Lion figures, John Bell (1800–1880), Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, 1845–1850. Blue-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Impressed mark: “JOHN BELL / WAYNESBORO” (Courtesy, Collection of Robert A. Ellison Jr.; photo, Robert A. Ellison Jr.)

American China Manufactory Bonnin and Morris: American, active 1770–1772 Pickle Stand soft-paste porcelain overall 5 1/2" x 7 1/4". (National Gallery of Art, Promised Gift of George M. and Linda H. Kaufman; object #: X.45825, photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the stalk of the pickle stand illustrated in fig. 2.

Cooler, attributed to Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Collection of Robert A. Ellison Jr.; photo, Robert A. Ellison Jr.)

Detail of the cooler illustrated in fig. 4.

Set of six plates, decorated by James Callowhill, 1888. Blue-ground porcelain. D. of each 7 5/8". (Courtesy, Saint Louis Art Museum.) Each of the six plates, conceived in pairs, has a unique design, incorporating naturalistic flowers, insects, spiders and webs, all modeled in high-relief gold pastes in the Japanese taste that was popular during the American Aesthetic Movement. One is signed “Jas. Callowhill”; the others bear initials.

Presentation pitcher, Charles Cartlidge & Co., Greenpoint, New York, ca. 1853. Porcelain. H. 10 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens.)

Century Vase, Union Porcelain Works, Greenpoint, New York, designed by Karl H. L. Müller, 1876. Porcelain. H. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.)

Century Vase, Union Porcelain Works, Greenpoint, New York, designed by Karl H. L. Müller, 1876. Porcelain. H. 40 13/16". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.) The vase is shown on a pedestal, as it was at the Centennial in 1876.

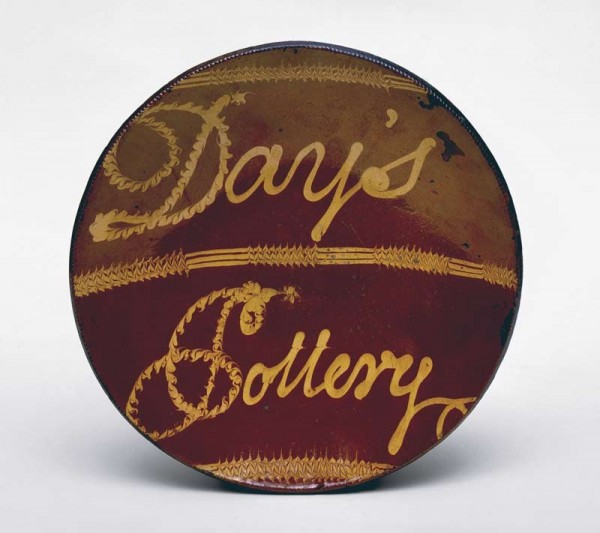

Dish, Absalom Day, Norwalk, Connecticut, ca. 1796. Slipware. D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.) This combed slipware charger was probably a shop sign or advertisement.

Loaf dish, Absalom Day (1770–1843), Norwalk, Connecticut, 1793–1796. Redware with slip decoration. L. 16 1/2". Mark: conjoined initials “AD” (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Bust of Dolley Madison, modeled from life by William John Coffee, 1818. Terracotta. Overall H. 13". (Courtesy of The Montpelier Foundation, James Madison's Montpelier.)

Reverse of the bust of Dolley Madison illustrated in fig. 12. (Courtesy of The Montpelier Foundation, James Madison's Montpelier.)

Plate, attributed to Johannes Neesz or Nase, Tyler’s Port, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1805–1820. Sgrafitto-decorated slipware. D. 12 1/2". Inscription [translated from German]: “I have ridden over hill and dale and everywhere found [pretty] girls” (Courtesy, High Museum of Art; photo, Richard P. Goodbody.) The plate is decorated with a popular image, said to be George Washington rousing the countryside to arms.

Spittoon, American Pottery Company, 1842. Earthenware. D. 8 1/4", H. 3 3/8". (Courtesy, The Franklin Institute, 77.1631.)

Medal, designed by Christian Gobrecht (engraver) for the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1842. Silver. D. 2". Marks: (reverse) “REWARD OF SKILL AND INGENUITY / To the / AMERICAN / Pottery Compy / for / Emboss’d ware, Jugs &c. / 1842 / G.” (obverse) “FRANKLIN INSTITUTE OF THE STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA. 1842”; “GOBRECHT” (Collection of the authors; photos, Diana Stradling.)

We have been married for fifty-two years and partners in the antiques business since we got our first resale number in 1967.

During a single week in 1962, we were married, moved to Greenwich Village, Gary changed jobs, and broke out in hives. Gary’s new employer, WNBC radio, generously added a day to our weekend honeymoon, and our wedding night was spent on the back seat of a Greyhound bus bound for Williamsburg, Virginia. There, and on a subsequent tour of Winterthur, we found we were comfortable living in the past, which set the tone for us ever after.

Manhattan was full of small auction houses, where Gary had hung out after arriving in the city in 1957. His first apartment was furnished from Tepper Galleries and we fell into a pattern of checking out sales to feather our new nest, but also found intriguing things to buy at shows and shops in the Village. A flow blue ironstone plate in Pelew pattern was an early acquisition that we gazed at for hours, imagining ourselves wandering amid the misty willow trees, islands, and pagodas of its mythical landscape. Columbia Auction Rooms in Brooklyn was another favorite haunt, where we searched among the remains of estates.

Gary’s grandfather had been vice president and his father Southern manager of John C. Winston Company, publishers of schoolbooks and Bibles. His mother illustrated some of their primers and Gary himself starred in a photographic pre-primer. Being asthmatic and allergy-prone, he was preordained to be a voracious reader. In his early teens, he sought out small bookstores, usually piled high with unsorted volumes and magazines.

