Benjamin Henry Latrobe, United States Capitol, Washington, D.C. Perspective from the Northeast, 1806. Watercolor and ink on paper. 19 1/4" x 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) The inscription reads: “TO THOMAS JEFFERSON Pres. U.S., B.H. LATROBE, 1806.”

Anthony St. John Baker, The White House and Capitol, ca. 1827. Watercolor on paper. 7 5/8" x 11 5/8". (Courtesy, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.)

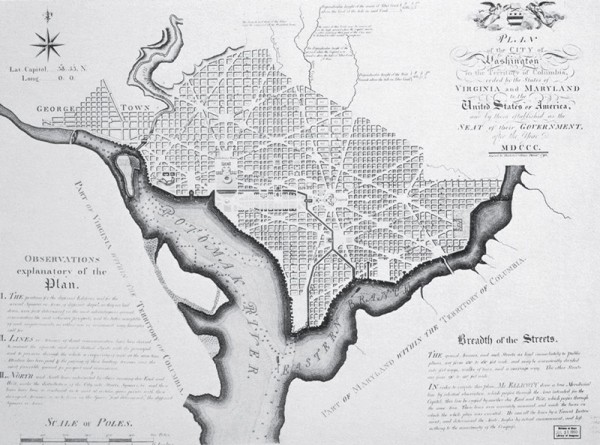

Pierre Charles L’Enfant, Plan of the City of Washington, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1792. Engraving. Image, 8 1/4" x 10 1/4"; sheet, 13 3/4" x 16 15/16". (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

Silhouette of Henry Ingle, probably Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1790–1800. Paper. Diam. 3 1/8". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Washington, D.C.) The frame is original.

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to Henry Ingle with carving attributed to William Hodgson, Richmond, Virginia, 1789. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, walnut, birch, and cherry. H. 99 1/2", W. 44 3/8", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rosette of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the urn-and-flower ornament of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Architectural carving attributed to William Hodgson, Woodlands, Amelia County, Virginia, ca. 1790. (Photo, Katherine Wetzel.) Clotworthy Stephenson furnished the plaster ornaments. The architectural components were fabricated and carved in Richmond and shipped to Amelia County.

112 South Royal Street, Alexandria, Virginia, before 1795. (Photo, Christian Meade.) Joseph Ingle acquired this property in 1795 and maintained a cabinetmaking shop until 1816. His brother Henry worked with him at the site from 1798 to 1801 and possibly earlier.

Candle stand attributed to Henry Ingle, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, or Alexandria, Virginia, 1790–1800, Mahogany. H. 28 1/2", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The label reads: “Mahogany candle-stand, probably made in Philadelphia . . . by H. Ingle or in his shop. . . . came from Mary Pechin, wife of Henry Ingle.”

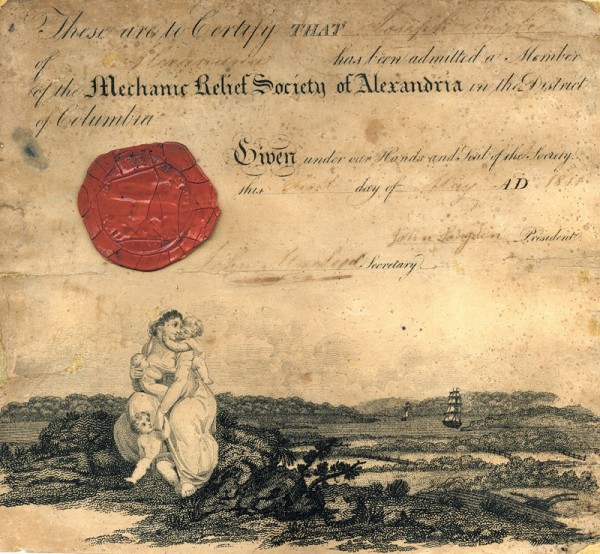

Joseph Ingle’s membership certificate in the Mechanic Relief Society of Alexandria, unknown engraver and printer, Alexandria, Virginia, dated 1811. Copperplate engraving on paper. 8" x 8 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

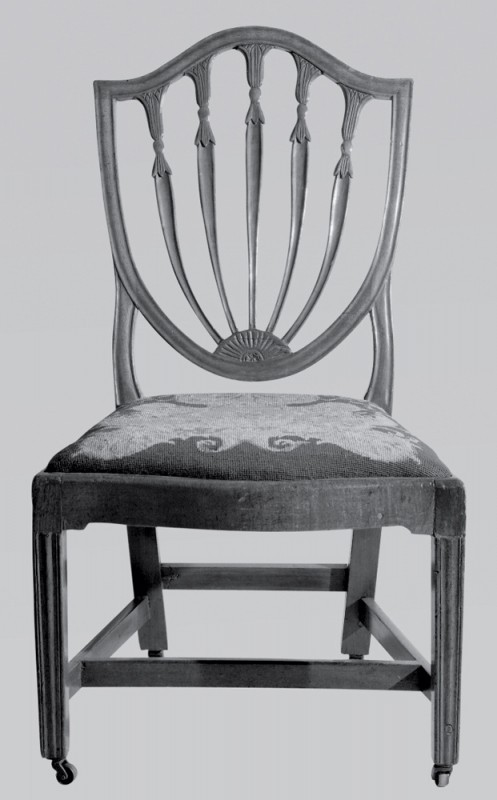

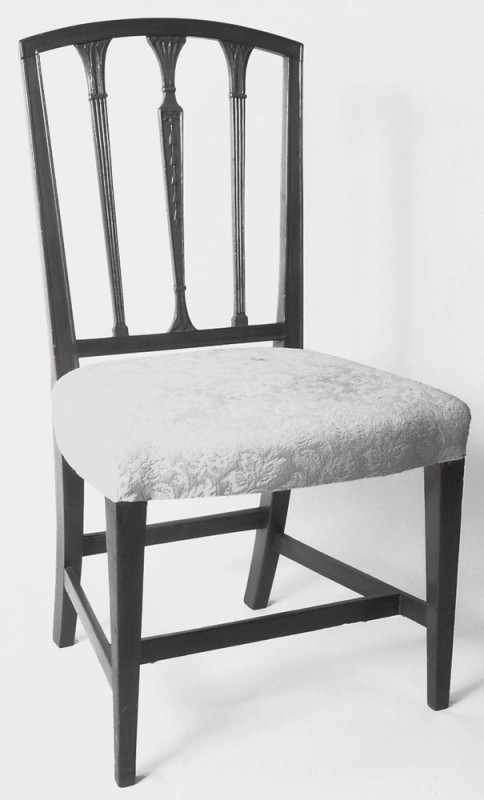

Side chair, Alexandria, Virginia, 1795–1800. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 37 1/2", W. 20", D. 17". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the back of the side chair illustrated in fig. 12.

Side chair, Alexandria, Virginia, 1795–1800. Mahogany with oak. H. 37 1/2", W. 19", D. 17". (Courtesy, Sully Plantation; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

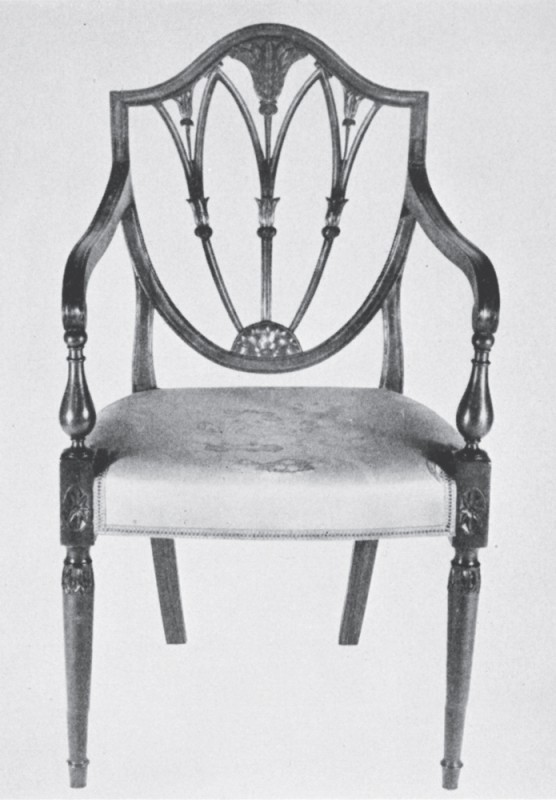

Armchair, Alexandria, Virginia, or Washington, D.C., 1795–1805. Mahogany with oak and tulip poplar. H. 37 1/2", W. 18 5/8", D. 16 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The arms are early additions.

Detail of the carved acanthus leaves on the armchair illustrated in fig. 15.

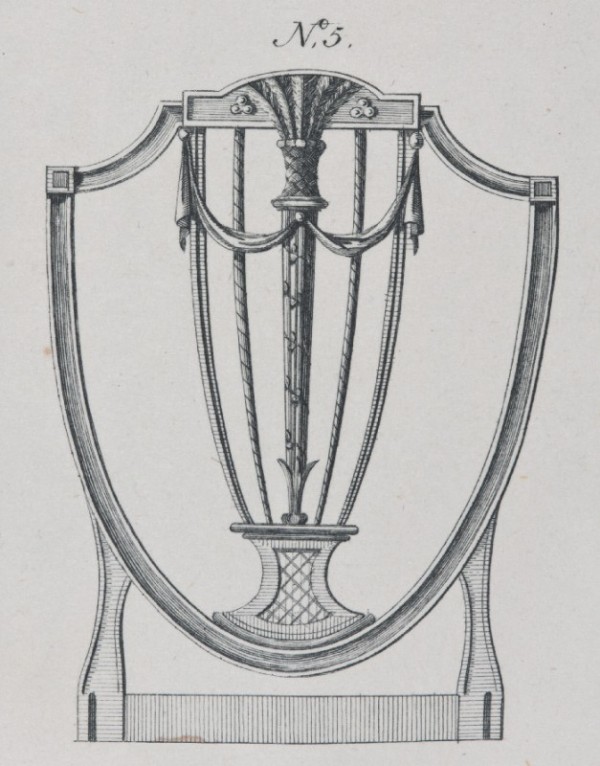

Design for a side chair illustrated on pl. 5 of George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (3rd ed., 1794). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Catafalque, possibly by Henry or Joseph Ingle, Alexandria, Virginia, 1790–1800. Walnut. H. 26 3/4", L. 113 1/2" (with handles), D. 33 3/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union; photo, Dennis McWaters.)

