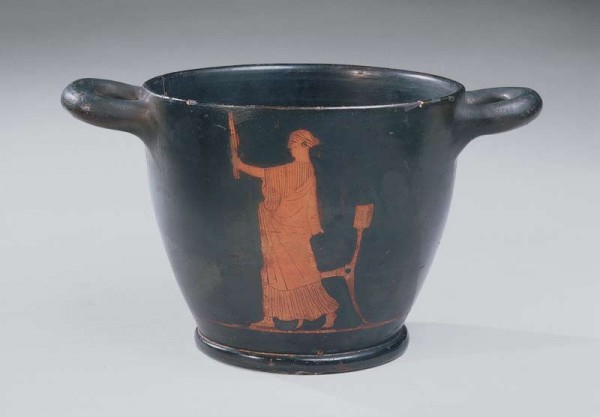

Attic red-figure skyphos, the Newark Painter, Greece, 500–450 B.C.E. Earthenware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Newark Museum; Gift of Louis Bamberger, 1928 28.204.)

Vessel for Erinlè, in the manner of the rival of Àbátàn, Nigeria, Yoruba, late 19th–early 20th century. Terracotta and metal. H. 15 7/8", D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Purchase 1987, Thomas L. Raymond Bequest Fund 87.130a,b.)

Side view of the vessel illustrated in fig. 2.

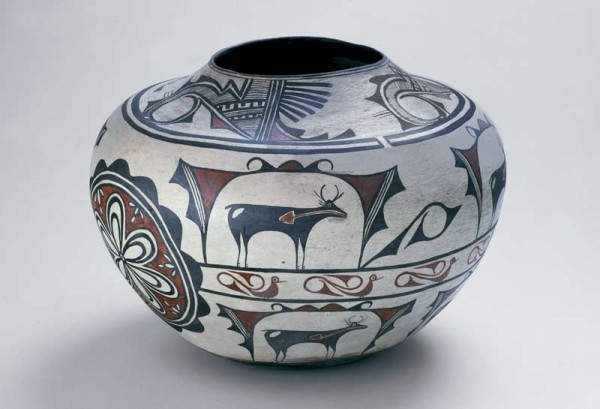

Storage jar, unidentified Zuni artist, New Mexico, late 19th century. Earthenware. H. 16 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Gift of Amelia Elizabeth White, 1937 37.190.)

Archaistic ding censer with taotie, lotus, and cloud motifs, China, Qianlong mark and period (1736–1795) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Porcelain, gold, silver, wood, and amber. H. without lid 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Gift of Herman and Paul Jaehne, 41.1988A,B.)

Detail showing reign mark on the ding illustrated in fig. 5.

Monumental urn with ormolu mounts (one of a pair), Imperial Porcelain Manufactory, Sèvres, 1804–1809. Porcelain, enamel, bronze. H. 37 1/2", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Gift of Mrs. William J. Clark, 1933 33.410b.)

“Grecian Vase” for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, decorated by Lucien Boullemier for Trenton Potteries Company, Trenton, New Jersey, 1904. Porcelain, enamel, and gold paste. H. 55 1/2". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Gift of Crane, Incorporated, 1969 69.133a–c.)

Reverse of the vase illustrated in fig. 8.

