Prospect Of the new Lutheran Church in Philada which was on the 26th of Dec. 1794 in the evening from the hour of eight till twelve Consumed by Fire, engraved by Frederick Reiche, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1795. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

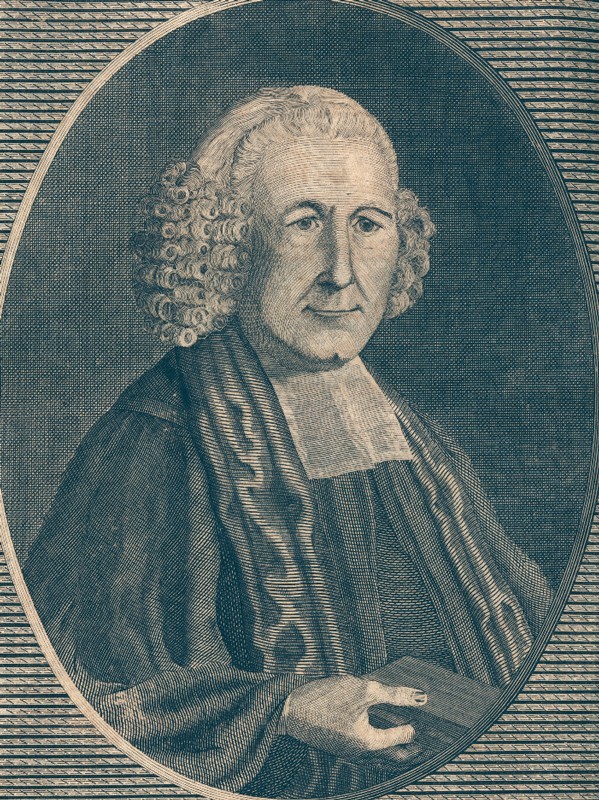

Detail of a portrait of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, from Justus Heinrich Christian Helmuth, Denkmal der Liebe und Achtung . . . dem Herrn D. Heinrich Melchior Mühlenberg (Philadelphia: Melchior Steiner, 1788). (Courtesy, Lutheran Archives Center, Philadelphia.)

Old Lutheran Church, in Fifth Street, Philadelphia, drawn and engraved by William Russell Birch and Thomas Birch, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1800, and published in Birch’s Views of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: W. Birch, 1800). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

New Lutheran Church, in Fourth Street Philadelphia, drawn and engraved by William Russell Birch and Thomas Birch, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1799, and published in Birch’s Views of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: W. Birch, 1800). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.) When Philadelphia was the federal capital during the 1790s, delegations of Indians visited the city to settle affairs with the government. This engraving is said to depict Frederick Muhlenberg conducting a tour for one of these groups.

Peter Frick, organ case, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1771–1774. (Courtesy, Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, Lancaster, Pa.; photo, ca. 1880.)

Detail of the carved plaque at the base of the central tower on the organ illustrated in fig. 5. (Courtesy, Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, Lancaster, Pa.; photo, Lloyd Bull.)

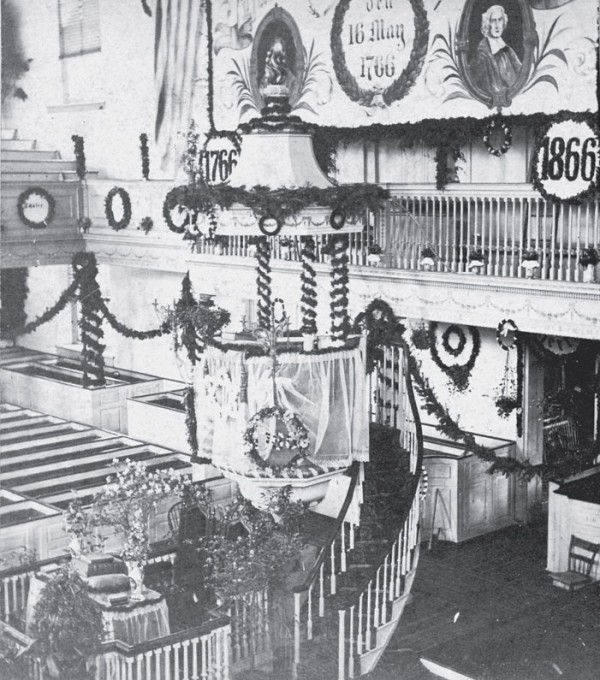

Photograph of Zion Lutheran Church interior, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1866. (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Christian Selzer, chest, Jonestown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1796. White pine with tulip poplar. H. 23 1/2", W. 52 1/4", D. 22 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Dish attributed to George Hubener, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1789. Lead-glazed red earthenware. Diam. 13". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

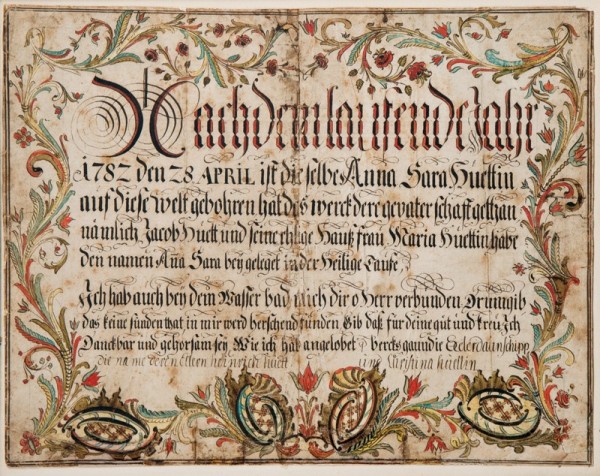

Birth and baptismal certificate for Anna Sara Huett, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1782. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 16" x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Steve and Susan Babinsky; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest-over-drawers, Manheim area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Cherry with walnut and yellow pine. H. 19", W. 29 1/4", D. 15 3/*4". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.) The brasses are replaced.

Ten-plate stove, Elizabeth Furnace, Elizabeth Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1769. Iron. H. 63 1/4", W. 15", D. 44 1/4". (Courtesy, Hershey Museum; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art, David Allison.) The front plate depicts Aesop’s fable of the dog and its reflection.

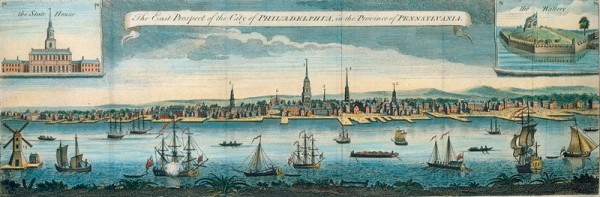

George Heap, The East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania (London Magazine, 1761). (Courtesy, American Philosophical Society.)

Map of southeastern Pennsylvania. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson and Tom Willcockson.)

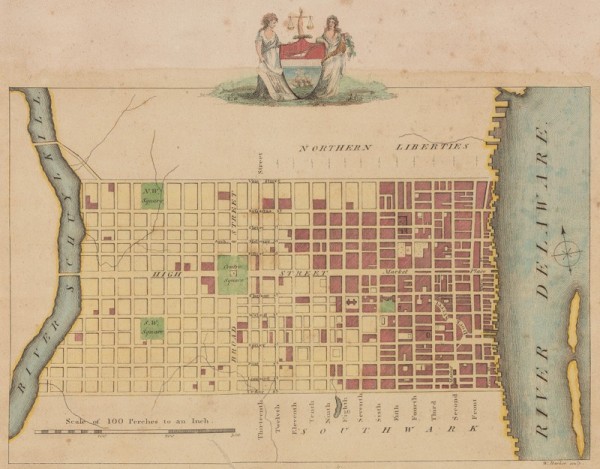

Plan of the City of Philadelphia, drawn and engraved by William Russell Birch and Thomas Birch, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1800, and published in Birch’s Views of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: W. Birch, 1800) (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

Looking glass labeled by John Elliott Sr., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1762–1767. Walnut with white cedar. H. 13 1/4", W. 7", D. 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the label on the reverse of the looking glass illustrated in fig. 16.

Map of European origins of German-speaking immigrants to Pennsylvania (in blue). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; artwork, Tom Willcockson, Mapcraft.com.)

Armchair attributed to the shop of Solomon Fussell, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1740. Maple. H. 45", W. 25 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, James Schneck.)

Christopher Witt, Johannes Kelpius, Germantown, Pennsylvania, ca. 1705. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 9 1/8" x 6 3/8". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

Side chair, probably Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Walnut. H. 43 3/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, James Schneck.)

Side chair, probably West Marlborough Township area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1730–1750. Walnut. H. 40 1/2", W. 17 3/4", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Primitive Hall Foundation; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Chest, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Walnut veneer and maple and mahogany inlay with yellow pine. H. 8 1/4", W. 12 1/4", D. 8". (Courtesy, Krauth Memorial Library, Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two slots were inserted at a later date to convert the chest into an alms box or ballot box. The veneer was identified as American black walnut by microanalysis.

Detail of the lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 23. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Lewis Miller, drawing of the altar in Christ Lutheran Church, York, Pennsylvania, ca. 1811. (Courtesy, York County Heritage Trust; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

End view of the chest illustrated in fig. 23. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

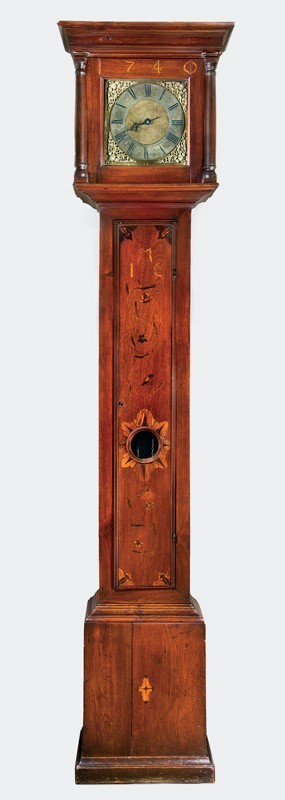

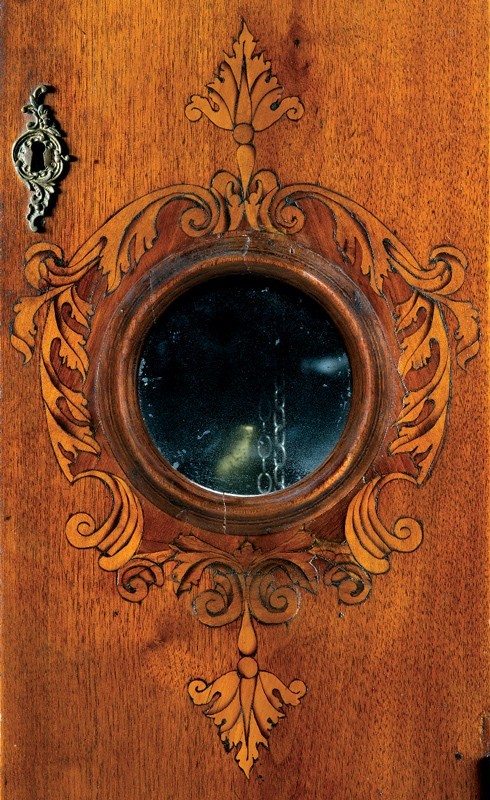

Tall-case clock, Philadelphia area, Pennsylvania, 1740. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and red oak. H. 90", W. 20 1/2", D. 13". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The movement is probably British and dates 1680–1700.