It was books that led our way. For American ceramics we already had Edwin AtLee Barber’s Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, but one day in a Brooklyn bookstore he noticed a limited edition of a book he had never heard of, Our Pioneer Potters, published in 1947 and autographed by Arthur W. Clement. It was presented as “an accurate foundation upon which future research and writing may be based.”

Identification of American pottery often depends less on recognition than on knowing what it is not—and plenty of books were available about Continental and English wares. We cut our teeth on the works of Geoffrey Godden, learning about marks and the dating contexts of British pottery and porcelain. We also began accumulating a collection of objects as well as books on early Italian, German, Dutch, and French ceramics. We would read aloud to each other about our discoveries from books we had bought or borrowed.

With useful books and visual materials, Gary was able to prepare a lecture for the Pennsbury Manor Antiques Forum, where we encountered collectors from the American Ceramic Circle. Dealers were denied membership, primarily because some could not resist peddling their wares in parking lots at seminars or even inside the entry doors. One woman flashed Wedgwood jewelry pinned to the lining of her overcoat. A far more sensitive dealer, who promoted lectures and exhibits on ceramics, was all but reduced to tears by continual rejection of her membership applications (and never learned why). Eventually, the ACC agreed to accept scholar-dealers, beginning with the legendary Milly Manheim. We were asked to join as dealers 2 and 3.

On weekends, we paid our dues at Sunday street fairs and flea markets. Gary shared space with other dealers at Shupp’s Grove in Denver, Pennsylvania, and at Gordon Reid’s in Brimfield, Massachusetts. We exhibited at the New York Coliseum show in December 1967 and, in 1968, rented the lower half of a brownstone town house at 29 East 93rd Street, moved in, opened a shop on the parlor floor, and tried to stock the shelves with the best unpawnable merchandise we could afford—no jewelry, no gold, no silver. Gary circulated the word that if anyone stole anything from us, they would have as much trouble selling it as we did.

Untouched since the Gilded Age, the rear room was paneled in oak. Machine-made tapestries lined the walls above the dado and there was a stained-glass window. The front room was very Louis XVI, with mirrors between white panels and an art nouveau mullioned window overlooking the street. Wonderful encounters happened there. Walter Chrysler bought a Meissen teapot. We were photographed by New York Magazine. Vladimir Horowitz plunked a note on Diana’s out-of-tune girlhood piano, smiled, and sorrowfully closed the lid on the keyboard.

One morning, at PB84, Diana bonded with a decorator named Julia Winston, who insisted that we see the “19th Century America” show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (April 16–September 7, 1970). That exhibition altered our lives. We resolved to reach for quintessential examples of style, antiques with presence, the finest of their kind.

Armin Allen, Sotheby’s porcelain expert, stopped into our shop on his way home and became a great friend, asking us to help him catalog the Jacqueline D. Hodgson collection of American pottery, for auction in January 1974.

Later that year, we closed our shop and moved to 1225 Park Avenue, the last rental building below 96th Street. We were being invited into America’s most prestigious antiques shows—the Connecticut Antiques Show in Hartford, the University Hospital Show in Philadelphia, the Ellis Memorial Show in Boston, the Thrift Shop Show in Washington, D.C., and the Baltimore Museum Show.

Gary left broadcasting in the spring of 1978, and for the next ten years many memorable antiques passed through our hands. While we concentrated on early American ceramics and glass, we also dealt in furniture, sculpture, pictures, fabrics, and so forth. We had to draw a line somewhere, owing to the time it took to study each object, and did so, west of the Soviet Union. We sold eighteenth-century French and early Russian porcelains, including dishes from the “orders services,” but not Chinese export or, with rare exception, anything oriental.

Gary began writing reviews of auctions and museum exhibitions for Maine Antique Digest and articles on American pottery and porcelain. With his trained voice, he was a natural on the lecture circuit and was often included in Wendell Garrett’s seminars for Antiques.

In 1989 we decided to take part in a joint venture at the Place des Antiquaires on 57th Street. Diana, with Richard de Natale, a professional designer, created an attractive shop with robin’s-egg-blue fabric walls for the Place. But attendance slowly declined. Celebrities came in from time to time, like Oprah Winfrey with her entourage, but the hallways were often empty. Our impossible dream collapsed, and we moved with other dealers to a store on East 60th Street in the decorator district. This venture also did not work out financially, so finally we had to admit that we were not cut out to be shopkeepers.

At the same time, the costs of big shows continued to rise. The Philadelphia Show was our favorite, and we always said we would leave it last, which we did, regretfully, after thirty years. Although the spirit was willing, the flesh was getting weak.

We survived the economic ups and downs of the antiques world and became, however briefly, custodians of objects having a quality and presence equal to those we admired in books and at the “19th Century America” show so many years ago. Our ceramics can be seen at such museums as the Art Institute of Chicago, Bayou Bend in Houston, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Saint Louis Art Museum.

The money generated from these objects never appealed to us as much as the detective work and the objects themselves. Many have a life of their own and captivating stories to tell. Staring into the sunset after reviewing our eclectic career, we anxiously await the future, which one prominent curator has predicted will be a deep, dark digital age.

The Pride of the Valley

Question: What gets the attention of a Southern folk art collector faster than fried chicken and grits or ham with redeye gravy?

Answer: A John Bell pottery lion.

Billy Wiltshire, author of Folk Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley, put his on the dustjacket cover.[1]

Of the five John Bell lions known today, we have had two (fig. 1). In January 1978, during a Winterthur Ceramics conference weekend, a friend came to our motel room at Longwood Gardens with a heavy blue stoneware lion impressed “JOHN BELL / WAYNESBORO” to be taken on consignment. Scarcely more than three months later, we were at a local bank in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, examining an unmarked earthenware lion, like Wiltshire’s, which we bought, following negotiations with a man in whose family it had descended and his lawyer.

