Dish, Cauldon Works, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, England, 1894–1905. Whiteware. L. 14 1/2". Impressed: “CAULDON”; “14”; printed mark: “England” (Author’s collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

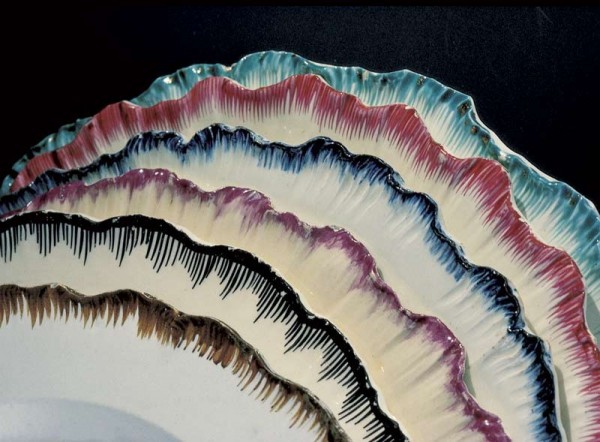

Group of creamware and pearlware shell-edge plates illustrating the range of colors of enamel and underglaze decoration, Staffordshire and Yorkshire, England, 1780–1790. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

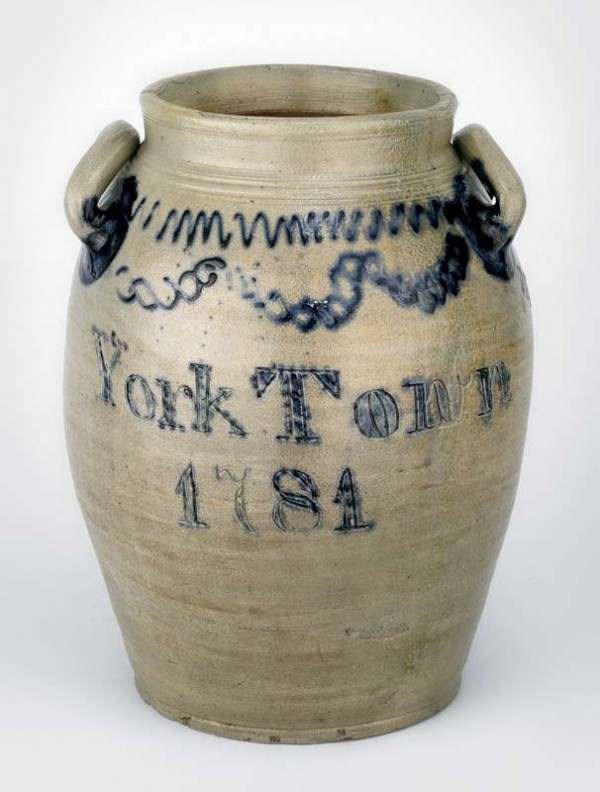

Storage jar, attributed to William H. Morgan, Baltimore, ca. 1824. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". Inscribed on both sides: “York Town / 1781” (Private collection.)

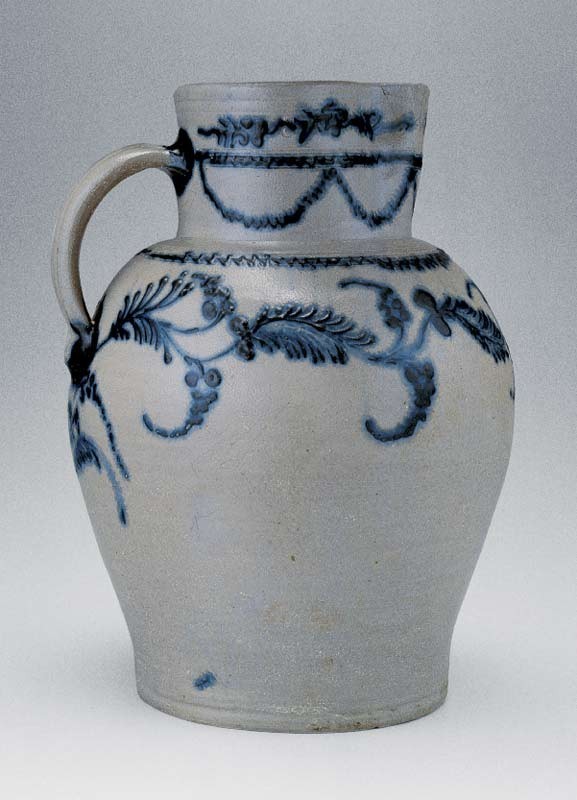

Pitcher, attributed to William H. Morgan, Baltimore, 1820–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. Dimensions not recorded. Capacity: 5 gallons. (Private collection.)

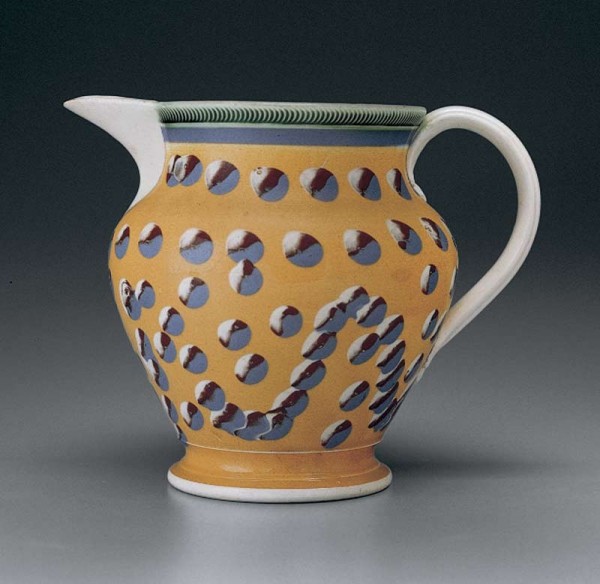

Jug, Great Britain, ca. 1835. Pearlware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Jonathan Rickard.)

