Detail from “Spanish North America, Southern Part,” (John Thomson, A New General Atlas [Edinburgh: John Thomson and Co., 1817].)

Chest attributed to the Symonds shops, Salem, Massachusetts, 1701. Oak, maple, mahogany, and red cedar (by microanalysis). H. 31 1/4", W. 47 3/4", D. 20 5/8". (Courtesy, Concord Museum, Concord, MA, gift of Russell Kettell; photo, David Bohl.) The dated panel is mahogany.

Chest-on-chest possibly by Abraham Watson (1712–1790), Salem, Massachusetts, 1760–1770. Mahogany with white pine. H. 90", W. 44", D. 23". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum Collection, R1120, bequest of Sarah Cheever, 1908.) Watson may have made this chest for Judge Nathaniel Ropes in exchange for unfinished mahogany.

Desk attributed to William King (b. 1754), Salem, Massachusetts, ca. 1776. Mahogany with white pine and brass. H. 43 1/2", W. 40 1/4", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum Collection, 101792, bequest of Sarah Cheever, 1908.)

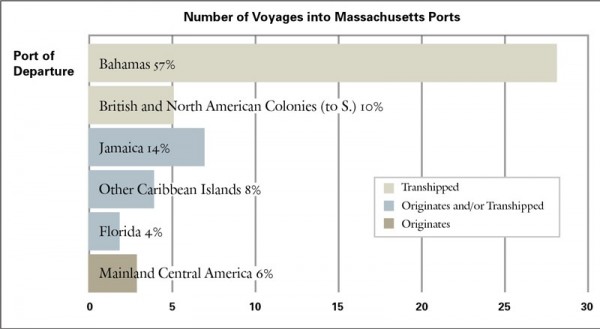

Mahogany Entering Massachusetts Ports, 1752–1765. (Derived from “Abstracts of English Shipping Records,” Peabody Essex Museum.)

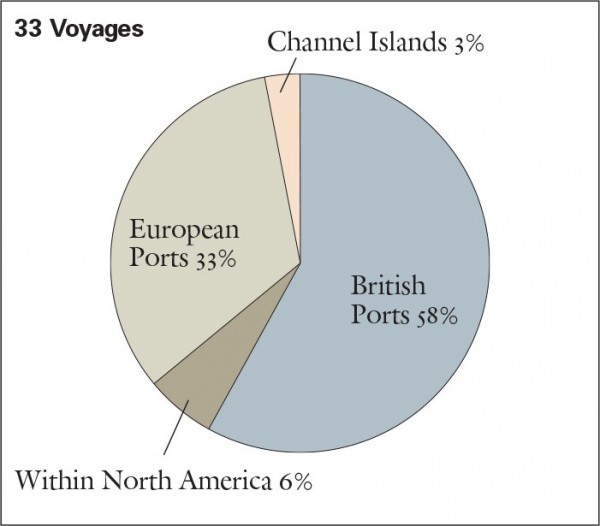

Mahogany Clearing Massachusetts Ports, 1752–1765. (Derived from “Abstracts of English Shipping Records,” Peabody Essex Museum.)

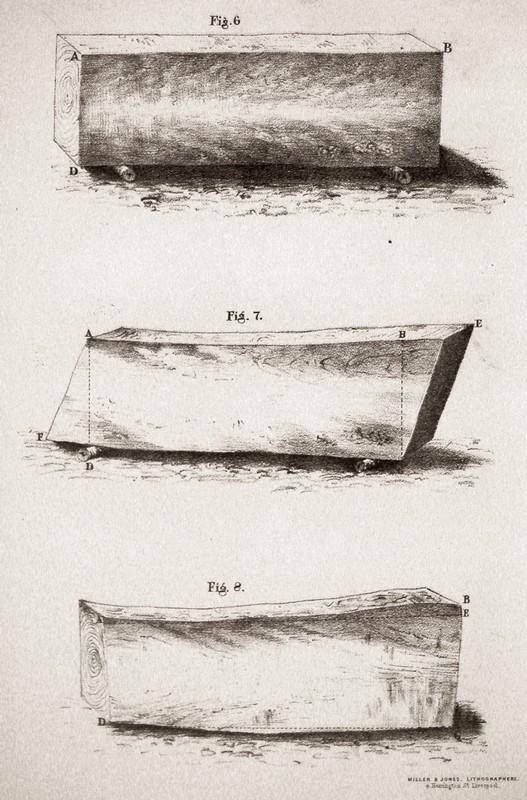

Assessing the contents of a squared log. (Chaloner and Fleming, The Mahogany Tree [Liverpool: Rockliff and Son, 1850].)

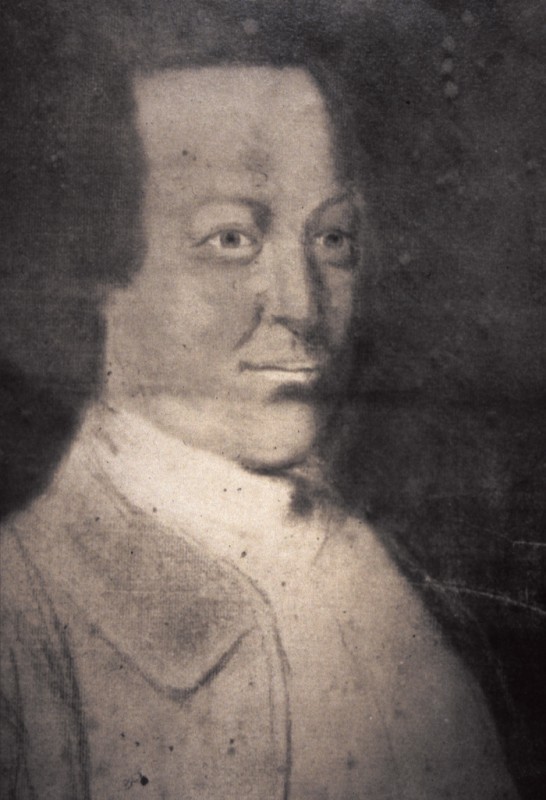

Portrait of Aaron Lopez, unidentified artist. Oil on metal. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, American Jewish Historical Society, New York, NY and Newton Centre, MA.)

Portrait of James Card, unknown artist, medium, and dimensions. (Ex-collection, Rhode Island Historical Society. Current location unknown.)

Detail from “Mexico and Central States,” (Sydney Hall, A New General Atlas [London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1857].)

J. McGahey, Felling Mahogany, Liverpool, England, ca. 1850. Lithograph. 6" x 9". (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.)

Day and Son, Cutting and Trucking Mahogany in Honduras, Liverpool, England, 1850. (Chaloner and Fleming, The Mahogany Tree [Liverpool: Rockliff and Son, 1850].)

Manner of Trucking Mahogany in Honduras, attributed to William B. Annin and George G. Smith after Andrew Bayntun, Boston, 1826. Engraving on paper. 4" x 7". (Honduras Almanack, 1826.)

“Rafting mahogany logs down New River.” (Standley and Record, The Forest and Flora of British Honduras [Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1936], pl. 4. ID #B78614.)

Boom chain of undetermined date retrieved from the lower Belize River at the village of Burrell Boom. (Photo, Daniel Finamore.)

Wedge-shaped end of a squared mahogany log, used to prevent stacks of logs from rolling. (Photo, Daniel Finamore.) The author found this log in the Sibun River near Cedar Bank.

Charles Dashwood, Merchant’s House and Yard for Siding the Mahogany Trees before Putting Them on Board Ship for England, Belize, ca. 1830. Graphite and ink on paper. 10 1/4" x 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.)

Mode of Travelling of the Woodcutters in the British Settlement of Honduras, attributed to William B. Annin and George G. Smith after Andrew Bayntun, Boston, 1828. Engraving on paper. 4" x 7". (Honduras Almanack, 1828.)