The stoneware lion came with an affidavit by John Bell’s granddaughter Miss Carlton Newman, prepared for posterity in Hagerstown, Maryland, on September 15, 1934. She stated that Bell had established his pottery in Waynesboro in 1833 and had made “this stoneware dog” especially for “my mother Mary Elizabeth Bell Newman to be used as a doorstop and to the best of my knowledge and belief is the only one produced by John Bell of the special mixture of certain clays and glaze.”

The owner of the earthenware lion told us his family had also used it as a doorstop. Miss Newman’s description of her lion as a “dog” reminded us that large spaniels on rectangular bases were called “hall dogs” by mid-nineteenth-century potters.

John Bell was more comfortable making earthenware, but began experimenting with stoneware, while keeping in touch with his brothers, Samuel and Solomon, who had built a stoneware kiln in Strasburg, Virginia. John had used zaffre, or “zafree” as it was sometimes called colloquially, to color his lion and was disturbed when some of its thick blue coating sloughed off. In a letter he wrote to Samuel in 1848, probably about the time he made the animal, John warned about cobalt, which was used in making domestic fly killer, and suggested what he called “graffree” instead: “Graffree [sic] is calcined cobalt or flystone which is the same thing.” “[T]the coloring matter is rank poison be careful with it from it all smalts & blues are made that pass through the fire. if you cannot get graffree do not try to calcine cobalt you can get cobalt in any drug store they onley pay 25 or 31 cts per pound.”[2]

John offered an alternative: “I heare give you a receipt, & in your stone ware kiln you can try it put it in the hottest place, there is no heat too grate for it—1 part Cobalt, 1 part potash & 1 part white flint pount & mix & put them in your hottest part of the kiln to melt.”[3] As a result of examining each of the John Bell lions, we can attest that all but the stoneware lion were made of heavy, lead-glazed, buff-colored earthenware, like fireclay, with applied brown coleslaw manes, tufted tails, and mustaches. Of these, only one, currently in the Henry Ford Museum, is stamped JOHN BELL on a rear leg. Every one could be relied on to hold a door open against the wind.

Collectors who insist that folk pottery must be shaped by hand may be disappointed to learn that John Bell lions are basically molded creatures. The fireclay examples are identical in form, 7 1/2 inches high and 8 1/2 inches long, with hollow bodies and stomachs revealing mold seams. The stoneware lion is slightly smaller overall, because of differences in the clay body and/or shrinkage in the kiln.

Both of our lions were bought by a man who facetiously referred to himself as “a collector of John Bell lions.”

The Irresistible Allure of Bonnin and Morris

In the fall of 1981, a rather timid man brought an unusual “candy dish” to Sotheby’s for evaluation (fig. 2). He had purchased it at a yard sale for two dollars and was intrigued enough to try to learn more about it. The dish had three half-scallop shells on triangular feet around a vertical shaft encrusted with tiny seashells and topped by an open shell-form cup (fig. 3). The rim surfaces had been brushed with blue and on the bottom in underglaze blue was a small blue capital “P.”

Letitia “Tish” Roberts, Sotheby’s porcelain expert at the time, examined the dish and told the potential consigner it was an eighteenth-century pickle or sweetmeat stand and suggested the small blue “P” might stand for Philadelphia—the location of Bonnin & Morris, the first porcelain manufactory in colonial America. When asked about its value, Tish tossed out a figure that shook the man so badly he blurted “Take it away!” and refused to touch it again.

Identification of American porcelain requires familiarity with chinaware of other lands, since many shapes and decorations are derivative and therefore difficult to distinguish from the English, French, German, or Italian. Moreover, because most clays and feldspar found in America during the eighteenth century did not behave predictably when used in recipes proven abroad, china makers often imported materials. After all, a single kiln load of porcelain reduced to worthless melted blobs all but ensured financial disaster. Nevertheless, Gousse Bonnin and George Anthony Morris chose to use clays from the Delaware River and other American materials, and perhaps some fine kaolin from South Carolina, for making porcelain in Philadelphia between 1770 and 1772.[4]

The pickle stand was scheduled to sell at Sotheby’s in January 1982. By then, we had handled so much Union Porcelain Works, Charles Cartlidge, Ott & Brewer, and the like that we were beginning to think our middle name was “American Porcelain.” We believed this was the first time a Bonnin and Morris product had ever been offered at public auction, so we had to try to buy it—and we did.

The five-figure price we paid for a “two-dollar candy dish” generated a media frenzy. Television and news cameras were waiting for Gary after the sale, and he was interviewed by Clavin & Finch, the popular hosts of a morning show in New York. Overnight, American porcelain was regarded with new respect, and, for that matter, so were we. For many collectors and museum curators, Bonnin and Morris porcelain is now the “holy grail” of American ceramics. Numerous sherds have been recovered from beneath the earth, some glued together. To date, though, only twenty reasonably intact examples have been recognized aboveground.

We studied the pickle stand for a month and had it photographed for a full-page ad in Antiques magazine. Ever since, we have been offered important objects and found ourselves becoming specialists in American pottery, porcelain, and glass.

Sadly, the nervous man who consigned the pickle stand was not on hand to share in the excitement. He had died of a heart attack several weeks earlier, without heirs.

Boston Stoneware Cooler, Attributed to Jonathan Fenton

In April 1978 we were setting up to do the White Plains Antique Show when a blur of stoneware moved past our booth and we had enough presence of mind to shout “STOP!” In the arms of Peter Tillou was possibly the best American stoneware cooler we had ever seen (figs. 4, 5). He had just found it in another booth and was trotting it over to his. Needless to say, it remained with us.

Because this cooler had an applied eagle and stars, Peter and the other dealer had guessed it might be mid- to late-nineteenth-century Ohio, by a potter such as A. Hall, who often applied interesting reliefs to his stoneware. At first glance we might have agreed, but we had a feeling this cooler might be much earlier. It was thinly potted, had open loop handles and a baluster shape that we had seen in eighteenth-century pottery. And the handles were set several inches below the rim—distinctive characteristics we confirmed when we got it home to study.