Fragment of a tapered leg with spade foot, possibly Joseph Ingle, Alexandria, Virginia, 1795–1805. Mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Christian Meade.)

Excavated banister from an urn-back chair, possibly Joseph Ingle, Alexandria, Virginia, 1795–1805. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Christian Meade.)

Detail of the carving on the chair banister illustrated in fig. 20.

Side chair, possibly Joseph Ingle, Alexandria, Virginia, 1795–1800. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 37 3/4", W. 21", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Gadsby’s Tavern Museum, City of Alexandria; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Side chair attributed to Henry Ingle, possibly with Isaac Pelton, Washington, D.C., 1801–1802. Mahogany and oak. H. 37 1/2", W. 21", D. 17 1/8”. (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the leg carving on the chair illustrated in fig. 23. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to Henry Ingle, possibly with Isaac Pelton, Washington, D.C., 1801–1802. Mahogany with walnut, cherry, tulip poplar, and mahogany. H. 36 1/2", W. 20 3/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This is the earliest Washington seating form with half-over-the-rail upholstery.

Detail of the acanthus leaf in the back splat of the chair illustrated in fig. 25.

Card table, American, Baltimore, Maryland, attributed to Henry Ingle, 1785–1800. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, tulip wood, oak. H. 29 1/4", W. 30 5/8", D. 15". (Courtesy, The Baltimore Museum of Art: gift of Mrs. Harry B. Dillehunt, Jr., in memory of her husband, BMA 1978.60.1; photo, Mitro Hood.)

Design for a chair back illustrated on pl. 36, of Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (1793). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

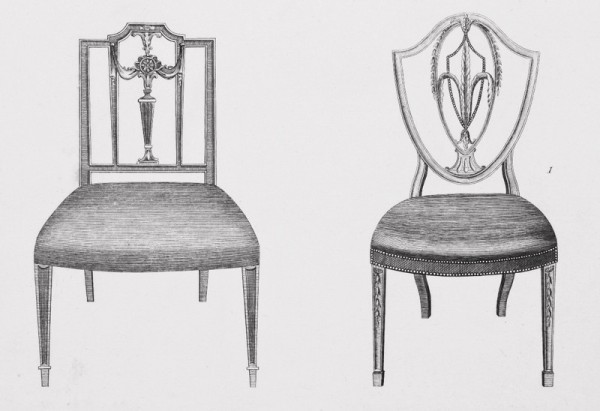

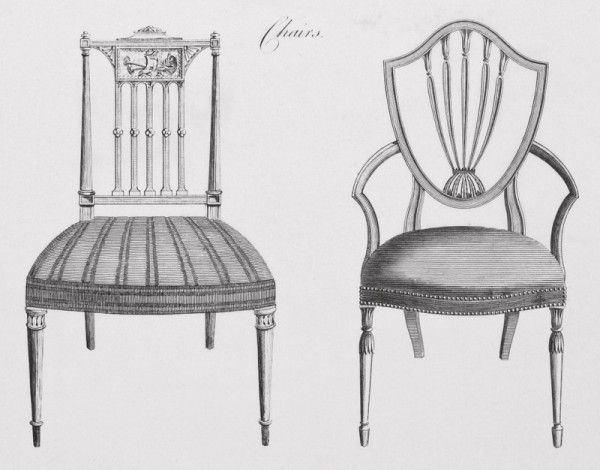

Design for “Chairs” illustrated on pl. 6 of George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (3rd ed., 1794). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The chair on the left was the source for the back of the Harper chairs, and the chair on the right was the source for the half rosette and graduated husks on the Harper chairs and other seating attributed to Henry Ingle.

Side chair attributed to Henry Ingle, Washington, D.C., 1800–1805. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 36 1/2", W. 20", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the back of the chair illustrated in fig. 30.

Side chair attributed to Henry Ingle, Washington, D.C., 1800–1805. Mahogany with oak. H. 37 1/4", W. 20", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Astorino.)

Detail of the back of the chair illustrated in fig. 32.

Side chair, Washington, D.C., 1800–1810. Mahogany with ash. H. 36 1/2", W. 19 3/8", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Armchair, Washington, D.C., ca. 1800. Mahogany. (Baltimore Furniture: The Work of Baltimore and Annapolis Cabinetmakers from 1760 to 1810 [Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1947], fig. 56.)

Sofa attributed to Henry and/or Joseph Ingle, Alexandria, Virginia, or Washington, D.C., 1795–1805. Mahogany and lightwood inlay; secondary woods not recorded. H. 36", W. 79", D. 37 1/4". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

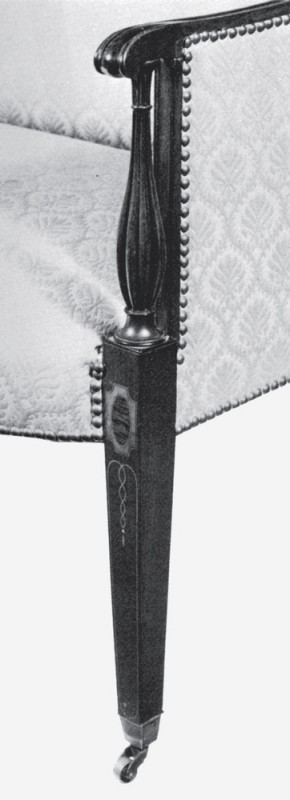

Detail of an arm and leg on the sofa illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sofa, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1795–1805. Mahogany with yellow pine, white oak, and white pine. H. 22 1/2", W. 69". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Carved ornament over the north entrance of the President’s House, attributed to David Cummings, John Davidson, James Dixon, James Dougherty, Henry Edwards, John Hogg, and/or Robert Vincent, Washington D.C., ca. 1797. Carved sandstone. (Courtesy, White House Historical Association.)

Tombstone for Sarah Wren, Christ Church, Alexandria, Virginia, after 1794. Seneca sandstone. H. 31". (Courtesy, Historic Christ Church; photo, Sumpter Priddy and Christian Meade.)

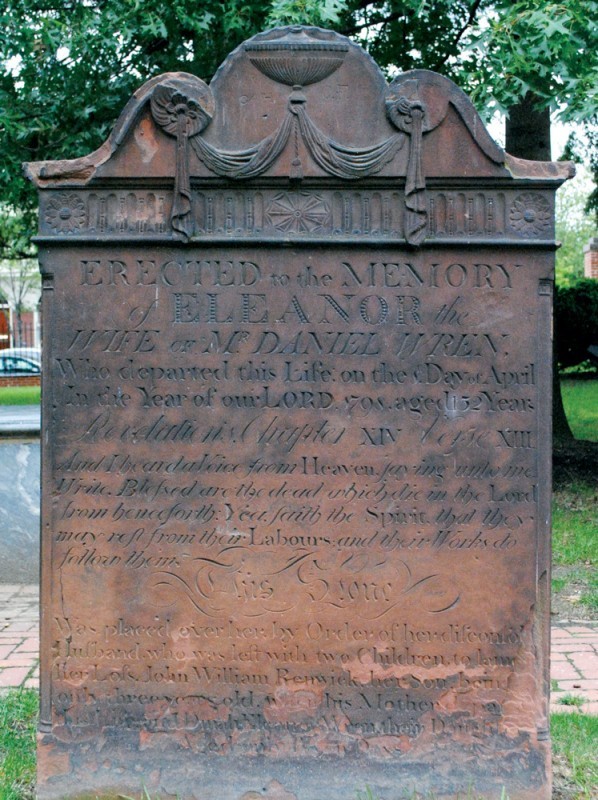

Tombstone for Eleanor Wren, Christ Church, Alexandria, Virginia, after 1798. Seneca sandstone. H. 62 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic Christ Church; photo, Sumpter Priddy and Christian Meade.)

Giuseppe Franzoni after a design by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, capital, U.S. Senate vestibule, 1809. Aquia sandstone. (Courtesy, Architect of the Capitol.)

Giovanni Andrei, capital, White House South Portico, ca. 1815. Aquia sandstone. (Courtesy, White House Historical Association.)

Francesco Iardella after a design by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, capital, U.S. Senate Rotunda, 1816. Aquia sandstone. (Courtesy, Architect of the Capitol.)

Sofa attributed to William Waters or William Worthington, District of Columbia, 1795–1805. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 36 1/2", W. 77 1/2", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Sumpter Priddy.)

Sofa attributed to William Waters or William Worthington, District of Columbia, 1795–1805. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 36 1/2", W. 77 1/2", D. 34". (Private collection; photo, Sumpter Priddy.)

Sofa attributed to William Waters or William Worthington, District of Columbia, 1795–1805. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 36 1/2", W. 77 1/2", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Astorino.) The sofa has its original casters, but they are not shown here.

Detail of the right arm and leg of the sofa illustrated in fig. 47.

William Worthington, Washington, D.C. or Frederick, Maryland, 1820–1825. Oil on canvas. 30" x 25". (Private collection; photo, Philip Beaurline.)

French bedstead attributed to Jacob Desmalter and Co. after a design by Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine, Château de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison, France, 1799–1803. (Courtesy, Réunion des Musées Nationaux; photo, Art Resource, NY.)

French bedstead attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1818–1819. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 61 1/2" (with finials), L. 77", W. 53 1/4". (Courtesy, James Monroe Memorial Foundation.)

Detail of the carved rail on the French bedstead illustrated in fig. 51.

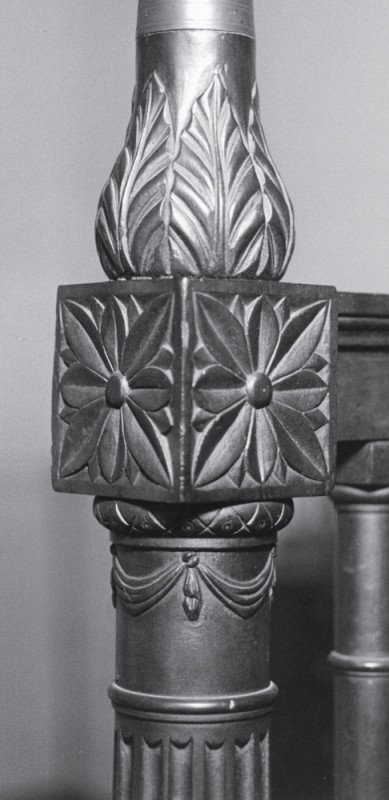

Detail of the carved post on the French bedstead illustrated in fig. 51.

