Cradle, southeastern Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Red oak, white pine, and maple. H. 32", W. 33 3/4", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cradle illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, southeastern Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Red and white oak. H. 28", W. 42", D. 20". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Hall Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cradle, southeastern Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Oak and white pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Historic New England.)

Cradle, southeastern Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Red oak and white pine. H. 33 1/4", W. 33 5/8", D. 25 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England; photo, Peter Harholdt.)

Cradle, southeastern Massachusetts, 1680–1700. Maple and white pine. H. 31 3/4", W. 36 3/8", D. 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Hall Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cradle, North Devon, England, 1698. Lead-glazed earthenware. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Large quantities of North Devon sgraffito ware were exported to the American colonies, but very few examples survive outside archaeological collections.

Detail of the woman’s head incised on one end of the cradle illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Henry Vanhorn Shop Sign, attributed to Edward Hicks, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Oil and pencil on yellow poplar. 17 1/8" x 54 5/16". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase.)

“Our Baby’s Death, Swedish Section: M.B.”, Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876. (Courtesy, Print and Picture Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia, Centennial Collection.)

“THIS GIDDY GLOBE/ THE MAYFLOWER,” Life Magazine 2, no. 41 (October 11, 1883): 171.

Log Cabin in “Ye olden time,” 1876. (Courtesy, Print and Picture Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia, Centennial Collection.)

“New England Kitchen,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition, 1876. Wood engraving. (Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

Log Cabin Studies, “Cat’s Cradle,” 1876. (Courtesy, Print and Picture Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia, Centennial Collection.)

Photograph showing part of the Wallace Nutting Collection of Early American Furniture, Hartford, Connecticut, ca. 1928. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum.)

Photograph showing part of the Wallace Nutting Collection of Early American Furniture, Hartford, Connecticut, ca. 1935. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum.)

Exhibit section titled “Rare Forms of the Seventeenth Century,” Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, 2000. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum.)

In the 1908 preface to his novella The Aspern Papers, Henry James ruminates on his ideal relationship to the past, describing his “delight in a palpable imaginable visitable past . . . the marks and signs of a world we may reach over to as by making a long arm we grasp an object at the other end of our own table.” In evoking an object, James highlights the fundamental role physical things play in our conception of the intangible past. Indeed, objects—paintings, sculpture, furniture, ceramics—often serve as conduits between points in time, interpreted as evidence and expressions of history passed. When a design object is preserved through disuse, it becomes a window into the past rather than a functional thing, dramatically changing its relationship to those who come in contact with it. Even as an object is venerated as an exemplar of a single moment, it continues to exist in innumerable times. The question then arises, to what extent are objects timeless rather than chronologically grounded? Do they exist as emblems of the time in which they were made, objects of use being used? Or are they best understood ahistorically through criteria of craftsmanship and beauty? These two frameworks—often in tension with one another but never mutually exclusive—represent alternative ways of thinking about the display and study of historical objects. What is rarely discussed, and what remains, is the question of the intervening years in an object’s life. This question is particularly apt when we examine objects and works of art that became part of the system of public display that emerged in the nineteenth century.[1]

These alternative modes of interpretation can be applied to a singular object and its history: a cradle made in Plymouth, Massachusetts, between 1660 and 1700 (figs. 1, 2). In the nineteenth century, it was known as the Fuller cradle because tradition maintained that Dr. Samuel Fuller (1580–1633) brought it from England on the Mayflower. The cradle passed through generations of Plymouth families until it was first exhibited in a re-created colonial-era kitchen at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition. In the early 1920s collector Wallace Nutting purchased the cradle to use in his business enterprises. It was at this time that the English origin was disproved through wood analysis, and the cradle became a symbol of early American artistry. The cradle was subsequently given to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, where it now resides. In this essay, I consider the cradle within the early history of European settlement in Massachusetts and in the context of the metaphoric understanding of cradles. I then examine the cradle’s hitherto neglected role at the centennial and its subsequent history in the hands of a colonial revival tastemaker and a venerated museum collection of early American decorative arts. These interpretations are grounded in close observation of the cradle and analysis of documents, imagery, and the larger history of the cradle as a furniture form.[2]

The cradle is constructed of red oak, white pine, and maple and is thirty-two inches in height, which allowed an adult to rock it without bending down. It is deep and straight-walled, and its construction can be thought of as four pine sideboards and four oak end boards floating within the framing embrace of oak stiles and rails. The rockers, which are replacements, were destroyed by 1876, likely owing to use, and re-created in the early twentieth century. The cradle was meant to be not only sturdy, solid, and long lasting but also ornamental and beautiful, thus protecting its human contents while providing a source of pleasure. Indeed, early American inventories reveal that although cradles appear regularly in households with substantial property, joined cradles were a rare and specialized furniture type reserved primarily for wealthy families. A disproportionate number of elaborately joined cradles survives from the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, perhaps because they were preserved as heirlooms.[3]

The decoration on the cradle is understated, subtle but rich. The stiles and rails have scratch-stock channel moldings and chamfers, and the panels are smoothly planed. The hood, or “top” as it was termed in eighteenth-century account books, is made of pine and has thumbnail-moldings at the sides and back. The perimeter of the top is decorated with a diamond guilloche, which has been partially worn away by the many hands that reached down to rock the cradle, and the side molding is decorated with notch carving. With its three sides, the gallery of maple spindles acts like a clerestory, providing both a sense of light, air, and visibility and actual light, air, and visibility (fig. 2). The maker of the cradle used short spindles for the back gallery and taller, more complex ones for the sides. He reserved the largest turnings, which are split half-columns, for the front of the hood, echoing the architectural practice of embedding decorative columns in exterior walls. Nail holes along the inside edge of the top, as well as a band of lighter-colored wood, suggest that there was originally a decorative molding attached here as well, enhancing the sense of an architectural entrance. At the other end of the cradle, turned finials provide rich punctuations to the silhouette. Their worn, nicked surfaces are evidence of the many hands and feet that reached out to rock the cradle.[4]