Our first step was to revisit The Art of the Potter: Redware and Stoneware, an anthology we had edited in 1973–1974 of articles previously published in Antiques. We had been tasked with selecting articles with information still accurate and writing introductions to each regional section. We looked through Rhea Mansfield Knittle’s pictures of Ohio stoneware with applied reliefs and another article on Illinois, but it was Lura Woodside Watkins’s images of early Boston pots that trumped all. On page 82, in her article “New Light on Boston Stoneware...,” are the distinctive shape and the low handles on a pot impressed with the word “Boston” along with the incised monogram of Jonathan Fenton, who had worked at the Lynn Street pottery from 1793 until 1796, when the pottery closed and he departed for Dorset, Vermont.

As we photographed and cataloged the cooler, we wondered about some details. Why was the banner above the eagle left blank? No name was incised or brushed on, yet tiny initials—“R.H.W.”—were impressed on it, perhaps those of a tavernkeeper. Why was the cobalt blue brushed ribbon-fashion around the loop handles? But then, down in the cross-hatching, we found flecks of gold leaf and red and white. This cooler had been japanned, and what a sight it must have been, with a gilded eagle, the name of a tavern painted on that blank banner, and ribbons of red, white, and gold alternating with the blue on the handles!

To this day, it remains Diana’s pick as the finest example of American stoneware she has ever seen.

James Callowhill, China Decorator Extraordinaire

When we noticed an upcoming sale of the collection of Dorothy-Lee Jones, the founder and curator of the Jones Museum of Glass & Ceramics in Sebago, Maine, we knew there would be many of the top-level objects that had been exhibited there from time to time. Among our purchases was a set of six plates (fig. 6).

The Callowhill brothers, James and Thomas Scott, were award-winning decorators at Royal Worcester. Their specialty was working with gold pastes in chinoiserie and japanism. They emigrated from England with their families to America circa 1883. A few illustrations of their English work appear in an 1884 catalog by R. W. Binns, then owner of the Royal Worcester Works.[5] To our eye, their work in England was accomplished but predictable.

In 1888 James entered his work in “the first national exhibition of American pottery and porcelain and its decoration,” held by the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, which opened October 19 of that year. This show of talent had been enthusiastically promoted by The China Decorator, a magazine founded in 1887. James did not escape comment by its editor, Mrs. O. L. Braumuller, who wrote in the November 1888 issue: “James Callohill [sic] exhibits some very good work, albeit somewhat weird. Three plates or plaques in raised paste and gold in Japanese style of decoration....He also sends six plates in blue underglaze with all-over decorations in paste and gold.”[6]

The next issue, of December 1888, proclaimed that the six plates entered by “Jas. C. Callohill of Roslindale, Mass.” had won an Honorable Mention. The six blue plates can be none other than these. We have also owned two of the plaques mentioned by Mrs. Braumuller, which were elaborate conceptions of a Japanese garden. All were signed with his own name or initials, and each is a unique, innovative, design.[7] We came to realize that these were personal works and that in America James had allowed his imagination to burst free, and we are fortunate to have had them for awhile.

The brothers subsequently influenced or worked on the ivory porcelain “Belleeks” of Trenton, New Jersey, and on the faience at Green Point (now Greenpoint, part of Brooklyn), New York, where sculpted gold paste, worked in the manner of Royal Worcester, flourished until the Aesthetic Movement ended with the century.

The Jonathan Crane Presentation Pitcher

Charles Cartlidge, who first came to America as a sales agent for the English firm of William Ridgway & Co., established a porcelain works in Greenpoint, New York, circa 1846. Rather than slavishly copy British patterns, as was customary, he decided to produce original American designs. His brother-in-law, Josiah Jones, modeled for him a pitcher in the form of an ear of native Indian corn as well as this stylized acorn-and-oak-leaf pattern fronted by a spread eagle above a shield with a ship’s anchor beneath. Of particular note are a pair of pitchers made circa 1853 for real estate developer Jonathan Crane. One of these is now in the Bayou Bend Collection (fig. 7).[8]

Early in the 1850s, Greenpoint enjoyed a brief burst of development when shipbuilding expanded across the East River to the Long Island shore. Eliphalet Nott, director of Union College in Hamilton, New York—a brilliant man, holder of many patents—had hit on a scheme that would benefit the college, intending the profits to establish and maintain nine professorships. He and his wife had purchased the Hunter Farm and used its soil to fill and extend the shorefront from what had been West Avenue into the East River, thus providing new foundations on which to build dry docks for the burgeoning shipbuilding industry. Jonathan Crane and Charles Ely were partners in real estate and, for a time, were Nott’s agents. The evening edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of February 24, 1853, published a notice of the application of Crane and Ely to New York State for underwater lands at the mouth of Newtown Creek and the East River. This, apparently, was where they would deposit the soil. In the very same column is a similar notice in the name of Charles Cartlidge, perhaps a co-investor in the same scheme. Who actually commissioned the “Crane” pitchers is unknown, but it is certain they were made by Cartlidge.

It may well be that the nautical symbolism of the anchor on this pitcher was a reminder that Greenpoint was, or aspired to be, a maritime center. Other pitchers in this form bear painted legends, such as “Assembly of the State of New York” (like that in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum).[9] It had always been assumed these pitchers were made for official banquets, but now they may be interpreted as outreach to the politicians who held the power and the purse strings to further the project.

Crane was replaced as agent for Nott in 1855 by a Mr. H. S. Anable. The deepening recession before and after 1857 slowed the economic boom in Greenpoint, and wooden hulls were soon replaced by iron ones. Charles Cartlidge lost his money in bad investments, incorporated his company, and was forced out by its directors, probably by 1856.

