Dessert plate from set of ten, Caroline Harrison (1832–1892) on blank by Haviland & Co., Limoges, France, dated 1887. Overglaze painting on porcelain. D. 9". Mark: inscribed on underside, “Clam Creek. N.J. / C.S.H. ’87” (Unless otherwise noted, all objects courtesy Denker Collection; photos, Dana Moore.)

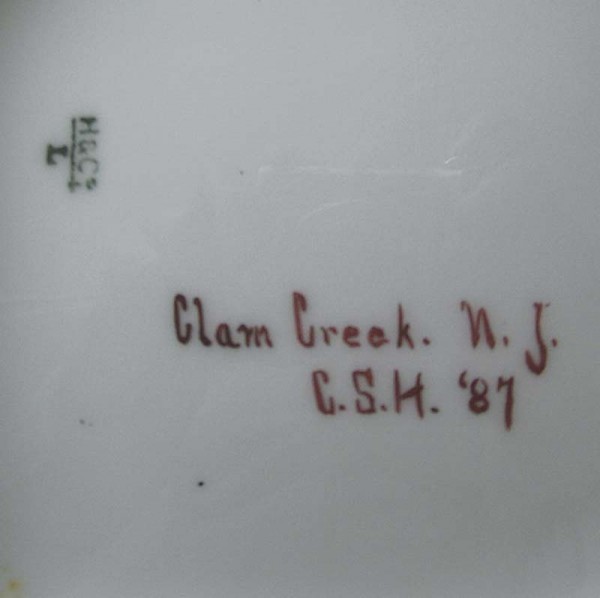

Underside of the plate illustrated in fig. 1.

Dessert plate from set of ten, Caroline Harrison (1832–1892) on blank by Haviland & Co., Limoges, France, dated 1887. Overglaze painting on porcelain. H. 1 1/4", W. 9". Marks: inscribed on underside, “Near ‘Gap’”; on small sign in left foreground, “Hope 1 MI”

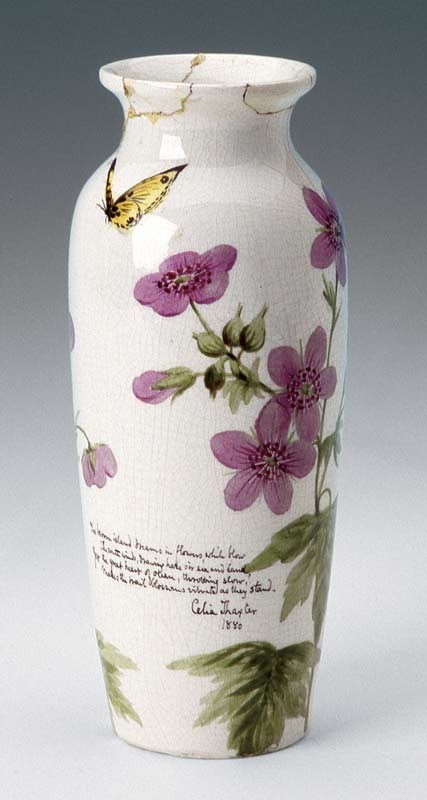

Vase, Cranesbill Geranium with Yellow Butterflies, Celia Thaxter (1835–1894), dated 1880. China paints on earthenware. H. 7 15/16". Mark: inscribed on side, “The barren island dreams in flowers, while blow / The south winds, drawing haze o’er sea and land, / Yet the great heart of ocean, throbbing slow, / Makes the frail blossoms vibrate as they stand. / Celia Thaxter / 1880” (Courtesy, Strawberry Banke, 1989.34.)

Turkish coffee set, Anna B. Leonard (ca. 1860–1937) on blanks by Delinieres & Co. (coffee ewer) and GDA [Haviland] (tray), Limoges, France, 1899. Overglaze painting on porcelain. Ewer: H. 11 1/2"; tray: D. 13 1/4". Marks: signed on ewer, “A B Leonard” and “ABL” monogram; signed on tray, “Anna B. Leonard / New York.” Paper labels on the bottom of the ewer read: “Price / $175.00 / set”; “Anna B. Leonard / 28 E. 23rd St / New York City / National Lea[gue of] / Mineral Pain[ters]”; and “N.Y. Society / of Keramic Arts / PRICE $17500”

Detail of the Turkish coffee set illustrated in fig. 5.

Illustration, “PARIS EXHIBIT—ANNA B. LEONARD,” Keramic Studio 1, no. 11 (March 1900): 230. The coffee set is shown in the center.

Vase, Wild Carrot, Maud Mason (1867–1956), on blank by Willets Manufacturing Co., Trenton, New Jersey, 1902. Overglaze painting on porcelain. H. 16". Mark: signed on bottom, “M.Mason / 1902”

Vase, Caroline S. Hofman (act. in china painting 1907–1912), New York, New York, on blank by Willets Manufacturing Co., Trenton, New Jersey, ca. 1910. Overglaze painting on porcelain. H. 17 3/4".

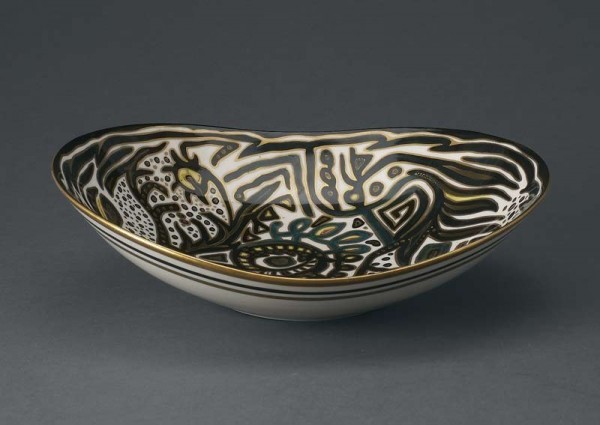

Bowl, Simon Lissim (1900–1981), on blank made by Castleton China, Inc., Castleton, Pennsylvania, 1952. Overglaze painting on porcelain. L. 11 1/8". Mark: signed on rim, “Simon Lissim”

Side view of the bowl illustrated in fig. 10.

