John Townsend, high chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, 1756. Mahogany with white pine and ash. H. 88 1/2", W. 40 1/4", D. 21 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This high chest descended in the Arnold family of Warwick, Rhode Island. It retains its original finial, cast brass hardware, and finish.

High chest of drawers attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1770. Mahogany with yellow poplar. H. 84 1/2", W. 41", D. 21". (Private collection.) This high chest descended in the Dyer family of Providence, Rhode Island.

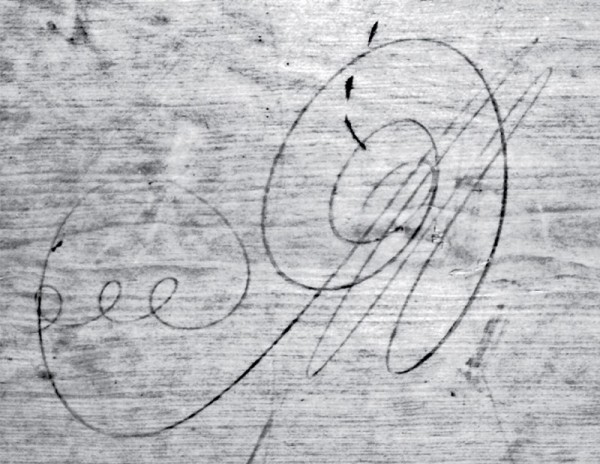

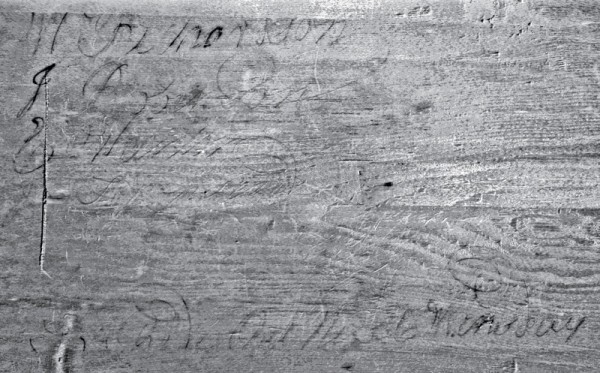

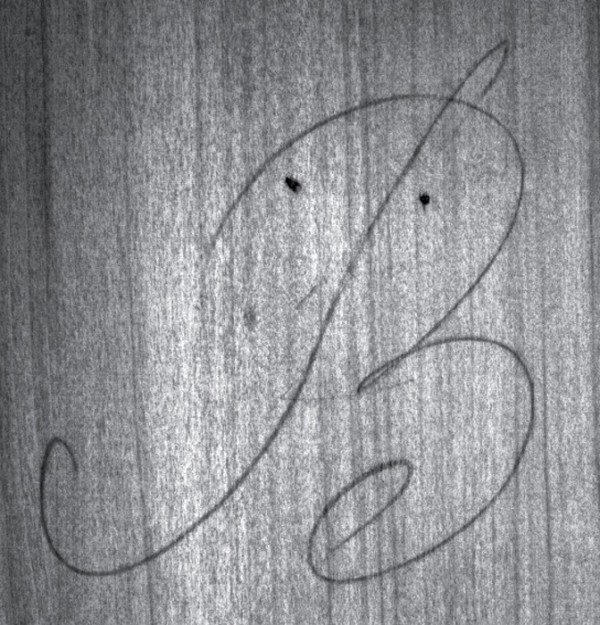

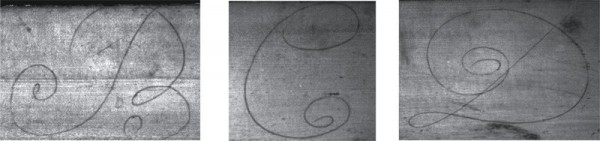

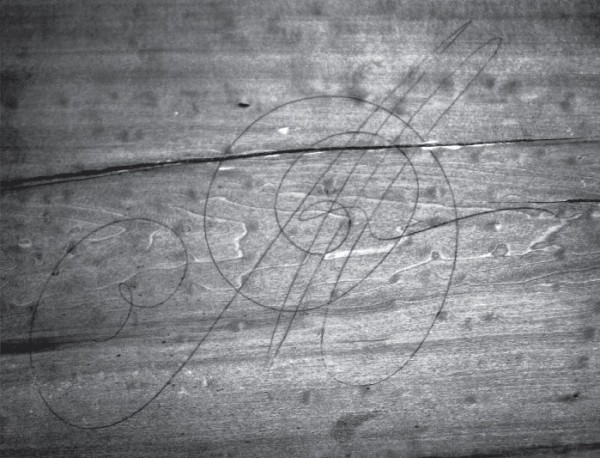

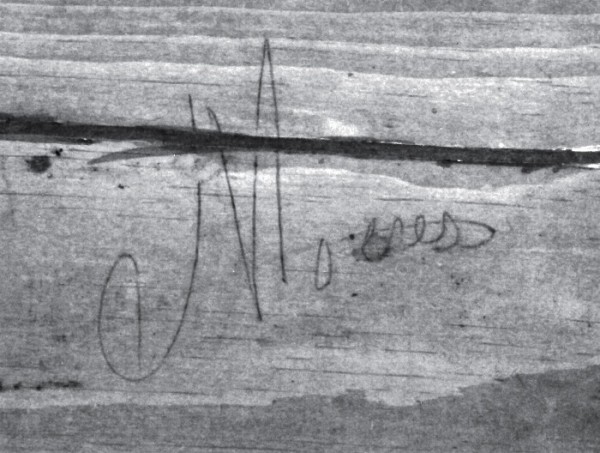

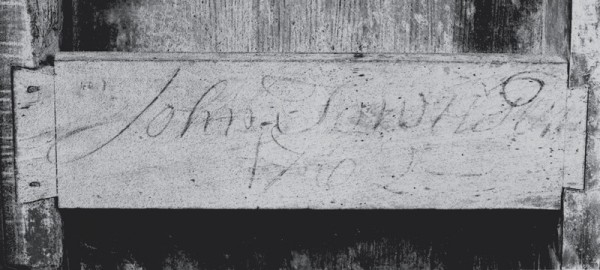

Detail of the graphite signature on the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

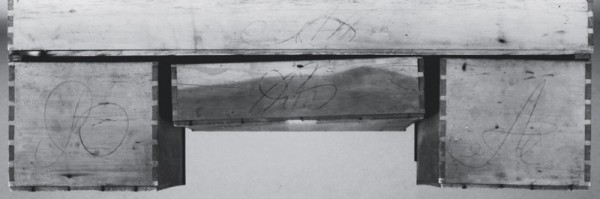

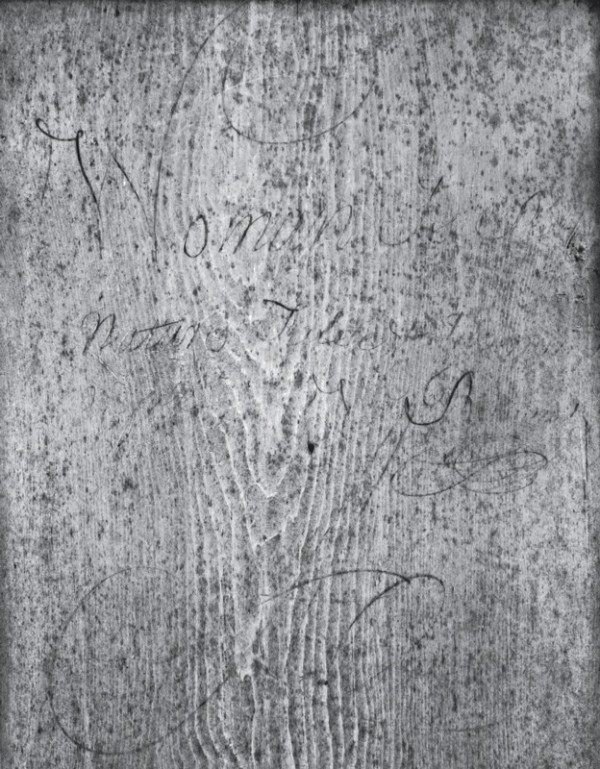

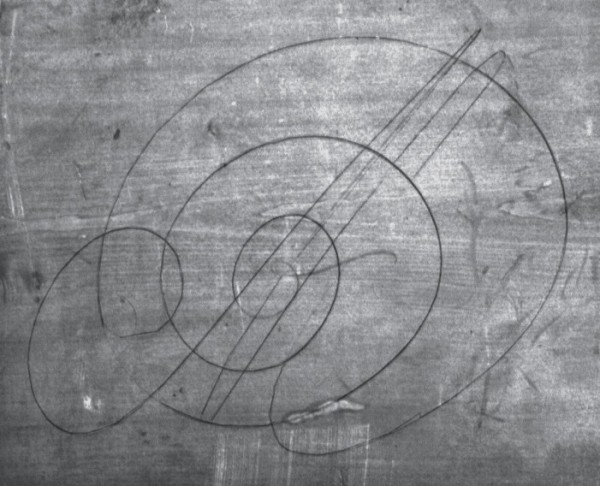

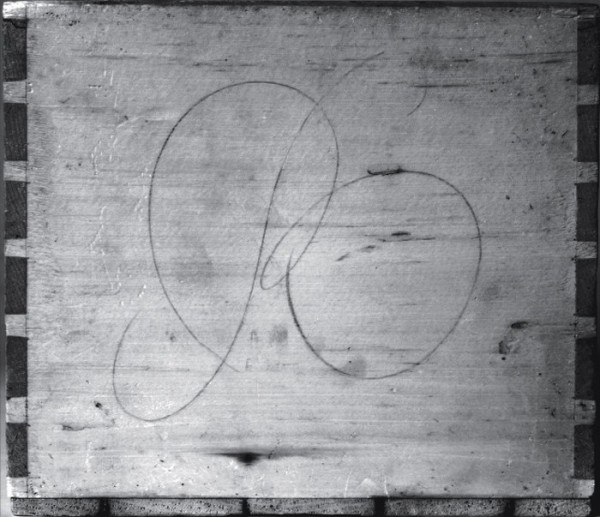

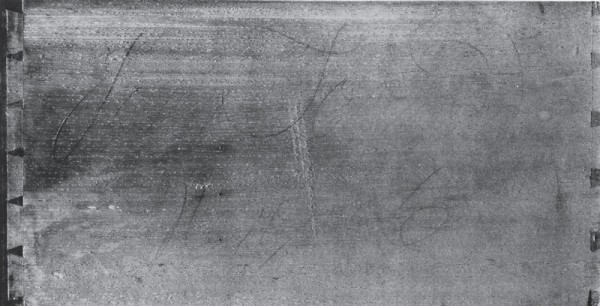

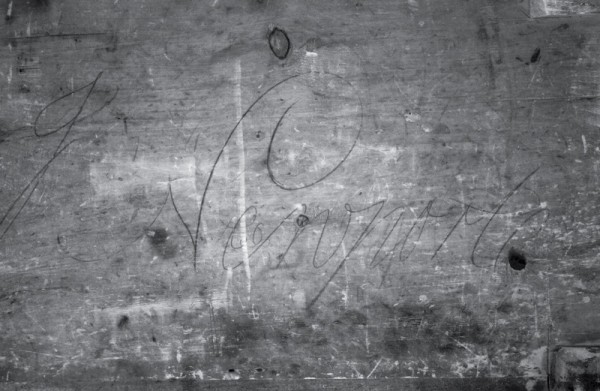

Detail of an “M” finishing mark on the backboard of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

