instances he grouped transactions, leaving gaps of as much as three weeks. After a customer had settled his or her account, Gould either drew a line through the entry or designated it paid with the abbreviation “pd” (fig. 3) or two angled lines in the left-hand margin. For credits and debits he used the abbreviations “Cr” and “Dr” respectively (fig. 4).

Gould was as meticulous in recording his transactions as he was in making his furniture. He and his workmen listed each item purchased by a patron separately, even in commissions involving multiple objects. Gould’s pricing for generic furniture forms is often discernible, as in the August 25, 1770, entry for Salem merchant Clark Gayton Pickman (fig. 3). Each of the latter’s tables cost 13s. 4d. per linear foot. Like most of his contemporaries, Gould offered standardized furniture forms with options like “carved feet” (fig. 5) and “carved backs” (chairs) available at extra cost. Because Gould’s prices changed little from the late 1750s to the Revolution, one can draw conclusions from entries that are not particularly descriptive. If a four-foot table and “mahogany four foot table” have equivalent prices, it is reasonable to assume that both were made of the same wood. The sheer volume of work produced in Gould’s shop makes such speculation even more plausible. His workforce appears to have grouped orders for certain forms to expedite production and avoid repetitive setups for cutting stock and joints, turning, finish work, and other tasks.[7]

Understanding Gould’s business would be difficult without his account book. With entries from February 1763 to 1781, it covers the period of the missing daybook (April 1763 to December 1767). The account book only lists items sold on credit, whereas the surviving daybooks document all sales but have few credit entries. By correlating the information in these records, one can identify the sources of sugar and other goods Gould sold, the ship captains who provided him with mahogany, the merchants who furnished his furniture hardware, and the cabinetmakers to whom he subcontracted work.

Gould specialized in the production of several different forms. During the years covered by his surviving daybooks and account book, he sold 1,144 chairs, 321 conventional table forms, 441 desks, 196 bedsteads, 76 “cases of drawers,” 52 “bureau tables,” 17 “chamber tables,” and 19 desk-and-bookcases (total includes an entry for “1/2 desk-and-bookcase”). Side chairs, usually offered in sets of six, accounted for most of the seating produced in his shop; however, Gould also made round, close-stool, and easy chairs. His production of seating is surprising, since chairmaking tended to be a specialized trade in New England. Salem chairmakers who were contemporaries of Gould included William Lander, William Gray, and Benjamin Symonds.[8]

The tables listed in Gould’s daybooks were described as “round,” “square,” “card,” “silver,” “sideboard,” “twilight” (toilet), “breakfast,” “tea,” “chaney” (china), “riting” (writing), and “side.” The term “chamber table” probably referred to a cabriole-leg case form, whereas the term “bureau table” almost certainly denoted a four-drawer chest (figs. 6, 7). The average price Gould charged for a “case of drawers” was too high for a four-drawer chest, suggesting that he reserved that term for a high chest or double chest. On April 15, 1765, Salem tanner Joseph Southwick paid Gould £4.4 for a “case of draws with steps” (fig. 8). Presumably this entry referred to a flat-top high chest with a platform for displaying china or other valuable objects.[9]

One of the most expensive objects made in Gould’s shop was a “case of draws swelled ends” commissioned by Salem merchant John Appleton and completed by July 1767 (fig. 9). New England cabinetmakers used the term “swelled” to refer to bombé, blocked, commode (serpentine), and bowed forms, but only bombé shaping was appropriate for the sides of a case. Valued at £17.6.8, Appleton’s chest probably resembled the example illustrated in figure 10. Gould charged the same amount for cases of drawers sold to Mark Hunking Wentworth of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on November 22, 1764, and Rebecca Orne of Salem, on August 1, 1768, before her marriage to merchant and shipowner Captain Joseph Cabot. This suggests that those examples were also of bombé form.[10]

