High chest by John Head, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1726. Walnut with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 66 7/8", W. 42 1/8", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Lydia Thompson Morris; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table by John Head, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1726. Walnut with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 29", W. 33 5/8", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Lydia Thompson Morris; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

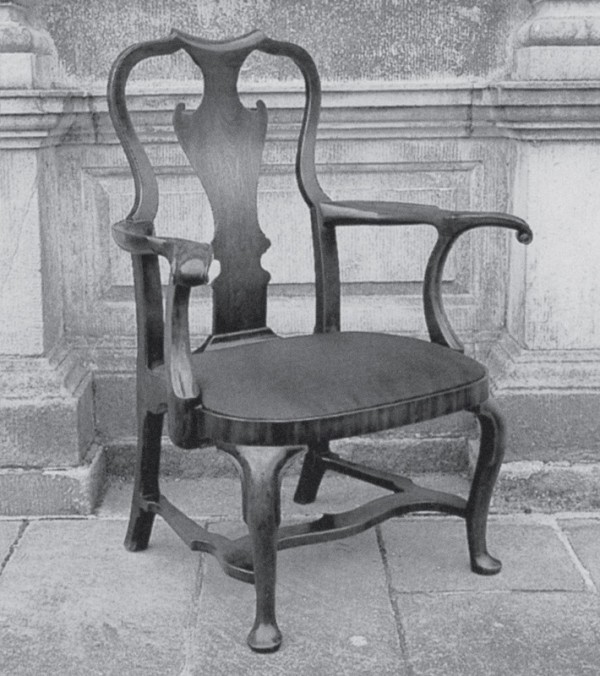

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1745. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 42 1/4", W. 32 3/8" (seat), D. 20 3/4" (seat). (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This armchair was part of a suite that included several side chairs and probably a matching armchair. Several of the side chairs are at Wyck, the Germantown home of Caspar Wistar. During the battle of Germantown, the British used Wyck as a field hospital, and the chaos of that episode is, by family legend, responsible for the rough condition of the side chairs. An armchair from the shop that produced Wistar’s suite is depicted in Thomas Hicks’s painting of a kitchen interior (fig. 68).

Peter Cooper, The Southeast Prospect of the City of Philadelphia, ca. 1720. Oil on canvas. 20" x 87". (Courtesy, The Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Armchair, Philadelphia vicinity,Pennsylvania, 1715–1730. Maple and ash. H. 48", W. 21 1/2", D. 18 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right rear post of the armchair illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pair of side chairs, Philadelphia vicinity, Pennsylvania, 1715–1730. Maple and ash. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Pook and Pook.)

Detail of the left front leg of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

High chest attributed to John Head, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1719–1732. Red cedar with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 70 7/8", W. 43 3/8", D. 23 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right front leg of the high chest illustrated in fig. 9. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1725. H. 30", W. 34", D. 20 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) As on the Wistar dressing table (fig. 2), the turnings of the drops echo passages of the legs.

Detail of the left front leg of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia or Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1720–1740. Walnut. H. 40 3/8", W. 19 3/4", D. 16". (Courtesy, Primative Hall Foundation; photo, Lazlo Bodo.)

Couch, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1715–1725. Maple with oak and unidentified secondary woods. H. 38 1/4", W. 24 1/2", L. 69". (Private collection; photo, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The bannisters of the back are molded with a sash plane, a creative adaptation by the maker. These tools were among the earliest dedicated sole planes to be used in Philadelphia, as they were essential for making double-hung windows.

Couch, probably Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1725–1735. Maple. H. 37", W. 23 1/4", L. 69 1/4". (Courtesy, Wright’s Ferry Mansion.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1730. Maple; remnants of original red paint. H. 48". (Courtesy, Philip Bradley Antiques.)

Windsor armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745–1765. Maple and tulip poplar with unidentified hardwoods. H. 17", W. 27 1/2", D. 20". (Courtesy, Philip Bradley Antiques.) Philadelphia Windsor chairs, employing this turning, were successful trade items in coastal shipping and became the archetypal model for the Windsor chair, supplanting the British version.

Gateleg table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1720–1725. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 28 1/4", top: 51 5/8" x 41 1/4" (open). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Turnings similar to those on this table occur on sophisticated Philadelphia work as late as the 1730s and on simple urban and vernacular furniture, particularly Germanic objects, throughout the eighteenth century.

Dressing table, probably from the shop of Joseph, George, or Josiah Claypoole, 1725–1745. Walnut with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 29", W. 34 1/2", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.) The small astragal drops and arches of the front rail are typical of the Claypoole family’s work.

Chest-on-stand, possibly from the shop of Joseph Claypoole, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1715–1725. Mahogany with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 25 1/2", W. 18 5/8", D. 9". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest-on-stand, possibly from the shop of Joseph Claypoole, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1715–1725. Mahogany with white cedar, oak, and yellow pine. H. 26", W. 17", D. 9". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left rear leg of the chest-on-stand illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the chest-on-stand illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the secret compartment in the center drawer of the chest-on-stand illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Stand, possibly from the shop of Joseph Claypoole, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1715–1725. Walnut. H. 28 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pillar on the stand illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Gateleg table, possibly made by James Bartram, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1725. Walnut and mixed wood inlays with chestnut. H. 30 3/4", top: 70" x 60" (open). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table, possibly made by James Bartram, Chester County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1725. Walnut and cherry. H. 27 1/8", Diam. 31 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the iron plate under the hexagonal block of the tea table illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pillar and hexagonal block of the tea table illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pillar of a ca. 1770 Philadelphia candlestand. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Ireland, 1730–1745. Mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (The Knight of Glin and James Peill, Irish Furniture: Woodwork and Carving in Ireland from the Earliest Times to the Act of Union [New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007], p. 205, fig. 14.)

Side chair, Ireland, 1730. Walnut. Dimensions not recorded. (The Knight of Glin and James Peill, Irish Furniture: Woodwork and Carving in Ireland from the Earliest Times to the Act of Union [New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007], p. 73, fig. 87.)

Side chair, Portugal or Brazil, ca. 1755. Jacardana. H. 52", W. 23", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Carlton Hibbs, LLC.)

Ganging posts from a walnut board. (Photo, Michelle Williams, Jeffrey Williams Furniture Maker.) These posts are for two reproduction armchairs like those made in the shop that produced the Wistar armchair (fig. 3).

Sawing the posts of an armchair like the Wistar example (fig. 3). (Photo, Michelle Williams, Jeffrey Williams Furniture Maker.)

Laminating the posts of an armchair like the Wistar armchair (fig. 3). (Photo, Michelle Williams, Jeffrey Williams Furniture Maker.)

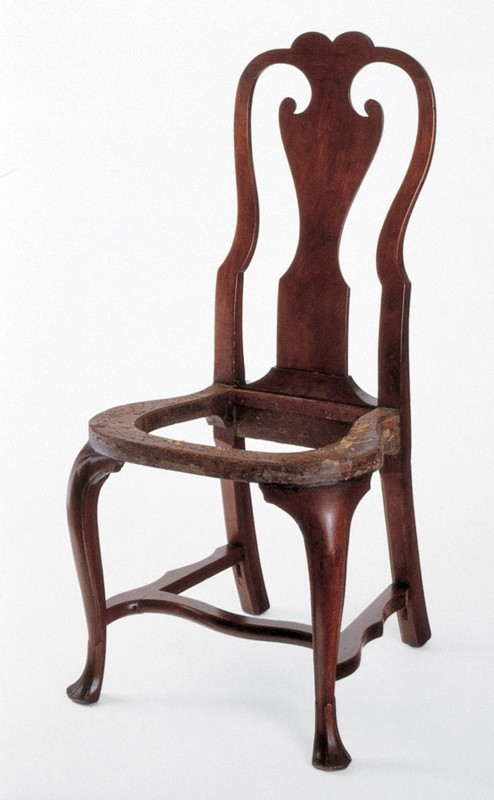

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1750. Walnut with walnut and yellow pine. H. 42", W. 21 1/4", D. 20 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The procedural shots left show how the front and side seat rail moldings were cut from the front and sides of the slip seat frame.

