Charles Bird King, Thomas Jefferson, 1836. Oil on panel. 19 1/2" x 16 1/4". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, 92.110.) Nicholas Philip Trist commissioned this portrait. King copied an earlier likeness by Gilbert Stuart, which was the favorite of Jefferson and his family.

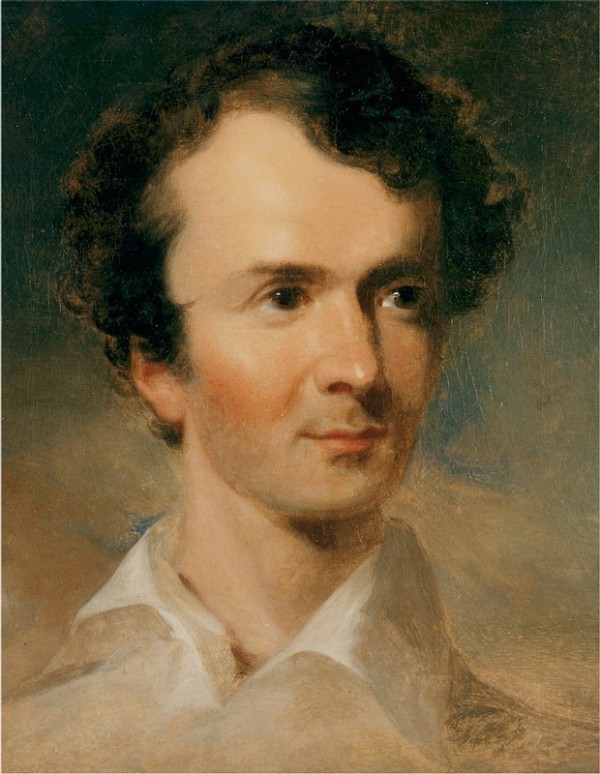

Campeachy chair, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1818. Cherry, rosewood, and lightwood inlays. H. 42 3/4", W. 22 1/2", D. 20 9/16". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the crest of the chair illustrated in fig. 2.

Pen Park, Albemarle County, Virginia, 1888 (Courtesy, Valentine Richmond History Center, V.45.47.335; photo, Robert A. Lancaster Jr.) Pen Park was north of Charlottesville.

Digital reconstruction of the Campeachy chair illustrated in fig. 2, showing it with red leather and the stiles extended above the upper upholstery line.

Henri Elois, Hore Browse Trist, 1798–1799. Watercolor on ivory. 3 1/8" x 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, 1936.303.)

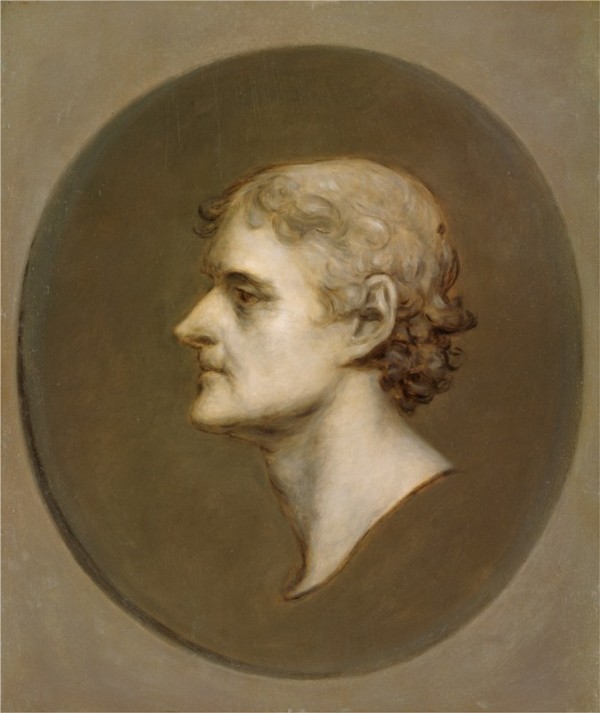

Charles Auguste Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin (1770–1852), Thomas Bolling Robertson, 1808. Chalk on pink paper. 22" x 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic New Orleans Collection, 2011.0408, acquisition made possible by the Laussat Society.)

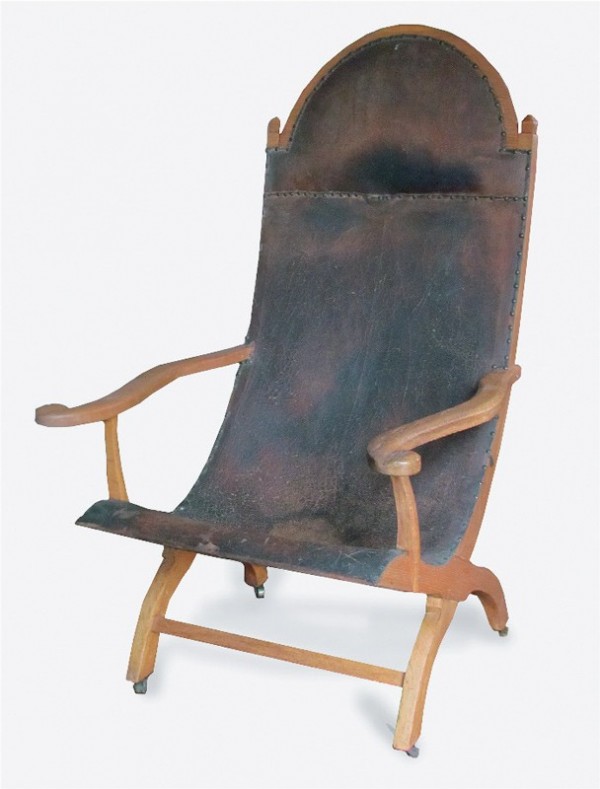

Campeachy chair attributed to William Worthington, Washington, D.C., 1815–1820. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 37 1/2", W. 21", D. 31 1/2". (Courtesy, Peter W. Patout, New Orleans; photo, Ellen McDermott, New York.)

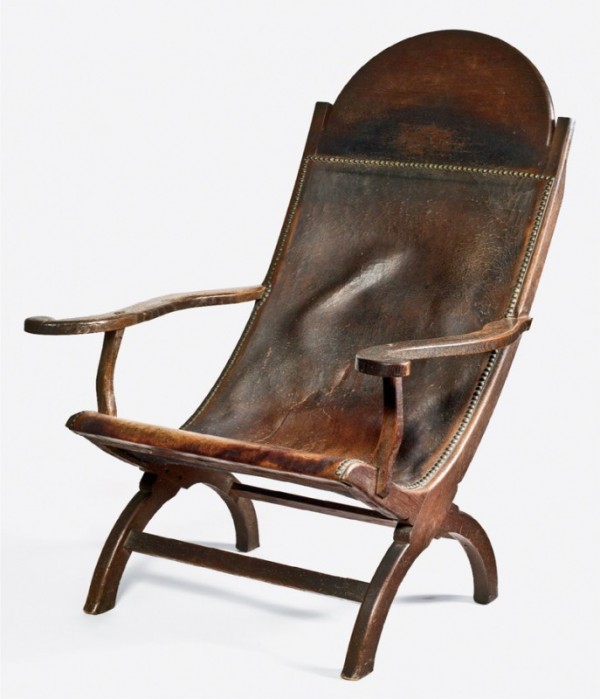

John Neagle (1796–1865), Nicholas Philip Trist, 1835. Oil on canvas. 15" x 13". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc., Monticello.)

Charles Willson Peale, Hore Browse Trist, ca. 1820. Cut paper. 2 15/16" x 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc., Monticello.)

Campeachy chair attributed to John Hemings, Monticello joinery, Albemarle County, Virginia, 1819–1820. White oak. H. 43", W. 28 7/8", D. 20 3/16". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Hemings’s chairs are sturdier than the Louisiana prototype (fig. 2) and were more capable of sustaining heavy use on a Virginia plantation. The legs, seat, and back of his chairs are made from 1 1/4" stock, their arms and arm supports from 1" stock, their crests are cut from 7/8" boards, and their stretchers are made from 3/4" stock. The corresponding stock dimensions on the Louisiana chairs are 7/8", 7/8", 3/4", and 5/8".

Hemings’s stock is heavier than that used for the Louisiana prototypes, but he went to considerable effort to produce a chair of similar dimensions. The Cabell chair is 43" high, 22" wide across the back, 20 3/16" deep at the feet, and has a crest 12 3/4" in height. On the Trist-Gilmer example, the corresponding dimensions are 42 1/2", 22 1/2", 20 9/16", and 12 1/2".

Campeachy chair attributed to John Hemings, Monticello joinery, Albemarle County, Virginia, 1815–1824. White oak; leather, brass nails. H. 45", W. 27 1/4", D. 33 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Campeachy chair attributed to John Hemings, Monticello joinery, Albemarle County, Virginia, 1815–1824. White ash. H. 42 1/4", W. 28", D. 32". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc., Monticello.)

Edgewood, Nelson County, Virginia, 1888. (Courtesy, Robert L. Self and Briscoe Guy; photo, Robert A. Lancaster Jr.)