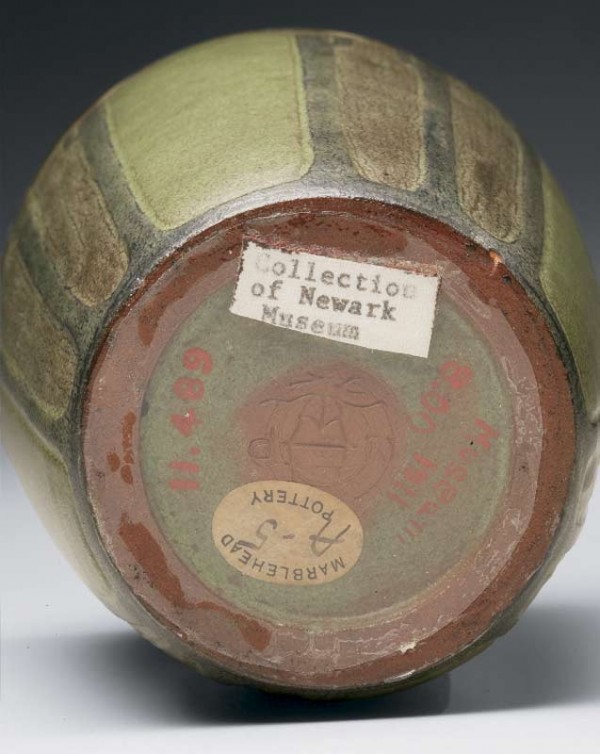

Vase with stylized floral design, decorated by Sarah Tutt and thrown by John Swallow for Marblehead Pottery, Marblehead, Massachusetts, ca. 1910. Earthenware with slip decoration. H. 7". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Purchase 1911 11.489.)

Detail of the bottom of the vase illustrated in fig. 10, showing the mark, label, and original price in red paint.

“Black Iris” vase, decorated by Carl Schmidt for Rookwood Pottery, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1909. Earthenware with underglaze slip decoration. H. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Purchase 1914 14.446.)

Folded bowl, Gertrud and Otto Natzler, Los Angeles, California, 1944. Stoneware. W. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Purchase 1949 49.374.)

Gold chalice, Beatrice Wood, Ojai, California, 1985. Earthenware. H. 12 15/16". (Courtesy, Newark Museum, Purchase 1986, Louis Bamberger Bequest Fund 86.4.)

The premise for my “curatorial ten” was the scenario in which I was told that I could keep only ten ceramic objects overall and that everything else must go. Not quite the “what would you rescue from a burning building” scenario that inhabits curatorial nightmares, but a daunting task. How to encompass a collection that covers world history in ten objects? How dare I?

I started as curator of decorative arts at the Newark Museum in 1980, when I was twenty-four. It was a leap of faith on the part of the museum’s director, as I’d just turned in my master’s thesis (on a nineteenth-century lighting manufacturer in New York City) and had a very slender résumé. Most of my paid museum experience was dusting platforms at the Yale University Art Gallery as an undergraduate. But the Winterthur Museum’s august graduate program in material culture had trained me to look at objects and to analyze them visually and technically as well as culturally. It was a skill that I would discover could be applied to any object of any period from any locale. I was no specialist, and not remotely interested in being one. The position in Newark offered me a dizzying opportunity for never-ending learning. I like to think that the reason I have remained so happily at one institution for my entire career is that I have never been bored.

After more than three decades as a curator, I have come to believe that a museum housing only masterpieces cannot fully tell the story of human creativity in any medium. The concept of “museum quality” raises my hackles. It is a term pretending to guarantee worthiness and quality. Don’t misunderstand me. Connoisseurship is a skill that every curator should have. However, it is not always the “best” object that tells the most important story; it is not only masterworks that deserve to be preserved and interpreted for the public. The art museum world in America has always been driven far too much by the changing tastes of the rich and by aesthetic trends of the moment. Taste is an insidious word that has done as much harm as good in the profession of understanding the material world of humankind. Without cultural context, a masterpiece is just an expensive thing, intended to impress the viewer and aggrandize the owner.

The Newark Museum’s founding director, John Cotton Dana, believed that the concept of “art” had been hijacked by the rich, and he spent his entire museum-director career trying to make the point that it is in everyday objects, things that touched ordinary people’s lives, that the soul of art truly resides. I cannot imagine what his founding trustees, rich and socially prominent men all, thought of this. The surprise is that many of the so-called ordinary objects purchased by Mr. Dana during his twenty-year tenure as museum director (1909–1929) are now considered masterpieces of their kind.

Mr. Dana loved ceramics. Ceramic objects are the largest single subset of Newark’s vast holdings of some 130,000 artworks and artifacts, which span human cultural history from Neolithic China to contemporary Africa. My department is assigned European and American household goods and is numerically the largest collection among the museum’s six core divisions (American Art, Arts of Africa, Arts of Asia, Arts of the Americas, Art of the Ancient Mediterranean, and Decorative Arts). In my care I probably have something on the order of nine thousand pieces of pottery and porcelain—but there are ceramics in all of the other departments, including collections of Native American, African, and Asian ceramics. As chief curator, a position I took on in 2012, I oversee all of it. Obviously, I happily defer to the expertise and scholarship of my colleagues, but I love all the pots with surprising impartiality. The history of human culture writ in clay is, to me, a breathtaking panorama of art and technology, of form and function.

