Detail of a mantlepiece from Woodcote Park, Surrey England; attributed to Sir Henry Cheere, England, ca. 1750. Marble. (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved. Gift of Eben Howard Gay, 27.462.) The room and mantel of the house are both in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Engraving of “The Dog and Shadow” in Wencelaus Hollar, Aesop Paraphras’d (London, 1665). (Courtesy, Peabody Library, Baltimore.)

Front plate of a ten-plate stove, marked “H. W. STIEGEL/ 1769/ELIZABETH FURNACE,” Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. (Courtesy, Hershey Museum, Hershey, Pennsylvania.) Courtenay undoubtedly carved the pattern in Philadelphia

Detail of the tablet on the chimneypiece from the parlor of Samuel Powel’s townhouse, Philadelphia, 1770. Pine. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) Between August and October 1770, Powel paid Courtenay £60 for carving in his “dwelling” (Samuel Powel Ledger, 1760–1793, Library Company of Philadelphia). The chimneypiece is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Francis Barlow, “The Dog and the Meat,” from Aesop’s Fables, 2d ed. (London, 1687). Etching. (By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.)

Elisha Kirkall, “The Dog and the Shadow,” from Dr. Samuel Croxall, trans., Aesop’s Fables, 1st ed. (London, 1722). Metal cut in white line. (Private collection.)

Design for a “French” chair on plate 22 of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, 3d. ed. (London, 1762).

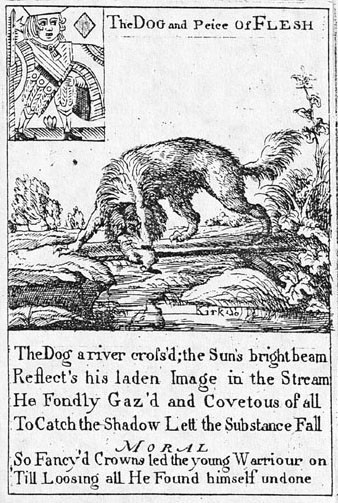

Kirk, playing card depicting “The Dog and Piece of Flesh,” London, 1759. Engraving. (Courtesy, United States Playing Card Collection.)

Throughout the eighteenth century, the proverb, the adage, and the wise saying were popular daily fare. Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac was read widely, both for entertainment and sage advice. In 1751 Poor Richard noted that “ambition often spends foolishly what avarice had wickedly collected.” This observation might well have been the moral of the Aesop’s fable “The Dog and the Meat,” or “The Dog and His Shadow,” as it is sometimes called, wherein a dog with a succulent piece of beef in his mouth sees his reflection in a stream. Thinking it is another dog with a fine morsel, he relinquishes what he has and jumps into the water to seize the other, only to end up with nothing.

Such fables were often depicted in architectural interiors. An early representation of “The Dog and the Meat” appears on a colored marble chimneypiece (fig. 1) originally installed in Woodcote Park, Lord Baltimore’s house in Epsom, Surrey. The house was designed by Isaac Ware and completed about 1750. The chimneypiece is attributed to Sir Henry Cheere, who based his design on an engraving in Wencelaus Hollar’s Aesop Paraphras’d (London, 1665) (fig. 2).

This particular Aesop fable appeared twice in Philadelphia, first on the front of a ten-plate stove cast by William Henry Stiegel at Elizabeth Furnace in 1769 (fig. 3), and again on the chimneypiece tablet that London-trained carver Hercules Courtenay furnished for Samuel Powel’s townhouse in 1770 (fig. 4). Not only are the posture of the dog and the position and configuration of the mill in the background of the stove plate and tablet remarkably similar (despite the shift from a vertical to a horizontal format), but the techniques used to carve the casting pattern match those used on the tablet. Powel began renovating his house soon after purchasing it from Charles Stedman, Stiegel’s partner in Elizabeth Furnace.[1]

Courtenay’s design source was the illustration for “The Dog and the Meat” in one of Francis Barlow’s London editions of Aesop, issued in 1666 and 1687 (fig. 5). Barlow brought his skill as an observer and a painter of animals into full play in his books, which depicted, in a new and original manner, the wild and tame creatures naturalistically involved in the actions of the stories. With its large etched plates and wide circulation, Barlow’s Aesop had a profound impact on book illustration, affecting readers and artists for nearly two hundred years.[2]

