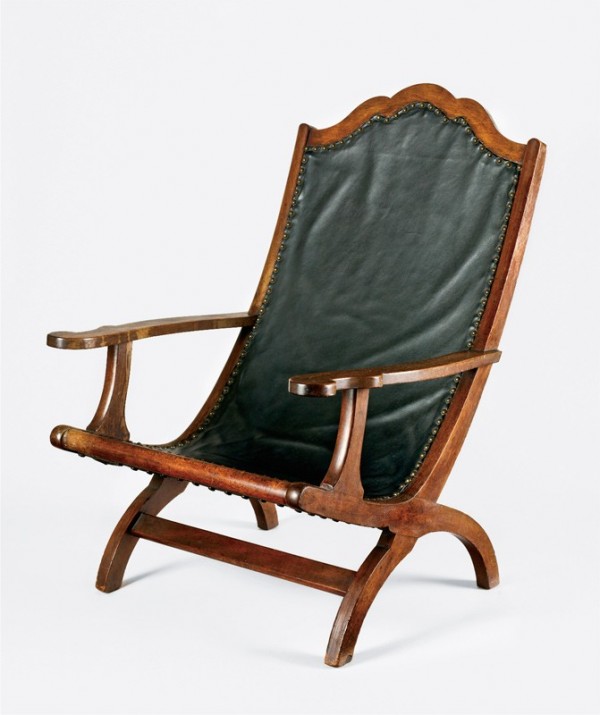

Campeche chair, probably New Orleans, Louisiana, ca. 1803–1810. Cherry, mahogany, and light wood inlay. H. 42 1/2", W. 28 1/4", D. 33". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Silver denarius of P. Cornelius P.f.L.n. Lentulus, Rome mint, ca. 74 b.c. Diam. (9/16". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, 2001.87.182. Numismatic Collection Transfer; photo, Alex Contreras.)

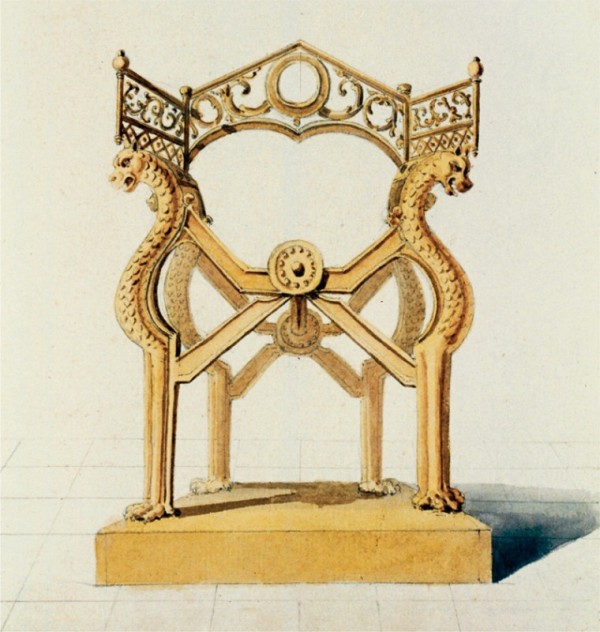

Trône de Dagobert à St Denis, France, 1750–1791. Ink and watercolor on paper. 7 3/4" x 6 7/8". (Courtesy, Bibliothèque nationale de France.) This depiction of Dagobert’s Throne was done when the object was still installed at St.-Denis, where Jefferson likely saw it in 1785. The actual throne is bronze with gilding and measures H. 53", W. 30 3/4". The cross-legged base with panther heads and monopod feet is the earliest feature of the chair, dating from the Merovingian period. The base has been reoriented, with the cross union now displayed in front. The back and armrests are later additions, likely from the Carolingian period.

Folding chair (sillon de cadera), Granada, Spain, ca. 1500. Walnut, ivory, bone, mother-of-pearl, tin. H. 36 1/2" , W. 24", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1945; photo, Art Resource, NY.)

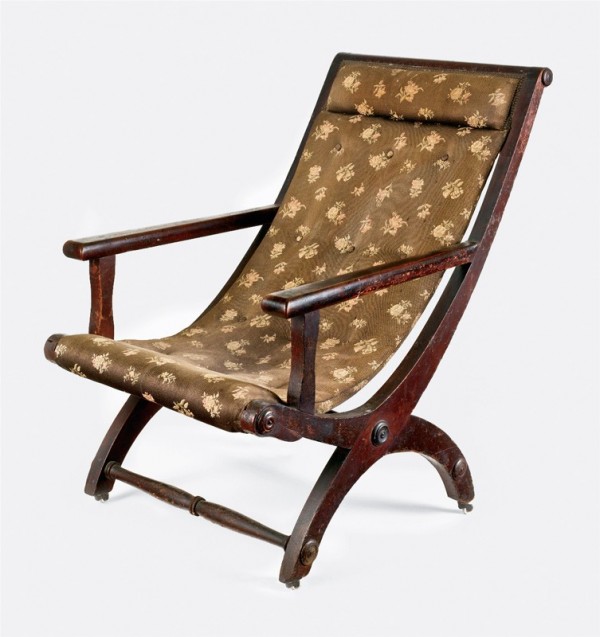

Campeche chair, probably New Orleans, Louisiana, 1810–1825. Mahogany with white oak and satinwood. H. 37", W. 26 3/4", D. 27 1/2". (Courtesy, Louisiana State University Museum of Art, gift of D. Benjamin Kleinpeter; photo, David Humphreys.) New Orleans Campeche chairs are often made of mahogany, but some are constructed of local woods, particularly walnut.

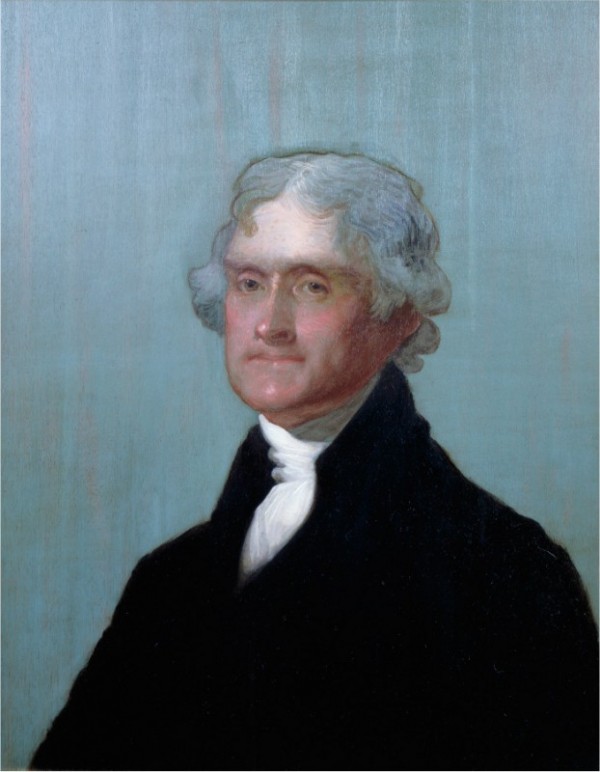

Thomas Sully, Thomas Jefferson, 1856. Oil on canvas. 34 1/2" x 27 1/2". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Edward Owen.) Sully made this copy after his earlier full-length life portrait of Jefferson done for the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1821.

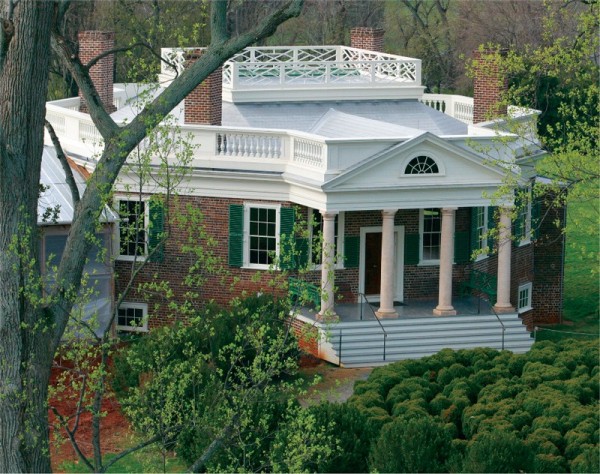

Monticello, Charlottesville, Virginia. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Peter Hatch.) Jefferson may have sat in one of his Campeche chairs under this portico.

