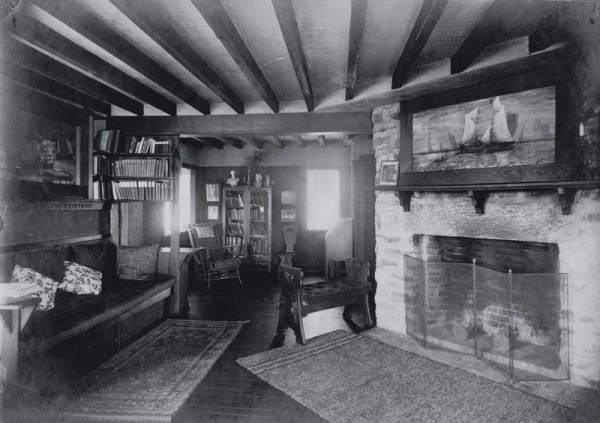

Photograph of the living room of Tower House, Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1915. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) Tower House was first used as William Lightfoot Price’s studio and was later converted by his son William Webb. It still stands on Price’s Lane in Rose Valley just a few feet from the elder Price’s own house.

Detail of the Rose Valley brand on the chair illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Rose Valley was a community of like-minded people but not necessarily a community of craftsmen. Price had intended to franchise the Rose Valley brand to artisans who would come to the community and set up studios and workshops for the production of various crafts like pottery, metalwork, or woodworking. While there was much craft making among the residents, potter William P. Jervis was the only individual authorized to impress the mark on his ceramics. Some surviving furniture made in the Rose Valley Shops bears the brand and some does not; it is not yet known if there was a system of marking that determined which pieces should be branded.

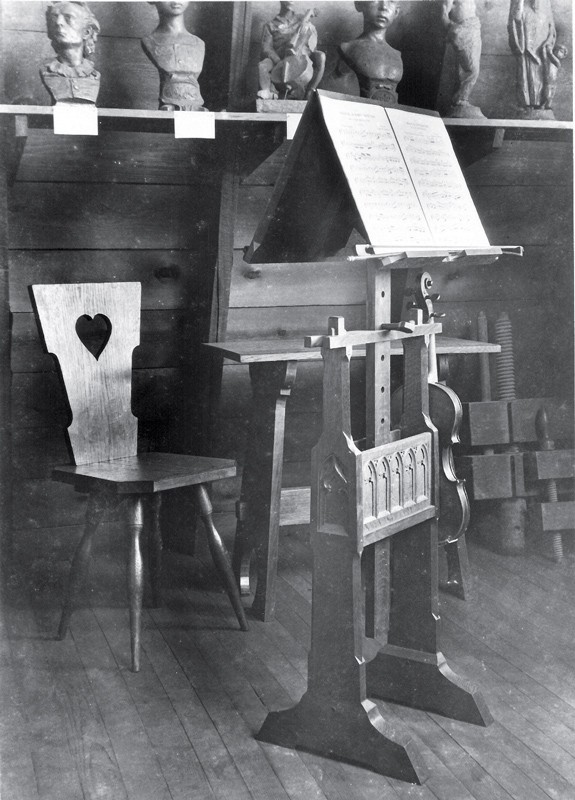

Music stand designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1905. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) Price designed several music stands, which were produced at Rose Valley and Arden. A variant of this stand was included in a circa 1909 drawing by Rose Valley denizen Alice Barber Stephens and illustrated in Robert Judson Clark, The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1876–1916 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972), no. 23.

Music stand designed by William Lightfoot Price and made by Don Stephens, Arden, New Castle County, Delaware, ca. 1905. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Arden Craft Shop Museum and Arden Archives, property of Arden Archives.)

Photograph of a room in Yorklynne, York County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. (Courtesy, Lower Merion Historical Society.) Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman furniture factory produced the box settle used in this house, which was designed for John O. Gilmore in 1899. An identical settle is still in use at Glenmede, the house Price designed for George S. Graham in Bryn Mawr, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, in 1904.

Newel post finial carved by John (Johannnes) Kirchmayer for All Saints Parish Church, Brookline, Massachusetts, 1899–1926. Oak. (Courtesy, All Saints Church; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Ralph Adams Cram and Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue designed this detail for All Saints Church in 1899. Kirchmayer’s rigid execution is a result of his effort to adhere to the architects’ specifications rather than a nod to Gothic style.

Detail of a walrus carved by Karl von Rydingsvärd for a desk made for Arthur Curtiss James’s yacht Aloha (built in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1910 and scrapped in 1938). (Collection, Mystic Seaport.) Although von Rydingsvärd sometimes used the traditional Gothic style for carved furniture and woodwork, he favored the voluptuous soft edges and convolutions of the Norse style, inspired by work from his homeland.

Detail of a dolphin arm support on the chair illustrated in fig. 31. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Edward Maene carved furniture for his own use or for commissions like the woodwork for the George Washington Memorial Chapel at Valley Forge that was not influenced by Price’s designs. Maene’s carving style is less fluid than that seen on Rose Valley furniture designed by Price.

Detail of the arm support of a chair designed by William Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, or Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This armchair was made for John O. Gilmore’s house, Yorklynne. The plastic character of carving from the Rose Valley shop may have come from the use of maquettes, often sculpted in clay at Maene’s Philadelphia shop and then copied in wood at Rose Valley.

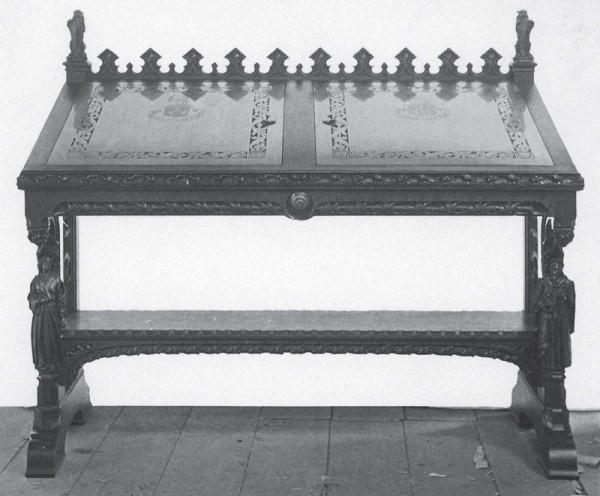

Cabinet designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) In 1903 Horace Trumbauer commissioned a cabinet to display and protect Shakespeare folios owned by William Harrison. The cabinet was completed but never delivered to Harrison. Its whereabouts are not known, but it is hard to believe that such an elaborate and substantial masterpiece is not still extant.

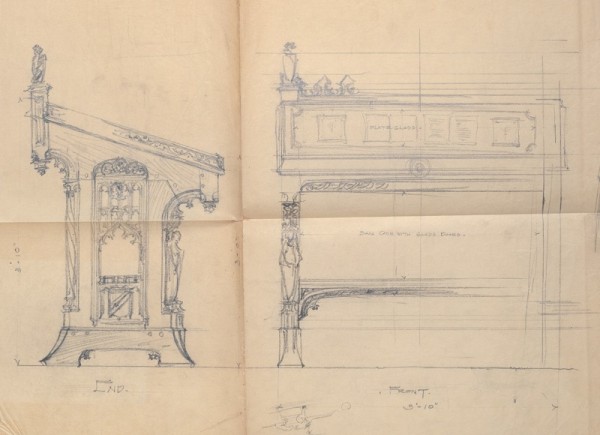

Preliminary drawings for the cabinet illustrated in fig. 10. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) Price made many detailed drawings for the Shakespeare cabinet, which included every carved detail as well as exact specifications for the casting and engraving of the brass panels that were set into the doors on the top of the cabinet.