Schrank, Philadelphia area, Pennsylvania, 1741. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with yellow pine, tulip poplar, walnut, and oak. H. 76", W. 75 1/4", D. 27 1/2". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

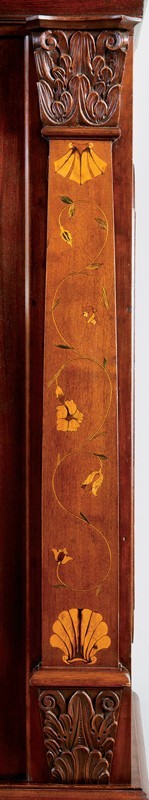

Detail of an inlaid pilaster on the schrank illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

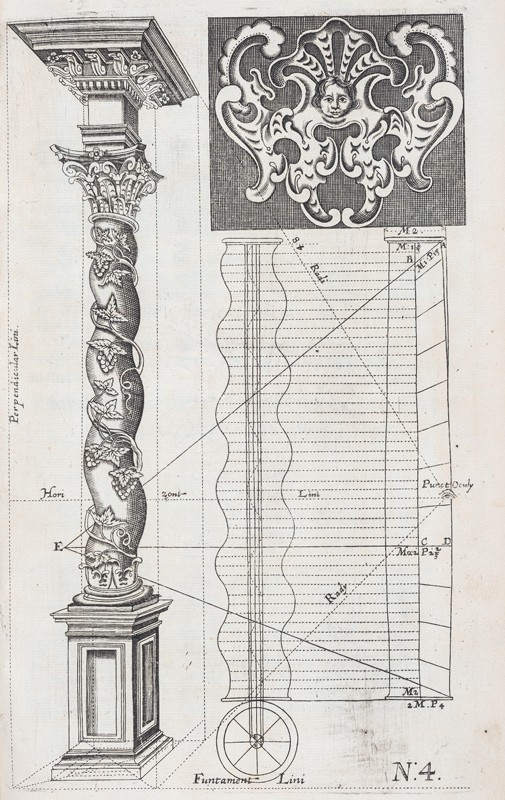

Detail of a column with carved floral decoration, in Georg Caspar Erasmus, Seulen-Buch Oder Gründlicher Bericht von der Fünff Ordnungen der Architectur-Kunst welche solche von Marco Vitruvio, Jacobo Barrozzio, Hans Blumen C. und Andern . . . (Nuremberg, 1688). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

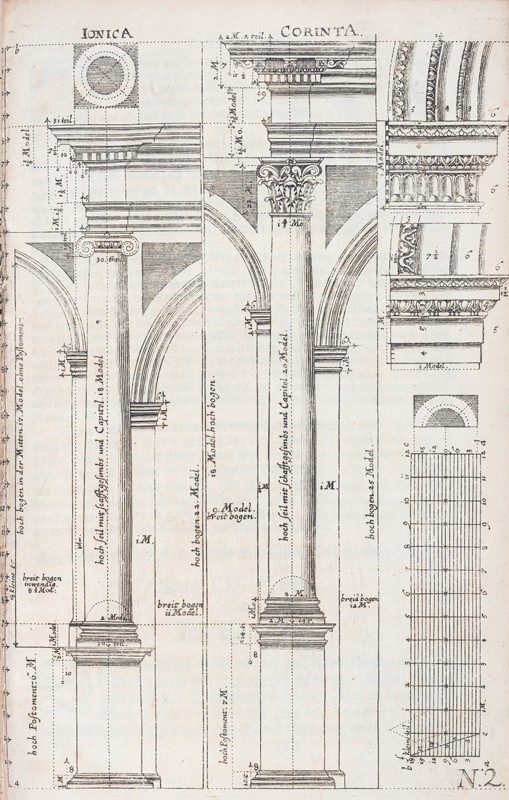

Detail of the Ionic and Corinthian orders, in Georg Caspar Erasmus, Seulen-Buch Oder Gründlicher Bericht von der Fünff Ordnungen der Architectur-Kunst welche solche von Marco Vitruvio, Jacobo Barrozzio, Hans Blumen C. und Andern . . . (Nuremberg, 1688). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

Detail of the inlaid shell and carved capital on the schrank illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

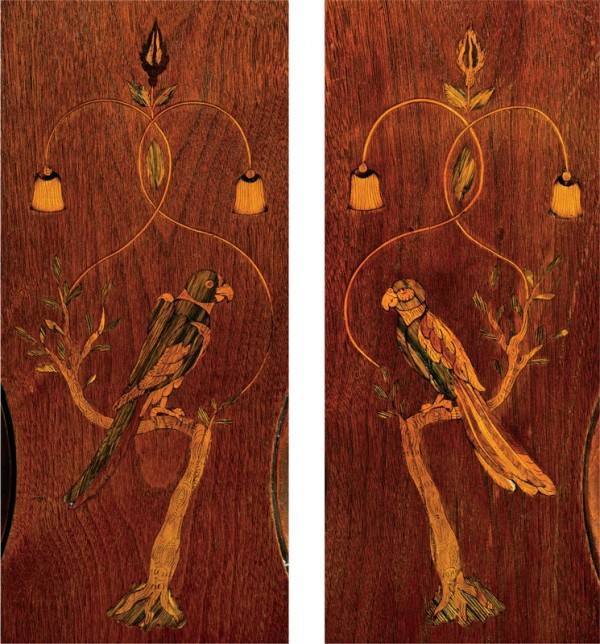

Details of the inlaid birds on the schrank illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

The Parrot of Carolina, in Mark Catesby, Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (London, 1729–1747). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

Drawing of a parrot, bird, and flowers, attributed to Henrich Otto, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 7 7/8" x 6 1/2". (Collection of Dr. and Mrs. Donald M. Herr.)

Desk, Philadelphia area, Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with walnut and tulip poplar. H. 42 3/4", W. 42", D. 21 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Lid of the desk illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the figure inlaid on the desk illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing two flowers inlaid on the desk illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the birds inlaid on the pendulum doors of a clock made for George Yunt, Ephrata, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1755 (left), and a clock, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1755 (right). (Courtesy, Earle H. and Yvonne Henderson; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo [left]; courtesy, Pook & Pook [right].)

Valuables cabinet or spice box, Philadelphia area, Pennsylvania, ca. 1740. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with walnut and pine. H. 16", W. 14 1/4", D. 10 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the cabinet illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the cabinet illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Kirchheim unter Teck, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 1720–1730. Walnut, maple, and plum with poplar and yew. H. 62 1/2", W. 44 1/4", D. 30". (Courtesy, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart, 1977/106.)

A Parroqueet from Angola, in Eleazar Albin, A Natural History of Birds, vol. 3 (London, 1740). (Courtesy, Teylers Museum.)

Pair of silkwork pictures, by Sarah Wistar, Philadelphia, 1752. Silk on silk moiré. 9 1/2" x 7" (unframed). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tall-case clock with movement by Augustin Neisser, Philadelphia area, Pennsylvania, ca. 1745. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and pine. H. 93 1/2", W. 22 1/2", D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet, waist door hinges, and bottom section of waist molding are replaced.

Tall-case clock with movement by Joseph Wills, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; case, Philadelphia area, Pennsylvania, ca. 1745. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and pine. H. 86", W. 22 1/4", D. 12". (Courtesy, York County Heritage Trust; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The waist door hinges are replaced.

Details of the inlaid birds on the clocks illustrated in fig. 47 (left) and fig. 48 (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cartouche on the clock illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

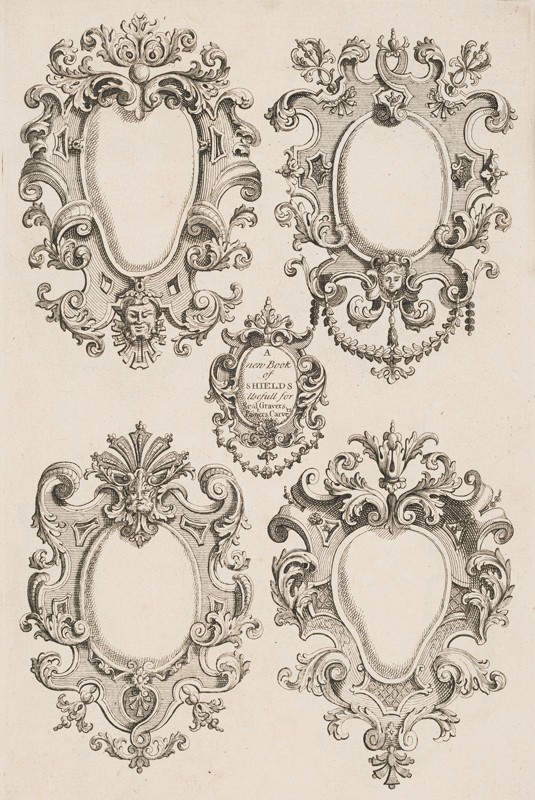

Designs for cartouches in A Compleat Book of Ornaments (London, ca. 1740). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

Johann Georg Wahl, tabernakelschrank Osthofen, Germany, 1743. Oak with maple and walnut veneer and mixed-wood, ivory, and ebony inlay. H. 81 1/2", W. 47", D. 26". (Courtesy, Newark Museum; photo, Robert Crabb, 1929)

Library bookcase attributed to Martin Pfeninger, Charleston, South Carolina, 1770–1775. Mahogany, mahogany and burl walnut veneer, mixed-wood inlays and ivory with cypress. H. 128 3/4", W. 99", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Charleston Museum; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Gavin Ashworth.)

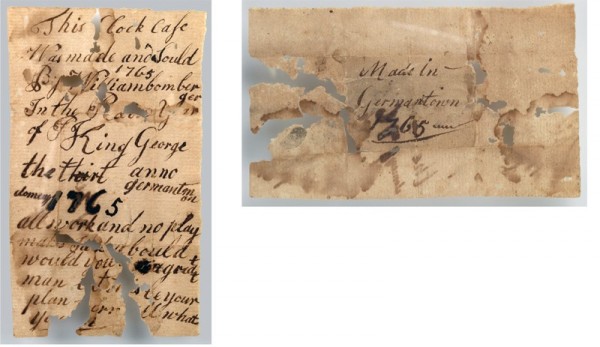

Tall-case clock with movement by George Miller and case by William Bomberger, Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1765. Walnut with tulip poplar, and yellow pine. H. 98", W. 20 3/4", D. 11 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Details of the label inside the clock illustrated in fig. 54. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Jonathan Shoemaker, chest-on-chest, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 97", W. 44", D. 23". (Courtesy, © Christie’s Images Ltd.)

Detail of the carving on the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 56.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 39 3/4", W. 29", D. 22". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, bequest of William W. Doughten, 1956; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The splat has been altered by the removal of a carved tassel.

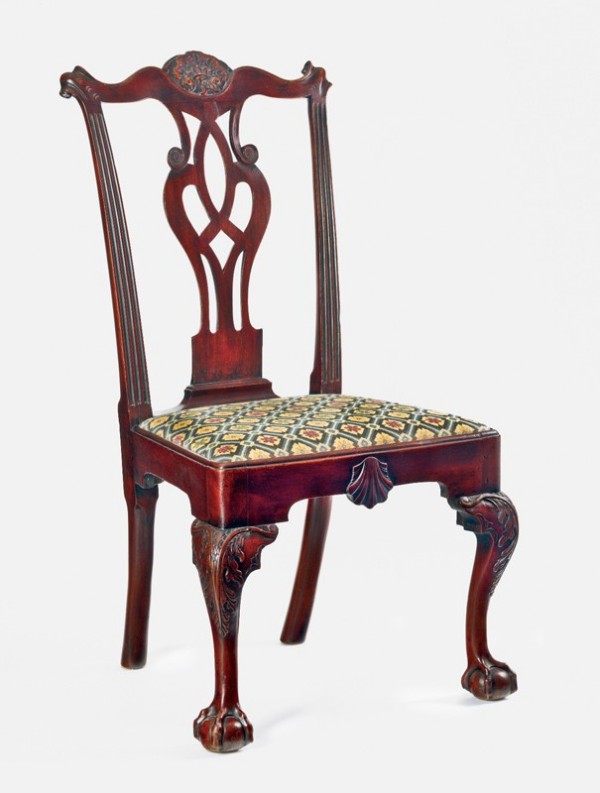

Pair of side chairs attributed to Leonard Kessler, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1763. Mahogany. H. 40 1/2", W. 21 1/2", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cartouche on the crest of one of the chairs illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cartouche on the chair illustrated in fig. 62. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 41", W. 21 1/2", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Leslie Miller and Richard Worley; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The carving is attributed to Nicholas Bernard.

