Medieval jug, Canterbury, England, 13th century. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 11 1/4". (Unless otherwise noted, all photos from author’s archives.)

Medieval jug, Midlands, England, 1280–1320. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 13 7/16". (Courtesy, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.)

Chamber pot, Harlow, England, ca. 1650. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 7". Inscribed, in white slip under lead glaze: “BREAK ME NOT IN YOURE HAST FOR I TO NONE WILL GIVE DISTASTE.”

Jug, Harlow, England, ca. 1650. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7". Inscribed: “BREAK ME NOT I PRAY IN HAST FOR I TO YOU WILL GIVE DESTAST BE MERRY AND WIES” (Courtesy, Museum of London.) This jug, recovered archaeologically in Harlow, Essex, was filed down, perhaps for repurposing as a vase. It bears a version of the same verse as the chamber pot illustrated in fig. 3.

Bellarmine bottles, Woolwich, England, ca. 1660. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/4".

Bellarmine bottle, possibly Chelsea, England, ca. 1672. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 7/8". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Pew group, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/8". (Courtesy, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, C.6-1975.) The details are picked out in brown slip.

Pew group, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1750. White salt-glazed stoneware. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History.)

Chinese figure, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1750. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Weldon Collection.)

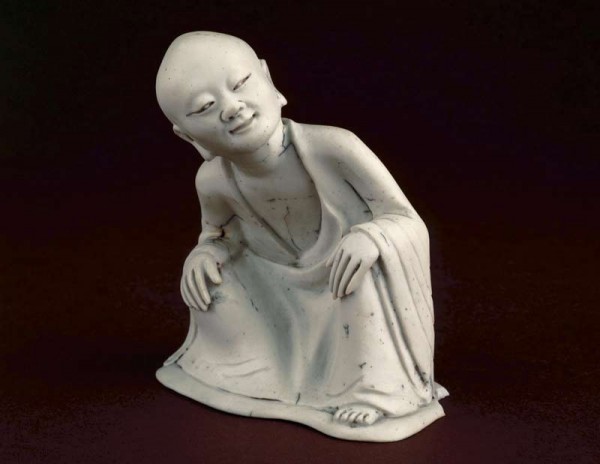

Chinese figure, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1740. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 3 1/2". (© The Trustees of the British Museum; photo © Trustees of the British Museum, PDF,A.495.)

Dish, Southwark, England, ca. 1660. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 15 1/4". (Private collection.)

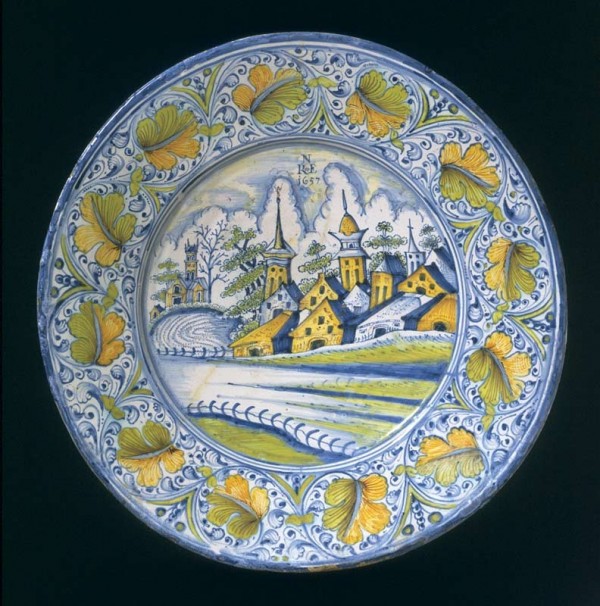

Dish, Richard Newnham, Pickleherring Pottery, Pickleherring, England, 1657. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, C.57-1971.)

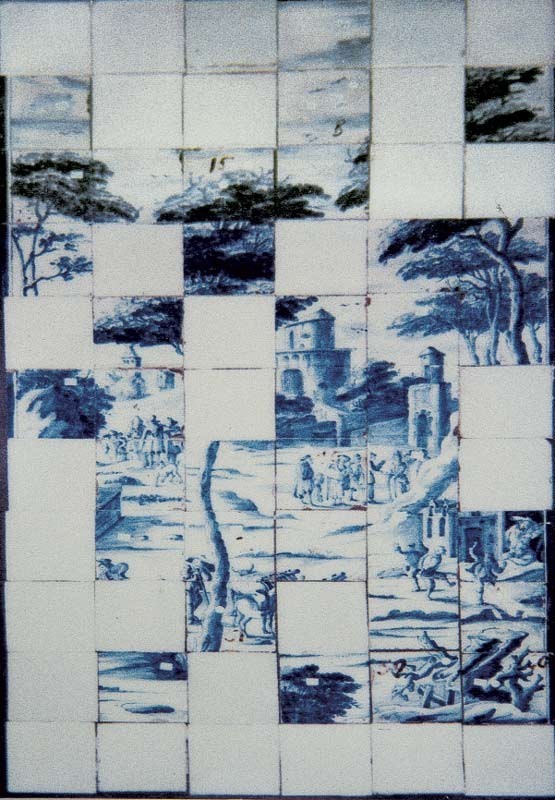

Tile panel, London, England, ca. 1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. Each tile approx. 5" square; overall panel 4' 6 1/2" x 2' 6". Approximately thirty blank tiles fill in for the missing ones.

