Detail of the sculpture of George Washington illustrated in fig. 9. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

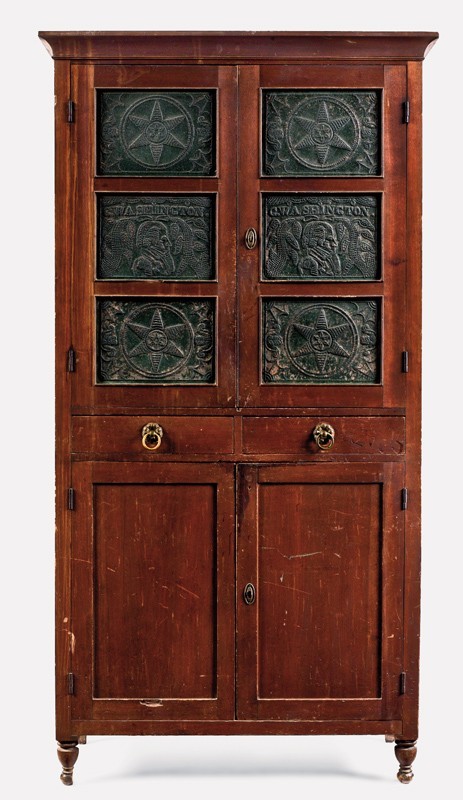

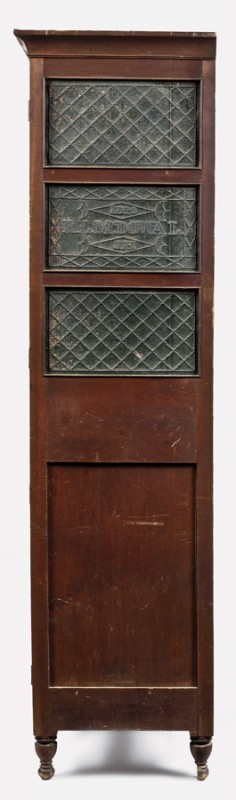

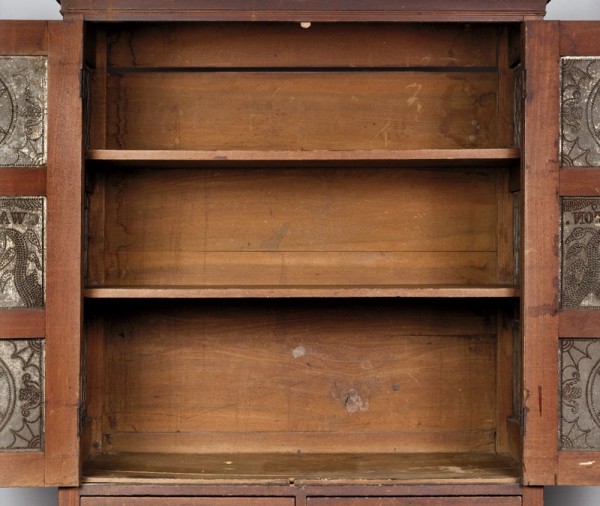

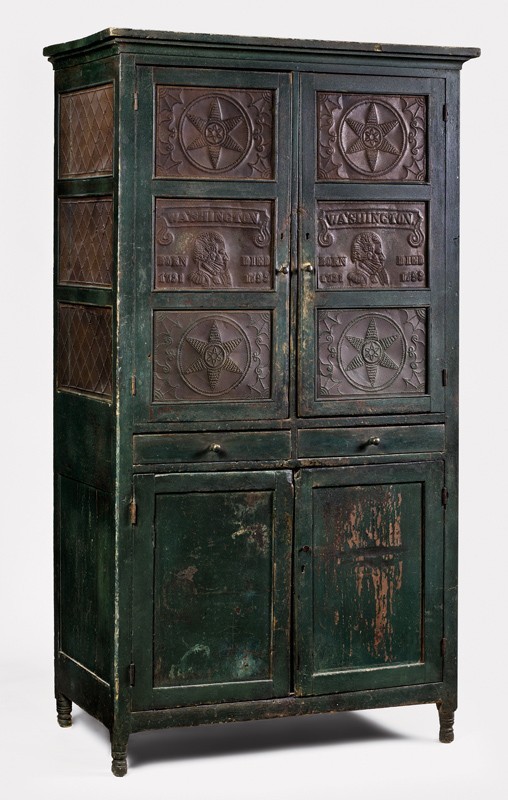

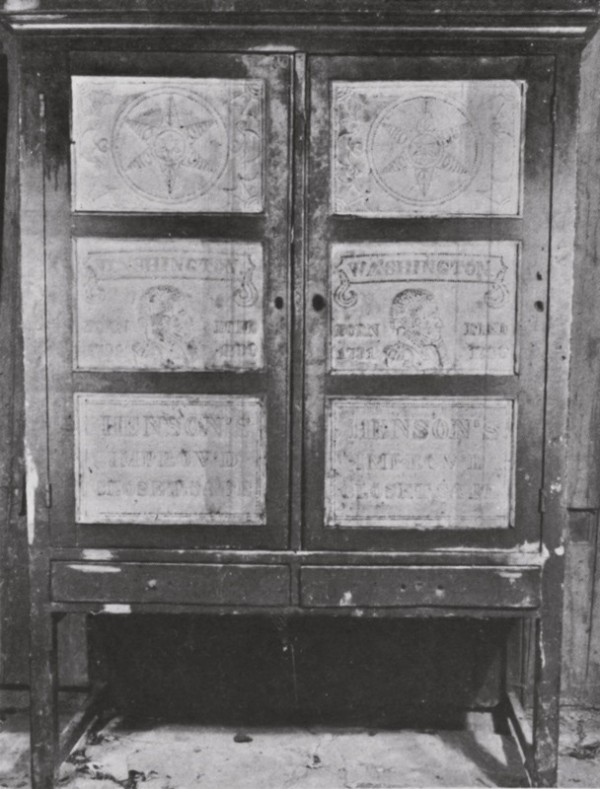

Closet safe attributed to Matthew S. Kahle (1800–1869) and John Henson (act. 1819–after 1831), Lexington, Virginia, 1829. Tulip poplar with white pine; tinned sheet metal. H. 83 1/4", W. 41 1/2", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

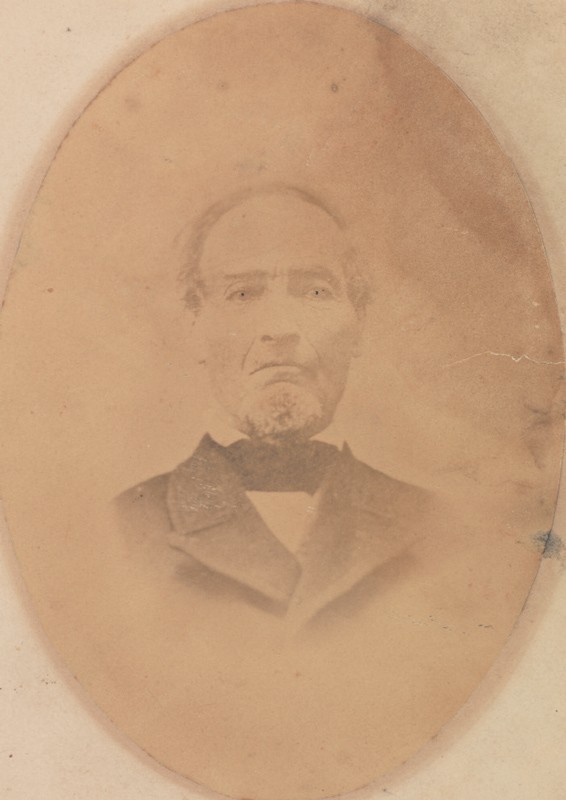

Photograph of Matthew S. Kahle by Michael Miley (1841–1918), Rockbridge County, Virginia, ca. 1868. Albumen print on card. (Courtesy, Virginia Historical Society.) Miley operated his photography studio just north of Kahle’s shop on Main Street in Lexington. Miley is most famous for his photograph of Robert E. Lee on his horse Traveller taken shortly after the end of the Civil War.