Equally demanding from the perspective of construction were desk-and-bookcases. Of the nineteen examples listed in Gould’s daybooks, six were shipped elsewhere: two to Salem shipmaster Joseph Grafton; one to Marblehead, Massachusetts, merchant Jeremiah Lee; one to Marblehead shipmaster Nicholas Bartlet; one to Beverly shipmaster Josiah Batchelder; and one to Philadelphia minister and merchant Peletiah Webster. The prices charged for five of these desk-and-bookcases were significantly less than those of other examples made in Gould’s shop. Lee’s desk-and-bookcase is the exception. An April 9, 1775, entry in the cabinetmaker’s daybook (fig. 11) indicates that Lee purchased seven pieces of furniture including the desk-and-bookcase and was assessed additional charges for crating each. The corresponding entry in Gould’s account book (fig. 12) reveals that Lee purchased the furniture for his daughter Mary (1753–1819) and her husband, Newburyport merchant Nathaniel Tracy (1751–1796). The couple had married one month earlier, which suggests that the furniture commissioned by Lee was part of his daughter’s wedding dowry (fig. 13). Most of the individuals who purchased desk-and-bookcases from Gould were members of Salem’s merchant elite, including Edward Allen, Joseph and George Cabot, George Deblois, Francis Gardner, Benjamin Goodhue, Thomas Mason, and Richard Routh.[11]

Of all the furniture forms listed in Gould’s daybooks, desks appear to have contributed the most to his financial success. Notations regarding charges for “casing” (crating), sales to ship captains, and the use of cedar as a primary wood suggest that at least three-quarters of the desks he sold were intended for export. Gould purchased most of these examples from local cabinetmakers. On June 23, 1768, Philemon Parker charged him £1.4 for a desk that Gould sold for £4 the same day (fig. 14).

Gould’s shop produced a variety of stands, one hundred of which were described as “standtables.” That term probably referred to the square or round tilt-top tea tables with baluster or urn-shaped pillars and simple cyma-shaped legs. Many examples of this form survive from the North Shore of Massachusetts. More specialized variants from Gould’s shop included reading, glass, bottle, and candlestands.

Identifying the Work of Nathaniel Gould’s Shop

For nearly twenty years scholars have debated the authorship of an imposing desk-and-bookcase bearing the inscription “Nath Gould not his work” (figs. 15, 16) and other case pieces with similar structural and stylistic details. In American Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art II, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (1985), furniture historian Morrison Heckscher speculated that the desk-and-bookcase was from Gould’s shop and that its unusual inscription may represent the sentiments of a disaffected workman who made the object and did not want his master to receive undue credit. Heckscher also referred to an additional eighteenth-century inscription—“Jos—— Gould 177_”—and noted that the design of a block-front desk marked “H x RUST” (figs. 17, 18) was similar to that of the desk-and-bookcase. Since the early 1970s that desk had become a cornerstone for attributing other case pieces to Salem and some examples to the shop of Henry Rust. Indeed, decorative arts scholar Charles Venable argued that the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 15 was made by Rust after comparing its construction to that of the desk marked “H x RUST” and another example inscribed “This desk Made By Henry Rust of Salem / Salem New England / One Thousand seven Hundred and Seventy” (figs. 19-21).[12]

Venable’s attribution of the desk-and-bookcase (fig. 15) to Rust can be refuted on several points. Although the desk marked “H x RUST” is attributed to the same shop that produced the desk-and-bookcase, evidence suggests that the chiseled inscription on the former is not a maker’s mark. The construction of the other desk (fig. 19), which has an authentic inscription, differs significantly from that of the desk-and-bookcase. This is most apparent in the dovetailing of their drawer sides and backs, since the pins and tails on the desk are the reverse of the more conventional ones on the desk-and-bookcase (figs. 22, 23). Similarly, the desk-and-bookcase has lap-joined backboards, whereas those on the desk are butt-joined. Other structural features cited by Venable as evidence that these pieces originated in the same shop are generic. The glue blocks supporting the feet and drops on the desk-and-bookcase and desks are essentially the same as those used by Salem cabinetmakers Abraham Watson and John Chipman, and double-beaded drawer edges are common in furniture from Salem and Marblehead, Massachusetts, as well as other areas of New England. Venable also erred in concluding that the writing on the desk-and-bookcase and desk illustrated in figures 15 and 19 was “by the same hand.” The inscription “Nath Gould not his work” is actually by two different individuals (fig. 16), and the “Nath Gould” section matches the cabinetmaker’s signature on the title page of his account book (fig. 1) and an invoice to Salem merchant Richard Derby (fig. 24). The fact that the phrase “not his work” is by a different hand supports Heckscher’s theory that it was written by one of Gould’s workmen. The cursive style of both inscriptions (fig. 16) differs from that on the desk illustrated in figures 19–21.[13]