Large bird platter, Ralph Bacerra (1938–2008), Los Angeles, California, 1976. Porcelain with enamels. D. 24". (Courtesy, The Newark Museum, Purchase 1986, Wallace M. Scudder Bequest Fund, 86.5.)

Covered jar, Iguana, Kurt Weiser (b. 1950), Tempe, Arizona, 1992. China paints on cast porcelain. H. 17 1/4". Mark: signed on bottom, “WEISER” (Courtesy, Collection of Arizona State University Art Museum, Purchased with funds provided by the ASU Art Museum Store, 1993.077.000.)

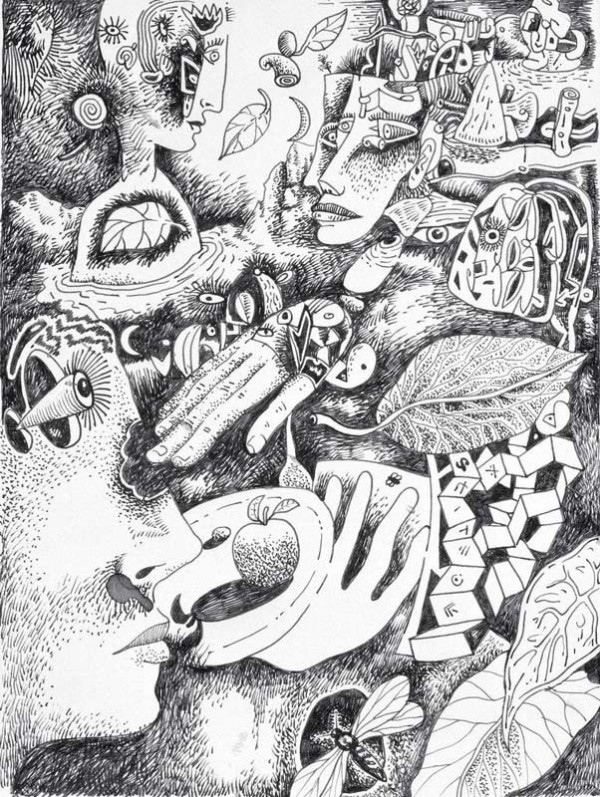

Untitled drawing (in flight over Kansas), Kurt Weiser (b. 1950), 1996. Ink on paper. 11" x 8 1/2". Signed on reverse. (Courtesy, collection of the artist.)

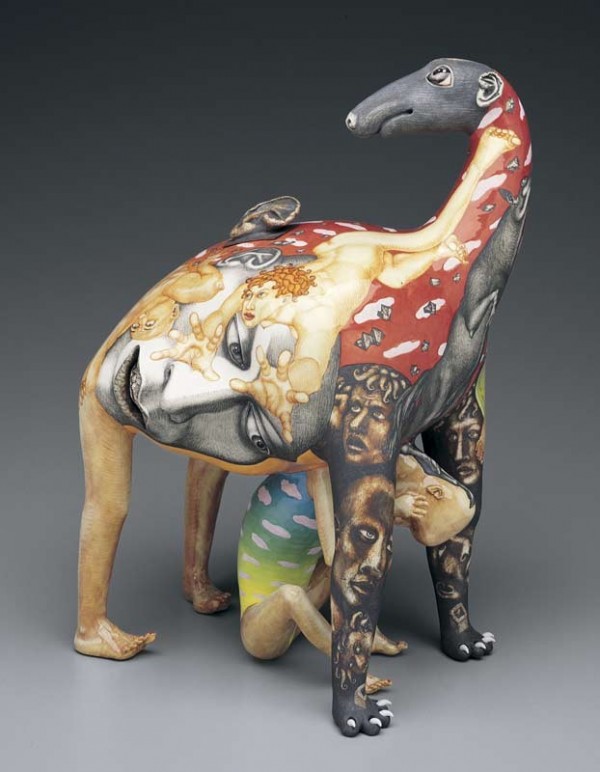

Stag Party or Looking through Darkness, Sergei Isupov (b. 1963), Louisville, Kentucky, 1998. Hand-built porcelain with stains and overglazes. H. 16 1/4". Mark: signed on proper left front leg, “ИСУПОВ” (Courtesy, Mint Museum of Craft + Design, Allan Chasanoff Ceramic Collection, 2003.91.16a–b.)

Post Binary Gender Choice, Kevin Snipes (b. 1963), New Mexico, 2012. Hand-built porcelain with overglazes. Overall H. 13". Mark: signed on bottom, “SNIPES” (Private collection; photo courtesy of the artist.)

Sound bites—whether written or spoken—are annoying. Here’s one I especially loathe: china painting was practiced primarily by ladies of leisure during the late nineteenth century. It is true that such painting was practiced by ladies of leisure in the late nineteenth century, but it was also done by others during the same time period: men and women who used their skills to make a living; artists who hoped to explore new materials and new ways of working with those materials; and designers developing new patterns for mass production. In fact, artists around the world have been executing overglaze painting on porcelain, so why suggest the ladies of the 1880s and 1890s were the sole practitioners?

To explore some of these issues, I chose ten of my favorite china-painted objects made between 1880 and the present. Further, in my choices I have made an arbitrary comparison between female china painters of the late nineteenth century and male china painters of the present day. Where did their goals merge or diverge? How have evolving materials affected their means of expression? In short, how are they similar and how are they different? Some discoveries were a surprise even to me. China painting on porcelain continues to evolve in ways that the early amateur practitioners might not have predicted, yet it remains a potent technique for artistic expression in any era.

