Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1720. Maple. H. 45 1/2", W. 18", D. 14 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

François Boucher, The Luncheon, Paris, France, 1739. Oil on canvas. 32" x 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Louvre; photo, Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1720. Maple. H. 45", W. 17 1/2", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Thomas d’Urfey, The Curtain Lecture, London, England, ca. 1690. Etching on paper. 12 1/2" x 13". (Courtesy, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.) A cane chair is pushed against the wall in the background.

Detail of the right front leg and seat of a side chair, England, 1710–1720. Walnut. H. 44 5/8", W. 20 1/4", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Wallace Nutting Collection, gift of J. P. Morgan.)

Portrait of an Elderly Woman, attributed to Jacob Backer, Holland, 1632. Oil on canvas. 50 3/8" x 39 1/8". (Courtesy, Trustees of the Wallace Collection, London; photo, Art Resource, NY.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Maple and oak. H. 37", W. 20 1/2", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. J. Insley Blair; photo, Gavin Ashworth/Art Resource, NY.)

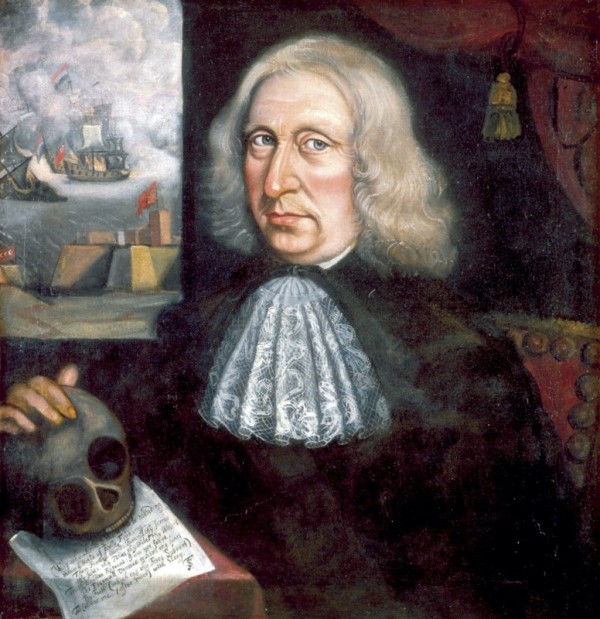

Thomas Smith, Self-Portrait, Massachusetts, 1680. Oil on canvas. 24 5/8" x 239/16". (Courtesy, Worcester Art Museum.)

Side chair, London, England, 1705–1715. Walnut. H. 55 1/2", W. 18 7/8", D. 21 5/8". (Courtesy, V&A Images.)

Detail of The Tea-Table, England, 1710. Engraving on paper. 8 1/8" x 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.)

William Hogarth, The Denunciation, London, England, 1729. Oil on canvas. 19 1/2" x 26". (Courtesy, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.)

Ruben Moulthrop, Portrait of an Unknown Man, New England, 1770–1790. Oil on canvas. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the crest of a side chair, England, ca. 1670. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Armchair, London, England, 1709. Walnut. H. 66", W. 29 7/8", D. 26". (Courtesy, St. Paul’s Cathedral.) This chair originally had a caned seat and back.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1705. Maple. H. 38 3/8", W. 17 3/4", D. 14 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

John Smibert, The Bermuda Group, Boston, Massachusetts, 1729. Oil on canvas. 69 1/2" x 93". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Isaac Lothrop; photo, Art Resource, NY.)

Trade Card for Richard Lee, after William Hogarth, London, England, 1733–1745. Etching on paper. 6 1/8" x 8 7/8". (Courtesy, Heal Collection, British Museum.)

Thomas Roberts, coronation chair for Queen Anne, London, 1702. Carved beechwood and gilding, modern upholstery. H. 68 1/8", W. 34 3/8", D. 38 1/4". (Courtesy, Hatfield House.)