Most early American cradles relate to different types of chests. The simplest cradles were constructed with boards and nails like the box sections of six-board chests, whereas others had dovetailed corners or, in the earliest variants, panels trapped in mortise-and-tenoned frames. With its deep scratch-stock moldings, the Wadsworth Atheneum cradle most closely resembles a chest that descended in the Morton family of Plymouth (fig. 3). The sturdy construction and decoration of both objects, and the cradle in particular, signaled that they were secure containers for precious contents. During the seventeenth century infant mortality was high, even under the best of circumstances. Plymouth Colony was a religious experiment in a dangerous new world, and the cradle expressed its owners’ confidence in, but also their trepidation about, their future.[5]

As is the case with most pieces of seventeenth-century American furniture, the maker and original owner of the cradle have not been identified. During the early twentieth century, antiquarians attributed the cradle to John Alden (1599–1687), who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620, and Kenelm Winslow (1599–1672), who landed in Plymouth in 1629. Presumably, these men became associated with the cradle because both lived in Plymouth with Samuel Fuller and were active in woodworking trades, Alden as a cooper and Winslow as a joiner. The cradle appears to have been made between 1660 and 1700, which would eliminate Fuller as the original owner and make it contemporaneous with turned and joined examples that descended in the Hinckley family of Barnstable, Massachusetts (fig. 4), the Thatcher family of Yarmouth (fig. 5), and the Noyes family of Abington (fig. 6).[6]

From the seventeenth through the nineteenth century, changing ideas about child rearing produced ambivalent attitudes toward cradles, affecting the way they were used and valued. Until the late seventeenth century, cradles served as repositories for swaddled babies, rocked to sleep by nursemaids or family members, depending on the socioeconomic status of the family. Although swaddling continued well into the eighteenth century, the practice came to be viewed with increased skepticism and was eventually associated with neglectful child care that prevented infants from healthy physical activity and proper cleanliness. Cradles were criticized as well, both for their role in physically restraining babies and because rocking was viewed as unhealthy for the developing infant’s brain. Yet, even as child rearing methods changed and swaddling clothes were abandoned, the form took on new associations. Cradles remained a site of soothing sleep and play, engendering the bond between parents and their children.[7]

Activities associated with the cradle provided fodder for metaphoric uses of the word and its application to other objects that cradle, such as the framework used to support ships during construction. Instances of the word used in other contexts became increasingly common in the nineteenth century. This can be seen in the use of cradle as a symbolic noun suggestive of metaphoric gestation and birth, such as in the phrases “cradle of democracy” or “cradle of civilization.” It can also be used as a verb to describe secure but gentle embraces, such as “cradled in her arms.” These rich meanings are intimately related to the cradle as an object of use that is characterized by its specific function.

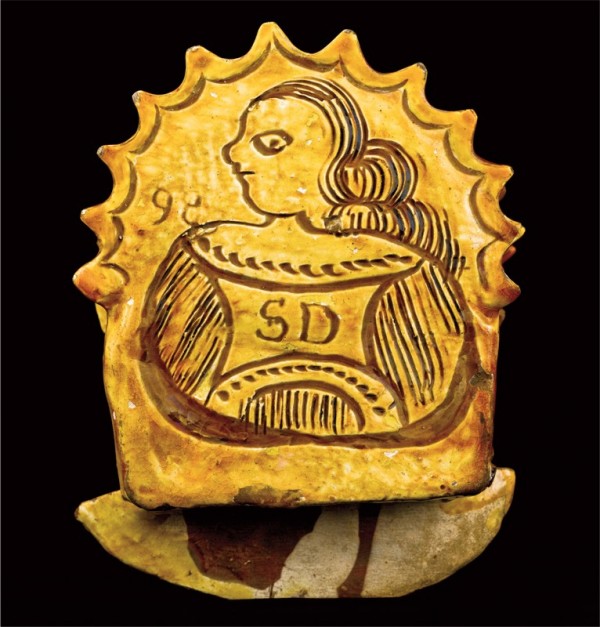

Similar connotations can also be seen in the use of the cradle as talisman. From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, new mothers were given miniature ceramic cradles that were valued as fertility charms, symbolic of the health of the mother and the baby (figs. 7, 8). Owners kept the cradles by the side of their beds, and well-meaning visitors filled them with small presents. These diminutive objects confirm that the cradle had become metaphorically meaningful. Thus, through its role as a form that holds and soothes, cradle as word and object accrued loaded connotations, instilling it with meanings beyond its original use. In the case of the cradle, these intervening years, characterized by James as an elongated table, imbued it with enhanced meanings.[8]

The cradle’s role as a protector of human life was countered by a cultural association with death, particularly before the decrease in infant mortality rates in the twentieth century. Ideally, cradles protected children from various domestic hazards, but in practice sickness and accidents could easily occur in there. The idiom “cradle-to-grave” hints at a linear conception of life and relates an infant’s earliest setting with a final resting place. This phrase finds visual expression in Henry Vanhorn’s shop sign from 1805, attributed to Edward Hicks, which depicts a cradle, a chest of drawers, and a coffin, suggesting that he could accommodate needs for all the stages of life (fig. 9). In the late nineteenth century, empty cradles served as symbols of a dead child, as exemplified by a grave marker in Mount Auburn Cemetery and the illustration on the cover page of the sheet music for Cradles Empty, Babys Gone Songster of 1883. In the same Centennial Exhibition where the Wadsworth Atheneum cradle was exhibited, the Swedish Section of the fair demonstrated that tendency. The pavilion featured a life-size display of wax figures mourning a dead infant lying in a cradle. The father sits to the side with a young child at his knee, while the mother kneels over the cradle, covering her face with her hands. Passersby could observe tragedy unfolding in a composed scene that placed the cradle at the focal point (fig. 10).[9]