Detail of the seat rail and leg joinery of the armchair illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Wedged through-tenon of an armchair like the Wistar example (fig. 3). (Photo, Michelle Williams, Jeffrey Williams Furniture Maker.)

Clamping the stiles and crest of an armchair like the Wistar example (fig. 3). (Photo, Michelle Williams, Jeffrey Williams Furniture Maker.)

Detail showing the shaved crest and right rear stile of the side chair illustrated in fig. 61. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1750. Walnut with walnut and yellow pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Caxambas Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1750. Walnut with walnut and yellow pine. H. 42 3/4", W. 32 1/4", D. 24". (Courtesy, Dietrich Americana Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1750. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 41", W. 16 1/4" (seat), D. 18 1/2" (seat). (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1925; Art Resource, NY.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1755. Walnut with walnut and yellow pine. H. 42 1/8", W. 20 1/8", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1755. Walnut. H. 41". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to Edward Wright, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1749 or 1735–1750. H. 40", W. 19 3/4", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Philip Bradley Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A label glued to the inner surface of the back rail states that the chair was “[mad]e by Edward Wright, living between Che[stnu]t and Market street in fourth Street, the _0 day of May 1749 Philadelphia, Pa.” Another label glued to the bottom of the front rail reads, “These chairs were the property of Robert Montgomery, (2nd) of Eglinton, Upper Freehold, Monmouth Co. belonged originally to th 2nd. Elisa Lawrence of Chestnut Grove Monmouth Co. New Jersey from whence they were bought [brought] Jonathan.” Although these notations are not period, they are specific enough to suggest that at least part of the information was taken from an earlier document. It is conceivable that Wright was the master of the shop that produced the Wistar armchair, but it is more likely that he worked as an apprentice there and continued to produce chairs identical to those he learned to make during his training.

Oblique and rear views of the armchair illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1725–1740. Walnut. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Caxambas Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair has a solid walnut splat, and none of its components is veneered.

Settee, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Walnut. H. 45 3/4", W. 56 1/2" (seat), D. 21 1/2" (seat). (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1925; Art Resource, NY.)

Easy chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 47 1/2", W. 33 3/4", D. 28". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.)

Desk-and-bookcase, possibly from the shop of Stephen Armitt, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Mahogany and exotic hardwoods with white cedar, oak, and tulip poplar. H. 94", W. 34 3/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Walnut and walnut veneer with yellow pine. H. 39 1/2", W. 25", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1745. Walnut and walnut veneer with walnut. H. 40", W. 20 1/2", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Wright’s Ferry Mansion.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1745. Walnut and walnut veneer with unidentified secondary woods. H. 40 1/2", W. 19 7/8", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1750. Walnut with walnut and yellow pine. H. 42 1/2", W. 24", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1750. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 39 1/4", W. 29 1/2" (arms), D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Rear view of the armchair illustrated in fig. 58. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The maker of the armchair must have seen an example from the shop that produced the Logan settee and related seating forms. The very large, solid, and nonlaminated rear stiles mimic those of chairs from the Logan settee shop with considerable skill and understanding, including the inward haunch of the leg under the rear rail.

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1759. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 42 1/2", W. 20 1/8", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1760–1765. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 40 3/4", W. 20 1/8", D. 19 3/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, lent by the Commissioners of Fairmont Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 61. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table attributed to the shop of John Head, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Mahogany and maple with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 30", W. 33 1/2", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although very much in the style of John Head, the drawer construction of the dressing table differs from his earlier, documented work. This may reflect the presence of a new craftsman in his workforce when this dressing table was made.

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1745. Mahogany with yellow pine and white cedar; clouded limestone. H. 32 5/8", W. 42", D. 23 1/8". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table, Rappahannock River valley, Virginia, 1745–1765. Walnut. H. 29", W. 38 3/4", D. 23 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table is one of three nearly identical examples, one of which descended in the Beverly family of Essex County, Virginia.

Dressing table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1750. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine and white cedar. H. 29 1/2", W. 33", D. 20 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Philip Bradley Antiques.)

Easy chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with oak and tulip poplar. H. 46", W. 45" (arms), D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Bill Jacobs.) The non-cabriole back-sweeping rear leg remained the standard for Philadelphia chairs through the rococo era. In Britain, cabriole rear-leg use continued along with this leg design.

Thomas Hicks, Kitchen Interior, possibly Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1865. Oil on panel. 23" x 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation.)

On April 14, 1726, Caspar Wistar commissioned John Head to make a walnut high chest and dressing table. This suite represents the pinnacle of the late baroque style in Philadelphia cabinetmaking (figs. 1, 2). Wistar was a German immigrant who had become a successful button maker and businessman in Philadelphia since his arrival in 1717. By 1726 he was a naturalized citizen who spoke and wrote English, had become a Quaker, owned property, and was involved in several business ventures with fellow Quakers, including part ownership of Abbington iron furnace. When he placed his order for the Head suite, he was preparing to marry Catherine Jansen, the daughter of a Dutch-German Quaker justice of the peace, and the two wed the following month.[1]

Wistar’s wealth increased dramatically during the 1730s, largely owing to successful land speculation. Probably in that decade, he acquired a set of seating furniture that included at least one armchair (fig. 3). The chairs could be as little as seven to ten years later than the high chest and dressing table, but the differences in design and tool use between these groups of furniture are so striking they raise several questions: How did this profound stylistic shift occur in such a short time? How did an early example of this new style capture its possibilities so succinctly? How was such a total change in tool use and working method accomplished, and why was this new style so readily accepted?

Cultural Diversity and Creolized Design

During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Philadelphia was one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse cities in colonial America. Originally envisioned as “a greene Country Towne, which will never be burnt, and always be wholesome,” Philadelphia was central to William Penn’s “holy experiment.” From the outset, he endeavored to create a sanctuary for persecuted Quakers as well as members of other sects. Penn believed that religious tolerance, political harmony, and economic opportunity would promote brotherhood and peace, and that with God’s blessing his colony would become “the seed of a nation.”[2]

In The Voyage, Shipwreck and Miraculous Escape of Richard Castleman, Gentleman, with a Description of Pennsylvania and of the City of Philadelphia, the author noted, “all Religions are tolerated here, which is one Means to increase the Riches of the Place.” Quakers from several countries, Anglicans, Catholics, Pietist and Lutheran Germans, Huguenots, Scottish and Northern Irish Presbyterians, members of several other Protestant denominations, and Jews all lived in Philadelphia when Castleman arrived in 1726 (fig. 4). The German population had grown substantially after Francis Daniel Pastorius’s purchase of fifteen thousand acres from Penn for the establishment of Germantown in 1683. Penn’s agent, James Logan, also promoted religious and cultural tolerance and encouraged settlement by various ethnic groups. An Irish-born Quaker of Scottish descent, Logan served as mayor of Philadelphia, agent to the Penn family, and later acting governor of Pennsylvania. During his tenure as mayor, he allowed Irish Catholics to hold the first public mass in Philadelphia. Swedes and Dutch were also present in and around the city at an early date, and both free and enslaved blacks lived and worked there. In many respects, Philadelphia’s cultural diversity during this period can be compared with that of New York and Charleston and contrasted with that of Boston, a relatively homogeneous city with less immigration and a dominant religion.[3]