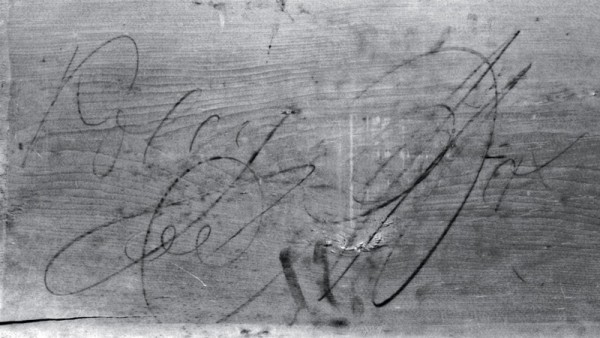

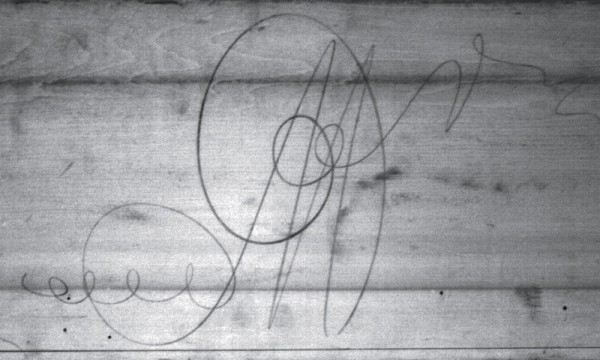

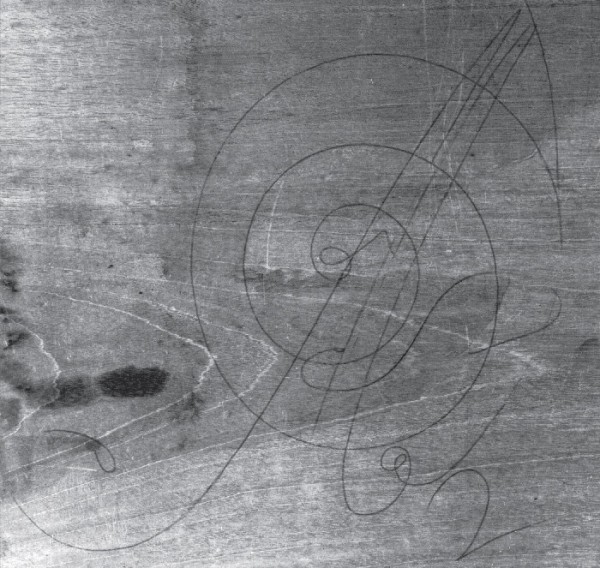

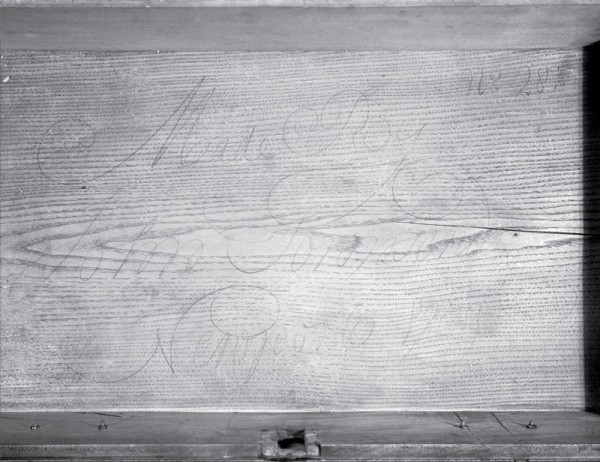

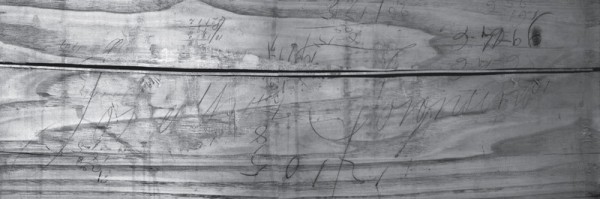

Detail of the lettering on the backs of the upper-case drawers of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1 (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Detail of the lettering on the backs of the lower-case drawers of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

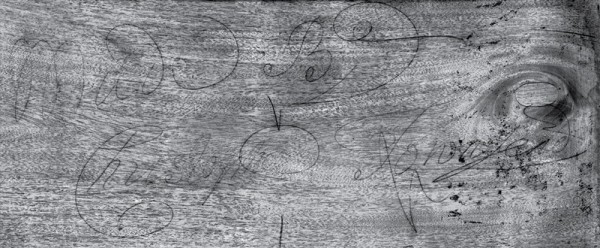

Detail of the inscription “Polly” on the bottom of a drawer in the upper case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

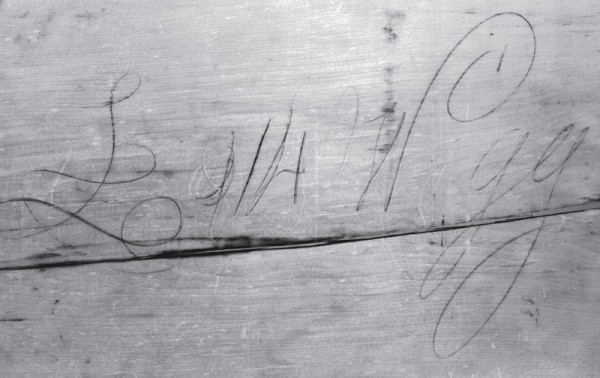

Detail of the inscription “£14 Wigg” on the bottom of a drawer in the upper case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Detail of the inscription “W Richardson/J Robinson/E Wanton/J Townsend/to Ride out next Wednesday” on the upper left drawer of the upper case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Detail of the inscription “Woman Is By/Nature False & Inconstan(t)/W[ ]fill/W Richardson” and letter “A” on the upper left drawer of the upper case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Detail of the leg and foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the shell on the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The shell is applied and the lobes are carved through into the skirt below. The joint is visible near the bottom of the shell.

Detail showing the lamination line of the shell and skirt of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1750–1765. Mahogany with red cedar. H. 30", W. 50", D. 25". (Courtesy, Redwood Library and Athenaeum, Newport, Rhode Island; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are similar to those on furniture documented and attributed to John Goddard. This table has been extensively reworked. The drawers are later additions, and the original top was probably marble.

Dressing table, Stonington area, Connecticut, ca. 1765. Maple. H. 27 1/2", W. 31 3/4", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

High chest of drawers attributed to Christopher Townsend and John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 92 1/4", W. 44 1/4", D. 22 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The horizontal moldings at the base of the finial plinth are missing, but the chest retains its original hardware.

Detail of the leg and foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the shell on the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the pediment backboard of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The upper portion of central plinth is lost.

Detail showing the pediment backboard of the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the glue blocks securing the left front leg of the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the glue blocks securing the left front leg of the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the glue block attached to the skirt and a vertical drawer divider on the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the glue block attached to the skirt and a vertical drawer divider on the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the board behind the oculi of the pediment of the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

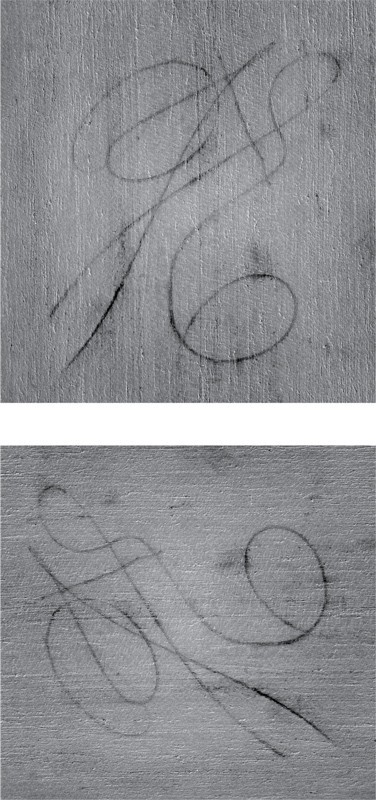

Detail of an “M” finishing mark on the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Erik Gronning.) John Townsend may have inscribed this finishing mark.

Detail of an “M” finishing mark on the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Erik Gronning.) Christopher Townsend may have inscribed this finishing mark.

Detail of the “B” inscribed on the high chest illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Erik Gronning.) The belly of the “B” is not nearly as exaggerated as that shown in fig. 29.

Detail of the “B” inscribed on the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Christopher Townsend, desk-and-bookcase, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany throughout. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.) The brackets are original, but the ball feet below are conjectural replacements. As is the case with the Arnold and Wanton high chests (figs. 19, 20), the upper backboard of the Appleton bookcase is shaped to mirror the tympanum.

Detail of an “M” finishing mark on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s).

Detail of the inscription “Made By Christopher Townsend” on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Charlotte Hale, Sherman Fairchild Paintings Conservation Center, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the cornice molding and left finial of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the finial on the high chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.) The softer, more elliptical shape of the flame is unique in John Townsend’s work. The lowermost section of the finial is restored and would originally have been shorter, like the finial shown in fig. 33.

Detail of the silver mount on the left fallboard support of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.) The eyes are made from a cylinder of agate.

Detail showing the foot blocking on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Leslie Keno.) The glue blocks are neatly finished to conform to the shape of the brackets.