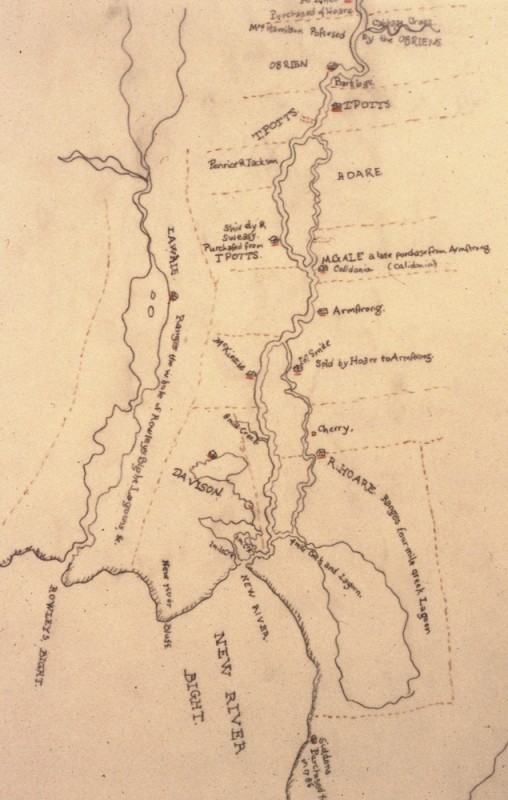

Tracing of a portion of David Lamb’s A Map of that part of Yucatan in the Bay of Honduras allotted to Great Britain for the cutting of Logwood. Ink and watercolor on paper, 1787. The map, which is oriented with north at the bottom, shows Matthias Gale’s Caledonia and the woodcutting claim of Robert Francis O’Brien. Caledonia was located on a wedge-shaped piece of elevated land, flanked on two sides by swamp and on the third by the New River. Densely forested today, it is several kilometers from the modern town of Caledonia. The site was carefully investigated through surface collection within a grid of meter-square units, yielding a large assemblage of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century ceramics, glassware, pipe fragments, and gunflints. O’Brien’s site was discovered thirty-four kilometers south of the New River mouth, in a recently cut sugar cane field on a low ridge running parallel to the east bank. The site contained a thin scatter of artifacts ranging from buff-bodied slipwares of the early eighteenth century to hand-painted pearlwares of the 1810s and 1820s. The site appears to have been occupied longer than most of the others.

Site of Matthias Gale’s woodcutting claim Caledonia. (Photo, Daniel Finamore.)

Base of a pearlware bowl recovered from the O’Brien site. (Photo, Daniel Finamore.) The bowl is inscribed with an “X.”

I have read that the old Druid Priests taught the early Britons that if they cut the oak tree the spirit, which possessed its form, would cry out in protest; and as one sees the slaughter of those beautiful trees, one can almost imagine the spirits of the woods crying out in protestation against the ruthless destruction of tree-life. It is certainly a consolation to remember that the tree which is being robbed of its leafy bounty is destined to re-appear in a form where beauty and utility will combine. What an interesting story could be written on “The Romance of the Mahogany Log,” relating its experience from its growth in a distant forest to its place of honour in a city mansion.[1]

Lore and History

In the mid-1950s an unfinished mahogany plank measuring nine feet long by five feet wide by two and one half inches thick was discovered in the basement of a house in Salem, Massachusetts. The board had been used as a coal chute, but it still displayed the fiery, highly desirable grain pattern that forms on the trunk near the crotch of a branch. Clearly harvested from a very large, first-growth mahogany tree, this plank sheds light on the size of boards and billets that reached New England ports during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and provides a tantalizing glimpse into a trade that has gone little examined in the literature of decorative arts and maritime history. At the same time, the plank’s intrinsic qualities provide little information as to its origin, extraction, processing, and transportation. Also difficult to ascertain is the human cost of the mahogany trade, since much of the labor that sustained it required the movement of populations over great distances, often against their will. With a deeper perspective on the processes that culminated in the delivery of wood to the craftsman’s shop, mahogany furniture becomes central to the hegemonic discourse of the English slave-owning culture in the New World.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, ships transported large quantities of mahogany to and from many countries bordering on the North Atlantic. Because quantitative documentation of this trade has proved elusive, studies of furniture making typically begin in cabinetmakers’ shops with the assumption that they had planks and other stock on hand. In their formal analyses, scholars typically identify the mahogany used in furniture arbitrarily as Jamaican, Honduran, Santo Domingan, or Cuban, through macroscopic visual assessment of color and physical appearance of grain. By incorporating this kind of questionable connoisseurship, furniture historians mythologize the exotic origins of the wood while further obfuscating the specific histories of the people and places of the mahogany trade.[2]

This essay combines historical and archaeological research to investigate in reverse sequence selected aspects of the process by which a living tree became an article of furniture. No single source offers a seamless chronology of data about the disparate and often little-documented phases of production, but each interpretative approach offers distinct insights that create a more holistic perspective than would be available from a single source alone. Sources utilized for this study include furniture that retains documentation or oral tradition regarding wood origins, archives with holdings pertaining to geographic, economic, and social factors of the mahogany trade, and the physical remnants of remote Central American forest encampments that contain artifacts of lives where subjugation was the norm and a voice in the archives is rare.

Though mahogany was harvested from around the Caribbean basin, research for this article focuses on the nation of Belize (fig. 1), which was known in the eighteenth century as the Bay Settlement, or simply Honduras, and from 1862 to 1973 as the colony of British Honduras. Belize is an ideal case study for the history of the mahogany trade because it existed for more than one hundred years as an informal British colony in a region claimed by Spain for the sole purpose of extracting wood for export. As a result, neither residents nor governments invested in political, social, or physical structures beyond those necessary for the efficient extraction and exportation of wood.[3]

Mahogany began entering English ports during the seventeenth century (fig. 2), but it was not widely used as a primary wood for cabinetmaking before the 1730s. Lore regarding the origins of the mahogany trade emphasizes the accidental nature of the wood’s discovery, maintaining that mariners picked up entire trunks for use as ballast only to toss them overboard on arrival home, where they were “free for the taking” by cabinetmakers scavenging wood from the foreshore. The enormous size and weight of trees that would offer optimal timber for cabinetmaking and the significant amount of labor required to harvest, prepare, load, and unload the wood from a ship strongly suggests that the use of mahogany in furniture of this era was never accidental. A 1737 advertisement in the Boston Gazette announced the sale of “Ligmimviree, Box Wood, Ebony, Mohogony Plank, Sweet Wood Bark, and wild Cinnamon Bark,” indicating that early on mahogany was a valuable commodity.[4]

Among the remarkably comprehensive array of furnishings, decorative arts, and documents relating to more than 150 years of business and daily life in Salem that make up the Ropes Family Collection at the Peabody Essex Museum is the account book of Judge Nathaniel Ropes. In an undated entry, he gave cabinetmaker Abraham Watson 60 feet of mahogany in exchange for £18, a “desk and caseing,” and possibly other furniture made from that wood (fig. 3). The judge may have acquired the mahogany through maritime trade or as payment for a debt owed locally, but there is no evidence that he imported wood as a business. The most likely scenario is that Ropes acquired the mahogany specifically to buy furniture at a savings. Transactions of this type were common during the period. From 1757 to 1759 Newport ship captain Joseph Arnold supplied cabinetmaker John Cahoone with 243 feet of mahogany and 13 feet of walnut in exchange for a desk and four tables. Arnold received these items over time and probably sold them as venture cargo.[5]

In some instances, the importer was also the end user of the wood. Generations of oral tradition maintain that the desk illustrated in figure 4 was part of ship captain James Chever’s “wedding outfit” that he had made from Santo Domingo mahogany he had “brought home.” Since Chever married in 1776, it is possible that the disruption of trade during the Revolutionary War had created a shortage of mahogany in Salem. Alternatively, he may have had access to better-quality wood at Hispaniola than what was arriving at Salem at the time. Chever may have saved a good deal of money by buying the mahogany at its source, rather than purchasing the best wood available in Salem. Decorative arts historian Dean Lahikainen has shown how several prominent Salem cabinetmakers formed a cartel to buy large quantities of mahogany logs, which were cut into planks locally. One of these artisans, Josiah Austin, also served as the surveyor of boards, plank, and timber for the town in 1799. By importing his wood directly from the source region, Chever may have circumvented competition from organized local interests to acquire better wood at a more reasonable price.[6]

Repositioning Wood: Transshipment and Regional Variation

The name “mahogany” is now used liberally to describe a variety of species in the Meliaceae family that grow in Africa, India, the Philippines, and elsewhere, but the historical range of the three species that constitute true mahogany is neotropical America from southern Mexico and the southern tip of Florida, into South America including much of the Amazon basin, as well as most of the Caribbean islands. Within this genus (Swietenia) there is considerable variability in density, color, and grain. Mahogany from well-drained, hilly, or rocky regions, particularly on the West Indian islands, has traditionally been recognized as slower growing, harder, and more figured—all qualities that cabinetmakers found desirable. Mahogany of the Central and South American mainland, and in particular the Caribbean coastal plain, was traditionally believed to grow slightly more rapidly, be somewhat softer, and have a more uniform grain. These qualities were considered to be the result of different growing conditions; not until 1886 were the trees from these two regions separated into different species.[7]

