Paul Gauguin (French, 1848–1903), Vessel with Women and Goats, ca. 1886–1887. Stoneware. H. 7 7/8". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection, Purchase, Acquisitions Fund; Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest; and 2011 Benefit Fund, 2013.)

George E. Ohr (American, 1857–1918), Large handled vase, 1895–1900. Earthenware with copper, gunmetal, and other glazes. H. 14". (Private collection; photo, courtesy of Eugene Hecht.)

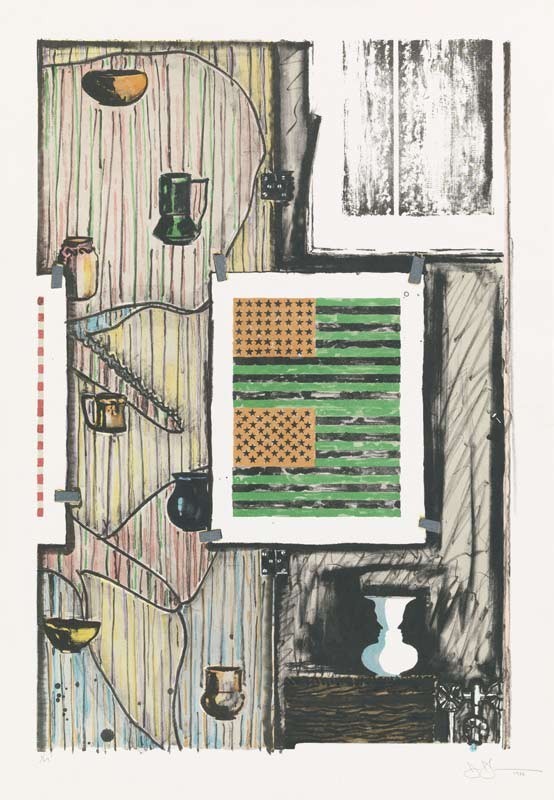

Jasper Johns (American, b. 1930), Ventriloquist, 1986. Set of eleven lithographs, two with chalk, one with pencil, one with crayon additions. (Courtesy, Museum of Modern Art; Gift of the artist; photo © 2014 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA, New York.)

Pierre Leguillon (French, b. 1969), A Vivarium for George E. Ohr, 2013. Installation of thirty ceramics from the collection of Carolyn and Gene Hecht, and one ceramic from the Carnegie Museum of Art. (Courtesy of the artist. Supported by Étant donnés: The French-American Fund for Contemporary Art; photo © Carnegie Museum of Art.)

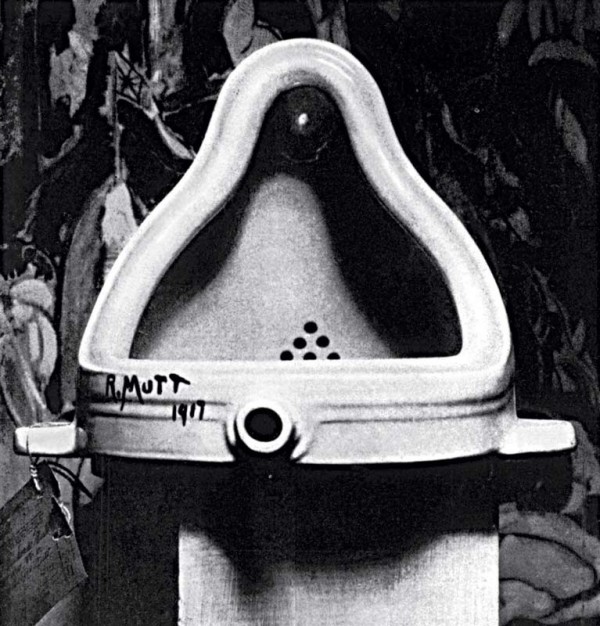

Marcel Duchamp (American, born France, 1887–1968). Fountain, 1917. Porcelain urinal, dimensions unknown, destroyed. (Photo, Alfred Stieglitz.)

Marcel Duchamp (American, born France, 1887–1968). Fountain, 1964. Glazed earthenware. H. 24". (© Tate, London. © Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris, and DACS, London, 2014.)

Kazimir Malevich (Russian, born Ukraine, 1878–1935). Suprematist Teapot, State Porcelain Factory (Russia) designed 1923, manuf. ca, 1930. H. 6 1/2". Porcelain. (Courtesy, Collection of Kamm Teapot Foundation, 2006.116; photo, Kevin O’Dwyer.)

Kazimir Malevich (Russian, born Ukraine, 1878–1935), Suprematist Teapot, as seen in the galleries of the Hermitage Museum, 2004. (Courtesy, TheState Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.)

Meret Oppenheim (Swiss, 1913–1965). Object, 1936. Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon. D. of cup 4 3/8", D. of saucer 9 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Modern Art, New York.)

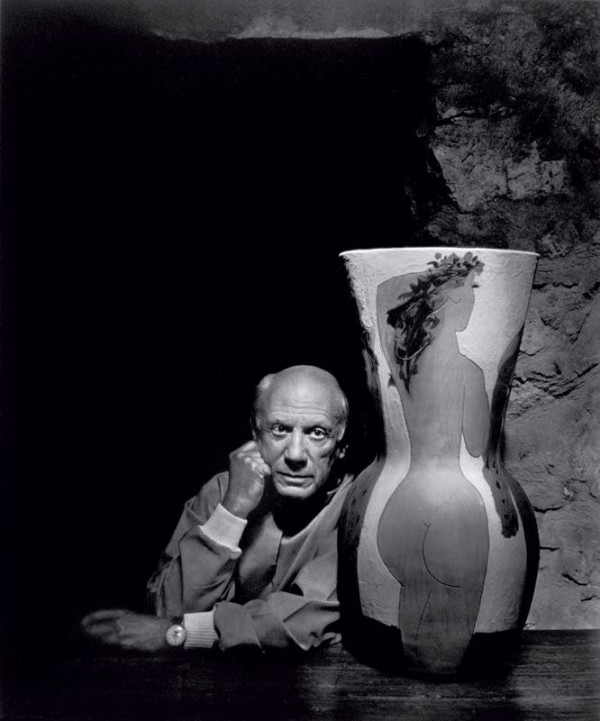

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Grand vase aux femmes voiles. Terracotta. H. 26 3/4". (Courtesy, Christie’s; photo by Yousuf Karsh [1908–2002].)