The cultural diversity of Philadelphia’s woodworking community is well documented in the historical record. Immigrant craftsmen who worked during the period when the late baroque style flourished included joiners Joshua Baker (Ireland, 1713–1726), Thomas Betson (possibly London, before 1736), John Bird (probably London, before 1717), John Budd (probably London, 1694–1704), James Chick (County Devon, Eng., 1683–1699), Joseph Claypoole (County Cambridgeshire, Eng., ca. 1705–1744), Edward Evans (possibly London, before 1704–1717), William Fisher (County Hereford, Eng., 1684–1711), Aaron Goforth (Southwark, London, 1711–1736), Richard Grove (Plymouth, Eng., 1685–1710), John Head (Suffolk, Eng., 1717–1753), Jacob Levering (Holland or Germany, 1717–1753), William Moore (Waterford, Ireland, 1713–1717), Charles Plumley (Somersetshire, Eng., 1698–1708), and John Widdifield (Yorkshire, Eng., 1705–1720). The origins of many woodworkers active during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century are unknown, and some remain anonymous, as exemplified by the “Dutchman, A Joyner and a Carpenter” who worked for William Penn in 1685. The same can be said of early turners in Philadelphia, although the origins of several immigrant craftsmen who worked in that trade have been identified: William Carter (Wrapping, Middlesex, Eng., before 1695–1700), Johann Keim (Germany, 1707–1754), William Moore (Stafford, Eng., 1705–1711), Isaac Shoemaker (Cresheim, Germany, 1678–1733), Jacob Shoemaker (Mainz, Germany, 1683–1722), and Peter Shoemaker (Cresheim, Germany, 1685–1740). Decorative arts scholar Desiree Caldwell estimated that twenty-one of the seventy-four turners and chairmakers active between 1681 and 1755 were of German origin or ancestry.[4]

Immigrant influences are also apparent in late baroque furniture made in and around Philadelphia. The armchair illustrated in figure 5 is part of a group of chairs distinguished by having stretcher turnings first used in French seating during the reign of Louis XIII and persisting for two centuries in areas of French cultural influence, including Québec. The likely vector for the arrival of this design is immigrant, Huguenot craftsmen. One candidate is Solomon Cresson, who was born into a French Protestant family, converted to Quakerism, and moved from New York to Philadelphia, where he worked from circa 1699 to 1746.[5]

The rear stiles of the armchair are more idiosyncratic than the stretchers. On most turned chairs of this period, the narrowest passages of any spindle turning are either roughly the same diameter, or they taper regularly as the turning ascends, as on the front posts of this example. The turner of the armchair deviated from the norm in using a narrow columnar passage in the middle of the rear posts (fig. 6). This element provides visual release from the tension created by the oversize, flaring collars, ovoid elements, and compressed balusters above and below. He used the same combination of elements on other turned seating, including the side chairs illustrated in figure 7. Certainly not Anglo in derivation, yet not quite French, these chairs are creolized forms and among the best representations of early Philadelphia turning.[6]

Although the maker of the armchair has not been identified, the history of the Cresson family shows how tradesmen became connected through religion and marriage and suggests paths through which creolized designs might have emerged. Solomon’s grandfather Pierre was a Huguenot who fled to Holland “at the time of the Reformation,” immigrated to America in 1657, and settled in Harlem, New York. Pierre and his son Jacques, who was Solomon’s father, were members of the Dutch Reformed Church, but Solomon became a Quaker. Solomon learned the chairmaking trade in New York, which had a considerable Huguenot population, before moving to Philadelphia. He married Anna Watson in the Philadelphia Friends Meeting on November 14, 1702, and died in the city on October 10, 1746. Before his death, Solomon left his son James “a house and lot on the west side of Second Street, below market.” James’s trade is not known, but he may have been a chairmaker. On March 25, 1738, he married Sarah Emlen, whose brother Caleb was a chairmaker.[7]

Religious ties must have been one of the principal catalysts for creolization in early Philadelphia decorative arts. Some members of the Shoemaker family, which included first-generation émigré turners, had embraced Quakerism before their arrival. Jacob Shoemaker arrived on the ship America in 1683 and was involved in Pastorius’s plans for Germantown, which the latter hoped to “arrange...in the Good High German manner.” In 1719 Shoemaker, his wife, Margaret, and their children, Thomas, Jacob, and Susanna, transferred from Abington to the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, which at that time included British émigré turners and joiners like John Head. Considering the fact that Quaker craftsmen often took apprentices from the families of other Friends, which presumably included those of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, it is easy to see how creolized styles could have emerged.[8]

Quakers, who controlled the legislative assembly until 1754 and remained influential long after, dominated the city’s politics. They also had a profound influence on furniture design and construction. Quaker taste, famously described as favoring products that were “of the best sort, but plain,” accepted varied design and good craftsmanship but shied away from ornament that they considered ostentatious. This may explain the near absence of carving and veneering in surviving Philadelphia furniture in the late baroque style.[9]

For Quakers, veneered furniture represented “a false show of vanity” because it was superficial. Solid figured woods were acceptable, as was the somewhat later practice of veneering a figured hardwood like walnut or mahogany on a core of the same species. By the 1740s some cabinet shops were making two models of the same case form: one with figured facings (a laminate the thickness of the fillet and lip on lipped drawers) or veneers (for cock-beaded drawers) on softwood cores, presumably for non-Quakers; and one with solid drawer fronts or drawer fronts with figured faces or veneers on cores of the same wood, which would have been acceptable to Quakers.[10]

The Late Baroque Style in Philadelphia Furniture

In the English-speaking world, late baroque decorative arts are generally associated with the reign of William III, but the style originated in the court of Louis XIV of France and spread throughout much of Europe and Great Britain. The leading herald of this taste was Daniel Marot, the Huguenot designer who fled to the Netherlands after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and accompanied William of Orange to England in 1694. Exuberant and restless, the late baroque style is expressed in curved outlines and scrolls; elements that project into space; robust turnings; and the use of highly figured veneers, gilding, japanning, and carving. It was primarily through lathe-produced elements, often in combination with components sawn with scrolled edges, that the Philadelphia version of this style found expression, although design principles common to most furniture—ratio and proportion, graduation of elements, design and placement of hardware, choice of wood, and molding size and configuration—all naturally played their parts. The molding plane with a dedicated sole was not yet in common use. Craftsmen typically produced moldings using hollow, round, and rebate planes for larger examples, and scratch-stocks for smaller moldings.[11]

Philadelphia turning in the late baroque style is more varied than that of any other American urban center. The extensive design vocabulary of the city’s early turners and the demand for their work are reflected in furniture attributed to John Head. The turning associated with his shop is individualistic, and either he or one of his craftsmen appears to have produced nearly all of the surviving work. Head purchased a small quantity of turned piecework from Joseph Chatham and Alexander Foreman, but the values noted in his account book were relatively insignificant in relation to his known production. The corner legs on Head’s case furniture tilt slightly outward, whereas those on corresponding forms by other cabinetmakers are vertical, and his turnings are more creative and visually exciting than most. The graceful ogee element capping the trumpet-shaped passage on the legs of the Wistar dressing table is repeated in larger form on the turned feet and, in miniature, on the drops of the skirt (figs. 2, 8). This type of resonance is a hallmark of Head’s design. The cyma curves of his beautifully conceived stretchers echo the turnings and the scrolled lower edges of the rails. A diamond plaque conceals the intersection of the stretchers, and neatly executed square pads punctuate each of the upper leg joints.[12]

The Wistar high chest has a relatively conventional stretcher arrangement, but other compositional devices elevate its design and visual appeal (fig. 1). Head made the drawer fronts of spectacular figured walnut and book-matched the two in the center of the upper case, mimicking an effect usually accomplished with veneering. The front legs and lower edges of the front rail frame three areas of rhythmic negative space, each of which rises to an ogival arch. The brasses on the lower drawers are centered on the apex of each arch, another detail that captures the eye.

For the high chest illustrated in figure 9, Head employed almost all of the design options available at that time. This object represents the apogee of the late baroque style in Philadelphia furniture, surpassing all of the known scrutoires and desk-and-bookcases of the period. The primary wood is an exotic—a non-native red cedar (Juniperus sp., probably Juniperus silicicola). During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this fragrant wood was associated with the biblical cedar of Lebanon and was valued as highly as mahogany. The drawer linings are also made of red cedar, although probably the local variety Juniperus virginiana. Philadelphia inventories occasionally list cedar furniture, as indicated by a “Case of Red Sedar Drawers” valued at £5 in 1711 and a “Cedar Case of draws and Table do.” valued at £8 in 1714.[13]

The cedar high chest is Head’s only known example with a full Ionic cornice, a pulvinated frieze (the front section is a drawer), and arcaded, molded stretchers. Most of the stretchers on high chests of this era are horizontally configured, lap-joined at the corners, and drilled to receive the lower round tenons of the legs, which extend through the holes and then into holes bored through the feet. This design is relatively easy to make, but stretchers of this type, being horizontally configured, do not interact with the curved design of the bottom of the rails as dramatically as the vertically oriented stretchers of the cedar high chest. Head went to a great deal of effort to achieve this effect, which also created negative spaces more complex and visually exciting than those on the Wistar high chest.