The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century proliferation of stories, poetry, and imagery that incorporated allusions to death reveals the cradle’s role as a protective but susceptible vessel, much like a ship at sea. Solid, high-walled cradles are particularly reminiscent of seafaring vessels and suggest the beginning of the metaphoric voyage of life. An apocryphal story about the cradle illustrated in figure 5 points to this connection. It descended in the Thacher family, whose seventeenth-century ancestors experienced tragedy when their four children drowned as their boat foundered off Cape Ann. By the nineteenth century, historical fact had mutated into a legend that celebrated the family cradle. In this version of the story, published in Century Magazine in 1833, the youngest child escaped death and floated ashore in the cradle. The cradle literally became a seaworthy vessel associated with death and survival. The cradle illustrated in figure 6 has a sailing ship crudely carved into one of its side panels, likely by the hand of a daydreaming child.[10]

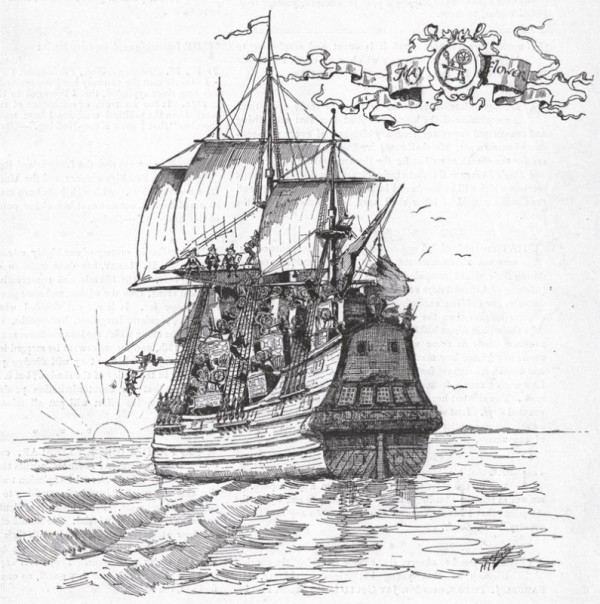

Emma Hart Willard’s popular 1831 poem, “Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep” makes more explicit the connection between cradles and boats by likening the sensation of rocking on a ship in the ocean to her faith in God. Written during her return voyage from Europe, it alludes to death and repeats the refrain: “Rocked in the cradle of the deep, / I lay me down in peace to sleep.” This connection between cradles and boats is particularly fitting for the Wadsworth Atheneum cradle because of its historical association with the Mayflower. Until the twentieth century, the cradle was believed to have been used during the voyage from England to Plymouth to rock Peregrine White, who was born en route to the New World. Nutting recounted the legend told by later owners that, as the colonists unloaded the Mayflower, the cradle was brought ashore to soothe the baby. The association between cradle and ship asks to be interrogated. A satirical nineteenth-century illustration featuring the colonists’ ship crammed with colonial furniture points to a desire to establish the provenance of a large body of early American decorative arts as authentically tied to the Pilgrims’ arrival in the New World (fig. 11). This urge to trace objects back to the Mayflower can be explained by economic motivations, but it also suggests the emphasis placed on experiential history for nineteenth-century Americans. The cradle’s value derives in part from the belief that it took the same journey as the Pilgrims. This nineteenth-century mode of historical valuation would figure prominently in the cradle’s display in 1876.[11]

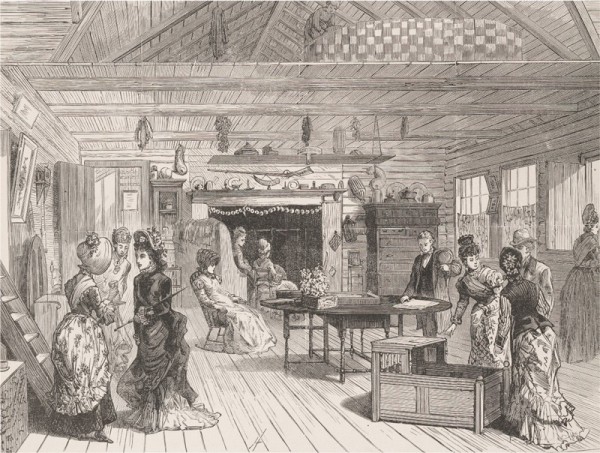

The cradle descended in Plymouth families for two hundred years before becoming part of the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia. This world’s fair marked a shift in the cradle’s life, from object of use and disrepair in a domestic setting to object of display and veneration in a public setting. The cradle appeared in the New England Farmer’s Log Cabin, a freestanding exhibit organized by forty-two-year-old Emma Southwick of Peabody, Massachusetts (fig. 12). Southwick had visited the 1873 Vienna International Exhibition and been disappointed by the lack of American involvement. When she returned home, she took partial charge of the office of the Centennial Commission in Boston and received approval for the Log Cabin, which drew from earlier colonial kitchen reenactments that had been a popular feature at expositions since 1864, when a series of Sanitary Commission fairs were held in New York City and the surrounding region. The cabin contained four main spaces: a spacious, open parlor and kitchen; a small bedroom; an attic; and a restaurant in which visitors could eat traditional colonial food. Women in costume served meals and acted as historical interpreters. Southwick and her fellow organizers filled these spaces with historic furnishings borrowed from families in the Boston area, many of which had storied provenances similar to the cradle’s.[12]