Lucio Fontana (Italian, born Argentina, 1899–1968). Impossible Bottle, 1949. Glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Frankel Foundation for the Arts.)

Lucio Fontana (Italian, born Argentina, 1899–1968), Concetto Spaziale, ca. 1957. Earthenware with slips and glaze. 9 1/2" x 7" x 7". (Courtesy, The Hockemeyer Collection.)

Peter Voulkos (American, 1924–2002). Rocking Pot, 1956. Stoneware. 13 5/8 x 21 x 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the James Renwick Alliance and various donors and museum purchase. © Peter Voulkos.)

Ken Price (American, 1935–2012). Untitled Cup (Geometric Cube Cup and Object), 1974. Painted and glazed ceramic. H. of cup 4". (Courtesy, The Menil Collection, Houston, Bequest of David Whitney, © Ken Price; photo, © Fredrik Nilsen.) Image may not be reproduced without permission from the Menil Collection.

Roy Lichtenstein (American, 1923–1997). Ceramic Sculpture #9, 1965. Glazed ceramic. H. 11". (© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein.)

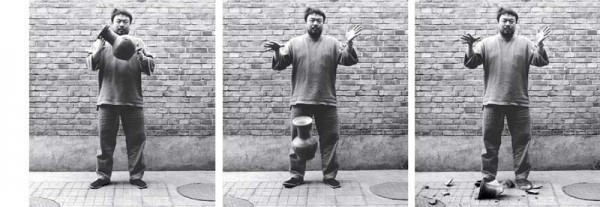

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, born 1957). Ai Weiwei Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995/2009. Three silver gelatin prints. Each 58 1/4" x 47 5/8". (Courtesy of the artist. © Ai Weiwei.)

This is an exercise in proposing canon, the eventual beatifying (and perhaps the canonization) of ten ceramic vessels as among the great icons of modern and contemporary art. It is not just a list. There are protocols to be observed. The selection cannot just be the personal favorites of this writer. Each pot, in theory, should be an artwork that could be considered by scholars as being worthy of the honor.

Canon in art is similar to the Catholic Church process for the selection of saints. The candidate must first be beatified for high spiritual achievement before being considered for the final stage, canonization. The process requires deep research, evidence of worthiness, and must receive approval from a committee of highly placed members of the church after a long period of deliberation.

Art canon is secular but otherwise parallel, a long, academically rigorous process. Unlike sainthood, which once achieved is permanent, art canon is a continuous and organic process, always in flux, with those named always at risk as the art-cardinals raise or lower the stature of a certain period’s works or artists.

Foremost in my mind was that each choice could receive a degree of consensus from the cardinals. I did not want to propose X or Y for my list if it had no chance of success. The task was made more difficult (albeit also at times easier) by adding a few of my own rules. My taste could not be the determining factor. If the evidence supported an artist I did not enjoy aesthetically (and there is at least one), he or she would nevertheless be placed on the list.

The vessel had to be ceramic but not necessarily extant, and made before the end of the nineteenth century and by the end of the twentieth. The work did not have to be made by the artist, who also did not have to be a specialist in the medium. No quota could be applied as to race, gender, or period. And, last, only dead artists need apply.

I did allow myself two works that might have been overlooked by scholars with little knowledge of ceramics (i.e., most of the culture-cardinals). Finally, I could have one wild card that breaks one of the above rules, to use at my discretion.

This process yielded seven works by seven artists, those most likely to be accepted: Paul Gauguin, Marcel Duchamp, Kazimir Malevich, Meret Oppenheim, Pablo Picasso, Lucio Fontana, and Ken Price. The two lesser-known ceramic submissions are by George E. Ohr and Peter Voulkos. My wild card is by Ai Weiwei, a living artist.

The volume of inevitable disagreement (which is why lists are made, to spark argument and debate) will depend on each reader’s bias. Players in the art world might be the most supportive. Many will be dismayed that only one woman appears on the list. Potters will be livid that Hans Coper, Lucie Rie, Kanjiro Kawai, and every other potter they ever liked, major or not, did not make the list. There also will be those who do not understand the difference between pottery and sculpture, who will demand to know why no figurative art of Robert Arneson or Viola Frey is on the list.

I had surprisingly little flexibility; listing only those that could be in the canon rather than should narrowed the field dramatically. There were never more than fifteen artists in contention from the beginning to the end.

Canon has four thresholds through which a candidate passes. One is pedigree: the artist had to be within the canon already to be considered (Ohr and Voulkos were exceptions). Saints must have produced a miracle (actually two) for canonization. That is threshold two; the artist had to have done the same, making art that was hugely influential and revelatory, a miracle of sorts in visual or conceptual terms. Timing is the third factor. The prize does not necessarily go to the first out of the gate, but the art has to be prescient and progressive within art history. The fourth threshold: its magic has to endure. It needs to touch the universal.

I added some information that might cause a shudder in academic circles. It is revealing to see what canon does to the value of a vessel, for the market plays a not-so-subtle role in the process. Each section ends with a brief statement about the value of the work being featured or a similar work.

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

The vase in figure one was a gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art from the collection of a friend. It is one of several pots by Gauguin that could have been selected for this essay. I chose this one because I have held it, intimately, several times. I know its weight and balance, and my fingers have traced the surface contours, registering its erotic, uneven skin and peered into its undulating interior. It is a canon-worthy work.

