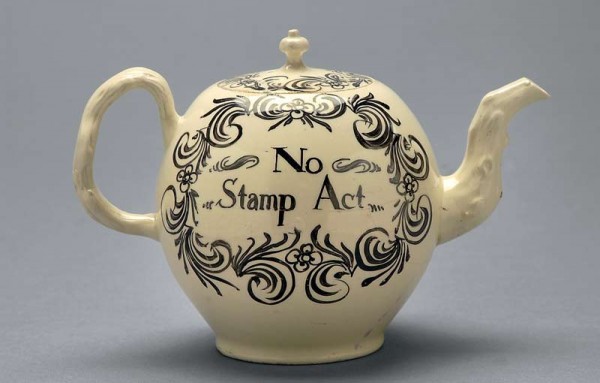

“No Stamp Act” teapot, possibly Cockpit Hill Factory, Derby, England, 1766–1770. Creamware. H. 4 1/4". Marks, inscribed on sides: “No / Stamp Act”; “America; Liberty / Restored” (All objects courtesy, National Museum of American History. Purchase, Jackson Fund; 2006.0229.01.)

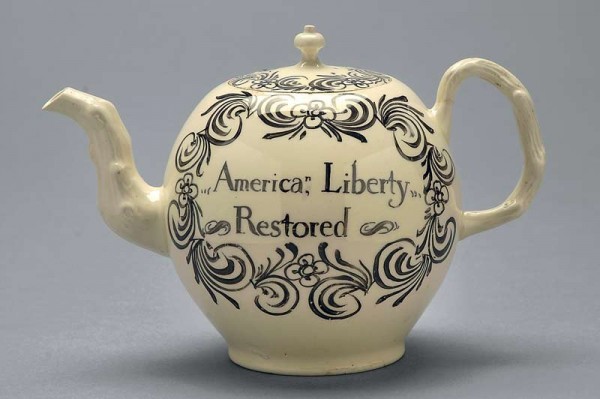

Reverse of the teapot illustrated in fig. 1.

Storage jar, Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1793–1812. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 3/4". Mark: “COMMERAWS [S in reverse] / STONEWARE [N in reverse]” (Gift of John Paul Remensnyder; 1977.0803.140.)

Pickle stand, American China Manufactory (Bonnin & Morris), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 5 1/2". (Purchase, Barra Foundation; 70.597.)

Detail of the pickle stand illustrated in fig. 4.

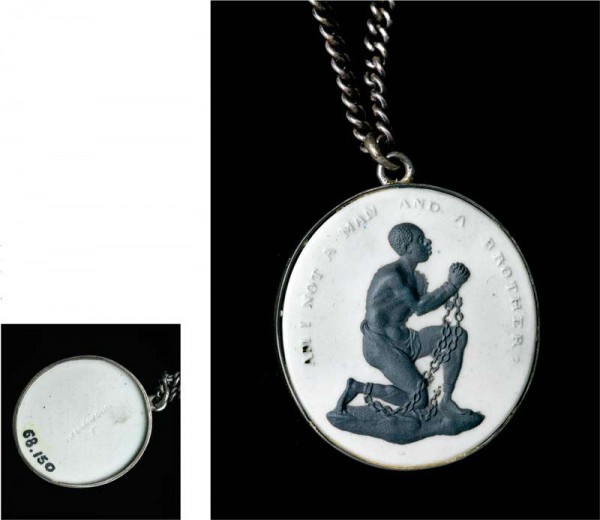

“AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?” medallion, Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Staffordshire, England, after 1787. Refined stoneware. H. 1 1/8", W. 1 1/4". (Gift of Lloyd E. Hawes; 68.150.)