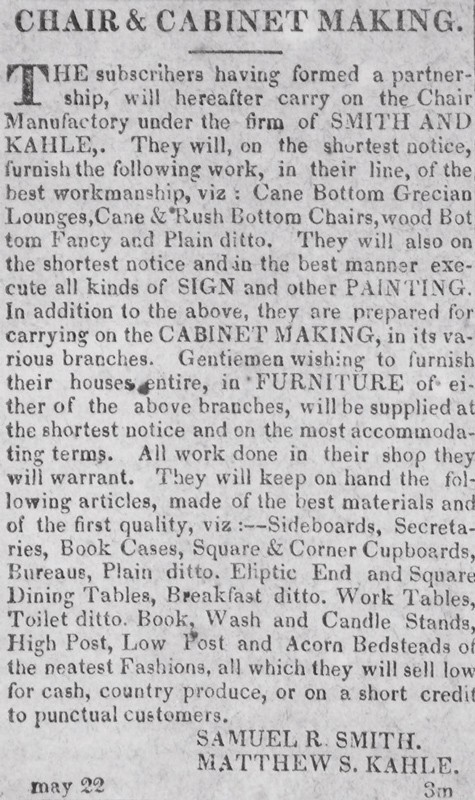

Advertisement of Samuel R. Smith and Matthew S. Kahle, Lexington Intelligencer (Virginia), May 22, 1824. (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.) This same advertisement appeared weekly until August 7, 1824.

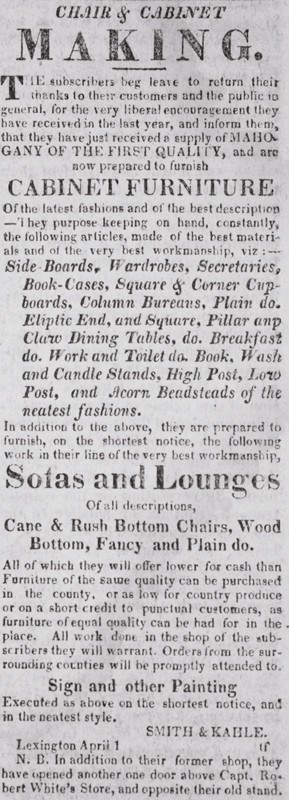

Advertisement of Samuel R. Smith and Matthew S. Kahle, Lexington Intelligencer (Virginia), April 1, 1825. (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.)

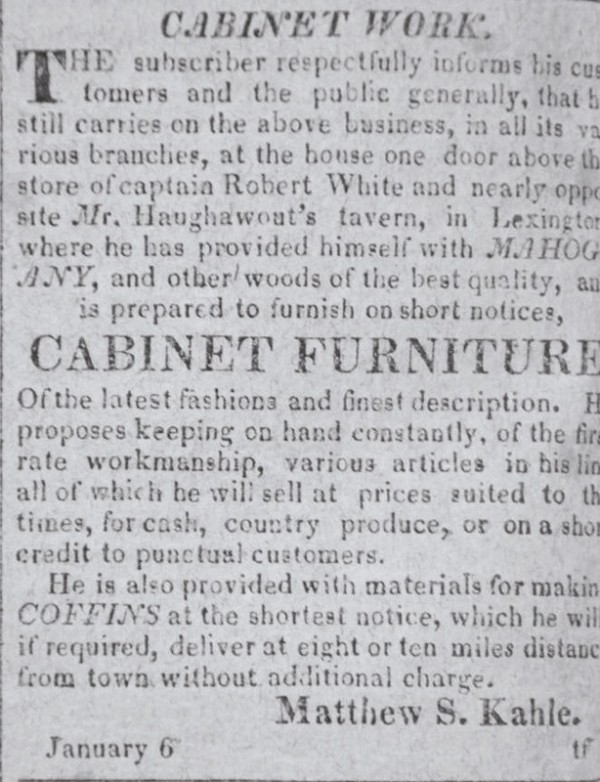

Advertisement of Matthew S. Kahle, Lexington Intelligencer (Virginia), January 6, 1826. (Courtesy, Special Collections, Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.)

Detail of Gray’s New Map of Lexington, Virginia, O. W. Gray & Son, Philadelphia (location where printed), 1877, showing downtown locations associated with the Kahle-Henson group. (1) McDowell/Washington Tavern, (2) Matthew Kahle’s cabinet shop, (3) John Henson’s tinsmith shop, (3a) Michael Miley’s Photography Gallery, (3b) Jacob Fuller’s saddle and harness shop, (3c) Milton Key’s house and cabinet shop (subsequently operated by Andrew Varner), (3d) Thomas Chittum’s cabinet shop, (3e) Jacob Rhodes’s tinsmith shop.

Advertisement of Matthew S. Kahle, Lexington Gazette (Virginia), November 30, 1840. (Courtesy, Special Collections, Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.) This is Kahle’s advertisement for three or four journeymen cabinetmakers.

Matthew S. Kahle, George Washington, Lexington, Virginia, ca. 1844. Tulip poplar. H. 98". (Collection of Washington and Lee University; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Photograph of the statue illustrated in fig. 9 mounted atop Center Hall, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia, ca. 1950. (Courtesy, Special Collections, Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.)

Advertisement of John Graham and John Henson, Lexington Press (Virginia), July 31, 1819. (Courtesy, Special Collections, Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.)

Advertisement of John Henson, Lexington News-Letter (Virginia), September 4, 1819. (Courtesy, Special Collections, Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.)

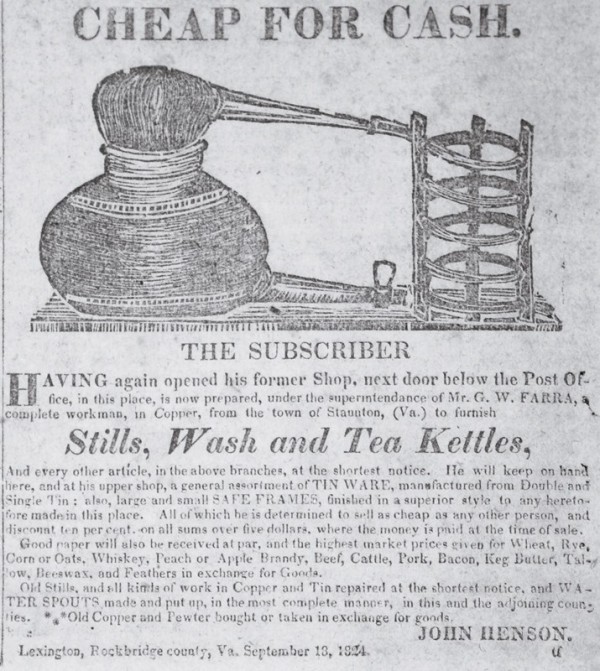

Advertisement of John Henson, Lexington Intelligencer (Virginia), September 18, 1824. (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.) This same advertisement appeared weekly until November 27, 1824.

Detail of a rear foot of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Approximately 1/3 of each foot is a lamination.