The construction of case furniture attributed to Gould and other Salem cabinetmakers differs from that of their Boston counterparts. All but two of the case pieces attributed to Gould have claw-and-ball feet with side talons that are vertical rather than being raked back in Boston fashion (fig. 25). His feet are further distinguished by having toes that are almost square in cross section and talons that are undercut slightly on the sides. Gould’s secondary woods are generally knot-free and scraped smooth, whereas those in many Boston case pieces display saw kerfs or rough plane marks. His drawer sides and backs are typically 3/8–1/2 inch thick, which provided ample surface for a widely spaced double bead at the top (fig. 26). Most Boston and Salem cabinetmakers limited their beading to the tops of drawer sides. Gould and his workmen constructed their large drawers with the bottom boards set parallel to the front. This practice, which had become common in Salem by the middle of the eighteenth century, differed from the perpendicular arrangement favored by most Boston cabinetmakers. Only in the precision of dovetail joints does Boston casework surpass that associated with Gould’s shop. The angles of his pins and tails are often asymmetrical, and his dovetails occasionally have gaps between the joints.[14]

Gould’s work can be separated from that of other Salem cabinetmakers, although not by any single diagnostic detail. Like all large urban furniture-making shops, he had a sizable workforce composed of apprentices and journeymen with slightly different work habits. Variations can be observed from piece to piece, but Gould’s casework is structurally consistent when evaluated as a group. The prospect doors of his desk-and-bookcases are cut from a solid block of wood; he used square blocking on the lids and top drawers of blocked case furniture; the hinges of his prospect doors and lock faces of his desk lids are surface mounted (fig. 27); his pigeonhole valences have exceptionally vigorous cyma curves (fig. 28); his drawer dividers and fallboard supports are made of mahogany rather than having mahogany faces glued to white pine boards; and the numbering system he usually employed on large exterior drawers is distinctive (fig. 29).

An exceptional bombé desk-and-bookcase (fig. 30) can be attributed to Gould based on its provenance and stylistic and structural parallels with other furniture from his shop. Oral tradition maintained that the desk-and-bookcase descended in the family of Robert Treat Paine II (1861–1943) and his wife, Ruth (Cabot) Paine (1865–1949). Ruth and her husband shared a common ancestor, Joseph Cabot (1719–1767) of Salem. Ruth descended in the line of Joseph’s youngest son, Samuel (1758–1819), whereas Robert descended in the line of Joseph’s eldest son, John (1745–1821).[15]

The Cabots were one of Salem’s leading families during the mid-eighteenth century. Their patriarch was John Cabot (1680–1742), who emigrated from the Channel Island of Jersey to Massachusetts in 1700 and married Anna Orne (1678–1767) in Salem two years later. Four of their seven children married members of the prosperous Higginson family. John’s sons Joseph (1719–1767) and Francis (1717–1786) followed him in the shipping business, which, supplemented by other mercantile activities, was the source of the Cabots’ great wealth.[16]