Enamels made of metallic oxides and fixed at low temperature to the surface of biscuit- or glaze-fired porcelain bodies produce a wide range of brilliant colors that can be both decorative and expressive. When broadly defined, china painting encompasses a large body of ceramic material dating from at least the tenth century, when porcelain was invented in China. In order to interpret the contemporary manifestations of American china painting, my small selection of wares begins circa 1880, when women participating in the burgeoning amateur art movement in America became interested in developing china painting as an art.[1] At first, their instructors were drawn primarily from the immigrant male decorators who produced special commissions for the high-end ceramics trade. Later, some groups expanded their education to include teachers of design from academic art programs. These amateur women were empowered by their mastery of technology and technique and their inventions of design solutions on ready-made shapes. Their desire for instruction led in part to the establishment of university ceramic programs (Alfred, Rutgers, Ohio State, Newcomb College) in the shadow of the new century. These programs fostered technological developments of bodies and glazes and aesthetic experimentation with new modes of expression through clay.

Since the mid-twentieth century, artists have been rediscovering the artistic potential of low-fired enamels on high-fired bodies. Judy Chicago’s famous Dinner Party (1974–1979) stems from her 1972 find of a “beautiful porcelain plate painted with the most delectable roses,” which led her to investigate the techniques of painting on china as well as the social and artistic history of china painting in America.[2]

Chicago’s interest in china painting did not develop in a complete vacuum. Indeed, other West Coast ceramists were looking at color in a new way. The taste for Japanese ceramics as a source of inspiration in the 1940s and 1950s gave way to new influences from canvas painting and—surprisingly—china painting. Ron Nagle, whose mother was a china painter,[3] began working with china paints and luster glazes himself in the early 1960s. Nagle and Jim Melchert turned the ceramic department at the San Francisco Art Institute into a low-fire facility and influenced a generation of ceramists to use color in their work and to see porcelain as both sculpture and canvas. These artists were tapping into materials and processes that had been otherwise dismissed by academic artists.

I might have espoused the sound bite mentioned at the beginning of this short essay had I not stumbled across an unusual bowl at an antiques show more than twenty years ago. The blank form was made in a French porcelain factory, but it was painted in a completely abstract pattern by an artist I have not yet identified. It bore paper labels indicating it had been for sale in the shop of an unidentified arts and crafts society. I had to buy the bowl and find out more about how it came to be. Countless hours of reading china-painting periodicals and instruction manuals and searching for interesting examples formed the background for my choice of ten favorite china-painted objects.

Caroline Scott Harrison (1832–1892)

In many ways, Caroline Scott Harrison fits the current characterization of late-nineteenth-century amateur china painters—well-to-do, educated, married women with time on their hands beyond managing their households. And, like so many of her peers, she began her artistic development painting watercolors of flowers from garden and field. Those amateur artists who added china painting to their repertoire of skills often did so because their paintings were fixed to the china by fire and never faded. They also enjoyed the camaraderie of group classes and acquiring new fields of knowledge—in the case of painting on china, this included chemistry and plant identification as well as replicating floral forms and appearances.[4]

Caroline Harrison took her first china-painting classes in Indiana, with Paul Putzki (1858–1936), a German painter who had come to the United States about 1880 to work in an East Liverpool, Ohio, pottery but who made his living as an independent china painter by selling painted china and teaching amateurs. After her husband, Benjamin Harrison, was elected president of the United States in 1887, Mrs. Harrison invited Putzki to live in Washington, D.C., and continue to teach her. She held classes with him in the White House, along with many of the wives and daughters of her husband’s cabinet members.[5]

Mrs. Harrison’s interest in domestic issues and, especially, in china resulted in a new set of White House china for entertaining, which she designed in part. She also initiated the conscious collection of historic White House furnishings, which became a formal program much later in the twentieth century. Today’s popular China Room began with her plan to collect examples from the White House attic and cupboards of china used by past presidents.[6]

I found this set of dessert plates in a New Jersey antiques shop shortly after I had spent time at the Harrison home in Indianapolis studying Mrs. Harrison’s watercolors, painted china, and artist’s materials (fig. 1). The color and configuration of the enigmatic initials on the backs of the plates matched what I had seen there (fig. 2). I wanted to find out where the dealer had gotten the plates, but he would only say that they were from a wealthy New Jersey household.

In 1887, when these plates were painted, Mrs. Harrison would have been living in both Washington (as a U.S. senator’s wife) and Indianapolis. A few of the plates have titles. The one shown here is identified as “Clam Creek. N.J.”; another, showing a small sailing skiff, is labeled “near Atlantic City”; and others mention “Near ‘Gap’” (fig. 3) and “Glen Haven.” The group might have a New Jersey origin, but not all of the depicted places are identified on the plates. I have been unable to discover whether all the paintings refer to particular places or if some are metaphorical. Of course, the latter characterization adds a whole new intellectual dimension to what many think of as simple transcriptions of nature.

Celia Laighton Thaxter (1835–1894)

Celia Thaxter loved flowers. She loved to nurture them in her garden, she loved to praise them in poetry, and she loved to paint them—in watercolors, as book illustrations, and on china.[7] In her day, she was known for the summer resort she ran on Appledore, Isles of Shoals, off the coasts of Maine and New Hampshire, which became a summer salon for Boston’s vacationing artists and intellectuals. In addition to owning and running the inn and publishing her poetry, she illuminated pages of her books and painted china, which she sold to guests and others. Her guests included such literary and artistic luminaries as John Greenleaf Whittier, Childe Hassam, Nathaniel Hawthorne, William Morris Hunt, Sarah Orne Jewett, Ellen Robbins, Henry David Thoreau, and many others. Today she is probably best known for her book An Island Garden, which was published originally in 1904 and subsequently reprinted several times, especially in recent memory. She wrote it in the last year of her life “in response to the many entreaties of strangers as well as friends who have said to me, summer after summer, ‘Tell us how you do it!’”[8]

