Desk attributed to the WH cabinetmaker, northeast, North Carolina, 1780–1790. Walnut with walnut and yellow pine. H. 47 3/4", W. 46", D. 22 5/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photo, Katharine Wetzel.) This desk was found in Halifax, North Carolina.

Secretary press attributed to the WH cabinetmaker, northeast, North Carolina, 1785–1795. Walnut with walnut, yellow pine, and oak. H. 110 1/4", W. 48 1/4", D. 22." (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

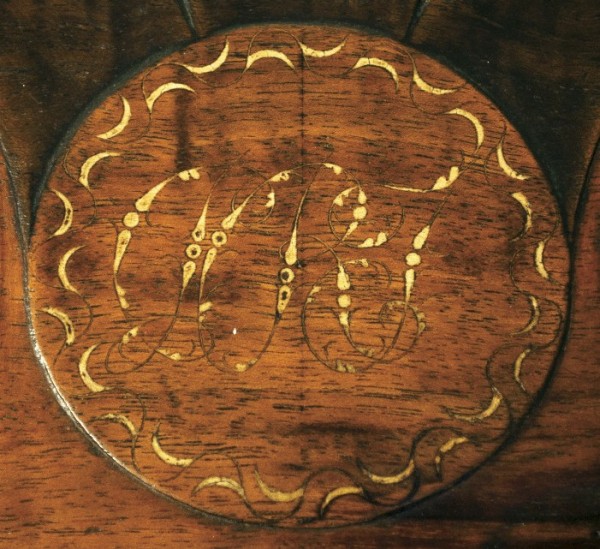

Detail of the monogram from the secretary press illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, F. Carey Howlett).

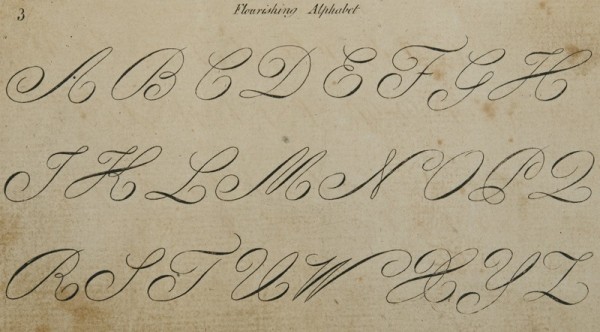

“Flourishing Alphabet,” from George Fisher, The Instructor, or American Young Man’s Best Companion. . . . (Worcester, Mass.: Isaiah Thomas, 1786), pl. 3. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society.)

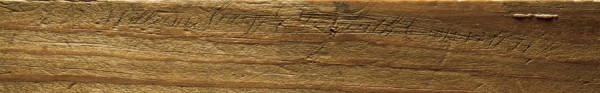

Detail of the secretary press illustrated in fig. 2, showing the location of the inscribed names. (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

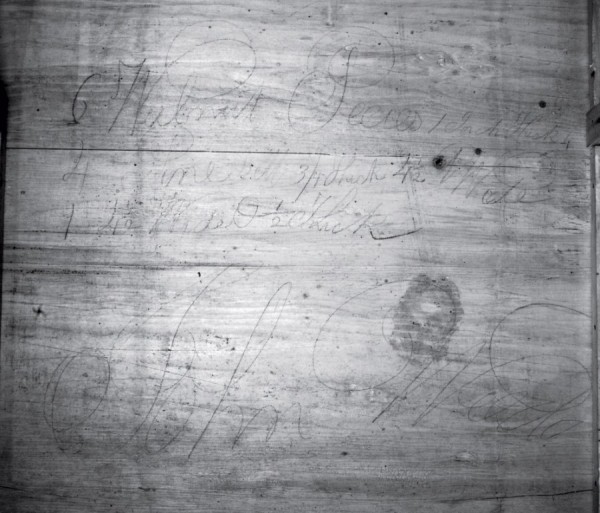

Raking-light image of the inscription on the secretary press illustrated in fig. 2 (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

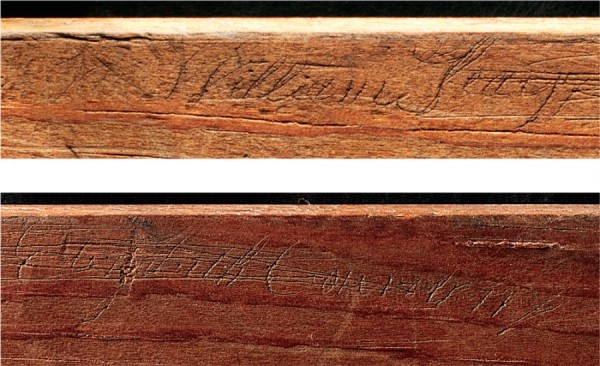

(Top) A portion of the inscription illustrated in fig. 6 showing the name “William Seay” viewed using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) rendered in static mode. (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, Travis Fullerton.) (Bottom) A portion of the inscription illustrated in fig. 6 showing the name “Elizabeth Cou[illeg.]” viewed using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) rendered in unsharp mask mode. (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, Travis Fullerton.)

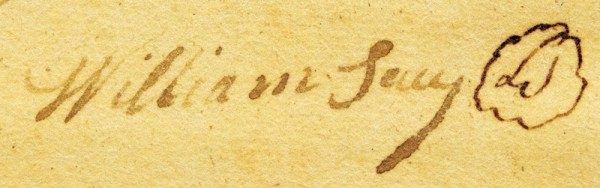

Signature of William Seay on an indenture document for Joel Bird, May 11, 1774. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

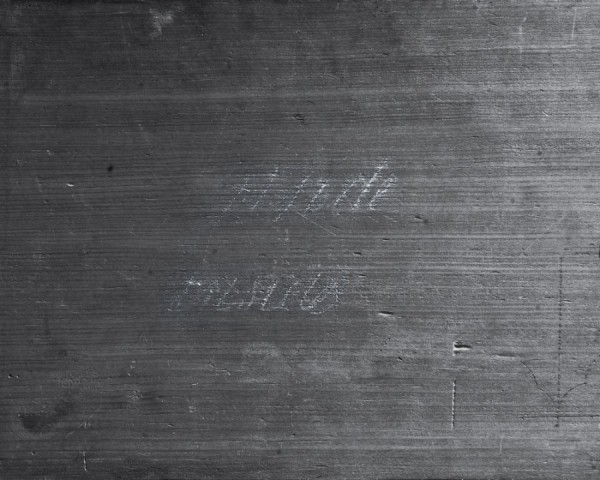

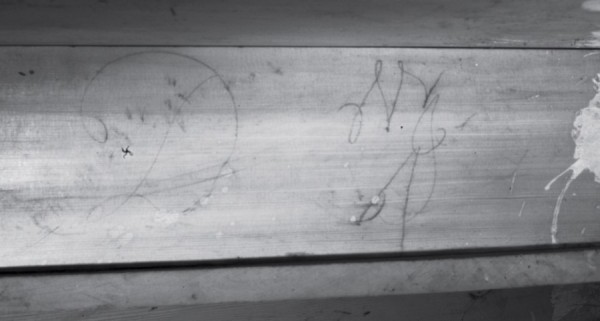

Chalk inscription on the inner face of the proper right side of the bottom drawer of the secretary press illustrated in fig. 2. (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, Travis Fullerton.)

Cross-polarization photograph of chalk inscription illustrated in fig. 10 converted to black and white and enhanced with Adobe Photoshop. (Photo, Travis Fullerton.)

Secretary press attributed to the WH cabinetmaker, northeast, North Carolina, 1785–1795. Walnut with yellow pine and walnut. H. 107 1/2", W. 44 3/4", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Chrysler Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This press descended in the Smithwick family of Hartford County, North Carolina.