King Charles II, attributed to Thomas Hawker, England, ca. 1680. Oil on canvas. 89 1/4" x 53 3/8". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, London.)

John Smibert, Daniel, Peter, and Andrew Oliver, Boston, Massachusetts, 1732. Oil on canvas. 39 1/4" x 56 7/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Compact, diminutive in scale, and minimally ornamented with a truncated crest and a tiny beaded edge, the early-eighteenth-century Boston cane chair is easy to overlook (fig. 1). In a gallery filled with elaborately carved rococo surfaces and muscular baroque curves, the chairs read as simple and even underdeveloped—mere skeletons in comparison with the more robust seating furniture made later in the century. But the unassuming character of the chairs has encouraged rather than stymied scholarly interest.

Benno Forman was the first scholar to consider the chairs seriously. In American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730, he identified twenty-six examples of the form in museums and private collections, enumerated their shared stylistic features, and connected the chairs to a broader international taste for designer Daniel Marot and the Georgian aesthetic that came to fruition in seating furniture of the 1740s. Forman also speculated that the “I” on the back rail of nineteen of the chairs was the mark of a caner’s shop.[1]

Forman’s interpretation laid the groundwork for Glenn Adamson’s consideration of the chairs’ symbolic content. In a 2002 essay, Adamson drew a distinction between the high-backed late-seventeenth-century cane chair and its early-eighteenth-century Boston counterpart. As internationally traded commodities shipped from London to a variety of English and colonial ports, the former was tied to the economic theory of mercantilism. Elaborately carved, showy surfaces were consistent with mercantilism’s drive to encourage middle-class consumption. By contrast, the latter form was more exclusive. Its nascent Georgian features “marked . . . the transition [to] a new concept of taste and fashionability” associated with the British elite.[2]

This essay builds on Forman’s and Adamson’s analyses and considers the one aspect of the early-eighteenth-century Boston caned chairs they overlooked: their function as seats (fig. 2). While both scholars discuss the people who owned and used the chairs (members of the Boston elite), and while they detail the places where the chairs were used (new social sites like the tea table), they pay virtually no attention to the physical relationship between user and object. This relation is the subject of the pages that follow.

Leading scholars of American art have long encouraged decorative arts historians to pursue questions about the embodied experience of furniture. In discussing his method for studying material culture, Jules Prown advises the interpreter to “imagine what it felt like to interact with the object.” Literary historian Philip Fisher is even more forceful on this point: he argues that everyday objects “can only be understood by preserving the image of the user hovering nearby.” “Most functional objects,” he asserts, “imply the human by existing like jigsaw pieces whose outer surfaces only have meaning when it is seen that they are designed to snap into position against the body.”[3]

Yet with a few important exceptions, furniture scholars—and specifically scholars of American decorative arts—have tended to avoid questions about how the object under study relates to the body that uses it. Essays, catalogues, and museum displays frame the historic piece of furniture as a self-contained unit of information—a code to be cracked—rather than as the jigsaw-puzzle pieces Fisher describes. The illustrations in most collection catalogues and material culture studies reflect this sensibility. They typically present the object alone on a bright white background, cut off from the context of use and bodily experience.[4]

This essay takes Prown’s and Fisher’s call as a starting point by inserting the embodied user into the history of the cane chair. The relation between sitter and chair took many different forms in the early eighteenth century. Sitters moved chairs, moved around them, and perceived them. They put their feet up on the objects, knocked them over, and occasionally snapped them apart. They stood on chairs and threw clothing over their backs. But the chairs were built to accommodate a sitter, and the focus here is the experience of a seated body.