Members of the Cabot family commissioned five of the nineteen desk-and-bookcases listed in Gould’s daybooks (fig. 31). Joseph and Francis purchased the first example for their business in March 1765. That desk-and-bookcase may have been used in the brothers’ office and warehouse on Essex Street in Salem and probably remained there until Francis’s death in 1786. His inventory lists two examples. Three of Joseph’s children also purchased desk-and-bookcases from Gould. His son Andrew commissioned two, the first for £24 on May 18, 1773, and the second for £40 on April 6, 1780. Andrew’s brother George paid Gould £20 for a desk-and-bookcase on March 26, 1774, shortly after marrying Elizabeth Higginson (1756–1826). Seven years later, Gould charged Francis Cabot Jr. £45 for a desk-and-bookcase. At that date, the cabinetmaker’s patron was only twenty-four years old. While it is impossible to determine which Cabot commissioned the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 30, Andrew clearly had a taste for bombé furniture. He paid Gould £12 for a “bureau table” on February 24, 1781 (figs. 6, 7), three months before purchasing his second desk-and-bookcase.[17]

Like the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 15, the Cabot example is made of dense, highly figured mahogany. Although Gould sold large quantities of wood to other Salem cabinetmakers, he reserved some of the best material for his own use. The fallboards on all of his surviving desk-and-bookcases appear to have been cut from the same board (fig. 32), which is remarkable when one considers that the production of these case pieces probably spanned six to ten years. Gould or his workmen oriented each fallboard so the stripe figure drops from one upper corner and rises to the other. Furniture from his shop is distinguished both by the quality of the materials used and the attention given to grain pattern. On the Cabot desk-and-bookcase (fig. 30), the grain of the tympanum board echoes the shape of the upper door rails and panel arches beneath (fig. 33).

The construction of the desk-and-bookcases is nearly identical save for the dimensions of some parts, including foot brackets and drops, and the dovetailing of their lower exterior drawers. Surprisingly, Gould does not appear to have used patterns for transferring the design of such components from piece to piece (fig. 34). As these desk-and-bookcases suggest, most of the major case pieces attributed to him appear to have been commissioned rather than purchased from Gould’s stock-in-trade. Concerns for strength apparently led Gould to reverse the pins and tails on the backs of drawers with sides curved to accommodate bombé shaping (fig. 35). The joints of drawers with curved sides and a conventional pin-and-tail arrangement were more likely to separate if the drawers were heavily loaded.[18]

The fastidious construction, superb materials, and exceptionally refined design of Nathaniel Gould’s furniture set it apart from that produced by many of his Massachusetts contemporaries. Other Salem cabinetmakers copied some of his shop’s details, including the scallop shell drops and pinwheel rosettes seen on furniture illustrated here, but few possessed comparable skill and business acumen. Although he died at the relatively young age of forty-seven, Gould’s furniture and the daybooks and account book he left behind illuminate the career of one of Salem’s finest and most successful craftsmen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the authors thank Judy Anderson, Elizabeth Barker, Sidney E. Berger, Allan Breed, Darren J. Brown, John D. Childs, Wendy A. Cooper, Peter Drummey, Sean Farrell, Katherine Flynn, Catherine Futter, Nonnie Gadsden, Katherine Griffin, Elaine Grublin, Stephen P. Hall, Morrison H. Heckscher, Brock Jobe, Frank Levy, Robert Lionetti, Christine Michelini, Robert D. Mussey Jr., Richard Nylander, Clark Pearce, Clarence, Craig, and Todd Prickett, and Gerald W. R. Ward.

Debit entry for Samuel Archer Jr., May 1, 1758, Nathaniel Gould Daybook, 1758–1763 (hereafter cited as NGDB 1), Nathan Dane Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. A book listing the complete furniture transactions of Gould and his relationships with other cabinetmakers is planned for future publication.

NGDB 1; and Nathaniel Gould Daybook, 1767–1784 (hereafter cited as NGDB 2), Nathan Dane Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. Nathaniel Gould Account Book, 1763–1781 (hereafter cited as NGAB), Nathan Dane Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

Nathaniel Gould Sr. was described as a “joyner” in several land transactions. See Ebenezer and Deliverance Marsh to Nathaniel Gould, June 17, 1727, Essex County Deeds (hereafter cited as ECD), vol. 46, p. 202. Also see Daniel Cariel and wife Mary to Nathaniel Gould, November 6, 1729, ECD, vol. 53, p. 184; and Probate Records of Essex County, Massachusetts (hereafter cited as PREC), January 1, 1746/47, docket no. 11415.