Inscription on the top of the lower case of the secretary press illustrated in fig. 12. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina. Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Inscription illustrated in fig. 13 viewed using cross-polarization to search for additional evidence of ink. (Photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

Desk illustrated in fig. 1 with fallboard open. (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.) Furniture scholar John Bivins published this image in a section on the WH cabinetmaker in The Furniture of Eastern North Carolina.

Raking side-lit cross polarized image of the inner face of the bottom drawer of the desk illustrated in fig. 1. No chalk is present, although the sloping wavy figure of the walnut resembles handwriting. (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photo, Travis Fullerton.)

Wavy figure is not visible in a raking top-lit cross polarized image of the same view as fig. 16. The surface reveals jackplane marks but no presence of chalk. (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photo, Travis Fullerton.)

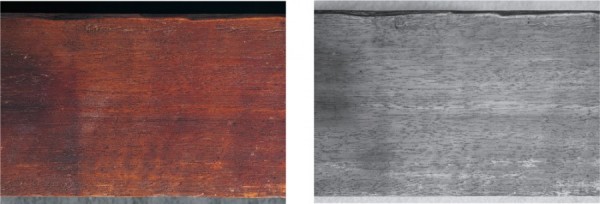

Standard photograph (left) of the wavy figure on one of the lid supports of the desk illustrated in fig. 1. No ink is visible. (Photo, Travis Fullerton.) A second image using reflected ultraviolet photography (right) demonstrates that no ink is present.

Standard photography (left) of the outer surface of the side of the bottom drawer of the desk illustrated in fig. 1 reveals a series of angled scratches and a reflected ultraviolet image (right) shows no evidence of an ink inscription. (Photo, Travis Fullerton.)

Standard photograph of the bottom edge of the bottom drawer of the desk illustrated in fig. 1 reveals blanched surface drips associated with refinishing rather than the initials “TBH.” A second image (bottom) shows similar drips on another drawer. (Photos, Travis Fullerton and F. Carey Howlett.)

(Top) A photo captured using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) in image unsharp mask mode showing an uneven six-legged zigzag scratched into a lid support of the desk illustrated in fig. 1, clearly not handwriting. (Photo, Travis Fullerton.) (Bottom) With light position changed in the RTI viewer and RTI photography rendered in diffuse gain mode, an unrelated V-shaped depression is visible crossing the zigzag scratch, suggesting an overlapping cipher. (Photo, Travis Fullerton.)

Hope Plantation House, Windsor, North Carolina, completed ca. 1803. (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation.) Hope was the home of home of David Stone, a former governor of North Carolina.

Standard photograph of a stair riser at Hope Plantation, showing an inverted “W” at right and several other pencil markings. (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

An infrared photograph of the stair riser illustrated in fig. 24 shows the differing intensities and orientations of the pencil-inscribed letters on the stair riser, clear evidence they were written at different times; no names are present. (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

Sideboard associated with the WH group of furniture, northeast, North Carolina, 1810–1820. Walnut with yellow pine, H. 39 1/2", W. 69 1/2", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic Hope Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Standard photograph of the inner surface of the back of the sideboard illustrated in fig. 26 showing a large, lengthy, but nearly illegible pencil inscription. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

In a reflected infrared image of the inscription illustrated in fig. 27, the handwriting is completely legible. (Photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

Tympanum board attributed to the WH cabinetmaker, northeast, North Carolina, 1792–1796. Walnut, ebonized ornament and putty inlay. H. 18", W. 44". (Private collection; photo, Craig McDougal.)

Cross-polarization photo of the large chalk inscription on the back of the tympanum board illustrated in fig. 29. (Photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

Processed cross-polarization photo of the first letter of the inscription illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

Processed cross-polarization photo of the name “Haskell” and additional lettering illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, F. Carey Howlett.)

An inscription on the surface of a piece of furniture can be an outstanding aid to research, sometimes providing definitive identification of a maker, owner, retailer, or user. An inscription can also be an interesting but rather mundane vestige from the age of handcraftsmanship—a remnant of a cabinetmaker’s work in the form of an alignment mark, orientation mark, cost notation, or list of materials. Whatever their original purpose, inscriptions are often faint, worn, incomplete, obscured, or poorly written. Interpreting such inscriptions on furniture can be difficult at best and speculative at worst, sometimes resulting in misinformation and faulty attributions.

By maximizing the possibilities for obtaining new and useful information from inscriptions, scientific imaging is a powerful tool for extending the eyes of the conservator, curator, and scholar. Forensic scientists and conservators have used specialized imaging techniques for years, but only since the advent of digital photography have some of them become cost-effective and accessible to anyone interested in learning them. The techniques discussed here are beneficial, whether providing a solid foundation of physical evidence to document the maker of a particular object or simply adding details to our knowledge of its history of manufacture, ownership, and use.

This article demonstrates a range of imaging techniques and their applicability by looking at several examples of furniture associated with northeastern North Carolina’s enigmatic WH cabinetmaker, so called because a number of objects have finely executed calligraphic monograms bearing the initials “WH.” This group of more than thirty objects has been of considerable interest to scholars for years, because of curiosity about the identity or meaning of “WH” and because of their idiosyncratic structure and ornament. Many objects in the WH group have histories of descent in families from Halifax, Northampton, Bertie, and Hertford counties, and all have details associated with the Roanoke River basin school of cabinetmaking—a designation used by furniture scholar John Bivins in The Furniture of Eastern North Carolina. In an attempt to explain the presence of Germanic features on objects made in a region populated largely by people of English descent, he speculated that the maker may have been a Hessian soldier who deserted Cornwallis’s army during the American Revolution and settled near Halifax, North Carolina. Certain ornamental details used by that maker are unique in American case furniture: the unusual relief-carved and ebonized compass-work designs often found on pediments of the WH group are signature features and may indicate a northern European source. The highly detailed putty-inlaid monograms, meanwhile, are more akin to the work of a metal engraver than a cabinetmaker. Despite these singular features, no documentary or physical evidence survives to associate the group with a particular maker.[1]

A recent book written by Thomas R. J. Newbern and James R. Melchor brought scholars and collectors the news that the mystery of the WH cabinetmaker had been solved. Their monograph reported the discovery of numerous inscriptions identifying house carpenter William Seay as the maker of the group. His work in the building trade is documented by two indentures. In 1774 Seay took Charles Rhodes as an apprentice “carpenter” and Joel Bird as “carpenter and joiner.” Similarly, Seay’s purchase of lumber, tools, and hardware at the 1802 estate auction of Bertie County cabinetmaker Thomas Sharrock suggests that the former may have made furniture. But, since many regional house carpenters and joiners did the same, Newbern and Melchor’s contention that Seay was the maker of the WH group is linked almost entirely to the inscriptions the authors cite.[2]

Several factors made furniture in the WH group ideal for a case study on imaging techniques. Foremost was Newbern and Melchor’s assertion that William Seay’s name appears on several case pieces as well as on architectural elements. Although a single inscription is rarely sufficient to identify an individual as the maker, the appearance of the same name on multiple objects in a group can, in the right context, warrant attribution. The authors’ book also contains intriguing references to illegible script, which suggests that specialized photographic techniques might enhance legibility. Because the authors presented their evidence in a nontraditional manner—usually an untouched image of markings or features accompanied by a duplicate “enhanced” image altered with pencil, ink, or chalk—imaging provides an unbiased basis for evaluation and interpretation of their findings.