I confess that in choosing my Curatorial Ten I have leaned toward my own department overall, but I could not disregard my colleagues’ favorite things. Accordingly, while I selected objects from the ancient world and Native America, I asked Dr. Katherine Paul and Dr. Christa Clarke for their choices from Asia and Africa respectively. I have incorporated their thoughts into my assessment of each choice.

In the end, these ten objects represent a core of ceramics history that embodies the cultural breadth and diversity of my museum, and perhaps highlights a part of Newark’s legacy that sets it apart from any other museum in the country.

Attic Red-Figure Skyphos

I have always loved Greek pottery, because to me it is the beginning of art pottery. It reminds me that my passion for pots has very deep historical roots. Skyphos is a fairly broad term indicating a two-handled drinking vessel for wine (fig. 1). They were made in silver and glass and pottery, and most likely were shared at banquets and symposia. It is thrilling to think that five hundred years before Christ there were people chugging down wine from a vessel they could also contemplate and enjoy for its form, craftsmanship, and narrative decoration.

My personal affection for this piece grows from its depiction of a Greek klismos, a chair form that found its way into the design vocabulary of Europe and America in the late eighteenth century. While the narrative intention of the decoration on this piece is unclear, the chair is unmistakable. I can also guess that Mr. Bamberger, a devoted and generous benefactor of the Newark Museum until his death in 1944, would have been drawn to the depiction of the chair, which today seems very familiar. In the late eighteenth century, the appearance of the klismos form on ancient Greek pots would have been a revelation to budding English connoisseurs such as the notorious Sir William Hamilton (1731–1803), the stylish Thomas Hope (1769–1831), and the scholarly Sir John Soane (1753–1837). By the time Mr. Bamberger purchased Newark’s skyphos in 1928, however, the klismos form was associated with American neoclassical-style chairs, particularly those of Duncan Phyfe, a New York cabinetmaker from the early nineteenth century. Hence the klismos was firmly linked with good taste and cultural high tone.

This is not the best piece of Greek pottery out there, and not even the best in Newark’s collection, but it has a quirky story attached to it that makes it important to us. Purchased in 1928 by one of the museum’s founding trustees, this vessel has been used ever since to attribute the work of its painter, an anonymous Greek known today as the “Newark Painter.” Of all the ancient pots in our holdings, this is the one most identified with us as an institution.

Vessel for Erinlè

I have to disregard this great pot’s affinity with modern Western sculptural ceramic vessels and not let that skew my understanding of its cultural meanings (figs. 2, 3). This is a vessel created for the worship of Erinlè, a Yoruba god linked to rivers, hunting, and healing. My colleague Dr. Christa Clarke selected this piece for me. It is a pot made by a woman, for the use of a woman as a devotee of Erinlè. The unidentified female artist who made this piece is known simply as the “rival of Àbátàn,” referring to the master Yoruba potter Àbátàn Odéfunké (ca. 1885–1967).

African art (which is, of course, many different arts because Africa is many countries and many cultures) is complex and layered in its meanings. I am very hesitant to approach such pots, because I am all too aware of my ignorance. Few Western artists and designers inspired by African artifacts ever make a real effort to understand them; rather, they work from purely formal aspects, inspired but ignorant. One can appreciate the spare abstraction of the figure on a piece like this but not recognize that the serrated arches forming her body evoke the shape of a Yoruba crown. The very color of the piece is not a choice based on availability of pigment or personal taste but on the association between indigo and the royalty of Erinlè. Intended to hold stones, sand, and water from a river sacred to Erinlè, this work of art was in fact a magical womb, protecting life and giving power to the devotee who used it.

I can, however, allow myself to like this piece simply because it is sculpturally powerful and wonderfully crafted. It has presence far beyond its size. Even without understanding its cultural implications, it is clear that, functional or not, this is a work of art. The very idea that a functional object can be a work of art was radical when the Newark Museum was founded, and this idea was at the core of our educational philosophy when most museums had no educational philosophy at all.