“Ever since I could remember anything,” she rhapsodized, “flowers have been like dear friends to me, comforters, inspirers, powers to uplift and to cheer....Summer after summer they return to me, always young and fresh and beautiful; but so many of the friends who have watched them and loved them with me are gone, and they return no more....How deep, how unbroken is that silence! But because of tender memories of loving eyes that see them no more, my flowers are yet more beloved and tenderly cherished.”[9]

An Island Garden was illustrated by Childe Hassam (1859–1935), a frequent guest, who was as enamored of Thaxter’s gardens set into the rocky land and pounding surf as he was of her. He wrote later that “Celia Thaxter was, I sometimes think, the most beautiful woman I ever saw, not the most splendid nor the most regular in feature, but the most graceful, the most easy, the most complete—with the suggestion of perfect physical adequacy and mental health in every look and motion. She abounded in life, it was like breathing a new life to look at her.”[10]

Art museums favor Thaxter’s china painted beautifully with olive branches and Greek inscriptions, as documents of her international travels.[11] But I prefer the china she painted with charming blossoms from her garden often displayed alongside a bit of poetry about floral nature, such as the vase shown here (fig. 4). They embody her daily crusade to garden in an inhospitable place, her practice of clipping favorite blooms with which to surround herself and her guests in the home, and her focus on them in her poetry.

Anna Burkhart Leonard (ca. 1860–1937)

Anna B. Leonard was ambitious in china-painting and art circles. Being a founder of Keramic Studio magazine and among the founders of the National League of Mineral Painters, Leonard created a personal niche in the upper echelon of American female artists. Born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1891 she founded the Louisville Keramic Club, and by the mid-1890s she had relocated to New York City, which was then one of the principal U.S. centers for female china painters. In 1899 she founded with Adelaide Robineau the now famous Keramic Studio, “a monthly magazine for the potter and decorator.”[12] Leonard managed the publication from New York City, while Robineau worked from her studio in Syracuse, New York. Leonard was also among those who, in 1906, met to create the National Society of Craftsmen, of which she became one of the first directors.[13]

In 1899, under the auspices of the National League of Mineral Painters, Leonard assembled an exhibit of American china painting that was sent to the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900. This coffee set was among that group of exhibits (figs. 5, 6).[14] The exhibition of these wares was not so much for the benefit of French and international attendees or sent out of any hope of winning one of the many awards that were handed out. It was meant to impress Americans who visited this world’s fair on their summer tour of Europe, and thus publicize their achievement back home (fig. 7).

By the time we acquired this coffee set, I had been reading Keramic Studio regularly and had a good idea of the artists whom I wanted in my collection as well as the styles of china painting that I wanted to represent. Anna B. Leonard was among those at the top of my list because of her involvement in organizing, publishing, and teaching the ceramic arts. I understood the decorative progression made by U.S. china painters from floral replication (in the style of dainty watercolors) to design and decoration (abstracted pattern making). Historic ornament was regularly used by adventurous painters to break out of the replication mode and enter the creative dimension of design. Design compendiums such as Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament (1856) were consulted regularly by china painters as a resource for historic ornament. Which publication Leonard might have consulted for her coffee set is unknown to me, but the ladies refer to the design as Russian, even though it is for making Turkish coffee. Perhaps she acquired the china first and later decided how to ornament it.

Maud Mary Mason, ANA (1867–1956)

Maud Mason began art instruction at the age of eleven and thought of herself as a canvas painter throughout her life. That is how she began her artistic career, coming to china only later, after she discovered she could paint flowers that others appreciated. In addition to painting skills, she studied design in anticipation of teaching, although it was her training in design, she said later, that led her to china. “The opportunity of making money as well as a love of beautiful things turned her attention [to china],” wrote Adelaide Robineau about Mason in a 1917 profile. “Then followed a steady grind for many years, when she worked like a slave but gained for herself great success in a financial way, still always seizing every opportunity of special study.”[15]

Mason arrived in New York City at an early age and studied with William Merritt Chase and Henry Snell. In Chase’s studio at the Art Students League (1893 and 1899–1902), she discovered flower painting: “One day I just got bored while working from a model in Mr. Chase’s studio, so I went out and bought a bunch of daffodils and painted them. Mr. Chase liked the painting, and so did everyone else, and later I showed flower paintings at the National Academy which were admired very much. Orders for flower paintings began to come in, and I have never had time to paint much of anything else.”[16]

Mason’s most important instruction may well have come from Arthur Wesley Dow, and the decorative consciousness she learned from him is most evident in this vase (fig. 8). The carrot tops, which appear to be representational, are displayed in front of a stream suggested by the gentle multiple curves so characteristic of Dow’s meandering line, which carries the viewer into the complexities of a subject that otherwise appears simple.[17] According to Robineau’s profile of Mason, “[s]he has been credited with being the first decorator to join Mr. Dow’s class and to come under his influence.”[18] These sensibilities translated into the design instruction for which Mason was also famous. Although she held classes in her studio, as many professional china painters did to supplement their income, she was also on the faculties of local art institutions.