The body is a historically and culturally conditioned artifact—as much a part of its time as any material object—and the contemporary interpreter can never experience a chair in the manner of a sitter from the past. Yet using evidence gathered from close study of the surviving objects, images, and texts that depict the chairs in use and considering the social codes that governed the act of sitting, it is possible to understand the physical relationship that a chair was built to enter into and to facilitate. The I-chairs were designed to relate to the sitter’s body in a way radically different from earlier chairs. This new relationship divested chairs of their earlier signification. Ultimately, the chairs reflect a new set of elite ideas about status and identity that emphasized the value of intrinsic qualities over and above extrinsic material objects.[5]

At the same time that this essay offers new insight into the early-eighteenth-century Boston caned chair, it also shows the value of adding an experiential lens to the furniture historian’s interpretative toolkit. It is important to emphasize that this lens should augment rather than take the place of the standard questions furniture historians ask about manufacture and distribution. What follows is one interpretative strategy to help flesh out existing narratives about the connection between historic objects and the moment when they were produced.

The Disappearing Chair

Let us begin with the chairs themselves. The typical early-eighteenth-century Boston cane chair was diminutive in scale with a small seat and a short back, at least when compared with the high-backed cane chairs popular in the 1690s (fig. 3). The chairs had minimally ornamented carved crests, molded stiles, rectilinear seats with flat outside edges, turned legs tenoned into the bottom of the seats, and evidence of aprons (now missing in most of the objects). Estate inventories and upholsterers account books suggest that cushions were occasionally placed on the cane seats. The chairs were acquired in sets of six or twelve and were largely owned by members of Boston’s merchant upper class. Urban and upwardly mobile, this elite group redefined the domestic interior as a flexible space. They stored pieces of furniture against the wall and brought them into the center of the room to furnish new social rituals like tea drinking (fig. 4). The cane chairs were well suited to this new environment because their lightweight materials made them easy to move.[6]

What was it like to sit in a cane chair and how did the physical relationship between sitter and chair differ from that which existed between sitters and earlier pieces of furniture? There is actually little evidence to suggest that sitting in a cane chair felt much different from sitting in earlier chairs. Historian Russel Lynes has distinguished between “passive” furniture on which we “impose our will to derive the greatest degree of comfort” and “disciplinary” furniture, which forces us into a particular posture or mode of behavior, and the seating furniture fashionable in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was almost all in the latter camp. The codes of gentility and politeness that pervaded social life across Europe and North America in the early modern era elevated the body—and the erect body and upright posture of the sitter—into a marker of class. As Mimi Hellman has explained in her analysis of eighteenth-century French furniture, chairs were designed to encourage the body to assume the proper elite position. They “refigured the body in much the same way as the system of clothing . . . through designs that shaped the body’s movement and appearance.” Boston cane chairs stand among the many British and colonial American objects that worked to this end. Their narrow backs, small seats, and fragile construction forced the sitter to sit bolt upright. Measuring fifteen to seventeen inches across, the chairs offered no support to sitters who leaned left or right. And if one did lean, the chairs were liable to break apart. In many examples of the form, the front legs are tenoned into the bottom of the seat rather than extending up as part of a mortise-and-tenon frame (fig. 5). Inherently unstable, this joint was prone to loosen and snap under the pressure of the sitter’s shifting weight.[7]

While the restrictive agency of the early-eighteenth-century cane chair was characteristic of earlier examples of seating furniture, there was nothing familiar about observing a person seated in such an object. Hellman explains that the codes of gentility that governed social life in the eighteenth century made every sitter into “a potential object of observation.” For observers, for friends seated across the tea table or rivals in cards, or for servants waiting as master sat, the physical relationship between the I-chairs and the sitter’s body looked radically different from the way chairs and bodies had looked in the past. Exploring this aspect of the relation between sitter and chair offers the key into understanding the larger cultural pressures at stake in these objects.[8]

