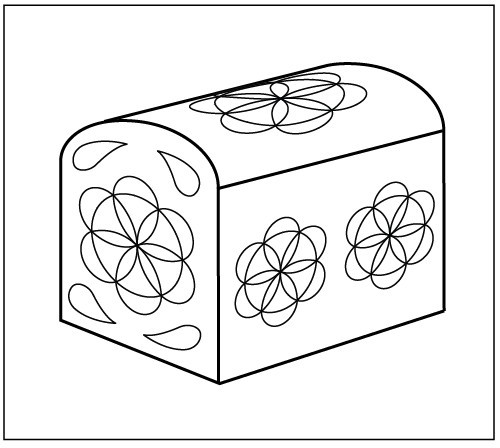

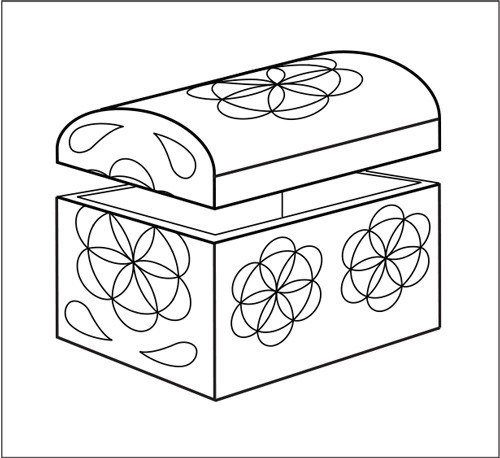

Composite illustration showing Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar, pine. H. 5 1/8", W. 6 3/8", D. 4 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Composite illustration showing Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar. H. 6 3/4", W. 10", D. 6 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Composite illustration showing Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar, pine. H. 11 1/8", W. 14 7/8", D. 11 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

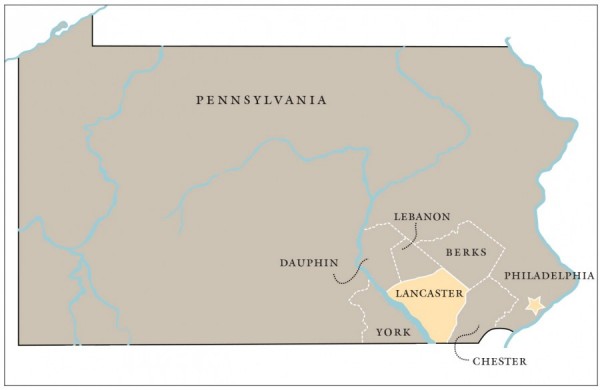

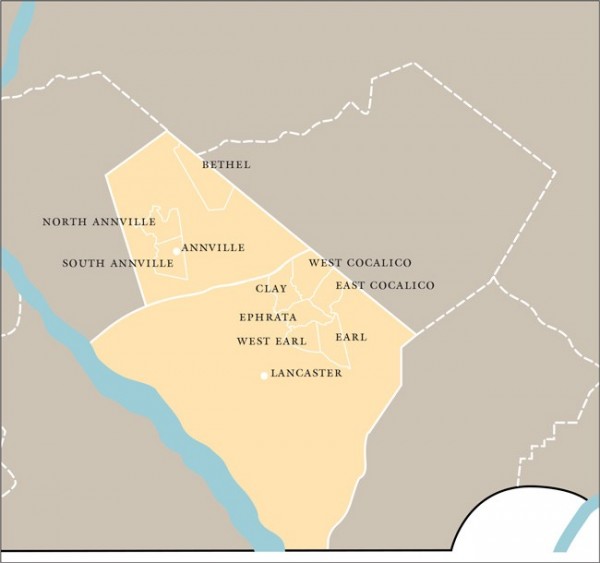

Map of southeastern Pennsylvania highlighting Lancaster County and environs.

Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar. H. 12 1/2", W. 16", D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1785–1820. Pine and oak. H. 24", W. 49 1/2", D. 22 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Olde Hope Antiques, Inc.)

The American Corner in Elie and Viola Nadelman’s Museum of Folk Arts, Riverdale, New York, late 1920s. (Courtesy, Cynthia Nadelman.)

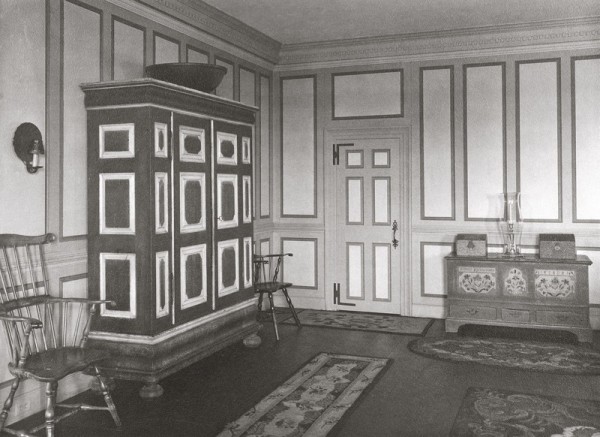

Entrance hall at Chestertown House, Southampton, Long Island, ca. 1928. (Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Winterthur Archives.)

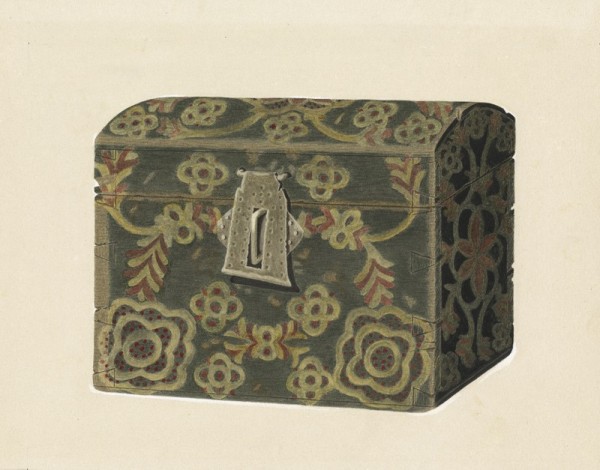

Carl Strehlau, “Pa. German Chest,” Index of American Design, ca. 1940. (Courtesy, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Carol Larson, “Wood Box or Chest,” Index of American Design, ca. 1937. (Courtesy, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) 8