Chimneypiece in a second-floor room in the Bank of Alexandria, 133 North Fairfax, Alexandria, Virginia, 1807. (Courtesy, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; photo, Christian Meade.) The composition ornament is attributed to George Andrews. The President’s House probably had similar chimneypieces.

Detail of the composition ornament on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 54.

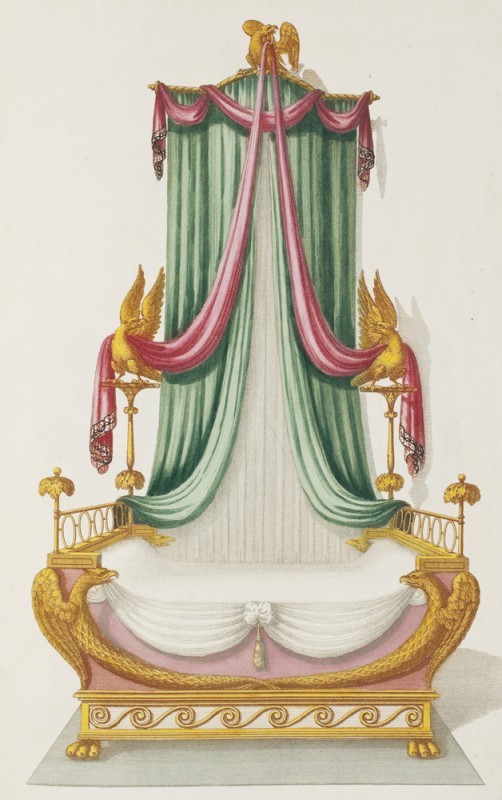

“Canopy Bed” illustrated on pl. 6 of Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (1804). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the plate illustrated in fig. 56. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Keystone, Bank of Alexandria, Alexandria, Virginia, 1807. Aquia sandstone. (Courtesy, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; photo, Christian Meade.)

Giuseppi Valaperta, eagle in the Hall of Statues, U.S. Capitol, 1815. Aquia sandstone. (Courtesy, Architect of the Capitol.)

Armchair attributed to William King Jr., Georgetown, D.C., 1818. Mahogany with ash and maple. H. 40 7/8", W. 25 1/2", D. 25 1/8". (Courtesy, Collection of Ash Lawn Highland; photo, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York.)

Sofa attributed to William King Jr., Georgetown, D.C., 1815–1825. Mahogany with walnut and yellow pine; brass casters. H. 32 7/8", W. 89 1/4", D. 25 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Side chair attributed to William King Jr., Georgetown, D.C., 1815–1825. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 32 5/8", W. 17 7/8", D. 16". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Saber legs are rare on Washington seating.

Side chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1805–1815. Mahogany with ash and yellow pine. H. 37 1/2," W. 18 1/2", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Astorino.)

Detail of the carved crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 63.

Side chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1805–1815. Mahogany with ash, yellow pine, cherry, and mahogany. H. 36 1/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Astorino.)

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 65.

Side chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1805–1815. Mahogany with yellow pine, ash, cherry, and mahogany. H. 33", W. 18 1/2", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Astorino.) This chair is from a set that descended in the family of Dr. Reverdy Ghiselin (1765–1823) and his wife, Margaret (1783–1850), who lived near Nottingham in Prince George's County, Maryland.

Designs for chairs illustrated on pl. 9 of George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1794). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1805–1815. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with oak. H. 35 3/4", W. 19 3/4", D. 16 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This chair is one of a pair.

Sofa attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1800–1810. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with mahogany, white pine, and chestnut. H. 38 1/4", W. 81", D. 30 1/2". (Courtesy, James Madison’s Montpelier.)

Sofa attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1800–1810. Mahogany, satinwood, rosewood veneer and lightwood and darkwood inlays. H. 38 1/4", W. 82 1/2", D. 30 1/2". (American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, 10 vols. [Washington, D.C.: Highland House, 1982], 2: 1334.)

Detail of the inlay and carving on the sofa illustrated in fig. 71.

Sofa attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1800–1810. Mahogany and satinwood veneers with mahogany, white pine, and chestnut. H. 38 1/4", W. 81", D. 30 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Marc Anderson.)

A view of the back of the sofa illustrated in fig. 73. (Private collection; photo, Marc Anderson.)

Detail of the inlaid and carved leg on the sofa illustrated in fig. 73.

Sofa attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1810–1811. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 39", W. 77 7/8", D. 25 5/8". (Courtesy, Pearre-Peter family; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carved patera on the right front leg of the sofa illustrated in fig. 76. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carved central panel in the crest of the sofa illustrated in fig. 76. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carved side panel in the crest of the sofa illustrated in fig. 76. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the double drapery carved on the Eleanor Wren tombstone illustrated in fig. 41.

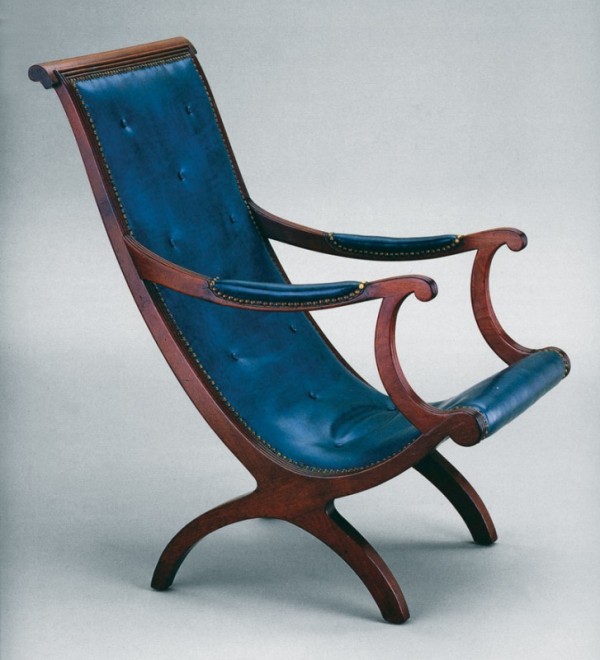

Campeachy chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1815–1820. Mahogany with tulip popular and yellow pine. H. 37 1/2", W. 21", D. 31 1/2". (Courtesy, Peter Patout; photo, Ellen McDermott, New York.)

Detail of the carved crest rail on the chair illustrated in fig. 81.

Detail of the carved rosette on the chair illustrated in fig. 81.

Detail of a rosette on Sarah Wren’s tombstone illustrated in fig. 40.

Campeachy chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1810–1820. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 40 1/2", W. 21 5/8", D. 29 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) Worthington's Campeachy chairs have a bowed brace that is either dovetailed or mortised into the inner edges of the back frame.

Campeachy chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1810–1820. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 38 1/2", W. 24", D. 33 1/8". (Courtesy, Collection of Mrs. George M. Kaufman.)

Side chair, possibly Benjamin Belt or Gustavus Beall, Washington, D.C., 1814–1817. Mahogany with mahogany and white pine. H. 33", W. 19", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, New Hampshire Historical Society.)

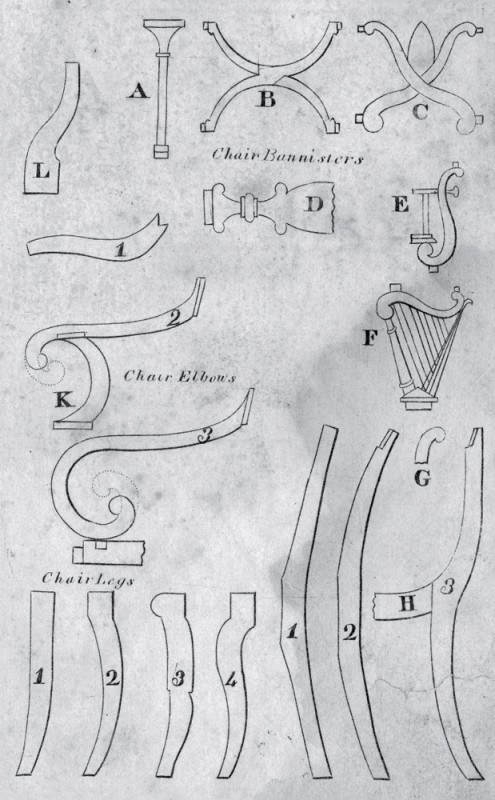

Designs for chair components on pl. 6 in New York Society of Cabinet Makers, The New York Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work, 1816. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Gustavus Beall, table, Georgetown, D.C., ca. 1815. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with oak and white pine. H. 28 1/2", W. 42 3/8" (open), D. 31 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Armchair, probably Washington, D.C., 1815–1820. Maple and ash. H. 33 1/16", W. 23 5/8", D. 18". (Courtesy, James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Maple was favored for American painted chairs in the 1810–1840 period. Unlike most European antique maple furniture from Europe, the Monroe chairs are not riddled with insect damage.

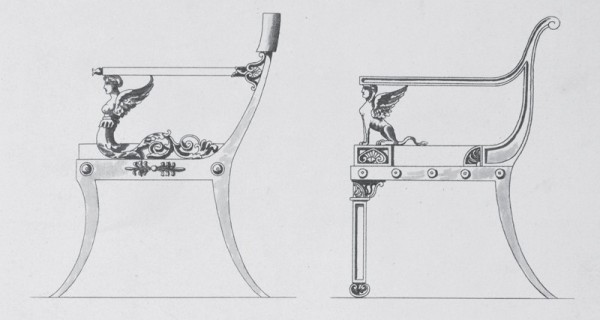

Designs for “Drawing Room Chairs in Profile” illustrated on pl. 55 of George Smith’s Designs for Household Furniture (1808). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of a caryatid on the armchair illustrated in fig. 90. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

"Klismos" Chair, American, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; decorator: John P. Fondé 1820-1825. Ash, pine, gilt, wool upholstery, brass. H. 31 3/4", W. 18", D. 22". (Courtesy, The Baltimore Museum of Art: purchased in Honor of James Archer Abbott, Curator of Decorative Arts, 1997-2004, by the Friends of the American Wing, and with additional funds contributed by Frederica K. and William Saxon, Jr., Ruth Ann Adams, Mr. and Mrs. Robert Bentley Adams, Dr. and Mrs. Aristides C. Alevizatos, Mark B. Letzer, Hugh and Joy McCormick, Charles and Mary Meyer, David A. Mozes, Dr. and Mrs. Thomas R. O'Rourk, and Bodil Ottesen, BMA 2003-122; photo, Mitro Hood.)