A desk in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts provided special impetus for this study (fig. 1). According to Newbern and Melchor, the desk has six inscriptions associated with Seay and is “one of the most fully documented pieces of Southern furniture, a true Rosetta stone for this group.” Based on their findings, the authors developed a history for the desk that extended well beyond its known provenance. In contrast, an investigation undertaken by the museum revealed no inscriptions on the desk, which raised questions regarding other marks associated with the WH group.[3]

This study demonstrates several effective techniques for enhancing the legibility of inscriptions on furniture, but informed interpretation relies on several factors. Experience in paleography, the study of historic handwriting, is very helpful, as knowledge of period letter forms, historic abbreviations, spelling, and other conventions can simplify interpretation. A good understanding of traditional writing implements, as well as a logical sense of those most likely to have been used by a cabinetmaker or an owner, is also helpful. Indeed, it is clear that owners were more likely to inscribe names in ink, whereas makers’ names are generally in pencil, red crayon, and occasionally chalk—all materials typically found in a cabinetmaker’s or joiner’s toolbox. Access to archival documents in the form of deeds, tax lists, inventories, indentures, and other records is beneficial when testing the plausibility of a discovered name, particularly if signatures are located for comparison with those found on furniture. The context and location of any suspected inscription are also of paramount importance. Experience and logic indicate that makers’ names most frequently occur on surfaces of upper drawers or on backboards, where they are easily observed in a cursory examination. Owners’ names generally occur in the same locations, though they are even more likely to be found on desk interiors and are unlikely to be associated with inscriptions made before assembly. Makers’ names also occasionally appear in locations indicating pre-assembly writing, while logic dictates that owners’ names were generally inscribed after construction.

When searching for inscriptions, a healthy skepticism is important. One should never assume from the outset that writing will be found, and, if present, that it was intended for posterity. Most surviving examples of American furniture are not inscribed with names, and when they are, the name is rarely that of the maker.

The techniques used in this study were based on the nature of the materials undergoing examination. This study used Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), a recently developed technique ideal for looking at low-relief objects, to examine a few incised surfaces; cross-polarization to examine faint chalk inscriptions and one inscription below a yellowed coating; and infrared reflectography to examine graphite (pencil) inscriptions. Ultraviolet fluorescence examination, a common technique for characterizing coatings, is largely ineffective when examining inscriptions, especially graphite and calcium carbonate, but UV reflectance photography proved useful in searching for inscriptions in iron gall ink. All of the techniques and equipment used to obtain the photographs in this study are presented in the appendix to this article.

Secretary Press, Hope Plantation, Windsor, North Carolina

The secretary press illustrated in figure 2 has many features characteristic of WH case pieces dating from the early to mid-1790s: an enclosed scrolled pediment; a tympanum decorated with ebonized low-relief leaf carving flanking a roundel with putty inlay; a pierced anthemion-like central finial (largely replaced); and drawer bottoms flush-mounted with the sides. The monogram is unique to the group and might ultimately prove useful in identifying the original owner (fig. 3). Earlier researchers have interpreted the initials to be “CRT” or “CRJ,” but comparison with letters in George Fisher’s The Instructor, an American writing manual published in 1786, suggests that the conjoined letters are “PRT.” Indeed, the striking similarity of the letters on the roundel and those in Fisher’s “Flourishing Alphabet” raises the strong possibility that the maker of the roundel owned, or had access to, a copy of The Instructor (fig. 4).[4]

INCISED INSCRIPTION: “WILLIAM SEAY”—MAKER OR OWNER?

Technique: Reflectance Transformation Imaging

Newbern and Melchor discovered the inscription “William Seay” on the secretary press in 2009, but they failed to detect a partial second name, “Elizabeth Cou[illeg.].” The entire inscription, though approximately 4 7/8 inches long with capital letters 1/2 inch high, is barely visible near the upper edge of the inner face of a side of the third large drawer (fig. 5). The second name is less legible: the inscription is partially crossed out with scratches made by what appears to be the same tool used to make the lettering; the scratches are centered on the first word of the second name. Standard photography using raking light proved somewhat effective at enhancement, clearly indicating this word to be “Elizabeth,” but the final word remains indecipherable (fig. 6).

Since the inscription is incised, we decided to examine it more thoroughly using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), a technique recently developed for enhancing the visibility of nearly illegible low-relief surfaces such as corroded ancient coins or worn heiroglyphic tablets. The technique involves taking a series of photographs of the object using a fixed camera position but changing the position and angle of a single light source for each image at regular intervals and at the same distance from the object. The images are compiled into a single file using specially designed software. The file is then opened in the RTI viewer, which has a circular trackpad that permits viewing of the photographed object as if it were being illuminated in real time and from any angle using a variety of rendering modes, thereby permitting a detailed examination of the three-dimensional form of an object.[5]

This form of examination has several advantages over standard photography. Once the images are captured and compiled, an examiner can take as much time as needed working at the computer to rearrange the lighting virtually in infinite variations. Markings can be fully analyzed, providing insight into the tools that made them. By manipulating the lighting, one can minimize unrelated features that can be mistaken for part of the inscription or those that interfere with its legibility, such as the scratches across the name “Elizabeth.” Words that are unclear because of odd spellings or misshapen letters, such as the last word of the second name, can be thoroughly examined letter by letter at higher magnification to search for faint line extensions or loops that may be visible only under specific lighting conditions.

RTI examination led to a number of insights about the inscription. The names were apparently written using a metal stylus. The lines range from nearly imperceptible depressions to deeper visible scratches cutting through wood fibers, and the writer wrote much as he or she would have written with a quill pen, using greater pressure on the downstrokes than on the upward-moving arcs. Each “i” in “William” is emphatically dotted with a circular puncture, additional evidence pointing to a metal stylus. A faint “M” followed by a smaller mark suggesting a superscript “r” is visible before the name “William.” The name “Seay” was inscribed twice—perhaps the first version was too faint (fig. 7). A single letter appears between “Seay” and “Elizabeth”—either a “y” from the first attempt at “Seay” or a typical shorthand notation for “et” (and). A slight amount of color darkens the recessed lines, but there is no ink or graphite present: either someone rubbed a small amount of dark pigment into the recesses of the inscription at some point to make the letters more visible, or dirt became embedded in the inscription over time.

The final word of the second name remains unclear, demonstrating that there are limitations to any examination technique (fig. 8). The word is undoubtedly the work of the same hand using the same tool and written at the same time as the other words, but the writer was constrained by two factors. First, the names were intentionally inscribed on a wide, soft earlywood band in the yellow pine, and the first three words all fit reasonably well within a fairly wide horizontal section of the band. The earlywood begins to narrow and slope downward at the beginning of the fourth word, and the resistance of the hard latewood interfered with the flow of the writing, sloping the name and constricting the letters. Second, it is likely that the tight confines of the drawer inhibited the writer, since the writing arm was pressed against the drawer back while the final word was inscribed.

Interpreting the inscription “Elizabeth Cou[illeg.]” is problematic. There is convincing evidence that William Seay married Elizabeth Rutland Tyler (widow of John Tyler) by 1790, when he appeared in the federal census as a resident of Hertford County. However, that fails to explain why “Elizabeth” was crossed out or to clarify the remaining inscription, “Cou[illeg.].” It is tempting to interpret the last letters as the beginning of “Courtney” or “Coventry,” but those surnames are not documented in the Roanoke River basin during the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries. One might also speculate that “Elizabeth Co[illeg.]” refers to Elizabeth City County (a former county of Virginia, now the city of Hampton) approximately one hundred miles northeast of the region associated with WH furniture, or to the town of Elizabeth City, North Carolina, approximately the same distance directly east. However, there is no evidence linking William Seay to either of those places, and again, the number and arrangement of the letters making up the final part of the inscription do not clearly spell the words “City” or “County.”[6]

The location of the inscription indicates it was made after the drawer was fabricated and assembled: it would be impossible to inscribe names right-side up anywhere else on the inner surface of a drawer side, and the upper loop of the “S” in the name “Seay” extends onto the rounded-over upper edge of the drawer side. The writer was probably right-handed, as the writing, which is on the inner face of a proper right drawer, begins about eight inches from the front corner of the drawer, an impossible location for a left-handed writer to begin.