With twelve mortise-and-tenon joints for the stretchers and legs, the base of the cedar high chest probably required about three times as much labor as the base of a standard model. Head also used two different moldings to add emphasis to the stretchers: a bent, beaded edge molding on the upper edge (corresponding to the molding on the lower edges of the rails above); and a curved ogee molding, made with a scratch-stock, on the lower edge and adjacent leg stiles (fig. 10). To the leg stock he added four laminates to gain the extra thickness necessary to produce the boldly projecting passage of turning.

Head’s account book mentions three cedar high chests, one of which must be the example illustrated in figure 9. On April 15, 1719, he charged pewterer Simon Edgell £10 for a cedar high chest and dressing table; on March 13, 1724, Head sold James Steel a “Sader Chest And Table of drawers” for £9.10.10; and on October 6, 1732, Anthony Morris paid the cabinetmaker £13.10 for a cedar high chest and dressing table. The charge for Wistar’s furniture was £10, which included an oval (gateleg) table, indicating that these cedar forms were the most expensive examples made in Head’s shop.[14]

One of the most visually powerful Philadelphia objects in the late baroque style is a dressing table from the shop of one of Head’s competitors (fig. 11). It has unusually exuberant turned legs and the most complex stretchers surviving on any colonial example of that form. The giant inverted cups of the legs are separate components (fig. 12). Each has a hole bored in the center (probably a tail stock boring on the lathe, which would have produced a hole exactly on the central axis) to accept a round tenon turned on the end of the baluster above and tapering cone below. Philadelphia craftsmen used this same method of stacking joined, turned elements, which conserved wood, in the production of urn-and-leaf and urn-and-flame finials as late as the 1790s.

The scrolled stretchers are the most striking and unusual design feature of this dressing table. The larger curved elements are formed with noncongruent arcs—thicker in the middle and thinner on the ends—creating a sense of tension and momentum and making the negative space between the stretchers read as being more charged and taut than it would be if the arcs were congruent. The stretchers are a tour de force of flat scrolled elements unrivaled in American furniture of this era. Chair crests and arms and the lower edges of the rails of case pieces were other areas where the use of flat, scrolled decorative elements produced dramatic results (fig. 13).

The Art of the Turner

During the 1710s and 1720s the cultural and economic environment in Philadelphia encouraged creative design. “Memorial to William Penn,” a 1729 poem by almanac publisher Titian Leeds captured the optimism of the time:

Stretch’d on the Bank of Delaware’s rapid Stream

Stands Philadelphia, not unknown to Fame:

Here the tall Vessels safe at Anchor ride.

And Europe’s Wealth flows in with every Tide:

Thro’ each wide Ope the distant Prospect’s clear;

The well-built Streets are regular fair:

Thy Seers how cautious! And how gravely wise!

They hopeful Youth in Emulation rise:

Who (if the wishing Muse inspir’d does sing)

Shall Liberal Arts to such Perfection bring,

Europe shall mourn her ancient Fame declin’d

And Philadelphia be the Athens of Mankind.

Leeds’s references to wealth and prosperity were echoed by James Logan, who wrote, “Riches have been shewn, to be the natural Effects of Sobriety, Industry, and Frugality.” Logan commissioned furniture from the city’s leading craftsmen and purchased British seating furniture, including cane chairs and “Leather Chairs,” the latter from his London agent, William Askew. Imported chairs and tables represented another potential influence on Philadelphia turning styles.[15]

In no other area of Philadelphia decorative arts was the late baroque style revealed more forcefully than in turning. The craftsman who made the turned components for the couch illustrated in figure 14 used unusually heavy stock for the legs and stretchers. The arrangement of elements on more conventional Philadelphia couches (fig. 15) became the standard for Philadelphia ladder-back chairs (fig. 16) and, later, Windsor chairs (fig. 17). This turning was also adaptable to joined furniture through the employment of square sections to receive rails with rectangular tenons rather than cylinders to receive turned stretchers or seat lists with round tenons.[16]

It is impossible to assign cultural origins to most Philadelphia turnings because they feature elements that can be found on earlier and contemporaneous work from Britain, Holland, and Germany. Yet, as the products of creolization within a specific historical context, some turning designs can be considered quintessentially Philadelphian. The most common pattern consists of a torus with shoulder surmounting a baluster, one or two scotia and torus elements, and occasionally a ball or urn below (fig. 18). Variants of this design occur on a wide range of Philadelphia furniture forms, including gateleg tables, stretcher tables, joint stools, dressing tables (fig. 19), and chest-on-stands.

Two miniature chest-on-stands (figs. 20, 21), one with a history of descent in the Morris family (fig. 20), may represent the work of Joseph Claypoole, who worked in Philadelphia from circa 1710 until the late 1730s and trained his sons Josiah and George. Both objects are made of mahogany, which was imported into Philadelphia as early as 1701 but used much less frequently than walnut for furniture in the late baroque style. The chest-on-stands predate the Wistar high chest and dressing table and have upper-case drawers configured more like those of a spice, or valuables, chest than a standard high chest. Their legs have conventional mortise-and-tenon joints where the square sections of the legs and rails meet and, as noted on the Wistar dressing table, bored and round-tenoned joints securing the legs, stretchers, and feet. The legs of the Morris chest are laminated, which suggests that the maker did not have stock thick enough to turn them from single pieces. Despite this obstacle, the turner created a masterful design. The crisp torus and scotia turnings at the base of each leg create rhythm and tension that find release in the gently curving baluster above (fig. 22). Typical of early Philadelphia work, the baluster diminishes without re-curve and ascends to another torus and scotia that resolve to the astragal under the square.[17]

The upper cases of the chest-on-stands are made as a single unit; their top and bottom boards extend beyond the sides to form partial cornice and waist moldings respectively (fig. 23). Both have vertical drawers in the center of the façade; the one on the Morris example features an elaborate secret drawer (fig. 24). The back of the vertical drawer slides in a dovetail joint that is virtually invisible when closed. This is superbly conceived and executed craftsmanship done on a miniature scale with the same precision as full-size work.

Stands and single-pillar tables were the perfect theater for turners to perform their work because the only joints are at the top and bottom. The pillar of a stand with an octagonal top and Flemish-scroll legs is almost certainly by the turner who made the legs of the miniature chest-on-stands (fig. 25). Many of the elements on those objects are the same, although those on the stand are strengthened, heightened versions made possible by the larger dimensions of the stock (fig. 26). The stand is a tour de force of spindle turning. The only colonial work that approaches it are the half-columns and colonnettes on a group of mannerist furniture from an anonymous Essex County, Massachusetts, shop.[18]

Philadelphia turning had a strong influence on southeastern Pennsylvania work, particularly in areas where artisans and consumers from that city relocated. Turning sequences related to those on the gateleg table, chest-on-stands, and stand illustrated above can be observed on a gateleg table made for James and Elizabeth (Maris) Bartram in 1725 (fig. 27). James, who was described as a joiner the following year, would have to be considered a candidate for the maker. The artisan who produced the legs and stretchers also turned the pillar of the tea table illustrated in figure 28. The maker of the tea table joined the shaft and legs to a hexagonal block and reinforced them with an iron plate, commonly referred to as a “spider,” presaging later examples of the form. The plate, which is thicker than that found on later examples, is cut to receive the round tenon at the bottom of the pillar tenon and fastened with large wrought nails (fig. 29). The maker created a visual link between the different components of the base by making the sides of the hexagonal block concave and molding the top in two stages to lead it up to the turned pillar (fig. 30). This method of block construction was soon supplanted by the familiar system of attaching the legs directly to the pillar with sliding dovetails, but most of the salient design and structural features that persisted through the eighteenth century—use of a birdcage and attachment of the top with battens—are present on this early table.[19]

Although styles changed and lathe work became less important in the production of Philadelphia high-style furniture, the city’s turners found other venues for their craft: the manufacture of components for inexpensive chairs, inexpensive stands, stools, tables, and for architecture, and ships—to name but a few. When called on to supply piecework for sophisticated objects, as exemplified by the pillar of the candlestand illustrated in figure 31, Philadelphia turners often displayed remarkable sophistication and fluency. Thus, even after the baroque style ended, Philadelphia was a good city in which turners could ply their trade.