Most of the seating furniture produced in the seventeenth century was proportioned to enframe the body. Armchairs were always wide enough to encompass their sitters (fig. 6), and the leather and upholstered side chairs fashionable in the period were often similarly scaled (fig. 7). Typically measuring twenty inches across, they were wide enough that their corners remained in view even when sitters were attired in the period’s billowing garments. These proportions help to explain the tendency to ornament the borders of the side chairs with bright brass nails or, in the case of upholstered chairs, fabric fringe. This ornament remained in view both when the chair was unoccupied and set against the wall and when it functioned as a seat, as the ornamented edges of the chairs peeking out from behind the sitter in paintings like Thomas Smith’s Self-Portrait suggest (fig. 8). (The projecting finials on turned chairs and the projecting ears on rococo chairs also were visible when the sitter leaned his back up against the object.)[9]

One class of late-seventeenth-century chairs did not enframe the sitter: the high-backed cane chairs popular between 1690 and 1715 (fig. 9). To encourage the proper upright posture, the backs of these chairs were only as wide as or in some cases narrower than the sitter’s back. Period depictions of the chairs in use, like the English engraving The Tea-Table, show that the sitter’s shoulders extended beyond the sides of the object (fig. 10).

If the high-backed cane chairs did not enframe the sitter as the side chairs of an earlier generation did, they still remained visible when occupied. What the chairs lost in width, they gained in height. Elevated fifty-three to fifty-five inches above the floor, the crests of the high-backed cane chairs are best understood as carved wooden crowns. As paintings like William Hogarth’s The Denunciation and Ruben Moulthrop’s portrait of an unknown man suggest, the crests were tall enough to perch just above the sitter’s head even when the sitter donned one of the period’s stylish tall wigs (figs. 11, 12). (Moulthrop depicts a derivative but similarly scaled and ornamented form, the banister-back chair.) The crests on the surviving corpus of high-backed chairs are elaborately decorated, often with motifs well suited to a position above the sitter. For example, the popular “boyes and crown” pattern presented a crown lifted by a pair of hovering cherubs (fig. 13). One exceptional sixty-six-inch-tall caned armchair built for the bishop of London was appropriately capped by a bishop’s miter (fig. 14). Other motifs referenced the sitter’s head more abstractly. For example, the C-scroll pattern on many crests could easily blend in with the curls of a male sitter’s wig.[10]

Though there must have been exceptional cases in which a sitter extended over the sides of a leather-upholstered chair or a gentleman with a particularly elaborate wig obscured the crest of a high-backed object, it is safe to surmise that, generally speaking, late-seventeenth-century New England seating furniture remained visible when occupied. In a culture that knew the chair as an object that enframed and projected over its sitter’s head, the early-eighteenth-century cane chair was a decided anomaly.

Averaging forty-two inches tall, seventeen inches wide, and fifteen inches deep, they were as narrow as the high-backed cane chairs, yet they were typically more than ten inches shorter. Though little comprehensive data exists about the height of Boston adults in the early eighteenth century, muster rolls indicate that the average height of the male soldiers stationed in New England in this period was five feet seven inches. (Unfortunately, no data exists on the height of women.) Extrapolating from this data to the approximate height of a sitter suggests that the backs of the I-chairs were just tall enough to jut into the base of the neck or, in the case of the “molded scoop” crests fashionable in English versions of the diminutive cane chairs, to dip below the neck toward the shoulders (fig. 15). Thus, when viewed from the front, the back of the chair that had once projected over the body now disappeared behind it. (The chairs remained visible beneath the sitter when viewed from the side.)[11]

The new relationship between sitter and chair can be seen in period imagery. Before discussing this visual evidence, it is important to note that painters often had their own symbolic and iconographic agendas, and individual depictions of people using furniture must be considered carefully, and not simply admitted as fact. But when a consistent pattern emerges among multiple artists, the interpreter may be more willing to accept period representations as reliable evidence. Such is the case in the early eighteenth century. Artists in both Boston and London presented seated figures without any trace of a chair above or around them. For example, in John Smibert’s iconic portrait The Bermuda Group, the women seated behind the table covered in a cupboard cloth seem almost to hover (fig. 16). The only indication that they are supported by chairs is the draped hand of the central standing figure, which appears to be gripping the back of a crest. Chairs are also absent in a trade card engraved for tobacconist Richard Lee (fig. 17). Though three low-backed cane chairs are visible in the foreground, no chairs are visible under the two men on the far side of the table at the left. Hogarth presumably expected his viewers to be fluent enough with the scale of period designs to understand that these men also occupied low-backed chairs.[12]