Side chair attributed to Leonard Kessler, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 40 1/2", W. 21 1/2", D. 17". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

Detail of the cartouche on the chair illustrated in fig. 63.

Side chair attributed to Leonard Kessler, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 41", W. 21", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, H. L. Chalfant.)

House of Henry and Mary Muhlenberg, Trappe, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, built ca. 1750–1755. (Photo, Glenn Holcombe.)

Tea table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1766. Mahogany. Dimensions unrecorded. (Photo reproduced from Henrietta Meier Oakley and John Christopher Schwab, Muhlenberg Album [New Haven, Conn.: the authors, 1910].)

House of Frederick Muhlenberg, Trappe, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, built ca. 1763. (Courtesy, The Speaker’s House; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The roofline of the store is visible on the right side; the mansard roof is a later addition.

Augustus Lutheran Church, Trappe, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, built 1743. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stucco is a later addition.

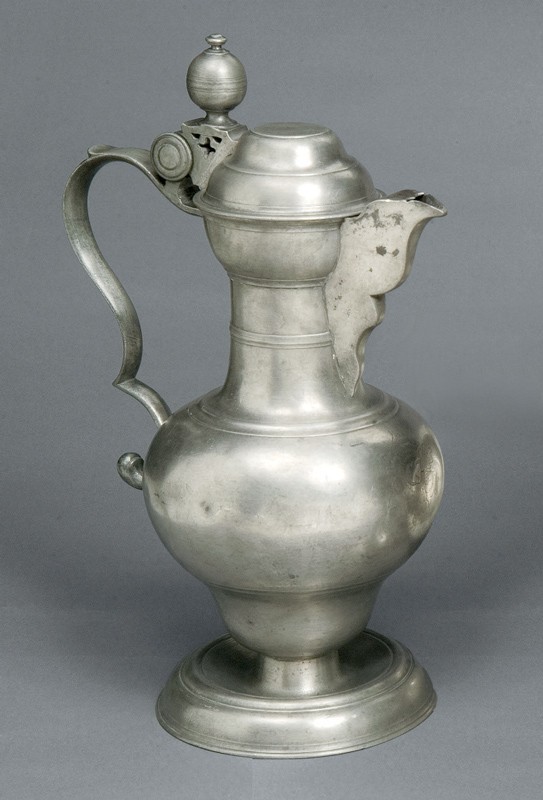

Communion flagon attributed to Johann Philip Alberti, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Pewter. H. 13". (Courtesy, Augustus Lutheran Church; photo, Glenn Holcombe.)

Communion flagon and chalice attributed to William Will, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1795. Pewter. H. 13 3/4" (flagon), 7 7/8" (chalice). (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, The Dobson Foundation; Friends of American Arts Acquisition Fund; Mr. and Mrs. Frank J. Coyle, LL.B. 1943, Fund, Peter B. Cooper, B.A. 1960, LL.B. 1964, M.U.S. 1965, and Field C. McIntyre American Decorative Arts Acquisition Fund; Friends of American Arts Decorative Arts Acquisition; and Lisa Koenigsberg, M.A. 1981, M.Phil. 1984, Ph.D. 1987, and David Becker, B.A. 1979 Fund [flagon]; Winterthur Museum [chalice].)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Walnut with hard pine slip seat frame. H. 40 1/2", W. 24", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Craig McDougal.)

Detail of the crest on the chair illustrated in fig. 72. (Photo, Craig McDougal.)

Joseph Hiester, attributed to Jacob Witman, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Oil on canvas. 36" x 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Elizabeth Hiester, attributed to Jacob Witman, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Oil on canvas. 36" x 30". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bergère attributed to George Bright, Boston, Massachusetts, 1797. Mahogany with white pine. H. 33 1/2", W. 24", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Tea table, probably Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Walnut. H. 28 1/8", Diam. 33 7/8".(Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

House of Daniel Hiester, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, built 1757. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Paneled wall with built-in schrank and corner fireplace in the Daniel Hiester House. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the staircase in the Daniel Hiester House. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut. H. 39 1/2", W. 21 3/4", D. 20". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cartouche on the chair illustrated in fig. 81. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. (Courtesy, Pook & Pook.)

John Meng, John Meng, Germantown, Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Oil on canvas. 43 1/4" x 32 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection.)

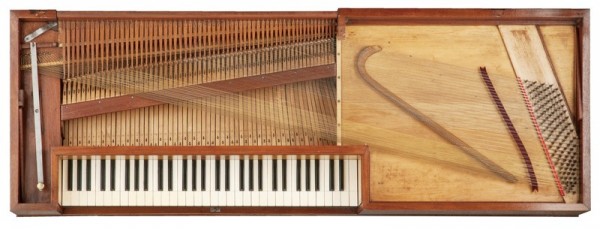

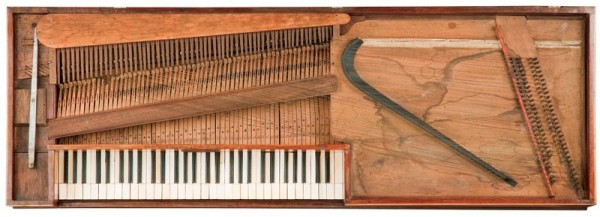

Johann Gottlob Klemm, spinet, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1739. Walnut, maple, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 33 1/2", W. 73 1/4", D. 27". (Image copyright © Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944; image source, Art Resource, NY.) The keyboard is replaced.

Mather Brown, Portrait of a Young Woman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1801. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40 1/4". (Image copyright © Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Caroline Newhouse, 1965; image source, Art Resource, NY.)

Music stool, possibly Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Mahogany, tulip poplar, hickory (screw); paint. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, James Schneck.) The black horsehair upholstery and brass nails are original.

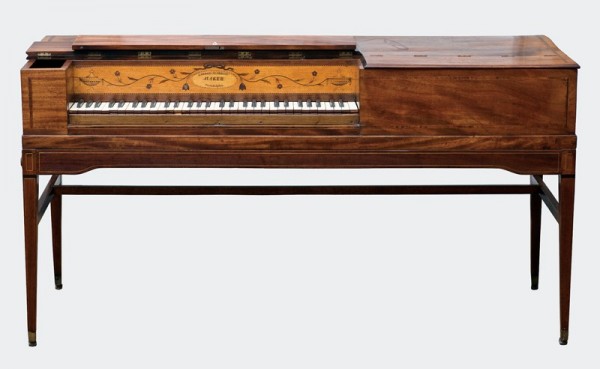

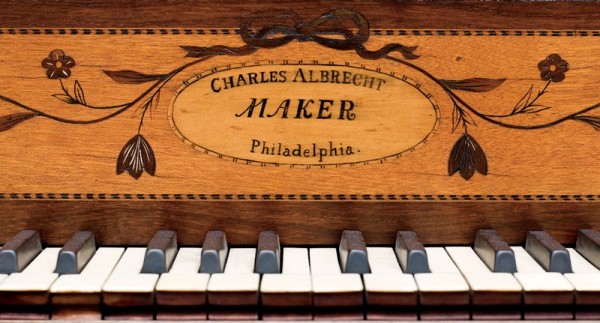

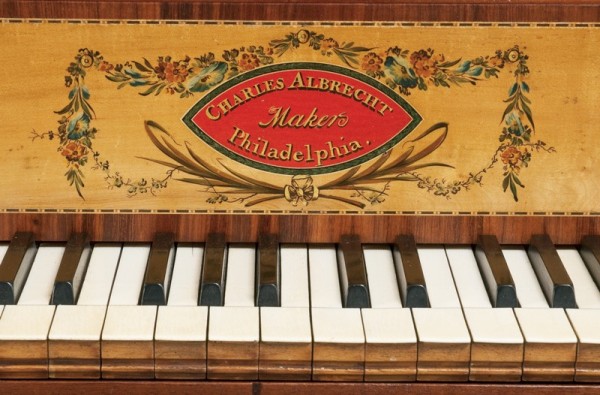

Charles Albrecht, square piano, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1789. Mahogany, mahogany and satinwood veneer, black mastic, ivory, ebony, and brass. H. 31 1/2", W. 61 3/4", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the nameboard on the piano illustrated in fig. 88. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the letter “C” on the nameboard of the piano illustrated in fig. 88. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the nameboard on a square piano by Charles Albrecht, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Mahogany, mahogany and satinwood veneer, and black mastic (infill). (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

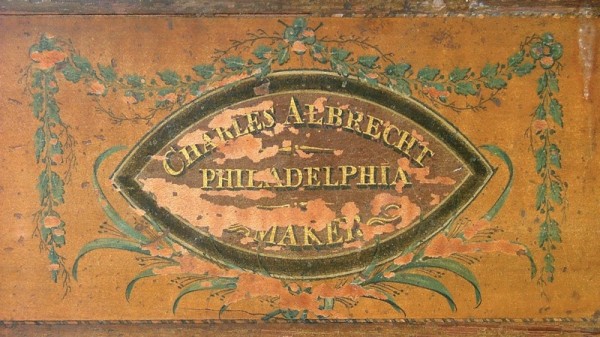

Charles Albrecht, square piano, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Mahogany, mahogany and satinwood veneer, mixed-wood inlay, ivory, ebony, and brass. H. 33", W. 63", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, E. Milby Burton Memorial Trust and The Charleston Museum, photo, Sean Money.)

Detail of the inlay on the nameboard of the piano illustrated in fig. 92.

Detail of the nameboard on the piano illustrated in fig. 92.

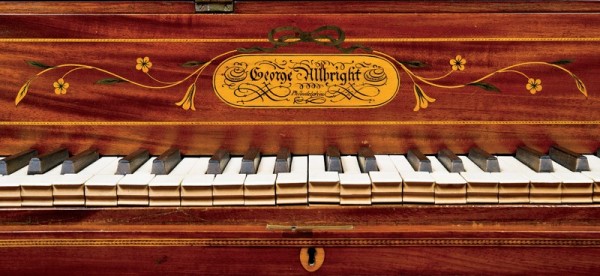

George Albrecht, square piano, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1797. Mahogany with mahogany veneer and mixed-wood inlay; ivory, ebony, brass. H. 33 7/8", W. 64 5/8", D. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The only known piano signed by George Albrecht, it may date to 1797, when Charles is absent from the Philadelphia city directory and was likely in Chester County.

Detail of the nameboard on the piano illustrated in fig. 95. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the key well inlay on the piano illustrated in fig. 95. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Charles Albrecht, square piano, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1800–1805. Mahogany, mahogany and satinwood veneer, ivory, ebony, and brass. H. 31 1/2", W. 63", D. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Mrs. Jeannette S. Hamner; photo, John Watson.) This piano has the serial number 166 and is signed on the key bed “Joshua Baker Maker.” The music shelf is replaced.

Detail of the nameboard on the piano illustrated in fig. 98.

Detail of the nameboard on a square piano by Charles Albrecht, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. (Courtesy, Blennerhassett Historical Foundation; photo, Donald H. Prior.)

Charles Albrecht, square piano, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Mahogany, mahogany and satinwood veneer; ivory, ebony, and brass. H. 33 3/4", W. 62 3/4", D. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Christie’s Images, Ltd.)

Charles Albrecht and Charles Deal, square piano, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1813. Mahogany, mahogany and satinwood veneer; ivory, ebony, and brass. H. 35 1/4", W. 69", D. 25". (Courtesy, Freeman’s; photo, Elizabeth Field.) This piano has the serial number 71 and is signed on the inside by Charles Deal.