Mason was active in arts and crafts groups throughout her long career, including the New York Watercolor Society and American Watercolor Society, the National Association of Women Artists (which she served as president), and Allied Artists of America, the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts (Craftsman from 1907 and Master from 1917) and the New York Society of Keramic Arts, among others. She enjoyed a long relationship with the National Arts Club as a member beginning in 1903, a participant on the board of governors and many of the club’s committees, and as a resident of its Nineteenth Street Studio Building from 1942 until her death in 1956. She sometimes gave instruction in sketching for the club.[19]

Robineau’s profile of Mason offers some insight into the relationship between canvas and china painting in Mason’s artistic experience: “Realizing that constant teaching is not conducive to healthful growth either mentally or physically, for the last eight or ten years she has given all her summers to painting out of doors and always endeavors even during her busiest winters to paint in the studio. When she gets back into the swing of ceramic work after this interval, she finds it more absorbing than ever and works with renewed and refreshed interest and feels that she does better for the change of work and thought.”[20]

Caroline S. Hofman (active early 20th century)

Caroline Hofman is something of a mystery, although we know she was active in china painting between 1907 and 1912. Fortunately, she left behind a series of instructional articles published in Keramic Studio during 1908. Taken together, the articles explain her work and her aesthetic point of view, both of which are demonstrated in this striking vase (fig. 9).

Although unsigned, this vase is firmly attributed to Hofman on the basis of historical evidence. We had no knowledge of its origins, but we bought it anyway because it is large, unusual, and beautiful. We figured we would identify the artist in another way. Later I found the vase illustrated in the June 1909 issue of Keramic Studio as having been shown by her at the annual exhibition of the New York Society of Keramic Arts. The exhibition reviewer noted that Hofman’s work was “individual” and that the vase exhibited “a delightful harmony of greys and pink.”[21]

At a time when china painters were arguing continuously about whether china decoration should look like realistic floral watercolors or be designed in a modern way that took advantage of the past in the invention of something new, Hofman’s series of articles, “Design for the Decoration of China,” explains the latter approach and sets it firmly within a developing understanding of the history of design. “Let us not suppose for a moment,” she admonished, “that an abstract treatment of flowers ever means the distortion of nature. It means a synthesis of nature, a simplifying and interpreting, a seizing of the whole charm and character, and adding to that a human inventiveness.”[22]

Hofman explained in the beginning of the series that good design was rooted in an appreciation and understanding of nature’s beauty: “[W]e find nothing more valuable, nor more filled with suggestions for beautiful pattern than plant form.”[23] She recognized that the line of the flower’s growth was the bedrock of design, and she challenged the designer to “seize the whole nature of it with a few strokes.”[24] Color harmonies, she counseled, should begin with “tones” that are “slightly grayed.” “Brilliant colors” should not be adopted until the student had become more sophisticated. She recommended especially Arthur Wesley Dow’s “Ipswich Prints” as being “beautiful and simple in their color and composition.”[25]

Hofman suggested working with two “harmonizing colors” on a toned ground. This vase demonstrates the aesthetic genius of her method. The toned ground is actually the muted cream color of the porcelain as made by Willets Manufacturing Company, which followed the Trenton, New Jersey, interpretation of the Irish Belleek body.[26] The whole of her design on this vase was executed in two “slightly grayed” tones.

Hofman recommends in her series that decorators experiment with new ideas by working out one’s design directly on the china without the mediation of careful sketches. This practice, she assured readers, would render “a certain freshness and individuality, just as all sketches do.”[27]

Simon Lissim (1900–1981)

Born in Ukraine, Simon Lissim was educated in his native Kiev and later studied in Paris, where he came into contact with other Russian émigré artists, including stage designers Léon Bakst and Sergei Diaghilev. Lissim lived, worked, and exhibited in Paris until 1940, when he became a volunteer with the French Army. His French exhibitions included stage and costume designs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre, the Théâtre National de l’Opéra Comique, among many others, and decorated porcelains made for the Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres. He was awarded a silver medal at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1925 and a gold medal at the International Exhibition at Barcelona, 1929. He began visiting the United States in 1935 and exhibited stage designs here the following year, first at Wildenstein and Company in New York City, and later in Syracuse, Oberlin, and at Swarthmore and other campuses.[28]

Lissim immigrated to New York City in 1941. In America he earned his living as an educator, first for the Art Education Project at the New York Public Library and later, after several other appointments, for the Adult Education Program of City College of New York, where he stayed for many years. He also designed for the stage and for American ceramics manufacturers, among them Lenox China in 1938 and Castleton in the early 1950s. The Lenox designs were exhibited at Georg Jensen’s New York store in 1941.[29]

Lissim returned to china design again and again, but few if any of his eccentric designs were produced. According to one biographer/critic, Lissim made about 550 designs for porcelains, of which about 300 were executed. One hundred of those made were singles, while another 175 were produced in editions of five or ten each. Thirty were produced as actual patterns for dinner sets or beverage services.[30] Lissim liked the idea that consumers could hold art in their hands with well-designed production wares. “I argue,” he said, “that to reproduce a beautiful design costs exactly the same as to produce an ugly one.”[31]

Like the women discussed above, Lissim painted his designs on prepared blanks. Unlike his female counterparts, he did so in the hope of producing multiples of his designs. The bowl illustrated here was painted on a blank, made by Castleton China, of the large open vegetable dish from the “Museum” service designed by Eva Zeisel (figs. 10, 11). Museum, the first postwar porcelain table service produced in the United States, was created by Zeisel through the association between a commercial entity—Castleton China—and a major nonprofit institution—The Museum of Modern Art—hence its name. Museum was designed in 1942–1943 and first exhibited in 1946.[32] Zeisel was adamant about the service being produced in white only, fearing that additional patterning would detract from the purity of her design for execution in porcelain, but Louis E. Hellman, Castleton’s founder and president, heard so many complaints about the starkness of their undecorated Museum production that he entertained ideas for patterns from a variety of artists.[33] This dish may be one of those.

Ralph Bacerra (1938–2008)

Ralph Bacerra was a painting major at Chouinard Art Institute when he took Vivika Heino’s ceramics class as an elective. He never really looked back, adopting porcelain as his canvas and the complexities of working with overglaze enamels as his medium: “[O]nce she started to talk, demonstrate, and the environment in the classroom, and I started to get more serious [about] working with the wheel and the clay and the glazes, I said this is for me....I dropped everything and switched my major to ceramics.”[34]

Bacerra earned a B.F.A. degree in 1961 at Chouinard and taught at the institution from 1963 to 1972. After leaving Chouinard, he worked for a decade as a studio artist until accepting a position as chairman of the ceramics department at Otis College of Art and Design in 1983. He retired in 1996, then traveled and worked in his Eagle Rock studio until his death in 2008.