An Upheaval in Design and Technology

The armchair that Caspar Wistar acquired a few years after purchasing the high chest and dressing table could hardly be more different from those case forms (figs. 1–3). This difference is just as obvious if the armchair is compared with earlier turned chairs or wainscot chairs, which are essentially rectilinear forms employing many of the design and construction features of joined chests. None of the components of Philadelphia baroque furniture curves in more than one plane. In contrast, most of the components of the Wistar chair—front legs and knee blocks, rear legs/stiles, arms, arm supports, crest, and splat—curve in two different planes. Almost all these components are rounded, and the maker shaped them after they were sawn. Indeed, much of the shaping was done post-assembly, which represents a radical departure from earlier chairmaking practices.

This shift in style and technology required specialized tools, some of which were not in the kits of earlier joiners, cabinetmakers, and chairmakers. In the May 23, 1751, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, hardware merchant Thomas Maule listed “drawing knives...spoke-sheaves, shoe knives, pinchers, nippers, rasps, awl-blades,...most sorts of chisels, gouges, plain-irons, files, center-bits, douelling ditto, chair-makers bitts,...augers,” and other tools of the cabinetmaking and chairmaking trades. For the purpose of this essay, the most important tool mentioned by Maule was the spoke-shave, which has been aptly described as a “marriage between a draw-knife and a plane.” Spoke-shaves were present in the woodworking trades long before chairs like the Wistar example came into fashion, but their use had been primarily for the manufacture of tools (rakes and other tools with round handles) and wheels (spokes) as well as some aspects of ship work. Before the advent of cabriole legs and other curved components, spoke-shaves had limited use in the furniture-making trades.[20]

The maker of the Wistar chair used a spoke-shave to produce all of the rounded curves, including those on the cabriole legs. Square-sectioned cabriole legs, like those on the dressing table illustrated in figure 64, were the only variants that obviated the need for that tool. As the arms and arm supports of the Wistar chair suggest, the spoke-shave was the tool best suited to producing all of that form’s rounded curves as well as those on side chairs and other seating of this genre.

Several specialized tools were also used in the manufacture of the Wistar armchair. A scratch-stock with a sole adapted to travel on curves of fairly small radius was required to produce the bead on the outer edges of the rear stiles and crest. Similarly, the tool referred to by Maule as a “douelling” bit was used to produce the round tenon on the top of each front leg, and the “chair-makers” bit was used to produce the round mortise that received the tenon. The majority of Philadelphia compass-seat chairs in this style have similar joints at the front. When the legs of such chairs are disassembled, their tenons are invariably quite regular and show no sign of having been turned on a lathe. After being roughed out, the tenons were trued into round with a “chair-makers” bit—a hollow auger that was spun by hand and worked like a pencil sharpener. The bits that Maule sold undoubtedly came in pairs of the same diameter as the rule joint planes that made the joints of table leaves at this time.

The tools and techniques used to produce chairs like the Wistar example were probably introduced by chairmakers trained in the new style rather than being improvisations by earlier Philadelphia craftsmen. This shift in chair design and construction was abrupt and total rather than evolutionary. It was the product of a new workforce. Its catalyst was immigration.

A Refuge from Poverty and Misery

On August 7, 1729, the American Weekly Mercury reported, “there is arrived [in New Castle, Delaware, a port serving Philadelphia] this last Week about Two Thousand Irish, and abundance more Daily expected; There is one Ship that about One Hundred Souls has Died out of her.” During the 1720s and 1730s, life for the Irish working poor was harsh. Rent levels set under William III had expired and the new levels, which were often 30 percent to 60 percent higher, were more than tenant farmers could afford. Three consecutive years of bad harvests (1726–1728) brought famine and economic desperation. Immigrants sought to escape the deplorable environment described in a newspaper account published in Philadelphia:

tis almost incredible that any Christian Country could afford so Melancholy a Prospect as was presented to me the other Day when I rode up through the Country, and saw the Swarms of Poor which crowded along the Roads, scarce able to walk, and infinite Numbers starving in every Ditch in the midst of Rags, Dirt and Nakedness, which methought was enough to move the most obdurate heart. I call’d in at several Cabins, which for the most part were waste, but the Poor House-keepers chore to keep their little Tenements rather than beg with their poor Children, who made a miserable Figure, perplexing the poor Father and Mother on every Side with hungry Cries. Tis with no little Concern that I tell you of their Complaints of the...Landlords, whose great Oppressions the poor Creatures represented with vehemence of Expression and Hearts ready to burst....The Griping Avarice of the Landed Gentlemen in raising or Rents, has in great Measure contributed to the Ruin of many Farmers, who were able to help the Poor, are now themselves become Beggars, or gone to remote Islands to avoid the common Calamity.

Concerned over the numbers of German and Irish immigrants arriving in Pennsylvania, Philadelphia passed the Servant Act, requiring both a duty and a bond for each arriving servant. As Irish historian Maurice J. Bric observed, “Both pieces of legislation [the Servant Act and the 1722 Convict Act] had potentially serious implications for Irish emigration to the Delaware Valley. Yet, in some ways, they were self-defeating....Moreover, the laws could be evaded by landing passengers at the Delaware ports of Newcastle and Wilmington.”[21]

The number of Irish immigrants cited in the aforementioned American Weekly Mercury is staggering considering the population of the mid-Atlantic colonies was approximately 263,000 in 1730. James Logan, agent of the proprietors (Penn family), noted that year, “It looks as Irel(an)d is to send all its inhabitants hither, for last week not less than six ships arrived.” The Irish in that week alone would numerically represent 20 percent of the estimated British forces quartered in North America after the French and Indian War or half the British troops in Boston on the eve of the Revolutionary War. More important, the newcomers who debarked in Delaware were part of a wave of Irish immigration that had begun earlier. In 1727 Logan wrote, “we have from the north of Ireland, great numbers yearly, 8 or 9 ships this last...[fall] discharged at Newcastle.”[22]

Many Irish immigrants, even free journeymen, could pay for their passage only through indentured servitude. Indenture agreements were typically for periods of four to seven years (although some were as long as seventeen), and they conveyed few rights to the servant; however, such agreements offered those who signed on a chance to escape poverty, find employment, and, in some instances, reunite with family members who had immigrated earlier. Indentures could be sold, with the purchaser buying the unexpired time. Servants whose terms were purchased by speculators and ship captains became venture cargo. On November 21, 1728, the American Weekly Mercury advertised “a Parcel of young likely Men Servants” that had “just arrived from London, in the Ship Borden.” Among them were “Husband-men, Joyners, Shoe-makers, Weavers, Smiths, Brick-makers, Brick-layers, Sawyer, Taylors, Stay-makers, Butchers, Chair-makers, and several other Trades...to be sold very reasonable, either for ready Money; Wheat, Bread or Flour.”

Indentured servants constituted a substantial portion of the labor force in colonial America. Advertisements for runaway servants in Philadelphia newspapers document the presence of Irish immigrants indentured to local craftsmen. In the January 18, 1733, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, joiner and chairmaker Stephen Armitt offered a 20s. reward for the return of “a Servant Man named Thomas Holt, aged about 21 Years, a likely well-set Fellow, an Irishman, with a good Head of Hair.” The following year carpenter Owen Owen and joiner Thomas Stapleford issued a joint appeal for the return of their servants. Owen’s servant James Roe was referred to as “Dublin born,” and Stapleford’s “Lad named Joseph Land” was described as being “18 Years old, of short stature, swarthy complexion, [and] thick Lips.” Carver Brian Wilkinson’s advertisement in the April 5, 1749, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette was more specific, noting both the nationality and trade of his servant:

Run away, on Monday last...an Irish servant man, named William Mooney, a little fellow, about twenty years of age, much mark'd with the smallpox, by trade a carver....Whoever takes up the said servant, and secures him, so that his master may have him again, if taken within ten miles of Philadelphia, shall have Fifteen Shillings reward, if further, Three Pounds, and reasonable charges.