Zuni Storage Jar

I admit it. I love this pot because it’s so big (fig. 4). You don’t have to understand Zuni culture to appreciate the strong graphics and high-contrast color scheme. It is a beautiful early example of Zuni work, featuring the iconic heartline deer motif that immediately identifies a Zuni vessel. It is completely understandable that white Americans, particularly easterners and midwesterners, were attracted to pots like this in the early twentieth century. Just as the Western world had been drawn to Japanese art and design in the nineteenth century, Zuni ceramics offered something that was simultaneously entirely new and very old. It was the interest of these white interlopers that encouraged Pueblo women to begin to think of themselves as artists by the 1920s, and to think of the Anglos from Chicago and Boston and New York as potential customers. The growing fascination with Native American weaving, pottery, and jewelry was just another aspect of the arts and crafts movement in America, something that readily gives context to both the donor’s and the Newark Museum’s interest in Pueblo pottery.

We will never know the name of the Zuni woman who coiled this massive storage jar, who applied the fine white slip, painted on the designs, and then burnished it to a silky finish after firing it. We do know that she, like the unknown woman who made the Erinlè vessel in Nigeria at about the same time, was a master of her art.

The donor is as interesting to me as the pot itself. Amelia Elizabeth White (1878–1972) was a New Yorker and a Bryn Mawr graduate who, with her sister Martha, fell in love with Santa Fe in 1923 and decided to settle there. On the one hand, White embodies all of the white folks who fell for the exotic charms of the Southwest in this period. On the other hand, she stands apart from them because she became an expert in and collector of Pueblo objects and was an important advocate for native culture in New Mexico.[1] The Newark Museum has quite a few things donated by Miss White in 1937, the year her sister died. I like to think that she zeroed in on this museum because she knew of its progressive approach to ceramics as art.

Archaistic Ding Censer with Taotie, Lotus, and Cloud Motifs

Herman and Paul Jaehne were two of the Newark Museum’s most important and intriguing benefactors. Bachelor brothers of Dutch Jewish ancestry, they lived in Lockwood de Forest’s amazing town house on Tenth Street in New York. From the 1930s until 1941 they donated thousands of Asian artifacts to the Newark Museum. My department received some unique Chinese export porcelains as well as some other treasures from this collecting duo. I wanted to include something given by the Jaehne brothers and had already picked out my favorite piece of Chinese pottery in the museum’s collection when I asked Dr. Katherine Paul what her choice would be. I readily abandoned my own favorite because I was captivated by this tour de force of illusionistic porcelain after she explained its quality and rarity to me (fig. 5).

Made with the mark of the Qianlong emperor in the eighteenth century (fig. 6), this three-legged ding is an incredibly expert imitation in porcelain of an ancient bronze vessel inlaid with gold. A ding is a form of censer, and the maker intended to recall excavated bronzes from the Shang (1600–1050 B.C.) and Zhou (1046–256 B.C.) periods that were so valued by Confucius (551–479 B.C.) and later generations of Chinese connoisseurs. The Qianlong emperor is famous for having been an innovator and a connoisseur, but, like all upper-class Chinese at the time, he was deeply interested in China’s ancient history.

The ability of the imperial kilns to mimic an old bronze surface with glazes is startling. The streaks of green and red suggest oxidized bronze that has been buried in the earth for centuries. The applied gold patterns on the surface reveal taotie motifs that appear commonly as a cast motif on such ancient bronzes. However, the eighteenth-century origin of the vessel is given away by the lotus-petal motif around the neck, a design popularized in much later periods. The ornate lid with its carved amber dragon finial reflects the kind of ornamental enhancement typical of the later Qing dynasty—the sort of exuberant detail that Westerners associate with the term Victorian—but the carved wood is inlaid with silver inspired by archaic designs.

The novelty and technical virtuosity of this piece, as well as the reverence it shows for the distant past, embody the Qianlong emperor’s celebration of the highly refined skills of his contemporary ceramic artists and display his knowledge of history.

