Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825–1835. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine; marble, glass. H. 37", W. 42" D. 20". (Courtesy, Aileen Minor Antiques.)

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825–1835. Mahogany with unrecorded secondary woods; marble, glass. H. 39" W. 42" D. 20". (© Christie’s Images Limited [2006].)

Pier table labeled by Michael Allison, New York City, 1816–1825. Rosewood with tulip poplar; brass, marble, glass. H. 37" W. 40" x D. 20". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Pier table, New York City, 1820–1830. Rosewood with white pine; marble, glass. H. 39", W. 44", D. 19". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Composite illustration showing, (a) Crispijn van de Passe, Oficina Arcularia (Amsterdam, 1642) pl. 17 (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection); (b) detail of the support on the pier table illustrated in fig. 30; (c) George Smith, Ornamental Designs (London, ca. 1812), pl. 30 (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection); (d) William Smee and Sons, Designs of Furniture (London, ca. 1840), pl. 86 (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection).

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1820–1830. Mahogany with tulip poplar; marble, glass. H. 38", W. 34", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Delaware, permanent collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table bearing the label of Anthony G. Quervelle, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825–1829. Mahogany with tulip poplar; brass, marble, glass. H. 37 3/4", W. 48", D. 22". (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

The Family of John Q. Aymar, attributed to George W. Twibill, New York City, ca. 1833. Oil on canvas. 30" x 40". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) No period images of a Philadelphia pier table in situ are known. In this New York interior, the pier table and the fireplace surround share complementary features such as gilt Ionic capitals. John Q. Aymar was a prominent China trade merchant; the ship masts in the distance symbolize the source of his family’s wealth and social standing.

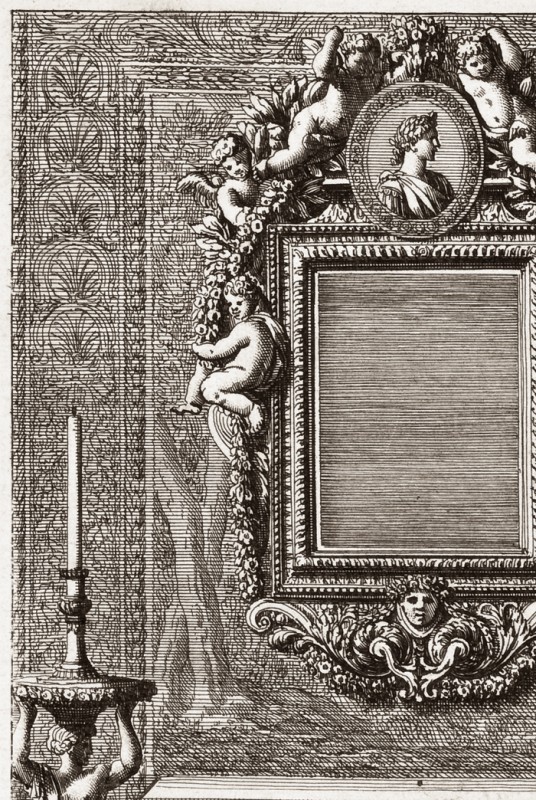

Design for a pier table in Jean le Pautre, Livre de miroirs, tables et gueridons (Paris, ca. 1660), pl. 3. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Pier table attributed to William Buckland and William Bernard Sears, Richmond County, Virginia, 1761–1771. Cherry with beech; marble. H. 31 1/4", W. 45 3/8", D. 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sideboard table attributed to William Buckland and William Bernard Sears, Richmond County, Virginia, 1761–1771. Walnut; marble. H. 35", W. 42 1/2", D. 25 1/2". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier or side table, carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania ca. 1765. Mahogany; marble. H. 34", W. 66", D. 30". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the J. Stogdell Stokes Fund and the John D. McIlhenny Fund, 1953; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1767–1770. Mahogany with yellow pine and walnut; marble. H. 32 3/8", W. 48 1/4", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918 [18.110.27]; photo, Gavin Ashworth, Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

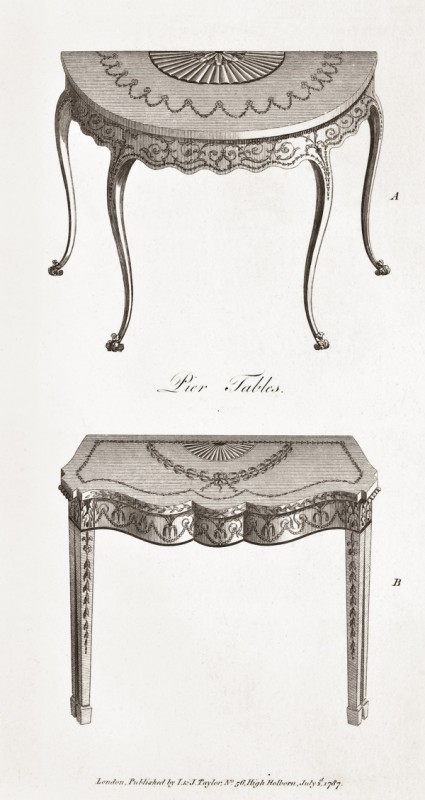

Designs for pier tables in Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London, 1793), pl. 4. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Designs for pier tables in George Hepplewhite, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 1794), pl. 65. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

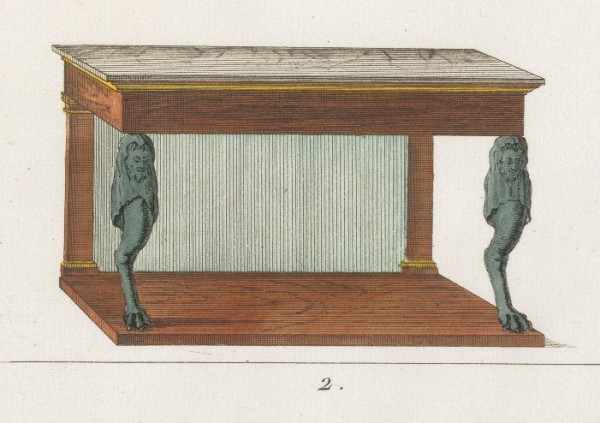

Detail of pier table in Pierre de La Mésangère, Collection de meubles et objets de goût (Paris, 1802), pl. 10. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930 [30.80], Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Pier table illustrated on plate 17 in Rudolph Ackermann, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics (September 1828). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Pier table bearing the label of Joseph B. Barry & Son, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1810–1815. Mahogany, satinwood, and amboina with tulip poplar and white pine; brass, marble, glass. H. 38", W. 54", D. 24". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Friends of the American Wing Fund, Anonymous gift, George M. Kaufman gift, Sansbury-Mills Fund, gifts of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, Mrs. Russell Sage, Mrs. Frederick Wildman, F. Ethel Wickham, Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, and Mrs. F. M. Townsend by exchange; and John Stewart Kennedy Fund and bequests of Martha S. Tiedeman and W. Gedney Beatty by exchange, 1976 [1976.324] Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Pier table attributed to Joseph B. Barry, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1820. Mahogany with unrecorded secondary woods; marble, glass. H. 40", W. 48", D. 20". (Courtesy, Antiques [May 1989], Brant Publications Inc.; photo, Wayne Gibson.)

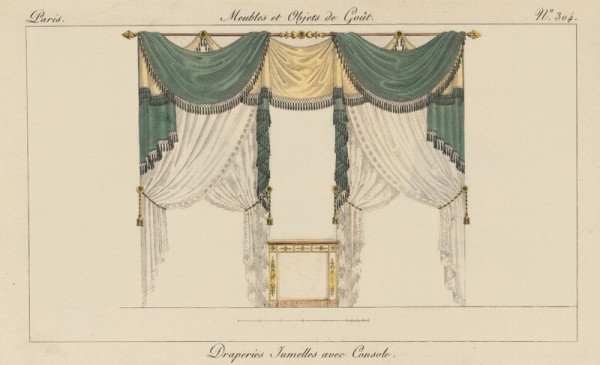

Design for draperies in Pierre de la Mésangère, Collection de meubles et objets de goût (Paris, 1808), pl. 304. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930 [30.80] Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

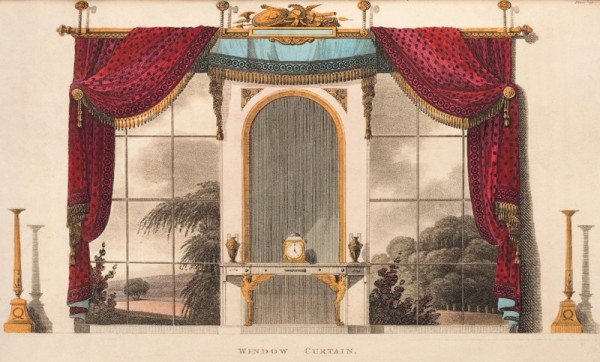

Design for a window curtain for a boudoir in Rudolph Ackermann, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics (April 1809), pl. 19. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Augustine Edouart, Family in Silhouette, New York City, 1842. Sepia wash with black paper cutouts. 19" x 28 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Henry Sargent, The Tea Party, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1824. Oil on canvas. 64 3/8" x 52 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs. Horatio Appleton Lamb in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Winthrop Sargent, 19.12; photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Detail of the painting illustrated in fig. 23.