Historic terms that were geographic in allusion—“Jamaican mahogany,” “Spanish mahogany,” and “Honduras mahogany”—may also have referred to qualities perceived as characteristic of the wood from each area. However, the accuracy of such generalizations was often problematic at best. In 1802 New York cabinetmaking firm Samuel and William S. Burling reported that it had “on hand . . . at their mahogany-yard, St. Domingo, Cuba, [and] Bay Mahogany, in Logs, Plank, and Boards.” Although cabinetmakers and lumber merchants used geographic terms for marketing, buyers were more concerned with the visual and physical characteristics of mahogany than with the origin of the wood. As early as 1757 a resident of the north coast of Honduras, then called the Mosquito Shore, speculated about the perceived superiority of Jamaican mahogany over Honduran:

The reason probably is that what is now got in that island, grows in dry rocky ground, where it has been preserved to the last by the Difficulty of transporting it, and for want of soil is of a slow growth and close grain; but here it has been cut for convenience in low land near to the water side from which situation its growth is quick, and its grain open; but some cut on the high land is as good as any.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Jamaican mahogany was becoming scarce, and wood from other areas was too diverse to be indisputably associated with the highest quality. One importer noted that “Instances are not uncommon where a single ton increases the value of a whole cargo £500 and Mahy from the coast of Yucatan may be quoted from £6 to 100£/ton.” In the end, the quality of the wood rather than the region of growth dictated price. Notwithstanding the obvious fact that high-quality mahogany was valued and sought out by certain consumers, the wood was only a relatively small component of the overall cost of furniture, the majority being the maker’s labor. An advisor to the British Parliament in 1790 claimed, “It is of very little consequence to the community whether the manufacturer pays 15 or 2/6 per ft. for fine mahy because experience has shown that the price of fine furniture will be the same, it consisting not so much in the wood as in the finishing.” The desire to generalize about wood from different regions extended even to small-scale topographic distinctions, but an advisor to the British government who visited Belize noted the difficulties inherent in such assumptions. “The Mahogany in this country differs considerably in grain, & consequently in durability, according to the soil on which it grows, and contrary to almost all other countries, the lower and more swampy the soil, the harder and closer grained the wood.”[8]

The quantities of mahogany that entered North America in the eighteenth century will never be comprehensively accounted for, since the wood was loaded onto ships and recorded by shipmasters, merchants, and custom officials in many different forms: logs, log ends (short parts cut from a long log to fit into a hold), slabs, planks (probably thick and hand-shaped or cut in a saw pit), boards (thinner and probably cut at a sawmill), and pieces. Wood was recorded by weight, by the number of pieces, or by using a formula to determine board feet. The variability in reporting the volume of cargos renders quantitative analysis of imports and exports problematic. On October 2, 1764, the schooner Speedwell returned to Boston from a voyage to Puerto Rico, where she took on “218 pieces” of mahogany. Three years earlier the Bahamian-registered brig Harriot had arrived carrying three logs from New Providence, while on October 31, 1752, the Boston sloop Sparrow arrived from that port carrying 1,500 feet of wood in an unidentified state.[9]

Between late October 1752 and the end of September 1765, forty-nine ships carrying indeterminate quantities of mahogany arrived at Boston from New Providence, St. Thomas, Florida, Jamaica, the Mosquito Shore, Puerto Rico, Honduras, North Carolina, and New York. Additional shipments arrived at Salem from Jamaica, Maryland, South Carolina, and St. Eustatius. Of these ports, many are outside the region of mahogany growth, and others, though within it, were not commercial centers of extraction and export. These shipments could represent export from the source or transshipment of wood from a third location. Only a relatively small number of ships appear to have carried wood directly from the originating port into Boston and Salem. When specified, the state of the wood reported in a given shipment indicates whether it was a direct import from its origin or a transshipment from another port. Wood that arrived in board form had probably been processed for sale elsewhere, since most ports of origin, such as Belize and the Mosquito Shore, did not have sawmills, and their wood was exported exclusively in unfinished form, primarily as logs. It was common to transship wood through intermediate points, where it would sometimes be cut and then reloaded to ship out again.[10]

Surviving shipping records for colonial Massachusetts ports (fig. 5) suggest that most mahogany arrived there through multistaged voyages. Most of the cargos that specified the form of the wood stated it as planks, and only one was said to contain logs. Over half of all voyages originated at New Providence in the Bahamas, an island group within the zone of mahogany growth but far too small to have been the sole source of such large quantities of wood. This port served as a primary center of transshipment because it offered convenient access to Atlantic traders entering and departing the Caribbean. Wood was also transshipped through smaller Caribbean islands as well as through British colonies to the south. Localities such as Jamaica acted both as primary extraction centers and transshipment points. Only a small percentage of wood can be said with confidence to have arrived directly from its source of extraction. With no record of a single importation of mahogany from Santo Domingo during these years, it even is possible that Captain Chever’s later voyage was not to that island but to a transshipment center, where he may have had his choice of wood from a number of sources. His destination could even have been New York, where in 1797 George Shipley advertised “a cargo of choice St. Domingo Mahogany, very suitable for the French or English Market.”[11]

Massachusetts was not the final destination for much of the wood that entered the colony’s ports (fig. 6). In January 1764 the Boston brig Katey departed for Europe with a cargo of 183 mahogany logs and 673 mahogany planks. To sell the wood to best advantage, the shipmaster probably intended to visit several ports along the Atlantic coast or Mediterranean. That same year the Salem snow-rigged ship Jenny cleared customs and departed for the Isle of Jersey with 5,000 “boards & planks,” plus 52 additional feet of plank. Between 1752 and 1765 thirty-three ships cleared outward from Boston and Salem customhouses. Most of these vessels headed for the British Isles, but one-third were bound for the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal. An exceptionally large cargo of 35,000 boards and planks was destined for Newfoundland.[12]

Transshipping was advantageous for breaking up bulk cargos, preventing markets from becoming inundated, and avoiding excessive duties. Shippers often owed duty on the wood, especially when it was considered a foreign product. Even before mahogany became the primary export of Belize, entrepreneurial shippers of other woods had realized that the indeterminate political status of that settlement allowed them to sidestep the navigation laws and ship directly to New England and European markets since they were not technically traveling from one British colony to another or from a colony to a foreign country. This situation changed in the early 1770s, when the Crown allowed wood shipped from British colonies on British ships to be imported duty free. Custom agents in London understood, however, that wood from other ports was passing through duty-free entrepôts such as Jamaica or the Mosquito Shore. One official reported that port officers “have [wood] . . . viewed by persons who pretend to know the growth [origin] and it requires great firmness to stand out against them.” Naturally, shippers felt that these “specialists,” who assessed duties based on their determination of the wood’s origin, often acted arbitrarily and unfairly. In 1770 London agents claimed that mahogany arriving there on the Rhode Island ship Hero from the Mosquito Shore was actually from Belize and therefore foreign and dutiable because the certificate for the wood did not identify it as “the growth of that place.” “This plan of our officers to make Honduras wood pay custom is owing to an information given by some busy persons. . . . All that came from our own colonies was supposed to be the growth of our colonies till now, and was in consequence admitted custom free.” The notion that the source of mahogany could be identified through visual examination on the London docks was bitterly disputed by the Belize wood merchants.[13]

Though many logs were cut to fit spaces in a ship’s hold, length influenced the desirability and price of wood in furniture making centers. In 1766 the Bristol agent for a prominent Newport, Rhode Island, merchant complained about receiving “very short Pieces [planks], which renders it of very little Value.” Six years later the same agent complained about a shipment consisting of “a great deal of small, rather porus [wood], much shaken, and in general too short—especially the very large loggs—which are four feet shorter than they are coveted to be.” In the initial stage of processing harvested trees, laborers “placed [the logs] in whatever position [would] . . . admit of the largest square being formed, according to the shape which the end of each log presents, and then reduced by means of an axe, from the round, or natural, form, into the square.” To maximize the value of a squared log, one had to know how to cut it into useful lengths for manufacturing furniture, while minimizing waste. By the mid-nineteenth century, the logs most valuable to cabinetmakers were those that could be used in the manufacture of dining tables, which averaged 4 1/2 to 5 1/2 feet in length, and 22 to 30 inches wide. Logs that were even multiples of these lengths—5, 10, 15, or 20 feet plus or minus a few inches—could be cut most efficiently for this purpose. The best logs for chairs were at least 9 feet in length and 15 inches in diameter. Shorter logs of 7 1/2 to 8 1/2 feet could be used for bedposts.[14]

Superficial measurements were only estimates. Even after a log cleared customs, it was not possible to determine its exact monetary value, whether in board feet or quality of wood, until it was fully cut (fig. 7). Sales of logs were based on estimates of the usable wood they would produce. In 1843 Belize wood merchant Charles Craig reputedly had a log that weighed fifteen tons, measured 57 by 64 inches after being squared, and contained an estimated 5,168 board feet of wood. The ultimate job of processing that log and ascertaining the accuracy of those measurements was probably left to a well-financed wood merchant in Liverpool or London. Purchase of raw wood involved a certain amount of speculation, as illustrated by the optimistic assessments accorded one log in an 1823 newspaper account:

The largest and finest log of mahogany ever imported into this country has been recently sold by auction at the docks in Liverpool. It was purchased by James Hodgson, Esq. for three hundred and seventy-eight pounds, and afterwards sold by him for five hundred and twenty-five pounds, and if it open well, it is supposed to be worth one thousand pounds. If sawn into veneers it is computed that the cost of labour in the process will be seven hundred and fifty pounds. The weight at the King’s beam is six tons thirteen hundred weight.[15]

Although enormous logs occasionally generated public attention and could be exploited for promotional purposes, some lumber merchants felt that large logs yielded inferior timber. In 1771 Henry Drinker of Philadelphia complained to his Central American supplier: “We have repeatedly observed that you seem to set a high value on the largest wood which is in general a mistaken notion because it is not in common so good in quality as middle size and is larger than the consumers of that article generally require.” Drinker requested planks and logs of four, eight, or twelve feet in length and sixteen to twenty-four inches in diameter to conform to the desires of Bristol cabinetmakers.[16]

Americans in the Mahogany Trade

North American cabinetmakers and woodlot operators had no direct contact with ports of origin in the mahogany trade, but that was not the case with shippers whose businesses hinged on relationships with Caribbean and Central American lumber merchants and their agents. Unlike most of their Massachusetts counterparts, who dealt in transshipped mahogany, shippers in Newport, Philadelphia, and New York endeavored to purchase wood as it emerged from the forests of Belize and the Mosquito Shore.

Harvesting and exporting wood typically involved partnerships between the woodcutters who staked claims to forest tracts and managed field operations and the financiers who arranged for the credit necessary to support a workforce and made arrangements for transportation and sale. Thus, both field managers and their agents were central players in the compulsory labor system of the mahogany trade. Immediately following emancipation of the slave population at Belize in 1838, the anticipated cost of operating a mahogany camp capable of producing 300,000 board feet in a seven-month season was £7,001, including labor, tools, trucks, livestock, watercraft, and provisions. Before emancipation, however, the costs would have been similar, owing to substantial investment in slave ownership, or the common practice of “hiring,” or leasing, the slaves of another timber cutter.[17]

Among the most active mahogany traders in colonial America was Aaron Lopez (fig. 8), who immigrated from Portugal to Rhode Island in 1755 and worked with a network of business partners around the Atlantic to become Newport’s most prosperous merchant. Lopez sent many ships to Belize with cargos of goods for forest-dwelling, timber-cutting laborers: barrels of dried and pickled foods, clothing, lanterns, cooking pots, saw blades, axes, and boat compasses. Much of the wood Lopez purchased at Belize was destined for the international market, although some of his mahogany went to Rhode Island via Jamaica. Lopez’s correspondence with his London agent suggests that the mahogany trade was lucrative in good times but frequently subject to market saturation. Caribbean timber merchants were habitually indebted to Lopez, who was forced to accept wood in payment even though his London agent warned him in 1772 that the city had enough mahogany to last ten years. As part of a complex international market, mahogany prices were affected not only by supply and the cost of importing the wood but also by the shifting diplomatic and political landscape of the later eighteenth century. Hurt by the nonimportation acts that were supported by colonists in certain cabinetmaking centers, Lopez’s agent railed against “the Haughty Insolent Overbearing Arbitrary Rebellious Bostonians . . . [and] the Stiff foolish Obstinate Philadelphian Quakers,” but reserved positive comments for the “Wise Good & Spirited” New Yorkers, who he apparently felt struck a balance between commerce and political ideology. At certain times, Lopez’s profits on mahogany shipments were negligible, and it is possible that they were intended only to defray some of the expenses of the west-to-east transatlantic voyage, the majority of profits being made carrying European or North American goods into Jamaica.[18]

Belize was considered a remote corner of the Caribbean, not a destination for speculative voyages. Wood shipments were arranged in advance, since masters wanted to sail there only when they knew full cargos awaited them. As prices for mahogany declined during the 1760s and 1770s, even prominent shipowners became entangled in a growing web of insolvent and untrustworthy partners, undesirable cargos, and unpaid bills, which inspired many to invest elsewhere.

By 1771 Lopez’s mahogany interests were unraveling rapidly, with problems extending well beyond the depressed price of that wood. One of his primary correspondents was John Newdigate, a Rhode Island shipmaster who lost Lopez’s trust after failing in an important venture. As a result, Lopez sent Newdigate to the Sibun River valley of Belize to work off his debt by acquiring high-quality mahogany. In several letters, the banished shipmaster assured Lopez that he had secured large stocks of wood, which were “only waiting for a vessel to take it in.” Newdigate implored Lopez to “send . . . down two vessels to carry it away,” adding, “I want to come home.” In separate letters, Newdigate begged Lopez’s wife to intercede, indicating that his relationship with her husband extended beyond business. These arguments failed to sway Lopez, since he was simultaneously receiving negative reports concerning his former associate. Described as “a . . . weak Headed puffed up foolish fellow” with a head “as soft as a boiled turnip,” Newdigate was accused of adultery, bigamy, misuse of funds, and other offenses.[19]

To make matters worse, Newdigate arranged for the Belize mahogany cutter Basil Jones to travel to Newport on Lopez’s brigantine Charlotte, but the ship struck a reef called “the colloradoes” and had to divert to Charleston, South Carolina, for repairs. Shaken by the incident, Jones called the vessel “unfit for the seas” and insisted on having his wood offloaded. As bills for the ship mounted, Lopez turned to Jones to pay his portion of the freight, but the latter’s wood remained unsold in Charleston, and Jones’s health swiftly declined. Eight months later, Jones died of cancer and Lopez was left to recover the debt from the former’s estate in Belize, which, ironically, was being managed by Newdigate. Whether Newdigate ever repaid his debt to Lopez or Lopez left him in Belize “to repent” of his “former misdeeds,” the disgraced shipmaster eventually escaped his purgatory and resettled in Savanna, Georgia.[20]

Belize woodcutters were at the economic mercy of many distant parties: the shippers who sent vessels to carry away their wood, port agents who measured it for freight and duty charges, and the market that decided its ultimate value. The attempts of one cutter to wrest a modicum of control over these forces illustrate the difficulties of life at that end of the export trade. William Tucker, a resident of the Sibun River valley in the southern portion of the Belize settlement, acquired a brig to ship his own mahogany. He made the ill-fated choice of New York merchant Henry Cruger, whose own business was in decline, to represent his overseas interests. Before Tucker’s ship left Belize, Cruger complained that the “age of the brig Monkton and other defects” made securing insurance difficult. Tucker’s ship sailed with only £2,000 of coverage and, when the brig arrived in New York, it was “hove down & narrowly inspected by two judicious old sea captains and two able ship carpenters,” who estimated that repair costs would exceed the value of the ship. Because mahogany prices were low at that time, Cruger could not send the ship back to Belize for another cargo. Further, proceeds on the sale of Tucker’s cargo yielded a loss of more than £250 after factoring in the costs of operating the Monkton. Tucker was forced to let Cruger sell the brig at auction. After purchasing the vessel for himself, Cruger requested an additional £55 from Tucker to settle their account.[21]

Between the financial centers of coastal North America and the hardscrabble settlements of mainland Central America, mariners like James Card (fig. 9) became acquainted with the more rigorous aspects of the mahogany trade. He was a Newport resident but spent several years in Belize representing the interests of other Rhode Islanders such as Oliver Ring Warner. Card transported wood for residents of Belize whom he knew personally, including his brother Jonathan. Following a lucrative slaving voyage to Senegal in 1760, James married the daughter of a mahogany trader from Guernsey and purchased a mahogany desk from Edmund Townsend for £203. Like their Rhode Island counterparts, merchants in the Channel Islands supported their business networks by interlinking them with family ties. With his Newport contacts and the Channel Island connections that his marriage brought, Card was well positioned to trade mahogany at different Atlantic ports.