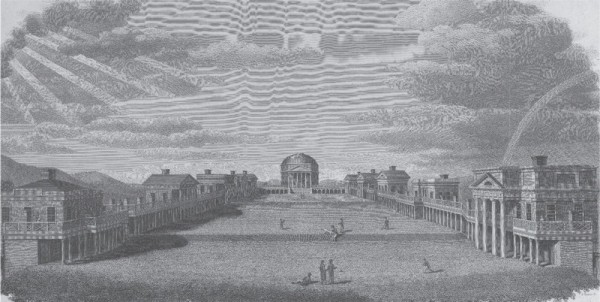

Herman Böye, View of the “University of Virginia, B. Tanner, Sc.,” cartouche on A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law, from the late surveys authorized by the Legislature and other original and authentic documents, 1825 (Richmond: State of Virginia, 1859). (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.)

Detail of the iron reinforcements on the chairs illustrated in figs. 11 (left) and 2 (right). (Photo, Sumpter Priddy III.)

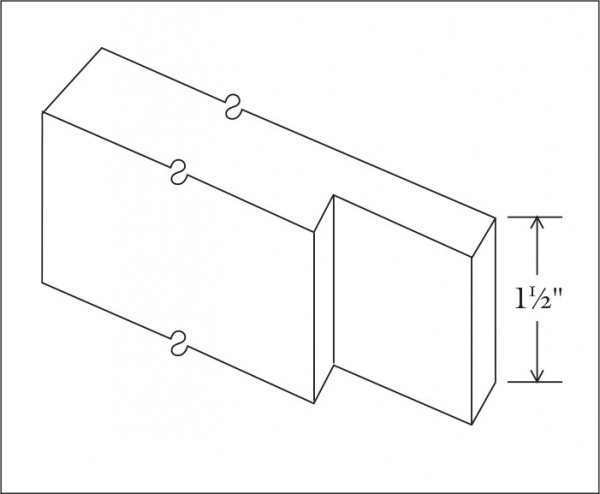

Drawing of a single shoulder tenon on the Campeachy chair illustrated in fig. 11.

Detail of the three screws securing one of the half-lapped leg joints of the chair illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Sumpter Priddy III.)

Detail of the profiles of the chairs illustrated in figs. 12 (front), 11 (middle), and 2 (back). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

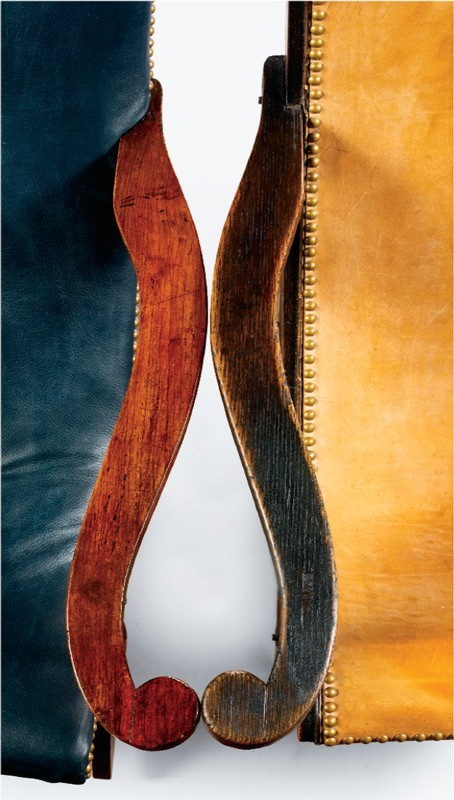

Detail of the arms of the chairs illustrated in figs. 2 (left) and 11 (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the arms of the chairs illustrated in figs. 11 (left) and 12 (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the front seat joints of the chairs illustrated in figs. 2 (left) and 11 (right). (Photo, Keith Lackman and Brendan Varley.) The improperly replaced arm support visible in fig. 11 has been correctly restored.

Detail of the front seat joints of the chairs illustrated in figs. 12 (left) and 11 (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the three screws securing one of the half-lapped leg joints of the chair illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the arm supports of the chairs illustrated in figs. 2 (left) and 12 (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Campeachy chair, probably Albemarle County, Virginia, 1830–1840. Oak; leather, brass nails. H. 49 1/2", W. 24", D. 30 5/8". (Courtesy, Matthews County Circuit Court and Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc., Monticello; photo, Sumpter Priddy III and Brendan Varley.)

Campeachy chair, probably Albemarle County, Virginia, 1830–1840. Curly maple. H. 43 3/4", W. 28 5/8", D. 31 1/2". (Courtesy, Anne Ryland Glubiak Collection; photo, Historic New Orleans Collection.)

Over the last decade, scholars have devoted considerable energy to understanding the Campeachy chair, a Latin American furniture form that arrived in Louisiana by the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. The subsequent dissemination of the innovative chair form throughout American culture reflects a process set in motion by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, in which English-speaking Americans increasingly looked west in an attempt to define a new national identity independent of European influence. As author of the Declaration of Independence and father of the Louisiana Purchase, President Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) (fig. 1) is closely linked to the ideological creation of this new identity. He is also credited with the introduction of the Campeachy chair to the Eastern Seaboard, where his slave joiner, John Hemings (1776–1833), produced several for use at Monticello. To this point, however, the sources of Jefferson’s first Campeachy chair and of Hemings’s design have remained a mystery. This article utilizes a recently rediscovered Louisiana Campeachy chair with a solid history of descent and a previously unrecognized exchange of letters as the primary texts for piecing together the story of Thomas Jefferson and the Campeachy chair.[1]

The Campeachy chair form endures today as a frame that typically consists of twelve wooden components and a single hide of heavy leather. Each side of the chair is composed of two S-shaped elements, one long and the other short. The shorter component forms the seat and rear leg, while the longer one begins as a leg in front and continues upward to form the rear stile, or post, in back. On each side of the chair, the long and short components cross just beneath the trough of the seat. A stretcher that runs from side to side ties the legs together in front, and another ties them together in back. Likewise, a rail across the front of the seat and another across the top of the back complete the horizontal elements that provide stability to the structure. Outstretched arms with supports below flank the sitter, providing not only a place to rest the elbows but also leverage points for pulling forward from—and out of—the low seat.

The leather seat plays a crucial part in the chair’s structure and must be properly applied to perform its function. The maker wets the leather thoroughly, wipes off the excess water, and, while it is still damp, nails it around the delicate wooden frame—usually on the outside edges. The nailed leather shrinks as it dries, pulling the tall back and legs tightly to the ends of the stretchers, seat rail, and crest. It holds the two sides parallel to one another and the horizontal elements perpendicular to them—and does so without need of wooden pins to secure the joints. On a finished chair, the once-flexible cowhide becomes the crucial link that holds the frame in perfect balance.

In the mid-1990s members of the Edward L. Evans family hired Halifax, Virginia, antiques dealer Robert G. D. Pottage to appraise an early nineteenth-century Campeachy chair that had descended from their ancestors. The chair was constructed principally of cherry, with S-shaped arms and an arched mahogany crest inlaid with a circle of stars reminiscent of those on the first American flag (figs. 2, 3). Although the early history of the chair was uncertain, family historian Walter William Moore II surmised that it descended from great-grandparents Peachy Ridgway Gilmer (1779–1836) and his wife, Mary House Gilmer (1785–1852), who were close friends of Thomas Jefferson. The Gilmers initially lived at Pen Park in Albemarle County (fig. 4), near Monticello, and after residing in Henry County from 1806 until 1818, relocated to Liberty—now Bedford Courthouse—scarcely sixteen miles from the president’s rural retreat at Poplar Forest. The Gilmer and Jefferson families had been friends since the mid-eighteenth century.[2]

Diane Ehrenpreis of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation featured the chair (fig. 2) in a 2010 American Furniture article titled “The Seat of State: Thomas Jefferson and the Campeachy Chair.” Her investigation focused on letters between Jefferson and Peachy Gilmer concerning the chair in 1820 and on a later note that Jefferson wrote to farm manager Joel Yancey (1774–1833), each of which revealed important facts about that object’s early history. The chair was undoubtedly one of a pair; Jefferson owned one, and his close yet little-known friend Elizabeth House Trist (1750–1829), of Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Albemarle County, owned the other. Each chair originally had red morocco upholstery, and both stood side by side at Poplar Forest in 1820 (fig. 5). About that time, Mrs. Trist presented the chair illustrated in figure 2 to Peachy Gilmer, who had extended innumerable kindnesses to her over the years. The Gilmers were connected to Trist not only by friendship but also by blood, for Mary House Gilmer was Trist’s niece.

Ehrenpreis also explored the later history of Jefferson’s chair, noting that University of Virginia Professor George Blaetterman (1788–1850) purchased the piece at the 1827 Monticello dispersal sale. She cited a 1902 reminiscence in which the professor’s stepson, George Blatterman (1820–1912), recalled his early years in Charlottesville and stated that the chair acquired by his father had a circle of stars in the crest and red morocco upholstery. Although none of the evidence revealed either chair’s specific date or place of origin, Blatterman’s account independently verified the descriptions provided by the Jefferson-Gilmer-Yancey exchange and, when considered together with the star-inlaid chair now owned by Peachy Gilmer’s descendants, established with virtual certainty that Jefferson and Trist owned seemingly identical chairs with red morocco upholstery and stars inlaid in the crest.[3]

Since the publication of Ehrenpreis’s article, a small yet significant cache of previously unstudied letters from 1818—including two written in French—have provided invaluable new insights into the origins of Jefferson’s and Trist’s chairs, helping to explain the friendship that they shared and illuminating the furniture products that John Hemings made in the Monticello joinery. The letters likewise clarified a number of later references to Campeachy chairs that have confounded Jefferson scholars. This article explores his acquisition of chairs from the Port of New Orleans as facilitated by his friends in the Trist family and conclusively shows that the chairs subsequently served as prototypes when Hemings produced Campeachy chairs in the Monticello joinery.