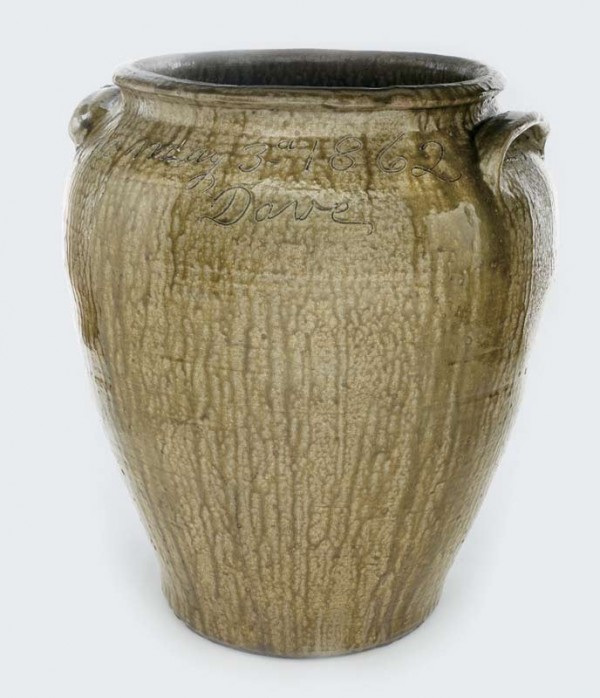

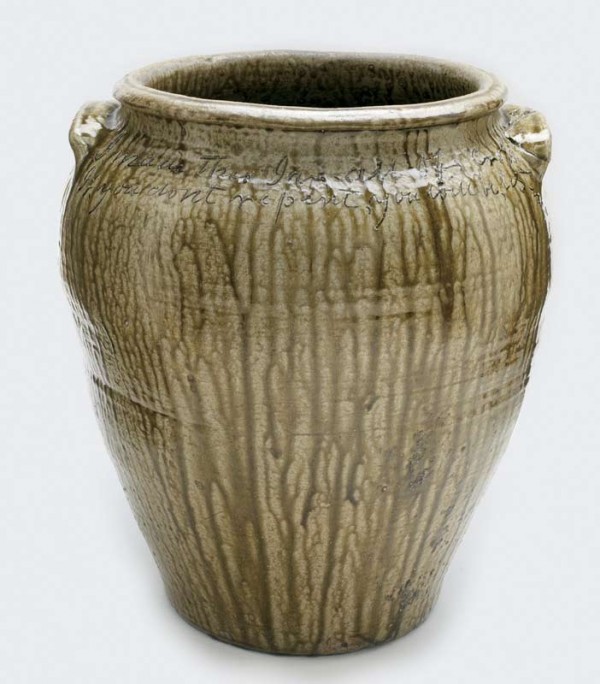

Poem jar, David Drake, Lewis Miles Plantation, Edgefield area, South Carolina, 1862. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 20 1/2". Mark, inscribed on shoulder: “May 3d 1862 / Dave”; “I made this jar all of cross, / If you dont repent, you will be lost” (Purchase; 1996.0344.01.)

Reverse of the jar illustrated in fig. 7.

Coffee cup used by Abraham Lincoln, made in France, decorated by E. V. Haughwout & Company, New York, New York, 1861. Porcelain. H. 3 1/4". (Gift from Lincoln Isham; 219098.09.)

Side view of the cup illustrated in fig. 9.

Figure group, Union Porcelain Works, Greenpoint, New York, 1880s. Porcelain. H. 11 1/8". (Gift of Mrs. Franklin Chace; 75.122.)

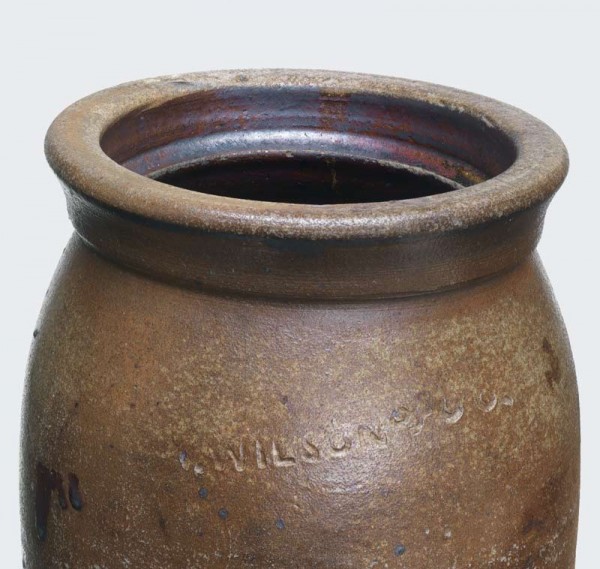

Jar, H. Wilson & Company, Gaudalupe County, Texas, 1869–1884. Stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Mark, inscribed on shoulder: “H. WILSON & C” (Purchase, Jackson Fund; 1993.0088.01.)