Nathaniel Gould of Charlestown, cabinetmaker, to John Clammons, December 25, 1756, ECD, vol. 104, p. 61. Robert Mussey and Anne Rogers Haley, “John Cogswell and Boston Bombé Furniture: Thirty-five Years of Revolution in Politics and Design,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University of New England Press for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), p. 100. Debit entries for Thomas Wood, January (no date given), June 1, and November 6, 1761, NGDB 1. Other sales are interspersed throughout Gould’s daybooks and account book. For an example of Gould’s purchases from Wood, see the credit entry in NGAB for March 23, 1766, for the purchase of 200 ft. cedar timber, 150 ft. cedar boards, and 16 cedar desks.

For more on Cogswell, see Mussey and Haley, “John Cogswell,” pp. 73–107. Credit entry for John Cogswell, June 1759, NGDB 1.

James Duncan Phillips, Salem in the Eighteenth Century (Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1969), pp. 204–10. The amount Gould donated was equal to more than three weeks’ wages for a journeyman cabinetmaker. Gould paid Thomas West 22s. 6d. for seven days’ work. Credit entry for Thomas West, March 1759, NGDB 1.

For furniture with carved feet, see debit entry for Jonathan Very, November 30, 1768, NGDB 1. For “chair frames carved backs,” see debit entry for Clark Gayton Pickman, August 25, 1770, NGDB 2 and fig. 3. For the tables, see debit entries for Caleb Foster, May 27, 1774, NGDB 2, and Peter Frye, December 24, 1774, NGDB 2.

For more on Salem chairmakers, see Benno M. Forman, “Salem Tradesmen and Craftsmen Circa 1762,” Essex Institute Historical Collection, no. 107 (January 1971): 65.

Inventories provide additional evidence that the term “bureau table” in the Gould daybooks and account book referred to four-drawer chests. In August 20, 1772, Gould sold Marblehead, Massachusetts, merchant Jeremiah Lee one mahogany “bureau table,” one walnut “bureau table,” one mahogany “case of drawers,” one walnut “case of drawers,” one “silver table,” and thirty-six chairs. Debit entry for Jeremiah Lee, August 20, 1772, NGDB 2. The account book indicates that this order was for his son (fig. 12). The 1785 inventory of Lee’s son Joseph listed “one mahogany bureau and one mahogany chest-on-chest in the first floor bedchamber and one walnut bureau and one walnut chest-on-chest in the second floor bedchamber.” Inventory of Joseph Lee, October 4, 1785, ECPR, docket no. 16625, transcript book 358, p. 45. Debit entry for Joseph Southwick, April 15, 1765, NGAB.

Debit entry for Mark Hunking Wentworth, November 22, 1764, NGAB. Debit entry for Rebecca Orne, August 1, 1768, NGDB 2. For evidence that the term “case of drawers” in the Gould daybooks and account book referred to chest-on-chests and cabriole-leg high chests, see the references to Jeremiah and Joseph Lee in n. 9 above. Four-drawer bombé chests attributed to Gould’s shop are in the collections of the Marblehead Historical Society, Historic New England, Winterthur Museum, Bayou Bend, and a private collector. For a “bureau table swelled,” see debit entry for Bartholomew Putnam, May 1781, NGAB.

Debit entry for Joseph Grafton, March 13, 1761, NGDB 1. Debit entry for Jeremiah Lee, April 9, 1775, NGDB 2. Debit entry for Nicholas Bartlet, September 24, 1765, NGAB. Debit entry for Josiah Batchelder, May 2, 1765, NGAB. Debit entry for Peletiah Webster, July 1774, NGAB. John L. Currier, Old Newbury Historical and Biographical Sketches (Boston: Damrell and Upham, 1896), pp. 551–64.

Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art II, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Random House, 1985), pp. 121–24, 192–95. Margaretta Markle Lovell, “Boston Blockfront Furniture,” in Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, edited by Walter Muir Whitehill (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1974), pp. 121–30. Charles L.Venable, American Furniture in the Bybee Collection (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), pp. 58–68. Israel Sack, Inc., Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, 10 vols. (Alexandria, Va.: Highland House, 1981), 4: 898–99.

The “H x RUST” mark on the desk illustrated in fig. 17 may have denoted ownership rather than authorship; however, no individual by that name is listed as a patron in Gould’s account book or daybooks. On February 7, 1775, Gould recorded a debit entry for Henry Rust for work performed by Ipswich joiner Stephan Lowater. Gould had paid Lowater twenty-four days’ wages (at 3s. 4d. per day) for sawing cedar boards. NGDB 2. Invoice from Nathaniel Gould to Richard Derby, Salem, Massachusetts, November 21, 1763. Derby Papers, Miscellaneous Receipts, MSS 37, box 15, folder 5, Peabody Essex Museum. For more on Chipman’s blocking, see Peter A. Louis and Donald R. Sack, ”John Chipman: Cabinetmaker of Salem, Massachusetts,” Antiques 132, no. 6 (December 1987): 1320.

Some of Gould’s construction details are similar to those of his Boston counterparts. The lower drawers of Gould’s case pieces ride on strips of wood glued to the case bottom, and the tops of his chests are attached to the sides with sliding dovetail joints.

For more on the Cabot family, see L. Vernon Briggs, History and Genealogy of the Cabot Family, 1475–1927 (Boston: Charles E. Godspeed & Co., 1927), pp. 44–55.

Ibid., pp. 99–107, 167–69, 185–86, 194–96.

Debit entry for Joseph and Francis Cabot, March 1765, NGAB. Debit entry for Andrew Cabot, May 18, 1773, NGDB 2; and debit entry for Andrew Cabot, April 6, 1780, NGDB 2. Andrew bought the first desk-and-bookcase three weeks after marrying Lydia Dodge (1748–1807). He commissioned the second shortly after moving to Beverly, Massachusetts. Andrew’s 1791 inventory lists one “desk & bookcase” valued at £7.10 and another valued at £4.10. ECPR, no. 4431, bk. 360, pp. 499–506. His wife, who was pregnant with their ninth child when he died, moved to Boston in March 1792. Auctioneer William Lang sold one of the two desk-and-bookcases, a mahogany stand table, and thirteen chairs from Andrew’s Beverly house later that year. Salem Gazette, June 12, 1792; and Nathan Dane, Minute Book of Settling Estate of Andrew Cabot (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1935), p. 19. The other desk-and-bookcase was still in Lydia’s house when she died in July 1807. The estate was divided equally between the couple’s children. Suffolk County Probate Records (hereafter cited as SCPR), bk. 105, docket no. 22925, p. 411. Debit entry for George Cabot, March 25, 1774, NGDB 2. The disposition of George Cabot’s desk-and bookcase remains a mystery. He gave cash to his son and daughter and established trust funds for his wife, Elizabeth. She received the balance of his estate and later bequeathed everything to her son Henry (1783–1864). SCPR, bk. 121, docket no. 26951, p. 336; and SCPR, bk. 123, docket no. 28045, p. 79. Debit entry for Francis Cabot Jr., August 1781, NGDB 2. Two years after the death of his wife, Nancy (1761–1788), Francis Cabot Jr. left his three children in the care of relatives and moved to Philadelphia. He subsequently relocated to Louisiana, enlisted as a private in the battle of New Orleans, and died in Natchez, Mississippi. His desk-and-bookcase may have been among the “Genteel and Valuable House Furniture and Shop Goods” Francis sold in September 1790. Debit entry for Andrew Cabot, February 24, 1781, NGDB 2.

The dovetailing on the chest in the Winterthur Museum and the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30 differ from that of other bombé furniture attributed to Gould’s shop. On these examples, the pins and tails at the rear of all the drawers are reversed.