A wood engraving from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition, published to coincide with the fair, illustrates the interior of the main exhibition room and provides a selective interpretation of the scene that suggests sentimental attitudes toward the colonial past (fig. 13). The room is presented as a cross section; one wall has been removed to create a diorama-like view. A large, open hearth cluttered with antique cooking implements and mementos of the colonial period dominates the room, providing the backdrop for the furniture and artifacts on display. Women populate the space, some dressed as guides in costume and others as tourists in nineteenth-century clothing. The cradle rests on the floor in the foreground, its rockers missing. A paper label appears to be attached to the hood. Two women and a man inspect the cradle, gesturing toward it and conversing. Another woman seats herself in a Windsor rocking chair, creating the sense that these visitors are attempting to experience the past. William Dean Howells’s description of his visit to the Log Cabin echoes the mood presented in the Leslie engraving. Howells witnessed an “old Quakeress,” inspired by a young reenactor, try her hand at the spinning wheel for the first time in decades. After a tense start, “the wheel went round with a soft triumphant burr, while the crowd heaved a sigh of relief.” Like Howells’s description, the main portion of Leslie’s engraving presents the illusion of historical experience and a sense of intimacy with the past. However, the presence of the attic in the upper sixth of the image, visible only because of Leslie’s didactic mode of representation (the cross section), reveals the artifice of his depiction and, by extension, the exhibit.[13]

The contrived nature of the engraving parallels the historically incorrect function of the attic in the Log Cabin. Like a catwalk above a stage that is visible to a theater audience, the attic undermines the viewer’s attempt to experience the room as being truly from another time, reminding us that the New England Farmer’s Log Cabin is an illusion. Although the Log Cabin claimed to represent a colonial home, the upstairs reflected the nineteenth-century, rather than the colonial-era, conception of the attic. Early American attics were more likely to be used as places for sleeping and storing grain and outmoded household objects than family heirlooms. At the centennial, it was a storehouse for layers of the physical past where visitors could unpack, play with, and rearrange various objects spanning two hundred years, much as they might in their own nineteenth-century attics. Countering the staged and prescribed nature of the main space of the cabin, the attic offered a tangible history. An anonymous Hartford Times correspondent who visited the fair in May 1876 described exploring the attic, noting that “the old gowns and bonnets and leather bags and chairs . . . stowed away up there were twice as interesting as those in plain sight below.” By providing a place where visitors could pick up and play with historical artifacts, the attic in the Log Cabin collapsed the gulf of lapsed time between the present and the past as a distant and antiquated place.[14]

In twentieth-century scholarship, the New England Farmer’s Log Cabin is frequently described as a site of historical inaccuracies that incorrectly reenacted the past. Indeed, historians of art, architecture, and American history, as well as archaeologists, have proven wrong many aspects of the display. In Leslie’s illustration and in contemporary photographs, the ceiling is high, the sash windows are large, and the guides wear costumes that mix historical and present-day styles (figs. 13, 14). Written accounts from the centennial also reflect this casual attitude toward establishing provable events in the past. When journalists chronicling the fair wrote that the cradle came to Massachusetts on the Mayflower, they often mentioned it in tandem with a small wooden desk, said to have been used by John Alden to write to Priscilla Mullins (fig. 14). Discussions of the desk seamlessly blend historical fact with the fictional John Alden from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s popular 1858 poem, “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” (It is this same John Alden who, in the early twentieth century, was credited with having made the cradle.) Rife with stories founded on legends rather than fact, the exhibit illuminates a nineteenth-century conception of past events as a closed system characterized by remarkable coincidence, similar to the structure of a novel.[15]

In their essay “Numinous Objects,” Rachel Maines and James Glynn pinpoint an alternative mode for examining historic artifacts, expanding the discourse on objects with associational value and questioning the practice of favoring aesthetic standards and earliest history. They note the ability of artifacts to “concretize abstract memories,” which in the case of the cradle allowed visitors to the Log Cabin to imagine the complexities of the colonial period through the specificity of a single object. The numinous object, with its ability to absorb the significances of the world in which it lives, becomes a surviving witness of the past, almost spiritual in its ability to distill abstract events into concise and powerful narratives.[16]

This conception of the object as a witness that connects the present with the past is often repeated in accounts of the cradle’s installation in the Log Cabin. For visitors and guidebook writers, the physicality of the object became a vehicle for thinking about the past. Nothing expressed this more clearly than the cradle’s missing rockers. In The Centennial Exhibition, Described and Illustrated, J. S. Ingram wrote, “the rockers were not there, having been made away with by the ravages of time, but we had the cradle to remind us of that adventurous infant who forced his way into the world at such a trying time.” Ingram brings his description of the “adventurous infant” to life by juxtaposing it with physical destruction—the “ravages of time” that wore away the rockers. His words are echoed in the writing of the Hartford Times correspondent, who commented, “It has no rockers now, and it would be undignified for such an eminently aged and respectable cradle to do service any longer,” and by James McCabe, who observed, “The rockers have been worn away by long years that have elapsed since then, but the cradle remains a mute witness of the wonderful story of American progress with which all tongues are busy now.” The objects in the room were appreciated as a connection to the past, as bearers of mundane and climactic moments in American history.[17]

As they addressed the cradle’s physical condition, possibly with the aid of the paper label that appears in the Leslie engraving, these writers acknowledged the cradle’s existence as a physical object altered by the passage of time. Instead of being consumed as an object of use, the cradle became a historical sign, endowed with value through its age and physical wear. Confronted with a cradle that can no longer perform its primary function because of physical deterioration caused by use, visitors experienced feelings of loss and attraction, allowing them to associate more closely with the past. The cradle’s role in the narrative is significant not because of the specific provable facts of its history but, rather, because of the weighty cultural connotations it carries long after it ceased to rock.