Gauguin was drawn to ceramics by two things: falling in love with a friend’s collection of pre-Columbian works; and his admiration for Ernest Chaplet, one of the first modern studio potters. Chaplet was gifted both aesthetically and technically and encouraged Gauguin to take his own path. There are some minor similarities to stoneware vessels that Chaplet was making at the time in Choisy-le-Roi, but Chaplet did ignite in Gauguin a passion for le grand feu, the art of high fire, as practiced by many of France’s leading potters at that time.

Gauguin became so involved in the medium that he even wrote two reviews for a ceramics exhibition held in Paris (published in Le Moderniste, July 4 and July 13, 1889) in which he denounced any work that was low-fired as “frivolous and flirtatious.” Only grand feu, he proclaimed, could be art.

What exactly elevates Gauguin’s pots? It is not the manner of firing but the energy they emit. They are electric and vibrate visually and spatially, even though the craft was often rudimentary. I could elaborate on this, but why one work of art has dynamism and another not is too long a discussion for this essay. However, over the course of four decades, countless artists, potters, collectors, writers, and others have shared their shock of first encounter with Gauguin’s ceramics. This is even true of many traditional potters, who usually have no love of the work made by famous visiting potters.

This appreciation is growing, as seen in the reviews of two recent New York exhibitions: “Making Pottery Art: The Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection of French Ceramics (ca. 1880–1910)” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 4–August 18, 2014; and “Gauguin: Metamorphoses” at the Museum of Modern Art, March 8–June 8, 2014. His ceramic works attracted extravagant praise at both shows.

Gauguin enjoyed an intense communion with the clay. One reads this through the wall of the pot, a membrane that records the history of the artist’s emotional touch and journey. His pots are not shaved into a classical symmetrical form with a clean silhouette, but, rather, are altered by hand from a thrown form, leaving them uneven and articulate.

Unlike other early modern painters who worked briefly in ceramics (Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Georges Rouault, and Kees van Dongen, among others), Gauguin applied his art to pots at arm’s length. But he explored pottery’s secrets through his fingers and soul as well, almost a spiritual enterprise. As a result, his pots have the piousness of faith.

The highest price paid at auction for a ceramic work by Gauguin (whose ceramic works rarely come up for sale) was $295,500 on May 9, 2002, for Vase décoré avec une baigneuse sous les arbres (Decorated Vase with a Bather under the Trees), 1886–1888, at Sotheby’s New York, lot 142.

George E. Ohr (1857–1918)

The large handled vase (fig. 2) is my first choice of pots that fine arts arbitrators might not know but should. Of all the American potters of the twentieth century, George Edgar Ohr is the most innovative and uncompromising in art terms, even though he exerted little influence in his lifetime.

Let us tackle the “influence” threshold first. I remember Robert Arneson’s response to an essay I wrote in which I claimed that Ohr was the greatest single ceramic artist in America: “He cannot be a significant artist,” Arneson said to me, “because he did not found a school for his work.” He did not mean school in physical form, of course, but that Ohr had no contemporary followers.

I first thought it sour grapes, because I had pointed out that Ohr used the same sight-gag language as Arneson had but half a century earlier. I came to understand the funk master’s point, though. Canon requires work to have an effect. Does it have to be within an artist’s lifetime? There are many examples in canon that allow for posthumous influence.

Ohr’s aesthetic was too radical for his contemporaries. In 1899 he wrote, “I am making pots for art sake, God’s sake, the future generations and—by present indications—for my own satisfaction, but when I am gone, like Bernard Palissy, my work will be prized, honored and cherished.” He later predicted, “the Nation will erect a temple to my genius.”[1] In a way it did: this year the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum, designed by Frank Gehry, finally opened in Biloxi, Mississippi.

Ohr’s appreciation was delayed because his work had vanished. He sold utilitarian wares but was loath to part with his art pots. He died in 1918 and the pots disappeared. He was all but forgotten, known only by a handful of vessels in museum collections.

In 1967 J. W. Carpenter, a New Jersey antiques dealer, was in Biloxi looking for vintage car parts. Ohr’s sons had operated an auto sales and repair shop in town and he tracked them down. Upstairs in their barn he found ten thousand pots, almost George Ohr’s entire output of art wares.

It was an astounding find. Carpenter did not think of it as a great moment in ceramic art history but told me, “they were signed, they were American, so I knew I could sell them.” Most of the pieces had never been seen outside Ohr’s pottery, so he arrived on the scene as a brand-new artist.

The collectors of Arts and Crafts material in America were cool to Ohr at first. In fact, Manhattan’s post-1967 art community was the first to embrace him. The dealers Miani Johnson, Irving Blum, Charles Cowles, and the infamous Andrew Crispo bought the work, as did artists Lois Lane and Andy Warhol, among others. Ohr’s influence on leading ceramic artists such as Betty Woodman, Ron Nagle, and Ken Price was significant. Most important was the attention paid by Jasper Johns.

Johns became obsessed with Ohr and incorporated his pots in his 1985 exhibition at Leo Castelli in New York that featured in the Ventriloquist series (fig. 3). When we had our show for Ohr at my New York gallery in 1986 (all loans, none for sale), Johns asked for our photo blowups of Ohr’s bizarre self-portraits to hang in his studio.

Artists continue to be fascinated. Pierre Leguillon created A Vivarium for George E. Ohr for the Carnegie International (October 5, 2013–March 16, 2014). This installation exhibited thirty ceramics from the collection of Carolyn and Gene Hecht and one ceramic from the Carnegie Museum of Art, along with photographs and other ephemera (fig. 4). Artists admire Ohr because they recognize and identify with his spirit of relentless risk-taking. He did performance art before it had a name. He picked up essences of Dada and Surrealism before they arrived.

For this essay I had expected to select an old friend to represent Ohr’s work, but in the end I chose a vase that was new to me. It is not one of his screamers; the handles are not as wildly fanciful as some; the glaze, while it has drama, is muted, sans the colorful neon pyrotechnics he could conjure.