Detail of the nameboard on the piano illustrated in fig. 102. (Photo, Daniel C. Scheid.)

Detail of the action in the piano illustrated in fig. 98. (Photo, John Watson.)

John Huber, square piano, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1805–1809. Mahogany with satinwood veneer; ivory, ebony; paper, glass. H. 33 1/8", W. 65 5/8", D. 23 1/8". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, The Friends of the Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund; photo, John Watson.)

Detail of the action in the piano illustrated in fig. 105. (Photo, John Watson.)

Detail of the label on the piano illustrated in fig. 105. (Photo, John Watson.)

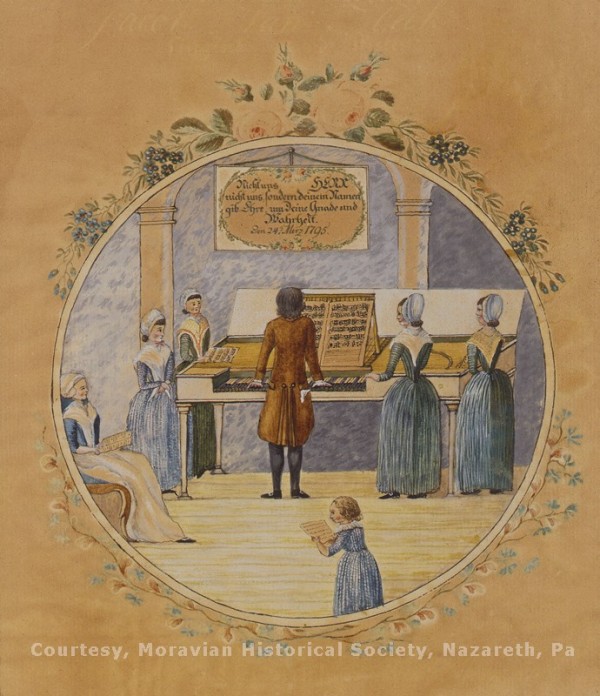

Anna Kliest, The Birthday Wish, made for Jacob van Vleck, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1795. 9" x 7 1/2". Watercolor and ink on laid paper. (Courtesy, Moravian Historical Society, Nazareth, Pa.)

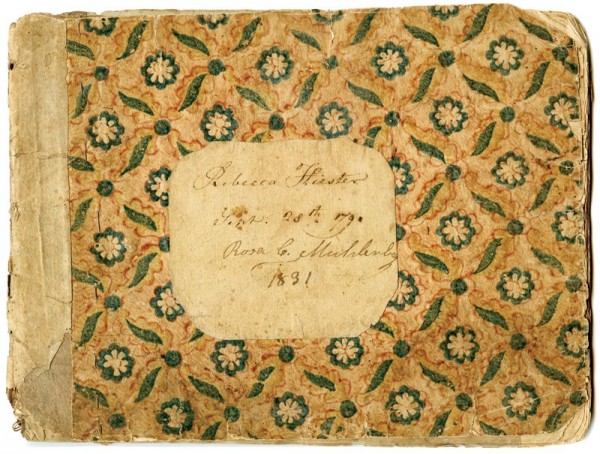

Tunebook, probably Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1791. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera; photo, James Schneck.) This book may have been shared with Rebecca Hiester’s sister, Mary Elisabeth, whose name is inscribed within.

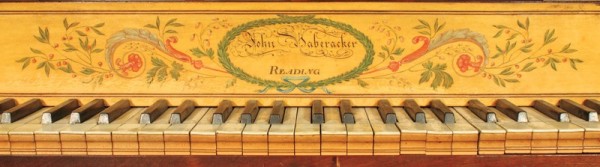

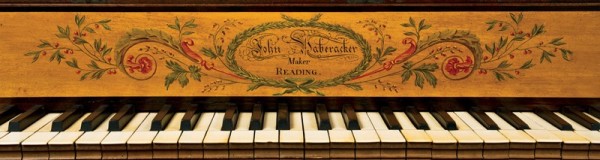

Detail of the nameboard on a square piano by John Haberacker, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Satinwood. (Courtesy, Marlowe A. Sigal.)

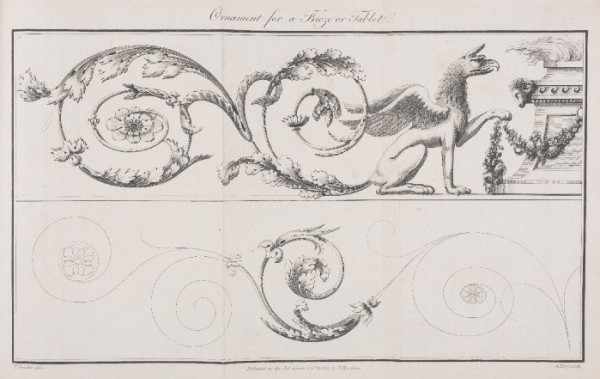

Design for a frieze or tablet illustrated in plate 36 in Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (London, 1791–1794). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

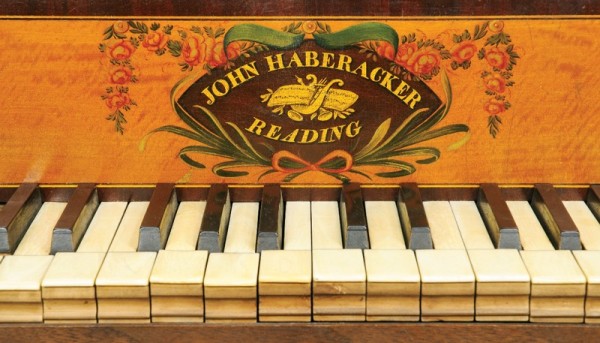

John Haberacker, square piano, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Mahogany with mahogany and satinwood veneer, ivory, and ebony. H. 33 5/8, W. 64, D. 22 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic RittenhouseTown; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the nameboard on the piano illustrated in fig. 112. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Birth and baptismal certificate of Maria Magdalena Meyer, decoration attributed to Frederick Christopher Bischoff, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 13" x 14". (Courtesy, Rare Books Department, Free Library of Philadelphia.)

Portrait of John Stump, attributed to Frederick Christopher Bischoff, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Oil on panel. 10" x 8". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Frederick Christopher Bischoff, fire bucket, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Leather. H. 13". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the nameboard on a square piano by John Haberacker, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1820. (Courtesy, John Watson.)

Joseph Wright, Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, New York, 1790. Oil on canvas with applied wood strip. 47" x 37" (including frame). (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / Art Resource, NY.) A 1 3/8" strip of wood was added to the canvas at the left edge and painted by Wright.

Brettstuhl (board chair), southeastern Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Pine and oak. H. 32", W. 18", D. 18". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Chair attributed to Johann Friedrich Bourquin (1762–1830), Bethlehem, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1803–1806. Maple; paint. H. 39 1/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 18". (Courtesy, Moravian Archives, Bethlehem, Pa.; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Teapot, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1779. Lead-glazed red earthenware. H. 5 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Christian Wiltberger (1766–1851), sugar bowl. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Silver. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Chest-over-drawers, southeastern Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. Pine; paint; brass. H. 29 3/8", W. 51", D. 23". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the eagle on the chest illustrated in fig. 123. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

FIRE! Jacob Hiltzheimer heard the alarm while visiting a neighbor on the evening of December 26, 1794. About eight o’clock, the wife of Quaker merchant Henry Drinker was sitting in her back parlor when she heard “the noise of a Fire Engine, and the ringing of Bells.” Both Hiltzheimer and Drinker went to investigate and learned the fire was in the back of Zion Lutheran Church at Fourth and Cherry Streets in Philadelphia, where a steeple was under construction. By nine o’clock, the church was thought safe. Soon, however, the bells began ringing again. The fire had spread to the roof (fig. 1). Elizabeth Drinker climbed to the third floor of her house and watched while a “mighty blaze” consumed the church, a “great and superb building . . . said to be one of the most splendid in the Union.” When the sun came up the next day, she found pieces of burned shingles in her yard. The fire had caused the church roof to collapse, gutting the interior and destroying its magnificent new organ, built by David Tannenberg and completed just four years earlier. Only the brick walls remained.[1]

Zion was one of two German Lutheran churches in Philadelphia at the time, which together with St. Michael’s formed one congregation. Construction began on the first church, St. Michael’s, following the arrival of Lutheran minister and German émigré Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (1711–1787) in November 1742 (fig. 2). Appalled by the “leaky slaughterhouse” in which the members of the congregation had been worshipping, Muhlenberg led them to acquire a lot on Fifth Street at Appletree Alley and embarked on the construction of a church. Dedicated in 1748, St. Michael’s was an impressive brick edifice that cost a substantial £1,607 to build and measured 45 by 70 feet (fig. 3). It was also the first church in Philadelphia to have a steeple tower, although the weight of the tower caused the walls to bow and it had to be removed in 1750. Although the church had a seating capacity of eight hundred, it was soon overcrowded. A brick schoolhouse was built in 1761 to provide additional space, and in October 1765 the front pews were altered to accommodate more people. The congregation was becoming so large that these measures proved insufficient, even with the use of a third building (Whitefield Hall or New Building at the College of Philadelphia), so they acquired a nearby lot at Fourth and Cherry Streets on which to build a new church (fig. 4). Robert Smith was hired as the architect, and construction began in 1766. When completed, Zion measured 108 by 70 feet and had seating capacity for twenty-five hundred; it was one of the largest public buildings in the country and cost more than £9,500. The church was dedicated on two successive days in June 1769, with services held in German the first day and in English on the second. Inside, eight large fluted columns supported the arched ceiling, while the galleries were ornamented with a Doric entablature. The brick exterior was also grand, with Venetian windows, brick pilasters, and ornately carved pediments and cornices. A balustrade of urns ran along the roof. Less than ten years after it was completed, Zion was taken over during the British occupation of Philadelphia and used as a hospital, service that wreaked havoc on the interior. It was repaired and a service of thanksgiving held there on December 21, 1781, following Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.

In 1786 the congregation hired David Tannenberg (1728–1804), a Moravian, to make what would be the largest and finest organ built in eighteenth-century America. With three manuals (or keyboards) and thirty-four stops, it was Tannenberg’s masterpiece and cost the congregation a staggering £1,500—not including the case. Master joiner George Vorbach/Forepaugh (ca. 1741–1817), who was a member of the congregation, built the case. Measuring 24 feet wide, 27 feet high, and 8 feet deep, the case had five towers and more than one hundred pipes. On the central tower was a painting of the sun rising above the clouds, flanked by gilded eagles and trumpeting angels on the side towers. A skilled craftsman, Vorbach was a member of the Carpenters’ Company of Philadelphia and in 1787 oversaw the construction of the senate gallery in Congress Hall. The dedication of the organ in October 1790 was held over three days to accommodate the large crowds who attended, and Michael Billmeyer of Germantown printed a special pamphlet in German for the occasion. Although the organ was lost in the fire of 1794, some sense of its scale and grandeur can be found in the organ of Trinity Lutheran Church at Lancaster (fig. 5).[2]

In an impressive campaign of one-upmanship, Trinity Lutheran commissioned an organ with twenty stops from Tannenberg in 1771; two years earlier, the German Reformed church in Lancaster had hired him to build them an organ with fifteen stops. Whereas the latter organ had a case made for £50 by local cabinetmaker George Burkhardt (d. 1783), the Lutherans hired Peter Frick (1743–1822), who had recently moved to Lancaster from Germantown, to build the case. A masterpiece of cabinetwork for which the church paid £210, the case has fluted columns on the lower half, elaborate moldings, carved and pierced overlays, and ornate finials on each of the five towers. The carving is strongly reminiscent of Philadelphia workmanship, and some of it may even have been executed there, as a payment was made in January 1774 for transporting “wood or wooden parts” for the organ from Philadelphia (fig. 6). The organ was dedicated in December 1774 and at the time was the largest built in America. Four years later, it overwhelmed a British lieutenant who saw the church interior. He wrote: “the large galleries on each side, the spacious organ loft, supported by Corinthian pillars, are exceedingly beautiful . . . . The church, as well as the organ, painted white with gilt decorations, which has a very neat appearance . . . the organ is reckoned the largest and best in America. . . . It is the largest, and I think the finest I ever saw, without exception.”[3]

