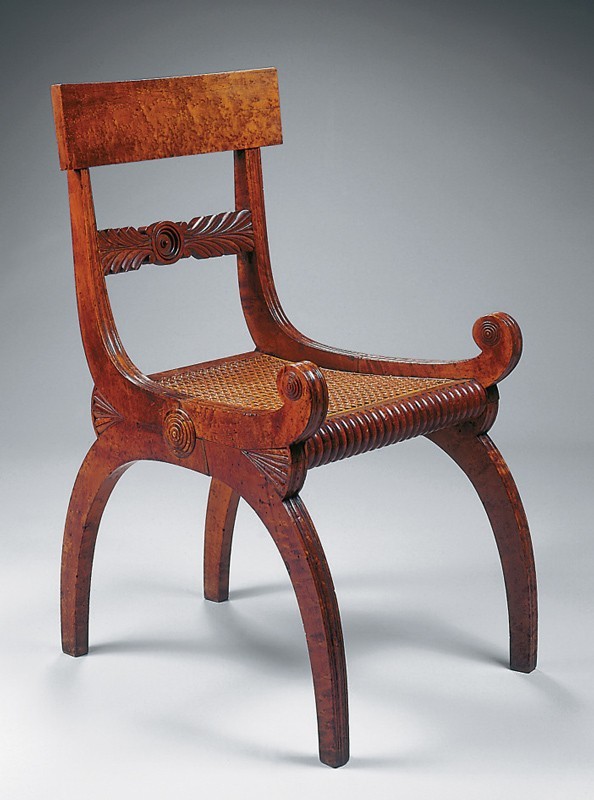

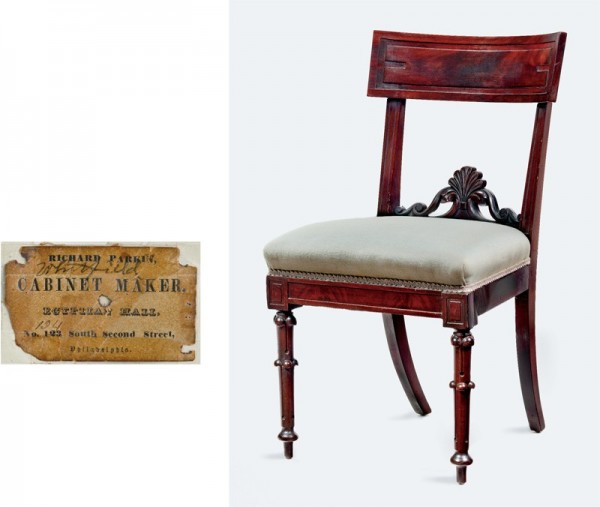

Side chair attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Walnut and walnut veneer with tulip poplar. H. 32 1/4", W. 18", D. 18". (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of Walnut Street between Third and Fourth Streets, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1830–1840. Watercolor on paper. 18 3/4" x 33 1/2". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.) Cook and Parkin’s shop is in the middle of the block on the left. John Hancock and Company occupied the building on the left corner. As was the case with Cook & Parkin, Hancock’s business was in the central business district. Only the most successful firms could afford to operate at that location.

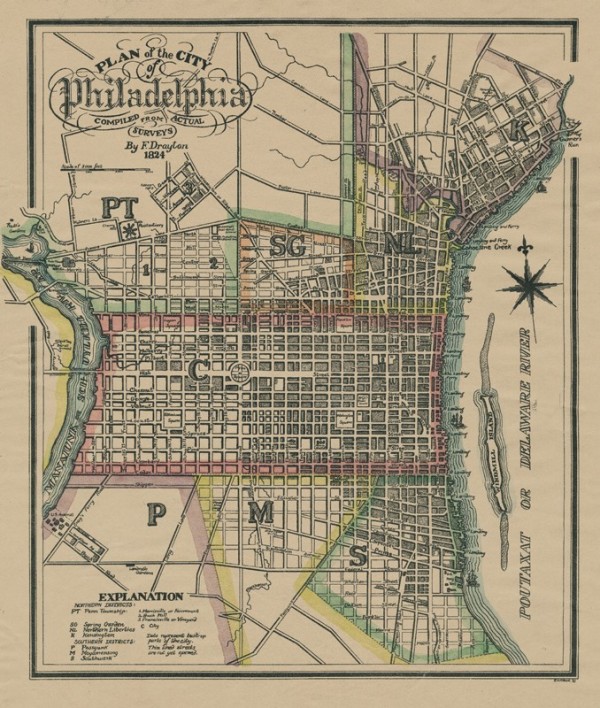

Joseph Drayton, Plan of the City of Philadelphia, published by H. C. Cary and I. Lea, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1824. Hand-colored engraving on paper. 15 1/2" x 17 194". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.) This detail shows the central business district and the locations of businesses maintained by Cook & Parkin, Thomas Cook, and Richard Parkin.

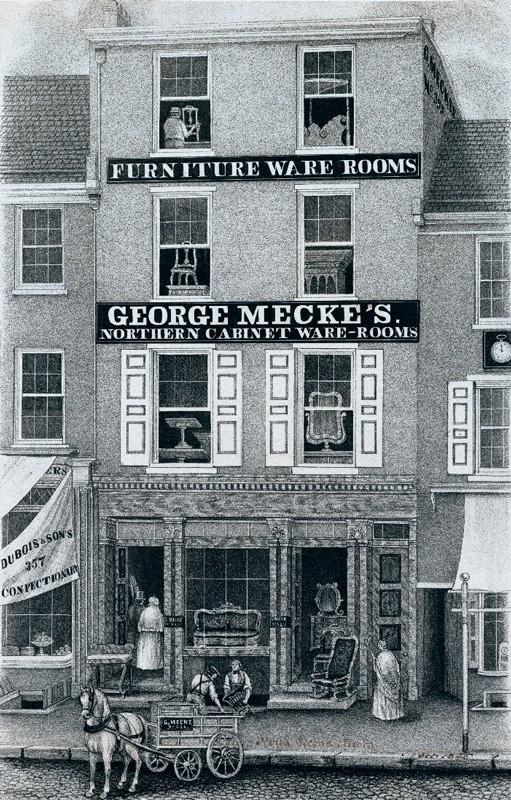

W. H. Rease, engraver, “George Mecke Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer,” published by Wagner and McGuigan, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1846. Lithograph. 20" x 13". (Courtesy, Arader Galleries, Philadelphia.) This lithograph shows the shop of cabinetmaker George Mecke at 355 North Second Street. The building is a typical Philadelphia row house with a cabinet shop in the front.

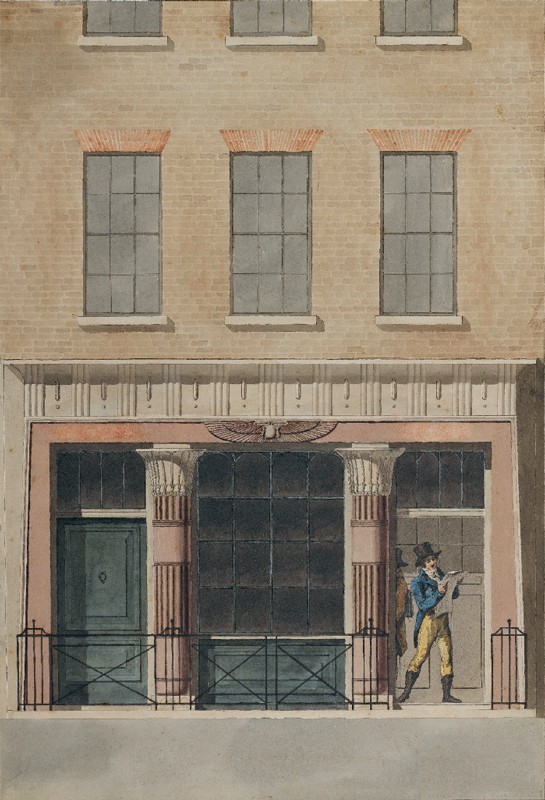

A Shop Front in the Egyptian Style (Courtesy, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.) The façade of Parkin’s shop may have resembled this storefront in the Egyptian style. In addition to a new façade, the redesign of Parkin’s shop opened the show room to the street, making it more inviting and conducive to display.

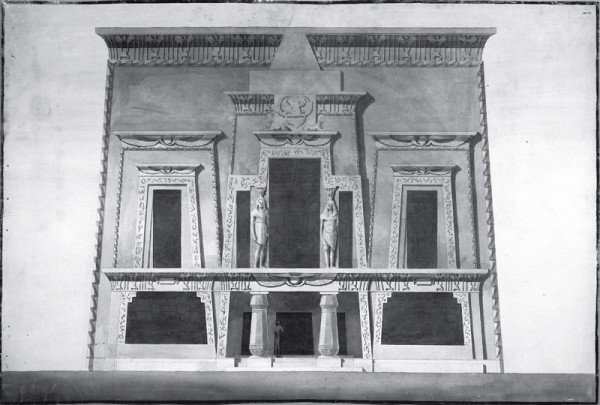

Egyptian Hall, designed by Peter F. Robinson for George Bullock, Piccadilly, London, 1811–1812. (Courtesy, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.)

Sideboard bearing the label of Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1819–1824. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine, tulip poplar, and oak. H. 63 1/4", W. 98 1/2", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art; purchase fund with exchange funds from gift from estate of Margaret Anna Abell, gift from Mr. and Mrs. Warren Wilbur Brown, gift of Jill and M. Austin Fine, bequest of Ethel Epstein Jacobs, gift of William M. Miller and Norville E. Miller II, Bequest of Leonce Rabillon: Bequest of Philip B. Perlman; and Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Louis E. Schecter, BMA 1989.26; photo by Mitro Hood.)

Detail of the label on the sideboard illustrated in fig. 7.

Design for a “large library or writing-table flanked with paper presses, or escrutoirs,” illustrated in pl. 11 in Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807).

Detail of a Pergamene capital on the sideboard illustrated in fig. 7.

Photograph showing the dining room of the Anthony Wayne House, Easttown Township, Paoli, Pennsylvania, 1930–1940. The sideboard has later brass drawer pulls.

Pier table bearing the stenciled label of Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825–1830. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine and tulip poplar; marble. H. 40 3/4", W. 47 3/4", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Johnny Miller.) A molding with a cavetto frieze of similar profile is illustrated in pl. 1 in the Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices (1828).

Detail of the stenciled label on the pier table illustrated in fig. 12.

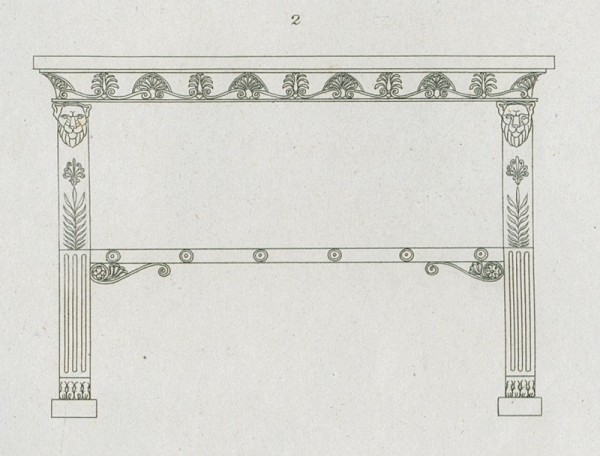

Design for a table illustrated in pl. 12 in Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807).

Detail of the pier table illustrated in fig. 12, showing the dovetails used to attach the pilasters to the bottom board.

Detail of the pier table illustrated in fig. 12, showing the stepped miters of the boards above the frieze.

Detail of the pier table illustrated in fig. 12, showing the construction of the base.

Pier table possibly by Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1824–1833. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar; marble. H. 38", W. 38", D. 20". (Courtesy, President James Buchanan’s Wheatland, Lancaster, Pennsylvania; photo, Lancaster County Historical Society.)

Center table bearing two stenciled labels of Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1824–1833. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine and ash; marble. H. 29", Diam. 38". (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.; photo, Richard Goodbody.)

Design for table à thé illustrated in pl. 515 in Pierre de la Mésangère, Collection de meubles et objets de goût (Paris, 1821). (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.)