By 1808 Jefferson was sufficiently aware of Campeachy chairs to know that he wanted to acquire one. Where he obtained the knowledge is unverified, though a series of events suggests that his former Albemarle County neighbor, Elizabeth Trist, first told him of the form. She learned of Louisiana culture from her husband, Nicholas Trist (1743–1784), who owned property along the Mississippi and bequeathed her that land on his death. When Jefferson appointed her son, Hore Browse Trist (1775–1804) (fig. 6), the first collector and revenue officer for the Collection District of Mississippi (New Orleans), he and his family relocated to New Orleans. When the son died shortly after Elizabeth Trist arrived in the city from Albemarle County, she committed to help her widowed daughter-in-law care for two young children, Nicholas Philip Trist (1800–1874) and Hore Browse Trist II (1802–1856), and remained there for the next five years.

Elizabeth Trist corresponded with Jefferson during the time she lived in New Orleans and may have assisted him when, sometime in 1808, he informed Thomas Bolling Robertson (1779–1828) (fig. 7), at the time secretary of the Territory of Orleans (1807–1812), that he wanted a Campeachy chair. Owing to a number of factors, Robertson did not follow through until 1819, when he became attorney general of Louisiana (1819–1820). At that date, he wrote Jefferson from New Orleans to say that he was finally sending a Campeachy chair and mentioned his earlier, ill-fated attempts to do the same.

Robertson’s eventual gift to Jefferson led scholars to speculate about the contents of a now-lost communiqué in which Jefferson asked Robertson to send chairs. However, a careful reading of Robertson’s later correspondence reveals that he never actually mentioned a Jefferson letter but, instead, simply states, “Many years ago you asked me to send you a few of those chairs.” He then acknowledged the reasons he had not been able to fulfill Jefferson’s request: “Embargo, war, the infrequency of communication between N.O. and the ports of Virginia, and my being in Congress prevented me from complying with your request.” It seems unusual that a civil servant of Robertson’s character, who was indebted to Jefferson for his position as secretary of the Territory of Orleans, would respond so casually to the president. This leads one to question if the communication was informal—perhaps conveyed by a member of the Trist family, whether Mrs. Trist; her daughter-in-law Mary Brown Trist Jones Tournillon (1772–1822); Mary’s brother William Brown (1784–1849), who served as collector of customs; or some other individual in their circle. Each lived in New Orleans and communicated frequently with both the president and Robertson.[4]

Despite Robertson’s thwarted attempts to secure a chair for the president, after 1808 Jefferson ended his pursuit of a Campeachy chair and would not mention the form again for another twelve years. This could imply that he had acquired one or—at the very least—satisfied his curiosity and moved on. It also seems pertinent that in 1808, after five years in Louisiana, Elizabeth Trist scheduled a trip back to Virginia. Her decision was prompted in part by her daughter-in-law Mary, who had recently remarried. Furthermore, her grandsons, Nicholas and Browse, now eight and six, no longer needed her constant attention. She also realized that with elections in November and an inauguration in March, the president would step down after eight years in office and return home to Monticello.

When Elizabeth wrote Jefferson on April 18 and announced her impending journey to Virginia, she described her trip as a “visit.” She proposed an itinerary that would take her by sea from New Orleans to Charleston, then north by coach, through the sparsely settled Carolina piedmont, and finally into Henry County, in southern Virginia. There she would join Peachy and Mary Gilmer—who had suffered financial reversals and now lived in a modest home far from their beloved Albemarle—and then head east to stay with others in her old circle of Virginia friends, including Governor James Monroe and his wife, Elizabeth, in Richmond.[5]

The Monticello leg of Trist’s journey was timed to coincide with Jefferson’s break from Washington in August. Early in her stay, she informed him about “Campeachy Hammocks,” which had been all the rage among Americans in New Orleans. Jefferson’s correspondence upon her return to Virginia underscores the central role she played in keeping him current on fashionable tastes in the Louisiana Territory and suggests that she may initially have brought Campeachy chairs to his attention, as well. At the very least, her enthusiasm for Campeachy hammocks convinced Jefferson to write William Brown in New Orleans immediately and request that he send several to Monticello.

Mrs. Trist, who is here and in good health informs me that the campeachy hammock, made of some vegetable substance knotted, is commonly to be had at New Orleans. Having no mercantile correspondent there, I take the liberty of asking you to procure me a couple of them and address them to New York, Philadelphia, or any port in the Chesapeake to the care of the Collector, being so good as to note to me the cost which shall be remitted. Accept my salutations and assurances of esteem.[6]

Jefferson did not inquire about Campeachy chairs when he ordered hammocks from William Brown, perhaps implying that he already had an example of that seating form. It is possible that Elizabeth Trist brought one when she traveled to Virginia. If so, it would likely have been shipped disassembled and wrapped in a bundle, as was common in that era. In any event, Thomas Bolling Robertson would not secure a chair for Jefferson until mid-November 1819, more than a decade later. At that point, it would be the fourth at Monticello.[7]

The most explicit reference to Jefferson’s possession of a Campeachy chair during his presidency appears in an 1827 editorial in the Daily National Intelligencer, which lauded the work of Washington, D.C., cabinetmaker Henry Hill (1791–1850). A Campeachy chair in the front window of his shop on Capitol Hill was “made in the form of those Spanish Chairs introduced here by Mr. Jefferson.” The author praised the ingenious attachment by which the sitter could adjust the tautness of the leather, noted the novel addition of an adjustable writing surface on a pivoting arm, and reported that the State Department had ordered the chair, implying that it was destined for a very special client. The following year, the same writer praised Hill’s adaptation of a map case that was “a contrivance of Mr. Jefferson.”[8]

The reference to Spanish chairs “introduced here by Mr. Jefferson” suggests that a Campeachy chair had arrived in the Federal City during his presidency, for he never returned to Washington thereafter. If so, the written record provides no hint of what happened to the chair. There is no specific mention of a Campeachy chair in any of the inventories taken during Jefferson’s residence in the President’s House, the packing lists of goods shipped back to him at Monticello, or his own extensive accounts and correspondence. Similarly, no contemporaneous letter or diary maintained by a member of Jefferson’s social or professional circles alludes to his ownership of a Campeachy chair or confirms that the form had any special meaning to him.[9]

Evidence that Jefferson owned a Campeachy chair during his presidency is circumstantial but compelling. In a letter dated November 5, 1819, Jefferson thanked Thomas Bolling Robertson for sending a Campeachy chair from New Orleans despite a decade’s delay:

Accept my thanks . . . for the Campeachy chair, which you have been so kind to send to me, the arrival of which in Richmond is announced to me in a letter from your father. . . . Age, its infirmities and frequent illnesses have rendered indulgence in that easy kind of chair truly acceptable.

The last sentence suggests not only that Jefferson was well acquainted with the comforts afforded by Campeachy chairs but also that he may have owned an example earlier in his life. As a younger man, he may not have required “indulgence in that easy kind of chair,” which might explain why, if he had owned an example during his presidency, he never sent it home or mentioned it in correspondence for a decade afterward.[10]

If Jefferson owned a Campeachy chair in Washington, he may have given it to an acquaintance before he left—perhaps to one of the many talented artisans he admired in the city. Soon after Jefferson left Washington, the city’s finest cabinetmaker, William Worthington (1775–1848), began to experiment with Campeachy chair designs and by the mid-1810s was producing them. As with later artisans, Worthington looked to the Caribbean for inspiration, but he constructed the frames using heavier components. He also redesigned the arms, giving them a pronounced upward sweep with scrolled ends and, on the finest chairs, added elegant carved details (fig. 8). In the 1820s President John Quincy Adams purchased a Campeachy chair from Worthington, and President Andrew Jackson received one of Henry V. Hill’s chairs as a gift in 1827. Washington society unquestionably linked the form to the presidency.[11]

Neither Worthington nor Hill advertised Campeachy chairs, and in the 1810s few people other than politicians linked to Jefferson or members of the Latin American diplomatic corps knew of the form. One notable exception was merchant Moses Poor, whose auction advertisement in the December 5, 1817, issue of the Baltimore Patriot listed a secondhand “Spanish chair.” This is the earliest documentary reference to a Campeachy chair in the mid-Atlantic region. Furthermore, as secondhand furniture, Mr. Poor’s chair had probably been around for some time. There is no mistake that certain Washingtonians appreciated these chairs before they entered the popular realm, and that most of the owners were linked to Jefferson or his circle.

Whether Jefferson owned a Campeachy chair during his presidency remains a subject of debate, but he certainly knew of the form and seems to have inspired others to pursue it. Nonetheless, after his 1808 note to William Brown ordering hammocks, the statesman did not write the word “Campeachy” again for more than a decade. When Jefferson’s rheumatism finally grew troublesome, his friends in the Trist family took note of his condition and, in an act of kindness and gratitude, presented the aging former president with a custom-made chair that soon became his favorite.

Jefferson’s and Elizabeth Trist’s pair of matching Campeachy chairs owe their existence to a series of events that took place beginning in the summer of 1817, when her seventeen-year-old grandson Nicholas Philip Trist (fig. 9) completed his studies at the College of Orleans in New Orleans. The president invited Nicholas and his younger brother Browse (fig. 10) to come live with him and his family at Monticello. The young men said good-bye to their parents on the docks of New Orleans and set sail for Virginia. After a month at sea, their ship entered the Chesapeake Bay, and they disembarked at Norfolk, where they transferred to a smaller vessel for the trip up the James River to Richmond, and from there headed west. They visited family and friends en route, including Peachy and Mary Gilmer, and arrived at Monticello sometime shortly before Christmas, when they moved quietly into second-floor quarters. They had not visited Monticello for some time, and the seventy-four-year-old Jefferson had grown frail in the intervening years.