Following the devastating fire at Zion Church in 1794, the congregation decided to rebuild and hired master builder William Colladay to oversee the project. The organ, which Tannenberg offered to rebuild for £3,000, was postponed for financial reasons and not completed until 1811. On November 27, 1796, the rebuilt church was consecrated. Three years later, on December 26, 1799, some four thousand people crowded into Zion to attend the state memorial service for George Washington, following a funeral procession that began at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). Bishop William White, rector of Christ Church, led the service, and General Richard Henry Lee of Virginia delivered his famous eulogy from the pulpit. Eight years earlier, on March 22, 1791, a large crowd had gathered at Zion for Benjamin Franklin’s memorial service. A photograph of Zion taken in 1866 during the church’s centennial celebration shows the post-1794 interior, with its elegant wineglass pulpit and sounding board topped with a gilt blaze finial and neoclassical ornament on the galleries (fig. 7). Little else is known about the interior, as Zion was torn down in 1869; three years later, St. Michael’s would suffer the same fate.[4]

Ethnicity and Identity

With the loss of these two buildings, the most tangible vestiges of Philadelphia’s German-speaking community disappeared and its heritage was increasingly forgotten. Scholarship on the mid-Atlantic region has long since operated under a pervasive myth of English-speaking dominance. Most studies of Philadelphia have perpetuated this problem by emphasizing the city’s Quakers and Anglicans to the near-total exclusion of its sizable German-speaking population. Monolithic stereotypes of Philadelphia as the “Quaker City” obscure the German presence, and the oft-repeated description of Quaker decorative arts—“of the best Sort, but Plain”—continues to hold sway. There is also a corresponding assumption that German-speaking people were all peasant farmers who furnished their houses with nothing but painted chests, colorful pottery, and other folk art (figs. 8, 9). The notion of sophisticated, urban objects made or owned by people of German heritage is rarely considered, a misconception revealed in statements such as “in the Germanic communities of Pennsylvania, rococo ornament was seldom employed, and then usually only on special commission.” Surviving objects—including long rifles, stove plates, silver, furniture, and even some fraktur—reveal that, on the contrary, Pennsylvania German artisans and status-conscious consumers both made and acquired objects with rococo designs (figs. 10, 11). Lancaster in particular became a center of rococo-inspired furniture, initiated by “Germanic craftsmen working for Germanic patrons, under the influence of Philadelphia-oriented taste setters.” Pennsylvania German entrepreneurs also made goods that appealed to a wide range of consumers, such as ironmaster and glassmaker Henry William Stiegel of Manheim. Some of the most elaborate rococo ornament made in Pennsylvania was on iron stoves cast at his Elizabeth Furnace (fig. 12). Although some of these stoves were made from molds carved in Philadelphia, it would be a mistake to assume that only English-speaking customers bought them, as stoves for heating were by far preferred by Germans and no examples made by Stiegel are known with a history of ownership in a non–German Pennsylvania family. Indeed, Stiegel may have been targeting wealthy Pennsylvania German customers by combining their preferred heating technology with the most fashionable ornament.[5]

A common misconception about German furniture craftsmen in Philadelphia is that those who “did well were assimilated to some degree into the dominant English community, either through business connections, kinship ties, or religious affiliation,” because “in order to be tied into the city’s economic base, German woodworkers needed an English clientele.” The Pennsylvania Germans, especially those living in Philadelphia, are generally assumed to have “rapidly assimilated,” thus implying a declension model in which Germanic identity gradually lessened and was ultimately subsumed by a dominant Anglo-American culture. Many historians and material culture scholars have clung to a tripartite model of immigrants’ adaptation to life in America: rejection of the new culture, rapid assimilation, or a “controlled acculturation” that attempted to moderate between assimilation and rejection. As Bernard L. Herman and others have argued, the problem with such interpretations is that they assume the dominance of Anglo-American culture and ignore the significant impact that German-speaking immigrants had on their non-German neighbors. Historian Steven Nolt argues that during the early national period, German-speaking immigrants and their descendants developed a distinctive Pennsylvania German identity in a process he terms “ethnicization-as-Americanization.” The latter viewpoint enables us to consider the Pennsylvania Germans as active participants in the construction of American identity, rather than as merely reacting against it or being absorbed within it. This is strongly supported by the material evidence in Philadelphia, which reveals that German-speaking people played a vital role in the formation of the city’s multicultural, cosmopolitan identity. Fashioning themselves as “representative Americans,” the Pennsylvania Germans became Americanized without having to assimilate, retaining distinctive traditions and “alternate, ethnic visions” of what it meant to be an American.[6]

Philadelphia’s Germans

Founded in 1682 by William Penn, Philadelphia was the capital of the most culturally diverse of the thirteen British colonies in North America. By 1750 it was the largest city in the colonies and one of the major seaports. Settlement grew rapidly along the banks of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers (figs. 13-15). Although New York would surpass it in size by 1810, Philadelphia remained the country’s most important hub of manufacturing, finance, and international trade—some seven hundred ships arrived each year—well into the 1800s. It was also the social capital of the region and the political capital of the United States during the 1790s.

German-speaking immigration began in 1683 with the establishment of Germantown, about seven miles northwest of Philadelphia, by a group of German Quakers and Mennonites. For the next twenty years, relatively few Germans, probably no more than three hundred, arrived, but a severe winter in Germany in 1709 prompted a second wave of immigration (initially to New York). The third and largest influx of Germans to America began in the 1720s and continued until the outbreak of the Revolution, peaking from 1749 to 1754, when some 35,000 Germans arrived in Pennsylvania. About 81,000 of the estimated 111,000 Germans who immigrated to America before 1783 settled in Pennsylvania.[7]

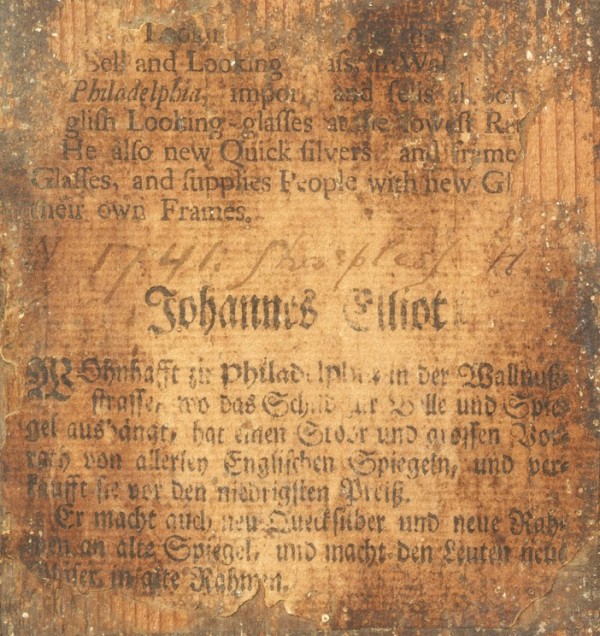

As early as 1717 Quaker merchant Jonathan Dickinson of Philadelphia predicted, “We shall have a great mixt multitude.” The increasing German population during the 1740s led Benjamin Franklin to fear that they would “shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them.” In 1751 he complained that the “Palatine Boors . . . swarm into our Settlements and, by herding together, establish their Language and Manners, to the Exclusion of ours.” Perhaps Franklin was disgruntled that his efforts to establish a German-language newspaper in 1732 had failed, outdone by Christopher Saur Sr. (1693–1758) of Germantown, who began printing in 1738 and started a German-language newspaper the following year. One German immigrant writing about Philadelphia in 1754 reported, “in this city and in this part of the country one can see people from every part of the entire world, especially Europeans. . . . The greatest number of inhabitants of Pennsylvania is German.” To serve this diverse population, savvy businessmen such as the looking glass retailer John Elliott used labels printed in both English and German (figs. 16, 17). This bilingual tradition continued to the end of the century. In 1772 Godfreyd Richter offered his services “to those Gentlemen who incline to learn the GERMAN LANGUAGE; and as it has been his chief study, they may depend upon due care, and the true pronunciation.” Pamphlets printed in both English and German were distributed to the crowd of onlookers who attended the Grand Federal Procession in Philadelphia on July 4, 1788.[8]

The ethnic and cultural identity of these German-speaking immigrants was complicated by a number of factors. German-speaking Europe was then subdivided into hundreds of territories under the rule of semiautonomous kings, bishops, dukes, margraves, and others. This political fragmentation tended to promote regional rather than national identity, which was compounded by the presence of multiple dialects and religious beliefs (fig. 18). Most Lutheran and Reformed immigrants came from the Palatinate, Kraichgau, and Württemberg regions of southwestern Germany as well as the Alsatian region of eastern France. The Mennonites and Amish came primarily from the German-speaking cantons of Bern and Zurich in Switzerland, the Moravians from Bohemia and Moravia, and the Schwenkfelders from Silesia (modern-day Poland). Before these immigrants could become Pennsylvania German, they had to develop a shared sense of German identity. This process began during their shared migration experiences and was fostered by participation in German-speaking churches and organizations such as the German Society of Pennsylvania (est. 1764) or the German-speaking Hermann Masonic Lodge no. 125 (est. 1811). German-speaking craftsmen also sought patronage from other Germans, such as Philadelphia clock- and watchmaker Frederick Dominick, who in 1768 encouraged his “Landesleute, die Deutschen” (countrymen, the Germans) to patronize him. A sense of common German identity was also promoted by English-speaking Philadelphians, who routinely lumped the immigrants together by referring to them all as “Germans” or “Palatines.” Under these circumstances, linguistic and other differences quickly “faded into the background as the distinctions between them and their English-speaking neighbors moved into the foreground.” The blending of Germanic dialects, religious faiths, and cultural traditions combined with New World realities led by the early nineteenth century to the formation of a hybrid Pennsylvania German culture.[9]

Although most German-speaking immigrants who arrived in Philadelphia soon settled in the surrounding backcountry, a sizable number stayed in the city. In 1730 approximately 15 percent of Philadelphia’s population was German; by 1740 this grew to 25 percent and in 1750, 35 percent. Spurred by massive waves of immigration and natural increase, Philadelphia’s German population reached a height of 45 percent in 1760. Immigration was disrupted by the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution, but in 1800 people of German heritage vied with those of English ancestry as the largest ethnic group in Philadelphia, with both populations estimated at 32 to 35 percent of the total 68,000 residents. The single largest religious denomination in 1800 was German Lutheran, at 12.6 percent of the city’s entire population. German Reformed comprised 8 percent, while Episcopalians measured 10.5 percent and Quakers only 6.6 percent. A small percentage was Mennonite, Moravian, Catholic, Jewish, or Schwenkfelder. These numbers differed only slightly from the regional concentration of German-speaking people in southeastern Pennsylvania, which in 1790 was approximately 40 percent German, 30 percent English, and 18 percent Scots-Irish. At the same time, estimates of religious affiliation in southeastern Pennsylvania are about 30,000 Quakers (9 percent), 60,000 Presbyterians (19 percent); and 85,000 German Lutherans or Reformed (26 percent). By 1815 Philadelphia’s population had grown to approximately 100,000 but remained 20–30 percent German. More immigration following the end of the Napoleonic Wars increased these numbers; in 1847 it was estimated that one-third of Philadelphians were of German origin and 80,000 understood the German language. The presence of so many German-speaking people—who largely did not settle in ethnic enclaves within the city but wherever space permitted—had a profound effect on the ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and religious balance of the city.[10]