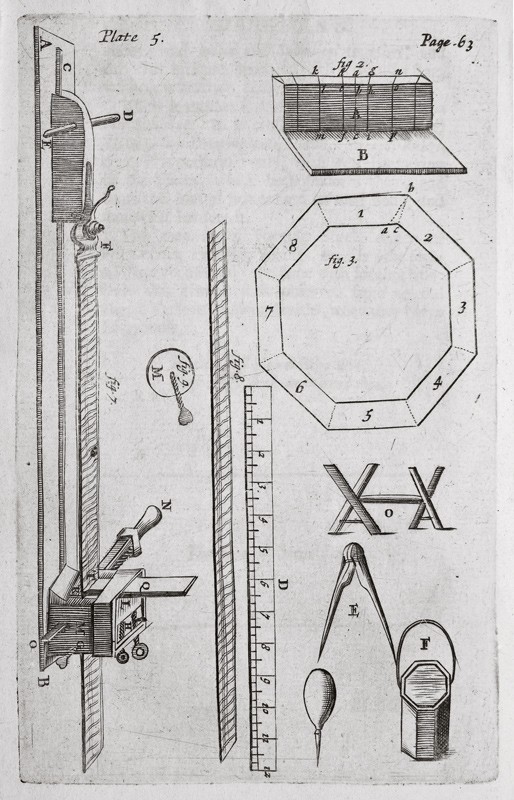

Plate 5 from Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises (1678). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Painted chest, vicinity of Ortenburg, Bavaria, Germany. Materials and dimensions unrecorded. (Private collection; photo, Callwey Verlag.)10

Box, probably Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1744. Pine. H. 11 7/8", W. 7", D. 5 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The painted initials on the lid suggest that the box was made for Antje Luyster of Monmouth County.

Detail of the compass-generated inlay on a drawer from a chest of drawers, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1730–1750. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

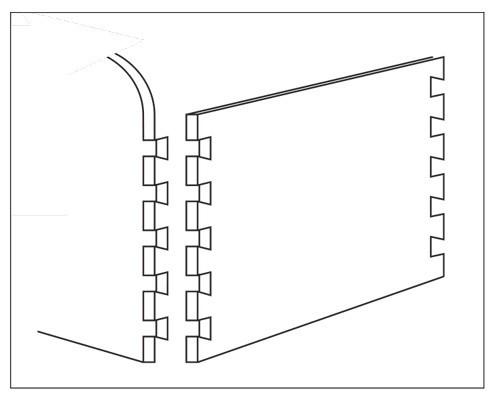

Line drawing showing how the front, side, and back boards of the dome-top boxes are dovetailed together.

Detail showing the pinned bottom board of a box not illustrated in this article. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

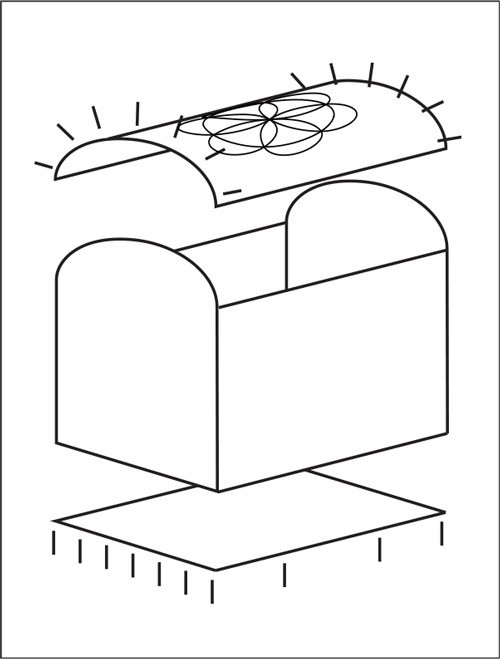

Line drawing showing how the top and bottom boards of the dome-top boxes are attached with small wooden pins.

Line drawing showing how compass-work motifs were scribed on dome-top boxes.

Line drawing showing how the dome-top boxes were sawn into two sections after the scribing was complete.

Detail of a bisected dovetail on the blue box illustrated in fig. 1b. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the alignment batten inside the large red box illustrated in fig. 1c. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

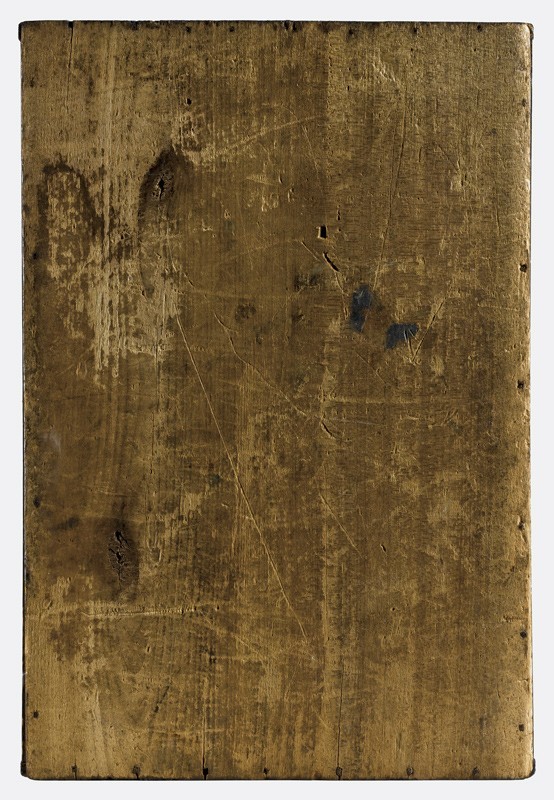

Detail of the bare wood behind the replaced escutcheon plate on the large red box illustrated in fig. 1c. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing interior paint drips and a hinge on the small red box illustrated in fig. 1a. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the escutcheon and underside of the hasp on the small red box illustrated in fig. 1a. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

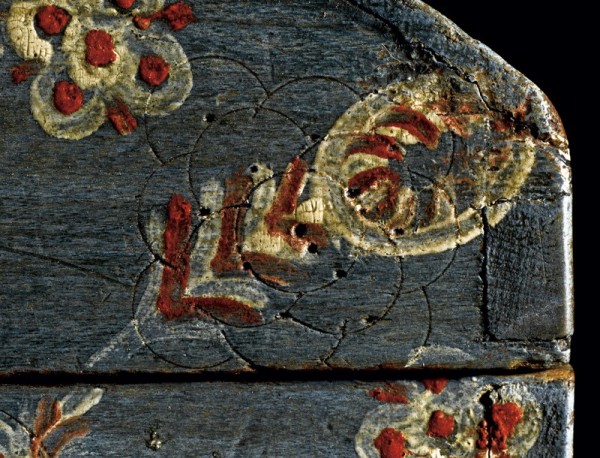

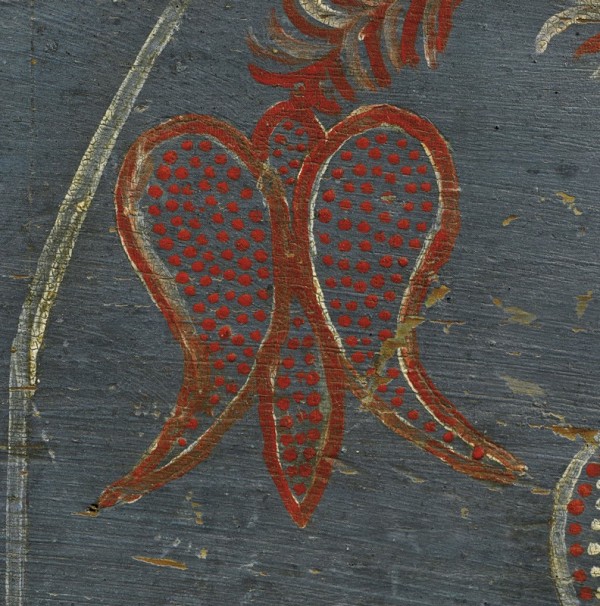

Detail of painted decoration that does not follow a scribed outline on the blue box illustrated in fig. 1b. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of coin edging on the box illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