In 1790 the United States Congress voted to move the nation’s capital from Philadelphia to a location nearer the center of the country’s rapidly expanding population. President George Washington suggested a site just below the falls of the Potomac River, perched along a stretch of land between the booming towns of Georgetown, Maryland, and Alexandria, Virginia. Shortly thereafter, Congress hired French engineer Pierre L’Enfant to prepare a plan for the new “District of Columbia” and sponsored a national competition seeking designs for two buildings that would dominate the landscape. West Indian native Dr. William Thornton won the prize for the United States Capitol (fig. 1), and Irish-born architect James Hoban won the prize for the President’s House (fig. 2). Artisans flooded into the region hoping to secure work, while some of America’s most vocal proponents for the arts—including Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson—envisioned ways to furnish the city’s new structures in a manner worthy of the young country’s high aspirations. The three decades that followed witnessed a period of intensive government patronage for the arts. This article will discuss a number of talented artisans who influenced furniture design in the city, suggest unique local developments that shaped the evolution of their trade, establish a chronology of style as reflected in their products, and explore the diverse forms and ornaments of a previously unrecognized school of furniture that evolved along the banks of the Potomac.

America’s new capital city contained three separate jurisdictions, each of which contributed to the furniture story. L’Enfant laid out the plan as a ten-mile square, set on a diagonal that spanned the Potomac River as it ran from northwest to southeast (fig. 3). The bustling community of Georgetown, incorporated in 1751, stretched along the river’s hilly northern bank, just above the center of the square. Its economy, initially fueled by tobacco, became increasingly diverse in the intervening years, with mills spreading inland along Rock Creek, which emptied into the Potomac on the south end of town. Piers along Bridge Street attracted ships from Europe, South America, and the Caribbean and helped support a prosperous community of merchants and artisans.

Members of several prominent Maryland and Virginia families moved to Georgetown during the late eighteenth century. Among the most influential were the Carrolls, Bealls, Belts, Masons, and Tayloes. Joining them were powerful émigrés like merchant and Georgetown mayor Robert Peter (1726–1806), who arrived from Scotland in 1745 and established a lineage that was influential for decades. These families helped shape the economic, political, and artistic development of the region. Estimates of Georgetown’s population vary slightly according to source, but in 1800, the municipality (incorporated in 1789) had approximately 5,120 inhabitants, of which 1,449 were slaves, and 277, free blacks.[1]

Seven miles south of Georgetown, near the southern tip of the district’s ten-mile square, stood Alexandria, Virginia. Founded in 1749 on the south bank of the Potomac, it, too, boasted an active waterfront and a strong economy linked initially to tobacco. Merchant John Carlyle came from the north of England during the 1740s and—seeing opportunity—built warehouses on the waterfront. He then helped plan the town and constructed its first mansion with elaborately carved interiors. Some of northern Virginia’s most powerful planters built or purchased homes in Alexandria, including members of the Lee, Custis, and Washington families. Their wealth supported a sizable community of merchants and tradesmen, many from Scotland and England’s West Country ports. In 1800 Alexandria had a population of about 4,971, of which 875 were enslaved and 369 were free African Americans.[2]

Congress established the third jurisdiction—“Washington, the District of Columbia”—in 1790, with the intention of locating the seat of government there a decade later. Washington, D.C., was built from the ground up in the rural landscape along the river’s north bank, on a parcel of land that stretched southward from Rock Creek to the Potomac River’s Eastern Branch, also known as the Anacostia River. L’Enfant envisioned the city in the manner of Europe’s grandest, with a series of diagonal boulevards that radiated out from the President’s House and the Capitol, thereby providing both elegant vistas and convenient access to nearby rivers and roadways. Despite his vision, Washington’s major buildings and infrastructure were woefully unfinished when Congress first convened there in a temporary structure on June 11, 1800. Over the next two decades, development would be indelibly shaped by national politics, by rivalries between Maryland and Virginia, and by the region’s largest landowners.[3]

Members of the Carroll family were among the most prominent landowners. Daniel Carroll (1755–1849) owned Duddington, which encompassed several thousand acres atop Jenkins Hill—now known as Capitol Hill—and from there stretched southeast to the Anacostia River. His cousin Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who was the wealthiest man in Maryland, lived in Annapolis, but two of the latter’s children had ties to Washington. Daniel and Charles’s cousin, Father John Carroll (1735–1815), founded Georgetown University and became the Catholic Church’s first American archbishop. Modern scholarship emphasizes the Carroll family’s ties to Annapolis and Baltimore, but their early history was also linked strongly to Georgetown.[4]

Known during the period as the Federal City or Washington City, Washington, D.C., had 3,210 free white inhabitants in 1800. When combined with Alexandria and Georgetown, the District of Columbia’s total population was just over 13,300. That number represented less than half the population of Baltimore, where a flourishing community of artisans created some of the Chesapeake region’s finest neoclassical furnishings. Yet the special circumstances that surrounded Congress’s decision to build a new Federal City and to fund it generously, if sporadically, created unprecedented opportunities for government patronage of architecture and the arts and attracted talented artisans from across America.[5]

The District of Columbia’s artistic development received tremendous impetus with Thomas Jefferson’s election to the presidency in 1800. His fascination and experience with architecture, which was reflected in a lifetime spent refining his home at Monticello and his role in designing Virginia’s Capitol in Richmond, had familiarized him with the subtle skills of design and the complexities of building. His service as America’s Minister Plenipotentiary to France from 1784 to 1789 had introduced him to some of Europe’s finest architecture, strengthened his understanding of ancient classical detail, and reinforced his commitment to the inseparability of architecture and the fine arts.

Jefferson’s experiences in France and his brief sojourns in England and Italy placed him in a unique position among Americans dedicated to the arts. While abroad, he developed personal relationships with some of Europe’s finest artists and artisans. These included Jean-Antoine Houdon, who came to America in the late 1780s to sculpt America’s Revolutionary heroes and, during that visit, produced studies for his renowned full-length sculpture of George Washington, destined for the Rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol. More important to the story at hand, Jefferson inspired a wave of talented artisans to migrate to the region. These craftsmen shaped the Federal City and its artistic legacy in a way that would be felt for decades.[6]

Henry and Joseph Ingle and the Influence of Philadelphia Furniture Styles

During the summer session of the Second Continental Congress in 1783, Jefferson met Henry Ingle (1763–1822) (fig. 4), an apprentice of Philadelphia cabinetmaker and house joiner John Webb. When he completed his term the following year, Ingle traveled to Virginia, where he first settled near Jefferson’s home in Albemarle County. Two years later, Ingle moved to Richmond, where he worked with a group of talented and well-connected artisans who were entrusted with erecting Jefferson’s revolutionary temple design for the Virginia State Capitol, in its turn the largest building project in America during the 1780s.[7]

Although Ingle entered into a brief partnership with Philadelphia cabinetmaker Elijah Speakman, much of his Richmond career was probably spent working under the direction of British-born joiner Clotworthy Stephenson (d. 1819), who was largely responsible for fabricating the interior woodwork for the Virginia Capitol. Both men subsequently moved to Washington to help build the United States Capitol, the largest structure under construction in America during the 1790s. Stephenson, who was the senior of the two, served as Grand Marshall for the ceremony that laid the cornerstone in 1793 and worked at the Capitol intermittently over the next decade.[8]

At the Virginia Capitol, Ingle also worked closely with carver William Hodgson (1750–1806), whose surviving work includes the Ionic capitals of the pilasters in the Old Senate Chamber and the leaf-carved trusses that support pediments beneath the Capitol dome. Like most professional carvers, Hodgson offered his services to both joiners and cabinetmakers. All of the rosettes and vase-and-flower ornaments on Ingle’s finest case pieces originated in Hodgson’s shop. The latter’s distinctive working style is manifest in the carving on a desk-and-bookcase made for Dabney Minor, an Orange County joiner who also worked at the Virginia Capitol (figs. 5-7). Hodgson’s acanthus leaves have a pronounced central vein, a hollow in the middle of each frond, and tips that overlap one another. Other than differences in scale, there is little separating his architectural carving and furniture work. For example, the husks and rosettes Hodgson furnished for the dining room chimneypiece in Woodlands, the home of Amelia County, Virginia, planter Stephen Cocke (fig. 8), are strikingly similar to those on furniture made by Henry Ingle during his Washington career.[9]

Ingle left Virginia and returned to Philadelphia in 1791. Three years later, he joined cabinetmaker Jacob Schreiner in a cabinetmaking partnership and a hardware business. Family tradition maintains that Henry worked with his older brother Joseph (1763–1816) in the latter’s shop at 273 High Street. Thomas Jefferson, who lived next door while serving as secretary of state in George Washington’s administration, purchased furniture from both men during that term, and President Washington hired Ingle for “sundry jobs” at the President’s House in 1790.[10]

In the 1790s Philadelphia was abuzz with news of the new Federal City, and, like many Philadelphia artisans, the Ingle brothers must have envisioned the great opportunity that it presented. Joseph moved to Alexandria by 1793, when he advertised locally for an apprentice. Two years later, he acquired a building at 112 South Royal Street, between King and Prince Streets, and set up a cabinetmaking shop (fig. 9). In May 1795 Henry Ingle and Jacob Schreiner announced that they were “declining the Cabinet making business” and offered their inventory for sale. In October of the following year, they dissolved their hardware business: “The Partnership of Schreiner and Ingle, Ironmongers, will by mutual consent expire on the twentieth day of this month.”[11]

Whether Henry Ingle worked in Alexandria intermittently over the next several years remains uncertain, but he did not announce his departure from Philadelphia until November 1798. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Alexandria, where he temporarily joined his brother Joseph in the cabinetmaking and undertaking business. In 1799 Henry establishing a separate hardware business half a block away “at the North-west Corner of King and Royal Streets.” There he offered a “General Assortment of IRONMONGERY, CUTLERY AND BRASSWARE” as well as “an Assortment of brushes, and a variety of brass wares for buildings and furniture.”[12]