Detail of the right side of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

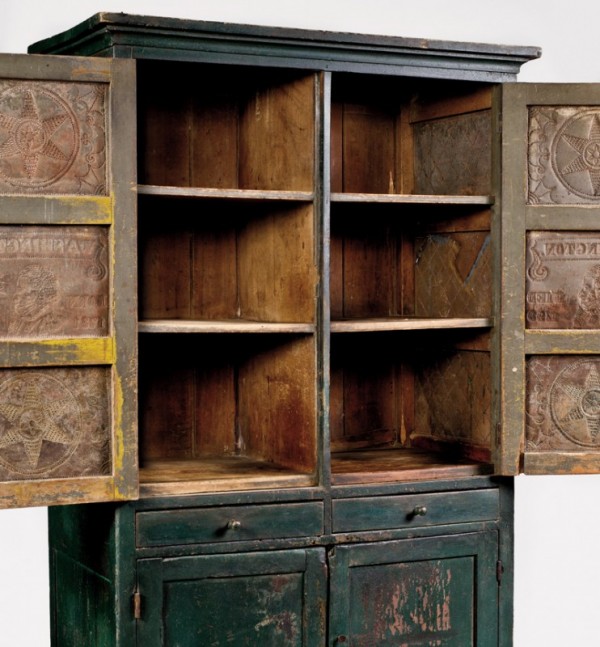

Detail of the interior of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

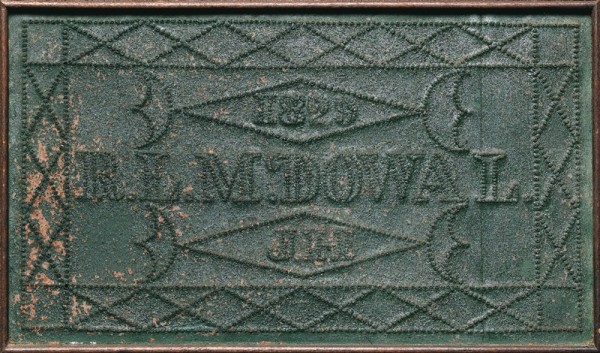

Detail of a tin panel on an upper door of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a tin panel on an upper door of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a tin panel on the right side of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

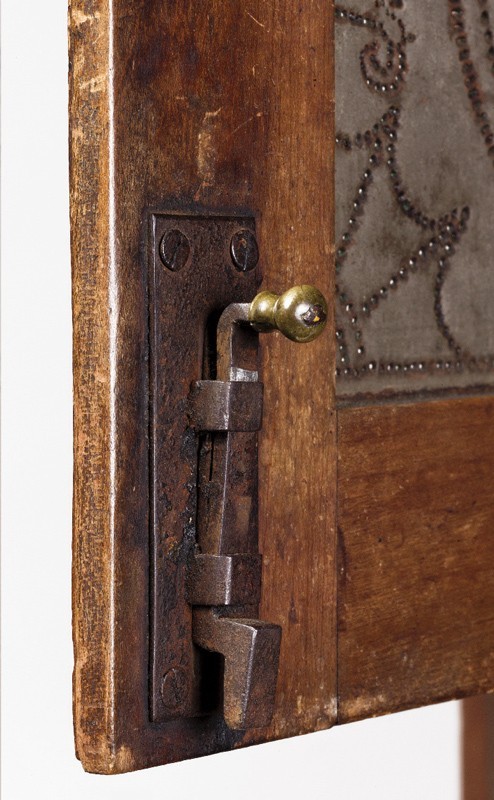

Detail of a latch on the left upper door of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the drawer dovetails of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, William McGuffin.)

Detail of the interior of a tin panel on the upper door of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Closet safe attributed to Matthew S. Kahle and John Henson, Lexington, Virginia, ca. 1831. Tulip poplar; tinned sheet metal. H. 74 1/2", W. 38 5/8", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The drawers are replacements.

Detail of the left side of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a foot of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a tin panel on an upper door of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a tin panel on an upper door of the closet safe illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Closet safe fragment attributed to Matthew S. Kahle and John Henson, Lexington, Virginia, ca. 1831. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Henry J. Kaufman, Early American Ironware [Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966], p. 139, pl. 196.) The overhanging top has an applied ovolo molding in place of a cove molding like that on the safe illustrated in figure 24.

Closet safe fragment attributed to Matthew S. Kahle and John Henson, Lexington, Virginia, ca. 1830. Tulip poplar; tinned sheet metal. H. 44", W. 32 1/4", D. 19". (Sotheby’s, Highly Important Americana from the Stanley Paul Sax Collection, New York, January 16 and 17, 1998, lot 458.)

Photograph of the safe fragment illustrated in fig. 32. (Courtesy, Carole Carpenter Wahler.) This is how the safe appeared when first discovered in a Monterey, Virginia, estate in the early 1970s. The blue paint was original.

Detail of a tin panel on the safe fragment illustrated in figs. 32 and 33. (Courtesy, Carole Carpenter Wahler.)

Punched-tin panel attributed to John Henson, Lexington, Virginia, ca. 1825. Tinned sheet metal. 9 3/4" x 13 5/8". (Courtesy, the Collections of The Henry Ford.)

Detail of the sculpture of George Washington illustrated in fig. 9, juxtaposed with facing image of Washington on the punched-tin panel illustrated in fig. 23, a fitting depiction of the Kahle-Henson school. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Research conducted in conjunction with the recently initiated Virginia Safe Project aims to document and study extant furniture with punched-tin panels throughout the state. The initial phase of this multiyear project involves a survey of the Shenandoah Valley region, which supported numerous craftsmen manufacturing a fascinating variety of ventilated wooden storage cabinets, or safes, in various sizes and forms. The goal of this work is to achieve a better understanding of the nature, timing, range, and evolution of safe production.[1]

Characterized by having applied tin panels decorated with a wide variety of punched or pierced designs—culturally meaningful symbols, geometric motifs, animals, plants, buildings, and people—safes were common to the vast majority of nineteenth-century Shenandoah Valley homes. The manufacture of these objects required the skills of a cabinetmaker and a tinsmith, which were often within the purview of a single craftsman. Most makers probably maintained some stock-in-trade while also receiving commissions from patrons wanting particular combinations of standard options or custom details.

Information on individual makers, woodworking shops, the dissemination of style and technology from masters to their apprentices and journeymen, and the distribution and evolution of safe production can be gleaned from signed and dated examples and from observation of commonalities and differences among safes made in the same area as well as those from the broader Shenandoah Valley region. By documenting the full variety of forms made and used in the valley, one can begin to identify regional schools of production and see how industrialization and improved transportation systems influenced manufacture and consumption.

Barbara Crawford and Royster Lyle’s Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans was the first publication to document the craftsmen of that area as well as their equally diverse products. The authors included photographs of two punched-tin panels, one with a profile and “G. Washington” and the other with the name “R. L. McDowal,” the date 1829, and initials “J. H.” The latter panel was from a safe (not illustrated) that Crawford and Lyle attributed to Matthew Kahle, largely based on information provided by Kurt C. Russ. Using information gleaned primarily from Kahle’s advertisements and other documents, Crawford and Lyle created a historical profile for Kahle but neglected to discuss the attributed safe or mention possible candidates for the maker of its tin panels. Although no signed pieces of furniture are documented from his shop, a walnut dining table with turned legs and a carved mantle are attributed to Kahle. The authors did, however, give thorough consideration to his most recognized work—a larger-than-life-size sculpture of “Old George [Washington]” carved for Washington and Lee University between 1842 and 1844 (fig. 1).[2]

Several of the safes surveyed for this article have punched-tin profiles of Washington, which likely reflects local appreciation for his military and political achievements and his gift of James River Company stock to Washington College (now Washington and Lee University). It is also possible that the use of such tins stemmed from Kahle’s admiration of Washington or from that of John Henson, who made and decorated the tin panels. The careers of these men shed light on the collaborative nature of the trades in the southern backcountry, and their work constitutes the most thoroughly documented and earliest punched-tin paneled furniture from the Shenandoah Valley (fig. 2).