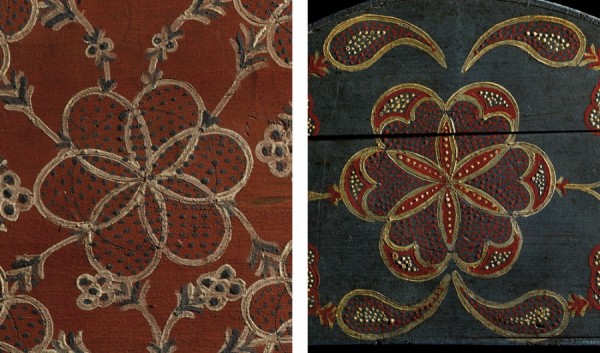

Comparison of two compass-work motifs, from the large red box illustrated in fig. 1c (left) and the box illustrated in fig. 41 (right). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

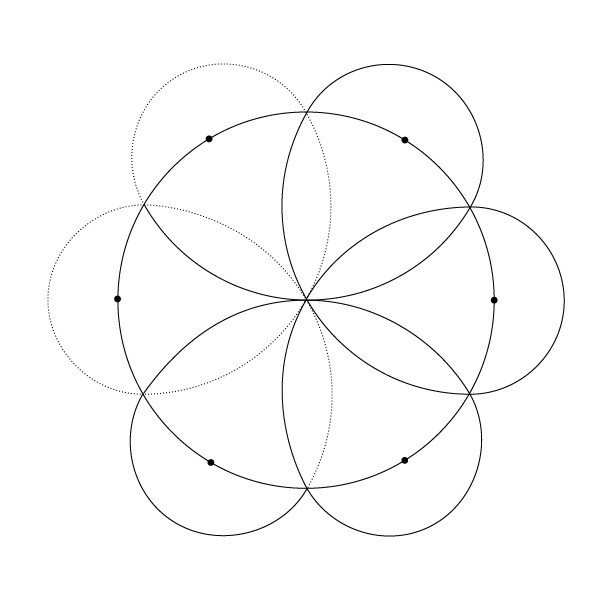

Line drawing showing the scribing of a compass motif.

Detail of fan motif on a box not illustrated in this article. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a half-tulip motif on the box illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a tulip motif on the chest illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar. H. 2 1/4", W. 5 3/4", D. 7 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar. H. 2 3/8", W. 8", D. 5 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The interior of this box is partitioned into six compartments.

Saltbox, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Pine. H. 12 1/4", W. 6 3/4", D. 6 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cradle, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar. H. 8", L. 16 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Pook & Pook.)

Chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1788. Pine, oak. H. 22 1/4", W. 48 7/8", D. 21 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1785–1820. Pine, oak. H. 23", W. 50", D. 22". (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. Donald M. Herr; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the underside of the chest illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a foot on the chest illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the wedged tenon of a foot on the chest illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the lock inscribed “GHEN 1802” on a chest with compass artist decoration not illustrated in this article. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the mermaids drawn in chalk on the inside of the lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 35. (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. Donald M. Herr; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar. H. 7 7/8", W. 10 3/4", D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

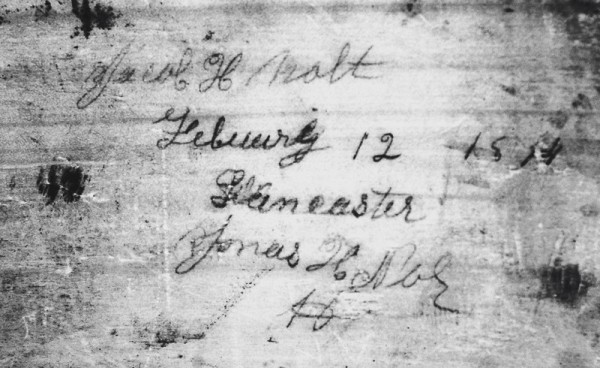

Infrared image of inscription “Jacob H Nolt / February 12, 18[ ]4 / Lancaster / Jonas H Nolt” on the box illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

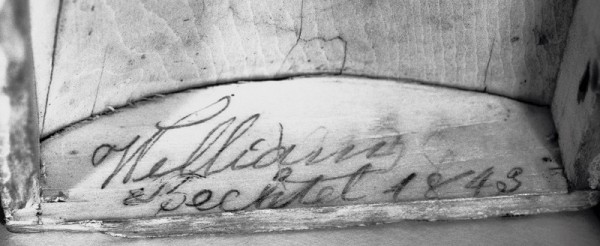

Infrared image of the inscription on the small red box illustrated in fig. 1a. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

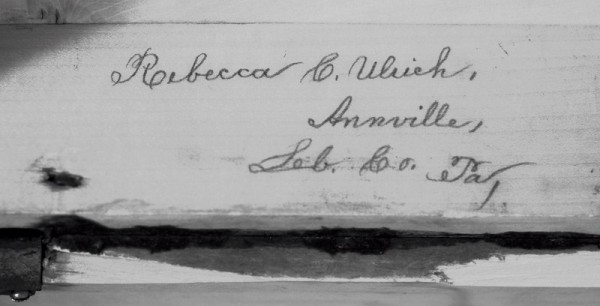

Infrared image of the inscription on a box not illustrated in this article. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Box, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1840. Tulip poplar. H. 2 1/2", W. 3 1/2", D. 6 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, gift of Larry M. Neff in memory of Frederick W. Weiser; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the underside of the box illustrated in fig. 45.

Map of southeastern Pennsylvania highlighting Lancaster and Lebanon counties with townships relating to owners of compass artist objects delineated.

Since the early twentieth century, collectors of folk art and painted furniture have pursued a large group of decorated boxes and related objects (fig. 1) associated with Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (fig. 2), and attributed to the so-called compass artist. Although dozens of these boxes are known, rare forms or examples in near-perfect condition have brought staggering prices at auction. Despite the sheer number of these objects and their popularity, many critical questions about them remain unanswered. Building on research conducted at the Winterthur Museum in 2007, this article explores the scope of the compass artist group and reveals how these objects were made and who owned them.[1]

To date more than sixty pieces of furniture have been documented as part of this group. The most common form is the dome-top box with hinged lid, of which more than thirty-five examples are known. A variation on this form is the large-scale box with one drawer across the bottom, of which three are known (fig. 3). Other forms identified include ten small slide-lid boxes, one hinged-lid saltbox, two doll cradles, and five full-size blanket chests (fig. 4). Several of these objects have inscriptions that help identify where their early, and in some instances original, owners lived.