I was surprised to realize that Bacerra’s artistic goals were similar to the earlier women discussed above. His work addresses the beauty of the decorated ceramic surface with a focus on ornamentation. This approach incorporates a variety of elaborate non-Western techniques, merging the influences of twentieth-century American studio ceramics with traditional Asian ceramics. Bacerra was one of the first potters to revive the highly decorated surface, using enamels and luster glazes in a new way: “I was really into the research and exploration of how the Chinese actually did what they did and the Japanese and the Koreans and the Thai because they all have a different feel and a different look....So that’s just through experimentation and knowing what your materials do, and that’s because of glaze technology that Vivika sort of shoved down everybody’s throat....Because she was very, very big on people knowing what materials do and what the components of the glaze do in the kiln at all the different temperatures.”[35]

In addition to the Asian influences that are easily recognized in his work, Bacerra acknowledged “the Blue Four”—the collection of works by Wassily Kandinsky, Alexei Jawlensky, Paul Klee, and Lyonel Feininger that was always on display when he visited the Pasadena Art Museum. He cited the work of Dutch artist M. C. Escher (1898–1972) as a source for his shapes within shapes that interlock like a puzzle (fig. 12). Additionally, Persian paintings and manuscripts and Japanese prints all harbored patterns that caught his eye: “[A]ll those things are sort of intuitive, I think. You do research, you read books, you see the shows, and they’re sort of in the back of your head, and as you begin to work, it all begins to come out.”[36]

Like Caroline Hofman, Bacerra worked directly with materials and eschewed the intermediate practice of designing first on paper: “My philosophy is you get in the studio and you get out the materials, and by using and working and actually putting the forms and the clay together, then the process begins.”[37]

Kurt Weiser (b. 1950)

Kurt Weiser seems to have had a ceramic artist’s conventional development. In fourth grade he learned to draw/doodle as a way to occupy periods of little active interest and perhaps illustrate his perception of the stories read to his class by his teacher. His parents encouraged his artistic proclivities. He became fascinated with ceramics as an art form at the Kansas City Art Institute, where he studied with Ken Ferguson, and he went on to get degrees, fellowships, and teaching jobs from distinguished academic programs. His work in stoneware was more or less conventional—workmanlike, but predictably in the mode of the contemporary Asian-style stoneware that predominated in the ceramic market of useful wares.[38]

In the late 1980s, at the end of his tenure as the director of the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Montana, Weiser’s work began to shift dramatically.[39] He started making slip-cast porcelain sculpture and then vessels (vases, teapots, covered baluster jars), familiar forms but a little quirky. Once he had adopted a porcelain canvas, his doodling caught up with his ceramic art. The introduction of color to his work through overglaze enamels allowed him to explore the narrative impulses that had been lurking since childhood, resulting in an explosion of lush, Eden-like landscapes filled with eccentric figures of men and women, amphibians, and insects portraying themes of lust, predation, scientific curiosity, and human vulnerability (figs. 13, 14). Since 1988, Weiser has made most of this current body of work during his teaching appointment at Arizona State University.

Narration is the new twist from the original focus of china decorators toward pattern and color, although china-painted vases of the early twentieth century often display continuous landscapes.[40] In Weiser’s work, the porcelain surface and brilliant underglaze colors set off an exploration of humans in the natural world, but distorted by the undulating surfaces of his vessels and globes.

As with the European china painters of old, Weiser’s overglazing process requires the careful planning necessary for layering multiple firings. The skills of the rich European and Asian china-painting traditions characterized by flower pieces and courtly conceits are set against Weiser’s penchant for surreal fictional narrative lurking in lushly painted landscapes. Some critics herald his work as a breakthrough in contemporary ceramic practice, calling him a postmodernist who is producing work informed by daydreams, study travels, and exotic fantasies.[41] I like the way he uses old skills to investigate enduring human themes, leaving the viewer impressed with his craft and lost in his exotic narratives.

Sergei Isupov (b. 1963)

Sergei Isupov’s attention to detail has been labeled fetishistic. To me, his small sculptures might more accurately be described as highly detailed—the kind of detail that comes from using exquisite glazes on fine-bodied porcelain. Isupov constructs his sculpture by rolling and flattening the clay and then wrapping the pieces into forms that suggest various body parts, usually arranged in strange, foreshortened, ambiguous configurations—are they human or animal, male or female, good or evil? The highly narrative, hyperrealistic surfaces are painted in a tightly controlled color palette, including Prussian blue, bright red, chrome yellow, black, brown, ochre, and occasionally some greens and blues, rendered as matte or glossy (fig. 15).

Isupov’s work invites both close inspection and wonder at his skill and command of his materials. Although we can call him a china painter on the basis of his materials and processes, his work defies the kind of polite classification we might assign to the earlier women, discussed above. Truth is, the ladies of a century earlier never considered personal narrative as a mode of expression, nor were they concerned with creating sculpture. Their conceptual problem was working out a pleasing design on a useful or ornamental shape determined by an industrial designer. Isupov’s work presents a stark contrast to their china-painted objects: “I find clay to be the most versatile material, and it is well suited to the expression of my ideas. I consider my sculptures to be a canvas for my paintings.”[42]

Born into a family of artists who identify themselves as Ukrainian, Isupov studied at the Ukrainian State Art School and the Art Institute of Tallinn, Estonia, where he was awarded both a B.A. and an M.F.A.[43] His professional artistic career began in 1990 with his first exhibit, in the Oslo International Ceramic Symposium in Norway. Later, his work was included in “USSR Ceramicists,” a charity exposition at the Hammer Center in Moscow, and in “New Soviet Art,” at Fourth Dimension Gallery in San Francisco. Isupov also exhibited in group shows in Europe and Asia before immigrating to the United States in 1994.