This German-speaking population also had a tremendous impact on Philadelphia’s material culture. Many of the leading craftsmen in Philadelphia were of German birth or heritage, including clockmaker Jacob Godschalk, pewterers William Will and Johann Philip Alberti, and silversmith Christian Wiltberger. Jacob Knorr, a master carpenter from Germantown, was the builder of Cliveden, the country house of Benjamin Chew, as well as the Germantown Academy in 1760–1761. Most scholarship, however, has focused on nonurban Pennsylvania German material culture. Benno Forman complained of this problem more than thirty years ago, writing, “virtually no recognition has been accorded the German craftsmen who disembarked from the ships in Philadelphia and never left the town, and their influence on the most sophisticated furniture-producing community in eighteenth-century America has never been considered a possibility.” He continued, “No one has even suggested that it might have been the presence of German craftsmen or German ideas in Philadelphia that made the furniture of that metropolis unique in colonial America.” Before his death in 1982, Forman argued persuasively that the ubiquitous slat-back chairs made by Solomon Fussell (d. 1762), his apprentice William Savery (1721/22–1787), and others were a direct result of German influence (fig. 19). He found that although slat-back chairs were made in other regions, those from southeastern Pennsylvania differed in having tapered stiles, slats that were arched on both the top and bottom, and arms that were undercut at both ends, rather than just at the front. Forman attributed these features to the German presence, citing related German chairs as well as an early portrait of Germantown resident Johannes Kelpius (1673–1708) seated in a slat-back armchair (fig. 20). Forman also contended that Fussell may have been of Germanic heritage, as the surname can be documented in both Germany and Switzerland in the early 1700s but not in England. He hypothesized that the distinctive seat-framing techniques used to make compass seat chairs in Philadelphia could also be traced to the influence of émigré German craftsmen. Building on his work, Désirée Caldwell concluded that these chairs were a combination of Germanic construction techniques and English design principles.[11]

The period from 1740 to 1820, however, remains largely unexplored in terms of German furniture in Philadelphia. A complex web of language, ethnicity, religious beliefs, and family ties helped shape the contours of a world that was neither German nor English but, rather, American. Many of the resulting objects were an amalgam of Continental and British forms, construction techniques, and ornament within the locally specific context of Philadelphia taste and patronage. Through a detailed investigation of three distinct groups of furniture made by German cabinetmakers in the Philadelphia area, the following article will attempt to resurrect some of this lost history while reevaluating our understanding of Philadelphia and its furniture in the process.

Early Inlay

Although the first permanent German settlement in Pennsylvania was established in 1683, few examples of Pennsylvania German furniture made before 1740 are known to survive. Chests brought over by immigrants were a common early storage form, but fewer than ten documented ones are extant. Among the earliest known surviving examples of Pennsylvania German furniture is a walnut chair that descended in the family of John Bernhard Reser (ca. 1685–1761) of Germantown, who emigrated from Schwarzenau in the late 1720s. With its raised panel back and elongated baluster turnings, the chair likely dates to the 1730s or 1740s (fig. 21). The base of the chair—turned legs, stretchers, and plank seat set within a frame—resembles that of some wainscot chairs made in Chester County, Pennsylvania, including one owned by Irish Quaker Joseph Pennock (fig. 22), but the turned rear stiles and raised panel back distinguish the Germantown chair as a more fully developed example. The narrow, vertical shape of the paneled back is also unlike the broad, horizontal back of a typical wainscot chair. It may be the work of a turner such as Johannes Bechtel (1690–1777), who trained in Heidelberg, Germany, before settling in Germantown in 1726. He later joined the Moravian church and in 1749 moved to Bethlehem.[12]

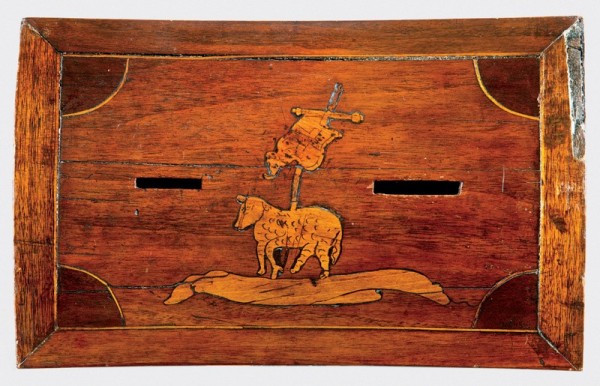

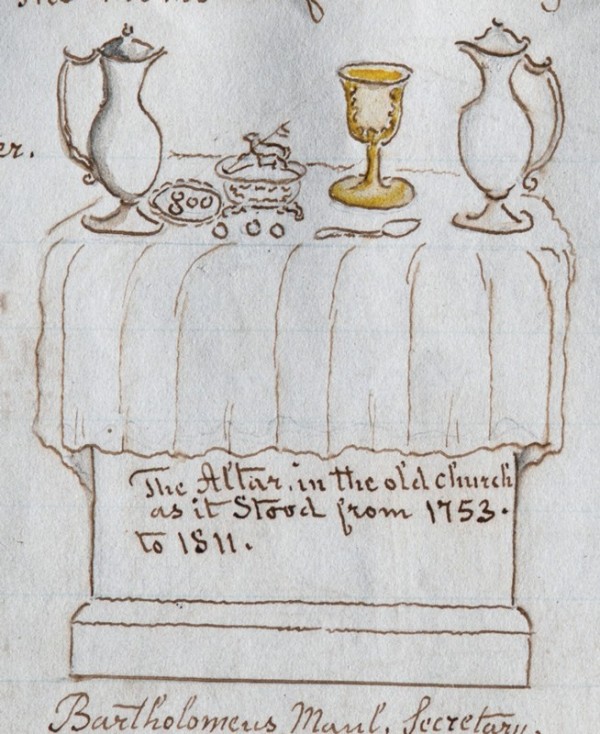

Another early object, probably built in Philadelphia by a German émigré craftsman, is a small, domed-lid chest made for St. Michael’s Lutheran Church (fig. 23). The main body of the chest is inlaid with flowers on all four sides, and the lid bears an image of the Agnus Dei, or Lamb of God (fig. 24). Clearly intended for display in the round, the chest may have been used for the storage of communion wafers on an altar. A ciborium with figure of the Agnus Dei on the lid was among the early furnishings of Christ Lutheran Church in York, Pennsylvania (est. 1733). A drawing of the church altar by York artist Lewis Miller (1796–1882) shows the ciborium, with a paten, wafers, serving spoon, two flagons, and a chalice nearby (fig. 25). The right end panel of the St. Michael’s chest slides up to reveal a shallow compartment at the bottom, about the right size for storing a spoon (fig. 26). Several other Lutheran and Reformed churches in southeastern Pennsylvania had pewter communion vessels with the Agnus Dei engraved on them.[13]

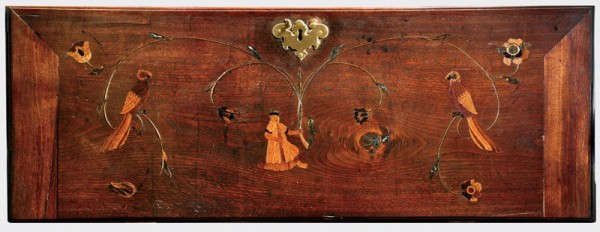

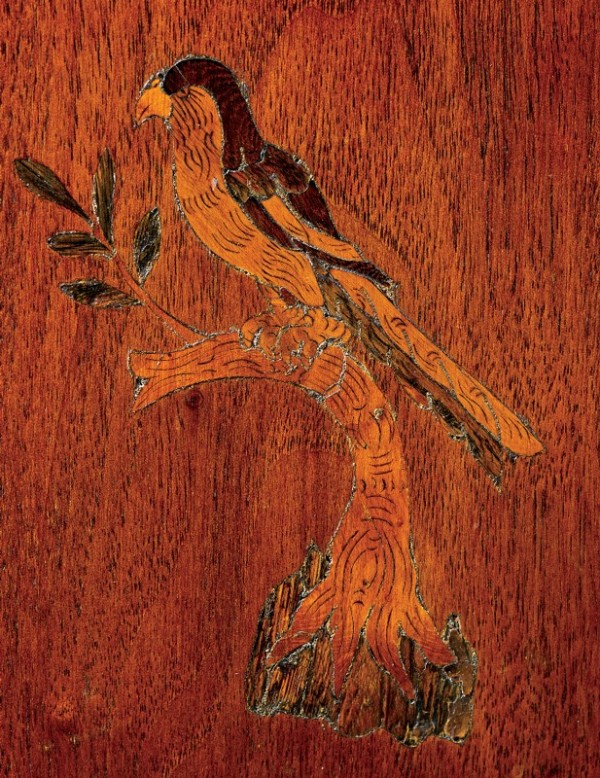

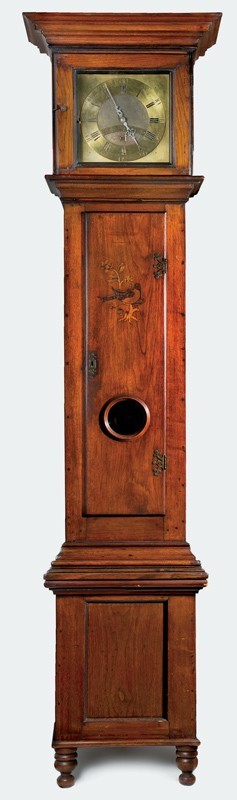

The earliest dated example of Pennsylvania German furniture is a clock case with “1740” inlaid on the top rail of the bonnet door, flanked by applied columns (fig. 27). The initials “I M C” are inlaid on the pendulum door along with flowering vines and a ruffled cartouche around the oculus. Closely related inlay is also found on a Kleiderschrank, or clothes cupboard, dated 1741 (fig. 28). This magnificent example of German baroque furniture has flat pilasters inlaid with flowering vines and large shells, flanked by ornately carved capitals and bases modeled after the Corinthian order (figs. 29-32). Together with the plain Tuscan-style columns on the clock hood, this carving indicates that the maker was familiar with academic design principles and the five orders of architecture, which were readily available in German translation. The inlay reflects the work of an émigré craftsman trained in traditional Continental marquetry, in which techniques such as scorching and line engraving are used to create detail and shading; this is particularly evident in the shells as well as the birds inlaid on the two raised panel doors (fig. 33). The bird on the left may represent the Carolina parakeet. The only parrot species native to North America, it was noted for its brilliant green body with red and yellow markings on the head and wings (fig. 34). Now extinct, the birds were common in Pennsylvania during the mid-1700s, when German immigrant Gottlieb Mittelberger described them as “grass-green ones, with red heads.” By the 1820s Carolina parakeets were increasingly rare, as farmers who considered them a pest decimated their flocks. Noted for their colorful plumage, these parrots were an inspiration to many Pennsylvania German artisans who put them on everything, from painted chests to fraktur drawings (fig. 35). The parrot on the right door is nearly identical to those on the lid of a slant-front desk, which also has closely related vines and flowers (figs. 36, 37). At the center of the lid is an inlaid human figure who grasps the base of the vine in his left hand; the inlay is so minutely detailed that even his individual curled fingers are discernible. The use of multiple woods for the inlaid flowers also yields a polychrome effect (figs. 38, 39). By comparison, the inlaid birds on two Lancaster County clocks, both dated 1755, appear rather crude and unsophisticated even though both were embellished with sand shading and engraving (fig. 40).[14]