A candle stand that dates from the mid-1790s bears a mid-twentieth-century label identifying it as a product of Henry Ingle’s shop (fig. 10). Like the desk-and-bookcases that he made in Richmond (fig. 5), the stand resembles contemporaneous Philadelphia work. Parallels are apparent in the shape of the legs and feet and the turnings of the pillar and birdcage. Along with a copy of Joseph Ingle’s certificate of membership in the Mechanic Relief Society of Alexandria (fig. 11), the stand remained in the family of Henry and his wife, Mary (Pechin), until the 1970s. [13]

Three different sets of neoclassical chairs descended in families that lived within blocks of Henry and Joseph Ingle’s shop (figs. 12, 14, 15). Two other sets have identical backs but lack an early provenance. In light of the chairs’ Philadelphia-inspired design and the Ingle brothers’ associations with the families who owned them, all this seating can be attributed to the Ingle shops with relative certainty.[14]

Alexandria Mayor Dennis Ramsay (1756–1810), a kinsman of George Washington and a pallbearer at his funeral, owned the set represented by the chair illustrated in figures 12 and 13. Not surprisingly, the Ramsay home originally stood at the northeast corner of King and Fairfax Streets, two and a half blocks from the brothers’ shop, and it is logical that he would have owned an Ingle chair. The chair came down in the family until 1960, when descendants donated it to the Smithsonian Institution.[15]

Richard Bland Lee (1761–1827) and his wife, Elizabeth Collins Lee (1768–1858), purchased a similar set of chairs for Sully, which was built in Fairfax County, Virginia, in 1799 (fig. 14). Lee had numerous opportunities to engage the Ingle brothers. He probably met them in Philadelphia through his friend Thomas Jefferson, while serving in Congress between 1789 and 1795. Richard’s brother Harry owned property on Oronoco Street, just five blocks from the Ingles’ Alexandria shops, and members of the Lee family visited Alexandria frequently for business and pleasure. In 1816 Richard received a two-year appointment from James Madison as “Claims Commissioner” and was responsible for compensating individuals and businesses for property destroyed or damaged in Washington during the War of 1812. In that position Lee was in constant contact with Henry Ingle, who oversaw construction of the Brick Capitol that temporarily housed Congress after the British burned William Thornton’s original structure.[16]

The original owner of an armchair from a third set is unknown, but it has a history of descent in the Green family of Alexandria and was probably owned in the early nineteenth century by cabinetmaker William Green (1774–1824) (figs. 15, 16). A native of Sheffield, England, William arrived in Alexandria in 1817. Shortly thereafter, he may have begun working as a journeyman for cabinetmaker John Muir (1770–1815). Muir’s business was located at 110 South Royal, next door to the shop where Joseph Ingle practiced his trade from 1795 to 1816.[17]

Green began working independently at 110 South Royal by 1820, when he placed an advertisement thanking local clients for their patronage. Three years later, his son James (b. 1801) joined him in the business, and the following year the younger Green married John Muir’s daughter Jane (1803–1880). Although the means by which the chair entered the Green family remain unknown, the object’s early leg repairs and arm additions suggest that it may have been taken to William’s shop for repair.[18]

The three sets of chairs with Alexandria histories (see figs. 12, 14, 15) have splats based on plate 5 of George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788) (fig. 17). Although the carving on the chairs shares details with earlier work attributed William Hodgson, there is no documentary evidence that he moved to Alexandria and continued to work for Ingle. If Hodgson did not carve these chairs, his work certainly appears to have influenced the design of the acanthus leaves at the top of the splats. Ingle commissioned work from Hodgson during the 1780s and might well have taken some of the carver’s working drawings when he left Virginia in 1791. At the very least, it is hard to imagine that the men did not influence each other.[19]

Only a small group of objects associated with the Ingles’ early Alexandria period survive, but it is clear that they offered a range of options for certain forms. Patrons could obtain chairs with plain or molded legs, seat frames with straight or serpentine front rails, and over-the-rail upholstery or slip seats. For seating with over-the-rail upholstery, the Ingles reinforced the frames with diagonal braces, typically made of poplar and half-dovetailed into the tops of the rails. The braces are positioned close to the leg and usually at a slightly oblique angle. Most of the seat rails on Ingles’ chairs are oak, but sporadic use of ash and mahogany has been recorded. The joints on their chairs were secured with glue alone, and the pins occasionally found on some examples represent later refurbishment or repair.[20]

A catafalque illustrated in figure 18 may be associated with one of Joseph and Henry Ingle’s most significant commissions, although evidence is insufficient to support more than a tentative attribution. In 1799 George Washington’s estate hired them to provide a casket and oversee the former president’s funeral. The brothers charged $88 for a “mahogany coffin and silver plate engraved, furnished with lace,” provided the catafalque on which the coffin rested during several days of ceremonies, and supplied a horse-drawn hearse to convey the body to Alexandria for a Masonic ceremony before returning it to Mount Vernon for burial. Although unverified oral tradition is all that links the catafalque illustrated in figure 18 to George Washington’s funeral, that object’s pierced brackets and stretchers are consistent with the Philadelphia style in which the brothers worked, and its molded legs are similar to those on some of the aforementioned Alexandria chairs.[21]

In the June 19, 1800, issue of the Times and the District of Columbia Advertiser, Henry Ingle announced his pending move into Washington City, and the following year he purchased a shop on New Jersey Avenue when he entered into a one-year partnership with chair maker and cabinetmaker Enoch Pelton (1770–1829). His new neighborhood was among the most active in the district, with international artisans working at the unfinished Capitol site, legislators engaged in governing, and businessmen trying to capitalize on the benefits of the moment. Though records are sparse, it is clear that Ingle worked at the Capitol intermittently over the years, perhaps with Clotworthy Stephenson, who was active at that site by 1797. In 1808 Ingle was among a group of Capitol artisans who signed a petition to Henry Latrobe, expressing their dedication to the project, despite erratic government funding. When he retired six years later, Ingle was still working from his shop at New Jersey Avenue.[22]

Joseph remained in Alexandria, but records pertaining to his trade are scant. He took an apprentice in 1805 and retired in 1816, just two years before his death. Fragments of a leg and chair banister recovered from a privy behind Joseph’s shop appear to date circa 1800, thus warranting consideration as his work. Both artifacts came from a stratum of ash, thought to have resulted from an 1827 fire that began in James Green’s shop on the adjoining property at 110 South Royal. The fire spread eastward toward the river causing great destruction, yet it spared the Ingle property.[23]

The excavated leg has a spade foot that is a separate, one-piece component (fig. 19). Most spade feet are composed of four pieces that are horizontally laminated to the sides of the leg, a procedure that is far more efficient in terms of labor and materials. This difference in construction suggests that the leg is not a discarded fragment from a piece of furniture but rather a showroom prop intended for demonstrating two leg options—one plain and the other terminating in a spade foot. In contrast, the banister appears to have been part of an urn-back chair (fig. 20). The leaves are carved in low relief and have paired shading cuts that diverge from a convex central vein (fig. 21). Although no chair with identical banisters is known, an example originally owned by George Washington’s gardener Johan Ehlers suggests that urn-back variants with similar details were popular in Alexandria and the District of Columbia during this period (fig. 22). The back of the Ehlers chair was inspired by the design for a “Bar Back Sofa” in Hepplewhite’s Guide, a publication frequently consulted by local furniture makers.[24]

Although separating the work of the Ingle brothers is somewhat problematic, chairs from a set originally owned by William Hammond Dorsey (1764–1819) of Washington and Baltimore offer clues for identifying Henry’s work (fig. 23). Although traditionally attributed to Baltimore, the Dorsey chairs have carved urn backs that are identical to those on the Ramsay, Lee, and Green examples (figs. 12, 14, 15). Dorsey lived in Georgetown before moving to Brookeville in 1810 and almost certainly acquired the chairs shortly after completing the Oaks (now known as Dumbarton Oaks) in 1801. During the period when Dorsey would have commissioned his chairs, Henry Ingle was living above and working from his shop at New Jersey Avenue, a location much closer to the Oaks than Joseph’s shop. Dorsey and Henry Ingle also had numerous opportunities to connect through the city’s busy social network and also through their shared charitable pursuits—Dorsey was Judge of the Orphan Court for Washington City from 1801 to 1805, and Ingle served as a Trustee for the Poor from 1805 to 1806.[25]

The Dorsey chairs are distinguished by having elaborately carved legs (fig. 24). Each front face has a half-flower at the top and a chain of graduated husks that ends just above an astragal-shaped element at the bottom. William Hodgson used tripartite husks with teardrop-shaped stems during the 1780s (fig. 8), thus it is only logical that Henry Ingle incorporated similar designs in his later furniture work. As the Dorsey chairs suggest, Ingle continued to work in the Philadelphia tradition, just as he had in Alexandria, while adapting to the demands of wealthier Washingtonians.[26]

The carving on the Dorsey chairs provides compelling evidence that a larger group of ornate seating furniture was made in Washington. A set of chairs (figs. 25, 26) and at least one card table (fig. 27) that descended in the Harper family of Olney, Montgomery County, Maryland, were clearly carved by the same hand. Stylistically, the chairs are the most fully developed examples from the Washington school. Their back design was derived from plate 36 in Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (fig. 28) and their front legs from plate 2 in Hepplewhite’s Guide. The design of the Harper chairs differs significantly from that of other seating attributed to Henry Ingle (see figs. 12, 14, 15, 23); however, all these objects have stiles that are shaped and molded in a similar manner and rear legs with virtually identical splay. The acanthus leaves at the base of the Harper chair backs have a pronounced central vein, hollow fronds, and overlapping tips that match those in the large clusters below the crests of the Ramsay, Lee, Green, and Dorsey chairs (figs. 12, 14, 15, 23). On both models, the large central acanthus is flanked on each side by a partial acanthus having three hollow channels that flow upward at the edge of the composition. Similarities also exist between the husks on the center banister of the Harper chairs (fig. 26) and legs of the Dorsey chairs (fig. 24). Despite differences in design, the execution is identical. This is most apparent in the outlining, modeling, and shading of the leaves and modeling of the teardrop-shaped stems.[27]