A passage from Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time amplifies the present consideration of the ways in which use and disuse may influence the interpretation of objects. In reference to a hammer, Heidegger notes, “When something . . . is missing whose everyday presence was so much a matter of course that we never even paid attention to it . . . [we] . . . see for the first time what the missing thing was at hand for and at hand with. Again, the surrounding world makes itself known.” Although these words refer to an entire object gone missing, it is comparable to the disappearance of the cradle’s rockers, which were essential to its function as a soothing mechanism for children and parents. Here, Heidigger echoes James’s marks and signs of a visitable past. The wear that has destroyed the rockers confirms the cradle as being an object of the world, functional and breakable. The viewer or user sees the surrounding contemporary and historic worlds with refreshed perspective owing to the contrast between the former time and the present. Confronted with a cradle that can no longer perform one of its primary functions, visitors experienced nostalgia, perhaps enhanced by the rocking chair, which evoked the lulling rhythm of a cradle with rockers.[18]

The correspondent for the Hartford Times wrote about other objects in the room as witnesses to the past, pausing at a Pilgrim’s pocketbook. Her ruminations on the nature of its existence can aid in our thinking about the cradle’s history:

A Pilgrim’s pocket-book mutely tried to tell its story. We listened, but could not understand. Who made it, so carefully? Who carried this dainty memento over the sea to the land of home-spun and rugged poverty . . . ? [Its] history we can never know—we could not read it, though we gazed long and earnestly; we could not hear it, though we listened faithfully. And the story, sad or glad, so long ago all told and ended, is to us, only a distant echo . . . with only this silent witness of what has been connected to-day with the far off yesterday.

This passage offers a rich account of the relation between a surviving object and the 1876 visitor. The terms are relevant for our discussion of the cradle. Signs of use hint at a story that cannot be precisely told but still hovers, shaping any interpretation. The cradle without rockers can no longer be used at its earliest, fullest capacity, and a chapter in its life has irreversibly passed. The correspondent is comfortable recognizing that precise historical knowledge is beyond her grasp and allows this sense of nostalgia to enhance her understanding. Like the pocketbook, the cradle is a powerful link between the present and the past, although these connections remain elusive.[19]

One of the visitors to the New England Farmer’s Log Cabin was Wallace Nutting (1861–1941), a fifteen-year-old high-school student from Rockbottom, Massachusetts. After experiencing a nervous breakdown in 1899 while serving as minister for the Plymouth Congregation Church in Providence, Rhode Island, Nutting took up photography as a soothing pastime. As the founder of the lifestyle brand Old America, which sold colonial revival furniture and hand-tinted photographs of old-fashioned New England scenes, Nutting became one of the major popularizers of the colonial revival. The cradle became part of his collection of seventeenth-century “Pilgrim” furniture when he purchased it from the collector Chauncey C. Nash, who had acquired it before 1921 directly from the Cushman family of Plymouth, Massachusetts. With Nutting, the cradle took on new meaning as an instructor of conservative American values. He found a middle class eager to buy into the mania for Puritan nostalgia and began publishing his collection of American antiques in books that combined historical anecdotes with praise for the pious Pilgrim forefathers.[20]

Before publishing or even owning the cradle, Nutting oversaw a key alteration to it. In the first edition of Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, he describes replacing “the missing rockers with oak cut from the face of an exposed beam in the Marsh House, Wethersfield, the oldest house in town.” While the use of antique wood makes sense because it would match the appearance of the cradle, Nutting’s choice is even more significant. His decision to cull wood from the oldest house in Wethersfield suggests that he sought to link his collection with the tradition of nineteenth-century relic furniture. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, wood dating from the colonial era had taken on relic status through its connections with American history. At the Centennial Exhibition, an armchair was exhibited that was made from the Washington Elm, under which General George Washington purportedly stood when he accepted the command of the Continental Army in 1775. As an antiquarian and citizen of Connecticut, Nutting would have been familiar with the story of Hartford’s Charter Oak, which was felled during a storm in 1856; its wood was subsequently used to make several cherished pieces of furniture. This valuing of the physical environment for its evocative qualities imbued antique wood with historic importance, and Nutting’s new rockers reflected that trend. By replacing the rockers with salvaged wood, he added another layer of associational identity to the cradle.[21]

By returning the cradle to its original function, Nutting also deemphasized the years that had intervened between the late seventeenth century and the early twentieth. It was no longer the worn, defunct relic that prompted so many centennial writers to dwell on its age and role as witness to American progress. In Nutting’s second edition of Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, the cradle communicated to customers that so-called Pilgrim values were not so far from the homes of twentieth-century Americans. By rendering the cradle functional once again, Nutting obscured its nineteenth-century history of display and sought to use it to attract American consumers interested in perceived traditional values.[22]

Nutting also constructed a link between the cradle and the hearth in his description of the setting for a young American’s—naturally a boy’s—education: “The hearth really became the sacred spot in our ancestral history. The baby was born by the hearth, was rocked there. . . . At a later period, it was at the hearth that his education began, as he . . . sat upon his grandfather’s knees, and heard the tales of long ago. There, also, he . . . read of Bunyan’s Pilgrim.” In this patriarchal understanding of American childhood, with its emphasis on the value of absorbing ancestral tradition and reading Puritanical moralizing texts, Nutting reanimated the cradle and reinterpreted it as a symbol of what he sold as the golden, virtuously conservative colonial era.[23]

Nutting’s use and interpretation of the cradle mark the end of its journey through private hands. In January 1926 James Pierpont Morgan Jr. purchased Nutting’s collection and donated it to the Wadsworth Atheneum. At the Atheneum, the cradle has been part of three major permanent installations and will also figure in major gallery renovations scheduled to take place in the coming years. When the Nutting Collection was first installed in the basement of the Morgan Memorial, the cradle was clustered with other seventeenth-century objects in galleries that loosely resembled domestic settings (fig. 15). In a photograph taken soon after the galleries opened, the cradle can be seen flanked by one adult’s and one child’s chair, an arrangement that suggests an anthropomorphized, familial dynamic. Like the Log Cabin, visitors interacted with the space, walking among the furniture and experiencing it in the round.

