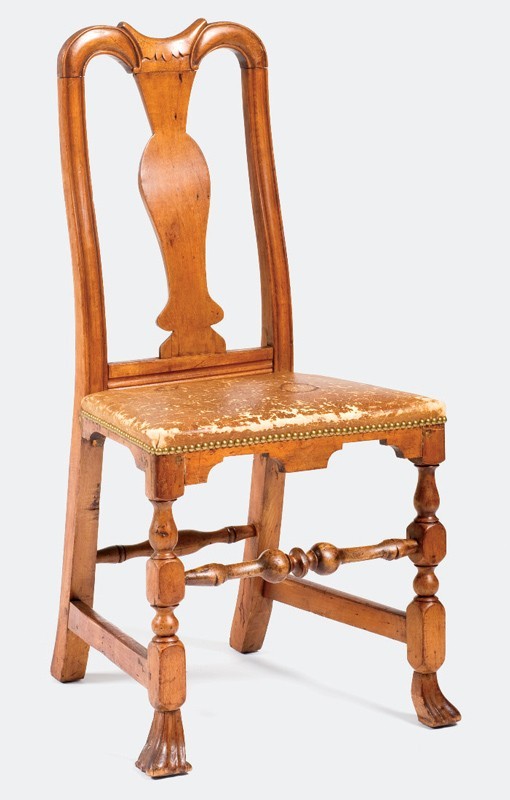

Side chair attributed to John Gaines III, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1735–1743. Maple. H. 40 1/4", W. 20 1/2", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The blocked, rush seat and the retaining strips are restored.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

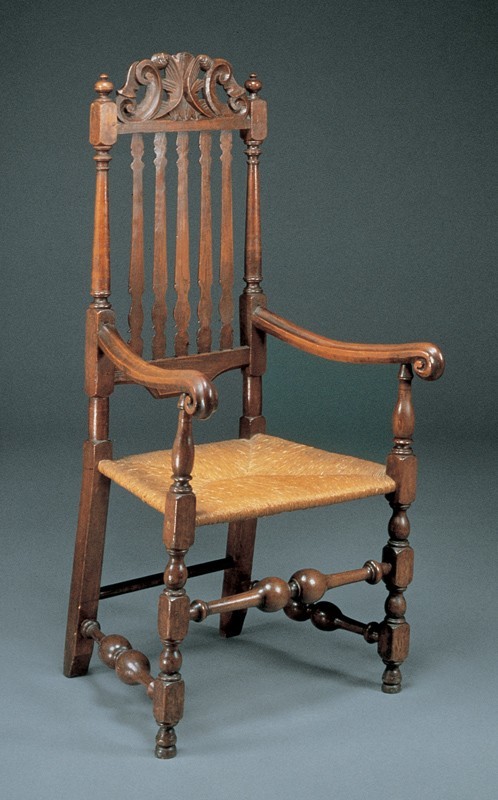

Armchair attributed to John Gaines III, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1735–1743. Maple. H. 42 3/16", W. 25 1/2", D. 16 3/8" (seat). (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Library, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.) This photograph was taken ca. 1930. At that time, the rush on the blocked seat frame and some of the arched retaining strips were missing.

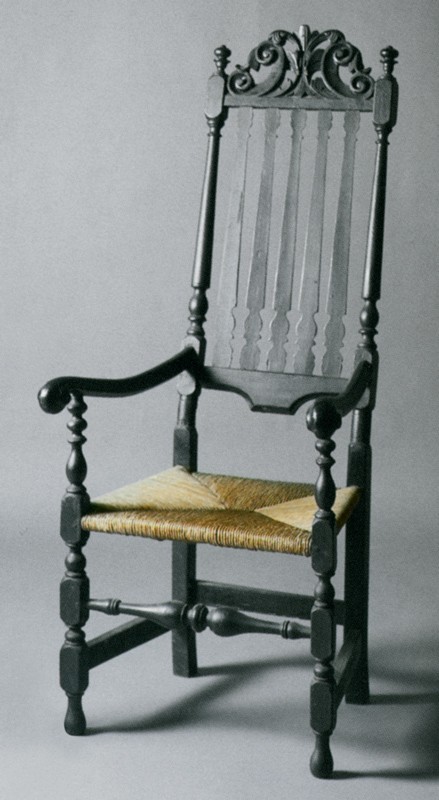

Cane chair, London, England, 1710–1720. Beech. H. 53 5/8", W. 18 1/4", D. 18 3/8". (Courtesy, Cape Ann Museum; photo, Andrew Davis.) High-backed London cane chairs with scrolled crests may have influenced the design of Gaines chairs. This example may have been owned in Essex County, Massachusetts, during the eighteenth century.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Andrew Davis.) Although the design of the crest is metropolitan in origin, the carving is perfunctory in execution.

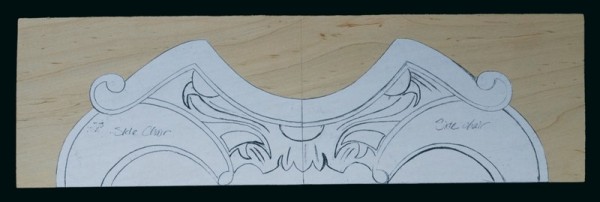

Paper pattern of a reproduction Gaines crest glued to a crest blank. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

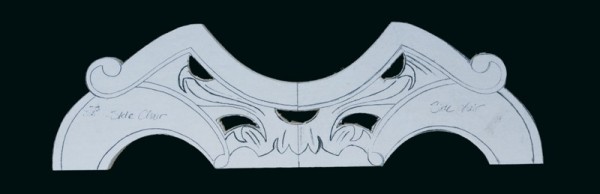

Reproduction Gaines crest with the apertures sawn out. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

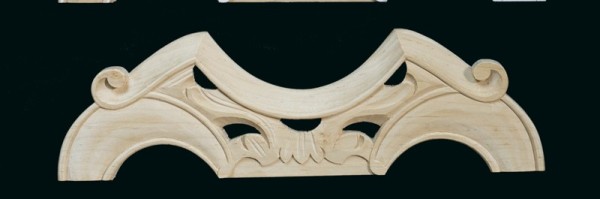

Reproduction Gaines crest partially carved. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Reproduction Gaines crest at a later stage of carving. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Detail of an armchair attributed to John Gaines III, showing an overhead view of the arm. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of an armchair attributed to John Gaines III, showing a side view of the arm. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

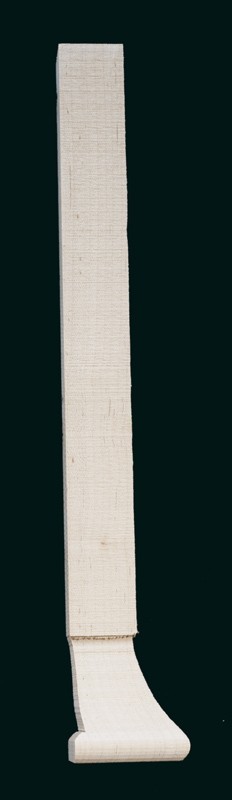

Sawn blank for a reproduction Gaines arm. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Roughed-out molding for a reproduction Gaines arm. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Carved grip for a reproduction Gaines arm. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Sawn foot for a reproduction Gaines chair. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Carved foot for a reproduction Gaines chair. (Courtesy, Andersen & Stauffer; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Detail of a Gaines chair from the Brewster set (see fig. 1), showing the restored, blocked rush seat and arched retaining strips based on those of the armchair illustrated in fig. 2. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, purchased with funds provided by an anonymous donor and Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Alfond; photo, Jim Schneck.)

Detail of a Gaines chair from the Brewster set (see fig. 1), showing the small shaved bracket supporting the restored rushed seat frame.

Rear view of the chair illustrated in fig. 1, showing the rough dressing of the frame. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1735–1750. Maple. H. 42 1/4", W. 17 3/4", D. 18 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, George Fistrovich.)