Drum table attributed to Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1824–1833. Rosewood and rosewood veneer with unidentified secondary woods. Dimensions not recorded. (Allison Boor and Jonathan Boor, Philadelphia Empire Furniture [West Chester, Pa.: Boor Management, 2006], p.129).

Photograph showing the second-floor parlor of the George Eveleigh House, 39 Church Street, Charleston, South Carolina, ca. 1927.

Mechanical easy chair attributed to Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1824–1833. Mahogany with white pine. H. 46 1/2", W. 27 1/4", D. 29". (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left arm of the mechanical easy chair illustrated in fig. 23.

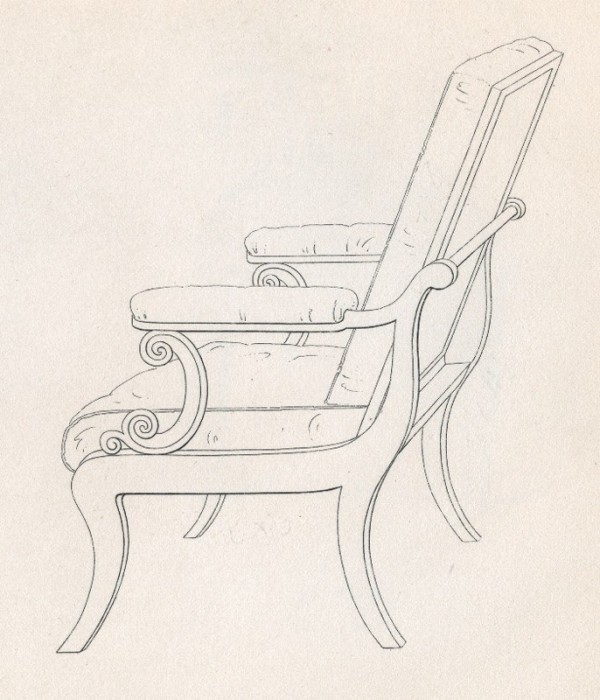

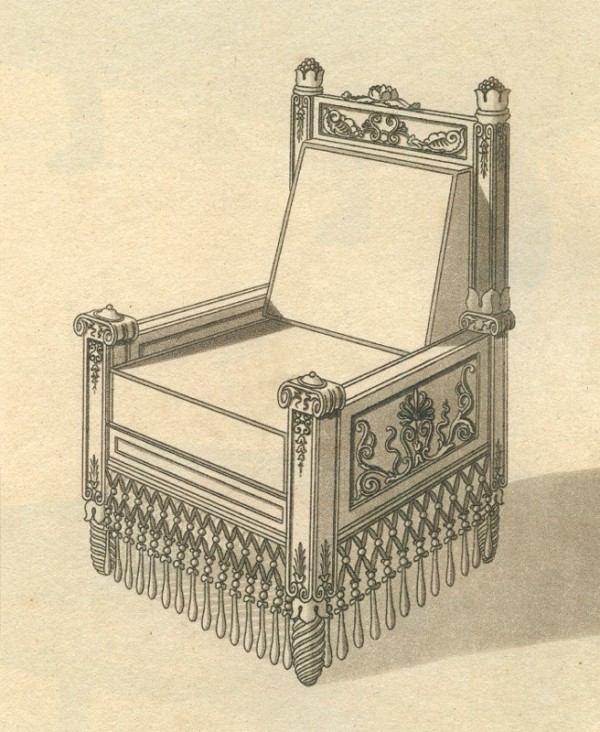

Detail of “Chairs with inclining backs” illustrated in pl. 10 in Thomas King, Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (London, 1829).

Detail of the crest of the mechanical easy chair illustrated in fig. 23.

Detail of a sideboard table illustrated in pl. 45 in Thomas King, Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (1829). (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.)

Thomas Cook, extension dining table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1836. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine and oak. H. 28 1/4", Diam. 85 1/2" (with large leaves). (Courtesy, Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia.)

Side chair, possibly Thomas Cook, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1830. Curly or figured maple. H. 33", W. 19", D. 22". (Courtesy, Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia.)

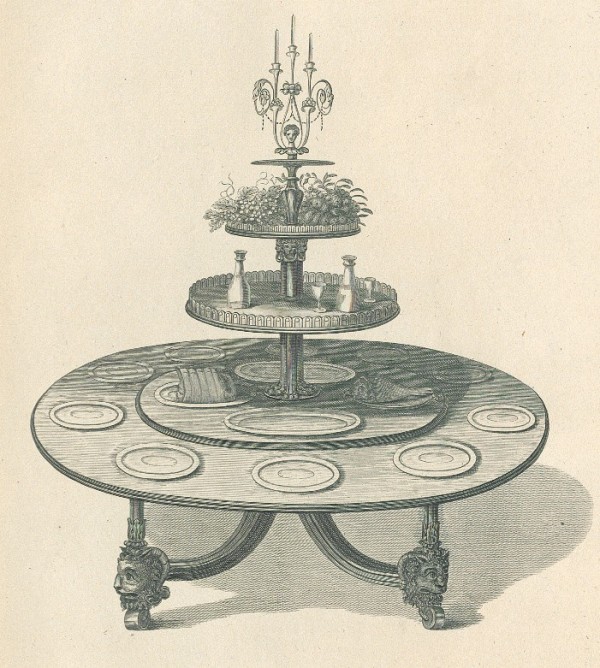

Design for a dining table in pl. 31 in Thomas Sheraton, Designs for Household Furniture (London, 1812).

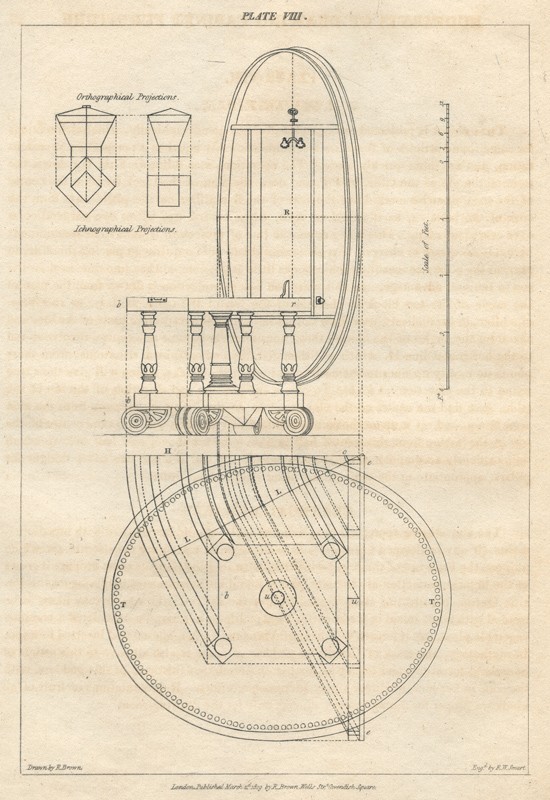

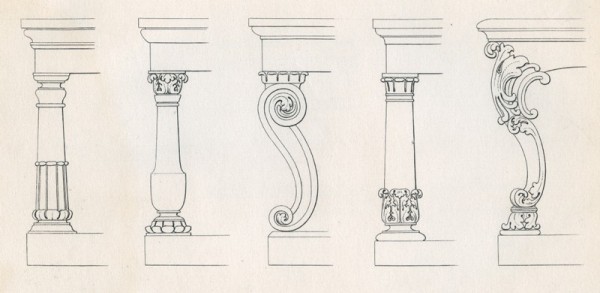

Design for a dining table in pl. 8 in Richard Brown, The Rudiments of Drawing Cabinet and Upholstery Furniture (London, 1820). (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.)

Designs for “Supports for Sideboard Tables” illustrated in pl. 17 in the supplement of Thomas King, The Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (London, 1829). (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.) The center design relates to the supports of the table illustrated in fig. 28.

Richard Parkin, washstand, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1833–1840. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine; marble. H. 37", W. 26", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Neal Auction Company, New Orleans, La.)

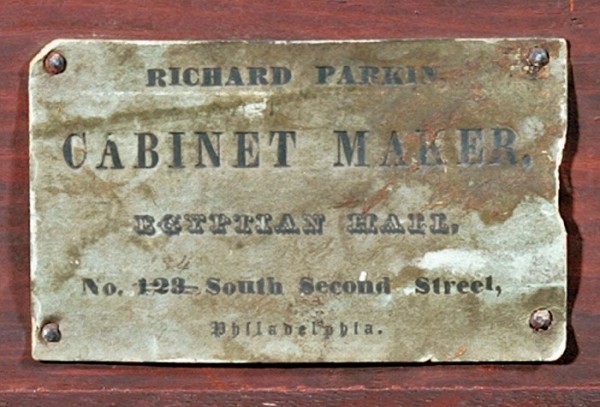

Detail of the label on the washstand illustrated in fig. 33.

Carter Hall, Millwood, Virginia, 1814.

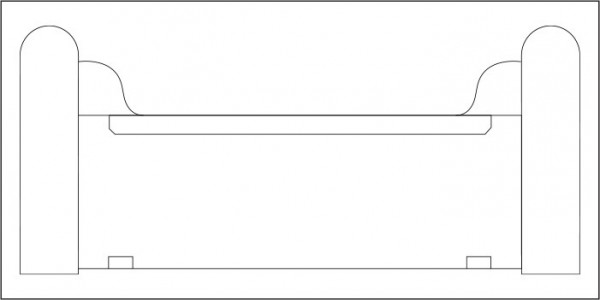

Sofa bearing the stenciled label of Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1830. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with unidentified secondary woods. H. 35", W. 89", D. 24 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Bob Godwin, RGB Photography, Santa Fe.)

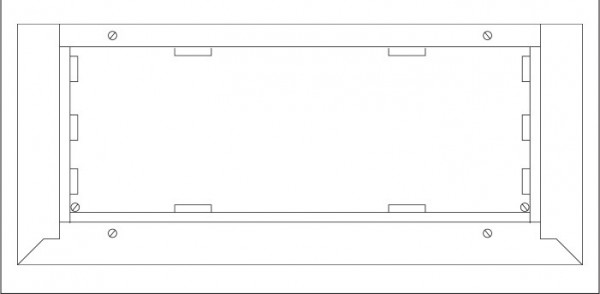

Wardrobe bearing the stenciled label of Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1827–1833. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with unidentified secondary woods. H. 84 1/2", W. 80 3/4", D. 23 1/4". (Landis Valley Village and Farm Museum, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commision; photo, Richard Sexton.) This example has five stenciled labels.

Wardrobe attributed to Cook & Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1827–1833. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, maple, and maple veneer with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 87 1/2", W. 81 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Charles and Rebekah Clark, Woodbury, Connecticut; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bookcase attributed to Cook & Parkin or Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825–1835. White pine; paint. H. 102", W. 71 3/4", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Carlton Hobbs, LLC, New York.) Demilune panels like those on the cornice occur on other furniture attributed to Cook & Parkin (see figs. 37, 38). The beaded Romanesque panel of the base is a larger version of that on the door of the washstand illustrated in fig. 33. The pediment is virtually identical to that of the wardrobe illustrated in fig. 38, and both designs relate to the “large library or writing-table” shown in pl. 11 in Thomas Hope, Household Furniture (1807) (fig. 9).

Dressing table attributed to Cook & Parkin or Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1829–1835. Maple and maple veneer with unrecorded secondary woods. H. 67", W. 48", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Gates Antiques, Ltd., Midlothian, Virginia.) The design of this object may have been inspired by “A Toilet” illustrated in pl. 92 of Thomas King, The Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (1829). The demilune cutouts relate to the panels on the case pieces illustrated in figs. 37–39, and the large flat bosses on the mirror brackets are identical to those on the scrolls of the couch, chairs, occasional table, and sideboards illustrated in figs. 45, 51, 56, 59, and 60.

Side chair from a set of at least eleven with one bearing the label of Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Mahogany, black walnut, and mahogany veneer with walnut. H. 32", W. 18", D. 18". (Landis Valley Farm Museum, Lancaster, Pennsylvania; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Elements of these chairs may have been inspired by designs in several pattern books, but the overall composition is original and unlike any published chair design. The form and crest rail relate to a chair illustrated in pl. 194 in Pierre de la Mésangère, Collection de muebles et objets de goût (Paris, 1805), and the legs relate to those on chairs shown in pl. 143 in George Smith, Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (London, 1828), and pl. 18 in Thomas King, The Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (1829).