Monumental Urn with Ormolu Mounts

Only once in thirty-three years have I managed to display this vessel (fig. 7), in an exhibition I called “The Painted Pot.” Most of the time it and its mate sit on custom-made dollies in my ceramics storeroom and are shoved unceremoniously aside when I need to get into a cabinet. But I treasure these obscenely luxurious vases because of the obvious quality of the enameling and gilding and the gorgeous fire-gilt bronze mounts. Even as a young curator, I knew these pieces were better than the “Victorian” label put on them in 1933, when they were donated by the daughter-in-law of a great Newark thread manufacturer. It took an expert from Christie’s and subsequent visits from French porcelain scholars to confirm that this urn and its mate were made at Sèvres in the early nineteenth century. I’ve also been told that the ormolu was made by Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751–1843), the unmatched Parisian bronzier.

Although I collect European decorative arts, there is not a great deal in the way of what Garth Clark would refer to as “palace wares” in the Newark Museum’s collection. John Cotton Dana, back in the early 1900s, would have eschewed our purchasing elite European porcelains because that’s what other museums did. He also seems to have had a thing against the French, evidenced by the fact that most of the modern European ceramics purchased before his death in 1929 were German or English. Although the museum had acquired some early French porcelain in the 1910s (all tableware from local families), Mr. Dana was most interested in art ceramics of recent date.

The museum’s vase and its mate are probably not an original pair but make up part of a known group of eight closely related large ormolu-mounted vases produced at Sèvres at the same time. Our two are different shades of deep rose—the other one slightly paler than the one shown, although the decoration is consistent. The lighter pair and the darker pair, it seems, were made for French clients.[2] The more famous group, a set of four vases on bronze-mounted marble bases, was purchased by the Duke of Hamilton for his vast country house Hamilton Palace, built in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, in 1695. The Hamilton Palace sale of 1882 was a watershed in the Gilded Age, and representatives of American industrialists from Frick to Vanderbilt clustered like vultures in the auction hall. The Clark family of Newark claimed that their vases were from that sale. It’s a wonderful story.

Except that it’s not true.

Newark’s pair of vases is the only pair from this group of eight now remaining in the United States. Although it rather crushed me to learn that ours were not from Hamilton Palace, I have rather grown fond of the idea that some antique dealer sold the Clarks these vases with a spurious Hamilton Palace provenance because that’s exactly what rich Americans wanted to hear. The fact that these amazing masterworks of French porcelain ended up in a thread baron’s drawing room in Newark just pleases me no end.

“Grecian Vase” for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

This object (figs. 8, 9) makes clear why I love the Sèvres vase included above. Unlike the elite French vases, the so-called Grecian Vase from the Trenton Potteries Company has been on view for many years in the Newark Museum, in its own Michael Graves–designed niche in my decorative arts galleries. I put it there because I know it annoys so many people. It irritates the art pottery world (and I have published it as art pottery), and it frightens the high-art world, because it embodies the most egregious “Louis purée” style of the turn of the twentieth century in America—a style all people with “good taste” try to forget their rich ancestors loved. But this astonishing piece of ceramic art and technology also reminds us that Trenton, New Jersey, was once a porcelain manufacturing capital on a par with any city in Europe. The fact that the Trenton Potteries Company mostly made sinks, bathtubs, and toilets is beside the point.

There were four of these large vases made for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis. None of them, I hasten to add, was displayed in the art building. The Newark Museum’s vase, along with two others, the “Rose Vase” and the “Woodland Vase,” were shown in the industrial building in the Trenton Potteries Company display. A fourth vase, called the “Trenton Vase,” depicts Emanuel Leutze’s bombastic Washington Crossing the Delaware and was shown in the New Jersey pavilion at the fair.[3]

“Grecian Vase” is a technical tour de force of porcelain production, something that would have been possible only in the context of sanitary-fixture manufacturing. For all the fuzzy classicism of the enameling, the vase itself was touted in its day as being “pure Louis XVI.” The complex gold-paste work that shimmers across its surfaces is a glib combination of rococo and retardataire Japonism. Aesthetically it speaks to the era in which it was made. The painter chosen to paint the enamel vignettes was Lucien Boullemier (1877–1949), son of a well-known decorator at Minton named Antonin Boullemier. Frankly, I’ve always thought that Lucien’s ladies looked distinctively potato-faced. He did not, in fact, remain in America very long, but his career as a ceramic decorator is immortalized in America through his work in Trenton, and especially in this single work.[4]

The vase represents ambition, the desire of American manufacturers to achieve the prestige and profitability of their European counterparts. It was always something of a losing battle in the Gilded Age, but one has to admire Trenton Potteries’ chutzpah in creating this miracle of gold-paste work, pictorial enameling, and large-scale porcelain casting. It is an eclectic salad of styles and symbols, quite masterfully combined to produce the desired effect: a gasp. Whether the gasp is one of joy or horror is irrelevant.