Detail showing the mark on the jar illustrated in fig. 12.

Umbrella stand, George E. Ohr, Biloxi, Mississippi, 1900. Earthenware. H. 14 11/16". (Purchase; 78.4.)

Detail of the umbrella stand illustrated in fig. 14.

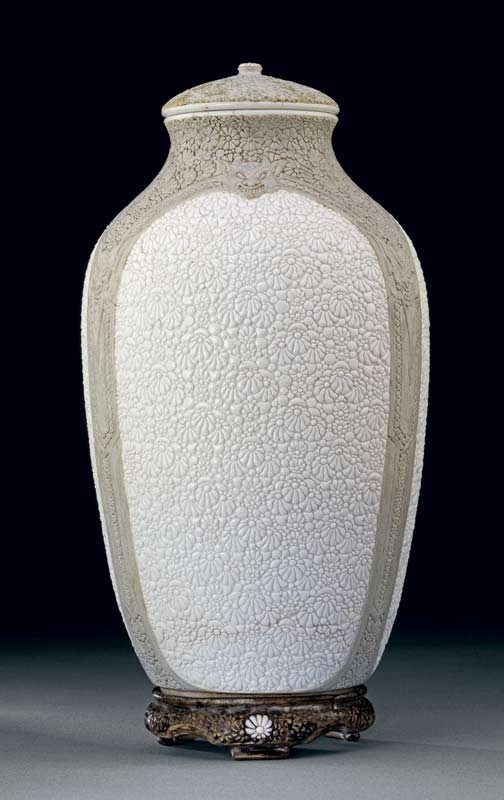

Vase with lid, Adelaide Alsop Robineau, University City, Missouri, 1910. Porcelain. H. 9 1/4". (Gift of Priscilla R. Kelley; 1979.0104.01.)

Little could James Smithson have imagined what would become of his 1829 bequest of more than $500,000 to the United States. The illegitimate child of a British nobleman, Smithson had never visited the young nation but left instructions that his fortune be used to establish an American institution in his name for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.[1] The Smithsonian Institution, founded in 1846, is now the largest museum and research complex in the world—and growing. (To paraphrase Ernest Hemingway’s famous quip about cats, one museum just leads to another.) This year, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History celebrates its fiftieth anniversary. What better time to highlight some of the museum’s ceramic treasures?

The National Museum of American History houses more than three million artifacts and documents, spread among seven different curatorial divisions. As the curator of the Ceramics and Glass collection in the Division of Home and Community Life, I am responsible for more than thirty-five thousand pieces of pottery, porcelain, and tile for household, decorative, and industrial use—much of it made, used, and marketed in the United States from about 1600 to the present. The ceramics collection is particularly strong in utilitarian earthenware and stoneware from the Northeast, American art pottery and tiles, English wares made for the American market, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European porcelain, and historical archaeology materials from the colonial period onward.

Much of the collection was acquired by the Smithsonian long before anyone conceived of the American History Museum. A train pulling sixty boxcars brought countless artifacts from around the world to the Smithsonian from Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition of 1876.[2] In addition, such major collectors as Marcus Benjamin, Alfred Duane Pell, and Hans Syz donated large collections of American, British, and European ceramics to the Smithsonian in the first half of the twentieth century.[3] Although donors Ellouise Baker Larsen and Robert McCauley interpreted and published their collections of British pottery within the context of U.S. history, for most of its existence the museum’s ceramics collection predominantly represented the decorative arts of the well-to-do in both Europe and the United States.[4] Over the past forty years, though, the museum’s ceramics curators have strived to collect artifacts and reinterpret standing collections in order to better tell stories about the diversity and complexity of the American experience. When we collect a piece of Homer Laughlin Fiesta ware now, we are as interested in the story of the family who owned it as in the piece itself—sometimes more so: whether that family was wealthy and used it at their lake home in the summer, or scrimped and saved to acquire a set, piece by piece, to use only for holidays and celebrations.

I have worked on the curatorial staff at the museum for more than twenty-five years, for the last ten as the sole curator of the Ceramics and Glass collection. Although I collect fewer objects than did the curators of old, I want to be sure each and every acquisition tells a story that needs telling. The museum’s ceramic collection is broad and deep, but there is still a long way to go before it conveys a truly inclusive understanding of America’s ceramic history. My next mission is to collect ceramics that help interpret the experiences of immigrants in America today as part of a larger museum initiative to document how people from all over the world have met, mingled, and formed the culture of the United States.