Forman, Adamson, and the other scholars who have written about the I-chairs always note that the objects were shorter than their predecessors. In their object-centered focus, however, they overlook the profundity of this shift. Boston chair makers not only broke away from the scale of earlier seating furniture; they created a group of chairs that related to the body in a radically different way than chairs from the past. To observe a person from the front seated in a cane chair was not to see a body bordered in brass tacks and fringe or crowned by a carved ornament. Instead, like viewing a person seated on one of the stools that dominated New England homes in the early seventeenth century, it was to see a body with no object surrounding it at all.

Excess

Why did chairs that disappeared behind their occupants come into fashion in Boston in 1720? One way to answer this question is to return to the matter of style. In American Seating Furniture, Forman argued that the early-eighteenth-century chairs were connected to a broader stylistic turn away from the high baroque aesthetic that had dominated seating furniture in seventeenth-century New England. In his words, they constituted a fourth phase in the development of the cane chair and reflected “another idea about the styling of chairs . . . inspired by the engravings of such men as Daniel Marot.” Marot’s engravings presented chairs with low backs, and one could argue that the shift engendered by the I-chairs was simply symptomatic of the international adoption of his ideas. (It is also tempting to speculate that Marot’s designs responded to another set of changes in clothing or hairstyle that necessitated a lower-backed chair, though there is little evidence to support this claim.)[13]

Yet an explanation focused on stylistic shift is only partially satisfactory. While new aesthetic ideas certainly played a role in the affect the I-chairs engendered, these ideas do not account for what was lost when the part of the chair that projected beyond the sitter was eliminated. What was lost was nothing less than the signifying power of earlier objects.

Moving backward in time allows us to consider the symbolic role played by projecting crests and sides in earlier seating furniture. Just when they were fashionable in middle-class forms, these design elements were also common features of English royal thrones and chairs of state. In the discussion of furniture in his 1688 treatise The Academy of Armory, an encyclopedia of heraldic symbols and the “instruments used in all trades and sciences,” Randle Holme identified the “throne or seat of majesty” as a “chair of gold richly imbossed, mounted upon steps, with the achievements of the sovergn set over head and under a rich canopy with valence curtains fringed and imbroidered with silk.” The coronation chair that Thomas Roberts built for Queen Anne in 1702 fits this description (fig. 18). Capped by an elaborate gilded crest and bordered by red tassels, the object looks like a large-scale hybrid of a high-backed and an upholstered side chair. Its grandeur is matched by that of the thrones in period images. For example, in Thomas Hawker’s depiction of King Charles II, the king sits in a giant throne dominated by a massive gilt and carved crown that surrounds him like a giant halo (fig. 19).[14]

The crests and projecting sides of these royal objects obviously did not serve any functional purpose. Neither played any role in supporting the sitter’s weight. Instead, their function was communicative. In a culture where most people sat on the ground or on stools, they differentiated the king and conveyed what Holme described as his “immutability and authority.” At the same time, as parts of the chair that stood in excess of the object’s practical requirements, they marked the king’s wealth in an era when most could only afford the bare necessities.[15]