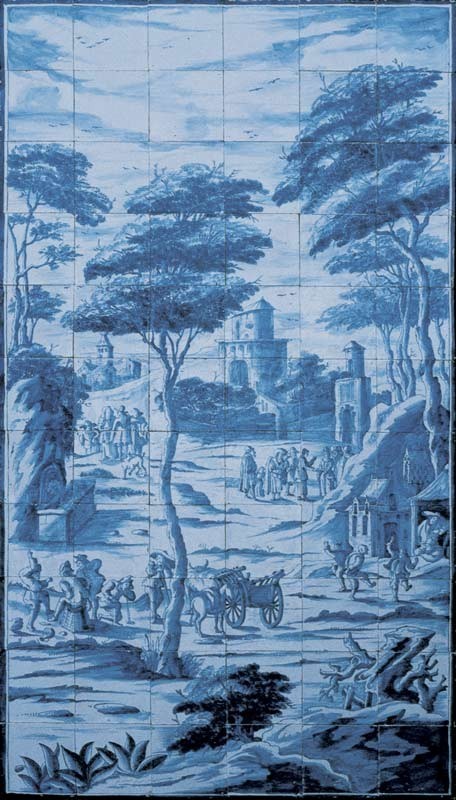

The tile panel illustrated in fig. 13, fully reassembled. (Courtesy, Allen Gallery of the Curtis Museum, Hampshire.)

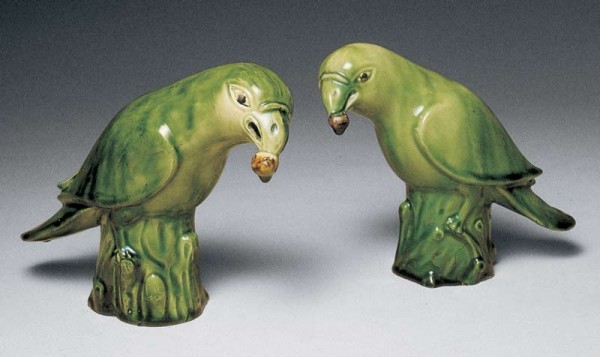

Pair of parrots, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1755. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Weldon Collection.)

Pair of parrots, Johann Joachim Kändler (1706–1775), Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, Leipzig, Germany, ca. 1745. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Given by Mrs. O. J. Finney in memory of Oswald James Finney, C.4-1984.)

Left: Gardener, Ralph Salt, England, ca. 1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 11/16". Mark, on reverse: SALT. Right: Shepherdess, England, 1979. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 5/8". Mark, on scroll on reverse: WALTON (Courtesy of The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent.)

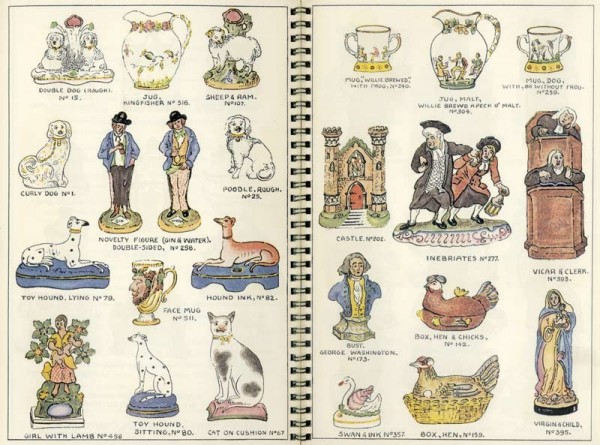

Two pages from Old Staffordshire Pottery, William Kent, Burslem, England, 1955. William Kent produced the catalog to list the “Astbury” figures he offered for sale. The figures were based on older models.

Shepherd group, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 7/16". (Courtesy of The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent.)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Several months before his death in 2010, London ceramics dealer Jonathan Horne sent me a brief paper summarizing some of the highlights of his forty-plus years in the antiques trade. Although I have adapted his submission to fit the format of this year’s journal, with some minor annotations to the objects pictured here, these are, by and large, Jonathan’s own words.

This is a précis of my forty years of trading in the antiques business and in the process shows some of the problems that faced a young dealer in the late 1960s compared with today’s hard times. To me it has been a passion and a job for life, but it has never been easy and, unfortunately, you never know the good times are here until they are over.