This museum’s mission, to explore the richness and complexity of American history in order to understand the past and make sense of the present, was high on my list of criteria as I struggled to winnow down my list of favorite objects. Each of the pieces I chose helps the museum tell an important story about the United States, this tested but great experiment in freedom, possibility, and opportunity. Only three of these artifacts have been collected during my time here—the “No Stamp Act” teapot and the stoneware jars made by David Drake and Hiram Wilson—which speaks to the wise collecting done by former ceramics curators. The Lincoln teacup is held by the Division of Political History, the curatorial unit responsible for all things presidential at the museum, and a rich source for ceramics associated with American politics and diplomacy.

“No Stamp Act” Teapot

The National Museum of American History has approximately one thousand examples of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century English earthenware decorated for the American market, making it one of the most comprehensive public collections of its kind in the United States. The collection illustrates the appeal of chauvinism and patriotism to American consumers during the colonial era and the early years of the republic and serves as evidence of the importance of Anglo-American trade to the emerging nation.

I purchased this revolutionary little creamware teapot (figs. 1, 2) at auction in 2006. Formerly owned by William H. Guthman, it was made in England between 1766 and 1770, possibly by the Cockpit Hill Factory, in Derby, England.[5] With its enameled slogan “No Stamp Act,” the object references the Stamp Act and ensuing Stamp Act Crisis, which were crucial to the shaping of the political landscape in the colonies. The Stamp Act, passed by the British Parliament on March 22, 1765, required American colonists to pay a tax on all printed materials, from documents to playing cards. This was the first direct tax on the American colonies and provoked an immediate and violent response throughout the colonies. Our teapot was made soon after the 1766 repeal of that hated act.

This teapot also documents the intersections between home and public life. In the pre-Revolutionary era, the fashionable social custom of taking tea was fast becoming politicized. In her 1961 monograph on it, Rodris Roth points to the importance of tea drinking to “the social life and traditions of the Americans,” as well as to the political, historical, and economic importance that tea holds in U.S. history.[6] By the time this particular teapot was made, tea was very popular in the colonies and accessible to most Americans. The importance of tea and tea drinking to colonial society is underscored by the controversy surrounding it: in 1767 merchants and citizens protested the Townshend Act, which had imposed a duty on tea (as well as other commodities), and in 1773 the so-called Boston Tea Party became a defining moment in American history.

Thomas Commeraw Stoneware

Given the size of the Smithsonian’s ceramics collection, it can be hard to be familiar with every single piece. Nevertheless, I thought I had a pretty good idea of what was in the collection of about 150 pieces of American stoneware donated in the 1970s by chemist and collector John Paul Remensnyder. I was particularly interested in his early New York City wares made by the Remmey, Crolius, Morgan, and Commeraw potteries (fig. 3), and I was fascinated by the old place-names, such as Manhattan-Wells and Corlears Hook. I had read everything in our library about these potters. Yet, pots are sometimes full of surprises.

A number of years ago I asked an intern to research and photograph some examples of our New York stoneware in order to upload it to the Smithsonian’s online database, collections.si.edu. I was flabbergasted when she mentioned that she had found Brandt Zipp’s website in which he explained that Thomas Commeraw was not a white potter of French background, as everyone had assumed, but a free black man making stoneware in New York’s Lower East Side in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.[7] It was almost too incredible to be true.

We had a handful of Edgefield-area face vessels in the collection and by this time had also purchased two David Drake pieces (discussed below). As far as I knew, that was the extent of our African-American–made pottery, but with a simple click on a website we discovered we had pieces made by a prominent member of the African Church in the City of New York who took part in pro-abolition services at his church in 1809, eighteen years before slavery was legally abolished in New York State.[8] It was rewarding to discover the truth about Thomas Commeraw and to see, two hundred years later, that his remarkable story is finally beginning to be told.