The incising on the drawer can be compared with three ink signatures by Seay, two dating from 1774 and a third from 1800. All four inscriptions have an even rightward slope, and while there is general consistency with the forms of nearly all the letters, the “W” is perhaps the most telling. Each “W” starts with a simple arc flourish that begins near the highest point of the letter, curves down no lower than the letter’s midpoint, then rises up to the top of the first leg. Downstroke legs are slightly S-curved, with at least one in each signature and in the incised name showing a distinct loop at the bottom leading into an upstroke. The final upstroke in the ink signatures as well as the incised name are simple, slightly outward-curving lines ending abruptly just above the midpoint (fig. 9).

Although Seay inscribed the secretary press, that does not mean he was the maker. The near imperceptibility of the inscription under normal lighting conditions, its strange and unobtrusive location high on the upper inner face of the third large drawer, the uncommon manner in which it is incised in the wood, the fact that it was written after assembly, and the presence of a second name—possibly that of William Seay’s wife or an earlier Elizabeth of his acquaintance—strongly suggest that “William Seay Elizabeth Cou[illeg.]”denotes ownership or use rather than authorship. The only circumstance that would lend support for Seay’s being the maker of the WH group would be the discovery of similar inscriptions on other related examples. As will be shown, the inscription on this secretary press is unique in its execution, and that object is the only known piece bearing the name “William Seay.”

CHALK INSCRIPTION: A JOURNEYMAN’S NAME OR A SIMPLE REMINDER?

Technique: Cross-polarization

Newbern and Melchor note that the secretary press has another inscription on the inner face of the proper right side of the bottom drawer (fig. 10). This inscription is in white chalk, a material historically used by cabinetmakers as an aid in assembling parts during construction. Calcium carbonate inscriptions are notoriously difficult to read. By its nature, the material is ephemeral: a light surface dust easily smudged, brushed, or wiped away. Such inscriptions are often frustrating even when they can be read. More often than not, an inscription initially interpreted as a name or signature, usually because of prominent but typical eighteenth- or nineteenth-century flourishes to the letters, will ultimately reveal itself as something less significant, such as “Bottom,” “Top,” or “Right.”

Newbern and Melchor interpreted the inscription to read, “Made by Britain” and postulated that Britain was a journeyman who lived near Seay’s property in Roxobel, Bertie County. The inscription actually reads, “Left side/inside,” a practical reference to the orientation of the drawer side for proper assembly. The words “side” and “inside” are reasonably legible in a conventional photograph, but to bring out the faint lettering of the word “Left,” we used cross-polarization photography followed by contrast enhancements using Adobe Photoshop (fig. 11).

Cross-polarization is a technique generally used for photographing highly reflective surfaces such as silver and glass, but it can enhance the visibility of a chalk inscription on bare wood by eliminating glare from the wood surface. Such reflectivity is barely noticeable in most situations, but it can interfere with the visibility of fine details such as very faint chalk inscriptions. In cross-polarization photography, a polarizing filter is placed over the light source and a polarizing ring is placed over the camera lens. When the ring is rotated to the correct position, the light waves reaching the camera sensors are all oriented in the same plane. Light scatter is eliminated, so the surface is visible with no interfering glare.

The word “Left” was visible initially as a series of very faint diagonal lines. Cross-polarized light enabled the camera to read more of the surface, and Photoshop enhancement followed by magnified inspection of the “L” provided clear visual evidence of its previously unseen upper and lower loops. While the “e” has been wiped away and the “ft” remains fragmentary, the phrase “Left side / inside” is a convincing interpretation of the handwriting, especially in light of its location on the drawer and the fact that chalk lettering typically served a utilitarian function for a cabinetmaker or joiner.

Secretary Press, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia

The only example of ink lettering found in this study is present on a secretary press illustrated in figure 12. The two-part press is very similar in form and ornament to the preceding example (fig. 2), with the chief difference occurring in the lower carcass: rather than containing full drawers, it is fitted with walnut doors enclosing four painted yellow pine linen slides. The scrolled pediment retains its original ebonized decoration on the cornice bead as well as on the low-relief leaf carving surrounding a well-executed “WH” monogram. An unusual slatted slide is fit into the lower case above the desk interior. The upper rails of the glazed doors are shaped, and the original feet survive nearly intact.

INK INSCRIPTION: A LONE “W” OR MORE?

Techniques: Cross-polarization, Reflected Ultraviolet Light

The letter “W” is located on the yellow pine top of the lower case, approximately 6 inches from its front edge and thus hidden from view when the piece is assembled and in use. It is a bold, calligraphic letter, standing approximately 1 inch high, with a pronounced contrast between thin and thick strokes. The width and form of the strokes suggest application of ink with a small brush rather than a quill pen. Somewhat lower and a few inches to the right is a considerably smaller, less-definite ink stroke that appears to be the upper portion of a letter. A somewhat opaque yellowed varnish residue obscures any remainder of this letter, and no additional lettering is visible in normal light (fig. 13).

Newbern and Melchor maintain that this inscription reads “W Seay” and that it is written in the same hand as the incised inscription on the secretary press illustrated in figure 2, but there is no evidence to support either assertion. There is too little of the second letter to indicate that it is an “S,” and there is no visible evidence of the letters “eay” following it. The form and execution of the “W” are very different from those in William Seay’s signatures and the incised name visible in figure 7. On the secretary press illustrated in figure 12, the “W” is somewhat vertical and awkwardly formed with only slight curves to all strokes, except for a long, initial, thin-lined arc, a flourish that constitutes more than half the overall length of the letter. This flourish swoops down to the imaginary line at the base of the letter, an unusual feature for an eighteenth-century “W,” which makes the letter easily confused with an “M.” The thick downstroke legs are connected to the thin upstroke lines with abrupt, acute angles and no continuous loops, and there is no curve to the final upstroke. It is very unlikely that the same hand produced the incised names on the other secretary press (figs. 2-8).

Attempts to improve the visibility of the second letter and to search for additional lettering proved fruitless. As the “W” and the additional stroke were most likely produced using iron gall ink, reflected ultraviolet photography was considered the best option for enhancing any faint lettering, as iron gall ink tends to absorb UV radiation, making it stand out against a wood background in a reflected UV photograph. Here the technique did not reveal any new information. Either there is no additional lettering, or it is too obscured by varnish to become visible in a reflected UV photograph (UV radiation does not penetrate deeply). A second photograph was taken using cross-polarization in an attempt to cancel out any unwanted light scatter and “see through” the yellowed varnish. Once again, no additional lettering became visible (fig. 14).

In sum, there is insufficient evidence to assume the writer of the letter “W” and maker of the secretary press are one and the same or to demonstrate that the “W” is a partial signature of William Seay. It is also unlikely there is additional writing beneath the yellowed varnish. The varnish is sufficiently thin to reveal the contrast between the early- and latewood, so any lettering produced by iron gall ink, a material of marked contrast to the yellow pine, should also be visible.