Poplar Forest, Lynchburg, Virginia. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest; photo, Les Schofer.) Campeche chairs made up part of the furnishing plan at Jefferson’s retreat Poplar Forest.

Parlor, Monticello, Charlottesville, Virginia. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Edward Owen.) Jefferson used two Campeche chairs in the parlor, one on either side of the door to the portico. One chair was next to a bust of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Gilbert Stuart, Thomas Jefferson, 1805. Oil on wood. 26 1/4" x 21 3/4". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, and Thomas Jefferson Foundation; photo, H. Andrew Johnson.)

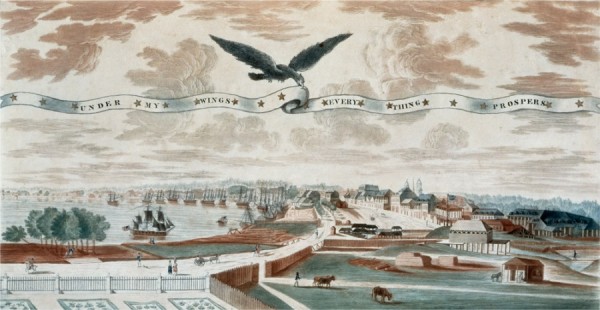

John L. Boqueta de Woiseri, A View of New Orleans Taken from the Plantation of Marigny, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1804. Aquatint on paper. 11 5/8" x 21 7/16". (Courtesy, The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1958.42. Museum/Research Center.)

“The President’s House,” title page engraving. Chas. W. Janson, Stranger in America (London: J. Cundee, 1807). (Courtesy, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.) This illustration shows how the house looked during Jefferson’s term.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, View from the Window of My Chamber at Tremoulet’s Hotel, New Orleans, 1819. Pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper. 9" x 11 7/16". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.)

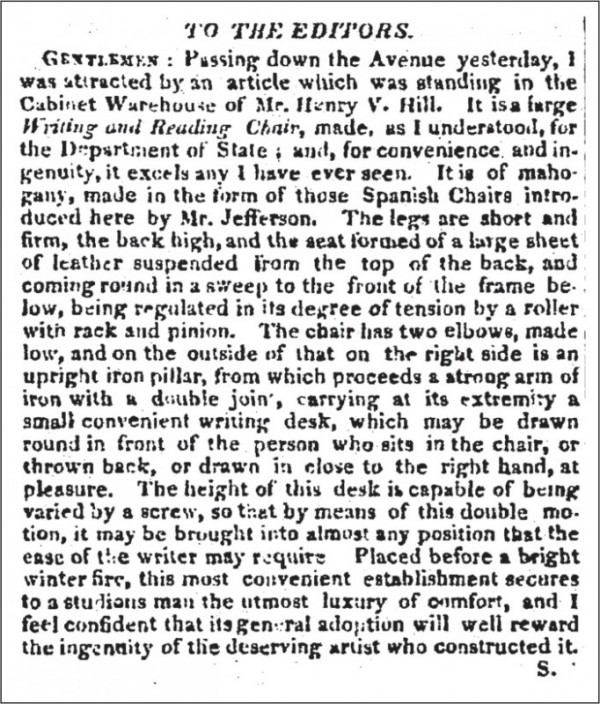

Editorial, Daily National Intelligencer, July 28, 1827. From 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. (Courtesy, Gale/Cengage Learning.)

Campeche chair, probably New Orleans, Louisiana, 1815–1825. Mahogany and mahogany veneer. H. 41", W. 23 1/2", D. 41". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Campeche chair, probably New Orleans, Louisiana, 1815–1820. Mahogany. H. 39 7/16", W. 24", D. 33". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Campeche chair, probably Albemarle County, Virginia, 1815–1830. Cherry. H. 41", W. 23 1/2", D. 51 1/2". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

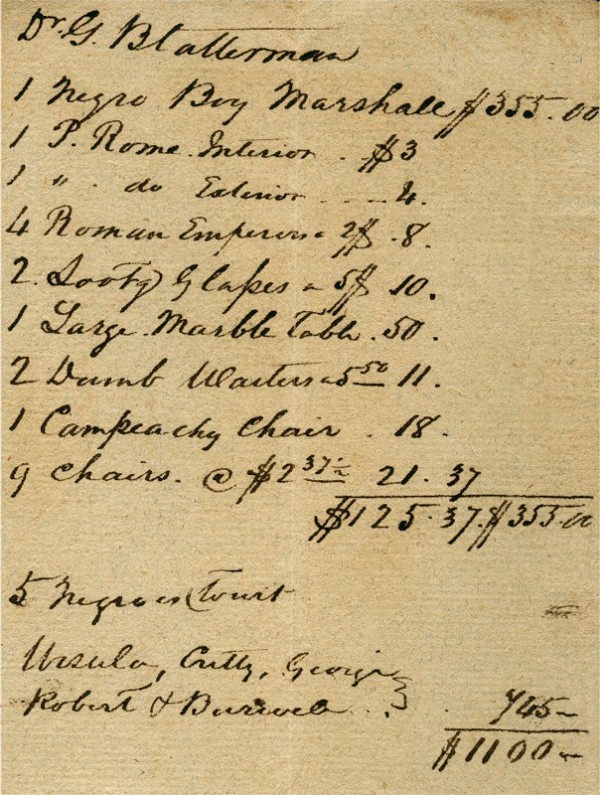

“File of Unsettled Bills to Purchase Articles at the Sale at Monticello, January 1827”. (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.)

Detail of the star inlays on the crest of the Campeche chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Southeast wall of the entrance hall at Monticello. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Charles Shoffner.)

Dining room at Monticello. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Philip Beaurline.) Jefferson kept a volume by Livy on the mantelpiece.

Jean-Baptiste-Claude Sené, folding stool, Paris, France, 1786. Beech. H. 18 1/4", W. 27", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman; photo, Art Resource, NY.) This stool is from a set of sixty-four commissioned for the palaces of Fontainebleau and Compiègne in 1786. Examples from this set or similar stools may have been at the Hôtel du Garde-Meuble when Jefferson visited in September 1786.

Pietro Antonio Martini, Exposition au Salon du Louvre en 1787. Engraving on paper. 12 3/4" x 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.)

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Adélaïde of France, Daughter of Louis XV, Known as “Madame Adélaïde,” Paris, France, 1787. Oil on canvas. 106 3/4" x 76 1/4". (Courtesy, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles; Réunion des Musées Nationaux /Art Resource, NY; photo, Gérard Blot / Jean Schormans.)

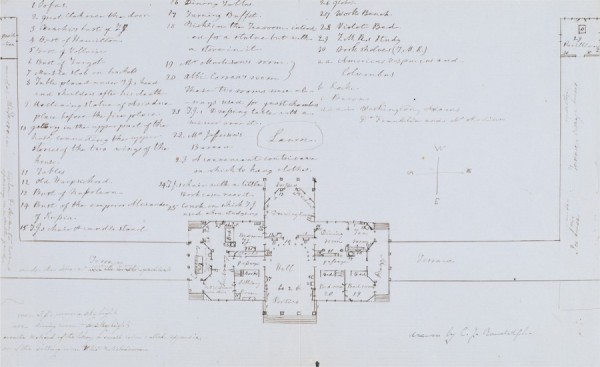

Plan of the first floor of Monticello Drawn by Cornelia J. Randolph, ca. 1826. Ink on paper. 8 1/4" x 13". (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.) Cornelia Jefferson Randolph’s floor plan includes major works of art and large pieces of furniture on the first floor, but it does not mention movables like Campeche chairs.