Three conjoined volumes (each could be a complete pot in its own right) convey a sense of upward motion, given extra lift by the canny placement of handles. The glow of the iridescent, metallic glaze adds an element of the sacred. At fifteen inches, the size of the vase is unusual for Ohr (only a few hundred pots were taller than eight inches; fewer than two dozen were of this height). The kiln was kind; many of the larger pots tilt or slump. This stands proudly on a broad, neatly trimmed foot. Yellow glaze lights the access to the interior, and patches of this glaze break through the main form. The object lives between art and craft, between utility and sculpture, and holds its own alongside the vessel by Gauguin. Both are alive with sexuality.

The highest known price for a George E. Ohr pot was a private sale of a teapot for $250,000, in 1993. His market is underdeveloped because of an unusual circumstance: eight collectors own more than 90 percent of the artist’s major pots. Given that few important works ever come up for sale, privately or otherwise, collectors have shied away from his art, aware that building an important collection is, for the time being, impossible.

Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

In 2004 Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) (figs. 5, 6) was chosen in a poll of five hundred art experts as the most influential modern artwork of all time, with Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) second and Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych (1962) third.

My connection to Fountain is more than just professional. A friend, Beatrice Wood (1893–1998), was present in 1917 at the Armory in New York when the jury for the Independents Salon made a surprisingly moralistic judgment and tossed R. Mutt’s submission off the show. Beatrice and I have discussed the event several times, and I also was able to read her diary entries about the jury meeting.

She defended the object’s honor in the Dada magazine Blind Man shortly after the Salon: “Whether Mr Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.”

Duchamp was present—he was part of the jury, in fact—but did not reveal that he was the eponymous R. Mutt who had submitted the work, and relished every minute of the absurd debate. Fountain became an instant cause célèbre, lampooned in the newspapers and magazines of the day; that status has continued.

While others on this list are described as ten of the most major ceramic objects, Fountain is number one on any list. No validation is necessary; it is already beatified, canonized, and enshrined in art history.

Its physical life was brief, maybe six months or less. It went from being thrown off the Independents Salon to Alfred Stieglitz’s New York studio, where luckily he photographed it (with Marsden Hartley’s painting Warriors as the background) for the Blind Man magazine article. Stieglitz then threw it into a dumpster when he moved to a new studio.

Fountain’s significance is its subversive presence, still effective today. It could not be spoken about in mixed company for some time, so the attempt to show it in a public art show then was indeed scandalous. Had that been its only quality, however, it would not matter today.

The true subversion was its eroding the pillars of art theory and revising what could, or could not, be sacred to art. It had a profound effect in introducing and defining conceptual art (a mixed blessing) and provoked a debate on authorship that still resonates today.

Early on a dilemma emerged, beginning with Blind Man. Writers began to see a curious beauty—in her article Louise Norton characterized it as the “Buddha of the Bathroom”—immediately assigning a sculptural and sacred context that Duchamp adamantly insisted did not exist. Some saw it, she noted, like “the legs of ladies by Cézanne,” adding, “and have they not, those ladies, in their long, round nudity always recalled to your mind the calm curves of a decadent plumber’s porcelains?”[2]

One can appreciate Duchamp’s position. He never made it (it was an industrially made object bought from a hardware store). He did not alter it. So any formal aesthetic qualities are not his but the result of form following function and industrial manufacture. In 1961 Hans Richter wrote to Duchamp: “You threw the bottle-rack and the urinal into their faces as a challenge and now they admire them for their aesthetic beauty.”[3]

It reminds us that once an artwork becomes public, public perception outranks the artist’s intent and also that beauty can rarely be denied once art is released into the public arena. I too admire the work aesthetically but with the conscious caveat that I know that its primary role is conceptual.

Either way, it has a strong sculptural quality and sexual ambivalence, a vaginal or womb-like shape. On its back it reads like abstract sculpture, which only intensifies the aesthetic magnetism.

But is it a pot? Certainly, it is a piss pot, a very long and necessary pre-plumbing ceramic tradition, going back several thousand years. What makes this one different is that it is for male use only. And it handily defines the difference between art and craft, explained so well by scholar Doris Shadbolt in a lecture at the Ceramic Arts Foundation conference in Toronto in 1985: “Craft is what you piss in and art is what you piss on.”

Fountain no longer exists. If it did, experts estimate its value would be about $150 million. With Duchamp’s permission, Arturo Schwartz, a dealer in Milan, did issue an edition of eight replicas with five artist proofs. The highest price paid for one of these at auction is $1,762,500, for #5/8, at Sotheby’s, New York, in 1999.

Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935)

This lidded teapot created by Kazimir Malevich, a painter and the founder of Suprematism, is the first functional modern pot to be presented as a conceptual artwork (figs. 7, 8). Suprematism was an influential early manifestation of nonobjective abstraction expressed in standard geometric shapes and named for “the supremacy of pure artistic feeling” over the depiction of objects. Malevich was strongly against mixing art and utility: “Everywhere there is craft and technique, everywhere there is artistry and form....Art itself, technique, is ponderous and clumsy, and because of its awkwardness it obstructs that inner element....All craft, technique, and artistry, like anything beautiful, results in futility and vulgarity.”[4]

This thinking resulted in an exchange between Malevich and the director of the Lomonosov Porcelain Factory (the successor to the Imperial Porcelain Factory, which was nationalized in 1917 and is now the State Porcelain Factory), who wrote to the artist that his teapot “functions poorly.” “That is because it is not a teapot, only the idea of one,” was Malevich’s much-quoted but undocumented riposte.[5]

The teapot was part of a program to have revolutionary artists develop a new ceramic vision to erase the factory’s imperial past. The output was small; porcelains (generally not for sale) were toured through Russia and displayed in the windows of department stores and other venues. Not all were decorated in the Suprematist mode. Some were painted in a folk-art style with patterns, others in social realism showing factory workers, wheat being harvested, and marching solders. Still others were in the dynamic new graphic identity of Communist propaganda. The irony was that the plates were painted on blanks left over from the czarist years (this did not apply to Malevich’s teapot, because it was a new form). The front of the plate extolled the virtues of the revolution, while on the back was the cobalt-blue seal of the Imperial Porcelain Factory.