Desk-and-bookcase, England, 1700–1720. Oak with pine. H. 81 1/8", W. 43 7/8", D. 23 1/2". (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of James De Lancey Verplanck and John Bayard Rogers Verplanck, 1939 [39.184a,b]. Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Christopher Townsend, desk, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany with mahogany, cedrela, and tulip poplar. H. 37 1/4", W. 35 5/8", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lower portions of the feet are missing, but the desk has its original brass, hardware, and finish.

Detail showing the foot blocking of the desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a shell on an interior drawer of the desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inscription “Made by C T” on the bottom of desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of a chalk finishing mark on the back of an exterior drawer of the desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Details showing the letters on the backs of the exterior drawers of the desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Desk attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany with tulip poplar, chestnut, cedrela, and white pine. H. 42", W. 36 1/2", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the brass mount on the left fallboard support of the desk illustrated in fig. 44. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.) The eyes are made from a cylinder of agate.

Details of the inscription on the back of an exterior drawer of the desk illustrated in fig. 44. (Photo, Erik Gronning.) The upper image shows the orientation of the board when the inscription was made prior to assembly. The lower image is as it appears with the grain oriented horizontally.

Desk attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Cedar. H. 41 1/4", W. 35 7/8", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Caxambas Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Christopher Townsend and John Townsend, high chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany with yellow poplar, chestnut, white pine, and mahogany. H. 87 13/16", W. 40 1/2", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chest retains its original hardware.

Detail showing the “John T” and “Christopher Townsend” inscriptions on the lower-case drawer blade of the high chest illustrated in fig. 48.

Detail of a leg and foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the shell on the high chest illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a piece of molding used in the construction of the pediment of the high chest illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

John Townsend, dining table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1756. Mahogany with soft maple, red oak, and hickory. H. 28 3/4", W (open). 62 1/4", W (closed). 17 1/2", D. 58 1/4". (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Stuart Holzer and Marc Holzer, in memory of their parents, Ann and Philip Holzer, 2012. Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

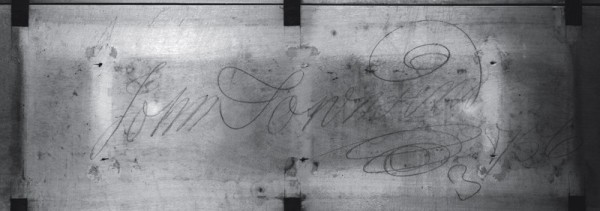

Detail of the inscription “ John Townsend 1756/3,” on the dining table illustrated in fig. 53. (Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of a leg and foot of the dining table illustrated in fig. 53. (Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.) The central talon on the foot is replaced.

Detail of the inscription “For Israel / A” on the dining table illustrated in fig. 53. (Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Dining table attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany. H. 30 1/2", W (open). 69", D. 62". (Antiques 110, no. 98 [September 1970]: 292.)

Christopher Townsend, tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany. H. 25 3/4", W. 21 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Detail of the inscription “C Townsend joynd the piece” on the tea table illustrated in fig. 58. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Tea table attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1760. Mahogany. H. 26 1/4", W. 19 5/16", D. 19 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence; photo, Erik Gould.)

Christopher Townsend, high chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, 1748. Walnut with white pine. H. 70", W. 38 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (© 2013. Collection of Gerald and Kathleen Peters; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

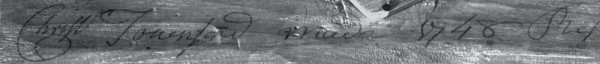

Detail of the inscription “Christopher Townsend made 1748” on the high chest illustrated in fig. 61. (Photo, Charlotte Hale, Sherman Fairchild Paintings Conservation Center. Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

High chest of drawers attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany with white pine and yellow poplar. H. 72", W. 39", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Israel Sack, Inc., Archive, Yale University Art Gallery.) This high chest was originally made for George Hussey (d. 1782) of Nantucket, Massachusetts.

Detail of the “M” finishing mark on the high chest illustrated in fig. 63. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

High chest of drawers attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany with white pine and yellow poplar. H. 83 5/8", W. 40 1/2", D. 22 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chest retains its original cast brass hardware and finish. Made in three sections and secured with glue blocks, the china shelves are inscribed twice with a chalk “A.” As is the case with other flat-top high chests documented and attributed to Christopher Townsend, the rear legs are glued into a shallow rabbet in the backboard.

Detail of a claw-and-ball foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 65. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bureau table with legs attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1760. Mahogany with chestnut and tulip poplar. H. 27", W. 40 1/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.) The case has fine dovetails and a deep shell carving consistent with furniture from John Townsend’s shop, but owing to alterations, only the legs and feet can be attributed to him. This object may have started out as a pier table or side table.

Detail of a leg and foot of the bureau table illustrated in fig. 67. The side and front talons are replaced.

Tea table attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1760. Mahogany with chestnut. H. 26", W. 33 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg.) The table has a chestnut cross-brace dovetailed at the midpoint of the long rails and a top secured with glue blocks. The knee returns are replaced.

Detail of a leg and foot of the tea table illustrated in fig. 69.

Tea table attributed to Christopher or John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1760. Mahogany. H. 25", W. 33 3/4", D. 21 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Michael J. Smith.) The second phalange on the toes is slightly more elongated than those on the Arnold high chest. This is the only marble-top Newport tea table known, but its design and size are consistent with the Sweet and Weeden tables.

Detail of a leg and foot of the tea table illustrated in fig. 71. (Photo, Michael J. Smith.)

Dressing table attributed to Christopher or John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany with white pine, yellow poplar, chestnut, and mahogany. H. 31", W. 35 3/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg.)

Detail of a leg and foot of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 73.

Detail of the shell of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 73.

John Townsend, high chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, 1759. Mahogany with chestnut, eastern white pine, and cottonwood. H. 88 3/4", W. 39 3/8", D. 22 1/8". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, bequest of Doris M. Brixey.) Christopher Townsend may also have used the fleur-de-lis broken motif seen on the shell of this chest. A mahogany high chest base with that feature has ball-and-claw feet remarkably similar to those made by Christopher (CRN Auctions, Americana and English Antiques, American and European Works of Art, Chinese, and Jewelry, Cambridge, Massachusetts, September 9, 2012, lot 107).

Detail of the inscription “No. 28 / Made By / John Townsend / Newport / 1759” on the high chest illustrated in fig. 76.

Detail of a leg and foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 76.

Detail of a foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 76. A space can be seen above the ball.

John Townsend, document cabinet, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany. H. 27 1/2", W. 25 3/4", D. 12 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.) The cabinet has Townsend’s drawer lettering system. The backs of the drawers are inscribed in graphite “A,” “B,” “C,” “D,” from top to bottom on the right, and “E,” “F,” “G,” and “H,” from top to bottom on the left. Townsend used book-matched pieces of wood for drawers A and E, consecutive pieces cut from the same log for drawers B and D, and contiguous pieces from the same flitch for drawers G and H.

Detail of the inscription “John Townsend / Newport” on the document cabinet illustrated in fig. 80. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the shell on the door of the cabinet illustrated in fig. 80. (Photo, Christie’s.)

Chest of drawers attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1756. Mahogany with eastern white pine and yellow poplar. H. 38 1/8", W. 38 1/2", D. 20 1/8". (Courtesy, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C.) The chest retains its original hardware, but the bottom 3 1/2 inches of the feet are replaced. The top drawer is secured with a spring lock that is reached by opening the drawer below.

Detail showing the two-piece construction of the shell on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 83. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of the inscription “Moses” on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 83. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Slant-front desk attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany. H. 42", W. 37", D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.) The desk retains its original hardware, but the feet are replacements.

Detail of the partial inscription “J [ ] Newport” on the desk illustrated in fig. 86. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of the inscription “James Harden” on the desk illustrated in fig. 86. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

High chest of drawers attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1757. Mahogany with mahogany and white pine. H. 87", W. 40 3/4", D. 22". (Photo, 2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.) The construction of this high chest is consistent with John Townsend’s early work, but the backboard of the pediment has a semicircular cutout rather than shaping that matches the tympanum. All of the drawer fronts were veneered at a later date.

Card table attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1760. Mahogany with maple and white pine. H. 27 1/2", W. 35 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.) This table descended in the family of Stephen Hopkins (1707–1785), who was a governor of Rhode Island and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Detail of the knee carving on the high chest illustrated in fig. 89. (Photo, 2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Jonathan Townsend, block-and-shell bureau table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1767. Mahogany. H. 32 1/2", W. 36 1/2", D. 20". (Courtesy, Christie’s Images Limited 2013.) Jonathan Townsend was twelve years younger than his brother John.

Detail showing the graphite signature on the bureau table illustrated in fig. 92. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

John Townsend, card table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1762. Mahogany with chestnut, maple, and white pine. H. 27 1/4", W. 35", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, 63rd Street Equities; Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail showing the graphite signature on the card table illustrated in fig. 94. (Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the knee carving on the card table illustrated in fig. 94. (Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

John Townsend (1733–1809), born in Newport, Rhode Island, on February 17, 1733, was the first son of Christopher Townsend (1701–1787) and his wife, Patience Easton (1703–1789), and is accepted by many as one of America’s greatest cabinetmakers. John Townsend’s work has been studied at length by many scholars. Among the most comprehensive publications was Morrison H. Heckscher’s John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker (2005). The exhibition that accompanied that book assembled for the first time nearly all of the known works by Townsend. Therefore, it was with great surprise that in March 2011 an unknown signed and dated John Townsend high chest was discovered (fig. 1). Researching the high chest initiated a string of discoveries not only about John Townsend but also about his apprenticeship with his father.[1]

Christopher Townsend, the son of Solomon and Catherine Townsend, was born in Oyster Bay, Long Island, and arrived in Newport with his family in 1707. Between 1715 and 1722 Christopher trained as a joiner and cabinetmaker with an unknown Newport master. In December 1723 he married and settled on Easton’s Point, where his wife’s family had significant landholdings and ties in the furniture, shipbuilding, and house building trades. In 1725 Christopher purchased lot 51 in Newport for his house and shop, which still stand today at 74 Bridge Street.[2]

Christopher began his career during the 1720s working as a house carpenter or housewright. He described himself as a “joiner” or “shop joiner” and likely built his own house and shop (the latter measuring 12 by 20 feet), which was located down the street from the house of his older brother, Job Townsend (1699–1765). In 1729 he became a freeman and received commissions for a number of public and private buildings in Newport, including the Colony House (1739–1749) and perhaps Trinity Church (1725–1735), as well as the Seventh Day Baptist Meeting House (1725–1730). He may have established his cabinet shop by 1732, when he purchased hardware, nails, and other materials. Two years later, a local merchant sold him a large quantity of hardware for case furniture, including desks.