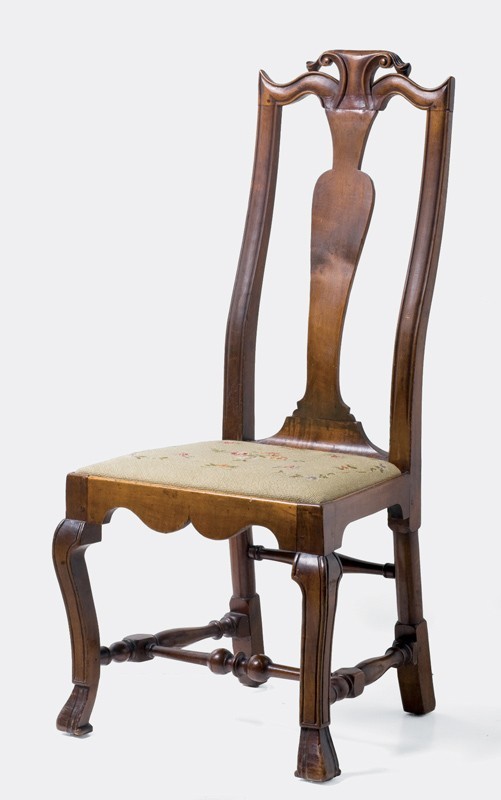

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1735. Walnut and maple. H. 41 1/2", W. 19 1/2", D. 20". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, possibly Boston, Massachusetts, or Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1730–1750. Maple. H. 42", W. 26", D. 25". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, possibly Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1730–1750. Maple. H. 42 1/4", W. 19", D. 18 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Armchair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1725–1760. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 44 1/2", W. 26 1/2", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Russell Sage; photo, Gavin Ashworth / Art Resource, NY.)

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1735–1750. Maple. H. 40 1/4", W. 20 5/8", D. 16 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) An apprentice or journeyman from John Gaines III’s shop may have made this chair.

Detail of a foot on the chair illustrated in fig. 25, showing the pieced-out toes. (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1740–1760. Maple. H. 30 7/8", W. 20 3/4", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) An apprentice or journeyman from John Gaines III’s shop may have made this chair. The upholstery is modern. Originally, the chair had a blocked rush seat held by retaining strips.

Armchair and two side chairs, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1740–1760. Maple. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Leigh Keno Antiques.)

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1740–1760. Maple. H. 41 3/8", W. 21 3/8", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Strawbery Banke Museum, anonymous loan; photo, Andrew Davis.) The feet are restored. The turnings on the side and rear stretchers are rare in Boston seating but common in Portsmouth work.

Armchair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1740–1775. Maple. H. 44 5/8", W. 25 1/2", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village; photo, Andrew Davis.) The bottoms of the feet are restored about 1".

Armchair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1740–1770. Maple. H. 46 3/4", W. 24 3/4", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) The bottoms of the feet are restored about 1 1/2".

Banister back armchair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1740–1770. Maple and rush. H. 45 1/2", W. 25", D. 19". (Collection of Shelburne Museum. 3.3-262. Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) With their drooping terminals, the arms of this chair resemble those on later Portsmouth examples with other crest designs. The tenons on the crests of these chairs usually have only one shoulder, sometimes on the front face, sometimes on the rear face, and the shoulders of the tenons are coped to conform to the rounded posts.

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1740–1770. Maple. H. 40", W. 21", D. 14". (Private collection; photo, Northeast Auctions.)

Armchair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1730–1760. Maple and ash. H. 45 3/4", W. 25", D. 20". (Courtesy, Strawbery Banke Museum, gift of Sally Sangser and Nancy Borden in memory of their brother Henry Chandler Homer; photo, Andrew Davis.) The feet are missing.

Armchair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1730–1760. Maple and ash. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1730–1760. Poplar, maple, and ash. H. 47 1/2", W. 21", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Screven Lorillard; photo, Gavin Ashworth / Art Resource, NY.)

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1750–1775. Maple and ash. H. 48 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 20". (Courtesy, Witch House Museum, Department of Parks and Recreation, City of Salem, Massachusetts; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1750–1775. Maple and ash. H. 45 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 19". (Courtesy, Witch House Museum, Department of Parks and Recreation, City of Salem, Massachusetts; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Overmantel panel, Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1740–1760. Pine. 18 1/4" x 55". (Courtesy, Ipswich Museum, gift of George W. Caldwell; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1740–1760. Maple and ash. H. 52 1/2", W. 18 3/4", D. 13 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Side chairs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1740–1760. Maple and ash. H. 46", W. 18 5/8", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Ipswich Museum; photo, Andrew Davis.) The carving of the triangular reserve on the stay rails is slightly different.

Side chair, possibly John Gaines II or Thomas Gaines I, probably Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1730–1760. Maple. H. 42 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 15". (Courtesy, Ipswich Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) It is possible that the maker and carver of this chair were not the same person.

Side chair, London, England, 1725–1740. Beech. H. 42 1/2", W. 20 1/8", D. 19". (Courtesy, Strawbery Banke Museum, gift of Mary Storer Decatur; photo, Andrew Davis.) The feet are missing.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1740. Maple and ash. H. 53", W. 24 1/4", D. 24 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) The design of this chair has exact parallels in Boston leather chairs.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 44. (Photo, Andrew Davis.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1740. Maple and ash. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Northeast Auctions.) This chair and the example illustrated in fig. 44 have rectangular side and rear stretchers, whereas most chairs from other New England ports have turned examples. The use of rectangular side and rear stretchers on Boston banister-back chairs supports Benno Forman’s theory that they were made side by side with leather chairs.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1740. Maple and ash. H. 49", W. 18 3/4", D. 16 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Salem, Massachusetts, 1725–1750. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 48 5/8", W. 26 1/8", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are restored. The arms of Salem banister-back chairs display marked variation. On this example, the arms have a pronounced outward twist at the wrists and large scrolled terminals. There may be some stylistic relationship between these arms and those of Portsmouth seating.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Detail showing the gouge cuts on the upper surfaces of the end volutes of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Armchair, Salem, Massachusetts, 1725–1750. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 49 3/4", W. 22 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The arms of this chair are relatively straight and have small terminals.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Salem, Massachusetts, 1725–1750. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 48 5/8", W. 18 3/8", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic New England, gift of Dorothy S. F. M. Codman.)

Side chair, Salem, Massachusetts, 1725–1760. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 48 3/8", W. 18", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.). The feet are restored.

Side chair, London, England, 1720–1740. Beech. H. 4 3/4$", W. 18 1/2", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Jim Schneck.)

Side chair, Salem, Massachusetts, 1735–1760. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 47 7/8", W. 18", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Cape Ann Museum, gift of Alfred Mayor; photo, Andrew Davis.) This chair and its mate descended in the Dennison family of the Annisquam section of Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Side chair, Salem, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 47", W. 18", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are restored.

Armchair, Salem, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 49", W. 24 3/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Glebe House, purchased with funds provided by Lispinard Seabury Crocker; photo, Tom Schwenke.)

Armchair, southern Essex County, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Woods not recorded. H. 50 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.) The black-and-gold paint and incised decoration are nineteenth-century embellishments.

Side chair, southern Essex County, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple. H. 47 1/2", W. 19", D. 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, Jim Schneck.)

Armchair, southern Essex County, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. (Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 2 vols. [Framingham, Mass.: Old America Company, 1928], 2:2089.)

Armchair, Newbury, Massachusetts, 1730–1760. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 49 3/4", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Newbury, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Woods not recorded. H. 47 1/2", W. 23", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Friends of Historic Kingston and the Fred J. Johnston Museum, bequest of Fred J. Johnston; photo, Douglas Baz.) The feet are restored.