Henry Sargent, The Dinner Party, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1821. Oil on canvas. 61 5/8" x 49 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs. Horatio Appleton Lamb in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Winthrop Sargent, 19.13; photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Loud & Brothers, upright piano, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1831. Mahogany. H. 76 1/8", W. 50", D. 28". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, Alice M. Hufstader gift, Richard B. Kellam gift, Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, by exchange, and funds from various donors, 1976 [1976.317.1] Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825–1832. Mahogany with tulip poplar; marble, glass. H. 38", W. 38", D. 20". (Courtesy, LancasterHistory.org.)

Jacob Eichholtz, Mrs. John Frederick Lewis, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1827. Oil on canvas. 36" x 28 1/2". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, gift of Mrs. John Frederick Lewis [John Frederick Lewis Memorial Collection].)

Pier table bearing the label of Anthony Quervelle, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1829. Mahogany with tulip poplar; marble, glass. H. 43", W. 66", D. 26". (Courtesy, White House Historical Association; photo, Bruce White.)

Pier table, Philadelphia or Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1830–1835. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine; marble, glass. H. 37", W. 40", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table attributed to Barry and Krickbaum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1837. Mahogany; marble, glass. (Courtesy, The Hermitage: Home of President Andrew Jackson, Nashville, Tennessee; photo, Bill Lafevor.)

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825–1835. Mahogany and rosewood with tulip poplar; marble, glass. H. 44", W. 50", D. 24". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

John Henry Belter, étagère, New York City, 1840–1860. Rosewood; marble, glass. H. 88", W. 59", D. 22". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

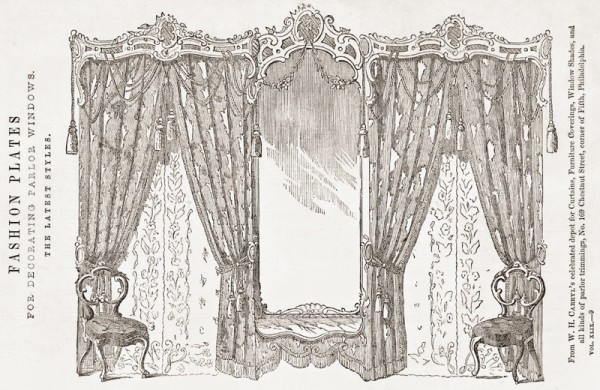

“Fashion Plates for Decorating Parlor Windows,” Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book 49 (July 1854). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The pier/console table is low in height and does not have an integral glass plate since an extended pier glass hangs above.

Lobby of the Omni William Penn Hotel, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (Courtesy, Omni William Penn Hotel; photo, Laura Libert.)

Pier tables were the epitome of stylish taste in early-nineteenth-century America. The materials used in their construction were often expensive and conspicuously ostentatious, placing them at the vanguard of stationary furniture forms. Pier tables were also opulent in function, serving both as glorified stands for lighting equipment and ornaments and, in most instances, as elaborate looking glass frames. Placed between windows, pier tables with mirrored backs worked in conjunction with pier glasses hanging above them to reflect light and create the illusion of doubled space.

Contrary to modern interpretations, pier tables were seldom bought in pairs, rarely used for dining or serving beverages, and almost never found in hallways. To be displayed effectively, these large architectural objects demanded a setting that was harmonious, expansive, and splendidly furnished. Consequently, the owners of pier tables in Philadelphia tended to be wealthy businessmen. With very few exceptions, patrons placed their tables in parlors. As this essay will demonstrate, owners used these objects not only to decorate their homes but also to enhance sociability and to facilitate business.

Although inspired by similar classical sources, Philadelphia and New York cabinetmakers produced empire-style pier tables that were regionally distinctive. Philadelphia rectangular pier tables often have upper rails with a cavetto molding, carved or turned wood front supports and applied rear pilasters, oil gilding, integral looking glass plates with decorative borders, and ogee-curved lower shelves with demilune, pie-wedge mahogany veneers (figs. 1, 2). By contrast, New York rectangular pier tables typically feature straight-sided rails, columnar marble front supports and applied rear pilasters, gilded cast brass ornaments, delicately shaded freehand gilding and bronze powder stenciling, integral looking glass plates with undecorated borders, simple incurved lower shelves, and carved, cornucopia brackets adjoining lion’s-paw feet (figs. 3, 4).[1]

Most pier tables represent the work of multiple tradesmen, including joiners, turners, carvers, gilders, stonecutters, and glassworkers. By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, large manufactory warehouses dominated urban furniture production, consolidating the work of smaller specialized shops scattered throughout the city. Competing firms often purchased parts from the same specialized shops, resulting in a uniformity of design. In urban classical furniture, regionalism was largely a product of standardization and piecework production.

Philadelphia makers had access to the labor and materials necessary to copy New York pier tables, but they chose to distinguish their products from those made in other urban centers. During the 1820s Philadelphia cabinetmakers adopted the carved scroll-and-paw support as a fashionable alternative to the marble columns favored in New York. As with most classical details, however, this “new” feature was actually the third or fourth revival of an earlier design (fig. 5).

With increasing competition, makers and retailers of pier tables had to be innovative to satisfy the demand for fashionable forms. At the same time, they had to standardize production to control costs and generate profit. Period price books and surviving objects indicate that makers and retailers resolved these opposing market forces by developing basic frame designs to which options could be easily added. The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices (1828) lists a “plain pier table” with “four solid columns” at $4.50. “Two plain solid pilasters rabbetted to receive glass” cost twenty-five cents “extra from [the] start.”[2]

Dimensional variations among extant Philadelphia pier tables suggest many were commissioned rather than purchased from stock-in-trade. The example illustrated in figure 6 was almost certainly made for a small pier or recess, whereas the unusually large example shown in figure 7 was commissioned for a room with broad expanses of wall space. As was the case with earlier pier tables, some Philadelphia examples made in the classical style had ornamental details intended to echo or harmonize with interior architectural components (fig. 8).[3]

Genealogy of the Pier Table Form

Elaborately carved wood tables with marble tops were Italian renaissance inventions with roots in antiquity. Popularized by French King Louis XIV at his court at Versailles during the seventeenth century, marble-topped pier tables situated beneath looking glasses became status symbols in fashionable state apartments throughout Europe. Tastemakers such as Robert Adam began advocating lighter, more delicate variations suitable for both wood and marble tops during the 1760s, but French court designs under Napoleon Bonaparte soon returned to a more architectonic, archaeologically correct interpretation of ancient classical design. This included the “empire” pier table with a looking glass plate in the back and its many variants, which became fashionable in America during the first half of the nineteenth century.