Christopher’s shop supplied furniture to several important local merchants, including Abraham Redwood and Isaac Stelle. The workshop was spacious enough for five or six workbenches, which were manned by his sons, John and Jonathan (1745–1773), whom Christopher trained, as well as other apprentices and journeymen. Christopher’s working career spanned nearly sixty years, during which time he amassed an estate larger than those of anyone else in his extended family, owing in part to his wife’s assets.[3]

John Townsend’s life paralleled his father’s in many ways over his nearly fifty-year career. John probably began his apprenticeship in 1747 and completed his term during the mid-1750s. He described himself as a “joiner” in a contract with the house carpenters Henry Peckham and Wing Spooner in 1754, but at that time he may still have been working in Christopher’s shop.[4]

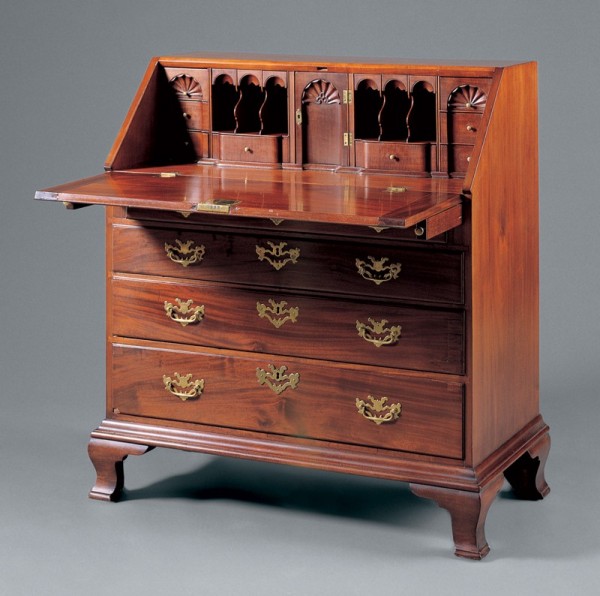

The high chest illustrated in figure 1 is the earliest example of that form documented to John Townsend. It does not have his archetypal front legs with flat incised carving; sharp, angular, anisodactyl claw feet; rear legs with pad feet; or conventional concave shell (fig. 2). Rather, this chest has four delicate unadorned legs, each supported with open-talon claw-and-ball feet, and an obverse convex shell, oriented with the lobes extending down. If not for its prominent signature, this object might never have been ascribed to John Townsend. Dated 1756, the chest may have been the first major commission he received. The original owners, Lieutenant Colonel Oliver Arnold (1725–1789) and his wife Mary (1725–1762), were married in that year, and their choice of John Townsend to make the chest attests to the latter’s elevated status within Newport’s cabinetmaking community at the young age of twenty-three.[5]

The importance that Townsend placed on the Arnold chest is evident from the profuse graphite inscriptions he placed on it. “Made By John Townsend / Newport 1756” (fig. 3) is written on the inside of the top drawer of the lower case, “John Townsend” is penciled on the upper-case drawer divider, and the letter “M”—matching that in the word “Made” and used as a finishing mark—is written on different components at least five times (fig. 4). Large calligraphic finishing marks are characteristic of Townsend’s work and consistently appear on other examples of his furniture. On the Arnold chest, he used the letters “A,” “B,” “C,” “D,” “E,” and “F” to differentiate the drawers of the upper case. The drawers of the lower case are also inscribed: “A” on the back of the upper drawer, “B” on the back of the center drawer below, and “A” and “B” on the backs and sides of the flanking drawers. In addition, letters occur on several drawer dividers and drawer sides (figs. 5, 6).[6]

Townsend wrote the name “Polly” and “£14 Wigg” on the bottoms of two drawers of the upper case (figs. 7, 8). The first inscription is likely a reference to Mrs. Arnold, since “Polly” was a common nickname for Mary in the eighteenth century. The second inscription corresponds to the price of a wig in Newport in the 1750s, when it was common practice to spell the word with two g’s. Writing of a somewhat personal nature is also present on the chest but is otherwise unknown in John Townsend’s work. The upper left drawer of the upper case is inscribed “W Richardson / J Robinson / E Wanton / J Townsend / To Ride out next Wednesday” (fig. 9). This writing refers to William Richardson, Joseph Robinson, Edward Wanton, and John Townsend and probably to the day the chest was to be delivered. All four men were from elite Quaker families, who lived near one another on Easton’s Point in Newport and were variously connected through business and marriages.[7]

William Richardson (1736–1769) was the son of Thomas Richardson (1680–1761), a Newport merchant, general treasurer of Rhode Island (1748–1761), and presiding clerk of the New England Yearly Meeting of Friends (1729–1760), and his wife, Mary Wanton (1700–1777), who married in 1729. Mary Wanton’s brother Gideon (1693–1767) served as governor in 1745 and 1747. William Richardson and Joseph Robinson were partners in Thomas Robinson & Co., one of the leading mercantile businesses in Newport. Richardson was Thomas Robinson’s (1731–1817) brother-in-law and was undoubtedly related to Joseph. On November 5, 1761, all three men represented their firm in an agreement to manufacture spermaceti candles with Obadiah Brown & Co., Richard Cranch & Co., Naph Hart & Co., Isaac Stelle & Co., Aaron Lopez & Co, Collins & Rivera, and Edward Langdon & Son. Captain Edward Wanton (1734–1773) was the son of Governor Gideon Wanton (1693–1767) and Mary Cadman (d. 1780) and a cousin of William Richardson. Born on April 12, 1734, Edward was described as a merchant in several Newport court cases. His brother Gideon Jr. (b. 1724) married John Townsend’s sister Mary (1735–1783).[8]

The upper left drawer of the Arnold chest bears the inscription “Woman Is By / Nature False & Inconstan(t) / W[ ]fill / W. Richardson” (fig. 10), a playful commentary on marriage that reinforces the theory that the chest was made around the time of Oliver and Mary Arnold’s wedding. The first part of the inscription was inspired by a quote in The Orphan; or, the Unhappy Marriage, a play written by Thomas Otway (1652–1685) in England in 1680. A story of unrequited love, the play was one of the most influential domestic tragedies of the seventeenth century, and it remained popular in English and American theaters well into the nineteenth century. The larger quote that inspired Townsend’s quip was excerpted from the play and published widely. It appeared in an essay on marriage written by Joseph Addison (1672–1719) for the Spectator in 1711. Reissued in eight volumes in 1747, the Spectator was available for circulation at the Redwood Library, which was founded in Newport in that year. The Townsends, Wantons, Robinsons, and Richardsons were among the library’s first members.[9]

The Arnold high chest is the earliest dated Rhode Island example with an ogee head. Although the pediment has fully developed features that became standard in Newport work from 1760 to 1780—an enclosed ogee pediment with two moderately sized oculi and two applied tympanum panels—it was made just when the flat-top form that had been popular for the previous fifty years was passing out of fashion for all but the least expensive chests. The absence of quarter columns on the upper case and carving on the knees and presence of four pierced claw-and-ball feet and a downward oriented convex shell provide further evidence that the Arnold chest represents a transitional phase in Newport high chest design.

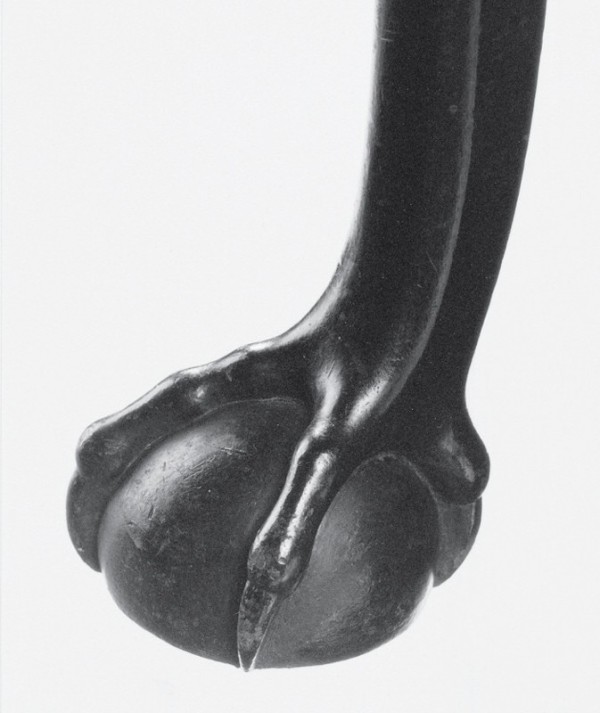

The Arnold chest is also unusual in having four claw-and-ball feet (most later Newport examples have turned pad feet at the rear) and is the earliest dated example with pierced talons (fig. 11). Although not verified through microscopy, the balls have a dark finish that may have been intended to simulate ebony and contrast with the lighter, more transparent finish of the anisodactyl claws. The claws have rounded knuckles and are thinner and less angular than those on later feet from Townsend’s shop. Characteristic of all the claw-and-ball feet on his furniture, the hallux or rear talon has no knuckle. This sets his work apart from feet on furniture documented and attributed to John Goddard, which have a well-defined, rounded knuckle on the rear talon.[10]

Of all the features of the Arnold chest, the shell is perhaps the most distinctive (fig. 12). Unlike most of the shells on later Newport high chests and dressing tables, which are somewhat semicircular in shape and oriented with the lobes facing up, the shell on the Arnold chest is fan-shaped and oriented in the opposite direction. The carver of the Arnold chest began by transferring the design of the shell to a 1/2-inch-thick mahogany board, cutting the rough outline with a bow saw, and partially carving the outermost convex lobes. After gluing the board to the skirt, he completed the carving with gouges (used right side up to cut the flutes and upside down to model the convex surfaces), a parting tool (used to establish the fillets between the convex and concave lobes), and abrasive (used to remove tool marks from the convex lobes). The glue line is visible where the carver cut through the laminate into the skirt below (fig. 13). Only two other pieces are known with this type of shell: a pier table with ball-and-claw feet and a high chest (figs. 14, 16).