Even today antiques traders are regarded with suspicion in some quarters. This is something I have always been conscious of, even in the early days when I was doing archaeology. Many years passed before I was able to become a member of the English Ceramic Circle. I was one of the first dealers to be accepted by the American Ceramic Circle, so things are moving along.

Generally speaking, though, dealers do not get a good press, and this is not helped by television, which churns out programs that continually give a mischievous interpretation of the trade, highlighting the few rogue dealers whose performances are given star billing for the derision and amusement of the general public. By way of leveling the playing field, and to bring further acceptance of the trade, I helped organize a new guild in 2004, which is open to trade and academic alike. I thought it particularly important in these hard times that we are together with one voice.

It is hard to imagine the field without the dealers. The auction houses would not be able to survive, collectors and museums would be starved of goods, and the art market would die. Most of the great collections have been put together or enhanced by dealers, so we do serve our purpose. Among the dealers there is a vast untapped source of knowledge, which leads me to believe that, despite the effects of recessions and so forth, we will be around for a little bit longer.

There have always been part-timers dabbling in the trade, but professional dealing is very much a full-time occupation. The qualifications required for becoming a successful dealer have always remained the same. First, one must have a deep interest in the chosen subject, have the desire to buy the very best that one can afford, and be willing to pay the price. In addition to having all the instincts and desires of the collector, one must also be mercenary enough to be able to sell the objects.

How do you know if you have that right mix to be a successful dealer? It is really a matter of trial and error, and I, as a young man with no responsibilities, jumped in at the deep end and made the commitment to becoming a working professional. That was in 1968 and I can remember my father saying to me, “Do you realize you will have to take £8,200 out of somebody else’s pocket every week just to stay in business?” When it was put like that, it seemed a very daunting proposition, especially since at the time I was only earning £20 per week. Nevertheless, green though I was, I took the plunge, had cards printed, and became an antiques dealer virtually overnight. Within days people were asking my advice and I didn’t know anything. Important issues loomed: Where do you go to get stock? How much do you pay? Where do you find customers?

Of course it is never the right time to start a business. I was told I should have begun in 1960, that I had missed the boom, that it was now too late! The usual moan of antiques dealers is that they can’t find enough good pieces, but I do remember one dealer reacting to this old chestnut and complaining about how much worse off it was in the 1950s. “In those days,” he said, “you could buy wonderful things for very little money—but there were no customers.”

Having had a background and training in the retail world, I had somehow thought that antiques would be different, but in fact the same basic rules apply to all forms of retailing, whether you are selling fridges, ladies’ shoes, or delft plates. Stock control, stock turn, and cash flow are all familiar terms to the high street trader and these should also apply to antique dealing.

Stock control is most important. It is easy to go out and spend a lot of money, but you need to be able to sell the goods. If, say, £100,000 is spent on stock, the first 30 percent will sell easily and the next 60 percent will go in time, but no matter how good the stock is, there is always that last 10 percent, stock that is hard to shift. And if it is not disposed of, that dead stock will grow over time and eventually stagnate the business. If something is bought for £1,000, it can sometimes be better to sell it for £800 the next day than wait two years to get £1,200. Within those two years, that £800 could have been used four times, giving you four profits. Therefore, stock control helps turnover, which helps cash flow, with which you can buy the fresh stock, which is vital for that successful business.

The biggest single change in the last forty years must be the availability of goods. “I can’t get the stock” has always been the cry of dealers, but it is still out there somewhere and most will eventually come back on the market. There is a great satisfaction in being a dealer. The thrill of the chase, the excitement of finding a rarity. You are always regarded by the collector as an equal, going through the front door and never the tradesman’s entrance. It’s like being in a club, meeting the same people throughout the world, sometimes in smart locations and at other times in a muddy field. The truth is, it’s a wonderful job for life.

So where does all the stock come from? The usual sources are auction rooms, other dealers, or private individuals. But things have dramatically changed from forty years ago. At that time Sotheby’s and Christie’s had a specialist pottery sale of at least 200+ lots every six weeks, and I would often buy twenty or thirty lots at each sale. Phillip’s or Puttick and Simpson, as they were then, had a sale every week, then went to fortnightly. Under Bonham’s umbrella, specialist sales today are now down to four times a year, and, if you are lucky, half a dozen good lots might come along in each sale. When I first started there were a dozen dealers in London, all with good stocks of pottery, and some, such as Frank and Kathleen Tilley off Sloane Square, David Newbon, Tristam Jellinek, Arthur Filkin, D. M. and P. Manheim, among others, with wonderful pieces. Now these dealers are gone and have not been replaced because the stock is not there. Specialist dealers are an endangered species—in the English pottery world we are down to only one!