Photograph showing the Shakespeare cabinet in Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

Clay maquette for the Shylock figure on the Shakespeare cabinet in Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

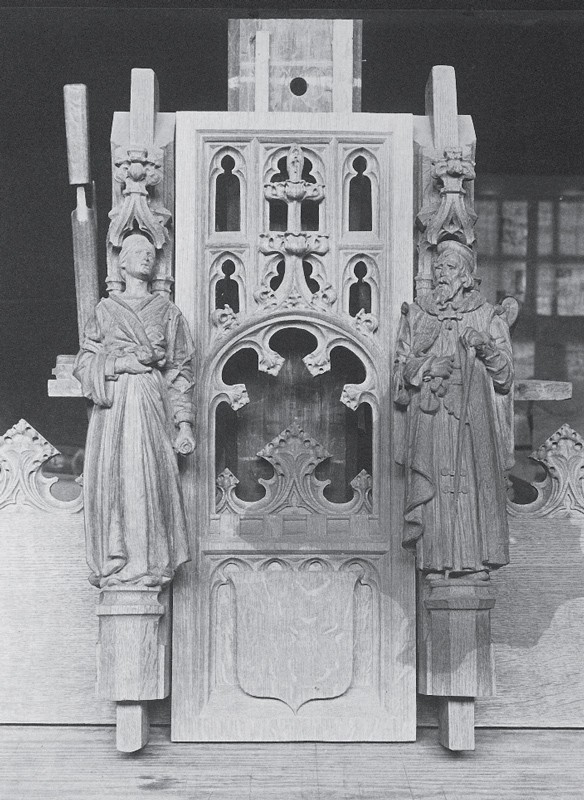

Photograph showing finished components of the Shakespeare cabinet in Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) No other Rose Valley piece had such a complete photographic record, which is indicative of how much importance Price accorded this commission.

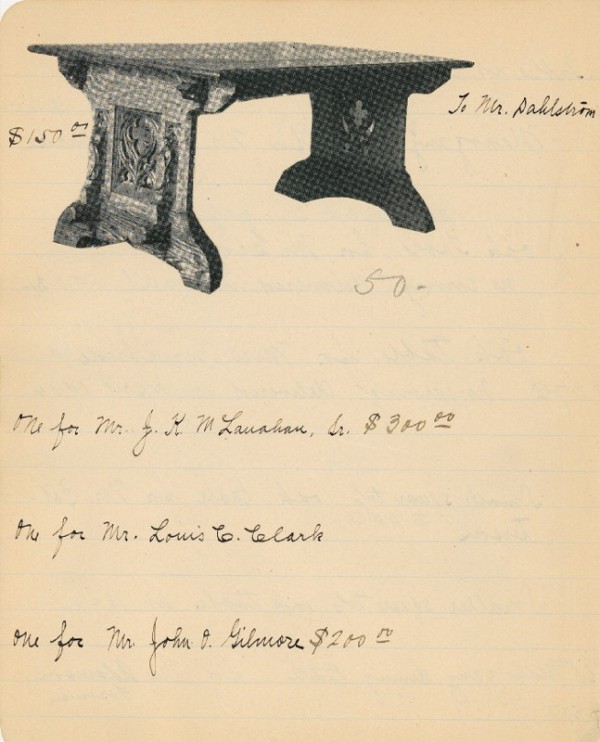

Page from an order book maintained by the Price McLanahan office in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1902–1915. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) This page illustrates the table shown in fig. 16 above a list of clients for whom variations of the trestle table form were made. M. Hawley McLanahan (1865–1929) became Price’s partner in the architectural firm that had offices at 1624 Chestnut Street. McLanahan was a real estate developer and office manager.

Trestle table designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1904. White oak. H. 29 1/2", W. 66", D. 39 1/2". (Courtesy, Robert Edwards; photo, Rick Echelmeyer.) This table was made in 1904 for George K. Crozer Jr., but his name does not appear on the order book page illustrated in fig. 15.

Trestle table designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1904. White oak. H. 39 1/4", W. 65 3/4", D. 28 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table, which bears the Rose Valley brand, is smaller than the example illustrated in fig. 16 but is otherwise identical.

Trestle table designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1903. White oak. H. 29 1/2", W. 84", D. 40". (Private collection; photo, Rago Arts and Auction Center.) A ca. 1903 photograph of a room in John O. Gilmore’s house, Yorklynne, shows the trestle table along with several Rose Valley chairs. Price sold several tables to Gilmore. The order book listing (see fig. 15) may be for this, the largest example.

Trestle table designed by William Lightfoot Price and likely made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, or Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1904. Price and McLanahan designed the J. K. McLanahan Sr. house in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, where two Rose Valley tables were photographed. The larger table shown here, which may be the one listed in the order book, is now lost.

Trestle table designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. White oak. H. 29 3/4", W. 36", D. 23 1/2". (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table bears the Rose Valley brand.

Drawing of the table illustrated in fig. 20. (Artsman 1, no. 1 [October 1903]: 12.)

Detail of the top and frame construction of the table illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Price always used functional joinery to construct the furniture he designed, which is an identifying feature now used to distinguish unsigned Rose Valley furniture from contemporaneous production.

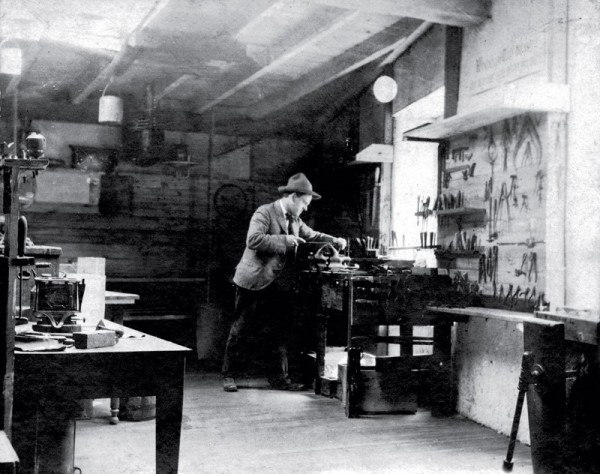

Photograph of the interior of the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

Photograph of Henry Hetzel in his workshop, Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1904. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Photograph showing the living room of the House of the Democrat, Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1906. (Durando Nichols, “The Model Home: Some Successful Small Houses Costing from $1,200 to $2,400,” American Homes and Gardens 2, no. 1 [March 1906]: 161–65.) Hetzel made much of the furniture visible in this photo, including the bench illustrated in fig. 27.

“Rose Valley Gothic Bench: Designed, Drawn and Built by Henry Hetzel,” Artsman 2, no. 11 (August 1905): 352.

Photograph of the bench made by Henry Hetzel (fig. 28) next to a stand that appears to be his copy of a commercially produced example, ca. 1905. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Bench made by Henry Hetzel at his woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. White oak, H. 27", W. 37 1/2", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

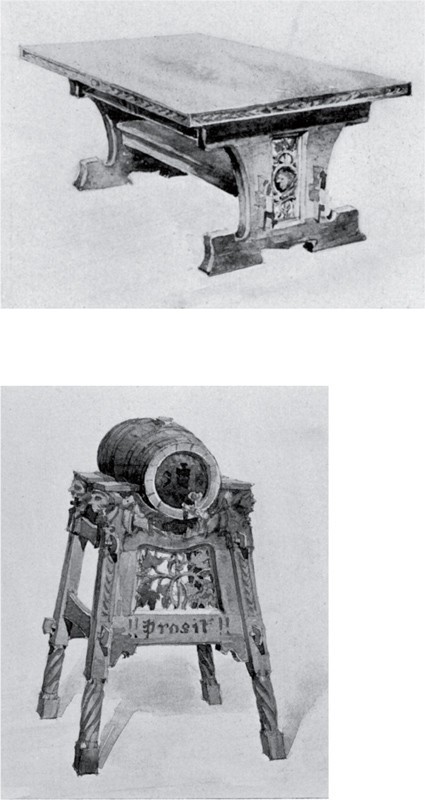

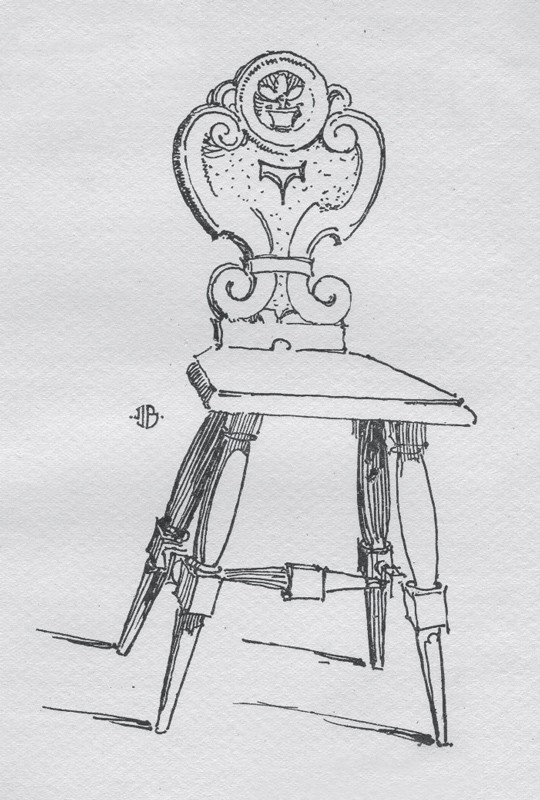

Furniture designs by John Bissegger, Catalogue of the Annual Architectural Exhibition (Philadelphia: T Square Club, 1899–1900), p. 52.