The Kahle Shop, 1824–1869

Matthew Kahle (1800–1869) (fig. 3) was born in Pennsylvania and in the early 1820s moved to Lexington, Virginia, where he formed a partnership with chairmaker Samuel Smith (1788–1869) by 1824. The firm of Smith and Kahle offered a variety of furniture forms including bureaus, tables, stands, bedsteads, cabinets, sofas, and chairs (figs. 4, 5), but the principals parted ways after about a year and a half. Kahle’s new independent operation was surprisingly conducted at the same address as Smith’s shop (which continued into the 1860s), suggesting a multi-artisan manufacturing warehouse, and over the next forty-five years included a number of professional associations, partnerships, and family involvement (fig. 6).[3]

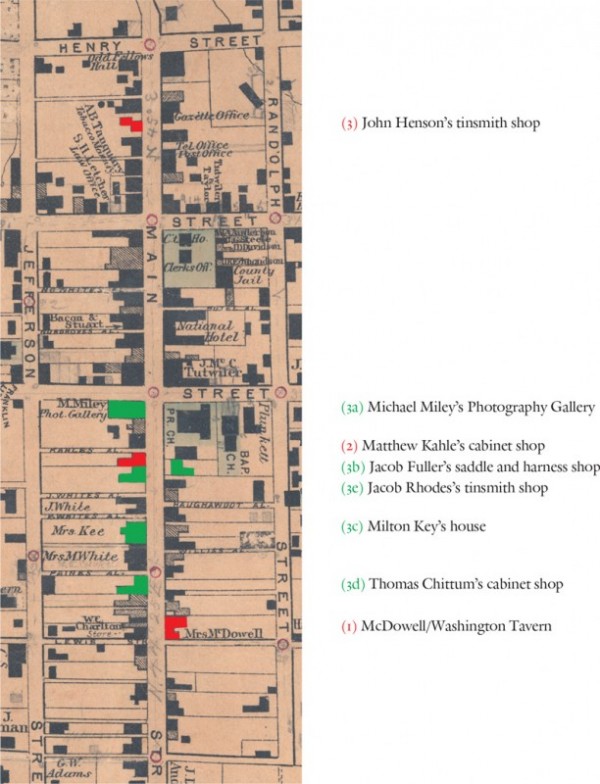

Historical references and nineteenth-century maps confirm the location of Kahle’s shop (fig. 7), which was described in the mid-1820s as being “one door above Captain Robert White’s store” and “nearly opposite Mr. Haughawoat’s Tavern.” By the mid-nineteenth century, the shop was referred to as the “Central Hall Warerooms,” a name used by Matthew and later adopted by his son William, when the latter reopened the family business in early 1857. The Kahle shop was in the heart of downtown Lexington, next door to Michael Miley’s photography gallery to the north, Jacob Fuller’s saddle and harness shop to the south (Matthew’s father-in-law), and across the street from the Presbyterian church, Haughawoat’s Tavern, and Jacob Rhodes’s tin shop. This prime location suggests the importance and success of Kahle’s business within the burgeoning town.[4]

Kahle’s affiliation with tinsmith John Henson is interesting considering the proximity of Rhodes’s shop. Rhodes may have been more of a retailer than a manufacturer, or he may not have been active during the period when Kahle was making the safes with pictorial tins. Rhodes’s October 27, 1842, advertisement in the Valley Star, which described his business as a “Tin, Copper and Sheet Iron Ware Factory” and offered for sale house covering, gutters, and stoves with “old copper, pewter and produce taken in exchange,” supports the latter scenario.[5]

Advertisements for Kahle’s shop mention wardrobes, square cupboards, and “cabinet furniture” but do not refer to any form clearly identifiable as a safe. In contrast, Henson’s reference to large and small safe frames in 1824 indicates that local cabinetmakers were making furniture with punched-tin panels by that date. Although descriptive references to safes are rare, it is likely that “safe frame” was an accepted term in Rockbridge County and possibly other areas of the Shenandoah Valley as well.[6]

Kahle’s business appears to have grown between 1838 and 1840. During that short period, his advertisements mentioned trips to Richmond and the North and noted his purchase of large quantities of mahogany. Kahle also made and shipped coffins, offered “Sofas, Sideboards, Desks, Bureaus, Wash-Stands, Bedsteads &c.” for sale, and advertised services, including “Sign and Ornamental PAINTING.” Promising “constant employment and good wages,” he sought “one or two Journeyman” in 1838 and 1839 and later offered to immediately employ “3 or 4 Journeymen Cabinet Makers” (fig. 8).[7]

Matthew Kahle’s most renowned and important work is a sculpture of George Washington (fig. 9) commissioned by the board of trustees of Washington College in 1842. The statue stands slightly more than eight feet in height and was carved from tulip poplar and painted white to resemble marble. Suggested inspirations for Kahle’s sculpture are Jean-Antoine Houdon’s marble statue of Washington at the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond and William Rush’s painted wood version first exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Kahle’s statue was completed in 1844 and installed atop Center Hall on the Washington College campus on May 20 of that year (fig. 10). Five days later, the Lexington Gazette described his sculpture as a “well executed work of art” and referred to Kahle as a “kind of ‘universal genius.’” “Old George” stood as a local icon high above the campus for nearly 150 years, until it was removed for conservation in 1990 and then retired to the Washington and Lee University library.[8]

Like many backcountry cabinetmakers, Kahle did architectural work and made a variety of wooden objects other than furniture. Between 1833 and 1842 he constructed a speaker’s platform and made a blackboard for Washington College. He also provided drumsticks, gun racks, and tent floors to the Virginia Military Institute and built the platform used for commencement proceedings at the Presbyterian Church, which served both colleges.[9]

In 1825 Matthew married Sarah A. Fuller (1809–1879), whose father, Jacob, had a saddle and harness maker’s shop adjacent to Kahle’s business. By 1850 Kahle’s household included ten children ranging in age from three to twenty. At that date, two of his sons were training in his shop: Samuel F. (b. 1832), who was eighteen, and William H. (1837–1863), fourteen. Two other men residing in Matthew’s household were probably workmen. James McCoy (McIevy), who was listed as being seventeen in 1850, was probably an apprentice, whereas George Adams, who was listed as twenty-five, was likely a journeyman.[10]

Once Kahle referred to his business location as “the Central Hall Warerooms,” his advertisements began listing a wider range of furniture forms, including “Center, Pier, Dining and Breakfast Tables, Plain and Portable Wardrobes,” sideboards, bureaus, and tête-à-têtes. In August 1855 he boasted that his “large and very superior inventory” featured “Mahogany, Maple, Rosewood, and Walnut, Bureaus of the best finish, Sideboards, Sofas, Ottomans, Tables, Wardrobes, Lounges, [and] Bedsteads,” but five months later Kahle offered his stock at cost and reported that any remaining furniture would be “disposed of at Public Auction on the 22nd of December.”[11]

Although Samuel and William Kahle advertised their purchase of Matthew’s stock and fixtures in January 1856, the sons’ partnership “dissolved by mutual consent” nine months later. Samuel’s subsequent career in the cabinet trade was brief. In September 1856 he advertised his desire to purchase two thousand feet of “good and well-seasoned Walnut,” but he closed his business in early December. William had greater success. He reopened the business as Central Hall Warerooms in February 1857 and the following year requested that his father’s former customers and workmen settle their debts and return borrowed tools. William’s advertisements in 1858 and 1859 listed coffins and a variety of furniture forms for sale. Maintaining stock-in-trade and responding to commissions required him to keep sufficient material on hand, as indicated by his purchase of a large of quantity of walnut and tulip poplar from John H. Lyle’s sawmill in April 1858. The following January, William reminded the public that he had taken over his father’s business and was located “At the Sign of the Flag . . . on Main Street, nearly opposite the Presbyterian Church Square.” Nine months later, he announced the sale of “all the furniture I have on hand at the time,” and in November he married Mary E. Breedlove.[12]

On June 7, 1860, the Lexington Gazette reported:

Wm. H. Kahle having returned to his native town with the view of spending the remainder of his life in the legitimate pursuit of his calling, proposes carrying on the Cabinet-making Business at the old stand on a more liberal and enlarged plan, and taking advantage of this recent travel and observation, he is prepared to furnish all kinds of CABINET WORK or CHAIRS from the commonest cottage to the more elaborate finish of modern styles. All orders promptly attended to—COFFINS! COFFINS!—All kinds made, from the most common Poplar to the finest Mahogany—also, keeps on hand CRANE, BREED & Co’s METALIC BURIAL CASKETS which he will carry to any point in the county or State, on the most reasonable terms. All Kinds of Lumber taken in exchange for work—Lumber to be delivered when the work is taken.