Previous scholars have asserted that the Harper chairs were originally “owned by Charles Carroll of Carrollton,” but they most likely came to his residence when his daughter Katherine “Kitty” Carroll Harper (1778–1861) moved in with him following the death of her husband, Robert Goodloe Harper (1765–1825). The set descended from Mrs. Harper to her great-granddaughter Dorothea Harper Pennington (1896–1995), who sold them to collector Louis Guerineau Myers. The assumption that Charles Carroll commissioned the set has obscured its origin and subsequent history. During the period when these chairs were made, Carroll was focused on helping his children build and furnish new homes rather than personal construction or refurbishment projects.[28]

In 1799 Katherine Carroll met attorney Robert Harper, a United States congressman from South Carolina’s 96th district. The following year he moved temporarily to Baltimore to court her and curry favor with her father, who was skeptical of their relationship. During Harper’s term, which lasted from 1797 to 1801, he served as chairman of the House of Representative’s Ways and Means Committee. In that position he oversaw legislation that raised money for the government—including funds for construction of the Capitol, President’s House, and other buildings for the new Federal City. In Washington, Harper interacted with men involved in those Herculean projects, including Henry Ingle. As the son of a cabinetmaker, Harper would have probably appreciated Ingle’s skill and political savvy and felt comfortable dealing with him.[29]

Harper succeeded in winning over Charles Carroll, for he married Katherine Carroll on May 7, 1801, and soon thereafter the couple settled in Montgomery County, Maryland. Over the next thirty years, Charles Carroll gave them at least $343,957, which enabled them to build a home and acquire furnishings like the set of side chairs (fig. 25) and the card table (fig. 27). In the final analysis, these objects fit neatly into the chronology of seating furniture associated with Henry Ingle, Harper’s life in Washington, D.C., and his association with the Carroll family.[30]

Although the Harper chairs are the finest urn-back examples attributed to Ingle, his shop produced seating with more elaborate carving, including two closely related sets of chairs with backs derived from plate 6 in Hepplewhite’s Guide (fig. 29). Captain John Singleton of Sumter, South Carolina, reputedly owned the set represented by the chair illustrated in figures 30 and 31. The sculptural ribbons and drapery, bold central rosette, naturalistic acanthus, and husks with teardrop stems recall William Hodgson’s carving for Woodlands (fig. 8) and case furniture made by Ingle in Richmond (figs. 5-7) as well as Ingle’s Alexandria chairs (figs. 12, 14, 15).[31]

One of the most common chair designs associated with Henry Ingle has a simpler back with a single carved banister in the middle (fig. 32). The banister has his characteristic half rosette and festoon of graduated husks (fig. 33). Three variations of this chair design are known; all have over-the-rail upholstery and molded legs but differ in the shape of their seats, leg treatment, and stile and banister moldings.[32]

A related set of twelve chairs has a nineteenth-century history of use at the President’s House (fig. 34). Representing a simplified variant of the preceding design (fig. 32), the chairs in this set have thinner stock, arched crests, and carving by a less skilled hand. Although clearly not products of Henry Ingle’s shop, these objects are characteristic of Washington, D.C., seating from the first decade of the nineteenth century and reflect the growing appeal of this popular regional design. Other chairs from this secondary shop are known; one model is identical to the example illustrated in figure 34, with the exception of having a serpentine crest. As was the case with chairs used in the President’s House, seating from Ingle’s shop influenced most versions of this particular design.[33]

An armchair illustrated in Baltimore Furniture: The Work of Baltimore and Annapolis Cabinetmakers from 1760 to 1810 shows how Ingle and other Washington chair makers were updating their products by the beginning of the nineteenth century (fig. 35). The turned arm supports and legs are the most stylistically advanced features. The latter are decorated with fashionable waterleaves that radiate from the center of oval medallions and surround the shank of each leg below its juncture to the seat rail.[34]

The legs and arm supports of this armchair link it to other objects from Ingle shops, including a neoclassical sofa that descended in the Tyler and Belt families of Virginia and Maryland (fig. 36). Like many objects associated with the Ingle brothers, the sofa is a derivation of a Philadelphia prototype. Examples from that city are typically rather small in scale and feature gently swept crests and front legs that transition into baluster-shaped arm supports (fig. 37). The Tyler-Belt sofa shares these details but also has attributes associated with Washington production. In contrast to Philadelphia sofas, which usually have four legs in front and three in the rear (fig. 38), Washington examples typically have four legs at the front and back. Other Washington sofas share the oval medallions on the outer front legs and arms that extend past their supports, ending with a pronounced downward scroll.[35]

The Tyler-Belt sofa has structural details that later became standard on Washington work. Its seat frame is reinforced with two front-to-rear braces. The braces are dovetailed into the tops of the front and rear seat rails and aligned with the middle legs. Screw holes on the inner faces of the legs and undersides of the braces document the attachment of wooden brackets like those on other sofas in this group. This structural approach contrasts with work from Baltimore and other urban centers to the north, where sofas either lack front-to-rear braces or have braces centered between the legs rather than aligned with them.

Documentary evidence for Henry Ingle’s cabinetwork is scarce before 1815, as it is for most Washington artisans associated with the Capitol and President’s House. Treasury accounts record payments to him but rarely describe his work. Moreover, destruction of the city’s most prominent buildings by the British in 1814 obliterated much of the documentary and physical evidence of his and other contemporary tradesmen’s work.

In 1813 two young cabinetmakers, Charles Belt and John D. Hill, announced that they were moving into the building on Capitol Hill “lately occupied as a Cabinet-making shop by Mr. Henry Ingle.” By that date, Ingle’s interests and business associations had gravitated to the civic and investment arena. His political career began with his election to the city council in 1806 and was propelled by subsequent appointments to various commissions. Ingle’s political clout and financial acumen allowed him to participate in partnerships with some of the city’s most successful businessmen. Able to envision Washington’s growing needs, he worked closely with Daniel Carroll of Duddington in several building ventures and with George Blagden (1769–1828) to establish a subscription burial ground that soon gained government support and became the Congressional Cemetery. After Britain invaded and burned Washington, Ingle and his associates formed a public stock company to raise funds and erect a temporary shelter where Congress could meet. The company’s Brick Capitol housed the Senate and House of Representatives for four years, during which time Thornton’s original was reconstructed. The venture not only brought Henry Ingle increasing prominence but also signaled that his career as an artisan had ended and his role as city father had effectively come into its own.[36]

Stonecarvers and the Introduction of European Neoclassicism

Immigrant stonecarvers had a profound impact on the development of neoclassical style in Washington architecture and furniture. This influence began in 1792, when Robert Adam’s Scottish-born protégé Collen Williamson was appointed overseer of masons at the President’s House, and expanded the following year with the arrival of seven highly skilled stonecutters culled from his former colleagues at Masonic Lodge 8 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Shortly thereafter George Blagden—a native of Yorkshire, England—left the President’s House workforce to oversee all the masons working at the Capitol. For the most demanding work, Blagden recruited a significant force of British workmen.[37]

The stonemasons who built the President’s House and Capitol used buff-colored sandstone quarried from the banks of Aquia Creek, forty miles south of Washington. Stonecutters with basic masonry skills cut the stone into precise, rectilinear blocks, so they could be laid with flush joints. Using chisels, files, scrapers, and abrasives, a second group of more accomplished workers fabricated architectural details and moldings in emulation of those of ancient Rome.

The Scottish masons described as “stone-carvers” at the President’s House sculpted the elaborate Ionic capitals, naturalistic floral ornaments, and complex geometric friezes in that building. The acanthus rinceaux and griffins on the north door and the delicately modeled floral swags and paterae above provide superb testimony of the talent available within their circle (fig. 39). Although the carvers are identified by name, they rarely appear in government records. Construction accounts for the President’s House are also vague, making it difficult to connect individuals to their specific work or gauge their influence on stone carving in the wider region.[38]

The stone carvers at the President’s House are the only tradesmen who can currently be associated with a group of ornate neoclassical tombstones made locally during the 1790s. The most sophisticated of these mark the graves of Sarah (1764–1792) and Eleanor Wren (1746–1798) at Christ Church, Alexandria. Now damaged by time and the elements, the stones attest to their carver’s knowledge and mastery of sophisticated classical detail (figs. 40, 41). Soon after these stones were carved, similar details appeared on furniture attributed to the Washington school.

In 1801 President-elect Thomas Jefferson expressed concern that America lacked sculptors capable of producing classical statuary worthy of a capital city. After Henry Latrobe was appointed Surveyor of Public Buildings in 1803, the two men formulated a plan to address that problem. Two years later Latrobe requested assistance from Jefferson’s friend and former neighbor Philip Mazzei (1730–1816) who was working in Rome as a vintner and merchant:

The Capitol was begun at a time when the country was entirely destitute of artists, and even of good workmen in the branches of architecture. . . . It is now so far advanced as to make it necessary that we should have as early as possible the assistance of a good sculptor of architectural decorations.[39]

Mazzei had hoped to entice Italy’s renowned sculptor Antonio Canova (1757–1822) to come to America, but Napoleon Bonaparte had long since compelled the artist—apparently under significant duress—to produce sculpture for his château at Malmaison as well as portrait busts, full-length figures, and equestrian statues depicting the general for public buildings and spaces. As an alternative, Mazzei hired Canova’s associates Giuseppe Franzoni (1779–1815) and Giovanni Andrei (1770–1824). They arrived in America on March 3, 1806, and immediately began working for Latrobe. Franzoni was especially skilled at sculpting figures and sculpted some of Latrobe’s most ambitious designs for the Capitol. His work included a full-length representation of Liberty and the Eagle for the south wing of the Capitol, corn capitals (fig. 42) for the Senate vestibule, and a row of caryatid supports for the gallery rail above the old Senate Chamber. The caryatids were destroyed in the Capitol fire in 1814, but sketchy depictions of them are visible in Latrobe’s watercolor elevation for that chamber. They are significant because their 1808 date of completion makes them one of the earliest examples recorded in classical America, and because caryatids subsequently appear on early Washington furniture.[40]

After Franzoni’s untimely death in 1815, Andrei became the Capitol’s chief sculptor (fig. 43). Over the next twenty years, the latter hired several other carvers, including Franzoni’s cousin Francesco Iardella (1793–1831), who rendered Latrobe’s design for tobacco capitals in 1816 (fig. 44). Three years later, Andrei and Iardella began supervising a group of Italian and Scottish “carvers” whose names appeared on a payroll voucher documenting their work on “furniture for the Presidents House.”[41]