Armchair designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. White oak. H. 45 1/4", W. 25 1/4", D. 25 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair bears the Rose Valley brand. An identical chair with a leather seat appeared in a line-cut illustration in Artsman 1, no. 1 (October 1903): 4.

Armchair attributed to Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1895. White oak. H. 51 1/2", W. 21 1/2", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Vitrine designed and made in Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1900. White oak; glass. H. 46", Diam. 21 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Price would never have designed such a fanciful piece of furniture as this round vitrine supported on three caryatids, whose form and costume are an art nouveau interpretation of a classical convention.

Illustration from a Tiffany Studios advertisement, House Beautiful 29, no. 5 (April 1911): XLIII.

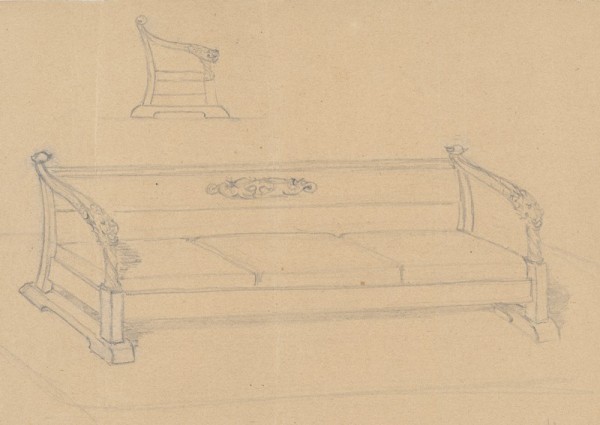

William Lightfoot Price, design for a couch, Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1904. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

William Lightfoot Price, design for a gateleg table, Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1905. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) A circa 1905 photograph now at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia documents that the Rose Valley shop made a mahogany table of this type for W. F. Davidson. This style would have been called Queen Anne.

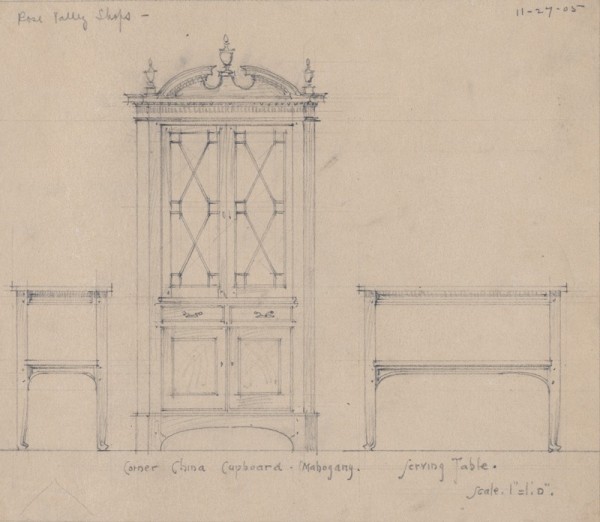

William Lightfoot Price, design for a “corner china cupboard and serving table,” Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1905. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

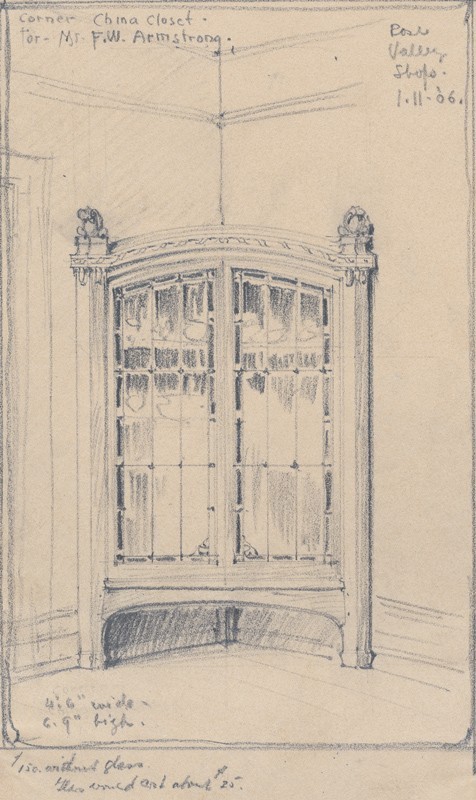

William Lightfoot Price, design for a “Corner China Closet for Mr. F. W. Armstrong,” Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1906. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) In this design, a Georgian furniture form has been embellished with Gothic details.

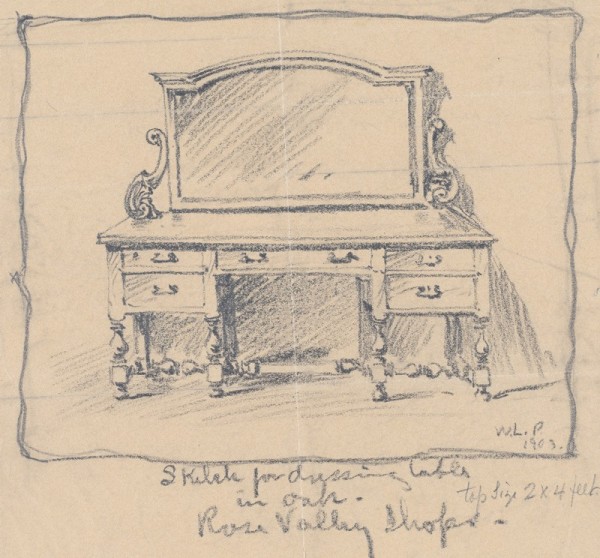

William Lightfoot Price, “Sketch for Dressing Table in Oak,” Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1903. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) Although Price was well versed in antique furniture styles and often labeled his designs as “Gothic” or “Jacobean,” he was never pedantic in his interpretations. Modern forms like this dressing table required an eclectic mix of elements.

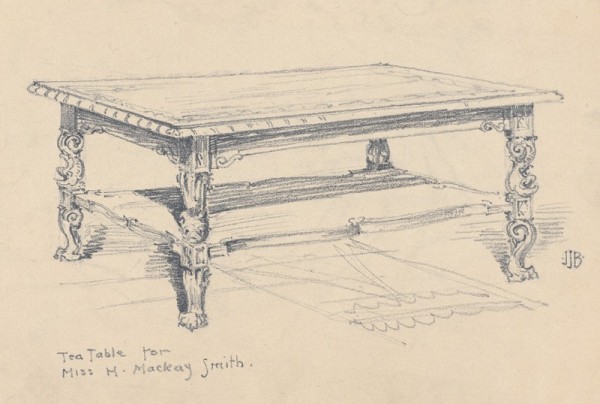

John Bissegger, design for a “Tea Table for Miss H. Mackay-Smith,” Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, 1905. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The Mackay-Smith commission included some of the most elaborate and stylistically eccentric designs ever devised at the Rose Valley shop. Bissegger made this drawing on paper with a Rose Valley letterhead. Dolphin carvings are not typical of work from Rose Valley, but they do appear on furniture designed and made by Edward Maene (figs. 8, 31).

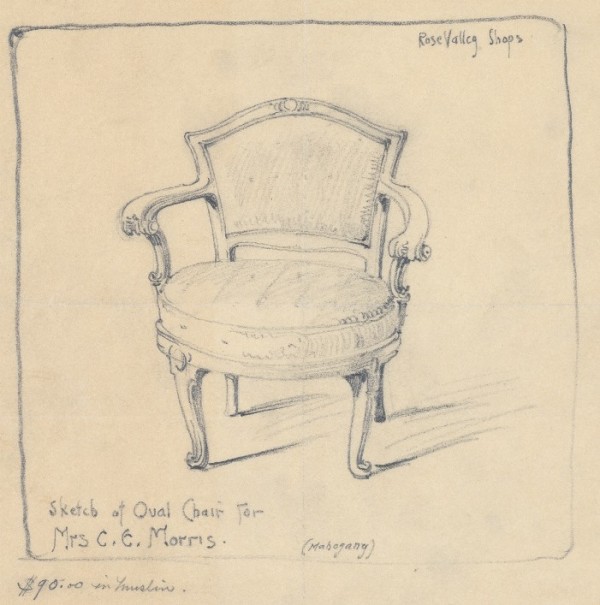

William Lightfoot Price, “Sketch of Oval Chair for Mrs. C. E. Morris,” Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1905. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) In this design Price accommodated his client’s desire for a relatively tepid interpretation of the rococo-revival style.