In 1934, under the leadership of Director Arthur Everett “Chick” Austin Jr., Nutting’s collection, as well as the museum’s collection of modern art, was reinstalled in the newly built Avery Memorial. In this International Style exhibition space, objects were arranged in rows against white walls (fig. 16). This display format was considered cutting edge at the time, a conscious nod to the innovative agenda instituted at the Newark Museum and the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). Under the leadership of Alfred Barr, MoMA had begun displaying in white-walled galleries not only fine art but also folk art and industrial design. In a photograph of the Wadsworth Atheneum galleries, Nutting’s objects can be seen similarly placed, against the wall, to be appreciated for their shapes and silhouettes rather than experienced as three-dimensional, functional furniture. A photograph taken of the 1934 installation includes the cradle, barely visible beneath a window along the back wall. A table and stools are raised on a plinth in the center of the gallery to be admired as sculpture, and the white walls, ample light, and symmetrical placement of objects emphasize form over atmospheric quality.[24]

Over the past three decades, the cradle has resided in the Wallace Nutting Collection of American Furniture galleries at the Atheneum. In a room labeled “Rare Forms of the Seventeenth Century,” the cradle, two seventeenth-century tables, two boxes, a stool, and a clock rested on a dais made of blond, unfinished wood united by a neutral beige backdrop (fig. 17). The installation organized these historic objects based on aesthetic criteria—“Forms”—and placed them in decontextualized gallery space. The layout and design of the space was an amalgam of the 1928 and 1934 installations in that it grouped objects into clusters meant to relate to one another, but it also kept them against the wall, much like two-dimensional objects.[25]

Labels accompanying each object, updated in 2003 for the temporary exhibition Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America, contextualized the objects in terms of their formal qualities and known history. The cradle’s label offers a case in point. It explained that the cradle is “decorated with turnings and moldings of unsurpassed complexity.” By drawing out the cradle’s presumed artisanal qualities, the museum text collapsed the sense of time, encouraging visitors to appreciate objects through formal analysis. The cradle’s label also provided information about its origin and subsequent existence, noting that the cradle was exhibited at the centennial but only to point out that while nineteenth-century Americans thought it came over on the Mayflower, it was in fact made of American wood. By noting the inaccuracy of nineteenth-century conceptions of the past, the text emphasized the accuracy of the most current interpretation of the cradle. In doing so, the exhibition did not explore past modes of approaching historical objects that were in fact purposeful and meaningful at the time. However, it did highlight the design-conscious craftsmanship that was required to produce the cradle, finding new meaning that nineteenth-century viewers did not. The cradle continues to be defined as part of Wallace Nutting’s collection but understood as a finely crafted historic artifact rather than a symbolically meaningful link to the past.[26]

During the past century, many historic objects were placed in museums and interpreted as art. In many instances, the numinous qualities that gave those artifacts historic or relic status were lost, disregarded, or marginalized. Indeed, the term “antiquarianism,” which is associated with past modes of interpretation that valued relics as evocative remnants of history, currently has negative connotations in both academe and museums. Today, the construction and decoration of the cradle are cited as pathways for understanding seventeenth-century craftsmanship and aesthetics, and its functional and symbolic attributes are read almost solely from a period perspective. However, the cradle’s presence at the centennial speaks to the power of American conceptions of selfhood in the nineteenth century, and its ownership by Wallace Nutting, which led to a change in the cradle’s appearance and perception, made it part of a culturally influential body of early American furniture.

This description of the various chapters in the cradle’s life brings us to the present day. Admittedly, this essay provides no resolution to the interpretative questions posed by the history of the cradle’s restagings. In its capacity as a functioning object on display, the cradle is itself a constantly evolving narrative, one with multiple layers of history that can be read in the documentation surrounding it and in the marks of age and repair that altered its physical appearance. In the attempt to interpret these stories, scholars in academe and museums find themselves reaching across James’s metaphoric table, grasping for a “palpable imaginable visitable past.” In his preface, James goes on to posit the seemingly fluid relationship between the present and the past. He writes, “we are divided of course between liking to feel the past strange and liking to feel it familiar; the difficulty is . . . to catch it at the moment when the scales of the balance hang with the right evenness.” With its rockers seemingly poised for movement, the cradle suggests that there is no right evenness, only an ever-changing attempt to create one.[27]

Emphasis in the original. Henry James, The Aspern Papers (1908; New York: Courier Dover Publications, 2001), p. ix. This passage has informed work by other art historians, including Margaretta M. Lovell and Michael Ann Holly. See Margaretta M. Lovell, A Visitable Past: Views of Venice by American Artists, 1860–1915 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989); and Michael Ann Holly, “Interventions: The Melancholy Art,” Art Bulletin 89, no. 1 (March 2007): 15. In writing this paper, I relied on the expertise and generosity of many people. Thank you Edward Cooke, Marc Simpson, Alyce Englund, Layla Bermeo, and Diana Nawi for their guidance at many stages of research and writing.

Curatorial and archives staff at the Wadsworth Atheneum generously made available documents relating to the cradle. Acc. file 26.365, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Conn.

A dendrochronology report confirmed the presence of red oak. Donna J. Christensen to Phillip Johnston, February 24, 1977, acc. file 26.365. Cabinetmakers’ account books frequently mention replacing rockers. Nancy Goyne Evans, “The Written Evidence of Furniture Repairs and Alterations: How Original Is ‘All Original’?,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 208–10. Paula A. Treckel, To Comfort the Heart: Women in Seventeenth-Century America (New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996), p. 82. Abbott Lowell Cummings, Rural Household Inventories: Establishing the Names, Uses and Furnishings of Rooms in the Colonial New England Home, 1675–1775 (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1964), pp. 8, 236.