The teapot’s significance is, of course, due to its authorship and Malevich’s influence on art theory. It stirred an ongoing debate about art and function and teases us with the notion of this ubiquitous domestic ceramic pouring vessel being valid as a conceptual vehicle. It has kept its raw visual power, a brutal assemblage of geometric forms and angular planes that give a curious sense of motion-on-hold, like a collision that has been frozen in time and that might, at any moment, resume its velocity toward the compaction of its parts into a perfect square and a rectangle.

The so-called Suprematist teapot has a bizarre auction record: five have come up for sale in the last four years, some of which might have been from the first production run, but all were “bought in” and failed to sell. The nervousness in the market is due to the fact that several digitally created reproductions are now available. If a vintage teapot made within the first two years of its design were to come to the market with an unassailable provenance, its estimate would likely be $150,000–$400,000.

Meret Oppenheim (1913–1965)

Collection notes at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York record that Meret Oppenheim’s Object (fig. 9) was inspired by a conversation in 1931 between her, Pablo Picasso, and Dora Maar at a Paris café. Picasso, admiring Oppenheim’s fur-covered bracelet, remarked that one could cover anything with fur, to which she replied, “Even this cup and saucer?” then turned, beckoned to a waiter, and asked for “more fur with my tea.”

Shortly afterward, André Breton, Surrealism’s leader, invited her to participate in the first Surrealist exhibition dedicated to objects. Oppenheim purchased a teacup, saucer, and spoon at a department store and covered them with Chinese gazelle fur; in doing so, the notes state, “she transformed genteel items traditionally associated with feminine decorum into sensuous, sexually punning tableware.”

The work was given the erotic nickname Le déjeuner en fourrure (The Lunch in Fur) by Breton and was the subject of huge controversy at the exhibition, especially after the artist’s gender became widely known, and soon became the most notorious Surrealist object even across the Atlantic. In 1936 the New Yorker reported that a woman “fainted in front of the fur-bearing cup and saucer” while it was on exhibit at MoMA, and “left no name with the attendants who revived her—only a vague feeling of apprehension.”[6] The general notoriety upset Oppenheim so deeply that she fled to Switzerland and withdrew from exhibiting art for two decades.

Object covers a lot of ground—the familiar overturned, the domestic made unexpected and perverse, an innocent sensual daily ritual turned erotic and aberrant. The key component of the work is the cup, as the spoon is primarily a stirring device. The cup, however, journeys to one’s mouth again and again, smooth porcelain caressing lips as warm tea is sipped and flows over one’s tongue. That the ceramic element is not visible might bother some viewers, but were it not for the underlying presence of a real cup sitting under the fur, this work would not have had sharp Surrealist teeth.

Reactions to the cup vary. The first time I saw it I was repulsed. The second time I was deeply amused by its wit and pluck. Artist Jenny Holzer, when invited to give her opinion, found it sinister:

It seems like a cup that could fight back. I suppose fur implies teeth, and so the cup could bite you, and I also like that it’s repulsive. When you’re eating, there is nothing more disgusting than when you get hair in your mouth. I like that the fur would be a way to muffle sound. It’s like she killed off the chit chat part of the tea ceremony. I think that it basically tells you that life is not what it seems.[7]

No comparable work exists.

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

In 1947 Picasso, the most famous artist in the world, began working with not just ceramics, but specifically pottery, a non-art genre, transfixing both the art and craft worlds. He collaborated with Georges Ramie and Suzanne Ramie, proprietors of a mundane production pottery in Vallauris in the South of France. It turned out to be a long and highly productive partnership.

There was growing optimism in the ceramics community. Could this be the moment when pottery, long the stepchild, was accepted as art? The answer, alas, is no. The Picasso ceramic tide did not float all vessels. His influence was immense, however, and certainly helped to popularize studio pottery. Within two years, Picasso-styled works spread throughout Europe and remained ubiquitous for more than a decade. In Britain, Bernard Leach dubbed followers of Picasso’s ceramics the “Picassettes.” America’s Peter Voulkos was in Picasso’s thrall for two years (1954–1955) until the Abstract Expressionists tore him away. No other artist had a greater impact in the medium.

There are two different parts to Picasso’s ceramic output: unique works, which were often stunning and reveal his surprisingly scholarly knowledge of ceramics; and the editions. He did not involve himself in the latter except for the prototype, and the editions are best thought of as “souvenirs de Picasso.” The Ramie factory churned them out by the thousands.

I fully support Picasso’s place in the canon but I am not a fan. Why? Perhaps it is because he was not much into clay. He would reshape thrown forms and generally kept aloof from form, although there are occasional works where the involvement is greater. Picasso’s ceramics also fell short of the potential of his giant talent, owing in large part to the Ramie family, who offered him an unimaginative and ordinary palette. This is the Achilles heel for artists who are not ceramists. They are at the mercy of their facilitator. Where the chemistry was great and mutually creative (Gauguin with Ernest Chaplet, Joan Miró with Llorens Artigas, Lucio Fontana with Tulio D’Albisola), the results were superior.

The choice of showing Picasso’s Grand vase aux femmes voiles (fig. 10) by way of this famous portrait by photographer Yousuf Karsh (1908–2002) is deliberate. The fame of the pot, Picasso’s best-known ceramic piece and part of his widely admired series, is due in large part to Karsh, whose lens slyly captures the marriage of lowly clay with high celebrity.