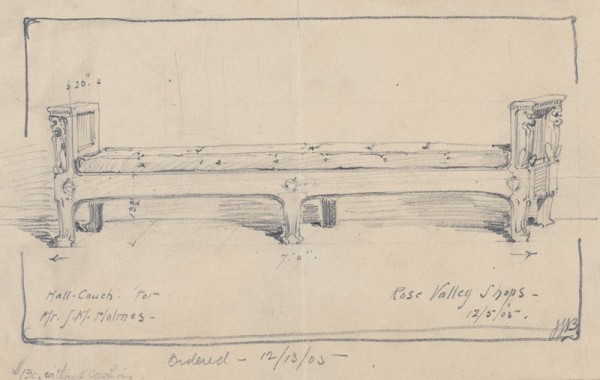

William Lightfoot Price, design for a “Hall Couch for Mr. Jos. Holmes,” Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, December 5, 1905. Graphite on paper. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Hall couch designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, or Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1905. White oak. H. 25 3/4", W. 84 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An inscription on the drawing (fig. 41) indicates that Holmes ordered this couch on December 13, 1905. This piece, which bears the Rose Valley brand, differs from Price’s drawing in having heraldic lions rather than eagles.

Photograph of the dining room in Thunderbird Lodge, Rose Valley, Pennsylvania. (Ralph de Martin, “Homes of American Artists: An Artist’s Home in Rose Valley,” American Homes and Gardens 6, no. 3 [March 1909]: 98.) Price designed the house and studios to enshrine Frank Stephens’s important collection of Native American artifacts and his wife Alice’s collection of American antiques.

Photograph of artist Francis Day’s studio above Folk Hall, Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1905. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) Day’s portrait of William Lightfoot Price is on the easel near the center of the room.

Photograph of the living room in the George G. Greene house, designed in 1911 by William Lightfoot Price and Martin Hawley McLanahan, Woodbury, New Jersey, ca. 1912. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) It is not known whether Price or Greene ordered the Stickley furnishings.

Photograph of the stairway in the John Clarke house, Bryn Mawr, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1897. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) William Lightfoot Price altered a Frank Furness design in 1896.

Photograph of the main stairway of the Frank H. Wheeler house, designed in 1911 by William Lightfoot Price, ca. 1914. (Courtesy, Drawings and Documents Archive, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana.) The style of the carving in the Wheeler house is more modern than that in the 1896 Clarke house (fig. 46), but certain elements, like the figures on the newel posts, remained essentially unchanged.

Photograph of the main hall of the Frank H. Wheeler house, designed in 1911 by William Lightfoot Price, ca. 1914. (Courtesy, Drawings and Documents Archive, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana.) Price probably designed the marble center table, but the rest of the furnishings came from Tobey Furniture Company.

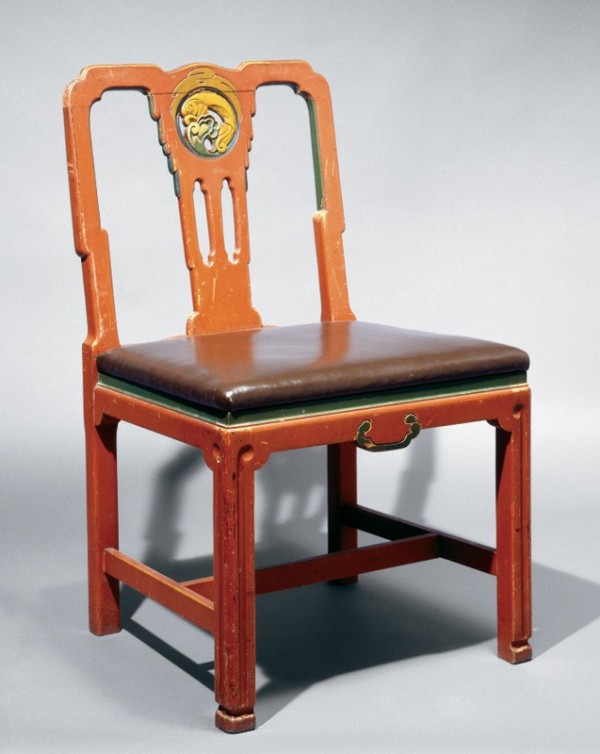

Chair specified by William Lightfoot Price for a dining room in the Traymore Hotel, Atlantic City, New Jersey, ca. 1915. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Julie Marquart for Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc.) Price probably subcontracted the Traymore polychrome furniture and the Wheeler dining chairs to a factory like Tobey Furniture Company.

Photograph of the dining room in the Frank H. Wheeler house, designed in 1911 by William Lightfoot Price, ca. 1914. (Courtesy, Drawings and Documents Archive, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana.)

Chromewald dining chair designed by Gustav Stickley and made at the Craftsman Workshops, Eastwood, New York, ca. 1915. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Thomas Gleason.) Stickley’s polychrome furniture is less modern than Price’s contemporaneous painted designs.

Pair of chairs designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, or Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1904. Oak. H. 36 1/4", W. 14", D. 18 5/8" (left); H. 37", W. 14 5/8", D. 19 5/8" (right). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Evidence suggests that Price sold chairs of different designs as a pair. This pair descended in the family of his brother Walter.

Pair of chairs designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, or Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1904. White oak. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

Pair of chairs designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, or Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1904. White oak. H. 37", W. 14 5/8", D. 19 5/8". (Courtesy, Freeman's; photo, Elizabeth Field.)

Faltstuhl, Tirol region of Austria, late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. (Jacob von Falke, Mittelalterliches Holzmobiliar, 2nd ed. [1894; Vienna: Schroll, 1897], pl. 7.) (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) This chair inspired the work of several early twentieth-century furniture makers, including William Lightfoot Price.

Folding chair designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, or Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. White oak. H. 29", W. 23 1/2", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The upholstery is replaced. An identical chair descended in the J. K. McLanahan family, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art has a drawing of another designed for the Mackay-Smith family.

Photograph of a clay model from which the finial on the chair illustrated in fig. 56 was carved, probably in Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

Detail of the finial of the chair illustrated in fig. 56.

Photograph of the attic of William Lightfoot Price’s house, Kelty, Lower Merion, Pennsylvania, ca. 1902. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) Price’s house was built in 1895 and had an attic in the ratskeller style. Chairs identical to those Don Stephens built for the dining room of his house in Arden, Delaware (see fig. 63), are in the center. Given Price’s fascination with American antiques, he might well have been aware of similar chairs made by colonists of northern European descent in southeastern Pennsylvania. It is also possible that he saw published illustrations of brettstuhls.

Brettstuhl, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1740–1770. White oak and yellow pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Philip Bradley Antiques.)

John Bissegger, drawing of “A Rose Valley Hall Chair,” Artsman 2, no. 6 (March 1905): 192.

Chair designed by William Lightfoot Price and made by Don Stephens, Arden, Delaware, ca. 1915. White oak. H. 35 1/2", W. 16", D. 16". (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Photograph of the dining room in Don Stephens’s house, Bide-a-wee, Arden, Delaware, ca. 1916. (Courtesy, Arden Craft Shop Museum.) A chair identical to that illustrated in fig. 62 is at the right end of the dining table.

Hall chair attributed to Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1900. White oak. H. 37", W. 15 3/4", D. 18 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Anna Jordan, desk, Cincinnati, Ohio. Walnut. H. 30", W. 38", D. 19". (Courtesy, Rago Arts and Auction Center.) In general, students at the Cincinnati carving school run by Benn Pitmann and William and Henry Fry did not make the furniture they carved, which resulted in complex surface decorations that spread over the wood surfaces like a slipcover. Price’s carving designs were intended to be integral to the structure as on the Rose Valley table illustrated in fig. 66; he did not use carving as mere surface decoration.

Trestle table designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in the woodworking shop at Rose Valley, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1903. White oak. H. 30", W. 48", D. 35 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chair, typewriter cover, and table designed by William Lightfoot Price and made in Edward Maene’s shop, 309 Griscom Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1906. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) These objects were made for the Mackay-Smith family.

There is no such thing as style until the style is dead. Style is only vital in the transition period—while men are working at it, perfecting it, keeping it still in a state of solution. There could be no such thing as style in the present tense.