Close-up views of the three colors of slip as they emerge from the three tubes of the slip cup. They form a single droplet yet maintain the individual colors that will compose any of the types of decoration for which this tool is used. At right, note the smaller, secondary droplet falling behind the tricolored droplet falling from the slip cup. The image below shows a single cat’s-eye immediately after the slip fell onto a dry surface. A secondary cat’s-eye is visible in the center of the larger one.

Tray, James Neale and Robert Wilson Company, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1790. Porcelain. L. 15". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Robert Sayer, Telling Fortune in Coffee Grounds, London, April 10, 1790. Colored engraving on laid paper. (Courtesy, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.)

Basket, American China Manufactory (Bonnin and Morris), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, April 23, 1773. Soft-paste porcelain. W. (including handles) 6". Mark, inscribed on base in underglaze blue: “PHILADELFIA / the 23 April 1773 / 4.7” (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the bottom of the basket illustrated in fig. 9.

Inkstand, William Crolius, New York, New York, 1773. Salt-glazed stoneware. W. 5 1/2". Inscribed, on bottom: “New York July 12 1773 / William Crolius” (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Partial and Promised Gift of David Bronstein, 2012; 2012.574a–c.)

Detail of the inscription on the bottom of the inkstand illustrated in fig. 11.

An “exploded” view of the clay components that make up a Bonnin and Morris pickle stand. Each of these molded and modeled objects had to be prepared prior to assembly. More than seventy separated elements were required to re-create this object. (Courtesy, Michelle Erickson.)

Pickle stand, Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Virginia, 2007. Porcelain. H. 5 1/2". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Cradle, North Devon, England, 1698. Sgraffito slipware. L. 9". Inscribed: “[16]98 / SD” (Private collection.)

Detail of the end panel of the cradle illustrated in fig. 15.

Mug, James Morgan, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1785. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4". Mark: inscribed “No. 45” (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the incised bird from the mug illustrated in fig. 17.

Left: Mug fragment adhered to kiln prop, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque earthenware. Right: Mug, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1774–1786. Bisque earthenware. H. 5 7/8". (Collection of Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Cream jug, John Bartlam and Associates, probably Camden, South Carolina, 1775–1780. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

My introduction to ceramics came at the age of eight, when I took slip-casting classes from Sister Rosa at St. Joseph’s Villa in Richmond, Virginia. Sister Rosa was in the Order of Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul (think Sally Field, the Flying Nun). Her slip-cast ceramics included wonderful crèche sets, one of which was used by our family every Christmas. I recollect pouring slip, trimming away casting lines, decorating vases and figures, and waiting for the kiln results. Most of all, I remember the feel and smell of wet clay. I still keep several of those childhood ceramic projects on display in my home.

Junior high school came and I took my electives in art classes, not that I had any semblance of artistic talent, but I felt more comfortable around paints, drawing pads, clay, and plaster. Most important, perhaps, the boy-to-girl ratio in art class was much more in my favor than in the shop classes.

During my high school years, I was exposed to historical ceramics through my mother, who was an enterprising antiques dealer—the cupboards were always filled with blue-and-white plates and American stoneware crocks. In college, while pursuing an anthropology degree, I enrolled in experimental archaeology courses and learned to pit-fire hand-coiled pots using native clays. I also took a pottery class, which was a wonderful respite from statistics and Latin.

After graduate school, degree in historical archaeology in hand, I accepted a staff position at Colonial Williamsburg. There I became acutely aware of both the social and ideological gulf between archaeology and the decorative arts. Archaeologists are left with the everyday things that people used, broke, and discarded. Conversely, decorative arts curators venerate objects that have survived for aesthetic, historical, or economic reasons. While both fields have their strengths, both also have weaknesses. I was struck then—and am still dismayed—by how little real communication and collaboration occur between them.

My career in archaeology led to the directorship of The William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research. I was up to my neck in broken crockery there, but even so I felt a sense of incompleteness in archaeology’s lack of object-based scholarship. When a part-time assistant curatorship working with ceramics and glass at Colonial Williamsburg became available, I jumped at the opportunity to work with Senior Curator John Austin and those world-class collections of eighteenth-century pottery and porcelain. Many close to me thought I had lost my mind, but I knew that I wanted indoctrination into the decorative arts world. The decision had many consequences, of course, both good and bad, but it did give me access to the doors, and drawers, of the world’s major museums.

I helped acquire a number of significant objects while at Colonial Williamsburg, including an eighteenth-century copy of Josiah Wedgwood’s Portland Vase and the ultimate Chelsea porcelain sculpture, William Hogarth’s dog Trump. I learned the secrets of auction bidding at Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the ins and outs of negotiating with the esteemed and mysterious London ceramics trade, and how to engage in the social rituals of the upper-crust ceramics collectors whose homes were filled with antique treasures.

As I was responsible for selecting the appropriate ceramics to furnish Colonial Williamsburg’s historic buildings, I came to know Michelle Erickson, who was making remarkable seventeenth- and eighteenth-century reproductions. One of our first collaborations was my order for twenty-five delft and redware chamber pots for the Raleigh Tavern. Watching Michelle’s work on this commission made it clear to me what a valuable resource she is to the decorative arts audience.

After leaving Colonial Williamsburg in 1994, Michelle, Ginny Lascara, and I formed a partnership in Period Designs, a business specializing in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century decorative arts. We provided a range of services for historic house museums, collectors, and even Hollywood movie sets. I also became a full-time antiques dealer with my partner Sam Margolin and had numerous private and museum clients. I was thrilled when I sold the British Museum its first (and probably only) example of eighteenth-century American stoneware: a David Morgan jug.