Principally sold in sets and owned by members of the Boston and London middle class, the late-seventeenth-century domestic seating furniture did not convey any claim to royal power. But the projecting sides and crests of these chairs still expressed excess, the same way in the domestic sphere as it did in the royal one. As historian Timothy Breen, among many others, has explained, the “luxuries and superfluities of life . . . communicated claims to social status.” Ornamented silver, expensive clothing, coaches, portraits, and elaborately decorated pieces of storage furniture “spoke to contemporaries of class and gender, identity and status” and defined one as a member of the middle class. The chairs stand among these symbolic objects. Indeed, one Boston writer in 1719 identified cane chairs among the fashionable objects like “fine costly shoes and pattoons, ribbons, rich lace, silk hankercheifs, fine hatts, gloves . . . and China ware . . . which have not been necessary, yet very costly.” Among all of the period’s symbolic goods, the chairs functioned most like pieces of clothing because their excess was designed to communicate in relation to the sitter’s body. To observe a person crowned by a carved crest or enframed by brass tacks and silk fringe was to observe a person ensconced within a symbol of the expendable capital that marked a social position over and above that of the poorer, inferior ranks.[16]

This brings us back to the I-chairs. Lost when the chair was scaled to disappear behind the body was the part of the chair that conveyed and confirmed social identity when the chair was in use. Reduced in height and width, the I-chairs were shorn of the excess that possessed communicative power. Like the common stool, they were chairs that functioned on the most basic level. To observe a person seated in one of these objects was simply to observe a face, a face devoid of the signs of expendable wealth and social position that had surrounded sitters in the past (fig. 20).

A Chair for the Boston Elite

At this point, we are in a position to rephrase the question posed above. Rather than ask why a chair that disappeared behind its sitter came into fashion in 1720s Boston, we can ask what cultural pressures made a chair desirable that was shorn of the identity-conferring excess that had traditionally surrounded the sitter. The best way to answer this question is to consider the chair’s owners. On the basis of family histories, Adamson notes that these chairs were owned by members of the Boston elite, including the Aldens, Hancocks, and Holyokes. The beliefs and values of this group and their response to the rise in middle class consumption helps to explain the connection between the chairs and the moment when they were produced.[17]

Historians have shown that the growing economic power of the middle class at the beginning of the eighteenth century made elites uncomfortable. As Breen explained, this group viewed middle-class consumers “as a threat to their own social standing.” Historically, only the elite could afford goods with superfluous qualities, and they acquired these goods to convey their position at the top of the social hierarchy. But once excess became a staple of middle-class objects like the high-backed cane chair, the elites feared that traditional social categories would be confused and their social authority weakened. “As more and more ordinary people purchased British manufactures, they inevitably transgressed the older boundaries of class and status. . . . In the new order almost anyone of moderate means seemed capable of presenting himself, at least in terms of material possessions, as a gentleman.”[18]

Elites responded to this disruption in the social order by calling for a return to an older, medieval and Renaissance model of class distinction in which innate qualities like a distinguished name and family lineage rather than visible possessions defined social status. The argument for this model surfaced throughout early-eighteenth-century Britain and colonial America, but few writers expressed it as clearly and forcefully as Charles Rollin. Rollin was a French historian made famous by his multivolume histories of ancient Greece and Rome. In his 1726 work the Traité des études, which was available in English in both Boston and London, Rollin changed course to study education and emphasize the value of learning from the ancients. Most pertinent here are the lessons Rollin drew from the ancients’ attitudes toward status and identity.[19]

At the beginning of a chapter entitled “Of Furniture, Dress and Equipage,” Rollin observed that his contemporaries use objects to convey and uphold their social status. “The most part of mankind placed their greatness in [furniture, dress and equipage]. . . . They swell and enlarge the idea they form of themselves, as much as they can, from these outward circumstances.” But this, Rollin argued, was a naïve practice. Things were hollow and artificial bearers of identity: “What renders a man truly great and worth of admiration is neither riches, magnificent buildings, costly habits or sumptuous furniture, neither a luxurious table.” The model of the ancients showed that true greatness was vested in intrinsic qualities: “A man owes his real worth to his heart.”[20]

Rollin bolstered his argument for the connection between greatness and intrinsic qualities by citing heroes from antiquity. Scipio Aemilianus, the ruler of Carthage who was “descended from one of the most illustrious families in Rome, and adopted into one of the richest,” “never made any acquisition in his life.” His “greatness” was defined and conveyed by “his person alone, without any other attendance than that of his virtues, his actions, and his triumphs.” Similarly, Agesilaus, king of Lacedemon, “gained reverence” through “his name, his reputation and his victories.” He traveled around “in a very plain dress” and “without further ceremony, sat himself down upon the grass.”[21]