The boys were introduced to Jefferson by their grandmother, Elizabeth Trist. She had first met the statesman in December 1782, when he and his daughter Martha, known as “Patsy,” rented quarters in Trist’s mother’s Philadelphia boarding house during a four-month session of Congress. Despite the weight of politics, his mind was focused principally on family, for his wife, Martha, had died in the spring and left him with three young daughters to rear on his own. Jefferson observed Trist with her eight-year-old son Browse (1775–1804) and appreciated her parenting skills. Soon he asked her advice about family and child rearing and received her help with his daughter’s education while Patsy was in Philadelphia. When Congress adjourned in the spring and the delegates left Philadelphia, Elizabeth corresponded frequently with Jefferson and his daughter. The visit was the beginning of a friendship that linked their families through generations. It prompted Elizabeth to move from Philadelphia to Charlottesville in 1798 and subsequently brought Nicholas and Browse to Monticello for a long visit.[12]

During their year in Virginia, the boys visited back and forth between Monticello, their grandmother’s residence at nearby Farmington Plantation, and the family’s numerous friends. The trip was momentous for Nicholas, who fell in love with Jefferson’s sixteen-year-old granddaughter Virginia and hastily proposed, but then, in a surprising move, he applied to the academy at West Point and was accepted for the fall session.[13]

Just before Christmas, Nicholas wrote from Monticello to his new stepfather in Louisiana, Etienne St. Julien de Tournillon (1770–1857), and asked his help in procuring a bottle of perfume for his grandmother, four books for his studies, and a pair of Campeachy chairs with a circle of stars inlaid in the crest and expensive red morocco upholstery. Nicholas wanted them for two people who loomed large in his life—his grandmother Elizabeth Trist and Thomas Jefferson. Trist’s letter to his stepfather is now lost, but correspondence from various people over the next six months illuminate his gift. Dated January 25, April 10, May 7, and July 23, 1818, the letters provide subtle details of the order or hints at the character of the chairs. The correspondence lends invaluable insights into the layered relationships that shaped life and furniture making at Monticello. More important, they explain a series of entwined events that took place in Jefferson’s last eight years, which until now have confused historians.[14]

De Tournillon responded to his stepson’s letter on January 25. Writing from the family plantation in Lafourche Parish, de Tournillon acknowledged Nicholas’s request but mentioned no details. When Nicholas next heard from de Tournillon, his stepfather was in New Orleans on business. The latter’s letter, which conveyed news of family and business, was dated April 10 but composed over a period of perhaps two weeks or more. An early paragraph expressed frustration and outlined de Tournillon’s unsuccessful attempts to find an artisan capable of completing the work:

Now I will take care of searching for the various objects you have asked me for: but fear I will not be able to procure the two Campeche chairs having made several inquiries this morning which were fruitless. If between now and my departure [from the city] I am unable to get them completed, I nonetheless determine to have them made; they told me about a worker who could perfectly fit [the upholstery to] the form and could fulfill our aim.

Near the end of the letter de Tournillon added a paragraph that reported progress toward completing Nicholas’s request. De Tournillon appears to have commissioned the chair frames rather than purchasing upholstered examples that were among the stock-in-trade of a local maker or a furniture showroom or warehouse:

I ordered them from a cabinetmaker [ébéniste]. One will bear the cipher “T.J.” and the other “E.T.” In three days they will be ready, and I will register them with M [illegible] and Longer [?] to be sent . . . by the first ship that departs for Norfolk at the address you indicated.

This previously unpublished letter provides significant insight into the character and the quality of the chairs. The fact that three days were needed to finish the details strongly suggests that the wooden frames inlaid with stars were completed by the time he began the final portion of the letter, and at that point only the upholstery needed to be finished.[15]

Nicholas’s mother wrote from the family plantation in Lafourche Parish on May 7 to report that the shopping was completed and the furniture was ready for shipment. She apprised Nicholas that his old friend John F. Dumoulin would make the arrangements, yet also thought Nicholas should know that John had expressed certain reservations about the chairs:

The Chairs, books, a box of Cologne for your Grandmother and another box containing some trifles . . . were shipped for Norfolk on board the Schooner “William and Joseph” commanded by Captain Dogget, directed to [shipping broker] Moses Myers [of Norfolk]. Mr. Dumoulin says the chairs are not as handsome as they ought to be after the direction your Father gave the upholsterer.

It is significant that de Tournillon engaged an upholsterer instead of a saddler or leather worker to complete the chairs. Though New Orleans was by no means Paris, Nicholas’s aristocratic French-born stepfather engaged a skilled artisan to put the finishing touches on the chairs. This is implied by the desire to adorn the upholstery with customized ciphers—one with “T.J.” for Thomas Jefferson and the other with “E.T.” for Elizabeth Trist—and also by subsequent descriptions of the chairs. Although Dumoulin’s criticism of the finished upholstery initially seems confusing, on reflection, it makes great sense. Campeachy chairs traditionally had nothing more than a layer of cowhide to support the sitter. Therefore, Nicholas’s effort to have the chairs upholstered with delicate morocco leather or sheepskin, which would likely have been padded and buttoned, made the finished upholstery technically complex.[16]

One can only hypothesize how the artisan incorporated the ciphers “T.J.” and “E.T.” into the design. Perhaps he tooled or stitched the letters directly to the leather. More likely, he sewed the letters to a leather or fabric medallion and then sewed the medallion to the upholstery. Regardless, Nicholas’s star-inlaid chairs with red morocco upholstery and personalized monograms for Thomas Jefferson and Elizabeth Trist embodied finer materials and workmanship than others of their type and made an impressive statement.

Nicholas Trist’s old friend John Dumoulin wrote the fourth letter from New Orleans concerning the chairs on July 23. He apprised Nicholas that the crated chairs reached Baltimore on June 20 aboard the ship William and Joseph and were sent back down the Chesapeake on a small schooner to agent Moses Myers of Norfolk. Myers quickly arranged portage up the James River to Richmond, and agent Bernard Peyton, who oversaw their transfer to a flat-keeled bateau, sent them up the James River Canal toward Albemarle. When the craft reached the tiny town of New Canton two days later, the bateau men steered the vessel north up the winding Rivanna River, then slowly poled it the twenty miles up the sandy shoals toward the landing at Milton, the tiny community that Jefferson had struggled to promote within sight of his birthplace at Shadwell. Whether the Trists’ or Jefferson’s servants met the craft at the dock is unknown, but ultimately the pieces traveled up the winding mountain road to Monticello.[17]

There is no record of either Jefferson’s or Trist’s responses to the chairs. Nonetheless, Martha Randolph was sufficiently pleased that she mentioned the president’s chair shortly thereafter in an undated letter to her daughter-in-law Jane Randolph (1798–1871). Likely written in July, before the heat of summer had broken, this piece of correspondence provides the first known reference to a Campeachy chair at Monticello: “Tell Jeff [Jefferson’s grandson and namesake Thomas Jefferson Randolph] that Grand Father’s alcove is most temptingly cool and an elegant Campeachy chair at the foot [of the bed has been] arranged expressly for his accommodation.” Sadly, Jefferson would enjoy the chair but a short time before illness descended on him. His rheumatism had grown quite troublesome during Nicholas’s stay, and on August 1, 1819, he borrowed $100 from his agent James Leitch to pay for room and board and traveled some thirty miles west for a retreat at the Rockfish Mountain House with a committee entrusted with founding the University of Virginia. From there he continued to the spa at Warm Springs, in Bath County, a hundred miles west through the mountains.[18]

When Jefferson arrived at the spa on August 7, he immersed his aching body in the hot sulfur water and then increased the treatment over the course of a week from one to three times daily, as the doctors prescribed. He was so comforted by the results that he wrote Martha, “I may presume the seeds of my rheumatism eradicated,” but within days he contracted a staph infection that resulted in an outbreak of boils and cankers. When the physician prescribed a topical ointment of sulfur and poisonous mercury, Jefferson’s health went into rapid decline: “These reduced me to death’s door,” he later wrote a friend. Jefferson proclaimed the trip home the most painful of his life and then lay sick at Monticello for nearly three months, much of it prostrate—unable to appreciate the chair or anything else in his purview.[19]

The next year would be equally trying, as, still weak from the previous summer’s treatment, Jefferson suffered added stress from the nationwide Panic of 1819 and deepening financial troubles. The depth of the crisis had become obvious by the time he arrived at Poplar Forest in August and possibly precipitated the attack of rheumatism he soon experienced—his most virulent yet. On August 24, unable to sit upright and work for an entire day, he wrote Martha:

While too weak to sit up the whole day, and afraid to increase the weakness by lying down, I long for a Siesta chair which would have admitted the medium position. I must therefore pray you to send by Henry the one made by Johnny Hemings. If it should be the one Mrs. Trist would chuse, it will be so far on it’s way, if not, the wagon may bring hers when it comes at Christmas.