Although it is impossible to quantify the influence indentured Irish craftsmen had on Philadelphia’s furniture-making trade, the presence of Irish details in that city’s seating, as well as in other furniture forms, suggests that it was substantial.[23]

Advertisements by Wilkinson and his father, Anthony, mention the nationalities of other runaway servants and provide a further glimpse into the cultural diversity of Philadelphia’s furniture-making community during the period when chairs like the Wistar example were fashionable. They also allude to the range of the Wilkinsons’ work and their stature among Philadelphia carvers. Runaways included John Nicholson (1734), “a Chair carver, and can speak a little Indian, having lived a Twelve month among those People”; John Forder (1750), a seventeen-year-old who was born in London; Lawrence Perkley (1754), “A Dutch servant man...by trade a Carver in wood and stone”; Matthias Luyker (1755), an eighteen-year-old who spoke “good English and Dutch”; and Charles (1752, 1757), “a Negroe Man” who fled twice and may have been a slave. If the Wilkinson shops can be considered typical of those operated by other Philadelphia craftsmen engaged in the furniture-making trades, Irish artisans like William Mooney likely worked side by side with indentured servants, free journeymen, and apprentices of other nationalities. This type of environment, which afforded opportunities for the exchange of designs and working methods, contributed to the production of creolized furniture.[24]

Irish Influences in Philadelphia Seating

American antique dealers Joe Kindig Jr. and David Stockwell were among the first scholars to recognize Irish influences in eighteenth-century Philadelphia furniture. Their observations were echoed and amplified by later decorative arts historians, including John Kirk, Jack Lindsey, James Peill, and Desmond Fitzgerald, 29th Knight of Glin. All cited stylistic details shared by Irish and Philadelphia chairs—trifid feet, paneled trifid feet, and slipper feet—but few delved into the structure of those objects. As the Wistar armchair reveals, most of the design vocabulary and many of the construction practices considered hallmarks of early cabriole leg chairs made in Philadelphia originated in Ireland.[25]

Irish cognates for the Wistar armchair and contemporaneous Philadelphia seating are abundant (figs. 32, 33), and common design features include compass seats with horizontally configured rails (the outer rail surfaces in Ireland are generally clad in vertically oriented veneer), rounded yoke or center shell crest rails, wavy H-shaped stretchers (when stretchers are used), non-cabriole and semi-cabriole rear legs, splats that are gently serpentine in cross section, and serpentine arms with curving arm supports. It is true that some English chairs of this era share one or more of these details, and English furniture was certainly shipped to Ireland, but all the features cited above occur on the majority of high-style Irish chairs from this time.

Many of the English Georgian chairs with horizontally configured seat rails are very early and do not have compass seats, or they have over-the-rail upholstery or cane seats. Cane seat chairs nearly always have horizontally configured seat rails because it is much easier to drill the many holes needed for the cane through the smallest dimension of the board. Much European seventeenth- and eighteenth-century seating furniture is derived, to some degree, from Chinese design—particularly Ming and Ming-style furniture. Chinese chairs generally have horizontally configured seat rails holding woven or panel seats (the probable origin of the European cane seat chair), frequently with vertically configured rails directly under the horizontal rails. European joined chairs typically were made with vertically configured rails, as that orientation provided more room for the mortise- and-tenon joints that fasten the rails to the legs and rear stiles; their seat rails typically tenon into mortises in the legs.

On chairs with horizontally configured rails, the front legs tenon into the rails from below. There are advantages and disadvantages to each method. If a chair design calls for rails curved in plan—looking down at the seat—with vertically configured rails, the amount of curvature of the seat rails is entirely dependent on the rails’ thickness. In contrast, when the three boards that comprise the side and front seat rails are configured horizontally, they are considerably wider than they are thick. This allowed chairmakers to make the compass seat with much more pronounced curves than they would have been able to produce if the rails were configured vertically. This fact alone accounts for the considerable difference in appearance between Philadelphia compass-seat chairs and those from other American cities, as well as most English chairs of this genre. Horizontally configured rails were used by Boston chairmakers for some early cabriole-leg easy chairs and, briefly, for over-upholstered back and elbow stools, but not for chairs with unupholstered hardwood seat rails.

Early Georgian Irish chairs with vertically configured rails and English chairs with slip seats and horizontally configured rails are known, but on Irish compass-seat chairs, horizontally configured rails are the rule, and on English chairs with slip seats, they are the exception. On English chairs with slip seats and horizontally configured rails, the front legs are often frontal—with knee blocks on opposite sides of the leg stock—instead of standard cabriole—with knee blocks on adjacent leg faces, as is generally the case for Irish chairs and nearly always the case for Philadelphia chairs. Chairmakers from other European nations also made cabriole-leg chairs with some of the features described above. Certain features on Irish chairs may have been influenced by Portuguese design. The Brazilian/Portuguese chair illustrated in figure 34 has non-cabriole rear legs, wavy H-stretchers, a splat that is serpentine in section, a rounded crest, and horizontally emphasized rails, although the rails appear to be joined into the legs. Objects like this suggest that the creolization of furniture designs and construction practices began in Britain and Europe and continued in the New World. As Irish historian Nicholas Canny points out, the Presbyterian Irish of Ulster who so frequently immigrated to Philadelphia were themselves the descendants of colonists from Scotland and England, although this fact did not prevent them from assuming an identity as fiercely Irish as their usually Catholic native neighbors.[26]

Early Cabriole-Leg Seating in Philadelphia: The Wistar Armchair Shop

The shop responsible for the Wistar armchair was one of the most important in Philadelphia, but there were several rival firms. All of these shops used Irish designs and construction techniques, but their end products are unmistakably Philadelphia. Several factors contributed to the development of that city’s distinctive style, including the convergence of designs and work habits introduced by immigrants of Irish descent, as well as those from areas of Britain and Europe, and the migration of journeymen from shop to shop.[27]

Several of the construction practices used by the maker of the Wistars’ armchair also appear in work from other Philadelphia shops. On most Philadelphia seating of this type, the rear stiles have the same serpentine profile as the splat (most evident when the object is viewed from the side), and the legs curve gently back below the seat rail. Makers used a bow saw to cut the posts that form the rear stiles and legs from a single walnut board (fig. 35). The boards were generally not thick enough to accommodate the innermost and outermost curves of the stiles as well, so makers glued up additional stock in those areas (figs. 36, 37). These laminations, which are often nearly seamless, were produced efficiently by using offcuts from the board that yielded the rear posts. The pieces cut from the face of the outside stile just over the seat were glued to the corresponding inner surface of the stile to supply the extra stock for the inward curve, and the pieces cut from the inner face of the stile just below the crest-rail joint to the outside face furnished the extra stock necessary for the outward curve. In each case, the glue surfaces of the laminate and stile were already prepared as glue joints by the initial smooth planing of the surfaces of the stock, and the laminates usually matched the grain of the main portion of the stile because they were cut from it. Lamination to accommodate such elevation curves can be seen on Irish and English chairs, although the advantage of using the offcuts as laminates is diminished if the stile faces are veneered, as frequently was the case in Europe. Veneering in this context is unknown in early Philadelphia seating.