Side chair, Newbury, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 46", W. 19 1/2", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Old Newbury, gift of Margaret FitzGerald and Iola Benedict; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Newbury, Massachusetts, 1740–1770, Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 46 5/8", W. 19 1/2", D. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Newbury, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 45 1/2", W. 19", D. 15 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1740. Maple. H. 45 1/2", W. 19", D. 18". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Skinner.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1725–1760. Maple. H. 43 1/2", W. 20 7/8", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1730–1750. Maple. H. 48 1/2", W. 25 5/8", D. 23 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The feet are partially restored.

Side chair, possibly Essex County, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple, poplar, and ash. H. 47 1/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, probably northern Essex County, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple and ash. H. 49 1/2", W. 18", D. 16 5/8". (Courtesy, Currier Musuem of Art; photo, Andrew Davis.) This chair is one of four identical examples that reputedly belonged to Meschach Weare of Hampton Falls, New Hampshire.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 4.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 22.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 23.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 30.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 34.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 36.

Detail of the crest of the chair (left) illustrated in fig. 41.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 42.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 48.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 51.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 55.

Detail of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 62.

Detail of the back of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 62.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 67.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 68.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 70.

Detail of the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 71.

Almost every prominent New England auction house has offered seating attributed to the Gaines chair makers of Ipswich, Massachusetts, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. During the last twenty years, attributions for some chairs have shifted to “Boston, North Shore, or southern New Hampshire.” This broad-brush approach reflects recent publications that assert Boston origins for certain seating forms. This article assesses the background of Gaines attributions and the traits of a securely documented set of four side chairs made by John Gaines III of Portsmouth. Chairs attributed to Boston, Salem, Ipswich, Newbury, and Portsmouth that were not made by either of the two Gaines shop traditions are also discussed, so that future scholars will not confuse them with Gaines work. Even with the publication of these various shop traditions, much remains to be discovered about eastern Massachusetts and New Hampshire seating of the 1720–1760 period.[1]

Origins of the Gaines Attributions

Three members of the Gaines family are involved in attributions pertaining to this study: John Gaines Jr. (1677–1748) of Ipswich, Massachusetts; John II’s younger son, Thomas Gaines (1712–1761), who stayed in Ipswich and worked with his father; and John II’s older son, John Gaines III (1704–1743), who moved from Ipswich to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, about 1724 and established his own shop. John Gaines III’s son George (1736–1809) was a woodworker, but was too young at the time of his father’s death to have been trained by him.[2]

The only securely documented “Gaines” seating from either Ipswich or Portsmouth are four surviving chairs from a set made by John Gaines III for his personal use (fig. 1). The chairs descended in the Brewster family of Portsmouth and were well known by the late 1870s. All four remained in the family until 1998, when the chairs sold at auction. Important traits of this set are their stylized pierced, carved crests (fig. 2) and their solid, carved, oversize Spanish feet with a central groove on the middle toe. Of less obvious concern are the turnings of the front and rear stretchers as well as the splat profiles and the captured rush seats.[3]

An armchair with identical features (fig. 3) can also be attributed to John Gaines III’s Portsmouth shop. It entered the antiques marketplace during the 1920s and was subsequently acquired by Mitchell Taradash, a prominent collector. With its outward flaring molded arms and bold scrolled grips, this example has been celebrated as the finest surviving Gaines armchair.[4]

By the beginning of the twentieth century, several features associated with the Gaines armchair and side chairs were considered highly desirable by American furniture collectors. Even though the Gaines name was not yet assigned to these seating forms, unscrupulous dealers began making fakes similar to the armchair, often by altering period examples. This practice continued well into the 1970s if not later.[5]

The crest design favored by John Gaines III (fig. 2) differs from the C-scroll-and-foliate type seen on most turned New England banister backs (see fig. 45) as well as those on stylistically later seating with cabriole legs (see fig. 68). His archetypal crest has a triple-swept cove molding that ends in volutes at each end. Underneath this molding is stylized, carved leafage framed by piercings. Flanking the foliage are secondary carved moldings that merge into complementarily molded rear posts.

The crests of Gaines chairs were carved in much the same way as those on contemporaneous British (figs. 4, 5) and New England seating. Elements of the design were laid out using a pattern likely made of paper, pasteboard, or some other material that was thin and easily registered with wrought finish nails or other fasteners. Evidence for attachment is rare because most carvers affixed their patterns in areas where wood was designated for later removal. On Gaines chairs, the crest cutouts would have been logical sites. What is not clear is how much information period patterns transferred to the piece being worked. Most carvers who produced the same designs over and over required little guidance to outline, model, and shade their work.[6]

Today, replicating the crests for a set of Gaines chairs begins with photography of an original specimen and the production of full-scale drawings, the latter of which can be photocopied and glued to each crest blank to insure uniformity (fig. 6). Mortises for the post or stile tenons are cut before the carving begins. If a mistake is made, the time required to carve the crest is not lost. The next step is to saw out the interior apertures with a coping saw (fig. 7). It has been speculated that the apertures were roughly excavated with vertical gouge cuts, but such an approach seems too risky. The gouging theory emerged because of counter-chamfering found on the reverse surfaces of carved crests with piercing. Some have thought that this chamfering was intended to clean up tears from blasting through the crest blank with gouges, but the chamfers were more likely intended to lighten the appearance of the carving.

The following step is to rough out the triple-swept cove molding with gouges (fig. 8). In fact, almost all the modeling of the crest can be executed with as few as six to ten different diameters of gouges. Vertical strikes outline the pellets of the volutes and the outlines of leaves, while most of the rest of the carving involves holding the gouges at low angles. Smoothing the surfaces of some forms is accomplished with flat chisels. The final flourishes are made with V-shaped parting tools, used to indicate the veins in the leafage (fig. 9). Another final adjustment is fairing the moldings into those of the rear posts, which is fine-tuned after the chair is assembled.

The arms of Gaines chairs (figs. 10, 11) rise at the juncture with the front posts, then flare out sharply to terminate in molded scrolls with protruding volutes. These features, above all others, have contributed to John Gaines III’s reputation as a masterful designer and carver, but it is unlikely that they are an original conceit. Similar terminals are seen on English armchairs, which may, in turn, have been based on Venetian prototypes renowned for their extravagant forms and detailing.[7]

Most of the work required to produce scrolled arms like those on Gaines chairs involves sawing, rather than carving (fig. 12). The basic shape is established by patterns, one for the overall plan and perhaps two for the side elevation of the arm. The rough outline of the protruding volutes could have been sawn or established with gouges and chisels, but evidence of the former would have been removed during the finish carving.

After the arm is sawn to shape, the chamfers on the underside are cut with a spokeshave, and the molded upper surfaces are roughed out with gouges. Some makers may have used a rounded bench scraper to smooth these molded surfaces, almost in the manner of using a scratch-stock iron (figs. 13, 14). Other makers of Portsmouth chairs seem to have used scratch stocks in this location. In carving the protruding volutes, the first task is locating the central elements, which stand out in high relief. These are rendered with vertical cuts made with a relatively small gouge. The carver then has to decide if he will begin at the outside of each scroll and work in, or the reverse.

The oversize Spanish feet of Gaines chairs conform to a fairly strict pattern and are made entirely from the stock of the front posts (figs. 15, 16). This was a wasteful procedure, since it required cross-sectional dimensions greater than those needed elsewhere. This technique differs from that used for most metropolitan seating, wherein Spanish feet were constructed by gluing pieces of wood to the posts to provide stock for the protruding toes. Gaines feet are also distinguished by being severely recessed, on all four sides, where they meet the block above. The arris creating the recess was turned in sequence with the urns on each post. The feet protrude much farther than those on most contemporaneous English and Boston chairs, but not enough to prevent the stock from being centered on the lathe. Only a single profile pattern is required to lay out the foot, which is sawn from the front and the side to produce all four elevations. The two inner faces of the foot are cleaned up with a flat chisel, and most of the saw kerfs on the outer faces are removed during carving. The carving is restricted to two flutes on the outer sides of the feet and a deep, flat-bottomed groove on the leading edge of the toes. Almost all this work is done with gouges. Most inaccuracies regarding Gaines attributions are based on the feet. However, as Portsmouth chairs by other makers reveal, the foot design associated with John Gaines III was not exclusive to his shop (see fig. 36).