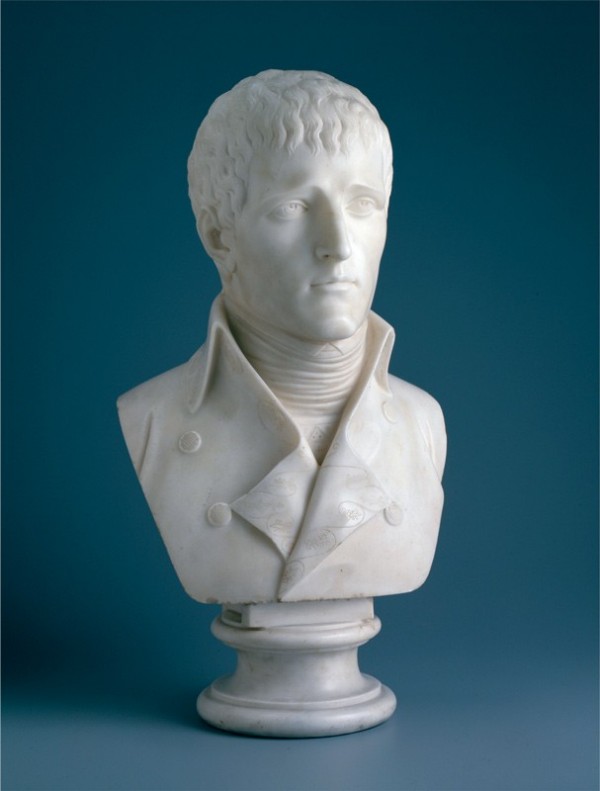

Bust of Napoleon Bonaparte after Antoine-Denis Chaudet, probably France, ca. 1807. Marble. H. 24 1/2", W. 13", D. 10". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello; photo, Edward Owen.)

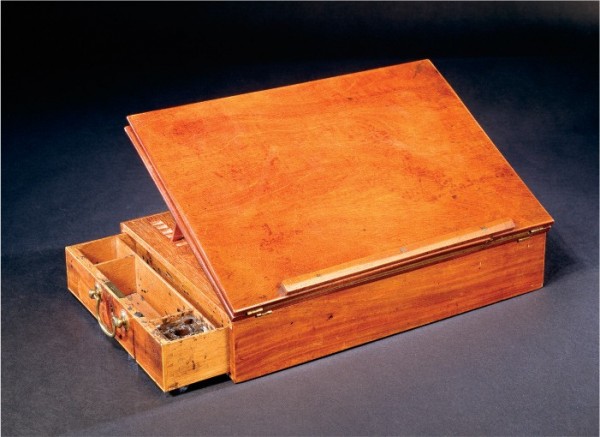

Lap desk attributed to Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1776. Mahogany. H. 9 3/4", W. 14 3/8", D. 3 1/4". (Courtesy, Division of Political History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) has long been associated with the Campeche chair, a lounging form with a curved, reclined back and a sella curulis base (fig. 1). Decorative arts historians have interpreted the example Jefferson owned as a reflection of his knowledge of classical design sources and his refined taste, in addition to its being an object that provided physical comfort during his later years. Recent research now ties Jefferson to the Campeche chair much earlier than previously thought and suggests that the form held multiple layers of meaning for him. Evidence indicates that he probably became interested in the Campeche chair after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, when he acquired an example and used it as part of the furnishings in the President’s House during his residency from 1801 to 1809. For Jefferson and his contemporaries, this chair form no longer alluded to its Roman imperial past but served as a reminder of the Louisiana Purchase and Jefferson’s pivotal role in securing the West for the new nation.[1]

The Campeche chair traces its origins back to folding or cross-legged stools used in ancient Egypt and later Greece and Rome. In his History of Rome, Livy indicated that Roman officials had borrowed the sella curulis from their neighbors the Etruscans. An example can be seen on the silver denarius coin illustrated in figure 2. This version of the chair has curule legs situated laterally, with a boss at the intersection, and ball feet. These chairs became such a significant sign of power in the Roman Republic that their use was confined to consuls, praetors, and, eventually, Roman emperors. The sella curulis evolved into an emblem of authority and majesty and can be found on coins, medals, and monuments of the age.[2]

From its Roman origins, the cross-stool retained its function as a symbol of authority in Europe through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance. One of the best-known survivals is Dagobert’s Throne (fig. 3), once thought to be the throne of King Dagobert I of France (r. 623/29–639). This chair started out as a stool, and a back and armrests were added later in its life. It eventually entered the treasury of the abbey of St.-Denis outside Paris, where Abbot Suger (1081–1155) noted, “We also restored the noble throne of the glorious King Dagobert, on which, as tradition relates, the Frankish kings sat to receive the homage of their nobles after they had assumed power. We did so in recognition of its exalted function and because of the value of the work itself.” The stool remained at St.-Denis until 1791, when the turmoil of the French Revolution led to its removal to the Cabinet of Antiquities and eventually to its current home, the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[3]

During the Renaissance, the curule stool evolved into a chair with a back and attained widespread popularity throughout Europe and Britain. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a variation of the sella curulis known as the sillon da cadera (fig. 4) was widely used in Spain. In addition to having a superstructure of posts, arms, and a low back, the sillon da cadera also had crossed legs oriented to face forward. The Spanish conquistadors brought the sillon da cadera to the New World, and the Campeche chair developed in Mexico from those antecedents. The chair took on the name of the port city of Campeche on the Yucatán Peninsula, which was a primary export center for this form as well as for logwood, a dyewood commonly known as Campeche wood. From Mexico, the Campeche chair made its way to the Spanish territory of Louisiana.[4]

North American chair makers began producing these chairs around 1800. In New Orleans, where the form was in considerable demand, the archetypal Campeche chair has a tall demilune crest, a leather back and seat, flat arms with scrolled terminals, shaped arm supports, a flat front stretcher, and a curule base. The chair illustrated in figure 1 is an early example distinguished by having twelve inlaid stars on its crest. Inlaid crests are relatively common on New Orleans Campeche chairs, but typically the ornament is floral. Although the basic form of the New Orleans Campeche chair remained relatively unchanged, later examples often have turned arm supports and stretchers and occasionally finials with plinths (fig. 5).[5]

It is well documented that a New Orleans Campeche chair was part of the eclectic furnishings with which Thomas Jefferson (fig. 6) surrounded himself, especially during his lengthy retirement at Monticello (fig. 7) and Poplar Forest (fig. 8). In the summer of 1819, when the seventy-six-year-old Jefferson was ill at Poplar Forest, he asked his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772–1836) to send him a Campeche chair, because “While too weak to set up the whole day, and afraid to increase the weakness by lying down, I longed for a Siesta chair which would have admitted the medium position. I must therefore pray you send by Henry the one made by Johnny Hemings.” Forty years later, Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen Randolph Coolidge (1796–1876) recalled that chair’s location in Monticello, noting, “In the large Parlour, with it’s parquetted floor, stood the Campeachy chair, made of goat skin, sent to him from New Orleans, where, in the shady twilight, I was used to seeing him resting.” Indeed, Ellen not only observed his rest but was one of his favorite evening companions. Shortly after Ellen’s marriage in 1825, her sister Virginia Randolph Trist (1801–1882) wrote: “Grandpapa’s health is steadily improving, but I fear he misses you sadly every evening when he takes his seat in one of the campeachy chairs, & he looks so solitary & the empty chair on the opposite side of the door is such a melancholy sight to us all, that one or the other of us is sure to go to occupy it.” Virginia’s letter is evidence that two Campeche chairs were in the parlor, placed on either side of the door that led to the west portico and the lawn beyond (fig. 9). This proximity to the door, coupled with their relatively lightweight frames, meant that these Campeche chairs could also have been used outdoors. None of the family documents mentions what drew Jefferson to this form, but recent research indicates that his association with the chairs began during his presidency and that he most likely sought them out because of their unique ties to New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory.[6]

After being sworn in as president in March 1801, Thomas Jefferson (fig. 10) faced the troubling issue of France and Spain using the Louisiana Territory as a colonial pawn and the possibility that these imperial powers would block American trade into the port of New Orleans. To address this concern, President Jefferson authorized Robert Livingston (1746–1813), United States minister to France, and envoy James Monroe (1758–1831) to negotiate the purchase of what was known as the Isle of Orleans and part of West Florida from France. In April 1803, to the astonishment of these diplomats, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) offered to sell the whole of the Louisiana Territory, an area far larger and more expensive than originally proposed. Livingston and Monroe swiftly agreed to the $15,000,000 price, however, because the advantages for the United States were too numerous to deny. In addition to gaining control of New Orleans, which was Jefferson’s original intent, the purchase would double the size of the United States at a cost of less than 3¢ per acre. Charles Talleyrand-Périgord (1754–1838), Napoleon’s minister of foreign affairs, told Livingston, “You have made a noble bargain for yourselves, and I suppose you will make the most of it.”[7]