William Waters and the Influence of Annapolis Furniture Styles

Georgetown “Cabinet and Chair Maker” William Waters (1766–1859) may have apprenticed with Archibald Chisholm (act. 1770–1796), who emigrated from Scotland in 1772, partnered with Annapolis cabinetmaker John Shaw from 1772 to 1776, and married Waters’s sister Elizabeth (1755–1838) in 1777. Where Waters practiced his trade between 1787, when he presumably finished his training, and 1791, when he advertised in Georgetown for an apprentice, remains unknown. By 1793 he had established a shop near the river, where he offered sideboards, dining tables, breakfast tables, and card tables. Waters was the first tradesman in the immediate Washington area who advertised upholstered furniture, including easy chairs, close stool chairs, and bedsteads.[42]

William Waters’s ties to his brother-in-law must have been strong, since he left Georgetown briefly in 1793 to partner with Chisholm. In the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Daily Advertiser, they reported that they had “contracted to deliver a considerable quantity of Cabinet-Work in a short time” and would “give great encouragement to two or three Journeymen Cabinet and Chair Makers, at their Manufactory in Annapolis.” In 1794 Chisholm and Waters disbanded their partnership. Chisholm acquired a small plantation on the banks of the West River and became a planter. Waters returned to Georgetown but did not advertise until December 23, 1796, when he notified the public that he had “several experienced workmen . . . [who] enable him to supply his customers on very short notice.” At that time, his inventory included “several Sofas, covered with satin hair cloth and garnished with brass nails and socket castors, mahogany Chairs of different patterns . . . easy chairs . . . and bedsteads.”[43]

Waters appears to have anticipated the economic surge imminent with Congress’s move from Philadelphia. Among the “ready made furniture” he advertised in September 1799 were a “new billiard table handsomely finished, Mahogany chairs and sofas, Easy chairs, common and cabriole, Mahogany tables of different sorts and sizes, sideboards, desks and drawers, Wash bason stands, &c. with bedsteads of every description.” The following year, Waters moved to “Bridge Street, next door to Mr. Elisha Rigg’s Store” and diversified his business by providing “board and lodging” for “half a dozen gentlemen.” His last advertisement as a cabinetmaker appeared in 1804, when he announced “several beautiful Side Boards large and small, Northumberland Dining Tables in setts, oval and plain Card and Tea Tables, Desks, Drawers and Bedsteads, etc.” An addendum to the advertisement signaled his move away from the woodworking trades and toward broader mercantile pursuits involving “Wines, Spirituous Liquors, fresh Teas, Particular Green Coffee, first and second quality Sugars, and a variety of other articles in the grocery line.”[44]

In 1810, like many Georgetown tradesmen, Waters moved his shop closer to the seat of government, “near the Seven Buildings” on Pennsylvania Avenue, in Washington City. That year he advertised a “piano and new mahogany furniture,” but the wording suggests that he did not make those objects. From 1816 to 1827 Waters held several civic positions including city commissioner, alderman, and city magistrate. He died in Georgetown in 1859, at ninety-two.[45]

The furniture listed in Waters’s advertisements indicates that his shop produced a range of sophisticated neoclassical forms. Although no objects can be documented to him, a group of neoclassical sofas from the District of Columbia probably originated in his shop or that of his successor, William Worthington. Waters was the only cabinetmaker in late-eighteenth-century Washington who advertised that form. Three cabriole sofas with over-the-rail upholstery are known. One has plain tapered legs, and two have molded variants. The sofa illustrated in figure 45 descended in the Lipscomb and Quigley families of Georgetown and at one time belonged to Jessie Lipscomb (1797–1875), a wealthy grocer.[46]

The seat frame of the Lipscomb-Quigley sofa has front-to-rear braces and brackets like those on the Ingle example that descended in the Tyler and Belt families (fig. 36). Each corner is reinforced with a diagonal brace that is set into half-dovetails. The front braces are positioned near the leg, but those at the back are set farther out in order to span the rounded corners. To compensate for the inherent weakness of the joints at the rear corners, the maker reinforced them by gluing strips of linen over them. Looking glass makers often used this technique when constructing or repairing frames with heavy mirrors.[47]

The crest of the Lipscomb-Quigley sofa is lower in relation to the arms than most Baltimore examples of similar form. Sofas made in the District of Columbia also differ from their Baltimore counterparts in having crook’d rear legs. This feature occurs in British sofas and design book illustrations but is rare in American work.

A sofa made for Alexandria physician Peter Wise (1775–1808) is virtually identical to the Lipscomb-Quigley sofa, though with a much deeper seat (fig. 46). Wise family tradition maintains that the sofa was “made to order” for the hefty bachelor, who “weighed 318 pounds when he was 18 years old and was well over 6 feet tall.” When Dr. Wise died prematurely at thirty-three years of age, appraisers of his estate assigned it the significant value of $35.[48]

The most fully developed sofa in this group has a history of descent from Georgetown hotelier John Wise (ca. 1740–1815) (figs. 47, 48). He moved to Alexandria during the early 1780s and constructed a tavern on the west side of Royal Street, near the corner of Cameron, in 1785. Three years later he added a three-storey structure on the adjoining lot to create the City Hotel and Tavern. Each of that building’s principal dining rooms had chimneypieces with an overmantel and pediment, some with carved trusses and rosettes. Like the sofa, the City Hotel and Tavern attests to their owner’s appreciation of sophisticated furniture and architectural style.[49]

Circumstantial evidence suggests that Waters either trained or employed William Worthington Jr. (1775–1839) (fig. 49). Recent research suggests that the latter’s father was William Worthington Sr. (1756–1837) of Montgomery County, Maryland, and that his grandparents were John Worthington III and Susannah Hood, of Baltimore County, Maryland. Worthington probably became a journeyman in 1796, the same year Waters announced that he had “several experienced workmen” in his shop. Four years later, Worthington opened a “Cabinet and Chair Manufactory” in Georgetown, describing his production in much the same way that Waters did. The 1800 census of the United States listed Worthington as head of a household that included two older white females and three white males under the age of twenty-five.[50]

Worthington’s first shop was on High Street (now Wisconsin Avenue) near Georgetown’s finest homes. When Congress moved from Philadelphia in 1800, Worthington announced his relocation “to the City of Washington, near the Great Hotel,” midway between the President’s House and the Capitol. Later advertisements reveal that he did not close the High Street manufactory but kept it open through 1811, likely as a support facility for his growing business.[51]

Shortly after moving into Washington, Worthington realized that the best areas for businesses like his were along Pennsylvania Avenue in the vicinity of the President’s House and along New Jersey Avenue in Henry Ingle’s neighborhood. He began building a house and shop at 2105 Pennsylvania Avenue—four blocks from the President’s House—and moved there in 1803. Worthington’s home was next to the Six Buildings, a new row of fashionable brick town houses. The large scale, convenient location, and architectural sophistication of the Six Buildings attracted prominent tenants, including the Departments of State, War, and Navy. James and Dolley Madison and the War Department occupied other homes on the block before they were destroyed by fire in 1801. The Madisons returned to the neighborhood in 1814 after the British burned the President’s House. Like the Monroes, the Madisons later lived at the equally prestigious Seven Buildings, located nearby at the northwest corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Nineteenth Street N.W. Residents of this prosperous neighborhood became some of Worthington’s most important customers.[52]

As his business grew, William Worthington took apprentices from Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia. Seven can be identified by name, including Benjamin Middleton Belt (1785–1828) and John D. Hill (1793–1823), who came from prominent local families. Daniel Carroll of Duddington signed Belt’s 1802 indenture, but the former’s role in Worthington’s business, if any, remains unknown.[53]

Worthington’s public service, which included militia duty and membership on the city council, also kept him in the public eye. With William Waters shifting his business to mercantile pursuits after 1804 and Henry Ingle retiring from the trade in 1812, Worthington rose to the forefront of Washington’s cabinetmaking community. On June 15, 1814, he received his first presidential commission when he repaired a picture frame. Although he billed only a dollar, the job apparently opened doors.[54]

In 1815 “George Boyd, Esquire, Agent for the President’s Furniture,” received authorization to commission Worthington for work on behalf of the Madisons. The cabinetmaker’s statement detailed a large delivery on March 13 and several smaller ones running into the middle of June. Among the forms listed were a “secretary desk,” a large dining table, a writing table, two other tables, “two settees covered in linen,” a “couch on castors,” six chairs, a “large family bedstead complete,” five low beds, and a “common size bedstead.” The chairs were only $1.50 each, which suggest they were not upholstered. By contrast, the settees cost $45 each, and the couch was priced at $32. Worthington also provided a variety of services including “fixing blinds in windows,” putting a shelf on a mantelpiece, and repairing a looking glass. Worthington’s total charges to the government were $428, but Mrs. Madison assumed payment for the couch, which she took home to Montpelier in Orange County, Virginia. The term “couch” referred to a stylish French form that encouraged women to recline when seated. Today that form is often described as a recamier.[55]

The Monroe Presidency and the Influence of French Neoclassicism

Worthington also received the patronage of James Madison’s successor, James Monroe (1758–1831). Monroe’s aesthetic sensibilities began to coalesce after his 1786 marriage to Elizabeth Kortwright (1768–1830), daughter of a prosperous New York merchant. In 1796 Monroe received a two-year appointment as Minister Plenipotentiary to France. Shortly after arriving, the Monroes enrolled their daughter, Elizabeth (1787–1836), in the school of Mme Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Campan at St-Germain-en-Laye. There, Eliza forged a close friendship with Hortense Beauharnais, whose mother, Joséphine, had recently married Napoléon Bonaparte.[56]

The Monroes returned to America in 1799, the same year that Napoléon mounted a military campaign in Egypt. During the general’s absence, his wife, Joséphine, purchased the Château de Malmaison on the outskirts of Paris and hired Charles Percier (1764–1838) and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (1762–1853) to transform its interiors. The firm engaged that city’s most talented artists and artisans to drape, paint, gild and sculpt furnishings for an unprecedented classical interior with exotic Egyptian details, then presented their sumptuous designs in Recueil de décorations intérieures (1801). The expenses incurred by Napoléon’s extensive military campaign and Joséphine’s extravagant tastes threatened to bankrupt France’s treasury and forced Napoléon to approach the United States about purchasing the Louisiana Territory. After negotiating the purchase in France in 1803, Monroe served as Minister Plenipotentiary to Great Britain from 1804 to 1807. Although his new station was London, the Monroes spent much of their time in France and attended Napoléon’s coronation in Notre-Dame Cathedral on December 2, 1804.[57]