This unique shell design may have influenced cabinetmakers working in and around nearby Stonington, Connecticut. Several objects from this region, including a high chest of drawers with a history of descent in the Smith and Hyde families and a dressing table, have skirts with integral “drops” having the same basic outline as this early Newport shell (figs. 1, 12, 15). Decorative arts scholars Minor Myers Jr. and Edgar Mayhew attributed the Smith high chest to a member of that family and suggested as a candidate Jonathan Smith, who was working in Stonington during the second half of the eighteenth century.[11]

Although Rhode Island designs were undoubtedly transmitted to other coastal New England towns, the most diagnostic construction techniques employed by John Townsend and his Newport contemporaries were rarely imitated. As exemplified by the work on the Arnold chest, Townsend’s drawer dovetails are fine and evenly spaced, and the top of each drawer side is finished with a shallow torus molding. Each of the three short drawers of the upper case is secured with a wooden spring lock (often referred to as a “Quaker” lock) rather than a conventional metal lock. Otherwise, Townsend would have had to place the escutcheon plate too high on the drawer face and disturb the chest’s proportions. The mahogany he chose was very dense and highly figured, ranging from a striped pattern on the drawer fronts to a curled pattern for the cornice moldings and shell laminate. Most of the secondary wood in the chest is clear white pine, including the vertical glue blocks used to secure the legs to the inner corners of the lower case frame, which reinforce the area where the partitions between the lower drawers join the skirt and stop the drawers. As is the case with other furniture documented and attributed to John Townsend, the Arnold chest has a small amount of mahogany secondary wood. The glue blocks securing the front legs to the skirt are made of that wood and chamfered to remain hidden from view. Collectively, these construction and design characteristics are hallmarks of Townsend’s work and crucial in identifying other early pieces.

The high chest illustrated in figure 16 was probably made circa 1755. Notations on a piece of parchment glued to a drawer side state that the chest was originally owned by Governor Gideon Wanton and bought at auction following his death by Perry Weaver, John Goddard’s son-in-law. The chest descended in the Freeborn branch of the Weaver family until its acquisition by the current owners. Although significantly larger than the Arnold high chest, the Wanton example is similar in having plain knees, claw-and-ball feet at the front and back, and a downward-oriented convex shell. It also has the same drawer lettering system and related “M” finishing marks on the backboard.[12]

The carving on the Wanton chest differs from that on the Arnold example. The feet have compressed balls, larger toes with subtly modeled knuckles, and talons that are not pierced (fig. 17). Although conventional in design, the feet of the Wanton chest are superior in execution to those on much Newport furniture. The shell on the Wanton chest is less complex than that on the Arnold example (fig. 18), but it is glued up in the same manner. On both shells, the carver cut through the laminate into the skirt below.

The Arnold and Wanton high chests share several construction features: the backboards of the heads are cut to mirror the oculi and plinths of the tympana (figs. 19, 20); the cyma-shaped cornice moldings are attached with interior screws; mahogany glue blocks are used to secure the front legs to the skirt (figs. 21, 22); and the glue blocks reinforcing the joint between the vertical dividers of the lower drawers terminate in chamfered points (figs. 23, 24). Variations in the construction of these pieces are largely a factor of design. The pediment of the Wanton high chest has a mahogany board behind the oculi and moldings around them (fig. 16). The board is dadoed and wedged into the cornice returns and front-to-rear framing boards below (fig. 25). The plinth of the tympanum originally had a base molding, but the latter is missing. Ogee heads that are fully enclosed at the front are relatively common on Newport case pieces, but the unusual attachment of the board behind the oculi of the Wanton chest suggests that it was an early attempt to achieve that design.[13]

The design and construction of these chests suggest that they were made in the same shop. This relationship becomes even more apparent when the marks on the objects are compared under infrared light. The Wanton high chest has letter designations, but it is inscribed with an “M” finishing mark seven times. The “M” marks are by two different hands; one begins with a distinctive triple loop (fig. 26) and is nearly identical to the “M” marks on the Arnold high chest (fig. 4), while the other lacks the loops and has a concentric spiral (fig. 27). The letter “B” on the Wanton chest also differs from that on the Arnold example (figs. 28, 29). Inscriptions on a desk-and-bookcase signed by Christopher Townsend and made for the Reverend Nathaniel Appleton (1693–1784) and his wife, Margaret (Gibbs) (1699–1771), of Cambridge, Massachusetts, offer an explanation for the similarities and differences observed in the marks on the Wanton and Appleton high chests (fig. 30). The “M” finishing marks on the backboards of the desk-and-bookcase and the Wanton high chest are nearly identical (figs. 27, 31). Moreover, the calligraphic “B” on the Wanton high chest is identical to the “B” in the inscription “Made By Christopher Townsend” (figs. 28, 32). Therefore, one may surmise that Christopher Townsend and his son John collaborated in the production of the Wanton high chest.

The Appleton desk-and-bookcase has “plum-pudding” mahogany primary wood and solid silver hardware made by Newport silversmith Samuel Casey (1723–ca. 1773). It retains its original urn-and-flame finials, which are similar to the one John Townsend made for the Arnold high chest (figs. 33, 34). Imported British case furniture or architectural design books may have influenced Christopher’s or his client’s choice of an arched pediment, since only one other Newport case piece with that type of head is known. The desk-and-bookcase is also unusual in having fallboard supports faced with silver birds with inlaid agate eyes (fig. 35). Christopher Townsend appears to have favored this motif, since he used birds with a similar profile on the staircase frieze in his house on Bridge Street in Newport. Another distinctive feature of the Appleton desk-and-bookcase may have been lost. The writing height of the fallboard is relatively low, which suggests that the feet are not full height. Inside each bracket are two mahogany glue blocks that abut to form a square hole (fig. 36). If the Appleton desk-and-bookcase followed the design of elevated English baroque examples, a compressed ball foot with a square tenon may have fit into the holes (fig. 37).[14]

A recently discovered slant-front desk with a history of descent in the Simon Pease family of Newport shares details with the Appleton desk-and-bookcase; the brasses are aligned vertically, the interior design and foot construction are similar, and the shells on the small drawers are virtually identical (figs. 38-40). The bottom board of the desk is signed “Made by C T,” and the backsides of the exterior drawers are inscribed with a chalk finishing mark (figs. 41, 42). The three large drawers are also marked sequentially in graphite, “B,” “C,” and “D” (fig. 43).[15]

A related slant-front desk with brass lopers identical in shape and size to those on the Appleton desk-and-bookcase has graphite letters inscribed on the back of the exterior drawers in Christopher Townsend’s hand (figs. 44-46). The other notable differences include a more detailed prospect door shell and intricate sliding wooden locks securing the uppermost exterior drawer. The current feet are replacements and may possibly have originally been of the two-part form found on the desks in figures 30 and 38. On one interior drawer is a graphite mark (fig. 46). A similar mark was found on a drawer of the Wanton high chest.[16]

Another slant-front desk possibly made for the export market has details suggesting that it originated in Christopher Townsend’s shop (fig. 47). Made of cedar, this object has an “M” finishing mark similar to those on other pieces documented and attributed to him as well as drawer backs with Christopher’s script lettering system. Moreover, the precisely rendered dovetails, rounded edges of the drawer sides, and chamfered top edges of the drawer backs are consistent with his work. Christopher Townsend is documented as having made several cedar desks for export over the course of his career, including “2 Cedar Desks, and Casing” in 1748. John Banister paid him £83. 12. 6. for those pieces, which were shipped on the sloop Little Polly bound for Jamaica. In 1764 Captain Peleg Bunker purchased a red cedar desk from Townsend and agreed to make payment after returning from the West Indies.[17]

The high chest of drawers illustrated in figure 48 represents another collaborative effort between Christopher and John Townsend; it is inscribed in graphite on the lower-case drawer blade “John T” and “Christopher Townsend” (figs. 48, 49). The chest has a history of descent in the Smith family of Philadelphia, but an original brass lock escutcheon engraved in period script “Thos. Robinson” suggests that the original owners were Thomas (1731–1817) and Sarah (Richardson) Robinson, who married in Newport in 1752. The shaped pediment backboard, glue blocks, molding profiles, upper drawer Quaker locks, cabriole legs, and feet are very similar to those on the Arnold high chest (figs. 11, 50). The graphite lettering of the drawers and “M” finishing marks on the back of the upper and lower cases of those objects are also identical. Were it not for the concave shell (fig. 51) and inscription, this high chest would almost certainly be ascribed to John Townsend alone. The chest is unique in having bonnet dust boards made of mahogany. These boards may represent the use of leftover wood, rather than a material option, since a section of scrap molding was used as a brace on the interior of the pediment (fig. 52).[18]

Made the same year as the Arnold high chest is a dining table inscribed “John Townsend 1756/3,” “ John Towns[en]d” and “John” (figs. 53, 54). The table’s tall cabriole legs terminate in claw-and-ball feet that are identical to those on the Arnold chest (figs. 11, 55). As he did on that high chest, Townsend inscribed the table with the owner’s name—“For Israel / A” (fig. 56). A similar undated table may be an antecedent for the signed example (fig. 57). Likely made in the shop of Christopher Townsend, it has his characteristic feet, which are similar to John’s but distinguished by having thicker toes and much shorter talons.[19]

Rectangular tea tables with angular cabriole legs, slipper feet, ovolo rail moldings, and tray tops rabbeted on the underside to fit inside the frame are generic Newport forms that were likely made by members of both the Townsend and Goddard families. The example illustrated in figure 58 is unusual in being signed in chalk on the underside of the top: “C Townsend joynd the piece” (fig. 59). Given the similarities in their construction of case furniture, it is not surprising that John Townsend’s version of this slipper-foot form is virtually identical to Christopher’s.[20]

John Townsend also offered claw-and-ball feet as an option on this standardized tea table form. With a history of descent in the Sweet or Abbott family of Rhode Island, the example illustrated in figure 60 has feet that are identical to those on the Arnold chest. Other than having the underside of the top notched in the corners, its construction is the same as that of other Newport tea tables including the one signed by his father (fig. 59).[21]

Christopher Townsend’s earliest known work is a flat-top high chest of drawers that is signed and dated in graphite on the bottom board of the upper case, “Christopher Townsend made 1748” (figs. 61, 62). According to a paper label on the chest, the original owner was Newport ship captain William Van Deursen, who, during the Revolution, lived in Middletown, Connecticut, where he commanded the privateer brig Middletown. With its dovetailed lower case, legs secured with glue blocks inside the frame, and cyma-shaped skirt, the Van Deursen chest shows that Newport case design and construction became standardized very early, which gave the city’s cabinetmakers an advantage in the coastal furniture trade.[22]