The turnings on Gaines chairs are fairly sophisticated in form and arrangement. Some armchairs have front stretchers with exaggerated balusters separated by a thin torus molding with flanking scotias; however, large-diameter turnings are not exclusive to Gaines chairs. The rear stretchers of Gaines chairs often display barrel-like, extended knops at the centers, although some chairs have smaller, sharper knops in the same location.

The vasiform splats, or banisters, of earlier Gaines chairs are a variant of the yen-yen or “Chinese-baluster-vase-on-a-pedestal” form. Another version of this design, in which the pedestal is set on top of the vase, appears on other Portsmouth chairs of roughly the same period, like those illustrated in figures 25 and 29. Both splat designs have metropolitan precedents, although the lack of filleting in the Gaines examples makes them appear less architectural.

The seats of most Gaines chairs also differ from those on comparable New England examples, which have rush bottoms suspended from roughly shaved rails. Craftsmen in the Gaines tradition typically used rectangular seat rails with conventional mortise-and-tenon joints and made separate frames with exposed blocks at the corners to accommodate the rush (fig. 17). Armchair seat frames are supported by four small brackets nailed to the rear posts; side chair seat frames rest on ledges cut into the front posts and brackets nailed to the rear posts (fig. 18). Retaining strips that are nailed on top of the seat rails keep the frames in place. These strips, which have a simple arched profile, are often missing. On many Gaines chairs, the original rushed frames have been replaced with textile- or leather-covered slip seats or over-the-rail upholstery (see figs. 25, 27).[8]

A final feature of Portsmouth Gaines chairs is their extremely coarse finish. The joinery is about on a par with metropolitan work, but the rear surfaces of the posts and splats are often very roughly planed and not smoothed with shaves or scrapers (fig. 19). These defects contradict the heroic folklore celebrating John Gaines III as a meticulous craftsman. Aside from what can be gleaned from surviving examples, little is known about the seating made in John Gaines III’s shop. Scattered account book references indicate that he traded sets of chairs described as “black” or “banister [back]” with various Portsmouth artisans and merchants like Sir William Pepperell. Undoubtedly, such chairs represented the bulk seating Gaines made for export and most probably had plain crests and turned feet. By the same token, the archetypal chair typically associated with John Gaines III probably represented commissioned work for local consumption.

Boston Prototypes for Portsmouth Gaines Chairs

Low-backed Boston leather chairs with molded crests have been cited as possible antecedents for the Gaines crest. These forms are, however, extremely rare today and somewhat implausible as prototypes. It is more likely that closer Boston (see fig. 22) or London (figs. 4, 5) models existed. Certainly, the compositional device of a great molded scroll with a central breakout was current in many London high-backed cane chairs. Paradoxically, the tallest London cane chairs ever made, dating 1710 to 1720, coincided with the emergence of designs, like the Gaines chairs, that mimicked the more compact proportions of Chinese seating.[9]

A standard type of Boston chair with a vasiform banister has often been mistakenly associated with the Gaines chair makers of Portsmouth (fig. 20). The Boston examples have features associated with John Gaines III, but most deviate in two important respects: the toes of their Spanish feet are applied; and the retaining strips of the seat frames are flat, with quarter-round edges. The Boston chair illustrated in figure 20 has been altered in the same manner as many Gaines chairs: the inner edges of the retaining strips have been trimmed back to accommodate a replaced, upholstered, loose seat. As the rough rear surfaces of Gaines chairs suggest, craftsmen in those shops may have been following Boston precedent in the way they finished their products. Boston chairs like the example illustrated in figure 20 relate directly to a specific model of leather chair produced in that city (fig. 21).[10]

Both the vasiform and leather-backed variants of this type of Boston chair have a design defect also seen on other seating from this period. When making such chairs, the shoulders of the joints between the seat rails and rear posts should be sawn at an angle so the rear heels and the back of the crest rail are plumb, which is the case in most metropolitan seating. On several Boston chairs, the heels extend back farther than the crest, giving those objects the appearance of leaning forward. Although this feature has been cited as diagnostic in attributions to John Gaines III, it was probably influenced by contemporary Boston work.

An armchair, possibly made in Boston, may represent another potential prototype for Portsmouth Gaines chairs (fig. 22). This beautifully conceived and executed chair, with a tight, highly detailed crest, appears at first glance to be a Gaines chair. On sustained examination, its turnings and carving differ substantially. The toes are applied, and the arms do not have the exaggerated volutes seen in Gaines chairs. Furthermore, the carving of the crest does not seem to relate to leafage executed by John Gaines III or by his possible carving subcontractor, Joseph Davis of Portsmouth.[11]

Another chair whose origin is more ambiguous has a unique variant of the double-peaked, molded crest design (fig. 23) and a blocked, rushed seat frame—a detail not commonly seen on Gaines chairs. The turnings share some features with Gaines chairs but depart in other respects. This could be another Boston prototype or, more likely, a Portsmouth outlier from the main Gaines shop tradition.[12]

Portsmouth Chairs in the Gaines Style

In her catalogue of early American furniture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, furniture historian Frances Gruber Safford attributed the chair illustrated in figure 24 to John Gaines III, largely based on its having feet similar to those associated with his shop. She also argued that it originally had heavily scrolled arms, and that its present arms were probably installed in Portsmouth later in the eighteenth century. In actuality, this chair could have been made by one of several Portsmouth craftsmen. The carving on the crest differs significantly from that on seating more convincingly associated with Gaines, and the turnings have no relation to those associated with his shop tradition. Other than the feet, the only detail suggesting a connection between this chair and the Gaines shop is the gouge work inside the large C-scrolls of the crest. This occurs on Gaines chairs but is too generic to be meaningful. Similar gouge work occurs on the crests of banister-back chairs from Salem, Massachusetts.[13]

Several Portsmouth chairs with vasiform banisters that were not made in the shop of John Gaines III are cited in Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks of the New Hampshire Seacoast. One variant (fig. 25) has many of the same features as a Gaines chair but differs in having rear posts with a less sinuous ogee profile, a narrower banister augmented with small spurs, Spanish feet with laminated toes, and more finished rear surfaces (fig. 26). Nevertheless, the similarities between this chair and Gaines seating suggest that its maker may have worked in Gaines’s shop or, at the very least, been influenced by comparable London or Boston prototypes. Another Portsmouth chair displays even stronger affinities with John Gaines III’s work (fig. 27); however, its cut-card leafage and lower back suggest that it might date after Gaines’s death in 1743. Gaines could have been producing chairs inspired by so-called Queen Anne designs only from the mid-1720s until his death, a relatively short time for him to have made the approximately thirty-five examples attributed to him.[14]

A more severe model of Portsmouth chair may have been based on London seating in the “Chinese scholars’ taste” (figs. 28, 29). On these chairs, the heels are set too far forward, giving the seating a sway-backed appearance (fig. 29) that differs from the front-leaning aspect of most Gaines products. Some contemporary Boston examples display similar design defects, reinforcing the theory that they influenced Portsmouth work. The frames on the chairs illustrated in figures 28 and 29 appear narrow when viewed from the side, and their banisters are thin and did not require chamfers to lighten and sharpen their appearance. Because “India-backed” seating was fashionable in London from 1715 to 1730, these chairs may have been as esteemed as the more visually ostentatious examples associated with the Gaines shops.[15]

Other Portsmouth Seating

Several groups of chairs demonstrate that the market for seating in Portsmouth was much more diverse than previously thought. One group of banister backs with a distinctive sunburst, or fan, crest has long been associated with that town. Many of these chairs have simple scrolled arms with a drooping front volute. This same arm appears on other Portsmouth seating, most notably chairs with either scalloped crests or oak leaf crests.[16]