Bonnin and Morris Pickle Stand

While colonial Americans had access to the raw materials needed to make porcelain, they lacked the skilled talent required to run a successful porcelain manufactory. A few ambitious men were inspired to establish American industries that would compete with foreign manufacturers. The most successful undertaking was the American China Manufactory, founded in 1770 and run by Englishman Gousse Bonnin and Philadelphian George Anthony Morris (figs. 4, 5).[9] Intending to take advantage of a late-1760s embargo on importing British-made goods, the hopeful partners built a ceramics factory and began experimenting with making fine porcelain in 1770. They announced success in January 1771, but labor disputes, difficulties in obtaining clay, and the end of the trade embargo doomed the company. It supposedly closed the next year, whereupon Bonnin returned to England. Seven years later the factory buildings were put into service producing brass cannons for the Continental Army.[10]

This is the one piece in the ceramics collection that always gives me pause when I handle it, in part because it is so delicate, and in part because it is one of only twenty recorded extant pieces from this factory.[11] What really makes it special to me, though, is how unlikely it was to have existed at all. Bonnin and Morris established their factory against all odds and it is miraculous that they successfully produced porcelain this fine, let alone that any of it survives. The factory is long gone, but it is our good fortune that twenty pieces of fragile porcelain survive to remind us of the eternal optimism and ingenuity of the American spirit.

Wedgwood Anti-Slavery Medallion

“AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?” So reads the inscription on this oval white-jasper medallion featuring a black basalt relief figure of an enslaved man, kneeling and in chains (fig. 6). Most likely designed by sculptor Henry Webber and modeled by William Hackwood, this medallion was first produced in 1787 by antislavery campaigner Josiah Wedgwood for the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, founded in the same year. British men and women sympathetic to the abolitionist cause wore these medallions on their jewelry, shoes, clothing, and snuffboxes to express their opposition to the transatlantic slave trade.

In 1788 Wedgwood sent some of these medallions to Benjamin Franklin, who was then the president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in America. Wedgwood hoped that the medallions would “acquaint [Franklin with a subject that] is daily more and more taking the possession of men’s minds on this side of the Atlantic as well as with you.”[12] Franklin responded to Wedgwood, “I am persuaded [the medallion] may have an Effect equal to that of the best written Pamphlet in procuring favour to those oppressed people.”[13] Neither Franklin, who died in 1790, nor Wedgwood, who died in 1795, lived to see those wishes fulfilled. The British Parliament outlawed the slave trade in 1807 and abolished slavery in all British colonies in 1833. The United States ended legal importation of slaves in 1808, but it took civil war and the ratification of the thirteenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865 to legally abolish slavery.

This medallion, which was accessioned in 1968, is part of a collection of nearly seventy pieces of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English ceramics donated by Dr. and Mrs. Lloyd E. Hawes, avid and knowledgeable collectors. Dr. Hawes was the founding president of the American Ceramic Circle.

Dave Poem Jar

When I joined the museum’s Ceramics and Glass staff in 1989, the collection, like many of the museum’s curatorial units at the time, was particularly strong in areas reflecting the lifestyles and work of English and European Americans. We had a handful of stoneware face vessels attributed to enslaved potters in the Edgefield, South Carolina, area, but no other ceramics known to have been made or used by African-Americans. Fate, in the form of preeminent collectors Tony and Marie Shank, enabled us to change this. When Tony called in 1996 to say that he was offering to sell his outstanding collection of Edgefield pottery to selected museums before opening the sale to private collectors, we jumped at the chance to finally get a David Drake piece. I was able to purchase five examples of the distinctive alkaline-glazed Edgefield stoneware, including two important Dave pieces: an 1859 jar signed “Dave and Mark” and this beautifully glazed 1862 poem jar (figs. 7, 8).

Dave was a master potter, regularly producing massive storage jars and jugs that required exceptional skill and strength. About twenty surviving pieces are inscribed with his two-line poems—wonderful and sometimes cryptic ruminations on topics as diverse as pots, love, money, spirituality, life as a slave, and the afterlife.[14] The poems reflect Dave’s intelligence, creativity, and wit.

The inscription on this piece, “I made this jar all of cross, If you dont repent you will be lost” may refer to Peter’s speech at Pentecost in the temple of Herod in Jerusalem.[15] It is certainly material evidence of Dave’s familiarity with biblical text, his literacy in the face of harsh penalties against slaves learning to read and write, and his desire to communicate his worth both as a master craftsman and as a man. Dave’s words emphasize the importance of religion and the afterlife in the daily life of many slaves. Folklore historian John Michael Vlach highlighted this jar in The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, conjecturing that its “highly poignant verse” reflects “Dave’s combined feelings about slavery and religion.”[16]

White House Coffee Cup

During the drive he was so gay, that I said to him, laughingly, “Dear Husband, you almost startle me by your great cheerfulness,” he replied, “and well I may feel so, Mary, I consider this day, the war, has come to a close”—and then added, “We must both, be more cheerful in the future—between the war & the loss of our darling Willie—we have both, been very miserable.”