Diversified production is indicated by the reference to chairs “from the commonest cottage to the more . . . modern styles,” which did not appear in advertisements during Smith and Kahle’s brief partnership. The sale of metallic caskets signals changes in the traditional craft industry owing to industrialization and mercantilism, and Kahle’s offer to ship caskets to “any point in the . . . State” reflects improved modes of transportation available in the Shenandoah Valley during the mid-nineteenth century. Neither William’s wish to pursue his “calling” nor the challenge of successfully negotiating his cabinetmaking business in the face of these changes was fulfilled. In 1863 he died at Gettysburg while serving as a private in Company H of the Stonewall Brigade.[13]

Samuel and William’s younger brother Jacob P. Kahle (1847–1886) may have taken over the family business by 1870, when the federal census listed the latter as a cabinetmaker, twenty-three years of age, although it is possible that he was simply a workman in another local shop. His younger brother George would have been sixteen in 1870 and was probably serving an apprenticeship in the cabinetmaking trade. The choice of George for the name of Matthew’s youngest son may, like the punched-tin panels on the safes illustrated in figures 2, 24, and 31 reflect the elder Kahle’s affection for George Washington.[14]

The Central Hall Warerooms location continued to function and evolve long after the Kahle family’s involvement diminished during the mid-to-late 1860s. Several competitors opened cabinet shops just a few blocks south on Main Street, including Thomas Chittum (act. 1839–1855), who established his business fifteen years after Matthew Kahle; Milton Key (act. 1856–1860), one of Lexington’s most recognizable cabinetmakers; and Andrew Varner (act. 1860–1889), who worked in Key’s shop and began leasing the same building when his master retired. Varner subsequently formed a partnership with John Pole, who had also worked for Key.[15]

Three of Matthew Kahle’s daughters married local cabinetmakers: Catherine. M. married William P. Hartigan, circa 1865; E. (Ellen or Emma) Blanche married Richard H. Bayliss, circa 1871; and Frances married Thomas Forsyth, circa 1862. Hartigan was listed in the 1860 census with John Boude, a former journeyman of Andrew Varner, between 1857 and 1860. Hartigan and Boude subsequently worked for Milton Key. Bayliss was listed as a cabinetmaker in the 1870 census. Seven years later he occupied the site of “Kahle’s old Warerooms opposite the Presbyterian Church” and offered to “Manufacture to order furniture of rosewood, walnut, mahogany or oak.” The 1880 Census of Manufacturers listed his production value at one thousand dollars. Thomas Forsyth was active as a cabinetmaker from 1862 through 1870. In 1865 he manufactured furniture for Varner’s shop, including a wardrobe, a safe, cottage bedsteads, dining tables, breakfast tables, a washstand, and a walnut bureau. This reference to the manufacture of a safe is significant since it demonstrates that the form was still being made more than forty years after Henson advertised “safe frames.” It is also the last reference connecting safe manufacture to anyone with a family connection to the Kahles.[16]

The Henson Shop, 1819–after 1831

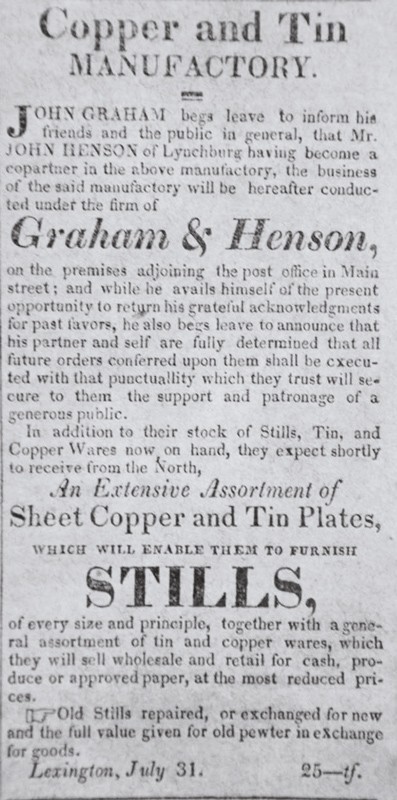

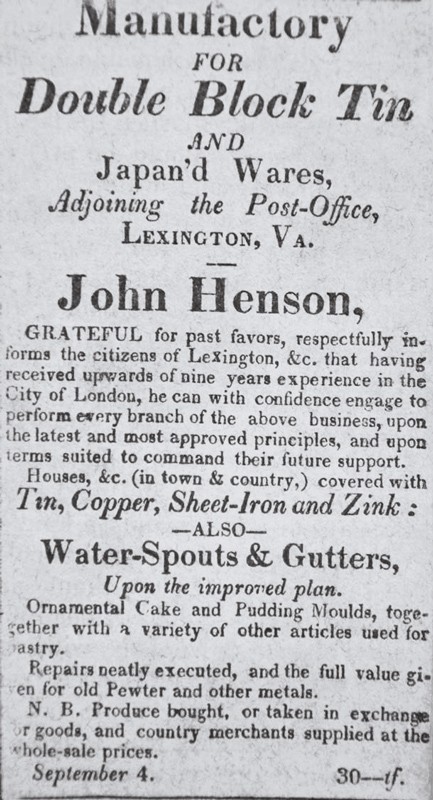

John Henson was born in London and trained as a tinsmith. His decision to immigrate may have been influenced by advertisements soliciting tinsmiths and other tradesmen to go to America, where demand was significant and competition was less than in British towns and cities. Henson arrived in Lynchburg in 1819 with “upwards of nine years of experience in the City of London,” but he soon moved to Lexington to establish a partnership with metalworker John Graham “on the premises adjoining the post office in Main Street” (fig. 11). Like Kahle, Henson found it prudent to form a partnership with an established business to give him time to assess the market for his services and products. Graham and Henson’s initial stock of stills and tin and copper ware must have been limited, because on July 12, 1819, they informed the public that “an extensive assortment of sheet copper and tin plates” was on order from Richmond, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, enabling them “to furnish STILLS, of every size and principle, together with a general assortment of tin and copper wares.” The firm’s products were offered both wholesale and retail for “cash, produce or approved paper at the most reduced prices,” with “full value given for old pewter in exchange for goods.” A little over a month later, however, Henson apparently bought out Graham’s operation, advertising his own “Manufactory for Double Block Tin and Japan’d Wares,” also adjoining the post office (fig. 12).[17]

John Henson’s manufactory offered many products and services, including “Ornamental Cake and Pudding Moulds, together with a variety of other articles used for pastry”; “Tin, Copper, Sheet-Iron and Zink” roofs; and “WATER-SPOUTS & GUTTERS, Upon the improved plan.” His business appears to have thrived until late in 1823, when he “sustained a great loss” because “some persons are in the practice of selling tin ware of an inferior quality,” falsely represented as being products of Henson’s shop.[18]

Henson quickly recovered from his losses. In September of the following year he advertised:

Having again opened his former shop, next door below the Post Office, in this place, is now prepared, under the superintendance of Mr. G. W. FARRA, a complete workman, in Copper, from the town of Staunton (Va.) to furnish Stills, Wash and Tea Kettles, And every other article, in the above branches, at the shortest notice. He will keep on hand here, and at his upper shop, a general assortment of TIN WARE manufactured from Double and Single Tin; also, large and small SAFE FRAMES, finished in a superior style to any heretofore made in this place. All of which he is determined to sell as cheap as any other person, and discount ten percent on all sums over five dollars, where the money is paid at the time of sale. Good paper will also be received at par, and the highest market prices given for Wheat, Rye, Corn or Oats, Whiskey, Peach or Apple Brandy, Beef, Cattle, Pork, Bacon, Keg Butter, Tallow, Beeswax, and Feathers in exchange for Goods. Old Stills and all kinds of work in Copper and Tin repaired at the shortest notice, and WATER SPOUTS made and put up, in the most complete manner, in this and the adjoining counties. Old Copper and Pewter bought or taken in exchange for goods.