Early Collecting

The bold and colorful decoration of compass artist objects appealed to an interesting mix of early-twentieth-century collectors. Artists of that era were among the first to collect American folk art, including Polish-American sculptor Elie Nadelman (1882–1946). The Nadelmans owned two dome-top compass artist boxes, which were exhibited in the American Corner of their Museum of Folk Arts on their estate in Riverdale, New York, until 1937, when their collection was sold to the New-York Historical Society (fig. 5). Other early collectors included Rhea Mansfield Knittle—an Ohio collector and one of the early proponents of Antiques—and Henry Francis du Pont, who used four compass artist boxes in the 1920s when furnishing his Chestertown House in Southampton, Long Island. Interior photographs of that residence show two dome-top boxes displayed on top of a painted chest in the entrance hall (fig. 6). Three of these dome-top boxes are now in Winterthur’s collection, along with four more dome-top boxes and a slide-lid box also acquired by du Pont. Unfortunately, Mr. du Pont’s daybooks—which record his purchases along with their source and price—do not provide enough descriptive detail to determine the dates of acquisition or the dealers who supplied these boxes. Other contemporaries of du Pont who collected compass artist pieces included Mrs. Robert de Forest (Emily Johnston), who in 1934 gave her collection of Pennsylvania German folk art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and York, Pennsylvania, native Titus C. Geesey (1893–1969), whose collection now resides in part at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[2]

Although these boxes were collected at an early date, little was known at the time about their origins or use. The Index of American Design—a WPA project that ran from 1935 to 1942 in which artists were hired to produce watercolor renderings of American decorative arts—included two dome-top boxes among more than eighteen thousand images. In it, a red dome-top box (fig. 7) was described as a “casket with domed lid . . . covered with wallpaper.” Why this box was described in such a manner remains unclear, but it is likely that the cataloguer mistook the precise, repetitive pattern design of its painted decoration for wallpaper. In 1948 John Joseph Stoudt referred to the same object as a “sea-chest such as the Pennsylvania Germans used in coming to Pennsylvania.” One wonders if he ever saw that box in person, as its diminutive size and fragile hardware would have precluded such use. The second box included in the index (fig. 8) was a small blue dome-top example, described as a “domed casket . . . vigorously painted.”[3]

Although the aforementioned objects have distinctive decoration, the use of a compass to generate designs was by no means unique to their period or culture. Compasses—often referred to as a “pair of compasses”—have been used in woodworking and drawing since Roman times. In 1525 Albrecht Dürer published a treatise addressed to “painters, goldsmiths, sculptors, stone masons and joiners and all ‘who use measures,’” in which he presented precise instructions with accompanying drawings to demonstrate the use of compasses and a ruler. Closely related to compasses are dividers, which have a setscrew at the juncture of the legs for more precise control. In Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises, first published in 1678, a pair of compasses is illustrated among “Joyner’s Tools” (fig. 9), which he described by noting: “Of the Compasses . . . Their Office is to describe Circles, and set off Distances from their Rule, or any other Measure, to their Work.” Under his instructions for creating sundials, Moxon wrote, “You may in small Quadrants divide truer and with less trouble with Steel Dividers (which open or close with a Screw for that purpose,) than you can with Compasses.”[4] Advertisements from the nineteenth century document the availability of these tools in both fancy good and general stores. In 1819 Allen Armstrong of Philadelphia advertised a list of “hardware goods” to “country merchants,” including compasses, dividers, rulers, saws, hinges, and many other items. An early-nineteenth-century tool catalogue published by the firm of Richard Timmins and Sons offered a wide selection of compasses and included a pair in each of their “Gentlemen’s Tool Chests.”[5]

Before its use in America, compass-work decoration was common in carved and painted decorative arts from northern Europe. Painted chests of Germanic origin were sometimes profusely embellished with compass-work decoration (fig. 10). During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, furniture makers on both sides of the Atlantic used compasses to lay out carved designs on a wide range of forms, including cupboards, chests, boxes, and spoon racks (fig. 11). Designs for inlaid ornament were generated in much the same way, as indicated by the line-and-berry motifs associated with furniture from Chester County, Pennsylvania (fig. 12).[6]

The Dome-Top Boxes

The most numerous form in the compass artist group is the dome-top box, of which nearly three dozen examples are known. Although no two are exactly the same size, these boxes are remarkably consistent in their materials and construction. Almost all are made of Liriodendron tulipifera, also known as tulip poplar or tulipwood and often referred to as poplar in period documents. The boards used for the front, sides, back, and bottom are typically between 3/8-inch and 7/16-inch thick, whereas the stock used for the domed top is usually about 5/32-inch thick.[7]

The dome-top boxes range in size from 3 3/4 by 3 7/8 by 2 7/8 inches to 13 13/16 by 17 11/16 by 11 3/8 inches. Their components were not laid out with patterns, nor do the boxes adhere to a standardized system of proportions. This suggests that the boxes were made individually and likely over many years. The construction of the boxes involved several steps. First, the maker cut his stock, which included front, back, and bottom boards that were rectangular in shape, side boards that were arched at the top, and a lid that was rectangular but much thinner than any of the other components. After sawing and chopping the dovetail joints, he assembled the front, side, and rear boards to form the basic box (fig. 13). The next step involved attaching the bottom board. On all of the boxes the bottom is secured with small, square wooden pins, with more fasteners across the grain than with the grain to help prevent shrinkage (fig. 14). The bottom board prevented the sides from racking and allowed the maker to attach the top, which he accomplished by bending a thin board over the arched sides and securing it with wooden pins (fig. 15). The maker probably scribed the outlines for the decoration on the lid before attaching it, since it would have been easier to work on a flat surface than a curved one. After laying out the remaining motifs, which typically included compass-work and template-generated designs (fig. 16), he sawed the box in two (fig. 17). The latter procedure is verified by the bisected dovetails at each corner, where the lid and lower case meet (fig. 18). By constructing the box as a closed object and then sawing it in two, the maker was able to obtain near-perfect alignment of the lid, case, and scribed designs at the juncture of those sections. On some larger boxes, he tacked a thin strip of wood along the upper inside edge of the front board or attached vertical posts in the front corners (fig. 19) to align the lid and body.[8]

After completing the woodwork, the maker attached the hardware, which consisted of a hasp, escutcheon plate, and hinges. This step occurred after the lid and body were separated, but before any paint was applied. Several boxes with missing or replaced escutcheons have no trace of paint under those components (fig. 20), while others retaining their hardware have paint remnants on top of the plate and hasp (see fig. 22). In addition, paint drips frequently can be seen inside these boxes along the seam where the lid and lower case join, indicating that those objects were in two pieces when painted (fig. 21).