The salesrooms are still a significant source of goods to the market. They can be very rewarding, but they can also be a minefield to the untutored. It is a game of skill and chance, pitting your wits against others, mind reading, learning techniques of bidding. One dealer (who, alas, is no longer with us) had been known on several occasions to bid from inside a wardrobe so that others couldn’t see what she was bidding on. I would often try to sit behind a well-known dealer colleague in a salesroom because I could tell what he was interested in. As his desired lot got closer, he would break out in nervous red blotches on the back of his neck.

Of course it is always advisable to read the catalog properly. I remember about thirty-five years ago going to a country house sale in Kent. All the ceramics had been laid out on five trestle tables in the attic—something like 150 pieces, all junk except for three medieval jugs. The jugs all had the same lot numbers, so I left a bid of £300 for them. Two days later a pantechnicon van arrived at my shop, which in those days was very small, with seven tea chests full of china. I hadn’t noticed that the contents of the attic room were, in fact, one lot!

When starting a collection, buy only from the specialist dealer so you can learn and be confident that you are getting the right thing. When I first started, I found that one of the best places to get stock was from the very top dealers. Often they would buy a collection of goods which could contain some lesser pieces that they would be only too happy to knock out.

Dealers lay claim to being the second oldest trade, and the basic idea of dealing and collecting has never changed and probably never will. What we collect in the future will change and our descendants might well be craving for old electric light bulbs or plastic coat hangers, but rest assured there will always be a dealer ready to meet their requirements.

What should I collect? This is a question often asked. I always answer: “Buy what you like. Never go for what is fashionable because that means the price will be high. Always aim for quality, and never buy on price alone.” I have always maintained a policy that it is far better to buy something that is broken but interesting than something perfect and boring. All too often a collection comes to the salesroom that has obviously been bought on price alone; in the long run it doesn’t pay.

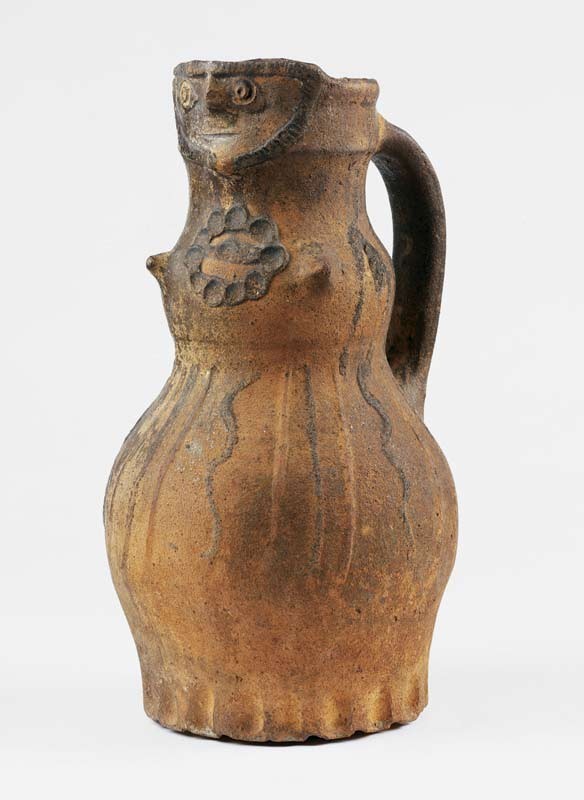

Medieval Jug

My personal interests lay in archaeology, which gave me a very limited knowledge of early pottery, but such material was decidedly not commercial. For example, this fine baluster jug with anthropomorphic features dates from the thirteenth century (fig. 1).[1] It was made near Canterbury, Kent, coming from an area called Tyler Hill, where pots have been produced for centuries. The jug has a rudimentary face decorating the front. The potter pinched the base on, leaving his finger marks in the process. Usually these jugs were fired upside down, stacked on top of each other. This often meant that the bottom of the jugs bowed out, but the pinched foot rim provided a steady support. The splashes of glaze were purely decorative, the majority of the body being deliberately left porous, which allowed the contents to remain cool through the condensation.[2]

Another example of a fine anthropomorphic jug is in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 2). Both jugs were serviceable and provided amusement during use. But my attraction to these early pieces lies in their simple functional shapes, which have never been bettered. They are very tactile, and through handling these pots you can feel the hands and fingers of the person who made them more than seven hundred years ago.