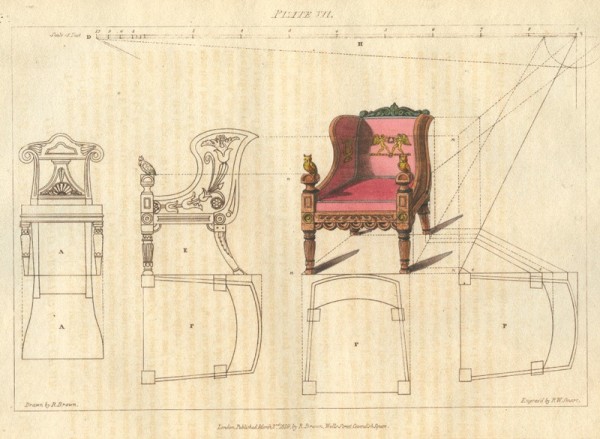

Design for a library chair illustrated in pl. 7 in Richard Brown, The Rudiments of Drawing Cabinet and Upholstery Furniture (1820). (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin.) The chair on the left may have been inspired by a George Bullock design as indicated by the Wilkinson Tracings (fig. 43).

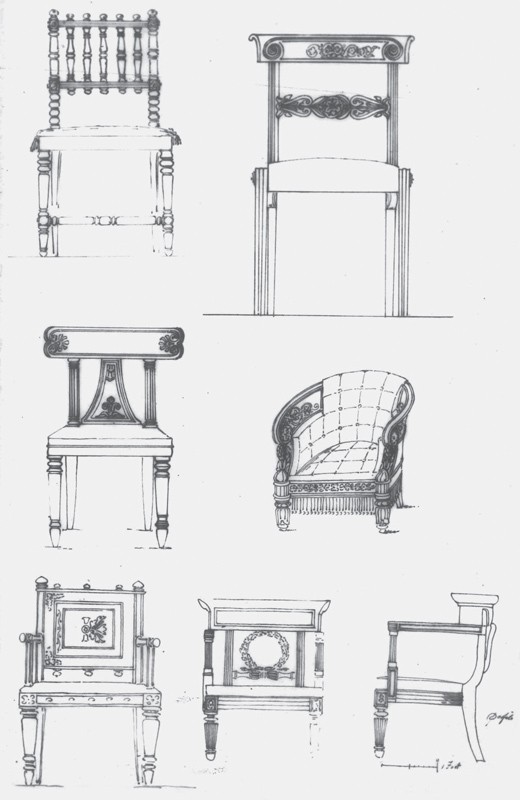

Chair designs on p. 8 in “Tracings from Thomas Wilkinson from Designs of the late Mr. George Bullock, 1820.” (Courtesy, Birmingham Museums Trust.) Several sets of Philadelphia chairs have details similar to those depicted in these “tracings.” The example on the left of the second row has a back design that relates to those on chairs documented and attributed to Parkin.

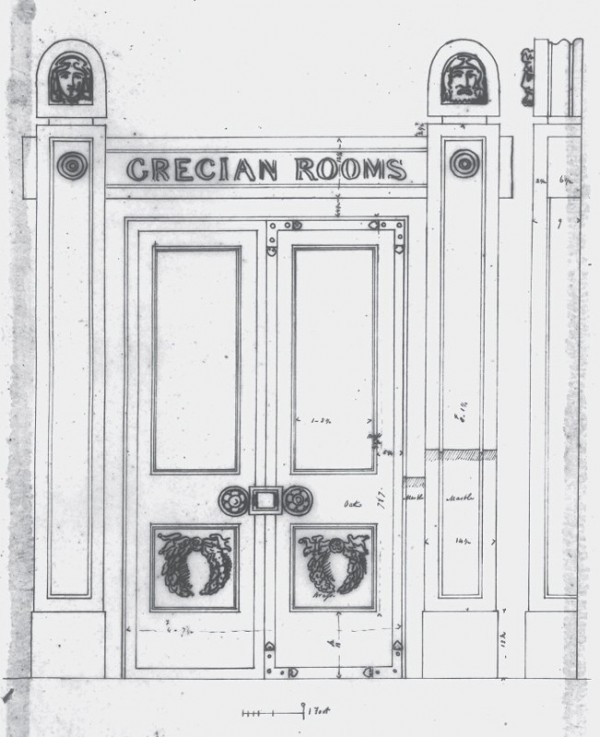

Drawing depicting the entrance to George Bullock’s Grecian Rooms at Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, London, 1812–1814. (Courtesy, Birmingham Museums Trust.)

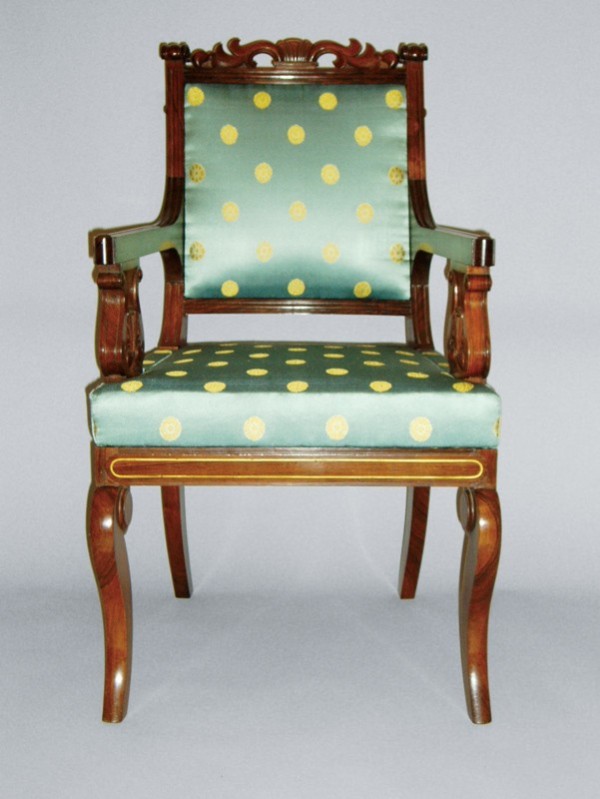

Armchair attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1833–1840. Rosewood and rosewood veneer with unrecorded secondary woods. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Johnny Miller.) This chair is one of three identical armchairs and six related chairs, including the example illustrated in fig. 51.

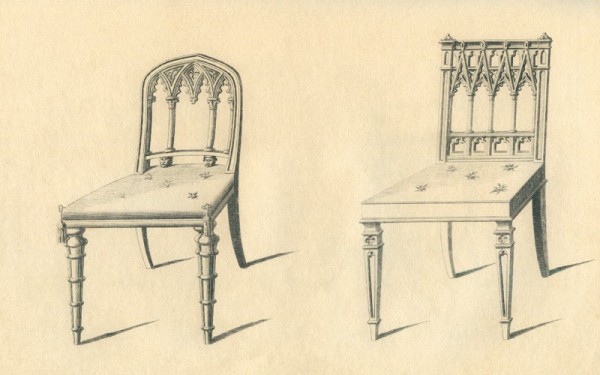

Designs for “Drawing Room and Dining Room Gothic Chairs” illustrated in pl. 143 in George Smith, Guide (1828). (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin.) The chair on the left has legs similar to those on seating documented and attributed to Richard Parkin.

Design for a “Drawing Room State Chair” illustrated in pl. 58 in George Smith, Household Furniture (London, 1808). (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin.)

Side chair attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with ash. H. 33 1/8", W. 17 3/4", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Andrew Jones and George Celio, 1996.)

Side chair attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar. H. 33 1/2", W. 17 1/2", D. 21". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.)

Side chair attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and walnut with white pine. H. 35 1/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 20 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Rosewood and rosewood veneer with ash. H. 35 1/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Rosewood and rosewood veneer with ash. H. 35 1/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

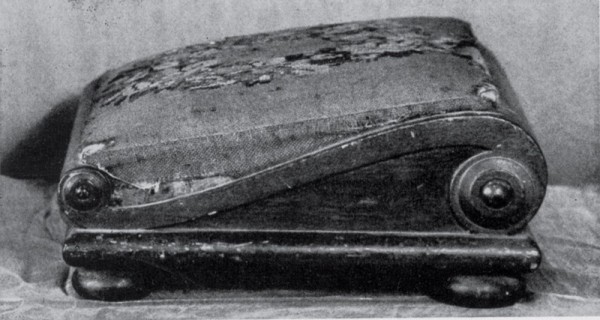

Footstool from a pair bearing the label of Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Woods not identified. (William MacPherson Horner Jr., “Some Early Philadelphia Cabinetmakers,” Antiquarian 16, no. 3 [March 1931]: 76.) Parkin’s design is similar to that of a footstool illustrated in Rudolph Ackermann, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, and Manufactures, ser. 1, vol. 10 (October 1813): 232, pl. 25. This publication was very influential, particularly in Philadelphia.

Side chair, possibly from the shop of Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with ash. H. 33", W. 19", D. 20". (Courtesy, Carswell Rush Berlin, Inc.; photo, Richard Goodbody.) This chair is from a set of at least twelve seating forms. Its crest rail is related to that on the side chair illustrated in fig. 49, and its faceted legs are similar to those on the armchair illustrated in fig. 55.

Armchairs attributed to the shop of Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1834–1840. Walnut and walnut veneer. Secondary woods not recorded. H. 35", W. 19 1/4", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Johnny Miller.)

Occasional table bearing the Egyptian Hall label of Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1835–1840. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine. H. 29 1/2", W. 44", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

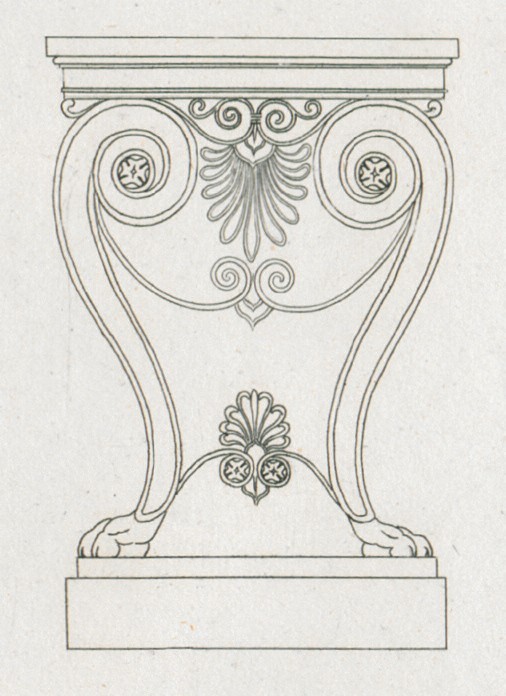

Design for a table illustrated in pl. 12 in Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807). This form is referred to as an “occasional table” in Peter Nicholson and Michael Angelo Nicholson, The Practical Cabinet Maker, Upholsterer and Complete Decorator (London, 1826), George Smith, Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1828), and Thomas King, The Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (1829).

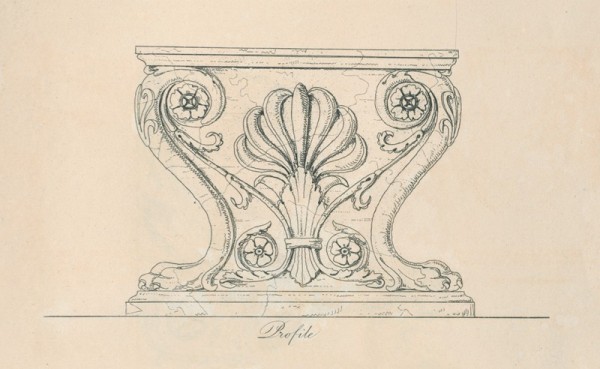

Profile of an “Antique Seat of Parian Marble in a Chapel near Rome” in Charles Heathcote Tatham, Etchings Representing the Best Examples of Ancient Ornamental Architecture; Drawn from the Originals in Rome (London, 1799). Several published designs can be traced to this etching.