Desk, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia

The desk illustrated in figures 1 and 15 is one of the most exceptional examples from the WH group. It is notable for the pronounced blocking of the façade and desk interior, which, in addition to its shaped, square quarter-columns, gives it a Continental baroque appearance rare in furniture from the American South. Indeed, numerous structural elements, including the abundant use of closely spaced nails attaching the drawer beading, the square form of the beading, the heavy blocking of the feet, and the thickness of the drawer sides suggest that the maker trained in a German cabinetmaking/joinery tradition. Although the desk does not exhibit the ornament that most graphically defines the work of the WH cabinetmaker—a relief-carved ebonized floral motif or a calligraphic monogram—several other objects in the group bear these ornamental details as well as the unique combination of Continental structural elements described above. Since the desk contains the earliest stylistic and structural features associated with the WH group and reflects the purest European influence, it may be the earliest object associated with the WH cabinetmaker.

The desk has two paper labels on components of the interior, both with the ink inscription “Ursula M. Daniel, Halifax, NC.” Before it was sold to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 1949, the desk appears to have descended in the Daniel or Garry families of Halifax; letters from the Daniel family at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts attest to that tradition. The desk received heavy use as a work surface during part of its existence: there are numerous abrasions and scratches, and the writing surface of the desk lid and the secondary wood of one of the interior drawers are defaced with imprints of an unidentified stamping tool.[7]

Newbern and Melchor reported the discovery of six previously undocumented inscriptions on the desk: two separate signatures of the name “W Hill” on an exterior face of a large drawer and on one of the lid supports, two adjacent signatures showing the name “W Seay” on the interior face of a large drawer, the initials “TBH” on the bottom edge of the bottom large drawer, and the cipher “MW” on the other lid support. The authors postulate a history of the desk that predates its Daniel family ownership: the desk was made by William Seay on commission from Whitmell Hill as a gift for his son Thomas Blount Hill. The cipher “MW” showed that Micajah Wilkes, a supposed journeyman working for William Seay, contributed to the construction of the desk.[8]

On learning of these findings by Newbern and Melchor, a team of conservators, a curator, and the staff photographer at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts examined all the sites described above, with the intent of securing publishable photographs of any newly discovered inscriptions for the authors. We conducted examinations using normal lighting, raking light, ultraviolet fluorescence, and infrared reflectography, but the examination proved fruitless. In a recent follow-up examination, Reflectance Transformation Imaging was used in addition to the earlier techniques, and additional time was taken to ensure that all sites were thoroughly evaluated. Once again, no names or initials came to light. Although a range of imaging techniques was used in examination of these sites (except for RTI, which was used only in the examination of the incised cipher), the photographs shown here were selected as the best means to illustrate the features incorrectly identified as inscriptions by Newbern and Melchor.

REPORTED SIGNATURES (2): “W SEAY” IN CHALK, BOTTOM DRAWER, INNER FACE OF PROPER RIGHT SIDE

Technique: Raking Light, Cross-polarization

According to Newbern and Melchor, the name “W Seay” is written in chalk twice on the inner face of the large bottom drawer, one inscription appearing just above and one directly below the residue of an apparent mud dauber’s nest. Chalk, as a fine powder on the surface of an object, tends to show well in raking light, and, as mentioned earlier, cross-polarization can eliminate any reflective interference. While chalk may appear more pronounced when viewed with the light coming from a particular angle, photos taken from any angle should reveal some evidence of it. Photographs of the site demonstrate clearly that no chalk is present. In the first image the raking light source was placed well to the right of the drawer side and nearly parallel with the wood grain, clearly reflecting the wavy-grained walnut of the drawer side, with the waviness sloping to the right in a manner suggestive of handwriting (fig. 16). In the second image the light comes from above and is essentially perpendicular to the grain (fig. 17). From this angle the wood is evenly reflective: the wavy grain is imperceptible, and nothing is visible on the surface except jackplane marks and the mud dauber residue. The tendency for cabinet woods such as walnut to display so much variance in reflectivity is a desirable characteristic known as chatoyance, or the cat’s-eye effect. Here the effect led to the misinterpretation of the wood grain as a chalk inscription reading “W Seay.”

REPORTED SIGNATURE: “W HILL” IN INK, PROPER RIGHT LID SUPPORT, OUTER FACE

Technique: Normal Lighting, Reflected Ultraviolet Light

Newbern and Melchor also refer to a very small ink inscription reading “W Hill” on the outer face of one of the lid supports. No examination technique used by the team at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts revealed any evidence of ink. Here, reflected ultraviolet light photography was particularly useful, as it revealed no evidence of historic iron gall, logwood, or carbon ink. As the photographs shown here illustrate, the authors appear to have misinterpreted sloping wavy-grained walnut to be an inscription (fig. 18).

REPORTED SIGNATURRE: “W HILL” IN INK, BOTTOM DRAWER, OUTER FACE OF PROPER RIGHT SIDE

Technique: Normal Lighting, Reflected Ultraviolet Light

Newbern and Melchor published an enhanced image showing the name “W Hill” in large letters running perpendicular to the length of the bottom drawer side. Examination revealed no evidence of ink on the surface and proved conclusively that the “inscription” is a cluster of abrasions on the wood surface, once again sloping in a manner suggestive of handwriting (fig. 19).

REPORTED INITIALS: “TBH” IN CHALK, BOTTOM DRAWER, BOTTOM EDGE

Technique: Normal Lighting

Newbern and Melchor reported finding the initials “TBH” in chalk on the bottom edge of the bottom drawer. This location is problematic for an inscription of any kind: one would not typically expect to find writing, particularly the name of an owner, in such a concealed location that is so vulnerable to wear. The markings interpreted as chalk initials are visible as light-colored bands as much as 1/4 inch wide. Similar bands occur on the edges of all side and bottom edges of the large drawer faces. They are clearly patterns of blanching made by solvent drips associated with a twentieth-century finish removal. Most are straight drips, but in the case of the drips interpreted as “TBH,” the bottom drawer was apparently turned ninety degrees in mid-drip, thereby crossing the “T” and connecting the legs of the “B” and “H” (fig. 20).

REPORTED CIPHER: INCISED “MW,” PROPER LEFT LID SUPPORT, OUTER FACE

Technique: Reflectance Transformation Imaging

Newbern and Melchor illustrate markings identified as an incised cipher of the letters “MW” on the outer face of one of the lid supports and relate those letters to a much clearer “MW” cipher found on the rear rail of a Roanoke River basin bottle case in the collection of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The markings are very faint and barely visible in normal light, partly because the lid support shows numerous fine abrasions on all surfaces, evidence of very hard use. As the markings are definitely scratched into the surface, Reflectance Transformation Imaging was selected as the best option for enhancing their visibility. Two photographs are provided to show fully the features the authors referred to as a cipher. The first shows the lid support illuminated by raking light from the right just above the center point. Rendered in “image unsharp masking” mode and viewed with high-gain, specular light, the photo reveals an uneven six-legged zigzag beginning on the upper side face of the applied bead on the vertically grained end of the lid support and extending several inches before ending along the top edge of the support (fig. 21). When raking light is shifted to the upper left and the image is rendered in diffuse gain mode, an unrelated, shallow, V-shaped depression appears to overlay a portion of the zigzag, roughly suggesting the appearance of a cipher (fig. 22). RTI demonstrates the random nature of this juxtaposition: no initials are inscribed on the lid support[9]

The result of this investigation is that the desk in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts does not support an attribution to William Seay or anyone else: the history postulated by Newbern and Melchor has no basis in fact. In a search for the identity of the maker of the WH group of furniture, the desk proved more of a blank slate than a Rosetta stone, and the desk’s provenance remains unchanged.