A very similar high chest can be attributed to Christopher Townsend based on its graphite inscriptions (fig. 63). The original owner was George Hussey (d. 1782) of Nantucket, Massachusetts. At his death the chest passed to Clothier Pierce Sr., a merchant in Newport, and next through the Potter family of Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Though not signed, the high chest has Christopher Townsend’s large calligraphic finishing mark “M” in graphite on the interior bottom of the lowest long drawer of the upper case, as well as his signature lettering system (fig. 64). Its drawer arrangement differs slightly from the signed example but is the same as that of the Arnold and Robinson high chests. As with the Wanton high chest, the sides of the lower case are rabbeted to receive the squares of the legs (figs. 1, 48).[23]

A high chest of drawers with china shelves backed by an elaborately scalloped board is the most architecturally elaborate example of the Newport flat-top form (fig. 65). Originally owned by Rhode Island Governor Samuel Ward (1725–1776), the chest can be attributed to Christopher Townsend’s shop based on structural and stylistic affinities with the Van Deursen and Hussey high chests. The distinctive claw-and-ball feet, with thicker elongated phalanxes and flattened balls, relate closely to those of the Wanton high chest (figs. 17, 66). The balls also appear to be ebonized like those of the Arnold and Ward high chest (figs. 11, 66) and of a heavily altered table that descended in the Schuyler and Van Rensselaer families of New York (figs. 67, 68). The original owner of the table may have been Philip Schuyler, who married Catherine Van Rensselaer in 1755.[24]

In the Townsend shop tradition, claw-and-ball feet with pierced talons occur on furniture documented and attributed to both Christopher and John. In some instances, their work is relatively easy to separate. The feet on a tea table that reputedly descended in the Weeden family of Jamestown, Rhode Island, are related to those on the Wanton chest in that the second phalanges of the side toes are more elongated than that of the center toe (figs. 69, 70, 17). This design and carving feature is more closely associated with Christopher than with John. In contrast, the feet on a marble-top tea table from the Rodman family of Rhode Island could be ascribed to either maker (figs. 71, 72).[25]

A dressing table with a history in the Chase family of Rhode Island has legs and feet that are closely related to those of the Rodman table (figs. 73, 74). The elongated second phalanges on the side toes and the shorter pierced talons of the feet follow the design associated with Christopher Townsend, and the graphite letters on the backs of the drawers and spiral finishing marks also appear to be in his hand. The balls also appear to be ebonized like those on the Arnold and Ward high chests and altered Van Rensselaer table (figs. 11, 66, 68, 74). As is typical of early high chests and dressing tables associated with Christopher and John Townsend, the front legs of the Chase table are secured with contoured mahogany glue blocks, and the rear legs with rectangular white pine glue blocks, the latter notched to act as drawer stops. The glue blocks on the inside of the skirt are shaped in the same manner as those of the Arnold and Wanton high chests (figs. 21–24). Other early features can be observed in the design and execution of the carved shell, most notably the way it is contained within an arch and its open center (fig. 75). The Robinson high chest has a related shell, but the center is not cut out (fig. 51).[26]

Several early Newport case pieces have shells with a hollowed lobe extending up between opposing scroll volutes, a motif some Newport furniture scholars have interpreted as a stylized fleur-de-lis. A high chest of drawers with this detail is inscribed on the top long drawer of the upper case, “No. 28 / Made By / John Townsend / Newport / 1759” (figs. 76, 77). The piece has “signature” attributes of John’s shop, including his florid lettering system on the backs of the drawers. Like other objects documented and attributed to him, it is well made and highly finished. The inner edge of the skirt shell is chamfered, the drawer sides have a torus molding at the top, glue blocks are contoured where required, and wooden spring locks secure the small upper drawers. Although made only three years after the Arnold chest, the Brixey example is designed quite differently. On the latter, tympanum panels are smaller, the oculi are larger, two equal-size drawers are in the upper row, the knees are carved, the rear legs end in pad feet, and the feet are pierced above the ball (figs. 78, 79). Indeed, the Brixey chest is the earliest documented example from Townsend’s shop with those features.[27]

The most atypical object associated with John Townsend earliest period is a document cabinet with three shells, each with his characteristic fleur-de-lis (fig. 80). Inscribed in graphite “John Townsend/Newport” on the right side of the lower left drawer, the cabinet is one of the earliest block-and-shell case pieces made by him (fig. 81). The shelves and dividers in the interior have scalloped edges similar to those in the Appleton desk-and-bookcase, and the door shell, confined within an arch, continues a design likely introduced by Christopher Townsend (figs. 30, 82). The shells are taller than those on John Townsend’s later block-and-shell pieces. One of the most unusual aspects of the cabinet’s design is its compressed ball feet. Both their use and the possible incorporation of ball feet on the Appleton desk-and-bookcase and desk illustrated in figure 30 attest to the continued influence of baroque design on John Townsend’s early work.[28]

A chest of drawers with a history in the Milnor family of Woodstock, Connecticut, can be attributed to John Townsend based on its carved shells and graphite inscriptions (fig. 83). Aside from being larger, the shells are almost identical to those on the document cabinet. On both objects, the applied convex shells were made in two pieces, a lobed section and a blocking section below (fig. 84). The back of each drawer is inscribed with graphite letters in John Townsend’s distinctive hand, and the top drawer has his characteristic “M” finishing mark. As is the case with several other examples of his work, the chest also bears the owner’s name, “Moses,” written in graphite (fig. 85).[29]

The desk illustrated in figure 86 is the only slant-front example having a shell with the stylized fleur-de-lis motif. It retains a partially legible graphite signature, “J [ ] Newport,” on the bottom board and has the name “James Harden”—likely an owner or journeyman—inscribed in Townsend’s hand (figs. 87, 88). Its interior is similar to the Appleton desk-and-bookcase, but its more elaborate pigeonhole dividers are finished with scalloped sides similar to those found on the interior dividers of the document cabinet.[30]

A high chest that descended in the Potter family of Kingston, Rhode Island, and a card table that came down in the family of Stephen Hopkins are from John Townsend’s early period, but their knee and foot carving differs from that on other examples examined in this study (figs. 89, 90). The toes of their front feet have an extra knuckle, the piercing above the ball is larger, and the tendons are significantly more defined (fig. 91). John Townsend used his standard lettering system on the drawers and drawer dividers of the chest, and his characteristic “M” finishing mark occurs in five places.[31]

Evidence suggests that John Townsend’s brother Jonathan also trained in Christopher’s shop, but the only documented piece by the younger man is a bureau table with a history of descent in the Pell family of Newport and New York (fig. 92). The piece had his florid signature and other writing in graphite on the underside of the top drawer (fig. 93). As this bureau suggests, it is very likely that some of the furniture historically attributed to John Townsend was made by Jonathan instead.[32]

Made when he was thirty years old and signed in graphite “John Townsend / Newport / 1762,” the card table illustrated in figure 94 is the latest piece of furniture with a graphite signature by Townsend (fig. 95). It marks a turning point in his career, from the baroque objects with delicate claw-and-ball feet that characterize his earlier output to the more aggressive legs and feet with taller balls and longer talons that typify his later work (fig. 96). The distinct knee carving is in his mature style, with tendrils on the knee brackets that nearly reach the knee and the lower section fanning out across the width of the leg.[33]

As one would expect, John Townsend’s earliest furniture reflects his training in Christopher’s shop. What is more surprising is the level of elite patronage John received at such an early age. Christopher had established strong ties with wealthy Newport residents long before John received his first order, and those relationships certainly benefited John as he ventured out on his own. John did, however, begin to develop his own style as his confidence grew and he gained exposure to new foreign design sources.[34]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their assistance with this article, the authors wish to thank David Bayne, Luke Beckerdite, Charles Burns, Dennis Carr, Sarah Anne Carter, Tara Cederholm, Maria Saffiotti Dale, Mr. and Mrs. Prescott Dunbar, Remi Dyll, Virginia Hart, Morrison Heckscher, Heidi Hill, Andrew Holter, Patricia Kane, Peter Kenny, Leigh Keno, Leslie Keno, Mrs. Angela Kilroy, Alexandra Kirtley, Caren Kraska, Mrs. Phyllis Kurfirst, Deanne Levison, Ann Smart Martin, Whitney Pape, Todd Prickett, Jonathan Prown, Robert Trent, Lynn Turner, Nick Vincent, Susan Walker, Gerald Ward, Ann Woolsey, and the institutions and collectors who allowed us to study and photograph their objects.

Charles O. Cornelius, “John Townsend, an Eighteenth Century Cabinet-Maker,” Metropolitan Museum Studies 1, no. 1 (November 1928): 72–80; Mabel Munson Swan, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners,” Antiques 49, no. 4 (April 1946): 228–31; Mabel Munson Swan, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners,” Antiques 49, no. 4 (May 1946): 292–95; Joseph Downs, “The Furniture of Goddard and Townsend,” Antiques 52, no. 6 (December 1947): 427–31; Ralph Carpenter, The Arts and Crafts of Newport, Rhode Island, 1640–1820 (Newport, R.I.: Preservation Society of Newport County, 1954); Houghton Bulkeley, “John Townsend and Connecticut,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 25, no. 3 (July 1960): 80–83; Wendell Garrett, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners: Random Biographical Notes,” Antiques 94, no. 3 (September 1968): 391–93; Wendell Garrett, “The Family of Goddard and Townsend Joiners: More Random Biographical Notes,” Walpole Society Note Book (Portland, Maine: Anthoensen Press, 1973), 32–42; Liza Moses and Michael Moses, “Authenticating John Townsend’s Later Tables,” Antiques 119, no. 5 (May 1981): 1152–63; Wendell Garrett, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners of Newport: Random Biographical and Bibliographical Notes,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1153–55; Morrison Heckscher, “John Townsend’s Block-and-Shell Furniture,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1144–52; Liza Moses and Michael Moses, “Authenticating John Townsend’s and John Goddard’s Queen Anne and Chippendale Tables,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1130–43; Michael Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport: The Townsends and Goddards (Tenafly, N.J.: MMI Americana Press, 1984); and Morrison Heckscher, John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005). On p. 76 of John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker, Heckscher notes that Townsend was twenty-four years old when he made the dining table with his signature and the date 1756. For an illustration of that object, see his fig. 50 and cat. 1, pp. 76–79.