The boxes’ hardware is also remarkably consistent in design and manufacture, indicating that the metalwork and woodwork were probably done in the same shop. Each lid is secured to the bottom section with a pair of distinctively constructed hinges at the interior of the back. The hinges are composed of two parts: a thin wire and a thin strip of tinned sheet iron. The wire is horizontally positioned between the top and bottom of the box, and the strip of tinned sheet iron is folded over the wire. While the ends of the wire pierce the back of the lid and are spread open and crimped, the folded strip of tinned sheet iron extends through a diagonal slit near the top edge of the backboard and is secured on the inside with one or two small forged nails (see fig. 21).[9]

The hasp and escutcheon plate are also fashioned from tinned sheet iron. The escutcheon plate is usually cut in a fan shape and decorated around the perimeter with a border of punched dots. A U-shaped wire inserted vertically through the center of the plate and into the front of the box is crimped on the inside. This forms a loop over which the hasp is dropped and through which a small padlock can be placed to secure the contents of the box. The escutcheon plate is held on by this loop of wire, sometimes reinforced later with small nails or screws. The hasp, which overlaps the plate, is usually trapezoidal in shape, with a central vertical slit to allow it to go over the U-shaped wire (fig. 22). The maker attached the hasp to the front face of the lid by rolling the top edge around a wire that is pierced through the lid and crimped in a manner similar to that of the wire securing each hinge. The bottom edge of the hasp is also typically rolled but the sides are left as unfinished edges. Like the escutcheon plate, the hasp has punchwork around the slit opening and the perimeter. Often there is additional punching above the slit in the shape of a cross or star. Due to their fragile nature, many of the hasps are missing or broken. No original locks are known to have survived with any of the dome-top boxes.

Painting the Boxes

Once the box was joined, scribed, cut in two, and fitted with hardware, it was ready to be painted. First, the decorator applied a ground coat of either red or blue. Only the undersides and interiors were left unpainted. The pigments were suspended in a binder composed predominantly of a drying oil such as linseed oil. The majority of known dome-top boxes have a blue ground color that has been identified by infrared spectroscopy as Prussian blue. First developed in the early eighteenth century in Germany, this pigment was used for artists’ colors and cost a fraction of the price of ultramarine, making it more accessible to those with limited means or in less populated areas. In 1816 James Smith described Prussian blue in the Panorama of Science and Art as “bright, deep, and cool” and recommended that for ease of application and appearance it should be used soon after being ground. Over the years, as many of the boxes accumulated coats of now-yellowed varnish, shellac, or grime, the bright Prussian blue often appears as various shades of greenish blue or even a blackish color. Although Prussian blue was by far the most common ground color, a small number of boxes have a red ground, identified as a combination of vermilion and red lead. Vermilion was also used for the red decoration on top of the blue ground color in several boxes that were tested. This pigment has been in use since the early medieval period, and, according to Smith, it was the preferred pigment for red, being a “bright scarlet . . . that stands tolerably well if perfectly pure.” The common alternative, red lead, was cheaper but also more problematic as it was “very liable to turn black.” In addition to the red and blue colors, a third pigment on the boxes was white lead suspended in linseed oil, which was used to paint over the scribed compass-work outlines and apply decorative details. Thus far, no boxes have been documented with a white ground.[10]

Prussian blue, vermilion, red lead, and white lead were all in use during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These pigments and other materials needed for painting were available at drugstores such as that of Dr. J. M. Sherer in Lancaster. Though none of these pigments helps narrow the date range of the boxes’ manufacture, signs of age can be detected in their composition and help authenticate the boxes.[11]

After applying the primer and ground coat, the decorator outlined the scribed compass motifs in white lead paint, then filled them in with stippled dots to contrast with the ground color. The scribed outlines would have shown sufficiently through the ground paint to allow the decorator to paint over them. Usually the outlines were followed very carefully, though occasionally the decorator made a mistake or chose to ignore the outline altogether (fig. 23). After these compass-work outlines were painted, additional freehand decoration was applied to fill in the space around the scribed motifs, sometimes profusely. These designs, which consist mainly of leafy vines and floral sprigs, were painted in white with accents of contrasting red or blue.

All the paint except the ground coat appears to have been applied with a small brush. Depending on the consistency of the paint, this occasionally resulted in a coin edge, wherein the paint in a given line appears thinner in the center and thicker at the edges (fig. 24). The shape of the dots, which range from round to elliptical, also varied depending on how quickly or carefully the decorator applied the paint, the angle of his brush, or how much paint the bristles held. Because the application of paint differs slightly from box to box, it is difficult to determine whether one or more persons decorated them. Sometimes the paint appears very thick, other times it is smooth and thin; sometimes the dots are randomly applied, other times they are precisely arranged in neat rows (fig. 25). Even if only one person was making and painting the boxes—as their construction and decoration suggest—variations in weather conditions, paint mixtures, and so on make it likely that some differences would occur over the time in which they were produced. Although no two boxes are painted identically, their tops and sides usually have a large, central compass motif and their fronts have two or more. The complexity of these scribed designs varies from box to box, as does the density of the freehand painted decoration. This gives each object a slightly different visual effect.

Decorative Motifs

The primary motif on the boxes is a compass-work design, which was created by scribing a circle, then dividing it into six equal parts. The process was simple and required no measuring, as each line builds on another until the design is complete (fig. 26). Occasionally, the decorator added extra semicircles around the design, but the basic shape remained the same. Another common motif is a simple multipetal flower, which was created by scribing a small circle, then adding petals concentrically. Some of the boxes have a lobed half-circle or fan motif, which was usually placed at the bottom edge of the front or lid of the box (fig. 27). The fan motif is used on other objects in the compass artist group, including several chests also decorated with tulips and other floral designs (see figs. 34, 35). Another motif that is scribed on many of the boxes was probably done with a stencil or template and is shaped like one petal of a tulip (fig. 28). This design was also used in pairs on several of the full-size chests to create a tulip on the front panels (fig. 29).[12]

Boxes with Drawers

Three large dome-top boxes have a shallow drawer across the bottom of the front (see fig. 3). These drawers are dovetailed and have pegged bottoms. On the interior, the bottom of the box’s upper compartment rests unattached on supports that run front to back at either side and serve a dual function as guides for the drawer. These boxes also feature a small built-in key lock on the drawer with a punched tinned sheet iron escutcheon.