Sideboard attributed to Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1835. Rosewood and rosewood veneer with mahogany, white pine, tulip poplar, and cedrela; marble. H. 40 3/4", W. 60 1/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976-17-1.)

Sideboard probably by Richard Parkin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1835. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine; marble. H. 43", W. 60", D. 24". (Courtesy, Rosedown Plantation Historic Site, St. Francisville, Louisiana.) Made for Rosedown Plantation and invoiced by Anthony G. Quervelle, exhibiting distinctive flat bosses.

David Bodensick, sofa table, Baltimore, Maryland, 1833. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 29 1/8", W. 57 3/4 (open)", D. 26". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society, 1990.3.) The table is inscribed, “Made by / David Bodensick From Baltimore / And Sold By Mr. Cook & Perkins / Philadelphia, PA.”

The names of Thomas Cook and Richard Parkin are not typically listed alongside those of Anthony G. Quervelle, Joseph B. Barry, Michel Bouvier, and other renowned Philadelphia furniture makers of the classical period. Yet, at the time, that is precisely the company Cook and Parkin kept. Niles’ Weekly Register’s review of the Franklin Institute’s second annual exhibition of manufactures in 1825 listed “beautiful and otherwise remarkable specimens of manufacture” by the city’s leading cabinetmakers, including “White, Bouvier, . . . Quervyl [Quervelle], . . . [and] Cook and Parkins [sic].”[1]

The stenciled and printed trademark of Cook and Parkin’s firm and the printed label of Richard Parkin are found on some of the most avant-garde pieces of American classical furniture, but many unmarked objects of comparable importance have escaped the attention of scholars and collectors. Thanks to the recent discovery of a pair of side chairs, one of which is illustrated in figure 1, Parkin’s name can now be associated with seating in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Yale University Art Gallery. These new findings have provided the impetus to reexamine the lives and work of Cook and Parkin, to raise questions about their training and design influences, and to return them to their former place in the firmament of Philadelphia’s nineteenth-century cabinetmaking community.

Richard Parkin was born in England circa 1787, died in Philadelphia on September 16, 1861, and was buried in the American Mechanics Cemetery on Islington Lane at Twenty-Seventh Street. Family tradition maintains that he emigrated from Sheffeld, England, and it is likely that he served his apprenticeship before coming to the United States. John and Hannah (Padley) Parkin of Sheffeld had a son named Richard in 1791, but no definitive connection between that family and the émigré cabinetmaker has been established. Similarly, a family of Parkins arrived in Philadelphia from Liverpool on the ship Lancaster in September 1819, but the passenger manifest does not mention anyone named Richard. The cabinetmaker’s absence in the 1810 and 1820 federal censuses suggests that he arrived shortly before his name began to appear in Philadelphia directories in partnership with Cook in 1819.[2]

On February 6, 1825, Parkin married Clara Stevens (1801–1875) in a civil ceremony performed by Philadelphia mayor Joseph Watson (1784–1841). Parkin may have had a business connection to Watson, who worked as a lumber merchant before taking office in 1824. Richard and Clara had six children. The eldest, Thomas, was born in Philadelphia in 1827, followed by Sarah, born in 1831, twins Clara (d. 1860) and Anna in 1833, Henry (d. 1885) in 1835, and Richard Jr. two years later. All three sons became cabinetmakers, but none of their work has been identified.[3]

Thomas Cook’s naturalization application, dated July 16, 1819, describes his trade as “cabinetmaker” and states that he was born in Yorkshire, England, on May 12, 1789, emigrated from London, and arrived in Philadelphia on April 29, 1817. His wife, Ann (ca. 1786–1871), also was born in England, and it is likely that they came to America together. Thomas was listed at 26 Bank Street in Dock Ward in the 1820 Philadelphia city directories. He and Ann had one child, a daughter, Mary (ca. 1823–187?). Cook retired from business at the age of forty-nine, younger than many of his contemporaries. He seems to have accumulated enough capital to invest in real estate, like his competitors Bouvier and Quervelle. Beginning circa 1835, Cook devoted his time to the acquisition of investment property and bought at least eight such lots. The 1860 U.S. census recorded his wealth at $10,000 and Parkin’s at $1,000, a disparity that might be explained by the number of children they each raised. Cook died on May 13, 1868, at seventy-nine, after thirty-one years as a “gentleman,” leaving his investments to his daughter, Mary Stellwagen, and the income from rents and dividends from securities to his wife for her lifetime. Two years after his death, the 1870 census valued his widow’s net worth at $15,000 and his daughter’s at $24,000.[4]

Cook & Parkin

Thomas Cook and Richard Parkin were among the first generation of English cabinetmakers born during the classical revival of the late eighteenth century. Their birth dates nearly coincided with the publication of George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788), the first broadly available design book in the classical taste, and their apprenticeships likely began just before the publication of Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet Dictionary (1803). The latter book and Thomas Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807) helped shift the focus of classical design from Robert Adam’s abstract interpretations of ancient designs to furniture based on archaeological models. As furniture historian Joseph Aronson suggests, pattern books also heralded the final step in an “evolution from cottage handicraft through the Factory System and the Industrial Revolution . . . the ultimate division of functions . . . aiming for greater output and efficiency to meet the demands of expanding markets and wealth.” During their apprenticeships, Cook and Parkin would have developed specialized hand skills while learning how to design furniture, create working drawings, and exploit the new industrialized systems of production. By the time they arrived in Philadelphia, both men were capable craftsmen with clear ideas about what furniture in the classical taste should look like and how it should be made.[5]

The Philadelphia directory listed Cook & Parkin first as “Chair Makers” at 26 Bank Street in 1819, then as “Cabinet Makers” at 56 Walnut Street from 1820 to 1833 (fig. 2). Cook also appeared alone, listed as a cabinetmaker at 4 Fromberger’s Court in Paxton’s Directory, in 1819, and in some directories he and Parkin were listed jointly as “Chair Makers” as late as 1824. In 1829, while maintaining a business at 56 Walnut Street, both men began working at separate addresses, Parkin at 94 South Third Street and Cook at 7 Pear Street. Four years later, they dissolved their partnership when Parkin moved to Egyptian Hall, a building at 134 South Second Street, leased from cabinetmaker Joseph Barry; Cook remained at 56 Walnut Street.[6]

Cook and Parkin’s separation in 1829 may have been an expedient way to gain production space while maintaining 56 Walnut Street as a showroom. Scholar Deborah Ducoff-Barone has noted that the central business district, which encompassed that area of Walnut Street, was a prestigious location and the epicenter of Philadelphia’s furniture making industry (fig. 3). Rents were high, and only the most successful and well-capitalized firms could afford to set up and maintain businesses there. All but two of the cabinetmaking enterprises mentioned in the October 15, 1825, issue of Niles’ Weekly Register were located within two blocks of Cook and Parkin’s Walnut Street address and Parkin’s shop on South Second Street (after 1833): Quervelle at 126 South Second Street (1825–1848), Bouvier at 91 South Second Street (1825–1844), Charles H. White at 109 Walnut Street (1815–1854), and John Jamison at 75 Dock Street (1815–1829). These shop masters understood that location was key to securing wealthy local patrons and attracting foreign buyers and entrepreneurs engaged in the coastal trade.[7]

Cook maintained a business at 56 Walnut until 1837, when he retired from the cabinetmaking trade. City directories referred to him as a “gentleman” until 1860, eight years before his death. Parkin’s forty-one-year career was even more extensive, among the longest of any Philadelphia cabinetmaker of the period. Similarly, Cook and Parkin’s fourteen-year partnership was longer than 90 percent of all cabinetmaking businesses recorded in Philadelphia between 1800 and 1840.[8]

In the absence of documentation, the size of Cook and Parkin’s manufacturing business can be extrapolated through comparison with other firms. Barry advertised “employment for six journeymen cabinetmakers” while working at 134 South Second Street, a building he subsequently leased to Joseph Aiken and then to Richard Parkin. While at that location, Aiken’s shop had “five turning lathes and a number of workbenches.” During Barry’s tenancy, 134 South Second Street was a shop and wareroom as well as a dwelling, but advertisements for the sale of Aiken’s stock in 1829 indicate that the space was entirely dedicated to selling furniture. It is reasonable to assume that the workforce and scope of Parkin’s business was larger than Barry’s and at least as large as Aiken’s, but smaller than that of Cook and Parkin.[9]

Maintaining a large business between 1819 and 1833 was a notable accomplishment for Cook & Parkin because that period was as difficult and unstable as the American cabinet trade had ever known. Their firm survived two major depressions, damage to the local economy caused by President Andrew Jackson’s struggle with the Second Bank of the United States, wild fluctuations in the price of mahogany, and worker strikes precipitated by two technological advancements—the introduction of the steam-powered lathe and the circular saw.

In 1826 confrontations between master cabinetmakers and journeymen forced a revision of piecework prices and, by extension, the cost to produce various furniture forms. Working with a three-man “Committee of Journeymen,” the “Committee of Employers,” composed of Parkin, White, and Jamison, issued a broadside detailing the “per centage upon start prices of jobs” in the 1826 reissuing of the 1811 Journeyman Cabinet and Chairmaker’s Pennsylvania Book of Prices. Parkin’s leadership position on the committee reflects his high stature as a cabinetmaker as well as Cook & Parkin’s importance as an employer of numerous journeymen.[10]

Like many of Philadelphia’s most successful firms, Cook & Parkin consigned furniture to agents in southern cities and ports in the Caribbean and South America. Outbound coastal manifests for the port of Philadelphia beginning in 1823 recorded multiple shipments by the firm to Charleston, South Carolina; Savannah, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Petersburg, Virginia; and St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. As was the case with Cook & Parkin, cabinet- and chairmaking firms that exported furniture tended to be among the most long-lived in Philadelphia.[11]

Egyptian Hall

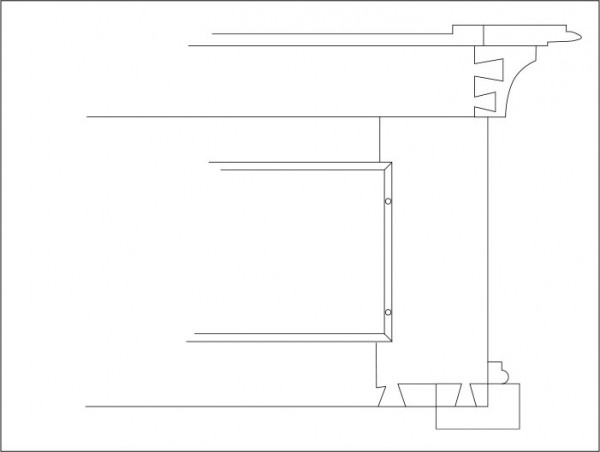

In 1809 Barry built and occupied a row house at 134 South Second Street. Typical of many Philadelphia town houses (figs. 2, 4), this two-storey brick building had a showroom on the street side of the first floor and shop space at the back and on the second floor. Barry may have eliminated the wall that usually separated the first-floor rooms, since his space—22 by 80 feet—was much longer than most warerooms. Furniture warerooms like Barry’s typically had large windows so clients and pedestrians could view the stock-in-trade. His featured “two plain Bulk windows glass 12 by 20 inches & a square head door with a fan sash.”[12]

When Barry relocated his business in 1825, he rented the building at 134 South Second Street to the Pennsylvania Society of Journeymen Cabinetmakers for use as a wareroom. Aiken took over the lease in 1827, followed by Parkin six years later. During Parkin’s tenancy, the front door and bulk windows were replaced with “2 large cased posts & 3 folding sash front doors” framed by “4 large Square boxed open Egyptian Columns . . . crowned by a large Carved Human Bust, Square Capt . . . surmounted by a plain Egyptian entablature and cornice,” thereafter being known as Egyptian Hall (fig. 5).