Four chairs with arched crests flanked by spurs and robust, detailed turnings probably date 1740–1775. These chairs are heavier in weight than later variants and display two different kinds of Spanish feet. An armchair with elaborate baluster-shaped turnings has a Spanish foot without laminated toes and undercut ankles (fig. 30). The foot carving consists of four flutes cut with a relatively steep-sided gouge. The scroll arms have moldings on the upper sides and drooping front terminals with softly modeled volutes on the sides. The carved fan on the crest surrounds a half-round reserve with cross-hatching and three pointed leaves. A more elaborate version of this crest design can be seen on the armchair illustrated in figure 31. Although its feet have suffered losses, they appear to have been carved like those on the preceding example (fig. 30). A third armchair (fig. 32) and a related side chair (fig. 33) are somewhat simpler in detail but display a more sculptural version of the Spanish foot, also cut entirely from the stock of the front posts. The ankles of the feet are undercut, and the toes extend well beyond the squares of the posts above. Their dramatic sweep is similar to that of the more fully developed carved feet associated with John Gaines III.[17]

Another important genre of Portsmouth seating is represented by an armchair that belonged to Sir William Pepperell (1696–1759) of Kittery, Maine (fig. 34). The back features an extremely rare variant of the so-called split spindle—a bilaterally symmetrical, baluster-shaped turning with no relationship to the turned columns on the rear posts—and plump finials with large buttons at the top. The arms have a pronounced drooping grip, like those of the fan-crested examples (figs. 30-32), but they are excessively long and extend well beyond the front posts. The front stretcher is not diagnostic as far as origin is concerned, but the form and “bipartite” arrangement of the turned elements on the side stretchers are more typical of Portsmouth work than that associated with other New England chair-making traditions. Although the Pepperell armchair’s feet are missing, their form can be extrapolated from another example by the same maker (fig. 35). The arms of the latter are more normal in length, and the profile of the columnar section of the banisters echoes the turnings on the rear posts. The carving on the crests of both chairs is crude, with shading cuts that barely follow the flow of the design (see fig. 78 in appendix).[18]

Other chairs from the same shop have superior carving (fig. 36), similar turnings, and elegant Spanish feet cut from the solid. The crests of these chairs (see fig. 79 in appendix) are unusual in having leaves that drop from the volutes of a C-scroll in the center and rise from intersecting scrollwork on either side. The descending leaves bear a strong resemblance to carving attributed to Joseph Davis of Portsmouth. The close relationship between the feet on this chair and those on seating by John Gaines III suggests that the latter may have subcontracted carving to Davis.[19]

Two simple banister-back chairs with turned feet (figs. 37, 38) share traits with other Portsmouth seating, particularly the crests with prominent spurs at the sides (figs. 30-33). Hundreds of chairs of this type, usually painted black, were exported from Portsmouth between 1725 and the Revolution. Little is known about comparably simple slat-back chairs, which were presumably also made in considerable numbers.

The Gaines Shops and Chair Making in Ipswich

With all the attention devoted to Portsmouth Gaines chairs, few scholars have speculated about what John Gaines II and Thomas Gaines were making in Ipswich, Massachusetts. One might get the impression from previous discussions of John Gaines III that he moved to Portsmouth in 1724 because he was an enterprising young man, whereas his father and brother remained in Ipswich because they were comfortable in a provincial backwater. This view of the Gaines artisans and of the town of Ipswich itself is anachronistic. Ipswich paid the second-highest town tax in Massachusetts until the 1740s. Like every port in Essex County, including rivals Marblehead, Salem, Beverly, Manchester, Gloucester, and Newbury, Ipswich had an active harbor, at the mouth of the Ipswich River, where it flows into Plum Island Sound. Merchants in all these Essex County towns were determined to break the hegemony of Boston merchants.[20]

The painted overmantel panel illustrated in figure 39 depicts the cove between the Great Neck and the Little Neck, where Ipswich’s cod-fishing industry was concentrated. In the foreground are oceangoing schooners, and in the background are salted fish flakes drying on a hill and warehouses on piers for securing quintals of dried cod. The same facilities probably were used for other mercantile activities as well. Shipping manifests indicate that local cabinetmakers and chair makers exported crates of furniture from the town. Crated furniture may have been brought down the river in lighters (one is shown in the painting) or in flat-bottomed hay barges known as “gundalows,” before being transferred to the holds of oceangoing vessels.[21]

An account book maintained by John Gaines II and Thomas Gaines covering the years 1707 to 1762 has been a primary source for most of the publications pertaining to those craftsmen since the mid-1950s. The book reputedly descended in the Appleton family along with a side chair (fig. 40). This chair is unquestionably from the same shop as the examples illustrated in figure 41. All have lightweight frames, relatively debased turnings, and rudimentary carved crests. Although some scholars have suggested that the carving on these chairs is related to that on Portsmouth examples from the shop of John Gaines III, side-by-side comparisons indicate that is not the case. The Ipswich chairs are distinctive localized interpretations of Boston banister-back chairs with highly stylized crests. While it is possible that John Gaines II made the chair that descended with his account book and the example illustrated in figure 40, that scenario seems unlikely. The joinery and carving of those objects is less skillful than that associated with the Portsmouth shop of John III, who had previously trained and worked with his father.[22]

The history of the side chair illustrated in figure 42 is less clear, but it may also be an Ipswich example. It has a dramatic scrolled crest with leaves rising from and dropping below the ogee sections, a straight-sided banister reminiscent of those on some Boston and London chairs, a seat with over-the-rail upholstery, and square-sectioned cabriole legs with leaf cuffs, flat scalloped stretchers, and Spanish feet. While several of these features occur in Boston seating, they have never been found united in one chair. The crest carving and rough rear surfaces of the frame resemble Portsmouth work, but the similarities are not sufficient to support any conclusions.[23]

The quandary of where and by whom this extraordinary chair was made is deepened by the existence of plausible prototypes, most notably a set of London cane seating owned by Portsmouth merchant Tobias Lear III (1706–1751) (fig. 43). The Lear chairs provide exact precedents for the shape and beading of the flat stretchers, the cylindrical turnings on the lower portions of the back posts, and the sharp knop and elaborate stops of the rear stretcher. The elaborate crest and cuffs of the chair illustrated in figure 42 may be an individual conceit, since they deviate from the design of the Lear chairs and are conceptually more ambitious than those on contemporary Boston examples. Chairs with similar straight-sided, ogee banisters, or “India backs” were fashionable in England and her colonies. Thomas Gaines used that term to describe a set of chairs he made in 1759.[24]

Boston Banister-Back Chairs

The diffusion model for banister-back chair design in New England has traditionally centered on Boston, despite the fact that little has been published on Boston examples of that form. A plausible argument for attributing several banister-back chairs to Boston can be made by comparing them with leather chairs from that city. Furniture historian Benno M. Forman asserted that both types of seating were made in the same shops, and early banister-back examples with accomplished joinery, turning, and carving suggest that he was correct (fig. 44).[25]

The crest rail carving on the chair illustrated in figure 44 conforms to a familiar pattern (fig. 45), featuring vertically oriented foliage flanked by large, opposing C-scrolls with loosely wound volutes and connecting leafage. Cutouts lighten and accentuate the design, but in terms of overall workmanship, the modeling and shading are relatively stereotyped. Crests of this general type influenced Essex County and Portsmouth seating more than the turnings on Boston chair frames. In other New England ports, chair makers developed their own variations on Boston crest designs to distinguish their work from that of metropolitan competitors. Some Boston chair makers purchased carved crests, arms, and turned components from specialists, whereas others did most, or all, of their work in-house. Chair makers in other ports did the same, although the use of piecework in manufacture must have been more common in Boston. The distribution of Boston banister-back chairs of this caliber was relatively wide. An armchair (fig. 46) from the shop that made the example illustrated in figure 44 belonged to William Pepperell. His chair differs in that the front stretcher is turned rather than carved.[26]