In Isupov’s work, the rich history of Russian literature, classical music, dance, and avant-garde art movements comes in direct contact with the dynamic capitalism of American life. He has one foot securely planted in each culture, drawing on his heritage to illuminate his personal relationship to American culture. His purpose is not verisimilitude, as he has said: “Why do I need to re-create life if it is already there?” His goal is for his work to be publicly exhibited, where it invites appreciation of his skill and analysis of his meaning. According to the artist, “Decorative objects are to be lived with in the home; but my work is hard to live with, so it is more at home in the museum, or gallery where the disturbing is possible.”[44]

Kevin Snipes (b. 1963)

As a contemporary African-American artist using china paints and hand-built porcelain as his vehicle of expression, Kevin Snipes defies the old stereotype that china painting is an antiquated hobby of rich white ladies. Snipes creates a dynamic body of work by combining unconventional porcelain forms with an obsessive need to draw on everything. The forms enhance his themes of duality, whereas his drawing materials are the recently developed Speedball china paints delivered through pens and combined with an old Korean technique called mishima.[45] Together these materials and techniques satisfy his desire to create narrative drawings in three dimensions (fig. 16).

Snipes was born in Philadelphia, but grew up mostly in Cleveland, Ohio. He received a B.F.A. in ceramics and drawing from the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1994 and finished graduate school at the University of Florida in 2003. He was a resident in several programs, including Philadelphia’s Clay Studio and the Watershed Center for Ceramic Arts in New Castle, Maine. In 2008 he received a Taunt Fellowship from the Archie Bray Foundation in Montana. His work has been widely seen in national and international exhibits, including recent solo exhibitions at the Society of Arts and Craft in Boston, Akar in Iowa City, and Duane Reed Gallery in St. Louis, as well as in Jingdezhen, China, perhaps his farthest venue.

Snipes is obsessed with the concept of duality, which he readily addresses in his work:

I am continuously fascinated by the concept of duality. Duality[,] of course, refers to two things which are intrinsically bound together, made of the same stuff. Yet those things are also inherently in opposition with each other. This is nothing new. Such things as lightness and darkness, and day and night, can only exist by acknowledgement of their oppositions and duality. But what I find most interesting is the way that we define one side of the duality is by describing what is not. In other words, we can only know a thing by defining its opposite. How is it possible to describe what lightness is, for instance, without referring to the concept of darkness, or to describe what rigidity is without describing softness? These thoughts are my starting point in the act of creating....

As an artist, and as a member of a historically marginalized group, I find that I tend toward nontribalism. Rather [than] creating art that speaks of love or victimization of African Americans, I speak of the problems underlying the recognition of difference. I work on a personal, intimate level that encourages an almost private investigation of the objects that I make. This act of confrontation, that encourages only a single viewer with a single object[,] sets up a dialogue in the nature of subject-to-object relationships and becomes a metaphor for the concept of otherness.[46]

ELLEN PAUL DENKER is a museum consultant and independent scholar based in western North Carolina. She received her B.A. in cultural anthropology from Grinnell College, Iowa, and an M.A. from the University of Delaware, where she was a fellow in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture.

As a museum consultant, Ellen has worked on a variety of exhibition topics, from ceramic and furniture history to visiting nursing and blindness. She has written extensively on American ceramics, the Arts & Crafts movement, and American home furnishings. Ellen recently finished a large project in High Point, North Carolina, funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, a federal agency. As director of the North Carolina Furniture Heritage Project, she prepared a major exhibition on twentieth-century Piedmont factory-made furniture for the High Point Museum and spearheaded a movement to create a permanent Furniture Heritage Center in High Point.

The list of publications to which Ellen has contributed as author or co-author is extensive, ranging from Lenox china to rocking chairs. Recent titles are Faces & Flowers: Painting on Lenox China, China and Glass in America, 1880–1980: From Tabletop to TV Tray, and Byrdcliffe: An American Arts & Crafts Colony, which was awarded the 2007 Henry Allen Moe Prize from the New York State Historical Association. Her article on designers of American parian porcelain statuary, published in Ceramics in America, received the Robert C. Smith Award from the Decorative Arts Society for best decorative arts article of 2002.

For more information about this phenomenon, see Ellen Paul Denker, “The Grammar of Nature: Arts and Crafts China Painting,” in The Substance of Style: New Perspectives on the American Arts and Crafts Movement, 1990 Winterthur Conference Report, edited by Bert R. Denker (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum and University Press of New England, 1996), pp. 281–300; and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, “Aesthetic Forms in Ceramics and Glass,” in Doreen Bolger Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986), pp. 198–251.

Judy Chicago, “World of the China Painter,” in Overglaze Imagery: Cone 019-016 (Fullerton: Visual Arts Center, California State University, 1977), pp. 113–54. The Dinner Party shows a giant ceremonial banquet with thirty-nine place settings for famous women, each consisting of embroidered runners, gold chalices and utensils, and china-painted porcelain plates. It is currently on long-term installation in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.

. Oral history interview with Ron Nagle, July 8–9, 2003, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Denker, “Grammar of Nature.”

Ellen Paul Denker, “Liberating the Creative Spirit: China Painters of Indiana,” Traces 6 (Winter 1994): 30–35.

Margaret Brown Klapthor, Official White House China, 1789 to the Present, 2nd ed. (New York: Barra Foundation, in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1999), pp. 127–31. For another Caroline Harrison biography, see National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site, www.firstladies.org/biographies/firstladies.aspx?biography=24.