The wall-oriented tables that originated in Italy during the late sixteenth century were highly sculptural, often designed by architects, and lavishly finished with carving and gilding. Imposing and expensive, these tables were ideally suited to formal French interiors of the late seventeenth century. As Carl Kaellgren has argued, the grand rooms at Vaux-le-Vicomte and Versailles, used for formal and ceremonial activities, helped popularize and codify the form and presentation of side, pier, and console tables. By the mid-seventeenth century, pier tables were designed for specific architectural settings, often accompanied by a looking glass above and candlestands on either side (fig. 9).[4]

In America, “slab tables,” or “sideboard tables,” with marble tops came into use by the late 1720s. As the latter term implies, many of these examples were probably used in dining rooms. Their height, which was lower than that of classical pier tables, was well suited for displaying ceramics, glass, and plate, as well as serving food and drink. A notable exception, however, can be found in two marble-top tables commissioned for Mount Airy, Richmond County, Virginia, house of planter John Tayloe II (figs. 10, 11). Although both objects are attributed to architect William Buckland and his carver William Bernard Sears, their stylistic disparity suggests that only one of the tables may have been used in a dining room. Similarly, the Philadelphia examples illustrated in figures 12 and 13 may have been intended as pier tables for use in a parlor. Indeed, the scroll-foot example was derived from a design for a pier glass and table illustrated on plate 152 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Director (1762). Both follow grand European tradition in being solely the work of a carver.[5]

For the most part, American pier tables are a post-Revolutionary form. A few Philadelphia examples dating from the last quarter of the eighteenth century are in the early neoclassical style promulgated by Robert Adam, George Hepplewhite, and Thomas Sheraton (figs. 14, 15). Hepplewhite and Sheraton associated pier tables with excessive decoration and specific use. As Sheraton noted in 1793, “pier tables are merely for ornament under a glass, they are generally made very light, and the style of finishing them is rich and elegant.” The following year Hepplewhite wrote: “Pier Tables are become an article of much fashion; and not being applied to such general use as other Tables, admit, with great propriety, of much elegance and ornament.”[6]

A pier table made by New York cabinetmaker Charles-Honoré Lannuier recalls Sheraton’s designs in having cross-stretchers and an urn finial, but most American examples in the early neoclassical style stand on four straight legs with no stretchers or lower shelf. Excepting differences in their tops, some pier tables are difficult to distinguish from card tables. As the nineteenth century progressed, the design of pier tables became increasingly distanced from that of other tables. While this is consistent with the greater numbers of specialized forms that appeared from 1775 to 1850, it also suggests progressively nuanced distinctions in the function of objects and the language used to describe them.[7]

By the second decade of the nineteenth century, the term “pier table” carried connotations that to most Americans were distinct from the form’s closest cognate, the “console table.” Scholars in Europe do not draw distinctions between pier tables and console tables because there the two forms were effectively synonymous. In America, the term “pier table” appears with much greater frequency than “console table.” The Society of Journeymen Cabinetmakers’ 1836 wareroom inventory lists a single “consul” table and seven “pier” tables. As understood here, a console table was attached to the wall and did not have a back frame or support.[8]

Perhaps the biggest change in the design of pier tables was the incorporation of a mirrored glass plate. As Sheraton noted:

The glasses are often made to appear to come down to the stretcher of the table; that is, a piece of glass is fixed in behind the pier table, separate from the upper glass, which then appears to be the continuation of the same glass, and, by reflection, makes the table to appear double. This small piece of glass may be fixed either in the dado of the room, or in the frame of the table.

With the advent of the “antique taste” and its emphasis on massive, architectonic forms and columnar supports, plate glass was incorporated in numerous forms, including sideboards, dressing tables, and pier tables. The design and structure of late neoclassical furnishings facilitated and depended on the use of mirrored glass more than any preceding style (fig. 16). Thus, when Rudolph Ackermann illustrated a formal pier table in his Repository of Arts (fig. 17), he noted: “At the back is a looking-glass, in order both to lighten the design and to give an appearance of distance, where it would otherwise be heavy.”[9]

Befitting Philadelphia’s large and diverse population in the nineteenth century, the city’s classical pier tables exhibit an eclectic mix of stylistic sources. Appropriately, the best-known pier table from that city is an intriguing early example made in the shop of Joseph B. Barry & Son for merchant Louis Clapier (fig. 18). Made under the supervision of Barry’s foreman, George Wright, the table displays elements of both French and British design. The carved and pierced panel at the back derives from Sheraton’s Drawing Book, whereas the spiral garlands on the front columns and gilt brass mounts have parallels in French and Italian work. Circa 1820 Barry produced another hybrid pier table—sporting the by now de rigueur glass plate in the back and a marble rather than wood top—for which there is no direct parallel (fig. 19). The robustly carved and gilt lion’s-paw feet and their accompanying winged brackets recall fashionable New York pier tables, while the inset marble shelf and the scrolled gilt brackets along the apron provide visual interest and distinction to what is essentially a French Consulate form. Barry’s “sampling” was the norm rather than the exception, reflecting the choices available to makers, who wanted more profitable and hence standardized production, and their patrons, who wanted distinctive if not quite unique pieces.[10]

Cultures of Sociability

From their inception, pier tables in Europe were envisioned as an integral part of the enfilade—the prescribed progression of visitors from room to room. These tables were first encountered in passing as visitors made their rounds through the house. After touring the house and grounds, the party withdrew to the best parlor, where elaborate window draperies created a stage set within the home, with the pier table and pier glass serving as the centerpiece (fig. 20). On either side of these objects were large windows that looked out onto the estate (fig. 21). After dark, pier tables set with lighting fixtures and accompanied by looking glasses functioned as surrogate windows, providing a dramatic source of illumination. Like the owner’s property, which had been visible through the flanking windows during the day, these furnishings also served as totems of wealth and social standing.[11]

This legacy of use continued in America, albeit on a smaller scale. Pier tables did not become fashionable in the United States before the widespread introduction of double parlors, an architectural innovation that evolved from the traditions of aristocratic and court custom in Continental Europe and Britain. By the second half of the eighteenth century, front and back parlors set next to a side entry and passage became the common urban town house form for the middling and upper classes in cities throughout the English-speaking world. Within this architectural setting, pier tables functioned en suite with lighting devices and looking glasses to reflect light throughout the room while creating the illusion of doubled space. Like the front parlors in which these tables were placed, their use was infrequent and formal, ideally suited to entertaining. As large, fixed, and brightly lighted objects, pier tables dictated guests’ movement through the room and facilitated the discreet yet highly critical value judgments that characterized the culture of sociability. Thus, just as pier tables were part of an ensemble of furnishings, they also synchronized with an ensemble of human relationships.[12]

Pier tables are unusually tall and have no corresponding seating: they were designed for standing encounters. Pier tables with looking glass back plates almost always have marble tops, which, as the table’s most visually accessible and prominent feature, connoted antiquity while signifying the object’s massiveness, cost, and potential use. Stone tops were very durable, impervious to both liquid and fire, and comparatively easy to clean: these traits help explain why the popularity of marble-topped pier tables in America coincided with the advent of oil lighting. Following the invention of the Argand lamp in 1782, owners could light their homes more brightly than ever before, facilitating increased nighttime entertaining and complementing reflective surfaces. Yet in addition to being a fire hazard, the Argand lamp and its many offspring—astral, solar, and sinumbra lamps—were relatively fixed lighting devices, as an 1811 Philadelphia publication lamented:

It has been a strong prejudice against the use of [Argand] lamps, that they can only be used for stationary or fixed lights, as being moved by hand, they are liable either to go out or spill the oil; to prevent this inconvenience, I would recommend, that a common tin hand-lamp be used.[13]

The growing popularity of stationary oil lamps as major lighting components for the home made the size and immobility of pier tables a functional asset rather than a liability. The successful use of expensive oil lamps also suggested a well-managed household; such lamps were fickle, prone to extinguishing, and required constant maintenance. According to The House Servant’s Directory: “Lamps are now so much in use for drawing-rooms, dining-rooms, and entries, that it is a very important part of a servant’s work to keep them in perfect order, so as to show a good light.” Thus, pier tables, looking glasses, and oil lamps were costly luxuries that worked together to reflect their owner’s status (fig. 22).[14]

Pier tables were not as common as the number of surviving examples would seem to suggest. Because these objects were sturdily built, endured little physical use, and usually belonged to families of means, they have survived in larger numbers and in better condition than perhaps any other table form. Philadelphia inventories reveal that at least 59 individuals owned pier tables between 1830 and 1839, and that number increased to 155 between 1840 and 1850. These figures reflect the greater popularity of the pier table form and the city’s expanding market base. Indeed, between 1800 and 1850 Philadelphia’s population increased by a factor of six (Table 1). Although pier tables are often displayed in pairs today, the majority (78 percent) of Philadelphia owners had a single table in their best parlor.[15]

Between 1830 and 1850 from 2.3 percent to 13 percent of the population of Philadelphia owned pier tables, but these figures must be examined within the larger context of table ownership and home furnishings. For instance, pier tables appear with much less frequency than sofas, even though their average appraised values were similar. Previously owned pier tables were well within the financial reach of many consumers, yet for reasons of practicality and comfort, most opted to invest in sofas (Tables 2, 3). The comparative rarity of pier tables in Philadelphia suggests that few families were willing or able to allocate the time, space, and money to procure one. As luxury items, pier tables held certain meanings for their owners that were not shared by the populace at large (Table 4).