In 1999 Jon Prown, a former associate at Williamsburg, became executive director of the Chipstone Foundation. Taking advantage of our connection, I proposed the idea of Ceramics in America as a companion journal to Chipstone’s American Furniture, edited by my friend and colleague Luke Beckerdite. My vision of the journal was a reflection of my interdisciplinary professional journey, and I ambitiously hoped to reach “collectors, historical archaeologists, curators, decorative arts students, social historians, and studio potters.” The inaugural issued launched in 2001 and my ceramic life has been a whirlwind ever since, taking me places that I could only imagine as a young scholar. Much of the journal’s success is due to others, and I am lucky to have such a wonderful support team. Whether the objectives of the journal have been met I’ll leave to future scholars to decide. For now, I hope this prologue will provide the reader with some basis for evaluating the ten objects that are milestones in my career.

Shell-edged Dish

The “Damascus Road moment” in my ceramics career occurred on a sunny day in March 1978 in the Virginia Commonwealth University archaeology lab. I was standing at the sink, helping to wash artifacts found on a recent field survey. Trained as a prehistorian, I was attentive to the brown bits of stone and Native American pottery in the bulging artifact bags. Every so often, however, small fragments of bright blue-edged earthenware would pop up in the washing trays.

Working nearby, my classmate Leslie Brown, who had just finished working on a colonial period site, said, “Oh, you have some pearlware.... Noël Hume says that dates to 1780.”[1] I was stunned that something so seemingly insignificant could be so tightly dated, almost like pulling a coin from the ground. I didn’t know who Noël Hume was, but I quickly acquainted myself with his Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America, the widely proclaimed bible for historical archaeologists.[2] I became fascinated with the history of British and European ceramics and endeavored to learn all I could about these mysterious objects.

Soon after this epiphany, I spotted the blue shell-edged dish (fig. 1) in an antiques shop and spent what seemed, for a student, an enormous sum on this eighteenth-century treasure. After bragging to family and friends of my newfound antiquarian savvy, someone pointed out that the mark on the reverse, which partially read “England,” could be no earlier than 1891, when the McKinley Tariff Act required that the country of origin be stamped on imported ceramics. I was devastated! Not so much by the fact that I had foolishly spent twenty-eight dollars on a twentieth-century revival piece, but that I had made such a fool of myself with my irresponsible boasting. I was sick with the realization of how much I didn’t know.

I soon found out that very few others knew anything about English shell-edged ceramics either. This was ironic then and remains so today, as the pattern was the most popular design ever produced in the history of Western ceramics. Collectors erroneously called the ware “feather-edge” and “Leeds,” and major ceramics dealers and auction houses were not much more knowledgeable, although that is slowly changing.[3]

I attribute the start of my ceramics history career to my initial mistake, and since then I have worked vigorously to learn all I can on the subject. The search for “shell-edge” led me to a longtime friendship with ceramics guru George Miller. George and I have jointly published several major articles on shell-edge.[4] I am particularly proud of our 1994 Antiques article, in which I was able to interject some gloriously photographed images instead of the depressing academic style of archaeological illustration (fig. 2).[5] We are still mining the depths of this topic—a full-length book lies ahead—as new examples keep popping up in the antiques market and in the ground. And yes, I’m still making mistakes.

A Revolutionary Pot

Yorktown, Virginia, has always played a prominent role in my career. While it is best known as the location of the deciding battle of the American Revolution, Yorktown was also a thriving eighteenth-century seaport, from which tobacco and other homegrown products were sent to England in exchange for the latest and most fashionable goods. Yorktown was also home to America’s first successful stoneware manufacturer, William Rogers, who operated on an industrial scale from 1720 until his death in 1742.

I know Yorktown top to bottom. As a young archaeologist, I spent two summers scouring the river sediments in search of scuttled British ships related to that October 1781 event. In partnership with other colleagues, for sixteen years I also operated Period Designs, from an eighteenth-century building on Yorktown’s Main Street, a block away from the excavated site of William Rogers’s circa 1720 pottery kilns.

When my friend Marshall Goodman called on a winter afternoon to say he had heard of an American stoneware jar coming up for sale that was inscribed “York Town / 1781” (fig. 3), I immediately said that the existence of such an object was impossible and that it had to be a fake or, at best, perhaps a Centennial revival made as a commemorative in 1881. However, after I saw the fuzzy emailed photos, my opinion soon changed.

Certainly it was not made in 1781 and definitely not made in Yorktown, but the style of the slip-trailed zigzag and chain motifs around the shoulders was familiar. The open handles also suggested circa 1820 for mid-Atlantic stoneware styles. The characteristics of the decoration and clay body were reminiscent of a massive 1820–1825 Baltimore stoneware pitcher (fig. 4) I had sold several years earlier.[6] The next question was why a Baltimore potter would reference, in the middle of the 1820s, the Yorktown battle.

The answer came when I recalled the history of the marquis de Lafayette, a major general in the armies of the United States, and his decisive role in the battle of Yorktown in 1781. Lafayette had returned to the United States in 1824 for an eleven-month-long triumphant tour of the country. Welcomed back as a returning hero, his visit was heralded with much fanfare, including a well-documented stop in the City of Baltimore.[7] Additional research revealed that Lafayette had been especially revered by Baltimore’s citizenry for his efforts during his encampment outside the city in 1781, prior to his march to Yorktown. With a little imagination, it was not hard to see this jar proudly displayed in a merchant’s window during the general’s 1824 visit, possibly something the general himself gazed upon.

Found in an attic, the jar was part of an estate that consisted largely of vintage Christmas ornaments, used furniture, antique farm implements, and costume jewelry. Unfortunately, with the advent of the internet nothing is secret any longer, and a handful of notable dealers showed up on the morning of the sale. I was convinced, however, that I was the only one who fully understood the historical context of this jar. Nonetheless, bidding was strong and when this extraordinary example of Americana was sold, the final price left the astonished mom-and-pop crowd gasping.

Commemorative ceramics are among mankind’s oldest ways of recording consequential historic events. For students of American ceramics, what common, everyday object could be more poignant than one bearing references to the deciding battle of the American Revolution and the remembrance of one of our nation’s most beloved heroes? For me, no single stoneware object speaks more loudly about becoming American than this humble jar.