In addition to trading in wood, Card transported slaves into the Bay of Honduras, as well as between Belize and the Mosquito Shore. One slave from the latter place had been convicted of stealing and was sentenced to be “transported from the shore for life.” Card’s client Warner had leased the labor of another slave named Newport to Card’s Rhode Island relative William Cahoon. The slave, who had been born on Africa’s Gold Coast, was intended for cutting mahogany in Belize. Cahoon died, leaving his entire estate to Card’s brother Jonathan, and Newport slipped away to the Mosquito Shore. Although James Card followed with the intent of catching and selling him on Warner’s behalf, an unidentified person tipped off Newport, and he disappeared into the backcountry.[22]

James and his brother Jonathan had a falling-out, which the former regularly lamented but never explained. Following James’s death in Belize in 1772, Jonathan wrote a cryptic letter to his sister-in-law Sarah, offering to send her the proceeds of her late husband’s Belize business ventures. He also referred to “circumstances which may be necessary to be kept private from the ears of people in our place” and “paper” that should remain confidential for “your own security.” The need for secrecy suggests that James’s untimely death at age forty-two may not have been natural.[23]

Jonathan’s attitude toward Belize was less exploitative than that of his brother. The former settled there permanently, raising two children “begotten on the body of a free Mustie woman named Dorothy Taylor.” Before his death in 1788, Jonathan had freed several slaves, including one named Valentine “for divers good causes.” His daughter Sarah married William Roach of New York City and moved from Belize, but Jonathan’s son and namesake continued cutting mahogany at Spanish Creek and Poor Man’s Rest along the Belize River. With a workforce of thirty-five slaves, the younger Jonathan became one of the most successful traders in the settlement. On receiving his father’s inheritance, the younger Jonathan freed one of his father’s slaves named Lucretia, along with her daughter Maria, whom he had probably fathered. Later in life, he expanded his business by supplying ships in the mahogany trade with turtle meat and other provisions.[24]

After the Revolutionary War, British timber merchants and shippers attempted to block American ships from the most lucrative aspects of the mahogany trade, but shorter coastwise voyages and the demand for products from the new republic gave her ships several advantages. In the two years before President Thomas Jefferson’s 1807–8 embargo acts decimated maritime trade, forty-nine American vessels cleared the Honduras Settlement carrying mahogany. All were small ships with limited cargo capacity, the majority being unarmed brigs and schooners of between 46 and 225 tons with an average complement of only seven men. In contrast, British ships in the transatlantic trade usually weighed 300 to 350 tons and carried up to sixteen guns and thirty-six men. A law intended to reserve the best wood for British merchants ostensibly prevented American ships from exporting logs greater than twenty inches in girth, but enforcement proved largely ineffective.[25]

America’s continued presence at Belize represented a tremendous advantage in the mahogany trade. On numerous occasions, settlers there were granted unrestricted trade with America in response to food shortages such as those that followed a gale in 1804 and a hurricane in 1805. One visitor noted that British ships often arrive in ballast (without inbound cargo), but not American ones: “For here, as it happens in our colonies generally, articles of American production are determined to be almost indispensably requisite.” With most of the population engaged in the extraction of wood, rather than farming, settlers at Belize were dependent on imported food, especially for the logging camps. Between 1807 and 1812, most American ships left Honduras for, in order of frequency, New York, Portland, Charleston, Boston, Norfolk, Philadelphia, and Newport. Others sailed directly across the Atlantic, where they were frequently charged the same rate of duty as British ships.[26]

Upriver

Maritime merchants in the mahogany trade traversed the geographic and cultural divide between the worlds of the cosmopolitan cabinetmaker and the remote Central American frontier (fig. 10). Records of their business activities, though sparse, are far more prevalent and detailed than those pertaining to woodcutters and laborers.

The origins of the English settlement on the coast of Belize are shrouded in mystery, but in the turbulent era following the 1667 Treaty of Madrid, when England and Spain agreed to suppress piracy cooperatively, many British mariners went to the coast of Belize. Although the land was part of the Spanish Empire, there was almost no Spanish occupation. The logwood that grew there also attracted British mariners and merchants, since it was in considerable demand in Europe for dyeing textiles. When Dominican friar Joseph Delgado traveled through the country in 1677, pirates under the command of Bartholomew Sharpe, who were camped near the mouth of the Belize River, captured him. The settlement received newcomers from the 1680s on, such as the crew of Captain Coxon. Sent there to appease the Spanish government and evacuate the logwood cutters, Coxon’s crew instead decided to mutiny and join them. The early years of this settlement were characterized by a cooperative approach to labor and a relatively egalitarian way of life, where sailors worked in small groups to cut logwood to sell to visiting shipmasters. Since the wood was to be chipped and boiled for use, it could be exported in any convenient form, so sailors usually cut it into lengths small enough to be carried on the back of a man.[27]

Though fiercely independent, many residents of the community had come from New England, and some still felt an affinity with home. For example, in 1726, when a group of sea captains proposed building a spire on Old North Church, presumably as an aid to navigation for those entering Boston Harbor, “Matthew Bond, Captain Richardson and others” donated cargos of logwood to be auctioned off to support the construction. Inside the church, a large double pew was inscribed “This Pew for the use of the Gentlemen of the Bay of Honduras 1727.” Other cargos were donated between 1727 and 1743, during which time the pew was reduced in size by half for lack of use, and then increased in size again. The baymen’s attendance at the church was intermittent, but their philanthropy remained focused. In 1754 the church sold the pew, presumably because the baymen were no longer using it. Logwood was no longer the primary economic force in Belize, and the residents had developed closer social ties with towns like Newport and New York, which were more deeply engaged in the mahogany trade.[28]

The emergence of the mahogany trade spelled both the end of the egalitarian lifestyle of the logwood cutters and the establishment of a new economic and social hierarchy. Given the size of the trees, mahogany extraction and preparation for shipment required large amounts of labor that had to be well organized into specialized activities. It was practically impossible for anyone without access to abundant sources of labor to participate in the acquisition of mahogany. Slaves began arriving in the settlement by 1724, and they outnumbered whites—“fifty white Men, and about a hundred and twenty Negroes”—by 1745. The growth in the slave population continued rapidly, and by 1779 slaves outnumbered nonslaves by approximately six to one. The economic primacy of mahogany had become solidified, and the settlement’s transformation into a traditional colonial society with a strongly hierarchical social structure was complete. Unlike in the Caribbean islands and North American colonies, however, slaves at Belize lived not on plantations, but in relatively small groups in remote camps in the forest.[29]

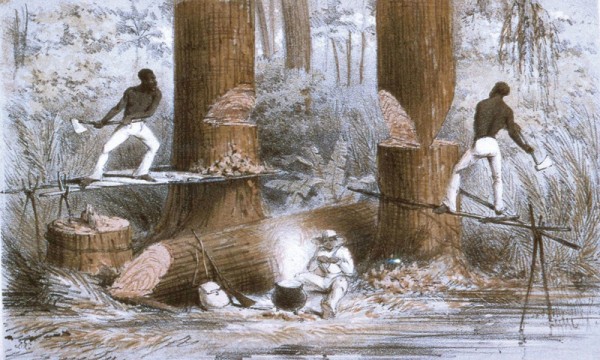

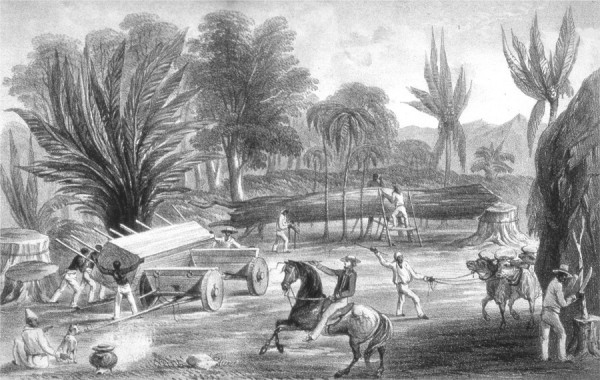

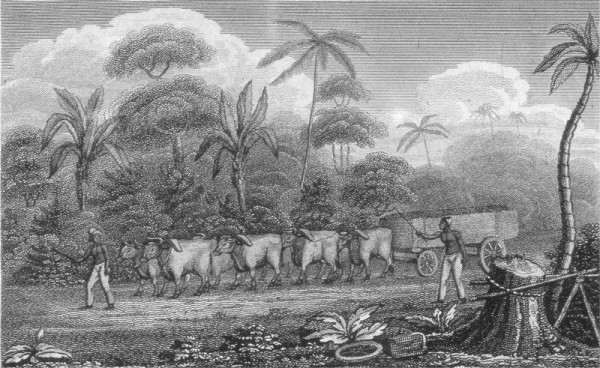

Slaves who occupied the upriver mahogany camps were divided into groups according to the specialized jobs they did, including huntsman, axeman, path clearer, ox-team driver, and log trimmer. Such organized labor was essential, since mahogany trees grew to a height of eighty to one hundred feet, with a basal diameter ranging from four feet up to legendary thicknesses of twelve feet. If left to mature naturally, about one mahogany tree grows in a square mile of forest. Slaves spent nine to ten months of the year in the camps, heading out from the coast at the beginning of the dry season in January and returning with the wood during the heaviest flooding of the rainy season. The huntsman, who roamed vast expanses of forest, located suitable specimens by climbing the highest trees and looking out over the forest canopy during the time of year when mahogany leaves turned yellow. Being a huntsman offered some independence, since if treated poorly he could sell his information to the owner of a neighboring claim. Before the axeman felled a tree (fig. 11), path clearers identified the shortest route to move the log through the woods—avoiding slopes, swamps, and rocks—then built a rudimentary road. In the earliest years, human power alone moved the logs, limiting the size of tree that could be harvested, but by the 1780s teams of oxen became the norm (figs. 12, 13). During the height of the dry season, from February to May, the axemen would fell the trees, usually from a stage built eight to ten feet above the ground to avoid the huge root buttresses that protrude at the base. Once felled, the trees were cleared of their limbs, dragged to the river, and cut with a distinctive mark, often initials, to identify their owner. To avoid overheating the oxen, the most strenuous work was undertaken at night, using torches for light. Other laborers gathered edible leaves to feed these animals.