A Boston side chair with a crest similar to those on the armchairs is distinguished by having front posts with turned tops and baluster-and-ball feet (fig. 47). It also has rectangular side and rear stretchers. Later banister-back chairs from Boston probably had turned stretchers, and more work is needed to separate them from other eastern Massachusetts examples.[27]

Salem Banister-Back Chairs

Histories associated with a distinctive group of banister-back chairs, traditionally ascribed to the North Shore, support a more specific attribution to Salem. Although only three men were referred to as “chair-makers” in a 1762 list of craftsmen in that town, there is no reason to assume that artisans described as “shop joiners” did not also make chairs. In urban areas, banister-backed chairs and other seating forms were often assembled from components purchased from specialists, which could include turners, joiners, and carvers.[28]

Most banister-back chairs were probably made in sets or multiples of six. Horizontal components were produced in large numbers well ahead of assembly, partly because it was cost-effective and partly because construction depended on inserting dry turned components into wet, or at least somewhat green, posts. Whether plain or carved, crests also had to dry before assembly. Presumably, carvers made crests or stretchers of the same pattern sequentially and in large numbers, since that process would have been much more efficient than shifting from one pattern to another. As was the case with specialist turners, carvers made components to order for some chair makers, while offering standard piecework that others could modify to fit their frames. Under the latter scenario, identical stretchers, turned rails, or carving could appear on seating by different makers. Because posts needed to be green at the time of assembly, they were made last. To accommodate the demand for turned and joined seating, regional sawmills must have maintained substantial stocks of poplar, which was the preferred wood for posts that were intended to receive paint. The soft, even grain of poplar made it ideal for sawing, turning, and mortising. As these assembly procedures suggest, chairs may have been assembled with parts made by several tradesmen over an extended period of time.[29]

An early armchair that descended in the Devereux family of Marblehead, Massachusetts, exhibits many traits associated with Salem seating (fig. 48). The stretchers are the most distinctive components, having bilaterally symmetrical balusters with large bulbous elements that transition abruptly into sharply tapered columns like those on some Boston cane chairs. In Salem, the use of molded and split, turned banisters was coeval. The moldings on the banisters of the Devereux chair are reminiscent of those associated with joiners John Symonds (d. 1671) and his son James (1633–1714), who were active in Salem during the seventeenth century. Later members of their family, including Thomas Symonds (d. 1758) and his son Benjamin (1714–1779), were involved in the furniture-making trades and might have made chairs like the Devereux example or at least furnished parts for them.[30]

Although the crests of most Salem chairs conform to a familiar pattern, which consists of vertically oriented leafage in the center and opposing scrolls on either side, several different hands are discernible. The carver of the Devereux chair shaded his leaves with a conventional, small gouge (fig. 49) rather than a more steep-sided veiner or V-shaped parting tool, which were preferred by some of his contemporaries. On the leaves connecting the outer scroll volutes, he made the shading cuts perpendicular to the flow. In later rococo carving, perpendicular fluting was often done to represent the back of a leaf, but on this chair it appears to be an individual idiosyncrasy. The same can be said of the peculiar fluting on the top edges of the outer leaves, although this detail does appear on some Boston crests (fig. 50).

The Devereux armchair and a contemporaneous example from the same shop illustrate the range of options available to Salem consumers: turned or molded banisters; stretchers with a variety of details and arrangements; arms with different sweeps, moldings, and terminals; and crests by different carvers. Although the crest designs of the armchair illustrated in figure 51 and the Devereux example are similar, the former has flatter C-scrolls and paired shading cuts that diverge in an awkward manner (fig. 52).[31]

A side chair with strong affinities to the Devereux armchair (fig. 48) has a crest by yet another carver, a plain stay rail with a molded lower edge, and seat blocks at the juncture with the front posts (fig. 53). The distinctive turnings on the front posts may have been derived from English caned chairs, as they have known precedents in contemporary Boston seating. A second side chair (fig. 54) is more closely allied to the armchair illustrated in figure 51. Both seating forms have similar rear posts, spindles, and stay rails, and their carved crests appear to be by the same hand. The painted decoration on the side chair is similar to that on London cane chairs (fig. 55) and may be original. Not all Salem banister-back side chairs are as elaborate as the examples illustrated in figures 53 and 54. Indeed, some local artisans appear to have used relatively plain stretchers (fig. 56), crests (fig. 57), and stay rails to keep prices in check and compete with Boston chair makers and other regional rivals. Later banister-back chairs that differ little from their earlier counterparts attest to the success of Salem chair makers in satisfying consumer demand. The armchair illustrated in figure 58 has features introduced during the 1710s that remained fashionable into the 1760s.[32]

Another school of banister-back chairs may be from Salem, but its attribution is a bit more tenuous. Most examples have eccentric details in conjunction with straight-molded banisters, severely tapering columnar turnings, and Spanish feet carved from the solid with a turned molding at the ankle. Some of the other turnings on these chairs are unusual by New England standards, including the simplified columns on the rear posts, which resemble those of English cane chairs. An armchair that was modified in the nineteenth century with Eastlake incising and yellow highlights displays a flat crest with a plumed flourish and volutes on the ends (fig. 59). No immediate New England precedent for this design is known, unless it represents an abstracted version of the crests on some Boston cane chairs. A side chair (fig. 60) has many of the same attributes, although the top of the crest is simplified into what looks like a pedestal. The maker used the blocked, rushed form of seat. Another armchair (fig. 61) has an unprecedented triple-swept, molded crest with a tight, narrow version of what American furniture scholars call a “saddle.” Again, no immediate local precedent for this exaggerated feature is known, but it may reflect a stylish, mannered London precedent. The armchair illustrated in figure 61 also has a straight, molded stay rail, yet another tie to the main Salem tradition.[33]

Newbury Banister-Back Chairs

Furniture scholar John D. Vander Sande has identified a group of banister-back chairs made in Newbury, a major Essex County port to the north of Salem, on the other side of Ipswich and the Cape Ann Peninsula. Newbury had two ports, the original one on the shallow Parker River and a later one on the larger Merrimac River. Both these ports supported facilities much like those in the overmantel painting of Ipswich harbor (fig. 39).

Most of the turnings on Newbury banister backs conform to Boston patterns. The armchair illustrated in figure 62 displays some of these metropolitan features, most apparent in the bilaterally symmetrical balusters of the stretchers. A second armchair (fig. 63) has more idiosyncratic turnings as well as uncarved arms that are reminiscent of work from nearby Portsmouth. The feet on the armchair illustrated in figure 62 are carved from the solid, with a distinct, curved undercut to the two rear surfaces.

What sets these Newbury chairs apart from other local regions is their carving, which appears to have been done by the chair maker rather than by a specialist. His earlier crests (figs. 86, 87 in appendix) have stylized central leaves that rise only slightly higher than the finials and rear surfaces that are counter-chamfered with a small-diameter gouge (fig. 87 in appendix). Most carvers used a larger tool for that type of work and made their cuts with considerably less precision and regimentation.

Later crests by this Newbury maker are varied in design and execution. Some have leaves that are spiky and stylized (fig. 64), some have leaves that are more naturalistically modeled and shaded (fig. 65), and some have nothing more than a scalloped upper edge to evoke the shape of carved variants (fig. 66).[34]

Boston Banister-Back Seating in the Manner of Boston Cane Chairs

The chair illustrated in figure 67 is one of three Boston examples with “crook’d,” or ogee, banisters bearing original caners’ marks. The molded stiles and crests on these chairs and other seating in the so-called “I” group are based on imported London seating. English furniture scholar Adam Bowett has documented a set of London chairs with similar stiles and crests that appears to date 1715–1717; thus, Boston versions were probably being made by the early 1720s.[35]

Several joined chairs inspired by Boston caned seating are known. The chair illustrated in figure 68 has a molded back and turned stretchers derived from cane chairs, combined with a vasiform banister and squared, incised cabriole legs with Spanish feet. Although scholars have been reluctant to date Boston seating with vasiform banisters much before the late 1720s, this chair could date circa 1725. A heavier armchair, presumably made between 1735 and 1745, has the same banister profile, combined with details taken from leather chairs (fig. 69). The relationship of this type of seating to Gaines chairs is unclear. The problem resides in determining if both the Boston chair makers and John Gaines III relied on imported English prototypes, as opposed to an older, diffusionist model that asserts Boston origins for all eastern Massachusetts seating. In any case, the existence of Boston seating sharing some traits with Gaines chairs renders the idea that John Gaines III invented his designs doubtful.