—William Lightfoot Price, 1904

The Rose Valley Shops, which produced furniture from 1901 until 1906, were located at architect William Lightfoot Price’s (1861–1916) utopian experiment near Moylan, a suburb of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where the houses he designed exhibit many characteristics of the Arts and Crafts style (fig. 1). Beyond the Rose Valley community, Price’s furniture is most often used to demonstrate his commitment to the Arts and Crafts philosophy in general and to William Morris’s idea of a “banded workshop” in particular (fig. 2). Furniture bearing the Rose Valley Shops’ mark has been studied within the context of the American Arts and Crafts movement since Robert Judson Clark’s landmark exhibition, “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1876–1916,” opened in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1972 (figs. 3, 4); however, Price’s design vocabulary and the “structural theory” he employed were fully formed years before the workshops began production in an old mill on Ridley Creek, and he continued to design furniture after the shops closed in 1906. It is difficult to reconcile Price’s rigorous version of the simple life as published in his magazine the Artsman with the grand and gaudy châteauesque mansions he designed, where furniture made in the Rose Valley Gothic style was sometimes placed alongside sharply contrasting plain furniture from the Craftsman factory operated by another icon of the American Arts and Crafts movement, Gustav Stickley (1858–1942) (fig. 5). The incongruity may be more jarring to the early twenty-first-century connoisseur who perceives Stickley’s designs as progressive and Price’s as historicist; early twentieth-century consumers were more aware of the antique prototypes that inspired both Stickley and Price, for whom reference to a romanticized past was an important component of their version of the Arts and Crafts simple life.[1]

Although Price probably learned some carpentry before studying with Philadelphia architects Addison Hutton and Frank Furness, he had little experience in furniture making, unlike Stickley, who worked in his uncle’s furniture factory before striking out on his own. Nor was Price a trained wood-carver, as was his contemporary Karl von Rydingsvärd (1863–1941), who learned to build and carve furniture at the Royal Technical School in Sweden. However, Price did visit Britain and Europe, where he made detailed drawings of buildings and antique furniture. For Price, those notes constituted a reference library of construction techniques and primarily Gothic motifs that he later incorporated in his designs for architectural woodwork and freestanding furniture.[2]

Price may have developed preferences for certain carving styles while traveling in Europe, although it is equally possible that his tastes were influenced by the plethora of hand-carved woodwork produced by his peers. John Kirchmayer (1860–1930) studied carving in Oberammergau, Germany, before coming to the United States, where he carved vast quantities of Gothic ornament to the designs of architects like Ralph Adams Cram and Henry Vaughn. Kirchmayer worked in the manner of medieval artisans, who seldom left intentional evidence of the gouges they used to form their sculptural decorations (fig. 6). In contrast, Karl von Rydingsvärd—lauded in 1909 as “the foremost woodcarver of America”—was influenced by Norse antiquities, and his carvings often relate to the two-dimensional interlacings characteristic of the Viking style, which he helped to popularize. He occasionally left evidence of his gouges, particularly when flattening the surfaces of boards for use in paneling, but most of his softly swelling ornamentation is smooth (fig. 7). Edward Maene (1852–1931) and his nephew John (1863–1928) learned to carve wood and stone in Belgium. They immigrated to the United States in the early 1880s. By 1894, the Maenes had a workshop in Philadelphia and John was advertising as a sculptor offering “Art Furniture” as well as “Interior and Exterior Decorations.” John worked with his uncle in the city until he became the foreman of the Rose Valley furniture shops in 1902 (fig. 8). Price provided drawings for every detail of Rose Valley furniture and then oversaw its production, thereby controlling the style of carving. The ornamentation the Maenes carved for Price always exhibits subtle facets left by shallow gouges, but Price believed in using modern planing machines so one never sees the marks of hand tools on the undecorated, flat surfaces of Rose Valley furniture (fig. 9).[3]

Price occasionally ordered architectural carving and woodwork from large firms, like Pottier and Stymus of New York, but his principal source was John and Edward Maenes’ Philadelphia shop. Price hired the Maenes to build a cabinet commissioned in 1903 by Horace Trumbauer, architect of sugar baron William Harrison’s massive stone house Grey Towers. The cabinet was intended to hold Harrison’s four volumes of Shakespeare, which included a Merchant of Venice folio purchased from Philadelphia book dealer Philip Rosenbach. Edward Maene carved the cabinet with Gothic motifs referencing Shakespeare and supervised its assembly, which occurred in the Maenes’ Philadelphia shop rather than at the Rose Valley shop, where John had recently become master. Even though countless detailed letters and drawings about each step of production were exchanged between the architect, patron, and producers, Harrison was unhappy about the cost of the cabinet and instructed Trumbauer to sue Maene. In the latter’s defense, Price solicited the opinion of tastemaker, architect, and University of Pennsylvania professor Warren P. Laird, who described the cabinet as “the finest piece of furniture ever made in this country” (figs. 10-14).[4]

The Gothic style offered Price the best opportunity to demonstrate what he and Stickley referred to as the “structural idea”—allowing construction to be the guiding principle of furniture design. Arts and Crafts scholars have made much of that principle, but it was not unique to that style and was often used as a marketing ploy, mantra-like, to denigrate contemporaneous, mass-produced furniture. At issue was the “honesty” of furniture construction and design. Price wanted his furniture to be exactly what it appeared to be. His Gothic tables are made of sturdy oak boards, assembled with visible joinery and kept in place with butterfly joints and elaborately carved pins (figs. 15-19). When the pins are removed, the tables can be disassembled and easily moved. Portability may have been a consideration in many of Price’s designs, since his furniture was not sold through showrooms in major cities other than at Price’s architectural offices at 1624 Walnut Street, in Philadelphia (figs. 20-22). His furniture was exhibited at the Society of Arts and Crafts in Boston, the Guild of Arts and Crafts in New York City, and the Saint Louis World’s Fair of 1904 (three chairs, a bench, and a “Gothic table”), but most of his public exposure was through advertisements placed in magazines with large circulations like House and Garden and smaller periodicals like the Artsman.[5]

In 1904 John Maene advocated the integration of design and production in an article in the Artsman:

In executing designs variations will spontaneously occur, some of them wonderfully advantageous . . . that . . . would have been impossible even to imitate on paper. This is no doubt where the creative mind of the carver or modeler will ascertain itself. . . . It is fortunate if the [maker] . . . is also the designer of his work.

However much Price may have agreed with Maene in theory, in practice he separated design from production.[6]

The designs Price furnished to guide his craftsmen’s work are distinctive enough to support attributions to the shops at Rose Valley and Arden, Delaware, another utopian community he founded. A circa 1903 photograph of the Rose Valley shop shows him drawing at a table in the back, an unidentified craftsman using a smooth plane to finish a large piece of stock at his workbench, and John Maene carving a Gothic panel in the foreground (fig. 23). The furniture and carved components are oriented to provide optimal frontal or oblique views; the middle bench is angled to provide an unobstructed view of the work surface. The Gothic table closest to the camera descended in the family of Price’s brother Walter (see fig. 66). The panels John Maene is working on are identical to panels used on the table made for John O. Gilmore (fig. 18). A drawing based on this photograph of the shop appeared in the December 1903 issue of the Artsman; thus, one might assume that Price had a hand in the photograph’s setup. In the visual hierarchy of the composition, handwork and the craftsmen responsible for it are at the forefront; however, Price’s presence suggests that he wanted viewers to see that he was intimately involved as a designer and manager.[7]

Price’s oversight is reflected in the carving he designed for mansions, smaller houses in his utopian communities, and furniture. This work is remarkably consistent despite the fact that it was executed by several different workmen and made for a wide range of patrons and projects. Price’s designs were more restrained than those of Edward and John Maene, especially when the Maenes deviated from Price’s designs.