Staircase Riser, Hope Plantation, Windsor, North Carolina

Newbern and Melchor identified William Seay as both the WH cabinetmaker and the primary builder of a number of large houses in the Roanoke River basin. Among the most prominent is David Stone’s residence at Hope Plantation, completed circa 1803 (fig. 23). The attribution of the house to Seay is based on the authors’ discovery of the inscription “W Seey” on the reverse of a riser in a service staircase at the house, visible inside a small closet entered from the staircase landing. The authors also attribute the writing to one of Seay’s apprentices.[10]

Visual inspection of the stair riser reveals an inverted “W” and a few additional letters in pencil. The style of the handwriting is correct for the period of the house, and, as stated by the authors, the inscriptions predate assembly (fig. 24). Infrared reflectography was chosen as the best technique for additional examination: it is ideal for looking at pencil inscriptions because of the strong absorption of infrared light by graphite, making it stand out more clearly than it does in normal light. In the infrared photograph, the inverted “W” is visible at right with an illegible scribble below it, both in bold pencil. A large “D” in finer pencil is at left, and a smaller “g” or “J” in the same hand lies between the “W and the scribble. The “W” and “D” are not only oriented differently, they are unrelated and by different hands. The “D” and a few nondescript smudges within its bounds do not spell “Seey” (fig. 25).

The primary builder of the Hope Plantation house remains unknown. Local tradition associates the house with Jeremiah Bunch and his brothers, a family of free black house builders living close to Hope Plantation at the time. There is also reason to believe the Sharrock family of Roxobel, North Carolina, contributed to the interior woodwork, but there is no known document associating William Seay with the construction of David Stone’s house at Hope Plantation. Indeed, Newbern and Melchor’s attribution of at least three other houses to William Seay is inaccurate: Seay died in Hertford County in 1803, several years before the building of Woodbourne (1808) in Roxobel, the Pugh-Griffin House (1812) in Woodville, and the Sally-Billy House (1810) in Halifax County.[11]

Sideboard, Hope Plantation, Windsor, North Carolina

The sideboard illustrated in figure 26 is, perhaps, the latest example attributed by previous scholars to the WH group. This attribution is largely based on the perceived relationships between the blocking on that object and that on the preceding desk (fig. 1). The blocking is an early stylistic feature that, combined with an otherwise standard neoclassical form, makes the sideboard unconventional in American furniture. Many of the characteristic WH-group structural features are absent: drawer bottoms are set in dadoes rather than flush-nailed to the bottoms of drawer sides; no pins secure stile and rail joints; and the conventionally applied veneer is not found on any other WH pieces. In addition, the profile of the blocking on the desk is more refined, with fillets canted rather than parallel to the façade as on the sideboard, and the execution very different. These departures have led to the supposition that the sideboard was made by a journeyman in the WH shop who had trained elsewhere or in a second shop influenced by the WH group.

Newbern and Melchor discovered a large inscription on the inner surface of the yellow pine backboard of the sideboard and interpreted part of the writing as the name “Wilmot Peeas” or “Wilmot Seeas,” which they felt might signify a relative of William Seay or one of his unrelated journeymen. They also identified a partially obscured second name as “John Weedo[n]” and noted that the remainder of the inscription was a list of dimensioned boards supplied by one of the two names.[12]

The inscriptions were written in pencil, so here again infrared reflectography served as the best technique for improving legibility (figs. 27, 28). If nothing else, the resulting IR photograph proved that John Weedo[n] was the tradesman who likely provided the lumber. The inscription reads as follows:

6 Walnut Pieces 1 inch Thick

4 Pine ditt 3/4 Thick 4 1/2 Wide

1 4 1/2 Wide @ 1/2 Thick

John Weedo—

Misinterpreting “Walnut Pieces” as “Wilmot Peeas” in normal light is understandable: an old graphite inscription does not stand out on an oxidized wood surface. Illegibility obscured not only the lettering but also the entire context of the inscription, and it is obvious that the presence of two oversize words beginning in sweeping capital letters was highly suggestive of a proper name. The use of infrared reflectography makes the words and context of this graphite inscription very clear.

Curiously, the sideboard is the sole example from the WH group examined thus far that bears a pencil inscription. The name “John Weedo[n]” (or a similar variation) does not appear in any known documents from the Roanoke River basin. The sideboard has no provenance, and it may date considerably later than previously thought: the torus moldings of the top and base edges, if original, indicate a classical revival influence. While it would be imprudent to remove the sideboard from inclusion in the WH group at this time, these observations and the fact that its construction differs in many ways from other WH pieces raise questions. Additional research should be conducted to explore other possible origins for this unusual sideboard.

Tympanum Board, Private Collection, Atlanta, Georgia

The final item examined in the study is a tympanum board from a case piece in the WH group (fig. 29)—one of four documented examples (three on intact pieces) featuring a federal eagle clutching Masonic emblems. The elaborate eagle is ebonized, incised, and inlaid with putty. It holds the scales of justice in its beak, a Masonic square, compass, and sunburst in its right talons, and a level in its left. Above the eagle is a banner of fifteen stars, probably representing the states of the Union at the time the pediment was constructed, dating it between 1792 and 1796. On either side are the relief-carved, ebonized tendrils and leaves typical of the WH group, here laid out in a more delicate pattern than usual and outlined in white. The bead and ogee moldings of the scrolls are also ebonized, as are the ground and central star motif of each pinwheel roundel.

REPORTED INSCRIPTION: “HASKETT” IN CHALK, REVERSE OF TYMPANUM BOARD

Technique: Cross-polarization Followed by Black-and-White Conversion and Digital Filtration in Adobe Photoshop

A large chalk inscription is present on the back of the typanum in probable late eighteenth-century script, approximately 16 inches long and 3 inches high (fig. 30). The walnut was apparently sealed with varnish or a pigmented wash before the inscription was made, and portions of the writing are worn, smudged, and difficult to read against the dirty and yellowed coating.

Newbern and Melchor interpreted the first marks of the inscription as the sketch of an eagle and the surname that follows as “Haskett,” reading the final double letters, although made with open loops, as crossed to form a double “T.” They associate the inscription with Jesse Haskett, a Perquimans County man they suggest was living in Roxobel in the mid-1790s working as a journeyman for William Seay. Haskett, they argue, likely ornamented the pediment.

To evaluate this interpretation, this study employed cross-polarization followed by black-and-white conversion and additional processing in Adobe Photoshop. This enhanced legibility to some extent, though some parts of the inscription remain unclear. Additional imaging with UV fluorescence revealed no additional information.

The first mark of the inscription is very faint (fig. 31). It does not appear to be the sketch of an eagle, as no chalk lines representing a head, beak, or body are present. The mark consists of two mirror-image arcs, similar to those in the letter “H,” but differences with the more clearly legible “H” in the surname introduces uncertainty to this interpretation. The arcs overlap near their midpoints in the first mark, whereas they remain apart in the surname “Haskell,” joined only by the crossbar. Moreover, the “H” in the surname has additional flourishes. Compared with other examples of period script, the first initial could also be interpreted as an “X.”

Imaging indicates the surname is probably “Haskell,” as no chalk is present to indicate that the final double “l” was crossed to form a double “t” (fig. 32). More writing is present: at least four smaller letters slope upward from the upper right corner of the “H” in “Haskell,” suggesting a first name also beginning in “H,” such as “Harry” or “Harvy.”

Does the name “H [or X] Haskell” identify a maker, either the decorator of the tympanum or the maker of the entire pediment? The size of the lettering, its location, and the chalk used to inscribe it all suggest this is possible, but it remains far from certain. Three known WH pediments have eagles below fifteen stars, indicating a relatively short time period for their construction. It is possible that these objects, and others like them, were fabricated nearly simultaneously: the inscribed name, possibly that of the individual who commissioned the piece, may have been a useful means to distinguish otherwise similar objects.