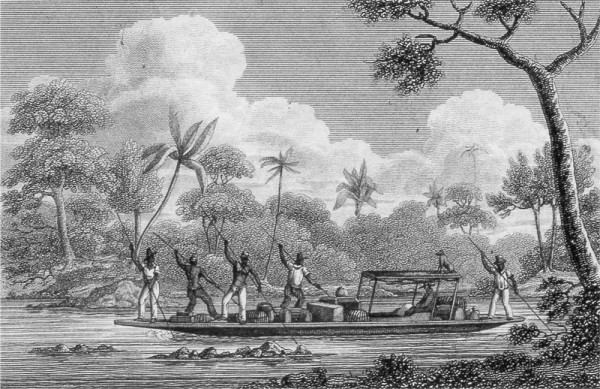

With the advent of heavy rains in July, workers threw the logs into the river, arranged up to two hundred in a large raft, and floated them down to the coast (fig. 14). By the early nineteenth century, woodcutters began capturing the floating logs near the end of the river with a large boom chain attached to huge anchors at each shore (fig. 15). Before boom chains came into use, workers simply steered logs toward shore at the river mouth or allowed them to float out into the harbor, where they were captured and sorted by owner. Either in the forest or on the coast, workers squared the logs to facilitate efficient lading into a ship’s hold and marked them with an inventory code. The largest logs were almost invariably rough-squared in the forest to make them lighter and to prevent rolling (fig. 16). When ships arrived, laborers bundled logs into smaller rafts and lighters floated the rafts out into the harbor, where they were hoisted from the ship’s spars into the hold through specially designed cargo doors at the stern (fig. 17).[30]

Archaeology of the Woodcutting Camps

Of the diverse populations who traversed land and sea in the mahogany trade, the least is known about those who lived at the wood’s point of origin. No firsthand documentation of slave life survives, and descriptions by others are either cursory or obviously promotional of a particular point of view. For example, a medical doctor hired to report to the head of government on the health of the woodcutters found that “a more vigorous and fine looking lot of men is no where to be met with . . . which I am of the opinion is the natural consequence of salubrity of climate, a healthy occupation, and kind treatment.” The doctor was a nineteen-year resident of Belize, and it is doubtful that he was unbiased.[31]

Principals in woodcutting operations probably invested little in the huts and camps in which their workers lived. Composed largely of slave labor, woodcutting camps moved periodically to exploit different parts of the forest (fig. 18). In 1790 a hut with “a thatched roof and inclosed with . . . Pimento sticks, tyed together with small yarns” attracted the attention of a traveler, who noted that it had been “built . . . to lodge the negroes at night, when attending mahogany.” Similarly, an early almanac of Belize described a woodcutting camp as

a small village on the bank of the river, the choice of situation being always regulated by the proximity of such river to the mahogany intended as the object of future operations. In the arranging and appearance of the habitations, much rural taste is often displayed, and it is highly gratifying to the curious to remark the different modes peculiar to the several Nations or Tribes of Africa, as also the improvement introduced by European experience in the construction of the houses. . . . We have frequently seen houses of this kind completed in a single day, and with no other implement than an axe.[32]

Efficiency probably dictated social organization in most camps except when higher-status individuals, such as a foreman or owner, were in residence. With little documentation to shed light on everyday life, the author conducted an archaeological survey to locate and examine sites where woodcutters lived and worked. Because the surrounding forests were actively exploited during the eighteenth century, the survey encompassed the New River valley of northern Belize, from the river mouth in the north all the way to the New River Lagoon in the south. Documentary aids included a group of maps and a census that were drawn and compiled between 1786 and 1790. The maps gave the names of settlers and the locations of their landholdings along the various rivers, often designated by little huts with red roofs that pinpoint camp locations in relation to meanders along the rivers. The census for the settlement breaks down the population by heads of households and lists men, women, and children individually by name, identifying them as white, free, or slave. Integration of these data sets enabled the author to locate the riverside woodcutting claims held by the settlers during the 1780s and to determine the numbers and names of the slaves who lived there for most of each year.[33]

Only a limited portion of the New River is accessible by land, so most of the archaeological survey was undertaken from a skiff with a small outboard engine. Over a six-week period, the author surveyed approximately sixty kilometers of the New River and identified seventeen historic sites. Deposits ranged from a few fragments of bottle glass to several hundred ceramic, glass, and metal artifacts distributed over more than a hectare. According to the census, each of these sites was occupied seasonally by between sixteen and fifty-two woodcutters. Much of the riverbank was in high bush, posing significant challenges for surveying the ground surface, but other sites were located in sugar cane fields that had just been harvested, leaving mostly exposed, burned ground surface, where scatters of artifacts could be spotted easily. Because the New River rarely floods, making soil buildup scant, most of the artifacts were found lying on the surface.

The seventeen sites investigated offer rare insights into woodcutter life. Two sites yielded significant quantities of artifacts, indicating heavy occupation by slaves. One was in dense bush above the confluence of two branches of the New River, approximately twenty-six kilometers from the river mouth. This locality is identified on the 1787 survey map as the camp of Matthias Gale, a settler of considerable property who named his business Caledonia (figs. 19, 20). When staking a land claim, he typically nailed a stave “[cut] with the . . . [word] GALE” to a tree. Gale was a white settler whose household in 1790 included six white men, seven free men, twenty-six male slaves, and four female slaves. He served terms as the Belize settlement’s treasurer and conservator of the peace, in which capacity his duties ranged from acting as chief constable to presiding over marriages. Gale was apparently one of the settlement’s most influential residents until his death about 1794. Since his official positions required him to spend much of his time in town, it is unlikely that Gale lived at Caledonia to any great extent.[34]

The other archaeologically rich site (fig. 19) corresponds with a camp of Robert Francis O’Brien, one of the wealthiest residents at Belize during the 1780s. He owned eighty-two slaves and had claims on the New River and Belize River to the south. Given the size and locations of his property, O’Brien probably quartered his slaves at more than one site and may have moved them from place to place as need arose. As was the case with Gale, O’Brien’s slaves were equally unbalanced by gender, with sixty adult males, thirteen women, and nine children.

Like most of the artifacts recovered from woodcutting sites along the New River, those from Gale’s and O’Brien’s claims are largely associated with food preparation and communal consumption. Indeed, only a few rusty fragments of what appear to be machete blades relate to the dominant activities of cutting, shaping, and transporting wood. Most of the New River artifacts are plates and bowls. As one might expect, these objects are largely undecorated save for minimal shell-edge coloring and transfer printing on some later wares. An occasional teapot fragment suggests activities having to do with individual choice or household decoration, but since teapots are also found in military camps, they cannot be interpreted as conclusive evidence of domestic family life.[35]

The large number of storage vessel fragments recovered at O’Brien’s site suggests that it was more permanent than most camps identified in this survey. The manager of his claim no doubt relied heavily on imported food. By contrast, investigation of Gale’s Caledonia site revealed fewer storage vessel fragments and a higher percentage of gunflints; his workforce may have relied more on hunting for subsistence. Key artifact categories common to other British colonial sites but absent from those along the New River include glass lamp chimneys and lighting devices, household cutlery, window glass, house-construction nails, coins, and clothing buttons. Unlike plantations where hand-me-downs from the main house were common, the slaves working the New River sites had no access to manufactured goods other than what the claimholder or his agent transported upriver for their use.