Price influenced a number of artisans who worked for him, including Henry Hetzel, who became a member of the Rose Valley community in 1903. Hetzel rented part of an old bobbin mill where he set up a shop for metal- and woodwork and made furniture for the House of the Democrat—a model home designed by Price and intended to cost between $1,200 and $2,400 (fig. 24). Several pieces of Hetzel’s furniture are visible in an interior photograph published in the March 1906 issue of American Homes and Gardens (fig. 25), including a bench whose design appeared the previous year in the Artsman (figs. 26, 27). Hetzel’s bench, which survives with its original green corduroy cushion, has through-tenoned rails that are locked in place with ornate keys and shaped sides with cutouts and carved details similar to those on furniture designed by Price and made at Arden (fig. 28). Architect John Bissegger (b. 1868), who was also associated with the Rose Valley community, published several drawings of furniture designed by Price in the Artsman. Bissegger also designed furniture, which resembles work from the Rose Valley shops but is more reliant on historical precedent (fig. 29).[8]

Price never intended the Rose Valley shop to produce furnishings for every aspect of the Arts and Crafts lifestyle, as did Stickley, who manufactured furniture for living rooms, dining rooms, bedrooms, and porches, as well as office furniture, chafing dishes, coal hods, andirons, curtains, bedspreads, lamps, rugs, and pianos. In fact, Price avoided some furniture forms because he thought they did not lend themselves to his design sensibilities. As a result, no freestanding chests of drawers, conventional couches, or beds from the Rose Valley shop are known. In contrast, Edward Maene designed a broader range of forms, finding inspiration in the prevailing European furniture fashions of the second half of the nineteenth century, which provided ample surfaces for his interpretations of Renaissance carved motifs (figs. 30-32).[9]

Price’s status as an Arts and Crafts designer is often misjudged because his interpretations of the movement’s theories are difficult to perceive in Arts and Crafts products, which are often indistinguishable from other fashionable furnishings produced at the turn of the last century. The work of Louis Comfort Tiffany, who designed metal objects, jewelry, pottery, and furniture along with his famous blown- and leaded-glass windows, is always prominent in American Arts and Crafts surveys even though there is little other than the era in which he worked to connect him to that movement. Tiffany objects on display in museums and offered at auction give the impression that most of his work was done in the art nouveau style, but many Tiffany Studio advertisements promoted Georgian or American “colonial” furnishings and ersatz interpretations of European antiques (fig. 33). As was the case with Tiffany, objects and buildings with obvious Arts and Crafts attributes formed a limited part of Price’s oeuvre. Although usually associated with work in the Gothic manner, Price produced designs for furniture in a wide variety of styles, including Queen Anne, Georgian, Jacobean, Renaissance, and Louis Quinze (figs. 34-40). He expressed his philosophical convictions through experiments in utopian community living, not through the furniture his shops made for the grandiose mansions he continued to design after establishing Rose Valley and Arden (figs. 41, 42). Householders in those communities typically used their own furnishings, including Native American artifacts, antique spinning wheels, and ladder-back chairs made locally in the Delaware Valley (figs. 43, 44).[10]

Price called for the use of Stickley’s Craftsman furniture in the Gilmore house in Merion (1899) and the Clarke (1901) and Graham (1902) houses in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, but the interiors of those dwellings included Gothic, Renaissance, and other historic details. Although the Craftsman furnishings in the Greene house (1911) in Woodbury, New Jersey (fig. 45), were more in harmony with the architecture, photographs of the Frank Wheeler house (1911) in Indianapolis suggest that the simplicity of the Greene house and its furnishings did not represent a significant shift in Price’s designs. The woodwork in the Wheeler house is made of mahogany rather than dark oak, which Price used in most of his houses, and has carved floral motifs that reference the Vienna Secession. The newel posts, however, are topped with the same loosely draped figures that Price used in his French Gothic houses (figs. 46, 47).

Lionel Robertson, an artist and decorator who worked with the Tobey Furniture Company of Chicago, provided most of the “fitments” for the Wheeler interiors. Among the objects he designed were armchairs that stood in the front hall and a tall-case clock at the top of the stairs. The object most directly associated with Price’s work is a marble table made for the hall, which resembles several oak tables from Rose Valley Shop (fig. 48). His use of Tobey and Stickley furnishings leads one to assume that Price also subcontracted custom-made furniture for the large Atlantic City hotels he designed. Candidates for the latter class of work would include the Chinese red chairs used in the dining room of the Traymore Hotel, which relate to seating made for the dining room of the Wheeler house (figs. 49, 50). The Traymore chairs were probably produced for additions to the hotel in 1914–1915. Like Stickley’s contemporaneous Chromewald furniture (fig. 51), this seating deviates from mainstream Arts and Crafts work, although less so in the case of Price, who used painted and gilded decoration on earlier oak furniture, including a polychrome chair that descended in the family of his brother Walter (fig. 52).[11]

The chairs illustrated in figure 52 descended in the family of Walter Price. Both types of seating occasionally turn up with the same provenance, which suggests that Price recommended them for concurrent use (figs. 53, 54). It is possible that Price saw the antique prototypes for his versions displayed together when he was traveling through Europe or found them illustrated together in a book. He sometimes copied antiques with only slight modifications to scale or detail (figs. 55-58).

In an article extolling the potential for ratskeller design in American architecture, Price wrote, “[Thomas] Carlyle says that ‘originality does not consist of being different, but in being sincere.’” Although not solely because of Price’s advocacy, the ratskeller’s vaulted ceilings and quaint furnishings showed up in many American interiors, especially restaurants. Furniture and architecture from the Tyrolean regions of Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy inspired several American craftsmen during the Arts and Crafts era. Price’s peer Wilson Eyre quoted the ratskeller in his famous design for the 1894 Mask and Wig Club in Philadelphia. Price himself was fond of the proportions of the broad foundation arches that formed the ceilings of Kellers (cellars), and, despite his concerns about sincerity, he used broad arches everywhere except in basements. Period photographs of the broadly arched third-floor space of Price’s house Kelty show “Tyrolean” chairs, which are similar to seating made at Arden by Don Stephens (fig. 59). In the ratskeller article, Eyre wrote, “But the way we do the thing is after all much more important than what we do, especially if the method is ours and what we do is, in the main, let us say borrowed.” As Bissegger’s drawing of “A Rose Valley Hall Chair” in the March 1905 issue of the Artsman indicates, Price’s designs for that genre of seating have tenoned legs and board seats and backs that were derived from brettstuhls but occasionally decorated with Gothic or Renaissance motifs (figs. 60-64).[12]

The idiosyncratic Gothic style associated with the Philadelphia area in general and Price’s mentor Frank Furness in particular had its roots in the reform ideas of such British designers as Augustus Welby Pugin (1812–1852) and Christopher Dresser (1834–1904). Dresser’s “Modern Gothic” designs echoed Pugin’s penchant for forms without obvious historical precedents. Price’s Gothic furniture almost always shows a deep understanding of antique styles and traditional joinery, but it never results in mere mimesis. Although Rose Valley furniture cannot be mistaken for anything other than the product of the early twentieth century, Price’s work relates to the various reform movements in theory, not in appearance (figs. 65, 66).[13]

Design mavens now place a premium on originality and progressive modernism, whereas Price dismissed existing doctrines of beauty and style as irrelevant. Assessments published in the Artsman, which served as a forum for Price’s opinions, are often difficult to understand because he failed to specify when his use of the term “artsman” referred to himself or to a craftsman in general:

One of the many things which the artsman must avoid is stupefying doctrine. It is quite possible to create doctrines of style, which would be destructive of the artsman ideal. The artsman has no one style. He encourages creation. He advises invention, divergence, innovation. None of them at the expense of truth. He does not say a table must be of a certain style. That any other style is heresy. That only one style is endorsed by the creed. That judges and juries may save and condemn. The artsman leaves style to the artsman. All that the artsman asks is that what you do shall be done on the square. Yes, in the right spirit. Honestly. . . . You as an individual may not like his style. You may find his taste unpleasing. But if he is self-consistent, if he has obeyed the rigorous law of his own mastership, he arrives among the artsmen, enlisted in the service of the industrial ideal. . . . It is not your privilege to say: This is not pretty—therefore you are no artsman. Does it give honest reasons for itself?[14]

This passage can be interpreted as a sweeping rejection of aesthetics in the assessment of a craftsman’s work. However vague the term “right spirit” may appear to modern readers, it was the only measure of worth Price could accept. Honesty and truth were refrains in the Arts and Crafts anthem, but they were seldom put into practice in the American version of the movement, where marketing and profitability were paramount. Large companies like the Rookwood and Grueby potteries and the Stickley brothers’ various furniture-making enterprises used Arts and Crafts rhetoric in their advertising, but these companies would not have been successful if they had ignored style, as Price understood it. Studio artisans like potter George Ohr and woodworker Charles Rohlfs also recognized the importance of marketing. They succeeded in making their distinctive styles a commodity because consumers were—and still are—typically more interested in the appearance of objects than the method of production. Rohlfs’s furniture was most often categorized as art furniture and used as accents in conventional interiors rather than as parts of harmonious ensembles. This was also true of Price’s furniture, but he rationalized his marketing by asserting that the craftsman’s “best chance for establishing a life of simplicity and artsmanship seems to be at present in the making of things that are more or less expensive and that only the well-to-do can buy. We must meet the market of the time in which we live, until our new world is born, and plenty and peace have taken the place of ‘prosperity’ and war.”[15]

The Arts and Crafts movement attempted to eliminate the lacuna between the lifestyle of the rich and the lifestyle of the poor by elevating esteem for “a life of simplicity,” but it seldom proposed such a grand prospect as bringing peace and plenty to Everyman. The vision that linked prosperity to peace grew from Price’s Quaker roots. His extended family was prominent in the greater Philadelphia community of the Society of Friends, giving him a ready-made context within which to codify his unique version of the Arts and Crafts movement.