For more on historically accurate terminology, see Evans, “Written Evidence of Furniture Repairs,” p. 209.

Cradles prevented infants from being suffocated in bed with their parents. Mary Martin McLaughlin, “Survivors and Surrogates: Children and Parents from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Centuries,” in Lloyd Demause, The History of Childhood (New York: Psychohistory Press, 1974), p. 117. For a discussion of the Pilgrims’ experience in the New World, see James Deetz, The Times of Their Lives: Life, Love, and Death in Plymouth Colony (New York: W. H. Freeman, 2000).

Ethel Hall Bjerkoe, The Cabinetmakers of America (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, 1957), pp. 22–23, 236–37; Thomas H. Ormsbee, Early American Furniture Makers: A Social and Biographical Study (New York: Archer House, 1933, 1957), pp. 22–25; and Robert Blair St. George, The Wrought Covenant: Source Material for the Study of Craftsmen and Community in Southeastern New England, 1620–1700 (Brockton, Mass.: Brockton Art Center/Fuller Memorial, 1979), pp. 72, 102. More than 150 woodworkers have been documented in seventeenth-century New England (Robert F. Trent, “New England Joinery and Turning before 1700,” in New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century, edited by Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Trent, 3 vols. [Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1982], 3: 501–50). For the histories of the related cradles, see St. George, The Wrought Covenant, pp. 54–55.

Rocking encouraged regular sleeping patterns and soothed the baby’s discomfort caused by itchy swaddling clothes and cushioning materials. In 1658 London diarist John Evelyn blamed the death of his infant on suffocation caused by “ye women and maids that tended him, and covered him too hot with blankets as he lay near an excessive hot fire in a close room”; quoted in Ralph Edwards, The Shorter Dictionary of English Furniture (London: Country Life, 1964), p. 275. Demause, The History of Childhood; Christina Hardyment, Dream Babies: Child Care from Locke to Spock (London: Jonathan Cape, 1983), pp. 6, 24, 55, 131; and Philip J. Greven Jr., Child-Rearing Concepts, 1628–1861 (Itasca, Ill.: F. E. Peacock Publishers, 1973), pp. 19, 46, 188.

Sally Kevill-Davies, Yesterday’s Children: The Antiques and History of Childcare (London: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1991), pp. 110, 282–84.

Barbara J. Logue, “In Pursuit of Prosperity: Disease and Death in a Massachusetts Commercial Port, 1660–1850,” Journal of Social History 25, no. 2 (Winter 1991): 314, 333–34. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Knopf, 2001), pp. 236–38. Cradles Empty, Baby’s Gone Songster, no. 112 (New York: Popular Publishing Co., 1883), in Ellen Marie Snyder, “At Rest: Victorian Death Furniture,” in Perspectives on American Furniture, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988), p. 269. The popular poem “Rock Me to Sleep, Mother,” written in 1882 by Elizabeth Akers Allen, also brings together cradles and death, as the verses mourn the loss of childhood and a deceased mother. Mary Cable, The Little Darlings: A History of Child Rearing in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972), pp. 95–96.

F. Mitchell, “Cape Cod,” Century Magazine 26 (1883): 647–48; quoted in Nancy Carlisle, Cherished Possessions: A New England Legacy (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 2003), p. 92.

Nutting first published this story in 1921, before he owned the cradle. Wallace Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century (Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1921), pp. 314–15.

Rodris Roth, “The New England, or ‘Olde Tyme,’ Kitchen Exhibit at Nineteenth-Century Fairs,” in The Colonial Revival in America, edited by Alan Axelrod (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1985), pp. 160, 174. For descriptions of the Log Cabin in nineteenth-century literature, see “Two of Us at the Centennial,” Hartford Times, May 29, 1876, p. 1; William Dean Howells, “A Sennight of the Centennial,” Atlantic Monthly, July 1876, at http://www3.villanova.edu/centennial/sennight.htm (accessed April 15, 2009); J. S. Ingram, The Centennial Exposition, Described and Illustrated (Philadelphia: Hubbard Bros., 1876), pp. 707, 708; Frank Leslie, Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition 1876 (New York: Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, 1877), pp. 87, 90; James D. McCabe, The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition (Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1876), pp. 722, 723; Phillip T. Sandhurst, The Great Centennial Exhibition, Critically Described and Illustrated (Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler & Co., 1876), pp. 541, 542; and Earl Shinn, et al., The Masterpieces of the Centennial International Exhibition in 3 Volumes (1876; New York: Garland Publishing, 1977), pp. clviii–clxii. Kitchens and other centennial-era exhibits of colonial relics were most often organized by individual women and women’s societies. Barbara J. Howe has attributed the prominent role that women played in these exhibits to an extension of the cult of domesticity, arguing that as caretakers and preservers of the family, women also took leadership roles in preserving the objects and historic sites that represented national tradition. Howe, “Women in the Nineteenth-Century Preservation Movement,” in Restoring Women’s History through Historic Preservation, edited by Jennifer B. Goodman and Gail Lee Dubrow (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), pp. 17–36; Robert P. Emlin, “Colonial Relics, Nativism, and the DAR Loan Exhibition of 1892,” in New England Collectors and Collections, edited by Peter Benes and Jane Montague Benes (Boston: Boston University, 2006), pp. 171–87; and Elizabeth Stillinger, The Antiquers: The Lives and Careers, the Deals, the Finds, the Collections of Men and Women Who Were Responsible for the Changing Taste in American Antiques, 1850–1930 (New York: Knopf, 1980). I have been unable to recover the location of the cradle at the time of the centennial, although it was very likely privately owned in 1876, just as it was in the early twentieth century. Perhaps Sarah Orne Jewett, who visited the Log Cabin in 1876 and grew up with family heirlooms in New England, best re-creates the cradle’s place in the household in the decades leading up to the centennial. In “The Flight of Betsey Lane,” a short story from 1893 about an aging spinster who visits the Centennial Exhibition, Jewett sets the first scene in a shed cluttered with disused objects, including “an old cradle.” Jewett, “The Flight of Betsey Lane,” in Jewett Novels and Stories (New York: Library of America, 1994), p. 789. See also Ben Slote, “Jewett at the Fair, Seeing Citizens in ‘The Flight of Betsey Lane,’” Studies in American Fiction 36, no. 4 (Spring 2008): 51–76.