The benefits of imaging in the examination and analysis of markings on furniture are clear. Imaging techniques enhance legibility, improve the accuracy of interpretations, and help prevent unfounded speculation. This study was limited to six objects in the WH group, but inscriptions reputedly found on three of those pieces—the Hope Plantation secretary press, the Chrysler Museum of Art secretary press, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts block-front desk—were the foundation for Newbern and Melchor’s attribution. Imaging showed that two of these objects do not bear Seay’s name and that his only signature on a piece of furniture almost certainly denotes ownership or use rather than authorship. As was the case when John Bivins published The Furniture of Eastern North Carolina, there is insufficient documentary and physical evidence to attribute the WH group to any maker. The richness, diversity, and unique character of the group remain intriguing. The mystery continues.

Appendix

Imaging Techniques and Equipment

Following is a brief discussion of the equipment used during the course of this project. For more detailed information, the authors recommend Jeffrey Warda, ed., The AIC Guide to Digital Photography and Conservation Documentation (Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2011). This book presents a range of technical information in a concise, understandable format and includes a number of imaging techniques not used in the foregoing study. There are also numerous informative websites for photographers interested in cost-effective approaches to multispectral imaging, such as Ben Lincoln’s www.beneaththewaves.net/Photography.

Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI)

RTI is a computer-based means to compile two-dimensional images into a format that enables a three-dimensional study of an object’s surface. The technique is usually conducted using standard photography and a single, movable light source. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) employed a Canon 5D Mark 2 and a handheld flash to examine the incised names on the Hope Plantation secretary press (figs. 7, 8) and the zigzag scratches on the lid support of the VMFA desk (figs. 21, 22). While RTI can be performed using a consumer-model digital camera, the VMFA’s full-frame sensor Canon ensures optimal quality, resolving extreme detail and providing sharp images with very little distortion.

Cross-polarization

This visible-light technique can be used with any digital camera to control specular and diffuse reflections. Minimizing or eliminating these reflections enhances contrast and saturation, distinguishing various features on a surface. A linear polarizing film is placed in front of the light source and a circular polarizing filter on the camera lens; the polarizer on the camera is rotated perpendicular to that of the film for maximum extinction of glare. Cross-polarization photos of the VMFA desk (figs. 16, 17) and the Hope Plantation secretary press (fig. 11) were made using a studio flash filtered using a Rosco #7300 neutralizing linear polarizing film and a B+W Circular Pol-E filter on a 50megapixel 4-shot Hasselblad H4D50-MSRTI (www.bhphotovideo.com). Cross-polarization photos of the Chrysler Museum secretary press (fig. 14) and the WH eagle tympanum (figs. 31, 32) were made using a Nikon D70 and the same polarizing filters as above.

Cameras and Filters for Reflected Infrared and Reflected Ultraviolet Photography

Digital camera sensors are sensitive to the full spectrum of light, visible and invisible. This makes them ideal for multispectral imaging but presents problems in the production of standard visible-light images because of the interference of the invisible portion of the spectrum, particularly the infrared. Manufacturers have gradually increased the internal filtration of the invisible portions of the spectrum, such that no current consumer digital cameras are useful as purchased for multispectral imaging. In addition, both infrared and ultraviolet light present a focusing problem when working with standard lenses. While special lenses permit the focusing of infrared and ultraviolet light in the same plane as visible light, they tend to be very expensive to produce. Consequently, most multispectral photographic systems are costly and serve a very limited professional forensic market.

Fortunately, there are numerous options available for those interested in conducting infrared and ultraviolet photography, employing either used equipment or new cameras converted for use in IR and UV photography. The cameras and light sources used during the course of this project follow.

(1) Sony “Nightshot” feature: For basic infrared images, older Sony digital cameras with a “Nightshot” feature (discontinued after the A100 series) are a simple solution requiring no added filters. With “Nightshot” engaged, the camera’s internal infrared-blocking filter is removed from the light path. The feature was designed as a point-and-shoot means to take images in near darkness, not specifically as an IR technique, so the resulting image is a hybrid of available visible and infrared light. Though there is no flexibility to the technique (aperture and shutter speed are fixed), photos taken carefully in “Nightshot” mode can often reveal as much information as a pure reflected infrared photograph. The IR photograph of the Hope Plantation stair riser (fig. 25)was taken using a Sony Cybershot F717 in “Nightshot” mode and standard tungsten photo lamps.

(2) Fuji FinePix S3 UVIR: Fuji manufactures multispectral cameras that take infrared and ultraviolet photographs when used with the appropriate filters. The infrared photograph of the Hope Plantation sideboard inscription was taken using a Fuji FinePix S3 UVIR, a camera discontinued before 2010 and now supplanted by the company’s IS Pro UV-IR digital SLR. The FinePix s3 has a full-frame sensor with 12.3 megapixels. The spectrum is roughly 350 to 1000 nanometers (nm) (from the UV-A to near infrared). It has a Nikon lens mount and requires the use of filters for the desired imaging technique. The camera allows considerable flexibility in settings to achieve optimal exposures. The Hope sideboard inscription (fig. 28) was revealed using standard tungsten photo lamps and an infrared filter from Edmund Optics with a cutoff below 830 nm (www.edmundoptics.com/optics/optical-filters/bandpass-filters). To take the photo, the camera was first manually focused with no filter present. The filter was then added and focus adjusted over several trial exposures to achieve a single good image.

(3) Nikon D70: The Nikon D70, discontinued only a few years ago, can take good photographs in both infrared and ultraviolet portions of the spectrum without modification, as Nikon’s internal blocking filter remained relatively weak until fairly recent generations of its consumer digital SLRs. Like the Fuji FinePix camera, filters are necessary for both infrared and reflected ultraviolet photography. Because the internal filters block some of the desired wavelengths, the camera requires longer exposures and/or wider aperture settings than the Fuji FinePix camera. Unpublished reflected ultraviolet photographs of the “W” on the Chrysler Museum’s secretary press were taken using a Nikon D70 with a B+W 403 ultraviolet bandpass filter (blocking all visible light) (http://diglloyd.com/articles/Filters/spectral-B+W-403.html) stacked with a LDP LLC X-Nite CC1 filter (www.maxmax.com/axnitefilters.htm) to block out infrared light, ensuring only reflected UV-A light reached the camera’s sensors. The camera was initially focused without filters using the auto-focus feature. While auto-focus was still locked, the filters were placed on the lens, then the lens was set for manual focus. As with the Fuji FinePix, focus was manually adjusted over several trial exposures to achieve a single good image. Reflected infrared photos taken with the Nikon D70 during this project (not shown here) used both a Hoya R72 (cut-off at 720 nm) and a B+W 093 (cut-off at 830 nm). Light sources for both infrared and reflected UV photography are described below.

(4) Converted digital SLR cameras: For optimal results using a recently made digital SLR camera, one can convert an off-the-shelf camera into a UV/IR camera either by using a purchased conversion kit to replace the internal UV/IR filters or by sending the camera to one of several businesses that perform the conversions for a fee (see www.lifepixel.com or www.maxmax.com/IRCameraConversions.htm). If a new camera is converted, it is important to know that the conversion will void a manufacturer’s warranty. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts uses a converted Canon 5D Mark 2, a 21-megapixel camera that has been modified to see and record both infrared and UV wavelengths of light. The reflected infrared range is ~715–1200 nm; reflected UV, 350 nm–400 nm. This camera was used to search for reported ink markings on the VMFA desk using reflected ultraviolet light photography (figs. 18 right and 19 right), employing filters equivalent to those described above in section 3.