Unique ceramic works are rare and sell from $600,000 to more than $1 million. A huge market exists for Picasso’s limited-edition ceramics, even though they are not rare and Picasso never touched them. Mediocre ones fetch up to $10,000 and the best as high as $75,000.

Lucio Fontana (1899–1968)

Lucio Fontana would have resented Picasso’s inclusion on this list. He and Joan Miró shared a love for each other’s ceramics and a contempt for those of Picasso. Fontana derided Picasso as a “bourgeois plate maker!!!”[8] He finally met Picasso face to face in 1950 in Vallauris and liked the man, but was still not won over by the pots. In 1952 he wrote an essay for a catalog accompanying an exhibition of Picasso’s ceramics in Milan without once complimenting the work.

Why the antipathy? Perhaps it was because Fontana was a sculptor and Picasso a painter. Their approaches were different. Fontana’s gods were form, plasticity, space, and color, and he sought them out as directly as possible, modeling clay with his hands and fingers, teasing out all the energy from this malleable material, and relishing its raw, musky, slippery eroticism. In Fontana’s mind, Picasso did not make ceramics; rather, he painted pots much like, say, the pot painters of ancient Greece, making him little different from the decorators who sat in the Ramie factory painting editions. This is an oversimplification, but it does touch on what makes Picasso’s pots for me so predictable and academic.

Fontana considered himself a far greater ceramic talent than Picasso, and he was correct. His range and output were enormous, and he resented that Picasso received such excessive publicity for working in ceramics, when he had been pushing ceramics in art decades before Picasso’s much publicized arrival. But then, he was not Picasso.

Fontana made his first ceramic sculpture in 1926. His first solo show as a sculptor in Milan, in 1931, was all ceramic, and from that year until 1968 (when he worked in porcelain for the first time, and also died) thousands of pieces were made; not a year passed without new art from the kiln.

From 1935 to 1947 ceramic was Fontana’s primary material. He made figures, animals, sea life, still lifes, sculptured vases with flowers, facades for multistory buildings, fireplaces, fountains, and sculptures of every kind (including the 1959–1960 Natura series in stoneware, considered his finest sculptural achievement, though better known in their later reincarnation in bronze). After 1947, when he returned from wartime exile in Argentina, Fontana produced many hundreds of pots, bottles, plates, lidded jars, giant amphora, bowls, and floor vessels.

Fontana is the most important modern ceramist of the twentieth century based on volume of work and his constant innovation (one step ahead of everyone in ceramics, including Peter Voulkos). The impact of ceramics on his entire oeuvre, combined with his enormous significance as a modern artist, lifts him above the flock. His ceramics touched many artists, among them Miró, Alberto Burri, Leonardo Leoncillo, Carlo Zauli, and the CoBrA group. His impact was even felt by Pietro Melandri, who used unfired ceramic materials to make paintings.

Fontana made no distinction between any of his mediums; in his mind the ceramics were equal in art. Indeed, when he was invited to take part in a significant survey of Italian art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1952, he sent his ceramics (which Nelson Rockefeller purchased), not his paintings.

By 1949 he was making actual pots and immediately began to apply the principles of his Concetto Spaziale (Spatial Concept) manifesto to these vessels. In Impossible Bottle (fig. 11), from that year, Fontana has rendered the vessel functionally impotent. The stopper cannot be pulled out and the main vessel has been cracked and reassembled and would leak like a sieve. The work is an attack on the vessel form, much like the assaults on the canvas with his Buchi series, in which holes were punched through the painting’s surface.

While Impossible Bottle is his earliest use of the pot as a complex metaphor, for his canon object I have chosen a Concetto Spaziale pot from circa 1957 (fig. 12). Fontana’s Buchi art is iconic, so this object better serves our purpose. Its cylinder-shaped form comes from a series based on the Renaissance albarello (pharmacy jar) but pared down to a reductive contemporary form.

The wall of the vessel is treated with the same stabbing as his paintings. Vertical rows of holes rise up the form, their presence given compositional importance by the painting—black and white—within each perforation. Underneath is a black slip that is dense, velvety, and light-absorbing, and the brushstrokes are present in light relief. The slip captures the brush’s passage around the pot, creating a kinetic circular swirl of energy. By denying any use for this object obliges the viewer to see it in the same light as Fontana’s paintings and ceramic sculptures, and not as decorative art.

There has been a surge of interest in Fontana’s ceramics with the works from the Buchi and Tagli series getting the most attention. In an auction at Christie’s in New York, Contemporary Art Day Auction, a plate entitled Concetto Spaziale ca. 1960–1963) with a reasonable estimate of $50,000–$70,000 sold on November 14, 2014, for an astounding $233,000.

Peter Voulkos (1924–2002)

Many in the ceramics world regard Voulkos as the greatest of all modern ceramists (though I have already assigned that title to Fontana). Some even see him as a major fine artist. On what evidence, one must ask? In truth, Voulkos has the poorest standing on this list. If this exercise dealt with pottery and not fine art, his position would be secure.

Voulkos’s stature during his lifetime was not a product of scholarly analysis, more a personality cult. He was deified without being beatified, yet alone canonizedm and he does not yet have the essential catalog of body of scholarly and critical writings. Two books about his career have been published, but neither represents a full scholarly assessment. His presence in the fine arts has declined over the years, which makes this task more daunting. Few in mainstream art who are under the age of forty know his work, and those who do make the link as the teacher of John Mason, Ron Nagle, and, above all, Ken Price. The careers of these ex-students have far eclipsed that of Voulkos and have a better chance of achieving a place in the canon than does the father of the movement that spawned them. John Mason has hit the fast track at eighty-four and is currently being fulsomely praised at the current Whitney Biennial. Ron Nagle’s tiny sculptures were included in last year’s Venice Biennale. Price’s acclaimed retrospective was given a hero’s welcome by the fine arts media in 2013, when it arrived in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, via the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Nasher in Dallas.