The Wondrous American Century Vase

“American Ceramics and the Philadelphia Centennial,” by J. G. Stradling, was featured in the July 1976 issue of Antiques. Essential to his research was the only surviving complete run of the Crockery and Glass Journal, a weekly trade publication that began publication in 1874, as the Crockery Journal. Bound volumes of this periodical were donated by its publishers to the New York Public Library, where they were kept in a branch on 43rd Street near 11th Avenue known as “The Annex.” According to glass scholar Paul Hollister, who was researching international fairs, “You needed a visa to get to the Annex.”

Paul and Gary were amazed to be allowed to photocopy these newspaper-size pages, one from the top and one from the bottom of each page, on the Annex’s oversized photocopier. Then one day Gary was told the Journal was unavailable, having been sent to Chicago for microfilming, but was assured it would be back soon. For months he heard the same bad news, so finally he went to the head librarian. “Oh, no,” said the man, “it’s not coming back. When large volumes are microfilmed, the contents have to be cut apart, so the originals are destroyed.”

Outraged, Gary called the administrative offices of the New York Public Library and reached a senior archivist. Protesting the destruction of the Journal, with its hundred-year-old factory descriptions, advertisements, and obituaries, he promised that if shreds and pieces were gathered into green bags, we would buy them. “Are you trying to tell me that the pages of the Journal are artifacts?” he was asked. “If that’s what you wish to call them,” Gary said, “YES!” “Well, I’ll stop them immediately,” he replied.

Today, the original Crockery and Glass Journal pages have been rebound, and researchers may request them at the library of the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum at Fifth Avenue and 91st Street in New York City—minus the year 1876, which had already been lost in the process. Tragically, even the microfilm is incomplete. Susan H. Myers, curator of Ceramics and Glass at the Smithsonian Institution, had ordered the complete year of 1876 for use in planning the bicentennial celebration in Washington, but she received only a portion—six months. Neither issues nor film of the missing months have ever turned up. All that remains of this important period are the quotations in Gary’s article and his handwritten notebooks and photocopies.[10]

Possibly the most impressive array of American porcelain in the centennial display was that of the Union Porcelain Works of Greenpoint, New York, with sculpture, elaborate table services, and whimsical animals. The star of the exhibit was the Century Vase, designed by proprietor T. C. Smith and executed by designer Karl H. L. Müller (fig. 8). Smith was an occasional builder and chose to represent the “Century of Progress” in an architectural format, with a frieze of sculptural panels around the base depicting scenes of American history in biscuit porcelain—Penn’s Treaty, a settler in a log cabin, Sir Frances Marion (the Swamp Fox) serving sweet potatoes to British officers, the Boston Tea Party, an Indian chief, and a soldier at Valley Forge—all beneath a molding studded with animal heads. On the glazed body above, on either side of a biscuit relief portrait of George Washington, were painted scenes of advances in American technology: a Singer sewing machine, McCormick reaper, telegraph wires being strung in the West, a steamboat, a floating grain elevator, a farmer using a hand plow, and a potter jiggering a plate.[11] A fierce American eagle surrounded by lightning bolts presides over all, and, to complete the American theme, a pair of bison heads are the handles.

According to the report from the Crockery and Glass Journal, which Gary quoted in his article, “At two corners of the large glass case are pedestals. [that] support a pair of vases upon whose bases...in bas-relief, we find Penn treating with the Indians, a log cabin.” There is another Century Vase in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum which had come directly from the home of Smith family descendants. A national icon, it had appeared on the dust jacket of Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen’s catalog of the Metropolitan Museum’s American porcelain show in 1989.

One man refused to believe there were two. Elliot Wysor, a retired lawyer and part-time antiques dealer, insisted that his was the one on exhibition and that Brooklyn’s was a copy, right down to the misspelled word “exhibitien” on the base. He had been asking an astronomical price for his vase. Only when we showed him Gary’s photocopies from the Journal did his aspirations descend from the heavens. We alerted curator Donald C. Peirce of the High Museum in Atlanta, who was then able to negotiate its purchase for the Virginia Carroll Crawford Collection (fig. 9). This vase was pictured for the first time in Gary’s article.

Day’s Pottery Dish

Found upstate and brought to New York City by dealer Ronald DeSilva, this slipware dish (fig. 10) moved quickly to George Schoellkopf’s gallery, where it caught the eye of collector Barry Cohen, in whose home we first saw and coveted it. It was the touch of humor—those little “splats” at the start of “D” and “P,” maybe wayward drips that the potter combed over—that captivated Diana. When terminally ill, Barry must have promised all admirers that the plate was reserved “for you,” but executor Gerald Kornblau sold everything to dealers Joel and Kate Kopp of America Hurrah and David and Marjorie Schorsch. Disputed objects were settled by private bidding, and we fended off all contenders.

Not just a great example of American “folk art,” this plate is also important as the embodiment of the eighteenth-century transition in eastern Pennsylvania pottery from wheel-thrown redware pans to scoop-shaped pie plates formed by draping a flattened sheet of clay over a mold. German potters coexisted there with English ones, and traditional foodways met and merged. Henry C. Mercer wrote: “The [fruit] pie of the United States evidently developed here about 1750 and [was] entirely a product of the bake oven since it could not have been cooked often in the open fire or in Dutch ovens.”[12] Thus, there was a need for a new baking dish, and the form of the English meat pie dish was adapted to the American fruit pie.[13] It evolved as a “simple hollowed disc, notched around the edge, an unbroken curve” formed over a mold. A pie would slide easily from such a plate.

Writing forty-seven years later on New England redware, Lura Woodside Watkins tracked the pie plate migration. She noted the marked influence of New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania on Connecticut redware, and reported that the notched-edge plates and platters were made only in Connecticut, and that the “use of molds was restricted to Southwestern Connecticut, and then only for pie plates and platters or trays.”[14]

It was Absalom Day (1770–1843) who brought the Philadelphia techniques of slip decoration to Norwalk. Born on May 15, 1770, in Chatham, New Jersey, he arrived in Norwalk in 1793. He was already a trained potter, and went to work for Asa Hoyt and his sons, teaching them as well as other important Norwalk potters—John Betts Gregory, the Smiths, the Quintards.