Jefferson rarely expressed such vulnerability, yet in longing for a Campeachy chair and praying that Henry would deliver one “made by Johnny Hemings,” he provides crucial documentation about his slave joiner’s work at Monticello. It is significant, as well, that in his very next thought, Jefferson asked his daughter Martha to inquire of Mrs. Trist whether she believed one of the Louisiana chairs or John Hemings’s example would best relieve his pain. In addition to deferring to Trist’s knowledge of Campeachy furnishings, as he had in the past, Jefferson relied on his friend to determine which chair would provide him the most comfort.[20]

The exchange also raises the question as to whether one of the Louisiana chairs provided the prototype for John Hemings, or whether he looked elsewhere for inspiration. The answer appears clear if one consults the documentary record and surviving objects. There is no evidence that any other Campeachy chair was at Monticello before the arrival of the Trist chairs in August 1818. Furthermore, the Campeachy chair that Thomas Bolling Robertson announced he was sending to Jefferson would not arrive until mid-November 1819. In short, the Trist Campeachy chairs were the only examples of their type available at Monticello when John Hemings first copied the form.[21]

In 1820 Elizabeth Trist gave her Campeachy chair to Peachy Gilmer. Jefferson agreed to facilitate its delivery by permitting the exchange to take place at Poplar Forest, sixteen miles from the Gilmers’ new home in Liberty. It is uncertain whether Trist or Jefferson was responsible for informing Gilmer of the details, but regardless, a miscommunication or an undelivered letter frustrated the intended gift, and early in 1821 Gilmer initiated an exchange with Jefferson, hoping to finalize the arrangements:

Mrs. Trist some time ago presented me with a Campeachy chair, which had been sent for her to Monticello, and informed me that you had been so obliging, as to offer to send it to Poplar Forest. I have since heard nothing of it and should be glad to get it. . . . I should not have troubled you with any notice of the matter, but presume that amongst concerns of much more importance, it has been forgotten.

Jefferson responded that the chair had been “sent to Poplar Forest the summer last, and has only awaited the order of Mrs. Trist or of yourself. I write Mr. Yancey this day to deliver it to any person under your order.” Jefferson’s letter of confirmation to Yancey was especially careful to distinguish the chair he had received from the one destined for Gilmer—which also happened to be at Poplar Forest:

There is an armchair at Poplar Forest, in the parlor, which was carried up in the summer, and belongs to Mrs. Trist. It is cross-legged covered with red Morocco, and can be distinguished from the one of the same kind sent up last by the wagon as being of brighter fresher colour, and having a green ferret across the back, covering a seam in the leather. Be so good as to have it delivered to Mr. Gilmer when called for.

This correspondence is of paramount importance, for it demonstrates that Nicholas’s chairs did not just have expensive upholstery with a cipher of entwined initials but, more specifically, red morocco leather. That the chairs had delicate sheepskin upholstery was unprecedented for a Campeachy chair and helps to explain Nicholas’s mother’s comments about “the direction your father gave the upholsterer” before the chairs were shipped north to Nicholas.[22]

Jefferson’s letter supports earlier references suggesting that the two Louisiana chairs were very much alike, even though he stated that Trist’s example had a “brighter fresher colour.” This might imply the two differed from the beginning but more likely indicates different usage. Later accounts show that Jefferson kept his chair near the doors that opened from Monticello’s parlor to the south lawn and that he sat at that location for hours on end to catch the breeze or savor the sun. Three years of exposure to sunlight would have caused the wooden and leather components of Jefferson’s chair to fade enough to distinguish it from Trist’s. He also noted that her chair had a “green ferret,” which suggests that both Campeachys originally had contrasting strips of leather covering a seam in their backs and that Jefferson’s was missing, or that a seam had opened up in the back of Trist’s chair and the ferret was added to cover it.[23]

The only significant group of contemporaneous Virginia Campeachy chairs—those made by John Hemings—was clearly inspired by the Louisiana examples owned by Jefferson and Trist, which aligns with documentary evidence suggesting that the latter seating forms were the first of their type in Albemarle County. Of the three chairs that form the core of the Hemings group, the earliest has a history of ownership by Joseph Carrington Cabell (1778–1856) (fig. 11), and the other two by General John Hartwell Cocke (1780–1866) (figs. 12, 13). In the last eight years of his life, Jefferson spent as much time with those two men as any others in his circle, focused intently on their shared goal of founding a new University of Virginia. All three chairs have long-standing and credible traditions of having been made at Monticello and presented by Jefferson to their owners.[24]

Just as one must understand Jefferson’s four-decade friendship with the Trist family to comprehend the significance that he attached to their Campeachy chairs, one must acknowledge his abiding friendships with Cabell and Cocke to understand their examples. Joseph Carrington Cabell of Edgewood (fig. 14) and Jefferson were intensely involved between 1815 and the latter’s death in 1826. During the economic turmoil that enveloped the United States between 1819 and 1824, Senator Cabell personally shepherded a series of crucial funding bills for the university through a resistant Virginia legislature. When the school finally opened its doors for classes in March 1825, it was the culmination of Cabell’s relentless diplomacy and endless attention to detail. He demonstrated his commitment by serving thirty-seven years on the school’s Board of Visitors, including two terms as its Rector, or chairman (fig. 15). Jefferson, who receives credit as the school’s founder, acclaimed Cabell “the main pillar of the university” and acknowledged his role in the fulfillment of the former president’s last great legacy.[25]

There is no documentation detailing when Cabell obtained his Campeachy chair or whether he received it by gift or purchase, nor is it clear that he attended the five-day Monticello dispersal sale that commenced on January 15, 1827. Family tradition asserts that the chair descended from Joseph to his favorite nephew, Nathaniel Francis Cabell (1807–1891), who, like his uncle, was born at the family seat, Liberty Hall. The two men corresponded frequently throughout their lives, and Nathaniel devoted years to editing and annotating the four hundred letters that Joseph and Jefferson exchanged while establishing the university. It is questionable whether Joseph lived long enough to see the published volume, which Nicholas titled The Early History of the University of Virginia, as contained in the letters of Thomas Jefferson and Joseph C. Cabell (1856). If the book provides detailed testimony of Joseph’s intense relationship with the president, it likewise underscores Nathaniel’s abiding devotion to his uncle. Nathaniel’s dedication to Jefferson’s legacy secured his ownership of this Monticello-made Campeachy chair.[26]

The Cabell chair is the closest to the Louisiana prototype (figs. 2, 3), but one must carefully compare the sturdy oak chair with its more refined mahogany model to understand the decisions that John Hemings made in the Monticello joinery. The delicacy of the Louisiana originals and the process by which they evolved in the tropical Caribbean during the late eighteenth century had little relevance to a Monticello slave. This is especially pertinent if one considers damage that occurred to Elizabeth Trist’s chair soon after its arrival and the way in which Hemings interpreted that design for a Virginia plantation.

Shortly after the Trist chair arrived in Virginia, it fell backward, cracking the crest from side to side and shattering the joints that held it. A carpenter reglued the crack but trimmed 2 1/2" at the top of the damaged posts. A blacksmith then reinforced the damaged area by hammering an iron strap over each joint, shaping the metal to conform in back and front and securing the straps with screws (fig. 16). The shortened posts altered the chair’s proportions, and the iron repairs were a bit unsightly, but they provided the only means to stabilize the damage and permit the object’s continued use.[27]

It is possible that the repairs took place at Monticello and that John Hemings performed the woodwork and blacksmith Joseph Fossett (1780–1850) the ironwork. The two men worked together closely over the years, collaborating on some of Jefferson’s most ambitious projects, including his four-horse carriage—for which Hemings crafted the elegant wooden frame and Fossett the iron springs and mounts. Fossett’s metal straps reinforced the carriage structure and helped it withstand the rigors of Virginia’s unpredictable roads.[28]

It appears that Elizabeth Trist also asked the workmen to alter the chair to shorten the height of the front feet, suggested by the unnaturally steep slope of the arms and the vertical pitch of the back—which, at sixty-eight degrees, is more upright than those on most Caribbean examples. That theory is supported by the fact that the tips of the front legs lack the characteristic kick, or slight outward flare, found on most Louisiana examples and on Hemings’s copies. One can only hypothesize why this happened, but it probably took place soon after Trist acquired the chair. Though history records nothing of her height, one might surmise that the front legs were so tall that the seat’s front pressed on her legs and impeded circulation. Then again, it is possible that the original slope of the back made the chair unsuitable for eastern seating customs. After all, casual in Virginia has never been quite so casual as in Louisiana.[29]

John Hemings had little option but to rely heavily on the Louisiana chairs for his design. Other than a few short trips beyond Virginia’s borders, the joiner spent his lifetime confined to Jefferson’s plantations and had few if any opportunities to acquire knowledge of Caribbean seating forms. Even if one acknowledges his considerable talents, it is otherwise impossible to imagine that he could have so closely emulated the Jefferson and Trist chairs unless he directly relied on them for inspiration. One can only speculate about the length of time that he produced chairs in the Monticello joinery, but no more than eight years could have passed between Hemings’s initial copy in 1819 and the Monticello dispersal in January 1827. After his wife, Priscilla, died in 1830, he essentially retired, and the nephews who learned the trade at his side relocated to Charlottesville.[30]