To make it tougher, most of his oeuvre fits better in the pottery canon, as that is where he had his greatest impact. From 1949 to 1956 Voulkos made handsome, classically formed decorative ware. From the late 1970s onward, after a failed, decade-long attempt at metal sculpture, he focused on making two forms: the plate and the stack pot, neither of which was groundbreaking.

Admission to the canon rests on acknowledging a thin sliver of time between 1956 and 1964, when Voulkos drew the pot into art (or vice versa), conflated vessels into sculpture, and made the most radical single body of vessel-themed art in the country. Is that enough?

Choosing a single pot was easy. Rocking Pot (fig. 13) is a key early work and arguably his masterpiece. Its holes do not quote Fontana, since Voulkos was not that aware of the Italian artist’s ceramics until the 1960s. Yet, when he visited Fontana in Milan in 1967, the encounter dramatically altered his future use of cuts and holes.

I have written at length about Rocking Pot in the past and know it well, but reconnecting with it for this essay has shown it to be an object grown more sculpturally convincing and aesthetically rich and complex, worthy as any vessel-themed art for induction into the canon.

The highest price paid at auction for a work by Peter Voulkos was $105,750 for Slash (1978), a stack pot sold by Cowan’s Auctions in 2010. Major works from the artist’s revolutionary period (1956–1964) rarely surface on the market, but when they do, they usually sell for about $60,000.

Ken Price (1935–2012)

Ken Price began his career by making functional pottery for nearly a decade, as many ceramists do before gravitating to another role in fine art. That period ended with his first solo exhibition in 1960, which took place at the legendary Ferus Gallery, which was founded in 1957 by Ed Kienholz and Walter Hopps and from 1959 was directed and eventually owned by Irving Blum. After this show Price announced that he was going “to make art about pottery,” which he did into the 1980s, when abstract sculpture took over.

Price’s fine art credentials are impeccable. He was a member of the Ferus Studs, a group that included Ed Ruscha, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, and Larry Bell. He also showed with major artists from New York—Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, and Andy Warhol (who had his first gallery show, in 1962, at Ferus)—not to mention at such top venues as the Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Many of the most significant art writers covered his work. In 2003 Price joined Matthew Marks Gallery, one of the most powerful galleries in New York. He died in 2012, shortly before his retrospective exhibition opened at the Los Angeles County Museum, but by then he had achieved the stature of a great American artist.

The work that represents him comes from his Architectural Cup series of 1972–1973, by which time he had moved to Taos, New Mexico, and was being influenced by the adobe houses, the rocky landscape, and the bright palette of the Hispanic community’s arts.

It may not have been his intention, but these cups, and Untitled Cup (Geometric Cube Cup and Object) (fig. 14) in particular, relate closely to Umberto Boccioni’s futurist masterpiece Sviluppo di una bottliglia nello spazaio (Development of a Bottle in Space) of 1913. Boccioni’s stated intent was to “open the figure like a window and include it in the milieu in which it lives.”[9] Both artists transformed a domestic object—one a bottle, the other a cup—into an extraordinarily dynamic work of art.

What Price brings to this is his dazzling gift as a colorist, playing the polychromatic planes of the cup with the lively syncopation of a jazz musician. What takes this work a step beyond his other cups is that a part of the sculpture escapes the confines of this drinking vessel. One is left to wonder whether it is inspired by reflection of the cup against a shiny surface, whether the handle has broken, or, more likely, if the linear projections and radiance of the cup are creating imaginary and complex spatial colonies.

The interior argument regarding this choice (and it was intense) was whether Price’s cups were more significant than Roy Lichtenstein’s ceramics. Lichtenstein’s Ceramic Sculpture #9 (fig. 15) is iconic. Both work within a Pop idiom, although Price’s is more abstract. Ultimately, Price won the round given his lifelong career in ceramics and for his more complex and exciting use of the medium. Also, his cups have had enormous influence, triggering Ron Nagle’s career and influencing Richard Slee in England, among many others. In a longer list, both would have been selected, as would Slee. The number ten is an unforgiving beast.

In the late 1990s, cups from the Architectural Series sold for as much as $225,000. The current twenty-first-century auction record was achieved in 2011 at Cowan’s Auctions, where Geometric Cup (Untitled), ca. 1973, sold for $114,562. Private sales have reached higher levels.

Ai Weiwei (b. 1957)

It was not a pot he made, nor is the pot still in existence, but Ai Weiwei’s documentation of its deliberate demise, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995/2009) (fig. 16), has drawn more attention than any ceramic object in the twenty-first century.

Ai Weiwei has taken over Picasso’s role as the most famous artist in the world. And it is official. He was voted the most influential figure in art in 2010 by ArtReview magazine, and in 2013 he was still in the top ten. It seems that hardly a month goes by without Ai hitting the headlines for one reason or another. His production of work, much of which is based in social and political activism, is prodigious.

A large part of his art is ceramic. He has shown giant porcelain sculptures such as Bubbles (2008) in Miami and Grid (2010) in Basel. Sunflower Seeds (2010), an installation of 100,000 hand-sculpted porcelain seeds at the Tate Modern, London, set the record for attendance at a solo exhibition by a living artist, with 1.2 million viewers. For his current touring exhibition, He Xie (River Crab), he produced 3,200 immaculately crafted crabs in porcelain.

Pots are an important part of his oeuvre as well. He “clobbers” prehistoric Chinese pottery (an eighteenth-century pottery term for taking extant works and altering them, usually for profit). He has broken, painted, and etched those works with Coca-Cola logos. But he also has a pottery in Jingdezhen, where he makes his own blue-and-white porcelain vases, huge bowls to hold river pearls, and other odd vessels such as habitats for owls in Northern California.

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn remains the most significant use of a pot in postmodern art. My second choice would have been Dust to Dust (2008), a personal favorite, for which Ai ground prehistoric vessels (none an important work) into dust, the cremains of Chinese culture, and placed them in lidded glass jars, which were arranged in a columbarium housing twenty of these funerary urns. Minimal and merciless, Dust to Dust is a perfect piece of conceptual art.