—Mary Lincoln, recounting the carriage ride they took the afternoon before attending Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865[17]

The Civil War had ended after four long and bloody years. It was time to celebrate victory and unify and rebuild the nation. On Good Friday, April 14, President Lincoln decided to spend a relaxing evening at Ford’s Theatre watching the popular play Our American Cousin. After dressing for the evening the president left this porcelain cup on a White House windowsill (figs. 9, 10). A servant set it aside as a relic of that tragic night. Years later Captain D. W. Taylor presented the cup to Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s eldest son, who kept it as a family heirloom. Lincoln Isham, a great-grandson of Abraham Lincoln, donated the cup to the Smithsonian in 1958.

Artifacts can serve as touchstones to the past. Without its story, this is a fine but unremarkable coffee cup. It becomes more interesting when we realize that it is part of the Lincoln White House china selected by Mary Todd Lincoln in 1861. But as one of the last objects handled by one of the country’s greatest presidents before he was murdered, it takes on special meaning while reminding us of the humanity of such a mythical-seeming historical figure. We can imagine Lincoln taking that last sip before distractedly placing the cup on a windowsill. It is not surprising that this memento took on meaning for Lincoln’s family, or that it has meaning to us today. But that a servant noticed and remembered the president putting the cup down is a testament to the import given to everything Lincoln did at the height of his success and power.

Union Porcelain Works Figure Group

I consider this piece to be one of the most significant, if most perplexing, in the collection (fig. 11). Designed in the early 1880s by Karl L. H. Müller at Union Porcelain Works, Greenpoint (now part of Brooklyn), New York, it was donated to the Smithsonian in 1975 by a descendant of Thomas C. Smith, the firm’s founder. The parian figure group depicts a white boy, wearing a liberty cap, resting his hand on the back of a young black male as both peer over the edge of an eagle’s nest at a Chinese figure who appears to be struggling to make his way into the nest. A similar piece in the Brooklyn Museum bears the inscription “Chinese Argument,” although ours is untitled.[18] The Smithsonian’s example was loaned to the exhibition “After the Chinese Taste: China’s Influence in America, 1739–1930” at the Peabody Essex Museum in 1985.[19] The Peabody Essex has since acquired another unmarked example for its collection.

In the late 1800s black Americans gained citizenship and the vote, while immigrants from Europe and Asia came to the country in record numbers. As these minorities strove for economic prosperity and social justice, some white Americans reacted to the rapidly changing social order with apprehension and hostility. Although there were a few thousand Chinese in the United States before the Civil War, the need for inexpensive labor to build the railroads contributed to a massive influx of Chinese laborers in the late 1860s and 1870s. Growing nativism and a perceived competition for jobs led to a backlash against the Chinese that resulted in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which severely curtailed Chinese immigration to the United States for more than fifty years and disallowed citizenship to those already in the country.

This piece was certainly made in response to the question of what to do about the Chinese in America, although its message is ambiguous. Is it sympathetic toward the foreigner working hard to get into the nest, or does it imply that there is no more room? Either way, the relationship between the three figures in this statue powerfully captures the tension of its day.

H. Wilson Pottery Jar

When Georgeanna Greer’s ceramic collection came up at auction in 1993, I was on a long-planned ski vacation in the Rockies.[20] I was so focused on getting this piece (figs. 12, 13) that I would take a run down the mountain, rush to the lodge to call the auction house for an update, take another run, then head back to the lodge (needless to say, this was in the days before we all had cell phones!). A humble-looking piece, this jar helps tell the story of the way one group of freed slaves was able to use skills learned as enslaved potters to fashion a new life for themselves and portrays the complexity of the slave experience in America.