Details shared by the Hemings chairs and Campeachy chairs owned by Jefferson and Elizabeth Trist include the distinctive scoop of the seat, shape of the front rail, slope of the back, high rounded crest, straight stretchers, and a sloped edge on the back of each post as it tapers near the top. He also adopted the long serpentine arms with scrolled ends found on the Louisiana examples, although he made his versions leaner and set them parallel to the ground, in keeping with conventional Virginia armchairs. The use of oak as a primary wood on the Hemings chair could reflect either his or Jefferson’s preference. Neither had used or specified that oak be used for furniture or interior woodwork before 1808, but both men relied on it for structural framing at Monticello and Poplar Forest. During the 1810s changing tastes finally made it acceptable to acknowledge oak’s beauty as a finished wood, and by 1820 it became so fashionable that some of Jefferson’s closest friends hired painters to imitate oak on interior doorways and paneling. Among those were Jefferson’s neighbor and good friend General John Hartwell Cocke (1780–1866), who completed the interior of his new home Bremo in Fluvanna County, Virginia, in the late 1810s. Cocke also purchased a formal oak armchair as the principal seat in his library.[31]

Durability may have influenced the use of oak for Hemings’s Campeachy chairs, which was no small consideration in light of their potentially vulnerable form. “All of the floors of Europe are oak,” Jefferson reasoned when instructing carpenter John Perry to install them at Poplar Forest, “So are the decks of ships.” Jefferson called for oak floors throughout the house and oak planking out the side door for the “terrace”—the deck over the servants’ wing that stretched far into the garden. This elevated walkway allowed him to survey the orchards and gardens above the bustle of daily activity, but it was exposed to weather and required upkeep. No comprehensive inventory of his lumber survives, but Jefferson likely kept a reserve so his slaves could replace weathered boards when needed. The Poplar Forest floors and terraces are made of 1 1/4" oak planks—precisely what Hemings used for the framing of his Campeachy chairs.[32]

In addition to being durable, oak was cheap. Jefferson’s financial situation had declined since his retirement and with the Panic of 1819 became dire. When the international wheat market collapsed in the summer, his principal source of income plummeted. A local drought then devastated the Virginia crop and impeded its shipment down shallow rivers. In May, long before anyone realized the depth of the depression—Jefferson wrote to farm manager Joel Yancey and lamented: “To owe what I cannot pay is a constant torment.”[33]

The joinery of Hemings’s chairs was likewise derived from that of the Louisiana examples. None of these examples has assembly marks (typically Roman numerals aligning tenons and mortises), and all have through-tenons at the same joints, including the juncture of the crest to the back stiles, the front rail to the seat, and each stretcher to the adjoining legs (fig. 17). Hemings also followed the Louisiana prototypes by using blind-tenons for the joints connecting the arms to the back and the arm supports to the seat rails. The only joinery deviations from the prototypes are minor and reflect habits he had developed earlier in his career: the addition of a through-tenon where each arm support connects to the adjoining arm; and the use of pins and wedges to secure the joints (one for small joints and two for large ones). Hemings generally inserted each wedge about 1/4" from the short end of the tenon.

When making the chairs, Hemings took two shortcuts that he learned at the Monticello joinery. He and his master James Dinsmore (ca. 1771–1830) typically used tenons with a shoulder on just one side. Although the technique is not unique to the Monticello joinery, it reflects an unusual approach to construction and is a helpful diagnostic tool, because most tenons had shoulders on two or even four sides. One can distinguish the technique even on an assembled piece, because three edges of the mortise can usually be seen on the unshouldered edges of the tenon. Hemings also used screws for structural reinforcement (fig. 18), a technique he likely learned from Dinsmore, who followed that practice when installing woodwork at Monticello and making furniture for Poplar Forest. As on the Louisiana prototype, Hemings half-lapped the chair legs where they crossed, but he took the added precaution of countersinking three screws where they could not be seen—on the inner face of the crossing, beneath the seat. He placed the two lower screws 2 5/8" apart and inserted the third about an inch above their midpoint, forming a triangle that pointed up. Louisiana chairs rarely employ screws, and when they do, they generally have just one. However, it is questionable whether most of the single screws on Louisiana chairs are original or represent later efforts to tighten loose joints.[34]

The crests of the Cabell and Trist-Gilmer chairs originally may have been even closer in size since oak shrinks less than mahogany. Hemings appears to have encountered trouble making wooden patterns for the legs—perhaps because the flared arms of the Louisiana original got in the way—and may have used paper or pasteboard, instead. The use of flexible patterns might explain why the crossing of the legs and spacing of the feet on his chairs differ slightly from those on the Louisiana examples, despite Hemings’s effort to approximate their dimensions.

There is no indication that any of the Monticello artisans had much experience with upholstery, and in light of Jefferson’s precarious financial position in the fall of 1819, it seems unlikely that he would allow experimentation with expensive morocco leather or assume the expense of sending Hemings’s chairs to an upholsterer. As a result, the joiner covered his chairs with heavy cowhide. Unlike most upholsterers in the Caribbean, he did not nail the hide along the vertical outer edges of the frame but instead secured it on the front of the seat and posts.[35]

Two Campeachy chairs that originally belonged to General John Hartwell Cocke are accompanied by oral tradition, which maintains that Jefferson had the chairs made at Monticello and gave them to Cocke. Without discounting this oral history, one must also acknowledge documentation that Cocke acquired “chairs” at the 1827 Monticello dispersal sale. Indeed, he recorded a total of $206.35 in his accounts “for purchases at Monticello” and signed a bond to Jefferson’s estate that allowed him to defer payment until July, presumably after the sale of summer crops. He subsequently recorded details of the purchase in his daybook, noting it as a “Household Expense” that included $126 for a “clock, medallion, and chairs” and $80.35 paid to Nicholas Trist for a “theodolite & sextant.” It is uncertain whether the reference to chairs included any Campeachy chairs.[36]

Cocke’s correspondence and accounts are among the most comprehensive to survive from any southern plantation. Although they provide significant insight into his and his wife’s extensive furnishings, they yield no further information about his acquisition of Campeachy chairs. These may be the chairs that Cocke purchased at the dispersal sale, though it is generally believed that only the two Campeachy chairs listed in the Monticello parlor were sold at that time. However, there may have been other Campeachy chairs on the property that were not counted in the inventory. Among the plethora of seating furniture that passed down through Cocke’s descendants, none but the two Campeachy chairs has been shown to bear a relation to any of Jefferson’s well-documented Monticello seating furniture. It is possible, but unlikely, that the chairs were among furnishings later dispersed at Poplar Forest; that auction, however, was poorly documented.

Whether Cocke acquired the chairs by purchase or gift, his ownership of the form makes great sense when one understands his close friendship with Joseph Carrington Cabell and layered ties to Thomas Jefferson. In 1819 Jefferson appointed Cocke to the University of Virginia’s first Board of Visitors. The board, in turn, appointed Jefferson and Cocke as sole members of the school’s Building Committee, delegating to them the authority “to advise and sanction all plans and the application of moneys for executing them.” Cocke served on the board until 1852—just four years short of Joseph Cabell’s unparalleled tenure—and played a seminal role in the university’s early development.[37]

Cocke loved education and abhorred slavery. He had an abiding conviction that the South possessed the wisdom to resolve the slavery issue on its own and, for decades, devoted his energies and resources to that goal. He served as vice president of the American Colonization Society, which aspired to educate and train slaves in preparation for a return to Africa and, in 1822, purchased a plantation in Alabama that he hoped would become a model for the future. He sent his slaves there to learn carpentry, weaving, and farming and participate in self-government as they prepared for freedom. In 1834, when a strident Virginia legislature forbade all education of slaves in the wake of slave Nat Turner’s rebellion, Cocke personally taught those in his charge to read and write and gave them religious instruction. He then built a chapel where they could freely worship and discreetly study their lessons. Few Virginians promoted greater self-sufficiency or trade skills among African Americans. Fewer still would have understood the layered significance of a slave-made Campeachy chair.[38]

Side-by-side comparisons of Joseph Carrington Cabell’s chair with the two later examples owned by John Hartwell Cocke provide meaningful insights into John Hemings’s decision-making process (fig. 19). Circumstances suggest that he cut a wooden pattern for the arm from the Trist chair, and, though he made it slightly leaner where the chair engages the rear post, he replicated this adjusted dimension when he constructed all three of his chairs (figs. 20, 21). Yet, in contrast to the sharp edges on the Trist-Gilmer arms and the slight softening of edges on the Cabell chair, he rounded those of the first Cocke chair somewhat more.

The most significant change to the first of Cocke’s chairs was making the crest rail 2" higher and extending the rear posts correspondingly. Though it gave the Campeachy a decidedly more vertical emphasis, other features remain largely the same, including the use of half-shouldered mortise-and-tenon joints, tiny round pins, and wedges, all in the same locations (figs. 22, 23). Hemings likewise used three screws to secure the legs where they cross, though on the Cocke chair he placed them in a triangular pattern pointing down, rather than up (fig. 24).

The ogee arm supports that survive on two of Hemings’s three chairs indicate that he relied on the Trist chair as his model (fig. 25). The shallow joints on the Trist chair’s arm supports were damaged and reset at an early date and those on the Cabell chair broke and were improperly replaced. Their loss suggests that the delicate mortise-and-tenon joints that Hemings copied from the Louisiana prototypes were inadequate to hold them in place, and he subsequently abandoned the model for a stronger through-tenon when he made the two Cocke chairs. It therefore appears significant that Hemings responded to the problem by choosing through-tenons to secure the arm supports for the Cocke chairs and thus overcame one of the Louisiana form’s structural shortcomings. Indeed, with Hemings’s choice of 1 1/4" stock for the legs and seat rails, he could rely on a joint that was impossible to achieve on the thin rails of Louisiana chairs. Other woodworkers who looked to Hemings’s seating for inspiration relied on this improved joint.