Although no eighteenth-century Philadelphia library or estate inventory listed Barlow’s book, Aesop’s fables were popular there. James Logan owned Latin and French editions of Aesop (the former dated 1698); James Cox and Deborah Logan owned English versions; the Library Company of Philadelphia owned the third edition of Dr. Samuel Croxall’s translation (London, 1731); and the Biddle family owned the first American edition of Croxall’s translation (Philadelphia, 1777).[3]

Courtenay, Stiegel, or Powel may have owned a copy of Barlow’s Aesop, but there were other sources for the same Barlow design. Elisha Kirkall based many of his illustrations for Croxall’s Aesop’s Fables on those in Barlow’s book, including “The Dog and the Shadow” (fig. 6). Barlow, who returned to animal painting after the second edition of the fables, lent or sold his plates for an Amsterdam edition of Aesop, printed in French in 1704. The previous year, London bookseller R. Newcomb sold Barlow’s illustrations bound in various groups. There were, thus, a number of volumes of fables in which Hercules Courtenay or one of his patrons could have found the Barlow etching.[4]

Born in Ireland, Courtenay may have known that “The Dog and the Meat” was depicted on the mantel in the small dining room at Russborough (built 1741–1750) outside of Dublin. That design followed Barlow’s print exactly. Alternatively, he may have become acquainted with Barlow’s Aesop during his apprenticeship with London carver Thomas Johnson, whose One Hundred and Fifty New Designs (1758, 1761) included references to Aesop’s fables. This design book and Johnson’s New Book of Ornaments (London, 1762) influenced Philadelphia furniture and architectural carving from the mid-1760s to the Revolution.[5]

Another English design book available to Philadelphia carvers was Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754). Plate 22 in the third edition (1762) includes designs for “French” chairs, one with upholstery taken from Barlow’s illustrations for “The Nightingale and the Hawk” and “The Dog and the Meat” (fig. 7). In other plates, Chippendale featured chimney tablets representing “The Bear and the Bee Hive” and “The Leopard and the Fox” from Barlow’s Aesop and a firescreen with needlework depicting “The Peacock’s Complaint.” Like other rococo designers, Chippendale appreciated Barlow’s spritely, well-rendered animals. Courtenay was undoubtedly familiar with the Director. The Library Company of Philadelphia owned a copy of the third edition, and the estate inventory of Philadelphia cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck listed “Shippendale’s [sic] designs.”[6]

A more unusual source for Barlow’s illustrations in Philadelphia was a deck of playing cards, published in London in 1759 (fig. 8). “The Dog and Piece of Flesh” appears on the Jack of Diamonds with the moral: “So Fancy’d Crowns led the young Warriour on/Till Loosing all, He Found himself undone.” Several of the engravings on the cards are signed “I. Kirk” and bear the date 1759.[7]

Barlow’s original etching of “The Dog and the Meat” was, therefore, available to Philadelphia artisans in 1666 and 1687 editions of his fables, in loose plates bound in 1703, and in the Amsterdam French edition of 1704. Variations of this illustration could also be found in the early editions of Croxall’s Aesop’s Fables, in the 1759 deck of cards, and in Chippendale’s Director. It is difficult, however, to determine which of these sources inspired Courtenay and whether it was the carver, the Library Company, Samuel Powel, or William Henry Stiegel who supplied the design.

Aesop’s fables also appear on contemporary Philadelphia furniture. The Howe family high chest and matching dressing table (at the Philadelphia Museum of Art), for example, have carved drawer appliqués representing “The Fox and the Grapes.” The overall design was borrowed from an earlier illustration, but the fox was taken directly from Thomas Johnson’s design for a mirror on plate 21 of One Hundred and Fifty New Designs. Barlow’s illustrations, however, were not the source of any of the other animals depicted on Philadelphia case furniture, which include the phoenix on a ca. 1768 high chest base (in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State), the swan on its accompanying dressing table (at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and the lamb and ewe on a contemporary chest-on-chest (at the Winterthur Museum). The geese on the lower drawer appliqués of the “Pompadour” high chest and dressing table (at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) are based on the design for a chimneypiece tablet on plate 5 in Johnson’s New Book of Ornaments.[8]