As these examples and others like them in the text suggest, “greatness” correlated to the position of the kings at the top of the social hierarchy, and the intrinsic qualities that defined greatness included the name and family lineage that people born into this position possessed. Rollin’s argument, then, is far less democratic than it seems. What he meant by an identity defined by the “heart” was an identity to which the elite alone had access.

The Traité des études and the numerous other writings available in Boston and London that echoed Rollin’s arguments help to explicate the desirability of the cane chairs. Shorn of the symbolic excess of earlier pieces of seating furniture, the chairs were well suited to a sitter who sought distance from the newly monied who “swell[ed] . . . themselves” with “outward circumstances.” Proportioned to privilege the sitter’s face, these objects were appropriate to elites who subscribed to the view that intrinsic qualities rather than external goods conveyed and upheld identity. Unencumbered by elaborately decorated borders or lavishly carved crests, members of the Alden, Hancock, or Holyoke families could lay claim to the greatness of Scipio and Agesilaus and show observers that their identities were vested in the face and by extension the name and family lineage to which they alone had access.

Rollin’s language offers the best set of terms to articulate the chairs’ cultural significance. At the conclusion of “Of Furniture, Dress and Equipage,” he slightly shifted his focus and advised the reader on the best way to judge the identity of others:

To pass a right judgment upon their greatness we should examine them in themselves and set aside for a few moments their train and retinue. Strip them of this advantage, and reduce them to their proper standard, or their just proportion. . . . Whatever is external to a man . . . does not make him truly valuable. We must judge of a man by the heart.[22]

The cane chairs allowed for this “right judgment.” They “strip” the sitter of his “advantage” and “reduced” him to a “proper standard,” a “just proportion.” Obscured behind the sitter’s back, they allowed the observer to “examine” sitters “in themselves” without the influence of “their train and retinue.” They enabled the observer to “judge of a man by the heart.”

This interpretation raises questions of intentionality, and it is important to be clear that eighteenth-century Boston chair makers were probably not reading Rollin and translating his ideas into material form. Instead, consumers were the conduits that carried the new ideas about identity into design. In all likelihood, this process was neither deliberate nor even conscious. With Rollin echoing somewhere in the back of their minds, members of the Boston elite found some inexpressible value in the short-backed chairs and continued to acquire and commission the objects.

Conclusion

Although this reading initially appears incompatible with Adamson’s assertion that the early-eighteenth-century caned chair was a fundamentally communicative object, further research might reveal a more nuanced relation between these two interpretations. What if, unlike late-seventeenth-century seating furniture, the communicative function of the chairs depended on the physical position of the objects? What if the chairs communicated the class position of their owners when not in use but reflected Rollin’s ideas about the intrinsic basis of elite identity when occupied? In other words, might the I-chairs function symbolically when they were stored against the wall but cease to communicate when they actually came into contact with the body? Were other furniture forms characterized by this duality?

These are all questions for a more extended study. Together with the larger interpretation put forward here, they illustrate the new issues and insights that follow from a consideration of the physical relationship between a historic piece of furniture and the body it was intended to serve. Though chairs, chests, and tables may constitute mysterious and compelling texts to contemplate in and of themselves, they were built to serve bodily needs and to participate within the fabric of sensuous bodily experience, and they are best understood—indeed, only understood, to return to literary historian Philip Fisher’s eloquent phrasing—by imagining “the user hovering nearby.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Glenn Adamson, Dennis Carr, Jon Prown, Kate Smith, and members of the Newberry Library Seminar in American Art for their comments on earlier versions of this article and Randall O’Donnell for his insights into the construction of the cane chair.