Parkin’s occupancy during and after this redesign advertised his status as a leader of fashion and a beacon of new taste. The façade must have created a striking architectural tableau juxtaposed with Benjamin Latrobe’s Bank of Pennsylvania on South Second Street, which was the first Greek revival building in the United States. Both buildings were testaments to the era’s fascination with ancient cultures.[13]

Parkin’s wareroom was not the first or the only Philadelphia furniture shop to undergo refurbishment during this period, but the modifications made by him and his landlord Barry, were exceptionally elaborate and uniquely “Egyptian,” which explains Parkin’s reference to that taste on his label and trade card. It is likely that both men were familiar with Egyptian Hall, the widely known showroom maintained by English cabinetmaker George Bullock (1782/83–1818) in Piccadilly, London (fig. 6). In 1811 Barry traveled to that city and Paris to buy furniture and other “fashionable articles,” which he offered in the Aurora General Advertiser the following year—“the newest and most fashionable Cabinet Furniture, superbly finished in the rich Egyptian and Gothic style.” The construction of Egyptian Hall began in 1810 and would have been open when Barry was in London.[14]

Parkin remained at Egyptian Hall for about sixteen years until relocating to Lewis Street below Thompson, where he was joined in 1853 by his son Thomas, who died unexpectedly in 1855. From 1856 to 1860 Parkin operated a steam sawmill, first at 399 Broad Street, then at 683 North Broad, and finally at Spring Garden, where he was joined by another son, Richard Jr. In 1860, which was Richard Sr.’s last directory appearance, their firm was referred to as Richard Parkin & Son.[15]

The Furniture of Cook & Parkin

On December 10, 1819, Cook & Parkin submitted their earliest known bill to Zaccheus Collins (1764–1831) for a mahogany breakfast table valued at $25.00.[16] Collins was a Philadelphia merchant, botanist, and member of the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Society of Natural Sciences. Earlier in his career, he was a partner in his father’s business, Stephen Collins & Son. They bought and sold a variety of goods, including Windsor chairs. Zaccheus’s patronage shows that Cook and Parkin developed a reputation among elite members of Philadelphia society shortly after establishing their firm.[17]

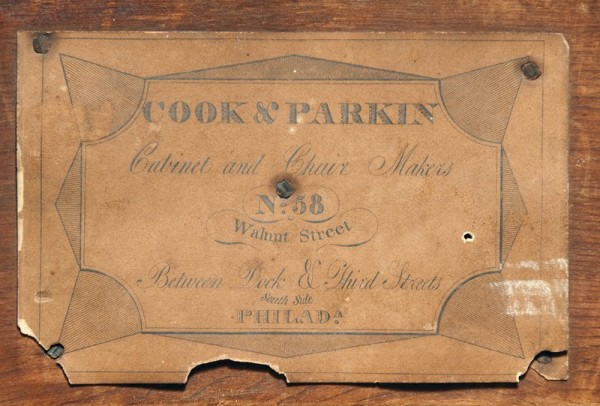

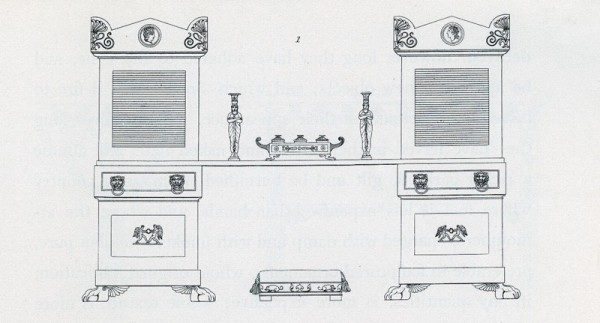

One of the most significant examples of Cook & Parkin’s work is a sideboard bearing the firm’s engraved paper label: “COOK & PARKIN / Cabinet and Chair Makers / No. 58 / Walnut Street / Between Dock & Third Streets / South Side / PHILAD” (figs. 7, 8). The sideboard probably dates to the early 1820s, because Cook & Parkin are described as “cabinet and chair makers” in directory entries before 1824 and only as “cabinetmakers” thereafter. The stenciled ink text on other labels refers to “Cabinetware” and “mahogany seating.” The design of the sideboard was adapted from the “large library or writing-table flanked with paper presses, or escrutoirs” illustrated in plate 11 in Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (fig. 9). Many cabinetmakers were inspired by Hope’s designs, but American copies of his archaeologically based designs are rare.[18]

Among the many exceptional characteristics of this sideboard is the use of Pergamene capitals surmounting the pillars flanking the upper cabinets (fig. 10). This variation on the Corinthian capital, identified with the ancient city of Pergamum near the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, has palm fronds issuing from a basket of acanthus leaves. Examples of this capital are extremely uncommon and not used in London work until the late 1820s, when they were adapted for table base designs by George Smith and Peter and Michael Angelo Nicholson. There are two plausible explanations for the use of Pergamene capitals on Cook & Parkin furniture made prior to the appearance of those capitals in London design books. They may have seen the example Lord Elgin brought to England with the Elgin marbles before they emigrated, or they had access to Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Della magnificenza ed architettura de’ Romani (1761).[19]

A sideboard documented to Cook & Parkin and visible in a 1930s photograph of the dining room in the house of Anthony Wayne in Easttown Township, Paoli, Pennsylvania, is more in keeping with conventional Philadelphia classical styles (fig. 11). Isaac Wayne purchased the piece in 1823, when he was redecorating the house and beginning his first term as a U.S. senator. On August 7 of that year, his brother-in-law and agent William Atlee wrote:

I fear not that the article will please you, for I think it handsome, this the opinion of a good workman who accompanied me it is pronounced of good workmanship & the best materials & well seasoned stuff. . . . I have however exceeded your limit as to price, ten dollars, but I believe in the end you will be a gainer—I will challenge this City to produce a better, or one so gentile for that sum.[20]

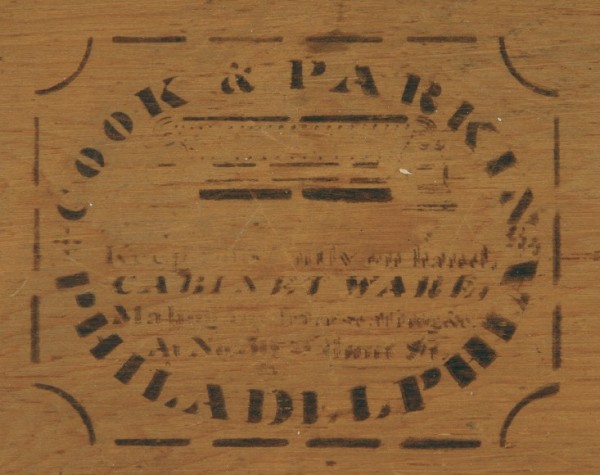

A slightly later pier table with Cook & Parkin’s stenciled label (figs. 12, 13) has a cavetto frieze rather than a flat and shaped frieze like those often used by Quervelle and other Philadelphia cabinetmakers who worked in the classical style. Published examples include the mantelpiece and table shown in plates 10 and 12, respectively, in Hope’s Household Furniture (fig. 14) and an “Egyptian Chimney-Front” illustrated in Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions, and Politics.[21]

The pilasters of the pier table are attached to the bottom board with two dovetails (fig. 15), and the molded boards of the frieze above have stepped miters at the front corners (fig. 16). By contrast, many Philadelphia pier tables of this period have pilasters attached with a single dovetail and cornice boards joined at the front corner with conventional miters, lap joints, or blind dovetails. Even more distinctive is Cook & Parkin’s incorporation of a dust board under the frieze (fig. 17).

The labeled pier table is related to three unmarked examples similar to the one illustrated in figure 18. Each has a cavetto frieze below a Gothic astragal, or knife-edge molding; identical stenciling at the center and corners of the frieze; and the same bronze mounts. Although the construction of these objects differs, it is possible that all are from Cook & Parkin’s shop. Structural variations are common in the work of large cabinetmaking enterprises, which typically employed several apprentices and journeymen.[22]

Cook and Parkin’s entrepreneurial spirit and embrace of avant-garde design are reflected in their decision to offer faux-gilded metal furniture. An article in the Franklin Journal and American Mechanics’ Magazine of 1827 referred to an artimomantico bedstead among the stock-in-trade in the firm’s “cabinet wareroom.” Although the journal erroneously reported that a gentleman from Leghorn (Livorno), Italy, had recently invented that alloy, the article correctly stated that artimomantico had been used for buttons and tableware sold by Louis Vernon Company, a Philadelphia mercantile firm specializing in luxury goods. Metal bedsteads became popular in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, largely because they were perceived as being more hygienic and insect-resistant than wooden examples. J. C. Loudon described the virtues of cast-iron bedsteads, dining tables, sideboards, and seating (hall, lobby, and porch chairs) in his Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture and Furniture (1833) and noted that iron bedsteads “are to be found in houses of people of wealth and fashion in London; sometimes even for best beds.” The artimomantico bedstead offered by Cook & Parkin six years earlier was at the vanguard of this new fashion in domestic furniture.[23]

Contemporary Philadelphia cabinetmakers viewed Cook & Parkin as leaders in style and technological innovation. After Joseph Aiken and Company received the right to manufacture Daniel Powles’s patent bed in 1827, the firm solicited Cook & Parkin’s endorsement along with that of Joseph Barry, William Brown, Michel Bouvier, Lewis Costens, John Jamison, Jacob Jarret, Anthony G. Quervelle and Charles H. White. All of these men were at the summit of the cabinet trade in early nineteenth-century Philadelphia.[24]

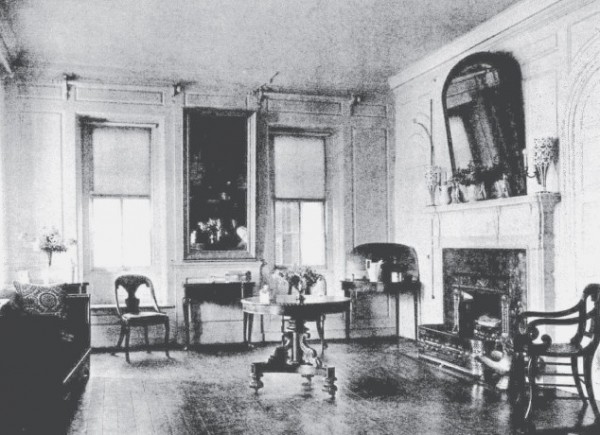

The center table illustrated in figure 19 may have been inspired by Pierre de la Mésangère’s 1821 design for a table à thé published in his Collection de meubles et objets de goût (1802–1830) (fig. 20). The center table has two ink stencils reading, “COOK & PARKIN / Cabinetware / Mahogany seating / No. 56 Walnut St. / Philadelphia” and depicting what appears to be a sofa. Three nearly identical, marble-top center tables are known, one bearing a stencil like those on the example shown here, as well as a rosewood drum table with an identical base and a radial inlaid top (fig. 21). A sixth center table of the same design but with a wooden top, was in the second-floor parlor of the George Eveleigh House at 39 Church Street, Charleston, South Carolina, when it appeared in the Octagon Library of Early American Architecture (1927) (fig. 22). By family tradition, the table can be traced to 1875, when Richard Maynard Marshal (1845–1894) purchased the Eveleigh House from Mary Ann Love, widow of Charles Love. Whether the table was in the house when Marshal acquired it or was inherited from his father, Alexander W. Marshal, it is likely that it had been in Charleston since the late 1820s. Cook & Parkin consigned furniture to Charleston agents Thomas H. Deas in 1825 and James Dick in 1830.[25]

A mechanical chair can also be attributed to Cook & Parkin’s shop based on its arm supports (figs. 23, 24), which relate directly to the acanthus-carved scrolls on the center tables (see fig. 19). Thomas King’s Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (1829) shows several mechanical and easy chairs, including examples with “inclining backs” (plate ten in the supplement) and construction features identical to those of the attributed chair (fig. 25). The crest on the Cook & Parkin chair may also have been inspired by details in one of King’s illustrations. The S-scrolls, leafage, and anthemion are similar to those on the back on the “Sideboard Table” shown in plate 45 (figs. 26, 27). Variations of this design also appear on the bottom edge of the tablet back on side chairs from Parkin’s shop (see figs. 50–52) and on a “Drawing Room Chair” illustrated in plate 3 of Smith’s Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide.