On July 3, 1803, Jefferson received word that the treaty had been signed in Paris on April 30, 1803. The American public learned the news on July 4, a propitious day associated with Jefferson as author of the Declaration of Independence. His friend Caspar Wistar (1761–1818) recorded that Jefferson and his contacts considered the Louisiana Purchase “the most important & beneficial transaction which has occurred since the declaration of Independence, & next to it, most like to influence and regulate the destinies of our Country.” France handed New Orleans over on December 20, 1803, with word reaching Jefferson on January 15, 1804. As scholar Junius P. Rodriguez noted, Jefferson was among the first “to comprehend the coast-to-coast notion of American identity that would come to be called Manifest Destiny by the 1840s.” This singular presidential decision opened up the West to the young nation, offering the potential for growth and greatness to future generations.[8]

After appointing William C. Claiborne (1775–1817) territorial governor, Jefferson immediately set as a priority the exploration of these vast new lands. He sent the now-famous Lewis and Clark Expedition into the Northwest, but he was equally interested in the smaller Territory of Orleans to the south, which included the city of New Orleans (fig. 11). In 1804 Jefferson deputized William Dunbar (1749–1810), a scientist, inventor, and planter from Natchez, to explore the southern Mississippi Valley, in what came to be known as the Red River Expedition. Jefferson himself researched and wrote a report titled The Limits and Bounds of Louisiana (1804), which reviewed the region’s history of exploration and ownership by Spain and France in order to delineate the boundaries of the new territory. The report was not widely circulated, but the newspapers of the day gave the content considerable coverage. While some federalist commentators criticized Jefferson’s report for overstating the merits of the region, it offered preliminary information to a nation eager to learn more about the new territory and its history. Moreover, it demonstrates the high level of interest and personal attention Jefferson gave to the acquisition of the Louisiana territory.[9]

Jefferson was not satisfied with just written reports on the new territory, he wanted specimens, objects, and visitors to come to the President’s House (fig. 12). On November 29, 1804, Pierre Derbigny (1769–1829), Jean Noël Destrehan (1754–1823), Pierre Sauve (1749–1822), and the territorial governor, William Claiborne, dined with Jefferson. The French Louisianans had gone to Washington to protest the Governance Act of 1804, which had not created any elected offices or representation for the new American territory. There is no mention of this meeting in Jefferson’s papers, but New Hampshire Senator William Plumer (1759–1850), a federalist, wrote “that [Jefferson] . . . has not made enquires of them relative either to their government, or the civil or natural history of their country—That he studiously avoided conversing with them upon every subject that had relation to their mission here.” Despite his curiosity about the new territory, Jefferson may have felt that it would have been imprudent to discuss the delegation’s demands while the appointed governor sat at the table. After dining at the President’s House just a few days later, Plumer noted that Jefferson had “on the table two bottles of water brought from the river Mississippi.” Whether the New Orleans contingent or Governor Claiborne presented the river water to Jefferson as a curiosity is unknown, but it is likely that one or both brought other objects representative of their region, perhaps including a Campeche chair.[10]

In addition to receiving specimens brought from the new territory by explorers and visitors, Jefferson requested items of specific interest. On August 18, 1808, he wrote to William Brown, collector of the customs for the District of Mississippi, asking for a “campeachy hammock, made of some vegetable substance netted, [which] is commonly to be had at New Orleans. Having no mercantile correspondent there, I take the liberty of asking you to procure me a couple of them & to address them to New York, Philadelphia, or any port in the Chesapeake, to the care of the Collector.” Brown was likely entrusted with this task by virtue of his ties to Jefferson through mutual Trist family in-laws. By October 10, 1808, Brown had fulfilled his commission, but the schooner carrying the hammocks was lost at sea. Although some scholars have posited that the term “campeachy hammock” might be interchangeable with “campeachy chair,” a recently discovered Trist family letter notes that the former was a woven-fiber sling. When he ordered the hammocks in early 1809, Jefferson was nearing the end of his second presidential term and looking forward to his return to private life. Although it is not known what he intended to do with the hammocks, he may well have planned to install them at either Monticello or Poplar Forest.[11]

Jefferson also procured objects from Thomas Bolling Robertson (1779–1828), a Virginian who moved to the Territory of Orleans after finishing his law studies in 1806. A year after Robertson’s arrival in the territory, Jefferson appointed him to the office of secretary of the Territory of Orleans. In 1819 Robertson wrote Jefferson:

I transmit to you a small volume of letters. . . . I hope you will give it the advantage of an agreeable attitude while seated in your Campeachy chair. Many years ago you asked me to send you a few of these chairs; embargo, war, the infrequency of communication between N.O. and the ports of Virginia and my being in Congress prevented me from complying with your request. Meeting with some two weeks ago on the Levee and hearing that there was a vessel then up from Richmond I had them put on; one I sent to my father and the other to you, two men on earth whom I most highly respect. I hope it may answer your expectations; if you wish for more I can now at any time procure and forward them to you.

Although Robertson was not able to send the chairs until nearly a decade after Jefferson left office and after encountering what may have been venture cargo examples on the levee (fig. 13), his letter is proof that Jefferson first asked for Campeche chairs before the Embargo Act, which took effect in December 1807. This indicates that Jefferson knew about the Campeche chair form and was seeking an example for his own use, either publicly or privately, while he resided in the President’s House.[12]

The New Orleans Campeche chair that Robertson sent to Monticello in August 1819 was not the first example Jefferson had owned. A July 28, 1827, editorial in the Daily National Intelligencer reported (fig. 14):

Passing down the Avenue yesterday, I was attracted by an article which was standing in the Cabinet Warehouse of Mr. Henry V. Hill. It is a large Writing and Reading Chair, made, as I understood, for the Department of State; and, for convenience and ingenuity, it excels any I have ever seen. It is of mahogany, made in the form of those Spanish Chairs introduced here by Mr. Jefferson. The legs are short and firm, the back high, and the seat formed of a large sheet of leather suspended from the top of the back, and coming round in a sweep to the front of the frame below, being regulated in its degree of tension by a roller with rack and pinion. The chair has two elbows, made low, and on the outside of that on the right side is an upright iron pillar, from which proceeds a strong arm of iron with a double join, carrying at its extremity a small convenient writing desk, which may be drawn round in front of the person who sits in the chair, or thrown back, or drawn in close to the right hand, at pleasure. The height of this desk is capable of being varied by a screw, so that by means of this double motion, it may be brought into almost any position that the ease of the writer may require. Placed before a bright winter fire, this most convenient establishment secures to a studious man the utmost luxury of comfort, and I feel confident that its general adoption will well reward the ingenuity of the deserving artist who constructed it. S.

The author’s intent may have been to promote cabinetmaker Henry V. Hill’s warehouse, located on Pennsylvania Avenue between 4 1/2 and 6th Streets Northwest, but the notice offers substantial historical information. The chair described in the editorial is clearly of the Campeche form. In reference to seating, the descriptors “Spanish” and “Campeche” were synonymous in the nineteenth century.[13]

The source of Hill’s knowledge of Campeche chairs is not known. He appears to have begun his career at least five years after Jefferson left office and is not mentioned in the latter’s financial accounts or correspondence. If Hill’s Campeche chair was commissioned by the Department of State, as the editorial suggests, that form may have been specified because of its association with Jefferson, who was the first secretary of state under George Washington. The author’s reference to “those Spanish chairs introduced here by Mr. Jefferson” suggests local familiarity with the seating form and reverence for the former president, who by 1827 was considered an icon of the American Revolution and a leading architect of the new republic. Since Jefferson left office eighteen years earlier and never returned to Washington, his introduction of Campeche chairs must have occurred during his presidential term—supporting the hypothesis that a Campeche chair sat in the President’s House and was seen by Jefferson’s visitors. How and when Jefferson acquired his first example is not known, but the most likely scenario is that it arrived after the Louisiana Territory came under American control in 1803.[14]

Jefferson’s family preserved two Campeche chairs as relics of their famous ancestor, but both are too late to be the example that he presumably used in the President’s House. The first chair (fig. 15) has a mahogany frame with a curule base, a flat front stretcher, baluster-shaped arm supports mounted to the outside of the side rail, and flat, S-curved arms, but no turned components. The most striking feature is the extremely tall back and integral upholstered crest. Earlier Campeche chairs typically have applied demilune crests made of wood. The pared-down design of this example suggests that it dates 1815–1820. It may well be the chair that Robertson acquired for Jefferson in New Orleans in August 1819 and that the latter’s granddaughter Ellen Randolph Coolidge described several years later as “made of goat skin . . . [and] from New Orleans.”[15]