Slide-Lid Boxes

Of the ten slide-lid boxes documented to date, nine have blue grounds and one has a red ground (fig. 30). At least two are divided into six smaller compartments on the interior (fig. 31). These boxes vary slightly in size but are similarly constructed. Their sides are dovetailed together at the corners, and their bottoms are secured with small wooden pins. As with the dome-top boxes, there are more pins across the grain than along the grain of the wood, assuring that the bottom will not split as the wood shrinks. Before assembling the box, the maker cut a groove at the top of the sides and back to receive the sliding lid. The lids are made of a thin piece of wood with a strip added at the front to facilitate opening and closing. This strip is angled at either side to fit into a corresponding angled cut on the sides of the box.

Other Small Forms

The shop responsible for the above-mentioned boxes produced at least two other small forms. The hanging saltbox illustrated in figure 32 is the only example known. Although it has a replaced lid, holes in the sides indicate that the original lid rotated on pintles. The sides of the box are rabbeted and pinned through the front and back. Before attaching the back, the maker slid the bottom into grooves in the sides and front.[13]

Two doll-size cradles from this shop have been identified (fig. 33). Both have small dovetail joints securing the sides to the head- and footboards, and bottoms and rockers are attached with small forged nails. Large compass stars are painted on the ends and sides, with a fan motif at the center of each side. Although the design of the saltbox and cradles makes comparison of their construction with that of the dome-top boxes difficult, the decoration of these objects is so closely related to that of the red-ground dome-top boxes that it would be hard to believe that they are by a different painter.

Chests

Five full-size chests with compass artist decoration are known. The details of the painted decoration on these objects vary, but each consists of two or three large arched panels on the façade. Despite the difference in scale, the decoration on these panels is strikingly similar to that on the related boxes (figs. 34, 35). The decoration on the lids of these chests is mostly worn away, but some have faint outlines of rectangular panels. The motifs used on the chests include compass-work motifs and fans as well as template-generated tulips. All the chests have turned ball feet and battens at each end. The tenons of the feet extend through the battens and bottom board and are wedged at the top (figs. 36, 38). The chests have filleted-ogee base moldings that are set flush with the battens at each end and attached with large wooden pins (fig. 37). One of the chests bears the date “1788” and initials “ch” on its façade, but it is unclear whether that date denotes the year of manufacture or is commemorative (see fig. 34). The lock on another chest is decorated with wriggle-work and inscribed “ghen 1802” (fig. 39). Unlike the shop-made hardware of the dome-top boxes, the forged iron hinges, crab locks, and keys associated with the chests were probably purchased from a blacksmith. Flanking the hinges on the chest in figure 35 is a whimsical pair of mermaids drawn in chalk (fig. 40). Unlike the boxes with compass artist decoration, which appear to have been made and painted in the same shop, the chests may represent the work of a local cabinetmaker or carpenter who then commissioned the painted decoration from a different craftsman. Two chests are also known that are constructed like the five examples with compass artist decoration but clearly painted by a different hand.[14]

Use

The original use of the boxes with domed tops and sliding lids, which come in a wide variety of sizes, is difficult to ascertain. No inscriptions or period contents identify their intended function, though owners’ names inscribed on some of the boxes include those of both men and women, suggesting that these were not gender-specific objects. Most of the boxes are very clean on the inside, few having stains from ink, paint, or other materials. Several of the slide-lid boxes are divided into compartments, suggesting that small articles such as buttons, coins, or sewing supplies may have been stored inside. The dome-top boxes were all built with hardware that enabled them to be padlocked. Although they could have been used for safekeeping private or valuable objects, the thin stock and delicate hinges of the boxes would not have made them secure. Most likely, the boxes were used to store all manner of objects and not made for any specific purpose.

Provenance

Among the more than fifty objects ascribed to the compass artist group, several dome-top and slide-lid boxes bear pencil or ink inscriptions revealing the names of early—though possibly not original—owners. These inscriptions appear in various hands and are located in different places, typically on the underside or underneath the lid. Although the frequent occurrence of certain names in the Lancaster region makes it difficult to link some inscriptions with specific individuals, several people can be identified as probable owners of these objects.

Of the eight compass artist boxes in the Winterthur collection, three have inscriptions. A dome-top example published in Clarke Hess’s Mennonite Arts has a partially abraded inscription on the underside that was interpreted as “Jonas Nolt” and the date “1814” (fig. 41). More recently, infrared photography revealed two names and a date that is only partially legible: “Jacob H Nolt / February 12, 18[ ]4 / Lancaster / Jonas H Nolt” (fig. 42). During the 1800s a large number of Nolts lived in West Earl Township, Lancaster County, and were members of the Mennonite faith. By the mid-1800s Mennonite children commonly received their mother’s maiden name as their middle names. Based on that practice, candidates for the names on the box are Jonas (1838–1909) and Jacob (1826–1827) Nolt, whose parents were Jacob (1798–1852) and Barbara (Hurst) (1806–1881). Jacob’s death at the age of only one year raises the question why his name would have been inscribed on the box, but research to date has uncovered only these names that fit the inscription.[15]

The small red dome-top box illustrated in figure 1 bears the pencil inscription “William / Bechtel 1843” on the interior of the lid (fig. 43). Although this William Bechtel has not been positively identified, the Bechtel name appears in Lancaster County records. The 1850 census lists a William Bechtel, aged twenty, as a laborer in Ephrata Township. Ten years earlier, a William Bechtel took communion at the Swamp Reformed Church of West Cocalico Township, Lancaster County.[16]

A third dome-top box in Winterthur’s collection has the pencil inscription “Rebecca C. Ulrich, / Annville, / Leb. Co. Pa.” under the lid with the word “institute” next to it written in red (fig. 44). The geographic reference dates the box to at least 1813, when Lebanon County was formed from parts of Lancaster and Dauphin counties. Census records from 1840 and 1850 list a Rebecca C. Ulrich (1849–1907) living with her parents, Adam and Rebecca (b. 1809), in North Annville, Lebanon County. Rebecca C. Ulrich presumably wrote the inscription, but it is possible that the box belonged first to one of her parents. The word “institute” may refer to the Annville Academy founded by Rebecca’s grandfather Adam Ulrich in 1834 and later run by her uncle William Stewart before being acquired by Lebanon Valley College. In 1880 Rebecca “Beckie C.” Ulrich was unmarried and living with her mother and sister.[17]