For additional information on Christopher Townsend, see Luke Beckerdite, “The Early Furniture of Christopher and Job Townsend,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 1–30. Heckscher, John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker, pp. 48–57. Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, pp. 65–70, 247–50. Margaretta Lovell, “‘Such Furniture as Will Be Most Profitable’: The Business of Cabinetmaking in Eighteenth-Century Newport,” Winterthur Portfolio 26, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 52–56; Margaretta M. Lovell, Art in a Season of Revolution: Painters, Artisans, and Patrons in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), pp. 255–56.

Abraham Redwood purchased a desk-and-bookcase from Christopher Townsend. On February 4, 1738, Christopher wrote Redwood regarding the delivery of the desk-and-bookcase: “According to thy Request . . . I indevoured to finish a Desk and Book Case Agreeable to thy directions to send thee by Brother Pope but could not quite finish . . . and understanding it was not for thee but a friend of thine, I concluded it would be Equal to thee, If I send it by another opertunity. And having an opertunity to send it by Brother Solomon, I . . . ordered him to Deliver it to thee or thy order, thou paying him one Moyodore freight, the Desk and Bookcase amounts to Sixty Pounds this currency; includeing the two Ruf cases which is equal to fourteen heavy Pistole at £4.5.8 or fourty-four ounces and a half of Silver . . . I may let thee know that I sold such a Desk and Book Case without any Ruf cases, for £58 in hand this winter. Brother Job, also sold one to our Collector for £59. I mention this, that thou may know that I have not imposed on thee.” Christopher Townsend to Abraham Redwood, February 4, 1738, MS 93-96, Newport Historical Society, reprinted Beckerdite, “The Early Furniture of Christopher and Job Townsend,” p. 10. Christopher Townsend sold Isaac Stelle another desk-and-bookcase for £65 in 1742 and appears to have also sold other furniture to Samuel Ward, who was governor of Rhode Island during the 1760s and a client of Job’s. For additional information, see Beckerdite, “The Early Furniture of Christopher and Job Townsend,” p. 10. At his death in December 1787, Christopher was very wealthy. His estate inventory included extensive real estate on Easton’s Point and considerable silver, financial instruments, furniture, and other fine possessions. In his will dated 1773, in which he described himself as a “Shop-joiner,” he left his son John real estate holdings, including his house and adjoining shop and lots 81, 82, and 84 on Easton’s Point, as well as all of his joiner tools, mahogany, other shop joinery stock, all his desk furniture, and one-third part of all of his new desks and other joiners’ ware for sale. He also left John two of his largest silver porringers and one feather bed. To his son and namesake Christopher, a clockmaker and engraver, he left a significant amount of silver and furnishings including his “Clock and Clock Case, and Silver Watch, silver Tankard, Two silver Porringers . . . One large Mahogany Oval Table, one small Mahogany oval Table . . . one large Mahogany desk, which his brother Jonathan made, the Mahogany Desk,” which stood in his Great Room, his “large looking Glass,” two roundabout great chairs, six leather-bottomed chairs, and five large maps in frames. He left his daughter, Mary (d. 1782), real estate on Easton’s Point and his feather bed, looking glass, six maple-framed chairs, two silver porringers, and one silver cream pot. Since she predeceased her father, these items were redistributed to her children in a 1786 codicil to his will. Christopher Townsend’s will dated 1773, codicil dated 1786, and inventory dated 1792, in Heckscher, John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker, pp. 199–202.

Heckscher, John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker, p. 52; and Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, p. 66.

The high chest remained in the family of the original owners for 255 years. Its provenance identifies Lieutenant Colonel Oliver and Mary Arnold of East Greenwich, Kent, Rhode Island, as the first owners. Oliver Arnold was born to William Arnold (1681–1759) and Deliverance (Whipple) (1679–1765) of Warwick, who married circa 1705. He is listed as a freeman in Warwick in 1755 and married Mary the following year. After Mary’s death, he married Almy Greene (1727–1789) in Warwick on March 11, 1762, and served as lieutenant with the rank of lieutenant colonel under the command of Captain Benjamin Arnold of the Pawtuxet Rangers or Second Independent Company for the county of Kent, a militia chartered by the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations on October 29, 1774. Oliver Arnold appears in the 1774 Rhode Island census as living in Warwick. He is also listed in the 1777 military census for Rhode Island and the 1782 tax list for the township of East Greenwich. See Bruce C. Macgunnigle, Rhode Island Freemen, 1747–1755: A Census of Registered Voters (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1982), p. 12. Oliver Arnold’s name appears on the petition presented to the General Assembly to establish the Pawtuxet Rangers, dated October 29, 1774. The census was taken on June 1, 1774. See John R. Bartlett, Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island & Providence Plantations for 1774 (Warwick, R.I.: Providence, Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), p. 59. Given that Townsend was born on February 17, 1733, he was twenty-three years old in 1756, not twenty-four.

After Oliver Arnold died in East Greenwich on December 6, 1789, and his second wife Almy’s subsequent death, this chest descended to their daughter Sarah “Sally” Arnold (1770–1826), who married Orthneil Gorton Wightman (1763–1806) of Warwick on November 4, 1790. At Sally’s death on December 1, 1826, this chest was among the part of her estate bequeathed to her daughter Almy Maria Wightman (1793–1879), who married Stukley Wickes (1788–1873), a tailor and town clerk of East Greenwich, on February 24, 1817. Their daughter Sarah Arnold Wickes (June 1, 1824–January 1911) of Warwick was the next to own the chest. She never married and died without issue, leaving her possessions to her nieces, Almy “Allie” Wickes (1858–1914) and Mary “Minnie” LeMoine Wickes (1860–1916), daughters of her brother Oliver Arnold Wickes (1820–1905) and his wife, Harriet Elizabeth Mawney (1820–1875). Allie and Minnie, who never married, lived at the Stone House, the family homestead built by their father in 1855 on Major Potter Road in East Greenwich (now Warwick), and the high chest stood in the southeast bedroom upstairs. At the death of Oliver Wickes in 1905, the ownership of the Stone House passed to his son, Edward Stukley Wickes (May 20, 1866–July 22, 1944), a farmer, although Allie and Minnie continued to live there until their deaths in 1914 and 1916, respectively. See Warwick Will Book 8, pp. 261, 313, City of Warwick. Sally Arnold Wightman’s inventory dated January 8, 1827, records property valued at $214.55. Half of this was bequeathed to her daughters, Almy Wickes and (Ann) Catherine Wightman (1806–1885). The other half was sold at auction and the proceeds divided among six of her heirs. Sarah Arnold Wickes will, September 25, 1910, recorded February 23, 1911, Warwick Will Book 23, p. 285. Almy Wickes wrote her will on October 22, 1908, and it was recorded on September 11, 1914. In it she left her entire estate to her sister Mary. Warwick Will Book 24, p. 272. Mary Wickes died without a will but left an inventory of an estate valued at $21,788.53. Her estate included notes secured on mortgage on real estate and deposits in trust companies and banks. See Warwick Will Book 24, p. 565.

When Edward Stukley Wickes died in 1944, he left the Stone House to his nephew Edward Irving Wickes (1910–1972), noting in his will, “if the highboy now in my house should be there at my decease the same is the property of my niece Harriet and was given to her several years ago.” He is referring to his niece Harriet Almy Wickes (1908–1996), daughter of William Sands Wickes (1863–1944) and sister of Edward I. Wickes, who had inherited the chest from her Aunt Minnie. She never married and resided at the Stone House with her brother and his family. This chest remained in the southeast bedroom of the house until 1976, when she gave it to her niece. See Edward S. Wickes will, Warwick Probate Records Book 39, p. 58. The high chest was sold at Sotheby’s, Important Americana: Furniture, Folk Art, Silver, Porcelain, Prints and Carpets, New York, January 21, 2012, lot 186.

Lovell, “‘Such Furniture as Will Be Most Profitable,’” pp. 27–62. The large calligraphic letter “M” was used several times as a finishing mark: once on the back of the upper case, once on the back of the lower case, once on the bottom of the middle long drawer of the upper case, and once in the bottom of the central short drawer of the lower case. For additional discussion of the “M” finishing mark, see Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, p. 88, figs. 3.9 and 3.10. The “A” appears on the top left upper-case short drawer, the “B” on the top center drawer, and the “C” on the top right short drawer, and “D,” “E,” and “F” on the long drawers. Townsend inscribed several “E”s and “F”s on their respective drawers while also adding several “E”s to the drawer designated with a “D.”

Martha H. Willoughby notes Job Townsend Jr. buying a wig for £12.10 on December 22, 1752. Martha Willoughby, “The Accounts of Job Townsend, Jr.,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1999), p. 126.

Rhode Island Friends Record—Births and Deaths. Commerce of Rhode Island, 1726–1800, 2 vols. (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1914), vol. 1, 1726–1774, pp. 88–92. Commerce of Rhode Island, 1726–1800. Janet Fletcher Fiske, Gleanings from Newport Court Files, 1659–1783 (Boxford, Mass.: J. F. Fiske, 1998), pp. 770, 1116, 1129, 1166, 1167. Thomas Robinson’s grandfather Rowland (1664–1716) was a settler of the Narragansett area and landowner in the Pettaquamscutt and Point Judith areas, and his father, William (1693–1751), served as deputy governor of Rhode Island from 1745 to 1748. Thomas married Sarah Richardson in 1752. John Russell Bartlett, History of Wanton Family of Newport, RI (Providence, R.I.: Sidneys Rider, 1878), p. 54.

The play was first produced at the Dorset Garden Theatre in London. English essayist Joseph Addison wrote about The Orphan in the October 17, 1711 edition of the Spectator. The Redwood Library in Newport owns a copy of the 1747 publication as well as a four-volume reprint issued in 1854.

The anisodactyl foot is the most common arrangement of digits in birds, with three toes pointed forward and one back.

The dressing table was sold at Sotheby’s, Fine American Furniture, Folk Art, Folk Paintings, and Silver, New York, June 26, 1986, lot 174. It was formerly owned by Israel Sack, Inc. and illustrated in American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection (Washington, D.C.: Highland House Publishers, 1988), vol. 1, p. 65, no. 204. Minor Myers Jr. and Edgar Mayhew, New London County Furniture, 1640–1840 (New London, Conn.: Lyman Allyn Museum, 1974), p. 27, no. 22-3. See also two high chests sold at Christie’s, The Collection of Marguerite and Arthur Riordan, Stonington, Connecticut, New York, January 18, 2008, lots 581, 585.