After Jefferson’s death, the chair illustrated in figure 15 passed to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1792–1875) of Edgehill in Albemarle County, Virginia. Randolph’s December 1875 estate inventory listed “1 arm chair (upright tall back) 4.00,” which could refer to this chair. The Campeche chair remained at Edgehill until circa 1894, when Randolph’s granddaughter Jane Randolph Harrison Randall (1862–1926) took it to Baltimore. Jane’s husband and son subsequently sold the chair and several other family objects to Monticello.[16]

The other Campeche chair (fig. 16) came down in the family of Virginia Randolph Trist who, with her husband, Nicholas (1800–1874), and young children, was the last Jefferson descendant to live at Monticello. In 1828 her sister Cornelia Randolph (1799–1871) wrote that Virginia’s daughter Martha “begs to be put in the ‘yed [yard] chair’ (the campeache) she is also very affectionate.” Cornelia’s use of “yed chair” and “campeache” as interchangeable terms lends credence to the theory that Campeche chairs were occasionally taken outdoors. About 1828 Nicholas Trist accepted a position at the Department of State and went to Washington, D.C., ahead of his family. On May 8, 1829, he wrote Virginia: “I shall want you to send . . . the low chair (like the one Jefferson gave Mrs. Carr) wh. I left in the pavilion.” Although Campeche chairs are not often described as “low chairs,” Trist may have been referring to the height of the seat rather than the height of the back. Since he did not use the proper term for such seating, he offered a comparison to a chair given by his wife’s brother to a Mrs. Carr. A Campeche chair reputedly owned by a Mrs. Carr, a cousin and neighbor of the Randolphs, remains in the family (fig. 17). The Carr chair is a slightly later version of the Campeche form, featuring turned stretchers in the front and back, simplified arms, and terminal bosses on the crest and curule base.[17]

The Trist chair in figure 16 is made of mahogany and follows the traditional Campeche form fairly closely. Two notable deviations are the tapering arm supports mounted on top of the seat rails and the scalloped crest rail. Another nearly identical Campeche chair is known but has no history. Because of its unusual design and family history, decorative arts scholars have suggested that the Trist chair is the one described as “made by Johnny Hemings” in Jefferson’s 1819 letter. However, it now appears these chairs were made in the New Orleans area and sent to Nicholas P. Trist in 1818, when he lived at Monticello as a guest of Thomas Jefferson.[18]

After Jefferson’s death, his family struggled with the loss of their patriarch and the crushing debt he left behind. In an effort to stave off financial ruin, Jefferson’s heirs sold slaves, livestock, farm equipment, and furnishings from Monticello at public auction in January 1827. A document titled “Inventory of the furniture in the house at Monticello” appears to be a list of the items intended for sale rather than a complete inventory of the house’s contents, since it does not mention certain furnished rooms or such common furniture forms as desks. The sale inventory lists two Campeche chairs, both located in the drawing room. Tradition maintains that David Fowler, a Charlottesville cabinetmaker and coffin maker, purchased one of the chairs, but no documentation verifying that history is known. However, his signature on a petition asking the Virginia General Assembly to save a bust of Jefferson and place it at the University of Virginia’s library confirms his presence at the sale.[19]

George Blaetterman (1788–1850), a professor of languages at the University of Virginia and one of the five original professors hired by Jefferson, clearly purchased one of the Campeche chairs in the 1827 sale (fig. 18). Other purchases included a large marble-top table, two dumbwaiters, artwork, and nine chairs, the latter totaling $21.37. By comparison, the Campeche chair cost $18.00. In 1902 George Walter Blatterman (1820–1910), who changed the spelling of his last name, noted that “Dr. Blaetterman purchased a quantity of second hand furniture, at the sale [including] . . . a ‘siesta’ chair which came from Spain—covered in red leather and with 13 stars at the head.” The professor kept the chair at his home outside Charlottesville until his death in 1850. His estate inventory listed parlor furnishings including “1 Jefferson’s chair” valued at $1.50 and a marble table valued at $10.00. The table may have been the example Blaetterman purchased at Monticello. An account of Blaetterman’s estate sale suggests that Thomas Jefferson Randolph purchased both objects, which were described as “1 Marble Table . . . $6.00/ 1 Chair . . . $4.00.” Randolph may have taken the chair and table back to Edgehill, but there is no definitive mention of either piece in his estate records.[20]

A New Orleans Campeche chair that descended in the Trist-Gilmer families (fig. 1) appears to be similar to the example Blaetterman purchased at Monticello. The twelve inlaid stars on the crest of the Trist-Gilmer chair possibly represent the original twelve parishes that made up the Territory of Orleans (fig. 19). Although George Walter Blatterman wrote that the chair his foster father purchased at Monticello had “13 stars at the head,” it is likely that there were only twelve. Blatterman’s memory could have been flawed, or he may have associated the number of stars with the number of original colonies, which would have been logical, given Jefferson’s involvement in the American Revolution.[21]

Little is known about the early history of the chair illustrated in figure 1, except that it descended in the Gilmer family, who had multiple connections to Jefferson, the Trist family, and the Louisiana Territory. Elizabeth House Trist (ca. 1751–1828) was Jefferson’s lifelong friend, and her son Hore Browse Trist (1775–1804) moved to New Orleans and was appointed by Jefferson collector of the customs for the District of Mississippi in 1803. A year later he died of fever, leaving two sons, his widow, and his widowed mother alone in Louisiana. After her return to Virginia in 1809, Elizabeth House Trist lived with her niece Mary House Gilmer (1785–1853) and her husband, Peachy Gilmer (1779–1836), in Henry and later Bedford counties, but she also spent long spells with friends in Albemarle County. Her grandson Nicholas Philip Trist became Jefferson’s private secretary and in 1824 married the latter’s granddaughter Virginia Randolph.[22]

Writing from his home in Liberty, Virginia, on January 14, 1821, attorney Peachy Gilmer asked Jefferson: “Mrs. Trist some time ago presented me a campeachy chair, which had been sent for her to Monticello, and informed me that you had been so obliging, as to offer it sent to Poplar Forest.” A few days later Jefferson wrote: “the chair which is the subject of your letter . . . was sent to Poplar Forest the last summer, and has only awaited the order of Mrs. Trist or yourself. I write Mr. Yancy this day to deliver it to any person under your order.” Jefferson’s letter to Yancy described the chair as being “crosslegged covered with red Marocco” and noted that it could be “distinguished from the one of the same kind sent up last by wagon as being of a brighter fresher colour, and having a green ferret across the back, covering a seam in the leather.” From Jefferson’s description, he is concisely expressing details to help Yancy distinguish between two very similar chairs, ones not likely made at Monticello, only transshipped from there. This rules out examples made by John Hemmings and indicates that there were two imported Campeche chairs very similar in appearance at Poplar Forest in 1820. This exchange might reference the Campeche chair illustrated in figure 1 and Jefferson’s missing chair with inlaid stars. However, these chairs, which may date to about 1803, were approximately a decade old at the time. Other possible candidates are the Trist chair shown in figure 16 and its near mate that has no provenance.[23]

The Campeche Chair through Jefferson’s Eyes

When he took office, Jefferson introduced a tone at the President’s House and public events that was considerably less aristocratic than that of his federalist predecessors. Through his Republican platform, he sought to establish a less-restrictive social hierarchy and usher in an era of simplicity in politics as well as in everyday life. On January 30, 1804, the National Intelligencer alluded to the egalitarian spirit of his administration in its description of a ball celebrating the transfer of the Louisiana Territory:

The plain unembellished walls of our rooms, the want of splendor, and of that admiration which painting, and gilding, & all artful scenery of architecture can produce, and the still plainer quality of our manners, may, perhaps, to a foreign eye, and to foreign habits, place the grade of such a public festival far below the spectacles that celebrate the achievements of Warriors, or the peace that only suspends . . . destruction—But what humanity rejoices in the extension of the empire of freedom, and of peace, the superficial effects of the arts of the painter, and of the gilder, vanish before the splendor of the event, and put place and form out of consideration.