While the “Day’s Pottery” charger is stunning in the austerity of its design, Absalom Day was capable of exuberance, as demonstrated by a loaf dish (fig. 11) in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, identified by a group of redware enthusiasts. The conjoined initials “AD” surrounded by curlicues of combed slip show that Day made this loaf dish for his personal use, possibly while working at the Hoyt pottery, where green (from copper oxide) was often sprinkled on the ware.

On January 1, 1796, Asa Hoyt Jr. sold Day a property with a “potter house” at Old Well, and Day was in business. Before long he had married and was peddling his ware by boat all over Long Island Sound, as far as New York City and the Eastern Seaboard.

Hello Dolley!

When Gary’s widowed mother was alive, we used to drive between New York and Atlanta, Georgia, to be with her for Christmas. On our way, we would scour the countryside from Virginia southward for local redware and stoneware, which at that time received little respect from collectors. We would also visit the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, to consult its research files and to talk with Frank Horton, John Bivins, or Brad Rauschenberg.

Brad was writing an article on William John Coffee (1774–ca. 1846), a British-born artist and sculptor who emigrated to America circa 1816, established a studio in New York City, and quickly found work executing portraits from life in both terracotta and plaster.[15] He started out as a chore boy at Coades Artificial Stone Manufactory in Lambeth but by 1810 was employed by the Derby porcelain factory as a modeler and sculptor.

Brad explained to us how the demand for portrait busts attracted foreign artists and shared photographs of Coffee’s work, in which subjects were depicted with long necks and a scooped-out area in back. Brad believed that Coffee went to Monticello in the fall of 1817 to sculpt Thomas Jefferson as well as Jefferson’s daughter and granddaughter. Jefferson was so pleased with the results that he recommended him to friends and neighbors, including James Madison, who invited Coffee to produce likenesses of his family. On July 14, 1818, Coffee submitted a bill of $105 for terracottas of Madison, Mrs. Madison, and John Payne Todd, her son by a previous marriage. Later, Jefferson asked Coffee to make busts of his other grandchildren. Two of these terracottas have survived, but, as Brad noted in his article, “None of the Madison busts are known today.”

We both enjoyed sculpture and were buying and selling eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century French faience and porcelain, when, in 1987, during our weekly rounds of auctions, we spotted a small terracotta bust of a woman in a crowded showcase (fig. 12). Thinking it might be French, we had a closer look. A victim of neglect, the lady had a broken neck and was covered with dust, yet her face remained remarkably unscarred. She seemed like the work of an artist of the late 1920s or early 1930s, but on her back was incised “EX PRESIDENT, MRS. MADISON.” Was this one of the long-lost family busts by William John Coffee?

Like other Coffee busts she was of relatively small size—13 inches high, including socle—and she had the requisite long neck and scooped-out back (fig. 13). While her pretty face might be considered idealized, Dolley Madison had been the queen of Washington society, even before her husband’s presidency. By the time we purchased the bust, we were convinced we owned a Coffee portrait.

Our next step was a no-brainer. The bust had to go to an important conservator, and we chose Steve Tatti, a specialist in sculpture, known for his studio’s work in New York as well as Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, Ed Sheppard, a knowledgeable dealer and friend, had been looking through a 1938 sale catalog of the Erskine Hewitt collection of Americana and discovered that our bust of Dolley had been lot 1127, with provenance dating back to Dolley herself, to her niece, and down in the family. Somehow, in the ensuing years, it had disappeared into the vast Sargasso Sea of possessions that every now and then reappear in estate sales.

As soon as the bust came back to us, we had it photographed and placed an ad in Antiques. Not wanting to play favorites, we sent sixteen letters simultaneously to museum curators and collectors, but a private person snapped it up from the ad. We provided her with the provenance and delivered it to her home. She told us she intended to donate it to Montpelier, the restored residence of the Madisons in Orange, Virginia, and it is currently on display there.

We have never seen another Coffee bust for sale, but considering his output over a period of more than ten years, it is likely that eventually one will surface. Now that we are familiar with the hand of the artist, we are prepared to pounce.

Johannes Neesz Horseman Plate

We bought this plate (fig. 14) at auction after it was deaccessioned by the Art Institute of Chicago. No sooner was it hammered down than a friend whispered in our ear that Winterthur had declared a nearly identical plate to be a fake. As our new acquisition had been in the Chicago museum since 1907 and, we were told, had been transferred from another institution before that, we were certain this dish was no fake, but what about Winterthur’s dish? It had been loaned to a Brandywine Museum antique show, as “later,” and was published in Winterthur Magazine with the caption “Formerly attributed to Johannes Neesz, 1800–1820, but now unattributed and redated 1880–1920, late 19th century.”[16] We had no choice but to defend our plate and compare it in person with the one at Winterthur.

The source of the downgrade turned out to be the young conservator who had cataloged their plate. Among his suspicions: it looked too new, with no signs of wear; the cream slip was too pale; details of the horse had been rubbed out and redone, suggesting that an unsure hand was copying; the use of blue was unusual; there was no German inscription around the rim.

The two plates did indeed look as though they had been made on the same day—both surfaces matte with almost no glaze, both with touches of blue coloring. We and the curators, led by Amanda Lange, took both plates down into the collection rooms and compared several side by side. It was a revelation. Blue was used by Scholl, the Neesz/Nase family, and Spinner. Around the outer circumference of the Horsemen plates was an endless variety of carved flowers, no two alike, all by the same sure hand. In the centers were the horsemen, all outlined with a fine stylus, a very different instrument from the tool used to carve the flowers. All the horses seemed to have the same shape, and yes, details on many plates, not just one, were rubbed out and redone. We agreed that there were definitely two different “decorators” at work on these plates.