Hiram, James, and Wallace Wilson (they probably were not blood relations but adopted the name of their owner) were taken as slaves to Guadalupe County, Texas, in 1857 by their master, John Wilson.[21] There they were trained in the alkaline-glazed tradition in Wilson’s new stoneware pottery. After the Civil War, the three freedmen founded the H. Wilson Company nearby. Upon establishing their own pottery, the men eagerly adopted new stoneware technologies and began to employ the more readily available slip glaze used on the interior of this jar.

Hiram used his success at the pottery as a springboard to become an important secular and religious leader among the freed black population of Guadalupe County. He attended Bishop College in Marshall, Texas, and founded the black township of Capote in 1872, allowing freed black families to give up sharecropping and to acquire and work their own farmland.

George Ohr Umbrella Stand

Although George Ohr dedicated this wonderful umbrella stand to the Smithsonian in 1900 (figs. 14, 15), it did not make its way into the collection until 1978, when the institution purchased it from James and Miriam Carpenter, the couple responsible for the rediscovery of thousands of Ohr pieces in a garage in Biloxi, Mississippi.[22] This piece is covered in writing that Ohr scratched into the clay with a pin, including a long letter addressed to him from his friend Henry Pfluger, a former resident of Biloxi who said he had been driven away for expressing his belief that the town needed a fearless newspaper. I could go on about what Ohr was expressing with this umbrella stand, but he does it so much better!

[Text around stand below rim] The Somebody (that used to be) that “made this Pot” Was born at Biloxi, Miss—July 12. 1857 (on Sunday 10.AM sharp) and is and was G. E. Ohr....[Incised in script on base] Biloxi. Miss. / Dec - 18 - 1900 / To the Smithsonian Washington / As Kind Words, and deeds never Die Sutch words and deeds are “Fire-Waters” Acid and “Time proof.” When recorded on Mother Earth—or clay—This is an empty Jar. Just like the world, “solid in itself” yet. full on the surface! Deed and thoughts live But the instigators are shadows—fade and disapear / when the Sun goes DOWN Mary had a little lamb Pot-Ohr-E-George has (HAD) a little Pottery “Now” where is the Boy that stood in the Burning Deck. “This Pot is here,” and I am the Potter Who was G. E. Ohr.[23]

Adelaid Alsop Robineau “Pastoral” Vase

The National Museum of American History has a large collection of American art pottery, much of it acquired in the late 1800s and early 1900s either directly from the manufacturer or from a few major donors.[24] The collection is wonderfully representative of the range of art wares made at the time and boasts of a few spectacular pieces, including this highly ornamented, carved, and pâte-sur-pâte porcelain vase made by Adelaide Alsop Robineau in 1910 (fig. 16).

Leaning in long before Sheryl Sandberg, CEO of Facebook, wrote the book, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, Robineau was astonishingly creative and productive.[25] She was a china painter and teacher as well as the founding editor of Keramic Studio, a long-lived and influential publication aimed at china painters. Although she bore three children between 1900 and 1906, Robineau managed to find time to learn how to work with clay in 1902. She was so talented and successful that her porcelain was exhibited at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and Tiffany & Company began selling her pieces in 1905.

Robineau made this “Pastoral” vase for her daughter, Priscilla, during her eighteen-month tenure at the University City Pottery in University City, Missouri. The pottery was an adjunct of the Peoples University, founded by University City businessman Edward Gardner Lewis as part of his American Woman’s League—a for-profit organization that promoted voting rights, education, and other opportunities for women in the early 1900s.

The “Pastoral” vase came to the Smithsonian in 1979 from the estate of Robineau’s daughter, Mrs. Priscilla R. Kelley.

BONNIE LILIENFELD is Deputy Chair, Division of Home and Community Life, and Curator, Ceramics and Glass collection. She writes: “I credit my mother with instilling in me a love of history and of things. An avid collector of antiques and the caretaker for every piece of pottery her ancestors ever owned, she dubbed the sunroom of my childhood home ‘the Smithsonian’ and filled it with purchased and inherited treasures. I toddled off to the University of Chicago to become an Egyptologist and graduated in 1984 with a degree in music history, theory, and analysis. This, not so obviously, led me in 1987 to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where I have been ever since.