Vase with Stylized Floral Design

The Newark Museum is known for its art pottery collection, something I first dealt with for its seventy-fifth anniversary in 1984, when I was still in my twenties. This exhibition was really the catalyst for my love of ceramics and the expansion of my curatorial interests to include the twentieth century.

My museum was founded with the mission of collecting and exhibiting “the art of today.” This mandate only grudgingly included painting and sculpture, because the founding director, John Cotton Dana, was a well-known and radical museologist who felt that old European painting and sculpture had hijacked America’s museums. The establishment of the decorative arts collection started with an exhibition mounted in the museum gallery in the Newark Free Public Library, of which Mr. Dana was also director. For the exhibition “Modern American Pottery,” twelve different American potteries (including Lenox China from Trenton) lent 230 examples of contemporary ceramics, covering many of the most familiar names in collecting circles today. This little vase was among the loans sent by Arthur Baggs of the Marblehead Pottery in Massachusetts (fig. 10). The original price was eight dollars (fig. 11), and it was one of three examples purchased by the museum out of that exhibition.

I cannot be too smug about Newark’s early prescience, because after one final hurrah in 1929, when the museum presented a large exhibition of international art ceramics in collaboration with Newark’s two department stores (Hahne & Co. and L. Bamberger & Co.),[5] all of the art pottery went into storage for the next two generations, only to reemerge when it was rediscovered by Martin Eidelberg for his landmark exhibition on the arts and crafts movement in Princeton in 1972.[6] My own 1984 exhibition of our American art pottery collection was the first since the Depression.

This modest object, which has become iconic across the country, embodies all the dangers inherent in terms like museum quality and good taste. Mr. Dana purchased it to make the point that it was both art and accessible to ordinary people. Dana’s embrace of the essentially bourgeois nature of its modern design and consumer audience was a slap in the face to elite patrons at other museums who fawned over Sèvres porcelains and Urbino maiolica. Dana, in his determined, puritanical New England way, was going to force Newark’s rich and powerful to deal with art that factory workers and bank clerks could appreciate as well as afford.

The irony of ironies here is that this vase is probably worth in excess of six figures now, thanks to the rise in interest in the arts and crafts movement and the subsequent embrace of this style by rich, powerful, and competitive collectors across the country. It has, over the course of a century, been transformed into the sort of rare, precious, and unattainable artifact that Mr. Dana was protesting when he founded his museum. I confess that I love this piece because it is beautiful to look at and lovely to hold; but its history is far more interesting to me than its aesthetic appeal.

“Black Iris” Vase

Newark’s “Black Iris” vase is another of its iconic pieces of art pottery (fig. 12) and arguably among the finest examples of Rookwood’s production from the early twentieth century. For those who know Rookwood, it is instantly recognizable as Carl Schmidt’s style of decoration, with its delicate realism. This vase owes a lot to both Japanese cloisonné enamels and ceramics but also to other contemporary European art potteries, such as Royal Copenhagen and Rörstrand. It is both conservative and contemporary, which is one reason Rookwood managed to maintain such enormous popularity for so many years. To Mr. Dana, who loved Japanese design, this would have been a masterpiece, which explains his willingness to pay one hundred dollars for it in 1914. For all his populist agenda, that was far more money than most people could afford to shell out for a vase.[7]

Again, however, beyond its beauty there is an untold quirky history that accompanies this piece, one of seven Rookwood vases Newark purchased in 1914. In 1912 Mr. Dana borrowed a group of Rookwood pottery from Newark’s leading art dealer, Frederick Keer’s Sons. By 1905 Keer sold not only paintings and art supplies but also Tiffany glass, Stickley furniture, Teco Pottery, and Rookwood. Frederick Keer Jr. was a founding board member of the Newark Museum, and the museum purchased its first two paintings from Keer in 1910—at no discount.