The second Cocke chair and, from a chronological standpoint, the third Campeachy in the Hemings’s group is made of ash rather than oak. The slave joiner’s hand is evident in numerous features copied from the previous chairs: arms cut from the same pattern; straight sawn stretchers at the front and rear; legs reinforced at their crossing with three screws; flared foot tips at the front and rear; half-shouldered through-tenons that are pinned and wedged; a rounded seat rail with a squared edge along the lower front; softened edges on the crest; and a sloped edge on the back of each post as it tapers near the top. At the same time, the second Cocke chair has several details that set it apart from Hemings’s earlier work, suggesting that another workman may have been involved. The arm supports are broader and more noticeably arched than those of the previous two, garnet-shaped finials cap the rear posts, and the design of the legs is simpler where they cross.

The third Hemings chair is crucial to understanding two related chairs that are simpler in style and execution. These chairs represent the work of another artisan or artisans and are slightly later in date than the Hemings chairs. The first is constructed of oak, upholstered in cowhide, and has brass upholstery nails (fig. 26). This chair has a history in the Matthews County Courthouse—some 140 miles east of Charlottesville and Monticello. The other is made of maple and descended from planter Robert Temple Gwathmey (1808–1889) of Canterbury, King and Queen County, Virginia (fig. 27). Although it differs slightly in scale from the chair with the Matthews Courthouse association, it undoubtedly came from the same workbench.[39]

How two Campeachy chairs inspired by work from the Monticello joinery found their way to eastern Virginia is uncertain, though circumstances suggest several possibilities. A number of King and Queen County families have strong ties to Albemarle County, as evidenced by the extended Walker family, whose descendants have lived in both areas for generations and were closely associated with Jefferson. Similarly, woodworking artisans in Matthews County had many connections to Jefferson’s circle. Richard Billups (1782–1843), who oversaw construction of the Matthews Courthouse in the early 1830s, had family ties to Albemarle County. His cousin Thomas Billups (1771–1845) worked with Albemarle builder Martin Thacker in constructing the plantation house at Redlands for Jefferson’s close friend Robert Carter. Billups subsequently worked with Lynchburg builder Silas Heston, who constructed the Bedford County Courthouse circa 1830.[40]

Stylistically, the Campeachy chairs illustrated in figures 26 and 27 are almost identical. Each has a boldly arched crest, S-shaped arms, ogee arm supports, straight stretchers at the front and rear, and a seat rail that is rounded on top and comes to a pointed edge running from side to side in front—all characteristics of Campeachy chairs in the Hemings group. The chairs also have rear posts topped by garnet-shaped finials related to those on the second Cocke chair (fig. 13). The two simple variants are likewise related to Hemings chairs in having their leg junctures reinforced with screws, though on the former the maker used four fasteners in a square configuration, rather than three in a triangle, as on the Monticello joinery chairs.

One feature elevates the Matthews and King and Queen County chairs above the earlier examples: each has a piece of padded leather nailed to the front of the arched crest, which served as a pillow or cushion. As the original upholstery on the Matthews Courthouse chair shows, the leather seems to have come from a saddler, who created a neoclassical guilloche border around the back and stamped a fylfot design into the center of the padded crest. The fylfot is otherwise unknown in eastern Virginia and may further indicate ties to Albemarle and the western piedmont, where Germanic and Scottish culture had a strong influence. Stamped decoration is otherwise unknown on Virginia Campeachy chairs, but it is common in Louisiana and the Caribbean, where leatherworkers and saddlers proliferated.[41]

Despite the fine quality of the leatherwork, neither of the two chairs has the subtle refinements of style or construction found in Hemings’s work. The garnet finials are crudely cut, and the arm supports are unexpectedly heavy. Furthermore, the edges of the arms and rear posts are chamfered, rather than rounded. Likewise, the joints are considerably simpler, for none is pinned, and only four have through-tenons—those that secure the arm supports to the seat rails and the arms to the rear posts. In contrast to all the other Virginia Campeachy chairs, the tenons on these later chairs have no wedges.

Despite these structural departures, the chairs illustrated in figures 26 and 27 are sufficiently similar to Hemings’s work to suggest that they may be by an artisan who had worked with him at Monticello or had convenient access to his products. Relatively few artisans meet those criteria, for almost everyone who worked in the Monticello joinery had long since departed by August 1819, when Hemings is documented to have made a chair. From that point onward, only two other individuals are known to have worked at the joinery: Hemings’s nephews James “Madison” Hemings (1805–1877) and Thomas “Eston” Hemings (1808–1856), sons of John’s half sister Sally Hemings. Historians believe that the brothers apprenticed with their uncle from age seventeen, implying that the young men were actively involved, respectively, from 1822 and 1825 onward. They were the most logical heirs to Hemings’s woodworking legacy and to any patterns he may have had.[42]

Jefferson freed John, Madison, and Eston Hemings in his will, but it is possible that all three continued to work intermittently at Monticello over the next four years. However, by the time John Hemings’s wife, Priscilla, died in 1830 and he buried her beneath a tree at Monticello, his nephews were established in Charlottesville. Although John Hemings worked relatively little after his wife’s death, Eston and Madison remained active in the woodworking trades. Unfortunately, material evidence for the brothers’ building and furniture ventures in these later years remains lacking.[43]

When a census taker encountered the light-skinned Hemings family in Charlottesville in 1830, he identified twenty-two-year-old Eston Hemings as a white male and head of a household that included a second “white” male in the twenty to twenty-nine age bracket—presumably his twenty-five-year-old brother Madison—and a white female aged fifty to fifty-nine—presumably their fifty-seven-year-old mother, Sally Hemings. In addition, six slaves lived in the house, some of them probably members of the extended Hemings family. The building stood at the corner of Fourth (now Union) and Main streets, just two blocks downhill from the Albemarle Courthouse, in a community of skilled artisans. Although Sally and Madison Hemings seem to have lived with Eston at the time of the census, they later moved to West Main Street, perhaps to be near the university community.[44]

Another artisan merits consideration for his possible role in producing the later Campeachy chairs. Monticello historian Diane Ehrenpreis cites an oral tradition in which Albemarle County cabinetmaker John Fowler purchased a Campeachy chair at the 1827 Monticello dispersal sale. Unfortunately, neither Fowler’s auction purchase nor his furniture products are firmly documented. Nonetheless, his home and shop stood at the corner of East Main Street and Court (now Fifth) Street in Charlottesville—just a block east and diagonally across the street from the Hemings home and shop. The two men must have known each other in the tightly knit community. If indeed Fowler owned a Campeachy chair from Monticello, then his proximity to Eston Hemings may have contributed to the continued production of the form in the area. Yet regardless of the chairs’ origin, their existence in the Tidewater attest to the spreading reputation for Jefferson’s Campeachy chairs in the years following his death.[45]

The five Campeachy chairs that are the focus of this article have spurred new research into Thomas Jefferson, his inner circle of friends, and the products of the Monticello joinery. They represented a distinctive new chair form that evolved in the Caribbean in the late eighteenth century, gained popularity in New Orleans, and, after Thomas Jefferson acquired the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, found their way to the eastern United States.

The earliest of the type documented at Monticello consists of a pair having stars inlaid in the crest and red morocco upholstery. Previously unstudied letters make it possible to document conclusively that Nicholas Trist custom-ordered the chairs from New Orleans for his grandmother Elizabeth Trist and retired President Thomas Jefferson. Each chair had a cipher in the leather for its new owner—“T.J.” and “E.T.” respectively—and they arrived at Monticello in the summer of 1818.

One cannot comprehend the meaning of the star-inlaid chairs as a reflection of family and friendship without acknowledging that in 1824 Nicholas Trist returned to Albemarle to marry Jefferson’s granddaughter Virginia and became the president’s personal secretary. The young couple lived at Monticello, where they helped to care for the aging Jefferson, were with him when he died, and laid him to rest in the family graveyard. Nicholas and Virginia likewise cared for Elizabeth Trist, who lived with them at Monticello after 1826 and remained there through her final illness. Virginia sat vigil at Elizabeth’s deathbed in 1828 and, with a circle of family and friends, oversaw her burial in a mountainside grave near the president at a time when Nicholas was away.

The chairs played more specific roles, as well. They provided the president a retreat from the discomfort of aging and the two families nurtured exchanges between three generations. They provided John Hemings a Louisiana prototype that he adapted for use on a Virginia plantation, encouraged others in the region to make the form, and inspired Jefferson’s closest friends to acquire examples that bespoke their ties to him. The recent discoveries concerning the first Campeachy chairs at Monticello combine to create a remarkable story of family history, race, and material culture in the neoclassical South.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank H. Parrott Bacot, Luke Beckerdite, Kate Bruce, Robert W. Conner, Michael Connors, Elizabeth Chew, Michele Doyle, Gordon F. Erby, Diane Ehrenpreis, Boo Evans, Edward Evans, Melinda Frierson, Kim May, Peter Patout, “Chip” Pottage, Jonathan Prown, Grant Quertermous, Martha Rowe, Peter and Fleda Ring, Robert L. Self, David Skinner, Judy Stevens Smythers, Susan Stein, Kate Swisher, Carrie Taylor, and Warren Woods.