The label is inscribed, “This Case of Drawers was formerly owned by Gov Gideon Wanton whose house stood on Coddington Street and after his Death it was sold at auction and bought by my Grand Father Perry Weaver and after his Death it came to my Mother Sarah Freeborn and after her Death it came to me. Perry W Freeborn.” Joseph K. Ott, The John Brown House Loan Exhibition of Rhode Island Furniture (Providence, R.I.: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1965), p. 94, no. 61. See also Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, pp. 182–83, figs. 3.101, 3.101a, 3.101b. Richard Pratt, The Second Treasury of Early American Homes (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1954), p. 46. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF816.

Note that each corner of the lower-case sides has a shallow vertical trench, measuring approximately 3/32 inch, matching the width of the leg tenon or square. This construction characteristic, while not found on the Arnold high chest, is found on the John Townsend high chest at Yale University (1984.32.26). While providing a slightly better surface area to secure the leg to the case, it was possibly done to avoid further shaping of the leg tenon.

The desk descended in the family of the Reverend Nathaniel Appleton and was inherited at his death by his son Nathaniel Appleton Jr. (1731–1789). After Nathaniel Jr.’s death in 1789, his wife, Rachel, may have sent it to their eldest surviving son, John Appleton (1758–1829), who was living in France as the American consul to Calais. His son John-James Appleton (1792–1864) inherited the piece. From him, it descended through three more generations of the Appleton family until a descendant sold it at Sotheby’s, New York, Important Americana, January 16–17, 1999, lot 704. See also Leigh Keno and Leslie Keno, Hidden Treasures (New York: Warner Books, 2000), pp. 255–83, who note that there may be additional Christopher Townsend signatures on the piece. For the staircase in the Christopher Townsend house, see Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, p. 71, fig. 2.1a. This desk is also discussed in detail in Beckerdite, “The Early Furniture of Christopher and Job Townsend,” pp. 18–22, figs. 33, 34, 37–39. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF242. The most avant-garde feet of the period were those produced by an as-yet-unidentified shop in Boston, Massachusetts. Alan Miller, “Roman Gusto in New England: An Eighteenth-Century Boston Furniture Designer and His Shop,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), pp. 160–200. Marijn Manuels presented the lecture “Newport Furniture: A Conservator’s Perspective” at the John Townsend Newport Cabinetmaker Symposium, Friday, May 20, 2005, where he discussed the possibility that the flame on the finials and the shells on the bookcase doors were covered with silver leaf. He also postulated that the ball feet, if originally present, may have been treated similarly.

In the desk interior, the valance drawers are marked “C” and “D.” The concave side drawers are marked “A,” “C,” and “E,” top to bottom on the proper right side, and “B,” “D,” and “F” on the proper left side. The lowest drawer behind the prospect door is inscribed “C,” whereas the markings on the drawers above are illegible. The desk was sold at Joseph Kabe Estate Auction, Milford, Connecticut, on April 10, 2010.

The exterior drawers are marked “A,” “C,” and “D.” The interior drawers when marked are done with chalk and are numbered. The desk was included in the exhibition “The Arts and Crafts of Newport Rhode Island, 1640–1820” and illustrated with later feet in the accompanying catalogue, Carpenter, The Arts and Crafts of Newport, Rhode Island, 1640–1820, no. 46. The desk was subsequently purchased by Harry Arons, who reportedly replaced the feet with ones salvaged from an eighteenth-century piece of Goddard-Townsend furniture. The desk was sold at Sotheby’s, Important American Furniture from the Collection of the Late Thomas Mellon and Betty Evans, New York, June 19, 1998, lot 2144. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF459.

A label in the third interior drawer reads, “Sold by John C. R. Tompkins Antiques, Millbrook, N.Y.” The desk has replaced brasses. Heckscher, John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker, p. 48.

The backs of the long drawers of the upper case feature the calligraphic letters “D,” “E,” and “F” in graphite. Two drawer dividers are numbered “I” and “II” in chalk, while one short drawer of the lower case in inscribed “B” in graphite, and the middle drawer, “C.” It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF817.

Christopher dovetailed three cross braces to the upper edge of the rectangular frame and dovetailed and nailed two cross braces to the bottom edge. Two legs swing on a knuckle-joint mechanism to support the oval top when open and cover a portion of the skirt when closed. The ends of the skirt are finished with applied convex moldings that continue the curve of the knees. Fine dovetailing and small dowels are evident throughout the piece. The hinged maple rails are worm-infested, as is seen on other pieces of Townsend’s work that used maple as a secondary wood. Heckscher, John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker, pp. 76–79, cat. 1. It is well preserved, retaining fifteen of its sixteen original open talons and an early finish. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF20. The Christopher Townsend table is illustrated in two John Walton advertisements: Antiques 98, no. 3 (September 1970): 292, and Antiques 110, no. 3 (September 1976): 380. It is cited twice in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object numbers RIF302 and RIF4238. It is also cited as no. 755 in the Decorative Art Photographic Collection (DAPC), Winterthur Museum. Another nearly identical drop-leaf dining table is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Its claw-and-ball feet, however, are more typical of John Townsend, and it has a cross-brace construction and skirt molding that are very closely related to his signed and dated table at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is illustrated in Moses and Moses, “Authenticating John Townsend’s and John Goddard’s Queen Anne and Chippendale Tables,” p. 1134, figs. 11, 11a. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF914 and in DAPC as no. 666. A drop-leaf dining table with square leaves in a private collection shares many similar details with this group of tables but can be attributed to Christopher Townsend on the basis of its distinctive claw feet. The frame is supported on cabriole legs that terminate in claw feet with more compressed balls, thicker digits, longer second digits, and pierced talons. This latter table is illustrated in Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, p. 150, fig. 3.72, as the property of Peter Eliot.

The table was sold at Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 20–22, 2006, lot 554, as the property of Mr. and Mrs. Thornton B. Wierum. Thornton Wierum inherited it from his paternal grandmother, Mary Briggs Thornton Wierum, and the table may have descended to her through the Briggs, Howard, and Church branches of her family.

Christopher P. Monkhouse and Thomas S. Michie, American Furniture in Pendleton House (Providence, R.I.: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1986), pp. 133–34, no. 71.

This chest is illustrated in a foreword by Alice Winchester in Antiques 79, no. 5 (May 1961): 450–51, as the property of Mr. and Mrs. William C. Harding of Norwichtown, Connecticut. It is illustrated in Ott, The John Brown House Loan Exhibition of Rhode Island Furniture, pp. 86–87, fig. 57, and included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF205.

The high chest is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF1558. The interior backs of the top short drawers are marked in chalk “A,” “B,” “C,” and “D,” “E,” and “F” on the interior backs of the long drawers of the upper case. The same long drawers are inscribed in graphite “B,” “C,” and “D.” The top long drawer of the lower case displays a chalk letter “A” on the interior back, while the three short drawers below are lettered with a chalk “A,” “B,” and “C.” It is illustrated along with a portion of George Hussey’s estate inventory in Israel Sack, Inc., American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection (Alexandria, Va.: Highland House Publishers, 1988), vol. 2, p. 556, no. 1300.

The top short drawers are lettered in Christopher’s signature manner with a chalk “A,” “B,” and “C,” while the top drawer of the lower case is marked in chalk with an “A.” The chest is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF1215. It is illustrated in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, “Living with Antiques: Chipstone near Milwaukee,” Antiques 133, no. 5 (May 1988): 1154, pl. 16; and Beckerdite, “The Early Furniture of Christopher and Job Townsend,” pp. 11, 16, 17, figs. 20, 30, 31. Beckerdite associates this high chest with Christopher Townsend on pp. 16–17 of his article. Anna K. Cunningham, Schuyler Mansion: A Critical Catalogue of the Furnishings & Decorations (Albany, N.Y.: Division of Archives and History, New York State Education Dept., 1955), pp. 52–53, no. 24.

David Warren, Bayou Bend (Houston, Tex.: Museum of Fine Arts, 1975), p. 56, no. 105. David Warren et al., American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston, Tex.: Museum of Fine Arts, 1998), pp. 63–65, no. F111. Neither Christopher nor John is known to have made the rectangular tea table form with more elaborate turreted corners. Two other simple rectangular tea tables are known, but their feet are carved in a manner associated with John Goddard. Keno and Keno, Hidden Treasures, pp. 108–9. Parke-Bernet Galleries, The Notable American Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Norvin H. Green, New York, December 1–2, 1950, lot 492. Ott, The John Brown House Loan Exhibition, pp. 32–33, no. 30. H. O. McNierney, Stalker & Boos, Inc., The Charles H. Gershenson Collection, public auction, October 23–24, 1972, lot 128.

Warren, Bayou Bend, p. 60, no. 115. Warren et al., American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection, pp. 76–77, no. f126. Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, p. 187, fig. 3.105, described this object as associated with John Townsend. The backboard bears the inscription “Bought of Miss Charlotte Foster to whom her sister left her Mother’s furniture.” The top is supported by three cross braces secured to the back with blind dovetails and to the front rails with mortise-and-tenon joinery. The holes on the braces indicate that the original top was attached with nails. The drawers have poplar sides and bottoms, which is consistent. The dovetails are similar to those used for his other work, although drawer A has smaller dovetails, apparently made by another craftsman. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF827.

This piece is illustrated and discussed in Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, pp. 177–79, figs. 3.99, 3.99a–d; Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1988), pp. 265–68, no. 140; Heckscher, John Townsend: Newport Cabinetmaker, cat. 8, pp. 90–92. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF3606.

Christie’s, Important American Furniture and Folk Art, New York, January 20, 2012, lot 113. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF21.

The backs of the drawers display letters in florid script, with the top drawer lettered “A” in chalk, the second drawer from the top lettered “B C D E” in graphite, the third with a “C” in graphite, and the bottom drawer with “A B C D E F” in graphite. The bottom board glue blocks are significantly chamfered on their outer edge, as are found on other Townsend pieces. As with the Arnold high chest, the backsides of the drawer fronts are toothed with a toothing plane. Of note: the front base molding is pieced in the concavity, probably to avoid using a thicker piece of wood. The top is secured with nails driven through the white pine subtop, and the top drawer can be opened only by releasing the wooden spring lock attached to the drawer’s bottom. The bottom 3 1/2 inches of the feet are replaced. Clement E. Conger and Alexandra Rollins, Treasures of State: Fine and Decorative Art in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms of the U.S. Department of State (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1991), pp. 125–26, no. 45. It is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery as object number RIF664.

Sotheby’s, Fine Americana, New York, June 17, 1998, lot 1191.