American mechanical chairs are exceedingly rare. A few Boston examples are known, including one bearing the partial label of Boston upholsterer William Hancock (act. 1820–1835). In 1833 his brother’s upholstery firm, John Hancock and Company, Philadelphia, placed an advertisement in DeSilver’s City Directory and Stranger’s Guide, touting “easy chairs of every description.” John’s advertisement also featured an engraving of a Grecian couch with a tubular drawer at one end identical to a couch illustrated in William’s advertisements and on his label. John’s advertisement and his 1835 estate inventory reveal that “Self Acting Chairs” and “Recumbent chairs” (easy chairs with seats that slide forward as the back reclines) were among his stock-in-trade as well. His estate inventory also reveals that Cook and Parkin owed him $77.95 and $188.40, respectively, and that Cook Thomas was one of the appraisers. Because the Hancock brothers were in the mechanical chair business, this financial connection and the close proximity of John Hancock’s and Cook & Parkin’s shops suggest that Hancock commissioned and upholstered the mechanical chair illustrated in figure 23. Upholsterers and decorators often ordered seating from cabinetmakers and chairmakers.[26]

Consumers often bought furniture directly from upholsterers, decorators, cabinetmakers, and other suppliers, including those in distant cities. Maria Hull Campbell of Savannah, Georgia, commissioned furniture from Cook & Parkin or Cook working independently while visiting Philadelphia. The firm had shipped furniture to Savannah during the 1820s, and it is likely that their products had developed a good reputation among her family and friends. In 1830 Maria wrote her friend George Jones Kollock (1810–1894) in Philadelphia, complaining about a repair made to a wardrobe she had purchased earlier:

I requested to put a “ketch” on my wardrobe, similar to your Aunts, & showed him that, which he promised to do. He put a hook instead—and in attempting to hook the wardrobe, the hook flies off—This has always been the case. But now the wood has shrunk so much, that neither lock nor hook is of any use—for the doors do not meet. I must trouble you to ask [Cook & Parkin] . . . to send me a ketch . . . & I will get it fixed I hope by a Cabinet maker in this place.[27]

Campbell’s dismay at the inadequately seasoned wood of her wardrobe does not seem to have shaken the loyalty other Savannah clients felt to Cook, nor did his high prices dissuade them. In August 1831 Dr. Phineas Miller Kollock (1804–1872) wrote his brother and agent George:

I am very much surprised . . . concerning the sofa—Aunt Harriet did not give more than $50.00 for both of hers exclusive of cushions, & I cannot imagine how these last can cost more than $15.00 or $20.00—If you cannot however, procure a Sofa of the description I mention (which I do not think Cook could have understood) I will thank you to . . . procure one of any cheaper pattern which Aunt Jones may like—If it will not be giving Aunt too much trouble, I wish you would consult her in regard to every thing which you purchase, inasmuch as the people with whom you have to deal will be very apt to impose upon one whom they may think not much experienced in such matters. In regard to the Sofa, if you cannot do better, I should like a Lounge like those which Aunt used to have in her rooms, which I should suppose were not quite as expensive—Whatever you get, desire the man to keep a particular description of it, as I may at some future period desire to get a match for it—If possible I do not wish the Sofa & cushions to cost more than $50.00.[28]

The following year Dr. Kollock asked his brother to procure

at Cooke’s [sic] a small sized center table, of a size suitable for such a room as Aunt’s front parlor . . . of the best bird’s eye maple, perfectly plain, without black moulding, the pedestal exactly after the pattern of that of my dining tables. Mr. Wm. W. Gordon of this City has one exactly of the description which I wish—I think he purchased it in Philadelphia, probably at Cooke’s [sic], & I think I have understood that it cost about $30.00. I wish you would charge Cooke [sic] to be very sure, that the wood of which he makes the furniture is well seasoned; for the maple furniture which he has sent me has warped in some places, & opened at the joints.[29]

Parkin’s involvement with Kollock’s purchases is ambiguous. What is clear, however, is that Savannah’s climate created problems with furniture purchased by both those patrons and that Cook, probably in collaboration with Parkin, made maple furniture for several prominent Savannah families. Margaret Telfair, a close friend of the Kollocks, ordered a mahogany dining table from Cook in 1836 (fig. 28), which suggests that his shop may have been responsible for the maple pieces owned by her and her brother, Alexander. The latter include a set of eighteen extraordinary curule-base, cane seat, curly-maple chairs (fig. 29), a pair of figured maple Grecian couches, and a bird’s-eye maple center table.[30]

The Telfair table’s masterful design was inspired by plate 31 in Thomas Sheraton’s Designs for Household Furniture (1812) (fig. 30) and plate 8 in Richard Brown’s The Rudiments of Drawing Cabinet and Upholstery Furniture (1820) (fig. 31), and the scrolled supports were derived from those shown in supplementary plate 17 in King’s Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified (fig. 32). Although American cabinetmakers occasionally adapted details from different plates in the same design book, the maker of the Telfair table’s reliance on three design books is highly unusual. This attests to the depth of Cook’s library and knowledge of British classical style and his ability to work within that idiom.

Cook & Parkin’s favorable reputation in the South is further confirmed by Louisiana senator Josiah Stoddard Johnston’s (1784–1833) patronage. On January 16, 1826, Cook and Parkin wrote, “This being the season of the year we have to pay our bills, if you [Johnston] make it convenient to remit us the amount of your bill it would relieve us very much at present $677=00. The bill of the last Furniture was duly paid.” Judging from the amount owed, Johnston must have been one of Cook & Parkin’s most important clients. His debt would have been sufficient to furnish an entire house, not to mention the furniture for which payment had been received.[31]

George Harrison Burwell (1799–1873) of Millwood, Virginia, was also a customer of Cook & Parkin. On December 1, 1831, the firm charged Burwell $455.00 for a dressing table, a set of dining tables, two sofas, a wardrobe, a ladies’ worktable, and a sideboard. The invoice was accompanied by a note indicating that Cook & Parkin had erred in sending Burwell a marble-top basin stand and asked that he send $15.00, which was a 25 percent discount of the retail price.[32] Although the basin stand has not been identified, it may have resembled a marble-top washstand bearing Parkin’s Egyptian Hall label (figs. 33, 34). Burwell’s furniture was intended for Carter Hall, a house on 5,800 acres inherited from his father in 1814 (fig. 35). He redecorated Carter Hall after the death of his first wife and his remarriage to Agnes Atkinson (1810–1885) in August 1831.[33]

A Grecian sofa bearing the stencil mark of Cook & Parkin is roughly contemporaneous with Burwell’s order, and it descended in families living on the north fork of the Shenandoah River near Millwood (fig. 36). Unlike much formal furniture of the age, which was inspired by engravings in English or French pattern books, the sofa’s design is distinctively Philadelphia. Local cabinetmakers who made related sofas with low scrolled backs, shell-shaped armrests, and squat turned legs included Joseph Barry, Charles and John White, and David Fleetwood. Cook & Parkin’s version of this form is as stylish and well made as any of their competitors’ products.[34]

During the late 1820s the “Grecian” or “Plain” style began supplanting the more architectonic French Empire. Inspired by the forms of Greek antiquity and influenced by French Restoration tastes (1815–1830), the Grecian style was sleeker, more streamlined, and more curvilinear than its predecessors. Through the furniture export trade, Cook & Parkin contributed to the dissemination of the Grecian style, which became ubiquitous in American furniture design by 1833.[35]

At the time of their manufacture, the wardrobes illustrated in figures 37 and 38 would have been considered avant-garde examples of the Grecian style. Composed entirely of abstracted geometric forms, Cook & Parkin’s were more streamlined and “modern” than any contemporaneous published designs for that form. With a base price of $30.00, winged wardrobes were the most expensive furniture form described in the Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet Ware (1828). The wardrobe George Harrison Burwell purchased from Cook & Parkin in 1831 cost $65.00.[36]

Design features that occur in later examples of Cook & Parkin’s work, as well as furniture made by Parkin working independently, include the use of distinctive demilune panels (figs. 37-41), large flat bosses with ovolo-molded edges (figs. 40, 41, 46, 52, 53, 57), bosses with prominent convex centers surrounded by ovolo molding (see figs. 50, 53), and a variety of individualistic carved and gilded details (see figs. 1, 39). When any of these details appears alone or in combination on the same object, it is likely that Cook & Parkin or Richard Parkin working independently was the maker.

Furniture by Richard Parkin

A benchmark for identifying seating made by Parkin is a set of eleven chairs (probably at least twelve originally), all labeled “RICHARD PARKIN / CABINET – MAKER / EGYPTIAN HALL / 134 South Second Street / Philadelphia” (fig. 41). Their stay rails are triangular in shape, decorated with a carved anthemion, and surmount the rear seat rails. These features are unique in American seating but have precedents in Brown’s Rudiments of Drawing Cabinet Furniture (fig. 42) and a group of drawings inscribed “Tracings from Thomas Wilkinson from Designs of the late Mr. George Bullock, 1820” (fig. 43). Bullock was an ingenious artist of great renown and influence whose surviving work is unsurpassed in Regency furniture. His innovative use of indigenous material, inlays inspired by native plants and classical designs placed him at the forefront of British cabinetmakers of the period and garnered him important commissions from Sir Walter Scott, the Duke of Atholl, Matthew Robinson Bolton, and the Prince Regent for Napoleon Bonaparte’s residence on St. Helena. Bullock was active during the period when Cook and Parkin served their apprenticeships and worked as journeymen in England. It is likely that both of the future partners were familiar with Bullock’s furniture, an assertion supported by the similarity of chairs attributed to Parkin (fig. 41) and one illustrated in the Wilkinson Tracings. Another chair on the same page (upper right) could be the model for many sets of Philadelphia chairs, both with and without brass inlay (see fig. 43). Cook and Parkin’s apparent knowledge of Bullock’s designs suggests that they may have been the source for some of the Klismos-type chairs popular in Philadelphia throughout the 1820s.[37]

A number of Philadelphia chairs possibly made by Cook & Parkin or Richard Parkin working independently have die-stamped brass inlay, which is significant because Bullock was the most important exponent of Boulle work in English Regency furniture. Side chairs like the Parkin example illustrated in figure 41 indicate that he and Cook were familiar with Bullock’s designs (see fig. 43). Barry’s association with brass inlay can be traced in part to his September 11, 1824, notice in the American Daily Advertiser, where he offered for sale “2 Rich sideboards, Buhl work and richly carved.” Barry would have had the opportunity to study Boulle work while visiting London and Paris in 1811 and may have seen examples of Bullock’s furniture in his Grecian rooms at Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, London, or Liverpool (fig. 44). If Barry was another conduit for Bullock’s designs, stylistic transfer could have occurred through collaboration with Parkin or through journeymen who may have worked for both men. Barry and Parkin are the only Philadelphia cabinetmakers known to have used cross-braces on the back upholstery frames of their chairs (fig. 45).