The history of Massachusetts and New Hampshire banister-back seating from the first half of the eighteenth century is only beginning to come into focus. Numerous Essex County chairs with varied carving and frame treatments suggest that much more research is needed (figs. 70, 71). It is hoped that this article will inspire other scholars to do fieldwork, document stair balusters as a basis for identifying regional chair turnings, and publish monographs on local chair-making traditions. Only then will we begin to understand the complexities of seating styles in New England.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Kimberly Alexander, Patrick Alley, Mark Anderson, Gavin Ashworth, Doug Baz, Luke Beckerdite, Ronald Bourgeault, Derin Bray, Rev. Rebecca Brown, Jean Burks, Katherine Chaison, Wendy Cooper, Andrew Davis, Jeanne Gable, James L. Garvin, Bethany Groff, Mrs. Constance Godfrey, Norman and Mary Gronning, Joseph W. Hammond, Brock Jobe, Jane Kellar, Tom Kelleher, Judith Kelz, Leigh Keno, Mr. and Mrs. Donald Koleman, Richard Kyllo, Jim Lahar, Ethan Lasser, Jim Leonard, Arthur Liverant, Cindy Macky, Giacomo Mirabella, Susan Nelson, Susan Newton, Martha Oaks, Elizabeth Peterson, Jonathan Prown, Adrienne Sage, Nancy Sazama, Irving and Anita Schorsch, Andrew Spahr, Tom Stauffer, Elizabeth Tibbetts, Jonathan and Paige Trace, Harry Mack Truax II, John and Marie Vander Sande, Tara Vose, Kemble Widmer, Jay Williamson, and Mr. and Mrs. Martin Wunsch.

Appendix of Crest Details

The numbers in these captions (figs. 72-91) refer to the figures of the overall images in this article.

For more on early Boston seating, see Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988); Roger Gonzales and Daniel Putnam Brown Jr., “Boston and New York Leather Chairs: A Reappraisal,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 175–94; Joan Barzilay Freund and Leigh Keno, “The Making and Marketing of Boston Seating Furniture in the Late Baroque Style,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998), pp. 1–40; and Glenn Adamson, “The Politics of the Caned Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 174–206.

The most recent evaluation of the Gaines attributions is in Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1993), pp. 47, 48, 295–300.

The set of four chairs remained in the Brewster family until they were sold at auction (Northeast Auctions, New Hampshire Auction, Manchester, New Hampshire, November 7–8, 1998, lots 1097, 1098). One chair is in the Winterthur Museum, one is in the Strawbery Banke Museum, and two are in a private collection.

For the history of the armchair illustrated in fig. 3, see Jobe, ed., Portsmouth Furniture, pp. 295–97.

For a heavily restored “Gaines” chair, see Frances Gruber Safford, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 1, Early Colonial Period: The Seventeenth-Century and William and Mary Styles (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007), pp. 358–60, no. 137. Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “Furniture Fakes from the Chipstone Collection,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 65–67.

The use of nails to attach carving patterns is discussed in Luke Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” in New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno Forman, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 132–33.

For an overall view of the armchair, see Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1997), pp. 33–35, no. 18. For illustrations of English chairs with protruding volutes on the grips, see Adam Bowett, English Furniture, 1660–1714, from Charles II to Queen Anne (Woodbridge, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2002), pls. 8:8, 8:18, 8:22, 8:28, 8:57. For northern Italian chairs with exaggerated arms, see G. Morazzoni, Il mobile veneziano del 1700, 2 vols. (Milan: Görlich-Editore, 1958), 1: pls. 18b, 21, 34a, 41, 43, 2: pl. 283.

A few Gaines chairs have conventionally woven seats. The armchair illustrated in fig. 3 is the only surviving example with most of its original retaining strips.

A Boston low-backed chair with triple-swept crest is illustrated in Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 306–8. For London seating of the 1710–1720 period, see Bowett, English Furniture, 1660–1714, pp. 230–73; and Adam Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture, 1715–1740 (Woodbridge, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2009), pp. 144–96.

The Boston chair illustrated in fig. 20 was attributed to “Boston, northeastern Massachusetts, or coastal New Hampshire” in Richards and Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, pp. 8–9, no. 2. Formerly, these chairs were attributed to Newport, Rhode Island, on the basis of an example at the Newport Historical Society that belonged to William Ellery of Newport. For a reattribution to Boston, see Erik K. Gronning and Dennis Carr, “Rhode Island Gateleg Tables,” Antiques 165, no. 5 (May 2004): 122–27.

Objects attributed to Davis are discussed in Brock Jobe, “An Introduction to Portsmouth Furniture of the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” in Jobe, ed., Essays in Memory of Benno Forman, pp. 166–78; and Jobe, ed., Portsmouth Furniture, pp. 46, 47, 128–33, 234–36.

This chair is illustrated in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), pp. 110–11, no. 46, where it was attributed to John Gaines III. Luke Beckerdite has proposed that the carving on this object is by the same hand that was responsible for the ornament on a dressing table and altar table attributed to Joseph Davis (see n. 11 above.) A chair in the Art Institute of Chicago has an atypical “Gaines” crest rail and elaborate carving (Judith A. Barter, Kimberly Rhodes, and Seth Thayer, American Arts at the Art Institute of Chicago: From Colonial Times to World War I [New York: Hudson Hill Press, for the Art Institute of Chicago, 1998], p. 62, no. 11).

Safford, Early Colonial Period, pp. 81–82, no. 29. Several “Gaines” chairs with carved crests are heavily restored (see Richards and Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, pp. 33–34, no. 18). Some examples that have recently appeared in the marketplace are almost certainly early-twentieth-century fakes.

Jobe, ed., Portsmouth Furniture, pp. 48–49, 218–20, 285–91, 301–5. Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 21, 2006, lot 402. Northeast Auctions, The Dinah and Stephen Lefkowitz Folk Art Collection, Portsmouth, N.H., August 3, 2007, lot 750. The assessment of thirty-five chairs is determined from the number published in previous literature and new discoveries made by the authors.

The set of chairs illustrated in fig. 28 was illustrated in Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan Co., 1928), 2: nos. 2103, 2104. For India-backed seating in England, see Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture, pp. 156–60; and Adam Bowett, “The India-backed Chair, 1715–40,” Apollo 491 (January 2003): 3–9.

For variants, see Jobe, ed., Portsmouth Furniture, pp. 48–49, 285–91.

The authors thank Derin Bray for calling the Shelburne armchair to their attention. Other closely related chairs have been published in F. W. Fussenich advertisement, Antiques 16, no. 6 (December 1929): 467; Anderson Galleries, Collection of the Late Thomas B. Clarke, December 2–5, 1931, lot 626; Rosella V. Becker advertisement, Antiques 57, no. 4 (April 1950): 293; Tillou Gallery advertisement, Antiques 88, no. 6 (December 1965): 799; Millard F. Rogers Jr., “Living with Antiques: Millbach, the Ohio Home of Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Bugbee,” Antiques 150, no. 3 (September 1966): 351; Tillou Gallery advertisement, Antiques 108, no. 1 (January 1975): 85; Patricia E. Kane, 300 Years of American Seating Furniture: Chairs and Beds from the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975), pp. 69–70, nos. 48, 49; Sotheby’s, The Howard and Jean Lipman Collection of Important American Folk Art & Painted Furniture: The Property of the Museum of American Folk Art, New York, November 14, 1981, lot 356; Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone, pp. 164–65, no. 73; Christopher P. Monkhouse and Thomas S. Michie, American Furniture in Pendleton House (Providence: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1986), p. 152, no. 92; James D. Julia Auctions, Annual Samoset 2003 Antiques & Fine Art Auction, Fairfield, Maine, August 20, 2003, lot 608; David Hewett, “Action Galore on the Floor at NHADA’s Annual Show,” Maine Antique Digest (November 2006): C2; Pook and Pook, Inc., Furniture, Art, & Accessories, Dowingtown, Pa., May 11–12, 2007, lot 85; James D. Julia Auctions, Annual Winter Antique & Fine Art Auction, Fairfield, Maine, January 31, 2008, lot 874; Northeast Auctions, The M. Austin & Jill R. Fine Collection, Portsmouth, N.H., August 7, 2010, lot 603; and Northeast Auctions, Annual Summer Americana Auction, Portsmouth, N.H., August 6–8, 2010, lot 793.