The Little Drip Always Follows the Big Drop

Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of my tenure with Ceramics in America has been the continual visual feast of ceramics of all sorts, from humble earthenware chamber pots to the spectacularly ornamented porcelain masterpieces of America’s industrial age. This aesthetic experience has been heightened by looking through the extraordinary lens of photographer Gavin Ashworth, who is without question one of the linchpins of Chipstone’s publications. Not only can Gavin take a pretty picture, his photographic process often becomes part of the essential detective work of ceramic and stylistic research.

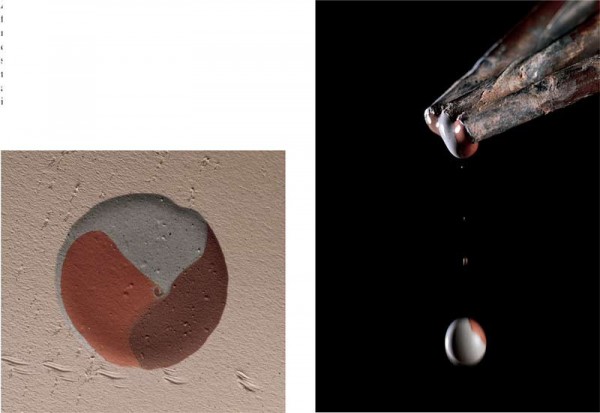

During the course of shooting an article for authors Jonathan Rickard and the late Don Carpentier on the so-called mocha wares, Gavin’s stop-action photography solved one of the minor technological mysteries of English ceramics.[8] Collectors and curators are well aware of the slip-trailed mocha pattern known as “cat’s-eye,” which appears on the jug illustrated in figure 5. This pattern was created with a special device or cup that channeled three colors of slip into a single drop. The drop was then allowed to fall onto the surface of a mug, bowl, or jug, either as a single cat’s-eye or combined into a string of successive drops to create what is called “cabling.”

Close examination of these cat’s-eyes on antique mocha ware shows the existence of a much smaller cat’s-eye within the large drop. Many of us had assumed this was similar to the splashing effect often seen in stop-action photography of water drops. However, when Gavin turned his camera on Don’s reenactment of the original process, a smaller drip coming off of the slip trailer’s tube was recorded (fig. 6). Repeated attempts showed that this smaller drop always followed the larger drop, and period mocha wares confirm that this happens virtually every time. A physicist friend who once saw me lecture on this provided a scientific explanation of this phenomenon, which, he said, often poses problems for contemporary industrial manufacturers. For the British and American makers of mocha ware, however, the added effect may have been regarded as a bonus, creating a simple but provocative decorative effect.

The capture of this arcane ceramic experience remains a highlight of my experiences in the field with Gavin, and a testament to the interpretative power of a great photograph. And if you ever have the chance to examine a cat’s-eye up close and personal, I guarantee you will see the small drip forever trapped within the larger drop.

Neale and Wilson Dish

I recall like it was yesterday the rainy afternoon I stepped into Alistair Sampson’s Brompton Road shop in London. I was visiting England for a week, making the rounds of the museums and the then numerous London antique shops; Alistair was one of the world’s premier English pottery dealers. As soon as I saw the tea tray, I knew the interpretative value it would have for numerous American museums interested in eighteenth-century tea-drinking rituals, fashion, and interiors (fig. 7). Before asking to examine the dish, I read its label, which pronounced that this was a rare example of Staffordshire pearlware, circa 1790, and attributed to the partnership of James Neale and Robert Wilson. Indeed, the tray was marked with their stamp, “Neale & Wilson.” I was familiar with the firm, which had worked in Hanley in the late eighteenth century and made beautiful creamware and pearlware. Most of my attention, however, was drawn to the enameled decoration and its nearly mint condition. I went on to buy the tray, the price of which was considerable by my standards, and made arrangements for my friend and London antique dealer Garry Atkins to ship it to me in America.

After I returned home and before the dish arrived, I showed the curators at Colonial Williamsburg some photographs of it. I knew they would be thrilled with the possibility of acquiring this object. In addition to the wonderful domestic scene taken from a print (fig. 8), marked Neale and Wilson pearlware was relatively rare and no examples were in the Colonial Williamsburg collection. They purchased it, based on the photos, and I was happy that the tray would have a home in the collection.

When I unwrapped the well-packed box that arrived at my home, I was still amazed at the immaculate condition of the dish. I held it up to overhead light to examine closely the presence of any restorations or other defects. In doing so, I became aware that I could see the shadows of my fingers through the tray. It took me a little longer to fully comprehend the implication of the fact that pearlware, a refined earthenware, was never translucent; only porcelain transmitted light. How had my rare pearlware dish transformed into porcelain on its journey across the Atlantic?

A quick visit to my British ceramic books revealed that Neale and Wilson not only made pearlware and creamware, they also were listed as makers of porcelain, a fact of which I had been, of course, unaware. In her book on the subject, Diana Edwards wrote that their porcelain was “unlike any other porcelain produced before in Staffordshire. Longton Hall was a fritted variety of soft-paste porcelain; New Hall produced a true hard-paste porcelain, and the Neale fabric corresponded to a bone porcelain of an earlier variety which incorporated bone ash.”[9] Even more important is that the dish is one of only a handful of marked examples of Neale & Wilson porcelain.[10] I will always be thrilled to have brought this wonderful object to light; it testifies that even in the most exalted dealer shops, hidden treasures can be discovered, sometimes with little more than old-fashioned dumb luck.