A pair of side chairs made of highly figured walnut and walnut veneer (fig. 1) provides a link between the set bearing Parkin’s label (fig. 41) and several undocumented chairs in public and private collections. The walnut chairs have legs identical to those on the labeled examples and rear stiles that terminate in stylized Ionic capitals with molded edges and paneled tablets like the chairs illustrated in figure 49. This leg design may have been inspired by a Gothic chair illustrated in plate 143 in Smith’s Guide (fig. 46), and the capitals are similar to those on a “Drawing Room State Chair” shown in plate 58 of his Household Furniture (fig. 47). Parkin is the only Philadelphia cabinetmaker known to have used these capitals, which appear on the chairs illustrated in figures 1, 45, and 50–52.[38]

The chairs illustrated in figures 48–52 have additional features indicative of Parkin’s work. The chair illustrated in figure 50 has large bosses with molded edges attached to the inner and outer faces of the front leg volutes, and all three chairs have small bosses glued to the round corners of the rectangular appliqués on their backs. Bosses similar to those on the chair shown in figure 51 also occur on a pair of footstools bearing Parkin’s Egyptian Hall label (fig. 53).[39]

A side chair possibly from Parkin’s shop (fig. 54) and a related example in maple with ebonized details represent a genre of seating traditionally attributed to Michel Bouvier, yet the turned and faceted legs relate closely to those on a pair of armchairs attributed to Parkin, and the tablet back is nearly identical to that on the chair illustrated in fig. 48. No documented Bouvier chairs share those details.[40]

As the occasional table illustrated in figure 56 suggests, furniture made by Parkin working independently and in partnership with Cook demonstrates a much stronger affinity with Hope’s designs than work by other American cabinetmakers. The design of this object appears to be inspired by a table illustrated in plate 12 of Hope’s Household Furniture (fig. 57), which had its roots in an ancient Roman marble bench drawn and published by Charles Heathcote Tatham in 1799 (fig. 58). The table, which bears Parkin’s label, has scrolled legs, an “Egyptian” marble top, and large flat bosses with molded edges.[41]

An unmarked sideboard with elaborate stenciled decoration may also be from Parkin’s shop (fig. 59). The original owners were probably Charles Henry Fisher (1814–1862) and his wife, Sarah (Atherton), who lived at Brookwood near Germantown, Pennsylvania. The supports of the sideboard are similar to those on the occasional table (fig. 56), the central stencil on its frieze is very closely related to that on the pier table bearing Cook & Parkin’s label (fig. 12), and the piece is decorated with bosses like those commonly used by their firm and Parkin working independently.[42]

The design of the Fisher sideboard is similar to that of an example that Quervelle sold Daniel and Martha Turnbull of St. Francisville, Louisiana, in 1830 (fig. 60). Although the Turnbulls’ sideboard was part of a suite, it bears no relation to the other forms. Indeed, the distinctive turned bosses on the sideboard suggest that Parkin was the maker. Quervelle may have needed assistance to complete his commission in a timely fashion and turned to Parkin, whose shop was less than a block away from his on South Second Street. Collaborations of this type were relatively common in the period. Alternatively, Quervelle could have simply retailed a sideboard made by Parkin, as Cook and Parkin did with a sofa table made by David Bodensick of Baltimore (fig. 61).[43]

Legacy

The furniture made by Thomas Cook and Richard Parkin reflects a thorough knowledge of English and French pattern-book designs and a level of patronage that allowed both men to work at the cutting edge of fashion. Unlike many of their competitors, who copied design book engravings, Cook and Parkin used published details selectively and combined them with their own innovative features. Cook and Parkin’s success at the beginning of the industrial age may have been predicated on size and volume, but it is clear from documented objects that their standard of quality was high and, in the finest pieces, as structurally and stylistically sophisticated as Philadelphia cabinetmakers had to offer. The shops where these men worked no longer stand, but their record of accomplishment remains in the novel and beautiful classical furniture that survives today.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks Gavin Ashworth, Peter M. Kenny, and Alexandra A. Kirtley. I am especially grateful to Deborah Ducoff-Barone for her detailed research on Philadelphia cabinetmakers working in the classical style and Thomas Gordon Smith for his pioneering work on Cook & Parkin.

Niles’ Weekly Register, October 15, 1825, p. 107.

He was listed as being sixty years old in the 1850 census and sixty-eight in the 1860 census (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1869, 14th Ward, 2nd Division, City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, roll M653-1164, p. 405). Parkin’s death notice in the September 18, 1861, issue of the Philadelphia Public Ledger and his city death certificate state that he was seventy-four (Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803–1915, City Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). At the time of his death, Parkin lived at 1336 Brown Street. His gravesite, in Division B, Section 5, lot 30, grave 4, was moved in the mid-1950s, when the cemetery was closed. The location of his remains and those of many family members is unknown. The Sheffield directory listed a Thomas Parkin “cutler” on Scotland Street in 1787, the probable year of Richard Parkin’s birth (Directory of Sheffield [Sheffield: Gales and Martin, 1787], p. 17). The first British census, taken in 1841, listed 531 Parkins in Sheffield (David Hay, A History of Sheffield [Carnegie Publishing, 1998]). The Sheffield General & Commercial Directory listed seventeen Parkins, many of whom were in the steel knife, file, and metals business (Sheffield General & Commercial Directory, edited by R. Gell [Manchester, Eng.: Albion Press, 1825]). The Yorkshire directory of 1817 listed a man named Thomas Cooke and two men named Thomas Parkin in Leeds. All were in the metal business (Directory, General and Commercial of the Town and Borough of Leeds for 1817 [Leeds, Eng.: Edward Baines, 1817]).

For the marriage announcement, see Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, February 8, 1825. Clara’s year of birth is also uncertain. The 1850 census listed her age as forty-five, the 1860 census listed her age as sixty-two, and her death notice in 1875 listed her age as seventy-four. Richard Jr., who would have been about twenty in 1856, was probably working with his father by that date. After Richard Sr.’s death in 1861, Richard Jr. moved in with his older brother Henry at 540 North Twelfth Street. Richard Jr. was listed at 1627 Poplar Street in 1865 and 1866 and as a cabinetmaker at 206 Lagrange Street in 1870 and 1872 (McElroy’s Philadelphia City Directory [Philadelphia: McElroy, 1870]). Henry S. Parkin, Richard Sr.’s second son, is listed separately as a cabinetmaker at 540 North Twelfth Street beginning in 1860 (McElroy’s Philadelphia City Directory). Richard Jr. was living with him at that date but working on Spring Garden Street, north of Broad, in 1865 and 1872. A Sarah Stevens is listed in the 1825 city directory as a widow in Goforth Ally. She was probably Clara’s mother.

Naturalization Petitions for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 1795–1930, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter NARA), Publication M1522, National Archives Catalog ID 573414, compiled 1795–1991, Record Group 21, Pennsylvania 1819. If the birth date on Cook’s petition is correct, he was three years younger than his Philadelphia death notice states. Ann Cook’s death notice is in the April 28, 1871, issue of the Philadelphia Public Ledger. 1820 U.S. Census, Philadelphia Dock Ward, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, p. 26, NARA, roll M33-108, image 37. Philadelphia City Archives, Deeds AM 64-400, 70-411, 47-270, SHF 6-704, GS 35-128, 48-568, RLL 16-473, 25-125. On May 16, 1868, the Philadelphia Public Ledger reported that Cook had died two days earlier at the age of eighty-two, and his city death certificate stated that he was eighty-one (Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803–1915). Cook was buried at Ronaldson’s Cemetery at Tenth and Wharton Streets, but his remains appear to have been removed to Forest Hills, Bensalem Turnpike, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. His will was dated August 25, 1866, and probated on May 29, 1868 (Thomas Cook Will, 1868.312, City and County of Philadelphia and Administrations, City Archives repository, Philadelphia).

George Hepplewhite, The Cabinet-Maker & Upholsterer’s Guide, introduction by Joseph Aronson (3rd ed., 1794; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1969), pp. vii–viii.

56 and 58 Walnut Street was owned and formerly occupied by merchant and Pennsylvania state treasurer Peter Baynton (1754–1821) and inherited by his wife, Elizabeth Bullock Baynton. The Philadelphia Contributionship Survey 301660 for George and Elizabeth Bullock dating to 1773 indicates that there were two houses, each three stories with two rooms per floor and each 17' wide and 34' deep. This explains why some Cook & Parkin labels say 58 Walnut Street and suggest that the firm occupied both houses but used only one address, #56. Fromberger’s Court does not appear on period or modern maps, but O’Brien’s Wholesale Business Directory of 1849 indicates that it ran west from 34 North Second Street, probably north of Church Street; Fromberger’s Court may have been what is now Filbert Street (Philadelphia: O’Brien, 1849). Robert DeSilver’s Philadelphia Directory and Stranger’s Guide (Philadelphia: Robert DeSilver, 1833). It is possible, albeit unlikely, that these are residences. 7 Pear Street (Thomas today), which ran one block between Dock Street and South Third south of Walnut, may have been the back or residential entrance to 56 Walnut Street. For the move to Egyptian Hall, see DeSilver’s Philadelphia Directory.

Deborah Ducoff-Barone, “The Early Industrialization of the Philadelphia Furniture Trade, 1800–1840” (Ph.D diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1985), pp. 15–21. J. Drayton, Plan of the City of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: H. C. Carey and I. Lees, 1824).

Cook is listed at 16 Pine Street until 1857 and 104 Pine Street until 1860. Cook’s house at 16 Pine Street was surveyed by the Philadelphia Contributionship in 1836, 1840, and 1848 (505157). 16 and 104 Pine may reflect a renumbering rather than a change of location. His daughter, Mary, her husband, Henry C. Stellwagen, and the couple’s children, Thomas and Catherine, were living with Cook in 1850. The final directory listing for Cook was in 1862 at 1627 Chestnut Street, the Stellwagens’ home (McElroy’s Philadelphia City Directory [Philadelphia: McElroy, 1862]). The Thomas R. Cook who was described in the 1839 directory as a carver and gilder at 35 Plum Street emigrated from Edinburg, Scotland, and was not a relative. His son, Thomas A. Cook, also became a carver and gilder in Philadelphia (Ducoff-Barone, “Early Industrialization of the Philadelphia Furniture Trade,” p. 80).

Deborah Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers, 1816–1830,” Antiques 145, no. 5 (May 1994): 742–55. Thomas Whitecar’s shop had seven workbenches (1822), Benjamin Thompson’s, eight (1819), Jacob Super’s, nine (1820), Thomas Nossitter’s, nine (October 12, 1825), T. B. Emery’s, eleven (1825), and David Fleetwood’s, twenty-two (1833–1837) (Ducoff-Barone, “Early Industrialization of the Philadelphia Furniture Trade,” p. 110). Isaac Pippitt advertised for four journeymen (April 26, 1826); Robert West employed five journeymen, three boys, and a woman (1830); Thomas Whitecar had “four persons with little work to keep them busy and twenty persons within the last 12–18 months” (1820), and John Jamison employed eight men and four boys (1830) (Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers,” pp. 744–55).

Ducoff-Barone, “Early Industrialization of the Philadelphia Furniture Trade,” pp. 65–79. The broadside is dated March 9, 1826, and is bound into a copy of the price guide owned by cabinetmaker Stephen Noblitz (act. 1826–1840) (Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware). Cook & Parkin’s copy of The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet Ware (1828), one of the very few to survive, is in the collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Of the 187 chair- or cabinetmakers who were signatories to the Constitution of the Pennsylvania Society of Journeymen Cabinetmakers in either 1825 or 1829, only ten remained listed in the Philadelphia city directories for fifteen years or more. None of the most prominent furniture makers—including Joseph B. Barry, Joseph Beal, Michel Bouvier, Henry Connelly, Thomas Cook, Otto James, John Jamison, Isaac Jones, Anthony G. Quervelle, Richard Parkin, I. Pippitt, Charles H. White, John F. White, or Thomas Whitecar—signed the agreement (Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers,” pp. 744–55).

Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers,” pp. 744–55.

Ducoff-Barone, “Early Industrialization of the Philadelphia Furniture Trade,” pp. 116, 123. A building behind the house was used for domestic purposes.

Ibid., p. 128.

Aurora General Advertiser, January 12, 1812. George Bullock Cabinetmaker, edited by Clive Wainwright (London: H. Blairman and Son, Ltd., 1988), p. 23.

O’Brien’s Wholesale Business Directory listed Parkin at 134 South Second Street in 1849. The Richard Parkin listed at other addresses in 1853 and 1854 must have been his son. The elder Parkin lived with Richard Jr. at 540 North Twelfth Street in those years.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Daniel Parker Papers, Zaccheus Collins receipted bills 1819, HSP Coll. 1587. The author thanks Anne Verplank for bringing the receipt to his attention.

Nancy Goyne Evans, Windsor-Chair Making in America: From Craft Shop to Consumer (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2006), pp. 160, 210, 213, 214, 234, 247, 248, 327, 328, 454.

Only one other paper label is known. On that example, the address was corrected in ink to read “56” rather than “58” Walnut Street. This label appears on a photocopy along with an image of a Restoration pier table, presumably the object on which the label is found. Regrettably, the location of the pier table is not known (acc. file 1989.26, Baltimore Museum of Art). The author thanks David Park Curry and Dawn Krause for making the sideboard and the museum’s file available for study. Wendy A. Cooper, Classical Taste in America, 1800–1840 (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1993), p. 56.

This distinctive capital was also used at Ephesus, near Pergamum. James Stuart and Nicholas Revett discuss and illustrate the Tower of the Winds at Athens, which supposedly featured Pergamene capitals, in volume 1 of Antiquities of Athens (1762), but there is no useful depiction of the structure’s capitals. See Thomas Gordon Smith, Vitruvius on Architecture (New York: Monacelli Press. 2003), fig. 218, for an image of the Pergamene capital Lord Elgin brought to England. The British Museum acquired the Elgin marbles in 1816 and may have put them on view shortly thereafter. In 1817 John Keats published his poem “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles for the First Time.”