During the first part of the nineteenth century, most owners of pier tables in Philadelphia were professionals whose success depended on social and business networks and the exchange of information (Table 5). They tended to be wealthy and to live and work along the city’s major thoroughfares near the Delaware River—the heart of Philadelphia’s economy. In addition to shared proximity, many owners also had in common old claims to property rights within Philadelphia County.[16]

Due to the distinctive character of ground rent, the system of land tenure in Philadelphia, in which renters paid a perpetual annual rent of 6 percent of the lot’s value at the time of the deed, property did not change hands often. Although the ground rent system virtually eliminated capital barriers and brought buying a house within the reach of many Philadelphians, property ownership remained largely in the hands of landed elites, the beneficiaries of inheritance. The ground rent system also meant that those who aspired to wealth but did not have the luxury of inherited land were forced to rely on property owners for credit. Pier table owners ensured the cultural capital of their extended families via property ownership within an urban setting. For instance, skin dresser and businessman George Schryer, whose will lists a “mahogany pier table, marble top and mirror” valued at ten dollars, also owned more than a dozen houses and lots, all located on the same street. In his will, Schryer bequeathed property to his extended family, thus ensuring the continuation of his dynasty. The extraordinary landholdings of most owners of pier tables suggest a link between the form and its old world connotations, wherein power was often based on hereditary land rights.[17]

People who owned pier tables were also characterized by the diversification of their investments. Stephen E. Fotterall—listed as a “gentleman” living at 152 South Third Street in the 1839 city directory—had real estate valued at $243,745.50, stocks and loans at $374,620.02, ground rents at $168,264.70, cash and gold at $1,290.00, bank assets at $401,335.00, and property for sale at $89,550. With approximately one-third of his assets invested in low-risk real estate, Fotterall (who owned two pier tables appraised at $40.00 each) had a security blanket to offset ventures of higher risk. In Philadelphia, owning a pier table was a sign that the owner likely had a substantial portion of his assets invested in ground rents, a guaranteed source of income and an effective tool for securing credit.[18]

Class distinction was not easily discernible in Philadelphia’s architecture, where both rich and poor lived in town houses that looked similar from the street. Given Philadelphia’s architectural homogeneity, it is not surprising that probate inventories follow a strikingly similar progression. Most begin in the front parlor, where in well-to-do households valuable and prized furnishings impressed visitors’ senses: sight (through lighting devices, sparkling mirrors and ornaments, exotic woods, lustrous fabrics), touch (soft fabrics on furniture, cold and hard stone tops and sculpture) and sound (mantel clocks ticking, plush carpets that dampened noise). In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, a typical upscale Philadelphia parlor had one or two sofas, between six and twelve chairs, one or two card or pier tables, and a center table. Lighting devices, glass ornaments, and fireplace equipment were also standard. Appraisers next moved into a second or back parlor, then on to the dining room. The second and potentially third stories, whether rented or not, consisted almost entirely of bedchambers, with an occasional drawing room, followed by the garret/attic. The kitchen was often the last room surveyed because of its location in the cellar. Although testators presumably chose the most logical course through the dwellings, the similarities among room-by-room inventories reveal a predetermined architectural procession. It is no coincidence that pier tables, when they do show up, are often among the first items catalogued. They were part of a family’s public presentation, a starting point from which testators departed for the quotidian.[19]

Only two of the 214 individuals who owned pier tables in Philadelphia between 1830 and 1850 used them in rooms other than the front parlor. In seven instances pier tables are listed in the front parlor and in another room. This pattern of use should come as no surprise, given that parlors were the locus for display and site for creating first impressions. However, this does not explain why pier tables are so rarely found in other seemingly appropriate spaces, such as the dining room (marble tops were ideal serving surfaces) and entry halls (a popular location for slab tables in the eighteenth century). Since other rooms had piers, what was it about the parlor that made it so suitable for pier tables?

Henry Sargent’s The Dinner Party (1821) and The Tea Party (1824)—two of the best-known depictions of fashionable early-nineteenth-century American interiors—provide clues. Although the paintings are set in Boston and neither depicts a pier table, they show how architectural spaces and household furnishings influenced social activity. The paintings make visible what one scholar has called “the material culture of genteel ambition,” which demanded the display of social knowledge through polite conversation and the complex rituals of sociability. By elucidating the distinctive character of parlor behavior, these paintings hint at how and why pier tables were ideally suited to the parlor but less so to other rooms.[20]

Parlors facilitated social flow. People interacted with quick, superficial contacts and convenient exits. In The Tea Party (fig. 23), guests are clustered around center tables, rows of chairs, and hearths. The arrangement of furnishings prompted the guests to move about, conducting conversations with their neighbors while keeping an eye on the larger scene. In such settings, indirect glances and discreet observation were not only possible but also encouraged by the strategic placement of lighting devices and reflective surfaces.[21]

The source of light in The Tea Party radiates from the center table in the parlor, blocked at the painting’s midpoint by a cluster of two women and a man standing together. The resulting triangular shape of light and shadow is a shrewd artistic device that leads the viewer’s eye into the back parlor, where a large crowd stands between the center table and the pier glass (fig. 24). The reflective quality of the large pier glass suggests the presence of another strong light source, perhaps resting on an unseen pier table, in addition to that on the center table. As Elisabeth Garrett has argued, in the parlors of wealthy, early-nineteenth-century Americans, artificial light, looking glasses, gilded edges, and polished surfaces created drama and facilitated social entertainment. Pier tables embodied all these elements in a single form by supporting lighting devices and having polished surfaces, carving, gilding, metal mounts, and mirrored backs. The tables functioned as a microcosm of the parlor, providing brilliant contrasts between light, color, and surfaces.[22]

Although the outward tone is one of leisure, such parties provided an important avenue for the dissemination of information and power. In a period when credit was still largely based on personal relationships, one’s social reputation was a strategic investment that could open avenues of credit. Household possessions, in addition to economic capital, signified social capital—an investment in the acquisition and display of reputation. In The Tea Party, paintings serve as the major ornaments. The front parlor doubles as a gallery, encouraging close inspection and critical judgments of the paintings: yet such judgments required a large degree of social capital and were confirmed or disavowed in conversation with others. Although the notion of paintings and ornaments as “conversation pieces” is correct, in these outwardly frivolous dialogues people’s reputations could be made or destroyed.[23]

In contrast to the shifting impermanence of parlor sociability, The Dinner Party (fig. 25) depicts a comparatively static environment wherein guests sat in a fixed position throughout the courses of the meal. The food service and servers changed and impressed, but the sitters’ company remained constant. In such a setting, functional side or serving tables were more appropriate than decorative pier tables. Indeed, contemporary domestic guidebooks advised “solid, unpretentious furniture” for the dining room, noting that food, not the furnishings, was the showcase.[24]

Sargent’s paintings elucidate the link between furniture forms and the activities that take place within the architectural space. Compared with the transient male-female exchanges within the double parlors of The Tea Party, the exchanges of the male diners in The Dinner Party are more measured and constant. Pier tables were appropriate to the social conventions of parlors because they provided a fixed arena for the exchange of information. Like the fireplace, pier tables attracted guests by providing light sources such as astral lamps; ornaments such as vases, flowers, shells, and clocks; and glittering reflections produced by the glasses above and below the stone top that created a mini-stage within the home. Unlike chairs and most other table forms, pier tables could not be pulled out from the wall to accommodate guests. Rather, people were forced to negotiate pier tables as they made their rounds, engaging the forms in a superficial manner similar to the pleasantries with which they greeted various guests.

Sargent’s images may be set in Boston, but the culture of sociability he depicted was an international standard. Elite Philadelphians would have understood the rituals as well as prominent Bostonians or, for that matter, Europeans. The Dinner Party depicts the final stage of a dinner party: the tablecloth has been removed for the fruit course. Both the universality of this image and the ubiquitous culture of snap judgments are demonstrated in Robert Waln’s 1819 account of a dinner party in Philadelphia: “By the time the cloth was removed, a few almonds cracked, and an orange or two quartered; I observed glances short, quick, stolen, and expressive, continually passing from the eyes of the guests, to that end of the table where the lady of the house presided.” Fixed exchanges gave way to brief critical encounters in the houses maintained by people of means. Pier tables functioned within this larger performance of gentility, which masked competition behind a veil of manners. Sidney George Fisher alluded to the theatricality of dinner and tea parties among Philadelphia’s elite when he reflected, in 1841, on a small party at Mrs. Israel Pemberton Hutchinson’s “fine new house in Spruce above 10th.” After noting that “their rooms are the most beautiful I ever saw. . . . All the furniture from Paris of the most costly description and in admirable taste and keeping,” he turned his attention to the disjuncture between the lofty architectural setting and the party’s guests:

The furniture in short . . . is just such as you see in palaces in Europe, but the company is very different. Instead of the courtly & high bred crowd, who have been accustomed to this splendor all their lives, you see here merchants & lawyers, who work all day in countinghouses & offices & when then they go into such a house stare about them & seem out of their element. Here it is a show, there the habitual scene of daily life.[25]

Similarly, although pier tables are generally characterized by elaborate decoration and the lavish use of expensive materials, on many American examples much of the effect is superficial. Freehand gilding and stencils substituted for ormolu brass; thin veneers of exotic woods were glued to cheap secondary woods; black paint emulated ebony; bronze powder gave the illusion of gilt surfaces; and green and gold paint simulated the patina on antique bronze. When combined with looking glasses and lighting devices, the whole arrangement produced a dazzling effect—the illusion of space, wealth, and light.