Several Pennsylvania and New Jersey iron foundries produced castings based on Aesop’s fables. Two side plates for six-plate stoves cast at Batsto Furnace in Burlington, New Jersey, depict “The Fox and the Stork.” A German variant of “The Tortoise and the Eagle” fable appears on a sideplate cast at Centre Furnace, Centre County, Pennsylvania. Aside from the aforementioned stove plate depicting “The Dog and Meat,” only one other casting based on a Barlow image is known. A sideplate marked “17 batsto 70” was taken directly from his illustration for the “Ringdove and the Fowler,” including the anachronistic, seventeenth-century costume of the hunter.[9]

The fables illustrated by Barlow and other artists provided a wealth of imagery for designers like Johnson and Chippendale and tradesmen like Courtenay. Whether depicted in prints or in three-dimensional form, these images also served as reminders of human virtue and frailty. For Powel and Stiegel, Courtenay’s carved representations of “The Dog and the Meat” presented a daily warning of the sin of avarice.

For more on Courtenay, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, III,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1044–64. The Stiegel stove is illustrated and discussed in Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), p. 227, no. 163.

Edward Hodnett, Francis Barlow, First Master of English Book Illustration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), pp. 220–22. The book was initially printed in 1666.

Listed with donor’s names in the card catalogue of the Library Company, Philadelphia.

The influence of Barlow’s illustrations continued well after 1770, and they can be found in use by John Stockdale in London in 1793 and, more significantly, were the basis of the famous wood engravings of Thomas Bewick, published in 1784 and 1818. An edition of La Fontaine, printed in Paris in 1799, had plates by Augustin Legrand based on Barlow, and another collection of fables with cuts after Barlow was printed in French by Ramoissenet about 1790. A Berlin edition, Hundert Fabeln, was published in 1830 with color added to the illustrations.

Georgian Society Records, Dublin, 1913, pl. 64. The left frieze panel on the ca. 1770 chimneypiece from the Stamper-Blackwell Parlor (in the Winterthur Museum) features a stag being pursued by hounds. A similar scene appears in the background of Aesop’s “Stag and Reflection.”

Morrison H. Heckscher, “English Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation 1994), p. 188.

Catherine Hargrave, A History of Playing Cards (New York: Dover, 1966), fig. 203; H. T. Morley, Old and Curious Playing Cards (reprint; Secaucus, N. J.: Wellfleet Press, 1989), pp. 166–68. A complete set of these cards is housed in the museum of the United States Playing Card Company in Cincinnati and a second set has been noted in England.

David Stockwell, “Aesop’s Fables on Philadelphia Furniture,” Antiques 60, no. 6 (December 1951): 523. Helena Hayward, Thomas Johnson and the English Rococo (London: Alec Tiranti, 1964), fig. 15. The Howe high chest and Johnson design are illustrated in Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: by the Museum, 1976), pp. 132–33, nos. 104a–b. For the phoenix high chest base and its matching dressing table, see Alexandra W. Rollins, ed., Treasures of State: Fine and Decorative Arts in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms of the U.S. Department of State (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), pp. 150–51, fig. 66; and Edwin J. Hipkiss, Eighteenth-Century American Arts, the M. and M. Karolik Collection (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), pp. 102–3, no. 55, respectively. The lamb and ewe chest is shown in Joseph Downs, American Furniture: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (New York: Macmillan, 1952), no. 184 and Gregory Landrey, “The Conservator as Curator: Combining Scientific Analysis and Traditional Connoisseurship,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1993), pp. 147–59. For the “Pompadour” chest, see Heckscher and Bowman, American Rococo, pp. 202–3, no. 138, fig. 48.

Henry Mercer, The Bible in Iron, revised, corrected, and enlarged by Horace H. Mann (1914; 3d. ed. reprinted, Doylestown, Pa.: Bucks County Historical Society, 1961), pls. 5, 242–44, 248. Mercer referred to the “17 BATSTO 70” plate as the “Squirrel Hunt.”