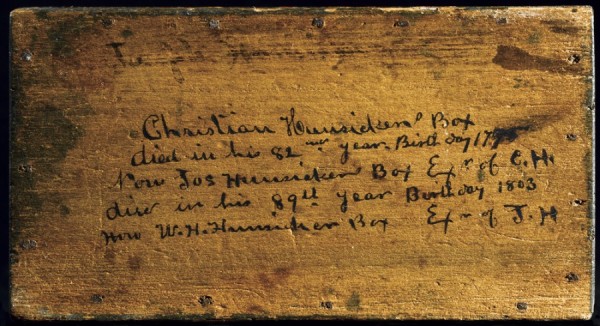

The underside of the slide-lid box shown in figures 45 and 46 is inscribed “Christian Hunsicker’s Box / died in his 82nd year, Birthday 177[ ] / Now Jos Hunsicker Box Exr of C. H. / died in his 89th year Birthday 1803 / Now W. H. Hunsicker Box Exr of J. H.” Christian Hunsicker was born on March 26, 1776, and died on August 5, 1857. He was buried in the graveyard of Wolf’s Union Church (the term “Union” referring to a shared Lutheran and Reformed Church), Bethel Township, Lebanon County. His son Joseph was born in 1803 and died in 1892. William H. Hunsicker was born about 1842 and died between 1920 and 1930. According to the 1850 census for Bethel Township, Lebanon County, Joseph Hunsicker was a forty-nine-year-old farmer whose household contained his seventy-four-year-old father, Christian, and eight-year-old son, William. By the time the 1880 census was taken, Joseph was living with William and his wife in Bethel Township. William still lived there in 1920, but there is no reference to him in the 1930 census. He is likely the same William H. Hunsicker who served on the building committee of the Union Meetinghouse in Bethel Township in 1913. The religious groups who used the original meetinghouse included German Baptists (also known as Dunkers or Dunkards), so it is possible that the Hunsickers were members of that faith. Unfortunately, the probate inventories of the Hunsicker men do not list small items in detail. One possibility raised by the association of Christian Hunsicker with the compass artist group is that the chest initialed “ch” and dated 1788 might be connected with him (see fig. 34). In 1788 Christian would have been twelve years old and, like many Pennsylvania German children and teenagers, would probably have been given a chest for the storage of his personal belongings.[18]

During the course of this study, the authors documented several other boxes with inscriptions. A blue dome-top example inscribed “Grate Aunt / Aunt Sallie[?] Millers” sold at auction in 2008 (see fig. 1). The red slide-lid box (see fig. 30) contained numerous pencil inscriptions, including “Kate H. Brubaker 1866” and “Jacob H. Brubaker.” Miller and Brubaker are such common names in Lancaster County that it may be impossible to link specific individuals with this object. Another dome-top box bears the ink inscription “Susanna Knabb, 1800.” The Knabb surname occurs in Lancaster County records, but no woman named Susanna has been located. The decoration on the latter box also differs slightly from others in the group in having compass designs filled in with tulips rather than dots.[19]

The families associated with objects from the compass artist group were Pennsylvania Germans who practiced a variety of Protestant faiths: Mennonite, Dunkard, Lutheran, and German Reformed. Some inscriptions, particularly that on the Hunsicker box, imply that these objects were heirlooms passed from generation to generation. The names of both men and women on the boxes suggest that the forms were not gender-specific. Indeed, proximity seems to be the primary link among owners. The various families associated with the boxes lived near the border separating Lancaster and Lebanon counties (fig. 47). A large part of this region is known as the Cocalico Valley, which includes the townships West Cocalico, East Cocalico, Ephrata, Clay, West Earl, and a portion of Earl.

Maker or Makers

Similarities in the construction of the boxes and other small forms in the compass artist group suggest that they were made in the same shop if not by the same hand. This craftsman or small workforce was also likely responsible for the painted decoration. Evidence supporting this conclusion can be found in the scribed designs on the tops of the dome-top boxes, which were apparently incised on the lid boards before being attached. The simple and consistent hardware, which was attached before painting, is a further indication that these objects were built, furnished, and decorated in one shop.

The picture becomes less clear with the full-size chests. The chests are constructed identically, but their decoration varies more than that of the boxes. Moreover, none of the boxes has template-drawn tulip motifs like those on the chests.

Even if the objects of the compass artist group are not the product of a single shop or individual, they nevertheless represent an extremely cohesive and geographically restricted decorative tradition. Assuming that its date is not commemorative, the chest marked “1788 / CH” is the earliest known object in the group (see fig. 34). Like the related examples, it does not appear to have been constructed by the maker of the boxes. Several chests also have large tulips on their façades, a motif not found in related scale or context on other forms in the compass artist group. Similarly, some of the chests and dome-top boxes have compass motifs whose segments are filled with alternating colors—usually red or white—rather than being outlined in white, and contain a tiny hand-painted stemmed flower. Another visually distinctive subgroup includes the dome-top boxes, saltbox, and two cradles with red grounds. Variations such as these could reflect the work of allied hands or be the products of one craftsman whose style changed over time.[20]

Although the identity of the compass artist remains elusive, documentation and analysis of the objects have yielded information about their construction, decoration, and ownership and provided insight into material life in rural Pennsylvania German communities. Efforts are ongoing to locate and document additional examples, particularly those with inscriptions or family histories. The sheer quantity of extant objects from the compass artist group—probably only a fraction of the original number—suggests that they were in great demand as decorative storage objects when they were made and speaks to their continued appeal as family heirlooms and treasured antiques down to the present day.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Mark Anderson, Gavin Ashworth, David Barquist, Jeanette and Chet Bartoli, Luke Beckerdite, Patrick Bell, Laszlo Bodo, Robert and Kathy Booth, Derin Bray, Ruth and Jack Bryson, Skip and Scott Chalfant, Joyce Collis, Peter Deen, William K. du Pont, Ellen Endslow, Ritchie Garrison, Jim and Nancy Glazer, Vernon Gunnion, Don and Trish Herr, Clarke Hess, Ed Hild, Margi Hofer, Stacy Hollander, Carroll and Claudia Hopf, Charles Hummel, Joan and Victor Johnson, Alan Keyser, Alexandra Kirtley, Greg Kramer, Dr. Jennifer Mass and the Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory at Winterthur, Catherine Matsen, Mary McGinn, Dana Melchar, Kendl Monn, Cynthia Nadelman, Pastor Larry Neff, Susan Newton, Karl Pass, Ron and James Pook, Todd Prickett, Andrew Richmond, Charlie Ritchie, Jim Schneck, Joane Smith, Steve and Dolores Smith, Walter and Jeanette Smith, Penny Stillinger, the late Pastor Frederick S. Weiser, and David Wheatcroft.

A large domed-top box with a drawer sold for $374,400 at Pook & Pook, The Collection of Dr. Donald and Esther Shelley, Downingtown, Pa., April 20–21, 2007, lot 210. In the fall of 2007 Patricia Edmonson undertook a study of the compass artist group, under the direction of Wendy A. Cooper and Lisa M. Minardi, for a connoisseurship class in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture. Edmonson’s study formed the basis for this article.

Elizabeth Stillinger, “Elie and Viola Nadelman’s Unprecedented Museum of Folk Arts,” Antiques 146, no. 4 (October 1994): 516–25. Joshua Ruff and William Ayres, “H. F. du Pont’s Chestertown House, Southampton, New York,” Antiques 160, no. 1 (July 2001): 98–107. The whereabouts of the fourth box are unknown.