. For more information on the painterly aspects of Thaxter’s work, see Sharon Paiva Stephan, One Woman’s Work: The Visual Art of Celia Laighton Thaxter (Portsmouth, N.H.: Portsmouth Athenaeum, in association with Isles of Shoals Historical and Research Association, 2001).

Celia Thaxter, An Island Garden (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1904), p. vii.

Ibid., pp. v–vii.

Hassam, quoted in Catherine Hoover Voorsanger, “Dictionary of Architects, Artisans, Artists, and Manufacturers,” in Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty, p. 472; quoting from Rosamond Thaxter, Sandpiper: The Life and Letters of Celia Thaxter, rev. ed. (Francestown, N.H.: M. Jones Co., 1963), p. 88.

Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty, fig 1.3, p. 31.

In today’s publications, Robineau is generally given credit for the founding of this publication, but a note in the New York Times of February 10, 1907, identified Leonard as the person “who founded and for four years edited The Keramic Studio.”

Spencer Trask was elected president and Arthur Wesley Dow, vice president. The organization met in the rooms of the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park, of which Trask was also president.

For illustration of Leonard’s submissions, see “Paris Exhibit—Anna B. Leonard,” Keramic Studio 1, no. 11 (March 1900): 230. The coffee set is shown in the center.

Adelaide Alsop Robineau, “Miss Maud M. Mason,” Keramic Studio 18 (February 1917): 160.

Quoted in L.C.B., Memorial Exhibition: Maud M. Mason, ANA, 1867–1956, exh. cat. (Memphis, Tenn.: Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, 1957), unpaginated.

The vase was included in an annual exhibit of the New York Society of Keramic Arts and is referred to as “The Wild Carrot vase of Miss Maud Mason” in Keramic Studio 4, no. 11 (March 1903): 237.

Robineau, “Miss Maud M. Mason.”

For Mason’s biography, see Carol Lowrey, A Legacy of Art: Paintings and Sculptures by Artist Life Members of the National Arts Club (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2008), pp. 50–51.

Robineau, “Miss Maud M. Mason.”

Exhibition review of “New York Society of Keramic Arts,” Keramic Studio 11, no. 2 (June 1909): 34.

Caroline Hofman, “Design for the Decoration of China (5th installment),” Keramic Studio 10, no. 4 (August 1908): 86–87.

Caroline Hofman, “Design for the Decoration of China (2nd installment),” Keramic Studio 9, no. 10 (February 1908): 226–27.

Ibid.

Caroline Hofman, “Design for the Decoration of China (3rd installment),” Keramic Studio 10, no. 1 (May 1908): 15–17.

For more on the relationship between Irish Belleek and Trenton Belleek, see Ellen Paul Denker, “Trenton’s Belleek: Discovery and Triumph in American Ceramic Art,” Style 1900 7 (Winter 1994/95): 18–23.

Hofman, “Design for the Decoration of China (5th installment),” p. 87.

Biographical information on Lissim and illustrations of his work may be found in George Freedley, Simon Lissim (New York: James Hendrickson, 1949), and Raymond Lister, Decorated Porcelains of Simon Lissim (Cambridge, Eng.: Golden Head Press, 1955).

For examples of Lissim’s designs for Lenox China, see Ellen Paul Denker, Lenox China: Celebrating a Century of Quality, 1889–1989 (Trenton: New Jersey State Museum, in association with Lenox China, 1989), p. 53; and Ellen Paul Denker, Faces & Flowers: Painting on Lenox China (Richmond, Va.: University of Richmond Museums, 2009), p. 67.

Lister, Decorated Porcelains, p. 17.

Ibid., p. 18.

For more on the Museum pattern, see Mary Whitman Davis, “Castleton China Company: Museum,” in Pat Kirkham et al., Eva Zeisel: Life, Design, and Beauty (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2013), pp. 66–70.

Charles Venable et al., China and Glass in America, 1880–1980: From Tabletop to TV Tray (Dallas, Tx.: Dallas Museum of Art, in association with Harry N. Abrams, 2000), p. 465.

Oral history interview with Ralph Bacerra, April 7–19, 2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, p. 3.

Ibid., p. 12.

Ibid., pp. 14–15.

Ibid., p. 16.

For additional biographical information on Weiser and examples of his stoneware, see Peter Held, ed., Eden Revisited: The Ceramic Art of Kurt Weiser (Tempe: Herberger College of the Arts, Arizona State University, 2007).

The Archie Bray Foundation is a private, nonprofit educational institution founded in 1951 that provides a stimulating place for resident artists to develop creative work in ceramics.

For an example of this phenomenon, see Denker, Faces & Flowers, pp. 26–27.

Held, Eden Revisited, preface.

Artist’s website: http://sergeiisupov.com/about/artist-statement.

Sergei Isupov comes from a creative family. His mother, Nelli Isupova, is a ceramics folk artist; his father, Vladimir Isupov, and younger brother, Ilya Isupov, are painters. All three are well known in their home city of Kiev, Ukraine.

Quoted in David Jones, “Breaking through Illusions: Sergei Isupov,” Ceramics: Art and Perception 91 (2013): 95.

Mishima is a technique of inlaying slip, underglaze, or even clay into a contrasting clay body of the piece being made. The technique allows for extremely fine, intricate design work with hard, sharp edges. Mishima was first produced in Korea during the Koryo˘ period (935–1392), resulting in the stunning Korean celadons of the twelfth and thirteenth century. The term now refers to a type of pottery resulted from comparing the Korean ware with the script used on calendars created at the shrine at Mishima in Japan. Creating a mishima piece basically involves six steps: forming the clay pot, incising the design, filling the design, removing excess material, drying the piece, and firing. Snipes uses mishima in combination with sgraffito, china paints, and wax resist.

For Snipes’s full statement about his work, see www.mudfire.com/kevin-snipes-constructed.htm.