Benno Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988), pp. 229–81. For English chairs, see Adam Bowett, English Furniture: 1660–1714 (London: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2002), pp. 84–85; David Dewing, “Cane Chairs: Their Manufacture and Use in London, 1670–1730,” in Regional Furniture 22 (2008): 53–81; and R. W. Symonds, “The Export Trade of Furniture to Colonial America,” Burlington Magazine 77 (November 1940): 152–63. See also Symonds, “English Cane Chairs, Part I,” Connoisseur (March 1951): 8–15, and “English Cane Chairs, Part II,” Connoisseur (May 1951): 83–91.

Glenn Adamson, “The Politics of the Caned Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 175–206, at p. 203.

Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” in Art as Evidence: Writings on Art and Material Culture (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2001), p. 81; Philip Fisher, Making and Effacing Art: Modern American Art in a Culture of Museums (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 243–44.

Katherine Grier and Mimi Hellman have broken with the existing paradigm and made headway in explaining the phenomenological experience of objects. See Grier, Culture and Comfort: Parlor Making and Middle Class Identity, 1850–1930 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1996); Hellman, “Furniture, Sociability, and the Work of Leisure in Eighteenth-Century France,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 32 (Summer 1999): 415–45; and Hellman, “Interior Motives: Seduction by Decoration in Eighteenth-Century France,” in Harold Coda, Andrew Bolton, and Hellman, Dangerous Liaisons (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), p. 19.

For one of the most recent of the many investigations of this topic, see Angus Trumble, The Finger (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2010).

Reinier Baarsen et al., Courts and Colonies: The William and Mary Style in Holland, England and America (New York: Cooper Hewitt Museum, 1988).

Quoted in Michael Ettema, “Nostalgia and American Furniture,” Winterthur Portfolio 17 (Summer 1982): 141. Hellman, “Furniture, Sociability, and the Work of Leisure,” p. 430. For scholars who have commented on the chair’s structural weakness, see Symonds, “English Cane Chairs, Part I”; Wallace Nutting, who remarks that they are “apt to grow shaky,” in Furniture Treasury (1928; reprint, New York: Old America, 1980); and John Kirk, who comments on their “precarious beauty” in American Furniture: Understanding Styles, Construction and Quality (New York: Harry Abrams, 2000), p. 65.

Hellman, “Furniture, Sociability, and the Work of Leisure,” p. 429.

For a discussion of period clothing styles, see Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2002).

For a fascinating set of earlier chairs whose crests evoke the carving on period gravestones and thus make the sitter look like the transcendent faces on those objects, see Ethan W. Lasser, “Making Things Matter: The Chipstone Galleries at the Milwaukee Art Museum,” Winterthur Portfolio (forthcoming).

Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 306, discusses these chairs.

Jonathan Prown, “John Singleton Copley’s Furniture and the Art of Invention,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the: Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 153–205.

Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 237. Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal, pp. 222–36.

Randle Holme, The Academy of Armory, or, A Storehouse of Armory and Blazon (London, 1688), n.p.

Many historians have discussed this condition, including Cary Carson, “The Consumer Revolution in Colonial British America: Why Demand?” in Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Carson, Ronald Hoffman, and Peter J. Albert (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), pp. 483–697.

T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 150–54. “The Present melancholy circumstances of the province consider’d, and methods for redress humbly proposed, in a letter from one in the Country to one in Boston” (Boston, 1719), p. 4 (retrieved from Early American Imprints, Series I: Evans, 1639–1800).

Adamson, “The Politics of the Caned Chair,” p. 204.

Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution, pp. 156–57.

For background on Rollin, see Georges Bertrin, “Charles Rollin,” in The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 13 (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912), at www.newadvent.org/cathen/13119b.htm (accessed August 2, 2010).

Charles Rollin, “Of Furniture, Dress and Equipage,” in Traité des études (London, 1726), pp. 30, 39.

Ibid., pp. 32–34.

Ibid., pp. 30, 31.