The Irish method of simultaneously making slip seats and slip-seat moldings is also evident in the work of some Philadelphia shops. The artisan responsible for the side chair illustrated in figure 38 made the slip seat oversize then bow-sawed a thin band of its outer perimeter from the assembled frame. He glued that band to the upper face of the seat rails to form the slip-seat molding. If a chair with this type of construction has veneered rails, the only part of the molding that is visible when the object is in use is its top edge, so all that is required is that the front and side rails of the slip-seat frame, and thus the slip-seat molding, be made of the same wood as the show veneer of the rails. Several sets of Philadelphia compass-seat chairs have veneered seat rails, but that is the only context in which veneering was used on the earliest examples.[28]

For the manufacture of slip-seat moldings, the shop responsible for the Wistar armchair devised a creative technique that can be considered a Philadelphia-Irish hybrid. Craftsmen working there used stock that was heavy enough to produce both the front rail and the full thickness of its slip seat. They began by re-sawing the top face of the rail, removing a section thick enough to make the front of the slip seat. After constructing the slip seat (using primary wood sides and a secondary wood rear rail), they sawed the perimeter to produce offcuts for the seat-rail moldings as described above. Because the front of the slip seat/slip-seat molding assembly was made from the top of the board used for the front rail, the front rail and front slip-seat molding had continuous matching grain. The seat moldings appear to have conventional finger joints, but they are actually the outside edges of the haunched mortise-and-tenon joints of the offcut from the slip-seat frame. The haunched portion of the tenon on the side rail of the slip seat functions as the center “finger.”[29]

Philadelphia chairmakers of this era used two types of joints to secure front legs to seat rails. On most Irish and English chairs with horizontally configured rails, the front legs have an open-faced dovetail that extends through a lap or mortise-and-tenon joint, and the whole is covered by veneer. This joint was standard in one early Philadelphia shop and used intermittently in others, principally in the construction of certain models of compass-seat easy chairs, stools, and compass-seat side chairs with over-the-rail upholstery. On occasion, it was also employed for compass-seat chairs with unveneered rails, although surviving examples are scarce and the exterior of the joint presents a busy, sloppy appearance.

The round-tenon joinery of the Wistar armchair shop, and that of some competing firms, involved working the rear corner of the front leg stock into a cylindrical tenon with a “douelling” bit as described earlier, then fitting the tenon into a corresponding mortise bored through the rails with a “chair-maker’s” bit (fig. 39). This joint has the advantage of being invisible when a slip seat is in place (it does not interrupt the front surface of the seat rail), and it is faster and easier to make than a sawn and chopped dovetail mortise-and-tenon. Round tenons were typically glued and tightened with an end-grain wedge driven down from the top surface, which is the same technique Philadelphia cabinetmakers used when attaching the birdcage pillars of tripod-based tea tables and stands and turned feet to the legs of baroque high chests and dressing tables. No Irish chair examined for this study has round-tenoned front legs, nor has that feature been noted in any publications on Irish furniture. Round tenons were unnecessary for chairs with veneered rails, but they were used in the construction of birdcages in British tripod furniture and other through-tenon applications. The use of round tenons to attach the front legs of compass-seat chairs is likely another Philadelphia-Irish creolization invented to adapt to the local preference for unveneered seat rails.

Some scholars have suggested that Germany was the source of the round tenon joint in Philadelphia chairmaking. In her 1970 Winterthur thesis, Desiree Caldwell illustrated a German chair described as having those joints. However, that object has a trapezoidal seat frame and vertically configured rails, and from the accompanying illustration it is unclear whether it has round tenons or doweled leg repairs. Other scholars maintained that the wedging of round tenons (and wedged dovetails in casework) was indicative of Germanic work. Although many craftsmen of Teutonic descent were active in Philadelphia’s furniture-making trades, the practice of wedging tenons is much too generic to ascribe to any cultural tradition.[30]

The seat rail to rear stile (or post) joints of most Philadelphia chairs made between 1730 and 1780 have end-wedged through-tenons. Although some might argue that those joints are Germanic as well, end-wedged, through-tenons occur on furniture made throughout Europe and are even common in Chinese work. Practicality is the key to understanding this type of wedging. It is difficult to make a mortise-and-tenon joint in which the visible end of the tenon precisely fits the outer face of the through-mortised stock. Wedges are a simple solution because they spread the end of the tenon until it occupies all the space in the mortise. This process is easily adjusted by regulating how far the wedge is driven into cuts made in the end of the tenon, which required nothing more than a tap or two with a mallet or hammer (fig. 40).

Even when wedged from above, the round tenon joint is not particularly effective in preventing the legs from rotating. That explains why Philadelphia chairmakers used structural knee blocks. The blocks, which are usually the full thickness of the leg at the knee, are nailed to both the side faces of the legs and the undersurface of the seat rails. They served as support brackets that prevented the legs from racking or rotating and performed an important aesthetic function; they created a smooth transition from the curved legs to the seat rail and defined the negative space. The rear brackets glued to the underside of the side rails where they are through-tenoned and back-wedged to the rear posts are also structural. The brackets provide larger contact surfaces for the joints, which were subject to considerable stress during use.

Plugged mortises on the Wistar armchair suggest that its maker was experimenting to determine the optimal position for the front leg (fig. 39). The legs never occupied the inner mortises, as indicated by the absence of nail holes for knee blocks at those sites. It is difficult to believe this was a mistake; each side is the same and this shop did very exacting work, in many cases regulated by the use of patterns. A more likely scenario is that the maker of the chair was trying out a new leg placement and abandoned a design that would have situated the side knee blocks entirely under the front rail instead of partly on the undersides of the side rails. If the chair had been finished with the legs in the plugged positions, it would have appeared unstable, top-heavy, and poorly integrated. Since experimentation typically occurs at the beginning of the design/production process, the Wistar armchair may be one of the earliest examples by its maker.

On chairs from this shop, the inner corners of the front legs are relatively straight so the backs of the knees do not have much hollow re-curve. This was not a design flaw, as furniture scholar Albert Sack suggested; it was done to strengthen the round tenon at the top rear corner of the leg. The more the back of the knee is hollowed or in-curved, the weaker the tenon becomes; under extreme stress, the rear corner of the leg with the tenon can break away.

Chairs from this shop, as well as those of its competitors, were substantially shaped after they were joined and glued together. The outer corners of their crest rail mortises (those that receive the stile tenons) are slightly exposed. It would have been impossible to cut mortises consistently into preshaped crest rails; the tops of the mortises stop just short of the edge of the rail, which would have led to frequent breakouts. These chairs were glued together with the outer corners of the crests left square, then the square corners were shaped with bow saw, spoke-shave, and scrapers (fig. 41). If the chairmaker shaved just into the corner of the stile mortise, no harm was done. The square corners also made clamping the chair together simple. Many Philadelphia compass-seat chairs have circular impressions on the outer lower surface of the rear rail made by the clamps used to glue the crests and splats to the stiles and splat shoe. There are no corresponding impressions from clamps on the top of the crest because the square-ended corners where they would have been placed were cut away when the crest and stiles were shaped. The bead on the outer edge of the stiles and crest was worked with a scratch-stock after the final shaping was complete. For chairs with round rear stiles (fig. 42) much of the rounding also had to have been done after assembly.

The shop responsible for the Wistar armchair made several different versions of compass-seat chairs, including a wide example likely commissioned by a client of considerable physical stature (fig. 43). The maker appears to have used the same patterns for both objects but moved the edges out on the chair illustrated in figure 43 to achieve the additional width required for the wider example. On the earliest chairs from this shop, the inner line of the stile and underside of the crest moves into the upper C-scroll of the splat in an unbroken, continuous curve. For slightly later versions, the chairmakers added a small ogee shape at the top of the crest, above the C-scroll (fig. 44).

This shop also offered a variety of foot and crest options. Paneled slipper feet occur on the earliest chairs, but other variants include trifid, paneled pad, and (later) claw-and-ball. Three crest designs are known, one with a raised center, one with a raised center and a carved shell, and one of yoke design (fig. 45). On the latter, the perimeter bead is worked downward toward the splat in the center of the crest, a passage that must be carved since the scratch-stock cutter used elsewhere could only function moving parallel to the edge of the stock. Wavy H-stretchers were also an option (fig. 38). They are tenoned into oversize mortises and fixed in place with wedges driven from below. This type of stretcher integrates into the design of the chairs from this shop with remarkable effectiveness, whereas turned stretchers would have looked incongruous. Chairs with H-stretchers are stronger than those without stretchers, although the nearly straight inside knee line and thick structural knee blocks of chairs from the shop that produced the Wistar example did help prevent tenon breakouts from dragging and other forms of abuse.