The Quaker influence in Philadelphia culture began when William Penn founded the Province of Pennsylvania in the late seventeenth century. Many of the society’s principles regarding the simple life shaped the Arts and Crafts movement as it developed in the region during the nineteenth century. The sect’s founder, George Fox, believed that each person has “Inner Light,” which allows an individual experience of God without the intervention or interpretation of a mediating agent like a priest. The Arts and Crafts philosophy held that anyone, regardless of training or financial standing, had the capacity, or “right spirit” as Price described it, to bring beauty into daily life. The Quaker faith’s ideas about simplicity, truth, harmony, and equality parallel the primary tenets of the secular Arts and Crafts movement and are today similarly misperceived. In the popular understanding of simplicity or “plainness,” an elaborate eighteenth-century mahogany high chest of drawers owned by a Philadelphia Quaker and a richly carved twentieth-century Rose Valley table commissioned by a Philadelphia industrialist would seem to contradict Quaker and Arts and Crafts philosophies, respectively. However, Friends have never been required to eschew luxury; they are enjoined only to avoid vain expressions that might distract them from pursuing their Inner Light. As Price defined the Arts and Crafts, truth to materials and honest construction did not require plainness or preclude carved embellishments. Quakers were encouraged to live in ways similar to Arts and Crafts utopian theory. Congregations were not necessarily geographically distinct units, but Quaker meetinghouses were the centers of communities of closely related families. Price’s relatives constituted, until very recently, the majority of Rose Valley’s inhabitants, where Artsman’s Hall functioned as the community meetinghouse. A nondenominational church was planned for Arden, but it was never built, so a clubhouse served as the meeting place for the residents, many of whom were related.[16]

It is difficult to ascertain the size of Price’s furniture production because the records pertaining to his furniture designs and sales are numerous but incomplete, and it is impossible to determine how many objects were made in the shop at Rose Valley, the Maenes’ Philadelphia workshop, or at Arden. A scrapbook associated with Rose Valley lists orders for specific furniture designs, but some of the objects may have been made elsewhere, including known examples bearing the shop brand. Further confusion results from the fact that orders listed under a photograph of a particular design were not always for identical objects. Photographs or drawings do not accompany all orders, and many surviving objects do not appear in the scrapbook. Several important commissions—for Alexander Mackay-Smith and his daughter Helen, Spencer K. Mulford, and Joseph Fels—included furniture designed in 1906, after production at Rose Valley ended (fig. 67). Presumably, that work was done in the Maenes’ Philadelphia shop. Even so, the records suggest that fewer than five hundred pieces of furniture were produced at the Maenes’ shop and the Rose Valley shop combined. Production would have been considerably greater had Price won commissions from institutions like the University Club of Chicago, whose building was competed in 1909. Price sent sketches for furnishings for the “Ladies’ dining room (30 tables and 80 chairs), the main dining room, the assembly room, and the ‘College Hall.’” He noted that the furniture was to be made in “quartered white oak, stained and finished with wax. All to be special hand-made furniture with all joints mortised, tenoned and pinned.” The club’s architects, Holabird and Roche, seem not to have been impressed by the promise of sturdy handwork because they chose the more prestigious Tiffany Studios to provide the furnishings.[17]

During the first decades of the twentieth century, many tastemakers favored stained and waxed white oak. In December 1910 Walter A. Dryer wrote:

Oak is coming to its own again. It is bound to. Not only in the cheap golden-oak furniture and in the solid mission and craftsman styles, but in simple wax finishes that leave it stand on its own merits. It is in improved methods of finish, in fact, that its salvation lies. Whether carved or plain, whether fumed or silvered. Whether dull or highly polished, it is beautiful, and in the best antique finishes it surpasses all other woods for library and dining room.[18]

Judging from Price’s interior woodwork and the furniture made at Rose Valley, the characteristic brown stain and wax finishes used by his workmen were durable and of high quality. Taft and Belknap Galleries of New York registered the only known complaint in 1904. The firm was angry that a Cabot stain, instead of a custom formula, was used on a wood box supplied to a New Jersey client: “If your workmen are not sufficiently versed in stain, and don’t know how to mix colors without using some patent stain, it is well time you paid for the experience.” Price and the Maenes knew how to mix colors and stains and instructed their workmen in the preparation of finishes they preferred. A letter Price wrote to the superintendent of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition described the application of a creosote stain, which was

applied with a brush and rubbed down with cotton waste within the hour. After drying for 12 to 24 hours the wood was given a thin coat of boiled linseed oil, the oil rubbed, as the stain was and left to stand for twenty-four hours, and finished with wax . . . and rubbed with an ordinary shoe polishing brush.

Creosote is made from tars produced from the carbonization of bituminous coal; its use is now regulated because it is a carcinogen, but in 1904 it was widely used as a wood preservative and colorant. The black tar changes to a rich transparent brown when properly thinned. The Samuel Cabot company patented its formula in 1884 and advertised that the stains produced by the firm were “made of Creosote, pure linseed oil and the best pigments,” leaving one to question the variations described in the Taft and Belknap complaint.[19]

By Price’s measure, his style and that of the Arts and Crafts movement are dead, and he would probably have rejected the romantic notion that there could be a modern manifestation of either. Assessing the degree to which Price, Stickley, or Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony founder Ralph Radcliffe-Whitehead adhered to an Arts and Crafts philosophy helps develop a portrait of each individual, but it is not a meaningful gauge of the success or failure of what those men produced. Furniture making stopped at Byrdcliffe by circa 1904, the Rose Valley shop closed in 1906, and by the time Price died, a decade later, Stickley’s businesses were in decline. Modern scholars, conflating longevity with merit, have judged all of these experiments in craft production to be failures. Such pronouncements about products of the Arts and Crafts movement seem both arbitrary and unique in decorative arts history. Traditionally, historians of American woodworking and furniture making have based discussions of merit on regionalism, quality of craftsmanship, technique, and aesthetics. Nineteenth-century industrialization added the new modifiers of mass production, originality, progressivism, modernity, and globalization.[20]

Regionalism was central to Price’s architecture and philosophy but not to his furniture design. New and antique Gothic furniture was imported by the boatload from Europe and shipped to every part of the United States. Large domestic furniture factories and smaller cabinetmaking enterprises also satisfied demands for the style. Craftsmanship, not regionalism, distinguishes Price’s furniture. His logical designs, insistence on functional, handmade joinery, control of carving style, and consistent finish resulted in furniture of the highest quality. He did not reject modern technology outright, but his furniture was made entirely by hand after the wood had been sawn into boards and planed by machines. Mass production was never an issue for Price, as it was for Stickley, because the number of identical pieces the former produced was limited and, within that small number, significant variations occurred either by design or by accident of handwork. Price did not equate originality with creative integrity; he reserved progressive ideas for experiments in living rather than for crafts design. Price believed he was in the process of perfecting a solution. From our perspective in a future he could not have possibly anticipated, we can see modernity in his architecture if not in his furniture. The style and structure of the completed Wheeler house have the simple, solid shapes and new materials of the twentieth century, which replace references to the antique such as the post-and-beam construction, half-timbering, elaborate cut stone, and hand-carved woodwork found at the nineteenth-century Louis Clarke house.

William Price furniture designs may be a dead end on a linear time line that requires progressive modernity to move forward, but the short life of his Rose Valley shop does not represent a failure of his ideas or those of the Arts and Crafts movement. The theory of evolution does not invalidate that which does not evolve, and study of Price’s furniture helps codify and define his moment in the history of style.

William Lightfoot Price, “Man’s Expression of Himself in His Work: A Speech,” Artsman 1, no. 6 (March 1904): 219. In News from Nowhere, William Morris describes small rural or suburban workshops as alternatives to the huge factories that polluted industrialized British cities. He imagined beautiful buildings filled with strong young men laughing with young women as they worked (William Morris, News from Nowhere; or, an Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance [Hammersmith, Eng.: Kelmscott Press, 1892], pp. 88, 214, 223). Robert Judson Clark, The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1876–1916 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972). Gustav Stickley and contemporaries like Charles Rohlfs (1853–1934) often referred to antiques in their advertising. Stickley called a small table the “Tom Jones Drink Stand” and used “Flemish” and “Colonial Black” stains. Rohlfs included “Ben Franklin” and “Martha Washington” candleholders in his catalogues.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art owns two carving samples (acc. 2001-198-8, 9), which that institution attributes to either Price or George Frank Stephens. The attribution is based on circumstantial evidence provided by donor R. Emmett Murphy, but there is no documentary substantiation that Price learned to carve.