Bea Garvan had gotten wind of all this and sent a wonderfully concise postcard, which was shared with us:

Read with interest about the “fake” Neiss plate. Can’t agree yet although I haven’t examined that plate. / Look at PMAs #93-219 & others accessioned too early for “fakes”. Also note bios—there were several / succeeding Neis—one died in 1867 and they did indeed trace & copy patterns....Lots of PMA’s best plates / (like Spinner series) show no wear—important that they don’t because they were never used by Pa. G. / owners... / [signed] Bea Garvan, ex PMA[17]

We turned to Edwin AtLee Barber’s 1903 book Tulip Ware of the Pennsylvania-German Potters to review what he had to say, only to find he had scooped us ninety years earlier:

Among the pieces procured from some of the surviving relatives of John Nase are a number showing his best work. These are in an excellent state of preservation, never having been in use...the condition of some of these is so new and fresh that were it not for their complete and satisfactory authentication, their age might well be questioned. Several...possess a marked peculiarity in the absence of the usual lead glaze, being covered with a thin, dull gloss.[18]

So! Our plate must have been one of the original group procured by Barber directly from the Nase family before 1903, then perhaps traded(?) in 1907 to Chicago.

P.S. The Winterthur plate was reinstated.

David Henderson and His Pottery

Reporting on its twelfth annual exhibition in 1842, the Journal of the Franklin Institute included the following note under the heading “XIV. Glass, China and Earthenware”:

[O]ne of the most interesting and generally noticed portions of the display at this exhibition consisted of the articles of earthen ware....The Committee awards to the American Pottery Company, of Jersey city, for No. 31; / deposited by Peter Wright & Sons, and consisting of embossed-ware jugs, tea ware, spittoons, &c., of spittoons / with white raised figures, of druggists’ jars, &c. / A Silver Medal.[19]

One of the prize-winning spittoons was still there fifty years later (fig. 15). In his The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, Edwin AtLee Barber wrote, “A glazed white-ware spittoon...is still preserved in the cabinet of the Institute...decorated with raised, conventional designs in white, on a dark-blue ground, the upper surface being fluted and in solid blue.”[20]

Because one of Diana’s lifelong projects has been writing a book about David Henderson, proprietor of the American Pottery Company, she made a mental note to call the Franklin Institute if we found ourselves in Philadelphia with time to follow this lead. Even though we had been informed there was nothing left of the old collection, still we had to try.

The day came in August 2006. Diana called, eventually reached “Charles,” the cataloger, and asked to see the blue-and-white spittoon. Inexplicably, he demanded to know who she was, what she knew, and how she knew it. Not having Barber with us, she could only answer that it had been on her list of research to do, and if it was there, she’d like to photograph it. “Well, come over,” he said. Once there, we were introduced to the director and senior curator, John V. Alviti, who gave us some material to review.

Then Mr. Alviti said, “And now I will get the piece of china.” He returned to present us with cotton gloves and reverently placed before us a perfectly stunning spittoon, with creamy white Gothic tracery on a blue ground. Visible on the edge of the “pouring hole” was a thin blue line dividing the white clay layers of the interior and exterior, revealing that the outer layer, a delicate filigree, must have been sprig-molded and laid over the blue slip while still soft. The clay seemed porcelaneous as it had a slight sheen, and enough translucence that a hint of blue could be seen through the white body where thin. This was a tour de force in clay engineering and skill. Strangely, however, it was unmarked. Despite himself, and despite all we have done to dispel that myth, Gary reverted to that old mantra we used to hear early in our career: “It must be English. It’s too good to be American!”

In fact, in 1828, when D. & J. Henderson started their Flint Stoneware manufactory, it was universally believed that Americans could never produce ware as good as, and as cheap as, the imports. On February 4, 1837, Henderson himself wrote to Senator Silas Wright, chairman of the Finance Committee, and described his achievement: “[T]his successful attempt in the United States to produce the English Earthenwares from native materials (it having been always considered that they could not be made)...until recently made at this Establishment in Jersey City.”[21] His silver medal of 1842 was vindication, proof positive that he had succeeded.

Had it been marked, this elegant object would have been returned to its maker. Instead, it waited 164 years for the words of Barber to restore its identity. We tried to arrange a transfer to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but, after mulling it over, the Franklin Institute decided to keep the spittoon.

By some serendipitous coincidence, we already owned the 1842 silver medal, which we had purchased in 1996 (fig. 16).

JAMES GARRISON STRADLING, author, lecturer, and partner in the firm known as The Stradlings, has brought journalistic training to the field of antiques and is recognized as an authority on early American ceramics and glass. Born in Portland, Maine, “Gary” learned early about art at the knee of his mother, an amateur painter. Educated at Middlesex School in Concord, Massachusetts, he graduated from the University of Georgia with an A.B. degree in journalism and immediately began a full-time job as television announcer and director at WSB-TV in Atlanta. Several years later, at the request of the dean of the university, he returned for a year, as assistant professor of journalism, to help the Henry W. Grady School get accreditation for television.

Relocating to New York City, Gary held various positions at the United Nations Office of Public Information and headed the field office for the United Nations Emergency Force in the Gaza Strip in 1959–1960.

In 1962 he was invited by the program manager of WNBC radio, Steve White, to become the station’s public affairs manager. Many of the radio shows Gary scripted and produced (some award-winning) are kept in the archives of the Library of Congress. After moving up into management of the NBC Television Network, he went to ABC Television and became supervisor of unit managers handling network entertainment programs originating in New York.

Gary is currently a member of the American Ceramic Circle and served for eleven years as a trustee of the late lamented Jones Museum of Glass & Ceramics. For fourteen years he was an appraiser of pottery and porcelain for The Antiques Roadshow, on public television.