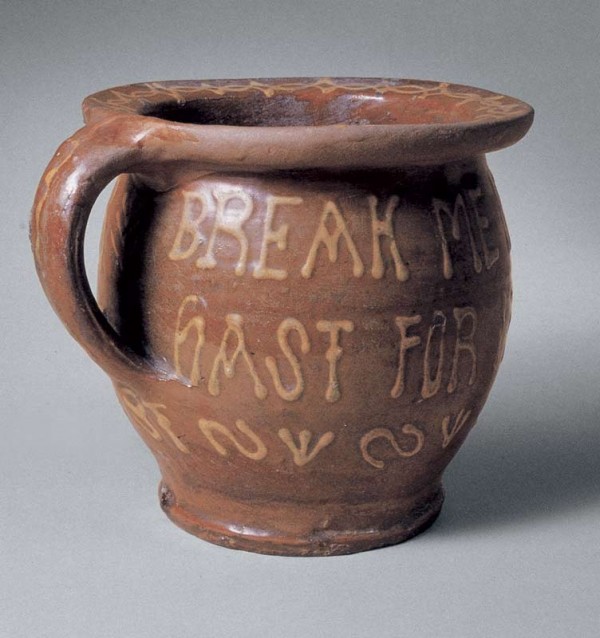

Chamber Pot

The exceptionally fine pieces of ceramics rarely come on the market, and when I first started in business I couldn’t afford them, having only about £1,500. And so, as a fledgling dealer and thinking commercially, I set off for Wales, buying what I thought would be the most obvious sellers—copper kettles, oil lamps, pots, and pans. With no knowledge, one has to rely on flair and a natural eye. Whilst knowledge is all important, the ability to spot magic is something which cannot be taught yet it marks a dealer for success.

Having returned from Wales with a car full of stuff, how do you go about selling it? The obvious places in those days were Bermondsey Market very early on Friday mornings, or Portobello Road on Saturdays, where I had a stall for eight years. I remember being disappointed at the first day’s takings, which amounted to only £28. During the week I would travel around the countryside visiting antique shops, always taking a box of goods in the hope of selling as well as buying. I soon got rid of the copper kettles and concentrated more and more on pottery. After a time I became known as a specialist, which was the secret to success, and Portobello became a ritual. I brought something fresh every week and unpacked the stock very slowly, in order to keep a crowd.

An essential piece of domestic pottery is the humble chamber pot. By the early seventeenth century, slip-trailed earthenwares were produced in areas south and east of London. Several pottery sites are known from Essex, where the slipware products are referred to as “Metropolitan slipwares,” named such because London was the primary market. These Metropolitan wares were decorated with a white slip trailed directly on a dark clay body.[3] The city of Wrotham, in Kent, was another production center for early slip-trailed wares.

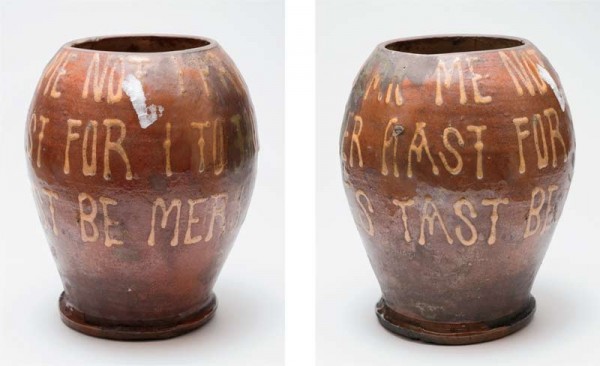

The chamber pot shown in figure 3 has a witty rhyme inscribed in yellow slip around the outside: “BREAK ME NOT IN YOURE HAST FOR I TO NONE WILL GIVE DISTASTE.”[4] Surviving examples of Metropolitan slipware in general are very scarce and most examples come from archaeological contexts. In its day the chamber pot was probably the most common item in the household, but to find an early piece like this in good condition today is extremely rare.[5] The Museum of London has several objects with similar verses, including one dated 1651. Another example in its collection bears the inscription “BE MERY AND WIS,” as well as a jug with an adulteration of the combined inscriptions: “BREAK ME NOT I PRAY IN HAST FOR I TO YOU WILL GIVE DESTAST BE MERRY AND WIES” (fig. 4).[6]

Woolwich Bellarmines

Having a background in archaeology does help when items like these stoneware jugs turn up (fig. 5).[7] Stoneware bottles of this type were very common during the seventeenth century and can be found throughout the Western world. They were used for wine and were imported into England from Germany in huge quantities. They are nicknamed bellarmines, after the infamous bearded Cardinal Bellarmine of rotund shape who was particularly active in persecuting Protestants in the Low Countries; current scholarship classifies them as Bartmann, after the German for “bearded man.” Normally the German bottles can be bought in antique shops for as little as £300 each, but the two examples shown here are not quite what they seem. The masks and medallions compare exactly with sherds excavated from a kiln site found at Woolwich and thus represent the earliest examples of stoneware made in England.[8] This makes their value some thirty times more than the German equivalent. The example shown on the right in figure 5 is now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.[9]

Other early English potters made copies of the so-called Cologne ware. John Dwight received a patent for producing “Cologne” and other ware in 1672, and excavated material from his factory included a variety of bellarmine jugs. A few 1672 dated bottles bear “WK” (and French inscription) relief medallions and are associated with William Killigrew, who, like Dwight, might have made bellarmines like this rare example in the Chipstone collection (fig. 6).[10]

Pew Group

As a specialist I found it easy to get into antiques shows, and the old Chelsea Antiques Fair, which was held twice a year, became my main source of income. It was in circa 1973 that I made my greatest coup. My contact was a picture dealer who had been getting some very good pieces out of a West Country estate in Dorset. He phoned up one day and asked if I would be interested in a pew group.