Two artifacts from New River sites exhibit postmanufacture marks possibly denoting personal ownership (fig. 21). Such marks frequently appear on artifacts from contexts where objects are by necessity stored and treated as communal property, such as aboard ship or in frontier or military camps. Alternatively, marks could express deeply rooted cultural affiliations. Ceramic bowls inscribed with an “X,” sometimes inside a circle, appear frequently in excavations of slave plantations in South Carolina. The consistency of such marks suggests that they did not denote personal ownership. It is difficult to envision the range of activities that might have taken place in these remote forest camps, but with a lack of first-person accounts of life there, it is easy to focus on the economic realm and overlook evidence that might hint at the social or even spiritual practices of the inhabitants. African American priests in modern Cuba inscribe a similar cruciform pattern on the bottom of vessels when they are creating charms, and art historians have traditionally recognized an “X” within a circle as a cosmogram of the Bakongo people of the southwest coast of Africa. Many people from that region were transported across the Atlantic during the slave trade, and Bakongo culture was so influential that other people adopted their practices in both Africa and the Americas. Like the slaves on South Carolina plantations, Belize laborers may have been using these inscribed vessels in Bakongo rituals that connected the living with the powers of the dead, traversing the earthly and spiritual horizons depicted in the cosmogram. These vessels and their sacred contents were not solely remnants of cultural practices fractured by slavery but may have represented the persistence of the slaves’ worldview, one that varied significantly from that of those who enslaved them. As such, they could have been emblems of resistance to the way of life forced on these laborers by the seemingly incessant demand for mahogany.[36]

For most people, the beauty of mahogany transcended the colonial hinterland and conveyed only an aura of richness and refinement that rendered it a desirable cabinetmaking material. Like his contemporaries, Newport merchant Aaron Lopez placed many orders for mahogany furniture with cabinetmaker John Goddard. In March 1770 Goddard billed Lopez for “2 pr. Roles [Torah rollers] for Moses’s Law” at a cost of 13s. 8d. per pair. (In Hebrew, Torah rollers are known as atsey chayim, “trees of life.”) Although it is possible that the rollers were for Lopez’s personal use, it is more likely that they were to hold a Torah he had donated to Touro Synagogue in Newport several months earlier. Prominent individuals often donated decorative and functional objects to the temples and churches they attended, and the use of mahogany would have been a visible symbol of the donor’s wealth and status.[37]

Today, Touro Synagogue displays a sixteenth-century Torah written on deer hide and fitted with rollers that appear to be mahogany. Although there is no evidence that these are the rollers created by Goddard and donated by Lopez, they were produced from the wood of choice for urban furniture of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Mahogany was, however, much more than just a desirable and expensive commodity. Its harvesting, transportation, marketing, and sale represented links in a long chain that bound the disparate lives of slaves, mahogany claim holders, mariners, British merchants, American traders, and furniture makers and their patrons on both sides of the Atlantic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the author thanks Patricia McAnany, Mary Beaudry, Dean Lahikainen, Josephine Carothers and George Schwartz.

Walter J. Gadsby, On the Shores of the Caribbean Sea (Stories of Far-off British Honduras) (London: J. W. Butcher, n.d. [1911]), pp. 53–54. At the invitation of Dean Lahikainen, the author presented a paper on the mahogany trade at the “Boston Furniture Symposium: New Research on the Federal Period,” Peabody Essex Museum, November 14–16, 2003. I am grateful to the participants who made valuable suggestions for this published version.

Unfinished mahogany was shipped well beyond this region, to mainland Europe and beyond, but this study focuses primarily on the colonial and early American trade.

To date, no single volume adequately presents the unconventional history of the Bay Settlement, Colony of British Honduras, and independent nation of Belize. The best sources for the general reader are Nigel Bolland, The Formation of a Colonial Society: Belize, from Conquest to Crown Colony (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977); and Narda Dobson, A History of Belize (London: Longman Caribbean, 1979).

Adam Bowett, “The Commmercial Introduction of Mahogany and the Naval Stores Act of 1721,” Furniture History 30 (1994): 43–56. Robert F. Trent, “Chest with Drawer,” in The Concord Museum: Decorative Arts from a New England Collection, edited by David F. Wood (Concord, Mass.: Concord Museum, 1996), pp. 6–7. Charles H. Foss, Cabinetmakers of the Eastern Seaboard: A Study of Early Canadian Furniture (Toronto: M. F. Feheley Publishers, 1977), p. 3. Boston Gazette, August 22–29, 1737, cited in The Arts and Crafts in New England, 1704–1775, compiled by George Francis Dow (Topsfield, Mass.: Wayside Press, 1927), p. 129.

Ropes Family Papers, undated entry at end of family shop account book, ca. 1760–1770, Peabody Essex Museum (hereafter cited as PEM), Phillips Library. Mack Headley, “Eighteenth-Century Cabinet Shops and the Furniture-making Trades in Newport, Rhode Island,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1999), p. 17.

Object file, acc. 101,792, American Decorative Arts Department, PEM. At some point in the early nineteenth century, the spelling of the family name changed from Chever to Cheever. Dean Thomas Lahikainen, “A Salem Cabinet-maker’s Price Book,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 155, 194.

Paul Carpenter Standley and Samuel J. Record, The Forests and Flora of British Honduras (Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1936). Peter L. Weaver and Oswaldo A. Sabido, Mahogany in Belize: A Historical Perspective (Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico: Institute of Tropical Forestry, 1997), p. 1. F. Lewis Hinckley, Directory of Historic Cabinet Woods (New York: Crown Publishers, 1960), pp. 118–38. Mainland mahogany is now known as Swietenia macrophylla and island mahogany as Swietenia mahogani. A third species grows only on the Pacific coast and is not relevant to this discussion.

The Arts and Crafts in New York, 1777–1799, compiled by Rita Susswein (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1954), p. 138. “The First Account of the State of That Part of America called The Mosquito Shore in the Year 1757,” Public Record Office (hereafter cited as PRO), Kew, England, Colonial Office Records CO123/1. “Dyer to Your Lord,” 1790, Nelson Papers, British Library, Add. 34,903 F.166-170. Report by George Hyde, February 2, 1836, R.2, p. 477, National Archives, Belize. Modern studies have found the rate and density of growth to vary based on a wide range of factors, including age, size, rainfall, and locality. Favorable conditions include fertile and well-drained soils that characterize large portions of modern Belize. K. Shono and L. K. Snook, “Growth of Big-Leaf Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) in Natural Forests in Belize,” Journal of Tropical Forest Science 18, no. 1 (2006): 66–73.

“Abstracts of English Shipping Records Relating to Massachusetts Ports, from Original Shipping Records in the Public Record Office, London, 10 vols., compiled for the Essex Institute, Salem, Massachusetts,” typescript, 1931, PEM.

Ibid. Jonathan Tomkyne, “An account of the quantities of Mahogany, satinwood, rose wood not including any dyeing woods imported into England from Christmas 1777 inclusive to Christmas 1783,” April 11, 1785, PRO, T64/276B/417. One mid-nineteenth-century mahogany merchant stated that the best planks were at least eight to ten inches thick and as long as possible (not under twenty-seven feet) (E. Chaloner and W. Fleming, The Mahogany Tree: Its Botanical Characters, Qualities and Uses, with Practical Suggestions for Selecting and Cutting It in the Regions of Its Growth, in the West Indies and Central America [Liverpool: Rockliff and Son, 1850], p. 46). Daniel Finamore, “‘Pirate Water’: Sailing to Belize in the Mahogany Trade,” in Maritime Empires: British Imperial Maritime Trade in the Nineteenth Century, edited by David Killingray, Margarette Lincoln, and Nigel Rigby (Rochester, N.Y.: Boydell Press, 2004), pp. 30–47. Although New Providence in the Bahama Islands is technically in a mahogany-growing region, its location as a transit point between Caribbean and North American colonial ports, its limited forested area, and the large quantities of wood exported indicate that the majority of wood reported to have arrived from there actually originated elsewhere. In the five years between January 1797 and June 1802, approximately 50 percent of mahogany exports of Belize went directly to the British Isles, 42 percent went to American ports, while 8 percent went to Jamaica or New Providence to be transshipped elsewhere.

Conversely, the vast majority of wood exported from primary extraction centers such as Belize was in the form of squared logs, with only enough wood in other forms to fill the interstitial areas of the cargo hold (Finamore, “‘Pirate Water,’” pp. 44–45). New-York Daily Advertiser, November 16, 1797.

“Abstracts of English Shipping Records.”

Dobson, A History of Belize, pp. 60–61. “Dyer to Your Lord.” Hayley and Hopkins to Aaron Lopez, London, December 8, 1770, Aaron Lopez Papers, letters, box 652, book 631, pp. 42, 47, Newport Historical Society (hereafter cited as NHS).

Commerce of Rhode Island, 1726–1800, 2 vols. (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1914), 1: 386–87, 172. Honduras Almanack (Belize: The Magistrates, 1827), p. 12. Chaloner and Fleming, The Mahogany Tree, pp. 58–59.