Virginia Tuttle Clayton, Elizabeth Stillinger, Erika Davis, and Deborah Chotner, Drawing on America’s Past: Folk Art, Modernism, and the Index of American Design (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2002). Clarence P. Hornung, Treasury of American Design, 2 vols. (1950; reprint, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1972), 2: 713. John Joseph Stoudt, Pennsylvania Folk Art: An Interpretation (Allentown, Pa.: Schlechter’s, 1948), p. 272. Hornung, Treasury of American Design, 2: 715.

Joseph Moxon, Mechanick Exercises: or the Doctrine of Handy-Works, Applied to the Arts of Smithing, Joinery, Carpentry, Turning, and Bricklaying, 3rd ed. (London: Dan. Midwinter and Ths. Leigh, 1703), pp. 63, 104, 316, and pl. 5.

R. A. Salaman, Dictionary of Woodworking Tools (Newtown, Conn.: Taunton Press, 1990), p. 152. Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, March 25, 1819. Philip Walker, The Victorian Catalogue of Tools for Trades and Crafts (London: Studio Editions, 1994), pp. 4, 15–16.

Reinhard Peesch, The Ornament in European Folk Art (New York: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, 1982). Siegfried Seidl, Niederbayrische Bauernmöbel zwischen Isar und Inn, im Rott- und Vilstal (Munich: Callwey Verlag, 1979), pp. 105, 107, 134.

The wood in three of the eight boxes owned by Winterthur was microscopically analyzed, and others were determined by visual inspection.

Before being attached to the box, the lid may have been bent slightly by wetting one side and forming it on a jig. Steaming would not have been necessary owing to the thinness of the boards. In at least some cases, boxes may have been glued at the corners and sides. This sawing the box in two was confirmed by examination under magnification, in which it was easily seen that the scribe lines continue seamlessly across the break between lid and body, indicating that the sides were scribed before being cut.

This type of hinge is occasionally seen on other types of small wooden boxes, including several examples in the group of predominantly flat-topped, rectilinear boxes collectively dubbed “Bucher” boxes that are typically associated with Lancaster County.

Cross-sectional paint analysis on two of Winterthur’s boxes (1965.1980 and 1967.0926) revealed the presence of a gum primer. Dana Melchar, “Investigation of Pennsylvania German Dome-Lid Painted Boxes,” Spring 2005, Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, p. 13. R. D. Harley, Artists’ Pigments, c. 1600–1835 (London: Butterworth Scientific, 1982), pp. 72–73. James Edward Smith, Panorama of Science and Art: Embracing the Sciences of Aerostation, Agriculture and Gardening, Architecture, Astronomy, Chemistry, Electricity, Galvanism, Hydrostatics and Hydraulics, Magnetism, Mechanics, Optics, and Pneumatics (Liverpool: Nuttal, Fisher, and Dixon, 1816), p. 732. Melchar, “Investigation of Pennsylvania German Dome-Lid Painted Boxes,” p. 18. Analytical Report, Winterthur Museum, Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory, December 4, 2008. Three pigment areas on Winterthur’s small red-ground box (1967.804) and large red-ground box (1966.543) were studied with x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy, which determined the use of both red lead and vermilion. Smith, Panorama of Science, p. 731. Melchar, “Investigation of Pennsylvania German Dome-Lid Painted Boxes,” p. 18. A yellow-ground box is rumored to exist. It is possible that this was originally a white ground that now appears yellow owing to darkened varnish.

Lancaster Journal, February 13, 1829, p. 4. The presence of metal carboxylates in the paints, which are formed by the chemical reaction of the pigments and binding media as they break down over time, provide one indication of age.

Freehand tulips also appear on a small blue-ground dome-top box. See Pook & Pook, The Americana Collection of Richard and Rosemarie Machmer, Downingtown, Pa., October 24–25, 2008, lot 623.

A saltbox made for Anne Leterman by Bucks County craftsman John Drissell features similar construction (Winterthur 1958.17.1). That example is dated 1797.

The meaning of the letters “GHEN” is unclear. This chest sold at Conestoga Auction Company, Fall Americana and Furniture Auction, Manheim, Pa., September 29–30, 2006, lot 550. One chest was sold at Christie’s, Important American Furniture and Folk Art, New York, January 23, 2009, lot 174. It bears the inscriptions “Isaac Hain 1800” and “Anna Hain” on the underside of the lid. Hain is a surname found in Lancaster County. Another chest with related construction and decoration sold at Garth’s Auctions, Americana, Delaware, Ohio, March 28, 2009, lot 545.

Clarke Hess, Mennonite Arts (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 2002), p. 42. Hess cited Jonas Nolt (1801–1865) of West Earl Township as a likely owner of this box. That is unlikely since Nolt’s middle initial would probably have been “B” because his mother’s maiden name was Buckwater. Alan Keyser to Lisa Minardi, November 26, 2007. The 1850 census lists Jacob Nolt, aged fifty-two, as a farmer living in West Earl Township, Lancaster County, together with his wife, Barbara, aged forty-three. Their children included Jonas Nolt, aged twelve. U.S. Census records, West Earl Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1850. Also see Ancestry Library Edition, World Tree Project: DLW Database, Nolt Family Tree by Daniel Wenger, http://awt.ancestrylibrary.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=dlw-wc&id=I13519&ti=5542.

William J. Hinke, “Church Record of the Swamp Reformed Church or Little Cocalico in West Cocalico Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania,” typescript, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Thomas S. Stein, “Annville’s Oldest Burial-Place and Its Memories,” Proceedings of the Lebanon County Historical Society 6, no. 15 (November 5, 1915). U.S. Census records, North Annville Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1850–1880.

U.S. Census records, Bethel Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1880, 1910, 1920. The Committee Appointed by the District Conference, The History of the Church of the Brethren of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (Lancaster, Pa.: New Era Printing Company, 1915), pp. 450–54. Probate records, Lebanon County Courthouse.

Pook & Pook, Illustrated Auction, Downingtown, Pa., January 11, 2008, lot 141. When this box was first published, the name—which is written in German script—was erroneously transcribed as “Susanna Shrulb” (Stacy C. Hollander, American Radiance: The Ralph Esmerian Gift to the American Folk Art Museum [New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001], p. 459). Other boxes bearing inscriptions that have not yet been deciphered or located include a small dome-top example in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1934.100.44); a dome-top example sold by Cordier Antiques and Fine Art, Fall Antiques and Fine Art Auction, Camp Hill, Pa., November 11, 2007, lot 685; and a slide-lid box from the collection of Harold L. Murray Jr. of West Chester, Pa., that bore a partially legible pencil inscription transcribed as “S. S. Sholer / Reamsport town” (Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Museum).

See, for example, Hollander, American Radiance, fig. 137.