Mr. Keer’s only contribution to the 1910 “Modern American Pottery” exhibition was a scratched (and therefore not salable) dinner plate by Lenox. To my knowledge, he never donated one object to the museum he helped establish. I have a strong suspicion that Mr. Dana refused to borrow from him without a promise of gifts in 1910, and thus our inaugural exhibition included neither Rookwood nor Teco. Only in 1912, for some reason, did the Rookwood group appear. A single photograph survives in the museum archives that shows the art pottery collection, including the Rookwood loans, on view in the museum gallery of the public library. The museum finally purchased (again, at full price) seven of the borrowed vases in 1914, each of them retaining its original Rookwood price tag. There is no written record of any discord between Mr. Dana and Mr. Keer, but I just know it was there.

Folded Bowl

From the onset of the Depression, which decimated Newark’s economy, the Newark Museum struggled to survive and to provide services to a bereft and unemployed populace. Collecting would have stopped entirely had it not been for the generosity of longtime trustees such as Felix Fuld and Arthur Egner, who, however, focused on adding to the modern art collection. With Mr. Dana’s death in the summer of 1929, the museum was headed until the late 1960s by a series of strong-minded and audience-oriented women—Beatrice Winser, Alice Kendall, and Katherine Coffey. Miss Winser had been Dana’s right hand at the public library and followed him as director there. The Misses Kendall and Coffey had been curators with Mr. Dana from the 1920s.

It was not until 1948 that the assistant to the director, Mildred Weiss Holzhauer Baker, restarted the museum’s ceramics collecting with an exhibition called “The Decorative Arts Today.” From that exhibition the museum purchased a number of wonderful pots that embodied the nascent contemporary craft movement, offspring of the arts and crafts movement. This folded bowl with its patina glaze is my personal favorite among those early purchases (fig. 13). I knew Mildred Baker, who was a trustee when I arrived and who lived to be ninety-three. She loved modern art, but she also believed that craft was art and supported some of my edgier acquisitions early in my career. I think she would have totally “gotten” the complex message that Gertrud and Otto Natzler were sending with this minimalist, sculptural bowl.

Otto and Gertrud Natzler were among the many refugees who fled from rising Nazi influence, arriving in Los Angeles in 1938, the year they married. Through their entire joint career they produced vessels, but they never voiced that their work was art. My theory is that, other than a few rare tea sets and dinner wares, they produced seemingly functional vessels that were psychologically almost impossible to use. This bowl, made in 1944 and covered with an iconic glaze they developed, exemplifies the Natzlers’ subtle rebellion against those who only showed their work as household decoration.

When I published this piece in my 2003 book Great Pots from Function to Fantasy, I likened it to sculpture of the same period by José de Rivera. Although I shy away from validating craft objects by linking them to “fine art,” I will stick to this comparison. This bowl defies usage. You can buy it, you can put it on your Noguchi coffee table in your mid-century modern house, but you cannot put potato chips in it. For all its astonishingly skilled potting and glazing, it is not really functional. Putting anything in it that would leave grease marks on the surface seems sacrilegious. This is a bowl to look at, whether on a tabletop or on a pedestal. The unwary consumer might have been gulled into buying a bowl, but they ended up with a sculpture. This kind of subtlety is all too rare in studio ceramics today, and I revere the Natzlers’ bowl for that reason.

Gold Chalice

Now, I simply cannot pick my curatorial ten without at least one nod to my own career as a collector for the Newark Museum. By the time I hit thirty, I had met the great New York gallery owners Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio. They opened my eyes to contemporary ceramics in the heady climate of the 1980s, and from there I made the decision to build the museum’s collection so as to honor our tradition of collecting modern artistic ceramics. As a Victorianist with a deep love of Gilded Age furniture and silver, it was a struggle for me to wrap my mind around what contemporary studio ceramists were up to.