All of the early chairs from the Wistar armchair shop are solid walnut. Their splats are generally made of figured wood, but not of vibrant crotch grain. The shop later began to use highly figured walnut for splats, some of which were veneered on walnut cores. The shop also introduced new, more complex splat profiles; trifid, faceted pad, and claw-and-ball feet; and carved volutes on crests (figs. 46, 47). Still, all of the elements on later models are either implicit in the original design—exemplified by the Wistar chair—or are extrapolations of it (fig. 48).[31]

The Wistar armchair shop produced some of the most harmonious seating designs ever made. Although simple in terms of embellishment, these objects are both subtle and complex. Their curved elements and negative spaces change from viewpoint to viewpoint (fig. 49). On armchairs like the Wistar example, the seat is convex from the front through the arm supports and concave from the arm supports to the rear stiles. The shape of the arm supports, an inversion of the cabriole leg with a knee-like break in the rear-facing curve just above the slip seat, appears to be a Philadelphia invention. No other arm support design for a compass-seat chair of this type is as successfully integrated into the overall composition of the object. Some Philadelphia makers used this arm support on chairs with trapezoidal seats, vertically configured rails, and straight or slightly outcurving stiles. In this application, the arm support still echoes the front legs but does not integrate as successfully with the back, whereas compass examples like the Wistar chair have supports that echo the curves of the stiles.

The arms are attached to the rear stiles with large screws inserted through the backs of the stiles into the end grain of the arms. The heads of the screws fit in countersunk holes that were plugged after assembly. The arm supports are similarly screwed through their lower outside surfaces into the side rails, and these countersunk screw holes are similarly plugged. These screws and the wrought nails used to attach the knee blocks and slip-seat upholstery are the only original iron components found on chairs from this shop. The iron braces found reinforcing the stile and crest joints on some chairs are repairs, although some scholars and dealers have misinterpreted this type of armature as being original. This type of repair is common on Philadelphia chairs with rounded crests and stiles and was often occasioned by the object tipping over backward. The joint between the crest rail and stile is prone to break because the mortises and tenons are relatively small and positioned right next to the end grain of the crest.[32]

Rival Shops

The shop that produced the Wistar armchair had several competitors, one of which produced the side chair illustrated in figure 50. With its undercut knees, legs attached to the seat rails with dovetail joints, and wavy H-stretchers, it is a very Irish-looking chair, albeit without the use of veneer. Although dating furniture from immigrant traditions can be problematic, this chair could be the earliest Philadelphia example with a compass seat.

A settee and easy chair that belonged to James Logan (figs. 51, 52) are contemporaneous with the Wistar armchair but are clearly from a different shop. Logan patronized a number of local furniture makers, and a remarkable Philadelphia Palladian desk-and-bookcase that descended in the Armitt family is thought to have been among the original furnishings of his house, Stenton (fig. 53). A candidate for the maker of that object and the aforementioned seating furniture is Stephen Armitt, whose daughter Sarah married Logan’s son James in 1766. Armitt was from Staffordshire; however, the issue is not his nationality but the nationality of his workforce. Both he and Logan had Irish indentured servants, and the design of Logan’s seating furniture suggests the involvement of Irish chairmakers.[33]

The Logan settee is unique in American furniture—a cross between an armchair, an easy chair, and a conventional settee. Up to the seat rails, the settee is made like a large armchair but with center legs. Rather than having over-the-rail upholstery, the settee has a slip held in place by a molding glued to the upper surface of the front rail. The front legs are joined to the front rail with round tenons in bored mortises as on the Wistar armchair. The arms are like those of a small easy chair, but without wings. Although novel in its shape, the back resembles that of a settee or sofa. The settee lacks a rail just over the rear seat rail to aid in upholstery, so all the tacking necessary to attach the inner and outer decks and webbing for the back had to be concentrated on the rear seat rail. The inclusion of a lower rail was standard in urban English furniture by the mid-1720s, which suggests that Logan may have commissioned the settee and armchair soon after Stenton was completed in 1730. A plausible date for those objects would be circa 1730–1740.[34]

Workmen from the Logan settee shop were the only Philadelphia chairmakers who used trifid feet with rounded toes. The feet and legs of the armchair illustrated in figure 54 are so similar to those of the Logan settee that those objects could have been made en suite. The armchair is one of the most overtly Irish examples of Philadelphia seating. Its horizontally configured seat rails are clad with vertically oriented veneer, and the legs are dovetailed to the front rail. The rear legs are semi-cabriole, a feature sometimes seen in Irish and English chairs and frequently encountered on seating from this shop. The Chinese-inspired crest rail is even more unusual. These features suggest that this shop included at least one immigrant Irish chairmaker, and that the armchair was made soon after his arrival. The only concession to Philadelphia construction practices is the use of a solid splat (some Irish compass-seat chairs have solid splats, but most are veneered). As is the case with many later Philadelphia compass-seat chairs, the rear stiles above the seat rails are worked round. Although modern collectors tend to prefer chairs with this type of stile, rounding the front edges softens the curves. Stiles like those on the Wistar armchair have much greater directional focus.

A side chair from the Logan settee shop has similar legs, a splat and crest that are simplified versions of those on the armchair, and a turned rear stretcher (fig. 55). The chairmakers who worked there frequently used turned rear stretchers, a feature that does not occur on any chair seating from the shop that produced the Wistar armchair. Like the armchair illustrated in figure 54, the front legs of the side chair are dovetailed to the front rail. The seat rails are also veneered, but the grain is oriented horizontally—an early concession to what would become the more common Philadelphia practice of using solid rails. Since dovetail joints prevent the leg from rotating, there was no need for the makers to use thick, structural knee blocks like those on chairs with round tenons.

Some chairs from the Logan settee shop have solid walnut rails, which left the dovetail joints visible at the front. Other chairs—possibly made there or by journeymen who moved to other shops—have solid rails that are half-lapped at the front corners and have similarly visible dovetail joints. Although structurally sound, this is the most complicated-looking version of the horizontal-rail-to-leg construction encountered on Philadelphia compass-seat chairs. In later work, the makers in this shop used round tenons, structural knee blocks, and, occasionally, re-sawn sections of the front and side rails to produce slip-seat moldings with continuous grain (fig. 56). The inspiration for these changes may have been migrating journeymen or seating from the Wistar armchair shop. An armchair that descended in three interrelated Philadelphia-area families has undercut knees and slender, down-curving handholds—early features on seating from the shop that made the Logan settee and related chair forms (fig. 57). However, this armchair also has non-cabriole rear legs and a splat similar to those on chairs from the Wistar armchair shop. The only deviation is the small, vertically oriented ogee element just under the upper C-scroll of the splat.

The armchair illustrated in figures 58 and 59 provides further evidence of stylistic transfer in early Philadelphia seating. Its splat is a simplified version of that on the armchair illustrated in figure 57, and both objects have similar crest details, although the design is inverted on the former (fig. 58). The derivative chair has neither a balloon compass seat nor horizontally configured rails, and its arms and arm supports are somewhat naïve in conception and execution. Did someone who apprenticed or briefly worked in the Logan settee shop make this chair? Was it made by someone who saw a chair like the example illustrated in figure 57, but was unable to replicate some details? Or was it an entirely intentional creation, simply borrowing the feature its maker found most appealing or accessible? Although the answers to these questions remain elusive, the derivative armchair makes a statement about the dissemination of design in Philadelphia and the seemingly unstoppable drive of craftsmen and their clients to be stylish.

Other Philadelphia shops made compass-seat chairs, and almost every chairmaking establishment produced examples with vertically configured seat rails and trapezoidal frames. Probably during the late 1730s and early 1740s, compass seat chairs were the most avant-garde and conceptually evolved products of chairmaking shops. However, the manufacture of compass-seat chairs continued for decades, as indicated by a 1759 invoice for a set James James made for Philadelphia Captain Samuel Morris. The side chairs in this set cost £2 each (fig. 60), and the armchair, presumably en suite, cost £3.10. James also sold Morris a “traveling chair” (sedan chair), one of the most luxurious items available, for the staggering sum of £28.