In the midst of these world-changing events, Eliza Monroe and Hortense Beauharnais went about their business as friends. Though undocumented, Eliza probably saw Empress Joséphine’s private round bedchamber, which was dominated by a monumental bedstead designed by Percier and Fontaine (fig. 50). The underlying structure, though comparatively simple, had gilded swans perched atop stands on either side of the headboard and a cornucopia at either end of the footboard. A bold canopy, topped by a gilded Roman eagle, towered overhead, with red and white silk hangings embroidered in gold. Objects of this type had a profound influence on the interior decor of the Monroes’ house in Washington.[58]

During James’s presidency, the Monroes spoke French in private, employed a French chef, and decorated the President’s House with French furnishings. The firm Russell and LaFarge—America’s consular agents at the French port of Le Havre—commissioned furnishings from the finest workrooms of Paris. Among the objects they shipped to Washington in 1818 were a thirty-eight-piece suite of gilded beech seating furniture by Pierre Bellangé, silver by Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot, painted and gilded porcelain by Honoré and Dagoty, figural bronze clocks by Denière et Mateline, and lighting devices and mantel ornaments from Pierre-Phillipe Thomire. The Monroes also purchased goods and services from French émigré artisans including Charles Alexandre, who did much of the upholstery and paperhanging for the Monroes in the President’s House, and Louis Labille, who provided the same services for their private residence in Washington and their country home, Montpelier.[59]

Some of the most significant French influence on the President’s House appears to have come from Baron René de Perdreauville. Born into an aristocratic Parisian family, he fled France following Napoléon’s abdication. In 1815 de Perdreauville immigrated to America with his wife, Marie-Victoire-Adèle Le Masurier, and their children. It is likely that the Monroes knew him when they lived in France. Three years after his arrival in this country, the couple hired de Perdreauville to oversee an upholstery workroom and ancillary facilities including a storeroom for wood and a forge for making specialized hardware. His workmen also painted window cornices, upholstered seating, fabricated draperies, and made upholstered French armchairs, described as fauteuil.[60]

In 1818 Monroe issued a pamphlet titled Message from the President of the United States upon the Subject of the Furniture Necessary for the President’s House, in which he criticized government allocations for furnishings as “altogether inadequate.” His goals were to increase congressional appropriations for furnishings and to reappoint George Boyd as agent for their acquisition and care. With Boyd answerable to Congress, Monroe could furnish the President’s House as he saw fit while shielding himself from public scrutiny. Editorials in a number of newspapers condemned “the expensive manner in which Congress have thought proper to furnish the President’s house,” but placed little blame on Monroe.[61]

After a brief respite to alleviate criticism, work resumed at the President’s House. At this stage of the project, the Monroes and their French advisers turned to local artisans to supplement the elaborate furnishings ordered from abroad. Of the half dozen cabinetmakers who contributed to the project, William Worthington was clearly their favorite. None of Worthington’s presidential furniture from this period has been identified, but his invoices to Boyd describe specific forms and, in some instances, individual details.[62]

On August 4, 1818, William Worthington submitted a bill that included “1 mahogany French bedstead, fluted posts” valued at $45 and another example for the “northeast room” valued at $22. The first was destined for the room occupied by the president’s daughter, Eliza Monroe Hay, and the second, for a nearby guest room. Two days later, Washington turner Joseph Fagains charged Boyd $2 for “turning 8 pieces for bedsteads.” The “pieces” were undoubtedly finials that surmounted each post. The following spring, Worthington’s former apprentice Benjamin Belt submitted an invoice for “2 Crowns for bedsteads” at $22 each and “2 Urns for do at $5 each.” The “urns,” which may have been carved, would have capped each “crown.”[63]

Charles Alexandre’s bill of January 29, 1819, describes his work for the northeast room—“Making a window drapery, and crown bed, putting up the same for 12.00”—and includes a charge for “iron work for the crown . . . 1.00.” Two months later, he submitted another invoice for upholstery in Eliza’s room, which included window dressings and bed hangings that were twice as expensive as those provided earlier: “two pairs of window curtains, &c. $25.00; making the trimmings of a crown bed, &c. . . . $25.00; 9 yards of cambrick . . . $2.70; three dozen rings . . . 75[¢]; 1 clothes pin . . . 50[¢]; 32 yards of red and yellow fringe at $1.50.”[64]

A French bedstead made in Washington, D.C., matches descriptions of the example Worthington made for Eliza Monroe (figs. 51-53). Instead of balusters based on Renaissance forms, the maker used Doric columns with stop fluting for the corners and a simpler version of that order for the colonnades of the headboard. Of all the classical orders used by eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Chesapeake builders and turners, Doric was the most popular.[65]

Beneath the capitals are swags separated by jabots (fig. 53), a decorative detail used by regional stone carvers since the 1790s and by makers of comparable “composition ornaments” on neoclassical chimneypieces, cornices, doorways, and other architectural fixtures installed throughout the city. A mantelpiece on the second floor of the Bank of Alexandria has slender columns with similar swag-and-jabot decoration and was likely made by Irish-born ornament maker George Andrews (d. 1816) (figs. 54, 55). At Jefferson’s request, Andrews moved from New York to Washington to work at the President’s House. It is possible that one of the carvers who made molds for Andrews carved parts of Eliza Monroe’s bedstead and that the ornaments on architectural fixtures in her bedroom echoed those on the furnishings.[66]

Although missing from the bedstead, the crown was a separate unit suspended at least four feet above the tops of the posts. Sheraton published designs for several bedsteads with crowns, a form he called a “French Bedstead” or a “French State Bed.” His engravings suggest that the crown on Eliza’s bed had a rectangular frame surmounted by a domed or peaked top. The curtains would have been attached around the lower edge of the crown, allowing them to drape over the iron rods and ends of the bed. The rods, which were listed in Charles Alexandre’s invoice, were probably bowed or serpentine, with a broad flange pierced with a hole on each end. Iron pins extending up from the tops of the posts fitted into the holes. With a finial placed on top of each post, a larger finial capping the crown, and elaborate curtains below, the bedstead would have resembled an exotic tent.[67]

Alexandre’s bill for work in Eliza’s bedroom also included a $4.00 charge for “2 stands for the eagles.” An “Inventory of the Furniture in the President’s House” taken on March 24, 1825, listed “1 Elegant mahogany bedstead, gilt eagle mounted” among the furnishings in the “fifth room,” which was unequivocally hers. Adjacent entries listed “1 Hair mattress, feather bed, bolster, and pillows . . . 1 Pair sheets, one pair blankets, Marseilles quilt [and] . . . 1 set chintz dome bed curtains.” The “2 Sets [of] chintz window curtains” listed separately almost certainly matched the fabric on the bed.[68]

Designs in Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (1791) and Cabinet-Maker’s Dictionary (1803) are possible sources of inspiration for the basic form and certain specific details on Eliza’s bed. The “Canopy Bed” illustrated on plate 6 in the 1804 edition of the Drawing Book has a wall-mounted crown capped by an eagle (figs. 56, 57) and resembles the example that Percier and Fontaine designed for Empress Joséphine. In contrast to the swans that flanked her bed, Sheraton used a dove perched atop a stand, its wings outspread and beak clasping drapery. Given the fact that no comparable published image from the period is known, plate 6 may well have influenced Worthington’s design.[69]

Another Washington artist with intimate knowledge of French state beds was Italian sculptor Giuseppe Valaperta. According to Latrobe, Valaperta “was engaged before the fall of Napoleon in the decoration . . . at Malmaison.” The sculptor’s personal effects, inventoried in 1817, included a profile of Joséphine Bonaparte taken from life at her palace. Given the similarities between her state bed and Eliza’s crown bed, it is possible that Valaperta may have been involved in the latter object’s design.[70]

Worthington or the Monroes probably commissioned a local carver to furnish the eagles for Eliza’s bed. Their options included specialists accustomed to producing ornaments for furniture and architecture as well as stone carvers and sculptors accustomed to working in wood (figs. 58, 59). A voucher submitted by Giovanni Andrei requested payment for “Four Carvers” who had worked on “Furniture for the Presidents House” in August and September 1819. Four of these men are identified by name: Francesco Fortini, Owen Horgan, John Woods, and one J. Elyson. Their work, which took a cumulative 207 1/2 days, must have been important, since it required oversight by Andrei and Francesco Iardella. If the eagles on Eliza Hays’s bedstead originated within that circle of craftsmen, they would have been its crowning glory.[71]

Competing Craftsmen, Competing Styles

Worthington’s principal competitor appears to have been William King Jr. (1771–1854), a Pennsylvania native who trained with Annapolis cabinetmaker John Shaw, established a shop in Georgetown in 1795, and worked there for more than fifty years. Like Worthington, King had strong ties to James Monroe. In May 1818 Monroe wrote Commissioner of Public Buildings and agent for the President’s House furniture Samuel Lane:

The chairs, for the East room, and tables and any other articles, for that room and the mahogany benches, small tables and chairs for the hall will be made by Mr. Worthington and Mr. King. I have reason to think that King has a good model for the chairs, and that it may be better for him to make them and for Worthington to make the other articles, or as many as can, in time. But arrange this in a delicate manner between them, as I had spoken to Mr. Worthington first.

In December 1818 King received payment for a handsome suite of French-inspired seating comprising twenty-four armchairs valued at $33 each (fig. 60) and four sofas at $49.50 each. Lane’s copy of the invoice noted that the total had been reduced because the upholstery and final varnish were “not done.” A number of the chairs are known, but the sofas have not been identified. The sofas, which matched the chairs in almost every detail, appear in a Mathew Brady photograph of the President’s House interiors taken in 1865, but it is not known if they survive.[72]

King made a Grecian sofa and eight matching chairs for Georgetown businessman Clement Smith (1776–1839) and his wife, Margaret (1783–1862) (figs. 61, 62). A closely related sofa without carving descended in King’s family. The sofas are distinguished by having unusually heavy seat rails, which support a separate wooden frame for upholstery. The frame has four front-to-back braces. This feature does not appear on earlier Washington seating.[73]

The Smith family sofa and chairs were carved by the same hand, although the grapevine on the chairs is on an oval field with a plain ground, whereas the decoration on the sofa is on a rectangular field with a punched background. Aside from the President’s House seating, these are the only chairs that survive from King’s shop.