I have no doubt that there was something about Beatrice Wood’s opulent luster glazes that opened some sort of window for me through which I could link the insane art porcelains of the 1890s with studio ceramics in the 1980s. The barbaric, ritualistic form of this large chalice (fig. 14) and the coarse beauty of its frankly slapdash throwing were alluring to me. I remember that I could not take my hands off it when I saw it on view in Garth and Mark’s gallery in late 1985. I remember using it to drink out of—just once—after it was delivered to the museum, to see what it felt like. The gold chalice was my first ceramic acquisition in 1986 and has proved to be one of my wisest. I had a historical reason for wanting Beatrice Wood’s work, however. In 1948 one of the museum’s trustees, Mrs. C. Suydam Cutting, had given us an amazing cubist charger created by Wood in the 1940s—one of the greatest examples of her early career as a potter.[8] It only made sense to add a contemporary piece, showing the distinctive direction her pottery had taken.

In the end, though, it was the gold luster that got me. In a 1988 exhibition of Wood’s work there was a tiny jug in gold luster that I coveted. Garth and Mark secretly arranged with my parents to have it given to me for my thirty-second birthday. I had to get up and go hold it while I was writing this.

I never got to meet Beatrice Wood, although I went to her one-hundredth birthday celebration in New York. She is now gone, but her work survived the twentieth century and I think will remain, in all its modest and eccentric brilliance, emblematic of the best of American studio ceramics of its time.

ULYSSES DIETZ I was born and raised in Syracuse, New York. After receiving a somewhat useless but empowering major in French at Yale, I got my master’s from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture through the University of Delaware. I joined the decorative arts mafia by becoming curator of decorative arts at the Newark Museum in 1980. It was really the 1885 Ballantine House, a wing of the museum, that drew me there. I had no idea that I would never leave.

While the products of New Jersey have always interested me as a scholar and a collector, I have worked very hard to make Newark a national and international museum and have built the decorative arts collection accordingly. I am proud of the work I did on the Ballantine House restoration and reinterpretation project between 1992 and 1994. My love for ceramics as art has been expressed through three books, published in 1984, 2003, and 2009. In 1997 I directed the exhibition “The Glitter & The Gold: Fashioning America’s Jewelry” and its accompanying catalog, chronicling Newark’s role as what was once the greatest jewelry manufacturing center in America. In 2009 I coauthored a tradition-breaking book on the White House called Dream House: The White House as an American Home.

For thirty-four years I have lived in Maplewood, New Jersey, with my husband, Gary Berger. Since 1996 we have been attempting to raise two children, Alex and Grace. We’re still waiting on the results.

For background information on the White sisters, see Santa Fe’s School for Advanced Research website, http://sarweb.org/?exhibit_celebrate-p:admin_hallway_art_exhibits.

A pair of seemingly identical urns were owned by Charles de Beistegui (1895–1970) and displayed in his Château de Groussay. I have seen only one photograph showing the urns and cannot tell if they share the same mismatched deep pink colors of our pair. De Beistegui would have purchased his vases in the twentieth century, but it’s easy to imagine that the group of four had been split up during the later nineteenth century and one mismatched pair went to Newark and the other to de Beistegui’s château.

The “Woodland Vase” was discovered in 2011, missing its lid, in a house sale in Beverly Hills, listed as “Sèvres type.” The “Trenton Vase” belongs to the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton, where it is rightly revered. The “Rose Vase” is still missing; a vase in the Brooklyn Museum was long thought to be it, but turned out to have been a fifth example, made for the Trenton Potteries showroom in Trenton to stand in while the others were on view in Saint Louis.

Oddly enough, he seems also to have been a celebrated professional soccer player in England, if one can believe Wikipedia; see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Boullemier.

Hahne & Co. and L. Bamberger & Co. both held large ceramics and glass exhibitions in conjunction with the museum’s. From these exhibitions the first examples of French art pottery joined the museum’s collection. Fortunately, the Wall Street crash of October 1929 did not affect our exhibition program; it was only in 1930 that the disastrous long-term implications of the Depression made themselves known.

Robert Judson Clark, ed., The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1876–1916, exh. cat. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972).

One hundred dollars at that time is equivalent to more than twenty-five hundred dollars today. While not incomprehensible, it is not the kind of money a middle-class family is likely to spend on an objet d’art.

The Cutting family was enormously important in building the Newark Museum’s legendary Tibetan collection.