I started out cataloging and rehousing pens and the national paper-clip collection, among other things, and since 1989 I have been in the Ceramics and Glass collection. I was lucky enough to work for curator Susan H. Myers, who taught me the basics, turned me loose in the ceramics collection, and encouraged me to always look for the big picture. As the museum’s curatorial staff got smaller over the years, new opportunities opened up. In addition to caring for the Ceramics and Glass collection, I’ve co-curated a major transportation exhibition and an important collecting and exhibition project on the history of the bracero guest-worker program, led an enormous team to create displays in our central core renovation, and curated an exhibit that tells many stories of America from the 1600s to the present. I am now working on a big immigration initiative at the Smithsonian. Between museum-wide initiatives and day-to-day management responsibilities, I do not have much time to spend with the ceramics collection, but I value every moment I can get.”

Smithsonian Institution Archives, “Smithsonian Institution General History,” http://siarchives.si.edu/history/main_generalhistory.html (accessed January 26, 2014).

Smithsonian Institution Archives, “The Centennial Exposition of 1876,” http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits/baird/bairdd.html (accessed January 26, 2014).

Marcus Benjamin, “American Art Pottery” (reprinted from Glass and Pottery World, 1907); Paul Vickers Gardner, Meissen and Other German Porcelain in the Alfred Duane Pell Collection (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1956); Hans Syz, J. Jefferson Miller II, and Rainer Ruckert, Catalogue of the Hans Syz Collection (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979).

Ellouise Baker Larsen, American Historical Views on Staffordshire China (New York: Doubleday, 1950); Robert McCauley, Liverpool Transfer Designs on Anglo-American Pottery (Portland, Me.: Southworth-Anthoensen Press, 1942).

Janine Skerry, conversation with the author, October 5, 2006.

Rodris Roth, “Tea Drinking in 18th-Century America: Its Etiquette and Equipage,” Contributions from The Museum of History and Technology, USNM Bulletin 225 (1961).

Brandt Zipp, “The Thomas Commeraw Project,” www.commeraw.com (accessed January 26, 2014).

Ivor Noël Hume, “Cap-Hole Oyster Jars: A Racial Message in the Mud, or, Shipping Ostreidae Crassostrea Virginica,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2011), pp. 150–64.

Graham Hood, Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia: The First American Porcelain Factory, 1770–1772 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Va., 1972), a book reprinted in its entirety in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 2–75.

John L. Cotter, Daniel G. Roberts, and Michael Parrington, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992).

As this article was being prepared for publication, a previously unknown pickle stand was presented to the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a promised gift. The object has a history of descent in a Philadelphia family since the eighteenth century. American Ceramic Circle Newsletter (Spring 2014): 40–42.

Julia Wedgwood, The Personal Life of Josiah Wedgwood, the Potter (London: Macmillan and Company, 1915), p. 252.

Samuel Smiles, Josiah Wedgwood, F.R.S.: His Personal History (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1895), p. 281.

Arthur F. Goldberg and James P. Witkowski, “Beneath His Magic Touch: The Dated Vessels of the African-American Slave Potter Dave,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2006), pp. 87–88.

Acts 2:14–42 (Revised Standard Version).

. John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978).

Edward Steers Jr., Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), pp. 101–2; National Museum of American History, “Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life,” http://americanhistory.si.edu/lincoln/assassination-and-mourning (accessed January 26, 2014).

Brooklyn Museum, Luce Center, www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/research/luce/object.php?id=196784 (accessed January 26, 2014).

Ellen Denker, After the Chinese Taste: China’s Influence in America, 1730–1930 (Salem, Mass.: Peabody Museum of Salem, 1985).

Harmen Rooke Galleries, The Georgeanna H. Greer Collection of Important American Stoneware, sale cat., New York, January 13, 1993, lot 760.

Michael K. Brown, The Wilson Potters: An African-American Enterprise in 19th-Century Texas, exh. cat. (Houston, Tx.: Bayou Bend Collections and Gardens, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2002).

Robert W. Blasberg, George E. Ohr and His Biloxi Art Pottery (Port Jervis, N.Y.: J. W. Carpenter, 1973).

For the complete transcription, see Garth Clark, Robert A. Ellison Jr., and Eugene Hecht, The Mad Potter of Biloxi: The Art & Life of George E. Ohr (New York: Abbeville Press, 1989), p. 178.

Bonnie Lilienfeld, “Both an Honor and an Advantage: American Art Potters and the Smithsonian,” Style 1900 (Spring 2001): 36–41.

Sheryl Sandberg, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).