Archibald Robertson Gibbs, British Honduras: An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Colony from Its Settlement, 1670 (London: Sampson, Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1883), p. 116, citing the Honduras Observer, 1843. Orlando W. Roberts, Narrative of Voyages and Excursions on the East Coast and in the Interior of Central America (Edinburgh: Constable Company, 1827), p. 302, citing the Macclesfield Courier, October 1823.

Henry Drinker to Capt. Oswald Eve, November 30, 1771, Drinker Letter Book, 1769–1772, p. 449, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Angel Cal, “Rural Society and Economic Development: British Mercantile Capital in 19th-Century Belize” (Ph.D. diss., University of Arizona, 1991), pp. 128–29. Henry Gardiner, “Detailed Account of the Establishment and Expense of a Mahogany Gang,” in Young Anderson, Eastern Coast of Central America: Mr. Anderson’s Report (London: Manning and Mason, 1839), pp. 135–38, cited in Cal, “Rural Society,” p. 132. Evidence for renting out the labor of slaves for timber cutting and other work appears frequently in the Henley Papers, Caird Library, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (hereafter cited as NMM). In 1809, for example, the master of the ship Freedom paid over £84 for 253 days of “negro hire” at 6s. 8d. per day (HNL/59/83), and in 1813 Capt. Robert Horry submitted a bill for 315 days’ labor performed by Antonio, January, Joe Long, Ned Jones, Billy Hemming, Joe Lamb, Quam Edwards, Dick Edwards, John Morris, and Scotland Grant, who warped the ship Lord Nelson off the shore after she was driven up by a hurricane in 1813 (HNL82/38).

Account of Sales of Sundry goods shipped by Mr. Aaron Lopez on Board the Brig Charlotte in the Bay of Honduras, 1768, Papers of Aaron Lopez (hereafter cited as PAL), box 1, folder 9, American Jewish Historical Society, New York (hereafter cited as AJHS). Hayley and Hopkins to Aaron Lopez, September 19, 1772, PAL, box 14, folder 1, AJHS. William Robertson to Aaron Lopez, September 22, 1770, Aaron Lopez Papers, letters, box 652, book 631, NHS. Account of charges on the Minerva Capt. Samuel Clarke from the Bay of Honduras for account of Mr. Aaron Lopez, Hayley and Hopkins, April 30, 1773, PAL, box 2, folder 11, AJHS. On this voyage at least, the charges for lighterage, pierage, pilotage, small repairs, and clearance totaled more than the value of the cargo.

John Newdigate to Aaron Lopez, April 9, 1771, Aaron Lopez Papers, letters, box 652, book 632, NHS. Ron Potvin, “‘A poor soft weak Headed puffed up foolish fellow’: The John Newdigate Controversy,” Newport History 68, no. 236 (1997): 137–42.

John Newdigate to Aaron Lopez, July 14, 1771, Aaron Lopez Papers, letters, box 652, book 632, NHS. Nathaniel Russell to Aaron Lopez, April 6, 1770, February 15, 1771, and March 29, 1771, Aaron Lopez Papers, letters, box 652, book 631, NHS. Virginia Steele Wood, personal communication, July 23, 2004.

Cruger to William Tucker, New York, August 9, 1766, and April 22, 1767, Henry Cruger Papers, letter book, 1764–1768, New-York Historical Society (hereafter cited as N-YHS).

James Card Papers, MSS9001C, box 1, Rhode Island Historical Society (hereafter cited as RIHS), including James Gourhty Sr. to Capt. Card, August 14, 1771, and Card to Warner, April 4, 1770. Private records book 1, 1774–1797, p. 299, National Archives, Belize.

Charles H. Card, “Richard Card and Descendents,” typescript, 1996, RIHS. Jonathan Card to Sarah Card, July 2, 1772, Sarah Card Papers, RIHS.

Private records book 1, 1774–1797, pp. 84, 105, National Archives, Belize. List of the Inhabitants of Honduras, taken by His Majesty’s Superintendent, in January and February 1790, CO123/11, PRO. Jonathan Card’s Bill, HNL/86/4, Caird Library, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, U.K.

George Henderson, An Account of the British Settlement of Honduras (London: R. Baldwin, 1811), pp. 33–35. Port of Belize Shipping Returns for 1807 and 1809 through 1812, CO128/1, PRO. Finamore, “‘Pirate Water.’” Henderson, An Account of the British Settlement of Honduras, p. 34.

Sir John Alder Burdon, Archives of British Honduras, 3 vols. (London: Sifton Praed, 1931–1935), 2: 5. Henderson, An Account of the British Settlement of Honduras, p. 33. Standard commodities arriving on American ships included bread, flour, crackers, butter, vinegar, pitch, potatoes, sheep, turkeys, lumber and shingles, as well as preserved mackerel, pork, beef, onions, and codfish in hogsheads, kegs, and barrels. Port of Belize Shipping Returns for 1807 and 1809 through 1812, CO128/1, PRO. Memorial of the Committee of Merchants trading to Honduras on the subject of orders allowing American ships to import Mahogany & logwood into this country, July 13, 1797, PC 1/39/125, PRO.

Daniel Finamore, “A Mariner’s Utopia: Pirates and Logwood in the Bay of Honduras,” in X Marks the Spot: The Archaeology of Piracy, edited by Russell K. Skowronek and Charles Ewen (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005), 64–78. Burdon, Archives of British Honduras, 1: 2, 57, 60. Gilbert M. Joseph, “John Coxon and the Role of Buccaneering in the Settlement of the Yucatan Colonial Frontier,” Belizean Studies 17, no. 3 (1989): 2–21.

Charles Knowles Bolton, Christ Church, Salem Street, Boston, 1723: A Guide (Boston: Christ Church, 1944), p. 96. Mary Kent Davey Babcock, Christ Church, Salem Street, Boston: The Old North Church of Paul Revere Fame, Historical Sketches, Colonial Period, 1723–1775 (Boston: Thomas Todd Co., 1944). The practice of donating wood to support causes has precedents in the region. In 1648 the Company of the Eleutherian Adventurers acknowledged support from Massachusetts settlers for their fledgling Bahamian community with a gift of ten tons of braziletto, which was sold in Boston for £124 and applied to the Harvard College Endowment Fund. See Zoe C. Durrell, The Innocent Island: Abaco in the Bahamas (Brattleboro, Vt.: Durrell Publications, 1972), p. 20.

Bolland, The Formation of a Colonial Society, p. 49. CO137/48, PRO. Bolland, The Formation of a Colonial Society, p. 50.

Henderson, An Account of the British Settlement of Honduras, pp. 56–64. Finamore, “‘Pirate Water,’” pp. 30–47.

Dr. John Young to Supt. Reporting on the health and physical conditions of work of the mahogany cutters, August 8, 1836, 2R529-32, National Archives, Belize.

Thomas Graham, “Journal of my Visitation,” 1790, CO123/9, PRO. Honduras Almanack, pp. 8–9.

The National Science Foundation funded the author’s archaeological survey. Daniel Finamore, “Sailors and Slaves on the Woodcutting Frontier: Archaeology of the British Bay Settlement, Belize” (Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 1994). “A Map of that part of Yucatan in the Bay of Honduras allotted to Great Britain for the cutting of Logwood,” by David Lamb, CO700 BH no. 14, 1787, PRO. “List of the Inhabitants of Honduras with their Families,” 1790, CO123/9:256-262, PRO.

Private Records Book 1, 1774–1797, February 21, 1789, p. 120, National Archives, Belize.

Joyce M. Clements, “The Cultural Creation of the Feminine Gender: An Example from 19th-Century Military Households at Fort Independence, Boston,” Historical Archaeology 27, no. 4 (1993): 39–64.

Olive R. Jones and E. Ann Smith, Glass of the British Military, ca. 1755–1820 (Quebec: Parks Canada, 1985), p. 115. Leland Ferguson, “‘The Cross is a Magic Sign’: Marks on Eighteenth-Century Bowls from South Carolina,” in “I, Too, Am America”: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life, edited by Theresa A. Singleton (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), pp. 116–31. Leland Ferguson, Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650–1800 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press), 1992.

Aaron Lopez to John Goddard, 1760–1771, PAL, box 12, folder 10, AJHS. Stanley F. Chyet, Lopez of Newport: Colonial American Merchant Prince (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970), p. 57. Torahs were not commonly owned for personal devotion, though they were held by some wealthy Americans of that era. Jonathan Sarna, personal communication, December 1, 2003. Commerce of Rhode Island, 2: 195, Jeremiah Osborne to Aaron Lopez, Graves End, March 31, 1767, “a sett of candle stick worth £36 I have on board from Enocks Mother for the Sinegoge.” These candlesticks arrived on the ship Pitt from Lisbon, delivered by Capt. Osborne in 1767. Bert Lippincott, librarian, NHS, personal communication, April 2003.