1773 Bonnin and Morris “Philadelfia” Porcelain Basket

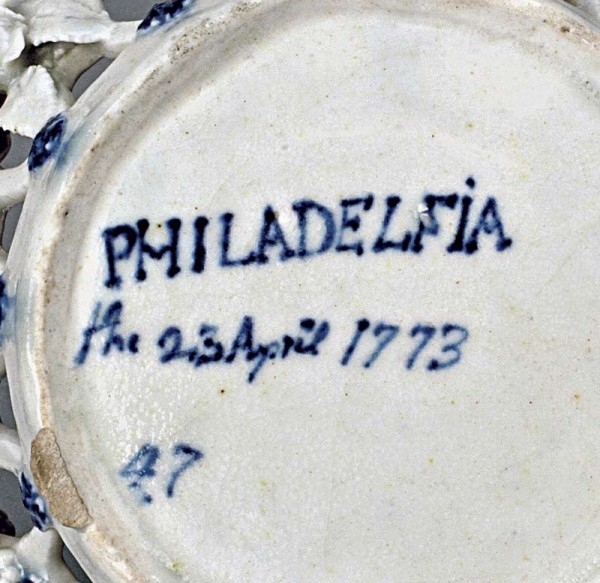

The most enigmatic of all the porcelain objects attributed to Philadelphia manufacture is a small openwork basket (fig. 9) that came to light in 1990 when it was offered for sale at Skinner’s auction house in Boston. The base is inscribed, in underglaze blue, “PHILADELFIA / the 23 April 1773 / 4.7” (fig. 10). This dates the basket to after the announced closing of the Bonnin and Morris factory in 1772, and therefore challenged its origin, although we know from successive newspaper advertisements for the sale of the factory in 1773 and 1774 that it had not sold or ceased production.[11] Woven through the interlocking circles is a leafy grapevine with molded clusters of grapes and the leaves and flowers of a rosebush—a decorative device previously undocumented on Bonnin and Morris porcelain.

Shortly after the 2007 Ceramics in America was published, geologist J. Victor Owen conducted an analysis of the paste in a sample taken from the basket. His preliminary findings concluded that the paste formula, unlike the previously analyzed Bonnin and Morris soft-paste porcelains, is not phosphatic but rather a lead-bearing, silicious-aluminous-calcic ware.[12] The reason for this discrepancy can be gleaned from newspaper advertisements placed by Bonnin and Morris. Early on in the production at the factory, the proprietors sought animal bones by the wagonloads—the source of the phosphatic material in their paste. On April 18, 1771, they announced that they were no longer accepting animal bones and, on January 2, 1772, began asking for large quantities of broken flint glass.[13] Flint glass was used to create a lead-bearing, non-phosphatic paste, presumably similar to that used for the 1773 basket.

Another mystery that needed to be solved is the meaning of the inscription on the bottom of the basket. Mary Gladue, my brilliant copy editor, noted that the date—“the 23 April 1773”—falls on St. George’s Day, an important English holiday celebrated in the eighteenth century in a fashion analogous to the way Christmas is today. The date also coincides with the first meeting of the newly founded Philadelphia chapter of the Society of the Sons of St. George, in Carpenters’ Hall.[14] Since then research by Nick Panes has found that the Society of the Sons of St. George was instrumental in supporting “mary Ball,” “the Widow of a China Manufacturer lately deceased.”[15] More research is under way to determine whether any members of that society were directly involved with the Philadelphia porcelain factory and, if so, whether the basket is some sort of commemorative token of that meeting. The association with St. George’s Day might explain the very unusual molded rose-and-grape decoration: the rose is among the more obvious emblems of Saint George and his commemoration, and the grapevine has long-standing religious connotations.

1773 Crolius Ink Stand

I first saw this wonderful inkstand in a Sotheby’s American auction catalog in June 1991 (fig. 11).[16] Although the complex form was a rare survival of eighteenth-century New York stoneware, it was the message on the base that carried the day for me (fig. 12). Inscribed and dated in bold script was “New York July 12, 1773 / William Crolius.” For stoneware scholars, the name Crolius is perhaps the most recognized of all the American potter families.

The heart-shaped inkstand is pierced with holes for pens, and the removable sander and inkpot are colored cobalt blue. The overall shape and decorative style are very similar to eighteenth-century Westerwald examples. On the bottom of the removable inkpot is the inscription “Tyler.” It is believed that William Crolius may have made the inkwell for Edmond Taylor, a cordwainer, for having attained the status of Burgher. Crolius himself became a Burgher in 1770. The pottery he founded in 1730 was operated by succeeding generations of Croliuses until it closed in 1887.

I had to make my case for the potential purchase before the other department curators, many of whom did not share my enthusiasm. Colonial Williamsburg had recently purchased the Bonnin and Morris basket discussed above. I thought these two iconic pieces, which were made within months of each other in the major cities of New York and Philadelphia, would provide the ultimate visual commentary on this period in eighteenth-century American ceramic history. I was already writing the museum labels in my head, with the heading “A Tale of Two Cities: The Story of 18th-Century American Ceramics.”

My pleas were heeded by Chief Curator Graham Hood, who arranged a special meeting with Colonial Williamsburg’s president to obtain permission to pursue the object at auction. Although a bid of $100,000 was approved, it fell far short of the final price of $147,000—a new record for American stoneware.[17] The object is a promised gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, perhaps the most appropriate home it could have.[18] Still, I take every opportunity when visiting New York to genuflect before it and ruefully think, “If only....”

Michelle Erickson’s Bonnin and Morris Pickle Stand

One of the great joys of exploring ceramics history is the collaboration that takes place among enthusiasts of the subject. Without question, working with master potter Michelle Erickson has done more to further my knowledge about ceramics than I ever thought possible. Combined with her own innate curiosity, artistic virtuosity, and dedication to reconstructing the kinetics of potters long deceased is her readiness to provide answers to ceramics mysteries. In preparation for the 2007 Ceramics in America, which was dedicated to the topic of Gousse Bonnin, George Anthony Morris, and the American China Manufactory of Philadelphia (1770–1772), I wondered aloud whether Michelle might take on the task of re-creating their most iconic (and most complicated) form: the tripatite pickle stand.[19]

I wasn’t serious, assuming it was way too much to ask given the time frame and the complexity of the object. But before I knew it, Michelle had taken up the challenge. Through the process of this re-creation, the ceramics world gained some wonderful insight into what most aficionados consider America’s most historical and iconic ceramic product.