Related inlay and structural details also appear on the door of a diminutive valuables chest or spice box, essentially a cabinet with small drawers for storing items such as coins and spices (fig. 41). The applied columns on either side of the paneled door resemble those on the clock hood, while the tiny inlaid bird relates closely to the parrots on the schrank—in particular, the use of line engraving to add detail to the feathers and tree stump (fig. 42). The cove molding that surrounds the raised panel door is also nearly identical to the doors of the schrank. Small brass knobs are on each of the seven interior drawers; the entire cabinet rests on four turned feet, all of which are original (fig. 43). Although this form is generally thought of in Pennsylvania as an English and typically Philadelphia or Chester County Quaker object, the inlaid ornament and its relation to the clock and schrank suggest that this example is of Pennsylvania German origin. The bold projecting cornice and base molding, use of large iron tulip-shape hinges, and drawer construction with tiny wedges driven into the pins of the dovetails are indicative Germanic craftsmanship. Small valuables chests were made in Britain as well as Continental Europe, which is likely where the maker of this box originated.[15]

Between 1700 and 1740, exotic birds were popular motifs for painted and inlaid furniture in Continental Europe (fig. 44). In Württemberg and Hohenlohe, bird motifs were so common that the term Papageieinschrank (parrot cupboard) came into use. Craftsmen did not have to work from live birds, as publications such as Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (London, 1729–1747) and George Edwards’s A Natural History of Uncommon Birds (London, 1743–1751) provided illustrations of both native and exotic species, including macaws, toucans, cockatoos, and various parrots. Many of the birds were depicted perched on a branch—like the taxidermy specimens from which they were typically drawn—and closely resemble their inlaid and painted counterparts. The parrot on the right door of the schrank and those on the lid of the desk appear to be based on the engraving “A Parroqueet from Angola” in Eleazar Albin’s A Natural History of Birds (fig. 45). Published in three volumes between 1731 and 1740, the book was widely popular in Europe and would have been available before the 1741 date of the schrank. Little is known of Albin himself. He is thought to be of German heritage, although by 1708 he was in London and counted both Catesby and Edwards as friends. The work of these three naturalists provided artistic inspiration for media other than furniture, including needlework, such as a pair of silkwork pictures made in 1752 by Sarah Wistar (1738–1815), daughter of German émigré Caspar Wistar (fig. 46).[16]

A Philadelphia-area attribution for these four objects is supported by the use of related motifs on the pendulum doors of two tall clocks, one with a movement by Augustin Neisser (1717–1780) of Germantown and the other by Joseph Wills (1700–1759) of Philadelphia (figs. 47, 48). The door of the Neisser clock case is inlaid with a bird perched on a flowering branch. A nearly identical bird is inlaid on the Wills clock, above a pastoral vignette complete with buildings, agricultural fields, and a fence (fig. 49); the wood has been dyed to achieve a polychrome effect. The elaborate foliate inlay surrounding the oculus (fig. 50) bears a strong relation to the work of French designer Jean Bérain (1637–1711), whose published engravings were highly influential in western Germany, Switzerland, the Low Countries, and London during the first half of the eighteenth century. A page of Bérainesque designs for cartouches is extremely similar to the cartouche on the clock (fig. 51). Comparable, albeit more elaborate, Bérainesque motifs also appear on German furniture at this time, including a Rhenish tabernakelschrank made by Johann Georg Wahl (1702–1773) in 1743 (fig. 52). Although the Neisser and Wills clock cases appear to have been made by a different craftsman than the other inlaid group (see figs. 27, 28, 36, 41), the inlaid decoration, robust moldings, and ample use of wooden pegs in their construction suggest that all were built by craftsmen of Germanic heritage. The presence of Wills clock movements in several closely related clock cases, including one in the Yale collection whose cornice is nearly identical to that of the clock in figure 48, indicates that the maker was from the Philadelphia area.[17]

Both Neisser and Wills had close ties to the German-speaking community. Neisser was born in Schlen, Moravia, in 1717 and moved as a young boy to the estate of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf in Herrnhut, where he joined the Moravian faith. He immigrated to America in 1736 and three years later settled in Germantown, where he worked as a clock- and watchmaker until his death in 1780. Wills was a native of South Molton Parish in Devonshire, England. Although many sources claim that he was in Philadelphia by the mid-1720s, the recent discovery that “Joseph Wills, clockmaker” of South Molton took an apprentice in 1729 suggests that he did not immigrate until the 1730s. Despite his English heritage, Wills was closely allied with Philadelphia’s German-speaking community. The records of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church list the death of his wife, Maria Dorothea, in 1757, along with the notation, “Her husband requested that they be buried in our churchyard.” The executors of Wills’s estate were Thomas Say and Maria Sophia Cogen/Gogen; Say was married to a German woman, Susannah Catharine Sprogell, and Maria Sophia Cogen/Gogen’s name is clearly also German. Because Wills had only one witness sign his will and not the required two, affidavits made by several acquaintances to confirm its validity reveal that Wills spent significant time in the area of New Hanover (now part of Montgomery County), where Lutheran schoolmaster Michael Walter and innkeeper Caspar Singer both knew him. Wills likely trained clockmaker Jacob Godschalk (d. 1781), who inventoried Wills’ estate and bought the time of his indentured mulatto servant, Benjamin. Born in Towamencin Township, in what is now Montgomery County, Jacob was probably the son of German immigrant Herman Godschalk.[18]

Although these objects appear to have been made by two different artisans, all exhibit a deep familiarity with Continental marquetry traditions and imply that they are the work of émigré German craftsmen. Multiple woods were used to achieve a polychrome effect, while a surface application of stain or dye was used to tint the leaves and birds’ plumage. This painterly technique may be an indication of the makers’ origins, as furniture from Württemberg and Hohenlohe from the early-to-mid 1700s is especially noted for using colored inlay as well as parrot motifs. In the second half of the eighteenth century, German Moravian cabinetmaker Abraham Roentgen (1711–1793) of Neuwied and his son David (1743–1807) would develop more vibrant and colorfast pictorial inlays with the use of penetrating dyes.[19]

Unfortunately, none of these objects has a firm provenance. Given the Neisser and Wills clock movements, together with the early dates, refined construction, and sophisticated inlay techniques, a Philadelphia-area origin is likely. Because Wills also had ties in the New Hanover area, which before 1784 was part of Philadelphia County, it is possible their origin may extend into what is now Montgomery County. The presence of inlaid initials on the 1740 clock and 1741 schrank (figs. 27, 28) enables further investigation and a tentative identification of the original owner in the case of the latter. The initials on the clock, “I M C,” stand for a married couple such as Johannes or Jacob and Catharina or Christina M ; numerous couples, however, fit these initials even at this early date. The initials on the schrank can be arranged as “AM MI” or “MI AM” because the drawers are interchangeable. Since it was common for full names to be abbreviated on furniture with initials (one schrank bears the initials “DV HS” for David Hottenstein), and since nearly all known documented schranks with initials or a name represent either the husband or both spouses, the original arrangement of the initials on this schrank was likely “MI AM.” Only one likely person has been found whose name fits these initials, Michael Amenzetter (1696–1784), a German immigrant who settled in Philadelphia and was a member of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church. His name does not appear in the lists of arrivals that Philadelphia began requiring in 1727, which means that either he immigrated before that year or he arrived in a different city. In 1741 Michael would have been forty-five, which is in keeping with the fact that schranks were typically acquired for established households rather than young couples. Unfortunately, although Michael’s death is recorded in the church records, no estate papers have been located.[20]

The accomplished carving and sophisticated figural inlay (which predates its use on federal furniture such as that by Bankson and Lawson of Baltimore by nearly fifty years) on these objects reveal the high level of craftsmanship that was executed by some German émigré woodworkers in America. This practice was not limited to Pennsylvania. Charleston, South Carolina, was also home to a sizable population of German émigré craftsmen, including cabinetmaker Martin Pfeninger (d. 1782), to whom is attributed a spectacular mahogany library bookcase with inlaid baroque strapwork and ivory husks (fig. 53). Given the elaborate pictorial inlay on furniture made by German craftsmen such as the Roentgens or Johann Friedrich Hintz, a Moravian working in London who in 1738 advertised furniture “inlaid with fine Figures of Brass and Mother of Pearl,” this should come as little surprise, but it is in sharp contrast with the furniture typically associated with the Pennsylvania Germans. Unlike the stereotypical painted chests, plank- bottom chairs, and other readily identifiable forms made by German-speaking craftsmen throughout southeastern Pennsylvania, the work of German craftsmen in Philadelphia can be difficult to recognize without documentation. Such is the case with a tall clock accompanied by a handwritten label inscribed, “This Clock Case Was made and Sould by William Bomberger 1765 In the Reign of King George the thirt anno domeny 1765 germantown all work and no play makes [illeg.] bould would you [illeg.] your plan [illeg.]; on the other side is written, “Made in Germantown 1765” (figs. 54, 55). The walnut case retains its original ogee feet and sarcophagus top with compressed ball finials and closely resembles several earlier clock cases housing movements by Joseph Wills and John Wood Sr.

Little is known about Bomberger beyond this label. In 1783 a “William Bomberger, carpenter” paid tax on a rented dwelling from turner Jacob Shoemaker’s estate. Three years later, Bomberger was described as a joiner and paid an occupational tax of £50. In the city directories he is listed variously as a carpenter or house carpenter, residing at 5 Elbow Lane (also known as White Horse Alley), from 1791 until 1801, with the exception of 1796, when he is listed as a joiner, and 1797, when his occupation is given as “sharpener of saws.” Starting in 1802 Bomberger is listed on Bank Street, which was another name for the north–south portion of Elbow Lane, where he remained through at least 1809. Without the label identifying this clock case as the work of William Bomberger, the ethnic identity of the cabinetmaker would be nearly impossible to determine. The following two case studies will explore this issue in more detail.[21]

Leonard Kessler

One of the leading German cabinetmakers in Philadelphia during the second half of the eighteenth century was Leonard Kessler, a member of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church. Born on September 4, 1737, Kessler emigrated from Germany circa 1750. His marriage to Anna Maria Ritschauer (1736–1825) on October 3, 1758, was witnessed by Reinhardt Uhl and his wife, Jacob Shoemaker, and the brothers Scheubele/Scheuffele. Both Reinhardt Uhl and Jacob Scheubele/Scheuffele (later Schieffelin) were Kessler’s brothers-in-law, married to his wife’s sisters, Christina Catharina and Regina Margaretta Ritschauer. The Schieffelin family Bible notes Regina’s birthplace as Mühlhausen an der Enz, a town in Württemberg; presumably all three sisters were born there and immigrated to Philadelphia. The name of the third party who attended the wedding, Jacob Shoemaker, is an important clue as to Kessler’s training as a cabinetmaker. No Jacob Shoemaker appears in the records of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church or the German Reformed Church in Philadelphia as a baptismal sponsor, communicant, or witness to a wedding except for this one instance, implying a relationship with Kessler other than that of a family member or coreligionist. Given that Kessler emigrated from Germany as a young man and would have apprenticed in Philadelphia, Shoemaker is very likely the man who trained him and can thus reasonably be identified as the turner Jacob Shoemaker Jr. (1692–1772), father of cabinetmaker Jonathan Shoemaker (1726–1793) of Philadelphia.[22]

Three generations of Schumachers/Shoemakers were woodworkers, beginning with Jacob Sr., who emigrated from Mainz in 1683 and was one of the original settlers of Germantown. A Quaker, he moved to Philadelphia circa 1715 and worked there approximately five years. In 1722 he bequeathed all of his “turning tools and all the other timber materials utensils and Tools belonging to the Trades of Turning and Wheel Making” to his son Jacob Jr., whose shop was located on Market Street next to that of Caspar Wistar, another German émigré. Jacob Jr. probably trained his son Jonathan, who signed the walnut chest-on-chest with shell-carved drawer and fluted quarter columns illustrated in figures 56 and 57. Jonathan was working as a joiner by 1750 and in 1752 acquired a shop on the west side of Second Street. In 1767 he relocated to Third Street near Arch. One of his apprentices, Samuel Mickle (1746–1803), made a series of furniture drawings that indicates his shop produced a variety of sophisticated furniture, including large case pieces and cabriole-leg chairs. An armchair that descended in the family of Jonathan Shoemaker has also been attributed to him, although attributions based solely on descent can be problematic (fig. 58).[23]