Henson’s reference to safe frames “in a superior style to any heretofore made in this place” (fig. 13) suggests earlier production of that form, although it is unclear if those antecedents had punched-tin panels. Further evidence of his financial success is found in subsequent advertisements for apprentices and journeymen, including a runaway named William Flint, and the establishment of a second retail outlet—a “tin and copper store” opposite Kyle and Campbell’s business. While the latest Henson advertisement is from August 1830, when he offered “stronger and superior” kettles ranging from one to twenty-five gallons, each made from a single piece of brass, his inclusion in the 1830 and absence from the 1840 U.S. federal censuses suggest his operation ceased sometime during this period.[19]

Numerous other tinsmiths, including some of Henson’s former apprentices and journeymen, continued working in Lexington and would have been sources for punched-tin panels used by Matthew Kahle, his sons, and other local furniture makers. Some later but distinctive tin panels from Rockbridge County are known, but none can be definitively linked to Henson’s work or that of craftsmen trained by him. Two safes have related star motifs on their punched-tin panels, but the designs are generic and not as finely executed as those by Henson.

The Kahle-Henson Safes

Family tradition maintains that Robert L. McDowell (McDowal) commissioned the safe illustrated in figure 2 for use in his home and adjacent inn, which were located at the corner of Main and Lewis (now Preston) streets in Lexington (fig. 7). McDowell was born in present-day Rockbridge County on March 17, 1767, and married Margaret Moore (ca. 1750–1830) on August 14, 1792. Their daughter Rebecca (ca. 1799–1857) married William C. Lewis on August 9, 1836. An Elizabeth McDowell, reputedly born “as long ago as 1792,” may have been Rebecca’s elder sister or Robert’s daughter from a previous marriage. In 1908 Robert’s grandson William G. McDowell sold “the old McDowell property,” which included “one of Lexington’s oldest houses,” to Frank Reed. Thought to have been built by William Moore circa 1775, the frame portion was supplemented with a brick addition that fronted on Main Street and provided extra lodging for guests at the tavern. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the residence and inn were known as Washington Tavern.[20]

Family history indicates the safe was removed from the McDowell home and tavern before the building was sold to the Rockbridge Motor Company in 1919 and taken to the Northeast by descendants.# Allan McDowell, William’s son and Robert’s great-grandson, wrote:

This piece of furniture was known as a PIE SAFE in Virginia, from whence it came. . . . This PIE SAFE . . . was made by . . . a Lexington, Va. Cabinetmaker by the name of Matthew Kahle. The safe was made around the eighteen forties. Kahle was known by the fact that he made the statue of G. Washington that stands on the octagonal cupola on top of Center Hall on Washington and Lee University, then known as Washington College. The statue of Washington was modeled after the Tower of the Winds, a Greek temple in Athens. The PIE SAFE, because of the weird way the tin was punched, was known as the G. W. A. Shington safe to us.

McDowell’s decision to commission a safe with tin panels depicting Washington may have been influenced by the latter’s popularity, both nationally and locally, as well as the object’s intended use. The safe would certainly have garnered attention from guests at McDowell’s (Washington) tavern, assuming that it was installed in a public space.[21]

With the exception of its laminated turned feet (fig. 14), the construction of McDowell’s safe is conventional. The case is assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints, capped with a cove-molded cornice, and painted red. The front has two upper doors with tin panels, two drawers with dovetailed frames, and two lower doors with fielded panels; the side frames have tin panels at the top and fielded panels below (fig. 15). The back is composed of two panels with horizontal boards (fig. 16). The interior upper and lower storage compartments are open and have removable, but not adjustable, shelves (fig. 17).

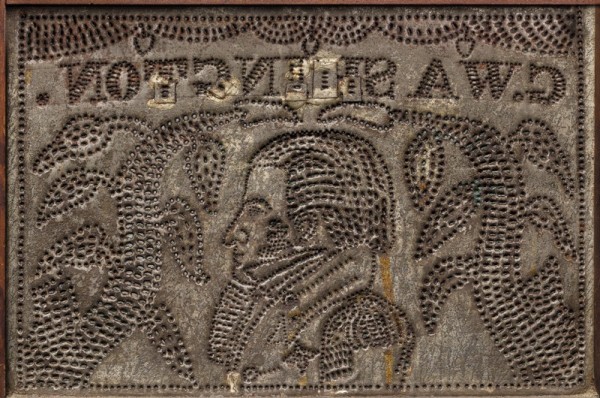

The tin panels retain their original green paint and are secured with small quarter-round moldings. Each of the upper doors has three single-sheet panels. The upper and lower panels are decorated with stars, circles, urns with plants, and lunetted corner fans (fig. 18), whereas the center panels feature a profile of George Washington surrounded by leafy vines and the name “G. W A SHINGTON.” above (fig. 19). The tin panels on the sides are pieced (formed by crimping and soldering a full panel to a partial cut panel) and are slightly larger than the front panels (see fig. 15). The upper and lower panels are diapered, and the center panel bears the name “R.L.McCDOWAL.” between two elongated horizontal diamonds with half-moon terminals, the date “1829,” and initials “J. H.” (fig. 20).

The doors of the McDowell safe have their original iron and brass interior latches (fig. 21) and iron butt hinges, but the brass rosette-and-ring drawer pulls are period examples added later. It is difficult to determine if the latches were made locally or imported and sold by a hardware retailer. The drawer frames are constructed of 3/8" stock (fig. 22), the bottoms have chamfered edges that engage dadoes in the front and sides, and glue blocks are attached along the chamfers to provide additional wood to compensate for shrinkage and wear.

The McDowell safe is the most sophisticated example from the Kahle and Henson shops. The tin panels have both slit and circular piercings, which is unusual in furniture with punched-tin decoration. This is most apparent in the lettering above Washington’s profile (fig. 23), where a few tightly clustered piercings caused breakouts in the letters and required Henson, or one of his workmen, to neatly cut and solder patches before attaching the panels.

The construction and punched tin panels of the safe illustrated in figures 24–30 identify it as another example from the Kahle and Henson shops. This piece was finished with a red paint or wash similar to that on the McDowell safe but had mustard-colored trim and was later painted blue. This safe differs from the McDowell example in having an overhanging board cornice with a small, applied cove molding; full-height, nailed vertical backboards; small feet turned entirely from the stiles; and a vertically divided interior with fixed shelves (figs. 26-28). Some of these features may have been cost-saving options offered by the Kahle shop.[22]

The punched-tin panels of the safe illustrated in figure 24 are secured with quarter-round moldings like those on the McDowell safe. The composition and arrangement of the upper and lower tin panels on both safes are similar (figs. 18 and 29), and the profiles of Washington on their middle panels are virtually identical. On the safe illustrated in figure 24, the profiles have “BORN/1731” to the left, “DIED/1799” to the right, and “WA’SHINGTON.” on the banner above (fig. 30). All of the side panels on that safe have diapered decoration (fig. 25).[23]

A safe fragment published in Henry J. Kaufman’s Early American Ironware is another example from the Kahle and Henson shops with punched-tin panels depicting George Washington (fig. 31). The form and construction are most closely aligned with the safe illustrated in figure 24, although the loss of the lower section makes such comparisons tentative. The star-decorated tin panels on both safes differ only in the treatment of their urns, and the Washington panels are visually identical. On the bottom panels, the phrase “HENSON’S—IMPROV’D—CLOSET.SAFE” provides further insights into period terminology for that form. John Henson’s 1824 advertisement referred to safes by size, not by function. Moreover, his use of the word “Improv’d” suggests evolution in design, technology, and/or functionality. The use of Henson’s name rather than Kahle’s suggests that the former was responsible for the “improvement”—presumably the addition of punched-tin panels—and that the addition distinguished the new “closet safe” form from examples with inferior ventilation or less durable components, such as linen panels.[24]

The safe fragment illustrated in figures 32 and 33 provides additional information on furniture from the Kahle and Henson shops. The piece sold at an estate auction in Monterey, Virginia, in the early 1970s and was subsequently restored incorrectly. The design and construction of the surviving components are consistent with Kahle’s work, but it is likely that this safe originally had tall square legs and possibly lower doors. The surviving door differs from those on the safes illustrated in figures 2, 24, and 31 in having four vertical punched-tin panels. The panels are secured with moldings, albeit slightly more elaborate than usual, and decorated with stars, a large federal eagle perched on a shield, a banner emblazoned “AMERICA,” and a female figure with a floral spray in her right hand and presumably a cap of Liberty or laurel wreath in her left hand (fig. 34). The side panels are diapered like those on other safes in this group.