The pickle stand, as produced by both the American China Manufactory and Bow, has three major components: the base, consisting of three open shell dishes or cups; a central vertical stem; and an open top cup. This vocabulary between the Philadelphia example and the Bow examples is virtually identical. The critical difference lies with the three open shells and, to a lesser extent, the top cup. The Bow and essentially all other English porcelain examples are molded from hand-sculpted models representing generalized bivalve shells. In significant contrast, the Bonnin and Morris shell dishes are taken directly from real scallop shells, a detail that proved to be one of the most diagnostic elements. Michelle can take full credit for determining that the most likely candidate for the scallop was Pecten maximus (Great Scallop). The range of Pecten maximus includes all of the British coastline and beyond, from Norway to Spain. The species was an important food source for eighteenth-century American, British, and European inhabitants. Today these shells are marketed as Irish baking dishes and are used widely in the culinary industry to cook and serve seafood.

I had initially envisioned a two-dimensional diagram of the pickle stand in the journal. Instead, I took full advantage of Michelle’s brilliant research combined with Gavin Ashworth’s photographic talents to produce the three-dimensional “exploded” view of the pickle stand shown in figure 13. The didactic value of this graphic speaks volumes and is surpassed only by the mastery required to create the fully assembled version shown in figure 14. I can say without reservation that this project best illustrates the spirit and intent of Ceramics in America’s mission statement.

North Devon Slipware Cradle

Perhaps no greater example of the disparity between archaeological and decorative arts collections exists than the story of seventeenth-century North Devon slipware. Examples of the plain North Devon, dating from the late sixteenth century, show up in the earliest sites of the Chesapeake region. The very distinctive gravel-tempered variety of North Devon is also present by the early seventeenth century. Early examples of a sgraffito-decorated variety of North Devon slipware appear by the second quarter of the seventeenth century in a number of archaeological sites, and by the 1660s North Devon decorated slipware is nearly ubiquitous in Chesapeake archaeological contexts.[20] Although the North Devon industry continued to export the gravel-tempered variety throughout the eighteenth century, sgraffito-decorated slipware wares are rarely found in American archaeological contexts after 1700.

The newly recorded North Devon cradle (figs. 15, 16) is inscribed with the date “[16]98,” a bust-length profile of a woman, and the initials “SD”; the side panels and bonnet are decorated with flower heads typical of seventeenth-century North Devon decorative motifs.[21] Made as a special commission to commemorate the birth of a child, this is the only seventeenth-century North Devon slipware cradle known to survive. It must have been made by the anonymous maker of the surviving 1698 harvest jug illustrated by C. Malcolm Watkins in his seminal 1960 publication and now in the collection of the Winterthur Museum (1964.0025).[22]

The true magnitude of the cradle’s rarity can be gauged in light of shipping records from the North Devon pottery industry. In her comprehensive study of seventeenth-century North Devon, Alison Grant examined the port books for the potting towns of Bideford and Barnstaple from 1671 through 1699. She estimated an average annual output of nearly half a million parcels of utilitarian earthenware pottery for the North Devon industry.[23] While these numbers included both plain and decorated wares, it is not unreasonable to assume that several million individual examples of sgraffito slipware may have been produced during this period. In stark contrast, a search of published sources and museum collections suggests that fewer than a dozen seventeenth-century sgraffito-decorated objects have survived.

Although later eighteenth- and nineteenth-century North Devon sgraffito-decorated harvest jugs can be found in many major ceramic collections, few curators have any firsthand experience with such seventeenth-century pieces. Archaeologists excavating seventeenth-century British colonial sites, on the other hand, are intimately familiar with these earthenwares. Will this divide ever be bridged?

James Morgan Stoneware Mug

I have nurtured a number of recurring ceramic fantasies about discovering some heretofore unknown American ceramic treasure. I once had a vivid dream of finding a pair of Bonnin and Morris vases on a mantel in Virginia’s Executive Mansion, but these objects failed to materialize. A more frequent daydream had been finding an eighteenth-century example of American stoneware in the Westerwald style of Germany.

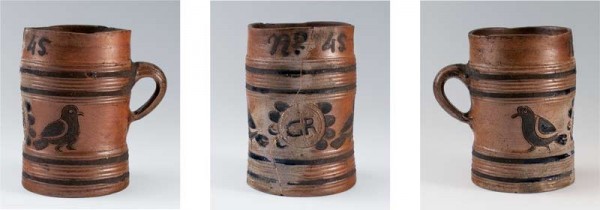

For nearly two centuries German stoneware imports were used in America, and the eighteenth-century American landscape is littered with broken fragments of these highly decorative yet utilitarian wares. The most distinctive of these were mugs and jugs that bore the “GR” cipher, which signified the consecutive reigns of the British monarchs George I, II, and III. German immigrant potters working in Manhattan and New Jersey made an Americanized version of these Westerwald products beginning in the 1750s. In the 2008 Ceramics in America, Arthur Goldberg and Peter Warren presented evidence for eighteenth-century stoneware production in New Jersey. Meta Janowitz reviewed the archaeological evidence for pottery production in Manhattan by the Crolius and Remmey families. In both articles, evidence for the production of stoneware in the Westerwald style was presented, including the use of “GR” medallions, although no surviving American “GR” vessels have been recorded.[24]