DIANA STRADLING is grateful to have had an early education at Great Neck High School on Long Island, where art, languages and literature were included in the curriculum. Graduating in the top twenty of her class of nearly four hundred, she was granted a small scholarship that paid for a year of study at Western Reserve University (now Case Western Reserve University) and the Cleveland School of Art (now Cleveland Institute of Art). One inspiring course there was a survey of the relationships between fine art, sculpture, and architecture throughout history. The nearby museum of art and a job ushering for the Cleveland Orchestra were extra benefits, supplemented by waiting tables at school. From there, Diana’s self-directed education included courses at the New School, art education at New York University, decorative arts history at the New York School of Interior Design, and summer stock as a scenic apprentice, where she learned to use tools and got to sing “Shine on Harvest Moon,” off-key, while briefly sharing the stage with Ethel Waters. Professionally, she has freelanced in design, decorating, illustrating, and editing.

William E. Wiltshire III, Folk Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1975).

The letter was transcribed in A. H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery (Strasburg, Va.: printed by Shenandoah Publishing House, 1929), p. 45, one of the first books about valley pottery.

The John Bell letter is important because it illustrates problems that bedeviled early potters, now forgotten. The “rank poison” in the “calcined cobalt or flystone” that Bell warned against was arsenic, which occurred naturally in the ore and could be partially removed with successive calcinings (roastings), a lengthy and dangerous process. Modern potter manuals (Cardew, Campbell, Rhodes) do not mention any problems with arsenic because commercial refining of raw materials has eliminated it. The alternative formula, which Bell gave his brothers, would make a blue glass—i.e., a frit—which renders raw materials nontoxic and nonsoluble when ground fine and mixed into the glaze.

For more extensive information, see the 2007 edition of Ceramics in America, which is devoted to eighteenth-century porcelain in colonial America. The volume contains essays by authorities on the subject (including us). See also Diana Stradling, “Bonnin & Morris: Reading between the Lines,” Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle 20, pt. 3 (2009): 613–31; and Diana Stradling, “Bonnin and Morris: Reading between the Lines,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 179–99.

R[ichard] W[illiam] Binns, Catalogue of a Collection of Worcester Porcelain and Notes on Japanese Specimens in the Museum at the Royal Porcelain Works (Worcester, Eng.: Royal Porcelain Co., 1884).

The China Decorator 3, no. 6 (November 1888): 118; The China Decorator 4, no. 1 (December 1888): 123. This little-known magazine was brought to our attention by the late Florence Balasny Barnes.

Ruth Irwin Weidner, “The Callowhills, Anglo-American Artists: An Introduction,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 10 (1997): cover illus. and pp. 3–30. One of the six plates is illustrated. Barbara Veith, Aesthetic Ambitions: Edward Lycett and Brooklyn’s Faience Manufacturing Company (Richmond, Va.: University of Richmond Museums, 2011), esp. pls. 54–57.

Henry Silka, “Shipbuilding and the Nascent Community of Greenpoint, New York, 1850–1855,” available online at www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol16/tnm_16_2_15-52.pdf (accessed August 7, 2014); J. S. Kelsey, A.M., History of Long Island City, New York: A Record of Its Early Settlement and Corporate Progress (Greenpoint, N.Y.: Long Island Star Publishing, 1896), available online at https://archive.org/details/historyoflongisl00kels (accessed August 7, 2014).

Marvin D. Schwartz and Richard Wolfe, A History of American Art Porcelain (New York: Renaissance Editions, 1967), p. 37, pl. 17.

J. G. Stradling, “American Ceramics and the Philadelphia Centennial,” Antiques 110, no. 1 (July 1976): 146–58. Partial descriptions of the display mounted by the United States Potters’ Association may also be found in other sources cited in the article, including the Philadelphia Public Ledger of November 1876, and some after the exhibition had closed, in the possession of the Philadelphia Free Library.

In his article, Gary mistakenly identified the floating grain elevator as a rising support for the Brooklyn Bridge. For this, he would like to apologize to readers who recognized the error that he refused to believe.

Henry C. Mercer, Tools of the Nation Maker: A Descriptive Catalogue of Objects in the Museum of the Historical Society of Bucks County, Penna. (Doylestown, Pa.: printed for the Society at the Office of the Bucks County Intelligencer, 1897).

Peter C. D. Brears, The English Country Pottery: Its History and Techniques (Newton Abbot, Devon, Eng.: David and Charles, 1971), pp. 110–11.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), pp. 171, 5.

George C. Groce and David H. Wallace, The New-York Historical Society’s Dictionary of Artists in America, 1564–1860 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1957), p. 135. For this information we leaned heavily on Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “William John Coffee, Sculptor-Painter: His Southern Experience,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 4, no. 2 (November 1978):26–48. Any person seeking serious information on Coffee must consult this excellent source, which is available online at https://archive.org/stream/journalofearlyso0402muse#page/26/mode/2up (accessed August 7, 2014).

Winterthur Magazine (winter 1991): 9, fig. 5.

Beatrice B. Garvan, former associate curator of American art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and author of The Pennsylvania German Collection (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982).

Edwin AtLee Barber, Tulip Ware of the Pennsylvania-German Potters: An Historical Sketch of the Art of Slip-Decoration in the United States (Philadelphia: Patterson & White Co., 1903), pp. 148–49.

Bruce Sinclair, Philadelphia’s Philosopher Mechanics: A History of the Franklin Institute, 1824–1865 (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974).

Edwin AtLee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, To Which Is Appended a Chapter on the Pottery of Mexico, combined ed. (1909; reprint, New York: Feingold & Lewis, 1976), p. 121.

Handwritten letter from David Henderson, Jersey City, to Senator Silas Wright of New York, postmarked February 6 [1837], New York. The National Archives Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46 Sen 24A-D5.