A major function of pier tables was to facilitate the small talk or gossip essential to business and social advancement (sociability), but what, specifically, did that entail? Because trade centered on personal credit and was an inherently risky endeavor, merchants saw significant financial incentives in having intimate knowledge of their peers. Merchants and businessmen were constantly sizing up one another, trying to determine who was or was not a good credit risk. According to historian Thomas Doerflinger, “In such appraisals the man and the merchant were inseparable . . . not only were the liquidity and net worth of a trader taken into account but also many details about his business and private life.” Punctuality and prudence were the most significant attributes that made someone credit-worthy: a trader/businessman was deemed successful if he paid his debts on time (punctuality) and always had cash on hand to be able to seize new investment opportunities (prudence).[26]

Pier tables helped their owners look and act the part of a successful and, more important, dependable professional. Pier tables can be understood as highly charged social symbols that worked on multiple levels: the material, in which they conveyed status while facilitating critical glances and determining movement within a room; and the symbolic, in which they evoked financial security and hereditary distinction. Status was not a birthright in republican America, and thus self-performance was crucial to securing credit and encompassed everything from one’s house to one’s deportment. Indeed, as articles of consumption became increasingly available, it was not enough merely to look the part; one had to act the part as well.[27]

This helps explain why ownership of pier tables correlates so closely to ownership of pianos despite the fact that pianos were consistently valued forty to one hundred percent higher than pier tables (see Table 3, fig. 26). Pianos and pier tables had several things in common: as luxury items, they were not only important elements in entertaining while imparting a degree of social panache but also key instruments in courtship. In Philadelphia, marriage was the fastest means to join the highest strata of society, particularly because so much property ownership was inherited. A father’s one-hundred-dollar investment in a pianoforte might be a shrewd investment if it enabled his daughter to marry well. Though they operated in a less overt way, pier tables functioned in this arena as well, as is illustrated in a story published in Philadelphia in 1831:

Mr. Nathaniel Doolittle was a grocer in the upper part of the city. . . . One would have judged from an inspection of the premises, that Nathaniel drove but a small business—sufficient barely to support a bachelor of moderate pretensions. But appearances are frequently deceitful—the door that led out of the shop, opened into as pretty a parlour as any in Broadway. On one side were a mirror and a pier table—opposite, reclined a sofa, flanked by a couple of rocking chairs; on a third side, stood an upright piano of the latest fashion.

The protagonist, a bachelor intent on winning Mr. Doolittle’s daughter, ascertains the family’s status from a brief glance around the parlor, which is furnished in the most up-to-date style. Nonetheless, he still feels compelled to talk with brokers to determine Mr. Doolittle’s commercial standing, hinting at the limitations of material display. In other words, one needed the entire package of cultured refinement—furnishings, manners, property, and contacts—to establish one’s reputation. As this story implies, owning a pier table did not conclusively demonstrate a person’s financial stability. However, these objects were important tools in the performance of sociability that secured one’s financial and social standing.[28]

Given that merchants, accountants, lawyers, and other professionals were in the business of personal transactions, a furniture form that facilitated brief, indirect evaluations of others was suitable, if not mandatory. With a single glance at the quality and condition of a pier table’s marble top, a visitor could register key information about the owner’s financial and cultural status and draw a positive or negative conclusion. In 1850, for example, a Mrs. Swisshelm offered a biting critique of the furnishings in the East Room at the White House: “The centre and pier tables, the sofas and chairs would suit a second rate ice cream saloon.” Similarly, a story in an 1853 periodical conveyed the heroine’s faded circumstances by highlighting the decrepit state of her formerly elegant drawing room, signified when “a slovenly man servant in a ragged shirt and trousers” brought in “a guttering tallow candle stick in a mildewed silver candlestick, which he sat upon a dusty, stained, and spotted marble pier table.” The author cites material indicators of a downturn in wealth and status: a noxious and smoky tallow candle sits on the pier table’s dirty marble top, where presumably once a bright oil lamp shone on a gleaming, elegant marble surface. The use of a derelict pier table is a particularly potent device given the form’s associations with elegance, wealth, and permanence.[29]

Cultures of Competition

Pier tables were a component in the display of status, yet their efficacy depended and built on several forms of capital. Jacob Eichholtz (1776–1842) provides an instructive case study, for, with the help of pier tables, he literally transplanted Philadelphia elite society into the hinterlands. An established portrait painter in his native town of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Eichholtz moved to Philadelphia in 1823 in search of more patrons and greater acclaim. Starting out in rented quarters, he quickly prospered and began acquiring property. By 1831 Eichholtz owned at least three houses, one of which he rented to his son-in-law. In this regard, he was typical of many wealthy Philadelphians who found rental property a reliable and profitable source of income that supported other, riskier entrepreneurial ventures.[30]

When he returned to Lancaster in 1832, Eichholtz utilized his associations with Philadelphia to impress the locals. He moved his family into a brick row house modeled on the prevailing fashions in Philadelphia and furnished it in the latest style. No household object better communicated Eichholtz’s intimate knowledge of urban fashion than his pier table. Writing from Lancaster to his daughter in Philadelphia in 1832, he noted: “The pier table is much admired by . . . all who have seen it. I now appear to take precedence in all matters of taste here.”[31]

A pier table (fig. 27) that descended in Eichholtz’s family is likely the one mentioned in his letter. It displays classic Philadelphia features: a cavetto molding on the apron; turned wood columns and applied rear pilasters; ogee-shaped lower shelf; pie-wedge mahogany veneers within a gilt semicircular border; turned rear feet; and a gadrooned ring above lion’s-paw front feet. As was proper custom in Philadelphia, Eichholtz placed the table in the window pier of the front parlor. In his lifetime the flanking windows looked across open fields toward Philadelphia, not only the location of the pier table’s manufacture but also the source of Eichholtz’s standing in Lancaster.[32]

Eichholtz may not have grown up with pier tables, but he learned about them from his important patrons. For instance, a pier table features prominently in his 1827 portrait of Mrs. John Frederick Lewis of Philadelphia, completed only a few years before Eichholtz wrote to his daughter about the reception of his own pier table in Lancaster (fig. 28). Though the staging follows the prevailing portraiture conventions of the period, Mrs. Lewis’s silk dress and the pier table on which she leans were likely her own possessions. The pier table’s white marble top, gilt decoration, and polished Ionic columns would have made it a fashionable and desirable object in 1827.[33]

The sitter’s husband, John Frederick Lewis, was an auctioneer and East India merchant. His personal and professional success depended on an intimate knowledge of international markets and the ability to grant and secure credit and contacts. Both Lewis and Eichholtz were emblematic of professionals and businessmen in competitive trades: each used pier tables to convey cosmopolitan taste, financial security, and well-managed households, all key factors in securing credit. These tables evoked not just a world of elites but also of professionals engaged in trade.[34]

The most famous and best-documented Philadelphia pier table commission occurred in 1829, when Andrew Jackson ordered four pier tables with white Italian slabs and three center tables with black and gold marble slabs from cabinetmaker Anthony G. Quervelle (fig. 29). Jackson used the tables to furnish the newly finished East Room in the White House, which, as the major audience or reception room, was the largest room in the building and required suitably fashionable and awe-inspiring furnishings to simultaneously impress and intimidate visitors.[35]

From a cabinetmaking perspective, Quervelle’s White House commission offers an intriguing business model. Faced with the challenge and honor of supplying the president’s furnishings, Quervelle had significant incentive to deliver pieces that were both stylish and distinctive. He chose scrolled monopodia front supports embellished with an eagle’s head at the top in direct reference to the Great Seal of the United States. The original bill of sale lists the four pier tables at $700.00 and the three center tables at $335.00. By comparison, in 1830 the household furnishings of a typical Philadelphia family totaled $535.00 (see Table 4). The pier tables stood under “4 Pier Looking-glasses, in rich gilt frames, 108 by 54 inches” that cost an astounding $2,400.00. A visitor to the newly furnished East Room in 1830 reported:

Each pier is filled with a beautiful pier table, richly bronzed and gilt, corresponding with the round tables—each table having a lamp and pair of French china vases with flowers and shades agreeing with those on the mantels. The curtains are of blue and yellow moreen, with a gilded eagle, represented as holding up the drapery, which extends over the piers.[36]

If the White House examples were unusually large for American pier tables, their dimensions were in keeping with comparable European forms. The East Room provided one of the few architecturally appropriate settings for pier tables in America, akin to the long, formal drawing rooms of state apartments and royal palaces in Europe. Congressman Levi Lincoln made just this point in 1840, in defense of the expenditures for White House furnishings: “the spacious halls and lofty ceilings of such a mansion require much, which would be suited to no other residence.”[37]

On a more domestic scale is a pier table with ties to the Wilkins family of Pittsburgh (fig. 30). A lawyer by trade, William Wilkins (1779–1865) served as a judge, a United States senator, and secretary of war under President Zachary Taylor. Wilkins’s success, like that of many pier table owners, was based on personal connections and his ability to grant and receive credit. Wilkins was one of the original financial backers of the Pittsburgh Manufacturing Company, which became the Bank of Pittsburgh in 1814. His marriage four years later to Mathilda Dallas, daughter of politician and judge Alexander J. Dallas of Philadelphia, further strengthened his economic position while providing key political clout. Mathilda brought to the marriage an enormous family fortune, and her family ties and subsequent cultural affiliations with Philadelphia may have prompted the Wilkinses to purchase a Philadelphia-style pier table for their home in Pittsburgh during the late 1820s or early 1830s.[38]

The Wilkinses’ prominent family ties and political associations made them ideally suited to pier table ownership, for the form conveyed cosmopolitan taste, financial security, and ambitious hospitality. Furthermore, it is possible that William Wilkins bought a pier table in an explicit attempt to align himself politically with the White House. The scroll-paw front supports on his table are similar to (albeit less refined than) those on the White House tables. Wilkins was elected to the Senate in 1831, and he would have been familiar with Quervelle’s tables by that time at the latest. He also supported President Jackson’s controversial decision to withdraw federal deposits from the Second Bank of the United States in 1832, severing ties with the bank’s president, Nicholas Biddle, in 1834. The next year, Wilkins acknowledged his loyalty to Jackson with the construction of Homewood, an enormous Greek revival mansion in Pittsburgh. The conceptual model was The Hermitage, the mansion built outside Nashville by Andrew Jackson, who himself owned a pair of Philadelphia pier tables by the firm Barry and Krickbaum (fig. 31).[39]

Both the Wilkinses’ table (fig. 30) and the table illustrated in figure 19 are distinguished by lower shelves with an inset marble well. One theory holds that the recess was intended to receive a wine cooler. However, no Philadelphia inventory between 1830 and 1850 lists bottle or liquor chests near pier tables. It is reasonable to conclude that the waterproof marble recess was meant for urns, flower vases, and other “ornaments,” which are listed next to pier tables in inventories and depicted in design books and interior scenes.[40]

According to tradition, the pier table illustrated in figure 32, a mate, and a matching center table with carved dolphin supports were made for the Nashville, Tennessee, home of Henry Middleton-Rutledge and his wife, Septima Sexta Middleton. At forty-four inches high, the table is unusually tall, intended for a large-scale Greek revival interior. The Rutledge table is meant to dazzle; it was as much a showpiece for the warehouse that made it as it was for the patron. The cornucopia brackets under the apron are an explicit reference to abundance and wealth. Similarly, the elaborately carved and gilt dolphin supports—a classical reference to success and safety at sea—identify this table as a distinctive and therefore expensive commission.[41]

The Rutledge table represents the combined efforts of several different and highly specialized crafts. It took at least one cabinetmaker to construct the frame and apply the exotic wood veneers; carvers to produce the lion’s-paw feet, dolphin front supports, acanthus pilasters, scrolled cornucopia brackets, and gadrooned moldings; various specialists to create the gilded and vert antique decoration; and still others to import and finish the glass plate and marble slab top. This table represents the consolidation of several different trades, thus explaining why pier tables were overwhelmingly produced in or around urban centers.[42]

Owing to the number of hands and specialist shops involved, construction practices vary even among labeled pieces. Many Philadelphia cabinetmaking firms were large enough to employ specialized tradesmen, but some found it cheaper to purchase components and services from the numerous smaller shops located in the lower-rent districts away from the Delaware waterfront and Philadelphia County. Consequently, a large shop could acquire turned and carved components from specialized shops around the city, add the top, apply gilding, vert antique, and other decorative finishes, and market the table as its own.[43]

By the 1830s commentators noted the ease with which fashionable furniture could be procured. In Philadelphia, this was the result of several separate but related factors: improvements in transportation, increased furniture production, growing population, the construction of Greek revival buildings with larger interiors and double parlors, and more public auctions at which consumers could procure fashionable goods secondhand. The latter phenomenon was the subject of an 1832 article:

If men or women are anxious to spend money in a very agreeable way, in a large city like Philadelphia they have only to attend the auctions. . . . It is surprising what a change of household commodities there is in Philadelphia. A housekeeper may go out any morning and buy a new sofa or pier table at auction, have it home before dinner, and the old one at the store ready for sale the next day. Thus she can have two excitements—one in buying, and the other in bidding up her cast off furniture—nay, a third, for in the afternoon she can admire her purchase, and if not perfectly satisfied, call a hand-barrow and whisk it off to the next “great sale.” This is the secret of those never ending advertisements of furniture.

The ease with which large forms such as pier tables and sofas could be transported is notable, as is the sheer abundance of goods in the city. Philadelphia was, after all, a major manufacturing center in the first half of the nineteenth century.[44]

During the early 1800s chairmakers and cabinetmakers in urban areas looked beyond local markets to sustain operating costs. With higher rents and overhead in the city, it was imperative to produce readily salable goods, or to make salable what had already been produced. Large firms held periodic auctions to clear out their inventory and storage rooms, while other makers shipped goods on venture and attempted to sell them at public auction in distant markets. New York makers of pier tables dominate the extant auction notices in Southern locales, reflecting both the larger scope of the New York cabinetmaking trade and the tight connections between New York cotton merchants and Southern planters. The coastal shipping records for Philadelphia reveal that chairs dominated the export trade, whereas tables constituted only a tiny fraction of the total. Unable to compete directly with New York’s coastal trade, Philadelphia makers seem to have focused on inland markets, sending their wares west and then down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.[45]

Pier tables passed out of favor after midcentury, replaced in form and terminology by curvilinear console tables, which often did not incorporate mirrors. The later form whose function most closely approximated that of pier tables was the étagère or whatnot—a large, opulent, and almost purely decorative object (fig. 33). Three related factors contributed to the demise of the pier table. The advent of gas lighting fixtures in the late 1830s and early 1840s, which were attached directly to the wall or ceiling, reduced the tables’ function as a glorified lighting stand. Similarly, the stone tops long associated with the form became more common as marble production increased, thus lowering both the cost and distinctiveness of stone tops. Finally, improvements in glass plate production increased the availability of larger pier glasses that extended almost from the ceiling to the floor (fig. 34).

Large plate glass was available in America by the late 1830s, and according to an observer several decades later, that commodity spelled the end of pier tables with mirrors in America. The authors of Beautiful Homes: or, Hints in House Furnishing, published in 1878, reflected:

Parlor tables, thirty years back, consisted in the inevitable “center-table,” and what was termed a “pier-table,”; the latter being a sort of ornamental stand with three sides and a plain back, placed flat against the wall beneath the “pier-glass,” which the long, narrow mirror was termed. This table was some four feet in height, with marble slab, and generally richly ornamented with carving and gilding, but it was an exceedingly stiff and ungraceful looking piece of furniture. A few years later, the “pier-table” was superseded by the gilded and marbletopped mirror-bracket, introduced for the accommodation of the now extended mirror which reached from the ceiling to the floor, but the popular center-table still held its place.[46]

The study of material culture boils down to a single question: Why do things look the way they do? In the early nineteenth century, pier tables served an important ceremonial function: they simultaneously signified hospitality and business, equality and competition. It is no coincidence that the form remains in currency within the hotel industry, where hospitality and business collide (fig. 35). Similarly, among private residences, the use of wall-oriented tables with accompanying mirrors and lighting devices persists even in the age of electric lighting. When today’s homeowners and decorators place a fixed table against the wall beneath a mirror with lamps or candles on top, they are continuing—like pier table owners in the first half of the nineteenth century and whether they know it or not—a tradition that has its roots in French and Italian court culture.