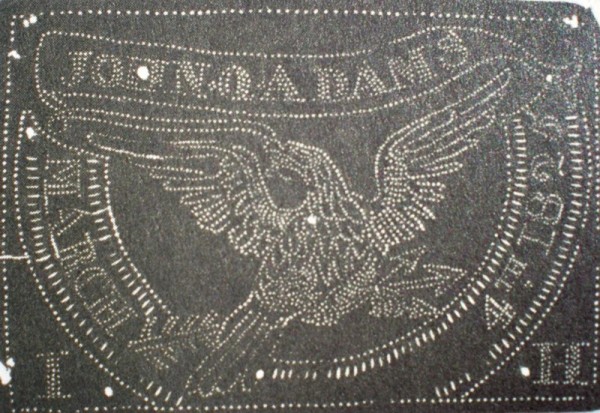

Henson’s and his patrons’ fondness for tins with patriotic motifs and profiles of famous statesmen is also reflected in a single panel commemorating the inauguration of John Q. Adams in 1825 (fig. 35). The panel is punched with an “I” in the lower left corner and an “H” in the lower right corner for John Henson. The use of a Roman uppercase “I” in place of a “J” was common practice as late as the 1840s. Henson’s shop appears to have used templates for several motifs, as suggested by the eagle on this panel, which is virtually identical to that on the safe fragment illustrated in figure 33. Another attribute linking Henson’s punched tins is his consistent style and manner of their lettering.[25]

As the objects discussed in this article reveal, the production of safes in the Shenandoah Valley is not, as traditionally thought, a midcentury phenomenon. Ventilated storage cupboards, or “closet safes,” were being manufactured in the lower Shenandoah Valley during the early 1820s. The Kahle and Henson shops collaborated in the production of these safes, but it appears that many later cabinetmakers fabricated their own tin panels. Now that a group of safes from the earliest period has been documented, the groundwork is established for exploring continuities and changes in production of that form. On a basic level, this study also helps define the safe form by suggesting how those objects were used and how makers and consumers perceived them. Further research may link these safes to specific cultural predispositions in the Shenandoah Valley. For example, might the emphasis on patriotic motifs and revered statesmen in the Kahle and Henson safes reflect sentiments within local Scots-Irish communities, where matters of politics, law, order, and justice were debated vigorously? This was certainly true of furniture made by northern Shenandoah Valley cabinetmaker John Shearer, whose work is distinguished by having politically charged inscriptions and inlays. Questions of this type are what the Virginia Safe Project seeks to answer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the authors thank Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, David Coffey, Ed Dooley, Beverley A. Evans, Erik Gronning, Henry Ford Museum, Rob Hunter, Tabitha Lavis, Lisa S. McCown, Will McGuffin, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, John and Lil Palmer, Linda A. Russ, University of Virginia Library, Virginia Historical Society, Carole Carpenter Wahler, and Washington and Lee University’s Leyburn Library.

Kurt C. Russ and Jeffrey S. Evans, “The Virginia Safe Project: A Prospectus,” 2010. This document describes the project and was submitted for review and comment to curators at selected museums. An exhibit and accompanying publication are being planned for 2014.

Kurt C. Russ was a consultant to the project that culminated in Barbara Crawford and Royster Lyle Jr., Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995). Russ suggested that Matthew Kahle of Lexington, Virginia, made the safe illustrated in figure 2 and a related example in the collection of Carole Carpenter Wahler of Knoxville, Tennessee, which was painted blue and featured two tins with a profile of Washington and his birth and death dates. Russ also initiated discussions with Lyle regarding the identity of the tinsmith who collaborated with Kahle and contributed significantly to creating a profile of that artisan, John Henson. Henson was not mentioned in Crawford and Lyle’s book. Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, pp. 28, 207–8. The walnut table is in the collection of the Rockbridge Historical Society, and the mantle with simple carvings of a hand and a vase of flowers is in the Hopkins House in Lexington, Virginia. Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, pp. 50–52.

Kahle’s father, Peter, moved to Lexington from Berks County, Pennsylvania, a year after Matthew’s arrival and appears to have been involved in his son’s business (Christina Seltzer [Saltzer] obituary, Lexington Gazette [Virginia], November 5, 1846; Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, pp. 207–8). When Peter died in 1846, “Carpenter’s and Cabinetmaker’s tools” were listed in the advertisement for his house and property (Lexington Gazette, August 6 and November 5, 1846).

Kahle’s shop is #112 on the map (Anon., adapted from Champe’s 1912 Map and U.S.G.S. Map and based on notes by Kenneth McDonald and Hunter McDonald [1932] in Cornelia McDonald, A Diary with Reminiscences of the War and Refugee Life in the Shenandoah Valley, 1860–1865 [Nashville, Tenn.: Cullom & Ghertner Co., 1934], insert).

Valley Star (Lexington, Virginia), October 27, 1842. By 1870 F. P. Rhodes is listed as a tin and copper manufacturer, and on September 3, 1891, the property was deeded to Frank P. Rhodes (1870 Industry Schedules for Rockbridge County, Virginia, Virginia Historical Inventory, Rockbridge County, Lexington).

Lexington Intelligencer (Virginia), September 18, 1824.

Lexington Gazette (Virginia), May 18, 1838; May 4 and May 18, 1839; May 9–July 28, 1840.

Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, p. 52.

Board of Trustees Papers, folders 90 (1833) and 109 (1841), Washington and Lee University (hereafter WL), Lexington, Va. Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, pp. 207–8.

Sarah’s sister Margaret married Samuel Smith. Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, p. 207. See Dorthie Kirkpatrick and Edwin Kirkpatrick, Rockbridge County Births, 2 vols. (San Bernardino, Calif.: Bonjo Press, 1988), 1: 329.

Lexington Gazette (Virginia), October 6, 1853; February 23, 1854; August 9 and December 13, 1855.

Lexington Gazette (Virginia), January 3 and September 8, 1856. Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, p. 208. Lexington Gazette, September 18 and December 4, 1856; February 19, 1857; March 4, 1858. Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, p. 208; Valley Star (Lexington, Virginia), January 14 through December 9, 1858; January 13 and 27, 1859. W. T. Williams Papers, April 1858, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond. Lexington Gazette, January 13, October 27, and November 17, 1859. Louise M. Perkins, Rockbridge County Marriages, 1851–1885 (Signal Mountain, Tenn.: Mountain Press, 1989), p. 209; Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, p. 208.

1860 Census (#104) as transcribed by Edwin L. Dooley Jr.; see www.vmi.edu/uploadedFiles/Archives/Local_History/1860Census.pdf; Edwin L. Dooley Jr., “Lexington in the 1860 Census,” Rockbridge Historical Society Proceedings 9 (1975–79): 189–96; Oren Morton, A History of Rockbridge County, Virginia (Staunton, Va.: McClure Co., 1920), pp. 433–34; and Lowell Reidenbaugh, 27th Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg, Va.: H. E. Howard, 1993), p. 154.