Lighting for Reflected Infrared Photography

Cameras that have weak infrared filtration or have had internal filters removed are very sensitive to infrared and near-infrared light. Both sunlight and the tungsten light traditionally used for photography contain sufficient light in the near-infrared wavelengths to ensure adequate exposure. Indeed, hot spots (areas of overexposure to near-infrared wavelengths) are a bigger problem than underexposure, whether the light source is the sun or tungsten filaments. Standard tungsten photo lamps were used for all visible light, cross-polarized light, and reflected infrared photographs.

Lighting for Reflected Ultraviolet Photography

Unlike UV-fluorescence photography, which produces best results when the light source is restricted to ultraviolet wavelengths (usually UV-A, approximately 350–400 nm), reflected ultraviolet photography can be performed using daylight or any other visible light source that includes the ultraviolet portion of the spectrum. Lighting must be relatively intense, as the filters (described above in Nikon D70) are visually opaque, and exposures can often take several seconds. Tungsten lighting cannot be used as it contains virtually no ultraviolet component. High-pressure mercury vapor lamps and xenon lamps are suitable but can be very expensive. The reflected ultraviolet images in figures 18 and 19 were taken using a Broncolor Unilite strobe flash with a Broncolor UV attachment (www.bron.ch/broncolor/products/lamps/showproduct/unilite=1600). As a less-expensive alternative, surfaces can be lit using daylight or, if indoors, two fluorescent fixtures, each containing an 18-inch 15-watt UV-A fluorescent tube (Sylvania F15 T8 G13 BL368 - Quantum 368 nm, available at www.barbizonspecialtylighting.com). These specialty tubes provide much more UV-A light than commonly available BLB (black light blue) fluorescent tubes. While all fluorescent tubes are considerably less intense than mercury vapor lamps, they work well for close illumination of inscriptions, which generally cover a small surface area.

Enhancing Images in Adobe Photoshop

All of the techniques described above benefit from processing in Adobe Photoshop (www.adobe.com/Photoshop), an essential tool for enhancing images in order to extract as much visual information as possible. Its capabilities are greatest when images are captured and processed in RAW format, although images can be considerably improved even after conversion to high-resolution TIFF files.

It is generally useful to convert images to black and white. Among other things, this addresses the distracting appearance of reflected infrared and reflected ultraviolet photographs, which come from the camera with a reddish or a purplish cast, respectively. Rather than converting an image directly to grayscale, which discards all color information, it is often best to use the black-and-white conversion tool, which preserves color information on separate channels, permitting one to adjust the relative intensities of particular colors even after the image is converted. When processing a cross-polarized image of chalk on wood, for instance, reducing the intensity of the red and yellow channels, which generally make up the color of the wood background, invariably improves contrast between the chalk and the wood.

Next, “levels” are adjusted to improve the overall exposure and the relative intensity of lights and dark shades, a step that once again enhances contrast. Finally, adjustments are made using the “brightness and contrast” sliders, adding a final measure of contrast to distinguish the elements of an inscription from its background.

John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1988), pp. 291–322.

Thomas R. J. Newbern and James R. Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker: A Southern Mystery Solved (Benton, Ky.: Legacy Ink Publishing, 2009). North Carolina Archives, Raleigh, CR.010.101.7, folder 1774–75. Thomas Sharrock Estate Papers, Bertie County Record of Estates, State Archives of North Carolina, CR.010.508.90. Newbern and Melchor also propose that William Seay descended from a family of woodworkers, citing a June 4, 1768, court record documenting an agreement by James Seay (possibly an uncle of William Seay) to apprentice his orphaned nephew Abraham Seay, then two years old, as a “house carpenter” (Bertie County Court Minutes, 1763–1771). They failed to note the subsequent formal indenture document signed by James Seay and dated June 26, 1768, in which he agreed to teach Abraham Seay “the art and calling of a cordwainer” (State Archives of North Carolina: Apprentice Records CR.010.101.7, folder 1768).

Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, p. 59. The staff of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts informed Newbern and Melchor of their findings before WH Cabinetmaker: A Southern Mystery Solved went to press. Susan J. Rawles, Assistant Curator for American Decorative Arts, email message to James Melchor, May 11, 2009: “I am sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but our staff of conservators and photographers have all spent a great deal of time examining and re-examining the WH block-front desk in an effort to identify period signatures and markings—unfortunately, to no avail. While they have examined your photos against the evidence of the object and can, in a few instances, acknowledge variations in the surface areas akin to markings, they cannot confirm that those markings are signatures—as opposed to variations in the wood born of salt or humidity or scratches, etc. Consequently, we are unable to provide you with the images you requested. I sincerely hope that . . . other physical evidence and historical documentation on the cabinetmaker and patron . . . will more than compensate for this turn of events.” Individuals who examined the desk include consulting conservator F. Carey Howlett; staff conservators Kathy Gillis, Carol Sawyer, and Bruce Suffield; chief conservator Stephen Bonadies; assistant curator Susan Rawles; and photographer Katherine Wetzel.

George Fisher, The Instructor, or American Young Man’s Best Companion Containing Spelling, Reading, Writing and Arithmetic (Worcester, Mass.: Isaiah Thomas, 1786).

Reflectance Transformation Imaging is a product of Cultural Heritage Imaging, a nonprofit corporation. Software for capturing and viewing RTI images is available at no cost at http://culturalheritageimaging.org/Technologies/RTI/.

John E. Tyler, “A History of the Tyler Family of Bertie and Hertford Counties, North Carolina,” manuscript, p. 18, archives, Historic Hope Foundation. The manuscript discusses the marriage of Elizabeth Rutland Tyler, widow of John Tyler, to a “Mr. Seay.” This is probably William Seay, as it explains his 1800 guardianship of Peggy Andrews, the orphaned daughter of Stephen Andrews and Celia Tyler. Celia was the daughter of Elizabeth Rutland Tyler, making Peggy Andrews the orphaned step-granddaughter of William Seay (Stephen Andrews estate papers, State Archives of North Carolina, CR010.508.1). The 1800 federal census for Hertford County, North Carolina, lists William Seay as heading a household of four white people, one male over forty-five (Seay), one female over forty-five (probably Elizabeth Rutland Tyler), one female sixteen to twenty-five (probably Celia Tyler Andrews, widow of Stephen Andrews), and one female under ten (probably Peggy Andrews).

Frank L. Horton. “The Work of an Anonymous Carolina Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 101, no. 1 (January 1972): 169–76. See also Virginia Museum of Fine Arts objects file for the desk, acc. no. 1949.11.17.

Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, pp. 58–63.

Ibid., p. 243; Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry Abrams for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997), pp. 534–36.

Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, pp. 173–81.

Conversation with David Serxner, Historic Hope Foundation. See the entry for Jeremiah Bunch in North Carolina Architects and Builders: A Biographical Dictionary, http://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/. Bivins, The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, p. 64. Thomas Sharrock and son Steven witnessed a will at Hope Plantation while the house was under construction. Seay is listed as “William Seay dcd” in a June 13, 1803, document transferring his guardianship of Peggy Andrews to John Andrews (Stephen Andrews estate papers, State Archives of North Carolina, CR010.508.1). Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, pp. 104–13, 120–26, 230–36. The authors reported finding the inscription “Seay Sharrock” on the drawer bottom of a built-in cupboard at the Pugh-Griffin House, supposed evidence of a collaboration by William Seay and the Sharrock family of cabinetmakers. The drawer bottom was not included in this study because the house was built after Seay’s death.

Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, pp. 229–31.