Robert Self and Susan Stein briefly discussed the chair in “The Collaboration of Thomas Jefferson and John Hemings,” Winterthur Portfolio 33, no. 4 (1998): 240. See also Diane Ehrenpreis, “The Seat of State: Thomas Jefferson and the Campeachy Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010), pp. 28–53. Jack D. Holden, H. Parrott Bacot, Cybèle T. Gontar, Brian J. Costello, and Francis J. Puig, Furnishing Louisiana: Creole and Acadian Furniture, 1735–1835 (New Orleans, La.: Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010), pp. 344–65. Cybèle T. Gontar, “American Campeche Chair,” Antiques 175, no. 5 (May 2009): 88–95; Cybèle Trione Gontar, “The Campeche Chair in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 38 (2003): 183–212.

Jefferson’s father, Peter Jefferson (1708–1757), was a close friend of Dr. George Gilmer I (1700–1757), the Scottish-trained physician who became mayor of Williamsburg. Thomas Jefferson probably met Dr. George Gilmer II (1743–1795) while attending the College of William and Mary. Gilmer settled in Albemarle during the 1770s, when he married a daughter of Dr. Thomas Walker and lived principally at Pen Park. Peachy Ridgway Gilmer was their son. John Gilmer Speed and Louisa H. A. Minor, The Gilmers in America (New York: printed privately, 1897). Financial reversals made it necessary for the Gilmers to resettle in 1806 on an unimproved parcel of land near Henry Courthouse (now Martinsville), which he inherited from his parents. Liberty grew up around Bedford Courthouse. The Gilmers frequently visited Jefferson at Poplar Forest.

The son changed the spelling of his name from Blaetterman to Blatterman. Although Blatterman recollected half a century later that the chair had thirteen stars in the crest, the surviving chair of the pair has but twelve. Assuming that Jefferson’s chair was intended to have thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies, one must conclude that the maker miscalculated the number, or perhaps was superstitious about the number thirteen. “Memoirs of George Walter Clements Blatterman,” ca. 1902, MSS 10233, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library (hereafter ASSSCL), University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Ehrenpreis, “Seat of State,” p. 37. Thomas B. Robertson to Thomas Jefferson, August 2, 1819, Thomas Jefferson Papers (hereafter TJP), Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Robertson’s position as United States representative from Louisiana for six years between 1812 and 1818 likely increased his travel between Washington, D.C., and Louisiana.

After Hore Browse Trist’s death in 1804, Jefferson appointed his wife’s brother, William Brown, to fill the position of customs collector. In 1808 Mary Brown Trist married Philip Livingston Jones and relocated to the Trist property on the Mississippi. Following his death in 1810, she married Etienne St. Julien de Tournillon (1770–1857). Jefferson returned permanently to Albemarle shortly after James Madison’s inauguration on March 4, 1809.

Thomas Jefferson (Monticello) to William Brown (New Orleans), August 18, 1808, Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts (hereafter CCTJM), Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. Jefferson requested three hammocks: one for Monticello, one for his son-in-law Thomas Mann Randolph, and the third for Mrs. Trist. Brown delivered the three hammocks to the port on October 6, but the ship went down at sea. The events are documented in “William Brown Campeachy Shipping Manifest,” October 6, 1808, TJP; William Brown to Thomas Jefferson, October 10, 1808, TJP; Martha Jefferson Randolph to Thomas Jefferson, February 17, 1809, CCTJM; Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, February 27, 1809, CCTJM; Thomas Jefferson to William Brown, May 22, 1809, TJP. Campeachy hammocks are best understood by a letter written from Lewis Livingston to Nicholas P. Trist, June 6, 1819, Nicholas Philip Trist Papers (hereafter NPTP), University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The letter states that “hammocks of that description or resembling them ought to be introduced in our armies as part of the outfit of every soldier—They are not expensive, very durable, and easily carried and would free the men from all danger of those numerous complaints caused by the cold and moisture of the earth.” Thomas Jefferson (Monticello) to William Brown (New Orleans), August 18, 1808, CCTJM.

Northern manufacturers frequently shipped disassembled chairs to the South tied tightly together in bundles or, if in large groups, packed in crates. Local merchants and cabinetmakers would reassemble them after arrival and market them. See John Kenney, The Hitchcock Chair (New York: C. N. Potter, 1971), pp. 54–56.

Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), July 28, 1827, and October 21, 1828. In the 1820s Hill’s shop stood on New Jersey Avenue, near the Capitol Building.

The terms “Spanish chair,” “Campeche chair,” and “Campeachy chair” are interchangeable. See further Jay Dearborn Edwards and Nicolas Kariouk Pecquet du Bellay de Verton, A Creole Lexicon: Architecture, Landscape, People (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004), p. 25. The word “Campeachy” was utilized in the Anglo-Atlantic world as an Anglicization for the port of Campeche in Mexico. The word “Campeche” does not appear in any English-language newspaper, even though the word “Campeachy” is used as early as the 1780s. It is possible that the inventory takers in that era did not recognize the unfamiliar chairs or used vocabulary that is now so unfamiliar—or so general—as to be meaningless for modern-day historians attempting to trace the form in the region by relying on documents.

Ehrenpreis (“Seat of State,” p. 39) believes that the chair that descended in the family of Thomas Jefferson Randolph of Edgehill (1792–1875) is the chair Thomas Bolling Robertson sent to Jefferson. Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Bolling Robertson, November 7, 1819, TJP.

Worthington’s earliest Campeachy chairs appear to date from the mid-1810s (Sumpter Priddy and Ann Steuart, “Seating Furniture from the District of Columbia, 1795–1820,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010], pp. 121–26).

Elizabeth Trist played a central role in Patsy’s life in the years following her mother’s death and oversaw much of her education while in Philadelphia. Jefferson emphasized to his daughter how important he felt Trist was for their family: “As long as Mrs. Trist remains in Philadelphia cultivate her affections. She has been a valuable friend to you and her good sense and good heart make her valued by all who know her and by nobody on earth more than by me.” Thomas Jefferson (Annapolis) to Martha “Patsy” Jefferson (Philadelphia), November 28, 1783, in The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Edwin M. Betts and James Adam Bear Jr. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1986), p. 19.

Elizabeth Trist rented a room from George and Mary Walker Divers at Farmington Plantation, just west of Charlottesville. Mrs. Divers was Peachy Gilmer’s maternal aunt. Mrs. Trist was indirectly related to the Divers through Peachy Gilmer’s marriage to her niece, Mary House. Trist’s date of departure from Monticello is unknown, but he first attended classes at West Point in October 1818. See Wallace Ohrt, Defiant Peacemaker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1997), p. 17.

Nicholas’s stepfather, the wealthy, French-born planter Etienne St. Julien de Tournillon (1770–1857) fled France during the revolution in that country for the family’s sugar plantation in Haiti. He subsequently escaped that island nation’s slave insurrection and finally moved to Louisiana. He married Nicholas’s mother, Mary Brown Trist Jones, and settled on a cotton plantation near Donaldsonville, in Lafourche Parish. The couple often spent time in New Orleans on business. “M. St. Julien de Tournillon Obituary: 1857,” New York Daily Times, February 14, 1857, p. 9.

Etienne St. Julien de Tournillon (Lafourche Parish, Louisiana) to Nicholas Trist (Monticello), January 25, 1818; Etienne St. Julien de Tournillon (New Orleans) to Nicholas Trist (Albemarle), April 10, 1818, NPTP. This correspondence documents the earliest known reference to the Campeachy chair form’s production in New Orleans. While almost certainly earlier or other documentation regarding the form exists, it has yet to be published. Etienne St. Julien de Tournillon (New Orleans) to Nicholas Trist (Albemarle), April 10, 1818, NPTP. The authors are grateful to Kate Swisher for translating this letter.

Mary Trist Jones Tournillon (New Orleans?) to Nicholas Trist (Charlottesville), May 7, 1818, NPTP. Most chairs originating in Latin cultures around the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico had coarse cowhide seats simply nailed to the frame, though some were embellished with naturalistic or geometric designs, the work of a saddle maker who carved the leather or stamped it with metal dies. Highly ornamental, the finished product was nonetheless rigid to the touch.

John F. Dumoulin (New Orleans) to Nicholas Philip Trist (Farmington), July 23, 1818, NPTP. Mail sent from New Orleans to Virginia by sea normally took about a month. Therefore, Dumoulin predicted that Trist would “received the Spanish Arm chairs which your father ordered for you” before receiving the letter. That the crated chairs went from New Orleans directly to Baltimore without stopping in Norfolk implies that the schooner was loaded with goods destined for the Baltimore market.

Martha Jefferson Randolph (Edgehill) to daughter-in-law Jane Hollins Nicholas Randolph (daughter of Wilson Cary Nicholas), undated. Cataloguers ascribe the undated letter between two others bearing dates of May 6 and December 31, 1818, respectively, NPTP. Jane married Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1792–1875), Jefferson’s oldest grandson, in 1815. Rockfish Mountain House was a popular hotel located just over the Blue Ridge Mountains from Rockfish Gap. It had a commanding view of the Shenandoah Valley.

Thomas Jefferson (Warm Springs) to Martha Jefferson Randolph (Edgehill), August 7, 14, and 21, 1818; Thomas Jefferson (Monticello) to Lafayette (La Grange), November 23, 1818; and Thomas Jefferson (Monticello) to Henry Dearborn, July 5, 1819, all in Betts and Bear, eds., Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson, pp. 423–27. See further p. 427 n. 1 for abstracts of the Dearborn and Lafayette letters. See also N. G. Schneebert, “The Medical History of Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826),” Journal of Medical Biography 16, no. 2 (2008): 118–25.

Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, August 24, 1819, CCJM.