The Republicans were proud that they had found a peaceful way to expand the nation, while shunning “spectacles that celebrate the achievements of Warriors.” From their perspective, the Louisiana Purchase was majestic in and of itself.[24]

As wonders from the new territory arrived in Washington, Jefferson displayed them at the President’s House so that visitors would be edified and entertained. Depending on when they came, the public could have seen Native American weapons, furs, antlers, skeletons, exotic plants, and live animals, including a magpie and grizzly bear cubs. Many of these specimens were collected during the Lewis and Clark Expedition into the upper Louisiana Territory, shipped south to New Orleans, and from there carried to Washington, Philadelphia, or Monticello. Additional material came from William Dunbar’s Red River Expedition of 1804. The public may have been introduced to the Campeche chair through one of Jefferson’s exhibits, since the novelty of that lounging form and its allusions to Spanish culture would have made it appropriate for display. Jefferson’s penchant for natural history exhibits was well known even before his retirement, as the entry, or Indian, hall at Monticello attests (fig. 20). At the President’s House and Monticello, citizens had the opportunity to learn about the Louisiana Territory and embrace it as an exciting and accessible addition to the nation.[25]

From Jefferson’s perspective, the Campeche chair was more than a totem of the Louisiana Purchase. His classical education meant he had not only read Livy, whose history of Rome mentioned the sella curulis, but considered that text essential reading for students, including his own granddaughters. In 1814 Boston visitor Francis Calley Gray (1790–1856) noted that the mantel in Jefferson’s dining room (fig. 21) was furnished with “many books of all kinds, Livy, Orosious, Edinburgh Review, 1 vol. of Edgeworth’s Moral Tales, etc., etc.”[26]

Jefferson had many opportunities to see curule stools when he served as minister to France from 1784 to 1789. In 1785 he toured the Gothic basilica of St.-Denis, the burial place of French kings and the repository of the treasury, which at that time included Dagobert’s throne (fig. 3). From this relic, Jefferson would have learned that curule seating was not limited to Republican or Imperial Rome but had survived to become a symbol of authority in Europe into the Middle Ages and beyond.[27]

While visiting Versailles and other royal palaces, Jefferson would have encountered pliants, which are a variation of the sella curulis (fig. 22). Pliants, made as either folding or fixed versions of the crossed-legged stool, became common fixtures in public apartments, where court etiquette established by Louis XIV (1638–1715) mandated that only persons of suitable rank were allowed to sit in the presence of the king or queen. When such permission was granted, the recipient typically sat on a pliant. Through such use, the pliant became a powerful symbol of imperial authority.[28]

Jefferson may have seen an evocative representation of a pliant when he attended the Paris Salon of 1787. As Pietro Antonio Martini’s (1738–1797) Exposition au Salon du Louvre en 1787 indicates, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard’s (1749–1803) portrait Adélaïde of France, Daughter of Louis XV, Known as Madame Adélaïde (1787) was prominently displayed at the exhibition (fig. 23). Madame Adélaïde (1732–1800) was the daughter of Louis XV (1710–1774) and aunt of the increasingly unpopular King Louis XVI (1754–1793). The carved and gilded pliant in the foreground of Madame Adélaïde’s portrait (fig. 24) and the medallion profiles of her parents and brother associate her with the stability and majesty of the royal family’s earlier generation. Although Jefferson never mentioned this painting, he may have seen it when he visited Labille-Guiard’s Paris studio. A September 9, 1786, entry in his memorandum book recorded, “Pd. Mlle. Guyard for picture 240f.”[29]

On the same day, Jefferson “Paid seeing Gardes meubles 12f.” The Hôtel du Garde-Meuble held the workshops and administrative arm responsible for furnishing the royal palaces and served as a warehouse for fine furniture, art, the crown jewels, and other historic relics. During his visit, Jefferson may have seen furniture commissioned for the nobility, including neoclassical versions of the pliant (fig. 22), which were enjoying a revival at that time.[30]

Although Jefferson furnished many rooms in his Paris house, no pliants or other curule forms were listed among the furniture he brought back to America in 1790. At that date, this class of seating may not have appealed to Jefferson because of its association with absolutism. By the time he acquired a Campeche chair, however, more than a decade had passed since the fall of the Bourbon monarchy, and the Campeche chair’s classical lineage and later popularity in the Louisiana Territory offered rich possibilities as an emblem of Jefferson’s republican vision for America.[31]

After serving his term, Jefferson made sure that his role in the Louisiana Purchase was demonstrated through his arrangement of art and furniture at Monticello. He kept two Campeche chairs in the large parlor on either side of the portico doors. A floor plan drawn by his granddaughter Cornelia Randolph (fig. 25) indicates that he displayed a bust of Napoleon (fig. 26) behind the chair to the left and a bust of Emperor Alexander of Russia behind the chair to the right. The juxtaposition of a Campeche chair, especially if it was the one embellished with stars, with the bust of Napoleon would have reminded guests and family members of the political victory Jefferson achieved with the Louisiana Purchase.[32]

Jefferson understood that objects could become revered relics and lasting symbols of historic events. Near the end of his life, he sent his granddaughter Ellen Randolph Coolidge the lap desk that he used when drafting the Declaration of Independence (fig. 27), intending it as a gift for her husband, Joseph Coolidge (1798–1879). Jefferson wrote, “if then things acquire a superstitious value because of their connection with particular persons, surely a connection with the great Charter of our Independence may give a value to what has been associated with that [document]. . . . Its imaginary value will increase with the years . . . he [Mr. Coolidge] may see it carried in the procession of our nation’s birthday, as the relics of the saints are in those of the churches.” Jefferson’s words proved prophetic, as the lap desk is now one of the most famous historic objects in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. For Jefferson, the Campeche chairs in his parlor may have been equally symbolic as totems of his role in the Louisiana Purchase and the country’s westward expansion.[33]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks Kay Arthur, Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, Anna Berkes, Jenny Burden, Elizabeth Chew, Jessica Dorman, Lisa Francavilla, Cybèle Trione Gontar, Ellen Hickman, Eric Johnson, Sue Perdue, Gail Pond, Sumpter Priddy III, Jack Robertson, Justin Sarafin, Mary Scott-Fleming, Robert Self, Leah Stearns, Susan R. Stein, Endrina Tay, Carrie Taylor, and Gaye Wilson. I am particularly indebted to David Ehrenpreis, who challenges me to reach and create, both in work and in life.

In Jefferson’s correspondence as well as that of his family, the name “Campeche” is spelled phonetically, usually as “Campeachy.” I have used “Campeche,” the spelling for the port city in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. I thank Sumpter Priddy III for reading this paper in its early stage and for his thoughts on the Campeche chair as a lounging form. See www.monticello.org for more on the modern reproduction of the Campeche chair.

See David L. Barquist and Ethan W. Lasser, Curule: Ancient Design in American Federal Furniture (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003), pp. 26–27. Livy’s History of Rome, Vol. 1, edited by Ernest Rhys (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1905), as posted on http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/tst/ah/Livy/Livy01.html. The most thorough recent work on the sella curulis in antiquity is Thomas Schafer, Imperii Insignia: Sella Curulis und Fasces; Zur Reprasentation römischer Magistrate (Mainz am Rhein: Von Zabern, 1989).

Creating French Culture: Treasures from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, edited by Marie-Hélène Tesnière and Prosser Gifford (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1995), pp. 42–43. This throne is also illustrated in André Jacob Roubo, L’art du menuisier (Paris: L. F. Delatour, 1769–1775), part 3, section 2, pl. 222, 1772. Jefferson owned an unidentified volume of Roubo, noting it as part of his post-1815 retirement library, “#245. Art du Menuisier. Folio.” Jefferson’s Retirement Library, 1815, Thomas Jefferson Papers (hereafter TJP), Library of Congress (hereafter LC). The whereabouts of Jefferson’s copy is unknown. Thanks to Endrina Tay for locating this reference.

For a complete survey of the history of the form, see Cybèle Trione Gontar, “The Campeche Chair in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 38 (2003): 183–212. Also useful is the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, www.getty.edu/vow/AATFullDisplay?find=campeche&logic=AND¬e=&english=N&prev_page=1&subject id=300265223. For more on logwood, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haematoxylum_campechianum.

For more on the Campeche chair in the United States, see Cybèle Trione Gontar, “The American Campeche Chair,” Antiques 175, no. 5 (May 2009): 88–95.

Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, August 24, 1819, TJP, LC. Ellen Randolph Coolidge to Henry Randall, May 16, 1857, Ellen Coolidge Letterbook, Jefferson-Coolidge Family Collection (hereafter JCFC), #9090, University of Virginia (hereafter UVa); Virginia Randolph Trist to Ellen Randolph Coolidge, June 27, 1825, JCFC, #9090, UVa.

Dumas Malone, Jefferson, the President, First Term, 1801–1805 (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1970), pp. 253–59, 284–310. Malone is still one of the best sources for an overview of the complex political events that took place in 1803 and 1804. For the public response to the Louisiana Purchase, see Jerry W. Knudson, “The Jefferson Years: Response by the Press, 1801–09” (Ph.D. diss., University of Virginia, 1962), pp. 199, 207–9.

As quoted in Carolyn Gilman, Lewis and Clark: Across the Divide (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, in association with Missouri Historical Society, 2003), pp. 79–80. The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia, edited by Junius P. Rodriguez (Santa Barbara, Ca.: ABC Clio, 2002), pp. 161–62. Malone, Jefferson, the President, pp. 284, 337–38.

Rodriguez, ed., The Louisiana Purchase, p. 250. Claiborne served as governor from 1803 to 1812. “William Dunbar,” in American National Biography, edited by John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 62–63. Knudson, “The Jefferson Years,” pp. 225–29. Both Jefferson’s and Dunbar’s Louisiana reports are included in Documents Relating to the Purchase and Exploration of Louisiana, edited by Bruce Rogers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin & Co., 1904).

Charles T. Cullen, “Jefferson’s White House Dinner Guests,” in White House History, edited by William Seale (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2008), p. 314. William Plumer’s Memorandum of Proceedings in the United States Senate, 1803–1807, edited by Everett Somerville Brown (New York: Macmillan Company, 1923), pp. 222–23, 212. Knudson, “The Jefferson Years,” p. 225.

Thomas Jefferson to William Brown, August 18, 1809, TJP, LC. See also Receipt from Gilbert H. Smith to William Brown, October 6, 1808, TJP, LC; William Brown to Thomas Jefferson, October 10, 1808, TJP, LC; and Thomas Jefferson to William Brown, May 22, 1809, TJP, LC. Little is written about Brown, who disgraced himself and his family by stealing funds under his care while in office. Diane C. Ehrenpreis, “Trist-Gilmer Chair Research Report,” Curatorial Department, Thomas Jefferson Foundation (hereafter TJF), 2008. Gontar, “The Campeche Chair,” pp. 204–6. For the definitive word on the nature of a Campeche hammock versus a Campeche chair, see Lewis Livingston to Nicholas P. Trist, June 6, 1819, Trist Papers, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (hereafter UNC): “A gentleman who sails today, I believe in the ship Emma has taken charge of your Campeachy hammock and will deliver it [to] Mr. Thorp no 36 Water Street who is requested forward it [to] West Point addressed [to] Mr. O. G. Brandon. All this according [to] the directions I received from your Mother.—I trust it will arrive in time to relieve you from the disagreeable necessity of lying on the hard and stony surface on which your encampment is . . . made—It will undoubtedly tend much your comfort and I have always thought that hammocks of that description or resembling them ought be introduced in our armies as part of the outfit of every soldier—They are not expensive, very durable and easily carried and would free the men from all danger of those numerous complaints caused by the cold and moisture of the earth.”

“Thomas Bolling Robertson,” in Dictionary of American Biography, edited by Dumas Malone, 16 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935), 8: 28. Thomas Bolling Robertson to Thomas Jefferson, August 2, 1819, TJP, LC. The Robertson family chair, which may have been identical to the one sent Jefferson, has not been located.

Anne Castrodale Golovin, “Cabinetmaker and Chairmakers of Washington, D.C., 1791–1840,” Antiques 102, no. 5 (May 1975): 914–15.

Ibid. On October 21, 1828, an editorial in the Daily National Intelligencer commented on a new way of “arranging mounted maps” that the contributor saw in a committee room at the Capitol. The improvement “was in part the contrivance of Mr. Jefferson, but has been much improved by Mr. Hill, an ingenious cabinetmaker of this city.” Hill seems to have been familiar with some of the objects that Jefferson left behind in Washington. John D. Hill, a cabinetmaker and chair maker working in Washington at the same time as Henry V. Hill, was probably Henry’s kin. John apprenticed with William Worthington Jr., a cabinetmaker working in Washington during Jefferson’s era. The author thanks Sumpter Priddy III for sharing information on Hill and Worthington. Gontar, “The Campeche Chair,” p. 207.

For more on chairs with a connection to Jefferson and Albemarle County, see Diane C. Ehrenpreis and Robert L. Self, “‘I Hope it May Answer Your Expectations’: Thomas Jefferson and the Campeachy Chair,” in Louisiana Furniture, edited by Jessica Dorman (New Orleans: Historic New Orleans, forthcoming). H. Parrot Bacot to TJF, 1989, object file, 1946-1, TJF. Bacot’s letter suggests that this is a New Orleans chair and may be the one sent in 1819. Ellen Randolph Coolidge to Henry Randall, May 16, 1857, Ellen Coolidge Letterbook, JCFC, #9090, UVa.

Object file, 1946-1, TJF. George Green Shackelford, “Ellen Wayles Randolph and William Byrd Harrison,” in Collected Papers of the Monticello Association of the Descendents of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Shackelford, 2 vols. (Charlottesville, Va.: Monticello Association, 1984), 2: 81–84. It is not known exactly how Jane Randall came to own most of her relics. The most likely scenario is that they came from her mother, Ellen Randolph Harrison. Ellen and her maiden sisters inherited Edgehill and its furnishings. See Thomas Jefferson Randolph, Will, Inventory, and Estate Sale, Albemarle County Will Book 29, pp. 133–43. Ellen Randolph Coolidge to Henry Randall, May 16, 1857, Ellen Coolidge Letterbook, JCFC, #9090, UVa.

Cornelia Randolph to Ellen Randolph Coolidge, July 6, 1828, JCFC, #9090 UVa. Nicholas P. Trist to Virginia Randolph Trist, May 8, 1829, Trist Papers, UNC. The chair with the Carr family provenance is currently on loan to the TJF.

Object file, 1979-91, TJF. The Trist chair descended in the family until John H. Burke gave it to the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf. The chair was subsequently purchased by the TJF. See object file, 2005-13, TJF, for a related chair. Gontar, “The Campeche Chair,”p. 186, fig. 5. Imported examples with a scalloped leather skirt on the front rail could have provided inspiration for the scalloped crest on the Trist chair. Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, August 24, 1819, TJP, LC. This letter was written from Poplar Forest, where at least one Campeche chair was in use by the late summer of 1819; S. Allen Chambers, Poplar Forest and Thomas Jefferson (Forest, Va.: Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, 1993), pp. 126–27, 158. Jefferson used the term “Siesta chair” as a synonym for a Campeche chair. There is little doubt that is what Jefferson meant, especially with the description of the posture it afforded and the use of the Spanish word for “nap.” “Hemmings” is the accepted spelling for the family surname when discussing John or Priscella, based on their own usage. Other family members went by “Hemings.” The family took at least one other object made by Hemmings with them to Washington. On August 31, 1829, Martha Jefferson Randolph wrote Ellen Randolph Coolidge: “We shall carry all our bedding, some dining tables, your press and Virginia’s tall chest of drawers, and some other articles, including stained bedstead, made by John Hemmings, neater than you would suppose, low post, with head and foot boards.” JCFC, UVa. For more on Hemmings, see Robert L. Self and Susan R. Stein, “The Collaboration of Thomas Jefferson and John Hemings, Furniture Attributed to the Monticello Joinery,” Winterthur Portfolio 33, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 231–48. C. Tournillon to Nicholas P. Trist, April 10, 1818, Trist Papers, UNC. Mary Trist Tournillon to Nicholas P. Trist, May 7, 1818, Trist Papers, UNC. John F. Dumoulin to Nicholas P. Trist, July 23, 1818, Trist Papers, UNC. In 1818 Nicholas Trist lived at Monticello as the guest of Thomas Jefferson. Tournillon, Trist’s stepfather, ordered “les deux fauteuils de Campêche” for Nicholas. He arranged the commission in either La Fourche or New Orleans, taking care with the upholstery. It is probable that the pair of chairs remained at Monticello, an occasional base for the entire Trist family.