Edwin L. Dooley Jr., “The 1870 Census, Lexington, Virginia: Transcribed, Corrected, and Annotated” (#278, Jacob; #280, George), www.vmi.edu/uploadedFiles/Archives/Local_History/1870Census.pdf.

Ed Dooley to Kurt Russ, May 2, 2012; Edwin L. Dooley Jr., “Lexington Ledgers: A Source for Social History,” Rockbridge Historical Society Proceedings 10 (1980–89): 236–44; Edwin L. Dooley Jr., see www.vmi.edu/uploadedFiles/Archives/Local_History/1860Census.pdf; Dooley, “Lexington in the 1860 Census.”

Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, p. 202. 1870 and 1880 Census; Lexington Gazette (Virginia), January 5, 1877; 1880 Federal Manufacturer’s Schedule (Census of Manufacturers), Rockbridge County, Virginia; Crawford and Lyle, Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans, pp. 188, 201.

Lexington News-Letter (Virginia), September 4, 1819; Lexington Press (Virginia), July 12, 1819. Graham and Henson also advertised in the Richmond Enquirer, July 16, 1819. Determining the precise location of the post office and, by extension, Henson’s shop, is difficult. There is no record of a post office in Lexington before 1825. Benjamin Franklin’s earlier effort to build a postal system resulted in the appointment of postmasters responsible for collection and disbursement of sporadic mail collected in a mailbag or pouch, usually at an appointee’s residence or a community business. Many of those appointed as postmasters during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries relegated their duties to others. William Alexander (1793), Samuel L. Campbell (1797), and James R. Wilson (1805) were early Lexington postmasters, likely working out of the lower level of the Alexander-Withrow House at the corner of Main and Washington streets (“Anniversary of the ‘Great Fire’ in Lexington,” April 11, 1907, clipping, Withrow Scrapbook [hereafter WS], vol. 11, p. 104, Special Collections [hereafter SC], Leyburn Library [hereafter LL], WL). “Lexington Postmasters: 1793–1928,” compiled by Royster Lyle Jr., March 20, 1972, from the “Records of Appointments of Postmasters,” National Archives, Washington, D.C., Miscellaneous Papers of the Rockbridge Historical Society, SC, LL). In 1825 John Quincy Adams’s administration appointed Lexington merchant William Wilson as postmaster, a position the latter had assumed unofficially in 1807. In 1825 the Lexington post office was located on north Main Street. The second postmaster, who took over from Wilson in 1829, Samuel Dold, moved the office to his business at the northeastern corner of Main and Washington streets opposite the Alexander Withrow House. James K. Polk appointed Dr. Archibald Graham as Dold’s successor in 1845, but Graham relegated his duties to his brother-in-law John B. Lyle. During Graham’s tenure, Lyle’s bookstore, opposite the county courthouse on Main Street, served as the post office. This may have been the former location of Henson’s “Tin and Copper Store.” Mr. J. M. Adair reputedly purchased the site of the post office and demolished the building to build a new residence (“Local P. O. Has Seen Many Changes,” Rockbridge County News [Virginia], March 5, 1942, WS, vol. 2, p. 76, SC, LL). Assisting with identifying the location of Adair’s residence, and hence the post office and Henson’s shop, is another historical reference that states, “Adair’s residence was located next to Walker’s Meat Market” (“Post Offices and Postmasters in Early Days of the Town of Lexington,” clipping, WS, vol. 1, p. 108, SC, LL). Fortunately, period maps and photographs show the location of the Adair building and a later business established by his descendants. These documents also identify “Wilson’s Meat Market” in the southern part of the Wilson-Walker House located on north Main Street. Henson’s reference to his shop being “next door below” to the post office remains ambiguous because it does not specify whether the shop was to the north or south. Acknowledging a degree of uncertainty owing to changes in Lexington buildings over the years, Gray’s 1877 map location for Henson’s shop is plausible. It is also likely that one of the two buildings shown on the lot was the site of Lexington’s first official post office (see fig. 7).

Lexington News-Letter (Virginia), September 4, 1819. Henson also advertised that he “COVERS HOUSES &c. with TIN or COPPER” in Fincastle, Virginia (Herald of the Valley [Fincastle, Virginia], September 4, 1820). Lexington Intelligencer (Virginia), December 27, 1823.

Lexington Intelligencer (Virginia), December 27, 1823; September 18, 1824. Stills were listed in the earliest Graham and Henson advertisements but not in advertisements placed by Henson after the partnership dissolved. Farra may have been responsible for the production of stills as well as other forms not listed by Henson while working as an independent craftsman. Lexington Intelligencer, June 3 and October 21, 1825; August 7, 1830.

The spelling of “McDowell” does not appear to become consistent until 1830. The 1820 federal census of Rockbridge County recorded the name as “McDowel.” The “McDowal” spelling on this safe is the original Scottish version of that name. James McClung, Survey Report of Formerly Old McDowell Inn, now Rockbridge Motor Company, Inc., July 22, 1936, Virginia Historical Inventory, Works Progress Administration Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond; http://image.lva.virginia.gov/VHI/html/24/0025.html. Robert is buried in the Stonewall Jackson Cemetery; the tombstone marking his grave confirms his birth date and death on August 18, 18__ (the exact year unclear). Since the marriage register of his daughter shows him as the father, it is likely he was alive at least until 1836. (“Thoughts as an Old House Changes Hands,” 1908, clipping, WS, vol. 1, p. 104, SC, LL). Guests included Andrew Jackson, who was frequently at the tavern on his trips from Tennessee to Washington, D.C., and Tennessee senator Hugh L. White.

“Another Landmark Being Removed,” February 20, 1946, clipping, WS, vol. 13, p. 111, SC, LL. Note (undated) accompanying safe signed by Allan McDowell, in possession of Kurt Russ.

Kurt Russ first examined this safe fragment in the early 1980s, when it was in the collection of Tennessee decorative arts dealer and scholar Carole Carpenter Wahler. She stated that picker Clark Garrett reported finding the safe in the region where southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee meet. Wahler had previously owned the safe illustrated in figure 33 and realized that it and the example shown in figure 24 were by the same maker. She also postulated that the tin panels on those objects and a tin in the collection of the Henry Ford Museum (fig. 35) were related. The authors are grateful to Wahler for laying groundwork for their research.

This use of 1731 as the birth date of George Washington is in reference to the old-style Julian calendar in use when Washington was born. Henson’s employment of this date seems to indicate that the safe was produced in 1831, which would have been the one-hundredth anniversary of Washington’s birth on February 11, 1731. Kurt Russ saw another safe of the same basic form as the McDowell example and the safe illustrated in figure 24 at an estate auction in Lexington, Virginia, in the late 1980s. The former object had tin panels with “JUSTICE” in a banner supported by spiked poles with climbing snakes.

Typically estate inventories and shop ledgers simply list “safe” or “food safe.” “Pie safe” is an early twentieth-century term now universally applied to all furniture with punched-tin panels. It is unlikely that the “improvement” referred to decoration. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term “closet,” which can be traced to the late sixteenth century, denoted “a private repository of valuables; or cabinet.” By the early seventeenth century “closet” also referred to “a small side-room or recess for storing utensils, provisions, etc.; a cupboard.” During the mid-fifteenth century, the word “save” was “assimilated to safe” and used to describe a receptacle such as “a ventilated chest or cupboard for protecting provisions from insects and other noxious animals.” The inclusion of a period in Henson’s term “Closet.Safe” might denote dual use, with the upper section constituting a ventilated safe and the lower section a closet (cupboard).

This pierced-tin panel was published in Alice Winchester, The Antiques Treasury of Furniture and Other Decorative Arts (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1959), p. 191, fig. 16. See Catherine B. Hollan, Virginia Silversmiths, Jewelers, Clock- and Watchmakers, 1607–1860, Their Lives and Marks (McLean, Va.: Hollan Press, 2010), pp. 8–10, for a discussion of Alexandria silversmith John Adam’s use of “I.ADAM” from circa 1810 through the 1840s.