Sir William Pepperell dominated much of the economy of Portsmouth. The chair in fig. 35 sold in Sotheby’s, Important Americana from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Adolph Henry Meyer, New York, January 20, 1996, lot 43.

Safford, Early Colonial Period, pp. 83–85, no. 30. For Joseph Davis, see n. 11 above.

Research by Susan S. Nelson (“Capt. Abraham Knowlton, Joiner, and the Seminal Woodworkers of Ipswich, Massachusetts,” in Rural New England Furniture: People, Place, and Production, edited by Peter Benes [Boston: University Press and Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, 2000], pp. 42–59) and Kemble Widmer II and Judy Anderson (“Furniture from Marblehead, Massachusetts,” Antiques 163, no. 5 [May 2003]: 96–105) suggests that the economic leverage exerted by artisans in Essex County towns was considerable during the eighteenth century. See also Daniel Vickers, Farmers and Fishermen: Two Centuries of Work in Essex County, Massachusetts, 1630–1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

The Ipswich overmantel is discussed in T. Frank Waters, Jeffrey’s Neck and the Way Leading Thereto with Notes on Little Neck (Salem, Mass.: Salem Press, 1912), pp. 7, 58, 59.

An account of the discovery of the Gaines account book and the chair that descended with it in the Appleton family of Ipswich is in Albert Sack, “Tales of Portsmouth Furniture,” in Piscataqua Decorative Arts Society 2002–2003 Lecture Series, vol. 1 (Portsmouth, N.H.: Piscataqua Decorative Arts Society, 2004), pp. 31–32. The side chair is illustrated in Beulah E. Larson, “Living with Antiques: A Salt-Box in Tulsa, Oklahoma,” Antiques 94, no. 2 (August 1968): 210; and Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 19–21, 1996, lot 1385. Earlier articles about Gaines chairs include Stephen Decatur, “George and John Gaines of Portsmouth, New Hampshire,” American Collector 7, no. 10 (November 1938): 6–7; Helen Comstock, “An Ipswich Account Book, 1707–1762,” Antiques 66, no. 3 (September 1954): 188–92; and Helen Comstock, “Spanish-Foot Furniture,” Antiques 71, no. 1 (January 1957): 58–61. Robert E. P. Hendrick, “John Gaines II and Thomas Gaines I, ‘Turners’ of Ipswich, Massachusetts” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1964). Hendrick illustrated the banister-back chair that descended with the account book along with a very similar pair of banister backs in the collection of the Ipswich Historical Society (fig. 40 in this article). He attributed all three chairs to the Ipswich Gaines shop and suggested that the pair may have descended in the Appleton family. No accession documents or other records at the Ipswich Historical Society support that theory (see correspondence between Hendricks and Elisabeth Newton dating from the early 1960s). Sack, “Tales of Portsmouth Furniture,” p. 32: “This armchair [fig. 30] is quite similar to a side chair that came with the Gaines account book from the Appleton family—a banister back chair with a carved crest and Spanish feet.” Contrary to what Sack wrote, the banister back does not have Spanish feet, and the carving has no relationship to that of chairs attributed to John Gaines III of Portsmouth.

The chair illustrated in fig. 42 has been in the collection of the Ipswich Historical Society for many years but was never identified in accession records.

Tobias Lear III was married in 1733 and built his house in Portsmouth circa 1740. Adamson, “Politics of the Caned Chair,” pp. 186, 195, figs. 11, 27. The front feet of the chair illustrated in Wallace Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, 1620–1720 (Boston: Marshall Jones Co., 1921), p. 246, are restored, and it is unclear if the set had Spanish feet originally. Wallace Nutting may have acquired his chair when he owned the Wentworth-Gardner House in Portsmouth, which is immediately adjacent to the Tobias Lear House. Nutting does not appear to have been aware of the history of the Lear cane chairs. Hendrick, “John Gaines II and Thomas Gaines I,” p. 107, cites the “India back” reference. For another related side chair, see Gordon Russell, The Things We See: Furniture, 2nd ed. (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1953), p. 14, no. 26.

Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 281–356; and Gonzales and Brown, “Boston and New York Leather Chairs,” passim. For an image of the chair illustrated in fig. 44 before restoration, see Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), pp. 40–41, fig. 463. This chair sold as lot 1036 in Northeast Auctions, Annual Americana Auction, Portsmouth, N.H., August 3–5, 2006. For a Boston armchair with nearly identical turnings, carving, and proportions, see Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 341, fig. 180.

Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1984), pp. 325–28, no. 85. Benno M. Forman “Salem Tradesmen and Craftsmen Circa 1762,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 107, no. 1 (January 1971): 62–81.

Typically chairs with Spanish feet and turned stretchers have a blocked rush seat that sits on top of the legs.

Jobe and Kaye, New England Furniture, pp. 325–28, no. 85; Forman “Salem Tradesmen,” pp. 62–81.

For more on the production of this type of seating, see Benno M. Forman, “Delaware Valley ‘Crookt Foot’ and Slat-Back Chairs: The Fussell-Savery Connection,” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 41–64; and Robert F. Trent, Hearts and Crowns: Folk Chairs of the Connecticut Coast, 1720–1840 (New Haven, Conn.: New Haven Colony Historical Society, 1977), pp. 25–29, 63–66.

Forman, “Salem Tradesmen,” pp. 35–36. Three other Salem banister-back armchairs survive with a crest executed by the carver of the example illustrated in fig. 83 (David B. Warren, Michael K. Brown, Elizabeth Ann Coleman, and Emily Ballew Neff, American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection [Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1998], p. 8, no. F14; The Decorative Arts of New Hampshire: 1725–1825, edited by Charles E. Buckley [Manchester, N.H.: Currier Gallery of Art, 1964], no. 3; Northeast Auctions, New Hampshire Auction, Portsmouth, N.H., August 2–3, 2002, lot 284).

For decades this chair was attributed to New York (V. Isabelle Miller, Furniture by New York Cabinetmakers: 1650–1860 [New York: Museum of the City of New York, 1956], pp. 19–20, no. 19; and Robert Bishop, Centuries and Styles of the American Chair: 1640–1970 [New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1972], p. 55, no. 53). Elmer C. Howe advertised the armchair illustrated in fig. 58 in Antiques 11, no. 6 (June 1927): 448. He had shops in both Boston and Marblehead, Massachusetts.

While counterintuitive, it is possible that the change from molded to turned banisters was part of this simplification.

Jobe and Kaye, New England Furniture, pp. 328–30, no. 86, note the similarities between the two shop traditions and cite several of the same objects. Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 2: 2089.

For another chair nearly identical to the example shown in fig. 64, see Robert F. Trent’s catalogue entry on pp. 70–72, no. 21, in American Furniture with Related Decorative Arts: 1660–1830, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1991).

Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 229–45, 258–67. For an additional example, see Adamson, “The Politics of the Cane Chair,” p. 174, fig. 1. The chair illustrated in fig. 67 sold as lot 229 in Skinner, American Furniture & Decorative Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, February 18, 2007. Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture, pp. 157–58, fig. 4:24.