Period photographs in the Price McLanahan Archives at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia show the interior of a woodworking shop in which the Shakespeare cabinet is under construction. Visible through the shop window is a trade sign, which evidently hung on the façade of a building across a city alley. The Rose Valley woodworking shop was in an old mill beside a stream in a pastoral glade and could not have had a view of commercial establishments. Paula W. Healy, who is John Maene’s great-granddaughter, provided the genealogical information on her ancestor. Hawley McLanahan to Horace Trumbauer, November 3, 1904, Collection 41, box 14, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera (hereafter JDCMPE), Winterthur Library (hereafter WL), Winterthur, Delaware, gives the address of Edward Maene’s Philadelphia shop as “309 South Lawrence Street near 14th and Spruce.”

Price recommended “Pottier & Stymus” (Pottier and Stymus Manufacturing Company, New York City) make the woodwork for the James Turner house built at 5220 Ellsworth Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (William Price to J. J. Turner, June 23, 1905, Collection 41, box 14, nos. 126, 207, JDCMPE, WL).

Official Catalogue of Exhibitors: Universal Exposition, St. Louis, U.S.A. 1904 (Saint Louis, Mo.: Official Catalogue Company for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company, 1904), p. 85.

John Maene, “Modeling and Carving,” Artsman, 1, no. 6 (March 1904): 201.

The original photograph was taken with a glass negative, which required the use of a large, tripod-mounted camera. The shot was published repeatedly, suggesting that it was composed with its potential for publicity in mind.

For illustrations of the House of the Democrat, see Artsman 3, no. 5 (March 1906): 132; American Homes and Gardens 2, no. 3 ( March 1906): 161–62; and Craftsman 21, no. 2 (1911): 161–64, in More Craftsman Houses, edited by Gustav Stickley (New York: Craftsman Publishing Co., 1912), pp. 7–9.

For examples of the diverse home-furnishing products sold under Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman label, see Kevin W. Tucker, Gustav Stickley and the American Arts and Crafts Movement (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2010).

Period photographs suggest that Tower House was the only dwelling in Rose Valley in which furniture from the community shop was a prominent feature of the decor. Originally, William Price’s studio, Tower House, was altered by his son William Webb Price to serve as the family home after his father’s death. Most of the furniture in the living room passed to William Webb’s son Philip (1931–2007) when William Lightfoot Price’s daughter Margaret died in 1977. Philip had children by two wives; the first wife got some of Margaret’s furniture when they divorced. In 1983 most of the living room furniture was still with Philip in Maine or with his first wife and her children in New Hampshire. In preparation for the Brandywine River Museum exhibition “A Poor Sort of Heaven, a Good Sort of Earth: The Rose Valley Arts and Crafts Experiment,” the author visited the New Hampshire branch of the family and found Rose Valley benches splintered with canine tooth marks and the chair that appears to the left of the inglenook with a rug thrown over it in the Tower House living room photo in pieces in the attic. Daughter Jennifer had more Rose Valley furniture in her apartment in Candia, New Hampshire, including a drop-front desk that has never been recorded in photographs or drawings. She reported that the family had sold a “throne chair” to a local antiques dealer. Presumably, that object is the chair to the left of the rug-draped armchair in the Tower House photograph. The “monkey chair” in front of the “throne chair” is identical to the chair illustrated in fig. 56. There was one folding stool like the two in front of the “monkey chair” still in the Tower House when the author rented it in the early 1980s, as were the rickety built-in bookcases shown on either side of the front door in the photograph. The folding stool with the roundel carved in the back that sits behind the table in the foreground of the photo was taken to the Woman’s Club of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, and subsequently acquired by Estelle Jarden, who passed it on to her son George. The sculpture of the woman standing on the cabinet to the left of the front door once stood on a shelf in the Philadelphia Price McLanahan office; it was with Philip Price in 1983. Recent attempts to document the Price family furniture by contacting Philip’s children have proved unsuccessful.

Henry Blackman Sell, “Good Taste and the Mansion,” International Studio 57, no. 225 (November 1915): xi–xv.

Wilson Eyre, “Architecture and Rathskellers,” Architectural Review 9, no. 11 (November 1904): 233–37.

The “modern” in modern Gothic moved out of Philadelphia with Furness student Louis Sullivan, whose style evolved from the Gothic style into the Prairie School. In contrast, Price and other Philadelphia designers, including Wilson Eyre (1858–1944) and employees of the architectural firm Mellor, Meigs, and Howe (1906–41), produced more literal interpretations of historic styles. Price and regional architects and designers like Eyre and Frank Miles Day were contributors to House and Garden, which was published in Philadelphia. The magazine was distributed all across the United States; thus, Philadelphia domestic designs established a national country-house style that was accepted far more readily than the more radical style of the Prairie School architects.

William Lightfoot Price, “From the Artsman Himself, Note Six,” Artsman 1, no. 7 (April 1904): 268–69.

William Lightfoot Price, “What Do We Mean by Artsmanship?” Artsman 1, no. 2 (October 1904): 13.

Emma Jones Lapansky, “Past Plainness to Present Simplicity: A Search for Quaker Identity,” in Quaker Aesthetics: Reflections on a Quaker Ethic in American Design and Consumption, edited by Lapansky and Anne A. Verplanck (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), pp. 4–5. For an illustration of Price’s drawing of the church he proposed for Arden, see Mark Taylor, Images of America: Arden (Mount Pleasant, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2010), p. 73.

Order book, Price McLanahan Archive, Athenaeum of Philadelphia. William Price to Holabird and Roche, February 24, 1908, Rose Valley Manuscripts, FV:5:A, acc. no. 98.06, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Walter A. Dryer, “A Plea for Oak: The Foremost American Wood in Quality and Beauty of Grain,” Arts and Decoration 1, no. 2 (December 1910): 61–62, at 62: “American white oak is a hard, durable, strong wood, which, when quarter-sawed, shows a wavy cross grain that is peculiar to the wood and exceedingly beautiful. To cover this grain with a dark stain is to hide much of its beauty. But white oak is not naturally beautiful in color and we cannot wait for the mellowing effects of age. The fumes of ammonia are therefore resorted to, which, entering the dark pores, darken the wood not merely on the surface but to a considerable depth. A filler may be applied, for the grain of oak is coarse and needs it, and a French polish may be given as a final finish. The dull wax finish, however, is what is making oak popular again. This produces a durable surface to withstand the wear of usage, and yet leaves it in nearly its natural condition. With the occasional application of a little wax and elbow grease oak furniture thus finished will last for generations.”

Messrs Taft & Belknap to Price McLanahan, Collection 41, box 14, nos. 28, 26, JDCMPE, WL. The usual finish applied to Rose Valley furniture was described in a letter Price wrote to the superintendent of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, April 11, 1904, quoted in William Aryes, ed., A Poor Sort of Heaven, A Good Sort of Earth: The Rose Valley Arts and Crafts Experiment (Chadds Ford, Pa.: Brandywine River Museum, 1983), p. 54. John Siebecker, Cabot’s technical consultant, provided the patent date for the Cabot Shingle Stain. An advertisement for Rose Valley Shops appears in the same issue of House and Garden as an ad for Cabot’s Shingle Stains; see House and Garden 2, no. 9 (September 1902): iv, xvii.

Some scholars have asserted that Wharton Esherick (1887–1970), who has been characterized as the father of the modern art furniture movement, continued Price’s style into the early twentieth century because his early furniture was derived from Rose Valley furniture; the assertion is based on the fact that met his mistress, Miriam Phillips, at the Hedgerow Theater in Rose Valley. Esherick was friends with several Hedgerow denizens and made his first “hammer handle chairs” for the theater where Rose Valley furniture was sometimes used as stage props, so he may have seen one or two pieces. It is highly unlikely, however, that he knew of their history or that they inspired him in any specific way. William Lightfoot Price, “Is Rose Valley Worthwhile,” Artsman 1, no. 1 (October 1903): 7: “The object of man’s activities is no more and no less than the development of the countless powers and possibilities of the individual.”