However, it cannot compete with the performance of dropping the urn. It took six years after the event before Ai decided to release the photographs, and this silent crash was heard across the world, causing an uproar. Ai was berated for what many saw as a selfish act, destroying “priceless” history to make his art. Ai relied on ignorance about Chinese antique ceramics to provoke his audience. Far from being “priceless,” a term the New York Times was still using a few years ago, these vases can be acquired for little money in flea markets across China. They were made in factories in gigantic quantities and millions more remain underground, waiting to be unearthed.

The act is a complex one; it deals with the Red Guard and the Cultural Revolution (whose slogan was “Destroy everything old”), with restrictions imposed by the current regime on cultural freedom, and with Ai’s constant mantra “True or fake.”

Is the urn a great work of art, an antiquity of immeasurable value, a rare piece of cultural evidence? No, that entire concept is fake, a value manufactured over centuries by the antiquities business. What is true is that it was, as Ai states, “an industrial object then and is an industrial object today.” What he did was no different or terrible than an artist, five thousand years hence, dropping a vase that was bought today at Wal-Mart.

From the outset of this writing, Ai was essential, the one living artist without whom this list could not be complete. In a short period of time Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn has become almost as famous as Duchamp’s Fountain, one of the three or four top vessels in twentieth-century art.

Urn has many similarities to Fountain. Both events, submitting the urinal for exhibition consideration and dropping the urn, were considered scandalous in their day. Both ceramic elements were lost and live only in photography. Both continue to provoke reaction. When one of the editions of Fountain was on public display, several performance artists attempted to urinate in it, with mixed, messy success (Plexiglas boxes do complicate the protest). Another recently attacked an edition with a hammer. This year a local artist smashed one of Ai Weiwei’s painted prehistoric urns on exhibition at his retrospective exhibition “Ai Weiwei: According to What” at the Pérez Art Museum Miami while standing in front of the photographic triptych, believing, ironically, that the vase he was demolishing had come from Wal-Mart.

These two works, although examined here as part of ceramic canon, are important to modern art history overall. Fountain was a withering critique of early Modernism and Urn did the same for late Postmodernism, calling the bluff on appropriation. I see them as a pair of bookends on opposite sides of the twentieth century, encapsuling avant-garde expression of that period. It is impressive that their conceptual gravitas, questioning nearly a century of art and its theory, can be compactly contained in two lowly industrial pots, a telling statement about pottery’s ability, perhaps owing to its familiarity and accessibility, to deliver potent avant-garde content.

Ai Weiwei’s market is volatile. The triptych has not been on the market for some time, and records show earlier auction prices from $80,000 to $100,000, while reports from galleries place the value at double this amount.

GARTH CLARK (b. 1947, Pretoria, South Africa), based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, is the chief editor of the nonprofit CFile Foundation, overseeing the magazine CFile Weekly (read in 125 countries) and CFile Library, a publisher of online books. He is an active (some might say compulsive) writer on ceramics and art, with more than seventy books and several hundred reviews, articles, and monographs to his credit. During his long career Clark has worn many hats. He has been both collector and dealer. He and his husband, Mark Del Vecchio, founded the Garth Clark Gallery (1981–2008; Los Angeles, New York, Kansas City, and, briefly, London), which quickly became the premier venue of international ceramics. Clark is currently a popular and peripatetic speaker, critic, and overall impresario for the ceramic arts in art, design, architecture, and technology. He was also the founding director of the Ceramic Arts Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to raising the standards of critical discourse in ceramics. The last of its eight international symposiums, “Ceramic Millennium,” was held in Amsterdam in 1990 and drew 3,500 attendees from 56 countries. He has received numerous awards, book honors, and honorary doctorates, among them being made a Fellow of the Royal College of Art, London, and the 2004 recipient of the College Art Association’s prestigious Mather Award for Distinguished Achievement in Art Journalism for his anthology Shards: Garth Clark on Ceramic Art. In 2012 the book he co-wrote with Del Vecchio, Dark Light: The Ceramics of Christine Nofchissey McHorse, won the bronze medal from the Independent Publishers Association for books on fine art.

Quoted by Garth Clark in “Clay Prophet: A Present Day Appraisal,” in Clark, Robert A. Ellison, Eugene Hecht, and John White, The Mad Potter of Biloxi: The Art and Life of George E. Ohr (New York: Abbeville Press, 1989), p. 121.

Louise Norton, “Buddha of the Bathroom,” Blind Man, no. 2 (1917): 5–6.

Hans Richter, Begegnungen von Dada bis Heute (Cologne: DuMont Schauberg, 1973), p. 155.

Quoted in Futurism, edited by Didier Ottinger, exh. cat., Centre Pompidou, Paris; Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome; Tate Modern, London, rev. and enlarged English ed. (Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou; Milan: 5 Continents, 2009), p. 65. For a further discussion about the artist’s view of utility and art, see Kazimir Malevich, “Painting and the Problem of Architecture,” Nova generatsiia 3, no. 2 (1928): 112–13.

The quote may have originated with Camilla Gray, who postulated this theory in her book The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863–1922, rev. and enlarged ed. (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1986), p. 98.

Nelson Landsdale and St. Clair McKelway, Talk of the Town, “Critical Note,” New Yorker (December 26, 1936): 7.

Conversation between Glenn Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art, and artist Jenny Holzer about Meret Oppenheim’s Object in 1988 at the Museum of Modern Art. www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=80997.

Lucio Fontana to Tullio D’Albisola, Milan, January 4, 1948. He concluded his letter with “Let Picasso kiss ass and let’s think about Boccioni!!!”

Umberto Boccioni, “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture,” Poesia (Milan, April 11, 1912), available online at www.unknown.nu/futurism/techsculpt.html.