Well, of course, a pew group is the dream of all English pottery collectors, and so with my heart in my mouth, I went along to look at this object (fig. 7). Never having handled such a rare piece, I had to decide if it was a fake or not. The picture dealer had found it on the kitchen table of this great house, in several pieces, amongst a pile of domestic china waiting to be put out to the local dealer. Then came that terrible question. How much would I give for it? How do you value something like this? After deliberation and with pounding heart, I took the plunge and offered £4,500, which was a lot of money at the time. Luckily this amount was near enough to his own valuation and a deal was struck. In trepidation I took the piece and drove home in a cold sweat but soon came to realize that this small piece of broken Staffordshire pottery, made circa 1750, was worth more than the house we lived in. Pew groups are some of the earliest figures made in England, and they are highly sought, as most of the examples are in old museum collections (fig. 8) in England and America. Unlike later figures, they are almost entirely hand-modeled. Many of the details, as seen on this group, are picked out in applied brown slip. The gentlemen seated on either side of the woman are shown taking snuff. After enjoying the figure group for nine months, I sold it for £15,000, and the Victoria and Albert Museum eventually bought it for £20,000.[11] Was this a good sale for me? It seemed so at the time, but on the open market today this piece would probably fetch more than £200,000!

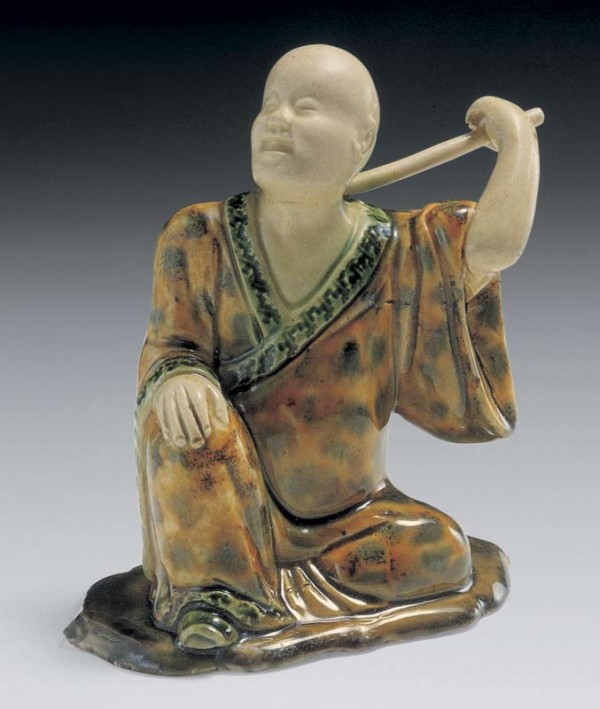

Chinese Figure

When I first exhibited at the Grosvenor House Antiques Fair in 1976, I still had a stall in the Portobello Road market. Mind you, the fair’s organizers did not know this, nor did the Grosvenor House customers. They would not have been amused to know that most of the stock came from Portobello and, vice versa, the Portobello customers would not have bought goods knowing they had come from Grosvenor House. This illustrates the psychology needed in selling antiques. Portobello Road was and still is an excellent training ground for the antiques dealer and collector. I still go down there most Saturday mornings, partially out of habit and also to catch up with the gossip; but alas my purchases these days usually consist of only a bacon sandwich and a cup of tea.

In the past the Portobello market was very rewarding. About twenty-five years ago I bought a superb Staffordshire creamware figure (fig. 9) dating from the middle of the eighteenth century that probably derives from a Meissen original.[12] The exceptional underglaze colors possibly made the dealer doubt the age of the figure. This was reinforced when he also was told by Christie’s that it was not old—but it was, and eventually sold for £28,000. It is an extremely fine example of a press-molded figure of a lohan, a Buddhist monk or disciple. Examples made in white salt-glazed stoneware are also known.[13] The Meissen original that most likely served as the model for the Staffordshire figure drew its inspiration from Chinese porcelain prototypes (fig. 10).

Strangely enough, this figure in today’s market would only fetch about £15,000–£18,000. The market is affected by many outside forces—wars, strikes, the stock market—and the appearance of fakes on the market in the late 1980s damaged collector confidence. Of course there are always at least two people who want to spend money in this particular market, which then pushes prices up.