Raised on Walt Disney, I believe that dreams sometimes come true. Nevertheless, I was stunned when I saw the online listing from a major New England auction house for a “Cobalt-decorated Salt-glazed Teapot and Mug, Germany, 18th century” (figs. 17, 18). The description did not offer much information to help guide the potential buyer, but the photograph spoke a thousand words: the stoneware mug carried the inscription “No. 45” and a “GR” medallion. Those acquainted with Anglo-American political history might know that this emblem referred to John Wilkes, the author of The North Briton No. 45, published on April 23, 1763, who championed the cause of liberty and questioned the king’s authority. Wilkes was adopted by American colonists as an avatar of their own struggle for independence, and the “No. 45” emblem appeared as a rallying cry on all sorts of items, from punch bowls to coat buttons.[25]

When I attended the auction preview, my examination confirmed that the teapot was indeed an eighteenth-century Westerwald product, but the mug was made by James Morgan of New Jersey, 1775–1785. To my knowledge it is the only extant American example with this “GR” medallion. The addition of the Wilkes slogan on this pre-Revolutionary American-made vessel sent its historical significance through the roof. These factors were enhanced by its provenance—it had been in the collection of famed nineteenth-century Hartford, Connecticut, collector Henry Wood Erving, a colleague and mentor of Wallace Nutting.

The exhilarating experience of successfully bidding (via telephone) for this treasure remains indelibly etched in my psyche. Although there was some spirited competition, it was apparent that no one else had recognized the rarity and importance of this American stoneware mug, which now resides in a private collection.

Now where could those Bonnin and Morris vases be?

Carolina Creamware

The story of American ceramics is one of immigration, adaptation, and innovation. Soon after the sixteenth-century Spanish settlement of Santa Elena near present-day South Carolina was established, potters began producing sophisticated earthenware forms using the local clays. In the 1620s, in the first permanent English settlement at Jamestown, potters were re-creating London earthenware forms using native material. Later in the seventeenth century, several earthenware potters were plying their trade in the mid-Atlantic region. The common thread among these early wares is that no examples have survived aboveground as antiques; we know of their physical existence only through archaeology.

In 2009 I was asked to be part of a team project that reevaluated the ceramics made in the eighteenth-century Moravian settlements of Bethabara and Salem, North Carolina. The Moravians made utilitarian earthenwares as well as highly ornamented slipware dishes following Germanic forms and decoration. It is intriguing that the North Carolina Moravian potters were among the first to make eighteenth-century Staffordshire-style earthenwares.

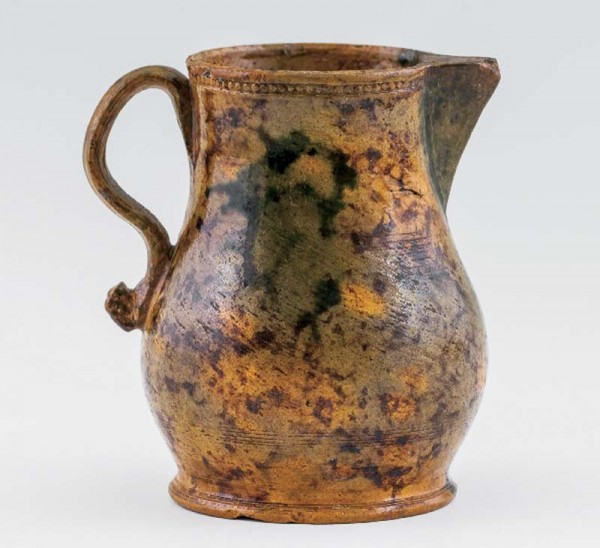

The story of the so-called Carolina Creamware begins with Staffordshire potter John Bartlam’s porcelain and earthenware manufactory in Charleston, South Carolina, started circa 1765.[26] Bartlam produced a thoroughly competent range of wares and forms, which have been documented through archaeological excavation by Stanley South. Like many potters of his day, Bartlam incurred numerous financial problems. By 1772 his Charleston factory had succumbed to economic failure and he relocated to Camden, South Carolina, where he probably continued to work until his death in 1781. After the Charleston factory closing, one of Bartlam’s skilled workers, a William Ellis, joined the Moravian settlement of Salem in North Carolina.[27]

Our knowledge of Ellis’s activities at Salem comes from the carefully maintained documents of the Moravian church, which record the arrival of a “stranger journeyman potter by the name of Ellis” in December 1773.[28] From that date until his departure in May 1774, Ellis was able to transmit some of the key production techniques used in the making of English creamware to the Salem potters. We know from the vast historical records of the Moravian community that the “fine ware” techniques Ellis proffered were particularly appealing to master potter Rudolph Christ.

Archaeological excavations have turned up fragmentary ceramic evidence for Ellis’s contribution to introducing Staffordshire ceramic technology to the Moravian potters.[29] One particularly evocative archaeological specimen is the rouletted base of a small earthenware mug adhered to its kiln stand (fig. 19 left). This pint mug retains the crispness of the roulette’s impressions, captured in the once soft clay body. Although it is a waster, I find this fragment as evocative and appealing as any ancient Greek or Roman fragment of sculpture. A more complete English-style tankard (fig. 19 right) fully reflects the attempts to implement, in the backcountry of North Carolina, the technology of the great Staffordshire factories. If I had to pick one object to forever grace a plinth in my home it would be the mug base fragment, which embodies one of the greatest stories in American ceramic history.

Epilogue

As I was writing this final entry, the small cream jug illustrated in figure 20 came up for sale at a North Carolina auction house, cataloged as an example of Moravian fineware. I purchased the jug in the firm belief that it is a product of John Bartlam or one of his workmen, perhaps William Ellis. Research is ongoing; stay tuned for the next installment on this significant piece of American ceramic history.

ROBERT HUNTER has more than thirty years of professional experience in prehistoric and historical archaeology. He earned a master’s in anthropology from The College of William and Mary, where he took additional coursework at the doctoral level in American Studies. He was the founding director of the college’s Center for Archaeological Research. He also served as assistant curator of ceramics and glass in the Department of Collections at Colonial Williamsburg. Until recently, he was a partner in Period Designs, an innovative firm specializing in the reproduction of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century decorative arts.