For more on the Monticello estate sale, see Susan R. Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1993), pp. 117–20. The inventory is printed in its entirety in ibid., appendix 5, pp. 436–38. James A. Bear Jr., “The 1827 Estate Sale Research Binder,” n.d., Thomas Jefferson Library, TJF. If Fowler did purchase one of Jefferson’s Campeche chairs, he may have done so in order to acquire a prototype for his cabinet shop as well as to take home a relic of his iconic neighbor. Janet Strain McDonald, “Furniture Making in Albemarle County, Virginia, 1750–1850,” Antiques 153, no. 5 (May 1998): 748, 750–51. There is no evidence that David Fowler worked for Jefferson. January 27, 1827, Legislative Petition, Albemarle County, as published in Edmund Berkeley Jr., ed., “Save Mr. Jefferson’s Bust! An Albemarle Petition of 1827,” Magazine of Albemarle County History 27–28 (1968–1970): 117–18.

“File of Unsettled Bills to Purchase Articles at the Sale at Monticello, January 1827,” Jefferson-Kirk papers (hereafter JKP), MSS 5291, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, UVa. Memoirs of George Walter Clements Blatterman, ca. 1902, MSS 10233, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, UVa. For evidence of Blaetterman’s purchases, see “Unsettled Bills, 1827,” JKP, MSS 5291, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, UVa. Although scholars have traditionally assumed that George Blatterman II took objects from Monticello with him when he moved to Kentucky, that was not the case. He did relocate slaves who had been at Monticello. George W. Blatterman Inventory, Albemarle Will Book 19, p. 463; and Estate Sale Account, Albemarle Will Book 20, p. 13. See Thomas Jefferson Randolph, Will, Inventory, and Estate Sale Account, Albemarle County Will Book 29, pp. 133–43. Scholars have traditionally assumed that at least two other chairs that descended in the family of John Hartwell Cocke were purchased at Monticello in 1827, but recent research has proven otherwise. A transcription of Cocke’s receipt from the sale survives, but no Campeche chairs are listed. Bear, “The 1827 Estate Sale Research Binder.” The author thanks Robert L. Self for verifying the Cocke information.

Ehrenpreis, “Trist-Gilmer Chair Research Report.” For a contemporary source on the founding of the Territory of Orleans, see C. C. Robin, Voyage to Louisiana, 1803–1805, edited by Stuart O. Landry Jr. (New Orleans: Pelican Publishing Co., 1966), p. 263. The original twelve parishes were Orleans, German Coast, Acadia, Lafourche, Iberville, Point Coupee, Atakapas, Opelousas, Natchiches, Rapides, Ouachita, and Concordia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_parishes_in_Louisiana). The number of parishes rose to nineteen in 1807 and remained at that number at least until Louisiana became a state in 1812. If the stars on the Trist-Gilmer chair signify the original parishes, the chair probably dates 1803–1807. Memoirs of George Walter Clements Blatterman.

Gerald Morgan Jr., “Nicholas Philip and Virginia Jefferson Randolph Trist,” in Shackelford, ed., Collected Papers of the Monticello Association, 2: 100–113.

Peachy R. Gilmer to Thomas Jefferson, January 14, 1821, Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts (hereafter CCTJM), Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston (hereafter MHi); Thomas Jefferson to Peachy R. Gilmer, January 27, 1821, CCTJM, MHi; Thomas Jefferson to Joel Yancy, January 27, 1821, CCTJM, MHi. Peachy Gilmer attended the Monticello estate sale in 1827, but his only known purchase was “2 pr wine sliders @ 2.55—5.10.” See “Unsettled Bills, Monticello,” MSS 5291, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, UVa.

Knudson, “The Jefferson Years,” pp. 222–23. National Intelligencer, February 2, 1804.

John Whitcomb and Claire Whitcomb, Real Life at the White House (New York: Routledge, 2000), pp. 15–16, 23. Dumas Malone, Jefferson, the President, Second Term, 1805–1809 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974), pp. 184–89. Jefferson selected some of the artifacts for his use at Monticello, and some were sent to Philadelphia to Charles Willson Peale and the American Philosophical Society. An excellent source for the study of the original Native American materials and the reinstallation of the hall at Monticello is Castle McLaughlin, Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection (Cambridge, Mass.: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 2003), pp. 312–15. For the most thorough source on the shipments, their destinations, and their ultimate fate over time, see Gilman, Lewis and Clark: Across the Divide, pp. 335–53. The author thanks Elizabeth Chew for providing these sources. A May 18, 1804, list from the Lewis and Clark shipment survives but does not mention Campeche chairs; Malone, Jefferson, the President, Second Term, p. 184. William Seale, The President’s House, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, with the cooperation of the National Geographic Society, 1986), 1: 96–98. There is no mention of a Campeche chair on the furniture inventory of the President’s House. “Furniture Inventory, President’s House,” February 19, 1809, TJP, LC. For more on the entrance hall at Monticello, see Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson, pp. 64–68; and Elizabeth Chew, “Indian Hall and Museum,” in the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, www.monticello.org/site/house-and-gardens/indian-hall-and-museum.

For more on the dining room at Monticello and related quotes, see www.monticello.org/site/house-and-gardens/dining-room. For Jefferson’s recommended reading for children, which includes Livy, see www.monticello.org/site/childrens-reading.

James A. Bear Jr. and Lucia C. Stanton, eds., Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 1: 587 and 640. Although he did not comment on his experience, he definitely toured the landmark, noting in his memorandum book, “Pd. Breakfast at St. Denis 3f18—gave for seeing church 6f.” In 1804 Napoleon Bonaparte had Dagobert’s throne repaired to use at his coronation, appropriating a symbol of the French monarchy for himself. Todd Porterfield and Susan Siegfried, Staging Empire: Napoleon, Ingres, and David (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), pp. 26–32.

Pierre Verlet, French Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, translated by Penelope Hunter-Stiebel (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991), pp. 64–65. See also www.metmuseum.org/Works_of_Art/collection_database/european_sculpture_and_decorative_arts/folding_stool_jean_baptiste_claude_sene//objectview.aspx?OID=120049831&collID=12&dd 1=12, and www.metmuseum.org/Works_of_Art/collection_database/european_sculpture_and_decorative_arts/folding_stool_jean_baptiste_claude_sene//objectview.aspx?OID=120049832&collID=12&dd1=12.

Jean Cailleux, “Portrait of Madame Adelaide of France, Daughter of Louis XV,” in “L’art du dix-huitième siècle: An Advertisement Supplement to The Burlington Magazine” 3, no. 22 (March 1969): i–vi. Laura Auricchio, “Self-Promotion in Adélaïde Labille-Guiard’s 1785 ‘Self-Portrait with Two Students,’” Art Bulletin 89, no. 1 (March 2007): 56–59. Jefferson did not comment on the Portrait of Madame Adélaïde, but he was very taken with the history painting hung directly beneath it, Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Socrates. He wrote, “The Salon has been open four or five days. I inclose [sic] you a list of its treasures. The best thing is the Death of Socrates by David, and a superb one it is.” Thomas Jefferson to John Trumbull, August 30, 1787, TJP, LC. Bear and Stanton, Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, 1: 638.

Howard C. Rice Jr., Thomas Jefferson’s Paris (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 26. The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently acquired a study by David, The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, ca. 1787. In this picture David used a sella curulis with inward-facing lion’s-paw feet and legs. In the finished painting the artist replaced the stool with a klismos chair, another form from antiquity; see www.metmuseum.org/ah/hd/jldv/ho_ 2006.264.htm.

“Grevin Packing List,” July 17, 1790, William Short Papers, LC. The National Intelligencer and Daily Advertiser, April 26, 1805. In the early Republic, seating forms were still associated with positions of authority. Newspapers frequently mentioned Jefferson taking the “Presidential Chair” or “the chair of state.”

Jefferson, Randolph, Trist Family Papers, 1791–1874, MSS 5385-ac, UVa. For more on both sculptures, see Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson, pp. 225, 232–33. The circumstances of Jefferson acquiring the sculpture of Napoleon Bonaparte are not known.

H. M. Kallen, “The Arts and Thomas Jefferson,” Ethics 53, no. 4 (July 1943): 275–76. As quoted in Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson, p. 364. James A. Bear Jr., “Declaration of Independence Desk,” in Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, at www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/declaration-independence-desk.