Allison Boor and Jonathan Boor, Philadelphia Empire Furniture (West Chester, Pa.: Boor Management, 2006), p. 53. William Atlee to Isaac Wayne, August 7, 1823, Wayne Family Papers, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. A copy of Cook & Parkin’s receipt for $55.00 is in the files at Waynesborough, Anthony Wayne Foundation. The sideboard’s location is currently unknown. Isaac Wayne served in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and Senate between 1799 and 1810 and the U.S. Senate from 1823 to 1825. The author thanks Donna Lynne Anderson of the Anthony Wayne Foundation for her assistance.

Decorative Arts Photographic Collection (hereafter DAPC), file no. 2000.0240, Winterthur Library, Winterthur, Delaware. A jelly jar label on the bottom of the pier table is inscribed “Gertrude Dun / her Grand Mother / James left her by her mother / 1898.” The dust board is inscribed “Dun West Jefferson.” The author thanks Jeanne Solensky at the Winterthur Library, John R. Tompkins, Tom Halverson of New Orleans Auction Gallery, and the table’s current owners for their assistance. Rudolph Ackermann, Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions, and Politics, ser. 2, vol. 14 (December 1822): 367.

Boor and Boor, Philadelphia Empire Furniture, pp. 233–35. Oral tradition maintains that the table illustrated in figure 18 descended from Henry Eichholtz Leman (1812–1887) to his son Henry Leaman Jr. to his daughter Delia Leaman, who donated it to the James Buchanan Foundation in 1942. For more on this table, see Nicholas Vincent, “Philadelphia Pier Tables and Their Role in Cultures of Sociability and Competition,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collector’s Club, Ltd. for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), p. 118, fig. 27. The original owner of the table may have been artist Jacob Eichholtz, Henry Eichholtz Leman’s uncle. Jacob mentioned a pier table in a letter dated 1832, but it is not clear that he was referring to the example illustrated here. The author thanks Jennifer L. Walton, assistant director of President James Buchanan’s Wheatland, for information on this table.

Franklin Journal and American Mechanics’ Magazine 3 (1827): 54, 55. According to Richard D. Hoblyn, Dictionary of Terms Used in Medicine and the Collateral Science (Philadelphia, Pa.: Henry C. Lee, 1865), artimomantico was patented in France in 1814 and is an alloy composed of tin, sulfur, bismuth, and copper. It was reputed to have the visual appearance of gold and not tarnish. J. C. Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture and Furniture: Selections (1833) (1839; reprint, East Andsley, Yorkshire: S. R. Publishers, 1970), pp. 654, 1065. In the March 5, 1840, issue of the Evening Post, New York cabinetmaker Alexander Roux advertised “iron frame Sofas and Chairs, being the first of the kind ever introduced into this country, which for comfort and durability, place them superior to any thing now in use.”

Freeman’s Journal and Philadelphia Mercantile Advertiser, August 15, 1827. Daniel Powles’s invention was first publicized in the Journal of the American Institute of the City of New York 1 (October 1836): 2, 374. A Baltimore, Maryland, inventor, Powles patented a bed and sacking bottom “which can be put up and taken down by any person owing to the peculiar construction of the joints and is proof against insects.” The patent was issued on October 31, 1821, and expired on the same day in 1835. Powles’s invention won the John Scott Award in 1827. With the award, the city council of Philadelphia acknowledged his contribution to the “comfort, welfare and happiness of mankind” and awarded him $20.00 and a copper medallion inscribed “To the Most Deserving” (www.garfield.Library.upenn.edu/johnscottaward/js1822-1830.html).

Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers,” pp. 744–46. The stencil is the same as the one on the pier table illustrated in figure 12. Plate 3 of the 1828 Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices shows feet for Loo Tables that are of the same profile as those on the center table, indicating that this foot design was already in use when that book was published. One of the tables bearing a stencil like the example illustrated in figure 19 is illustrated in Boor and Boor, Philadelphia Empire Furniture, p. 129, and is in the Sewell Biggs Museum, Dover, Delaware. An identical, unmarked table has a Savannah provenance and is in a private collection in Pine Mountain, Georgia. A fourth, unmarked table was offered for sale at New Orleans Auctions, New Orleans, Louisiana, September 20–October 2, 2011. The author thanks Brandy Culp and Karen Emmons at Historic Charleston Foundation, Lynn Hanlin of Carriage Properties, Charleston, Albert Simons III, and G. Dana Sinkler for assistance in finding the table illustrated in The Octagon Library of Early American Architecture, vol. 1, Charleston, South Carolina, edited by Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham Jr. (New York: Press of the American Institute of Architects, 1927), n.p. The table was in the same location in the Eveleigh house in 1954 (Charleston Evening Post, March 19, 1954). The table is partially visible in a photograph published two years later (Samuel Chamberlain and Narcissa Chamberlain, Southern Interiors of Charleston [New York: Hastings House, 1956], p. 60). Thomas Deas was located on East Bay in the 1820s. James Dick, operating after 1813 at 341 King Street, was a dry goods merchant. He closed this business in 1820 and subsequently went into partnership with Sandiford Holmes. The author thanks Bridget J. O’Brien of Historic Charleston Foundation for investigating the activities of these merchants.

For a Boston example, see Barry Tracy, Marilyn Johnson, and Marvin D. Schwartz, 19th Century American Furniture and Other Decorative Arts (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970), fig. 66. DeSilver’s Philadelphia Directory. For the labeled sofa, see Tracy, Johnson, and Schwartz, 19th Century American Furniture and Other Decorative Arts, fig. 65. John Hancock Will, 1835: 172, City and County of Philadelphia Wills and Administrations. For more on the Hancocks, see David H. Conradsen, “The Stock-in-Trade of John Hancock & Company,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1993), p. 54; and David H. Conradsen, “Ease and Economy: The Hancock Brothers and the Development of Spring-Seat Upholstery in America” (M.A. thesis, University of Delaware, 1998). The author thanks David Conradsen for bringing this information to his attention. Cook & Parkin’s shop was at 56 Walnut, and John Hancock & Company was across Third Street at Walnut and Third Streets.

Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers,” pp. 744–46. Outbound Coastal Manifests, Port of Philadelphia, October 16, 1823, December 1824, July 5, 1828, December 9, 1830, Record Group 36, NARA. Page Talbott, Classical Savannah (Savannah, Ga.: Telfair Museum of Art, 1995), p. 16. Maria Campbell to George J. Collock, March 5, 1830, in “The Kollock Papers, Part III,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 31, no. 1 (January 1947): 41–42. Cook and Parkin consigned furniture to several Savannah agents, including R. and J. Habersham, J. J. Middleton, and cabinetmaker Isaac W. Morrell (Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers,” pp. 744–76; and Outbound Coastal Manifests, Port of Philadelphia, October 16, 1823, December 1824, July 5, 1828, December 9, 1830, Record Group 36, NARA). Morrell often traveled north to buy furniture on speculation and was the Savannah agent for many New York cabinetmakers, including Joseph Brauwers, John Hewitt, and Duncan Phyfe. Talbott, Classical Savannah, p. 14.

Talbott, Classical Savannah, pp. 145, 146n72.

Ibid., pp. 146, 147n73.

For the table, see Mary Telfair to Margaret Telfair, October 25, 1836, Manuscript Collection 793, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah. Feay Shellman Coleman, Nostrums for Fashionable Entertainments: Dining in Georgia, 1800–1850 (Savannah, Ga.: Telfair Academy, 1992), pp. 65, 66; Boor and Boor, Philadelphia Empire Furniture, p. 163. Talbott notes that the Telfairs and Kollocks were friends and that members of both families were in Philadelphia in 1831 and 1832, when Cook & Parkin were executing orders for maple furniture for Savannah clients (Talbott, Classical Savannah, p. 168nn74, 77). Thomas Graham was a journeyman in Cook’s shop when Margaret Telfair ordered the table. Graham was born in Ireland in 1817, began serving his apprenticeship with Cook & Parkin in 1828, and left the former’s employ as a journeyman in 1837 (Philadelphia & Popular Philadelphians, edited by Col. Clayton McMichael [Philadelphia: North American, 1891], p. 286).

Cook & Parkin to Josiah Johnston, January 16, 1826, Johnston Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Johnston served in the Seventeenth Congress from 1821 to 1822 and in the U.S. Senate from 1823 until his untimely death in 1833 from an explosion on the steamboat Lioness on the Red River in Louisiana (Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=j000194).

George was the son of Colonel Nathaniel Burwell and grandson of Carter Burwell, owner of Carter’s Grove Plantation. Correspondence of George Harrison Burwell, 1820–1871, Mss 1 B9585 a 40-384, Burwell Family Papers, 1770–1965, Sec. 6, Department of Manuscripts and Archives, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond. The invoice notes that payment was received from the tailors Robb & Winebrenner, who were located at the northeast corner of South Third and Pear Streets on the same block as Cook & Parkin. The author thanks Eileen Parris and Katherine Wilkins of the Virginia Historical Society for retrieving this manuscript.

Ibid. Neal Auction, Winter Estates Auction, New Orleans, Louisiana, February 24, 2008, lot 835. www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/deschart/z0000594.html. Burwell bought, at the same time, forty-four chairs from Joseph Burden (act. 1793–1839), a successful Philadelphia Windsor and fancy chairmaker and exporter, whose shop at 95–97 South Third Street was around the corner from Cook & Parkin’s (DeSilver’s Philadelphia Directory). Photographs of Carter Hall in 1932 by Samuel H. Gettscho show a Philadelphia sideboard in the dining room. That object may be the sideboard listed on Cook & Parkin’s invoice to George Burwell for $70.00 (Gettscho-Schleisner Collection, Library of Congress).

Boor and Boor, Philadelphia Empire Furniture, pp. 378, 379. DAPC, file no. 80.483. A related sofa by Barry is inscribed, “G. W. Pickering, Maker, September 5, 1833, Barry” (ibid., p. 377). The sofa’s history can be traced to the Rev. Joseph Layton Mauzé and his wife, Eleanor (Harmon), but it is not clear from which of their families it descended. Their respective grandfathers, William Burbridge Yancy (1803–1858), a landholder along the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, and Michael G. Harmon (1823–1887), a stagecoach and hotel owner and planter of Staunton, Virginia, are likely owners. The author thanks Chet Breitwieser for information on the provenance, and Charles MacKay and Cameron McCluskey for making the sofa available for photography.

Cook and Parkin’s southern market also consisted of furniture made by other cabinetmakers. They sold a sofa table made by Baltimore cabinetmaker David Bodensick (act. 1833–1860) to Dr. William Newton Mercer in Natchez, Mississippi, circa 1833 (Gregory R. Weidman, Classical Maryland, 1815–1845 [Baltimore, Md.: Maryland Historical Society, 1993], p. 132).

The “wardrobe” and “dwarf wardrobe” illustrated in plates 133 and 134 in Smith’s Household Furniture influenced Cook & Parkin’s work. Those designs presaged the “Ladies Dwarf Wardrobe” illustrated in plate 31 in Smith’s Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide and influenced the wardrobe shown on page 83 in King’s Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified. Jason T. Busch, “Furniture Patronage in Antebellum Natchez,” Antiques 157, no. 5 (May 2000): 804–13. The wardrobe was all but destroyed by fire on September 17, 2002. The author thanks Mimi Miller of the Natchez Historical Foundation for pictures of this object taken both before and after the fire.

The label, now separated from the chair, has a corrected address changed from 123 (South Second Street) to 134 and is inscribed “Whitfield,” a family name in the provenance of this set. The set descended in the Reigart family of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The original owner was probably Emanuel Carpenter Reigart (1796–1869) and his wife, Barbara (Swarr) (1800–1838). Their granddaughter Mary Catherine Reigart married William V. Whitfield in 1874. This distinctive, anthemion-carved stay rail also appears on a chair design in plate 17 in King’s Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified, but the rail is set at the traditional height.