Delft House Dish

To be a successful antiques dealer, you have to stand out from the crowd. There are a number of ways to do this: specialization in a subject, becoming a television personality, writing books, giving lectures, promoting one’s image through advertisements and publicity, antique shows, fancy carrier bags, and so forth. The goodwill of the business is vital and this can only be built on years of trust. If the dealer is going to try and sell a broken delft plate for £30,000, he or she must have the solid knowledge to back up the object, and the buyer must have absolute confidence in that dealer.

One such broken plate turned up a few years ago in the country (fig. 11).[14] It had been brought into a local sale room by a student who found it hanging on the wall of his apartment where it had been left by the previous occupier to cover up a damp patch on the wall. As the dish was broken in three, the student hoped he might get £20 for it. The auctioneer thought more highly and cataloged the piece as Spanish or English with an estimate of £8,200–£8,300. This tin-glazed or delftware dish was actually made in the Southwark area of London circa 1660. It is extremely rare and desirable, and the student was utterly amazed when the piece sold at auction for £824,000. The dish became part of the noted Longridge Collection. Further research by Leslie Grigsby has found that “documentary and excavated material indicate that most, if not all, [individuals responsible for the decoration on this and similar dishes] were employed in Southwark at the Pickleherring factory of Richard Newnham or at Rotherhithe.”[15] One such example, clearly by the same hand, is this dish (fig. 12) in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection.

Tile Panel

Probably the most remarkable purchase I ever made seems unbelievable but is quite true. In 1969 or 1970 I was invited to a house to purchase a collection that consisted of more than 250 pieces of delftware, all stacked in the attic, untouched for thirty years and filthy. The ascent to the attic was up a tiny staircase and through an even smaller door. The house was superb. A tall, elegant William and Mary farmhouse built on four floors, three of which held no ceramics for me. Thirty times I had to go up and down four flights of stairs to extract that hoard of goodies. For months I was going down to Portobello with boxes of dishes selling single examples from £8 to £12 for slightly damaged examples, while the perfect ones ranged from £25 to £45, and still the customers haggled—some things never change.

Over many years I had collected odd tiles originally from a large tile panel of sixty-six tiles (fig. 13). I had bought them from about ten different sources—Portobello, Phillips, Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and several private collections. Each tile was numbered on the back so you could tell where it belonged in the scene. I thought that to get thirty-six out of a total of sixty-six was going to be the end of the story, until one day I went to a country sale and found an old box of tiles in the corner of the sale room. I immediately knew they were part of my picture from the numbers on the back but didn’t make my interest obvious, to avoid the attention of others. The purchase was made and I cannot describe the excitement on returning to the shop to see if these tiles completed the picture. All but three were present, and this fine piece, made in London circa 1720, can now be seen in Allen Gallery of the Curtis Museum, Hampshire (fig. 14). If I had not gone to that one sale, this tile panel likely would never have been reassembled.

Pair of Staffordshire Parrots

During the mid-eighteenth century the Meissen factory was known for producing white porcelain birds and animals in imitation of the Chinese blanc-de-chine. Those designs were pirated by the Staffordshire potters, who in turn, circa 1755, produced this fine pair of green parrots (fig. 15).[16] So here you have a pair of Staffordshire parrots imitating a Meissen pair (fig. 16), which in turn were derived from a Chinese original. These Staffordshire “imitations” are now worth considerably more than their Chinese equivalent. The difference between an imitation and a fake can be a fine point, but in the world of antiques I would define a fake as something made with the intent to deceive for financial gain. Both the Meissen figures and those copied by Staffordshire potters were made to imitate a similar form in a different medium. Such imitation was not uncommon. In 1751 Sir Charles Hanbury Williams lent his collection of Meissen figures to the Chelsea porcelain factory for them to copy in a similar manner.[17]

Astbury-Type Figures

The invasion of 1745 from Scotland with Bonnie Prince Charlie gave the Staffordshire potters a new market, and many small figures were produced wearing the tartan and playing bagpipes. These charming little figures, commonly termed Astbury-type, were supposedly made in Staffordshire around this time. But in this instance the smaller figure is a fake. In the early days of Colonial Williamsburg substantial funds were available for object acquisition, and when a number of these were on the market the foundation acquired them without knowing they were fakes. Ceramics curator John Austin did a huge amount of research to uncover the true identity of the figures, and, as a result, he is one of the leading scholars on recognizing such fakes.

Problems arose from firms like William Kent of Burslem, a well-known Staffordshire pottery that made similar figures right up until 1962. These cannot be called reproductions as they have been continually produced, but there is a huge difference in value between a figure made circa 1820 and one made circa 1970 (fig. 17).[18] The company’s catalogs show eighteenth- and nineteenth-century forms that were being produced until recently (fig. 18). Although not made to deceive, as time goes by the pieces take on an aged look, and I see more turning up in sale rooms, unwittingly sold as antiques. The figure on the left was made circa 1820, whereas the one on the right was made in 1979 by another Staffordshire manufacturer. Fakers and imitators trying to make a quick buck from the unwary will always exist in the market.