Mr. Hunter has been editor of Ceramics in America since its inception in 2001, and has written for a variety of other publications, among them Antiques, The Catalogue of Antiques & Fine Art, New England Antiques Journal, Early American Life, Ceramic Review, Studio Potter, Ceramics: Art and Perception, Pottery Making Illustrated, Kerameiki Techni, and the Journal of Archaeological Science. He lectures widely and participates in the New York Ceramics Fair every January.

He received the 2007 Award of Merit from the Society for Historical Archaeology, is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and is a board member of the American Ceramic Circle and CFile.

Ivor Noël Hume, “Pearlware: Forgotten Milestone of English Ceramic History,” Antiques 95, no. 3 (1969): 390–97.

Ivor Noël Hume, A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970).

Lisa S. McAllister, Collector’s Guide to Feather Edge Ware: Identification & Values (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 2001).

George L. Miller and Robert R. Hunter, “English Shell-Edged Earthenware: Alias Leeds Ware, Alias Feather Edge,” in The Consumer Revolution in 18th Century English Pottery, Proceedings of the 35th Annual Wedgwood International Seminar ([Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Institute of Art, 1990]), pp. 107–36; George L. Miller and Robert Hunter, “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 135–61; Robert Hunter and George L. Miller, “Suitable for Framing—Decorated Shell-Edge Earthenware,” Early American Life 40, no. 4 (August 2009): 8–19.

Robert R. Hunter Jr. and George L. Miller, “English Shell-Edged Earthenware,” Antiques 145 (March 1994): 432–43.

John E. Kille, “Distinguishing Marks and Flowering Designs: Baltimore’s Utilitarian Stoneware Industry,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 93–131.

Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825: Journal of a Voyage to the United States, translated by Alan R. Hoffman (Manchester, N.H.: Lafayette Press, 2006).

Donald Carpentier and Jonathan Rickard, “Slip Decoration in the Age of Industrialization,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 115–34.

Diana Edwards, Neale Pottery and Porcelain: Its Predecessors and Successors, 1763–1820 (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1987), p. 189.

Joyce Epps, “Two Neale and Wilson Porcelain Tureens,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 18, pt. 1 (2002): 29–32.

Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling, “Bonnin and Morris Revisited,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), p. 191. The factory’s May 3, 1773, auction notice in the Pennsylvania Chronicle claimed that the works were still operational. The Stradlings have postulated that the basket was made immediately before the auction of the manufactory’s assets, perhaps to publicize the abilities of an unnamed German potter available to “undertake the management, upon reasonable terms, either in partnership or otherwise....”

J. Victor Owen and Robert Hunter, “‘Too Little, Too Late’: The Geochemistry of a 1773 Philadelphia Openwork Porcelain Basket,” Journal of Archaeological Science 36, no. 2 (2009): 333–42.

Alfred Coxe Prime, comp., The Arts & Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland, and South Carolina, 1721–1785/Gleanings from Newspapers (Topsfield, Mass.: Walpole Society, 1929), pp. 117–19.

www.ushistory.org/carpentershall/history/timeline.htm.

Nicholas Panes, “Mr Ball the English Potter and the American China Manufactory,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 20, pt. 3 (2009): 633–45.

“Fine Americana,” auction catalog, Sotheby’s, New York, June 26–27, 1991, sale 6201, lot 211.

Lita Solis-Cohen, “Inkwell, Historic Gold Box Set Records at Sotheby’s Auction,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1991.

Karl H. Pass, “William Crolius Heart Shaped Inkstand Gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Maine Antique Digest (April 2013): 11-A.

Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Making a Bonnin and Morris Pickle Stand,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 141–64.

Thomas F. Higgins III, C. M. Downing, and D. W. Linebaugh, Traces of Historic Kecoughtan: Archaeology at a 17th Century Plantation; Data Recovery at Site 44HT44, Associated with the Proposed Pentran Bus Parking Lot Project, City of Hampton, Virginia, William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research Technical Report Series 28 (Williamsburg, Va., 1999); Merry Abbitt Outlaw, “Scratched in Clay: Seventeenth-Century North Devon Slipware at Jamestown, Virginia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 17–38.

Robert Hunter, “17th-Century North Devon Slipware and the ‘Keep Me’ Factor,” in A Glorious Empire: Archaeology and the Tudor-Stuart Atlantic World; Essays in Honor of Ivor Noël Hume, edited by Eric C. Klingelhöfer (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2013), pp. 169–72.

C. Malcolm Watkins, North Devon Pottery and Its Export to America in the 17th Century, United States National Museum Bulletin 225 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1960); Leslie B. Grigsby, “English Slipware in Colonial America,” in This Blessed Plot, This Earth: English Pottery Studies in Honour of Jonathan Horne, edited by Amanda Dunsmore (London: Paul Holberton, 2011), pp. 150–58.

Alison Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century (Exeter, Eng.: University of Exeter Press, 1983), pp. 72–75.

These sherds are pictured in Arthur F. Goldberg, Peter Warwick, and Leslie Warwick, “The Eighteenth-Century New Jersey Stoneware Potteries of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple Family,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 2–40; and Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground,” in ibid., pp. 41–66.

. Jack Lynch, “Lord Mayor Wilkes: Liberty and No. 45,” Colonial Williamsburg (Summer 2003): 51–55.

Stanley South, John Bartlam: Staffordshire in Carolina, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology Research Manuscript Series 231 (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 2004); Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “John Bartlam, Who Established ‘new Pottworks in South Carolina’ and Became the First Successful Creamware Potter in America,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (1991): 1–66; Stanley South, The Search for John Bartlam at Cain Hoy: America’s First Creamware Potter, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology Research Manuscript Series 219 (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1993).

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam: The History of William Ellis of Hanley,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (1991): 80–102.

Ibid., p. 82.

Stanley South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999).