Pier tables make little sense in the world of modernism, where utility, sleek proportions, and mobility are treasured. The fact that these tables are so out of place in modern society helps convey just how different the world for which they were created was from our world today. The sheer size and weight of pier tables are major inhibitors today, yet their size and immovability were precisely what made these tables so desirable to their original owners. These tables of sociability are products of an entirely different time, aesthetic, and ideology. Though their massiveness and materials staked claims to order, stability, and permanence, their ornament and use encouraged fleeting encounters and quickly made judgments. In this last regard, pier tables are perhaps victims of their own success: few people today give them a second thought.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the author thanks J. Ritchie Garrison, Morrison Heckscher, Peter Kenny, and Amelia Peck.

Pier tables also exhibit some regional variations in construction. In New York pier tables, the rear stiles often join the top and bottom rails via a single large dovetail, while in Philadelphia, mortise-and-tenon joints were favored. See Charles L. Venable, American Furniture in the Bybee Collection (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), pp. 106–7, 124–25; and Robert C. Smith, “The Furniture of Anthony G. Quervelle, Part I: The Pier Tables,” Antiques 103, no. 5 (May 1973): 984–94.

Venable, American Furniture in the Bybee Collection, p. 123. Peter M. Kenny, Frances F. Bretter, and Ulrich Leben, Honoré Lannuier, Cabinet Maker from Paris: The Life and Work of a French Ebéniste in Federal New York (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), p. 45. The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices (1828) diagrams card, breakfast, and loo (center) table feet, but there is no mention of pier tables. Presumably, feet for pier tables were interchangeable with feet for other tables, yet their absence in the price book indicates that the form remained rarefied in the late 1820s. Also see Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “Philadelphia Furniture in the Empire Style,” Antiques 171, no. 4 (April 2007): 92–101.

The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices lists a plain pier table frame as 40" high. Also see Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, p. 81. Both Jacob Eichholtz and Andrew Jackson owned Philadelphia pier tables with wood Ionic columns that corresponded to the marble Ionic columns on their parlor fireplace surrounds.

Carl Peter Kaellgren, “Stately and Formal: Side, Pier and Console Tables in England, 1700–1800” (Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 1987), pp. xxi, 31, 32; Peter Thornton, Authentic Décor: The Domestic Interior, 1620–1920 (New York: Viking Press, 1984), pp. 52–53; and Elisabeth Donaghy Garrett, At Home: The American Family, 1750–1870 (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1989), pp. 153–55.

For more on the Buckland tables, see Luke Beckerdite, “Architect-designed Furniture in Eighteenth-Century Virginia: The Work of William Buckland and William Bernard Sears,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 37–43. For more on the Philadelphia tables, see Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Table’s Tale,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 34–35; and Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992), pp. 191–93.

Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London, 1793–1802; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1972), p. 152; and George Hepplewhite, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 1794; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1969), p. 12.

The Lannuier pier table retains its original casters, suggesting that it was mobile and hence doubled as a serving table. It is illustrated and discussed in Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, pp. 50, 69–70. For Baltimore examples, see William Voss Elder III and Jayne E. Stokes, American Furniture, 1680–1880, from the Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1987), pp. 159–62. For a Boston example in which slight differences in the table’s construction, not the overall form itself, signify its intended use as a pier table, see Robert D. Mussey, The Furniture Masterworks of John and Thomas Seymour (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2003), p. 289.

The 1836 catalogue of the John Hare Powel sale clarifies the period terminology in America. In the saloon were “2 Massive Pier Table, entirely of breschia marble, supported by carved consols, with mirror backs and ebony frames, made in Paris.” See Kathleen Catalano, “Cabinetmaking in Philadelphia, 1820–1840” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1972), p. 107; Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, p. 81; and Catalogue of the Household Furniture, Part of the Books, Plate, Wine, &c. of Col. J. Hare Powel, to be Sold at Public Sale . . . April 19, 1836, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, no. 1582, box 23, folder 19.

Sheraton, Drawing-Book, pp. 141–42. The phrase “antique taste” is taken from Pierre de la Mésangère, Collection de meubles et objets de goût (1802). Rudolph Ackermann, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics. 12, no. 69 (September 1828): 182.

On the Barry pier tables, see Catherine Ebert and Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “From Apprentice to Master: The Life and Career of Philadelphia Cabinetmaker George G. Wright,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 113–19; and Donald L. Fennimore and Robert F. Trump, “Joseph B. Barry, Philadelphia Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 135, no. 5 (May 1989): 1212–25. On the polyglot character of American classical furniture, see Donald L. Fennimore, “American Neoclassical Furniture and Its European Antecedents,” American Art Journal 13 (Autumn 1981): 49–65. For sources of classical inspiration, see Wendy A. Cooper, Classical Taste in America, 1800–1840 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1993), pp. 26–73, 130, 142. Also see Joan Woodside, “French Influences in American Furniture as Seen through Pierre de la Mésangère’s Meubles et objets de goût, 1802–1835” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1986).

I am indebted to Elizabeth White for this observation. For a pictorial survey of pier groupings, see Samuel J. Dornsife, “Design Sources for Nineteenth-Century Window Hangings,” Winterthur Portfolio 10 (1975): 69–99.

J. Ritchie Garrison, Two Carpenters: Architecture and Building in Early New England, 1799–1859 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), p. 98. Also see Bernard L. Herman, Town House: Architecture and Material Life in the Early American City, 1780–1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), pp. 3–4.

As testament to the durability of stone tops, Eliza Leslie advised: “Tables, &c., with marble tops, though the most costly at first, will be found, perhaps, cheapest in the end. They are easily kept clean, by merely wiping them every day with a soft cloth, and a flannel; they require no cloth to cover them, and there is no danger of their splitting or warping with the heat.” Miss Leslie, The House Book: or, a Manual of Domestic Economy for Town and Country (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1841), p. 192. Archives of Useful Knowledge, a Work Devoted to Commerce, Manufactures, Rural and Domestic Economy, Agriculture, and the Useful Arts 2, no. 2 (October 1811): 207.

The House Servant’s Directory (Boston, 1828), as quoted in Major L. B. Wyant, “The Etiquette of Nineteenth-Century Lamps,” Antiques 30, no. 3 (September 1936): 114. Also see Garrett, At Home, pp. 140–62.

The percentages and averages given are based only on usable inventories, meaning that the inventory included information about the owner’s wealth and/or furnishings. Inventories suggest that outdated tables were moved upstairs and, likely owing to their water-resistant stone tops, reused as dressing or toilet tables. I have only counted references to “pier” tables as conclusive evidence of ownership. This almost certainly omitted some pier tables listed under another heading, such as “marble top table” or “side table,” but I believe pier tables were such a distinctive form that they were rarely conflated with generic tables. For urban population statistics, see Campbell Gibson, “Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990,” June 1998, Population Division Working Paper No. 27, U.S. Bureau of the Census. My table is a modified version of these data, which are available at http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027.html (accessed March 29, 2007). The “Philadelphia” population includes that for Kensington, Southwark, Northern Liberties, Spring Garden, and Moyamensing, all of which are represented in the probate inventory sample.

Thomas M. Doerflinger, A Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise: Merchants and Economic Development in Revolutionary Philadelphia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), pp. 11–69.

Donna Rilling, Making Houses, Crafting Capitalism: Builders in Philadelphia, 1790–1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 7, 42–49. Wills, County of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1682–1875, will no. 45 (1847): Mic 959–135, Downs Collection, Winterthur Library.

Wills, County of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1682–1875, will no. 197 (1839): Mic 959–1355, Downs Collection, Winterthur Library. Many owners of pier tables invested heavily in burgeoning transportation networks. See David Meyer, The Roots of American Industrialization (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), pp. 28–29; and Bruce Laurie, Working People of Philadelphia, 1800–1850 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980), pp. 8–9.

Beatrice B. Garvan, Federal Philadelphia, 1775–1825: The Athens of the Western World (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987), p. 15.

Charlotte Gere, Nineteenth-Century Decoration: The Art of the Interior (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1989), p. 153; Garrett, At Home, pp. 46–47; Cooper, Classical Taste in America, pp. 38–39; and Herman, Town House, p. 36.

On parlor sociability, see Garrett, At Home, pp. 39–77.

Ibid., p. 46.

Herman, Town House, p. 201.