No signed or labeled furniture by Kessler is known, but the journals of Lutheran minister Henry Muhlenberg offer significant insight into his work. A member of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church, Kessler was the only cabinetmaker the Muhlenbergs are known to have patronized while they lived in Philadelphia from 1761 to 1776. In October 1762 Kessler was hired to build a chimney door for the parsonage; for this and other cabinetwork he was paid more than £12, some of which he returned to Muhlenberg as a contribution to the pastor’s salary. When five-year-old Johann Enoch Samuel Muhlenberg died in February 1764, Kessler built the coffin. On October 22, 1765, the church council passed a resolution that charged “Mr. Ehwald and Mr. Kessler, two master carpenters . . . with supervising the alterations in the pews in the front section of St. Michael’s Church” (an attempt to add more seating until Zion Church was built). On January 21, 1763, Muhlenberg paid Kessler £10.2.6 for “new chairs.” At least six chairs from this set are known, one of which is marked “xii,” indicating that it was a set of twelve or more (fig. 59). Made of mahogany, the chairs have through-tenoned side rails, two-part vertical glue blocks, and compressed ball-and-claw feet typical of Philadelphia chairs. They are ornamented with an interlaced scroll splat, fluted rear stiles, a rffled shell on the crest, and carved shells on the knees and front seat rail. Although £10.2.6 seems a low price for twelve mahogany chairs with this level of embellishment (which, according to the 1772 Philadelphia price book should have cost more than £25), Philadelphia was in a postwar economic depression in the early 1760s and artisans struggled to make ends meet. Kessler may have charged Muhlenberg a lower price for the chairs simply because he needed the work, or he may have given his pastor a discount. Muhlenberg paid for the chairs in January, the time of year when parishioners often contributed toward his salary. Although much more elaborate chairs were available in Philadelphia, these chairs do have a number of embellishments and would have been well suited to Muhlenberg’s relatively modest means. A large set of chairs would have been a necessity for the minister, who frequently hosted sizable groups of visitors at his home. Muhlenberg was also keenly aware of the need for keeping up appearances, remarking that when in the city he “would not dare” wear the clothing his wife made for him “unless I wanted the children on the streets to laugh at me behind my back.”[24]

The Muhlenberg chairs have a number of distinctive features, including structural details that identify seating from Kessler’s shop and, likely, that in which he trained. At the rear inside corners of the seat frame, thin strips of wood occupy the space created by the overlapping shoe and serve as a foundation for larger glue blocks. The chairs are also distinguished by having flared, scrolled ears decorated with four pairs of crescent-shaped chip cuts, the topmost pair being located on the apex of the ear and not visible from the front; pierced splats with large scroll volutes and high, straight plinths; scallop shells with unusually small flanges on the front seat rail; and the ball-and-claw feet with pronounced knuckles. The cartouche on the crest rail was derived from those on chairs with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, but subtle differences help distinguish his work from Kessler’s (figs. 60-62). On the Muhlenberg chairs, the volutes flanking the leaf at the bottom are slightly overscale, like those on the splat, and the concave sides of the cabochons are gently curved, rather than sharply peaked, at the waist. Using the Muhlenberg chair as a basis for identification, it can be seen that Kessler made less ornate chairs, including a mahogany one with plain rear stiles and no carving on the knees (figs. 63, 64). This format is identical to that of six walnut chairs from another set. Similarly, a mahogany side chair with comparable carving and a solid splat descended in the Morris family of Philadelphia (fig. 65). As will be discussed below, significant evidence suggests that Kessler was both a cabinetmaker and a carver, making it plausible that he made and carved the Muhlenberg chairs and those illustrated in figures 63–65.[25]

Documentary evidence sheds light on Kessler’s interactions with other cabinetmakers, both German and English. In 1769 he witnessed the will of joiner John Gaul. Eleven years later, Kessler and Anthony Leckler inventoried the stock of Johann Michael Barendt/Behrendt, a joiner and musical-instrument maker. Behrendt’s will had stipulated that “all my Tools of my Trade shall be particularly mentioned in the Inventory or Appraisement of my Estate and be put up and carefully kept . . . for the use of my beloved son John.” Thus, Kessler was likely selected for this task because of his knowledge of woodworking tools. The following year, carpenter George Adam Pfister appointed as executors of his estate “my worthy and Esteemed Friends Leonerd Kessler of the said City Cabinetmaker and Michael Bowes of the same Place Victualler,” together with his wife. When Benjamin Randolph’s tools, lumber, hardware, and other shop equipment were dispersed in 1778, Kessler was paid “for a lot of carved work to be sold at auction” by the vendue master, John Ross.[26]

Starting in October 1779, Kessler began working for David Evans (1748–1819), a Quaker cabinetmaker who lived and worked at 115 Arch Street. In 1780 Evans paid him £228 for walnut boards and glue along with “12 Back feet Walnut—£47.6,” “2 Pillars Walnut—£7.10,” and “12 Chair Legs—£26.5.” The following year, Evans owed Kessler £285 for “Framing Slate” and making coffins that ranged from £22.10 for a poplar one to £37.10 in walnut and £75 in mahogany. Evans also owed Kessler £75 for four days’ work on three separate occasions in 1780. Even with price inflation due to the war, this amount is remarkably high and may reflect the fact that Kessler was being paid master’s rather than journeyman’s wages. The payments for tea table pillars and chair legs, together with the carving work that Kessler did for Randolph, clearly indicate that he was both a carver and a cabinetmaker. In February 1782 Kessler made “1 Corded bonnet bedstead.” He also built significant case pieces, as indicated by a payment of £22 for a desk made for Friederich Schenckel, a maker of leather breeches in Philadelphia. It was described as a mahogany desk-and-bookcase and valued at $25 when Schenckel died in 1810. A final indication of Kessler’s range of work is suggested by the inventory taken when he died in 1804. In addition to “One lot Joiner’s Tools (very old),” valued at fifty cents, there was an extensive list of furniture, including an eight-day clock and case, desk-and-bookcase, six chairs, a chest of drawers, two bureaus, two tea tables, a stand, fire screen, and chest—all of mahogany—together with twelve chairs, a bureau, table, and tea table in walnut. Likely most, if not all, of this furniture was made by Kessler, as it made good business sense for a cabinetmaker to make pieces for his own household rather than pay someone else to do it. One of Kessler’s sons, Michael (1764–1793), became a cabinetmaker, but little is known of his work. Michael is listed in the 1791 Philadelphia City Directory as a joiner, residing at his father’s address of 125 Arch Street; he died in 1793 during the yellow fever epidemic.[27]

One way to measure Kessler’s success as a craftsman is to compare his occupational tax, which was based on yearly income, with that of other cabinetmakers. Topping the list in 1783 was Thomas Affleck at £250, followed by Benjamin Randolph and George Claypoole at £200 each. Kessler was one of eleven woodworkers who paid a tax of £100; others include David Evans, Jonathan Gostelowe, and Francis Trumble. Daniel Trotter was taxed at £75, while the majority of woodworkers were taxed at £30 to £50. Kessler paid additional tax on his dwelling and lot, a cow, and five ounces of silver plate. With the exception of Trumble, a Windsor chairmaker who in 1783 was sixty-seven years old, this cadre of woodworkers was relatively close in age: the youngest, David Evans, was thirty-five; Affleck was forty-three; Randolph and Kessler were both forty-six; and Claypoole was fifty. By 1786 Kessler’s business had apparently declined, since he paid a tax of £50, the same as Evans, while Gostelowe and Trotter were both now taxed at £100. Affleck’s business was also down significantly, taxed at £122, and Randolph was not even listed.[28]

Another method of assessing Kessler’s success is to compare the insurance records for his house with those of other cabinetmakers. In 1765 Kessler took out an insurance policy with the Philadelphia Contributionship, established in 1752 by Benjamin Franklin, for his “Dwelling house, Kitchen and Work Shop” located on the north side of Arch (or Mulberry) Street between Third and Fourth Streets. The house was three stories tall and measured 15 feet wide by 25 1/2 feet deep. On the first floor, the front room was “partitioned off for a Shop with Bord partition,” while the back room had a “Brest Sirbace and washbord.” The second storey, accessed by stairs of the “Common winding sort,” had a front room with “Brest wash bord Sirbace & Single Cornish Round the Room.” This concentration of carpentry work, together with a notation that the second storey was painted, indicates that this was the best room. Behind a plaster partition was a small back room “without any Carpentry.” The third storey had a “Brest & Washbord,” and the garret had one room that was plastered and had a board partition. Behind the house was a kitchen that measured 11 by 16 feet, two and a half stories high; there was also a two-storey frame workshop of 19 feet 6 inches by 15 feet. The three buildings were together insured for £200, the house at £150, kitchen at £35, and shop at £15. By the time the property was resurveyed in 1772, wainscoting had been added to one of the rooms and the kitchen expanded to 27 feet 6 inches by 11 feet. The house and kitchen totaled 1,752 square feet of living space (not counting the attic), with an additional 588 square feet for the workshop. This puts Kessler squarely in the category of middling-to-wealthy families, who on average occupied three-storey houses of approximately 2,000 square feet. By way of comparison, the average Philadelphia laborer occupied a two-storey house of about 500 square feet.[29]

In 1763, only two years before Kessler took out his policy, chairmaker and joiner William Savery insured his new, three-storey brick house on Third between Walnut and Spruce. Measuring 18 by 33 feet, the house—together with a two-storey kitchen of 17 1/2 feet by 11 feet—were insured for £400 and measured a total of 2,167 square feet. Savery’s old two-storey house, on Second between High and Chestnut, measured 12 feet 3 inches by 37 feet and was described as having “No Sirbase Washboard or Chimney Except Belo” (probably in the front parlor); it also had a two-storey kitchen of 16 by 9 feet. The policy also noted Savery’s “Cheer Makers Shop,” which measured 26 by 9 1/2 feet; it was three stories tall, the first of brick, the other two levels of wood. Thus, Kessler’s house and kitchen in 1765 were both larger and more highly finished than Savery’s old house, but not quite as large as his new house. Savery’s workshop was also slightly larger than Kessler’s, totaling 741 versus 588 square feet. The footprint of their two workshops was quite different, Savery’s being long and narrow, whereas Kessler’s was nearly square, likely owing to the difference in their trades as chairmaker and joiner respectively. Savery probably used the upper levels of his three-storey shop as spaces for allowing chair lists and rungs to dry while turning took place on the ground floor. Although the layout of Kessler’s workshop is unknown, its two-storey construction provided a space for lumber storage above the main work floor. The first-floor front room of Kessler’s house, which was “partitioned off for a shop,” provided additional space for him to interact with customers, tend to his accounts, and display examples of his work.[30]

As relatively few Philadelphia cabinetmakers had insurance with the Contributionship, it is rare to have this level of detail for their buildings and work spaces. Two other policyholders were Benjamin Randolph and Daniel Trotter. One of the leading cabinetmakers in Philadelphia, Randolph owned a large, three-storey brick house, located on the north side of Chestnut Street between Third and Fourth, which measured 25 by 40 feet. It was finished with wainscot paneling, cornices, pilasters, and “Tabernakles,” or overmantels on the chimneybreasts. In 1772 his policy valued the house together with a two-storey kitchen and washhouse at £1,000 and included the addendum, “No Carved Work, Gilding or History Painting ensured”—implying that such luxuries were present. By contrast, the 1784 survey of Trotter’s property on Elfreth’s Alley described his house as two stories high and measuring only 19 1/2 feet wide by 17 feet deep. It was finished in a manner similar to Kessler’s house but included “Newell Stairs.” There was also a two-storey kitchen of 11 by 15 feet, giving Trotter a total of 993 square feet of living space versus Kessler’s 1,752.[31]