Howells, “A Sennight of the Centennial.”

Cummings, Rural Household Inventories, p. xix. The garret served as storage for stylistically or functionally outmoded furniture and objects. The trove of things found in a garret could mark a household’s evolution, as Benjamin Franklin, under the pen name Anthony Afterwit, noted in the 1732 Pennsylvania Gazette. A new looking glass functioned as the catalyst for a wholesale removal of parlor furnishings to the garret: “In a week’s time, I was made sensible by little and little, that the table was by no means suitable to such a glass, and a more proper table being procured, my spouse . . . informed me where we might have very handsome chairs in the way; and thus . . . I found all my old furniture stowed up into the garret, and everything below alter’d for the better.” Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania Gazette, July 10, 1732; quoted in Elisabeth Garrett, At Home: The American Family, 1750–1870 (New York: Abrams, 1990), p. 249. “Two of Us at the Centennial,” p. 1.

For twentieth- and twenty-first-century scholarship, see Abigail Carroll, “Of Kettles and Cranes: Colonial Revival Kitchens and the Performance of National Identity,” Winterthur Portfolio 43, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 335–64; Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), pp. 135–38; Dianne H. Pilgrim, “Inherited from the Past: The American Period Room,” American Art Journal 10 (1978): 8–10; Rodris Roth, “The Colonial Revival and ‘Centennial Furniture’” Art Quarterly 27 (1964): 57–78; Roth, “The New England, or ‘Olde Tyme,’ Kitchen Exhibit,” pp. 173–80; and Richard H. Saunders, “Collecting American Decorative Arts in New England, Part I: 1793–1876,” Antiques 109, no. 5 (May 1976): 996–1003. The Hartford Times correspondent described the experience of touching the desk and sensing Alden as he “wrote with busy pen, while his thoughts were wandering to the Puritan Maiden Priscilla” (“Two of Us at the Centennial,” p. 1). Abigail Carroll posits that colonial revival kitchens were more akin to theater productions than reenactments. Carroll, “Colonial Revival Kitchens and the Performance of National Identity.”

Rachel P. Maines and James J. Glynn, “Numinous Objects,” Public Historian 15 (1993): 10. Scholars in the last fifteen years have increasingly considered the associational value that objects can accrue. Perhaps the most noted example of this practice in recent scholarship is Ulrich, The Age of Homespun.

Ingram, The Centennial Exposition, p. 707. “Two of Us at the Centennial,” p. 1; and McCabe, Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition, p. 722. McCabe observed that the cradle survived the Pilgrims and later witnessed Revolutionary events.

Martin Heidegger, Being and Time: A Translation of Sein und Zeit, translated by Joan Stambaugh (Albany, N.Y.: State University Press, 1996), p. 75.

“Two of Us at the Centennial,” p 1.

For a thorough biography of Wallace Nutting and the beginnings of Old America, see Thomas Andrew Denenberg, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 1–22. Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, 1: 314 (p. 422 in the 2nd ed., 1924).

Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century (1924), 1: 425. Stillinger, The Antiquers, pp. 21, 22. The Connecticut Historical Society, Connecticut State Library, and the Wadsworth Atheneum all own several objects said to be made from the Charter Oak, including the Colt family cradle at the Atheneum. For more on relic furniture, see Rodris Roth, “Pieces of History: Relic curniture of the Nineteenth Century,” Antiques 101, no. 5 (May 1972): 874–78. The interest in preserving historic objects and sites as relics is often said to have begun in the United States by Thomas Jefferson, who wrote in reference to preserving the original Declaration of Independence: “Small things, may, perhaps, like the relics of saints, help to nourish our devotion to this holy bond of our Union and keep it longer alive and warm in our affections”; quoted in Thomas Jefferson: A Chronology of His Thoughts, edited by Jerry Holmes (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002), p. 304.

Having visited the Log Cabin at the 1876 Centennial, Nutting would have known the cradle’s postcolonial history. Seeing the Log Cabin may have influenced his work in other ways as well. Nutting designed the period room representing the New Hampshire Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in the DAR Museum as an attic for displaying a rotation of antique toys and artifacts. “DAR Museum Virtual Period Room Tour,” last modified March 2008, http://www.dar.org/omni/virtualtours/museum/NH.html.

Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century (1924): 1: 420, 421. Old America exploited the tendency to think of New England’s history as national rather than regional, a movement that has been linked to a desire to restore the country’s unity after the Civil War. See Celia Betsky, “Inside the Past: The Interior and the Colonial Revival in American Art and Literature, 1860–1914,” in Axelrod, ed., The Colonial Revival in America, pp. 241–77. See also William H. Truettner and Roger B. Stein et al., Picturing Old New England (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999).

Ezra Shales, Made in Newark: Cultivating Industrial Arts and Civic Identity in the Progressive Era (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2010), pp. 1–29 and 101–219. Jennifer Jane Marshall, “In Form We Trust: Neoplatonism, the Gold Standard, and the Machine Art Show, 1934,” Art Bulletin 90, no. 4 (December 2008): 597–615. Holger Cahill, American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1932). Denenberg, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America, p. 115. Denenberg, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America, p. 117.

Wadsworth Atheneum, gallery panel, as of April 20, 2008.

Wadsworth Atheneum, object label, as of April 20, 2008.

James, The Aspern Papers, p. ix.