William Parkes, Domestic Duties, or, Instructions to Young Married Ladies: On the Management of Their Households and The Regulation of Their Conduct in the Various Relations and Duties of Married Life (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1829), p. 173.

Both The Tea Party and The Dinner Party were exhibited in Philadelphia. See Cooper, Classical Taste in America, p. 92. Garrett, At Home, p. 82. Robert Waln Jr., The Hermit in America on a Visit to Philadelphia, edited by Peter Atall (Philadelphia: M. Thomas, 1819), p. 102. Nicholas B. Wainwright, ed., A Philadelphia Perspective: The Diary of Sidney George Fisher Covering the Years 1834–1871 (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1967), pp. 116–17.

Doerflinger, A Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise, p. 18.

At the 1819 dinner party in Philadelphia, a guest discreetly informed Robert Waln about another member of the party: “He belongs to a pretty numerous class, existing in our city, which, by birth, is entitled to hold a situation in the first ranks of society. Nor are its members wanting in the education and polish so essential to the finished gentleman. Presuming upon these qualities, birth, education, and fortune,—they take (and, what is worse, are permitted to take) liberties in conversation with ladies, which no birth, no talents, no gold can warrant, or excuse.” Waln, The Hermit in America, pp. 115–16. On self-performance and manners, see David Shields, Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), pp. xxvi–xxvii, 275–307; Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), pp. 79–80; and C. Dallett Hemphill, Bowing to Necessities: A History of Manners in America, 1620–1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 84–85.

“Extract from the Diary of a Bachelor,” Philadelphia Album and Ladies’ Literary Portfolio (October 15, 1831): 5, 42. For more on credit, see Rosalind Remer, Printers and Men of Capital: Philadelphia Book Publishers in the New Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), pp. 50, 100–101.

“The White House,” Saturday Evening Post 29 (May 18, 1850); and “Mark Sutherland: or, Power and Principle,” National Era 5, no. 342 (June 21, 1853): 113.

Thomas R. Ryan, “Defining Jacob Eichholtz,” in The Worlds of Jacob Eichholtz: Portrait Painter of the Early Republic, edited by Thomas Ryan (Lancaster, Pa.: Lancaster County Historical Society, 2003), p. 12.

Ibid., pp. 14–16.

In the 1940s a “Leaman” gave the pier table to the James Buchanan Foundation for the Preservation of Wheatland in memory of her father—most likely rifle manufacturer Henry Eichholtz Leman (1812–1887) of Lancaster, who was Jacob Eichholtz’s nephew. See object file, James Buchanan Foundation, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Ryan, “Defining Jacob Eichholtz,” p. 19.

For more on the relationship between comportment and gentility, see Bushman, Refinement of America, pp. 61–69.

Ryan, ed., The Worlds of Jacob Eichholtz, p. 122. According to the household inventory taken at her death in 1865, “Eliza Lewis, widow of John F. Lewis,” had two marble-top tables in her parlor, valued at $45.00 and $12.00, respectively. The $12.00 table is most likely the ca. 1827 pier table in Mrs. Lewis’s portrait, while the table valued at $45.00 is probably a newer model. Also listed in the inventory is a solitary “framed portrait” valued at $2.00, which could be the Eichholtz portrait. Wills, County of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1682–1875, will no. 406, 1865 (bk. 55, p. 549), August 19, 1865, Downs Collection, Winterthur Library.

In furnishing the East Room with pier tables, President Jackson continued a tradition started by James Madison, who purchased an elaborate gilt pier table by French cabinetmaker Pierre-Antoine Bellangé in 1817. For more on Quervelle’s White House commission, see Betty C. Monkman, The White House: Its Historic Furnishings and First Families (New York: Abbeville Press, 2000), pp. 63, 82–83.

The author thanks Melissa Naulin and William G. Allman for sharing the object file with condition notes on the Quervelle pier table at the White House. An engraving in Gleason’s Pictorial from May 6, 1856, and a ca. 1861 lithograph offer early depictions of the East Room and provide clear evidence of Quervelle’s pier tables with scrolled front supports. They are reproduced in Monkman, The White House, pp. 181–82. For Quervelle’s White House commission, see Robert C. Smith, “Philadelphia Empire Furniture by Antoine Gabriel Quervelle,” Antiques 86, no. 3 (September 1964): 304–9; Monkman, The White House, p. 286; and Catalano, “Cabinetmaking in Philadelphia,” pp. 56, 113. For the White House furnishings, see “Speech of Mr. Ogle: From Lewis Vernon & Co. Voucher No. 6. Private Office,” Investigator and Expositor (1839–1840), September 1, 1840, 0,_1, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.metmuseum.org:80/ (accessed March 3, 2008). For the 1830 visitor’s full report on the East Room, see “The East Room,” Nile’s Weekly Register (1814–1837), January 2, 1830, 290, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.metmuseum.org:80/ (accessed March 3, 2008). For a splendid critique of the White House furnishings, see Mrs. Swisshelm, “Article 5—No Title,” Saturday Evening Post (1839–1885), May 18, 1850; 0_002, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.metmuseum.org:80/ (accessed March 3, 2008).

Speech of Mr. Levi Lincoln of Massachusetts, April 16, 1840, as quoted in Monkman, The White House, p. 94.

The current owner purchased the table from a member of the Pleasants family. The Pleasants married into the Wilkins family in the twentieth century. See John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes, eds., American National Biography, 24 vols. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 23: 399.

Ibid. Homewood was demolished in 1924. See Franklin Toker, Pittsburgh: An Urban Portrait (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1986), p. 221. According to Marsha Mullin, Chief Curator/Director of Museum Services at the Hermitage, the pier tables were probably purchased in Philadelphia from the firm of Barry and Krickbaum in February 1837, when the Jacksons were refurnishing the Hermitage mansion after a fire. The February 9, 1837, invoice from Barry and Krickbaum for two pier tables at $60.00 each is published in Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, edited by John Spencer Bassett, 7 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1926–1935), 5: 459.

Most bottle chests are far too large to fit on the inset marble recess occasionally found on pier tables with mirror backs. See Alexandra Alezivatos Kirtley, “A New Suspect: Baltimore Cabinetmaker Edward Priestly,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 100, 119–21; Fennimore and Trump, “Joseph B. Barry,” p. 1223.

Object file, acc. 1975.191, Winterthur Museum. The Middleton-Rutledge House was converted into apartments in the 1920s, but the chair rails in surviving sections indicate the original grand proportions. For a view of the present-day first-floor hallway, see http://mywebpages.comcast.net/jimrv6/index.html (accessed March 3, 2008).

For lists of cabinetmakers working in Philadelphia during the early nineteenth century, see Catalano, “Cabinetmaking in Philadelphia”; Deborah Ducoff-Barone, “The Early Industrialization of the Philadelphia Furniture Trade, 1800–1840” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1985); Deborah Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers, 1800–1815,” Antiques 134, no. 5 (May 1991): 982–85; and Deborah Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers, 1816–1830,” Antiques 145, no. 5 (May 1994): 742–55. For features associated with Quervelle, see Smith, “The Furniture of Anthony G. Quervelle, Part I,” pp. 984–94. On the dangers in attributing furniture to Quervelle, see Thomas Gordon Smith, “Quervelle Furniture at Rosedown, in Louisiana,” Antiques 160, no. 2 (May 2001): 772; and Anna Tobin D’Ambrosio, ed., Masterpieces of American Furniture from the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1999), p. 59.

A significant number of small shops manufactured, but did not market, their own wares, and most specialist carvers and turners worked for several different cabinetmakers. See Ducoff-Barone, “Early Industrialization,” pp. 23, 46, 62–63.

“The Town Tatler—no. 27,” The Ariel: A Semimonthly Literary and Miscellaneous Gazette (1827–1832), June 9, 1832, 50, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.metmuseum.org:80/ (accessed March 3, 2008). To transport these heavy forms, cabinetmakers employed furniture cars with attendants. Private citizens could also rent cars from cabinetmakers when moving household furniture or taking goods to or from public auction. See Ducoff-Barone, “Early Industrialization,” p. 181. Perhaps the best indication of the dramatic changes experienced by the Philadelphia furniture industry in the antebellum period is the fact that the 1850 city directory lists almost as many furniture warerooms (65) as individual cabinetmakers (79). John Downes, Bywater’s Philadelphia Business Directory and City Guide for the Year 1850 (Philadelphia: Maurice Bywater, 1850). For more on Philadelphia’s industrial and banking prowess in the nineteenth century, see Doerflinger, A Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise, p. 5; and Sam Bass Warner, The Private City: Philadelphia in Three Periods of Its Growth (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987), pp. 47–160.