Shepherd Group

I did not want to end this article with a fake, so I have included this wonderful shepherd group (fig. 19).[19] Mind you, even to the untrained eye there can be little doubt as to the authenticity of this piece. Made in Staffordshire circa 1820, this truly high note of potting is now on view in the City Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent. The craftsman has shown great imagination and used many different molds to produce this amazing piece. Included are an owl, five birds, a squirrel, a snake, eight sheep, a dog, and the shepherd—all contained within that elaborate, attenuated wall. It is a charming, witty, colorful piece, inspired by a romantic idea of the English countryside. Quality pieces like this have always fetched high prices and will continue to do so.

JONATHAN HORNE was a London antiques dealer specializing in English pottery. He was chairman of the British Antique Dealers’ Association from 2001 to 2004, vice president of the Society for Post Medieval Archaeology, president of St. John Ambulance Kingston Division, Freeman of the City of London, Liveryman of the Stationers’ Company, and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. He was also instrumental in the founding of a new City of London guild set up on behalf of all those involved in the decorative arts, serving as Master in 2008–2009.

Horne was educated at Whitgift School in Croydon, where he took an interest in history and archaeology. In 1968 he opened a stall in the Portobello Market. Four years later he was elected to the British Antique Dealers’ Association (BADA), and in 1976 he moved on to set up in a small shop at 66c Kensington Church Street, where he dealt in early metalwork, needlework, carvings, and works of art as well as early English delftware and Continental pottery. He cultivated as clients many significant American museums and collectors.

For nearly thirty years he also produced an annual exhibition catalog, which has become an important reference series for all those interested in English pottery. In addition, he published a number of important ceramic reference books that remain standards in the field.

Among his own notable exhibits was the last, Pirates of the East End (2008), which displayed artifacts excavated from the Limehouse residences of known seventeenth- and eighteenth-century privateers, bringing attention to a little-known corner of London history.

In June 2010 he was recognized as Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) and died shortly thereafter, on June 25, 2010, at the age of sixty-nine.

Jonathan Horne, A Collection of Early English Pottery, Part V (London: J. Horne, 1985), pl. 104.

R. W. Newell, “Thumbed and Sagging Bases on English Medieval Jugs,” Medieval Ceramics 18 (1994): 51–58.

Research to date indicates that the main production site for these wares was at Harlow in Essex. See E. Newton and E. Bibbings, “Seventeenth-Century Pottery Sites at Harlow, Essex,” Essex Archaeological Society Transactions n.s., 25 (1955–60): 358–77.

Jonathan Horne, A Collection of Early English Pottery, Part XI (London: J. Horne, 1991), pl. 288.

Ivor Noël Hume, “Through the Lookinge Glasse: or, the Chamber Pot as a Mirror of Its Time,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 139–71.

The jug from the Museum of London can be viewed at http://archive.museumoflondon.org.uk/ceramics/pages/object.asp?obj_id=115645. At some point, the neck of the jug was ground down to convert it into a vase.

Jonathan Horne, A Collection of Early English Pottery, Part XIII (London: J. Horne, 1993), pl. 367.

At least three wasters from the Woolwich site bear this medallion and are now in the collections of the British Museum (1987,0513.2,12,13).

The bottle was recently published in Robyn Hildyard, “Salt-Glazing in Woolwich,” Ceramic Review 263 (September/October 2013): 58–61

Dennis Haselgrove, “Steps towards English Stoneware Manufacture in the Seventeenth Century Part 2, 1650–1700,” London Archaeologist 6, no. 6 (Spring 1990): 152–59, fig. 8 (“WK” bottle).

Published in Robin Hildyard, European Ceramics (London: V&A Publications, 1999), p. 144. In retrospect I did the right thing in selling the pew group for £15,000. It provided quality capital for building up a new business, and over the subsequent three years that original capital has turned over eighty times.

Jonathan Horne, A Collection of Early English Pottery, Part VII (London: J. Horne, 1987), pl. 184.

Arnold R. Mountford, The Illustrated Guide to Staffordshire Salt-glazed Stoneware (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1971), pl. 23.

Horne, A Collection of Early English Pottery, Part XIII, pl. 354.

Leslie B. Grigsby, The Longridge Collection of English Slipware and Delftware, 2 vols. (London: J. Horne, 2000), vol. 2, Delftware, p. 122.

Horne, A Collection of Early English Pottery, Part XI, pl. 307.

Ibid.

Pat Halfpenny, English Earthenware Figures: 1740–1840 (1991; reprint, Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1995), p. 228, pl. 63, and p. 281.

Ibid., p. 192, pl. 50.